Abstract

Introduction:

Human reproduction is a multifaceted process reliant on proper blastocyst implantation, placental and fetal membrane development, and delivery of a healthy baby. Multiple factors and pathways have been reported as critical machineries for cell differentiation and survival during pregnancy and most of them involve glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3α for cell differentiation, survival and for maintaining cellular homeostasis. Several reports on GSK3’s functional role exist; however, a specific role of GSK3 in reproductive tissues and its contribution to normal or abnormal parturition are still unclear. To fill this knowledge gap, a systematic review of literature was conducted to better understand the functional role of GSK3 in various intrauterine tissues during implantation, pregnancy, and parturition.

Methods:

A systematic review of literature on GSK3 expression and function reported in reproductive tissues during pregnancy, published between 1980–2017 in English, using three electronic databases (Web of Science, Medline, and ClinicalTrials.gov) was conducted. The selection of studies, data extraction and quality assessment was performed in duplicate by two independent reviewers.

Results:

A total of 738 citations were identified, 80 were selected for full text evaluation and 25 were included for final review. GSK3 regulation and function was mostly studied in placental tissue and cells (12), cells of fetal origin (8), cells of uterine origin (6), and ovary (2). Measurements of total GSK3 and its isoforms (α and/or β) were determined mostly by western blot analysis. GSK3 is primarily reported as a downstream responder of AKT, Wnt and reactive oxygen species related pathways where is played a critical role in cell survival and growth in reproductive tissues.

Conclusions:

GSK3 is functionally linked to blastocyst implantation, establishment of pregnancy, trophoblast migration and invasion, decidualization, and term and preterm labor. Few reports specifically studied GSK3s expression and function in any reproductive tissues but mostly as secondary signaler of various conserved cell signaling pathways. Lack of scientific rigor in studying GSK3’s role in reproductive tissues makes this molecules function still obscure. No studies have reported GSK3 in cervix and very few reports exist in myometrium and decidua. GSK3 functions are hardly studied in reproductive tissues, and several knowledge gaps are identified requiring more functional studies in reproductive biology.

Keywords: Fetal Membranes, Reproduction, Wnt, p38MAPK, AKT, ROS, parturition, cell cycle, phosphorylation

Introduction

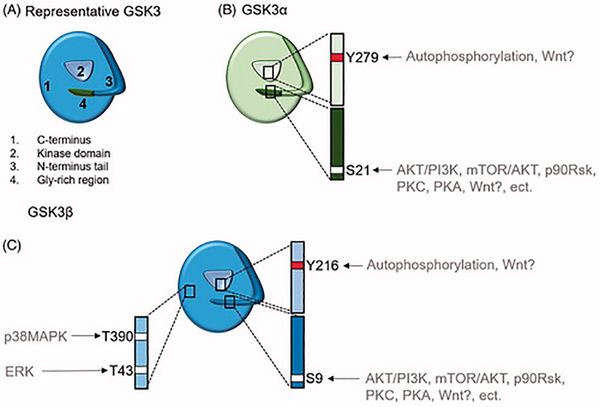

Human reproduction is a complex process reliant on multitudes of cellular signaling molecules for proper implantation, development, and delivery of a healthy fetus. Understanding these regulatory molecules, their expression and function in various reproductive tissues are important to determine their contributions to various pregnancy related functions. Aberrant expressions and functions of these molecules can contribute to abnormal pregnancy environment and adverse outcomes (1–3). Glycogen synthase kinase (GSK) 3 is one of such key cell function regulatory molecule. GSK3 is a Serine/ Threonine kinase which is regulated by multiple phosphorylation sites (Fig. 1) and functions in a number of processes in the cell (4). GSK3 exists as two isoforms- the α (alpha) and the β (beta) with structural similarities within their kinase domain (5) and molecular weights of 51kd and 47kd respectively (6). Subtle differences arise in N- and C-terminal sequences (5) suggesting distinct biological functions(7).

Figure 1: Graphical representation of GSK3 isoform phosphorylation sites.

A) Showing the common regulatory sites of GSK3α/β. B) Representative structure of GSK3α containing a inhibition phosphorylation site (white) Ser21 on its N-terminal tail which can be phosphorylated by AKT/PI3K, mTOR/AKT, p90Rsk, PKC, PKA, and potentially the Wnt pathway. The N-terminal tail can act as a pre-phosphorylated substrate, or pseudosubstrate when stimulated by these upstream kinases. GSK3α also contains an over activation site in its kinase domain, Y279, which has been documented to be active by autophosphorylation. C) Representative structure of GSK3β containing a inhibition phosphorylation site (white) Ser9 on its N-terminal tail which can be phosphorylated by AKT/PI3K, mTOR/AKT, p90Rsk, PKC, PKA, and potentially the Wnt pathway. GSK3β also contains an over activation site in its kinase domain, Y216, which has been documented to be active by autophosphorulation. Uniquely, p38MAPK (T390) and ERK (T43) can also inhibit GSK3β by phosphorylating it on its C-terminus.

There are many upstream regulators of GSK3’s function in response to a variety of signals. Some of the main GSK3 regulators include Wnt, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/ Protein kinase B (AKT), extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38 mitogen activated kinase (MAPK). These pathways are reported to play important roles in pregnancy maintenance as well as term and preterm births (8–12). Close to 100 proteins have been suggested to serve as GSK3 substrates (13). GSK3 can be found in the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus (14) or bound to complexes such as the ‘β-catenin destruction complex’ (15) a molecule widely reported to promote cell survival. The ‘β-catenin destruction complex’ includes GSK3, adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin-1, casein kinase-1 (CK-1) and cytosolic β-catenin (16). In the absence of Wnt signaling, β-catenin gets phosphorylated by GSK-3, causing ubiquitin-mediated degradation of β-catenin that threatens cell survival (16).

p38MAPK is a multifunctional kinase that controls various cellular functions including cell growth and development and stress associated cell death. Recent reports from our laboratory (17, 18) and many others have noted stress kinases such as p38MAPK play a major role in regulating cellular functions in response to ROS during pregnancy and parturition. p38MAPK also has the ability to functionally control other primary and secondary signaling molecules like GSK3 via phosphorylation. Suggesting at term, active p38MAPK could phosphorylate (T390 (19, 20); Figure 1) and suppress GSK3. This inactivation can lead to an accumulation of β-catenin and the promotion of cell survival transcription factors. This increasing of β-catenin could play a homeostatic role between p38MAPK induced senescence and GSK3 regulated cell survival allowing intrauterine tissues to survive till delivery. However, due to large number of regulators that control GSK3’s function and target substrates for GSK3, the exact functional role of GSK3 is hard to determine.

A systematic review of literature was conducted to provide a comprehensive functional role of GSK3in reproductive tissues and to identify knowledge gaps to derive better hypothesis in future experiments. Our objectives are; 1) Identify reports on GSK3 associated functional changes in human and animal pregnancy and parturition, 2) Determine the mechanistic roles of GSK3 reported in human and animal pregnancy and parturition, and 3) Determine the knowledge gaps in GSK3’s functional role in human and animal pregnancy and parturition.

Methods:

A systematic review of the literature was conducted as per the requirements of the MOOSE group and PRISMA Statement (21, 22). This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO.

Search criteria for identification of studies

A systematic review of the literature published from 1980–2017 in English was collected from 3 databases: Ovid, Web of Science, and clinicaltrials.gov with the assistance of a librarian team at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed to study GSK3’s expression, function and mechanistic role in the intrauterine compartments and other reproductive organs of interest (ovaries, implanted blastocyst, fetal membranes, placenta, and uterus) during gestation (implantation through development) and parturition (at term or preterm delivery) (Appendix 1).

Selection criteria

Types of studies:

This review is restricted to studies primarily focusing on GSK3 in humans and all animal models of pregnancy. Original research studies were selected, which investigated GSK3 in various intrauterine components during implantation, pregnancy, and parturition. Studies were excluded if they were not related to GSK3, not related to reproductive period, specifically embryogenesis and contraception, review articles, below average quality score, or full text was not available (either published as an abstract only or not obtained from authors upon request). Studies were included if it reported samples from subjects at full term gestation (≥ 37 weeks) who were either in labor or not in labor at the time of collection. Studies were also included if results were solely related to patients with preterm labor and delivery (both spontaneous and induced), chorioamnionitis, or studies that utilized cell lines from gestational tissues irrespective of maternal age, fetal gender, socio demographic and other clinical factors, geographic location and ethnicity and race.

Types of outcome measures:

Two types of outcomes measurements reported were extracted for data analysis: 1) Expression and functional changes associate with GSK3 in reproductive tissues, and 2) Mechanistic roles of GSK3, during impanation, pregnancy, and parturition in human and animal models.

Specifically, we examined studies that assessed GSK3 RNA or protein expression changes, its activators and repressors, mechanisms of activation or inactivation and biological pathways impacted in response to changes in GSK3’s function.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies:

All citations retrieved through the search strategy were downloaded to a common storage folder where two authors (N.L. and L.R.) independently screened the title and abstracts of the citations. Titles and abstracts that were not related to GSK3, did not fit our inclusion criteria (i.e. reproductive tissues in implantation, pregnancy and parturition) or review articles were removed and duplicates were excluded. The studies, which fulfilled the selection criteria, were included for full text review and data extraction.

Data extraction:

A data extraction form was created for this study to collect the following information: study primary author, year of publication, journal of publication, country of origin for primary author, assessment of GSK3 isoforms, assay type used to determine GSK3 expression or function, gestational tissue studied, and the findings and or end phenotype measured in response GSK3s activity. Two authors (N.L. and L.R) independently extracted data from included reports, compared their findings, resolved disagreements through discussion and produced a single final form for each included study.

Quality assessment:

Quality assessment tool for systematic reviews have not been well defined for basic science research. Therefore, guidelines recently described by Hadley et al.(23) were used. Criteria used for quality improvement included the following; hypothesis driven study designs and approaches, strength of study design as defined by ascertainment of samples, description of sample collection, processing, and storage, description of reagents used for specific assays with detailed protocol that are sufficient to reproduce data, scientific rigor with details on appropriate controls and statistical tests, and sufficient explanation of results and if the results support the conclusions (Appendix 2) were analyzed per article and a score was given ranking them as poor, acceptable, or good quality.

Data synthesis

Based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria, data that reported GSK3’s role in tissues of interest (implanted blastocyst, fetal membranes, placenta, ovaries, and uterus) during implantation, pregnancy, and parturition either in humans or animal models were gathered. Based on these, we synthesized functions of GSK3 in each one of these tissues and document the major upstream regulators, downstream targets and functions, and project knowledge gaps that yet to be filled.

Results:

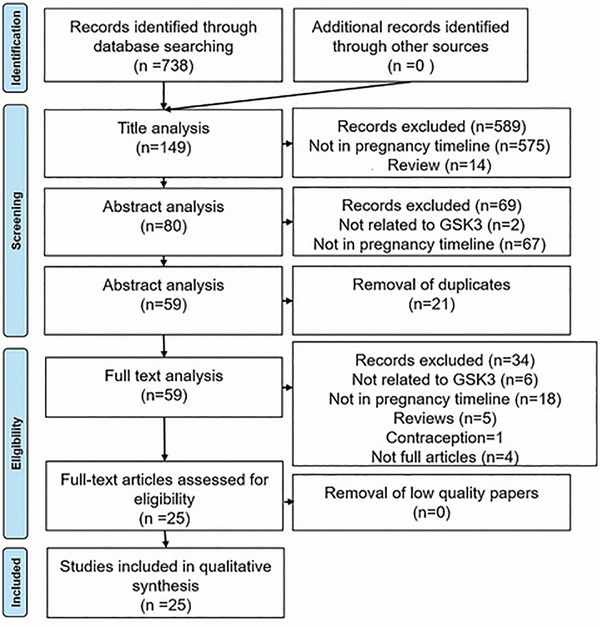

The search of 3 databases for reports published in English between 1980–2017 yielded 738 citations. After screening citations by title, 149 articles remained, which were again screened by abstract. A total of 80 studies were included for full text review. After removing duplicates, 59 studies remained. After full text review, 25 studies were included for final data extraction and analysis (Table 1) (Fig. 2).

Table 1:

Systematic Review Results

| Authors | Country | Year | Species studied | Type of study | Type of sample | Methods | Upstream GSK3Î2 | Form of GSK3 | Down stream function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hua et al. | China | 2017 | Human | Treatment of oligohydramnios | Amnion wish cells | WB and siRNA | Tanshinone IIA | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | P-GSK3Î2 cant inhibit APQs which can now be upregulated |

| Lee et al. | United States | 2016 | Ewes | Establishment of pregancy | Oaries were collected and the CL isolated | WB | EGR->AKT | P-GSK3Î2 No phosphorilation site mentioned | Î2-Catenin and P-CREB, leads to programed survial and establishment of pregancy |

| Feng et al. | China | 2016 | Human | Magnetic fields (Other) | Amnion epithelial cells | WB | ROS | P-GSK3Î2 S9 |  |

| Astuti et al. | Japan | 2015 | Human | Trophoblast differentiation | HTR-8/Svnevo and human extravillous trophoblast | WB | PI3K and AKT | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Surivival |

| Lim et al. | Australia | 2015 | Human | Labor | Fetal membranes and myometirum | WB, inhibitor CHIR99021, and siRNA | TLRs | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 | Inflammation, PGE2, Cox2, MMP9 |

| Yung et al. | U.K | 2014 | Human | Tissue preservation (Other) | Placenta | WB | AKT-mTOR | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 |  |

| Zhou et al. | United States | 2013 | Human | Preeclampsia (PE) | PE placental cytotrophoblasts | WB | SEMA3B -> VEGF->PI3K/AKT | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 | Î2-Catenin |

| O'Connell et al. | Australia | 2013 | Mice | Glucose transport | Placenta | PCR | Dexamethosone | Just total GSK3Î2 | GYS1 and GBE1 |

| Lassance et al. | Austria | 2013 | Human | Diabetes | Endothelial cells were isolated from third-trimester human placentas | Bio-Plex phosphoprotein detection kit and WB | PI3K/AKT | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 | Î2-Catenin |

| Cheng et al. | U.K | 2013 | Human | Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) | Endothelial cells-HUVEC (Human umbilical vein endothelial cells) | WB | ROS | P-GSK3Î2 Y216 | Defects in NrF2 necular accumlation and its down stream targets NQO1, Bach1, GCLM, and xCT |

| Yen et al. | Taiwan | 2017 | Human | Decidualization | Human endometrium and term Decidual tissues | WB | ILK | P-GSK3Î2 | Prevented differentation and cell survival |

| Roseweir et al. | Uk | 2012 | Human | Trophoblast differentiation and invation | First trimester extravillious trophoblasts (HTR8SVneo) | WB | Kisspeptin-10 | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Î2-Catenin in cytoplasum and enhance the effects on migration |

| Fischer et al. | Germany | 2011 | Human | Differentation | Bewo | Human Phospho-MAPK Array | Gal-1 ->AKT | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 | ELK1 leading to syncytium formation |

| Lague et al. | Canada | 2010 | Mice | Trophoblast invasion | Decidua | WB | PI3K/AKT | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Represed decidua cells and limited transformation |

| Chiang et al. | Taiwan | 2009 | Human | PE | 293T, BeWo, and JAR cells | IHC and WB | Hypoxia-> suppresion of PI3K/AKT singing | P-GSK3Î2 S9 and Y216 | GMC1 degredation |

| Yung et al. | U.K | 2008 | Human | PE and IUGR | IUGR and PE placenta and JEG-3 cells | WB | AKT->mTOR | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | eIF2BÎμ, 4E-BP1, and Eef2k |

| LaMarca et al. | United States | 2008 | Human | Trophoblast invasion | First trimester extravillous cytotrophoblast cell line-SGHPL-4 | WB | EGFR-PI3K->AKT | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Î2-Catenin |

| Rider et al. | United States | 2006 | Rats(Ovariectomized) | Decidualization in early pregnancy | Uterine tissue (uterine horns from OVX rats) | Indirect immunoperoxidase analysis and WB | Wnt | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Î2-Catenin and TCF/LEF |

| Dash et al. | England | 2005 | Human | PE | Primary human extravillous cytotrophoblasts-SGHPL-4 | WB | HGF->AKT | P-GSK3Î2 No phosphorilation site mentioned | Î2-Catenin |

| Boronkai et al. | Hungary | 2005 | Human | Syncitiotrophoblastic differentation | Placental tissue, umbilical cord, and membranes | WB | Phospho-AKT | P-GSK3Î2 No phosphorilation site mentioned |  |

| Laviola et al. | Italy | 2005 | Human | IUGR | Placental tissue | WB | PI3K-AKT | P-GSK3α/Î2 S21/S9 |  |

| Bramer et al. | Canada | 2017 | Mares (Horse) | Glucose transport | Endometrial tissue | PCR | Just total GSK3Î2 |  |  |

| Hou et al. | United States | 2010 | Bovine | Establishment of pregancy | Bovine luteal cells during early pregnancy | WB | LH | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | mTOR phosphorilation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 |

| Kim et al. | United States | 2008 | Sheep | Trophoblast migration | Endometrial tissue,conceptus trophectoderm | WB | PI3K/AKT | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | eIF2B |

| Sonderegger et al. | Austria | 2010 | Human | Invasion of human trophoblasts | Trophoblastic SGHPL-5 cells and primary extravillous trophoblasts | WB | Wnt | P-GSK3Î2 S9 | Î2-Catenin |

Figure 2: Prism flow chart.

Prism flow chart documenting GSK3 systematic review search strategy.

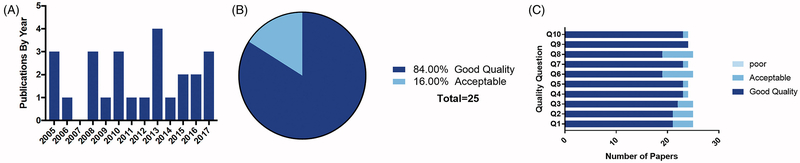

For our chosen timeframe the first GSK3 article was published in 2005 and reached the most number of publications noted in 2013 (Fig. 3 A). As expected, the reports evaluated were 99% basic science or research laboratory-based studies with only one paper related to a clinical case (24). In the latter report, high serum alkaline phosphatase in a 37 weeks pregnant patient revealed increased rate of cytotrophoblast proliferation due to inactivation of GSK3β downstream to AKT activation.

Figure 3: Systematic review quality assessment.

A) Quantity of GSK3 papers per year meeting our criteria. B) Percent of final articles from our systematic review that scored ‘good quality’ or ‘acceptable’. No papers were scored poor quality. C) Scores of each of our final 25 papers broken down per question.

Quality Assessment:

Twenty-one articles (84%) were graded as good quality, and the rest (4; 16%) were graded as acceptable quality, with none graded as poor (Fig. 3B–C). Good quality article provided adequate description of sample ascertainment, objectives of study, materials and methods, assay and analytical strategies and adequate description of data.

Main characteristics of studies:

The main characteristics and findings of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. GSK3 studies were conducted by researchers from many different institutions around the globe but predominantly from Europe (40%) and North America (32%). Reports included in our review investigated biological processes involved in pregnancy (starting from implantation) and parturition. Tissues and cells studied included from both fetal and maternal compartments.

Methods used for detecting GSK3 expression and function:

Mechanistic roles of GSK3 analyzed included determination of activators or pathways causing its activation. Functional changes of GSK3 were investigated as either pathways or the endpoint resulting from GSK3 activation. Most studies determined total GSK3 and its isoforms (α and/or β) expressions by western blot analysis. Total GSK3 expression were reported through qPCR (24, 25) and GSK3 activation was determined using indirect immunoperoxidase analysis (26). Phosphorylated forms of GSK3, specifically Ser21 for GSK3α and Ser 9 and Tyr 216 for GSK3β, were studied using western blot analysis, immunohistochemistry (27), indirect immunoperoxidase analysis (26), and also, by bio-plex phosphoprotein detection kit (1). To confirm the functional roles of GSK3 and to provide scientific rigor to their experimental approaches, many studies have included inhibitors of GSK3 like CHIR99021(28), LiCl (27), and siRNA (3) (Table 1).

Main findings:

Studies included in our final review reported multiple reproductive tissues derived from a number of different species. Among all the reports, 18 studies have used tissues/cells of human origin, 2 studies each in mice and sheep, and 1 study each using tissues/cells of rat, bovine and equine origin. We also found that 12 reports conducted studies using placental cells or tissues, 8 studies were using cells/tissues of fetal origin, 6 of maternal uterine origin, and 2 were from the ovary (Table 1).

Most GSK3 studies in reproductive tissues were conducted in placental tissues and cells indicating a role of GSK3 in trophoblast invasion and differentiation (24, 29–35). GSK3’s role in pathogenesis of certain disorders during pregnancy especially preeclampsia and Intra uterine growth restriction (IUGR) were also reported (27, 36–39). Studies of GSK3’s role in other tissues included the following; ovaries for establishment of pregnancy (8, 40), endometrium for decidualization (41, 42), and the fetal membranes and myometrium for initiation of labor (28). Interestingly, there were no reports of GSK3 in the cervix or the vagina.

GSK3 was reported to be involved in numerous signaling pathways in these reports. Thus, there were more than one upstream regulator and downstream targets for GSK3. The most common upstream regulator was Protein Kinase B also known as AKT. AKT was most commonly activated by Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase(PI3K)(1, 29, 32–34, 39), but could also be activated by other less common activators like Galectin 1(43), hepatocyte growth factor (38), or was part of the AKT-mTOR pathway (mechanistic target of rapamycin)(37, 44) (Table 1). GSK3 was also shown to be a part of the Wnt or reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling pathways (45, 46). GSK3 has multiple downstream targets that can lead to a number of different outcomes in reproductive tissues and cells. Eight studies reported β-catenin as downstream (1, 2, 8, 26, 30, 33, 35, 38) target of GSK3 promoting cell survival, while EIF2B (34, 37) was the second most common downstream target documented in 2 studies (Table 1) suggesting GSK3 mediates protein synthesis and cell proliferation.

Our review noted that GSK3 was studied as a part of a major signaling pathway either downstream or upstream to another molecule of interest and not necessarily as the primary molecule of interest for investigation. In placental tissues or cells, GSK3 was reported to be a part of the AKT pathway where it aids in trophoblast differentiation (24, 29, 31), trophoblast invasion (32–34) and likely in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia (2, 27, 37, 38) and IUGR (37, 39). GSK3 as a part of the Wnt signaling pathway was also shown to play a role in trophoblastic invasion using placental cells (35). Trophoblast migration was studied in endometrial tissues and conceptus trophectoderm where GSK3 was reported to aid AKT pathway by promoting translation via EIF2β (34). In ovarian tissues, AKT-GSK3 pathway was involved in pregnancy establishment (8).

As mentioned above, only a handful of studies examined GSK3 as their primary molecule of interest examining its functional role. Lim et al recently reported that in fetal membranes GSK3 may play major role in the terminal processes of human labor at term and preterm where GSK3’s increased activity leading to pro-labor and pro-inflammatory cytokines increase (28).

Astuti et al showed that recombinant Relaxin was able to induce proliferation and cell survival in HTR-8/SVneo cells (transformed extravillous trophoblast) via PI3K-AKT activation and GSK3β phosphorylation leading to cell survival (29). Similar results were reported by Roseweir et al in the same cell system where kisspeptin-10a and its receptor GPR54 regulated hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis to inhibit cancer metastasis. The report showed that a complex signaling pathway involving GSK3β might act as a negative regulator of trophoblast cell migration to possibly restrict the amount of invasion at the time of placentation (30).

Rider et al demonstrated that decidualization may be controlled by an endocrine dependent Wnt signaling where progesterone down regulates GSK3β via the Wnt pathway in uterine tissues (26) where estradiol caused nuclear translocation of β-catenin in the Wnt pathway. Also, in bovine luteal cells, Hou et al have shown that luteinizing hormone via phosphorylation of GSK3β amongst other mechanisms regulates progesterone synthesis, which is critical for the maintenance of pregnancy (40).

Hua et al reported that Tanshinone IIA, extracted from the root of Salvia Miltiorrhiza, stimulate aquaporin (AQP) expression (especially AQP8) in amnion Wish cells via phosphorylation of GSK3β and be a possible mode of treatment for oligohydramnios (3). Feng et al noted that human amnion epithelial cells increase mitochondrial permeability in response to an exposure to 50-Hz of magnetic field (45), an effect mediated by ROS/GSK3β signaling pathway (45). This frequency is important because it is emitted from most cell phones and computers. Other studies that studied about glucose transport in endometrial tissues (47) and placenta (25) and possible causes of gestational diabetes mellitus in HUVEC (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) (46),placental tissue preservation (44) have also been included in the review.

Thus, the number of studies that look exclusively at GSK3’s mechanistic and functional role in reproductive tissues are few and far between.

Discussion:

Twenty-five studies reporting GSK3’s role during pregnancy and parturition were further analyzed for this review. Human and animal origin studies used tissues/cells from placenta, uterus, ovary as well as fetal origin (fetal membranes and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) amongst others. AKT, Wnt, ROS signaling pathways commonly regulated GSK3 while β-catenin was the most commonly reported downstream target.

Based on our systematic review, we report that GSK3 is a major regulator of signaling pathways documented in a number of biological processes involved in pregnancy and parturition. These included establishment of pregnancy and blastocyst implantation, trophoblast migration and invasion, decidualization, placental glucose transport, complications of pregnancy such as: gestational diabetes mellitus, IUGR, preeclampsia, oligohydramnios and labor initiation at term and preterm amongst others. Each of these processes may be activated by different agents via separate signaling pathways that involve GSK3.The multitude of regulators, which phosphorylate and, in the process, modify the activity of GSK3 as well as a large number of possible substrates make understanding and pin pointing its exact function in a particular tissue quite challenging. Even though important biological processes during pregnancy and parturition have been studied, GSK3’s role in other important events like placental growth and its regulation under various oxidative conditions, remodeling of fetal membranes during pregnancy, cervical ripening, myometrial activation, etc. have not been reported.

GSK3 exists as two isoforms α and β (5). We found that in the studies included in our final review, most of them reported β isoform only, although the choice of β isoform for their studies were not properly rationalized. Only 6 of the studies reported and commented on both the isoforms (1, 28, 31, 36, 39, 44). It might be possible that GSK3β is the most studied form due a literature bias suggesting that mammalian GSK3β was more effective than GSK3α (48, 49). These reports; however, did not equalize the level of expression of the two isoforms hiding the fact that α and β are redundant in terms of regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling (5).

GSK3 is a part of a number of signaling pathways in reproductive tissues. The upstream regulators may phosphorylate GSK3 at multiple sites –most commonly the Serine 21 for the α isoform and serine 9 and Tyr 216 for the β isoform. Only 2 studies looked at the Tyr 216 phosphorylation (27, 50) while 3 studies did not report specific phosphorylation sites examined in their experiments (8, 24, 38). Also, from studies conducted in other tissues, GSK3 was also phosphorylated at the Thr 390 residue in humans as part of the p38MAPK pathway (51). However, though p38MAPK was found to play a role in trophoblast migration [29], membrane senescence and parturition, IUGR development (39), and PE (24) none of the studies in this review examined this pathway or this particular phosphorylation site.

ROS induced p38MAPK is a signaling pathway noted to be active in reproductive tissues at term (17, 18). However, none of the studies in the review linked GSK3 and p38MAPK as a regulator of GSK3 function. Two of the studies showed that ROS (50, 52) can be an upstream regulator of GSK3. However, no connection between the two has been made in any of the studies that we reviewed. This might be an important link especially in determining the labor mechanism at term and preterm if looked into in future studies.

Following this review, we conclude that GSK3 is an important regulator that plays a major role in a variety of biological and metabolic processes in reproductive tissues. Targeting this molecule for therapeutic purposes in some of the obstetric complications discussed might prove to be fruitful. However, further studies need to be conducted to understand how activation or inactivation might affect other processes in these cells as it is part of a number of signaling pathways with possible cross talk between these pathways. Also, while conducting studies on GSK3 one needs to be extremely wary of which upstream regulators, phosphorylation sites, and downstream targets need to be looked at as that ultimately defines a particular action of GSK3.

Conclusion:

GSK3’s role in various utero placental tissues have been studies in connection with pregnancy and parturition. GSK3 studies are predominantly confirming its well reported activators or downstream effects. Novel conclusions cannot be derived other than what has already been reported in other biological system. This systematic review failed to find any unique role for GSK in association with the phenotypes of interest included. Function of GSK3 is dependent on the site-specific phosphorylation/modifications (activation/inhibition). Current literature is not sufficient to draw conclusions on activators and inhibitors of phosphorylation at specific sites. Pregnancy and parturition involve several unique changes, specifically constant changes in oxidative radicals and localized inflammation that are required to maintain tissue growth and integrity. GSK3’s role in maintaining tissue homeostasis during micro-environmental changes are hardly studied. Association between GSK3’s altered function contributing to pathological pregnancy outcomes are not reported and current reports are not convincing to draw a precise role due to lack of scientific rigor in experimental approaches. Thus, this review report several knowledge gaps. Mechanistic and functional studies are essential to better understand the contributions of critical cell function regulator. Understanding the role of GSK3 throughout gestation and in normal term pregnancies can provide insights into pathologic activation of its pathways that can cause adverse pregnancies.

Future Directions:

The systematic review has shown us that GSK3 is now emerging as a major regulator of biological funtions in reproductive tissues. However, studies that look primarily at GSK3 as the molecule of interest are few. Further studies in the field that help us understand the exact mechanistic role of GSK3 in reproductive tissues are needed. Such studies would help us understand if GSK3 might serve as a potential target for therapeutic interventions in conditions such as Preeclampsia, IUGR and preterm labor which are major causes of maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the librarian team at UTMB, especially Tara Atkins, for their help with the systematic review process.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant number 1R01HD084532-01A1] awarded to R Menon.

Lauren Richardson is an appointed Pre-doctoral Trainee in the Environmental Toxicology (ETox) Training Program (T32ES007254), supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) of the United States, and administered through the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas.

List of abbreviations:

- (GSK)3αβ

glycogen synthase kinase alpha or beta

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- ERK

Extracellular-signal-Regulated Kinase

- P38MAPK

p38 Mitogen Activated Kinase

- CK-1

Casein Kinase-1

- IUGR

Intra Uterine Growth Restriction

- mTOR

Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin

- EIF2β

Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2) β

- HPG

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal

- HUVEC

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

- AQP

aquaporin

References:

- 1.Lassance L, Miedl H, Absenger M, Diaz-Perez F, Lang U, Desoye G, et al. Hyperinsulinemia stimulates angiogenesis of human fetoplacental endothelial cells: a possible role of insulin in placental hypervascularization in diabetes mellitus. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;98(9):E1438–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Gormley MJ, Hunkapiller NM, Kapidzic M, Stolyarov Y, Feng V, et al. Reversal of gene dysregulation in cultured cytotrophoblasts reveals possible causes of preeclampsia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(7):2862–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua Y, Ding SD, Cheng HH, Luo H, Zhu XQ. Tanshinone IIA increases aquaporins expression in human amniotic epithelial WISH cells by stimulating GSK-3 beta phosphorylation. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2017;473:204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H, Ro JY. Differential expression of GSK3beta and pS9GSK3beta in normal human tissues: can pS9GSK3beta be an epithelial marker? International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Pathology. 2015;8(4):4064–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Force T, Woodgett JR. Unique and overlapping functions of GSK-3 isoforms in cell differentiation and proliferation and cardiovascular development. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(15):9643–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodgett JR. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/factor A. The EMBO Journal. 1990;9(8):2431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta in cell survival and NF-kappa B activation. Nature. 2000;406(6791):86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Banu SK, McCracken JA, Arosh JA. Early pregnancy modulates survival and apoptosis pathways in the corpus luteum in sheep. Reproduction. 2016;151(3):187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bredeson S, Papaconstantinou J, Deford JH, Kechichian T, Syed TA, Saade GR, et al. HMGB1 promotes a p38MAPK associated non-infectious inflammatory response pathway in human fetal membranes. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2014;9(12):e113799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon R Oxidative stress damage as a detrimental factor in preterm birth pathology. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Gao F, Liu YF, Dou HT, Yan JQ, Fan ZM, et al. HB-EGF regulates Prss56 expression during mouse decidualization via EGFR/ERK/EGR2 signaling pathway. J Endocrinol. 2017;234(3):247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zmijanac Partl J, Karin V, Skrtic A, Nikuseva-Martic T, Serman A, Mlinarec J, et al. Negative regulators of Wnt signaling pathway SFRP1 and SFRP3 expression in preterm and term pathologic placentas. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland C What Are the bona fide GSK3 Substrates? International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2011;2011:505607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;148:114–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGFβ-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. J Clin Med. 2016;5(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voskas D, Ling LS, Woodgett JR. Does GSK-3 provide a shortcut for PI3K activation of Wnt signalling? F1000 Biology Reports. 2010;2:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menon R, Boldogh I, Urrabaz-Garza R, Polettini J, Syed TA, Saade GR, et al. Senescence of primary amniotic cells via oxidative DNA damage. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2013;8(12):e83416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menon R, Boldogh I, Hawkins HK, Woodson M, Polettini J, Syed TA, et al. Histological evidence of oxidative stress and premature senescence in preterm premature rupture of the human fetal membranes recapitulated in vitro. American Journal of Pathology. 2014;184(6):1740–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bikkavilli RK, Malbon CC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: Molecular conversations among signaling pathways. Commun Integr Biol. 2009;2(1):46–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, Davis NM, Sokolosky M, Abrams SL, et al. GSK-3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(10):2881–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadley EE, Richardson LS, Torloni MR, Menon R. Gestational tissue inflammatory biomarkers at term labor: A systematic review of literature. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boronkai A, Than NG, Magenheim R, Bellyei S, Szigeti A, Deres P, et al. Extremely high maternal alkaline phosphatase serum concentration with syncytiotrophoblastic origin. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2005;58(1):72–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connell BA, Moritz KM, Walker DW, Dickinson H. Treatment of pregnant spiny mice at mid gestation with a synthetic glucocorticoid has sex-dependent effects on placental glycogen stores. Placenta. 2013;34(10):932–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rider V, Isuzugawa K, Twarog M, Jones S, Cameron B, Imakawa K, et al. Progesterone initiates Wnt-beta-catenin signaling but estradiol is required for nuclear activation and synchronous proliferation of rat uterine stromal cells. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Chiang MH, Liang FY, Chen CP, Chang CW, Cheong ML, Wang LJ, et al. Mechanism of hypoxia-induced GCM1 degradation: implications for the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(26):17411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim R, Lappas M. A novel role for GSK3 in the regulation of the processes of human labour. Reproduction. 2015;149(2):189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astuti Y, Nakabayashi K, Deguchi M, Ebina Y, Yamada H. Human recombinant H2 relaxin induces AKT and GSK3beta phosphorylation and HTR-8/SVneo cell proliferation. Kobe Journal of Medical Sciences. 2015;61(1):E1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roseweir AK, Katz AA, Millar RP. Kisspeptin-10 inhibits cell migration in vitro via a receptor-GSK3 beta-FAK feedback loop in HTR8SVneo cells. Placenta. 2012;33(5):408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer I, Weber M, Kuhn C, Fitzgerald JS, Schulze S, Friese K, et al. Is galectin-1 a trigger for trophoblast cell fusion?: the MAP-kinase pathway and syncytium formation in trophoblast tumour cells BeWo. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2011;17(12):747–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lague MN, Detmar J, Paquet M, Boyer A, Richards JS, Adamson SL, et al. Decidual PTEN expression is required for trophoblast invasion in the mouse. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;299(6):E936–E46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaMarca HL, Dash PR, Vishnuthevan K, Harvey E, Sullivan DE, Morris CA, et al. Epidermal growth factor-stimulated extravillous cytotrophoblast motility is mediated by the activation of PI3-K, Akt and both p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(8):1733–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JY, Song GH, Gao HJ, Farmer JL, Satterfield MC, Burghardt RC, et al. Insulin-like growth factor II activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protooncogenic protein kinase 1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase cell signaling pathways, and stimulates migration of ovine trophectoderm cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3085–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonderegger S, Haslinger P, Sabri A, Leisser C, Otten JV, Fiala C, et al. Wingless (Wnt)-3A Induces Trophoblast Migration and Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Secretion through Canonical Wnt Signaling and Protein Kinase B/AKT Activation. Endocrinology. 2010;151(1):211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y, Gormley MJ, Hunkapiller NM, Kapidzic M, Stolyarov Y, Feng V, et al. Reversal of gene dysregulation in cultured cytotrophoblasts reveals possible causes of preeclampsia.[Erratum appears in J Clin Invest. 2013. October 1;123(10):4541]. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yung HW, Calabrese S, Hynx D, Hemmings BA, Cetin I, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Evidence of placental translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the etiology of human intrauterine growth restriction. American Journal of Pathology. 2008;173(2):451–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dash PR, Whitley GSJ, Ayling LJ, Johnstone AP, Cartwright JE. Trophoblast apoptosis is inhibited by hepatocyte growth factor through the Akt and beta-catenin mediated up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cellular Signalling. 2005;17(5):571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laviola L, Perrini S, Belsanti G, Natalicchio A, Montrone C, Leonardini A, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction in humans is associated with abnormalities in placental insulin-like growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2005;146(3):1498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou XY, Arvisais EW, Davis JS. Luteinizing Hormone Stimulates Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling in Bovine Luteal Cells via Pathways Independent of AKT and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase: Modulation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Endocrinology. 2010;151(6):2846–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yen CF, Kim SH, Liao SK, Atabekoglu C, Uckac S, Arici A, et al. Increased expression of integrin-linked kinase during decidualization regulates the morphological transformation of endometrial stromal cells. Fertility & Sterility. 2017;107(3):803–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rider V, Isuzugawa K, Twarog M, Jones S, Cameron B, Imakawa K, et al. Progesterone initiates Wnt-beta-catenin signaling but estradiol is required for nuclear activation and synchronous proliferation of rat uterine stromal cells. Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;191(3):537–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fisher SJ. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;213(4):S115–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yung HW, Colleoni F, Atkinson D, Cook E, Murray AJ, Burton GJ, et al. Influence of speed of sample processing on placental energetics and signalling pathways: Implications for tissue collection. Placenta. 2014;35(2):103–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng B, Qiu L, Ye C, Chen L, Fu Y, Sun W. Exposure to a 50-Hz magnetic field induced mitochondrial permeability transition through the ROS/GSK-3beta signaling pathway. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Cheng X, Chapple SJ, Patel B, Puszyk W, Sugden D, Yin X, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus impairs Nrf2-mediated adaptive antioxidant defenses and redox signaling in fetal endothelial cells in utero. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Bramer SA, Macedo A, Klein C. Hexokinase 2 drives glycogen accumulation in equine endometrium at day 12 of diestrus and pregnancy. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2017;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruel L, Bourouis M, Heitzler P, Pantesco V, Simpson P. Drosophila shaggy kinase and rat glycogen synthase kinase-3 have conserved activities and act downstream of Notch. Nature. 1993;362(6420):557–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegfried E, Chou TB, Perrimon N. wingless signaling acts through zeste-white 3, the Drosophila homolog of glycogen synthase kinase-3, to regulate engrailed and establish cell fate. Cell. 1992;71(7):1167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng XH, Chapple SJ, Patel B, Puszyk W, Sugden D, Yin XK, et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Impairs Nrf2-Mediated Adaptive Antioxidant Defenses and Redox Signaling in Fetal Endothelial Cells In Utero. Diabetes. 2013;62(12):4088–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, Davis NM, Sokolosky M, Abrams SL, et al. GSK-3 as potential target for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(10):2881–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng BH, Qiu LP, Ye CM, Chen LJ, Fu YT, Sun WJ. Exposure to a 50-Hz magnetic field induced mitochondrial permeability transition through the ROS/GSK-3 beta signaling pathway. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2016;92(3):148–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.