Abstract

Purpose of Review

Both chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and T cell–engaging antibodies (BiAb) have been approved for the treatment of hematological malignancies. However, despite targeting the same antigen, they represent very different classes of therapeutics, each with its distinct advantages and drawbacks. In this review, we compare BiAb and CAR T cells with regard to their mechanism of action, manufacturing, and clinical application. In addition, we present novel strategies to overcome limitations of either approach and to combine the best of both worlds.

Recent Findings

By now there are multiple approaches combining the advantages of BiAb and CAR T cells. A major area of research is the application of both formats for solid tumor entities. This includes improving the infiltration of T cells into the tumor, counteracting immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment, targeting antigen heterogeneity, and limiting off-tumor on-target effects.

Summary

BiAb come with the major advantage of being an off-the-shelf product and are more controllable because of their half-life. They have also been reported to induce less frequent and less severe adverse events. CAR T cells in turn demonstrate superior response rates, have the potential for long-term persistence, and can be additionally genetically modified to overcome some of their limitations, e.g., to make them more controllable.

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor, Bispecific antibody, Immunotherapy, Adoptive T cell therapy, T cell redirection, Cancer

Introduction

In efforts to harness T cells in the fight against cancer, several immunotherapeutic approaches have been successfully developed. Among others, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and T cell–engaging bispecific antibodies (BiAb) have gained approval by regulatory agencies and are currently being used to treat patients with hematological malignancies.

Both BiAb and CAR T cells use antibodies or antibody fragments to redirect T cells to specific tumor-associated antigens, which is a shared facet of these major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–independent approaches. Their clinical application has achieved unprecedented response rates in patients with relapsed or refractory B cell malignancies, although in only partially overlapping indications [1, 2]. Both can induce severe adverse events like cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity. Further, a large proportion of patients inevitably relapse, and the efficacy of BiAb or CAR T cells targeting solid tumors remains limited [3••].

BiAb are recombinant proteins with antigen-binding antibody domains both for T cell–specific and tumor-associated antigens. When infused into the patient, they can redirect endogenous T cells to kill cancer cells expressing a specific target [4].

CAR T cells are usually generated by genetically modifying patient-derived T cells ex vivo before their adoptive transfer back into the patient. A CAR is a synthetic receptor consisting of a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) linked to a transmembrane domain and intracellular T cell–activating domains. CAR binding to the antigen on the tumor cell surface activates the CAR T cell and triggers a T cell response against antigen-expressing tumor cells [5•].

In this review, we present and describe different formats of BiAb and CAR T cell therapies. We compare BiAb with CAR T cells, highlighting the differences and similarities, as well as the advantages and limitations of either strategy. In line with this, we outline preclinical and clinical strategies that are currently in development to overcome therapeutic limitations and boost efficacy.

T Cell–Engaging Bispecific Antibodies

The term BiAb will be used in this review for all antibody-based molecules containing antigen-binding sites for both T cell and tumor-associated antigens. Generally, BiAb can be divided into BiAb containing an Fc domain and Ab fragment–based ones. Labrijn et al. provide an extensive overview of the different BiAb formats [6•].

Most BiAb with an Fc domain bear mutations introduced to abolish Fc-mediated effector functions such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, phagocytosis, and complement-dependent cytotoxicity, given that they can result in off-target immune cell activation [6•, 7, 8]. However, these BiAb are usually designed to maintain binding of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) which protects them from degradation, thus conferring a long plasma half-life (days) compared to the plasma half-life of fragment-based BiAb (hours) [9–13]. This can be advantageous as they can be administered in a bolus injection, whereas fragment-based BiAb need to be infused continuously. The drawback is that they are more slowly eliminated from the circulation in the occurrence of adverse events. Fragment-based BiAb can be produced relatively easily at high yields and low costs but are more prone to aggregation or stability issues [14]. Generally, they exhibit faster tissue penetration than Fc-containing BiAb, including crossing of the blood-brain barrier. This distinction is a double-edged sword, as it may increase patient susceptibility to neurotoxicity, while being more favorable for the treatment of brain tumors [15•]. The opposite applies to larger BiAb with an Fc domain, which are actively exported from the brain by transcytosis mediated by FcRn [9].

BiAb valency, i.e., the number of binding arms, as well as the affinity of the individual binding domains can greatly influence the functionality and biodistribution of a BiAb. In the case of a CD3-binding BiAb, one binding site for CD3 is preferred to prevent unwanted T cell activation by CD3 cross-linking [2••]. A reduced affinity for CD3 can minimize BiAb trapping in tissues containing a high number of T cells [6•, 16, 17]. In addition, BiAb with reduced potency can be administered at higher doses to augment efficacy while limiting adverse events. In contrast, two tumor antigen–binding domains can increase selective recognition and killing of highly antigen-expressing tumor cells by increasing the avidity (through the simultaneous binding of both arms) while sparing healthy cells expressing the antigen at lower levels [7, 18–20]. In addition, lowering the affinity for both the CD3 and tumor antigen–binding domains have also been shown to widen the therapeutic window [21].

In 2009, the first BiAb was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Although more than 40 BiAb are currently in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials for both hematological and solid cancers, to date only two molecules have gained regulatory approval for cancer therapy [22]. Removab® (catumaxomab), an anti-CD3 × anti-epithelial cellular adhesion molecule (EpCAM) BiAb containing an Fc domain, was intraperitoneally applied to treat malignant ascites in ovarian cancer but was withdrawn from the market in 2017 for commercial reasons.

Blincyto® (blinatumomab), an anti-CD3 × anti-CD19 fragment–based bispecific T cell engager (BiTE®), is the only BiAb currently on the market. It gained approval for B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2014 and by the European Medicines Agency in 2015. Lacking an Fc domain, and thus not protected from degradation by FcRn, it has a half-life of approximately 1 to 2 h and can therefore only be administered via a continuous intravenous infusion [10, 11]. Complete response rates ranged from 36 to 69% in clinical trials (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison between CAR T cells and BiAb

| CAR T cells | BiAb | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | T cells genetically engineered to express a synthetic receptor consisting of an extracellular scFv linked to intracellular activation and co-stimulatory domains | Recombinant soluble protein with binding domains for a T cell and a tumor antigen |

| Signals for T cell activation | Signal 1 (CD3ζ), signal 2 (CD28, 4-1BB; in 2nd and 3rd generation CAR constructs), signal 3 (cytokine stimulation ex vivo) | Signal 1 (CD3ζ) |

| Immune synapse | Atypical [37] | Classical [36] |

| Effector cells | Engineered CD8+ and CD4+ T cells; less differentiated T cells show better efficacy in vivo | Endogenous CD8+ and CD4+ T cells; mainly antigen-experienced T cells kill |

| Manufacturing | Autologous CAR T cells: individual production for each patient | Off-the-shelf product |

| Allogeneic CAR T cells: production in batches from healthy donor T cells (investigational use only) | ||

| Prone to manufacturing variability (T cell subset composition, transduction efficiency, number of viable T cells) and failure | ||

| Pre-treatment | Lymphocyte apheresis for collecting T cells (for autologous T cells), lymphodepletion chemotherapy before CAR T cell infusion | Dexamethasone to limit CRS and neurotoxicity |

| Dosing | Single dose | Multiple dosing, for short half-life formats continuous infusion |

| Costs | Up to 320,000 € in Germany [63] | Up to 293,000 € in Germany [64] |

| Regulatory approval | Kymriah: r/r B cell precursor ALL patients up to 25 years (FDA 2017, EMA 2018), adult patients with large B cell lymphoma (FDA and EMA 2018) [25, 27] | Blinatumomab: r/r B cell precursor ALL (FDA 2014, EMA 2015 (only Philadelphia chromosome–negative ALL)), B cell precursor ALL with minimal residual disease (FDA 2018, EMA 2019 (only adults)) [65, 66] |

| Yescarta: adult patients with large B cell lymphoma (FDA 2017, EMA 2018) [26, 28] | ||

| Tecartus: adult patients with r/r mantle cell lymphoma (FDA and EMA 2020) [29, 30] | ||

| Complete response rates (CR/CRh/CRi) | Adult B cell ALL: 83 to 93% [67–69] | Adult B cell ALL: 36 to 69% [76–80] |

| Pediatric B cell ALL: 70 to 94% [70–73] | ||

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma: 40 to 57% [52, 53, 74, 75] | ||

| Mantle cell lymphoma: 67% [31] | ||

| Relapse rates (% of complete responders) | Adult B cell ALL: 12 to 61% [68, 69] | Adult B cell ALL: 40 to 70% [76–78, 80] |

| Pediatric B cell ALL: 26 to 40% [70–72] | ||

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma: 21% [75] | ||

| CD19-negative relapse (% of all relapses) | B cell ALL: 16 to 68% [69–72] | Adult B cell ALL: 8 to 30% [76, 81] |

| Toxicities | More frequent and severe CRS (≥ grade 3: 13 to 47%) and neurotoxicity (≥ grade 3: 5 to 50%), on-tumor off-target effects (B cell aplasia when targeting CD19) [52, 53, 68–71, 73, 75] | CRS (≥ grade 3: 2 to 6%) and neurotoxicity (≥ grade 3: 7 to 17%), on-tumor off-target effects (B cell aplasia when targeting CD19) [76–80] |

Other BiAb currently under clinical investigation include, e.g., BiTE molecules targeting CD20 in chronic lymphoblastic leukemia, CD33 in acute myeloid leukemia, and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) in multiple myeloma [15•].

Beyond BiAb, CAR T cells comprise a promising arm of cancer immunotherapy which is introduced in the next section.

CAR T Cells

CAR structure typically consists of an extracellular antigen recognition domain (in most cases an antibody-derived scFv) connected via a spacer and a transmembrane domain to one or more intracellular signaling domains [23•]. These domains determine the type of signal transmitted after the scFv engages its target. While first generation CAR constructs can only propagate signal 1 via the intracellular CD3ζ chain of the TCR complex, second-generation CAR constructs have an additional co-stimulatory domain, in most cases the intracellular domain of CD28 or 4-1BB, through which signal 2 is transmitted. In third-generation CAR constructs, two co-stimulatory domains are included, further augmenting the co-stimulus.

Individual CAR features can greatly impact CAR T cell function, including T cell phenotype, persistence, tonic signaling, and on-target off-tumor effects. For example, lowering the affinity of the scFv can help CAR T cells discern tumor cells differentially expressing the antigen from healthy cells expressing it at lower levels, thus limiting on-target off-tumor responses [24]. In addition, exchanging the co-stimulatory domain has been shown to impact T cell activation as well as the in vivo persistence of CAR T cells (as observed when swapping the CD28 co-stimulus for 4-1BB) [23•]. Also, the transduction of specific T cell subsets, the method of transgene delivery, and selection of the promoter can influence the efficacy and adverse effects of CAR T cells [1, 23•]. This topic has recently been reviewed in more detail elsewhere [23•].

After clinical trials showed dramatic response rates, two CAR T cell products targeting the B cell antigen CD19 received marketing authorization by the FDA in 2017 and the EMA in 2018 for relapsed or refractory (r/r) B cell malignancies after two or more lines of systemic treatment [25–28]. Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) is approved for r/r B cell precursor ALL and large B cell lymphoma, and Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for large B cell lymphoma. Both use second-generation CAR constructs but differ in their co-stimulatory domains: 4-1BB for Kymriah and CD28 for Yescarta. Complete response rates in ALL range from 70 to 94% but are lower in diffuse large B cell lymphoma with 40 to 57% (see Table 1).

In addition, Tecartus (brexucabtagene autoleucel) has been approved in 2020 by the FDA and EMA for r/r mantle cell lymphoma [29, 30]. It utilizes the same anti-CD19 CAR as Yescarta and achieved a complete response in 67% of patients in the clinical trial that led to its regulatory approval [31].

More than 200 CAR T cell products are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for a variety of different targets in both hematological and solid malignancies, with more than 40 trials started in 2020 alone [32, 33]. For example, anti-BCMA CAR T cells have shown promising results in multiple myeloma patients and are currently under regulatory review [34]. Most studies use patient-derived autologous T cells, while a minority uses allogeneic T cells from healthy donors. Allogeneic T cells on the one hand hold the promise of a standardized off-the-shelf product with lower costs and the added option for repeated infusions. On the other hand, they need to include additional genetic modifications to lower the risk of graft-versus-host disease and alloimmunization [3••].

There is certainly more to come from CAR T cells as anti-cancer therapeutics. This growing potential, and how it compares to that of BiAb therapy, are outlined below.

Comparison of CAR T Cells and BiAb

Both CAR and BiAb approaches are distinctly advantageous in their own right. Although a clinical trial comparing these approaches within the same cohort for the same indication is still lacking, it remains important to compare and contrast these approaches. This is what we aim to outline in this section, highlighting differences in their mode of action, manufacturing, and clinical applications.

Signals Provided for T Cell Activation

Optimal T cell activation requires three signals: signal 1 is normally provided by the T cell receptor (TCR)-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) interaction, signal 2 through a co-stimulatory receptor on the T cells binding its ligand on antigen-presenting cells or target cells, and signal 3 by cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-2, IL-7, and IL-15 [3••, 35]. CAR activation itself provides signal 1 through the CD3ζ intracellular domain and signal 2 through the co-stimulatory domains. BiAb only provide signal 1 by activating the CD3 receptor [3••, 35]. As CAR T cells are stimulated with cytokines during manufacturing, thereby providing signal 3, they have an additional advantage regarding T cell activation [35]. This may contribute to the fact that, based on the currently approved products, CAR T cells are considered more efficacious than blinatumomab (see Table 1).

Immune Synapses and Killing Mechanisms

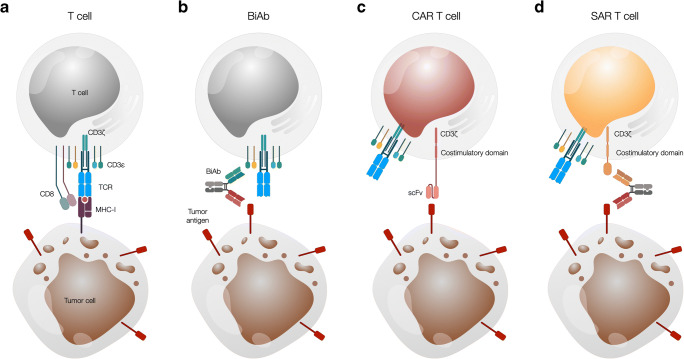

BiAb-induced immune synapses formed between T cells and antigen-expressing target cells are very similar to the classical cytolytic immune synapse formed via the TCR-MHC interaction (Fig. 1a, b) [36]. In contrast, CAR T cells form an atypical synapse which is smaller and less organized and induces faster, stronger, and shorter signaling compared to the classical immune synapse (Fig. 1c). It also mediates faster target cell lysis by accelerated recruitment of lytic granules to the synapse and more rapid T cell detachment [37].

Fig. 1.

Schematic presentation of the interaction between T cells and tumor cells via a TCR, a BiAb, a CAR, and a SAR in combination with a BiAb. a A CD8+ T cell recognizes a tumor cell presenting a peptide from a tumor antigen on MHC class I via its TCR. b A BiAb mediates T cell recognition of a tumor cell by binding to both an antigen on the T cell surface, most commonly CD3, and a tumor cell surface antigen. c A T cell genetically modified to express a CAR binds a surface antigen expressed on the tumor cell via the scFv domain of the CAR in an MHC-independent manner. d A SAR-transduced T cell interacts with a tumor cell via a BiAb binding the SAR extracellular domain and a tumor cell surface antigen. BiAb, T cell redirecting bispecific antibody; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; SAR, synthetic agonistic receptor; TCR, T cell receptor

CAR T cells can kill antigen-expressing tumor cells via the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes, through the Fas-FasL pathway, and by sensitizing the tumor stroma following the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [5•]. CAR activation was shown to upregulate FasL on T cells [38], and interferon-γ stimulation leads to Fas upregulation on some colon carcinoma cell lines and increased their susceptibility to CAR T cell–mediated killing [39]. BiAb are known to induce cytotoxicity via perforin and granzyme B [40]. Both BiAb and CAR T cells can mediate serial tumor cell killing [3••]. Interestingly, both strategies could mediate lysis of antigen-negative tumor cells that were in direct contact with antigen-positive cells, most likely involving the Fas-FasL axis in both cases [41, 42]. This suggests that Fas-FasL–based killing can also be mediated by BiAb.

Antigen Spreading

Following antigen-specific tumor cell lysis, the released antigens may be taken up by dendritic cells and cross-presented to T cells, priming additional T cell responses in a process known as antigen or epitope spreading. There is evidence demonstrating that tumor-specific CD8+ T cells can mediate this process [43]. After treatment with mesothelin-specific CAR T cells, novel antibodies in two cancer patients could be detected using high-throughput serological analysis and immunoblotting. Both patients showed clinical antitumor activity following treatment despite not receiving lymphodepletion therapy before CAR T cell infusion [44]. Another study could show that clonal expansion of endogenous T cells could be induced by anti-mesothelin CAR T cells in several solid tumor patients, which was detected by deep sequencing of the TCR beta chain. This was not observed in patients receiving lymphodepletion prior to CAR T cell transfer [45]. Taken together, these studies show that CAR T cells can induce broadening of humoral responses as well as T cell epitope spreading in patients, effects that appear to be hampered by lymphodepletion. An example of epitope spreading has also been reported for BiAb therapy. A BiTE targeting Wilms’ tumor protein (WT1) led to the expansion of secondary T cell clones (with specificity for tumor-associated antigens other than WT1) in in vitro co-cultures of patient PBMCs with autologous tumor cells [46].

CD4+/CD8+ T Cells and T Cell Phenotype

For both CAR T cells and BiAb, CD4+ T cells not only provide support for CD8+ T cells but have been shown to be directly cytotoxic [47•], although in a slower fashion. Further, CD4+ CAR T cells are less prone to activation-induced cell death [1•] and persist longer in vivo [48].

While less differentiated CAR T cells (naïve, stem cell memory, central memory) show better efficacy in vivo, it is mainly antigen-experienced T cells (effector memory) that mediate lysis via BiAb [2••, 47•, 49•]. Interestingly, BiAb have even been shown to redirect regulatory T cells to kill tumor cells [50].

Manufacturing

One of the greatest differences between the two strategies is the manufacturing process. Thus far, CAR T cells have to be produced individually for each patient, a costly and laborious process (2 to 4 weeks) spanning lymphocyte apheresis to reinfusion, during which the disease may progress [49•]. After leukapheresis, patient T cells are isolated and activated before they are genetically modified with the CAR construct and expanded [51]. After quality testing, the product is shipped to the patient, who is pre-conditioned with lymphodepleting chemotherapy before CAR T cell infusion.

Lymphodepletion is not required prior to BiAb treatment. Additional obstacles for CAR T cell therapy include the challenge of achieving sufficient T cell numbers following leukapheresis and ex vivo expansion of the transduced T cells [52, 53].

In contrast, BiAb are off-the-shelf biologics that are easier to produce recombinantly and purify.

They bear the additional advantage of facile dose management, which is often challenging or not possible in the CAR T cell setting. However, based on the currently approved products, CAR T cells seem to be more efficacious than blinatumomab (see Table 1).

T Cell Expansion and Persistence

Another major difference between CAR T cells and BiAb is the reliance on T cell expansion and persistence. While CAR T cells greatly rely on CAR T cell expansion, which can be higher than 1000-fold [54], T cell expansion is less important for BiAb because any antigen-experienced T cell can be engaged for tumor cell killing [47•]. With respect to recurrence after successful therapy, CAR T cells possess the advantage that they can engraft long term in the patient and thus attack recurring tumors, while BiAb action is abolished shortly after the last infusion [47•]. The impact of gene editing approaches on the production of a more refined CAR T cell product will broaden this disparity in years to come [55].

Adverse Events

There are two main adverse events, one being CRS, a systemic response caused by antigen-specific T cell activation and subsequent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The other is neurotoxicity, otherwise referred to as immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) [56]. CRS is generally more frequent and severe in CAR T cell therapy (see Table 1), often occurring in the first days after treatment and correlating with disease burden [3••, 57, 58]. CRS and ICANS are currently managed using an IL-6 receptor-blocking antibody (tocilizumab) and corticosteroids. To reduce these adverse events, pre-treatment with dexamethasone and step-up dosing have proven successful for blinatumomab, while split dosing has been tested in the CAR T cell setting [3••]. In addition, on-target off-tumor toxicities can be a major concern that depends on the expression profile of the targeted antigen in healthy tissues. In the case of B cell malignancies treated with anti-CD19 BiAb or CAR T cells, the consequent B cell aplasia has been largely manageable by the infusion of immunoglobulins [59, 60].

Relapse

Despite high initial response rates, many patients relapse after anti-CD19 CAR T cell or blinatumomab treatment (see Table 1). However, the rate of CD19-negative relapses after initially successful therapy seems to be higher in CAR T cell–treated patients than in blinatumomab-treated patients (see Table 1). It is important to remember that blinatumomab is often used as a bridge to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Such a transplantation would rather be the choice (if available) in case of relapse in spite of CAR T cell treatment [61, 62]. Along these lines, differences in antigen-loss variants might simply be a reflection of a lower treatment pressure with blinatumomab compared to CAR T cells [2••]. Many approaches that are currently in development aim to improve either therapy alone or combine the best of both approaches in efforts to develop novel solutions. These perspectives and their potential are discussed in the final section below.

CR complete remission, CRh CR with partial hematologic recovery, CRi CR with incomplete hematologic recovery

Future Perspectives

Despite the high efficacy of CAR T cell and BiAb treatments, several hurdles continue to hamper their broader applicability. To tackle treatment-related toxicity, which has been especially problematic for CAR T cells (see Table 1), many approaches have been developed to improve their safety by making them more controllable (see Table 2). In addition, many CAR T cell– or BiAb-treated patients relapse due to antigen escape and, in the case of CAR T cells, limited persistence of the transferred T cells. This, alongside tumor antigen heterogeneity, has prompted the development of modular approaches combining T cells engineered with a CAR-like synthetic receptor and BiAb adapters targeting this receptor and a tumor antigen (see Table 2). These have the flexibility to redirect engineered T cells toward multiple targets [82].

Table 2.

Limitations of CAR T cells and BiAb therapy and strategies to overcome them

| Strategy | Examples | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improving controllability | |||

| CAR T cells | Suicide receptor that is targetable by already approved monoclonal antibodies |

Truncated EGFR [93] |

In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04318678) In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT01815749, NCT02051257) |

| Suicide gene induced by small molecule | iCasp9 [94•] | Phase 1 clinical trials completed, but no results published yet (NCT02107963, NCT03958656), more phase 1 trials ongoing | |

| HSV thymidine kinase [95] | Preclinical results [95] | ||

| Small molecule–controlled CAR expression/activity |

CAR subunit dimerizing agent [96, 97] Dasatinib [98] SWIFF CAR [99] PROTAC compound [100] |

In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04650451) In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04603872) Preclinical results [99] Preclinical results [100] |

|

| Modular CAR platforms with bispecific adaptor molecule |

UniCAR [83•] SUPRA CAR [84•] Switch CAR [85•] SAR [86•] |

In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04633148, NCT04230265) Preclinical results [84•] In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04450069) Preclinical results [86•] |

|

| BiAb | Short half-life | Blinatumomab [10, 11] | FDA and EMA approved [65, 66] |

| Dosing | Step-up dosing [57, 58] | Clinical application [101] | |

| Modular BiAb | UniMab [83•] | Preclinical results [83•] | |

| Increasing T cell persistence | |||

| CAR T cells | More naïve T cell subsets |

Stem cell memory [102] Naïve, central memory [103] |

In phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT03288493) In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT02706405, NCT02146924) |

| Using co-stimulatory domains favoring persistence |

ICOS [106] CD27 [107] Point-mutated CD28 [108] |

Preclinical results [106] Preclinical results [107] Preclinical results [108] |

|

| Ratio CD4+ to CD8+ T cells | 1:1 ratio [68] | Successful in phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT01865617 [68, 109]) | |

| Co-expression of 4-1BBL on CD28 CAR T cells | [105] | In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03085173) | |

| Incorporating cytokine signaling | IL-2 receptor β-chain + STAT3-binding motif [110] | Preclinical results [110] | |

| Gene editing | Tet2 disruption [111] | Case report and preclinical results [111] | |

| Modular CAR platforms with bispecific adaptor molecule dosing to favor memory formation | [87•] | Preclinical results [87•] | |

| Combination with oncolytic virus, e.g., also expressing cytokines | Oncolytic virus expressing IL-15 & RANTES [112] | In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03740256) (without cytokines) | |

| Reducing on-target off-tumor effects | |||

| CAR T cells | Affinity tuning | [24] | Preclinical results [24] |

| Logic gating |

iCAR [115] |

Preclinical results [113, 114] Preclinical results [115] |

|

| Conditional CAR expression |

SynNotch CAR [116] HIF-CAR [117] |

Preclinical results [116] Preclinical results [117] |

|

| Masking of antigen-binding site by peptide cleavable by tumor-associated protease | Masked CAR [118] | Preclinical results [118] | |

| BiAb | Affinity tuning | [21, 119] | Preclinical results [21, 119] |

| Split BiAb: CD3-binding site formed when both halves bind tumor antigens | Split BiAb [120•] | Preclinical results [120•] | |

| Masking of antigen-binding site by peptide cleavable by tumor-associated protease |

Probody [121] Coiled-coil masking [122] |

Preclinical results [121] Preclinical results [122] |

|

| Targeting antigen heterogeneity and antigen escape | |||

| CAR T cells | Mixing multiple CAR T cell products | Anti-EGFR + anti-CD133 [123] | Preclinical results [123] |

| Transduction of T cells with multiple CAR constructs |

Anti-CD19 + anti-CD123 [124] Anti-HER2 + anti-IL-13Rα2 [125] Anti-BCMA + anti-CS1 [126] |

Preclinical results [124] Preclinical results [125] In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04156269) |

|

| Bispecific (tandem) CAR constructs |

Anti-HER2 + anti-IL-13Rα2 [127] Anti-CD19 + anti-CD22 [128] Anti-CD19 + anti-CD20 [129] |

Preclinical results [127] Successful in case report [128], in phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04034446, NCT03919526) Successful in phase 1 and phase 1/2 clinical trials (NCT03019055 [129], NCT03097770 [130]), more phase 1 clinical trials ongoing |

|

| Modular CAR platforms with multispecific adaptor molecules | Anti-CD33 + anti-CD123 [131] | Preclinical results [131] | |

| BiAb | Combining multiple BiAb, multispecific BiAb | Anti-PSMA + anti-PSCA [132] | Preclinical results [132] |

| CAR T cells + BiAb | CAR T cells secreting BiAb | Anti-EGFRvIII CAR + anti-EGFR BiTE [88•] | Preclinical results [88•] |

| CAR T cells + oncolytic virus secreting BiAb | Anti-FR-α CAR + anti-EGFR BiTE [133] | Preclinical results [133] | |

| Increasing T cell infiltration | |||

| CAR T cells | Expression of chemokine receptors |

CCR4 [134] CCR2b [135] CXCR2 [136] |

In phase 1 clinical trial (with anti-CD30 CAR T cells) (NCT03602157) Preclinical results [135] Preclinical results [136] |

| CAR targeting tumor stroma | Anti-FAP CAR [137] | In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03932565) | |

| Expression of extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes | Heparanase [138] | Preclinical results [138] | |

| Expression of cytokines | IL-7 and CCL19 [139] | In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT03932565, NCT04381741) | |

| Combination with oncolytic virus, e.g., also expressing cytokines |

Oncolytic virus expressing IL-15 and RANTES [112] Oncolytic virus expressing IL-2 and TNF-α [140] |

In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT03740256) (without cytokines) | |

| BiAb | Combination with oncolytic virus | [141] | Preclinical results [141] |

| Counteracting immunosuppression | |||

| CAR T cells | Combination with checkpoint-blocking antibodies |

Anti-PD-1 [142] Anti-PD-L1 [143] |

Successful in phase 1 clinical trials (ChiCTR-ONN-16009862/ChiCTR1800019288 [142], NCT03726515), more phase 1 clinical trials ongoing Successful in phase 1 clinical trial (NCT02926833) [143], more phase 1 and phase 1/2 clinical trials ongoing |

| Gene silencing of inhibitory receptors |

PD-1 [144] Fas [145] A2AR [146] |

In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT03545815, NCT04213469) Preclinical results [145] Preclinical results [146] |

|

| Co-transduction with dominant-negative decoy receptors (DNR) |

TGF-β DNR [147] PD-1 DNR [148] Fas DNR [149] |

In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT03089203, NCT04227275) In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04577326) Preclinical results [149] |

|

| Co-transduction with switch receptor |

PD-1-CD28 [150] IL-4R-IL-7R [151] |

In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT02937844, NCT03932955) Preclinical results [151] |

|

| CAR T cells secreting checkpoint-blocking antibodies |

Anti-PD-L1 [152] Anti-PD-1 [153] |

In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04556669) In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04489862, NCT03182803) |

|

| CAR T cells expressing cytokines (TRUCK) |

IL-12 [154] IL-15 [155] IL-18 [156] |

In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT03542799, NCT02498912) In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT04377932, NCT04715191) In phase 1 clinical trial (NCT04684563) |

|

| Combination with an oncolytic virus expressing checkpoint-blocking antibody | Oncolytic virus expressing PD-L1 blocking mini-body [157] | Preclinical results [157] | |

| BiAb | Combination with checkpoint blockade | Anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1/anti-CTLA-4 [158, 159] | In phase 1 clinical trials (NCT02879695, NCT03792841) |

| Combination with bispecific 4-1BB agonists |

4-1BBL-anti-FAP + anti-CD3-anti-CEA 4-1BBL-anti-CD19 + anti-CD3-anti-CD20 [160•] |

Preclinical results [160•] | |

| Trispecific antibody targeting CD3, tumor antigen, and checkpoint molecule | CiTE [90•] | Preclinical results [90•] | |

Among these platforms are the universal CAR (UniCAR) [83•], split universal and programmable (SUPRA) CAR [84•], switch CAR [85•], and the synthetic agonistic receptor (SAR) developed by our lab (Fig. 1d) [86•]. The activity of the modular CAR T cell can be controlled by the affinities of the two binding sites, as well as the half-life and dosing of the BiAb to limit side effects while retaining antitumor efficacy.

In addition, multiple tumor antigens can be simultaneously or sequentially targeted to address antigen heterogeneity and reduce antigen escape [82]. Moreover, by administering decoys for the CAR adaptors, their activity can be controlled even more tightly [84•]. Interestingly, Viaud et al. could enhance memory T cell formation by including “rest” phases between dosing cycles of the CAR adapter [87•]. It is important to note that while advantageous in terms of controllability, short half-life formats of BiAb mean that regular infusions will be required. Combining CAR T cells and BiAb will likely present hurdles in the form of practicality and cost. Therefore, CAR adaptors will most practically be useful in the context of an “off-the-shelf” universal allogeneic CAR T cell line that can be combined with different adaptors for different tumor antigens.

Translating the success of BiAb and CAR T cell therapies to solid cancer indications poses additional challenges. As a result, attempts to improve T cell recruitment into the tumor render T cells more resistant to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and target antigen heterogeneity among tumor cells are currently underway (see Table 2). One noteworthy strategy presented by Choi and colleagues employs engineered CAR T cells to secrete BiAb targeting a second tumor antigen to treat glioblastoma. They could show this to be a promising approach in a mouse model which shows antigen-negative relapse when CAR T cells alone are employed [88•]. Trafficking of CAR T cells may be enhanced by equipping them with, e.g., chemokine receptors for chemokines expressed in the tumor [89•]. Trispecific antibodies targeting CD3, a tumor antigen, and a checkpoint molecule have been shown to counteract immunosuppression [90•].

Table 2 provides an overview of the current strategies being developed to overcome the aforementioned challenges of CAR T cells and BiAb.

Conclusion

Despite the apparent overlap between CAR T cell and BiAb approaches (such as their application to target the same antigen for some of the same indications), it remains clear that both therapies offer distinct benefits. The emergence of treatments that combine the best of both the CAR and BiAb worlds highlights this, as shown by SAR T cells that utilize BiAb to enable selective and modular control over T cell activation.

Nevertheless, both CAR and BiAb approaches continue to be developed in their own right, with advancements addressing the shortcomings of either approach. Combining BiAb with bispecific 4-1BB agonists is one such example, where the lack of a co-stimulatory signal 2 is effectively overcome. For CAR T cells, various approaches have been developed by either limiting their activation to the tumor microenvironment, like the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) or synthetic Notch (SynNotch) CAR, or by making their activation more controllable from the outside, e.g., by administering small molecules or antibodies to activate or inhibit CAR T cell activity.

Due to the speed at which both therapies have gained regulatory approval, mechanistic insights into the drivers of treatment efficacy, disease relapse, and treatment-related toxicities are only now being uncovered. Translating these insights from bench to bedside in a timely and effective manner will be important to achieve greater patient benefit.

Abbreviations

- A2A

Adenosine 2A Receptor

- BCMA

B Cell Maturation Antigen

- CCL

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand

- CCR

C-C Motif Chemokine Receptor

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic Antigen

- CiTE

Checkpoint inhibitory T cell-Engaging

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Associated Protein 4

- CXCR

C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor

- DNR

Double-Negative Receptor

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- EGFRvIII

EGFR Variant 3

- FR-α

Folate Receptor α

- HER2

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2

- HIF

Hypoxia-Inducible Factor

- HSV

Herpes Simplex Virus

- iCAR

inhibitory CAR

- iCasp9

inducible Caspase 9

- ICOS

Inducible T Cell Costimulatory

- PD-1

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1

- PD-L1

Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 1

- PROTAC:

Proteolysis-Targeting Chimaera

- PSCA

Prostate Stem Cell Antigen

- PSMA

Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen

- RANTES

Regulated upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Presumably Secreted

- STAT3

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3

- SWIFF

Switch-Off CAR

- SynNotch

Synthetic Notch

- TET2

Tet Methylcytosine Dioxygenase 2

- TGF-β

Transforming Growth Factor β

- TNF

Tumor Necrosis Factor

- TRUCK

T Cells Redirected for Antigen-Unrestricted Cytokine-Initiated Killing

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. SK is supported by the Marie-Sklodowska-Curie Program Training Network for the Immunotherapy of Cancer funded by the H2020 Program of the European Union (Grant 641549) and the Marie-Sklodowska-Curie Program Training Network for the Optimizing adoptive T cell therapy funded by the H2020 Program of the European Union (Grant 641549 and 955575); the Hector Foundation; the International Doctoral Program i Target: Immunotargeting of Cancer funded by the Elite Network of Bavaria (SK and SE); Melanoma Research Alliance Grants 409510 (to SK); the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (SK); the German Cancer Aid (SK); the Ernst-Jung-Stiftung (SK); LMU Munich’s Institutional Strategy LMUexcellent within the framework of the German Excellence Initiative (SE and SK); the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Project Oncoattract and CONTRACT (SE and SK); the European Research Council Grant 756017, ARMOR-T (to SK), the German Research Foundation (DFG to SK); and the José-Carreras Foundation (to SK). The work was further supported by a German Research Council (DFG) grant provided within the Sonderforschungsbereich SFB 1243 (MaS) and the Wilhelm-Sander Stiftung (MaS). MaS has received industry research support from Amgen, Gilead, Miltenyi, MorphoSys, Roche, and Seattle Genetics.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Melanie Schwerdtfeger, Mohamed-Reda Benmebarek, and Vincenzo Desiderio declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sebastian Kobold has received TCR2 for consultancy honoraria for education and consultancy from Novartis and GSK. SK has received research support from TCR2 Inc., Boston, and Arcus Biosciences, USA. S K and SE have licensed IP to TCR2 Inc. MaS has served as a consultant/advisor to Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Pfizer, Novartis, and Roche. She sits on the advisory boards of Amgen, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Seattle Genetics and serves on the speakers’ bureau at Amgen, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, and Pfizer.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on CART and immunotherapy

Center of Integrated Protein Science Munich (CIPS-M) and Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Medicine IV, Klinikum der Universität München, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany, is a member of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Melanie Schwerdtfeger, Email: melanie.schwerdtfeger@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Mohamed-Reda Benmebarek, Email: mohamedreda.benmebarek@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Stefan Endres, Email: endres@lmu.de.

Marion Subklewe, Email: marion.subklewe@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Vincenzo Desiderio, Email: vincenzo.desiderio@unicampania.it.

Sebastian Kobold, Email: sebastian.kobold@med.uni-muenchen.de.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Lesch S, Benmebarek M-R, Cadilha BL, Stoiber S, Subklewe M, Endres S, Kobold S. Determinants of response and resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;65:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goebeler M-E, Bargou RC. T cell-engaging therapies - BiTEs and beyond. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:418–434. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.•• Strohl WR, Naso M. Bispecific T-cell redirection versus chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells as approaches to kill cancer cells. Antibodies (Basel, Switzerland). 2019. 10.3390/antib8030041 Detailed review comparing CAR T and BiAb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Ellerman D. Bispecific T-cell engagers: towards understanding variables influencing the in vitro potency and tumor selectivity and their modulation to enhance their efficacy and safety. Methods (San Diego Calif) 2019;154:102–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.• Benmebarek M-R, Karches CH, Cadilha BL, Lesch S, Endres S, Kobold S. Killing mechanisms of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. 10.3390/ijms20061283Review on the mechanisms of CAR T cell killing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Labrijn AF, Janmaat ML, Reichert JM, Parren PWHI. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:585–608. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clynes RA, Desjarlais JR. Redirected T cell cytotoxicity in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70:437–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062617-035821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thakur A, Huang M, Lum LG. Bispecific antibody based therapeutics: strengths and challenges. Blood Rev. 2018;32:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klinger M, Brandl C, Zugmaier G, Hijazi Y, Bargou RC, Topp MS, Gökbuget N, Neumann S, Goebeler M, Viardot A, Stelljes M, Brüggemann M, Hoelzer D, Degenhard E, Nagorsen D, Baeuerle PA, Wolf A, Kufer P. Immunopharmacologic response of patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia to continuous infusion of T cell–engaging CD19/CD3-bispecific BiTE antibody blinatumomab. Blood. 2012;119:6226–6233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu M, Wu B, Brandl C, Johnson J, Wolf A, Chow A, Doshi S. Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE®) for CD-19 targeted cancer immunotherapy: clinical pharmacology and its implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55:1271–1288. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arvedson TL, Balazs M, Bogner P, Black K, Graham K, Henn A, et al. Proceedings: AACR Annual Meeting. Washington, DC: American Association for Cancer Research; 2017. Abstract 55: Generation of half-life extended anti-CD33 BiTE® antibody constructs compatible with once-weekly dosing; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruf P, Kluge M, Jäger M, Burges A, Volovat C, Heiss MM, Hess J, Wimberger P, Brandt B, Lindhofer H. Pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and bioactivity of the therapeutic antibody catumaxomab intraperitoneally administered to cancer patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:617–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demarest SJ, Glaser SM. Antibody therapeutics, antibody engineering, and the merits of protein stability. Current opinion in drug discovery & development. 2008;11:675–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rader C. Bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2019;65:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandikian D, Takahashi N, Lo AA, Li J, Eastham-Anderson J, Slaga D, Ho J, Hristopoulos M, Clark R, Totpal K, Lin K, Joseph SB, Dennis MS, Prabhu S, Junttila TT, Boswell CA. Relative target affinities of T-cell-dependent bispecific antibodies determine biodistribution in a solid tumor mouse model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:776–785. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leong SR, Sukumaran S, Hristopoulos M, Totpal K, Stainton S, Lu E, Wong A, Tam L, Newman R, Vuillemenot BR, Ellerman D, Gu C, Mathieu M, Dennis MS, Nguyen A, Zheng B, Zhang C, Lee G, Chu YW, Prell RA, Lin K, Laing ST, Polson AG. An anti-CD3/anti-CLL-1 bispecific antibody for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:609–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-735365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez-Albaitero A, Xu H, Guo H, Wang L, Wu Z, Tran H, Chandarlapaty S, Scaltriti M, Janjigian Y, de Stanchina E, Cheung NKV. Overcoming resistance to HER2-targeted therapy with a novel HER2/CD3 bispecific antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1267891. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1267891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed M, Cheng M, Cheung IY, Cheung NK. Human derived dimerization tag enhances tumor killing potency of a T-cell engaging bispecific antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e989776. doi: 10.4161/2162402X.2014.989776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slaga D, Ellerman D, Lombana TN, Vij R, Li J, Hristopoulos M, Clark R, Johnston J, Shelton A, Mai E, Gadkar K, Lo AA, Koerber JT, Totpal K, Prell R, Lee G, Spiess C, Junttila TT. Avidity-based binding to HER2 results in selective killing of HER2-overexpressing cells by anti-HER2/CD3. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaat5775. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat5775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zafra C, de Balazs M, Fajardo F, Liang L, Zhong W, Henn A, et al. Preclinical characterization of AMG 424, a novel humanized T cell-recruiting bispecific anti-CD3/CD38 antibody. Blood. 2017;130(Supplement 1):500. doi: 10.1182/BLOOD.V130.SUPPL_1.500.500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ClinicalTrials.gov. search terms: condition or disease: “cancer”; intervention: “bispecific AND antibody AND cd3”; status: recruitment: recruiting, enrolling by invitation, active not recruiting. https://clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed 9 Oct 2020.

- 23.• Stoiber S, Cadilha BL, Benmebarek M-R, Lesch S, Endres S, Kobold S. Limitations in the design of chimeric antigen receptors for cancer therapy. Cells. 2019. 10.3390/cells8050472Review on contribution of individual CAR components to CAR T cell functionality. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Liu X, Jiang S, Fang C, Yang S, Olalere D, Pequignot EC, Cogdill AP, Li N, Ramones M, Granda B, Zhou L, Loew A, Young RM, June CH, Zhao Y. Affinity-tuned ErbB2 or EGFR chimeric antigen receptor T cells exhibit an increased therapeutic index against tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3596–3607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. KYMRIAH (tisagenlecleucel). https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/kymriah-tisagenlecleucel. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 26.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. YESCARTA (axicabtagene ciloleucel). https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/yescarta-axicabtagene-ciloleucel. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 27.European Medicines Agency. Kymriah. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/kymriah. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 28.European Medicines Agency. Yescarta. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/yescarta. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 29.European Medicines Agency. Tecartus. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/tecartus. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

- 30.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. TECARTUS (brexucabtagene autoleucel). https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/tecartus-brexucabtagene-autoleucel. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

- 31.Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, Locke FL, Jacobson CA, Hill BT, Timmerman JM, Holmes H, Jaglowski S, Flinn IW, McSweeney PA, Miklos DB, Pagel JM, Kersten MJ, Milpied N, Fung H, Topp MS, Houot R, Beitinjaneh A, Peng W, Zheng L, Rossi JM, Jain RK, Rao AV, Reagan PM. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1331–1342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ClinicalTrials.gov. search terms: condition or disease: “cancer”; intervention: “chimeric AND antigen AND receptor AND t AND cell”; status: recruitment: recruiting, enrolling by invitation, active not recruiting. https://clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed 9 Oct 2020.

- 33.ClinicalTrials.gov. search terms: condition or disease: “cancer”; intervention: “chimeric AND antigen AND receptor AND t AND cell”; status: recruitment: recruiting, enrolling by invitation, active not recruiting; study start: from 01/01/2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed 9 Oct 2020.

- 34.Munshi NC, Anderson LD, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:705–716. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindner SE, Johnson SM, Brown CE, Wang LD. Chimeric antigen receptor signaling: functional consequences and design implications. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz3223. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Offner S, Hofmeister R, Romaniuk A, Kufer P, Baeuerle PA. Induction of regular cytolytic T cell synapses by bispecific single-chain antibody constructs on MHC class I-negative tumor cells. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davenport AJ, Cross RS, Watson KA, Liao Y, Shi W, Prince HM, Beavis PA, Trapani JA, Kershaw MH, Ritchie DS, Darcy PK, Neeson PJ, Jenkins MR. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells form nonclassical and potent immune synapses driving rapid cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E2068–E2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716266115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Künkele A, Johnson AJ, Rolczynski LS, Chang CA, Hoglund V, Kelly-Spratt KS, Jensen MC. Functional tuning of CARs reveals signaling threshold above which CD8+ CTL antitumor potency is attenuated due to cell Fas-FasL-dependent AICD. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:368–379. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Trapani JA, Smyth MJ. Expression in cytotoxic T lymphocytes of a single-chain anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody. Redirected Fas ligand-mediated lysis of colon carcinoma. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1663::AID-IMMU1663>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas C, Krinner E, Brischwein K, Hoffmann P, Lutterbüse R, Schlereth B, Kufer P, Baeuerle PA. Mode of cytotoxic action of T cell-engaging BiTE antibody MT110. Immunobiology. 2009;214:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross SL, Sherman M, McElroy PL, Lofgren JA, Moody G, Baeuerle PA, et al. Bispecific T cell engager (BiTE®) antibody constructs can mediate bystander tumor cell killing. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong LK, Chen Y, Smith CC, Montgomery SA, Vincent BG, Dotti G, Savoldo B. CD30-redirected chimeric antigen receptor T cells target CD30+ and CD30- embryonal carcinoma via antigen-dependent and Fas/FasL interactions. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1274–1287. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brossart P. The role of antigen spreading in the efficacy of immunotherapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4442–4447. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beatty GL, Haas AR, Maus MV, Torigian DA, Soulen MC, Plesa G, Chew A, Zhao Y, Levine BL, Albelda SM, Kalos M, June CH. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:112–120. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim RH, Plesa G, Gladney W, Kulikovskaya I, Levine BL, Lacey SF, June CH, Melenhorst JJ, Beatty GL. Effect of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells on clonal expansion of endogenous non-CAR T cells in patients (pts) with advanced solid cancer. JCO. 2017;35:3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.3011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dao T, Pankov D, Scott A, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, Xu Y, Xiang J, Yan S, de Morais Guerreiro MD, Veomett N, Dubrovsky L, Curcio M, Doubrovina E, Ponomarev V, Liu C, O'Reilly RJ, Scheinberg DA. Therapeutic bispecific T-cell engager antibody targeting the intracellular oncoprotein WT1. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slaney CY, Wang P, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. CARs versus BiTEs: a comparison between T cell-redirection strategies for cancer treatment. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:924–934. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Lin T, Jacoby E, Qin H, Gardner EG, Chien CD, Lee DW, III, Fry TJ. CD4 CAR T cells mediate CD8-like cytotoxic anti-leukemic effects resulting in leukemic clearance and are less susceptible to attenuation by endogenous TCR activation than CD8 CAR T cells. Blood. 2015;126:100. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.100.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rafiq S, Hackett CS, Brentjens RJ. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nature reviews. Clin Oncol. 2020;17:147–167. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi BD, Gedeon PC, Sanchez-Perez L, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Regulatory T cells are redirected to kill glioblastoma by an EGFRvIII-targeted bispecific antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26757. doi: 10.4161/onci.26757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Rivière I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016;3:16015. doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, Braunschweig I, Oluwole OO, Siddiqi T, Lin Y, Timmerman JM, Stiff PJ, Friedberg JW, Flinn IW, Goy A, Hill BT, Smith MR, Deol A, Farooq U, McSweeney P, Munoz J, Avivi I, Castro JE, Westin JR, Chavez JC, Ghobadi A, Komanduri KV, Levy R, Jacobsen ED, Witzig TE, Reagan P, Bot A, Rossi J, Navale L, Jiang Y, Aycock J, Elias M, Chang D, Wiezorek J, Go WY. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2531–2544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, Waller EK, Borchmann P, McGuirk JP, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:45–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, Aplenc R, Porter DL, Rheingold SR, Teachey DT, Chew A, Hauck B, Wright JF, Milone MC, Levine BL, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stadtmauer EA, Fraietta JA, Davis MM, Cohen AD, Weber KL, Lancaster E, Mangan PA, Kulikovskaya I, Gupta M, Chen F, Tian L, Gonzalez VE, Xu J, Jung IY, Melenhorst JJ, Plesa G, Shea J, Matlawski T, Cervini A, Gaymon AL, Desjardins S, Lamontagne A, Salas-Mckee J, Fesnak A, Siegel DL, Levine BL, Jadlowsky JK, Young RM, Chew A, Hwang WT, Hexner EO, Carreno BM, Nobles CL, Bushman FD, Parker KR, Qi Y, Satpathy AT, Chang HY, Zhao Y, Lacey SF, June CH. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science. 2020;367:eaba7365. doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Turtle CJ, Brudno JN, Maus MV, Park JH, Mead E, Pavletic S, Go WY, Eldjerou L, Gardner RA, Frey N, Curran KJ, Peggs K, Pasquini M, DiPersio JF, van den Brink MRM, Komanduri KV, Grupp SA, Neelapu SS. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplan: J American Society Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:625–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goebeler M-E, Knop S, Viardot A, Kufer P, Topp MS, Einsele H, Noppeney R, Hess G, Kallert S, Mackensen A, Rupertus K, Kanz L, Libicher M, Nagorsen D, Zugmaier G, Klinger M, Wolf A, Dorsch B, Quednau BD, Schmidt M, Scheele J, Baeuerle PA, Leo E, Bargou RC. Bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody construct blinatumomab for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results from a phase I study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1104–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viardot A, Goebeler M-E, Hess G, Neumann S, Pfreundschuh M, Adrian N, Zettl F, Libicher M, Sayehli C, Stieglmaier J, Zhang A, Nagorsen D, Bargou RC. Phase 2 study of the bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody blinatumomab in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2016;127:1410–1416. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-651380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Recent advances in CAR T-cell toxicity: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Blood Rev. 2019;34:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Velasquez MP, Bonifant CL, Gottschalk S. Redirecting T cells to hematological malignancies with bispecific antibodies. Blood. 2018;131:30–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-741058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keating AK, Gossai N, Phillips CL, Maloney K, Campbell K, Doan A, Bhojwani D, Burke MJ, Verneris MR. Reducing minimal residual disease with blinatumomab prior to HCT for pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:1926–1929. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018025726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pulsipher MA, Are CAR. T cells better than antibody or HCT therapy in B-ALL? Hematol Am Soc Hemat Educ Program. 2018;2018:16–24. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ran T, Eichmüller SB, Schmidt P, Schlander M. Cost of decentralized CAR T-cell production in an academic nonprofit setting. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:3438–3445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Blinatumomab (akute lymphatische Leukämie: Erwachsene mit minimaler Resterkrankung). 2019. https://www.iqwig.de/download/G19-08_Blinatumomab_ALL-Erwachsene-mit-minimaler-Resterkrankung_Bewertung-35a-Absatz-1-Satz-11-SGB-V_V1-0.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2020.

- 65.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA granted accelerated approval to blinatumomab (Blincyto, Amgen Inc.) for the treatment of adult and pediatric patients with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-granted-accelerated-approval-blinatumomab-blincyto-amgen-inc-treatment-adult-and-pediatric. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 66.European Medicines Agency. Blincyto. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/blincyto. Accessed 4 Oct 2020.

- 67.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Turtle CJ, Hanafi L-A, Berger C, Gooley TA, Cherian S, Hudecek M, Sommermeyer D, Melville K, Pender B, Budiarto TM, Robinson E, Steevens NN, Chaney C, Soma L, Chen X, Yeung C, Wood B, Li D, Cao J, Heimfeld S, Jensen MC, Riddell SR, Maloney DG. CD19 CAR–T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J Clin Investig. 2016;126:2123–2138. doi: 10.1172/JCI85309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park JH, Rivière I, Gonen M, Wang X, Sénéchal B, Curran KJ, Sauter C, Wang Y, Santomasso B, Mead E, Roshal M, Maslak P, Davila M, Brentjens RJ, Sadelain M. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:449–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, Mahnke YD, Melenhorst JJ, Rheingold SR, Shen A, Teachey DT, Levine BL, June CH, Porter DL, Grupp SA. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, Bader P, Verneris MR, Stefanski HE, Myers GD, Qayed M, de Moerloose B, Hiramatsu H, Schlis K, Davis KL, Martin PL, Nemecek ER, Yanik GA, Peters C, Baruchel A, Boissel N, Mechinaud F, Balduzzi A, Krueger J, June CH, Levine BL, Wood P, Taran T, Leung M, Mueller KT, Zhang Y, Sen K, Lebwohl D, Pulsipher MA, Grupp SA. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:439–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grupp SA, Maude SL, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Callahan C, Lacey SF, Levine BL, Melenhorst JJ, Motley L, Rheingold SR, Teachey DT, Wood PA, Porter D, June CH. Durable remissions in children with relapsed/refractory ALL treated with T cells engineered with a CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CTL019) Blood. 2015;126:681. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.681.681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN, Steinberg SM, Stroncek D, Tschernia N, Yuan C, Zhang H, Zhang L, Rosenberg SA, Wayne AS, Mackall CL. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2015;385:517–528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, Somerville RPT, Carpenter RO, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yang JC, Phan GQ, Hughes MS, Sherry RM, Raffeld M, Feldman S, Lu L, Li YF, Ngo LT, Goy A, Feldman T, Spaner DE, Wang ML, Chen CC, Kranick SM, Nath A, Nathan DAN, Morton KE, Toomey MA, Rosenberg SA. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. JCO. 2015;33:540–549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA, Nasta SD, Mato AR, Anak Ö, Brogdon JL, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Bhoj V, Landsburg D, Wasik M, Levine BL, Lacey SF, Melenhorst JJ, Porter DL, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2545–2554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Topp MS, Gökbuget N, Zugmaier G, Klappers P, Stelljes M, Neumann S, Viardot A, Marks R, Diedrich H, Faul C, Reichle A, Horst HA, Brüggemann M, Wessiepe D, Holland C, Alekar S, Mergen N, Einsele H, Hoelzer D, Bargou RC. Phase II trial of the anti-CD19 bispecific T cell-engager blinatumomab shows hematologic and molecular remissions in patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:4134–4140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Topp MS, Gökbuget N, Stein AS, Zugmaier G, O'Brien S, Bargou RC, Dombret H, Fielding AK, Heffner L, Larson RA, Neumann S, Foà R, Litzow M, Ribera JM, Rambaldi A, Schiller G, Brüggemann M, Horst HA, Holland C, Jia C, Maniar T, Huber B, Nagorsen D, Forman SJ, Kantarjian HM. Safety and activity of blinatumomab for adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:57–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, Fielding AK, Schuh AC, Ribera J-M, Wei A, Dombret H, Foà R, Bassan R, Arslan Ö, Sanz MA, Bergeron J, Demirkan F, Lech-Maranda E, Rambaldi A, Thomas X, Horst HA, Brüggemann M, Klapper W, Wood BL, Fleishman A, Nagorsen D, Holland C, Zimmerman Z, Topp MS. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:836–847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martinelli G, Boissel N, Chevallier P, Ottmann O, Gökbuget N, Topp MS, Fielding AK, Rambaldi A, Ritchie EK, Papayannidis C, Sterling LR, Benjamin J, Stein A. Complete hematologic and molecular response in adult patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia following treatment with blinatumomab: results from a phase II, single-arm, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1795–1802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.von Stackelberg A, Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, Handgretinger R, Trippett TM, Rizzari C, Bader P, O’Brien MM, Brethon B, Bhojwani D, Schlegel PG, Borkhardt A, Rheingold SR, Cooper TM, Zwaan CM, Barnette P, Messina C, Michel G, DuBois SG, Hu K, Zhu M, Whitlock JA, Gore L. Phase I/phase II study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JCO. 2016;34:4381–4389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jabbour E, Düll J, Yilmaz M, Khoury JD, Ravandi F, Jain N, Einsele H, Garcia-Manero G, Konopleva M, Short NJ, Thompson PA, Wierda W, Daver N, Cortes J, O'brien S, Kantarjian H, Topp MS. Outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia after blinatumomab failure: no change in the level of CD19 expression. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:371–374. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Darowski D, Kobold S, Jost C, Klein C. Combining the best of two worlds: highly flexible chimeric antigen receptor adaptor molecules (CAR-adaptors) for the recruitment of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. mAbs. 2019;11:621–631. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2019.1596511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bachmann M. The UniCAR system: A modular CAR T cell approach to improve the safety of CAR T cells. Immunol Lett. 2019;211:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cho JH, Collins JJ, Wong WW. Universal chimeric antigen receptors for multiplexed and logical control of T cell responses. Cell. 2018;173:1426–1438.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodgers DT, Mazagova M, Hampton EN, Cao Y, Ramadoss NS, Hardy IR, et al. Switch-mediated activation and retargeting of CAR-T cells for B-cell malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E459-68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524155113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Karches CH, Benmebarek M-R, Schmidbauer ML, Kurzay M, Klaus R, Geiger M, et al. Bispecific antibodies enable synthetic agonistic receptor-transduced T cells for tumor immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5890–5900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Viaud S, Ma JSY, Hardy IR, Hampton EN, Benish B, Sherwood L, et al. Switchable control over in vivo CAR T expansion, B cell depletion, and induction of memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E10898-E10906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810060115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Choi BD, Yu X, Castano AP, Bouffard AA, Schmidts A, Larson RC, et al. CAR-T cells secreting BiTEs circumvent antigen escape without detectable toxicity. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1049–1058. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tokarew N, Ogonek J, Endres S, Bergwelt-Baildon M, von Kobold S. Teaching an old dog new tricks: next-generation CAR T cells. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:26–37. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0325-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Herrmann M, Krupka C, Deiser K, Brauchle B, Marcinek A, Ogrinc Wagner A, et al. Bifunctional PD-1 × αCD3 × αCD33 fusion protein reverses adaptive immune escape in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2018;132:2484–2494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-849802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Serafini M, Manganini M, Borleri G, Bonamino M, Imberti L, Biondi A, Golay J, Rambaldi A, Introna M. Characterization of CD20-transduced T lymphocytes as an alternative suicide gene therapy approach for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:63–76. doi: 10.1089/10430340460732463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Griffioen M, van Egmond EHM, Kester MGD, Willemze R, Falkenburg JHF, Heemskerk MHM. Retroviral transfer of human CD20 as a suicide gene for adoptive T-cell therapy. Haematologica. 2009;94:1316–1320. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang X, Chang W-C, Wong CW, Colcher D, Sherman M, Ostberg JR, et al. A transgene-encoded cell surface polypeptide for selection, in vivo tracking, and ablation of engineered cells. Blood. 2011;118:1255–1263. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Di Stasi A, Tey S-K, Dotti G, Fujita Y, Kennedy-Nasser A, Martinez C, et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1673–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qasim W, Thrasher AJ, Buddle J, Kinnon C, Black ME, Gaspar HB. T cell transduction and suicide with an enhanced mutant thymidine kinase. Gene Ther. 2002;9:824–827. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu C-Y, Roybal KT, Puchner EM, Onuffer J, Lim WA. Remote control of therapeutic T cells through a small molecule-gated chimeric receptor. Science. 2015:350–aab4077. 10.1126/science.aab4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Duong MT, Collinson-Pautz MR. Morschl E, an Lu, Szymanski SP, Zhang M, et al. Two-dimensional regulation of CAR-T cell therapy with orthogonal switches. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;12:124–137. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mestermann K, Giavridis T, Weber J, Rydzek J, Frenz S, Nerreter T, Mades A, Sadelain M, Einsele H, Hudecek M. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib acts as a pharmacologic on/off switch for CAR T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaau5907. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Juillerat A, Tkach D, Busser BW, Temburni S, Valton J, Duclert A, Poirot L, Depil S, Duchateau P. Modulation of chimeric antigen receptor surface expression by a small molecule switch. BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19:44. doi: 10.1186/s12896-019-0537-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee SM, Kang CH, Choi SU, Kim Y, Hwang JY, Jeong HG, Park CH. A chemical switch system to modulate chimeric antigen receptor T cell activity through proteolysis-targeting chimaera technology. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:987–992. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BLINCYTO® (blinatumomab) for injection. 03.2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125557s013lbl.pdf. Accessed 4 Mar 2021.

- 102.Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, Durett A, Liu E, Dakhova O, et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood. 2014;123:3750–3759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-552174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Kosasih PL, Gogishvili T, Maloney DG, Turtle CJ, Riddell SR. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells derived from defined CD8+ and CD4+ subsets confer superior antitumor reactivity in vivo. Leukemia. 2016;30:492–500. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Milone MC, Fish JD, Carpenito C, Carroll RG, Binder GK, Teachey D, Samanta M, Lakhal M, Gloss B, Danet-Desnoyers G, Campana D, Riley JL, Grupp SA, June CH. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1453–1464. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao Z, Condomines M, van der Stegen SJC, Perna F, Kloss CC, Gunset G, Plotkin J, Sadelain M. Structural design of engineered costimulation determines tumor rejection kinetics and persistence of CAR T cells. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:415–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guedan S, Chen X, Madar A, Carpenito C, McGettigan SE, Frigault MJ, et al. ICOS-based chimeric antigen receptors program bipolar TH17/TH1 cells. Blood. 2014;124:1070–1080. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-535245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Song D-G, Ye Q, Poussin M, Harms GM, Figini M, Powell DJ. CD27 costimulation augments the survival and antitumor activity of redirected human T cells in vivo. Blood. 2012;119:696–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Guedan S, Madar A, Casado-Medrano V, Shaw C, Wing A, Liu F, Young RM, June CH, Posey AD., Jr Single residue in CD28-costimulated CAR-T cells limits long-term persistence and antitumor durability. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3087–3097. doi: 10.1172/JCI133215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hirayama AV, Gauthier J, Hay KA, Voutsinas JM, Wu Q, Pender BS, Hawkins RM, Vakil A, Steinmetz RN, Riddell SR, Maloney DG, Turtle CJ. High rate of durable complete remission in follicular lymphoma after CD19 CAR-T cell immunotherapy. Blood. 2019;134:636–640. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kagoya Y, Tanaka S, Guo T, Anczurowski M, Wang C-H, Saso K, Butler MO, Minden MD, Hirano N. A novel chimeric antigen receptor containing a JAK-STAT signaling domain mediates superior antitumor effects. Nat Med. 2018;24:352–359. doi: 10.1038/nm.4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fraietta JA, Nobles CL, Sammons MA, Lundh S, Carty SA, Reich TJ, Cogdill AP, Morrissette JJD, DeNizio JE, Reddy S, Hwang Y, Gohil M, Kulikovskaya I, Nazimuddin F, Gupta M, Chen F, Everett JK, Alexander KA, Lin-Shiao E, Gee MH, Liu X, Young RM, Ambrose D, Wang Y, Xu J, Jordan MS, Marcucci KT, Levine BL, Garcia KC, Zhao Y, Kalos M, Porter DL, Kohli RM, Lacey SF, Berger SL, Bushman FD, June CH, Melenhorst JJ. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature. 2018;558:307–312. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nishio N, Diaconu I, Liu H, Cerullo V, Caruana I, Hoyos V, Bouchier-Hayes L, Savoldo B, Dotti G. Armed oncolytic virus enhances immune functions of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5195–5205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kloss CC, Condomines M, Cartellieri M, Bachmann M, Sadelain M. Combinatorial antigen recognition with balanced signaling promotes selective tumor eradication by engineered T cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wilkie S, van Schalkwyk MCI, Hobbs S, Davies DM, van der Stegen SJC, Pereira ACP, Burbridge SE, Box C, Eccles SA, Maher J. Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1059–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fedorov VD, Themeli M, Sadelain M. PD-1- and CTLA-4-based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:215ra172. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Roybal KT, Rupp LJ, Morsut L, Walker WJ, McNally KA, Park JS, Lim WA. Precision tumor recognition by T cells with combinatorial antigen-sensing circuits. Cell. 2016;164:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]