Abstract

Purpose:

This paper examines lack of interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and lack of willingness to use PrEP information sources among men who have sex with men (MSM).

Methods:

Demographic subgroups were compared via odds ratios in this purposive sample of 273 MSM.

Results:

29% were uninterested in learning more about PrEP. Lack of interest was most common among: already PrEP-aware, Caucasian, HIV-positive, aged 40+, well-educated men. Most sources of information about PrEP were deemed unacceptable.

Conclusions:

Fueling the lack of PrEP use among MSM are a lack of interest in PrEP and an unwillingness to utilize existing information resources.

Keywords: pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), men who have sex with men (MSM), gay men, lack of interest in PrEP

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) comprise the largest proportion of Americans diagnosed with HIV and AIDS, accounting for more than one-half of all new HIV diagnoses (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2016a). According to the most recent statistics released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), African-American MSM and Latino MSM alone comprised two of the top three largest groups for new HIV infections, accounting for 31 and 21%, respectively, of all Americans newly infected with HIV (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2016b).

Amidst this backdrop, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medications have been developed and they have been shown to be highly effective at reducing the risk of HIV infection. Current estimates suggest that regular, proper adherence to a PrEP medication regimen can reduce the risk of contracting HIV by 86 ~ 93% (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2017b; Grant et al., 2014; NAM Publications, 2017). Such high rates of success have led the National Institutes of Health and the CDC to promote the adoption of PrEP medications as a key strategy in the ongoing effort to combat the spread of HIV, particularly among MSM.

Despite efforts to promote PrEP, evidence from the scientific community suggests that, among MSM, particularly minority MSM, both awareness and understanding of PrEP medications are low, as is actual adoption of PrEP. As of mid-2018, fewer than 150,000 Americans have ever used PrEP, representing less than 9% of the persons recommended by the CDC to be regular PrEP users (Salzman, 2017a; Siegler et al., 2018). In a forthcoming publication based on a study of gay and bisexual men, (Parsons et al., 2017) reported that more than one-half of the men who met the CDC’s criteria for being considered “PrEP eligible” failed to reach even the contemplation stage of PrEP adoption. In their study of African-American and Caucasian MSM, for example, Eaton, Kalichman, et al. (2017) reported awareness of PrEP to be 61%, but actual usage rates of only 9%. In a different study of African-American MSM attending black gay pride events, Eaton, Matthews, et al. (2017) indicated that awareness of PrEP was 39% and actual use was less than 5%. In a study of lower socioeconomic African-American MSM, Brooks, Landovitz, Regan, Lee, and Allen (2015) reported awareness of PrEP to be 33% with not a single study participant actually using these medications. A Baltimore-based study of African-American MSM (Fallon, Park, Ogbue, Flynn, & German, 2017) reported an 11% awareness figure for PrEP and a 0% usage rate. A small-scale study conducted with Latino MSM couples (Martinez et al., 2016) indicated that awareness of PrEP was only 8%. Data from the CDC suggest that African-Americans and Latinos account for 69% of all newly-diagnosed cases of HIV, yet men from these same “at risk” populations comprise a mere 22% of all new prescriptions for PrEP (Wolitski, 2018). A 2017 study from New York City indicates that men of color were half as likely as their Caucasian counterparts to be prescribed PrEP (Salzman, 2017b). Rolle et al. (2017) reported that 64% of the young African-American MSM in their study said that they were interested in adopting PrEP, but 46% of these men had not attended any PrEP adoption meetings, oftentimes despite repeated attempts on the part of project staff to get them scheduled. Also noteworthy from this particular study is the fact that more than one-third (38%) of the men who were prescribed PrEP medication did not actually begin using PrEP.

Preliminary evidence also has indicated that, among MSM, there may be numerous barriers to adopting PrEP, including conspiracy-related beliefs (Eaton, Kalichman, et al., 2017), stigma perceptions associated with the use of PrEP (Eaton, Kalichman, et al., 2017; Mutchler et al., 2015), skepticism about taking a medication when one is not actually infected with a disease (Brooks et al., 2015), concerns about the physical implications of taking an unknown medication over the long-term (Brooks et al., 2015; Philpott, 2013), language barriers in educating non-English-speaking MSM about PrEP and how/why to use it (Martinez et al., 2016), attitudes in the population-at-large regarding making PrEP more readily available to MSM (particularly MSM of color) (Calabrese et al., 2016), misperceptions that using PrEP is linked with being HIV-positive (Mutchler et al., 2015), and concerns about affordability of PrEP medications (Bratcher, Wirtz, & Siegler, 2018; Brooks et al., 2011). Some researchers have specifically addressed the need for future studies to examine perceptions and potential barriers to PrEP adoption among MSM in general (Parsons et al., 2017) and among minority MSM in particular (Philpott, 2013) because most of the potential barriers just enumerated were identified in one, but only one, published study. More needs to be learned about this topic.

That is where the present paper comes into play. This study focuses on why more MSM are not using PrEP and which subgroups of MSM (based on key demographic characteristics) are more/less PrEP-involved or PrEP-averse compared to others. Specifically, this paper examines issues pertaining to men’s interest in finding out more about PrEP and their willingness to avail themselves of various resources and information sources in order to learn more about the medication. Along with other articles developed out of the same “parent study” (Klein & Washington, 2019a,b; Klein & Washington, under review-a), the present authors believe that the present research and those other papers provide a fairly good overview of many of the main issues that are thwarting HIV educators’, HIV prevention specialists’, and HIV intervention-ists’ efforts to promote PrEP to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

Methods

Sample

This research was a pilot study, undertaken in anticipation of a larger, future project examining the barriers to PrEP adoption among MSM. A purposive sampling approach was used to derive the final research sample. By choosing this methodological approach, the principal goal was to assemble as diverse a sample of MSM as possible. In this manner, the analysis allows for the examination of differences among subgroups of MSM – for example, Caucasians versus African-Americans versus Latinos, or younger men versus older men – by virtue of each subgroup’s representation in the final sample. Typically, it is this quality of purposive sampling that is cited as one of its greatest strengths and most advantageous uses (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006; Palys, 2008; Patton, 1990), along with the fact that, when implemented properly, it yields results that are comparable to more-scientifically-sound methodological approaches even though purposive sampling itself is a nonrandom sampling approach (Tongco, 2007).

For this study, which was conducted between November 2017 and June 2018, 273 men were recruited via four distinct yet strategically-chosen approaches. The first recruitment strategy entailed approaching men participating in a few different social/activities/support groups for MSM and asking them to take part in the study. The second strategy involved a research assistant asking men attending a local Gay Pride event if they would be willing to take part in the study. The third approach entailed posting a profile on one particular dating/sex site targeting MSM of all ages and racial/ethnic groups, logging onto that website, and sending a generic “hello” type of message to initiate a casual conversation with anyone who visited the profile while the researcher was logged on. Finally, the fourth recruitment approach consisted of asking participants enrolled in the study via any of the first three methods to speak with friends and acquaintances of theirs, to see if they could get some of them to take part in the study (i.e., snowball sampling). The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board at California State University–Long Beach.

Procedures

Would-be participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study and were asked if they remained interested in participating. For those men who were enrolled in the study via one of the face-to-face methods of recruitment, verbal informed consent was provided before the questionnaire was administered. For men who were enrolled in the study via one of the electronic recruitment methods, acknowledgment of their willingness to participate in the research via email was obtained before a copy of the questionnaire was sent to them for completion. The questionnaire took approximately 15 minutes to complete and no compensation was offered. The survey instrument consisted of a few brief sections. Basic demographic information was collected in one section. In another, familiarity with PrEP and other PrEP users was examined, as was their level of interest in obtaining additional information about PrEP. Participants were asked about their likelihood of availing themselves of various types of sources for obtaining additional information about PrEP. In the final of the questionnaire, items comprising the PrEP Obstacles Scale and the PrEP Stigma Scale were included.

The PrEP Obstacles Scale measures the extent to which people perceive there to be various obstacles precluding them from giving more serious consideration to the adoption of PrEP medication. It is comprised of 20 items and has been shown to be reliable when used among MSM (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96), including a variety of demographic subgroups of MSM (Cronbach’s alpha ≥0.84 for all subgroups) (Klein & Washington, under review-b). The PrEP Stigma Scale measures the extent to which people associate various aspects of stigma to the use of PrEP and/or to actual PrEP users. It is comprised of 22 items and has been shown to be reliable when used among MSM (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96), including a variety of demographic subgroups of MSM (Cronbach’s alpha ≥0.88 for all subgroups) (Klein & Washington, 2019a,b).

Participants who were given the opportunity to answer the questionnaire in the presence of the research assistant (1) were instructed to find a place in the meeting facility or at the Pride festival where they felt comfortable and sufficiently private, (2) completed their survey manually, and (3) then handed their completed answer sheet in an unmarked, sealed envelope to that individual when they were done. Those who came to the project via contact referrals or from the dating/sex website were asked to email their completed answer sheet (or a photograph or scanned copy of their completed answer sheet) to a project-sponsored email account. Participants were told that their identity would remain private and that their answers and email addresses (used for returning completed answer sheets to the research team) would be kept confidential and would not be shared with anyone else. When they had submitted their completed answer sheet to the appropriate member of the research team, men were thanked for their time and participation, and then asked to contact other potentially-eligible and potentially-interested MSM they knew to help expand the sample. Respondents were not asked for their name, telephone number, email address, or any other personally-identifying information so that their participation could be as private and confidential as possible.

Measures

Demographic information collected in the questionnaire consisted of age (continuous), race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African-American, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or biracial/multiracial), relationship status (single, engaged or seriously involved with someone, married or involved in a long-term relationship), educational attainment (ordinal), sexual orientation (self-reported as gay, bisexual, or heterosexual), and HIV serostatus (self-reported as HIV-negative, HIV-positive, or serostatus unknown).

Knowledge of and Interest in PrEP consisted of individual items asking whether or not men had ever heard of PrEP prior to participating in this study (yes/no), whether or not they personally knew any PrEP users (yes/no), and how accurate their understanding of PrEP was prior to participating in the study once they were given a project-provided explanation of what PrEP is (five-point ordinal measure, ranging from “not at all accurate” to “very accurate”).,

Interest in Learning More about PrEP was assessed by asking men a single question about how interested they were right now in learning more about PrEP (five-point ordinal measure, ranging from “not at all interested” to “very interested”). Then, six separate questions were asked about how likely men thought they were to seek additional information about PrEP sometime during the next three months by (1) speaking with their friends, (2) asking their healthcare provider or personal physician, (3) visiting websites or watching podcasts, (4) going to the local health department, (5) reading postings on social media sites, or (6) contacting people on sex or dating websites or phone apps. Responses to these five-point ordinal items ranged from “not at all likely” to “very likely.” These items were also combined to construct the PrEP Resources Scale, which was found to be reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). Participants were also asked one question about how likely they thought they were to ask their personal physician to prescribe PrEP medication for them sometime within the next three months (five-point ordinal responses, ranging from “not at all likely” to “very likely”).

Analysis

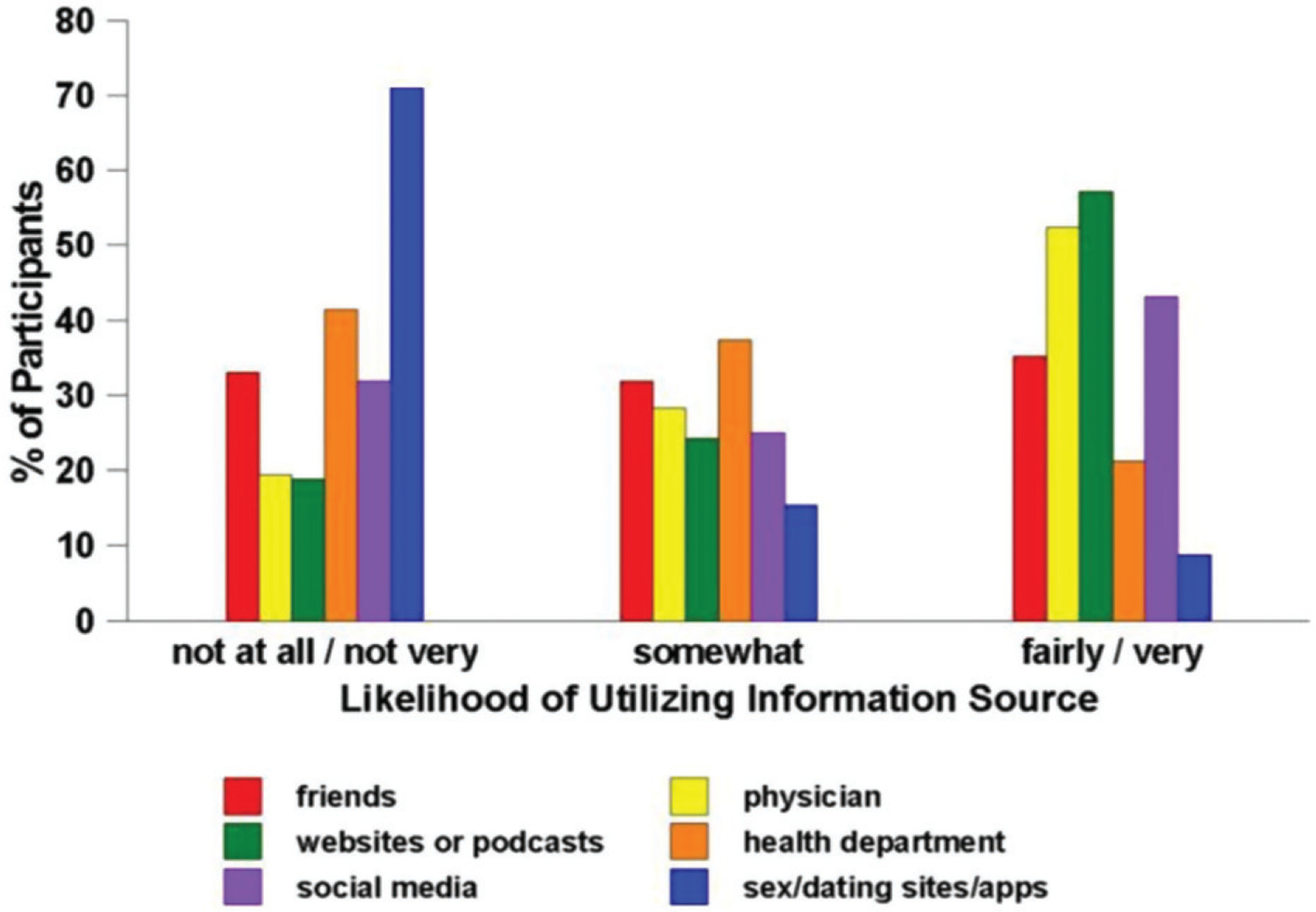

The Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), version 9.3, was used to perform all analytical functions. For the sake of simplicity in understanding the data, to ensure adequate statistical power to undertake the intended analyses, and for analytical purposes, responses to the individual items were collapsed into two categories, combining “not at all likely” and “not very likely” into the first grouping and “somewhat likely” and “fairly likely” and “very likely” into the second grouping (Figure 1). (The first two categories were combined because they indicate differing degrees of a negative response to the questions/items at hand, whereas the last three categories were combined because they indicate varying degrees of a positive response to the questions/items at hand.) To foster easy-to-understand intergroup comparisons in the statistical analyses, all of the demographic variables were recoded into dichotomous measures (e.g., Caucasian versus non-White, African-American versus nonblack, Latino versus non-Latino, single versus “involved,” HIV-positive versus HIV-negative, aged 18–39 years versus aged 40 or older, less than a high school degree versus more education, at least a college education versus less education). Odds ratios (OR) were used as the primary analytical tool, with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) reported for each point estimate. Results are reported as statistically significant whenever p < .05.

Figure 1.

Willingness to utilize various sources of information about PrEP.

Results

Sample

The purposive sampling approach was highly effective at deriving a diverse research sample, consisting of 273 men. The sample ranged in age from 18 to 72 years, with a mean age of 34.4 (SD = 13.1). Nearly one-half of the participants were aged 18–29 years (48.7%), with another one-quarter of them being aged 30–39 years (23.4%) and the remainder (28.8%) were 40 years or older. Slightly more than one-third of the participants were Caucasian (37.0%), with African-Americans (27.1%) and Latinos (18.3%) comprising the two next-largest groups. The remaining 17.6% of the sample was comprised of Asians and Pacific Islanders (8.8%), Native Americans or Native Alaskans (1.5%), and men who self-identified as biracial or multi-racial (7.3%). Most of the men self-identified as gay (69.6%) but there was excellent representation as well from bisexual men (16.1%) and MSM who self-identified as heterosexual (14.3%). The large majority of the participants (80.6%) said that they were single and not involved in a steady relationship with anyone, compared to 8.8% who said that they were seriously dating or engaged to someone and 10.6% who said that they were married. The large majority of the respondents (82.1%) said that they were HIV-negative at the time of interview. Approximately 1 man in 9 (11.0%) said that he had not completed high school or earned a G.E.D. This compares to 37.0% who had graduated from high school or earned a G.E.D., 34.1% who had some college education without the completion of a bachelor’s degree program, 8.4% who had completed college, and 9.5% who had earned either a master’s degree or a doctoral-level degree.

Lack of interest in learning more about PrEP

Most (71.7%) of the men said that they would be interested in finding out more about PrEP. Men who reported already being aware of PrEP before taking part in the present study were significantly less likely to be interested in learning more about PrEP than were their counterparts who were finding out about PrEP for the first time. A sizable majority (82.6%) of the former said that they were “fairly interested” or “very interested” in learning more about PrEP, compared to 43.3% of the latter (p < .0001). Conversely, only 3.7% of the men who previously were unaware of PrEP said that they were “not at all interested” or “not very interested” in learning more about it, compared to 32.9% of those who already were aware of PrEP (p < .0001).

Interest in learning more about PrEP was not equal across demographic comparison groups. For example, Caucasian men were much more likely than others to say that they were “not at all” or “not very” interested in finding out more about PrEP (23.0 versus 6.4%; OR = 4.37, CI95 = 2.03–9.42, p < .0001). HIV-negative men were considerably less likely than their HIV-positive and serostatus-unknown counterparts to say that they were “not at all” or “not very” interested in learning more about PrEP (5.4 versus 44.9%; OR = 0.07, CI95 = 0.03–0.16, p < .0001). Men aged 40 or older were much more likely than their younger counterparts to say that they were “not at all” or “not very” interested in learning more about PrEP (33.3 versus 4.6%; OR = 10.44, CI95 = 4.59–23.79, p < .0001). Men who had completed no more than a high school education were less likely than their better-educated counterparts to say that they were “not at all” or “not very” interested in learning more about PrEP (6.1 versus 18.4%; OR = 0.29, CI95 = 0.13–0.66, p = .002) and, conversely, those with at least a college degree were much more likely than their less-well-educated counterparts to express a low level of interest in finding out more about PrEP (22.9 versus 10.3%; OR = 2.60, CI95 = 1.17–5.78, p = .016). Interest in finding out more about PrEP did not differ based on men’s relationship status (p = .272) or sexual orientation (p = .518).

Lack of willingness to utilize information sources

Scores on the PrEP Resources Scale indicate that overall levels of willingness to avail oneself of potential information about PrEP were, at best, moderate. More than one-quarter of the men (26.0%) scored below 1.5 on the 0–4 scale, and 32.2% scored above a 2.5 on the scale. Men were most inclined to say that, in the next 3 months, they thought they were “not at all likely” or “not very likely” to seek PrEP information by speaking with other men on a sex or dating website or phone app (75.8%), followed by paying a visit to their local health department (41.4%), speaking with their friends (33.0%), and consulting social media sites (31.9%). In contrast, they were much more likely to say that they were “fairly likely” or “very likely” to seek PrEP information within the next three months from online sources or podcasts (57.1%) or by speaking with their personal physician (52.4%).

Comparisons amongst key demographic groups yielded numerous differences in men’s willingness to avail themselves of various resources of information about PrEP. (Table 1 presents detailed data about these intergroup differences.) Consider, for example, the case of the single most promising information source for the men in this sample: online sources or podcasts. Compared to their nonwhite peers, Caucasian men were much less likely to say that they would be “fairly likely” or “very likely” to look for PrEP information online during the next three months (40.6 versus 66.9%; OR = 0.34, CI95 = 0.20–0.56, p < .0001). Compared to their HIV-positive or serostatus-unknown counterparts, HIV-negative men were much more likely to indicate a high level of likelihood of going online in the near future for additional information about PrEP (66.1 versus 16.3%; OR = 9.98, CI95 = 4.45–22.36, p < .0001). In contrast, men aged 40 or older were much less apt than their younger peers to say that they would be “fairly likely” or “very likely” to seek PrEP-related information online in the near future (31.6 versus 67.0%; OR = 0.23, CI95 = 0.13–0.40, p < .0001). Men with at least a college education were substantially less apt than their not-as-well-educated peers to indicate a high chance of seeking PrEP information via online sources (32.7 versus 62.5%; OR = 0.29, CI95 = 0.15–0.56, p = .0001).

Table 1.

Interest in learning more about PrEP*, by demographic subgroups.

| Demographic group | Overall | Friends | Physician or healthcare provider | Online resources | Health department | Social media websites | Sex/dating websites or phone apps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| 18–39 | 17.7, 35.5 | 28.4, 36.6 | 9.1, 57.4 | 9.1, 67.0 | 36.0, 22.3 | 23.4, 51.3 | 76.7, 9.6 |

| 40–49 | 56.6, 11.3 | 52.8, 25.4 | 58.5, 26.4 | 54.7, 18.9 | 62.3, 9.4 | 62.3, 7.5 | 71.7, 5.7 |

| Race | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| Caucasian | 35.6, 24.7 | 39.6, 29.7 | 34.7, 41.6 | 33.7, 41.6 | 47.5, 22.8 | 47.5, 33.6 | 74.3, 5.9 |

| African-American | 21.6, 35.1 | 31.1, 36.5 | 9.5, 52.7 | 14.9, 66.2 | 36.5, 24.3 | 27.0, 47.3 | 73.0, 6.8 |

| Latino | 18.0, 40.0 | 24.0, 38.0 | 6.0, 64.0 | 6.0, 70.0 | 36.0, 16.0 | 18.0, 52.0 | 84.0, 6.0 |

| All others | 20.8, 35.4 | 31.3, 41.7 | 16.7, 62.5 | 6.3, 64.6 | 41.7, 18.7 | 20.8, 47.9 | 75.0, 12.5 |

| HIV Serostatus | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| HIV-negative | 17.9, 34.8 | 28.6, 33.0 | 9.4, 58.9 | 10.7, 66.1 | 35.3, 22.3 | 25.5, 48.2 | 77.2, 8.0 |

| HIV-positive | 63.3, 20.4 | 57.1, 26.2 | 66.7, 20.0 | 61.9, 14.3 | 73.8, 11.9 | 61.9, 16.7 | 71.4, 14.3 |

| Education | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| ≤High school | 16.0, 39.7 | 31.3, 35.1 | 8.4, 56.5 | 10.7, 68.7 | 28.2, 22.9 | 18.3, 56.5 | 77.1, 10.7 |

| Some college | 25.8, 28.0 | 28.0, 33.3 | 20.4, 54.8 | 19.4, 53.8 | 48.4, 19.3 | 41.9, 36.6 | 67.7, 9.7 |

| ≥College graduate | 53.1, 20.4 | 46.9, 38.8 | 46.9, 36.7 | 38.8, 32.6 | 63.3, 20.4 | 49.0, 20.4 | 87.8, 2.0 |

| Relationship status | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| Single | 21.8, 33.6 | 30.5, 36.4 | 15.0, 54.1 | 15.5, 58.6 | 36.4, 20.9 | 30.5, 45.0 | 72.7, 9.1 |

| “Involved” | 43.4, 18.1 | 43.4, 30.2 | 37.7, 45.3 | 32.1, 50.9 | 62.3, 22.6 | 37.7, 35.8 | 88.7, 7.5 |

| Sexual orientation | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High | Low, High |

| Gay | 27.4, 34.7 | 31.1, 37.4 | 20.0, 51.6 | 19.0, 57.9 | 43.2, 20.5 | 32.6, 44.2 | 74.7, 9.5 |

| Bisexual | 11.4, 27.3 | 34.1, 25.0 | 13.6, 54.5 | 9.1, 65.9 | 25.0, 22.7 | 22.7, 47.3 | 75.0, 9.1 |

| Heterosexual | 35.9, 24.6 | 41.0, 35.9 | 23.1, 53.8 | 28.2, 43.6 | 51.3, 23.1 | 38.5, 33.3 | 82.1, 5.1 |

In each item, the first number reports the percentages of men who were “not at all likely” or “not very likely” (labeled “Low”), whereas the second number reports the percentages of men who were “fairly likely” or “very likely” (labeled “High”) to utilize the specific resource within the next 3 months in order to obtain additional information about PrEP.

As another example we shall consider a case from the other end of the spectrum – that is, a potential information source not generally deemed to be viable by the men in this study – focusing on obtaining information about PrEP from the local health department. Here, too, we found many intergroup differences. Single men were much less likely than their peers who were married, engaged, or in a dating relationship to say that they would be unlikely to seek PrEP information from the local health department during the foreseeable future (36.4 versus 62.3%; OR = 0.35, CI95 = 0.19–0.64, p = .0006). Likewise, HIV-negative men were also much less likely than their HIV-positive or serostatus-unknown counterparts to perceive themselves as unlikely to seek PrEP information from a local health department (35.3 versus 69.4%; OR = 0.24, CI95 = 0.12–0.47, p < .0001). In contrast, men aged 40 years or older were considerably more likely than their younger counterparts to say that they thought it unlikely that they would go to a local health department in the near future for information about PrEP (55.3 versus 36.0%; OR = 2.19, CI95 = 1.28–3.75, p = .004). Men with more than a high school education were significantly less likely than their better-educated peers to say that they would not turn to the local health department sometime soon for PrEP-related information (28.2 versus 53.5%; OR = 0.34, CI95 = 0.21–0.57, p < .0001).

Discussion

Limitation of the study

Before discussing the implications of this research, we would like to acknowledge the main limitation of this study: The findings presented in this paper are based on a research sample that was not derived via random sampling. Instead, the data were collected via a purposive sampling approach that was designed to maximize diversity within the target population, so that analyses could be performed with different subpopulations of MSM fostering comparisons of men based on their age, race, educational attainment, and so forth. The adoption of the purposive sampling approach successfully accomplished this goal, while making it impossible for us to know the extent to which these findings may or may not be generalized to MSM in general.

Conclusions

We set out at the beginning of this paper to examine two specific aspects of the question of why more MSM are not using PrEP than currently is the case, specifically focusing on men’s (lack of) interest in learning more about PrEP and their (lack of) willingness to avail themselves of various information sources that could help them to become more informed about PrEP. Despite the study limitation outlined above, we believe that the results of this pilot study offer several insights into this issue.

First, more than one-quarter of the men who participated in this study expressed a relatively low level of interest or no interest at all in learning more about PrEP. This is concerning, considering that PrEP adoption is currently the foundation of our country’s efforts to curtail the spread of HIV (Office of National AIDS Policy, 2015). More needs to be learned about why it is that so many men who have sex with men are as disinterested as they seem to be in learning more about a medication such as PrEP that can keep them safe from HIV.

This is particularly true when one considers the fact that men who are already HIV-infected or who are unaware of their HIV serostatus were among the groups least interested in learning more about PrEP. Men who are unaware of their HIV serostatus, presumably due to a lack of recent HIV testing, are especially in need of targeted intervention efforts. How to reach these men effectively with PrEP information is likely to be quite challenging, though, in light of the fact that they, as a group, are less interested in learning more about PrEP than their known-to-be-HIV-negative counterparts. Research has shown that HIV risk behavior involvement and/or willingness to consider using PrEP tends to be greater among MSM who have never been tested or who have not been tested recently for HIV (Alexovitz et al., 2018; Grov, Whitfield, Rendina, Ventuneac, & Parsons, 2015). Findings from the present pilot study are consistent with those studies and they highlight the need to develop creative and effective PrEP-related education and prevention messages specifically targeting this population.

Additionally, men aged 40 years and older were less interested in learning more about PrEP than their younger counterparts is also of great concern. Other research conducted by one of the present authors (Klein, 2012) showed that older MSM were just as likely as their younger counterparts to be sexually active and that they engaged in comparably-high rates of risky sexual behaviors. Additionally, 33.4% of all people diagnosed with HIV in the most recent reporting year were aged 40 years or older (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). Among adults aged 50 and older, the CDC reports that 49% of all new HIV diagnoses occurred among MSM (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). Also worth noting: between 2002 and 2017, the proportion of all newly-diagnosed cases of HIV among people aged 50 or older has risen steadily from 15.9% (2002) to 16.4% (2007) to 16.9% (2012) to 17.1% (2017) (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2002, 2007, 2017a). Clearly, age is not a protective factor when it comes to the need for information about how to remain safe from HIV transmission. Developing an age-appropriate educational initiative to provide information about PrEP to older adults would be wise—seemingly more so now than ever before, given the slow but steady growth of HIV infection rates in this population. Other researchers have commented on the need for age-appropriate HIV messaging and education/prevention/intervention initiatives targeting older adults (Foster, Clark, Holstad, & Burgess, 2012; McCord, 2014; Orel, Spence, & Steele, 2005), and the present study’s findings are consistent with those researchers’ recommendations.

Another important finding emanating from the present research is that, overall, the men who participated in this study did not deem most potential sources for additional information about PrEP to be viable or attractive to them. Slightly more than one-half of the respondents indicated that they thought that it was likely that they would speak with their personal physician and/or look online for information about PrEP during the 3 months following their interview. All other ways of obtaining PrEP-related information that was examined in conjunction with this research were endorsed by substantially fewer men. Thus, another big challenge that HIV researchers need to overcome is how to go about making PrEP information available to and palatable to MSM who, generally speaking, are uncomfortable with–if not resistant to–seeking this information via most currently-available methods of providing health information.

Complicating this situation is the fact that different “types” of men (based on their demographic characteristics) deemed different ways of receiving additional information about PrEP to be more/less viable for them than others. No consistent patterning of results was identified here – that is, there was no evidence that Caucasian men were, as a group more/less resistant to seeking PrEP-related information than their nonwhite peers, or that older men were more/less willing than their younger counterparts to seek information about PrEP, or that comparable patterns existed for men based on their educational attainment or HIV serostatus or relationship status. Thus, what remains is a complex situation wherein certain population subgroups deem information sources X or Y to be the most/least viable whereas other subgroups deem information sources A or B to be more/less viable to them. Disentangling this web of which approaches to providing PrEP information to which “types” of MSM, and under what circumstances and in what fashion(s) this information can be provided most effectively, would be a fruitful way for future researchers to advance knowledge in this area. It seems likely to the present authors, though, that the complicated nature of these “which types of men want which types of information to be provided to them via which methods” conundrums is playing at least a fairly-consequential role in the overall equation as to why more MSM have not adopted PrEP and are not giving serious consideration to adopting PrEP as part of their personal strategy to avoid contracting HIV.

Summary

This paper has provided evidence to demonstrate that another piece of the puzzle as to why more MSM are not using PrEP–namely that, as a group, they are not very interested in obtaining additional information about PrEP. Moreover, most sources of receiving PrEP-related information were deemed unappealing by the majority of the men who participated in the study. Thus, the nature of the overall problem becomes a bit clearer now: Not only are many MSM unaware of PrEP and unfamiliar with anyone who has used it, but also, oftentimes, they are resistant to learning more about it and uncomfortable (or unwilling, or both) with various methods of seeking additional information about PrEP. Much more work needs to be done in order to understand how to spread the word about PrEP and its efficacy throughout the MSM community, how to make receiving information about PrEP more palatable to this population, and how to address concerns about PrEP-related stigma and the barriers that many MSM perceive there to be preventing them from pursuing the adoption of PrEP personally.

Footnotes

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Alexovitz KA, Merchant RC, Clark MA, Liu T, Rosenberger JG, Bauermeister J, & Mayer KH (2018). Discordance of voluntary HIV testing with HIV sexual risk-taking and self-perceived HIV infection risk among social media-using black, Hispanic, and white young-men-who-have-sex-with-men (YMSM). AIDS Care, 30(1), 81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratcher A, Wirtz SS, & Siegler AJ (2018). Users of a national directory of PrEP service providers: Beliefs, self-efficacy, and progress toward prescription. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 78(4), e28–e30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, & Leibowitz AA (2011). Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care, 23(9), 1136–1145. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Landovitz RJ, Regan R, Lee SJ, & Allen VC Jr. (2015). Perceptions of and intentions to adopt HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. International Journal of STD & Aids, 26(14), 1040–1048. doi: 10.1177/0956462415570159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Underhill K, Earnshaw VA, Hansen NB, Kershaw TS, Magnus M, … Dovidio JF (2016). Framing HIV pre-exposure prophylasix (PrEP) for the general public: How inclusive messaging may prevent prejudice from diminishing public support. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1499–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2002). HIV/AIDS surveillance report 2002 (Volume 14, pp. 1–50). Atlanta, GA: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). HIV/AIDS surveillance report 2007 (Volume 19, pp. 1–63). Atlanta, GA: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). HIV surveillance report, 2015 (Volume 27, pp. 1–114). Atlanta, GA: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). Basic statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017a). HIV/AIDS surveillance report 2017 (Volume 29, pp. 1–129). Atlanta, GA: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017b). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). HIV among people aged 50 and older. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html.

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, & Maksut J (2017). Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among black and white men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1236–1246. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1690-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Matthews DD, Driffin DD, Bukowski L, Wilson PA, & Stall RD (2017). A multi-U.S. city assessment of awareness and uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among black men and transgender women who have sex with men. Prevention Science, 18(5), 505–516. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0756-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon SA, Park JN, Ogbue CP, Flynn C, & German D (2017). Awareness and acceptability of pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Baltimore. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1268–1277. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1619-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster V, Clark PC, Holstad MM, & Burgess E (2012). Factors associated with risky sexual behaviors in older adults. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 23(6), 487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, … Glidden DV (2014). Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. The Lancet: Infectious Diseases, 14(9), 820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Whitfield THF, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, & Parsons JT (2015). Willingness to take PrEP and potential for risk compensation among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 19(12), 2234–2244. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1030-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, & Johnson L (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H (2012). A comparison of HIV risk practices among unprotected sex-seeking older and younger men who have sex with other men. The Aging Male, 15(3), 124–133. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2011.646343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, & Washington TA (under review-a). Why more men who have sex with men are not using PrEP–The roles played by perceived stigma and perceived obstacles to PrEP use.

- Klein H, & Washington TA (under review-b). The Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Obstacles Scale: Preliminary findings from a pilot study. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Klein H, & Washington TA (2019a). Understanding why more men who have sex with men (MSM) are not using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication: Results from a pilot study. Advances in Health and Disease, 10, 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, & Washington TA (2019b). The Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Stigma Scale: Preliminary findings from a pilot study. International Public Health Journal, 11, 185–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O, Wu E, Levine EC, Muñoz-Laboy M, Fernandez MI, Bass SB, … Rhodes SD (2016). Integration of social, cultural, and biomedical strategies into an existing couple-based HIV/STI prevention: Voices of Latino male couples. PLoS One, 11(3), e0152361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord LR (2014). Attention HIV: Older African American women define sexual risk. Culture, Health, and Sexuality, 16(1), 90–100. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.821714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Ghani MA, Nogg K, Winder TJA, & Soto JK (2015). Getting prepared for HIV prevention navigation: Young black gay men talk about HIV prevention in the biomedical era. AIDS Patient Care and Stds, 29(9), 490–502. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAM Publications. (2017). How effective is PrEP? Retrieved from http://www.aidsmap.com/How-effective-is-PrEP/page/2983351.

- Office of National AIDS Policy (2015). National HIV/AIDS strategy: Updated to 2020. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Orel NA, Spence M, & Steele J (2005). Getting the message out to older adults: Effective HIV health education risk reduction publications. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 24(5), 490–508. doi: 10.1177/0733464805279155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palys T (2008). Purposive sampling. In: Given LM (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 697–698). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield THF, Starks TJ, & Grov C (2017). Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States: The motivational PrEP cascade. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 74(3), 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd edition). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott S (2013). Social justice, public health ethics, and the use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(1), s137–s140. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolle C-P, Rosenberg ES, Siegler AJ, Sanchez TH, Luisi N, Weiss K, … Kelley CF (2017). Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young black MSM. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 76(3), 250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman S (2017a). Prevention efforts and PrEP disparities. IDWeek 2017 HIV Science Review Retrieved from http://www.thebodypro.com/content/80480/idweek-2017-hiv-science-preview.html?ic=sanext.

- Salzman S (2017b). PrEP prescriptions rise sharply, but unequally, in New York City. IDWeek 2017 HIV Science Review http://www.thebodypro.com/content/80497/prep-prescriptions-rise-sharply-but-unequally-in-n.html.

- Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, McCallister S, Yeung H, Jones J … Sullivan PS (2018). Distribution of active PrEP prescriptions and the PrEP-to-need ratio, US, Q2 2017 (abstract 1022LB). Paper presented at Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Tongco DC (2007). Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 5, 147–158. doi: 10.17348/era.5.0.147-158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitski R (2018). PrEP prescription on the rise: But more work remains. Retrieved from https://blackaids.org/blog/prep-prescriptions-rise-work-remains.