Abstract

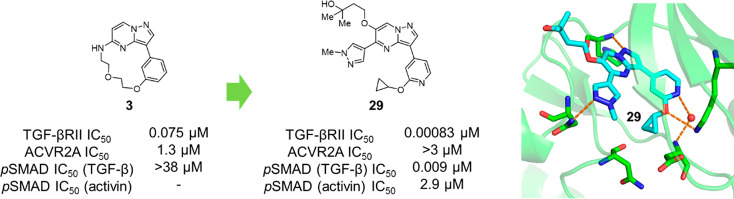

Historically, modulation of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling has been deemed a rational strategy to treat many disorders, though few successful examples have been reported to date. This difficulty could be partially attributed to the challenges of achieving good specificity over many closely related enzymes that are implicated in distinct phenotypes in organ development and in tissue homeostasis. Recently, fresolimumab and disitertide, two peptidic TGF-β blockers, demonstrated significant therapeutic effects toward human skin fibrosis. Therefore, the selective blockage of TGF-β signaling assures a viable treatment option for fibrotic skin disorders such as systemic sclerosis (SSc). In this report, we disclose selective TGF-β type II receptor (TGF-βRII) inhibitors that exhibited high functional selectivity in cell-based assays. The representative compound 29 attenuated collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) expression in a mouse fibrosis model, which suggests that selective inhibition of TGF-βRII-dependent signaling could be a new treatment for fibrotic disorders.

Keywords: Selective kinase inhibitor, fibrosis, TGF-βRII, TGF-β signaling pathway, halogen dance rearrangement

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a pleiotropic cytokine family that comprises highly homologous isoforms TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. Since these cytokines play crucial roles in a variety of biological processes, aberrant regulation of this TGF-β signaling cascade often results in various pathologies, including cancer and fibrosis.1,2 Recently, two peptidic TGF-β inhibitors, fresolimumab and disitertide, were reported to exhibit good preventive effects against human skin fibrosis,3,4 suggesting that blocking a common TGF-β signaling pathway could be a viable option for treating fibrotic skin disorders such as systemic sclerosis (SSc).5 TGF-β signaling is initiated when the cytokine engages with TGF-β type II receptor (TGF-βRII), a transmembrane serine/threonine receptor kinase, which successively results in its complexation with another serine/threonine receptor kinase, TGF-β type I receptor (TGF-βRI, also known as ALK5). Upon formation of this complex, comprising a set of respective homodimers, two intracellular proteins, SMAD2 and SMAD3, are phosphorylated, leading to the formation of a heterotrimer with SMAD4.6 The resultant ternary complex then translocates into the nucleus, and transcription of several key fibrotic genes, such as those encoding collagens and fibronectin, are subsequently triggered.7,8 Because of the complexity of TGF-β signaling, the precise mechanisms and functions of the respective receptors have been poorly understood. Previously, TGF-βRI inhibitors, including SM16 and GW788388, were proven to show antifibrotic effects,9−15 but cardiac side effects were also observed,16−19 pointing to its potential risk as a target for an antifibrosis agent. In contrast, there have been several selective TGF-βRII ligands. However, little has been clarified about the pharmacological role of TGF-βRII-dependent signals to date.

Herein we report the discovery of novel TGF-βRII inhibitors with superb selectivity over closely related isozymes. One of the best compounds achieved good functional selectivity in cell-based assays and was subjected to in vivo experiments to understand TGF-βRII-dependent pharmacology.

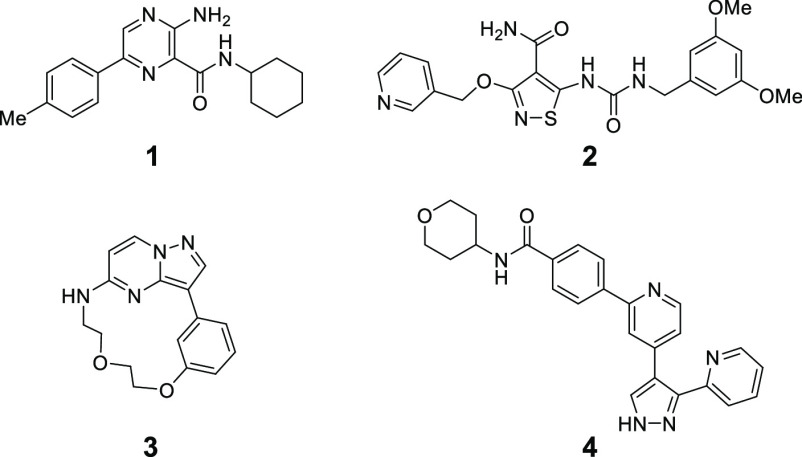

Historically, there have been several TGF-βRII inhibitors that appeared in preceding reports,20−22 and representative compounds disclosed in those publications were initially characterized (Table 1). Among the distinct class of TGF-βRII inhibitors, compounds 2(20) and 3(21) showed decent selectivity over activin receptor type 2A (ACVR2A), which is also a well-recognized receptor of the TGF-β superfamily with serine/threonine receptor kinase activity,23 while compound 1(22) rarely revealed TGF-βRII selectivity. A significant reduction of cell potency was also notable for both 2 and 3, but most disappointingly, 2 lost functional selectivity in view of SMAD3 phosphorylation in the cell-based assays (Table 1). Activin-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation is known to occur through its binding to ACVR2A and subsequent phosphorylation of activin receptor-like kinase 4 (ALK4)/activin receptor-like kinase 7 (ALK7). Therefore, when the kinase inhibitory profiles of compound 2 with respect to TGF-βRII and ACVR2A were taken into consideration, the outcome was unexpected. Contrastingly, the nonselective nature of compound 4 (GW788388) in the cell assays was quite understandable since this compound was known to inhibit ALK5, TGF-βRII, and ACVR2 (IC50 values against TGF-βRII and ACVR2 were not specified in the literature). These data led us to examine their Km values for ATP, and it turned out that ACVR2A has roughly 30-times lower affinity toward the natural substrate relative to TGF-βRII (Km,ATP = 9.54 μM for ACVR2A vs 0.33 μM for TGF-βRII).24 Although we cannot fully exclude the role of other factors in SMAD3 phosphorylation, we proposed that ACVR2A inhibition had a greater impact on the suppressive effect on SMAD3 phosphorylation and that the several-hundred-fold TGF-βRII selectivity over this isozyme was not sufficient to realize the desired functional selectivity. To this end, we conducted SAR investigations to identify a TGF-βRII inhibitor of great specificity, which ultimately resulted in uncovering a new role of TGF-βRII selective signaling.

Table 1. Preceding TGF-βRII Inhibitors.

| enzyme

IC50 (μM)a,b |

cell

IC50 (μM)c,d |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | TGF-βRII | ACVR2A | ALK5 | TGF-β | activin |

| 1 | 0.49 | 0.18 | NTe | >38 | >38 |

| 2 | 0.11 | 20 | NT | 10 | 3.3 |

| 3 | 0.075 | 1.3 | 4.4 | >38 | NT |

| 4 | NT | NT | 0.018f | 0.28 | 0.52 |

Kinase inhibitory activity against each receptor kinase.

IC50 values are mean values determined from three replicates.

Suppressive effect on SMAD3 phosphorylation after TGF-β or activin stimulation in Expi293F cells.

IC50 values are mean values determined from four replicates.

NT = not tested.

Reported value in the literature.14

Given that 3 displayed the highest ligand efficiency (LE)25 value among the historical TGF-βRII inhibitors 1–3 (0.37, 0.30, and 0.44 for compounds 1, 2, and 3, respectively), we chose this candidate as a lead compound and undertook synthetic explorations (Table 2). First, we prepared compound 5, a surrogate molecule of 3, and then examined the SAR of its two aromatic portions. Simple installation of a nitrogen atom at the 4-position of the benzene ring (X = N) boosted the TGF-βRII inhibitory activity over 200-fold, and more gratifyingly, this compound 6 achieved good selectivity over two closely related kinases, ACVR2A and ALK5. In accordance with such enzyme selectivity, we observed moderate functional selectivity in the cell-based assay, and 6 suppressed TGF-β-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation roughly 3-fold stronger than the phosphorylation triggered by activin initiation. Since this platform suggested further gains in TGF-βRII selectivity, we continued successive efforts, leaving intact the critical methoxypyridine moiety. Examination of the effects of substitution at the 6-position of the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine ring revealed a rather flat SAR with virtually no deviation of TGF-βRII inhibitory activity, as shown in Table 2 (7–11). With regard to TGF-βRII selectivity, this series of compounds possessed a general tendency to inhibit ACVR2A at levels stronger than ALK5. Therefore, TGF-βRII selectivity would be assured as far as inhibitory activity against ACVR2A is concerned. On the basis of both its cell-based potency and chemical stability, 11 was chosen for further investigation, and the 5-position on the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine ring was investigated (Table 3). Simple deletion of the methylamino group (12) led to a >10-fold reduction of TGF-βRII inhibitory activity, and introduction of a dimethylamino (13), methyl (14), or ethyl substituent (15) could not fully revive the TGF-βRII potency. Meanwhile, a branched alkyl substituent exemplified by an isopropyl group (16) conferred potency comparable to that of 11, although subsequent incorporation of a hydroxyl group into 16 to produce the corresponding tertiary alcohol 17 led to a reduction of the potency. Driven by the result with 16, compounds possessing a cyclic motif at the 5-position were next synthesized. The enzyme potencies of a compound having a cyclopentane ring (18) and one with a tetrahydrofuran ring (19) were similar to each other, having IC50 values comparable to that of 16. Simultaneously, their functional potencies in the cell assay diverged, with 19 being 5 times more potent than 18 in the TGF-β-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation assay. Further enlargement at the terminus of the tetrahydrofuran ring (20) retained the enzyme potency, even though its enantiomer 21 showed substantially lower potency. This outcome suggested that this region was still encapsulated within the pocket with strict discrimination of the chirality.

Table 2. Initial SAR Exploration.

| enzyme

IC50 (μM)a |

cell

IC50 (μM)b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | X | TGF-βRII | ACVR2A | ALK5 | TGF-β | activin |

| 5 | H | CH | 1.0 | >20 | NTc | >38 | NT |

| 6 | H | N | 0.0039 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 14 |

| 7 | Me | N | 0.0029 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 5.4 | 22 |

| 8 | vinyl | N | <0.003 (82%) | 0.19 | 1.4 | 0.38 | 4.1 |

| 9 | Et | N | 0.0015 | 0.70 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 11 |

| 10 | c-Pr | N | 0.0037 | 0.63 | 8.9 | 6.9 | 12 |

| 11 | MeO | N | 0.0010 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 4.8 |

IC50 values are mean values determined from three replicates.

Values of IC50 are mean values determined from four replicates.

NT = not tested.

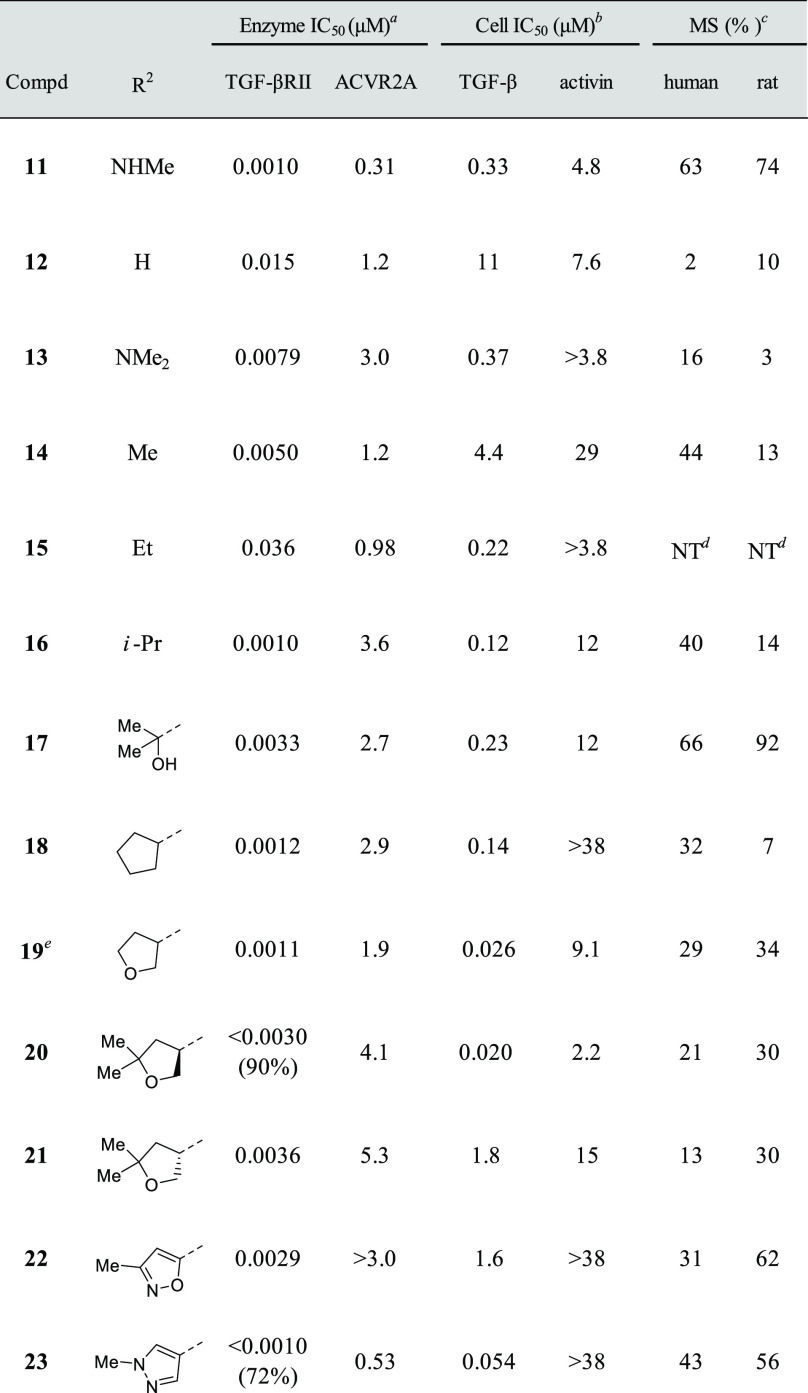

Table 3. SAR of the 5-Position on the Pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine Ring.

IC50 values are mean values determined from three replicates.

IC50 values are mean values determined from four replicates.

Metabolic stability in liver microsomes after incubation for 60 min.

Not tested because of insolubility problems.

Racemate.

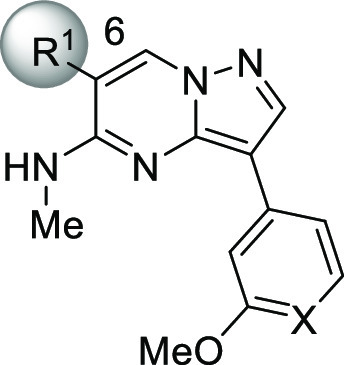

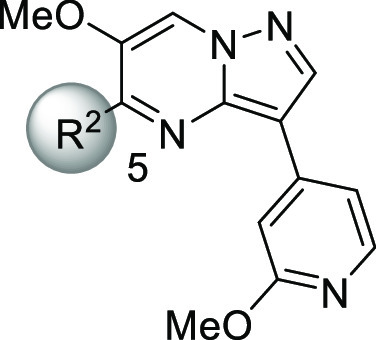

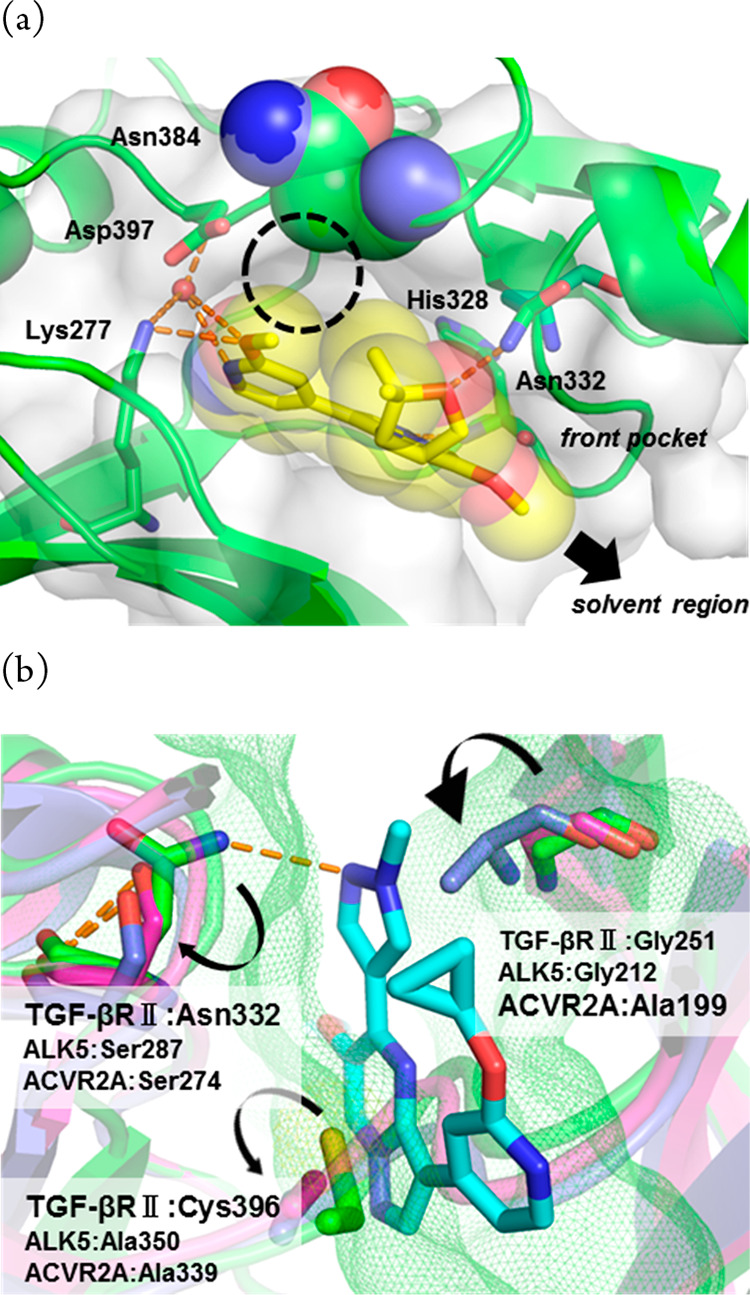

Analogues of 20 possessing an aromatic ring at the R2 position were also synthesized (22 and 23), and 23 reached a subnanomolar value of IC50 in the enzyme assay. Rather disappointingly, the strong TGF-βRII inhibitory activity of 23 did not directly translate into cell-based potency. However, the >700-fold increase of functional selectivity against activin-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation was quite noteworthy, so the final optimization was carried out with this compound. Among the compounds listed in Table 3, 20 gave a clear cocrystal with the kinase domain of TGF-βRII, and the structural information we obtained facilitated final optimization of this series of compounds. The data pointed out that the nitrogen atom at the 1-position of the pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine ring and the oxygen atom of the tetrahydrofuran made firm hydrogen bonds with His328 and Asn332, respectively, while the methoxypyridine moiety and Lys277 and Asp397 formed a hydrogen-bonding network with the aid of a water molecule. More importantly, there seemed to be sufficient space in the front pocket region along with an additional small cavity near the pyridine ring, so we undertook further investigation of these two sites (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Cocrystal structure of 20 in TGF-βRII (PDB code 7DV6). Hydrogen bonds are depicted as dashed lines (orange), and the water molecule is shown as spheres (red). The CPK representation of 20 is shown to clarify unfulfilled spaces in the binding pocket. The dashed circle indicates a small cavity near the pyridine ring. (b) Docking model of 29 (cyan) in TGF-βRII (green; PDB code 7DV6), ALK5 (magenta; PDB code 1VJY), and ACVR2A (slate blue; PDB code 3Q4T). Protein surfaces of TGF-βRII are depicted as meshed lines. Key amino acids for realizing selectivity are displayed as sticks (green for TGF-βRII, magenta for ALK5, and slate blue for ACVR2A, respectively).

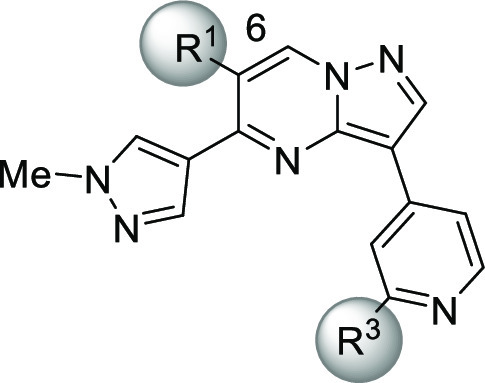

Driven by such information, we first examined small alkoxy groups as the R3 substituent (Table 4). Unfortunately, no additional gain in the enzyme potency was observed with compounds 24–27, although the cell-based potency was improved, and 26 scored the best cell potency among those analogues of 23. On the other hand, the selectivity over activin-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation was diminished, which led us to focus on another aspect of the structure. Since the 6-position of the core ring was present in the front pocket region projecting toward the outside of the pocket, several glycol motifs, one of which anchored to the core part, were examined. To mitigate the potential risk of oxidation and/or hazardous conjugate formation, a dimethyl substituent was simultaneously incorporated within the glycol motifs.

Table 4. Final Optimization of 23.

| enzyme

IC50 (μM)a |

cell

IC50 (μM)b |

MS (%)c |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R3 | TGF-βRII | ACVR2A | TGF-β | activin | human | rat |

| 23 | MeO | MeO | 0.00017 | 0.53 | 0.054 | >38 | 43 | 56 |

| 24 | MeO | i-PrO | 0.00058 | 2.3 | 0.011 | 0.43 | 32 | 50 |

| 25 | MeO | t-BuO | 0.0070 | 0.80 | 0.024 | 0.92 | 35 | 61 |

| 26 | MeO | c-PrO | 0.0016 | 0.86 | 0.005 | 0.39 | 47 | 32 |

| 27 | MeO | c-BuO | 0.00061 | 2.4 | 0.014 | >1.3 | NTd | NTd |

| 28 | HOC(Me)2CH2O | c-PrO | 0.00031 | 2.3 | 0.014 | 0.87 | 53 | 81 |

| 29 | HOC(Me)2(CH2)2O | c-PrO | 0.00083 | >3.0 | 0.009 | 2.9 | 74 | 84 |

| 30 | HOC(Me)2(CH2)3O | c-PrO | 0.0020 | 2.9 | 0.035 | 0.63 | 54 | 64 |

IC50 values are mean values determined from three replicates.

IC50 values are mean values determined from four replicates.

Metabolic stability in liver microsomes after incubation for 60 min.

Not tested because of insolubility problems.

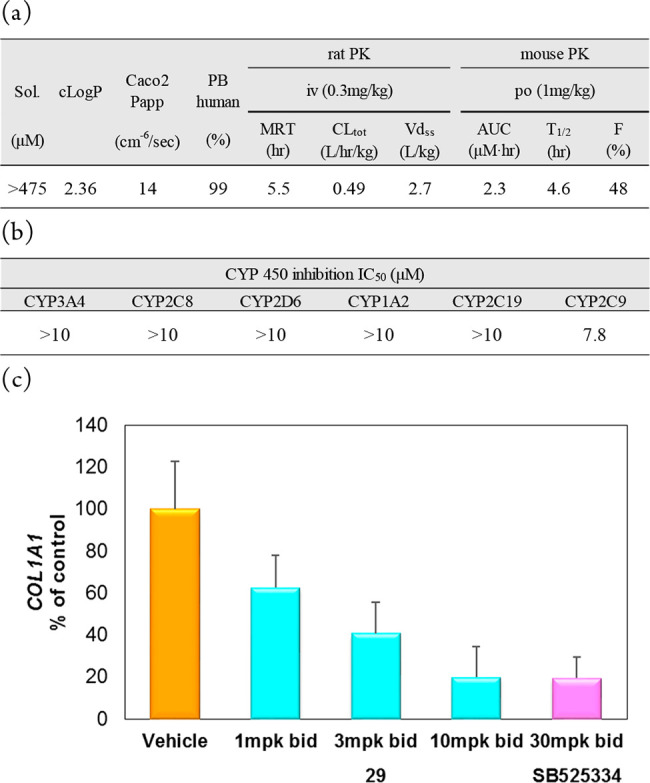

Among analogues of 26 possessing dimethylated glycol pendants (28–30), compound 29 showed the best functional selectivity for SMAD3 phosphorylation, as indicated by its superb TGF-βRII selectivity over ACVR2A. In order to understand the high selectivity of 29, a docking model was generated by superimposition of this compound with the cocrystallized ligand 20 (Figure 1a). Two closely related receptor kinases, ACVR2A and ALK5 (roughly 100-fold selectivity over this receptor was confirmed as the result of the kinase panel study shown in the Supporting Information), were chosen as representative off targets, and their cystal structures were successively superimposed with the corresponding residues of TGF-βRII. As demonstrated in Figure 1b, it is hypothesized that both ACVR2A and ALK5 cannnot get optimal interactions in two subsites where Asn332 and Cys396 are present in TGF-βRII, since they commonly possess smaller amino acids (Ser and Ala, respectively) in those locations. Moreover, Ala199 of ACVR2A could cause a steric crash with the methyl substituent on the pyrazole ring, rationalizing the significant loss of ACVR2A potency. To this end, a lead compound that was subjected to in vivo experiments was selected among the TGF-βRII inhibitors listed in Table 4. Obviously, high selectivity and good PK profiles are crucial features of the probe molecule to clarify TGF-βRII-dependent signaling in vivo. We thus prioritized functional selectivity (TGF-β over activin) in the cell assays with metabolic stability as the criteria for the selection. Among the most potent compounds in the cell (24, 26, 27, 28, and 29), compound 29 stood out for having the highest metabolic stability and best functional selectivity by over 300-fold. As expected from its physicochemical properties, the solubility and caco2 cell permeability of 29 were generally good, which surely reflected favorable PK profiles, fulfilling the good quality of a probe molecule (Figure 2a). The toxicity-related off-target potencies, including hERG (IC50 = 22.8 μM) and CYP (IC50 > 10 μM, CYP3A4, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, CYP1A2, CYP2C19; IC50 = 7.8 μM, CYP2C9), were also sparing (Figure 2b). Therefore, this compound was determined to be a suitable molecule to clarify the role of TGF-βRII-dependent signaling. To assess disease-amelioration effects in vivo, the TGF-β-induced mouse fibrosis model was selected, and three doses of 29 were administered orally to the tested subjects (Figure 2c). The skin concentration of collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) was monitored as a plasma marker of fibrosis, and significant reduction of the mRNA level was observed in a dose-dependent manner with no sign of cardiac side effects. Moreover, the 10 mg/kg dose groups reached full efficacy, being comparable in effectiveness with the known ALK5 inhibitor (SB525334), indicating that selective TGF-βRII inhibition could afford a new option to treat skin diseases, including SSc.

Figure 2.

ADME profiles and in vivo results for 29. (a) In vitro ADME parameters and PK parameters. (b) CYP inhibition profile. (c) The skin (ear) concentration of collagen type I alpha 1 chain (COL1A1) was monitored as a plasma marker of fibrosis. Oral administration of compound 29 resulted in significant reduction of the mRNA level in a dose-dependent manner. The 10 mg/kg dose groups reached full efficacy, being comparable in effectiveness with the known ALK5 inhibitor SB525334.10

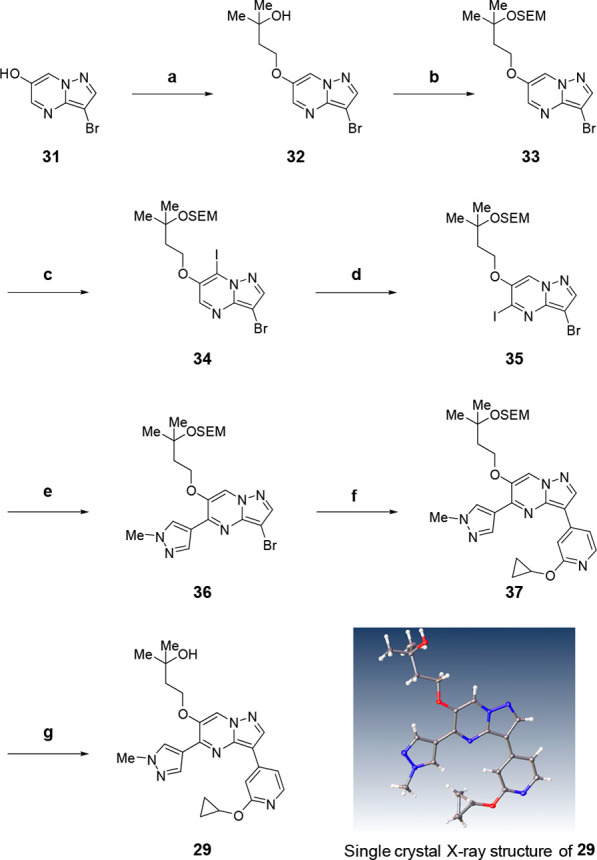

Compound 29 was synthesized following the procedures depicted in Scheme 1. O-Alkylation of 31 was conducted, and acetal formation to install SEM protection was successfully carried out. Unfortunately, subsequent attempts to directly transform 35 were unsuccessful, and only the undesired regioisomer 34 was obtained. Eventually, base-assisted iodine migration solved the problem, and 35 was prepared effectively by treatment of 34 with Knochel–Hauser base.26,27 This compound was further subjected to Suzuki coupling with 1-methylpyrazole-3-borate to afford 36, which was coupled with O-alkylated pyridine-4-borate, followed by final acidic workup to give the target molecule 29.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 29.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 4-bromo-2-methylbutan-2-ol, Cs2CO3, DMF, r.t.; (b) SEMCl, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, r.t., 91% for two steps; (c) (i) TMPMgCl·LiCl, THF, −78 °C, (ii) I2, THF, −78 to 0 °C, 66%; (d) (i) TMPMgCl·LiCl, THF, −78 °C, (ii) AcOH, THF, −78 to 0 °C, 94%; (e) 1-methyl-4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole, Pd(PPh3)4, K3PO4, DME, H2O, 100 °C, 58%; (f) 2-cyclopropoxy-4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)pyridine, RuPhos Pd G2, K3PO4, DME, H2O, 100 °C, 26%; (g) TFA, CH2Cl2, r.t., 40%.

In summary, synthetic explorations were carried out to generate novel molecules that selectively inhibited TGF-βRII-dependent signaling. Starting from a less potent TGF-βRII inhibitor with no cell potency (3), significant improvement was achieved, and the best compound, 29, demonstrated a nanomolar IC50 against TGF-β-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation. More importantly, its 300-fold functional selectivity over the effect on activin-initiated SMAD3 phosphorylation (IC50 = 9 nM for TGF-β vs 2900 nM for activin) was notable. To assess the kinase selectivity, typical kinases were chosen within eight branches of the kinome, and the inhibitory activity of 29 was determined against them. Generally, high selectivity (over roughly 100-fold) was observed, except for DYRK2 (75% inhibition at 0.1 μM), which is not found in SMAD signaling and would have little effect on clarifying TGF-βRII pharmacology.28

The new finding regarding the “halogen dance rearrangement” should also be emphasized since it successfully allowed us to access 3,6-disubstituted-5-iodopyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines. The concept of halogen dance rearrangement was originally proposed in 1951,29 but there have been unexpectedly few examples of its use in past drug discovery programs. As a matter of fact, there have been no reports applying such methodology to obtain drug-like molecules with pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine, and the application of this type of reaction could accelerate the discovery of future clinical candidates since heteroaromatics, including pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine, are found within many bioactive molecules. The TGF-β signaling pathway has had a long history as the site of promising targets typified in cancer therapy. Meanwhile, a lack of selective ligands has hampered a clear understanding of the respective roles of TGF-β receptors with complex phenotypes in cells and in vivo. For instance, SB525334, known as a pan-inhibitor of ALK4 and ALK5,10 demonstated similar antifibrotic effects regardless of different fibrotic initiators, while TGF-β and bleomycin, though selective TGF-βRII inhibitors, were found to show reduced potency in the blemomycin-induced model (data not shown). As far as we know, this is the first example to demonstrate small-molecule-based inhibition of TGF-βRII signaling leading to an in vivo antifibrotic effect. It is known that receptors of the TGF-β superfamily work modularly and mediate a variety of signals by forming distinct oligomers. Because of this complex nature, downstream signaling of each receptor is so diverse and hardly interpretable. Suffice it to say that 29 is an ideal molecule, conferring subnanomolar enzyme inhibition, excellent cell potency, and functional selectivity. Although further understanding of selective TGF-βRII inhibition, especially at the gene regulation level, is beyond the scope of this study, the discovery of selective ligands for each TGF-β receptor symbolized by this compound will definitely accelerate future clarification of the TGF-β superfamily signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank Takahiro Iwai for single-crystal X-ray structure analysis, Eita Nagao for HRMS analysis, and Dr. Satoru Noji for helpful discussions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- hERG

human ether-a-go-go-related gene

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SEM

2-(trimethylsilyl)ethoxymethyl

- SMAD

mothers against decapentaplegic homologue

- RuPhos Pd G2

chloro(2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-diisopropoxy-1,1′-biphenyl)[2-(2′-amino-1,1′-biphenyl)]palladium(II)

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TMP

tetramethylpiperidinyl

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00679.

Synthetic schemes, procedures, experimental data, biological protocols, and crystallography details (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Yingling J. M.; Blanchard K. L.; Sawyer J. S. Development of TGF-β signalling inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2004, 3, 1011–1022. 10.1038/nrd1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Györfi A. H.; Matei A.-E.; Distler J. H. W. Targeting TGF-β signaling for the treatment of fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2018, 68–69, 8–27. 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice L. M.; Padilla C. M.; McLaughlin S. R.; Mathes A.; Ziemek J.; Goummih S.; Nakerakanti S.; York M.; Farina G.; Whitfield M. L.; Spiera R. F.; Christmann R. B.; Gordon J. K.; Weinberg J.; Simms R. W.; Lafyatis R. Fresolimumab treatment decreases biomarkers and improves clinical symptoms in systemic sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 2795–2807. 10.1172/JCI77958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago B.; Gutierrez-Cañas I.; Dotor J.; Palao G.; Lasarte J. J.; Ruiz J.; Prieto J.; Borrás-Cuesta F.; Pablos J. L. Topical application of a peptide inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta1 ameliorates bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 450–455. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga J.; Pasche B. Transforming growth factor β as a therapeutic target in systemic sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009, 5, 200–206. 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00432-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin C. H.; Miyazono K.; ten Dijke P. TGF-β signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature 1997, 390, 465–471. 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. How cells read TGF-β signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 169–178. 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boys M. L.; Bian F.; Kramer J. B.; Chio C. L.; Ren X.-D.; Chen H.; Barrett S. D.; Sexton K. E.; Iula D. M.; Filzen G. F.; Nguyen M. N.; Angell P.; Downs V. L.; Wang Z.; Raheja N.; Ellsworth E. L.; Fakhoury S.; Bratton L. D.; Keller P. R.; Gowan R.; Drummond E. M.; Maiti S. N.; Hena M. A.; Lu L.; McConnell P.; Knafels J. D.; Thanabal V.; Sun F.; Alessi D.; McCarthy A.; Zhang E.; Finzel B. C.; Patel S.; Ciotti S. M.; Eisma R.; Payne N. A.; Gilbertsen R. B.; Kostlan C. R.; Pocalyko D. J.; Lala D. S. Discovery of a series of 2-(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)pyridines as ALK5 inhibitors with potential utility in the prevention of dermal scarring. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3392–3397. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grygielko E. T.; Martin W. M.; Tweed C.; Thornton P.; Harling J.; Brooks D. P.; Laping N. J. Inhibition of gene markers of fibrosis with a novel inhibitor of transforming growth factor-β type I receptor kinase in puromycin-induced nephritis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 943–951. 10.1124/jpet.104.082099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gouville A.-C.; Boullay V.; Krysa G.; Pilot J.; Brusq J.-M.; Loriolle F.; Gauthier J.-M.; Papworth S. A.; Laroze A.; Gellibert F.; Huet S. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling by an ALK5 inhibitor protects rats from dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver fibrosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 145, 166–177. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty S.; Dugar S.; Higgins L. S.; Kapoun A. M.; Liu D. Y.; Schreiner G. F.; Protter A. A.; Tran T.-T.. Treatment of fibroproliferative disorders using TGF-β inhibitors. WO 2003/097615 A1 and PCT/US03/15514, November 27, 2003.

- Fu K.; Corbley M. J.; Sun L.; Friedman J. E.; Shan F.; Papadatos J. L.; Costa D.; Lutterodt F.; Sweigard H.; Bowes S.; Choi M.; Boriack-Sjodin P. A.; Arduini R. M.; Sun D.; Newman M. N.; Zhang X.; Mead J. N.; Chuaqui C. E.; Cheung H.-K.; Zhang X.; Cornebise M.; Carter M. B.; Josiah S.; Singh J.; Lee W.-C.; Gill A.; Ling L. E. SM16, an orally active TGF-β type I receptor inhibitor prevents myofibroblast induction and vascular fibrosis in the rat carotid injury model. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 665–671. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.158030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M.; Thorikay M.; Deckers M.; van Dinther M.; Grygielko E. T.; Gellibert F.; de Gouville A.-C.; Huet S.; ten Dijke P.; Laping N. J. Oral administration of GW788388, an inhibitor of TGF-β type I and II receptor kinases, decreases renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 705–715. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.-J.; Park S.-A.; Kim C. H.; Park S.-Y.; Kim J.-S.; Kim D.-K.; Nam J.-S.; Sheen Y. Y. TGF-β type I receptor kinase inhibitor EW-7197 suppresses cholestatic liver fibrosis by inhibiting HIF1α-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 571–588. 10.1159/000438651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderton M. J.; Mellor H. R.; Bell A.; Sadler C.; Pass M.; Powell S.; Steele S. J.; Roberts R. R. A.; Heier A. Induction of heart valve lesions by small-molecule ALK5 inhibitors. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011, 39, 916–924. 10.1177/0192623311416259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velaparthi U.; Darne C. P.; Warrier J.; Liu P.; Rahaman H.; Augustine-Rauch K.; Parrish K.; Yang Z.; Swanson J.; Brown J.; Dhar G.; Anandam A.; Holenarsipur V. K.; Palanisamy K.; Wautlet B. S.; Fereshteh M. P.; Lippy J.; Tebben A. J.; Sheriff S.; Ruzanov M.; Yan C.; Gupta A.; Gupta A. K.; Vetrichelvan M.; Mathur A.; Gelman M.; Singh R.; Kinsella T.; Murtaza A.; Fargnoli J.; Vite G.; Borzilleri R. M. Discovery of BMS-986260, a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable TGFβR1 inhibitor as an immuno-oncology agent. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 172–178. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Lawson J. D.; Scorah N.; Kamran R.; Hixon M. S.; Atienza J.; Dougan D. R.; Sabat M. Design, synthesis and optimization of novel Alk5 (Activin-like kinase 5) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 4334–4339. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Nguyen N. B.; Pezhouman A.; Ardehali R. Cardiac fibrosis: potential therapeutic targets. Transl. Res. 2019, 209, 121–137. 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munchhof M. J.Isothiazole derivatives. WO 2004/067530 A1 and PCT/IB2004/000122, August 12, 2004.

- Tigno-Aranjuez J. T.; Benderitter P.; Rombouts F.; Deroose F.; Bai X.; Mattioli B.; Cominelli F.; Pizarro T. T.; Hoflack J.; Abbott D. W. In vivo inhibition of RIPK2 kinase alleviates inflammatory disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 29651–29664. 10.1074/jbc.M114.591388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munchhof M. J.Pyrazine compounds as transforming growth factor (TGF) inhibitors. WO 2004/080982 A1 and PCT IB2004/000581, September 23, 2004.

- Attisano L.; Wrana J. L.; Montalvo E.; Massagué J. Activation of signalling by the activin receptor complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 1066–1073. 10.1128/MCB.16.3.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight Z. A.; Shokat K. M. Features of selective kinase Inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 621–637. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Zapatero C. Ligand efficiency indices for effective drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2007, 2, 469–488. 10.1517/17460441.2.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkenhohl M.; Greiner R.; Makarov I. S.; Heinz B.; Karaghiosoff K.; Zipse H.; Knochel P. Zn-, Mg-, and Li-TMP bases for the successive regioselective metalations of the 1,5-naphthyridine scaffold (TMP = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidyl). Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 13046–13050. 10.1002/chem.201703638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proust N.; Chellat M. F.; Stambuli J. P. Mechanistic insight into the halogen dance rearrangement of iodooxazoles. Synthesis 2011, 2011, 3083–3088. 10.1055/s-0030-1260164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinase panel results are provided in the Supporting Information.

- Vaitiekunas A.; Nord F. F. Tetrabromothiophene from 2-bromothiophene by means of sodium acetylide in liquid ammonia. Nature 1951, 168, 875–876. 10.1038/168875a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.