Abstract

Introduction:

A recent study has shown that acetate administration leads to a fourfold increase in the transcription of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) mRNA in the hypothalamus. POMC is cleaved to peptides, including β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid (EO) agonist that binds preferentially to the µ-opioid receptor (MOR). We hypothesised that an acetate challenge would increase the levels of EO in the human brain. We have previously demonstrated that increased EO release in the human brain can be detected using positron emission tomography (PET) with the selective MOR radioligand [11C]carfentanil. We used this approach to evaluate the effects of an acute acetate challenge on EO levels in the brain of healthy human volunteers.

Methods:

Seven volunteers each completed a baseline [11C]carfentanil PET scan followed by an administration of sodium acetate before a second [11C]carfentanil PET scan. Dynamic PET data were acquired over 90 minutes, and corrected for attenuation, scatter and subject motion. Regional [11C] carfentanil BPND values were then calculated using the simplified reference tissue model (with the occipital grey matter as the reference region). Change in regional EO concentration was evaluated as the change in [11C]carfentanil BPND following acetate administration.

Results:

Following sodium acetate administration, 2.5–6.5% reductions in [11C]carfentanil regional BPND were seen, with statistical significance reached in the cerebellum, temporal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, striatum and thalamus.

Conclusions:

We have demonstrated that an acute acetate challenge has the potential to increase EO release in the human brain, providing a plausible mechanism of the central effects of acetate on appetite in humans.

Keywords: Acetate, PET, opioid

Introduction

A preclinical study has shown that a single intraperitoneal administration of acetate (500 mg/kg) led to a fourfold increase in the transcription of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) mRNA in the mouse hypothalamus which was linked to central appetite regulation (Frost et al., 2014). Acetate is formed in the colon by bacterial fermentation and tissue metabolism. Up to 70% of acetate is metabolised by the liver, where it is used as an energy source and substrate for the synthesis of cholesterol and long-chain fatty acids and as a co-substrate for glutamine and glutamate synthesis (Ballard, 1972; Knowles et al., 1974). POMC is cleaved to peptides, including β-endorphin, an endogenous opioid (EO) agonist that binds preferentially to the opioid receptor (Castro and Morrison, 1997). In vivo evaluation of any acetate-induced increases in EO released in the human brain will help us to understand the mechanism that acetate may play in human appetite regulation and its mediation by opioid signalling. In addition, acetate administration may be a useful paradigm to study EO release in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Opioid signalling plays a key role in appetite regulation and the development of obesity (Bessesen and Van Gaal, 2018). Animal studies have shown that palatable food consumption releases EO (Colantuoni et al., 2001; Dum et al., 1983). Consistent with this evidence, a human positron emission tomography (PET) study reported that feeding triggers cerebral opioid release, even in the absence of subjective pleasure effects (Tuulari et al., 2017). Moreover, PET studies in subjects with obesity have shown reduced µ-opioid receptor (MOR) availability (Joutsa et al., 2018; Karlsson et al., 2015, 2016), and it has been proposed that overeating leads to overstimulation of the MOR and concomitant downregulation.

Several pharmacological and non-pharmacological stimuli have been evaluated as methods to increase EO release. Previous PET studies with [11C]carfentanil and [11C]diprenorphine have shown that autobiographical sad mood induction, social rejection and positive emotion processing tasks lead to a change in binding in relevant brain regions (Hsu et al., 2015; Koepp et al., 2009; Prossin et al., 2016). Dexamphetamine challenge has been used successfully to demonstrate differences in EO release in healthy volunteers and patients with neuropsychiatric disorders (Colasanti et al., 2012; Mick et al., 2016). Moreover, development of a method that could enable EO release by increasing POMC transcription in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders is desirable, as the current methods use dexamphetamine, which may be challenging is some populations (e.g. psychosis or addictive disorders).

Human neuroimaging studies suggest that acetate crosses the blood–brain barrier (Chambers et al., 2015; Volkow et al., 2013). However, no data exist to indicate whether acetate could induce detectable changes in mu-opioid tracer binding, indicative of EO release, in humans. In view of these data, we used a PET imaging approach to test the hypothesis that an acetate challenge will increase the levels of EO in the brain of healthy human volunteers.

Methods

The study was approved by the West London Research Ethics Committee and the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, UK. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Seven healthy male volunteers were recruited into the study. Participants were screened using a medical history and physical examination, and current/previous medical and mental health, as well as the history of alcohol, tobacco and other substance use, were assessed by a trained study physician using the Mini Psychiatric Interview International (MINI-5; Sheehan et al., 1998). Subjects with current or previous psychiatric disorders were excluded. Participants were also excluded if they drank more than 14 UK units of alcohol per week. Other drug use (except tobacco) was not allowed for 2 weeks prior to the study. This was confirmed on the study day by a negative urine drug screen testing (cocaine, amphetamine, THC, methadone, opioids and benzodiazepines) and alcohol breath test. All subjects were asked to refrain from consuming caffeine and smoking on the day of the scan. None of the subjects met the criteria for any substance-use disorder.

All volunteers completed the [11C]carfentanil baseline PET scan in the morning followed by an infusion of 150 mmol of sodium acetate in 1 L normal saline over 60 minutes completed 30–60 minutes before a second [11C]carfentanil PET scan. All subjects had light food (sandwich) after the first scan. There was at least an hour’s rest period between food intake and initiation of acetate infusion. Due to technical reasons such as a delay in the production or quality-control checks, the PET tracer was injected between 20 and 70 minutes after acetate infusion. Five subjects underwent both PET scans on the same day. For two subjects, the post-acetate scan was acquired on a different day for logistical reasons.

Data acquisition

Dynamic [11C]carfentanil PET scans were acquired on a HiRez Biograph 6 PET/computed tomography (CT) scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), and data were collected continuously for 90 minutes (26 frames: 8×15 seconds, 3×60 seconds, 5×120 seconds, 5×300 seconds, 5×600 seconds), following an intravenous injection of [11C]carfentanil (Ashok et al., 2019). All participants underwent a T1-weighted structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Magnetom Trio Syngo MR B13 Siemens 3T; Siemens AG, Medical Solutions). All the structural images were reviewed by an experienced neuroradiologist for unexpected findings of clinical significance, and none were identified.

Image analysis

The preprocessing of images and PET modelling were carried out using MIAKAT software (Gunn et al., 2016). There was no significant difference in the head motion between pre and post scan. Regional time–activity data were sampled using the CIC neuroanatomical atlas after frame-by-frame motion correction of the dynamic PET data, (Tziortzi et al., 2011). This was applied to the PET image by non-linear deformation parameters derived from the transformation of the structural MRI into standard space. Previous functional MRI and preclinical studies have shown that food cue and consumption activates the hypothalamus, frontal lobe, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, striatum, temporal lobe, thalamus (Devoto et al., 2018; Volkow et al., 2012, 2017), insula (Wright et al., 2016), cingulate cortex (Meng et al., 2018) and cerebellum (Zhu and Wang, 2008), and these areas have a high density of MOR and can be reliably quantified. Based on these data, 10 grey-matter-masked regions of interest were chosen a priori based on the work above and the evidence of sufficient density of MOR that can be reliably quantified by PET imaging in the human brain (Colasanti et al., 2012). The simplified reference tissue model (Lammertsma and Hume, 1996) with the occipital lobe as the reference region (Colasanti et al., 2012) was used to derive regional BPND values at each PET scan. EO release was indexed as the fractional reduction in [11C]carfentanil BPND following the sodium acetate challenge:

.

Demographic, radiochemical and binding potential parameters were analysed using paired t-tests (two-tailed), and values are expressed as the mean±standard deviation. All statistical comparisons were assessed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). p-Values of <0.05 were accepted statistically significant.

Results

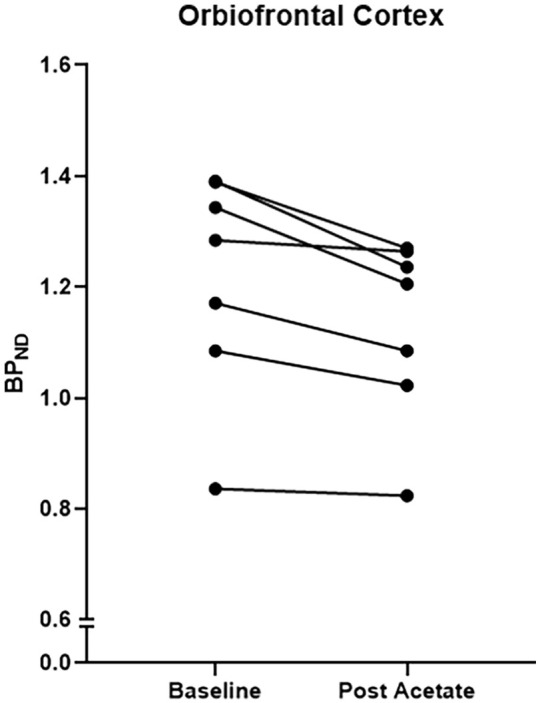

The mean age of the group was 39.1±10.5 years, and the body mass index was 24±3 kg/m2. There was no significant difference in the injected mass (Pre-acetate vs. Post acetate: 1.93±0.33 vs. 1.84±0.26 µg; p=0.53) and injected activity (Pre-acetate vs. Post acetate: 210±26.9 vs. 240±43 MBq; p=0.1). Following sodium acetate administration, [11C]carfentanil BPND was reduced in all regions and was statistically significant in the cerebellum, temporal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, striatum and thalamus (p<0.05; Table 1; Figure 1). Repeated-measures analysis of variance showed a significant effect of acetate administration on [11C]carfentanil BPND measures (p<0.05). Participants did not report a subjective difference in appetite following acetate infusion. Our cerebellar and orbitofrontal cortex findings survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction (p<0.05).

Table 1.

BPND at baseline and after acetate administration.

| Brain region | Baseline BPND, M (SD) | Post acetate BPND, M (SD) | ∆BPND (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellum | 0.82 (0.18) | 0.78 (0.18) | 5.1 | 0.003* |

| Insular cortex | 1.53 (0.18) | 1.47 (0.23) | 3.9 | 0.110 |

| Temporal lobe | 1.03 (0.13) | 0.99 (0.11) | 4.3 | 0.020* |

| Frontal lobe | 0.85 (0.15) | 0.82 (0.13) | 3.0 | 0.190 |

| Cingulate cortex | 1.29 (0.21) | 1.26 (0.21) | 2.7 | 0.110 |

| Amygdala | 1.62 (0.5) | 1.66 (0.16) | 6.9 | 0.860 |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | 1.21 (0.2) | 1.12 (0.16) | 6.5 | 0.007* |

| Striatum | 1.83 (0.17) | 1.73 (0.15) | 5.3 | 0.020* |

| Thalamus | 1.66 (0.09) | 1.57 (0.12) | 5.0 | 0.030* |

| Hypothalamus | 1.82 (0.24) | 1.75 (0.29) | 3.0 | 0.510 |

p<0.05.

SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Change in [11C]carfentanil binding potential in the orbitofrontal cortex following administration of sodium acetate administration.

Discussion

We have shown reductions in the binding of a MOR selective radiotracer – [11C]carfentanil – that are consistent with an increase in EO release in the human brain following acetate administration. Our data are consistent with our hypothesis that an acetate challenge will increase the levels of EO in the brain of healthy human volunteers. The change in [11C]carfentanil binding reached statistical significance in the orbitofrontal cortex, striatum, thalamus, cerebellum and the temporal lobe.

A previous study in mice showed that acetate derived from the fermentation of carbohydrate in the colon alters POMC neuron activity (Frost et al., 2014). We have now shown that peripheral acetate administration alters opioid signalling in the human brain. We did not detect a significant change in EO in the hypothalamus, where acetate administration was shown to alter POMC expression and neuronal activity in the mouse, and the location of POMC-expressing neurons (Frost et al., 2014). We measured opioid release rather than POMC expression or neuronal activity, and EO release may be expected in regions anatomically distant from the neuronal cell bodies in the hypothalamus. If acetate stimulates the production of EO peptides in hypothalamic neurons, these would be transported via axonal projections, and EO released in the striatum and cortical regions involved in food salience, where stimulation of MOR may occur (Cameron et al., 2017).

The mechanism of acetate-induced appetite regulation is speculative at this stage. The available evidence suggests that acetate enters the astrocytes, where it is metabolised in the TCA cycle, resulting in an increase in malonyl-CoA. The studies have also demonstrated that acetate increases the glutamate–glutamine cycle, triggering Ca2+ uptake. It remains unclear whether the changes in POMC mRNA expression (Frost et al., 2014) are causally related to the cellular changes above. The POMC neurons are heterogeneous, with varying levels of receptor expression (Toda et al., 2017). It has been suggested that melanocortin–opioid interactions are crucial in the regulation of feeding behaviour, as they are secreted in the same vesicle (Millington, 2007). Our study further supports the hypothesis that peripheral short-chain fatty acids such as acetate regulate central neurochemical signalling in the key regions involved in appetite regulation.

Our results have implications in understanding the association between acetate and its effect on brain regions implicated in the rewarding effect of alcohol. In a state of alcohol intoxication, the concentration of acetate in the blood is reported to increase to 0.5–1 mM (Korri et al., 1985; Orrego et al., 1988). Alcohol infusion has been shown to decreases brain glucose metabolism and increase [11C] acetate utilisation (Volkow et al., 2013). Consistent with this study, our results show elevated EO levels in the brain regions reported to have increased acetate utilisation in the intoxicated state. In addition, acute alcohol ingestion is shown to release EO (Mitchell et al., 2012), and there is blunting of opioid release in abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals (Turton et al., 2018). Together, these studies show that acetate-induced opioid release may be involved in the hedonic response to alcohol and alcohol-induced appetite suppression.

Our study has certain limitations. First, this is a small sample size pilot study, and our findings should be replicated in a larger number of subjects. Although we saw a reduction in the BPND values across all the brain regions, statistical significance was not seen in the insula, frontal lobe, cingulate cortex, amygdala and hypothalamus. Moreover, the magnitude of the change in [11C]carfentanil BPND PET signal is modest and may not be sufficient for robust quantification of dose-dependent effects. Second, we did not measure acetate plasma levels post administration. A previous PET study reported good brain uptake of [11C]acetate administered through an intravenous route (Volkow et al., 2013). The measurement of plasma acetate would have been useful. However, we felt that within the confines of a pilot study this was not essential, as our primary aim was to detect whether a large acetate load produced any effects on the brain EO system at all. If we were to find such an effect, subsequent investigations would evaluate the nature of a dose–effect relationship between acetate dose and magnitude of EO response. We believe that within the limited number of subjects in our study and the limited dose range used, measurement of plasma acetate would mainly serve the purpose of identifying subjects who have not achieved a meaningful increase in plasma acetate concentration due to experimental variability. As we administered sodium acetate by the intravenous route, we believe that the likelihood of substantial differences in plasma acetate exposure between subjects is low, and hence we omitted this measurement for practical and logistic reasons. The dose of acetate was chosen on the basis of safety, by evaluating the literature and by determining the highest reported dose of acetate administered previously. A consistent elevation of acetate plasma concentration to approximately 1.4 mmol/L was reported following the administration of 150 mmol of sodium acetate (Akanji et al., 1990).

Second, the preclinical study suggested that POMC transcription increased 30 minutes after acetate infusion. In our study, due to logistical reasons, subjects completed infusion 20–70 minutes before the scan, and the scan was acquired over 90 minutes. The time course of increases in EO following an elevation of POMC mRNA in the human brain is a matter of conjecture, and we may have missed the peak endogenous release in some or all of our subjects. Future microdialysis studies are needed to explore the b-endorphin concentration changes (Maidment et al., 1989) over time, following acetate administration. Third, order effect is a confounding factor, as our study was not counterbalanced. Previous studies have indicated that placebo may lead to alterations in the opioid system (Pecina and Zubieta, 2015; Pecina et al., 2015). Follow-up studies with larger sample sizes and controlling for variables such as order effects, diurnal variation and the potential for placebo responses will be required to test conclusively the hypothesis that acute acetate administration leads to enhanced EO levels in the human brain.

Finally, previous studies have reported [11C]carfentanil BPND test–retest variability of 10% (Hirvonen et al., 2009). The magnitude of change noted in our study is lower than this threshold. However, our results are consistent across brain regions in all study subjects.

We have demonstrated that an acute acetate challenge has the potential to increase EO release in the human brain, providing a plausible mechanism of the central effects of acetate on appetite in humans.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: O.D.H. has received investigator-initiated research funding from and/or participated in advisory/speaker meetings organised by Astra-Zeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Lyden-Delta, Servier and Roche. Neither O.D.H. nor his family have been employed by or have holdings/a financial stake in any biomedical company. A.L.-H. has received honoraria paid into her institutional funds for speaking and chairing engagements from Lundbeck, Lundbeck Institute UK and Janssen-Cilag. She has received research support from Lundbeck and has been consulted by but received no monies from Britannia Pharmaceuticals. D.N. has consulted for or received speaker’s fees or travel or grant support from the following companies with an interest in the treatment of addiction: RB pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, GSK, Pfizer, D&A Pharma, Nalpharm, Opiant Pharmaceutical and Alkermes. R.G. is a consultant for Abbvie and Cerveau. E.A.R. is a consultant for Opiant Pharmaceutical, AbbVie and Teva, and a shareholder in GSK.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This study was partly funded by grants MC-A656-5QD30 from the Medical Research Council-UK, 666 from the Maudsley Charity 094849/Z/10/Z from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and Wellcome Trust to O.D.H. and King’s College London scholarship to A.H.A. and support from Invicro. Infrastructure support was provided by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Imperial Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

ORCID iDs: Abhishekh H Ashok  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3636-7253

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3636-7253

Alessandro Colasanti  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6017-801X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6017-801X

References

- Akanji AO, Derek T, Hockaday R. (1990) Acetate tolerance and the kinetics of acetate utilization in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 51: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok AH, Myers J, Marques TR, et al. (2019) Reduced mu opioid receptor availability in schizophrenia revealed with [11C]carfentanil positron emission tomographic imaging. Nat Commun 10: 4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard FJ. (1972) Supply and utilization of acetate in mammals. Am J Clin Nutr 25: 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessesen DH, Van Gaal LF. (2018) Progress and challenges in anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6: 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JD, Chaput JP, Sjodin AM, et al. (2017) Brain on fire: incentive salience, hedonic hot spots, dopamine, obesity, and other hunger games. Annu Rev Nutr 37: 183–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MG, Morrison E. (1997) Post-translational processing of proopiomelanocortin in the pituitary and in the brain. Crit Rev Neurobiol 11: 35–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers ES, Morrison DJ, Frost G. (2015) Control of appetite and energy intake by SCFA: what are the potential underlying mechanisms? Proc Nutr Soc 74: 328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantuoni C, Schwenker J, McCarthy J, et al. (2001) Excessive sugar intake alters binding to dopamine and mu-opioid receptors in the brain. Neuroreport 12: 3549–3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti A, Searle GE, Long CJ, et al. (2012) Endogenous opioid release in the human brain reward system induced by acute amphetamine administration. Biol Psychiatry 72: 371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoto F, Zapparoli L, Bonandrini R, et al. (2018) Hungry brains: a meta-analytical review of brain activation imaging studies on food perception and appetite in obese individuals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 94: 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum J, Gramsch C, Herz A. (1983) Activation of hypothalamic beta-endorphin pools by reward induced by highly palatable food. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 18: 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost G, Sleeth ML, Sahuri-Arisoylu M, et al. (2014) The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat Commun 5: 3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn R, Coello C, Searle G. (2016) Molecular imaging and kinetic analysis toolbox (MIAKAT) – a quantitative software package for the analysis of PET neuroimaging data. J Nucl Med 57: 1928–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen J, Aalto S, Hagelberg N, et al. (2009) Measurement of central mu-opioid receptor binding in vivo with PET and [11C]carfentanil: a test–retest study in healthy subjects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36: 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DT, Sanford BJ, Meyers KK, et al. (2015) It still hurts: altered endogenous opioid activity in the brain during social rejection and acceptance in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 20: 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutsa J, Karlsson HK, Majuri J, et al. (2018) Binge eating disorder and morbid obesity are associated with lowered mu-opioid receptor availability in the brain. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 276: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson HK, Tuominen L, Tuulari JJ, et al. (2015) Obesity is associated with decreased µ-opioid but unaltered dopamine D2 receptor availability in the brain. J Neurosci 35: 3959–3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson HK, Tuulari JJ, Tuominen L, et al. (2016) Weight loss after bariatric surgery normalizes brain opioid receptors in morbid obesity. Mol Psychiatry 21: 1057–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles SE, Jarrett IG, Filsell OH, et al. (1974) Production and utilization of acetate in mammals. Biochem J 142: 401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp MJ, Hammers A, Lawrence AD, et al. (2009) Evidence for endogenous opioid release in the amygdala during positive emotion. Neuroimage 44: 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korri UM, Nuutinen H, Salaspuro M. (1985) Increased blood acetate: a new laboratory marker of alcoholism and heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 9: 468–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. (1996) Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 4: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment NT, Brumbaugh DR, Rudolph VD, et al. (1989) Microdialysis of extracellular endogenous opioid peptides from rat brain in vivo. Neuroscience 33: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q, Han Y, Ji G, Li G, et al. (2018) Disrupted topological organization of the frontal-mesolimbic network in obese patients. Brain Imaging Behav 12: 1544–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick I, Myers J, Ramos AC, et al. (2016) Blunted endogenous opioid release following an oral amphetamine challenge in pathological gamblers. Neuropsychopharmacology 41: 1742–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millington GW. (2007) The role of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurones in feeding behaviour. Nutr Metab (Lond) 4: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, et al. (2012) Alcohol consumption induces endogenous opioid release in the human orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. Sci Transl Med 4: 116ra6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrego H, Carmichael FJ, Israel Y. (1988) New insights on the mechanism of the alcohol-induced increase in portal blood flow. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 66: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina M, Zubieta JK. (2015) Molecular mechanisms of placebo responses in humans. Mol Psychiatry 20: 416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina M, Bohnert AS, Sikora M, et al. (2015) Association between placebo-activated neural systems and antidepressant responses: neurochemistry of placebo effects in major depression. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 1087–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossin AR, Koch AE, Campbell PL, et al. (2016) Acute experimental changes in mood state regulate immune function in relation to central opioid neurotransmission: a model of human CNS-peripheral inflammatory interaction. Mol Psychiatry 21: 243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. (1998) The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 22–33; quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda C, Santoro A, Kim JD, et al. (2017) POMC neurons: from birth to death. Annu Rev Physiol 79: 209–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turton S, Myers JF, Mick I, et al. (2018) Blunted endogenous opioid release following an oral dexamphetamine challenge in abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Mol Psychiatry 25: 1749–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuulari JJ, Tuominen L, De Boer FE, et al. (2017) Feeding releases endogenous opioids in humans. J Neurosci 37: 8284–8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, et al. (2011) Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage 54: 264–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. (2012) Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 11: 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Kim SW, Wang GJ, et al. (2013) Acute alcohol intoxication decreases glucose metabolism but increases acetate uptake in the human brain. Neuroimage 64: 277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wise RA, Baler R. (2017) The dopamine motive system: implications for drug and food addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 18: 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright H, Li X, Fallon NB, et al. (2016) Differential effects of hunger and satiety on insular cortex and hypothalamic functional connectivity. Eur J Neurosci 43: 1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JN, Wang JJ. (2008) The cerebellum in feeding control: possible function and mechanism. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 28: 469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]