Significance

Active torque generation in the actin cytoskeleton has been implicated in driving left–right symmetry breaking of developing embryos, but which molecules generate the active torque and how active torque generation is organized subcellularly remain unclear. This study shows that cortical Formin, recruited to cortical regions where RhoA signaling is active, promotes active torque generation in the actomyosin layer. We find that active torque tends to locally rotate the cortex in a clockwise fashion, which drives the emergence of chiral counterrotating flows with consistent handedness and facilitates left–right symmetry breaking of C. elegans embryos.

Keywords: left–right asymmetry, Formin, RhoA signaling, C. elegans

Abstract

Proper left–right symmetry breaking is essential for animal development, and in many cases, this process is actomyosin-dependent. In Caenorhabditis elegans embryos active torque generation in the actomyosin layer promotes left–right symmetry breaking by driving chiral counterrotating cortical flows. While both Formins and Myosins have been implicated in left–right symmetry breaking and both can rotate actin filaments in vitro, it remains unclear whether active torques in the actomyosin cortex are generated by Formins, Myosins, or both. We combined the strength of C. elegans genetics with quantitative imaging and thin film, chiral active fluid theory to show that, while Non-Muscle Myosin II activity drives cortical actomyosin flows, it is permissive for chiral counterrotation and dispensable for chiral symmetry breaking of cortical flows. Instead, we find that CYK-1/Formin activation in RhoA foci is instructive for chiral counterrotation and promotes in-plane, active torque generation in the actomyosin cortex. Notably, we observe that artificially generated large active RhoA patches undergo rotations with consistent handedness in a CYK-1/Formin–dependent manner. Altogether, we conclude that CYK-1/Formin–dependent active torque generation facilitates chiral symmetry breaking of actomyosin flows and drives organismal left–right symmetry breaking in the nematode worm.

The emergence of left–right asymmetry is essential for normal animal development and, in the majority of animal species, one type of handedness is dominant (1). The actin cytoskeleton plays an instrumental role in establishing the left–right asymmetric body plan of invertebrates like fruit flies (2–6), nematodes (7–11), and pond snails (12–15). Moreover, an increasing number of studies showed that vertebrate left–right patterning also depends on a functional actomyosin cytoskeleton (13, 16–22). Actomyosin-dependent chiral behavior has even been reported in isolated cells (23–28) and such cell-intrinsic chirality has been shown to promote left–right asymmetric morphogenesis of tissues (29, 30), organs (21, 31), and entire embryonic body plans (12, 13, 32, 33). Active force generation in the actin cytoskeleton is responsible for shaping cells and tissues during embryo morphogenesis. Torques are rotational forces with a given handedness and it has been proposed that in plane, active torque generation in the actin cytoskeleton drives chiral morphogenesis (7, 8, 34, 35).

What could be the molecular origin of these active torques? The actomyosin cytoskeleton consists of actin filaments, actin-binding proteins, and Myosin motors. Actin filaments are polar polymers with a right-handed helical pitch and are therefore chiral themselves (36, 37). Due to the right-handed pitch of filamentous actin, Myosin motors can rotate actin filaments along their long axis while pulling on them (33, 38–42). Similarly, when physically constrained, members of the Formin family rotate actin filaments along their long axis while elongating them (43). In both cases the handedness of this rotation is determined by the helical nature of the actin polymer. From this it follows that both Formins and Myosins are a potential source of molecular torque generation that could drive cellular and organismal chirality. Indeed, chiral processes across different length scales, and across species, are dependent on Myosins (19), Formins (13–15, 26), or both (7, 8, 21, 44). It is, however, unclear how Formins and Myosins contribute to active torque generation and the emergence chiral processes in developing embryos.

In our previous work we showed that the actomyosin cortex of some Caenorhabditis elegans embryonic blastomeres undergoes chiral counterrotations with consistent handedness (7, 35). These chiral actomyosin flows can be recapitulated using active chiral fluid theory that describes the actomyosin layer as a thin-film, active gel that generates active torques (7, 45, 46). Chiral counterrotating cortical flows reorient the cell division axis, which is essential for normal left–right symmetry breaking (7, 47). Moreover, cortical counterrotations with the same handedness have been observed in Xenopus one-cell embryos (32), suggesting that chiral counterrotations are conserved among distant species. Chiral counterrotating actomyosin flow in C. elegans blastomeres is driven by RhoA signaling and is dependent on Non-Muscle Myosin II motor proteins (7). Moreover, the Formin CYK-1 has been implicated in actomyosin flow chirality during early polarization of the zygote as well as during the first cytokinesis (48, 49). Despite having identified a role for Myosins and Formins, the underlying mechanism by which active torques are generated remains elusive.

Here we show that the Diaphanous-like Formin, CYK-1/Formin, is a critical determinant for the emergence of actomyosin flow chirality, while Non-Muscle Myosin II (NMY-2) plays a permissive role. Our results show that cortical CYK-1/Formin is recruited by active RhoA signaling foci and promotes active torque generation, which in turn tends to locally rotate the actomyosin cortex clockwise. In the highly connected actomyosin meshwork, a gradient of these active torques drives the emergence of chiral counterrotating cortical flows with uniform handedness, which is essential for proper left–right symmetry breaking. Together, these results provide mechanistic insight into how Formin-dependent torque generation drives cellular and organismal left–right symmetry breaking.

Results

CYK-1/Formin Is a Critical Determinant of Actomyosin Flow Chirality.

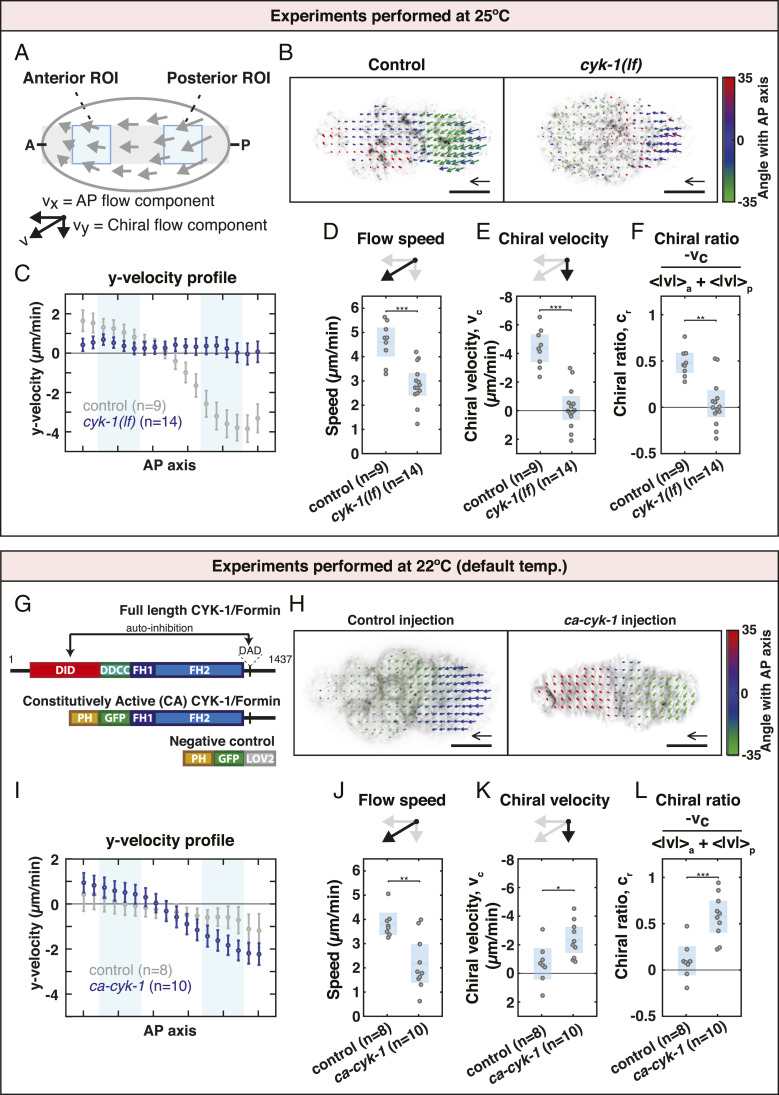

Because members of the Formin family have been implicated in chiral processes in multiple developmental contexts (13–15, 21, 44, 48, 49), we first asked whether the chiral counterrotating actomyosin flows observed during anteroposterior polarization of the C. elegans zygote are dependent on CYK-1/Formin (50). To perturb CYK-1/Formin protein function we made use of a temperature-sensitive cyk-1/Formin mutant which yields nonfunctional CYK-1/Formin protein at the restrictive temperature (25 °C) (51). Polarizing actomyosin flows were recorded at 25 °C in controls and cyk-1/Formin mutants by imaging the cortical surface of one-cell embryos producing endogenously tagged Non-Muscle Myosin II (NMY-2::GFP) (52). Subsequently, flows were quantified using particle image velocimetry (PIV) and averaged over space and time. Although cortical flow in control embryos is mainly directed along the anteroposterior (AP) axis, we find that the anterior and posterior cortical halves counterrotate relative to each other (Movie S1 and Fig. 1 A–C). Notably, the handedness of the counterrotation is consistent among embryos (Fig. 1 A–C) and these findings are in line with earlier results (7).

Fig. 1.

CYK-1/Formin is a determinant of actomyosin flow chirality. (A) Schematic of a C. elegans zygote during anteroposterior polarization. Gray: region used to obtain the flow velocity profiles. Blue areas: regions of interest used to calculate the mean flow speed, chiral velocity, and chiral ratio. (B) Time-averaged flow field overlaid on an image of cortical NMY-2::GFP of a control and a cyk-1(lf) mutant embryo. Velocity vectors are color coded for their angle with the anteroposterior axis. (Scale bar, 10 m.) Velocity scale arrow, 20 m/min. (C) Mean y velocity in 18 bins along the anteroposterior axis averaged over embryos for control (gray) and for cyk-1(lf) (blue). Light blue areas: bins 3 to 6 and 13 to 16 corresponding to the anterior and posterior regions of interest, respectively. Error bars, SEM. (D) Mean speed per embryo defined as , where and are the spatial averages in the anterior and posterior regions of interest, respectively. (E) Mean chiral velocity, , per embryo defined as , where and are the spatially averaged y velocities in the anterior and posterior regions of interest, respectively. (F) Mean chiral ratio per embryo, defined as . (G) Domain overview of CYK-1/Formin (top) and the constructs generated in this study (middle and bottom). DID, Dia Inhibitory Domain; DD, Dimerization Domain; CC, Coiled Coil; FH, Formin Homology; DAD, Diaphanous Autoregulatory Domain; PH, Pleckstrin Homology; LOV2, Light-Oxygen-Voltage 2 domain. (H) Time-averaged flow field overlaid on an image of cortical Lifeact-mKate2 derived from control (ph-gfp-lov2) injection and ca-cyk-1/Formin injection. (I) Mean y-velocity profile in embryos derived from control injection (gray) and from ca-cyk-1/Formin injection (blue). (J–L) Mean flow speed (J), chiral velocity (K), and chiral ratio (L) in embryos derived from control injection and from ca-cyk-1/Formin injection. Blue in D–F and J–L depicts the mean over embryos with 95 confidence interval. Significance testing: *P 0.05; **P 0.01; ***P 0.001 (Wilcoxon rank sum test). n indicates the number of embryos.

To quantify chiral counterrotation of the flow we decomposed velocity vectors into a component along the AP axis (x velocity, ) and a chiral component perpendicular to the AP axis (y velocity, ) (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, we computed the chiral velocity, , by subtracting the averaged in the anterior from the averaged in the posterior () (7). Nonperturbed control embryos display a of −4.36 1.00 m/min (mean 95 CI throughout this article) (Fig. 1E). Note that this differs from the chiral velocity previously reported (−2.9 0.3 m/min in ref. 7). However, we have here measured the chiral velocity at 25 °C (in contrast to the temperature of 22 to 23 °C used in ref. 7) and in a different genetic background and note that both temperature and the genetic background can affect chiral velocity (SI Appendix, SI Notes and Fig. S2). We next quantified the cortical flows in cyk-1/Formin mutants at 25 °C and found a of −0.20 0.82 m/min, indicating that the chiral counterrotation was lost entirely (Movie S2 and Fig. 1 B, C, and E). Note that the average flow speed (Fig. 1D), x velocity (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B), and flow coherence (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C) were significantly reduced in cyk-1/Formin mutants, suggesting that, in addition to flow chirality, CYK-1/Formin affects multiple aspects of flow dynamics. To exclude that the reduced chiral velocity is simply due to a reduction in overall flow speed, we normalized the chiral velocity by the flow speed and define a chiral ratio, , according to , where and are the mean flow speed in the anterior and the posterior, respectively. While unperturbed control embryos display a chiral ratio of 0.48 0.11 (Fig. 1F), the chiral ratio in cyk-1/Formin mutants is 0.04 0.14 (Fig. 1F), indicating that CYK-1/Formin is indeed required to promote actomyosin flow chirality.

We next asked whether CYK-1/Formin activity is sufficient to promote chiral counterrotating flows in C. elegans zygotes. To this end, we sought to experimentally increase CYK-1/Formin activity. Like other Diaphanous-like formins, CYK-1/Formin contains an N-terminal regulatory domain that is required for autoinhibition and deletion of this domain in other Formins results in constitutively active protein (53–56). Therefore, we generated a truncated CYK-1/Formin construct (residues 700 to 1,437) and replaced the N terminus with a fluorescent membrane localization domain (PH-GFP) (Fig. 1G). We refer to this construct as Constitutively Active CYK-1/Formin (CA-CYK-1/Formin).

We expressed ca-cyk-1/Formin transiently (Materials and Methods) in the adult gonad of worms carrying a lifeact::mKate2 transgene that are otherwise wild type. This allowed us to obtain zygotes with variable levels of CA-CYK-1/Formin. Introducing high levels of CA-CYK-1/Formin in embryos expressing Lifeact-mKate2 (a marker for F-actin) revealed numerous cortical anomalies. Often cortical actomyosin flow direction changed repeatedly and this was accompanied by repeated reorientations of local actin filament alignment (Movie S4 and SI Appendix, SI Notes). Such defects were never observed in embryos derived from negative control injections (ph-gfp-lov2; Movie S3). Moreover, expression of CA-CYK-1/Formin resulted in an increase in the cortex-to-cytoplasm ratio of Lifeact-mKate2, consistent with an elevated cortical abundance of F-actin (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and G–I). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that the CA-CYK-1/Formin construct is indeed constitutively active.

We next sought to determine whether introducing CA-CYK-1/Formin affects actomyosin flow chirality. Because high levels of CA-CYK-1/Formin strongly perturb cortex physiology (Movie S4), we analyzed embryos producing low levels of CA-CYK-1/Formin (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E). Low levels of CA-CYK-1/Formin resulted in a significant increase in both the chiral counterrotation of the flow and the chiral ratio (Movie S5; Fig. 1 H, I, K, and L; and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 E and F), indicating that CA-CYK-1/Formin activity is sufficient to promote chiral counterrotating flows. We note that the mean cortical flow speed and the anteroposterior component of the flow () were substantially reduced when compared to control injections (Movies S3 and S5; Fig. 1J; and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 J and K), indicating that constitutive CYK-1/Formin activity has additional effects on cortex dynamics. We also note that the chiral velocity and chiral ratio in negative control embryos (ph-gfp-lov2) are reduced when compared to the control embryos imaged at 25 °C (Fig. 1 B–F). This is consistent with both temperature and genetic background impacting on actomyosin flow chirality (SI Appendix, SI Notes and Fig. S2). Together, given that the chiral ratio is increased upon introduction of CA-CYK-1/Formin, these results lend credence to the statement that CYK-1/Formin affects the strength of chiral counterrotation. We conclude that CYK-1/Formin is a critical determinant for actomyosin flow chirality.

CYK-1/Formin Promotes Torque Generation in the Actomyosin Layer.

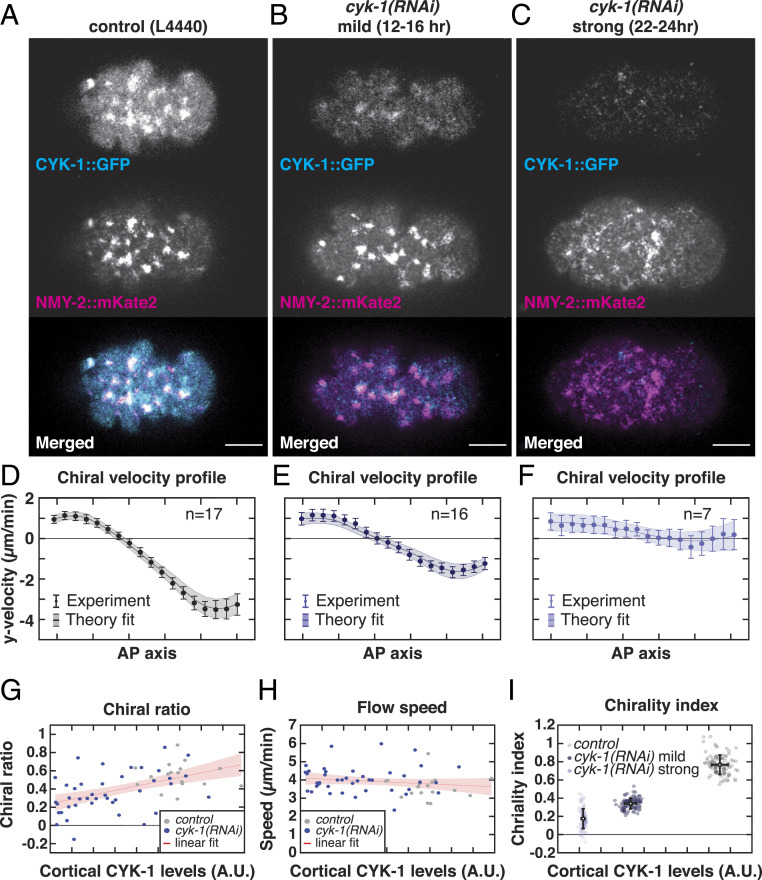

Given that CYK-1/Formin determines actomyosin flow chirality, we hypothesized that CYK-1/Formin itself could generate active torques. Alternatively, given that strong loss or gain of CYK-1/Formin function results in a reduction of cortical flow speed (Fig. 1 D and J), CYK-1/Formin could play an indirect, permissive role in the emergence of chiral cortical flows, by generating the cortical F-actin needed to support active forces and torques. To discriminate between these two possibilities, we next performed weak perturbation cyk-1(RNAi) experiments, in which we vary the depletion strength by varying the RNAi feeding time (ranging from 6 to 24 h). Subsequently, we quantified the cortical flow dynamics upon mild deviations from wild-type CYK-1/Formin levels, equivalent to determining the linear response to a small perturbation. These cyk-1(RNAi) treatments were performed on embryos producing endogenously tagged NMY-2::mKate2 to measure cortical flows and CYK-1/Formin::GFP to measure cortical levels of CYK-1/Formin (Fig. 2 A–C). We hypothesized that if CYK-1/Formin affects flow chirality indirectly by modulating cortex structure, both flow speed and flow chirality will decrease with decreasing cortical CYK-1/Formin levels. Alternatively, if CYK-1/Formin generates active torques itself, flow chirality, but not flow speed, will decrease with decreasing cortical CYK-1/Formin levels. Consistent with the latter hypothesis, we found that both the chiral counterrotation velocity, (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D), and the chiral ratio of the flow (Fig. 2G) correlated with cortical CYK-1/Formin levels (Spearman’s = −0.44, P 0.0007 and = 0.54, P 0.00002, respectively), while we found no significant correlation between CYK-1/Formin levels and cortical flow speed (Spearman’s = −0.23, P = 0.08) (Fig. 2H). We note that even a strong cyk-1(RNAi) perturbation did not affect the mean flow speed, as did the cyk-1/Formin loss-of-function mutation described above. This apparent discrepancy is likely to be explained by residual CYK-1/Formin levels remaining, even upon strong cyk-1(RNAi) treatment. Together, our results show that, at physiological levels, CYK-1/Formin modulates flow chirality but not flow speed. These findings are consistent with a direct role for CYK-1/Formin in promoting active torque generation in the cortex.

Fig. 2.

CYK-1/Formin promotes torque generation in the actomyosin cortex. (A–C) Representative micrographs of cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP and NMY-2::mKate2 in (A) control (L4440), (B) mild cyk-1(RNAi) (12 to 16 h), and (C) strong cyk-1(RNAi) (22 to 24 h) during polarizing flows. (Scale bar, 10 m.) (D–F) Mean y-velocity profile in 18 bins along the anteroposterior axis. Conditions are as in A–C. Circles with error bars are the experimentally measured y velocities averaged over embryos, with SEM. Solid line shows the mean y velocities derived from fitting the hydrodynamic model to 100 bootstrap samples with replacement. Shaded region: standard deviation of the mean, derived from bootstrapping. n indicates the number of embryos. (G and H) Chiral ratio (G) and speed (H) of the cortical flow plotted over the measured cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP fluorescence in control (L4440, gray) and upon increasing strength of cyk-1(RNAi) (blue). Data points represent individual embryos (control, n = 17; cyk-1(RNAi), n = 41). Red line with shaded region shows a linear fit with 95 confidence bounds. Chiral ratio, but not flow speed, correlates with cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP (Spearman’s = 0.54, P 0.00002). (I) Chirality index plotted over the measured cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP fluorescence in control (L4440, gray), mild cyk-1(RNAi) (12 to 16 h, dark blue), and strong cyk-1(RNAi) (22 to 24 h, light blue). Chirality index was obtained by fitting the hydrodynamic model to the mean of individual bootstrap samples with replacement. Simultaneously, in each bootstrap sample the mean cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP fluorescence was calculated. Gray and blue data points represent individual bootstrap samples. Black points with error bars display the mean over all bootstrap samples with standard deviation.

To determine whether CYK-1/Formin indeed promotes active torque generation, we next applied active chiral fluid theory (45, 46). This coarse-grained theoretical description is built on the principle that the cortex tends to locally contract in response to active tension and tends to locally rotate clockwise (when viewed from the outside) in response to active torque generation. An anteroposterior gradient of active tension drives flows along the AP axis, while an anteroposterior gradient of active torques drives chiral counterrotation of the flow. By fitting the experimentally measured flow profiles to the active chiral fluid model, the amount of active tension and active torque generation can be obtained. From this, a dimensionless measure for actomyosin flow chirality can be computed by taking the ratio of active torque density to active tension, denoted as the chirality index (7). Note that, although both the chirality index, and the chiral ratio, (introduced above) are measures for the relative strength of chirality, the chirality index is derived from fitting the theoretical model while the chiral ratio is measured directly from the obtained flow velocity profile. Fitting the theoretical model to the flow velocity profiles of control, mild, and strong cyk-1(RNAi) yielded a good agreement between model and experiment (Fig. 2 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). Moreover, we found that the chirality index correlates with cortical CYK-1/Formin levels (Fig. 2I). These results further substantiate our conclusion that CYK-1/Formin determines cortical flow chirality by promoting active torque generation in the actomyosin layer.

CYK-1/Formin Is Required for Organismal Left–Right Symmetry Breaking.

Left–right symmetry breaking in C. elegans embryos occurs by a chiral skew of the ABa/ABp cell division axes in the four- to six-cell embryo (47) and chiral counterrotating actomyosin flows drive this event (7, 35). Therefore, we next asked whether this cell division skew is dependent on cyk-1/Formin. Given that cyk-1/Formin is required for normal cytokinesis, cyk-1/Formin temperature-sensitive mutants and controls were grown at permissive temperature (15 °C) until the four-cell stage and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (25 °C) prior to ABa/ABp cytokinesis. To quantify cell division skews, we imaged embryos expressing a tubulin marker (mCherry:Tubulin) and used the orientation of the mitotic spindle as a proxy for the cell division axis (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). Imaging the mitotic spindle during ABa/ABp cytokinesis revealed that the cell division skew in control embryos was 26.27 1.74° and 23.62 1.53° for ABa and ABp, respectively (Movie S6 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B, D, and E), which is consistent with previous reports (7, 35, 47, 57). This spindle skew was strongly reduced in cyk-1/Formin mutants (7.60 0.81° and 6.50 1.05° for ABa and ABp, respectively) (Movie S7 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C–E), demonstrating a role for cyk-1/Formin in left–right symmetry breaking. Given that chiral counterrotating flows drive the spindle skew of ABa and ABp (7, 35), and given that we show here that CYK-1/Formin determines actomyosin flow chirality, we conclude that CYK-1/Formin facilitates left–right symmetry breaking by controlling actomyosin flow chirality.

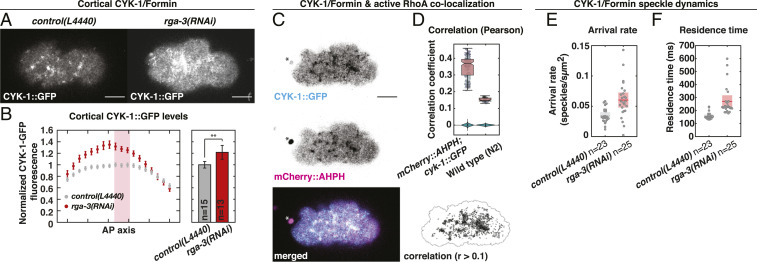

CYK-1/Formin Is a Target of RhoA Signaling.

In many different contexts Formins act directly downstream of the RhoA GTPase (58). Moreover, we showed previously that chiral actomyosin flows in the C. elegans embryo are controlled by RhoA signaling (7). Therefore, we next asked whether CYK-1/Formin is a RhoA target in the C. elegans zygote. Analysis of endogenously labeled CYK-1/Formin (CYK-1/Formin::GFP) revealed that CYK-1/Formin localizes in distinct cortical foci that are depleted from the posterior during the cortical flow phase. This sets up a gradient of CYK-1/Formin::GFP along the anteroposterior axis (Movie S8 and Fig. 3 A and B). The shape of this gradient, as well as the localization in foci, is similar to what was observed for other RhoA effectors (Movie S10 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D) (59–63). We next tested whether the CYK-1/Formin foci are indeed regions of high RhoA activity. Earlier studies have used the AH-PH domain of ANI-1 fused to GFP as a marker for RhoA activity (63). We generated an mCherry-tagged version of this probe and combined it with endogenously tagged CYK-1/Formin (CYK-1/Formin::GFP). Dual color imaging during polarizing flow revealed a significant colocalization (Pearson’s = 0.35), indicating that CYK-1/Formin::GFP indeed localizes to regions of active RhoA (Movie S12 and Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

CYK-1/Formin is a RhoA target during polarizing flows. (A) Representative micrographs of cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP in control (L4440, Left) and upon rga-3(RNAi) (Right). (B) Left, mean cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP fluorescence in 18 bins along the anteroposterior axis in control (L4440, gray) and upon rga-3(RNAi) (red). Fluorescence levels were normalized to the mean levels in bins 9 to 11 (red rectangle). Error bars, SEM. Right, mean cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP fluorescence measured in bins 9 to 11. Error bars, 95 confidence interval. Significance testing: **P 0.01 (Wilcoxon rank sum test). n indicates the number of embryos. (C) Cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP (Top), mCherry::ANI-1(AHPH) (Middle), and merged (Bottom). Asterisk marks the polar body. (Bottom Right) Regions of colocalization in black (Pearson’s correlation coefficient 0.1). Black line: masked region. (D) Pearson’s correlation coefficient computed in cyk-1::GFP; mCherry::ani-1(AHPH) (n = 13 embryos) and N2 wild type (n = 4 embryos) to control for correlation of autofluorescence. Data points represent individual frames (15 frames per embryo), and box plot is overlaid. As a negative control the correlation was computed after scrambling the pixels in one channel, 100 times independently. Violin plots display the distribution of these negative controls. (E and F) CYK-1/Formin::GFP speckle arrival rate (E) and residence time (F) in control (L4440; gray, n = 23 embryos) and upon rga-3(RNAi) (red, n = 25 embryos). Data points represent individual embryos. Boxes indicate mean with 95 confidence interval. (Scale bars, 10 m.)

If CYK-1/Formin is indeed a target of active RhoA, then cortical CYK-1/Formin levels will decrease with decreased RhoA signaling activity. To test this, we first reduced RhoA activity by RNAi of ect-2, which is the upstream activator of RhoA (64). ect-2(RNAi) resulted in a subtle reduction of cortical CYK-1/Formin::GFP levels and abolished its localization in cortical foci (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). In addition, increasing overall RhoA activity by RNAi of a negative regulator of RhoA signaling, rga-3 (64), led to a substantial increase of cortical CYK-1/Formin levels and cortex-to-cytoplasm ratio (Movie S9; Fig. 3 A and B; and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 E–G). Importantly, we observed a similar increase when analyzing cortical levels of NMY-2::GFP (Movie S11 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D), a well-known target of RhoA (64–66). Altogether, the results presented here are consistent with CYK-1/Formin being a target of RhoA.

RhoA GTPases recruit and activate Diaphanous-like Formins by binding to the N-terminal regulatory domain (54). Therefore, if RhoA recruits CYK-1/Formin directly, removal of the N-terminal regulatory domain will perturb its localization to active RhoA foci. To test this, we next performed dual color imaging of the active RhoA probe and CA-CYK-1/Formin, in which the N-terminal regulatory domain is replaced with a membrane localization domain (Pleckstrin Homology domain, PH). Although CA-CYK-1/Formin levels are close to the detection limit of our microscope setup, we found that it localizes in distinct cortical punctae that are not enriched in active RhoA foci (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These results suggest that 1) CA-CYK-1/Formin forms clusters in a RhoA-independent manner and 2) CA-CYK-1/Formin is not recruited to RhoA foci. These results are consistent with active RhoA recruiting endogenous CYK-1/Formin directly via the N-terminal regulatory domain.

We next asked how active RhoA controls CYK-1/Formin localization dynamics. To this end we performed speckle microscopy (67) of endogenously labeled CYK-1/Formin::GFP in control embryos and upon rga-3(RNAi) treatment during polarizing actomyosin flows (SI Appendix, SI Notes). To achieve sparse labeling of the fluorescent CYK-1/Formin::GFP pool we made use of the fact that the CYK-1/Formin::GFP signal photobleaches rapidly upon continuous imaging. After 50 s of imaging (1,000 frames) more than 98 of the mean fluorescent signal photobleached (Movie S13 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Due to strong photobleaching, the remaining fluorescent CYK-1/Formin::GFP appeared as sparsely localized, dynamic speckles in the cortical plane (Movie S14 and SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). This allowed us to detect newly arriving cortical CYK-1/Formin molecules from which we computed the cortical arrival rate and the residence time. We tracked a total of 55,612 CYK-1/Formin::GFP speckles in control (n = 23 embryos) and 89,080 in rga-3(RNAi) (n = 25 embryos) and found that rga-3(RNAi) increases both the arrival rate and the residence time (Fig. 3 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S7 D and E). Importantly, the measured residence times in control (159 11 ms) and rga-3(RNAi) (271 46 ms) are much lower than the half-life due to photobleaching (1,246 90 ms; SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), indicating that photobleaching results in only a mild underestimation of the residence time. Taken together, and consistent with a recent study (68), our results indicate that active RhoA increases cortical CYK-1/Formin levels by increasing the arrival rate and residence time of CYK-1/Formin.

RhoA Controls Actomyosin Flow Chirality via CYK-1/Formin Activation.

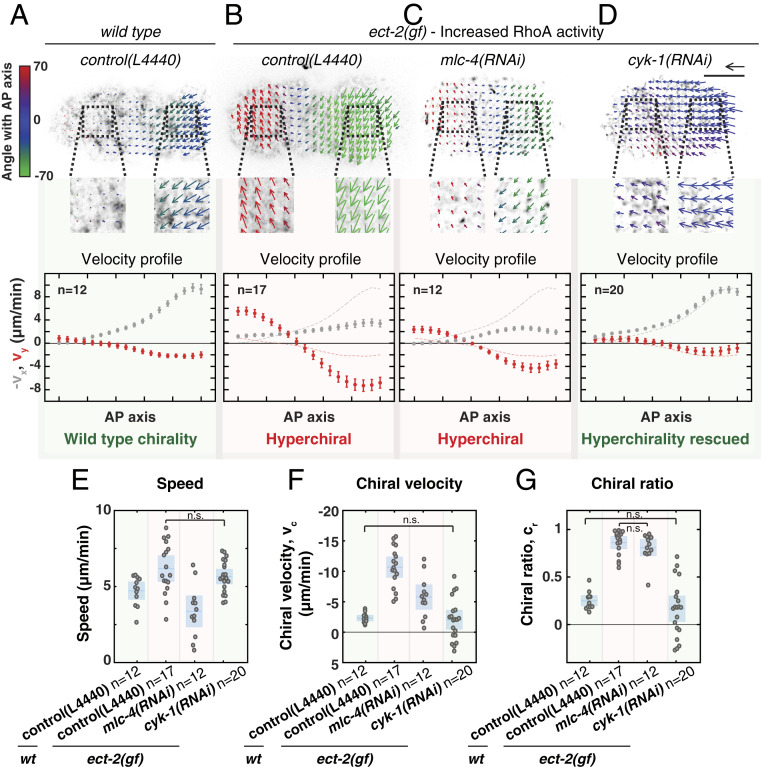

The results presented here show that CYK-1/Formin is a critical determinant of actomyosin flow chirality and that CYK-1/Formin is a RhoA target. In our earlier work we have demonstrated that chiral counterrotating flows are driven by RhoA signaling and are dependent on the RhoA target Non-Muscle Myosin II (NMY-2) (7). To further dissect the roles of NMY-2 and CYK-1/Formin in the emergence of chiral counterrotating flows, we asked which of these two RhoA targets is responsible for the hyperchirality phenotype associated with elevated RhoA activity. To experimentally increase RhoA signaling, we made use of a gain-of-function mutation in the upstream RhoA activator, ect-2 (69). While in wild-type embryos the anteroposterior component of the flow is dominant and chiral counterrotation is subtle, in ect-2 gain-of-function mutants we observed the opposite: The anteroposterior component of the flow is strongly reduced and the chiral counterrotation of the flow is dominant (Movies S15 and S16; Fig. 4 A, B, and F; and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). These findings are similar to those observed upon strong rga-3(RNAi) (Movie S11). Surprisingly, despite elevated RhoA signaling, the overall flow speed in ect-2(gf) mutants was only mildly increased (Fig. 4E). Hence, the increased RhoA activity in the ect-2(gf) mutant mainly acts to increase the chiral ratio (Fig. 4G), e.g., the fraction of the total flow speed accounted for by the chiral velocity.

Fig. 4.

RhoA promotes chiral counterrotating actomyosin flow via CYK-1/Formin activation. (A–D) (Top) Time-averaged flow fields overlaid on a still image of cortical NMY-2::GFP of (A) a wild-type embryo on RNAi control (L4440), (B) an ect-2(gf) mutant on RNAi control (L4440), (C) ect-2(gf); mlc-4(RNAi), and (D) ect-2(gf); cyk-1(RNAi). Mean velocity vectors are color coded for their angle with the anteroposterior axis. (Scale bar, 10 m.) Velocity scale arrow, 20 m/min. (Bottom) Mean x velocity (gray) and y velocity (red) in 18 bins along the anteroposterior axis. Dashed lines in the plots in B–D display the mean x- and y-velocity profiles in wild type. Error bars, SEM. n indicates the number of embryos. (E–G) Mean speed (E), chiral velocity (F), and chiral ratio (G) per embryo. Data points represent individual embryos. Blue stripe and area represent the mean with 95 confidence interval. Significance testing: Only conditions that are not significantly different are indicated in the diagrams (n.s., P 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test). The flow hyperchirality (red background in all panels) of ect-2(gf) is rescued in ect-2(gf); cyk-1(RNAi) (green background in all panels), but not in ect-2(gf); mlc-4(RNAi) (red background in all panels).

Next, we asked how the ect-2(gf)–induced hyperchirality depends on the RhoA effectors Non-Muscle Myosin II and CYK-1/Formin. We first reduced Non-Muscle Myosin II activity in the ect-2(gf) background by performing RNAi against the Myosin regulatory light chain, mlc-4. Importantly, as indicated by NMY-2::GFP fluorescence levels, cortical Non-Muscle Myosin II was reduced but not fully depleted (compare Movie S16 with Movie S17). mlc-4(RNAi) reduced both the flow speed and the chiral component of the flow (Movie S17 and Fig. 4 C, E, and F). Strikingly, the chiral ratio was indistinguishable from that observed in ect-2(gf) embryos, indicating that Non-Muscle Myosin II does not influence the relative strength of chiral counterrotation (Fig. 4G). In contrast, cyk-1(RNAi) in ect-2(gf) mutants completely rescued the ect-2(gf)–induced hyperchirality phenotype: The chiral velocity (), the anteroposterior velocity (), and the chiral ratio () were all restored to wild-type levels (Movie S18; Fig. 4 D, F, and G; and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A, E, and F), suggesting that RhoA acts through CYK-1/Formin. Finally, we tested whether ANI-1/Anillin, another RhoA target (60, 61, 63), is required for ect-2(gf)–induced hyperchirality. We found that ani-1(RNAi) in the ect-2(gf) background reduced both the flow speed and the chiral ratio (Movie S19 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B–D). ANI-1/Anillin is a passive actin cross-linker and therefore this result is consistent with ANI-1/Anillin playing a permissive role by controlling F-actin network integrity. Altogether, we conclude that Non-Muscle Myosin II and CYK-1/Formin play mechanistically distinct roles in the emergence of chiral flows: While myosin activity is required to drive cortical flows, CYK-1/Formin activity is required to break chiral symmetry and promote chiral counterrotatory flows with a consistent handedness.

To determine whether RhoA signaling determines actomyosin flow chirality via CYK-1/Formin activation, or whether active RhoA and CYK-1/Formin affect flow chirality in parallel, we next performed genetic epistasis analysis. If CYK-1/Formin and RhoA act in the same pathway, then full depletion of cyk-1/Formin in a RhoA hyperactive background is expected to phenocopy full depletion of cyk-1/Formin alone. Alternatively, if CYK-1/Formin and RhoA control actomyosin flow chirality in parallel, a full depletion of cyk-1/Formin in a RhoA hyperactive background will result in an intermediate flow chirality phenotype. To discriminate between these possibilities, we next analyzed cortical flows in cyk-1(lf) mutants, treated with rga-3(RNAi), at restrictive temperature (25 °C). Consistent with our previous reports, rga-3(RNAi) on control embryos strongly increases actomyosin flow chirality (Movie S20 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8E) (7, 35). Conversely, rga-3(RNAi) on cyk-1(lf) mutants did not affect actomyosin flow chirality and phenocopied cyk-1(lf) alone (Movies S21 and S22 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 E and F). These results demonstrate that cyk-1/Formin is epistatic to rga-3 and indicate that RhoA activity induces chiral symmetry breaking via CYK-1/Formin activation.

CYK-1/Formin Activation in Active RhoA Foci Promotes In-Plane Torque Generation.

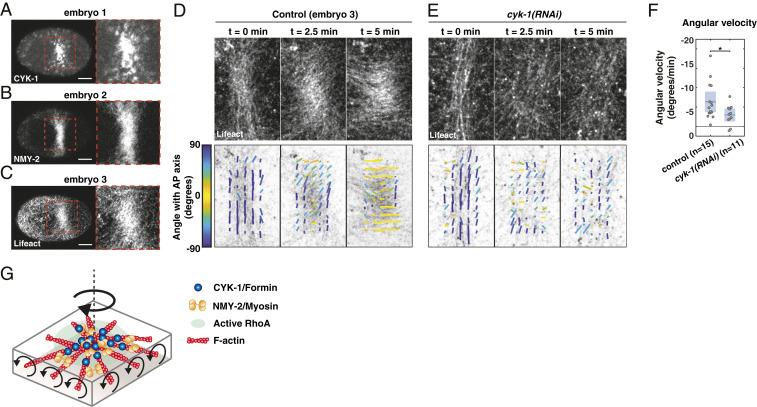

How are chiral counterrotating flows generated? The active chiral fluid description is built on the assumption that the cortex generates active in-plane torques that tend to rotate the cortex clockwise (viewed from the outside). Moreover, the cortex is organized into distinct foci that contain active RhoA and recruit CYK-1/Formin. Therefore, we hypothesize that 1) the functional units that generate in-plane torques are active RhoA foci and 2) Formin activation in these RhoA foci determines how strong the in-plane torque will be. Given that the actomyosin cortex is a highly connected meshwork, RhoA foci are interconnected and are unlikely to be free to rotate in response to active torques. Therefore, we sought to experimentally induce the formation of a single patch enriched in RhoA activity. In a recent study it was shown that strong compression of C. elegans zygotes during cytokinesis resulted in a collapse of the cytokinetic ring into a cortical patch containing high levels of the RhoA target NMY-2 (70). Because the cytokinetic ring forms in response to active RhoA, we hypothesized that these patches are regions of high RhoA activity. To test this, we repeated the embryo-compression experiments and found that, in addition to NMY-2, F-actin and CYK-1/Formin are also enriched in these compression-induced cortical patches (Movies S23–S25 and Fig. 5 A–C). We conclude that these patches are regions of high RhoA activity.

Fig. 5.

CYK-1/Formin activity in a compression-induced RhoA patch promotes clockwise reorientation of cortical F-actin. (A–C) Micrographs of compressed embryos in which the cytokinetic ring collapsed, resulting in a region enriched in (A) CYK-1/Formin, (B) NMY-2, and (C) F-actin. Note that the three images are derived from three different embryos. (Scale bars, 10 m.) (D and E) Fluorescent micrographs of cortical Lifeact-mKate2 (Top), overlaid with the local filament order in small templates (Bottom) of a (D) control and (E) cyk-1(RNAi) embryo, at the onset of patch formation (t = 0 min), during patch rotation (t = 2.5 min), and at the end of patch rotation (t = 5 min). Both examples shown in D and E display an embryo with strong clockwise reorientation, relative to the mean of the condition. Local directors are color coded for the angle with the anteroposterior axis. (F) Mean angular velocity in a time window of 5 min during reorientation of the patch in control and cyk-1(RNAi). Because the timing of rotation with respect to the onset of patch formation varied among embryos, the start of the 5-min time window was chosen such that the clockwise angular velocity was maximal (Materials and Methods). Mean with 95 confidence interval is indicated in blue. Significance testing: *P 0.05 (Wilcoxon rank sum test). n indicates the number of embryos. (G) Schematic of an active RhoA patch in which F-actin, NMY-2, and CYK-1/Formin are enriched. If Formins in the RhoA patch are constrained and elongate filaments in opposite directions, opposing filaments will counterrotate, which we hypothesize drives clockwise rotation of the patch as a whole.

If regions of high RhoA activity generate in-plane torques, we expect clockwise reorientations of the compression-induced active RhoA patch itself and the region surrounding it. Therefore, we next analyzed the orientation of actin filaments within and around the active RhoA patch. To quantify actin filament orientation we used a previously described method that subdivides the F-actin image into small templates, from which the mean filament orientation angle is extracted (71) (Fig. 5 D and E). At the onset of patch formation, actin filaments were mainly oriented perpendicular to the anteroposterior axis, resembling a normal cytokinetic ring (Movie S25 and Fig. 5D). Over time cortical flow was directed toward the active RhoA patch and CYK-1, NMY-2, and F-actin accumulated (Movies S23–S25). Strikingly, during growth of the patch, actin filaments slowly reoriented in a clockwise fashion with an average angular velocity of 6.34 2.62°/min (Movie S25 and Fig. 5 D and F). Although the extent and the speed of filament reorientation varied substantially among embryos (Movies S25–S27), counterclockwise rotations were never observed (Fig. 5F and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A, C, and D). Therefore, these results are consistent with the principle that active torques tend to rotate the actomyosin cortex in a clockwise fashion.

Finally, we asked whether the clockwise reorientations are CYK-1/Formin dependent. To test this we analyzed actin filament orientation upon cyk-1(RNAi) (Movies S28 and S29; Fig. 5E; and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Notably, rather than performing a strong depletion, we used conditions in which ring formation and cytokinesis still occurred in uncompressed conditions, indicative of a partial cyk-1/Formin knockdown. We found a subtle but significant reduction of actin filament reorientation upon cyk-1(RNAi) (2.95 1.69 °/min) (Fig. 5 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B–D), showing that cyk-1/Formin is required for in-plane rotation of the active RhoA patch. Altogether, our results indicate that regions of high RhoA activity generate active torque in a CYK-1/Formin–dependent manner, with consistent handedness.

Discussion

The work presented here shows that CYK-1/Formin, activated in cortical RhoA foci, promotes in-plane, active torque generation in the actomyosin layer and thereby facilitates left–right symmetry breaking of C. elegans embryos. Moreover, we find that CYK-1/Formin and Non-Muscle Myosin 2 (NMY-2) play mechanistically distinct roles: While NMY-2 is necessary to drive the emergence of cortical actomyosin flows, CYK-1/Formin drives chiral symmetry breaking of the flow. Altogether, our work provides mechanistic insight into the role of Myosins and Formins in organismal left–right symmetry breaking.

How could CYK-1/Formin activity in RhoA foci promote in-plane torque generation with clockwise handedness? One attractive possibility is that the Formins themselves generate the active torque while elongating actin filaments. Due to the helical nature of filamentous actin, rotationally constrained Formins rotate the actin filaments that they are elongating in vitro (43). If CYK-1/Formins in active RhoA foci are rotationally constrained, actin filaments elongated in opposite directions will counterrotate (Fig. 5G). In turn, this would result in a large-scale torque with a clockwise handedness if a difference in friction between two sides of the cortical layer is present, e.g., the cortex experiencing lower friction with the membrane than with the cytosol. The rotating active RhoA patch could be compared to a Segway (or a military tank, but the authors prefer pacifist allegories) rotating on the spot. In this analogy, the wheels represent oppositely oriented actin filaments and their counterrotation will result in an in-plane rotation of the structure as a whole (RhoA patch or Segway).

Following this proposition, we expect active RhoA foci to be at the center of polar actin asters (Fig. 5G). To test this we have performed structured illumination microscopy–total internal reflection fluorescence (SIM-TIRF) superresolution microscopy on embryos producing Lifeact-mKate2 and NMY-2/Myosin::GFP. Although actin filaments often appear isotropically distributed, we observe clear aster-like topologies around many of the active RhoA foci (Movies S30 and S31 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Notably, it has been shown that in vitro reconstituted contractile actin networks have the propensity to self-organize into polar asters, with Myosins and actin plus ends at the aster center (72). Even though the aster-like structures in the C. elegans cortex are far from ideal asters, they could, on average, still facilitate in-plane torque generation in this manner. Moreover, for a net torque with consistent handedness an aster-like organization might not be necessary. In fact, any organization in which densely clustered Formins elongate actin filaments in opposite directions could be sufficient to generate in-plane torques. Consistent with this hypothesis are the findings that cortical flow chirality is increased upon 1) elevated RhoA activity, in which active RhoA patches are larger (61), and 2) expression of constitutively active CYK-1/Formin, in which CYK-1/Formin clusters form in a RhoA-independent manner. Similarly, earlier reports in cultured cells have shown that Formins clustered at peripheral adhesion sites, that are elongating actin filaments toward the cell center, are driving chiral in-plane swirling (26, 73). Taken together, we suggest that an organization in which actin filaments elongate away from Formins in opposite directions generates active torques (Fig. 5G).

Although the Formin clustering proposition provides a possible mechanism for chiral symmetry breaking, several open questions remain. First, how could actin filaments in a highly cross-linked actomyosin cortex rotate? Previous in vitro studies have shown that, when both the Formin and the actin filament are rotationally constrained, Formins stall actin polymerization (74, 75) and this would attenuate their ability to generate torques in vivo. Second, what is the role of Myosins in active torque generation? Because NMY-2 activity is required for actomyosin flows to emerge, Formin activity itself is not sufficient to generate chiral counterrotatory flows. Interestingly, in a recent study Noselli and coworkers (44) reported that the Formin DAAM is required for Myosin 1D (Myo1D)-driven left–right patterning of the Drosophila body plan. Their biochemical analysis revealed that Myo1D and DAAM physically interact, suggesting that Myosins and Formins could influence their activities reciprocally. Although NMY-2 is a different type of Myosin, our finding that NMY-2 and CYK-1/Formin reside in the same active RhoA foci could point out common regulatory mechanisms. Notably, numerous Formins have been shown to be mechanosensitive and the Diaphanous-like Formin mDia1 speeds up polymerization when pulling force is exerted on the actin filament (75–77). In the in vivo cortex, NMY-2 motors generate contractility and hence are likely candidates for providing pulling forces. Therefore, NMY-2–driven force generation could help alleviate Formins from the stall, allowing them to again drive polymerization and thereby generate active torques. Future studies may be aimed at understanding how the complex, and highly regulated, molecular interplay between Formins and Myosins facilitates active torque generation.

Materials and Methods

Worm Strains and Culture.

C. elegans strains were cultured using standard culture conditions (78) and maintained at 20 °C, apart from cyk-1(or596ts) mutants, which were maintained at 15 °C. See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for a list of alleles and transgenes.

Molecular Cloning and Generation of Transgenes.

To generate constitutively active cyk-1/Formin we fused residues 700 to 1,437 of CYK-1/Formin to the C terminus of PH-GFP. DNA plasmid was injected at 20 ng/L into the gonad of young adults that expressed lifeact-mKate2 or gesSi48[mCherry-ani-1(AHPH)]. For detailed cloning procedures see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods. Injected worms were grown at 25 °C for 6 to 7 h and their progeny was imaged at room temperature (22 °C). To generate the mCherry::ani-1(AH-PH) transgene, ani-1(AH-PH) (63) was fused to mCherry. Transgenesis was done using Mos SCI into the ttTi5605 site (79).

RNA Interference.

All RNAi treatments were performed by feeding as previously described (80). To titrate the RNAi strength, worms were fed for different amounts of hours. For details on RNAi experiments see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Image Acquisition.

Spinning disk microscopy was done using a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope (speckle microscopy) or a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 (the rest of the SD microscopy) equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 scan. SIM-TIRF microscopy was done using a Deltavision OMX. Cherry temp stage (Cherry Biotech) was used for recordings at temperatures other than 22 °C. See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for microscopy details, mounting methods, and image analysis methods.

Fitting the Hydrodynamic Model.

Hydrodynamic equations of motion were fitted to the experimentally measured vx and vy profiles as previously described (7) and error estimates were obtained by bootstrapping. See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods for further details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Canman for sharing cyk-1(or596ts); Bob Goldstein for nmy-2(cp8[nmy-2::GFP]) and nmy-2(cp52[nmy-2::mKate2); Tony Hyman for the mCherry-tubulin strain and mlc-4 and ect-2 RNAi clones; Martin Harterink and Sander van den Heuvel for PH-GFP-LOV2 plasmid; the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for the ect-2(gf) mutant and xsSi5[GFP-ani-1(AH-PH)]; Addgene for pJA281, pJA245, pCM1.36, pCFJ150, and pCFJ1415 plasmids; and Julie Ahringer and Source BioScience for L4440, rga-3, and cyk-1/Formin RNAi clones. We also thank Friederike Thonwart for assistance with molecular biology, GE-Deltavision and its representatives for having the Deltavision OMX SIM-TIRF system available for the 2018 Woods Hole Physiology course, and Sylvia Hurlimann for capturing SIM-TIRF movies during this course. Furthermore, we thank Jonas Neipel for valuable discussion on the hydrodynamic theory and Anne Grapin-Botton, Arghyadip Mukherjee, Ján Sabó, Jonas Neipel, and Zdeněk Lánský for critical reading of the manuscript. T.C.M. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization long-term fellowship ALTF 1033-2015 and a Nederlandse organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Rubicon fellowship 825.15.010. L.G.P. was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant 641639. S.W.G. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SPP 1782, GSC 97, GR 3271/2, GR 3271/3, GR 3271/4) and the European Research Council (Grant 742712).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2021814118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The raw data generated in this study is made publicly available: Speckle microscopy movies can be downloaded from CaltechDATA at https://data.caltech.edu/records/1442 (81). All other movies and micrographs can be downloaded from the Max Planck Society at https://dx.doi.org/10.17617/3.61 (82).

References

- 1.Brown N. A., Wolpert L., The development of handedness in left/right asymmetry. Development 109, 1–9 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Géminard C., González-Morales N., Coutelis J. B., Noselli S., The myosin ID pathway and left-right asymmetry in Drosophila. Genesis 52, 471–480 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hozumi S., et al. , An unconventional myosin in Drosophila reverses the default handedness in visceral organs. Nature 440, 798–802 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaki M., Sasamura T., Matsuno K., Cell chirality drives left-right asymmetric morphogenesis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 6, 34 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato K., et al. , Left-right asymmetric cell intercalation drives directional collective cell movement in epithelial morphogenesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 10074 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spéder P., Ádám G., Noselli S., Type ID unconventional myosin controls left-right asymmetry in Drosophila. Nature 440, 803–807 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naganathan S. R., Fürthauer S., Nishikawa M., Jülicher F., Grill S. W., Active torque generation by the actomyosin cell cortex drives left-right symmetry breaking. eLife 3, e04165 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naganathan S. R., Middelkoop T. C., Fürthauer S., Grill S. W., Actomyosin-driven left-right asymmetry: From molecular torques to chiral self organization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 38, 24–30 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pohl C., Bao Z., Chiral forces organize left-right patterning in C. elegans by uncoupling midline and anteroposterior axis. Dev. Cell 19, 402–412 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schonegg S., Hyman A. A., Wood W. B., Timing and mechanism of the initial cue establishing handed left-right asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Genesis 52, 572–580 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugioka K., Bowerman B., Combinatorial contact cues specify cell division orientation by directing cortical myosin flows. Dev. Cell 46, 257–270.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shibazaki Y., Shimizu M., Kuroda R., Body handedness is directed by genetically determined cytoskeletal dynamics in the early embryo. Curr. Biol. 14, 1462–1467 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison A., et al. , Formin is associated with left-right asymmetry in the pond snail and the frog. Curr. Biol. 26, 654–660 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuroda R., et al. , Diaphanous gene mutation affects spiral cleavage and chirality in snails. Sci. Rep. 6, 34809 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abe M., Kuroda R., The development of CRISPR for a mollusc establishes the formin Lsdia1 as the long-sought gene for snail dextral/sinistral coiling. Development 146, dev175976 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gros J., Feistel K., Viebahn C., Blum M., Tabin J. C., Cell movements at Hensen’s Node establish left/right asymmetric gene expression in the chick. Science 324, 941–944 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juan T., et al. , Myosin1D is an evolutionarily conserved regulator of animal left-right asymmetry. Nat. Commun. 9, 1942 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.et al. , Conserved roles for cytoskeletal components in determining laterality. Integr. Biol. 8, 267–286 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noël E. S., et al. , A Nodal-independent and tissue-intrinsic mechanism controls heart-looping chirality. Nat. Commun. 4, 2754 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu D., et al. , Localization and loss-of-function implicates ciliary proteins in early, cytoplasmic roles in left-right asymmetry. Dev. Dyn. 234, 176–189 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray P., et al. , Intrinsic cellular chirality regulates left–right symmetry breaking during cardiac looping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E11568–E11577 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tingler M., et al. , A conserved role of the unconventional myosin 1d in laterality determination. Curr. Biol. 28, 810–816.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin A. S., et al. , Epithelial cell chirality revealed by three-dimensional spontaneous rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12188–12193 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagmann J., Pattern formation and handedness in the cytoskeleton of human platelets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3280–3283 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamada A., Kawase S., Murakami F., Kamiguchi H., Autonomous right-screw rotation of growth cone filopodia drives neurite turning. J. Cell Biol. 188, 429–441 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tee Y. H., et al. , Cellular chirality arising from the self-organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 445–457 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J., et al. , Polarity reveals intrinsic cell chirality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9296–9300 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamanaka H., Kondo S., Rotating pigment cells exhibit an intrinsic chirality. Gene Cell. 20, 29–35 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen T. H., et al. , Left-right symmetry breaking in tissue morphogenesis via cytoskeletal mechanics. Circ. Res. 110, 551–559 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K., Hiraiwa T., Shibata T., Cell chirality induces collective cell migration in epithelial sheets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 188102 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taniguchi K., et al. , Chirality in planar cell shape contributes to left-right asymmetric epithelial morphogenesis. Science 333, 339–341 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danilchik M. V., Brown E. E., Riegert K., Intrinsic chiral properties of the Xenopus egg cortex: An early indicator of left-right asymmetry. Development 133, 4517–4526 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lebreton G., et al. , Molecular to organismal chirality is induced by the conserved myosin 1D. Science 362, 949–952 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henley C. L., Possible origins of macroscopic left-right asymmetry in organisms. J. Stat. Phys. 148, 740–774 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pimpale L. G., Middelkoop T. C., Mietke A., Grill S. W., Cell lineage-dependent chiral actomyosin flows drive cellular rearrangements in early Caenorhabditis elegans development. eLife 9, e54930 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Depue R. H., Rice R. V., F-actin is a right-handed helix. J. Mol. Biol. 12, 302–303 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jegou A., Romet-Lemonne G., The many implications of actin filament helicity. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 102, 65–72 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yusuf Ali M., et al. Myosin v is a left-handed spiral motor on the right-handed actin helix. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 464–467 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beausang J. F., Schroeder H. W., Nelson P. C., Goldman Y. E., Twirling of actin by myosins II and V observed via polarized TIRF in a modified gliding assay. Biophys. J. 95, 5820–5831 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishizaka T., Yagi T., Tanaka Y., Ishiwata S., Right-handed rotation of an actin filament in an in vitro motile system. Nature 361, 269–271 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sase I., Miyata H., Ishiwata S., Kinosita K., Axial rotation of sliding actin filaments revealed by single-fluorophore imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 5646–5650 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilfan A., Twirling motion of actin filaments in gliding assays with nonprocessive myosin motors. Biophys. J. 97, 1130–1137 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizuno H., et al. , Rotational movement of the formin mDia1 along the double helical strand of an actin filament. Science 331, 80–83 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chougule A., et al. , The Drosophila actin nucleator DAAM is essential for left-right asymmetry. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008758 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fürthauer S., Strempel M., Grill S. W., Jülicher F., Active chiral fluids. Eur. Phys. J. E 35, 89 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fürthauer S., Strempel M., Grill S. W., Jülicher F., Active chiral processes in thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 048103 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood W. B., Evidence from reversal of handedness in C. elegans embryos for early cell interactions determining cell fates. Nature 349, 536–538 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naganathan S. R., et al. , Morphogenetic degeneracies in the actomyosin cortex. eLife 7, e37677 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaatri A., Perry J. A., Maddox A. S., Septins and a formin have distinct functions in anaphase chiral cortical rotation in the C. elegans zygote. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2020). 10.1101/2020.08.07.242123 (Accessed 27 April 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Swan K. A., et al. , cyk-1: A C. elegans FH gene required for a late step in embryonic cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2017–2027 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies T., et al. , High-resolution temporal analysis reveals a functional timeline for the molecular regulation of cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 30, 209–223 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickinson D. J., Ward J. D., Reiner D. J., Goldstein B.., Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat. Methods 10, 1028–1034 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Higashida C., et al. , Actin polymerization-driven molecular movement of mDia1 in living cells. Science 303, 2007–2010 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe N., Kato T., Fujita A., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S., Cooperation between mDia1 and ROCK in Rho-induced actin reorganization. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 136–143 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neidt E. M., Skau C. T., Kovar D. R., The cytokinesis formins from the nematode worm and fission yeast differentially mediate actin filament assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 23872–23883 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mi-Mi L., Votra S., Kemphues K., Bretscher A., Pruyne D., Z-line formins promote contractile lattice growth and maintenance in striated muscles of C. elegans. J. Cell Biol. 198, 87–102 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergmann D. C., et al. , Embryonic handedness choice in C. elegans involves the G protein GPA-16. Development 130, 5731–5740 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kühn S., Geyer M., Formins as effector proteins of Rho GTPases. Small GTPases 5, e29513 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell K. R., et al. , Novel cytokinetic ring components drive negative feedback in cortical contractility. Mol. Biol. Cell 31, 1623–1636 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maddox A. S., Habermann B., Desai A., Oegema K., Distinct roles for two C. elegans anillins in the gonad and early embryo. Development 132, 2837–2848 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michaux J. B., Robin F. B., McFadden W. M., Munro E. M., Excitable RhoA dynamics drive pulsed contractions in the early C. elegans embryo. J. Cell Biol. 217, 4230–4252 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nishikawa M., Naganathan S. R., Jülicher F., Grill S. W., Controlling contractile instabilities in the actomyosin cortex. eLife 6, e19595 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tse Y. C., et al. , RhoA activation during polarization and cytokinesis of the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo is differentially dependent on NOP-1 and CYK-4. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 4020–4031 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schonegg S., Hyman A. A., CDC-42 and RHO-1 coordinate acto-myosin contractility and PAR protein localization during polarity establishment in C. elegans embryos. Development 133, 3507–3516 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jenkins N., Saam J. R., Mango S. E., CYK-4/GAP provides a localized cue to initiate anteroposterior polarity upon fertilization. Science 313, 1298–1301 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Munro E., Bowerman B., Cellular symmetry breaking during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a003400 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Danuser G., Waterman-Storer C. M., Quantitative fluorescent speckle microscopy of cytoskeleton dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35, 361–387 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costache V., et al. , Rapid assembly of a polar network architecture by formins downstream of RhoA pulses drives efficient cortical actomyosin contractility. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2020). 10.1101/2020.12.08.406298 (Accessed 27 April 2021). [DOI]

- 69.Canevascini S., Marti M., Fröhli E., Hajnal A., The Caenorhabditis elegans homologue of the proto-oncogene ect-2 positively regulates RAS signalling during vulval development. EMBO Rep. 6, 1169–1175 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh D., Odedra D., Dutta P., Pohl C., Mechanical stress induces a scalable switch in cortical flow polarization during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs231357 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reymann A. C., Staniscia F., Erzberger A., Salbreux G., Grill S. W., Cortical flow aligns actin filaments to form a furrow. eLife 5, e17807 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wollrab V., et al. , Polarity sorting drives remodeling of actin-myosin networks. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs219717 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jalal S., et al. , Actin cytoskeleton self-organization in single epithelial cells and fibroblasts under isotropic confinement. J. Cell Sci. 132, jcs220780 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suzuki E. L., et al. , Geometrical constraints greatly hinder formin mDia1 activity. Nano Lett. 20, 22–32 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu M., et al. , MDia1 senses both force and torque during F-actin filament polymerization. Nat. Commun. 8, 1650 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Courtemanche N., Lee J. Y., Pollard T. D., Greene E. C., Tension modulates actin filament polymerization mediated by formin and profilin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9752–9757 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jégou A., Carlier M. F., Romet-Lemonne G., Formin mDia1 senses and generates mechanical forces on actin filaments. Nat. Commun. 4, 1883 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brenner S., The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.FrøkjÃęr-Jensen C., et al. , Single-copy insertion of transgenes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Genet. 40, 1375–1383 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Timmons L., Court D. L., Fire A., Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263, 103–112 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quintero-Cadena P., Middelkoop T. C., Fluorescence microscopy data of CYK1-GFP embryos in early C. elegans embryo actomyosin flow (Version 1.0). CaltechDATA. 10.22002/D1.1442. Deposited 4 June 2020. [DOI]

- 82.Middelkoop T. C., Data for paper “CYK-1/Formin activation in cortical RhoA signaling centers promotes organismal left–right symmetry breaking.” Edmond. 10.17617/3.61. Deposited 26 April 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data generated in this study is made publicly available: Speckle microscopy movies can be downloaded from CaltechDATA at https://data.caltech.edu/records/1442 (81). All other movies and micrographs can be downloaded from the Max Planck Society at https://dx.doi.org/10.17617/3.61 (82).