Abstract

Research suggests that the built environment is associated with drug use. However, there is limited scholarship focusing on specific features of the built environment that influence drug use behaviors, experiences, and patterns and how risk factors for drug use are placed in distinctive urban and rural settings. Applying Neely and Samura’s conceptual theory that describes space as contested, fluid and historical, interactional and relational, and defined by inequality and difference, we assessed data from semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted between 2019 and 2020 with consumers at syringe exchange programs (SEPs) in an urban location (New York City) and a rural location (southern Illinois). We aimed to contextualize how drug use manifests in each space. In total, 65 individuals, including 59 people who use drugs (PWUD) and six professionals who worked with PWUD, were interviewed. Findings illustrate that, in both the urban and rural setting, the built environment regulates the drug use milieu by mediating social reproduction, namely the degree of agency PWUD exert to acquire and use drugs where they desire. Processes of “stigma zoning,” defined as socio-spatial policing of boundaries of behavior deemed undesirable or deviant, impacted PWUD’s socio-geographic mobility, social conditions, and resource access, and modulated PWUD’s broader capacity and self-efficacy. Similar patterns of drug use, according to social and economic inequities chiefly related to housing instability, were further observed in both settings.

Keywords: built environment, harm reduction, homelessness, people who use drugs, rural, urban

SPACE AS A REFLECTION OF SOCIAL REPRODUCTION

Space organizes social life (Neely & Samura, 2011) and facilitates, or precludes, exposure to social and environmental risks (P. Draus et al., 2015; Duff, 2011; Keene & Padilla, 2014). Research consistently shows that one primary manifestation of space, the built environment—the purposeful creation and spatial arrangement of housing, sidewalks, roadways, retail and institutional buildings, public transit, and green spaces—is linked to birth outcomes and long-term health (Nowak & Giurgescu, 2017; Villanueva et al., 2013). Hence, access to, and ability to leverage, health promotion resources that populate the built environment, or to simply avoid harms (Link & Phelan, 1995), can generally be said to reflect how social capital may manifest across the built environment and contribute to spatial health inequities. Likewise, this dynamic illuminates how systems may work to limit economic and political rights by curbing access to space and thus resources, as a manifestation of social reproduction (Lefebvre & Nicholson-Smith, 1991; Massey, 1993).

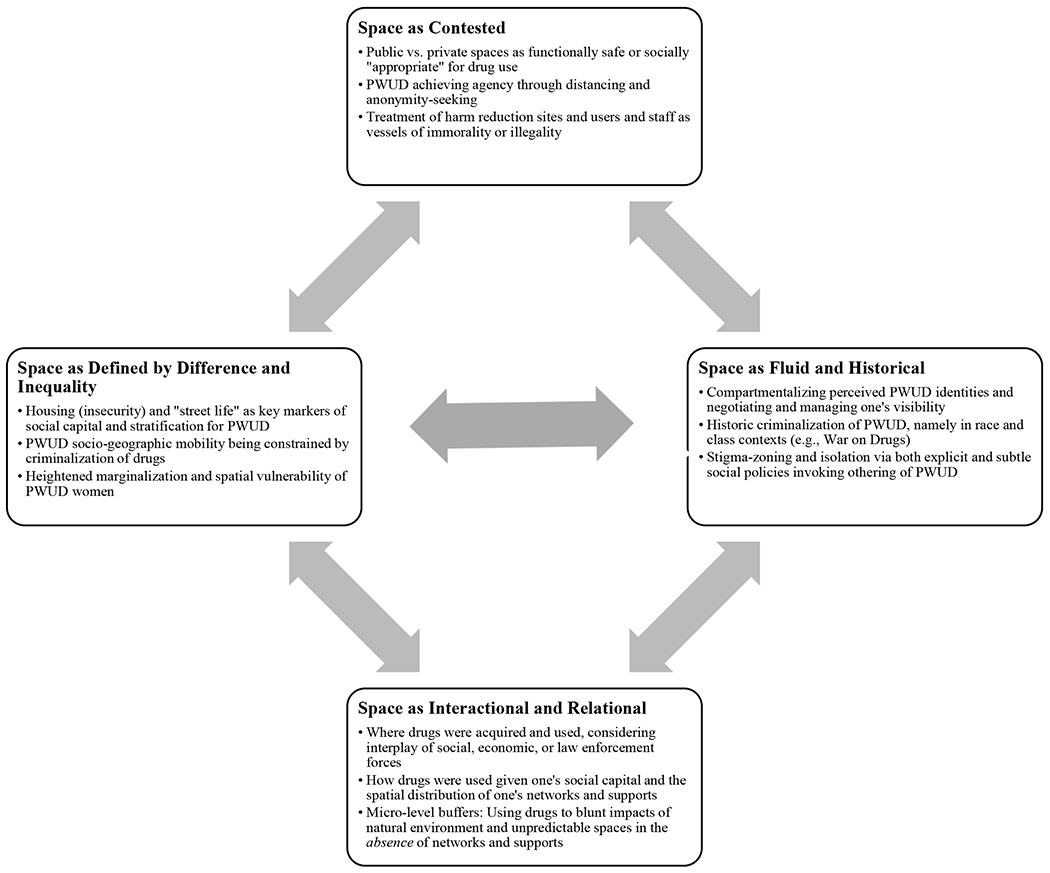

Neely and Samura, in consideration of these processes of social reproduction, describe space as contested, fluid and historical, interactional and relational, and as being defined by inequality and difference (Neely & Samura, 2011). Under this model, space is theorized as key in the development and facilitation of health promotion processes (Neely & Samura, 2011). Space becomes contested through political determinations of who does and does not control space (e.g., in the case of eminent domain, etc.). Space is interactional and relational insofar as master cultures have primacy in spatial management, invoking processes of subjugation and exclusion that impact minority groups’ mobility (Massey, 1993, 2009). Space is fluid in that it “changes hands” over time and becomes subject to both dispossession and reclamation (e.g., during processes of colonization and gentrification, respectively). Space is further defined by inequality and difference, with risks allocated according to place (e.g., in terms of disproportionate environmental burdens, like air and water pollution, frequently manifesting in low-income and racial/ethnic minority communities (Bullard & Johnson, 2000; Pulido et al., 2016)). In the present research, we conceptualize the built environment within Neely and Samura’s spatial theory, focusing on urban and rural drug use behaviors, experiences, and patterns.

THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT AND DRUG USE

A relatively small base of literature has explicitly theorized the built environment as a determinant of drug use behaviors, experiences, and patterns (overdose, mortality, etc.) (Deering et al., 2014; Hembree et al., 2005). This literature has also lacked a focus on broader the spatial modalities of drug use, in the context of social reproduction, namely in view of how space may contribute to drug initiation and continuation). Further, this research has largely neglected consideration of potential comparative distinctions between urban and rural spaces beyond attention to relative differences in population density (Keyes et al., 2014; Pear et al., 2019). However, the structuring of the built environment is fundamentally associated with drug use—or, as it may be said in consideration of human agency, drug use is associated with the structuring of the built environment (Deering et al., 2014).

Per Neely and Samura’s spatial theory (Neely & Samura, 2011), the latter framing represents an interactional and relational view of the built environment as conditioning drug use approaches and patterns of drug distribution and use (C. B. Smith, 2010). In contrast, the former framing more explicitly focuses on how fluid and historical dimensions of the built environment (e.g., unequal policing in communities of color, redlining/segregation, etc.) reproduce dynamics encouraging—or simply not discouraging—drug use and thereby creating spatially-specific avenues for particular drug use behaviors (Evans et al., 2019; Van Olphen et al., 2009). Given the complex spatial arrangements that exist between and within urban and rural environments and how risks may propagate accordingly to the geographic distribution of resources (Blackmon et al., 2016; Dahly & Adair, 2007), modalities of drug use are likely to be intricately stratified.

Here, we apply Neely and Samura’s spatial theory (Neely & Samura, 2011) to analyze qualitative interviews conducted with people who use drugs (PWUD) and utilize syringe exchanges programs (SEP), and SEP staff, in an urban location, New York City, and in a rural setting, southernmost Illinois.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This qualitative study was conducted as part of two larger projects aimed at understanding HIV risk and prevention for people who injected drugs, many of whom engaged in risky sexual behaviors (Allen et al., 2019; Walters et al., 2017, 2020). Interviews were conducted at a SEP in NYC, hereafter referred to as Climb, and a SEP in rural southern Illinois (“Valley”). In recent years, New York City has seen steady rises in heroin and fentanyl-related overdoses (Tuazon et al., 2019), while rural southern Illinois has seen some of the most elevated increases in general nonmedical opioid use and associated morbidity and mortality in the U.S. (McLuckie et al., 2019; The Opioid Crisis in Illinois: Data and the State’s Response, 2017). Climb is a neighborhood-based SEP, one of several dozen in New York City, with one physical location providing a variety of on-site amenities and services, such as new syringes and needles, contraceptives, basic medical care, HIV and HCV testing, counseling, and food, catering mostly to local neighborhood residents. Valley, just one known SEP in southern Illinois, provides new syringes and needles, contraceptives, and HIV and STI testing. Valley possesses two physical locations but functions as more of a “mobile” outreach entity, moving to areas of need—encompassing several hundred miles of rural territory—via motor vehicles. To protect the SEPs’ identities, no additional potentially-identifying information is provided.

Procedures and Analysis

Between August 2019 and February 2020, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted in-person, at Climb and Valley, respectively, by interviewers experienced in qualitative interviewing methodology. Eligible PWUD had to be ≥18 years old and had to have injected drugs within the past year. PWUD were recruited via outreach conducted with the support of the partnering SEPs. SEP staff and other professional stakeholders (a pharmacist and a paramedic in rural southern Illinois) had to be ≥18 years old and have regular exposure (> three days per week) to PWUD as part of their job. The interviews were audio-recorded and lasted approximately 1–2 hours. After each interview, the interviewer created an observational memo outlining their perceptions of interviewees’ points of emphasis, body language, and tone, in alignment with the aims of “thick description” (Geertz, 1973). The interview audios were professionally transcribed and then cleaned and analyzed using Dedoose (v 8.3.21).

Qualitative coding procedures followed grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014). The analytic emphasis was guided by Neely and Samura’s estimation of spatial features, namely emphasizing factors that are contested, fluid and historical, interactional and relational, and defined by inequality and difference (Neely & Samura, 2011). Line-by-line coding was executed; then, thematic codes and a codebook were developed (Charmaz, 2014). Codes were then sequentially reviewed and refined, and additional codes were produced and applied, as appropriate. Three coders independently reviewed and coded the transcripts, with one of the coders resolving discrepancies. Following this process, quotes were distilled and then aggregated into emergent thematic and sub-thematic groups. Member-checking was then conducted with existing study respondents and relevant stakeholders to ensure fidelity in our analytic interpretations (Carlson, 2010). All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at New York University. Written consent was acquired from participants. Participants received a $40 Visa gift card for their time.

FINDINGS

A total of 64 individuals participated in the interviews, including 59 PWUD (38 at Climb and 19 at Valley) and four SEP staff (three in NYC, including one at Climb and two at another SEP; and one at Valley). PWUD demographics are provided in Table 1. Briefly, the mean age of PWUD at Climb was 42 years old compared to 37 years old at Valley. At Climb, 24 men, 14 women, and two transwomen who were PWUD were interviewed. At Valley, 10 men and nine women who were PWUD were interviewed. A total of 19 PWUD at Climb were Hispanic, eight were White, five were Black, and six were multiracial (Black/Hispanic). A total of 17 PWUD at Valley were White, one was Black, and one was Native American. The racial/ethnic breakdown at each site roughly reflected each of the communities’, and SEPs’, demographics. To protect the SEPs employees’ identities, no descriptive details beyond role are provided.

Table 1.

Overview of PWUD Respondent Demographics (n=59)

| Climb (New York City) (n=40) | Valley (Southern Illinois) (n=19) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 42 | 37 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 24 (60%) | 10 (53%) |

| Women | 14 (35%) | 9 (47%) |

| Transgender Women | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity* | ||

| White | 8 (20%) | 17 (90%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19 (48%) | 0 (0%) |

| Black | 5 (13%) | 1 (5%) |

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

| Mixed | 6 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sexual Identity* | ||

| Heterosexual | 34 (85%) | 17 (89%) |

| Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual | 2 (5%) | 2 (11%) |

Notes: indicates missing data

We identified themes within the four components of Neely and Samura’s model of space: being contested, fluid and historical, interactional and relational, and defined by inequality and difference (Neely & Samura, 2011), which emerged across two primary dimensions. Figure 1 outlines these dimensions, demonstrating their mutual embeddedness (Neely & Samura, 2011). The first dimension speaks to drug acquisition and drug use behaviors across the built environment and the salience of “street life.” The second dimension related to a process we refer to as “stigma zoning.” Stigma zoning is socio-spatial demarcation and policing that activates, or is activated by, moralistic views on what is appropriate human behavior, inducing punitive forms of stigma when there is a lack of conformance to these views (Link et al., 2015; Link & Phelan, 2001). Stigma zoning reflects how micro-level and communal beliefs manifest as larger structural exclusions, including social and economic deprivation. Stigma zoning can also limit socio-geographic mobility, or social conditions mediating geographic access to resources, an additional theme we discuss here. Pseudonyms are used to present respondents’ commentary.

Figure 1.

Spatial Typology of Drug Use Behaviors, Experiences, and Patterns Adapted from Neely and Samura (2011)

Space as Interactional and Relational and Being Contested

Street Life: Accessing Drugs and Harm Reduction Services

Respondents’ commentary revealed the complex ways that PWUD navigated the built environment to acquire drugs. Commentary specifically addressed how interpersonal relationships, spatial barriers, and socioeconomic circumstances helped structure where PWUD used drugs and the extent to which their drug use, in the context of individual agency, was concordant with harm reduction principles (Moore & Fraser, 2006). The question of “how” drugs were accessed spoke to both a relational component (i.e., where PWUD acquired the drug and in what spatial context it was used) and an interactional component (i.e., by what means or approaches PWUD acquired the drug in employing social and political capital (Shim, 2010), and potential risks that would be concomitantly assumed).

In general, PWUD at both Climb and Valley indicated that they received their drugs from street dealers in their local communities. PWUD emphasized the importance of knowing the parameters of the built environment and trusting the people populating it to safeguard their health (Cohen et al., 2008). As such, participants discussed how their (neighborhood) social capital was used to ensure the quality of drugs purchased and thus pursue better health outcomes. For example, when Victor, a 45-year-old White man who was a Climb client, was asked if he had a regular dealer or regular location where he obtained drugs, he is quick to highlight drug strains he would not be comfortable with. He explains: “I have different spots. Different places that I know of, so I just do not go and put anything in my body. If I do not know you, I am not going to purchase anything.” Comparably, Jamie, a 36-year-old White man who was a Valley client, also spoke about the need to mitigate risks but couched his understanding more in the context of needing to build a drug use community to ensure safer drug use practices. He explains, “To be honest, I got six or seven major dealers in town. They will come to me when I get my package of syringes and stuff, and they will fight to get them, so, they can pass them out with their [drugs]. So, we’ve kind of formed a little community. It’s a sad thing to say.”

When Jamie was asked why he thought, despite his allusion to this community’s protective effect, this dynamic was ‘sad,’ he adds, “[police] found out and they have kind of let a few things slide to make sure that we stay out there. They know we don’t do anything to mess up anybody or kill anybody, and you know, we’re fucking ourselves up.” Here, the notion of police allowing PWUD to ‘stay out there,’ highlighting a relational “enabling” dynamic (Duff, 2011), telegraphs processes of spatial separation and othering (Link & Phelan, 2001).

Both Climb and Valley respondents typically described their drug use sites as “on the streets,” or in a home or public bathroom. Descriptions of drug use on the streets were generally employed as a catch-all to describe any use in an outdoor space, typically a secluded sidewalk or bridge/underpass. As examples of spatial contestation, drug use site preferences were largely predicated on an individual’s ability to achieve some degree of anonymity, from both the public and authority figures. In contrast to findings on the “everyone knows everyone” culture predominating small towns and rural areas that socially isolates PWUD (Fisher et al., 1997; Monnat & Rigg, 2018; C. Smith, 2014), PWUD at Climb framed anonymity as more elusive to obtain in New York City due to the area’s compacting urban features.

When Finn, a 40-year-old White man who was a Climb client was asked where his drug use “sessions” took place, he notes he primarily used alone, while highlighting an indoor versus outdoor use dichotomy. He explains: “Most of them [drug use sessions] would be like in a bathroom,” including public bathrooms, “or somewhere in a basement; [to] get out from the street, and at the same time, [have] some privacy.”

Likewise, when Ronnie, a 50-year-old Black man who was a Climb client, was asked why he preferred to use at home, he stresses, because of “… police, and to be content and be comfortable, and be at ease and be relaxed, and be safe… in a safe environment. I call my house a safe environment. Because I don’t ever have to worry about all the other shit, you know what I’m saying?” For Finn and Ronnie, drug use site selection served as a buffer against potentially hostile or otherwise negative interactions that would disrupt their physical safety and health. However, for Ronnie, as a Black man, this relational dynamic was perhaps even more amplified as a function of the racialized over-policing of drugs (and of Black people more generally) frequently seen in urban spaces (Engen & Steen, 2000; Lassiter, 2015).

In the rural setting, drug site selection was more explicitly described as focused on preempting public criticism of drug use, and thus a source of spatial contestation (Neely & Samura, 2011). Here, site selection was also focused on maintaining a broader balance in the local community. Theo, a 29-year-old White man who was a Valley client who injected drugs, explains:

I mean, don’t get me wrong, addiction’s a bitch, you know? And it’s probably not the healthiest thing; by that, I mean, there's a hell of a lot of other things I could be doing [that would be] a lot worse. I mean, look at the news: there's weird shit going on a lot worse than just me sticking a needle in my arm or me getting high in my basement. I don’t bother nobody, I stay home.

Likewise, Valley’s director, Winston, illustrates how this furtive, but defensive, orientation is the outgrowth of geographic fragmentation and the “closeting” of harm reduction services, more broadly, in their rural communities. When asked to describe Valley’s consumer outreach approach, Winston answers: “Word of mouth, not a lot of advertising at all—because the public wasnť open to that… so, for us, we thought, ‘Go slow.’ Kind of be quiet and go under the radar as much as possible.”

Of note, Climb also faced various modes of service regulation and tacit policing, which thwarted PWUD engagement. Neely and Samura describe this contestation—e.g., of harm reduction as quasi-legal and its users or facilitators as immoral or criminal (Baker et al., 2019; Moore & Fraser, 2006)—as a way in which space reinforces power structures and vice-a-versa (Neely & Samura, 2011). These social policy/law enforcement postures, as Roger, a services coordinator at Climb, illuminated, impacted service delivery. Such postures may be augmented in communities with large racial/ethnic minority populations (Bass, 2001; Lynch et al., 2013), like the one Climb was in.

Cops will be cops. I’ve had cops come up to the door and be like, ‘I need to come in, somebody just robbed somebody, and I need to go in and search it.’ I’m like, ‘No, if you don’t have a warrant.’ Then, they will stand outside my door and I’m like, ‘You’re literally tampering with public health services. There are people not trying to come in because you are standing at our door, and that’s really bad for public health.’

Drug acquisition was comparatively more specialized in the urban context in contrast to the rural context, potentially leading to more impromptu use, in a distinctly interactional and routinized context. Raleigh, a 51-year-old White man who was a Climb client, further illustrates this. Describing a “typical” day, he indicates how his daily routine is sometimes interrupted, and how he is effectively propelled towards drug use by the peer networks that he encounters on the streets.

I’m waking up in the morning, taking a shower, getting dressed, walking out the door. When I walk out the door, I usually have a general plan of what my day might turn out to be or what agendas I have… Sometimes, I get detoured from staying with the plan, and sometimes, like if I run into a friend of mine… ‘Hey man, what’s up, man? Want to get high?’ ‘Hey, man. Don’t worry about it, man. I got you, man. Whatever you need, I got you, bro. Don’t worry about it.’ I’m looking for the agenda that I need to take care of. But if I run into friends and acquaintances, it takes me on a little detour.

When further queried about how his history in this area may intensify these patterns, Raleigh adds, “Everywhere I run, every corner I turn, I run into somebody I know. And they’re calling out my name. I’m like, ‘Who the hell is that?’ I went to high school in this area. I went to junior high school in this area. I went to elementary school in this area.”

Of note is how the relatively pronounced density of PWUD in Climb’s highly urbanized and integrated catchment area, as a socio-geographic risk factor, appeared to contribute to an increased likelihood of Raleigh being compelled to use drugs.

Drug use site selection, particularly for PWUD who were homeless or who spent extended periods on the streets, was also intimately conditioned by the “natural” environment (Neale, 2001). Eliot, a 47-year-old White man who was a Climb client, emphasizes:

The emotional pain is hard, and the drugs don’t even help that. You know, the physical pain, the drugs are great for; the headache, or the leg pain, the backache, the cocaine works great… The freezing cold, just [back in] December, January, February, I must have spent four grand in those three months staying numb from the cold. I was smoking the fucking [crack] in a snowstorm. If I didn’t smoke that crack, I would’ve froze, and died. I would’ve froze, and died, I know it. And I have nothing, or nobody. I’m in the street—I have to stay high.

Here, Eliot explains how the built environment can radically accentuate PWUD’s diminished social network and create a void that drugs can, in part, fill. This dynamic situates drugs as a shield against the harsh natural environment that may be forced to interact with and highlights social supports as a missing link in the wider drug use ecology (McVicar et al., 2015). PWUD at Valley, like Eliot, also saw drugs as a key resource for ameliorating the complexities of street life. When asked about her drug acquisition and use process, Cynthia, a 39-year-old White woman who was a client at Valley, explains: “I walk a lot. That’s why I have to be high all the time on the street. I tell somebody, ‘It’s all right being homeless on the street because I’m tough. I can handle it.’… I’ll rest and sleep right there on the sidewalk. I gotta have dope to be on the street every day. Like, it’s mainly so I can protect myself, you know?” Here, Cynthia articulates how drug use acts as a protective buffer in living in an unpredictable natural environment that is, for her, effectively socially and structurally unmitigated. Of note, her positionality as not only a PWUD, but as a woman who uses drugs, appeared to increase her sense of (physical) vulnerability (Kulesza et al., 2016; Measham, 2002). This drug-use-as-survival mechanism was provoked in large part by endemic social stratifications and socio-spatial policing systems (C. B. Smith, 2010), dynamics which are discussed more in-depth in the proceeding section.

Space as Defined by Inequality and Difference and Being Fluid and Historical

Stigma Zoning and Socio-Geographic Mobility

Social policy, or lack thereof, in relation to drug use, was frequently couched as fueling stigma processes and stunting socio-geographic mobility. Housing, or lack thereof, acting as a salient marker of social difference (Neely & Samura, 2011), was frequently cited in this context. Jennifer, a services coordinator at Climb, stressing housing as a chief social policy interface for PWUD, argues, “Housing is the biggest health risk of anything [PWUD] face just because everything is affected when you’re not stably housed… it’s really, really difficult to stay adherent on any kind of treatment when you’re not stably housed. It’s difficult for wounds to heal, it’s difficult for so many things.” This commentary is consistent with literature highlighting quality, stable housing as a key predictor of health equity (Krieger & Higgins, 2002; Swope & Hernández, 2019).

To ‘live on the streets,’ which is effectively to be uncoupled from the built environment, further “others” one from the general population (Link & Phelan, 2001). This, in turn, ostensibly marks one with the negative attribute of being unmotivated or undisciplined (Markowitz & Syverson, 2019). Goffman framed such associations as manifestations of social stigma (Goffman, 2009). Stigmatizing labels utilized to describe PWUD frequently involved ideas of space and were embedded in policy descriptors, furthering a process of what we term “stigma-zoning,” socially-guided demarcation, and policing, of the spatial boundaries (boundary-making) for behavior deemed undesirable or deviant. Stigma-zoning aligns with Neely and Samura’s characterization of space as being formed by fluid and historical forces that shape social beliefs of normative behavior, that in turn shape social policy (Neely & Samura, 2011). The connotation of PWUD as “street people” or “homeless” highlights perceptions of social deviance in a specific, often public, space (Keene & Padilla, 2014; Richardson et al., 2013). Social policies in this vein were described by respondents as being activated and made especially legible in contexts such as housing. This legibility was largely forged by the status of housing as a government-subsidized commodity for people who are low-income, such as many urban and rural PWUD (Pear et al., 2019; Redonnet et al., 2012).

Stigma-zoning is a historically-shaped mechanism that bridges social beliefs on acceptable behavior with carceral politics (D. Buchanan et al., 2002; Nussbaum, 2009). An example of this is seen in the overdose response policy in NYC that compels responding officers to cordon-off the location of an overdose with crime scene tape, an act typically reserved for sites of extreme violence and homicide (Latimore & Bergstein, 2017; Phillips, 2020). Fran, an outreach coordinator at Climb, describes this policy’s stigmatizing and “chilling” effect:

Even with overdose deaths, people are sometimes afraid to report them, because although they came with an overdose task force out in New York City, and the state, basically they treat every overdose as a crime scene. Putting yellow tape up, locking it, as if there was a death already that happened. [So] if you’re calling, and you don’t want your neighbors to see or know what happened… then, they got just all cut off like a big crime scene.

Such policies, Fran suggested, rooted in America’s history of drug criminalization (Cooper, 2015) may have a dual impact—attenuating PWUDs’ desire to report overdoses (Jakubowski et al., 2018; McClellan et al., 2018) and contributing to a narrative arc that sees drug use and drug-related morbidity as criminal, rather than medical, phenomena (Dollar, 2019). Here, both historical processes—criminalization and medicalization—wield the effect of shrinking the radius of PWUD’s socio-geographic mobility, discussed further in the coming section.

With this in mind, stigma-zoning characterized the flow of activity in many spaces used and inhabited by PWUD respondents, often surfacing as conjoined stigmas related to drug use and perceptions of homelessness (Gross & Wronski, 2019; Palamar et al., 2013). Jamie, the 36-year-old White man client at Valley who was previously referenced, articulates the following, notable for his framing of rural PWUD’s operative space as a purposeful, albeit confined, ‘little area’:

You get profiled, you get looked at, you get put in a category… in our little area, you can catch it everywhere you go…I mean, the understanding of addiction is they only get you like, you’re a junkie, no matter what, and treat you like you live on the streets. And the messed up part is there’s quite a few of us around here are doing pretty well for ourselves. We just have problems. And we choose to take on our issues in life with drugs.

Multiple PWUD relayed how various visible markers of social status, including living on the streets or having track marks from drug injection, stoked stigmatizing body language and sometimes physical distancing from members of the general public. Javier, a 29-year-old Hispanic man client at Climb, speaks on this, alluding to the high density of people in New York City and how this density contributes to the city’s well-known people-watching Zeitgeist. Javier explains how his track marks create an acute sense of judgment when he is out in public engaging in mundane activities like using the city’s bustling public transit system:

When you start re-using the same fucking needles, the shit starts to leave real track marks on your arm…. Anybody’s going to know what that is. Anybody. Even a child would be able to tell, and it’s embarrassing… I kind of feel like all eyes on me, all the fucking time, and it’s fucked up. Particularly during summer when you’re always wearing short sleeves and all that. Oh, God… or when you’re on a crowded train or you’re on a crowded bus, which is damn-near half-the-fucking-time when you’re commuting. You know what I mean? If you’re going from Harlem to the Lower East Side, you’re going to get on a packed train, or you’re going to get on a packed bus.

This delineation further illumines how the design of some built environments, particularly those in large cities like New York City where one is frequently highly visible when in public, can—rather than anonymize these urban individuals and thus breed indifference, as Simmel argued (Simmel, 2012)—latently invite stigma against PWUD. Therefore, paradoxically, stigma, in the urban setting versus the rural setting, operates as a force that may quite fluidly enlarge the PWUD milieu, but by creating ubiquitous, or simply continuous, spaces for identity devaluation, which in turn, potentially diminishes self-image, self-efficacy, and health (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013).

As part of the sequence of acquiring drugs or simply avoiding being labeled as a drug user—or the derivations that follow—Climb respondents discussed the value of being inconspicuous and trying to blend into the dense cityscape to avoid stirring suspicions, harassment, and judgment (Earnshaw et al., 2013). Dina, a 69-year-old Black woman who was a Climb client, describes a drug connection she recently had. She delineates her ability to maintain a visually-neutral identity to maintain this connection. This balancing act was made possible both by Dina’s knowingly unassuming appearance and that of the dealer’s home, suggesting a kind of symbiosis:

I could go right to [the drug dealer’s] house, because they lived right on [street], and it was a two-family house. I could just go knock on the door, ring the bell… So, it was better, because it was just like going to visit somebody. And, I looked like I was going to visit somebody, because I never let myself go: I never had dirty clothes on, and all that. That’s a tell-tale sign.

A 25-year-old Hispanic woman client at Climb, Beatrice, further explains how this kind of hyper-self-awareness occurs in a fluid in-group/out-group context (Neely & Samura, 2011). This maps onto the idea of a spatially segmented built environment corresponding to one’s identity as “normatively” (un)employed, (un)housed, etc. (P. J. Draus et al., 2010). Ruminating on the maligned ‘street person’ persona and elevating the idea of socio-geographic mobility, Beatrice explains:

As far as me being out on the streets, living in the streets, eating from the garbage, things like that; thankfully, I didn’t have to go through that… which I don’t grudge either. Because I was with people who did that, and I did my best to help them out. Another thing is that I always kept a job, so I never had to—thank God, again—I never had to steal. I never had to go out of my way and do things that I didn’t want to do to get high. I always kept a job. I always had money. I always made sure that I looked the part, played the part, and then I was living this double life where I would get high.

Thus, for PWUD like Beatrice, most intuitively, locations for drug acquisition and use become reflections of one’s placement along both a socioeconomic and spatial gradient. This kind of socio-geographic mobility is mediated by race, gender, and other prospective sources of social stratification (Löw, 2006; Neely & Samura, 2011). Although Beatrice’s identity as a Hispanic woman may magnify her cognizance of these differences, these processes otherwise appeared to help her negotiate distancing from a marginalized identity, allowing compartmentalization and (temporary) reprieve from being socially bound to a stigmatized behavior and space (P. Draus et al., 2015).

The dynamics contributing to stigmatizing descriptions of certain PWUD as “street people” were replicated in Valley’s communities as well and were amplified when drug injection, a kind of accelerant of stigma (Palamar et al., 2012, 2013), was referenced. Melvin, a paramedic operating in Valley’s catchment area, adopted stigmatizing discourse in describing the arc of PWUD’s lives (Ezell et al., 2020), signaling awareness of their limited socio-geographic mobility and attendant issues in network diffusion.

Most of the needle users tend to be more on the street level… I don’t know many people that are maintaining once they get to the point where they inject. Maintaining a job. There doesn’t seem to be very many [that are] functional… Like, people talk about ‘functional alcoholics’ where they can hold down a job and still pay their bills—I don’t see that with injection users. It seems to be, in my experience, what most people would think of as rock bottom: In stereotypical skid row, living in abandoned houses, or it’s a ‘family affair’ type thing.

In other cases, socio-geographic mobility more indirectly amplified various personal risks, namely when it came to encounters with law enforcement—which many respondents deemed as frivolous and discriminatory against PWUD. Lula, a 23-year-old Native American woman who was a Valley client notes, “I do think that because I’m a drug user that they do perceive me differently; because me being a known drug addict to them, I’m constantly being pulled over in a vehicle or something.” Going on, Lula describes a drug raid on her home that occurred while she was in the shower. “Actually, they made me stand there, naked, while they searched the house with a male cop at the door. So… I guess it was kind of an embarrassing situation for me.” Emphasizing the police officer was a male, Luna alluded to an added layer of marginalization tied to her gender. This binary highlights the unique precarity associated with one’s privacy and (gendered) personhood when it comes to drug-related policing and the boundary-making it entails, where personal spatial boundaries are blurred, if not explicitly eliminated.

Continuing, in discussing his feelings of being stigmatized for sleeping on the streets, 44-year-old Benny, a Hispanic man client at Climb, speaks to stigma-zoning in public spaces as an extension of “hostile architecture” commonly used in urban spaces to dissuade the congregation of homeless individuals and PWUD (De Fine Licht, 2017; Rosenberger, 2020):

When I’m sleeping on the streets, sometimes the police comes to check [to see] if we are okay. When they check, I feel like I be treated like I’m a drug user. [They are] like, ‘Can you get up? I want to take a picture.’ They take my picture where I was sleeping. Like, ‘Get up. Pretend you’re not there. We’ll take your picture. You’re not there, and then you can go back.’ Yes. Like NYC Park people, like people who see me every day hanging out [in] this part of town. Actually, they don’t disrespect me more like [a] drug addict, but they also don’t ignore it.

For Lula and Benny, navigations through the built environment were curtailed by stigma zoning vis-a-vis sometimes explicit, other times implied, drug criminalization policies that were historically-embedded (Caulkins et al., 2020; Cooper, 2015). This stigma-zoning was bookended by interrogation of PWUD’s more formative identities, this provoked by ill feelings about PWUD, homelessness, and legal prerogatives to either direct, or erect barriers to, drug use and congregation in public spaces (Ezell et al., 2020; Green et al., 2010). In each of these cases, a lack of geographic, and thus social, mobility contributed to a fundamental lack of capacity to avoid threats to their freedom to move, demonstrating diminished self-efficacy in the wider context of one’s health (Cohen et al., 2008; Link & Phelan, 1995; Shim, 2010).

DISCUSSION

Findings from this research illustrate the fluid ways in which drug use patterns both form and are formed by the built environment and work to press and embed particular drug use behaviors and experiences into local geographies. In considering Neely and Samura’s formulations on space (Neely & Samura, 2011), this dynamic speaks to PWUD’s capacity to negotiate their lives within the purview of larger structures, such as law enforcement. Of note, patterns of socio-spatial policing of PWUD that were observed here were shown to cut across both urban and rural geographies. This dynamic illuminates how urban and rural PWUD navigate their respective environments through more-or-less commensurate socio-geographic mobility constraints, showcasing a particularly broad, persistent form of social reproduction (Chitewere et al., 2017; P. Draus & Carlson, 2009).

To this end, the urban and rural environments observed here shared comparable drug use milieu traits in regards to how they were spatially encoded. Specifically, our results align with findings on the socio-spatial stigmatization of PWUD (Keene & Padilla, 2014; C. B. Smith, 2010), demonstrating fluid and historical criminalization modalities that give PWUD limited latitude to decide where and how to use drugs. Also, aligning with prior work, our research shows that an aggregation of social ties in a geographic location can create interactional and relational dynamic that buffer PWUD from potential drug use-related harms (Duff, 2011; Latkin et al., 2017; Richardson et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the natural environment, namely in the context of inclement weather as described by respondents in this work who were unstably housed, represents a dimension of the built environment wherein social ties become less salient and drug use can become, in a word, protective (e.g., in the context of coping (Manhica et al., 2020; Quinn et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2013)).

Built environment features that are conducive to personal wellbeing and community belongingness for PWUD—such as stable housing and employment opportunities with a livable wage, and access to treatment providers and harm reduction resources—are often spatially stratified ((Collins et al., 2019; Rhodes et al., 2003). As we show here, these stratifications emerge, in large part, through historic macrosocial forces contributing to stigma and discrimination against drug use (Hembree et al., 2005; Rhodes, 2002). This marginalization maps onto socio-spatial policing of not just how drugs are accessed and used (i.e., the traditional purview of the carceral state), but where they are used. This boundary-making, taken in tandem with high densities of fragmented, but concentrated, drug use milieus across the built environment, may expand and amplify PWUD milieus (Ahern et al., 2007; Corrigan & Nieweglowski, 2018).

However, interestingly, our work suggests that urban environments like NYC may not roundly confer anonymity or “invisibility,” particularly in the context of public transit usage, a common marker of lower socioeconomic status in certain geographies (Bhat & Naumann, 2013). In urban spaces, fluid signs of a presumed PWUD identity (e.g., track marks, disheveled appearance or non-normative behavior, etc.) may indeed be magnified and thus render PWUD more vulnerable to critique, which can contribute to internalized stigma (Ezell et al., 2020; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Link & Phelan, 2001; Muncan et al., 2020). Hence, in alignment with the fundamental causes model (Link & Phelan, 1995), urban PWUD, particularly those who are low SES, can be said to potentially have less of the socio-geographic mobility necessary to “avoid” such stigma/social scrutiny (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013).

Continuing, distinctive aspects of the perceived structuring of the built environment (Araya et al., 2006) were shown to be associated with individual-level agency in deciding how and where to use drugs. First, to the matter of where drugs were obtained and used, respondents highlighted the popularity of various contested spaces, chief among them “on the streets,” a broadly conceived public space fundamentally associated with social capital and social location (Anthias, 2013; Toolis & Hammack, 2015). Here, housing (or lack thereof), particularly under the framework of stigma-zoning where PWUD were intentionally excluded from spaces, potently structured the ways that both urban and rural PWUD used drugs. Moreover, a lack of housing made stigma-zoning more palpable and forestalled socio-geographic mobility. Second, for both urban and rural PWUD, drug use, in the context of the built environment, was a shield against overlapping social stressors and environmental pressures, at least temporarily marshaling a psychosocial balance (D. R. Buchanan, 1993; Terry-McElrath et al., 2009). As a point of departure, however, for rural PWUD, as compared to urban PWUD, drug use site selection was more intuitively meant to preclude disclosure to the general public, whereas for urban PWUD, the emphasis was most centrally on stemming law enforcement interactions.

Several limitations to this work should be noted. First, the PWUD who were interviewed were SEP clients. Thus, these individuals are not fully representative of the broader PWUD population and specifically PWUD who may lack access to SEP services and resources or who may lack the readiness to change or simply be disinclined or opposed to using SEPs (Cooper et al., 2011; Green et al., 2010). Second, most participants were middle-aged, and thus the views and experiences of younger PWUD, particularly in consideration of factors shaping drug use patterns, may not have been captured, thus negating our ability to present a more complete “life course” perspective. Future studies should incorporate the perspectives of younger PWUD and PWUD who do not attend SEPs, to broadly contextualize which spatial factors contribute most to the dynamics observed here and to potential derivations.

In summary, this research demonstrates that built environments and social typologies converge and become contested at multiple interactional and relational points, between and among PWUD, and the general public and institutions such as law enforcement. Inequities produced through fluid and historical processes of drug criminalization, specifically those occurring in racist, classist, etc., contexts (Cooper, 2015; Kulesza et al., 2016; Measham, 2002), mold the drug use milieu in similar manners. Respondents illustrated how the rural drug use (acquisition) milieu is more compacted and narrow and thus, in effect, more streamlined. In contrast, the urban drug use milieu was framed as being more complex and cavernous, requiring navigation through multiple layers of visibility (increasing PWUD’s vulnerability to stigma-zoning, etc.). In view of this, drug use behaviors can be said to be encoded and reproduced by various independent and sometimes intersecting micro-and macro-level factors. Further research is needed to characterize opportunities to build-upon the affirmational health and psychosocial benefits generated by SEPs (Bluthenthal, 1998; Muncan et al., 2020) and to implement health, housing, and policing policies that could otherwise help protect spatially marginalized drug use communities.

Highlights.

Core social factors driving drug use are consistent between urban and rural spaces

Drug use site preference is influenced by stigma and identity management processes

Via “stigma zoning,” drug use becomes socio-spatially devalued and policed

Limited housing stability and socio-geographic mobility narrow the drug use milieu

Acknowledgements:

We would like to extend our deepest thanks to the study participants for their time and contributions to this research. We also want to thank the study’s field staff for their efforts.

Funding:

This study was funded through a pilot grant from New York University’s Center for Drug Use and HIV/HCV Research (CDUHR), funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30DA011041), and NYU’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), funded by NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (UL1TR001445).

Abbreviations

- PWUD

People who use drugs

- SEP

Syringe exchange program

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability Statement:

The qualitative interview data and transcripts from this study are not available due to the conditions of the approving institutions’ Institutional Review Boards and the terms of the consent.

REFERENCES

- Ahern J, Stuber J, & Galea S (2007). Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2–3), 188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ST, O’Rourke A, White REL, Smith KC, Weir B, Lucas GM, Sherman SG, & Grieb SM (2019). Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Use Among People Who Inject Drugs in Rural Appalachia: A Qualitative Study. AIDS and Behavior, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthias F (2013). Hierarchies of social location, class and intersectionality: Towards a translocational frame. International Sociology, 28(1), 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Araya R, Dunstan F, Playle R, Thomas H, Palmer S, & Lewis G (2006). Perceptions of social capital and the built environment and mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3072–3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LS, Smith W, Gulley T, & Tomann MM (2019). Community perceptions of comprehensive harm reduction programs and stigma towards people who inject drugs in rural Virginia. Journal of Community Health, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass S (2001). Policing space, policing race: Social control imperatives and police discretionary decisions. Social Justice, 28(1 (83), 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat G, & Naumann RB (2013). Travel-related behaviors, opinions, and concerns of US adult drivers by race/ethnicity, 2010. Journal of Safety Research, 47, 93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon BJ, Robison SB, & Rhodes JLF (2016). Examining the Influence of Risk Factors Across Rural and Urban Communities. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 7(4), 615–638. 10.1086/689355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN (1998). Syringe exchange as a social movement: A case study of harm reduction in Oakland, California. Substance Use & Misuse, 33(5), 1147–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D, Khoshnood K, Stopka T, Shaw S, Santelices C, & Singer M (2002). Ethical dilemmas created by the criminalization of status behaviors: Case examples from ethnographic field research with injection drug users. Health Education & Behavior, 29(1), 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan DR (1993). Social Status Group Differences in Motivations for Drug Use. Journal of Drug Issues, 23(4), 631–644. 10.1177/002204269302300405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard RD, & Johnson GS (2000). Environmentalism and public policy: Environmental justice: Grassroots activism and its impact on public policy decision making. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 555–578. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JA (2010). Avoiding traps in member checking. The Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102— 1113. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Gould A, Pardo B, Reuter P, & Stein BD (2020). Opioids and the Criminal Justice System: New Challenges Posed by the Modern Opioid Epidemic. Annual Review of Criminology, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory, sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chitewere T, Shim JK, Barker JC, & Yen IH (2017). How Neighborhoods Influence Health: Lessons to be learned from the application of political ecology. Health & Place, 45, 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DA, Inagami S, & Finch B (2008). The built environment and collective efficacy. Health & Place, 14(2), 198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AB, Boyd J, Cooper HLF, & McNeil R (2019). The intersectional risk environment of people who use drugs. Social Science & Medicine, 234, 112384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF (2015). War on drugs policing and police brutality. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(8–9), 1188–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Des Jarlais DC, Ross Z, Tempalski B, Bossak B, & Friedman SR (2011). Spatial access to syringe exchange programs and pharmacies selling over-the-counter syringes as predictors of drug injectors’ use of sterile syringes. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1118–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, & Nieweglowski K (2018). Stigma and the public health agenda for the opioid crisis in America. International Journal of Drug Policy, 59, 44–49. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahly DL, & Adair LS (2007). Quantifying the urban environment: A scale measure of urbanicity outperforms the urban-rural dichotomy. Social Science & Medicine, 64(7), 1407–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fine Licht KP (2017). Hostile urban architecture: A critical discussion of the seemingly offensive art of keeping people away. Etikk I Praksis-Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, 2, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Rusch M, Amram O, Chettiar J, Nguyen P, Feng CX, & Shannon K (2014). Piloting a ‘spatial isolation’index: The built environment and sexual and drug use risks to sex workers. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(3), 533–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollar CB (2019). Criminalization and drug “wars” or medicalization and health “epidemics”: How race, class, and neoliberal politics influence drug laws. Critical Criminology, 27(2), 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, & Carlson RG (2009). Down on main street: Drugs and the small-town vortex. Health & Place, 15(1), 247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus PJ, Roddy J, & Greenwald M (2010). “I always kept a job”: Income generation, heroin use and economic uncertainty in 21st century Detroit. Journal of Drug Issues, 40(4), 841–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draus P, Roddy J, & Asabigi K (2015). Streets, strolls and spots: Sex work, drug use and social space in Detroit. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(5), 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C (2011). Networks, resources and agencies: On the character and production of enabling places. Health & Place, 17(1), 149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V, Smith L, & Copenhaver M (2013). Drug addiction stigma in the context of methadone maintenance therapy: An investigation into understudied sources of stigma. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(1), 110–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engen RL, & Steen S (2000). The power to punish: Discretion and sentencing reform in the war on drugs. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1357–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DN, Blount-Hill K-L, & Cubellis MA (2019). Examining housing discrimination across race, gender and felony history. Housing Studies, 34(5), 761–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ezell JM, Walters S, Friedman SR, Bolinski R, Jenkins WD, Schneider J, & Link B (2020). Stigmatize the use, not the user? Attitudes on opioid use, drug injection, treatment, and overdose prevention in rural communities. Social Science & Medicine, 113470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Cagle HH, Davis DC, Fenaughty AM, Kuhrt-Hunstiger T, & Fison SR (1997). Health consequences of rural illicit drug use: Questions without answers. Rural Substance Abuse: State of Knowledge and Issues, 168, 175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. Turning Points in Qualitative Research: Tying Knots in a Handkerchief, 3, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Bluthenthal RN, Singer M, Beletsky L, Grau LE, Marshall P, & Heimer R (2010). Prevalence and predictors of transitions to and away from syringe exchange use over time in 3 US cities with varied syringe dispensing policies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 111(1–2), 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross K, & Wronski J (2019). Helping the homeless: The role of empathy, race and deservingness in motivating policy support and charitable giving. Political Behavior, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree C, Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Piper TM, Miller J, Vlahov D, & Tardiff KJ (2005). The urban built environment and overdose mortality in New York City neighborhoods. Health & Place, 11(2), 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski A, Kunins HV, Huxley-Reicher Z, & Siegler A (2018). Knowledge of the 911 Good Samaritan Law and 911-calling behavior of overdose witnesses. Substance Abuse, 39(2), 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene DE, & Padilla MB (2014). Spatial stigma and health inequality. Critical Public Health, 24(4), 392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, & Galea S (2014). Understanding the Rural-Urban Differences in Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use and Abuse in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e52—9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J, & Higgins DL (2002). Housing and health: Time again for public health action. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza M, Matsuda M, Ramirez JJ, Werntz AJ, Teachman BA, & Lindgren KP (2016). Towards greater understanding of addiction stigma: Intersectionality with race/ethnicity and gender. Drag and Alcohol Dependence, 169, 85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassiter MD (2015). Impossible Criminals: The Suburban Imperatives of America’s War on Drugs. Journal of American History, 102(1), 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Latimore AD, & Bergstein RS (2017). “Caught with a body” yet protected by law? Calling 911 for opioid overdose in the context of the Good Samaritan Law. International Journal of Drug Policy, 50, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Edwards C, Davey-Rothwell MA, & Tobin KE (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 133–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre H, & Nicholson-Smith D (1991). The production of space (Vol. 142). Oxford Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan J (1995). Social Conditions As Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 80. 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. 10.l146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Wells J, Phelan JC, & Yang L (2015). Understanding the importance of “symbolic interaction stigma”: How expectations about the reactions of others adds to the burden of mental illness stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löw M (2006). The social construction of space and gender. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(2), 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Omori M, Roussell A, & Valasik M (2013). Policing the ‘progressive’city: The racialized geography of drug law enforcement. Theoretical Criminology, 17(3), 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Manhica H, Straatmann VS, Lundin A, Agardh E, & Danielsson A (2020). Association between poverty exposure during childhood and adolescence, and drug use disorders and drug-related crimes later in life. Addiction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE, & Syverson J (2019). Race, gender, and homelessness stigma: Effects of perceived blameworthiness and dangerousness. Deviant Behavior, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Massey D (1993). Power-geometry and a progressive sense of place.

- Massey D (2009). Concepts of space and power in theory and in political practice. Documents d’anàlisi Geogràfica, 55, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, Mutter R, Davis CS, Wheeler E, Pemberton M, & Kral AH (2018). Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addictive Behaviors, 86, 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLuckie C, Pho MT, Ellis K, Navon L, Walblay K, Jenkins WD, Rodriguez C, Kolak MA, Chen Y-T, & Schneider JA (2019). Identifying Areas with Disproportionate Local Health Department Services Relative to Opioid Overdose, HIV and Hepatitis C Diagnosis Rates: A Study of Rural Illinois. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicar D, Moschion J, & van Ours JC (2015). From substance use to homelessness or vice versa? Social Science & Medicine, 136, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measham F (2002). “Doing gender”—“Doing drugs”: Conceptualizing the gendering of drugs cultures. Contemporary Drug Problems, 29(2), 335–373. [Google Scholar]

- Monnat SM, & Rigg KK (2018). The opioid crisis in rural and small town America.

- Moore D, & Fraser S (2006). Putting at risk what we know: Reflecting on the drug-using subject in harm reduction and its political implications. Social Science & Medicine, 62(12), 3035–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muncan B, Walters SM, Ezell J, & Ompad DC (2020). “They look at us like junkies”: Influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J (2001). Homelessness amongst drug users: A double jeopardy explored. International Journal of Drug Policy, 12(4), 353–369. [Google Scholar]

- Neely B, & Samura M (2011). Social geographies of race: Connecting race and space. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 34(11), 1933–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak AL, & Giurgescu C (2017). The built environment and birth outcomes: A systematic review. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 42(1), 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum MC (2009). Hiding from humanity: Disgust, shame, and the law. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Halkitis PN, & Kiang ΜV (2013). Perceived public stigma and stigmatization in explaining lifetime illicit drug use among emerging adults. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(6), 516–525. [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Kiang ΜV, & Halkitis PN (2012). Predictors of stigmatization towards use of various illicit drugs among emerging adults. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(3), 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear VA, Ponicki WR, Gaidus A, Keyes KM, Martins SS, Fink DS, Rivera-Aguirre A, Gruenewald PJ, & Cerdá M (2019). Urban-rural variation in the socioeconomic determinants of opioid overdose. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 195, 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KS (2020). From Overdose to Crime Scene: The Incompatibility of Drug-Induced Homicide Statutes with Due Process. Duke Law Journal, 70(3), 659–704. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido L, Kohl E, & Cotton N-M (2016). State regulation and environmental justice: The need for strategy reassessment. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(2), 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Boone L, Scheidell JD, Mateu-Gelabert P, McGorray SP, Beharie N, Cottler LB, & Khan MR (2016). The relationships of childhood trauma and adulthood prescription pain reliever misuse and injection drug use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 169, 190–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redonnet B, Chollet A, Fombonne E, Bowes L, & Melchior M (2012). Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drug use among young adults: The socioeconomic context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 121(3), 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2002). The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13(2), 85–94. 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Lilly R, Fernández C, Giorgino E, Kemmesis UE, Ossebaard HC, Lalam N, Faasen I, & Spannow KE (2003). Risk factors associated with drug use: The importance of‘risk environment.’ Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 10(4), 303–329. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson L, Wood E, & Kerr T (2013). The impact of social, structural and physical environmental factors on transitions into employment among people who inject drugs. Social Science & Medicine, 76, 126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger R (2020). On hostile design: Theoretical and empirical prospects. Urban Studies, 57(4), 883–893. [Google Scholar]

- Shim JK (2010). Cultural Health Capital: A Theoretical Approach to Understanding Health Care Interactions and the Dynamics of Unequal Treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1), 1–15. 10.1177/0022146509361185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmel G (2012). The metropolis and mental life. In The urban sociology reader (pp. 37–45). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C (2014). Injecting drug use and the performance of rural femininity: An ethnographic study of female injecting drug users in rural North Wales. Critical Criminology, 22(4), 511–525. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CB (2010). Socio-spatial stigmatization and the contested space of addiction treatment: Remapping strategies of opposition to the disorder of drugs. Social Science & Medicine, 70(6), 859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swope CB, & Hernández D (2019). Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 243, 112571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, & Johnston LD (2009). Reasons for Drug Use among American Youth by Consumption Level, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity: 1976–2005. Journal of Drug Issues, 39(3), 677–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Opioid Crisis in Illinois: Data and the State’s Response. (2017). [Google Scholar]

- Toolis EE, & Hammack PL (2015). The lived experience of homeless youth: A narrative approach. Qualitative Psychology, 2(1), 50. [Google Scholar]

- Tuazon E, Kunins ΗV, Allen B, & Paone D (2019). Examining opioid-involved overdose mortality trends prior to fentanyl: New York City, 2000–2015. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N, & Barnes M (2009). Nowhere to go: How stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 4(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva K, Pereira G, Knuiman M, Bull F, Wood L, Christian H, Foster S, Boruff BJ, Beesley B, & Hickey S (2013). The impact of the built environment on health across the life course: Design of a cross-sectional data linkage study. BMJ Open, 3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SM, Coston B, Neaigus A, Rivera AV, Starbuck L, Ramirez V, Reilly KH, & Braunstein SL (2020). The role of syringe exchange programs and sexual identity in awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for male persons who inject drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 77, 102671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SM, Rivera AV, Starbuck L, Reilly KH, Boldon N, Anderson BJ, & Braunstein S (2017). Differences in awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis among groups at-risk for HIV in New York State: New York City and Long Island, NY, 2011–2013. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 75, S383–S391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Silva K, Kecojevic A, Schrager SM, Bloom JJ, Iverson E, & Lankenau SE (2013). Coping and emotion regulation profiles as predictors of nonmedical prescription drug and illicit drug use among high-risk young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 132(1–2), 165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]