Abstract

Candida species are the most common fungal pathogens to infect humans, and can cause life-threatening illnesses in individuals with compromised immune systems. Fluconazole (FLU) is the most frequently administered antifungal drug, but its therapeutic efficacy has been limited by the emergence of drug-resistant strains. When co-administered with minocycline (MIN), FLU can synergistically treat clinical Candida albicans isolates in vitro and in vivo. However, there have been few reports regarding the synergistic efficacy of MIN and azoles when used to treat FLU-resistant Candida species, including Candida auris. Herein, we conducted a microdilution assay wherein we found that MIN and posaconazole (POS) showed the best in vitro synergy effect, functioning against 94% (29/31) of tested strains, whereas combinations of MIN+itraconazole (ITC), MIN+voriconazole (VOR), and MIN+VOR exhibited synergistic activity against 84 (26/31), 65 (20/31), and 45% (14/31) of tested strains, respectively. No antagonistic activity was observed for any of these combinations. In vivo experiments were conducted in Galleria mellonella, revealing that combination treatment with MIN and azoles improved survival rates of larvae infected with FLU-resistant Candida. Together, these results highlight MIN as a promising synergistic compound that can be used to improve the efficacy of azoles in the treatment of FLU-resistant Candida infections.

Keywords: minocycline, fluconazole resistant Candida spp., Candida auris, antifungal, azole, synergy

Introduction

Invasive fungal infections represent an increasingly common threat to human health (Firacative, 2020), with Candida species serving as the leading cause of fungal infections and the fourth most prominent source of bloodstream infections globally, resulting in over 750,000 infections and a 40% mortality rate globally each year (McCarty and Pappas, 2016; Tsay et al., 2020). Candida albicans is the leading pathogenic member of this family, accounting for roughly half of these infections, followed by Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei. In total, these five species cause 90% of candidaemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis (Goemaere et al., 2018).

Fluconazole (FLU) is the most commonly prescribed antifungal drug, but its utility is increasingly limited by the emergence of drug-resistant strains (Perfect and Ghannoum, 2020). Approximately 0.5–2% of C. albicans isolates are resistant to FLU, while these resistance frequencies, respectively, range from 4 to 9, 2 to 6, and 11 to 13% for C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata (Berkow and Lockhart, 2017). Candida auris is an emerging pathogen, and 93% of these isolates are resistant to FLU with varying levels of resistance to other azoles, making it a particularly dangerous nosocomial pathogen with mortality rates of 30–60% (Berkow and Lockhart, 2017; Forsberg et al., 2019). As such, there is a clear need to identify reliable antifungal agents or compounds capable of enhancing the antifungal activity of extant compounds in order to improve patient outcomes.

Minocycline (MIN) is a second-generation semi-synthetic tetracycline analog that is widely used in clinical settings (Asadi et al., 2020). It exhibits a high degree of fat solubility, and can readily pass through the blood-brain barrier (Yong et al., 2004). MIN exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, and can be used to combat multidrug-resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Sapadin and Fleischmajer, 2006). Importantly, MIN has also been shown to function synergistically with FLU when treating clinical C. albicans isolates in vitro and in vivo (Shi et al., 2010; Gu et al., 2018). As such, MIN may represent a promising drug that can be administered in combination with other azoles to treat infections caused by C. auris and other pathogenic Candida species.

In order to test this hypothesis, we explored the in vitro activity of MIN alone or in combination with FLU, itraconazole (ITC), voriconazole (VOR), or posaconazole (POS) against FLU-resistant Candida isolates. The in vivo effect of drug combination was evaluated using Galleria mellonella, as it is an ideal model system for studies of antifungal drug activity.

Materials and Methods

Fungal Isolates

In total, 31 Candida isolates were utilized in the present analysis, including eight FLU resistant C. albicans, three FLU resistant C. parapsilosis, four FLU resistant C. tropicalis, six FLU susceptible dose-dependent C. glabrata strains, and 10 C. auris strains. All of these strains were clinical isolates, with the C. auris strains having been obtained from the CDC and FDA Antibiotic Resistance Isolate Bank. The identities of all strains were confirmed based on morphological evaluation and sequencing of the ITS and D1/D2 regions. Candida parapsilosis (ATCC22019) was included to ensure quality control.

Antifungal Agents

FLU (No. S1131), VOR (No. S1442), ITC (No. S2476), POS (No. S1257), and MIN (No. S4226) were obtained in a powdered form from Selleck Chemicals (TX, United States), and were prepared as detailed in M27-A4 (CLSI, 2017). Working concentration ranges were 0.03–16 μg/ml for ITC, VOR, and POS, and 0.25–64 μg/ml for FLU and MIN.

Inoculum Preparation

Yeast conidia were collected from isolates incubated for 24 h on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 30°C. Yeast conidia were resuspended at 1–5 × 106 cfu/ml in sterile saline, and were then diluted 1,000-fold using RPMI-1640 to yield a suspension that was twice as concentrated as required (1–5 × 103 cfu/ml).

Testing the in vitro Synergy of MIN and Azoles

A broth microdilution checkerboard assay approach was used for the present study, having been adapted from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A4 (CLSI, 2017). First, 50 μl volumes of MIN serial dilutions were applied horizontally to the wells of a 96-well plate containing 100 μl of prepared inoculum suspension, after which 50 μl volumes of azole serial dilutions were applied vertically to the wells of this same plate. Results were then analyzed after a 24 h incubation at 35°C.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were the lowest drug concentrations that suppressed fungal growth by 50% relative to control treatment at the end of the 24 h incubation. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was used to assess MIN and azole interactions, and was calculated with the equation: FICI = (Ac/Aa) + (Bc/Ba), where Ac and Bc are the MIC values of tested agents in combination, while Aa and Ba correspond to these values for single-agent A and B treatments. A FICI of ≤0.5 is considered to indicate synergy, while a FICI of >0.5 to ≤4 is indicative of a lack of any interaction, and a FICI of >4 corresponds to an antagonistic interaction. Experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Assessment of the in vivo Activity of MIN Alone and in Combination With Azoles

As discussed previously (Jiang et al., 2020), survival tests were conducted with sixth instar larvae (300 mg; Sichuan, China) to evaluate the efficacy of MIN as a single-agent and in combination with azole drugs on G. mellonella infected with C. albicans R14, C. parapsilosis N101, C. tropicalis 00279, C. glabrata 05448, and C. auris AR385. Larvae were stored in the dark at room temperature with shavings prior to experimental use, while Candida strains had been grown for 2 days on PDA, after which the colony surface was scraped with a sterile plastic loop, washed two times, and adjusted to 1 × 108 cfu/ml using sterile saline. Control larval groups injected with saline, conidial suspensions, or nothing were established.

To explore the in vivo synergistic activity of MIN and azoles against pathogenic fungi, nine treatment groups were established: MIN, FLU, ITC, POS, VOR, MIN+FLU, MIN+ITC, MIN+POS, and MIN+VOR groups. Conidia suspensions were inoculated into larvae (10 μl per larvae) using a Hamilton syringe (25 gauge, 50 μl), and antifungal agents or a control solution (1 μg per larvae; drug concentration = 200 mg/L) was introduced into the larvae through the last left proleg after the area was cleaned with an alcohol swab. Within 120 h following infection, larval survival rates were recorded every 24 h. Galleria mellonella survival curves were assessed via the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, with p < 0.05 as a significance threshold.

Results

MIN and Azoles Interactions in vitro

A checkerboard microdilution assay was initially performed to explore the antifungal activity levels of different azoles alone and in combination with MIN when used to treat different Candida spp. in vitro (Tables 1 and 2). POS showed the best synergistic activity with MIN, achieving activity against 100% of tested C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. glabrata strains and against 80% of tested C. auris strains. A combination of MIN and ITC exhibited synergistic activity against 100% of C. parapsilosis strains, 90% of C. auris strains, 83% of C. glabrata strains, and 75% of C. albicans and C. tropicalis strains. In combination with FLU, MIN exhibited synergistic efficacy against 75% of C. albicans, 70% of C. auris, 67% C. glabrata, 50% C. tropicalis, and 33% C. parapsilosis strains. Combination MIN and VOR treatment exhibited the poorest synergistic activity, affecting just 80% of C. auris, 50% of C. albicans, 33% of C. glabrata, and 0% of C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis strains.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values pertaining to combinations of minocycline (MIN) and azoles when used to treat Candida spp.

| No. | Species | MICs (μg/ml)1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent alone | Combination2 | |||||||||

| MIN | ITC | VOR | POS | FLU | MIN/ITC | MIN/VOR | MIN/POS | MIN/FLU | ||

| ATCC 64550 | C.albicans | >64 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8 | 16/0.5(I) | 1/0.25(I) | 16/0.125(S) | 1/8(I) |

| R1 | >64 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 4/1(S) | 16/0.5(S) | 4/0.5(S) | 4/2(S) | |

| R3 | >64 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 32 | 4/1(I) | 32/0.125(I) | 4/0.25(S) | 1/16(I) | |

| R4 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 8/0.5(S) | 32/0.5(I) | 4/0.25(S) | 16/4(S) | |

| R9 | >64 | >16 | 16 | 8 | >64 | 8/0.5(S) | 8/0.25(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 2/1(S) | |

| R14 | >64 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 16 | 2/0.5(S) | 2/0.5(S) | 2/0.25(S) | 1/4(S) | |

| R15 | >64 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 4/0.5(S) | 4/0.25(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 8/4(S) | |

| N175 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4/0.5(S) | 2/0.5(I) | 4/0.25(S) | 16/0.5(S) | |

| N87 | C.parapsilosis | >64 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 16 | 4/0.5(S) | 32/0.5(I) | 4/0.125(S) | 16/4(S) |

| N101 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 1 | >32 | 8/1(S) | 32/0.125(I) | 4/0.125(S) | 32/1(I) | |

| N112 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 16 | 8/0.5(S) | 8/0.5(I) | 4/0.125(S) | 32/1(I) | |

| 00279 | C.tropicalis | >64 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 64 | 16/0.5(S) | 1/0.5(I) | 8/0.125(S) | 32/64(I) |

| N205 | >64 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 32 | 32/1(I) | 32/0.5(I) | 8/0.25(S) | 8/2(S) | |

| N331 | >64 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 32 | 4/0.5(S) | 32/0.25(I) | 8/0.25(S) | 32/1(I) | |

| N336 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 8/0.5(S) | 32/1(I) | 4/0.25(S) | 16/4(S) | |

| 05448 | C. glabrata | 64 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 8/0.5(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 8/0.125(S) | 16/0.5(S) |

| C5 | >64 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | 2/0.5(I) | 32/0.125(I) | 8/0.125(S) | 16/1(S) | |

| C35 | >64 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | 8/0.5(S) | 32/0.5(I) | 4/0.25(S) | 16/2(S) | |

| C128 | >64 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 8/0.25(S) | 4/0.5(S) | 8/0.25(S) | 16/1(S) | |

| N180 | >64 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 2/0.5(S) | 32/0.125(I) | 4/0.125(S) | 4/4(I) | |

| N199 | >64 | 4 | 1 | 1 | >32 | 8/0.5(S) | 32/0.5(I) | 2/0.25(S) | 16/16(I) | |

| AR381 | C. auris | >64 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 4 | 1/0.125(I) | 1/0.125(I) | 1/0.125(I) | 16/2(I) |

| AR382 | >64 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 16 | 8/0.125(S) | 2/0.25(S) | 1/0.125(S) | 8/1(S) | |

| AR383 | >64 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 | 128 | 4/0.25(S) | 4/1(S) | 1/0.125(I) | 8/8(S) | |

| AR384 | >64 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 128 | 8/0.125(S) | 2/0.125(S) | 8/0.125(S) | 16/2(S) | |

| AR385 | >64 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 128 | 8/0.25(S) | 1/1(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 16/4(S) | |

| AR386 | >64 | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 128 | 4/0.125(S) | 1/1(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 32/8(I) | |

| AR387 | >64 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 8 | 2/0.125(S) | 2/0.125(S) | 2/0.125(S) | 4/1(S) | |

| AR388 | >64 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | 128 | 8/0.5(S) | 16/4(I) | 8/0.125(S) | 16/4(S) | |

| AR389 | >64 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 128 | 16/0.25(S) | 16/1(S) | 8/0.125(S) | 8/2(S) | |

| AR390 | >64 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 128 | 8/0.125(S) | 4/0.125(S) | 8/0.125(S) | 32/8(I) | |

The MIC is the concentration resulting in 50% growth inhibition.

fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) results are shown in parentheses. S, synergy (FICI <0.5); I, no interaction (indifference, 0.5 < FICI < 4).

Table 2.

Summary of in vitro drug interactions.

| Species(n) | n (%) of isolates showing synergism for the combination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIN/ITC | MIN/VOR | MIN/POS | MIN/FLU | |

| C.albicans (8) | 6(75%) | 4(50%) | 8(100%) | 6(75%) |

| C.parapsilosis (3) | 3(100%) | 0(0%) | 3(100%) | 1(33%) |

| C.tropicalis (4) | 3(75%) | 0(0%) | 4(100%) | 2(50%) |

| C.glabrata (6) | 5(83%) | 2(33%) | 6(100%) | 4(67%) |

| C.auris (10) | 9(90%) | 8(80%) | 8(80%) | 7(70%) |

| Total (31) | 26(84%) | 14(45%) | 29(94%) | 20(65%) |

MIN and Azoles Interactions in vivo

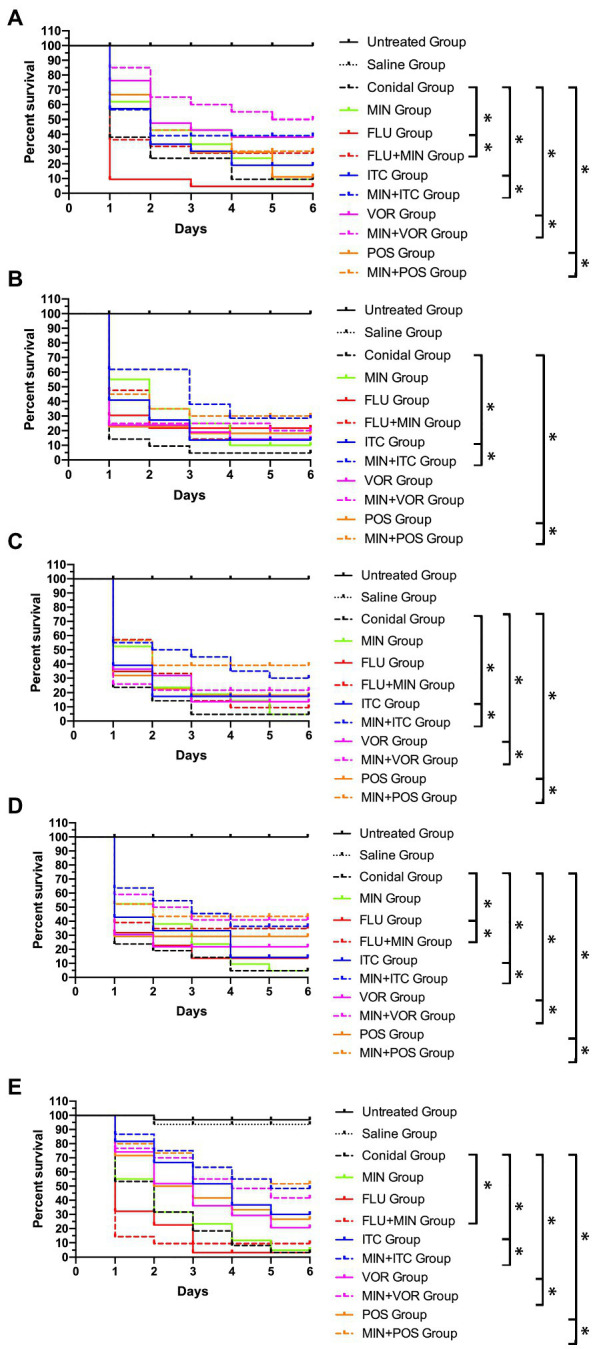

Next, we performed in vivo antifungal activity assays using G. mellonella as a model system, with survival rates for the larvae in each group being shown in Table 3 and Figure 1. Treatment with MIN alone had no effect on any of the five Candida spp. groups. When combined with FLU, however, this treatment significantly prolonged the survival of larvae infected with C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. auris (p < 0.05), with a particularly noteworthy increase in the survival rate of larvae infected with C. glabrata from 5 to 25%. Combination treatment with ITC was associated with significantly prolonged larval survival rates in all groups (p < 0.05), with a particularly pronounced increase of 30% in the C. glabrata group. Combination MIN + VOR treatment significantly prolonged the survival (p < 0.05) of all larvae other than those infected with C. parapsilosis, with maximal synergy being observed for larvae infected with C. tropicalis for which the survival rate rose by 30%. Combination MIN + POS treatment also significantly (p < 0.05) increased survival in all groups, particularly in the C. auris group in which the survival rate reached 51.67%.

Table 3.

Summary of in vivo drug interactions.

| Drugs | Survival rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. abicans | C. parapsilosis | C. tropicalis | C. glabrata | C. auris | |

| FLU | 0.00% | 10.00% | 5.00% | 5.00% | 0.00% |

| FLU+MIN | 20.00% | 5.00% | 5.00% | 25.00% | 5.00% |

| ITC | 15.00% | 5.00% | 5.00% | 10.00% | 30.00% |

| ITC+MIN | 30.00% | 25.00% | 30.00% | 40.00% | 48.33% |

| VOR | 35.00% | 10.00% | 5.00% | 10.00% | 20.00% |

| VOR+MIN | 50.00% | 20.00% | 35.00% | 25.00% | 41.67% |

| POS | 10.00% | 10.00% | 10.00% | 15.00% | 26.67% |

| POS+MIN | 25.00% | 30.00% | 30.00% | 35.00% | 51.67% |

Figure 1.

Galleria mellonella survival curves following infection with Candida spp. (A) Candida albicans R14; (B) Candida parapsilosis N101; (C) Candida tropicalis 00279; (D) Candida glabrata 05448; (E) Candida auris AR385; Untreated Group, wild type uninfected larvae; Saline Group, wild type larvae injected with saline; Conidial Group, larvae infected with Candida without any treatment; MIN Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with MIN only; fluconazole (FLU) Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with FLU only; itraconazole (ITC) Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with ITC only; voriconazole (VOR) Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with VOR only; posaconazole (POS) Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with POS only; MIN+FLU Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with MIN combined with FLU; MIN+ITC Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with MIN combined with ITC; MIN+VOR Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with MIN combined with VOR; MIN+POS Group, Candida-infected larvae treated with MIN combined with POS. ∗p < 0.05.

Discussion

Minocycline was first identified as an inhibitor of C. albicans growth in 1974 (Waterworth, 1974), and several studies have further highlighted the antifungal activity of this compound. Shi et al. (2010) and Gu et al. (2018) demonstrated the ability of MIN to synergize with FLU against C. albicans in vitro and in vivo and Gao et al. (2013) observed synergy between tetracycline and FLU when treating C. albicans biofilms. MIN has also been shown to synergize with azoles in the treatment of other fungal species. Kong et al. (2020) determined that MIN was able to synergize with FLU in vivo and in vitro when treating Cryptococcus neoformans, while Gao et al. (2020) reported synergy between MIN and azoles when treating clinically important Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Exophiala dermatitidis isolates. Herein, we explored the synergistic activity of MIN in combination with azoles when treating FLU-resistant C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. auris.

Consistent with other studies, we found that MIN was able to enhance fungal sensitivity to azole treatment both in vitro and in vivo. In our in vitro analyses, MIN and POS showed 100% in vitro synergy effect in C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata group, functioning against 94% (29/31) of tested strains, whereas combinations of MIN+ITC, MIN+FLU, and MIN+VOR exhibited synergistic activity against 84 (26/31), 65 (20/31), and 45% (14/31) of tested strains, respectively. The C. auris strains used in this study belonged to four different clusters, with AR382, AR387, AR388, AR389, and AR390 belonging in cluster I, AR381 belonging in cluster II, AR383 and AR384 belonging in cluster III, and AR385 and AR386 belonging in cluster IV (Vatanshenassan et al., 2020). No differences among these clusters were detected in our in vitro analyses.

Our in vivo experiment utilized G. mellonella as an animal model, given that these larvae exhibit similar responses to those of mammals and can be used as an ideal model system for studies of antifungal drug activity. Our data indicated that MIN and VOR combination treatment exhibited the best synergistic efficacy in the context of C. albicans and C. tropicalis infections, while MIN+POS was most effective against C. parapsilosis and C. auris. For C. glabrata, a combination of MIN+ITC was most effective. However, our in vitro data were not in full accordance with our in vivo data, potentially because too few strains were used when conducting our in vivo study. Additionally, further studies that using mice as infection models are required.

In our data, MIN can reduce the MIC of azoles in some tested strains, while there was no change for the others. That can observed in others study either, Shi et al. (2010) showed MIN can reduce MIC of FLU in 50% tested C. albicans strains. We speculate that might associate with the mechanism of synergistic action. Though remains incompletely understood, the ability of MIN to enhance FLU efficacy may be related to efflux pump blockade, the stimulation of high levels of intracellular calcium, iron chelation, or the inhibition of mitochondrial functionality (Oliver et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2010; Fiori and Van Dijck, 2012; Gao et al., 2013). Further research that can clarify the mechanisms might help to address this question.

In summary, we found that MIN can synergize with azoles to improve the antifungal activity of these agents against azole-resistant Candida species, with particular efficacy against C. auris in vitro and in vivo. Given that resistance to azoles is associated with significant increases in treatment failure and mortality rates, overcoming drug resistance is a critical public health issue. Our results highlight the potential of MIN as a tool that can overcome such azole resistance when used to treat Candida infections, although further work will be required to confirm these results and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Even so, our results hold great promise, suggesting that MIN can be used to reliably enhance efforts to cure invasive azole-resistant Candida infections in clinical settings.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

JT, SJ, and LT carried out the in vitro and in vivo antifungal experiment. JT and HS collected and analyzed the experiment data. YS and XW designed and interpreted the experiment data and wrote the manuscript. LY and XW revised the manuscript critically for important content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Professor Haoping Liu from University of California, Irvine, for kindly providing us with isolates studied.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Hubei Province Health and Family Planning Scientific Research Project (grant number WJ2018H178 to YS and WJ2019M082 to SJ); the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (grant number 2019CFB567) to YS; and Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (grant number 201940476) to LY.

References

- Asadi A., Abdi M., Kouhsari E., Panahi P., Sholeh M., Sadeghifard N., et al. (2020). Minocycline, focus on mechanisms of resistance, antibacterial activity, and clinical effectiveness: Back to the future. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 22, 161–174. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.01.022, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkow E. L., Lockhart S. R. (2017). Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: a current perspective. Infect Drug Resist. 10, 237–245. 10.2147/IDR.S118892, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2017). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts. 4th Edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

- Fiori A., Van Dijck P. (2012). Potent synergistic effect of doxycycline with fluconazole against Candida albicans is mediated by interference with iron homeostasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 3785–3796. 10.1128/AAC.06017-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firacative C. (2020). Invasive fungal disease in humans: are we aware of the real impact? Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 115:e200430. 10.1590/0074-02760200430, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg K., Woodworth K., Walters M., Berkow E. L., Jackson B., Chiller T., et al. (2019). Candida auris: The recent emergence of a multidrug-resistant fungal pathogen. Med. Mycol. 57, 1–12. 10.1093/mmy/myy054, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L. j., Sun Y., Yuan M. Z., Li M., Zeng T. X. (2020). In Vitro and In Vivo study on the synergistic effect of minocycline and azoles against pathogenic fungi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64:e00290-20. 10.1128/AAC.00290-20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Zhang C. Q., Lu C. Y., Liu P., Li Y., Li H., et al. (2013). Synergistic effect of doxycycline and fluconazole against Candida albicans biofilms and the impact of calcium channel blockers. FEMS Yeast Res. 13, 453–462. 10.1111/1567-1364.12048, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goemaere B., Becker P., Van W. E., Maertens J., Spriet I., Hendrickx M., et al. (2018). Increasing candidaemia incidence from 2004 to 2015 with a shift in epidemiology in patients preexposed to antifungals. Mycoses 61, 127–133. 10.1111/myc.12714, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W. R., Yu Q., Yu C. X., Sun S. J. (2018). In vivo activity of fluconazole/tetracycline combinations in Galleria mellonella with resistant Candida albicans infection. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 13, 74–80. 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.11.011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Tang J., Wu Z. Q., Sun Y., Tan J. W., Yang L. J. (2020). The combined utilization of Chlorhexidine and Voriconazole or Natamycin to combat Fusarium infections. BMC Microbiol. 20:275. 10.1186/s12866-020-01960-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q. X., Cao Z. B., Lv N., Zhang H., Liu Y. Y., Hu L. F., et al. (2020). Minocycline and fluconazole have a synergistic effect against Cryptococcus neoformans both in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 11:836. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00836, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty T. P., Pappas P. G. (2016). Invasive candidiasis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 30, 103–124. 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.013, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B. G., Silver P. M., Marie C., Hoot S. J., Leyde S. E., White T. C. (2008). Tetracycline alters drug susceptibility in Candida albicans and other pathogenic fungi. Microbiology 154, 960–970. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013805-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect J. R., Ghannoum M. (2020). Emerging issues in antifungal resistance. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 34, 921–943. 10.1016/j.idc.2020.05.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapadin A. N., Fleischmajer R. (2006). Tetracyclines: nonantibiotic properties and their clinical implications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 54, 258–265. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W. N., Chen Z. Z., Chen X., Cao L. L., Liu P., Sun S. J. (2010). The combination of minocycline and fluconazole causes synergistic growth inhibition against Candida albicans: an in vitro interaction of antifungal and antibacterial agents. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 885–893. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00664.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay S. V., Mu Y., Williams S., Epson E., Nadle J., Bamberg W. M., et al. (2020). Burden of Candidemia in the United States, 2017. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, e449–e453. 10.1093/cid/ciaa193, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatanshenassan M., Boekhout T., Mauder N., Robert V., Maier T., Meis J. F., et al. (2020). Evaluation of microsatellite typing, ITS sequencing, AFLP fingerprinting, MALDI-TOF MS, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis of Candida auris. J. fungi 6:146. 10.3390/jof6030146, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterworth P. M. (1974). The effect of minocycline on Candida albicans. J. Clin. Pathol. 27, 269–272. 10.1136/jcp.27.4.269, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong V. W., Wells J., Giuliani F., Casha S., Power C., Metz L. M. (2004). The promise of minocycline in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 3, 744–751. 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00937-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.