Abstract

Background

CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), the receptor for CCL22 and CCL17, is expressed on the surface of effector Tregs that have the highest suppressive effects on antitumor immune response. CCR4 is also widely expressed on the surface of tumor cells from patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Mogamulizumab is a humanized, IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody that is directed against CCR4. By reducing the number of CCR4-positive Tregs and tumor cells, the mogamulizumab can reduce tumor burden and boost antitumor immunity to achieve antitumor effects.

Methods

We examined the PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov until 1 February 2020. Considering variability in different studies, we selected the adverse events (AEs), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective responses rate (ORR) and Hazard Ratio (HR) for PFS to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of mogamulizumab.

Results

When patients were treated with mogamulizumab monotherapy, the most common all-grade AEs were lymphopenia, infusion reaction, fever, rash and chills while the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs were lymphopenia, neutropenia and rash. When patients were treated with combined therapy of mogamulizumab and other drugs, the most common all-grade AEs were neutropenia, anaemia, lymphopenia and gastrointestinal disorder, while the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs was lymphopenia. For patients treated with mogamulizumab monotherapy, the pooled ORR and mean PFS were 0.430 (95% CI: 0.393–0.469) and 1.060 months (95% CI: 1.043–1.077), respectively. For patients treated with combined therapy of mogamulizumab and other drugs, the pooled ORR was 0.203 (95% CI: 0.022–0.746) while the pooled PFS and OS were 2.093 months (95% CI: 1.602–2.584) and 6.591 months (95% CI: 6.014–7.167), respectively.

Conclusions

Based on present evidence, we believed that mogamulizumab had clinically meaningful antitumor activity with acceptable toxicity which is a novel therapy in treating patients with cancers.

Keywords: Mogamulizumab, Malignant lymphoma, Solid tumors, CCR4, Meta-analysis

Background

CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) is the receptor for two CC chemokine ligands (CCLs)- CCL22 (also called macrophage-derived chemokine) and CCL17 (thymus activation-regulated chemokine) [1]. By binding with its ligands, CCR4 is implicated in lymphocyte trafficking to the skin and migration of CCR4-positive Tregs [2–4]. CCR4 is predominantly expressed on the surface of effector Tregs that have the highest suppressive effects on antitumor immune response. CCR4 is also widely expressed on surface of tumor cells of most patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and is selectively expressed in approximately 40% of patients with other subtypes of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) [5–10]. Mogamulizumab (also named as KW-0761, poteligeo) is a humanized, IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody that is directed against CCR4 [10–12]. Previous studies have demonstrated that mogamulizumab can highly enhance antitumor effects by reducing CCR4-positive leukemic cells and inducing Tregs depletion [1]. So far, a series of phase I/II/III trials on mogamulizumab for various cancers have been completed. From these trials, we suppose that cancer patients treated with mogamulizumab can achieve significant treatment responses. We also focus on the adverse events of mogamulizumab or mogamulizumab-related therapies. However, there is no evidence-based systematic review on the safety and efficacy of mogamulizumab in treating patients with cancer. It is urgent and important to summarize those results, offering evidence-based references to direct clinical decisions. In this meta-analysis, we focus on the safety and efficacy of mogamulizumab in the treatment of various cancers based on selected clinical trials.

Methods

Literature search and selection

We followed the guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) to complete the meta-analysis. The trials were identified through PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov without any language restrictions until 1 February 2020. The keywords included “KW-0761”, “mogamulizumab” and “poteligeo”. After duplicates eliminating, two authors screened the studies independently. When there were disagreements, we referred to the opinions of a third author. Full texts of selective trials were downloaded and assessed in strict accordance with the following criteria for eligibility. Additionally, we screened the references of selected trials for potentially relevant trials.

Inclusion and excluded criteria

All eligible studies had to satisfy the following criteria: (i) the studies were clinical trials containing the efficacy or safety data of mogamulizumab or mogamulizumab-related therapies; (ii) the patients enrolled in these trials were suffering from cancers; (iii) the studies reported any of the following information: adverse events (AEs), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), objective responses rate (ORR), and Hazard Ratio(HR) for PFS; (iiii) the studies used mogamulizumab as a single drug or in combination with other drugs. The exclusion criteria were: (i) the studies were not clinical trials; (ii) the studies lacked available data or the full texts were inaccessible.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two authors and disagreements were adjudicated by a third author. In this meta-analysis, we extracted basic information including first author’s name, clinical trial registration number, year, study phase, total number of patients, gender, age, treatment regime, tumor type and assessment. The AEs (all grades and grades ≥3), OS, PFS, ORR and HR for PFS were needed to assess the efficacy and safety of mogamulizumab. For safety endpoints, the data we extracted from the eligible trials were grade ≥ 3 and all-grade AEs according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). For efficacy endpoints, we collected the OS and PFS directly in each included study while we collected the ORR directly or calculated based on the accessible data. The HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) for PFS were extracted following Wan’s method [13].

Results

Study selection

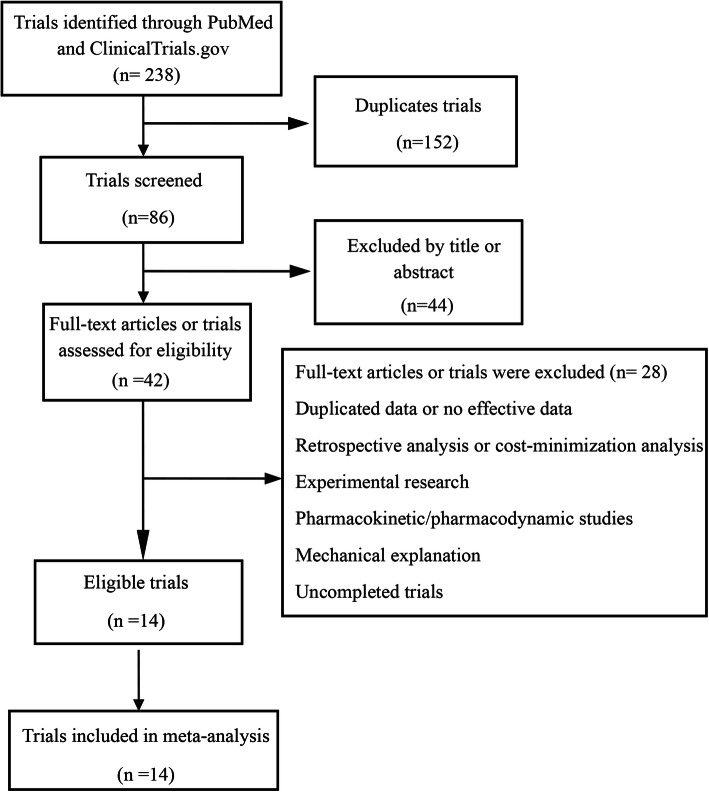

Through a comprehensive search, we found 213 articles in PubMed and 7 trials in ClinicalTrials.gov. After duplicate, there were 73 articles and 1 trial left. By screening the titles and abstracts, we excluded 44 articles on the basis of exclusion criteria. Then we viewed the full texts of remained studies, and finally, 13 articles and 1 trial were involved according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria [14–27]. The overall filter procedures and results were shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature selection for systemic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA)

Study characteristics

The basic information of eligible studies was listed on Table 1. The trials were conducted from 2010 to 2019, including 5 phase I trials, 1 phase I-II trial, 6 phase II trials, 1 phase III trial and 1 unspecified trial. Among them, patients in 2 phase I trials administered mogamulizumab intravenously at a dose of 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 mg/kg [18, 22]. Patients in 3 phase I trials and 2 phase II trials received mogamulizumab in combination with other drugs [16, 24–27]. And the rest received mogamulizumab monotherapy at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg [14–17, 19–21, 23]. There were total 1290 patients enrolled in these studies, including patients with ATL, PTCL, CTCL, ect.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included trials

| First author | Clinical trial registration number | Year | Phase | Sample size | Gender | Age | Treatment | Disease | Assessment (Response) | Assessment (AE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||||

| Yamamoto, K. | NCT00355472 | 2010 | I | 16 | 8 | 8 | 62 (46–69) | mogamulizumab | relapsed CCR4+ ATL or PTCL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Ishida, T. | NCT00920790 | 2012 | II | 27 | 12 | 15 | 64 (49–83) | mogamulizumab | relapsed CCR4+ ATL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Ogura, M. | NCT01192984 | 2014 | II | 37 | 23 | 14 | 64 (33–80) | mogamulizumab | relapsed CCR4+ PTCL or CTCL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Duvic, M. | NCT00888927 | 2015 | I-II | 41 | 24 | 17 | 66 (35–85) | mogamulizumab | CTCL or PTCL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Ishida, T. | NCT01173887 | 2015 | II | 53 | 28 | 25 | – | mLSG15 + mogamulizumab or mLSG15 | aggressive ATL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Kurose, K. | NCT01929486 | 2015 | I | 10 | – | – | – | mogamulizumab | LC or EC | RECIST | CTCAE |

| Zinzani, P. L. | NCT01611142 | 2016 | II | 38 | 23 | 15 | 58.5 (19–87) | mogamulizumab | PTCL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Ishitsuka, K. | UMIN000025368 | 2017 | II | 484 | 258 | 226 | – | mogamulizumab or mogamulizumab with other drugs | ATL and others | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Kim, Y. H. | NCT01728805 | 2018 | III | 372 | 216 | 156 | 64.5 (54–73) | mogamulizumab or vorinostat | CTCL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Nakashima, J. | – | 2018 | – | 45 | 27 | 18 | 69 (43–89) | mogamulizumab | relapsed or refractory ATL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| Phillips, A. A. | NCT01626664 | 2018 | II | 34 | 37 | 71 | 53 (22–82) | mogamulizumab, pralatrexate, gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin or DHAP | ATL | RECIL | CTCAE |

| – | NCT02358473 | 2018 | I | 13 | 5 | 8 | – | mogamulizumab +docetaxel | NSCLC | RECIST | CTCAE |

| Doi, T. | NCT02476123 | 2019 | I | 96 | 72 | 24 | 63 (56–68) | mogamulizumab +nivolumab | NSCLC, SCLC, GC, EC, HCC, PA | RECIST | CTCAE |

| Cohen, E. E. W. | NCT02444793 | 2019 | I | 24 | 19 | 5 | 63.9 (53–75) | mogamulizumab +utomilumab | CRC, NSCLC, OC, SCCHN | RECIST | CTCAE |

Abbreviations: ATL adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma, PTCL peripheral T-cell lymphoma, CTCL cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, LC lung cancer, EC esophageal cancer, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, SCLC small cell lung cancer, GC gastric cancer, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, PA pancreatic adenocarcinoma, CRC colorectal cancer, OC ovarian cancer, SCCHN squamous cell cancer of head and neck, mLSG15 modified LSG15 regimen (VCAP-AMP-VECP: vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and prednisolone; doxorubicin, ranimustine and prednisolone; vindesine, etoposide, carboplatin and prednisolone), AE adverse events, RECIL Response Evaluation Criteria in Lymphoma, RECIST Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, CTCAE National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

Overall adverse events analysis

The safety data, grade ≥ 3 or all-grade AEs we extracted, were used to calculate the AEs rate to assess the safety of mogamulizumab. The details of the results were presented in Tables 2, 3. In all eligible trials administered mogamulizumab monotherapy, we divided these trials into low dose group (mogamulizumab≤0.1 mg/kg), medium dose group (0.5 mg/kg) and high dose group (1.0 mg/kg) in accordance with the dose. In low dose group, lymphopenia was the most common all-grade AEs and grade ≥ 3 AEs with the highest rate of 0.700 (95% CI: 0.375–0.900) and 0.401 (95% CI: 0.158–0.705), respectively. In medium dose group, the most common all-grade AEs were leukopenia and lymphopenia with the same rate of 0.875 (95% CI: 0.463–0.983) while leukopenia (0.767, 95% CI: 0.337–0.955) was the only grade ≥ 3 AEs. In high dose group, the common all-grade AEs were lymphopenia (0.805, 95% CI: 0.432–0.957), infusion reaction (0.607, 95% CI: 0.062–0.973), fever (0.472, 95% CI: 0.116–0.859), rash (0.407, 95% CI: 0.210–0.639) and chills (0.401, 95% CI: 0.129–0.751), while lymphopenia (0.648, 95% CI: 0.482–0.787) was the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs. The rest of all-grade and grade ≥ 3 AEs were happened relatively less. In the trials administered mogamulizumab in combination with other drugs, the most common all-grade AEs were neutropenia (0.812, 95% CI: 0.035–0.998), anaemia (0.687, 95% CI: 0.017–0.996), lymphopenia (0.619, 95% CI: 0.007–0.997) and gastrointestinal disorder (0.599, 95% CI: 0.001–0.999). The lymphopenia (0.568, 95% CI: 0.004–0.998) was the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs while other grade ≥ 3 AEs were relatively rare.

Table 2.

Summary results of the all-grade and grade ≥ 3 adverse events (AEs) in mogamulizumab monotherapy

| adverse events | All-grade | Grade ≥ 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | No. of Patients | model | Event rate with 95% CI | Z value | p value | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | model | Event rate with 95% CI | Z value | p value | |

| KW-0761 < =0.1 mg/kg | ||||||||||||

| Hematologic | ||||||||||||

| Lymphopenia | 2 | 10 | Fixed | 0.700 (0.375–0.900) | 1.224 | 0.221 | 2 | 10 | Fixed | 0.401 (0.158–0.705) | − 0.619 | 0.536 |

| Nonhematologic | ||||||||||||

| Fever | 2 | 10 | Fixed | 0.212 (0.052–0.569) | −1.618 | 0.106 | ||||||

| Rash | 2 | 10 | Random | 0.351 (0.045–0.860) | −0.497 | 0.619 | ||||||

| KW-0761 = 0.5 mg/kg | ||||||||||||

| Hematologic | ||||||||||||

| Leukopenia | 2 | 6 | Fixed | 0.875 (0.463–0.983) | 1.820 | 0.069 | 2 | 6 | Fixed | 0.767 (0.337–0.955) | 1.250 | 0.211 |

| Lymphopenia | 2 | 6 | Fixed | 0.875 (0.463–0.983) | 1.820 | 0.069 | ||||||

| Neutropenia | 2 | 6 | Fixed | 0.587 (0.181–0.902) | 0.370 | 0.711 | ||||||

| KW-0761 = 1.0 mg/kg | ||||||||||||

| Hematologic | ||||||||||||

| Anaemia | 5 | 316o | Random | 0.097 (0.040–0.216) | −4.626 | 0.000 | 3 | 122 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.025–0.119) | −6.720 | 0.000 |

| Leukopenia | 5 | 127 | Random | 0.310 (0.125–0.586) | −1.368 | 0.171 | ||||||

| Lymphopenia | 4 | 80 | Random | 0.805 (0.432–0.957) | 1.643 | 0.100 | 3 | 43 | Random | 0.648 (0.482–0.787) | 1.757 | 0.079 |

| Neutropenia | 6 | 165 | Random | 0.228 (0.104–0.431) | −2.543 | 0.011 | 5 | 155 | Fixed | 0.139 (0.087–0.213) | −6.915 | 0.000 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 149 | Random | 0.273 (0.131–0.483) | −2.108 | 0.035 | 4 | 149 | Fixed | 0.117 (0.071–0.185) | −7.311 | 0.000 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 3 | 90 | Fixed | 0.158 (0.096–0.249) | −5.743 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Vomiting | 2 | 80 | Fixed | 0.128 (0.107–0.154) | −5.617 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Nausea | 4 | 154 | Random | 0.147 (0.064–0.304) | −3.716 | 0.000 | 2 | 80 | Fixed | 0.039 (0.013–0.114) | − 5.436 | 0.000 |

| General disorders | ||||||||||||

| Chills | 2 | 69 | Random | 0.401 (0.129–0.751) | −0.522 | 0.602 | ||||||

| Fatigue | 2 | 89 | Random | 0.096 (0.024–0.312) | − 3.022 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Fever | 3 | 43 | Random | 0.472 (0.116–0.859) | −0.116 | 0.907 | ||||||

| Pyrexia | 5 | 348 | Random | 0.139 (0.062–0.283) | −4.002 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Headache | 3 | 127 | Random | 0.115 (0.046–0.259) | −4.048 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Infections and infestations | ||||||||||||

| Infection | 2 | 84 | Random | 0.081 (0.015–0.335) | −2.730 | 0.006 | 2 | 84 | Fixed | 0.084 (0.038–0.175) | −5.571 | 0.000 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | ||||||||||||

| Infusion reaction | 2 | 64 | Random | 0.607 (0.062–0.973) | 0.272 | 0.786 | ||||||

| Infusion-related reaction | 4 | 311 | Random | 0.135 (0.032–0.420) | −2.370 | 0.018 | ||||||

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders /investigations | ||||||||||||

| ALT | 4 | 121 | Random | 0.172 (0.063–0.391) | −2.731 | 0.006 | 3 | 111 | Fixed | 0.042 (0.016–0.107) | −6.107 | 0.000 |

| AST | 3 | 84 | Random | 0.167 (0.040–0.494) | −1.990 | 0.047 | 2 | 74 | Fixed | 0.049 (0.016–0.140) | −5.007 | 0.000 |

| Decreased appetite | 2 | 231 | Random | 0.017 (0.002–0.119) | −3.885 | 0.000 | ||||||

| CRP | 2 | 16 | Fixed | 0.128 (0.032–0.395) | −2.521 | 0.012 | ||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.108 (0.041–0.255) | − 3.983 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 2 | 33 | Fixed | 0.277 (0.150–0.453) | − 2.443 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Hyperuricemia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.137 (0.058–0.289) | −3.825 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypokalemia | 2 | 64 | Fixed | 0.083 (0.035–0.184) | −5.133 | 0.000 | 2 | 64 | Fixed | 0.053 (0.017–0.151) | −4.857 | 0.000 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 2 | 64 | Fixed | 0.156 (0.086–0.267) | − 4895 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypotension | 2 | 65 | Fixed | 0.139 (0.074–0.246) | −5.084 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Weight change | 2 | 74 | Random | 0.077 (0.008–0.447) | −2.143 | 0.032 | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||||||||||

| Polymyositis | 2 | 221 | Fixed | 0.012 (0.003–0.047) | −6.179 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Arthralgia | 2 | 222 | Random | 0.036 (0.004–0.278) | −2.767 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | ||||||||||||

| Hypoxemia | 2 | 33 | Fixed | 0.182 (0.084–0.350) | −3.330 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Pneumonia | 2 | 221 | Fixed | 0.023 (0.009–0.053) | −8.316 | 0.000 | 2 | 75 | Fixed | 0.042 (0.014–0.123) | −5.293 | 0.000 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||||||||||

| Pruritus | 4 | 113 | Fixed | 0.153 (0.097–0.232) | −6.497 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Rash | 4 | 88 | Random | 0.407 (0.210–0.639) | −0.782 | 0.434 | 3 | 48 | Fixed | 0.135 (0.074–0.234) | −5.423 | 0.000 |

| Rash maculopapular | 2 | 47 | Fixed | 0.101 (0.038–0.243) | −4.085 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Drug eruption | 3 | 269 | Random | 0.111 (0.022–0.412) | −2.365 | 0.018 | ||||||

Table 3.

Summary results of the all-grade and grade ≥ 3 adverse events (AEs) in combination therapies

| adverse events | All-grade | Grade ≥ 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | No. of Patients | model | Event rate with 95% CI | Z value | p value | No. of Studies | No. of Patients | model | Event rate with 95% CI | Z value | p value | |

| Hematologic | ||||||||||||

| Anaemia | 2 | 53 | Random | 0.687 (0.017–0.996) | 0.319 | 0.750 | ||||||

| Lymphopenia | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.619 (0.007–0.997) | 0.176 | 0.861 | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.568 (0.004–0.998) | 0.092 | 0.927 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 143 | Random | 0.248 (0.006–0.951) | −0.534 | 0.593 | ||||||

| Neutropenia | 2 | 42 | Random | 0.812 (0.035–0.998) | 0.600 | 0.549 | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 2 | 53 | Random | 0.599 (0.001–0.999) | 0.112 | 0.911 | ||||||

| Nausea | 3 | 127 | Random | 0.159 (0.046–0.425) | −2.393 | 0.017 | ||||||

| Vomiting | 3 | 127 | Random | 0.093 (0.032–0.242) | −3.945 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 2 | 103 | Fixed | 0.148 (0.091–0.231) | −6.240 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Stomatitis | 3 | 143 | Random | 0.185 (0.035–0.585) | −1.592 | 0.111 | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.046 (0.004–0.393) | −2.290 | 0.022 |

| General disorders | ||||||||||||

| Fatigue | 3 | 127 | Random | 0.278 (0.072–0.659) | −1.159 | 0.246 | ||||||

| Pyrexia | 3 | 143 | Random | 0.234 (0.017–0.844) | −0.810 | 0.418 | ||||||

| Chills | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.110 (0.042–0.260) | − 3.930 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Oedema peripheral | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | ||||||||||||

| Infusion related reaction | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.110 (0.042–0.260) | −3.930 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders /investigations | ||||||||||||

| AST increased | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.163 (0.036–0.501) | −1.956 | 0.050 | 2 | 119 | Fixed | 0.059 (0.028–0.119 | −7.103 | 0.000 |

| ALT increased | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.197 (0.030–0.663) | −1.325 | 0.185 | 2 | 119 | Fixed | 0.044 (0.019–0.102) | −6.696 | 0.000 |

| Hyponatraemia | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.060 (0.009–0.301) | −2.825 | 0.005 | 2 | 119 | Random | 0.032 (0.005–0.170) | −3.659 | 0.000 |

| Hyperuricaemia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypomagnesaemia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypophosphataemia | 2 | 53 | Fixed | 0.116 (0.053–0.236) | − 4.663 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Weight decreased | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.113 (0.043–0.265) | − 3.878 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Platelet count decreased | 2 | 103 | Fixed | 0.050 (0.021–0.114) | −6.436 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Decreased appetite | 3 | 143 | Random | 0.275 (0.031–0.817) | −0.769 | 0.442 | ||||||

| Dehydration | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.204 (0.099–0.373) | −3.166 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Hypotension | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.021 (0.005–0.082) | −5.334 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||||||||||

| Arthralgia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.113 (0.043–0.265) | −3.878 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Myalgia | 3 | 127 | Fixed | 0.041 (0.017–0.095) | −6.889 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.081 (0.026–0.223) | − 4.029 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Neck pain | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.081 (0.026–0.223) | −4.029 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Back pain | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Chest pain | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | − 3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||||||||||

| Rash | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.370 (0.286–0.462) | −2.741 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Rash maculo-papular | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.182 (0.121–0.266) | −6.046 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Skin exfoliation | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.035 (0.013–0.090) | − 6.501 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Dry skin | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.070 (0.036–0.135) | −7.033 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Infections and infestations | ||||||||||||

| Sepsis | 2 | 37 | Random | 0.139 (0.017–0.607) | −1.584 | 0.113 | ||||||

| Pneumonia | 2 | 53 | Fixed | 0.116 (0.053–0.236) | −4.663 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Pneumonitis | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.021 (0.005–0.082) | −5.334 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.056 (0.014–0.200) | −3.863 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Nervous system and psychiatric disorders | ||||||||||||

| Dysgeusia | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.044 (0.018–0.101) | −6.738 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Headache | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.142 (0.060–0.300) | −3.712 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Insomnia | 2 | 37 | Fixed | 0.110 (0.042–0.260) | −3.930 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Malaise | 2 | 114 | Fixed | 0.048 (0.020–0.110) | −6.509 | 0.000 | ||||||

Overall efficacy analysis

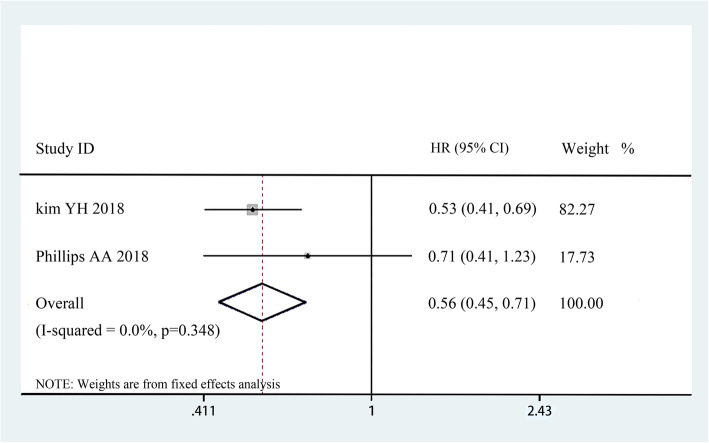

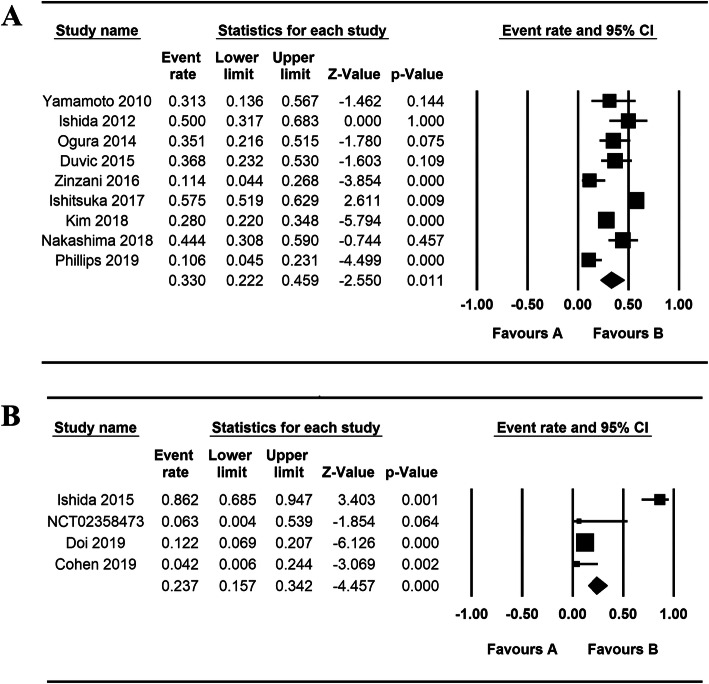

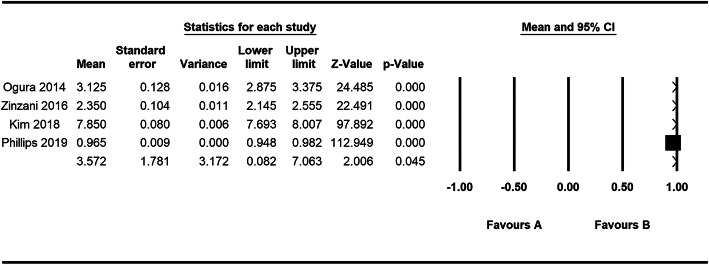

The pooled ORR rate, mean OS and mean PFS were used to measure the efficacy of mogamulizumab in treating cancers. For monotherapy, nine trials [14–17, 19–23] were included in the ORR analysis, and 4 articles [17, 20, 21, 23] were incorporated in the mean PFS analysis. According to our analysis, the pooled ORR rate was 0.430 (95% CI: 0.393–0.469) (Fig. 2A). The median PFS varied from 0.93 to 7.7 months and the pooled mean PFS was 1.060 months (95% CI: 1.043–1.077 Z = 125.452, p = 0.000) (Fig. 3). Besides, we performed further analyses to evaluate the efficacy between mogamulizumab and other chemotherapeutics. In controlled trials, the HRs for PFS in 2 control trials was 0.53 and 0.71 with a total HR of 0.56 (95% CI: 0.45–0.71, I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.348) (Fig. 4), indicating a longer PFS in mogamulizumab group. For mogamulizumab in combination with other drugs, the pooled ORR rate was 0.203 (95% CI: 0.022–0.746) (Fig. 2B). Then we performed subgroup analyses to identify the pooled PFS and OS of patients with non-small cell lung cancer in combination therapies. The pooled PFS and OS were 2.435 months (95% CI: 1.752–3.119, Z = 6.982, p = 0.000) and 6.519 months (95% CI: 5.523–7.514, Z = 12.836, p = 0.000), respectively (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the ORR of the studies in monotherapy and multiple therapies. (A) monotherapy; (B) multiple therapies

Fig. 3.

Overall analysis of the PFS of the studies in monotherapy。

Fig. 4.

The HRs and 95% CI for PFS in control-arm trials

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of PFS and OS in non-small cell lung cancer patients with multiple therapies

| Study name | Year | Treatment | Cancer type | Media PFS (months) | Z-Value | P-Value | Media PFS (months) | Z-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02358473 | 2018 | mogamulizumab +docetaxel | NSCLC | 2.243 (95% CI:1.235–3.250) | 4.364 | 0.000 | 7.335 (95% CI:5.657–9.013) | 8.570 | 0.000 |

| Doi, T | 2019 | mogamulizumab +nivolumab | NSCLC | 2.600 (95% CI:1.669–3.531) | 5.473 | 0.000 | 6.075 (95% CI:4.838–7.312) | 9.629 | 0.000 |

| Overall | 2.435 (95% CI:1.752–3.119) | 6.982 | 0.000 | 6.519 (95% CI:5.523–7.514) | 12.836 | 0.000 |

Abbreviation: NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer

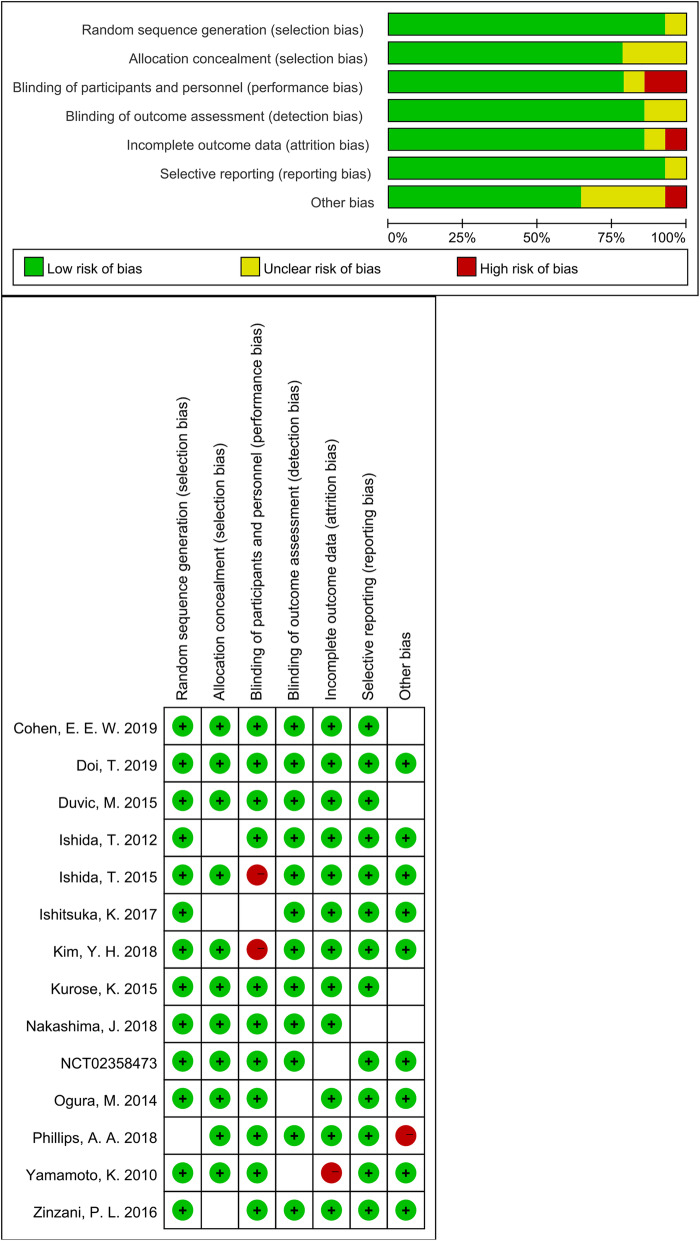

Assessment of study quality and publication bias

We used Review Manager 5.3 (Copenhagen, Sweden) to measure quality assessment of involved studies. Figure 5 indicated the risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary of all those eligible trials. Overall, the quality of the studies was satisfactory.

Fig. 5.

The risk of bias graph and the risk of bias summary

Discussion

Although various advanced or metastatic malignancies remain incurable, the application of mogamulizumab does benefit the patients. In this meta-analysis, we selected 14 prospective trials with 1290 patients and systematically assess the safety and efficacy of mogamulizumab. The integrated results of the data analysis confirm the role of mogamulizumab in various cancers. This is the first time to evaluated the safety and efficacy of mogamulizumab independently and systematically. This meta-analysis reveals that mogamulizumab is a novel therapy in treating various cancers, offering powerful evidence for clinical decision.

With regard to the safety, we analyzed the AEs of patients administered mogamulizumab by intravenous infusion. According to our analysis, the most common all-grade AEs in low, medium and high doses were lymphopenia, and event rates of lymphopenia were all higher than 70%. Besides, lymphopenia was also the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs which happened in nearly half of the participants. For combination therapies, neutropenia was the most common AEs which happened in more than 80% patients while lymphopenia was the most common grade ≥ 3 AEs which happened in nearly half of the participants. Most of the AEs associated with mogamulizumab were mild and reversible. The observed lymphopenia in all doses and all mogamulizumab-related therapies was considered the pharmacologic effect of mogamulizumab. Though transient, infusion reaction was the most common nonhematologic AEs. The mogamulizumab, having a defucosylated Fc region, has increased binding affinity to the Fcγ receptor on effector cells such as NK cells which can enhance ADCC. By strongly activating NK cells, mogamulizumab can induce NK cells to release cytokines and related cytotoxic molecules which might be the mechanism of infusion reaction [15, 28, 29]. Mogamulizumab can reduce the level of CCR4-positive malignant T cells locally and systematically, and can also eliminate CCR4-positive Tregs leading to Tregs depletion, which contributes to the enhancement of antitumor effects and the immunotherapeutic effect of activating the host immune response [18, 30]. However, mogamulizumab induced Tregs depletion can cause alteration of the immune balance, which may unleash various undesirable infections [22, 31]. Skin-related AEs were another frequent nonhematologic AEs because CCR4 can promote skin-specific homing of lymphocytes, while mogamulizumab was a monoclonal antibody directed against CCR4 [32, 33]. Mogamulizumab induced Tregs depletion may abrogate a peripheral checkpoint which is controlled by Tregs and induce the production of autoantibodies. These autoantibodies can combine with keratinocytes and melanocytes which play an essential role in the pathogenesis of skin-related AEs [34, 35]. In addition, some studies revealed the mogamulizumab treatment could provoke homeostatic CD8-positive T-cell proliferation predominantly of newly emerging clones, some of which may also play an important role in the pathogenesis of skin-related AEs [35–37]. For combination therapies, most of the AEs showed similar trends to those in monotherapy which was consist with previous studies. In combination therapy of mogamulizumab and nivolumab treating solid tumors, the profile of AEs was not substantially different from that seen in mogamulizumab or nivolumab monotherapy [25].

With regard to the efficacy, we analyzed the ORR, PFS, OS and HR for PFS of included trials. Approximately 43% of participants reached complete response or partial response in monotherapy. This is a particularly promising result since the response rate of patients with ATL, PTCL, CTCL ect, to conventional chemotherapy with a single agent is reportedly extremely low. The mogamulizumab is a humanized, IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody directed against CCR4 which can highly enhance antitumor effects by reducing the number of CCR4-positive leukemic cells and Tregs leading to Tregs depletion [38]. The mechanism of the decline of CCR4-positive leukemic cells is that mogamulizumab has increased binding affinity to the Fc receptor on effector cells such as NK cells which can enhance ADCC [29, 39]. The mechanism of Tregs depletion is that mogamulizumab prevents the binding of CCR4 and CCL22 so that the Tregs cannot be activated and recruited [38]. So the mechanism of antitumor activity is that the mogamulizumab can reduce the number of CCR4-positive leukemic cells, boost antitumor immunity by reducing CCR4-positive Tregs and influence tumor microenvironment to reduce tumor escape [40]. Patients administered mogamulizumab stabilized the disease more than 1 month and the overall patient survival time ranged from 4.9 months to 17.6 months which were longer than existing standard therapies. The analysis of HR for PFS in eligible trials also indicated that mogamulizumab can prolong the PFS of cancer patients compared to other chemotherapeutics. In the combination therapy of mogamulizumab and mLSG15 treating ATL, the pooled ORR was higher than that of mogamulizumab monotherapy, which was related to the different mechanism of antitumor effects. However, in combination therapy of mogamulizumab and nivolumab or utomilumab treating solid tumors, the pooled ORR was relatively low, which was related to the characteristics of the treated tumors. But mogamulizumab combined with nivolumab or utomilumab were more effective than nivolumab or utomilumab alone in treating solid tumors [24, 25, 41]. These results above demonstrated that mogamulizumab is a novel therapy in treating patients with cancers either as a single drug or in combination with other drugs.

However, there are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the data of this meta-analysis is limited and some included studies even miss partial data. More experiments with larger sample size and more comparisons with other drugs are required. Second, the deficiencies in the experimental design of the selective studies cannot be eliminated from our analysis. Third, some patients might receive different prior systemic chemotherapy regimens, which could affect the results of the present study. Besides, there are diversities in the study design of different experiments such as experiment duration. Finally, the cancer types are different, so the heterogeneity of the enrolled patients might have affected the results.

Conclusions

Based on the current evidence, this meta-analysis elucidates that mogamulizumab has clinically meaningful antitumor activity in patients with an acceptable toxicity profile which is a novel therapy in treating patients with cancers.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CCR4

CC chemokine receptor 4

- ATL

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

- PTCL

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

- CTCL

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- ORR

Objective responses rate

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- AEs

Adverse events

- CI

Confidence interval

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Authors’ contributions

TZ (Ting Zhang) and XLM conceived of the idea. TZ and JS designed the study, defined the search strategy and selection criteria, and were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. JY and YNZ performed the literature search and the analyses. TZ (Tao Zhang) and RNY performed the tables and diagrams. All the authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript, and ensured that this is the case.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available in this manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research is a pooled meta-analysis of published data and does not include any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Hence, the ethics approval and consent are not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ting Zhang and Jing Sun contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Yoshie O, Matsushima KJII. CCR4 and its ligands: from bench to bedside. Int immun. 2015;27(1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Wu XS, Lonsdorf AS, STJJoID H. Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: Roles for Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129(5):1115–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sokolowska-Wojdylo M, Wenzel J, Gaffal E, Lenz J, TTJBJo D. Circulating clonal CLA+ and CD4+ T cells in Sézary syndrome express the skin-homing chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR10 as well as the lymph node-homing chemokine receptor CCR7. Br J Dermatol 2005;152(2):258–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Susumu S, Takashi, Ishida, Kazuhiro, Yoshikawa, Ryuzo . Oncology UJJJoC: Current status of immunotherapy. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferenczi K, Fuhlbrigge RC, Pinkus J, Pinkus GS, Kupper TS. Increased CCR4 expression in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J invest Dermatol 2002;119(6):1405–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sugaya M, Morimura S, Suga H, Kawaguchi M, Miyagaki T, Ohmatsu H, et al. CCR4 is expressed on infiltrating cells in lesional skin of early mycosis fungoides and atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2015;42(6):613–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Duvic M. Choosing a systemic treatment for advanced stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015(1):529–544. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duvic M, Evans M, Wang C. Mogamulizumab for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: recent advances and clinical potential. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(3):171–174. doi: 10.1177/2040620716636541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishida. Research TJCC: CXC Chemokine Receptor 3 and CC Chemokine Receptor 4 Expression in T-Cell and NK-Cell Lymphomas with Special Reference to Clinicopathological Significance for Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma, Unspecified. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(16):5494–500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mukai M, Mould D, Maeda H, Narushima K, Greene D. Exposure-response analysis for Mogamulizumab in adults with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;60(1):50–57. doi: 10.1002/jcph.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekine M, Kubuki Y, Kameda T, Takeuchi M, Toyama T, Kawano N, Maeda K, Sato S, Ishizaki J, Kawano H, Kamiunten A, Akizuki K, Tahira Y, Shimoda H, Shide K, Hidaka T, Kitanaka A, Yamashita K, Matsuoka H, Shimoda K. Effects of mogamulizumab in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in clinical practice. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(5):501–507. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasamon YL, Chen H, de Claro RA, Nie L, Ye J, Blumenthal GM, Farrell AT, Pazdur R. FDA approval summary: Mogamulizumab-kpkc for mycosis Fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(24):7275–7280. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, TJBmrm T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Duvic M, Pinter-Brown LC, Foss FM, Sokol L, Jorgensen JL, Challagundla P, Dwyer KM, Zhang X, Kurman MR, Ballerini R, Liu L, Kim YH. Phase 1/2 study of mogamulizumab, a defucosylated anti-CCR4 antibody, in previously treated patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(12):1883–1889. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-600924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida T, Joh T, Uike N, Yamamoto K, Utsunomiya A, Yoshida S, Saburi Y, Miyamoto T, Takemoto S, Suzushima H, Tsukasaki K, Nosaka K, Fujiwara H, Ishitsuka K, Inagaki H, Ogura M, Akinaga S, Tomonaga M, Tobinai K, Ueda R. Defucosylated anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody (KW-0761) for relapsed adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):837–842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishitsuka K, Yurimoto S, Kawamura K, Tsuji Y, Iwabuchi M, Takahashi T, Tobinai K. Safety and efficacy of mogamulizumab in patients with adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma in Japan: interim results of postmarketing all-case surveillance. Int J Hematol. 2017;106(4):522–532. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YH, Bagot M, Pinter-Brown L, Rook AH, Porcu P, Horwitz SM, Whittaker S, Tokura Y, Vermeer M, Zinzani PL, Sokol L, Morris S, Kim EJ, Ortiz-Romero PL, Eradat H, Scarisbrick J, Tsianakas A, Elmets C, Dalle S, Fisher DC, Halwani A, Poligone B, Greer J, Fierro MT, Khot A, Moskowitz AJ, Musiek A, Shustov A, Pro B, Geskin LJ, Dwyer K, Moriya J, Leoni M, Humphrey JS, Hudgens S, Grebennik DO, Tobinai K, Duvic M, Abhyankar S, Akilov O, Alpdogan O, Beylot-Barry M, Boh E, Caballero D, Cowan R, Dreno B, Dummer R, Fenske T, Foss F, Fukuhara N, Giri P, Habe K, Hamada T, Hatake K, Iida S, Ishikawa O, Iversen L, Kiyohara E, Koga H, Korman N, Kuss BJ, Lamar Z, Lansigan F, Lechowicz MJ, Lerner A, Magnolo N, Mark L, Miyagaki T, Munoz J, Nicolay JP, Nishiwaki K, Okamoto H, Ohtsuka M, Pacheco T, Querfeld C, Rapini RP, Sano S, Tanaka M, Tharp MD, Uehara J, Wada H, Wells J, Wilcox RA, William B, Yonekura K. Mogamulizumab versus vorinostat in previously treated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (MAVORIC): an international, open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(9):1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30379-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurose K, Ohue Y, Wada H, Iida S, Ishida T, Kojima T, Doi T, Suzuki S, Isobe M, Funakoshi T, Kakimi K, Nishikawa H, Udono H, Oka M, Ueda R, Nakayama E. Phase Ia study of FoxP3+ CD4 Treg depletion by infusion of a humanized anti-CCR4 antibody, KW-0761, in Cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4327–4336. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakashima J, Imaizumi Y, Taniguchi H, Ando K, Iwanaga M, Itonaga H, Sato S, Sawayama Y, Hata T, Yoshida S, Moriuchi Y, Miyazaki Y. Clinical factors to predict outcome following mogamulizumab in adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2018;108(5):516–523. doi: 10.1007/s12185-018-2509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogura M, Ishida T, Hatake K, Taniwaki M, Ando K, Tobinai K, Fujimoto K, Yamamoto K, Miyamoto T, Uike N, Tanimoto M, Tsukasaki K, Ishizawa K, Suzumiya J, Inagaki H, Tamura K, Akinaga S, Tomonaga M, Ueda R. Multicenter phase II study of mogamulizumab (KW-0761), a defucosylated anti-cc chemokine receptor 4 antibody, in patients with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1157–1163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips AA, Fields PA, Hermine O, Ramos JC, Beltran BE, Pereira J, Wandroo F, Feldman T, Taylor GP, Sawas A, Humphrey J, Kurman M, Moriya J, Dwyer K, Leoni M, Conlon K, Cook L, Gonsky J, Horwitz SM, 0761-009 Study Group Mogamulizumab versus investigator's choice of chemotherapy regimen in relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Haematologica. 2019;104(5):993–1003. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.205096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto K, Utsunomiya A, Tobinai K, Tsukasaki K, Uike N, Uozumi K, Yamaguchi K, Yamada Y, Hanada S, Tamura K, Nakamura S, Inagaki H, Ohshima K, Kiyoi H, Ishida T, Matsushima K, Akinaga S, Ogura M, Tomonaga M, Ueda R. Phase I study of KW-0761, a defucosylated humanized anti-CCR4 antibody, in relapsed patients with adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(9):1591–1598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zinzani PL, Karlin L, Radford J, Caballero D, Fields P, Chamuleau MED, d'Amore F, Haioun C, Thieblemont C, González-Barca E, et al. European phase II study of mogamulizumab, an anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody, in relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2016;101(10):e407–e410. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.146977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen EEW, Pishvaian MJ, Shepard DR, Wang D, Weiss J, Johnson ML, Chung CH, Chen Y, Huang B, Davis CB, Toffalorio F, Thall A, Powell SF. A phase Ib study of utomilumab (PF-05082566) in combination with mogamulizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0815-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doi T, Muro K, Ishii H, Kato T, Tsushima T, Takenoyama M, Oizumi S, Gemmoto K, Suna H, Enokitani K, Kawakami T, Nishikawa H, Yamamoto N. A phase I study of the anti-CC chemokine receptor 4 antibody, Mogamulizumab, in combination with Nivolumab in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(22):6614–6622. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishida T, Jo T, Takemoto S, Suzushima H, Uozumi K, Yamamoto K, Uike N, Saburi Y, Nosaka K, Utsunomiya A, Tobinai K, Fujiwara H, Ishitsuka K, Yoshida S, Taira N, Moriuchi Y, Imada K, Miyamoto T, Akinaga S, Tomonaga M, Ueda R. Dose-intensified chemotherapy alone or in combination with mogamulizumab in newly diagnosed aggressive adult T-cell leukaemia-lymphoma: a randomized phase II study. Br J Haematol. 2015;169(5):672–682. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Study of mogamulizumab + docetaxel in subjects with non-small cell lung cancer. Available from: http:// clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT02358473.

- 28.Niwa R, Sakurada M, Kobayashi Y, Uehara A, Matsushima K, Ueda R, et al. Enhanced natural killer cell binding and activation by low-fucose IgG1 antibody results in potent antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity induction at lower antigen density. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11(6):2327. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Ishii T, Ishida T, Utsunomiya A, Inagaki A, Yano H, Komatsu H, Iida S, Imada K, Uchiyama T, Akinaga S, Shitara K, Ueda R. Defucosylated humanized anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody KW-0761 as a novel immunotherapeutic agent for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(5):1520–1531. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni X, Langridge T, Duvic MJO. Depletion of regulatory T cells by targeting CC chemokine receptor type 4 with mogamulizumab. Oncoimmunology 2015;4(7):e1011524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Remer M, Al-Shamkhani A, Glennie M, Johnson PJI. Mogamulizumab and the treatment of CCR4-positive T-cell lymphomas. Immuno 2014;6(11):1187–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Campbell JJ. The chemokine receptor CCR4 in vascular recognition by cutaneous but not intestinal memory T cells. Nature. 1999;400(6746):776–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Girardi M, Heald PW, LDJNEJoM W. The Pathogenesis of Mycosis Fungoides. New Eng J Med. 2004;350(19):1978–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Kinnunen T, Chamberlain N, Morbach H, Choi J, Kim S, Craft J, et al. Accumulation of peripheral autoreactive B cells in the absence of functional human regulatory T cells. Blood; 2013;121(9):1595–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Suzuki Y, Saito M, Ishii T, Urakawa I, Matsumoto A, Masaki A, et al. Mogamulizumab Treatment Elicits Autoantibodies Attacking the Skin in Patients with Adult T-Cell Leukemia-Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25(14):4388–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Saito M, Ishii T, Urakawa I, Matsumoto A, Ishida TJBA. Robust CD8+ T-cell proliferation and diversification after mogamulizumab in patients with adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma. Blood adv; 2020;4(10):2180–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Ishida T, Ito A, Sato F, Kusumoto S, Iida S, Inagaki H, et al. Ueda RJCe: Stevens–Johnson Syndrome associated with mogamulizumab treatment of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Sci; 2013;104(5):647–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Gobert M, Treilleux I, Bendriss-Vermare N, Bachelot T, Goddard-Leon S, Arfi V, et al. Regulatory T Cells Recruited through CCL22/CCR4 Are Selectively Activated in Lymphoid Infiltrates Surrounding Primary Breast Tumors and Lead to an Adverse Clinical Outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2000–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, Shoji-Hosaka E, Kanda Y, Sakurada M, et al. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 2003;278(5):3466–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Ishida T. Science RUJC: CCR4 as a novel molecular target for immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Sci 2006;97(11):1139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Segal NH, He AR, Doi T, Levy R, Bhatia S, Pishvaian MJ, et al. Huang BJCCR: Phase I Study of Single-Agent Utomilumab (PF-05082566), a 4-1BB/CD137 Agonist, in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;1078–0432:CCR-1017-1922. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in this manuscript.