Abstract

Biofilm formation in the human intestinal pathogen Vibrio cholerae is in part regulated by norspermidine, spermidine and spermine. V. cholerae senses these polyamines through a signalling pathway consisting of the periplasmic protein, NspS, and the integral membrane c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase MbaA. NspS and MbaA belong to a proposed class of novel signalling systems composed of periplasmic ligand-binding proteins and membrane-bound c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases containing both GGDEF and EAL domains. In this signal transduction pathway, NspS is hypothesized to interact with MbaA in the periplasm to regulate its phosphodiesterase activity. Polyamine binding to NspS likely alters this interaction, leading to the activation or inhibition of biofilm formation depending on the polyamine. The purpose of this study was to determine the amino acids important for NspS function. We performed random mutagenesis of the nspS gene, identified mutant clones deficient in biofilm formation, determined their responsiveness to norspermidine and mapped the location of these residues onto NspS homology models. Single mutants clustered on two lobes of the NspS model, but the majority were found on a single lobe that appeared to be more mobile upon norspermidine binding. We also identified residues in the putative ligand-binding site that may be important for norspermidine binding and interactions with MbaA. Ultimately, our results provide new insights into this novel signalling pathway in V. cholerae and highlight differences between periplasmic binding proteins involved in transport versus signal transduction.

Keywords: polyamine, norspermidine, Vibrio cholerae, biofilm, homology modelling

Introduction

The human intestinal disease cholera affects millions of people worldwide and is responsible for thousands of deaths per year [1]. The causative agent of cholera is the Gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae , which resides as a natural inhabitant in many aquatic ecosystems, including lakes, rivers and oceans [2, 3]. During intestinal colonization, this bacterium produces two main virulence factors: toxin co-regulated pilus (TCP) and cholera toxin (CT) [4]. TCP is a pilus that is required for the colonization of the small intestine and CT is an AB5-subunit toxin in the ADP-ribosyltransferase family that is responsible for the profuse watery diarrhoea that is the hallmark of cholera [4–6]. V. cholerae can exist in two distinct states that are important for its life cycle: a free-swimming state called the planktonic state or a sessile state associated with biofilm formation [7–9]. V. cholerae is thought to exist primarily as a biofilm in aquatic environments. It is ingested in part as a biofilm by humans, which increases its survival in the acidic conditions of the stomach. Once the bacteria reach the small intestine, they must disperse from the biofilm and return to the planktonic state in order to induce expression of virulence factors and cause disease [10–12].

The transition between the planktonic and biofilm states is regulated at the molecular level by the secondary messenger bis-(3′−5′) cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) [13]. c-di-GMP regulates the expression of genes involved in the biosynthesis of vibrio polysaccharide and other components critical for biofilm matrix construction [13]. c-di-GMP is synthesized from two molecules of GTP by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) that contain a GGDEF domain. It is broken down into either 5′-phosphoguanylyl-3,5′-guanosine (5′pGpG) or two molecules of GMP by a phosphodiesterase (PDE), containing EAL or HD-GYP domains, respectively [14]. These domains are named after the conserved amino acid sequences, GGDEF or EAL/HD-GYP, which are required for the diguanylate or phosphodiesterase activities in these enzymes. High levels of c-di-GMP in the cell lead to increased biofilm formation, whereas low levels promote a motile, planktonic lifestyle for V. cholerae [13–16].

DGCs and PDEs detect environmental signals either directly through their sensory domains or indirectly through interactions with other signalling proteins. Environmental signals can then regulate the activity of the enzymatic domains [17]. In V. cholerae, these signals can be polyamines, which are linear aliphatic carbon chains containing multiple amine groups that are positively charged at physiological pH. Polyamines are synthesized by most organisms and are important for growth and other cellular processes including but not limited to: protein synthesis and function, siderophore production and biofilm formation ([18–21]). The polyamine norspermidine enhances V. cholerae biofilm formation, whereas spermidine and spermine both inhibit it [22–25]. Norspermidine is less prevalent than other polyamines in many bacteria; however, it has been found in many species of Vibrionaceae , thermophilic bacteria, eukaryotic algae, white shrimp and arthropods [26–30]. On the other hand, spermidine and spermine are two of the most abundant polyamines present in the human intestine due to diet, synthesis by intestinal cells or gut microbiota [31–33].

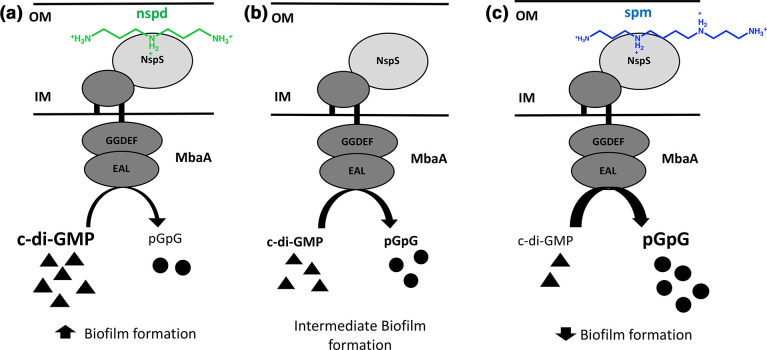

V. cholerae uses the NspS/MbaA signalling system to detect these polyamines, which may enable it to differentiate between the natural aquatic environment and the human intestine based on the presence of specific polyamines. NspS is a periplasmic protein that binds spermine, spermidine and norspermidine [22–25]. MbaA is a transmembrane protein with a large periplasmic domain and tandem cytoplasmic GGDEF and EAL domains [24, 34]. We have previously shown that MbaA is a c-di-GMP specific phosphodiesterase; however, the role of the degenerate GGDEF domain (SGDEF) is currently not known [24]. Deletion of either nspS or mbaA abrogates the effects of these polyamines on biofilm formation [22–25]. More specifically, deletion of mbaA results in enhanced biofilm formation, whereas deletion of nspS results in an inhibition of biofilm formation. Thus, NspS and MbaA have opposing effects on V. cholerae biofilms [22]. Additionally, the nspS and mbaA genes reside in an operon and are co-transcribed [24]. These findings have led to the current model for this signalling pathway where NspS interacts with the periplasmic domain of MbaA to inhibit its PDE activity. This leads to an increase in c-di-GMP, promoting biofilm formation (Fig. 1) [22, 24]. When NspS binds norspermidine, there is a greater inhibition of the PDE activity of MbaA, leading to enhanced biofilm formation, presumably through increased levels of c-di-GMP [22, 24]. In contrast, when NspS binds spermidine or spermine, MbaA PDE activity is no longer inhibited and results in lower c-di-GMP levels and a decrease in biofilm formation [23–25].

Fig. 1.

Model of NspS-MbaA signalling pathway. (a) When NspS is bound by norspermidine, the PDE activity of MbaA is inhibited, leading to accumulation of c-di-GMP and increased biofilm formation. (b) Intermediate state of interaction in which NspS interacts with the periplasmic domain of MbaA to inhibit the PDE activity of MbaA, leading to intermediate levels of c-di-GMP and biofilm formation. (c) When NspS is bound by spermine (or spermidine), the inhibition of the PDE activity of MbaA is relieved, resulting in enhanced c-di-GMP degradation and low biofilm formation. Black triangles represent c-di-GMP and black circles represent 5’pGpG. Nspd and spm stand for norspermidine and spermine, respectively. The structure of norspermidine is shown in green and the structure of spermine is in blue. OM stands for outer membrane and IM for inner membrane.

NspS belongs to a large class of proteins called the periplasmic ligand-binding proteins. The majority of the periplasmic ligand-binding proteins characterized to date are components of ABC-type transporters [35] in which the role of the periplasmic protein is to bind its specific ligand and facilitate its transport into the cell. A well-characterized example is the PotD protein in Escherichia coli . PotD is the periplasmic ligand-binding protein of the PotABCD ABC-type transporter responsible for importing the polyamines spermidine and putrescine into the cell [36]. NspS, however, is a ligand-binding protein that is not involved in transport, but instead plays a role in signal transduction [24]. Previously, we identified a number of Proteobacteria whose genomes harbour nspS- and mbaA-like genes that are adjacent to each other and are likely to be co-transcribed [24]. The nspS-like genes in these bacteria encode periplasmic ligand-binding proteins predicted to detect a variety of small molecules including polyamines, phosphate, nitrate and anions. The mbaA-like genes encode integral membrane proteins with tandem GGDEF and EAL domains. We proposed that NspS and MbaA belong to a new class of signalling systems made up of periplasmic ligand-binding proteins (NspS-like sensors) and integral membrane proteins with tandem GGDEF and EAL domains (MbaA-like transducers) that work together to regulate cellular behaviour through the secondary messenger c-di-GMP. To our knowledge, most of these NspS-like sensors and MbaA-like transducers remain uncharacterized. Because the predicted function of these proteins is signal transduction, we refer to these proteins here as functional homologues of NspS. On the other hand, we refer to NspS homologues that are components of ABC-type transporters as structural homologues.

To provide insight into this new class of signalling systems, we designed a study to identify the residues of NspS that are important in enhancing biofilm formation. We performed random mutagenesis on nspS, screened mutants for biofilm formation and mapped these mutations to a 3D homology model of NspS. Interestingly, the majority of the residues we identified clustered on two main regions of the NspS protein surface that are likely important for protein–protein interactions. We also identified residues that may be important for norspermidine binding to NspS and compared these residues to those present in structural and functional homologues. Our results further characterize NspS and provide a foundation for studies on NspS homologues in other Proteobacteria.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The V. cholerae strains in this study were derived from V. cholerae O139 MO10, a clinical isolate from India, SmR [37]. The primary strain of V. cholerae utilized in this study was PW514, a derivative of MO10 with chromosomal vpsLp-lacZ fusion and a chromosomal deletion of nspS [22]. V. cholerae strains were grown at 27 °C and E. coli (DH5α) strains were grown at 37 °C. All strains were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth. Where appropriate, streptomycin was used at 100 μg ml−1; tetracycline was used at 10 μg ml−1 for E. coli strains and at 2.5 μg ml−1 for V. cholerae strains. Primers were synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon or Sigma and DNA sequencing was performed by Eurofins MWG Operon.

Error-prone PCR

Error-prone PCR was performed on purified pNP1 plasmid (pACYC184::nspS-V5) [25], using the GeneMorph II random mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). In this construct, the nspS gene is cloned downstream of the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene promoter and is expressed constitutively. A V5 affinity tag was also engineered onto the end of the nspS gene when it was cloned into the pACYC184 plasmid. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, 1 µg of target DNA was amplified for 30 cycles to achieve an approximate mutational frequency of 0–4.5 mutation(s) per kilo basepair. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

nspS mutant library generation

Gel-purified products from the error-prone PCR reaction and purified pACYC184 plasmid were digested with restriction enzymes NcoI and EcoRI. The PCR products were ligated into pACYC184 using ElectroLigase following the manufacturer’s recommendations (New England Biolabs). After ligation, the plasmid products were transformed into E. coli DH5α to generate a trial library. For the trial library, successful transformation was confirmed by PCR, plasmids were isolated from a small subset of clones, and sequenced using the forward primer P291 (5′ GCATGATGAACCTGAATCGC), which anneals upstream of the NcoI site used, and the reverse primer P292

(5′ GCCTTTATTCACATTCTTGCC), which anneals downstream of the EcoRI digest site used for cloning into pACYC184. The sequencing results showed that the error-prone PCR was successful in introducing random mutations in the nspS sequence. To generate the final mutant library, the ligated pACYC184::mutant-nspS-V5 plasmid was transformed again into DH5α. An average number of colonies per plate post-transformation was determined and used to estimate the number of clones in the final mutant library. To purify the plasmids from the mutant clones, 1 ml of LB was added to each agar plate to resuspend the colonies. The LB was combined from all plates and a midi prep was performed (Promega). This process was performed twice to yield the final nspS mutant library used in this study.

Screening for biofilm-deficient mutants

LB media was used for all biofilm assays with appropriate antibiotics. Following transformation of the final nspS mutant library into a ΔnspS strain of V. cholerae, individual colonies were inoculated into a 96-deep-well plate and grown overnight with shaking. The overnight culture was diluted 1 : 50 in fresh media in a new 96-deep-well plate and was grown at 27 °C with shaking to mid-log phase. Each well was diluted to an OD655 of 0.04 in 125 µl in 96-well microtitre plates and grown statically at 27 °C for approximately 24 h. Biofilm formation was assessed using a modified version of a crystal-violet biofilm staining protocol described previously [38]. Briefly, planktonic cells were removed and the remaining biofilm washed with 1×PBS. A 1 % crystal-violet solution was used to stain the biofilm for 25 min followed by removal and two consecutive 1×PBS wash steps. The microtitre plates were dried and each well was solubilized in 135 µl of 95 % ethanol for approximately 10 min. The absorbance of 125 µl from each well was analysed at a wavelength of 595 nm. After the initial transformation of the nspS mutant library, biofilm formation was analysed in triplicate for each mutant clone. Based on these results, mutant clones that were different from the positive control, V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184::nspS, were analysed again for biofilm formation using the same protocol described above. For the second biofilm formation, three biological replicates were assessed with three technical replicates for each.

Western-blot analysis

Following overnight growth at 27 °C with shaking, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 250–300 µl 1×PBS, sonicated three times for 10 s each using a Branson SFX150 Sonifier and centrifuged at 16 000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was combined with 2× Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and incubated at 65 °C for 5 min. Each sample was run on a polyacrylamide gel for one to 1.5 h at 240 V. The gel was transferred onto a PVDF membrane using a BIO-RAD Mini Trans Blot for between 45–70 min. After the transfer, the membrane was blocked for either 1 h at room temperature or 4 h at 4 °C in 5 % (w/v) non-fat dry milk in 1×PBS-T [0.05 % (v/v) Tween 20 solution in 1×PBS] and washed three times for 5 min with 1×PBS-T. The membrane was then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-V5 Tag antibody and a Precision Protein StrepTactin-HRP Conjugate antibody at 1 : 5000 and 1 : 10 000 dilution, respectively (BIO-RAD). The anti-V5 antibody was utilized to react with the V5 tag that was engineered into the nspS sequence when it was cloned into pACYC184. The membrane was washed three times for 5 min with 1×PBS-T and was then incubated with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) for 5 min. The membrane was imaged with a BIO-RAD Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR System.

Optical-density biofilm assay

Overnight cultures were diluted 1 : 50 into 2 ml of fresh LB media with antibiotics and grown to mid-log phase while shaking at 27 °C. Strains were diluted to an OD655 of 0.04 in 0.3 ml LB with antibiotics in borosilicate test tubes in the absence or presence of norspermidine (100 µM). These tubes were incubated statically at 27 °C for 24 h. After incubation, planktonic cells were removed and the remaining biofilm was washed with 0.3 ml 1×PBS. The biofilm was homogenized by vortexing for 30 s with 1.0 mm glass beads (BioSpec) in 0.3 ml 1×PBS. The cell density of the homogenized biofilm was measured using an iMark Microplate Reader (BIO-RAD) at 655 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated for reproducibility with the exception of biofilm assays analysing response to norspermidine addition for five mutants, namely F64L, N68I, P83L, R242L, L281F. Restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic prevented testing of the third biological replicate; however, the first two replicates showed a clear and definitive response to norspermidine, leading to the conclusion that these mutants are responsive. Due to the number of strains to analyse, the biofilm assays conducted in the absence and presence of norspermidine had to be performed in multiple sets. Three biological replicates of data for each of the positive and negative controls were randomly selected to be used for graphical representation and analysis.

Sequencing and analysis

Plasmids were isolated from mutant clones of interest and sent for sequencing with the forward primer P291 and the reverse primer P292. Primers P37

(5′ CGTTTTGGCTAACGTCTCCGCG) and P39 (5′ GGTATGCTTAAAGCCAGTGTCG) were utilized when necessary for additional sequencing. These primers anneal to nucleotides 261–282 and nucleotides 496–517 of the nspS gene, respectively. The sequencing results were analysed for changes from the wild-type sequence using Vector NTI (Thermo Scientific) to determine the mutated amino acids.

Homology modelling

V. cholerae NspS sequence data was obtained from Uniprot (Uniprot ID: Q9KU25) and homology models of NspS were generated using the Swiss model server [39]. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa polyamine transport protein PotD homologue SpuE crystal structures were used as templates for the open (PDB ID: 3TTL) and closed (PDB ID: 3TTN) conformations of NspS [36, 40]. SpuE was selected as the template structure for NspS homology models because it had the highest sequence identity among crystal structures of homologues to NspS and structures of both open (no ligand) and closed (spermidine bound) conformations had been determined. The signal peptide of NspS was not observed in the homology model.

We also generated homology models for previously identified [24] functional homologues (UniProt IDs: A8FVY0, A4VGH6, Q92RK9, A1SUA3 and Q2S7Q6) based on the SpuE crystal structure in the closed conformation (PDB ID: 3TTN) using similar methods. Full sequences were analysed using the webserver SignalP-5.0 (41; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-5.0) to determine cutoff values for signal peptide sequences. The server identified signal peptides for all proteins except the A1SUA3 protein. Truncated sequences for A8FVY0 (−33), A4VGH6 (−31), Q92RK9 (−22) and Q2S7Q6 (−31) and the full sequence for A1SUA3 were submitted to the Swiss model to generate homology models. Promals3D (42; http://prodata.swmed.edu/promals3d/promals3d.php) as then used to generate a multiple sequence alignment and calculate the % sequence identity of the NspS protein with other functional homologues based on the homology models (Table S1, available in the online version of this article). This webserver was also used to calculate % sequence identity between NspS and the structural homologues (PDB IDs: 1A99, 3TTN, 3TTM, 1POT, 4GL0 and 2V84) (Table S1).

Docking

Autodock 4.2.6 and Autodock Tools 4.2.6 [43] were used to dock norspermidine into the modelled closed structure of NspS. The coordinates of norspermidine were obtained from the Protein Data Bank through Ligand-Expo (http://ligand-expo.rcsb.org/reports/N/NSD/index.html). The ligand was prepared as a .pdbqt file using Autodock Tools. A charged version of the closed model (Gasteiger charges) with polar hydrogens was prepared with Autodock Tools. A search space was specified based on the location of ligand in homologous crystal structures and concentration of negative charge in the homology model [44] AutoGrid 4.2.6 was used to prepare the grid file and Autodock 4.2.6 was then used to run the docking programme. Autodock’s Genetic Algorithm (GA) was used to perform 25 GA runs and all other parameters were set to default. Data output was in Lamarckian (4.2). An initial docking was performed to help locate the position of the ligand in reference to specific residues and then a Flexible Residues docking was performed. The following residues were allowed to sample new conformations: W41, N68, D70, D90, F131, Y233, D236 and D263. These residues were chosen based on their proximity to norspermidine docked in the initial model as well as their presence in the central binding tunnel of the structure. Results of the docking were initially viewed and evaluated within Autodock Tools and then were exported as .pdb files for further analysis.

Results and discussion

Construction and screening of the nspS mutant library

To introduce random mutations, the wild-type nspS gene was subjected to error-prone PCR. The PCR products were cloned into the plasmid pACYC184 and transformed into E. coli . Based on a small subset of mutant clones that were sequenced, the mutation rate was determined to be approximately 50 % and the missense mutation rate was estimated to be approximately 30 % (data not shown). Subsequent rounds of transformation yielded a final mutant library of approximately 20 000 clones.

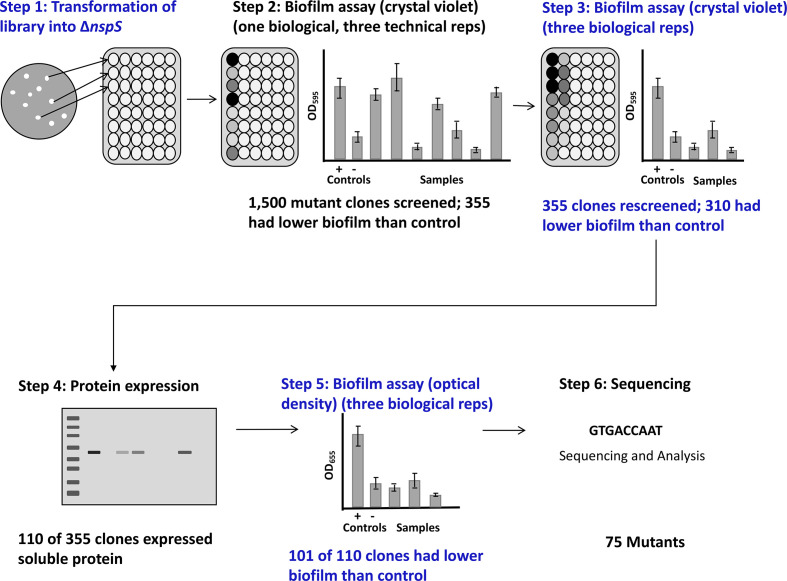

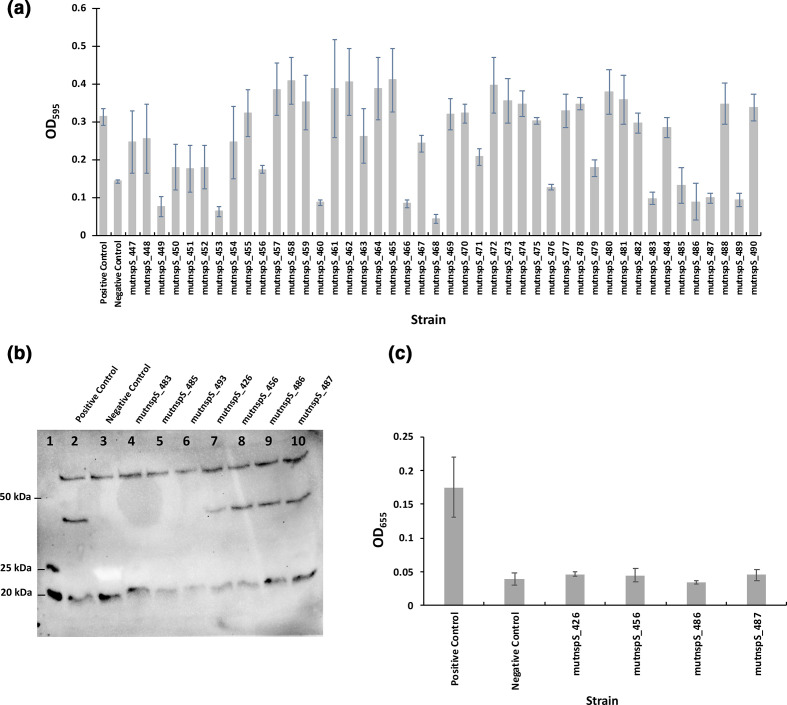

V. cholerae mutants lacking the nspS gene form low amounts of biofilm [22]. Thus, mutations in NspS residues that are important for its function in upregulating biofilm formation should also lead to low biofilms. We developed a high-throughput screening method (Fig. 2) based on this premise. Briefly, we transformed the nspS mutant library into a V. cholerae ΔnspS strain (step 1) and analysed biofilm formation (step 2). In total, 1500 mutant clones were screened for biofilm formation with an initial biofilm assay using crystal-violet staining. The data from the initial biofilm assay for a subset of 44 mutant clones is shown in Fig. 3a. Of these 1500 mutant clones, 355 exhibited lower biofilm levels than the positive control, V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184::nspS. These 355 clones were analysed again for biofilm formation (Fig. 2, step 3). We confirmed that 310 of these mutant clones had a low biofilm phenotype; these were further analysed for NspS protein expression using Western blotting (step 4). Of the 310 clones, 110 expressed soluble NspS protein and were used for further screening. A representative Western blot for seven mutant clones is shown in Fig. 3b. Any mutant clones for which protein expression could not be detected on a Western blot were assumed to either have mutations that prevented proper folding and, therefore, did not result in stable protein or had mutations that resulted in truncated proteins through the introduction of premature stop codons. In either case, these mutants were not investigated further.

Fig. 2.

Mutant clone screening process. The nspS mutant library was transformed into the V. cholerae ∆nspS strain and colonies were individually grown in separate wells of a 96-well deep-well plate (step 1). For each mutant clone, crystal-violet staining was performed to assess biofilm formation for one biological replicate (step 2). Biofilm formation using crystal-violet stain was used again to assess three biological replicates for mutant clones with low biofilm formation in the initial assay (step 3). Mutant clones that produced low biofilms were analysed via Western blot for protein expression (step 4). For clones that had protein expression, a final biofilm assay was performed that measured the optical density of the biofilm to confirm the low biofilm phenotype (step 5). Plasmids from mutant clones that had low biofilm formation and protein expression that was detected via Western blot were purified and sent for sequencing (step 6).

Fig. 3.

(a) Initial analysis of biofilm formation. Crystal-violet staining was used to analyse biofilm formation for each mutant clone. This graph shows a subset of 44 mutant clones. The positive control is V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184::nspS-V5 and the negative control is V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184. Three positive and three negative controls were used with each plate; the averages of these values are shown on the graph. The error bars represent standard deviations of three technical replicates. (b, c) Analysis of NspS protein expression and tertiary screen of biofilm formation. (b) Example Western-blot analysis with a ladder in lane 1 and positive and negative controls respectively in lanes 2 and 3. The positive control is V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184::nspS-V5 and the negative control is V. cholerae ΔnspS with pACYC184. Lanes 4–10, seven mutant clones identified from two crystal-violet biofilm assays as having low biofilm formation. This image was taken with a BIO-RAD Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR System and manually exposed for 2 min. (c) Graph of biofilm formation for the four mutant clones from (b) that showed NspS protein expression. Three biological replicates were analysed in triplicate per mutant clone for biofilm formation. The positive and negative controls are the same as in (a). Error bars show standard deviations of three biological replicates. Only clones that showed protein expression in the Western blot were further tested for biofilm formation, e.g. mutnspS_426, mutnspS_456, mutnspS_486 and mutnspS_487 from (b).

Mutant clones that showed soluble NspS protein expression were analysed for biofilm formation using an optical-density biofilm assay (Fig. 2, step 5 and Fig. 3c). The data for four of the 110 mutant clones for the optical-density biofilm assay are shown in Fig. 3c. Of the 110 mutant clones that produced soluble NspS protein, 101 of them were confirmed to be defective in biofilm formation. The nspS gene from these clones were sequenced to determine the identity of the mutations (Fig. 2, step 6). A total of 75 of these 101 clones were successfully sequenced and had mutations.

Amino acids identified in the mutant clone screen

Of the 1500 mutant clones initially screened, we identified 75 mutant clones with low levels of biofilm formation and soluble NspS production. Of these, 43 clones had one missense mutation in the nspS gene (Table 1), 26 had two, five had three, and one had four (Table 2). While our screen was not saturated, the number of new hits with single-missense mutations started to plateau (Fig. S1); therefore, it is likely that we identified most of the amino acids important for NspS function. Some of these clones were replicates of the same amino acid change (e.g. phenylalanine at position 243 was mutated twice, both times to a valine), but others caused multiple changes at the same position (e.g. arginine at position 219 was mutated to a cysteine, histidine or serine). Interestingly, some of the amino acids that were mutated in single-mutant clones also appeared in clones with multiple missense mutations. For example, L40, N68, S79, L82, F84, S216, R219, D263 and N268 mutants all occurred in a clone with a double-missense mutation, S79 and S216 occurred in clones with triple-missense mutations, and P83 occurred in the clone with the quadruple-missense mutation (Table 2).

Table 1.

Single-missense mutations identified in sequenced clones

|

Mutant clone |

Mutation |

Mutant clone |

Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mut430 |

S32N |

mut148 |

S216I |

|

mut585 |

L40H |

mut221 |

S216R |

|

mut1327 |

L40P |

mut264 |

S216N |

|

mut1095 |

L40R |

mut273 |

S216R |

|

mut1255 |

D43N |

mut1084 |

S216N |

|

mut934 |

D43N |

mut1261 |

V218A |

|

mut1233 |

F64L |

mut456 |

V218L |

|

mut1147 |

F66V |

mut85 |

R219S |

|

mut1371 |

F66Y |

mut205 |

R219C |

|

mut724 |

N68I |

mut387 |

R219H |

|

mut921 |

S79G |

mut732 |

R219H |

|

mut261 |

S79G |

mut1047 |

R219C |

|

mut580 |

S79C |

mut797 |

R242L |

|

mut1239 |

S79C |

mut415 |

F243V |

|

mut675 |

L82R |

mut963 |

F243V |

|

mut684 |

L82R |

mut426 |

D263V |

|

mut853 |

L82P |

mut568 |

D263V |

|

mut573 |

P83L |

mut255 |

N268D |

|

mut69 |

F84V |

mut260 |

N268D |

|

mut1155 |

F84V |

mut1089 |

N268S |

|

mut605 |

L89W |

mut1390 |

L281F |

|

mut686 |

L89W |

|

|

Table 2.

Multiple-missense mutations identified in sequenced clones and assessment of location in the 3D homology model compared to single-missense mutants. Sites of single-missense mutant clones are displayed in bold and residues in the putative ligand-binding site that interact with docked norspermidine (nspd) are shown in blue. Short descriptions of the location of each residue in 3D in the double and triple mutants is separated by slashes. ‘Site’ signifies amino acid position. Note: S79N, S79R, L82V, S216G, S216N, R219L, D263N, D263E and N268I are not identical mutations found in single-missense mutants, but are representatives of the same ‘sites’

|

Mutant clone |

Mutations |

Location in the 3D model |

|---|---|---|

|

mut3 |

L75F, S171N |

On two separate helices on two lobes; same surface as single mutants |

|

mut25 |

W8R, Y213N |

Signal peptide – excluded/on loop; same surface as single mutants |

|

mut212 |

N62I, D263N |

On beta-strand; same surface as single mutants/includes single-mutation-site residue that interacts with docked nspd in the closed model |

|

mut233 |

S79G, S216G |

Includes single mutation sites |

|

mut246 |

S79G, S216G |

Includes single mutation sites |

|

mut320 |

V80I, D263E |

On loop; same surface as single mutation site/includes single-mutation-site residue that interacts with docked nspd in the closed model |

|

mut453 |

P117H, S216N |

On helix near hinge region; different location from single mutants/includes single mutation site |

|

mut468 |

S79G, S216G |

Includes single mutation sites |

|

mut486 |

F84V, T149A |

Includes single mutation site/on mobile loop in back of bottom lobe; different location from single mutants |

|

mut558 |

R219C, D236V |

Includes single mutation site/residue that interacts with docked nspd in the closed model |

|

mut629 |

D69V, R219L |

On loop near N68 that moves upon transition from opened to closed conformations/includes single mutation site |

|

mut652 |

N68I, A94T |

Includes single-mutation-site residue in nspd ligand - binding site/on helix at different location from single mutants |

|

mut693 |

N68I, A94T |

Includes single-mutation-site residue in nspd ligand - binding site/on helix at different location from single mutants |

|

mut707 |

S79N, L182H |

Includes single mutation site/on helix at different location from single mutants |

|

mut719 |

M14K, S79G |

Signal peptide-excluded/includes single mutation site |

|

mut731 |

L82V, A108S |

Includes single mutation site/on mobile loop in different location from single mutants |

|

mut844 |

P117H, S216N |

On helix near hinge region; different location from single mutants/includes single mutation site |

|

mut867 |

S79R, N268I |

Includes single mutation sites |

|

mut907 |

H126Y, S216N |

On mobile loop in different location from single mutants/includes single mutation site |

|

mut1202 |

A33D, N115K |

Signal peptide-excluded/on loop near hinge; different location from single mutants |

|

mut1222 |

A33D, N115K |

Signal peptide-excluded/on loop near hinge; different location from single mutants |

|

mut1294 |

S79N, P117S |

Includes single mutation site/on loop near hinge; different location from single mutants |

|

mut1355 |

R112P, D236E |

On mobile loop near hinge region; different location from single mutants/residue that interacts with docked nspd in closed model |

|

mut1384 |

D67N, L341H |

On loop near N68 that moves upon transition from opened to closed conformations/on helix at different location from single mutants |

|

mut1459 |

T174R, A204S |

On helices on one lobe at different locations from single mutants |

|

mut1474 |

L40R, E329V |

Includes single mutation site/on helix near hinge region; different location from single mutants |

|

mut118 |

D170Y, N183H, F283I |

Close to ligand-binding site in closed conformation/on mobile loop near hinge region; different location from single mutants/on same helix as L281 single mutant |

|

mut1104 |

R112H, P177H, L343H |

On mobile loop near hinge region; different location from single mutants/on helices; different location from single mutants |

|

mut1279 |

S79G, I187N, S337L |

Includes single mutation site/on mobile loop near hinge region; different location from single mutants/at end of helix at different location from single mutants |

|

mut1308 |

S216G, K286I, E295V |

Includes single mutation site/on backside of loop and helix away from single mutant sites |

|

mut1423 |

E42G, V102I, E173K |

On loop with D43 single mutant/on loop away from single mutants/residue that interacts with docked nspd in closed model |

|

mut294 |

P83H, K146E, S220N, P311L |

Includes single mutation site/on mobile loop in back; different location from single mutations/on same helix as R219 single mutant/on backside of loop and helix away from single mutant sites |

Next, we mapped the locations of these mutants on the linear NspS sequence to determine if there was a pattern to their distribution (Fig. 4). Three positions in the signal peptide were altered across five different missense mutants: one single-missense mutant and four double-missense mutants (Tables 1 and 2). The alteration of the signal peptide most likely led to an inability of these NspS mutants to move to the periplasm, so they were excluded from further analyses. Interestingly, the single-missense mutations were not randomly located throughout the protein sequence. Instead, they were found in two main regions: between residues 40–89 and 216–281 (Fig. 4). On the other hand, some multiple-missense mutations were located in between or downstream of these two main regions. Regardless, the overwhelming majority of the clones with multiple mutations (69%) contained sites found in single-missense mutants. Exceptions included seven double-missense mutants three of which had mutations in the signal peptide without a single-missense site and three triple-missense mutations. The quadruple-missense mutant had at least one site represented by a single mutant (Table 2, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

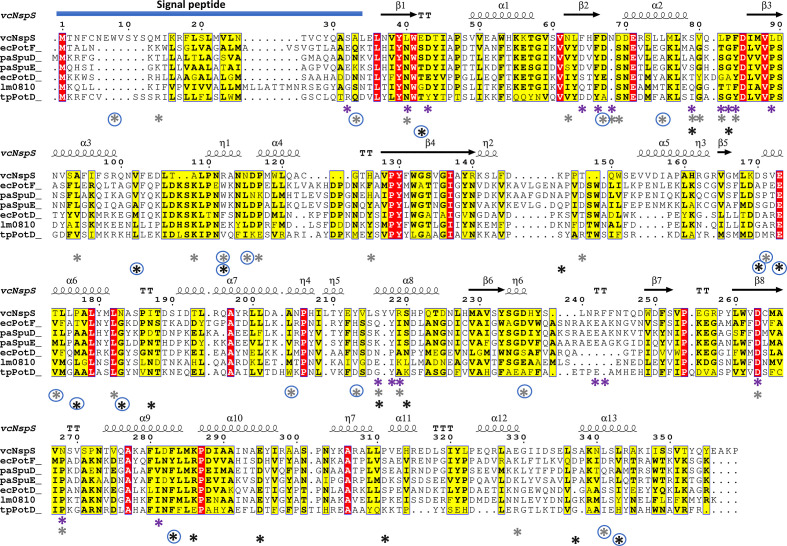

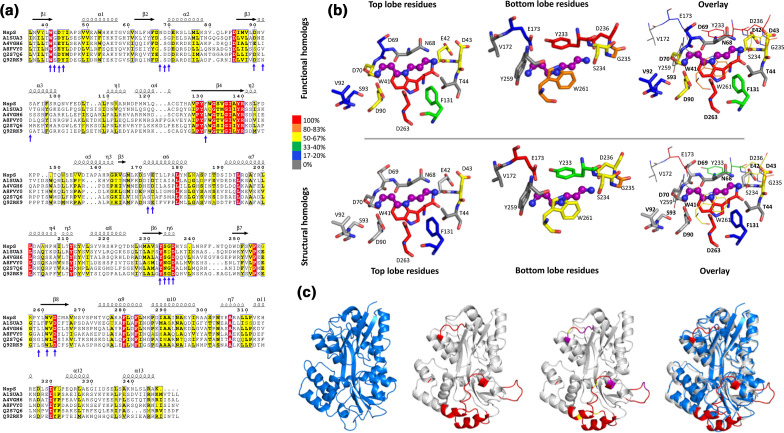

Multiple sequence alignment of NspS from V. cholerae and homologues. NspS homologues with 3D crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank were selected and the secondary structure at the top of the alignment is based on the closed conformation NspS homology model. Sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega and the figure was produced using ESPRIPT. Red highlighted residues are completely conserved and yellow residues share some sequence similarity. The following structures were used for the alignment: ecPotF (putrescine receptor from E. coli ; PDB ID: 1A99), paSpuD (polyamine receptor from P. aeruginosa ; PDB ID: 3TTM), paSpuE (polyamine receptor from P. aeruginosa ; PDB ID: 3TTN), ecPotD (spermidine/putrescine transporter from E. coli ; PDB ID: 1POT), lm0810 (spermidine/putrescine transporter from Listeria monocytogenes ; PDB ID: 4GL0), tpPotD (putrescine/spermidine transporter from Trepomena pallidum; PDB ID: 2V84). The signal peptide region of the sequence is indicated with a blue bar at the N-terminus of the protein sequences. Coloured asterisks below the sequence alignment indicate missense mutation locations. Purple asterisks identify residues changed for single-missense mutations, grey asterisks are for double-missense mutations, and black asterisks indicate triple- and quadruple-missense mutations. Blue circles surrounding asterisks indicate residues mutated in multiple-missense clones that do not contain sites of single-missense mutants.

Since some mutations found in multiple-missense mutants were not represented by any of the single-missense mutations, it would be too complex to determine if the effect on biofilm formation observed was due to a specific single mutation or the contribution of multiple mutations. Therefore, we focused the remainder of our experiments and analyses on the clones with single-missense mutations in nspS. Of the single-missense mutations that were identified by the screen (excluding the signal peptide mutant), 18 were located in unique positions of the NspS protein sequence (Fig. 4) and 13 of these amino acids were changed in more than one mutant clone (Table 1). Eight of the 18 positions had multiple amino acid changes at these sites. To determine where these residues could potentially be located in 3D space, we built a homology model of the NspS protein since its structure has not yet been determined.

Homology models of NspS open and closed forms

NspS is a member of the large family of periplasmic ligand-binding proteins, which have a conserved protein fold. Their structures contain a top and bottom lobe separated by a deep crevice in between the lobes where various ligands bind [35]. In the absence of a ligand, the two lobes remain apart from each other in a structure designated as the ‘open’ form. Ligand binding stabilizes a structure where the two lobes close in on the ligand and is designated as the ‘closed’ form. We created two homology models of the NspS protein: one in the open form and one in the closed form (Fig. 5a, b). Our homology model of the NspS structure in the open form was generated based on the apo (open) form of the NspS homologue P. aeruginosa SpuE crystal structure (PDB ID 3TTL) and the closed form was based on the ligand-bound (closed) form of the SpuE crystal structure (PDB ID 3TTN). SpuE is a periplasmic binding protein that binds spermidine and is also a homologue of the well-studied E. coli PotD protein [36]. A multiple sequence alignment of NspS, SpuE and several other periplasmic polyamine-binding protein structural homologues is shown in Fig. 4. Except for NspS, all of the proteins shown in this alignment are ligand-binding components of ABC-type transporters.

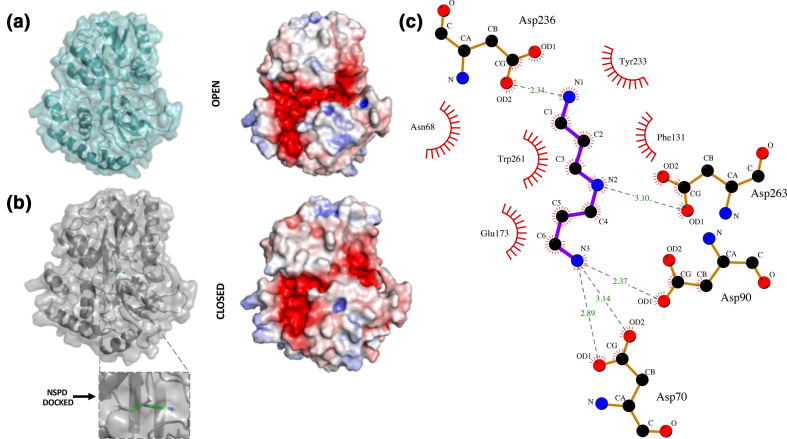

Fig. 5.

Homology models of NspS in open and closed form with docked norspermidine. (a) Homology model of the NspS open conformation with ribbon and transparent surface is shown in teal. The electrostatic surface representation of the open conformation was calculated in Pymol. Red shows negatively charged regions, blue are positive and white is neutral. (b) Homology model of the NspS closed conformation with ribbon and transparent surface in grey. Norspermidine (green sticks) is docked into the model. The electrostatic surface representation of the closed conformation is shown with same colouring as (a). (c) LigPlot representation of norspermidine docked to the closed conformation of the NspS homology model. H-bonding interactions between norspermidine (blue sticks) and residues D70, D90, D236 and D263 are shown with dashed grey lines. Length of H-bonds are shown with green numbers. Residues that form hydrophobic interactions with norspermidine are shown with red eyelashes. Figures were created using Pymol and LigPlot.

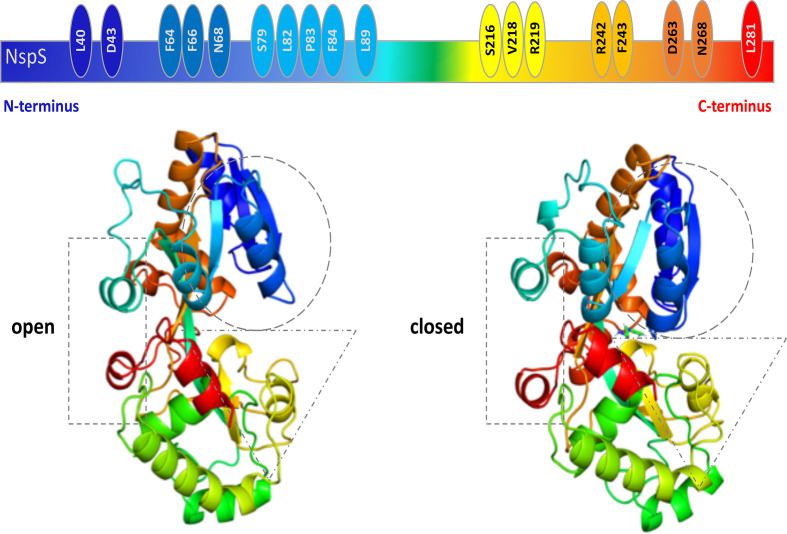

The NspS homology model exhibits the conserved structure of periplasmic ligand-binding proteins, including two lobes separated by a deep crevice lined with acidic residues that could accommodate positively charged polyamine ligands (Fig. 5). To visualize the structural changes that occur between the two conformations (open and closed) and the location of the single-missense mutations on the NspS models, we generated ribbon and surface representations of both forms and coloured them in a rainbow format from N- to C-termini (blue to red; Fig. 6). Based on the generated models, we observed relatively minor movements in three main regions of the NspS protein upon transition from open to closed forms (represented by dashed rectangle, circle and triangle; Fig. 6). Two of these regions (circle and triangle) contained single-missense mutations identified using random mutagenesis. The movement observed in the third region of the protein (rectangle) is likely due to conformational changes of the other two regions.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of conformational changes between open and closed NspS homology models and location of single mutants. (a) Cartoon representation of the linear NspS sequence with identities of residues found in single-missense mutants is shown above ribbon representations of the open and closed models of NspS; all are coloured as a rainbow from N-terminus (dark blue) to C-terminus (red). Dotted shapes indicate regions undergoing movement between the two conformations.

Location of single-missense mutations in NspS homology models

We initially observed the residues with single-missense mutations were located in two main regions of the NspS protein: residues 40–89 and 216–281 (Fig. 4). In three dimensions, these two regions are found on each lobe of the NspS protein where S216, V218, R219, R242 and F243 are on one lobe (dashed triangle Fig. 7a) and the remaining 14 residues are on the second lobe (dashed circle Fig. 7a). When the protein changes conformations from open to closed, these two lobes move closer together. Upon further investigation, we observed the 3D locations of the amino acids of mutants generated in our screen could be grouped into three spatial categories and were mainly on one face of the modelled NspS protein. These categories included: residues in the putative ligand-binding site (orange in Fig. 7), internal residues (yellow in Fig. 7) and residues on the surface or flexible loops (cyan in Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Categorization of single-mutant residues based on their location on the NspS homology model. (a) Ribbon diagrams of NspS homology models in open (teal) and closed (grey) conformations. Dotted shapes indicate regions that move between the two conformations. The ribbon representation of the NspS homology model in the closed conformation contains docked norspermidine (green sticks). Individual residues identified by mutation are shown adjacent to the ribbon diagrams. (b) Cartoon of linear NspS amino acid sequence with residues of single-missense mutants in coloured bubbles. Amino acid substitutions for each site are in boxes beneath the primary sequence cartoon. Each box is coloured based on mutant responsiveness to exogenous norspermidine: green boxes are responsive and grey boxes are non-responsive (see Fig. 8 for more detail). The red circle above N68 indicates this residue exhibits a significant conformational change between open and closed conformations of the NspS model. (c) Homology models of open and closed forms of the NspS protein with norspermidine responsiveness for single mutants mapped onto the structures. Residues identified in single-missense mutants are shown in all three panels and are coloured by location on the NspS protein model. Orange residues are found in the putative ligand-binding site, yellow residues are found internally and do not interact with norspermidine directly, and cyan residues are located on loops or exposed surfaces. Note: N68 (orange) is found in the ligand-binding site in the closed conformation but is on an exposed loop in the open conformation. Figures were created using Pymol and Microsoft PowerPoint.

More than half (10 out 18) of the mutations generated were in residues that are surface exposed or on flexible loops and may ultimately be important for protein–protein interactions. These were located on one face of the NspS model and were on the same side as the putative ligand-binding crevice (cyan; Fig. 7). These residues were clustered in patches on each lobe in the open conformation of NspS: D43, F64, S79, L82, P83 and F84 on one lobe and S216, R219, R242 and F243 on the other lobe. Two amino acids identified in the screen, N68 and D263, are in the putative ligand-binding site in the closed conformation (orange, Fig. 7). D263 is found deep within the putative ligand-binding site in both open and closed forms, whereas N68 is located on a loop that exhibits significant movement toward the putative ligand-binding site upon transitioning from open to closed conformations (Fig. 7). D43 is found on the same loop as N68 but is more surface exposed. Six amino acids are located internally and not within the putative ligand-binding site: L40, F66, L89, V218, N268 and L281 (yellow; Fig. 7). With the exception of V218, all other internal residues are found on the same lobe (Fig. 7).

Identification of the putative NspS norspermidine-binding site by docking norspermidine to the NspS homology model

To determine which residues potentially interact with norspermidine, we docked it into the NspS closed form homology model (Fig. 5b). Based on this model, the residues that line the norspermidine-binding pocket include W41, E42, D43, T44, N68, D69, D70, D90, V92, S93, F131, V172, E173, Y233, S234, G235, D236, Y259, W261 and D263. The residues that form direct interactions with the docked norspermidine include the following: D236 (H-bond between OD2 of the side chain and terminal amine of norspermidine), D263 (H-bond between OD1 of the side chain and central amine of norspermidine), and D70 and D90 that anchor the other end of norspermidine through H-bonds (D70 H-bond between OD1 and OD2 of the side chain and terminal amine of norspermidine, and D90 H-bond between OD1 of the side chain and terminal amine of norspermidine). Interspersed between the aspartate residues that form direct H-bonds to norspermidine are a series of aromatic residues [Y233, W41 (not shown), W261 and F131] that appear to anchor the norspermidine molecule through hydrophobic interactions and cation-pi bonding with the norspermidine backbone (Fig. 5c) [45].

Locations of multiple-missense mutations in NspS homology models

The distribution of sites found in double and triple mutants is much wider compared to single-missense mutations. However, 69 % (22/32) of these mutants had a residue represented by single-missense mutants. Interestingly, two of these multiple-missense mutants not represented by single-missense mutants contained residues that were predicted to be important for norspermidine binding [2/10; R112P/D236 (mut1355), E42G/V102I/E173K (mut1423)]. The remaining eight multiple-missense mutants without a single mutant representative had mutations in the signal peptide [3/10; W8R/Y213N (mut25), A33D/N115K (mut1202 and mut1222)], close to the ligand-binding site [1/10; D170Y/N183H/F283I (mut118)], regions close to locations of single-missense mutants [2/10; L75F/S171N (mut3), D67N/L341H (mut1384)], and new locations not identified in single mutant clones [2/10; T174R/A204S (mut1459), R112H, P177H, L343H (mut1104)] (Table 2). Thus, most mutant clones identified in the screen, regardless of number of mutations, represented similar regions of the NspS protein. The clones without single-missense mutant representatives would require further study to elucidate contributions of these additional residues and is beyond the scope of this current study.

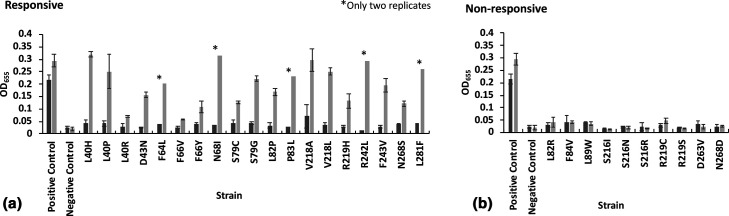

Norspermidine addition had varying effects on NspS mutant clone biofilm formation

Our initial mutagenesis screen identified residues of NspS that were important for biofilm formation in the absence of norspermidine. To determine if these mutations affected the response of V. cholerae biofilm formation to norspermidine, we assayed biofilm formation in the presence of norspermidine (Fig. 8). Nineteen of the 29 distinct mutants showed an increase in biofilm formation in response to norspermidine, but the levels of the response varied among mutants (Fig. 8a, b , Table S2). On the other hand, ten mutations in seven distinct amino acids completely abrogated the biofilm response of the bacteria to norspermidine. Since biofilm formation in the presence of either spermine and/or spermidine is already very low, the responsiveness of the clones to these polyamines was not tested. Additionally, we did not test the effect of adding norspermidine on biofilms for double- and triple-missense mutant clones and, therefore, focused our analysis on single-missense mutants.

Fig. 8.

Responsiveness of NspS mutants to norspermidine. Effect of addition of norspermidine on biofilm formation of mutant clones. Each mutant clone is listed only by the single-missense mutation present in that strain of V. cholerae ΔnspS pACYC184::nspS-V5. The positive control is V. cholerae ΔnspS pACYC184::nspS-V5 and the negative control is V. cholerae ΔnspS pACYC184. A t-test was used to compare biofilm formation between LB only (dark grey bars) and LB +100 µM norspermidine (light grey bars) for each individual mutant clone analysed. Clones that showed a statistical difference (P value of <0.05) in biofilm formation in the presence of norspermidine were deemed responsive. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the error bars show the standard deviation of three biological replicates. For five mutants indicated by stars, only two replicates were performed due to COVID-19-related limitations. (a) Responsive clones. (b) Non-responsive clones.

As described, 18 unique sites on the NspS protein were found to be mutated in the single-missense mutant clones. Eight out of 18 (L40, F66, S79, L82, S216, V218, R219, N268) were mutated to more than one amino acid. In some cases, (e.g. S216), mutant clones were non-responsive to norspermidine regardless of the type of the amino acid change (Figs 7b and 8). In others, missense mutations exhibited differential effects on biofilm formation in the presence of norspermidine depending upon the residue that was encoded. For example, L82, R219 and N268 exhibited varying responses, whereas L40, F66, S79, S216 and V218 exhibited the same response regardless of residue substituted (Figs 7b and 8). Sites that had at least one unresponsive substitution included L82, F84, L89, S216, R219, D263 and N268.

Thus, some of the amino acids identified in our screen are important for NspS to enhance biofilm formation in the absence of norspermidine, but not in its presence. It is possible that when NspS is in its norspermidine-bound closed form, other residues of NspS are exposed that contribute to upregulation of biofilm formation, likely through its interaction with MbaA. To identify these, a similar random mutagenesis and screening experiment would have to be conducted in the presence of norspermidine.

Responsiveness of mutants to norspermidine based on their location in the homology model

Based on our NspS model, the distribution of single-missense mutations of NspS were both internal and external. Therefore, the effect of norspermidine on the mutant biofilm response could be due to protein–protein interactions and/or a disruption of norspermidine binding to NspS. To examine whether there was any pattern to the responsiveness of particular mutants to norspermidine, we studied the open and closed NspS homology models and the distribution of these residues in 3D space (Fig. 7c). We observed most non-responsive mutants were found in two main locations: (1) in or near the ligand-binding site (L89, D263, N268), or (2) on surface residues on each lobe (L82, F84, R219, S216).

Mutations in or near the ligand-binding site could render NspS non-responsive to norspermidine by disrupting ligand-binding interactions. For example, D263 interacts with norspermidine via an H-bond to the central amine (Fig. 5c). D263V was non-responsive to norspermidine addition and substitution to the hydrophobic residue valine could disrupt this H-bonding. L89 is located just outside the norspermidine-binding site, and forms H-bonds between its backbone oxygen and amide with the backbone oxygen and amide of C264, which is adjacent to D263. In the closed conformation, the side chain of L89 fits snugly into a hydrophobic pocket created by L77, F97 and F103 residues. This pocket is found between α2, β3 and α3 (Fig. 4), which is created upon closure from open to closed conformations (between cyan and dark blue regions in Figs 6 and 7). Substitution of L89 to a larger residue like W could prevent or alter closure of this region of the protein, thereby affecting norspermidine binding and non-responsiveness to norspermidine we observed. N268 is found on a loop directly above the pocket mentioned for L89 and is close to the loop that contains L82 and F84. Substitution of N268 for a negatively charged aspartate residue may disturb the conformation of these regions of the protein and affect closure, binding of norspermidine or potential interaction with other proteins, most likely MbaA.

In addition to disruptions in the ligand-binding site, it appears another driver for non-responsiveness of NspS to norspermidine may be due to potential alterations of key NspS hydrophobic or H-bonding interactions with its protein interaction partner(s). For example, L82 and F84 are located in a hydrophobic region of the NspS protein model along with Y39, W41, F66 and L77 and may be important for hydrophobic interactions. On the other hand, S216 and R219 are located on a separate lobe of NspS than L82 and F84 and may be important for H-bonding with protein interaction partners. Nearly all mutants of S216 and R219 residues exhibited non-responsiveness toward norspermidine, with the exception of R219H, which retains a positive charge. Based on these results, specific hydrophobic and H-bonding interactions between these lobes of NspS and the surface of its putative protein interaction partner MbaA may contribute to norspermidine responsiveness and biofilm formation. Binding assays would need to be performed to test these predictions.

Conservation of residues and secondary structural elements in NspS structural and functional homologues

Periplasmic ligand-binding proteins share a common protein fold but have different residues in their ligand-binding sites that contribute to ligand selectivity. Since only periplasmic ligand-binding proteins that are components of ABC-type transporters have been structurally characterized, we used our NspS homology model to compare the overall structure and ligand-binding-site residue conservation between structural and functional homologues. The functional homologues used in this analysis are those we previously identified but have not been characterized (24; UniProt IDs: A8FVY0, A4VGH6, Q92RK9, A1SUA3 and Q2S7Q6).

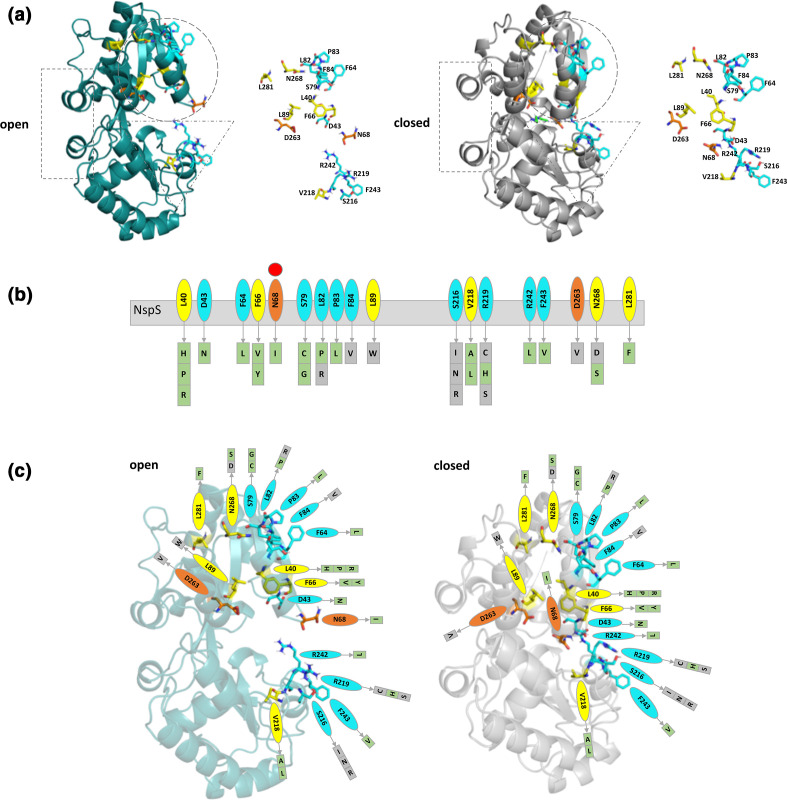

To compare the different homologues, we built homology models of the functional homologues using the same structural template as the NspS closed homology model, PDB ID: 3TTN, and compared the homology models and crystal structures. We also examined the sequence similarity of the full protein sequence and ligand-binding-site residues for both structural and functional homologues (Fig. 9, Table S1). We initially expected the sequence identity of the NspS functional homologues to be more similar compared to the sequence identity of the structural homologues since they constitute two different types of functions. However, we found the functional homologues shared between 22–33 % sequence identity with NspS compared to 17–26 % sequence identity for the NspS structural homologues. Next, we investigated the number of conserved residues in the ligand-binding sites for both structural and functional homologues (Fig. 9b, Table S1). We found the sequence identity for NspS functional homologues (35–65 % identity) was somewhat higher than structural homologues (15–45 % identity). Given that most of these proteins bind or are predicted to bind polyamines, we would expect to see some level of conservation for key ligand-binding-site residues.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of NspS functional and structural homologues. (a) Multiple sequence alignment of NspS with previously identified functional homologues: HCH_06688 (UniProtID: Q2S7Q6) from Hahella chejuensis, Ssed_2394 (UniProtID: A8FVY0) from Shewanella sediminis, PST_0371 (UniProtID: A4VGH6) from Pseudomonas stutzeri, SMc00991 (UniProtID: Q92RK9) from Rhizobium meliloti, and Ping_1238 (UniProt ID: A1SUA3) from Psychromonas ingrahamii . Signal peptide sequences were removed and the alignment was generated by aligning homology models of all functional homologues and NspS with Promals3D. The figure was produced using ESPRIPT where red highlighted residues are completely conserved and yellow residues share some sequence similarity. (b) Comparison of putative ligand-binding residues across functional and structural homologues. The residues shown are from NspS around the docked norspermidine (purple ball and stick). When the protein adopts the closed conformation, the residues that encompass the ligand-binding site surround the ligand in a cylindrical shape. Therefore, the binding site was separated into two regions for clarity: those residues from the top and bottom lobes of the NspS homology model. The overlay views of the ligand-binding site have residues from the top lobe in thick sticks and bold residue numbers and residues from the bottom lobe in thin lines and unbold text. (c) Comparison of the E. coli PotD protein crystal structure (PDB ID: 1POT; blue; first ribbon diagram) with the NspS homology model (grey) ribbon diagrams. PotD is an ABC transporter periplasmic binding protein whereas NspS is a signal transduction periplasmic binding protein. Note, no crystal structure of periplasmic binding proteins involved in signal transduction (NspS functional homologues) have been determined. The regions of the NspS homology model that diverge compared to PotD and other structural homologues are coloured red (NspS residues 79–84, 145–163, 202–218, 240–248; second ribbon diagram); an overlay of the two proteins is shown in the fourth ribbon diagram. The third ribbon diagram has these regions of variability in red and also shows residues identified in this study via mutagenesis in purple for single mutants and yellow for double mutants.

We then compared the conservation of specific ligand-binding-site residues between structural and functional homologues and found 50 % of these residues (10/20) were not conserved in any of the structural homologues compared to 20 % (4/20) not conserved in functional homologues (Table S1). Additionally, the percent conservation of NspS residues varied between the two types of homologues, with fewer conserved top-lobe residues for structural homologues and similar conservation for bottom-lobe residues. One of the most striking non-conserved NspS residues was N68. This residue appears to be an insertion located on a loop, and protrudes deeper into the ligand-binding site compared to other homologues. Since NspS binds norspermidine, its presence may be specific for proteins that bind this polyamine. Additional NspS residues that are not conserved in functional or structural homologues include T44, V172, and Y259. While we do not know the roles of all NspS ligand-binding-site residues, studies with some structural homologues have shown that specific residues in this site are critical for polyamine-binding affinity or selectivity, including those corresponding to NspS residues D90, E173 and W261 [40].

While ligand-binding-site residues of functional and structural homologues were not completely conserved, we observed significantly more deviations in secondary structure or insertions of residues within loop regions between these two types of homologues. When we compared the structural homologues (crystal structures) and functional homologues (homology models), we observed significant alterations in NspS residues 79–84, 145–163, 202–218 and 240–248 (Figs 4 and 9a, c). Some of the mutants that were identified in our mutagenic screen were also located in these regions of NspS. These alterations could help differentiate periplasmic binding proteins involved in signal transduction with those involved in transport. Since these regions are primarily surface exposed or mobile, they may also contribute directly to protein–protein interactions, such as those between NspS/MbaA.

Conclusion

In this study, we have identified NspS residues required to support biofilm formation in V. cholerae , both in the absence and presence of norspermidine. Interestingly, the majority of these residues clustered in two distinct surface-exposed regions of the top and bottom lobes of NspS. It is plausible that these amino acids make up two surface patches on NspS that are important for interaction with another periplasmic protein. While we predict that this protein is MbaA, without experimental verification we cannot eliminate the possibility of another yet unidentified protein partner. Several internal residues in both of the lobes, including residues in the putative ligand-binding site, likely contribute to NspS function by ensuring correct conformation of the NspS top and the bottom lobes. To test the predictions of our model, future structural and biochemical studies of NspS are required. These include determining the 3D structure of NspS in the presence and absence of norspermidine, proteinprotein interaction studies with NspS and MbaA, and analysing the effect of the mutations identified in this work on norspermidine binding to NspS and its interaction with MbaA. The results of these proposed studies will be important for elucidating further details of the NspS and MbaA interaction and will shed light on the mechanism of signal transduction for other members of this class of signalling systems.

Finally, our comparison of the structural and functional homologues of NspS revealed that overall sequence identity of this class of proteins is insufficient for predicting protein function. Typically, genes encoding these proteins reside either adjacent to genes encoding other components of the ABC type transporter or those encoding MbaA-like GGDEF/EAL proteins. Thus, genomic context, if available, needs to be taken into consideration when assigning protein function for this family of proteins.

Data availability

Data are available from the co-corresponding authors upon request.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

Research reported in this work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM133506 (to M.L.K.) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under Award Number R15AI096358 (to E.K.).

Author contributions

E.K. conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, resources, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding. M.L.K. conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding. E.C.Y. methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, visualization. J.T.B. methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing-review and editing, visualization.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: c-di-GMP, bis-(3′−5′) cyclic dimeric GMP; CT, cholera toxin; DGC, diguanylate cyclase; GA, Genetic Algorithm; HRP, Horseradish Peroxidase; LB, Luria-Bertani; nspd, norspermidine; PBS-T, 0.05 % (v/v) Tween 20 solution in 1X PBS; PDE, phosphodiesterase; 5′pGpG, 5′-phosphoguanylyl-3,5′-guanosine; spd, spermidine; TCP, toxin co-regulated pilus.

Two supplementary tables and one supplementary figure are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kierek K, Watnick PI. Environmental determinants of Vibrio cholerae biofilm development. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5079–5088. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5079-5088.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colwell RR, Spira WM. The ecology of Vibrio cholerae. In: Barua D, Greenough WB, editors. Cholera. Current Topics in Infectious Disease. Boston, MA: Springer; 1992. pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaper JB, Morris JG, Levine MM. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/CMR.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wernick NLB, Chinnapen DJ-F, Cho JA, Lencer WI. Cholera toxin: an intracellular journey into the cytosol by way of the endoplasmic reticulum. Toxins. 2010;2:310–325. doi: 10.3390/toxins2030310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrington DA, Hall RH, Losonsky G, Mekalanos JJ, Taylor RK, et al. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faruque SM, Biswas K, Udden SMN, Ahmad QS, Sack DA, et al. Transmissibility of cholera: in vivo-formed biofilms and their relationship to infectivity and persistence in the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6350–6355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601277103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson K. Roles of motility and flagellar structure in pathogenicity of Vibrio cholerae: analysis of motility mutants in three animal models. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2727–2736. doi: 10.1128/IAI.59.8.2727-2736.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watnick PI, Kolter R. Steps in the development of a Vibrio cholerae El Tor biofilm. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:586–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae . Dev Cell. 2003;5:647–656. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costerton JW, Cheng KJ, Geesey GG, Ladd TI, Nickel JC, et al. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:435–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Römling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beyhan S, Odell LS, Yildiz FH. Identification and characterization of cyclic diguanylate signaling systems controlling rugosity in Vibrio cholerae . J Bacteriol. 2008;190:7392–7405. doi: 10.1128/JB.00564-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karatan E, Watnick P. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:310–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabor CW, Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabor CW, Tabor H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/MR.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Igarashi K, Kashiwagi K. Polyamines: mysterious modulators of cellular functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:559–564. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michael AJ. Polyamine function in archaea and bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:18693–18701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.005670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karatan E, Duncan TR, Watnick PI. NspS, a predicted polyamine sensor, mediates activation of Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation by norspermidine. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7434–7443. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7434-7443.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinnis MW, Parker ZM, Walter NE, Rutkovsky AC, Cartaya-Marin C, et al. Spermidine regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation via transport and signaling pathways. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;299:166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cockerell SR, Rutkovsky AC, Zayner JP, Cooper RE, Porter LR, et al. Vibrio cholerae NspS, a homologue of ABC-type periplasmic solute binding proteins, facilitates transduction of polyamine signals independent of their transport. Microbiology. 2014;160:832–843. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.075903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobe RC, Bond WG, Wotanis CK, Zayner JP, Burriss MA, et al. Spermine inhibits Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation through the NspS–MbaA polyamine signaling system. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:17025–17036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.801068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zappia V, Porta R, Cartenì-Farina M, De Rosa M, Gambacorta A. Polyamine distribution in eukaryotes: occurrence of sym-nor-spermidine and sym-nor-spermine in arthropods. FEBS Lett. 1978;94:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80928-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto S, Shinoda S, Kawaguchi M, Wakamatsu K, Makita M. Polyamine distribution in Vibrionaceae : norspermidine as a general constituent of Vibrio species. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29:724–728. doi: 10.1139/m83-118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamana K, Matsuzaki S. Widespread occurrence of norspermidine and norspermine in eukaryotic algae. J Biochem. 1982;91:1321–1328. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stillway LW, Walle T. Identification of the unusual polyamines 3,3′-diaminodipropylamine and n,n′-bis(3-aminopropyl)-1,3-propanediamine in the white shrimp Penaeus setiferus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;77:1103–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(77)80092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michael AJ. Polyamines in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:14896–14903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.734780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milovic V. Polyamines in the gut lumen: bioavailability and biodistribution. Eur J Gastroen Hepatol. 2001;13:1021–1025. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy GM. Polyamines in the human gut. Eur J Gastroen Hepat. 2001;13:1011–1014. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto M, Kibe R, Ooga T, Aiba Y, Kurihara S, et al. Impact of intestinal microbiota on intestinal luminal metabolome. Sci Rep. 2012;2:233. doi: 10.1038/srep00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bomchil N, Watnick P, Kolter R. Identification and characterization of a Vibrio cholerae gene, mbaA, involved in maintenance of biofilm architecture. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1384–1390. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1384-1390.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C, Chen J. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:317–364. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugiyama S, Matsuo Y, Vassylyev DG, Matsushima M, Morikawa K, et al. The 1.8-Å X-ray structure of the Escherichia coli PotD protein complexed with spermidine and the mechanism of polyamine binding. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1984–1990. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Emergence of a new cholera pandemic: molecular analysis of virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae 0139 and development of a live vaccine prototype. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:278–283. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Toole GA. Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J Vis Exp. 2011;47 doi: 10.3791/2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, Studer G, Tauriello G, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu D, Lim SC, Dong Y, Wu J, Tao F, et al. Structural basis of substrate binding specificity revealed by the crystal structures of polyamine receptors SpuD and SpuE from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2012;416:697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sønderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pei J, Kim B-H, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolinsky TJ, Nielsen JE, McCammon JA, Baker NA. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W665–W667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scrutton NS, Raine ARC. Cation-pi bonding and amino-aromatic interactions in the biomolecular recognition of substituted ammonium ligands. Biochem J. 1996;319:1–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3190001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the co-corresponding authors upon request.