Abstract

Objectives

Economic constraints are a common explanation of why patients with low socioeconomic status tend to experience less access to medical care. We tested whether the decreased care extends to medical assistance in dying in a healthcare system with no direct economic constraints.

Design

Population-based case–control study of adults who died.

Setting

Ontario, Canada, between 1 June 2016 and 1 June 2019.

Patients

Patients receiving palliative care under universal insurance with no user fees.

Exposure

Patient’s socioeconomic status identified using standardised quintiles.

Main outcome measure

Whether the patient received medical assistance in dying.

Results

A total of 50 096 palliative care patients died, of whom 920 received medical assistance in dying (cases) and 49 176 did not receive medical assistance in dying (controls). Medical assistance in dying was less frequent for patients with low socioeconomic status (166 of 11 008=1.5%) than for patients with high socioeconomic status (227 of 9277=2.4%). This equalled a 39% decreased odds of receiving medical assistance in dying associated with low socioeconomic status (OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.75, p<0.001). The relative decrease was evident across diverse patient groups and after adjusting for age, sex, home location, malignancy diagnosis, healthcare utilisation and overall frailty. The findings also replicated in a subgroup analysis that matched patients on responsible physician, a sensitivity analysis based on a different socioeconomic measure of low-income status and a confirmation study using a randomised survey design.

Conclusions

Patients with low socioeconomic status are less likely to receive medical assistance in dying under universal health insurance. An awareness of this imbalance may help in understanding patient decisions in less extreme clinical settings.

Keywords: rationing, cancer pain, adult palliative care, primary care, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Comprehensive analysis of palliative care patients who died in Canada’s largest region assessing socioeconomic inequities around medical assistance in dying.

Detailed statistics adjusting for observed factors, secondary analyses matching on exact responsible physician and additional confirmation survey testing for unmeasured factors.

Study limitations are inevitable since a randomised trial of medical assistance in dying is not ethical, feasible or realistic.

Further limitations include the fallibility of estimating socioeconomic status that generally yields analyses that underestimate the magnitude of inequities.

Additional limitations involve interpretation of inequities because socioeconomic status is intertwined with patient preferences, communication patterns and implicit bias.

Introduction

Medical assistance in dying is free and legal in Canada.1 An eligible patient must have a grievous and irremediable disease that causes intolerable suffering where death is reasonably foreseeable.2 The common indications are metastatic cancer or a progressive neurological illness.3 Additional requirements include informed consent, second physician verification, attestation from impartial witnesses and an interval for reflection.4 These requirements are designed to avoid thoughtless impulsivity or interpersonal pressures. The protocol involves a series of medications including midazolam, propofol and rocuronium.5 Rates of medical assistance in dying vary substantially by region and currently average over 5000 per year nationally.6 7 Each case hinges on the concept of compassionate care for a suffering patient.

Socioeconomic status influences medical care in many situations. For example, poor patients relative to rich patients tend to be undertreated in a publicly funded colon-cancer screening programme.8 To compensate, recommendations to provide care for poor patients have been fundamental in the practice of medicine since antiquity with persistent advocacy to treat those in most need.9–13 Modern strategies to mitigate inequities tend to focus on situational barriers (eg, access to care) or patient factors (eg, life experience or community norms) and have not been fully successful.14 15 In theory, the causes of socioeconomic inequities can be more complicated because medical treatment also depends on human judgement.

People are prone to pitfalls of reasoning.16 17 Poor patients, for example, may feel less able to advocate for themselves or more reluctant to express their dissatisfaction.18–20 In addition, clinicians may underestimate the distress experienced by poor patients due to faulty intuitions about a life of hardships (termed the thick-skinned fallacy).21–23 We hypothesised such behavioural pitfalls may have important implications for medical care, thereby leading to unequal patterns of care for poor and for rich patients experiencing a similar serious situation.24 25 Here, we explore how this hypothesis might extend to an extreme condition requiring understanding and communication; namely, medical assistance in dying for a palliative care patient.

Methods

Study setting

Most Canadian adults strongly support medical assistance in dying, as indicated by national opinion polls conducted in recent years.26 This support is nearly as strong among poor households (<CAD$40 000 annual income) and rich households (>CAD$100 000 annual income).27 The Supreme Court of Canada ruled on 6 February 2015 that competent Canadian adults have the right to assistance in dying regardless of ability-to-pay and set 17 June 2016 as the implementation date for legalisation.28 Similar to other regions in Canada, medical assistance in dying became a benefit under universal health insurance in Ontario on 6 June 2016.29–31 Ontario is Canada’s largest province with a population of 13 448 494 in 2016 (study baseline).32–34

Patient selection

We identified older adults (age ≥65 years) who died under palliative care using validated linked databases.35–38 We included deaths between 1 June 2016 and 1 June 2019 to reflect all years since legalisation of medical assistance in dying. We identified palliative care by physician fees (Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) code: K023) and required at least two contacts in the last month of life to ensure patients had an irremediable condition, death was reasonably foreseeable, and individuals had access to care.39 Patients who received medical assistance in dying were identified from specifically defined outpatient pharmacy prescriptions (Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) codes: 93 877 101 to 93877106).40 The remaining patients were defined as receiving palliative care without medical assistance in dying. These stringent selection criteria undercount cases compared with federal data sources.41

Socioeconomic status

We identified a patient’s socioeconomic status based on the Statistics Canada official algorithm using the smallest population unit available (size about 500 persons).42–44 These estimates reflected home neighbourhood location, did not rely on self-report and were validated in past research.45–49 Individuals with missing data (<1%) were assigned to the lowest quintile to yield a fully comprehensive analysis and more conservative estimates.50 The purpose of this approach was to avoid limitations in past research such as small sample sizes, subjective survey responses, volunteer participants or uncontrolled analyses of socioeconomic status. The main limitation of our approach was potential random misclassification that would tend to bias comparisons to the null.51

General characteristics

Information on patient age, sex and home location was based on linked demographic databases.52 Additional linked healthcare databases were used to identify time of death (season, weekday, year), home location (urban, rural) and past medical care (clinic contacts, emergency visits, hospital admissions).53 54 The Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) score was used as an overall index of health status and general frailty.55 56 Total medications during the final year of life were obtained using techniques previously validated at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.57 58 The available databases lacked information on self-identified race, ethnic background, religious affiliation, formal education, advance directives and death certificate details.

Clinical characteristics

We further scanned linked outpatient medical care databases in the year prior to death to identify serious medical illnesses with particular attention to malignancy diagnoses (eg, respiratory tract cancer), neurological diagnoses (eg, Parkinson’s disease), and other life-threatening non-malignant diagnoses (eg, congestive heart failure).59 Further comorbid conditions included common chronic diseases (eg, hypertension). Additional psychiatric diagnoses included depression.60 We also gathered data on specific medications (eg, opioids).61 The available databases lacked information on functional status, symptom severity, personal rationales, family relationships, social supports, cultural traditions and informal thoughts.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis examined the distribution of socioeconomic status among patients who received medical assistance in dying compared with controls who did not receive medical assistance in dying using an unpaired χ2 test. Logistic regression was used to further quantify associations using ORs to adjust for potential imbalances in demographic characteristics (age, sex, home location), healthcare utilisation (prior year) and general frailty (Johns Hopkins ACG index). Logistic regression was also used to explore additional factors correlated with receiving medical assistance in dying. Calculations of attributable risk and attributable fractions were conducted using population-based methods.

We conducted two secondary analyses to validate results. First, we used a pair-matched approach (1-to-1 ratio) to identify similar patients who did and who did not receive medical assistance in dying according to age, sex, home location (urban, rural) and responsible physician (exact name).62 The association between socioeconomic status and medical assistance in dying was then tested using methods suitable for matched designs.63 64 Second, a further sensitivity analysis also examined the entire cohort by reclassifying socioeconomic status in a binary manner based on the specific government indicator for a low-income senior (ODB Plan Code R).65 All analyses followed privacy safeguards at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and were conducted using SAS software (V.9.45).

Confirmation survey

We conducted an additional randomised survey to indirectly check the association between socioeconomic status and judgements of patient suffering. In line with behavioural findings concerning estimating perceived discomfort among people,66 the rationale was to explore whether clinicians tend to estimate poor patients as having the same suffering as rich patients in the same situation. The survey contained a single patient scenario formulated in two versions (rich, poor) differing by only one sentence (online supplemental appendix §1). The rich version described the patient as having had a lifetime of luxury. The poor version described the patient as having had a lifetime of hardship. The two versions were otherwise the same, randomly assigned to participants, and designed to elicit a clinician’s judgement of patient suffering due to psychosocial or biomedical adverse events.67

bmjopen-2020-043547supp001.pdf (108KB, pdf)

The survey was prerandomised using a computerised random number generator. The stack of surveys was then allocated one-by-one in a face-down procedure to maintain concealment from the administrator. Survey participants were nurses, doctors or allied healthcare professionals and not necessarily representative of community-based practitioners. Potential respondents were medical staff identified by a tag worn around the neck or on a uniform who visited the hospital’s coffee shop during the day. Individuals were approached by a medical student unaware of clinical backgrounds to avoid targeting or excluding individuals with palliative care training. Surveys required about 1 min to complete and refusals were not tracked. Specialisation was unknown and no individuals were disqualified from participation.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During the 3-year interval, a total of 243 880 deaths were identified, of whom 50 096 received palliative care in the last month of life. Overall, 920 patients received medical assistance in dying and 49 176 controls did not receive medical assistance in dying (table 1). The two groups were similar except those who received medical assistance in dying were slightly more frequent in the later half of the study, relatively more likely to die on a weekday, and somewhat less frail. The typical patient in both groups had a median age of 81 years, was diagnosed with a malignancy, and lived in a city. Three-quarters (72%, n=36 274) were admitted to hospital in the year before dying and two-thirds (65%, n=32 312) had an emergency visit in the year before dying.

Table 1.

Patientcharacteristics

| Medical | Palliative | ||

| Assistance | Control | ||

| In dying | Patients | ||

| (n=920) | (n=49 176) | ||

| Age | ≤75 years | 338 (37) | 15 211 (31) |

| >75 years | 582 (63) | 33 965 (69) | |

| Sex | Female | 484 (53) | 24 826 (50) |

| Male | 436 (47) | 24 350 (50) | |

| Home location* | Urban | 812 (88) | 44 758 (91) |

| Rural | 108 (12) | 4418 (9) | |

| Year of death† | 2016–2017 | 207 (23) | 21 532 (44) |

| 2018–2019 | 713 (77) | 27 644 (56) | |

| Season of year | Spring | 183 (20) | 10 958 (22) |

| Summer | 198 (22) | 12 036 (24) | |

| Autumn | 265 (29) | 12 991 (26) | |

| Winter | 274 (30) | 13 191 (27) | |

| Day of death‡ | Weekday | 778 (85) | 35 849 (73) |

| Weekend | 142 (15) | 13 327 (27) | |

| Malignancy diagnosis§ | Present | 661 (72) | 35 548 (72) |

| Absent | 259 (28) | 13 628 (28) | |

| Total medications in past month¶ | Mean | 9.1±5.3 | 9.5±6.2 |

| Clinic contacts in past year | Mean | 26.01±16.02 | 29.29±18.40 |

| Emergency visits in past year | Mean | 1.33±1.64 | 1.59±2.06 |

| Admissions in past year | Mean | 0.93±1.15 | 1.53±1.53 |

| Overall frailty in past year** | Mean | 8.62±3.75 | 10.56±3.65 |

Data are count (percentage) except where noted as mean±SD.

*Missing values assigned to rural (n=109 of 50 096).

†Denotes first 18 months (2016–2017) and second 18 months (2018–2019), respectively.

‡Saturday and Sunday denote weekend.

§Detailed diagnoses appear in online supplemental appendix §2.

¶Detailed medications appear in online supplemental appendix §3.

**Based on Johns Hopkins University Ambulatory Care Groups.

Diagnoses and treatment

Analysis of individual medical records indicated the two groups of patients had a similar burden of disease in the last year of life (online supplemental appendix §2). The most frequent specific malignancies were cancers of the respiratory tract and digestive tract. Important additional diagnoses included congestive heart failure and pulmonary fibrosis. Many patients also had additional comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes and anxiety. A formal diagnosis of depression was rare in both groups. The most common medication in the last month of life was an opioid analgesic (online supplemental appendix §3). The two groups had similar prescription profiles except patients who chose medical assistance in dying were somewhat more likely to be treated with an opioid or a benzodiazepine.

Socioeconomic status

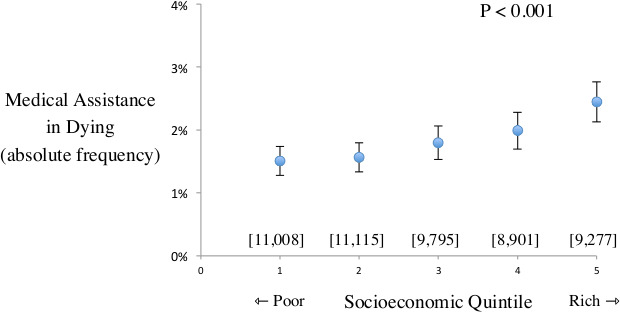

Medical assistance in dying was proportionately less frequent for patients with low socioeconomic status (166 of 11 008) than patients with high socioeconomic status (227 of 9277). Stratified analysis showed intermediate findings for patients with intermediate socioeconomic quintiles (figure 1). Based on the case–control design, this association equalled a 39% reduced frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying associated with low socioeconomic status relative to high socioeconomic status (OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.75, p<0.001). The discrepancy equated to a net difference of 306 fewer cases of medical assistance in dying than would have been expected if all patients had the pattern of those in the highest socioeconomic quintile.

Figure 1.

Frequency of medical assistance in dying plot shows frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying among patients receiving palliative care who have different socioeconomic status. X-axis denotes quintiles of socioeconomic status spanning from lowest to highest. Y-axis denotes frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying. Solid circles indicate estimate and vertical bars indicate 95% CI. Square brackets denote total patients in each analysis. P value indicates trend. Results suggest gradient where patients with lowest socioeconomic status are less likely to receive medical assistance in dying than patients with highest socioeconomic status.

Secondary analyses of subgroups

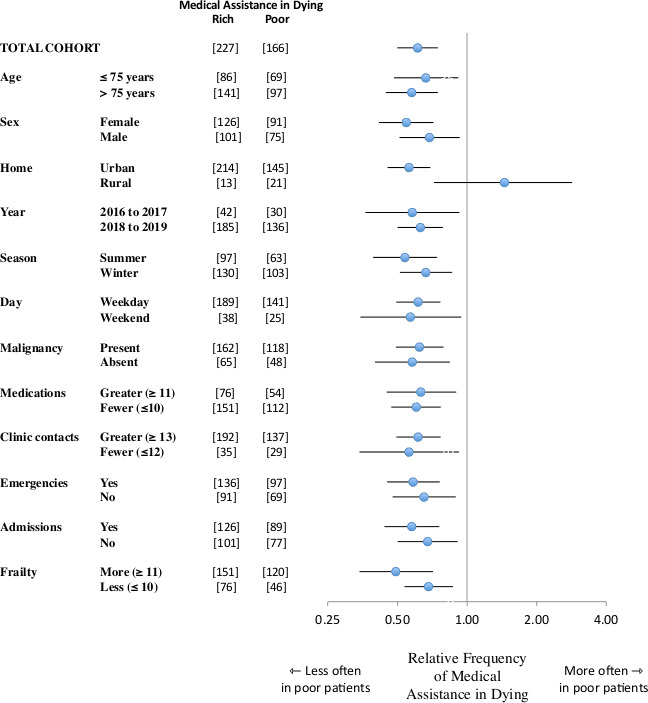

The decreased frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying associated with low socioeconomic status extended to diverse subgroups. The decrease was evident regardless of age and sex (figure 2). The decrease was observed in the first half and the second half of the study (regardless of weekday). Similarly, the decrease was observed for those with and those without a malignancy diagnosis. In addition, the decrease extended to patients regardless of healthcare utilisation and frailty. No subgroup showed contrary findings except for rural patients (not significant). All subgroups with at least 50 cases showed a statistically significant decreased frequency of medical assistance in dying associated with low socioeconomic status.

Figure 2.

Consistent reductions across subgroups forest plot of relative frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying in different subgroups. Each analysis compares patients in lowest socioeconomic quintile to patients in highest socioeconomic quintile. Circles denote estimate and horizontal lines denote 95% CI. Vertical line shows perfect equity. Square brackets show count of patients in each subgroup. Summary analysis for total cohort positioned at top. Findings show generally reduced frequency of medical assistance in dying for patients with low socioeconomic status (exception subgroup of rural home location attributable to chance).

Additional predictors

Several other patient characteristics were associated with a decreased frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying (table 2). Patients older than 75 years were less likely to receive medical assistance in dying than their younger counterparts. Similarly, patients who had relatively more frailty or relatively more hospital admissions were less likely to receive medical assistance in dying. In contrast, sex, home location, clinic contacts and emergency department visits were not significantly associated with medical assistance in dying. Accounting for all characteristics suggested that low socioeconomic status was associated with a 37% decreased frequency of receiving medical assistance in dying (OR=0.63, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.77, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Predictors of medical assistance in dying

| Basic analysis* | Adjusted analysis† | |||

| Relative | Confidence | Relative | Confidence | |

| Variable | Risk | Interval | Risk | Interval |

| Income quintile‡ | 0.61 | 0.50 to 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.51 to 0.77 |

| Age >75 years | 0.77 | 0.67 to 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.62 to 0.82 |

| Male sex | 0.92 | 0.81 to 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.85 to 1.11 |

| Rural home location§ | 1.35 | 1.10 to 1.65 | 1.16 | 0.94 to 1.43 |

| Malignancy diagnosis¶ | 0.98 | 0.85 to 1.13 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 |

| Total medications** | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.02 |

| Clinic contacts in past year** | 0.99 | 0.98 to 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Emergencies in past year** | 0.93 | 0.89 to 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 |

| Admissions in past year** | 0.69 | 0.65 to 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.74 to 0.86 |

| Overall frailty in past year†† | 0.87 | 0.85 to 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.88 to 0.92 |

Contacts, emergencies, admissions, frailty.

*No adjustment for baseline differences.

†Adjusted for age, sex, location, malignancy, medications.

‡Compares lowest to highest quintile.

§Referent is urban location.

¶Denotes one or more diagnoses.

**Covariate coded as a continuous variable.

††Defined by Johns Hopkins frailty index.

Matched analysis

We rechecked results by comparing each patient who received medical assistance in dying with a matched control who did not receive medical assistance in dying and who was treated by the same responsible physician. This yielded 448 matched pairs (n=896 patients). Overall, the case and matched control had the same socioeconomic status in 26% of pairs (118 of 448), the case had a higher socioeconomic status in 42% of pairs (186 of 448) and the case had a lower socioeconomic status in 32% of pairs (144 of 448). This matched analysis yielded results that overlapped the main analysis and showed a 23% decrease of medical assistance in dying associated with lower socioeconomic status (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.96, p=0.021).

Alternate index of socioeconomic status

We also retested results by characterising each individual patient according to whether they were classified by the specific government indicator as a low-income senior. Overall, 8029 patients were identified as low-income seniors and the remaining 42 067 patients were identified as not low-income seniors. Medical assistance in dying was proportionately less frequent for patients who were low-income seniors (65 of 8029) than patients who were not low-income seniors (855 of 42 067). This sensitivity analysis yielded results that overlapped the main analysis and showed a 60% decrease of medical assistance in dying among low-income seniors (OR=0.40, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.51, p<0.001).

Confirmation survey

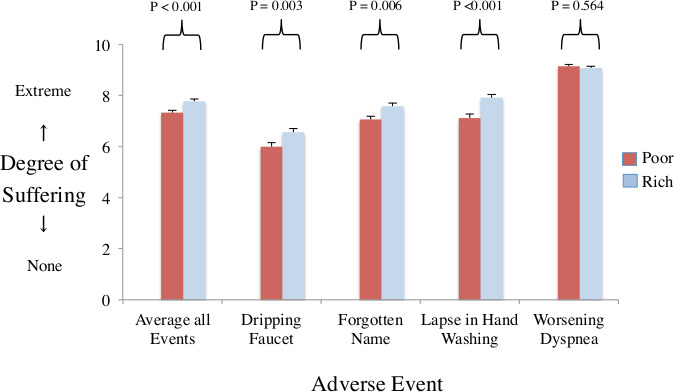

We surveyed clinicians at a coffee shop inside a leading Canadian hospital that provided medical assistance in dying.68 Each participant received one version (rich patient or poor patient) of the survey by randomised assignment (online supplemental appendix §1). The typical participant was a middle-aged woman with professional training and years of medical experience (n=494). We found that overall mean judgements of suffering were higher when assessing a rich patient rather than a poor patient in the survey that otherwise contained identical information about an adverse event (7.8 vs 7.3, p<0.001). This difference in estimated patient suffering extended to each of the three psychosocial adverse events and not the one biomedical adverse event (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perceptions of patient suffering plot shows mean ratings of patient suffering from survey of clinicians (n=494). X-axis denotes average of all adverse events and the four specific components (dripping faucet making noise, forgetting patient name despite being in hospital for days, failures of hand washing when entering room and worsening dyspnoea). Y-axis denotes mean ratings of patient suffering. red bars for survey describing a poor patient. Blue bars for survey describing a rich patient. Vertical beams denote standard errors. P values compare mean ratings of same adverse event. Results show significantly lower mean ratings of suffering in the poor version than rich version (exception of dyspnoea).

Discussion

We studied thousands of deaths in Canada and found that medical assistance in dying was significantly less frequent for palliative care patients who had low rather than high socioeconomic status. The imbalance extended through the range of socioeconomic status and was equally strong during initial and later years of the study. The imbalance is not easily attributed to access to care, ability to pay, medical diagnoses, intensity of medications, choice of physician, responsiveness to treatment, public preferences, thoughtless impulsivity or reciprocal compensation.69–73 The findings also differ from statistics on suicide deaths that are higher among poor rather than rich adults.74 This practice pattern variation is robust and begs for an explanation.

Our research supports earlier patterns observed in other countries around medical assistance in dying. In particular, patients in the USA undergoing legalised assisted dying are more likely to be highly educated and financially secure compared with the population average.75 76 Patients in the Netherlands receiving assisted dying are prone to have comparative social, economic and educational privileges.77 Patients in Switzerland who undergo assisted dying tend to live in affluent neighbourhoods.78 79 Patients in Belgium who receive assisted dying tend to have higher education.80 To our knowledge, these tangential findings apparent in past studies have not been rigorously analysed and have typically been ascribed to economic constraints.81

Our data suggest the unequal distribution of medical assistance in dying may occur beyond aspects of care related to cost.82 One factor could be faulty doctor–patient communication. Poor patients often feel disempowered to advocate for themselves, have lower trust in a healthcare system, and may have less rapport with clinicians who elicit their preferences.83 84 Religion, ethnicity or other confounders could also contribute if rich patients plan more advance directives or suffer more existential distress.85–88 Another possibility is that clinicians dislike controversy and want to avoid appearing callous towards the poor.89 Our study does not determine the appropriateness of medical assistance in dying and, for many, the choice is unthinkable.90–92

The observed unequal treatment might also reflect fallible intuition. The thick-skin bias describes a tendency to perceive individuals of lower income as less distressed by negative events and reflects an implicit belief that repeated hardships lead to increased tolerance.93–95 Similar to other implicit biases, this error might originate from a common assumption; specifically, people sometimes adapt to difficult situations, shift their expectations and increase their tolerance.96–98 The intuition fails, however, when hardships lead to resignation instead of resiliency. In effect, the chronic stress of poverty might not buffer against the added challenges from ill health.99 Such fallible intuitions might add to a paradox of lesser care despite serious clinical needs.100–102

Several limitations of our study merit emphasis for future research. Socioeconomic status measures are imperfect, tend to bias analyses towards the null, and may underestimate disparities in care.103 In addition, disadvantaged groups tend to access palliative care less often than privileged groups, thereby causing our study to underestimate upstream socioeconomic barriers ahead of receiving care.104 105 We also lacked data on race and patients younger than 65 years, thereby justifying further analyses in other groups. Medical assistance in dying, itself, has different meanings depending on available alternatives and a patient’s own beliefs.106 107 The scientific domains of health inequities and of terminal care are, themselves, complex topics often guided by moral principles rather than behavioural economic analysis.108–112

Case–control analyses are rarely accompanied by a confirmation survey for many reasons. Specifically, surveys are often fallible due to faulty sampling, imperfect response rates, social desirability bias, careless mistakes or other artefacts that cause self-report to diverge from real behaviour.113 In addition, most surveys merely offer a superficial impression of lived reality (such as the differences between poverty and wealth). The observed discrepancy in medical assistance in dying might be explained by the observed discrepancy in judged suffering for rich and poor patients; however, other important contributors could remain. The strength of the confirmation survey was to explore intuitive clinical judgement using a randomised experimental approach.

Overall, our data address lingering misconceptions around the medical care implications of the Supreme Court of Canada decision. First, medical assistance in dying has not led to a large drop in palliative care; instead, rates of palliative care increased during the study.114 Second, medical assistance in dying has not become widely popular despite being free and legal; instead, the practice accounts for fewer than 2% of deaths in palliative care patients.115 Third, medical assistance in dying has not been unjustly targeted towards poor patients; instead, wealthy patients are disproportionately involved.116–118 More broadly, the data might inform patient engagement for less extreme decisions where poor patients might be disempowered or clinicians may feel disinclined to push.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Maya Bar-Hillel, Nathan Cheek, Victor Fuchs, Alan Garber, Kevin Imrie, Fizza Manzoor, Dorothy Pringle, Raffi Rush, Michael Schull, Debbie Selby and Jack Williams for helpful suggestions on specific points.

Footnotes

Contributors: The lead author (DR) wrote the first draft. All authors (DR, KN, DT and ES) contributed to study design, manuscript preparation, data analysis, results interpretation, critical revisions and final decision to submit. The lead author (DR) had full access to all the data in the study, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and is accountable for the accuracy of the analysis.

Funding: This project was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (#2014-6-16), a Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences (#950-231316), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#436011), the National Science Foundation (#SES-1426642) and the Sunnybrook Research Institute Summer Scholarship Award Programme (#001).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The deidentified data collected for this study are available in an online supplemental appendix included at the time of original manuscript submission and also are available following publication for researchers whose proposed use of data has been approved by an independent review committee. The Johns Hopkins ACG© System is available through the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins University.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved by the Sunnybrook Research Ethics board and conducted using privacy safeguards at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ID 001). Parts of this material are based on data compiled by CIHI; however, the analyses, conclusions and statements expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of the Drug Information Database.

References

- 1.Nicol J, Tiedemann M. Bill C-14: an act to amend the criminal code and to make related amendments to other acts (medical assistance in dying. Ottawa: Library of Parliament, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orentlicher D, Pope TM, Rich BA. Physician Aid-in-Dying clinical criteria Committee. clinical criteria for physician aid in dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2016;19:259–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiebe E, Shaw J, Green S, et al. Reasons for requesting medical assistance in dying. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:674–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li M, Watt S, Escaf M, et al. Medical Assistance in Dying - Implementing a Hospital-Based Program in Canada. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2082–8. 10.1056/NEJMms1700606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosso AE, Huyer D, Walker A. Analysis of the medical assistance in dying cases in Ontario: understanding the patient demographics of case uptake in Ontario since the Royal Assent and amendments of bill C-14 in Canada. Acad Forensic Pathol 2017;7:263–87. 10.23907/2017.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Canada . Second interim report on medical assistance in dying in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Canada . Third interim report on medical assistance in dying in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchman S, Rozmovits L, Glazier RH. Equity and practice issues in colorectal cancer screening: mixed-methods study. Can Fam Physician 2016;62:e186–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonsen AR. A short history of medical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart JT. The inverse care law. The Lancet 1971;297:405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson DL, Stewart MJ, Hayward K, et al. Low-Income Canadians' experiences with health-related services: implications for health care reform. Health Policy 2006;76:106–21. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casalino LP. Professionalism and caring for Medicaid patients--the 5% commitment? N Engl J Med 2013;369:1775–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1310974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13., Bump J, Cashin C, et al. , Participants at the Bellagio Workshop on Implementing Pro-Poor Universal Health Coverage . Implementing pro-poor universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e14–16. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaacs SL, Schroeder SA. Class - the ignored determinant of the nation's health. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1137–42. 10.1056/NEJMsb040329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bor J, Cohen GH, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. The Lancet 2017;389:1475–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redelmeier DA, Rozin P, Kahneman D, et al. Cognitive and emotional perspectives. JAMA 1993;270:72–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafir E. The behavioral foundations of public policy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, et al. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 2013;341:976–80. 10.1126/science.1238041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tesarz J, Eich W, Treede R-D, et al. Altered pressure pain thresholds and increased wind-up in adult patients with chronic back pain with a history of childhood maltreatment: a quantitative sensory testing study. Pain 2016;157:1799–809. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber MM, Frankfurt SB, Contractor AA, et al. Influence of multiple traumatic event types on mental health outcomes: does count matter? J Psychopath Behav Assess 2018;40:645–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stebbins J. The law of diminishing returns. Science 1944;99:267–71. 10.1126/science.99.2571.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S. Assumptions about life hardship and pain perception. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2016;19:493–508. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheek NN, Shafir E. The thick skin bias in judgments about people in poverty. Behavioural Public Policy 2020;4:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979;47:263–92. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullainathan S, Shafir E. Scarcity: the new science of having less and how it defines our lives. New York: Picador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Attaran A. Unanimity on death with dignity--legalizing physician-assisted dying in Canada. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2080–2. 10.1056/NEJMp1502442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid I. Eight in ten Canadians support advance consent to physician-assisted dying. Toronto: Ipsos Reid, 2016. https://www.ipsos.com/en-ca/news-polls/eight-ten-80-canadians-support-advance-consent-physician-assisted-dying [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chochinov HM, Frazee C. Finding a balance: Canada’s law on medical assistance in dying. The Lancet 2016;388:543–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health and Long Term Care Strategic Policy Branch . Medical assistance in dying. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2016. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ohip/bulletins/4000/bul4670.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ministry of Health and Long Term Care & Ontario Medical Association . OHIP payment for medical assistance in dying. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2018. https://www.oma.org/wp-content/uploads/MAID_Billing-Guide-final-18Oct2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ontario Ministry of Health Ministry of Long Term Care . Medical assistance in dying. Toronto: Government of Ontario, 2018. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/maid/. (Accessed on 2021 Jan 10). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Statistics Canada . Canada at a Glance 2010 - Population [Internet]., 2010. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/12-581-x/2010000/pop-eng.htm [Accessed cited 2019 Mar 17].

- 33.About Ontario [Internet]. Government of Ontario, 2019. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/page/about-ontario [Accessed cited 2019 Mar 17].

- 34.Government of Canada . Medical assistance in dying. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying.html. (Accessed on 2021 Jan 20). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences . Data dictionary: library. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. https://datadictionary.ices.on.ca/Applications/DataDictionary/Default.aspx. (Accessed 2019 Feb 11). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iron K, Manuel DG. Quality assessment of administrative data (QuAAD): an opportunity for enhancing Ontario’s health data. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iron K, Zagorski B, Sykora K. Living and dying in Ontario: an opportunity for improved health information—ICES investigative report. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences . Working with ICES data. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). www.ices.on.ca/Data-and-Privacy/ICES-data/Working-with-ICES-Data. (Accessed 2019 Feb 11). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . Schedule of benefits. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . Ontario drug benefit Formulary/Comparative drug index. Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Canada . First annual report on medical assistance in dying in Canada 2019. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/medical-assistance-dying-annual-report-2019/maid-annual-report-eng.pdf. (Accessed on 2021 Jan 20). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Love R, Wolfson MC, Statistics Canada- Consumer Income and Expenditure Division . Income inequality: statistical methodology and Canadian illustrations. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin P, et al. Effects of socioeconomic status on access to invasive cardiac procedures and on mortality after acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 1999;341:1359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finkelstein MM. Ecologic proxies for household income: how well do they work for the analysis of health and health care utilization? Can J Public Health 2004;95:90–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health 1992;82:703–10. 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mustard CA, Derksen S, Berthelot JM, et al. Assessing ecologic proxies for household income: a comparison of household and neighbourhood level income measures in the study of population health status. Health&Place 1999;5:157–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glazier RH, Creatore MI, Agha MM, et al. Socioeconomic misclassification in Ontario’s health care registry. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2003;94:140–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Statistics Canada (2006). income and earnings reference guide, 2006 census. Catalogue No. 97–563-GWE2006003. Available: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/ref/rp-guides/income-revenu-eng.cfm

- 49.Statistics Canada. 2006 census dictionary. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca

- 50.Hayden GF, Kramer MS, Horwitz RI. The case-control study: a practical review for the clinician. JAMA 1982;247:326–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pampalon R, Hamel D, Gamache P. A comparison of individual and area-based socio-economic data for monitoring social inequalities in health. Health Reports 2009;20:85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Government of Ontario . Registered Persons Database [Internet. Ontario: Government of Ontario, 2017. https://www.ontario.ca/data/registered-persons-database-rpdb. (cited 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, et al. Patterns of health care in Ontario - The ICES practice atlas. Ontario: ICES, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jaakkimainen L, Upshur R, Klein-Geltink JE, et al. Primary care in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sibley LM, Moineddin R, Agha MM, et al. Risk adjustment using administrative data-based and survey-derived methods for explaining physician utilization. Med Care 2010;48:175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin PC, van Walraven C, Wodchis WP, et al. Using the Johns Hopkins aggregated diagnosis groups (ADGS) to predict mortality in a general adult population cohort in Ontario, Canada. Med Care 2011;49:932–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guilcher SJT, Bronskill SE, Guan J, et al. Who are the high-cost users? A method for person-centred Attribution of health care spending. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wodchis WP, Austin PC, Henry DA. A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care. CMAJ 2016;188:182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, et al. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Medicine 2007;1:e18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gandhi S, Chiu M, Lam K, et al. Mental health service use among children and youth in Ontario: population-based trends over time. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2016;61:119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levy AR, O'Brien BJ, Sellors C, et al. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario drug benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol 2003;10:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Redelmeier DA, Tibshirani RJ. Methods for analyzing matched designs with double controls: excess risk is easily estimated and misinterpreted when evaluating traffic deaths. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;98:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bresolow NE, Day NE. Analysis of case-control studies. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wacholder S, Weinberg CR. Paired versus two-sample design for a clinical trial of treatments with dichotomous outcome: power considerations. Biometrics 1982;38:801–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vozoris NT, Yao Z, Li P, et al. Prescription synthetic oral cannabinoid use among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Drugs & Aging 2019;36:1035–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheek NN, Shafir E. The thick skin bias in Judgments about people in poverty. Behav Public Policy 2020;8:1–26. 10.1017/bpp.2020.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krueger AB, Stone AA. Psychology and economics. progress in measuring subjective well-being. Science 2014;346:42–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selby D, Bean S, Isenberg-Grzeda E, et al. Medical assistance in dying (MAID): a descriptive study from a Canadian tertiary care hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37:58-64. 10.1177/1049909119859844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayers I. Fair driving: gender and race discrimination in retail CAR negotiations. Harvard Law Review 1991;104:817–72. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Redelmeier DA, Cialdini RB. Problems for clinical judgement: 5. principles of influence in medical practice. CMAJ 2002;166:1680–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Redelmeier DA, Dickinson VM. Determining whether a patient is feeling better: pitfalls from the science of human perception. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:900–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Redelmeier DA, Dickinson VM. Judging whether a patient is actually improving: more pitfalls from the science of human perception. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1195–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.TH H, Barbera L, Saskin R, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011;29:1587–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Long A. Cause-Specific mortality by income adequacy in Canada: a 16-year follow-up study. Health Rep 2013;24:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prokopetz JJ, Lehmann LS. Redefining physicians' role in assisted dying. N Engl J Med 2012;367:97–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boudreau JD, Somerville MA, Biller-Andorno N, et al. Physician-Assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1450–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Battin MP, van der Heide A, Ganzini L, et al. Legal physician-assisted dying in Oregon and the Netherlands: evidence concerning the impact on patients in "vulnerable" groups. J Med Ethics 2007;33:591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steck N, Junker C, Zwahlen M, Swiss National Cohort . Increase in assisted suicide in Switzerland: did the socioeconomic predictors change? results from the Swiss national cohort. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steck N, Junker C, et al. , Swiss National Cohort . Suicide assisted by right-to-die associations: a population based cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology 2014;43:614–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, et al. Comparison of the expression and granting of requests for euthanasia in Belgium in 2007 vs 2013. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:1703–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sulmasy LS, Mueller PS. Ethics and the Legalization of physician-assisted suicide: an American College of physicians position paper. Annals of Internal Medicine 2017;167:576–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Redelmeier DA, Detsky AS. Economic theory and medical assistance in dying. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verlinde E, De Laender N, De Maesschalck S, et al. The social gradient in doctor-patient communication. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:12–14. 10.1186/1475-9276-11-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wright AC, Shaw JC. The spectrum of end of life care: an argument for access to medical assistance in dying for vulnerable populations. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 2019;22:211–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Voeuk A, Nekolaichuk C, Fainsinger R, et al. Continuous palliative sedation for existential distress? A survey of Canadian palliative care physicians' views. J Palliat Care 2017;32:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lo B. Beyond Legalization — dilemmas physicians confront regarding aid in dying. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2060–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, et al. Completion of advance directives among US consumers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2014;46:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McDonald JC, Du Manoir JM, Kevork N, et al. Advance directives in patients with advanced cancer receiving active treatment: attitudes, prevalence, and barriers. Supportive Care in Cancer 2017;25:523–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Selby D, Bean S. Oncologists communicating with patients about assisted dying. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2019;13:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boudreau JD, Somerville MA, Biller-Andorno N. Physician-Assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1450–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Colbert JA, Schulte J, Adler JN. Physician-Assisted suicide—polling results. N Engl J Med 2013;369:e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miller FG, Appelbaum PS. Physician-Assisted Death for Psychiatric Patients - Misguided Public Policy. N Engl J Med 2018;378:883–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoffman KH, Trawalter S. Assumptions about life hardship and pain perception. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2016;19:493–508. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, et al. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016;113:4296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheek NN, Shafir E. The thick skin heuristic in judgments of distress about people in poverty. Behavioural Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 1974;185:1124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH. Experimental tests of the Endowment effect and the Coase theorem. Journal of Political Economy 1990;98:1325–48. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kahneman D, Knetsch JL, Thaler RH. Anomalies: the Endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives 1991;5:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, et al. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 2013;341:976–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wamala S, Merlo J, Boström G, et al. Perceived discrimination, socioeconomic disadvantage and refraining from seeking medical treatment in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:409–15. 10.1136/jech.2006.049999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hausmann LRM, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, et al. Impact of perceived discrimination in healthcare on patient-provider communication. Med Care 2011;49:626–33. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d93c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hoffman KM, Trawalter S. Assumptions about life hardship and pain perception. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2016;19:493–508. 10.1177/1368430215625781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Walker AE, Becker NG. Health inequalities across socio-economic groups: comparing geographic-area-based and individual-based indicators. Public Health 2005;119:1097–104. 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Manuel D, et al. Association between immigrant status and end-of-life care in Ontario, Canada. JAMA 2017;318:1479–88. 10.1001/jama.2017.14418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rubens M, Ramamoorthy V, Saxena A, et al. Palliative care consultation trends among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer in the United States, 2005 to 2014. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:294–301. 10.1177/1049909118809975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, et al. ‘Unbearable suffering': a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics 2011;37:727–34. 10.1136/jme.2011.045492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. Patient-Reported barriers to high-quality, end-of-life care: a multiethnic, multilingual, mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med 2016;19:373–9. 10.1089/jpm.2015.0403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shafir E. The behavioral foundations of policy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cameron BL, Carmargo Plazas MDP, Salas AS, et al. Understanding inequalities in access to health care services for Aboriginal people: a call for nursing action. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2014;37:E1–16. 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dickman SL, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. The Lancet 2017;389:1431–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet 2017;389:1453–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bor J, Cohen GH, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. The Lancet 2017;389:1475–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30571-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Converse JM. Survey research in the United States: roots and emergence 1890-1960. Routledge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang YT, Curlin FA. Why physicians should oppose assisted suicide. JAMA 2016;315:247–8. 10.1001/jama.2015.16194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lerner BH, Caplan AL. Euthanasia in Belgium and the Netherlands: on a slippery slope? JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:1640–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Noble B. Republished: Legalising assisted dying puts vulnerable patients at risk and doctors must speak up. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:298–9. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hadro M. How assisted suicide discriminates against the poor and disabled. Catholic news agency, 2017. Available: https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/how-assisted-suicide-discriminates-against-the-poor-and-disabled-57444

- 118.Vivas L, Bastien P. Expanding maid criteria could irreversibly harm the most vulnerable. health debate, 2020. Available: https://healthydebate.ca/opinions/maid-harm-vulnerable-response

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043547supp001.pdf (108KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The deidentified data collected for this study are available in an online supplemental appendix included at the time of original manuscript submission and also are available following publication for researchers whose proposed use of data has been approved by an independent review committee. The Johns Hopkins ACG© System is available through the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins University.