Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes (also known as assisted living facilities) is largely unknown. We examined the association between home-and community-level characteristics and the risk of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes since the beginning of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS:

We conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of licensed retirement homes in Ontario, Canada, from Mar. 1 to Dec. 18, 2020. Our primary outcome was an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection (≥ 1 resident or staff case confirmed by validated nucleic acid amplification assay). We used time-dependent proportional hazards methods to model the associations between retirement home– and community-level characteristics and outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

RESULTS:

Our cohort included all 770 licensed retirement homes in Ontario, which housed 56 491 residents. There were 273 (35.5%) retirement homes with 1 or more outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection, involving 1944 (3.5%) residents and 1101 staff (3.0%). Cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were distributed unevenly across retirement homes, with 2487 (81.7%) resident and staff cases occurring in 77 (10%) homes. The adjusted hazard of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a retirement home was positively associated with homes that had a large resident capacity, were co-located with a long-term care facility, were part of larger chains, offered many services onsite, saw increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and were located in a region with a higher community-level ethnic concentration.

INTERPRETATION:

Readily identifiable characteristics of retirement homes are independently associated with outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection and can support risk identification and priority for vaccination.

Frail older adults living in congregate care settings have been at the centre of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada and internationally.1,2 Long-term care facilities — whose residents are the congregate living population most affected by COVID-19 — have been the subject of immense scientific and public interest during the pandemic.3 Retirement homes (often known as assisted living facilities) have received far less examination despite also housing many vulnerable older adults.4–7 In contrast to long-term care facilities, retirement homes are private residential complexes that provide a range of supportive care and lifestyle services that are purchased out of pocket by residents or their families.8 Although residents of retirement homes access supportive care services, they are substantially less frail and dependent than residents of long-term care homes.5 Inconsistent regulation of these facilities throughout Canada and the United States has limited research into the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes.9

There are 770 licensed retirement homes in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, that house more than 50 000 older adults, a population size that approaches the number of Ontario residents of long-term care homes.10 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, the number of positive cases and deaths in retirement homes has continued to grow. As of Apr. 11, 2021, retirement home residents accounted for about 8% of deaths from COVID-19 in Ontario (596/7552).11 Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection surged in retirement homes during the first and second waves in Canada and the US,11,12 and there has been limited examination in the literature beyond early reports of case surveillance.13

We examined the association between home- and community-level characteristics and the risk of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in Ontario’s retirement homes. Consistent with our previous population-level work in Ontario long-term care homes,2,14 we hypothesized that home size and regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection would be associated with the risk of an outbreak.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study across all retirement homes in Ontario, Canada, from Mar. 1, 2020, to Dec. 18, 2020, spanning the entirety of Ontario’s first wave as well as early data from the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.15 We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline and the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data (RECORD) statement guidelines.16,17 In Ontario, retirement homes are defined in legislation (similar to other North American jurisdictions) as residential complexes that are occupied primarily by people aged 65 years or older and that have at least 2 care services available (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.202756/tab-related-content).18,19

Data sources

We obtained data from the Ontario Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority (RHRA) and Ontario Ministry of Health, as part of the Ontario COVID-19 Modelling Consensus Table. We obtained home-level daily case counts of SARS-CoV-2 infections and deaths from COVID-19 among retirement home residents and staff (in home or hospital) from the RHRA, through its COVID-19 Tracking Tool. We collected these data, which include the date on which an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection was declared and deemed resolved, through daily direct inquires by the RHRA and through self-reports by licensed retirement homes to the RHRA. These data are publicly reported.11 Licensed retirement homes are required to report outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection to the RHRA at the same time they are reported to their local public health units. Data from the tracking tool correlated closely with other provincial data sources, including the integrated Public Health Information System, the Ontario Laboratories Information System, and a death database maintained by the Ontario Chief Coroner’s office, and have been used in COVID-19-related research on long-term care homes.2,14

Exposures and outcome

We obtained data on home-level exposures from the provincial registry of licensed retirement homes, which contains data on resident capacity, co-location with a long-term care facility, and the availability of care services onsite, for all retirement homes in Ontario. The RHRA is legislatively mandated to maintain the registry as the provincial retirement homes regulator. Home size was based on reported resident capacity and assigned to quintiles. Co-location of the retirement home with a long-term care facility was identified by RHRA records as those homes sharing the same physical building or situated on the same site. Information on chain ownership was supplied by the RHRA, and homes were classified as being members of a small (2–5 homes), medium (6–20 homes) or large (> 20 homes) chain, or not part of a chain. The RHRA maintains a list of 13 services offered (Appendix 1) and a home’s services were summed and assigned to the following categories: ≤ 6, 7, 8, or ≥ 9 services.

We obtained data on home-level occupancy, staffing counts and external care providers from an RHRA survey of all retirement homes, conducted in May 2020 (home-level response was 92.7%). External care providers come into the home either as contracted workers of the publicly funded home care program, or by private pay arrangements with residents. We calculated a staff-to-resident ratio comprising both types of external care providers based on the response values from the home survey and assigned the ratios to quartiles.

We obtained the daily incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection across Ontario’s 36 public health regions from Public Health Ontario’s integrated Public Health Information System.20,21 We calculated time-varying incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection each day as the rolling 14-day incidence per 1000 population for the public health unit in which the retirement home resided. We chose a rolling 14-day incidence based on the trend of community incidence rates (Appendices 2 and 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.202756/tab-related-content). We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a 30-day time period, as well as by centring the index day in the rolling average period. We obtained linked data on community-level median household income and ethnic concentration from the Ontario Ministry of Health, based on the 2016 Canadian Census and the Ontario Marginalization Index, respectively. We obtained the neighbourhood-level ethnic concentration surrounding each retirement home; this is defined as the combined proportions of residents who were not White or Indigenous, and immigrants who had arrived in Canada within the past 5 years, based on the 2016 Canadian Census.22,23 We calculated the population size of the community in which each retirement home resided using Statistics Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File Plus (PCCF+), through postal codes from the Canada Post Corporation that were current up to and including November 2018; communities with a population size of < 10 000 individuals were considered rural.24

Our primary outcome was an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection (≥ 1 resident or staff case confirmed by validated nucleic acid amplification assay).

Statistical analysis

We computed summary statistics to compare, by outbreak status, and retirement home– and community-level characteristics. We used the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. We calculated case fatality rates as the proportion of residents who died of COVID-19 compared with the total number of residents infected with SARS-CoV-2.

We used Cox proportional hazards to model the associations between retirement home– and community-level characteristics and the risk of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Community incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was a time-varying covariate, with all other measures being fixed. A retirement home was at risk of experiencing an event on all days (Mar. 1 to Dec. 18, 2020), except for days in which the home was experiencing an outbreak. When an outbreak was over, the home returned to being at risk for a future outbreak. To account for correlation among observations within public health units and multiple outbreaks within the same retirement homes, we applied a robust sandwich estimator for the covariance matrix. We forced all variables into an adjusted model to add clarity around all effects of interest. Finally, we examined 2-way interactions among selected covariates. We examined the proportionality of hazards assumption using Kaplan–Meier plots and time-varying covariates. We collapsed some explanatory variables represented as quintiles to 3 levels to comply with proportionality requirements.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board.

Results

Infections and deaths

The analysis included all 770 licensed retirement homes in Ontario as of Mar. 1, 2020. Overall, 273 (35.5%) retirement homes experienced 1 or more outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection as of Dec. 18, 2020, with 195 (25.3%) having 1 outbreak, 65 (8.4%) having 2, 10 (1.3%) having 3, and 3 (0.4%) having 4 outbreaks. Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in this period involved 1944 (3.5%) infected residents and 1101 infected staff (3.0%) (Table 1). A total of 139 outbreaks occurred between March and the end of May, 32 from June through August, and 196 from September to December 18, 2020 (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.202756/tab-related-content). Almost half of all outbreaks involved both staff and resident cases, with outbreaks involving staff being more common than those involving residents. The crude cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among residents was 34.3 per thousand. In homes with a resident infection, the median number of residents infected was 4 (interquartile range [IQR] 1–15). SARS-CoV-2 infection was distributed unevenly across retirement homes: 2487 (81.7%) resident and staff cases occurred in 77 (10%) of homes. There were 87 (11.3%) retirement homes with outbreaks resulting in 1 or more resident deaths, accounting for a total of 336 deaths of residents from COVID-19 (5.9 per 1000 residents in Ontario) and a case fatality rate of 17.3%.

Table 1:

Description of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection and related deaths in retirement homes in Ontario

| Characteristic | No. (%)* of homes with outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection |

|---|---|

| By retirement home | n = 770 |

| ≥ 1 outbreaks | 273 (35.5) |

| Total outbreaks | n = 367 |

| No. of outbreaks involving both residents and staff | 148 (40.3) |

| No. of outbreaks involving residents only | 75 (20.4) |

| No. of outbreaks involving staff only | 144 (39.2) |

| Median no. of cases per facility with a resident infection (IQR) | 4 (1–15) |

| No. of homes with ≥ 1 COVID-19 deaths, n | 87 |

| Median proportion of residents who died per facility with a resident death, % (IQR) | 2.9 (1.5–7.6) |

| Median no. of deaths per facility with 1 or more deaths (IQR) | 3 (1–4) |

| By SARS-CoV-2 infection | n = 3045 |

| No. of staff infections | 1101 (36.2) |

| No. of resident infections | 1944 (63.8) |

| Cumulative incidence of COVID-19 resident cases (per thousand RH residents) | 34.4 |

| Median proportion of residents infected per facility with a resident infection, % (IQR) | 4.9 (1.8–19.7) |

| No. of deaths from COVID-19 | 336 |

| COVID-19 death rate (per thousand RH residents) | 5.9 |

| Case fatality rate, % | 17.3 |

Note: IQR = interquartile range, RH = retirement home.

Unless otherwise specified.

Characteristics of retirement home by outbreak status

Retirement homes housed 56 491 residents, with an average of 73 residents and 48 staff per home and an overall occupancy rate of 74.2% (Table 2). Most retirement homes had external care providers who entered the home daily, were part of a privately owned chain, were located in communities with larger populations and lower ethnic concentration, and offered more than 6 services to their residents onsite. A minority of retirement homes were co-located with a long-term care facility. Compared with retirement homes without outbreaks, those that experienced 1 or more outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection were more likely to have larger resident capacity, be part of a larger chain, have external care providers entering the home on a daily basis, have more services available to their residents onsite, and be located in larger communities with a higher ethnic concentration.

Table 2:

Characteristics of retirement homes by status of outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Measures | All homes | No. (%)* of homes with ≥ 1 outbreak† | Homes with no outbreaks | p value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of homes | 770 (100) | 273 (35.5) | 497 (64.5) | |

| No. (%) of residents§ | 56 491 | 25 920 (45.9) | 30 571 (54.1) | |

| Mean no. of residents per facility§ | 73.4 | 94.9 | 61.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Mean no. of total staff per facility† | 48.1 | 66.2 | 38.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Facility characteristics | ||||

| Total resident capacity, n (%) | ||||

| < 45 | 149 (19.4) | 22 (8.1) | 127 (25.6) | < 0.0001 |

| 45–74 | 151 (19.6) | 32 (11.7) | 119 (23.9) | |

| 75–109 | 148 (19.2) | 57 (20.9) | 91 (18.3) | |

| 110–151 | 167 (21.7) | 74 (27.1) | 93 (18.7) | |

| ≥ 152 | 155 (20.1) | 88 (32.2) | 67 (13.5) | |

| Mean occupancy rate§ | 74.2 | 73.3 | 74.7 | 0.509 |

| Mean no. of suites | 84.3 | 111.0 | 69.6 | < 0.0001 |

| No. (%) co-located with a nursing home or long-term care facility | 101 (13.1) | 38 (13.9) | 63 (12.7) | 0.625 |

| Mean no. (%) of external care providers who enter facility daily,§ among those with a value | 5.15 | 5.88 | 4.69 | < 0.0001 |

| 0 | 113 (14.7) | 28 (10.3) | 85 (17.1) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 1, exact number unknown | 86 (11.2) | 35 (12.8) | 51 (10.3) | |

| 1 or 2 | 172 (22.3) | 50 (18.3) | 122 (24.6) | |

| 3–6 | 247 (32.1) | 96 (35.2) | 151 (30.4) | |

| ≥ 7 | 96 (12.5) | 51 (18.7) | 45 (9.1) | |

| Missing | 56 (7.3) | 13 (4.8) | 43 (8.7) | |

| No. (%) of active staff-to-resident ratio§ | ||||

| < 0.49 | 178 (23.1) | 52 (19.1) | 126 (25.4) | 0.0004 |

| 0.49–0.64 | 186 (24.2) | 59 (21.6) | 127 (25.6) | |

| 0.64–0.84 | 175 (22.7) | 65 (23.8) | 110 (22.1) | |

| > 0.84 | 166 (21.6) | 81 (29.7) | 85 (17.1) | |

| Missing | 65 (8.4) | 16 (5.9) | 49 (9.9) | |

| No. (%) of homes in chain | ||||

| Not a chain | 305 (39.6) | 76 (27.8) | 229 (46.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Small (2–5) | 87 (11.3) | 22 (8.1) | 65 (13.1) | |

| Medium (6–20) | 174 (22.6) | 72 (26.4) | 102 (20.5) | |

| Large (> 20) | 204 (26.5) | 103 (37.7) | 101 (20.3) | |

| No. (%) of available services¶ | ||||

| ≤ 6 | 165 (21.4) | 30 (11.0) | 135 (27.2) | < 0.0001 |

| 7 | 275 (35.7) | 91 (33.3) | 184 (37.0) | |

| 8 | 176 (22.9) | 64 (23.4) | 112 (22.5) | |

| ≥ 9 | 154 (20.0) | 88 (32.2) | 66 (13.3) | |

| Regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection (per 1000 residents)**, n (%) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (0.567–1.552) | 57 (7.4) | 5 (1.8) | 52 (10.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Quintile 2 (1.553–3.364) | 90 (11.7) | 11 (4.0) | 79 (15.9) | |

| Quintile 3 (3.365–6.023) | 134 (17.4) | 29 (10.6) | 105 (21.1) | |

| Quintile 4 (6.024–9.554) | 178 (23.1) | 50 (18.3) | 128 (25.8) | |

| Quintile 5 (9.555–25.409) | 311 (40.4) | 178 (65.2) | 133 (26.8) | |

| Community population size, n (%) | ||||

| ≥ 500 000 | 349 (45.3) | 181 (66.3) | 168 (33.8) | < 0.0001 |

| 10 000–499 | 999 295 (38.3) | 73 (26.7) | 222 (44.7) | |

| < 10 000 | 126 (16.4) | 19 (7.0) | 107 (21.5) | |

| Median household income in dollars, n (%) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (14 777–51 925) | 181 (23.5) | 63 (23.1) | 118 (23.7) | 0.293 |

| Quintile 2 (52 267–68 032) | 183 (23.8) | 64 (23.4) | 119 (23.9) | |

| Quintile 3 (68 352–84 160) | 162 (21.0) | 52 (19.1) | 110 (22.1) | |

| Quintile 4 (84 352–103 424) | 149 (19.4) | 51 (18.7) | 98 (19.7) | |

| Quintile 5 (103 834–251 008) | 95 (12.3) | 43 (15.8) | 52 (10.5) | |

| Ethnic concentration‡, n (%) | ||||

| Quintile 1 (least concentrated) | 167 (21.7) | 26 (9.5) | 141 (28.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Quintile 2 | 200 (26.0) | 48 (17.6) | 152 (30.6) | |

| Quintile 3 | 166 (21.6) | 60 (22.0) | 106 (21.3) | |

| Quintile 4 | 145 (18.8) | 84 (30.8) | 61 (12.3) | |

| Quintile 5 (most concentrated) | 92 (12.0) | 55 (20.2) | 37 (7.4) | |

Unless otherwise specified.

Defined as ≥ 1 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection among resident or staff.

Defined by the Ontario Marginalization Index as the proportion of residents who were not White or Indigenous and the proportion of immigrants who arrived in Canada within the past 5 years.

As of May 2020.

See Appendix 1 for the full list of services, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.202756/tab-related-content.

Mar. 1 to Dec. 18, 2020. Quintiles are based on the Dec. 18, 2020, distribution among 34 public health units.

Risk of an outbreak

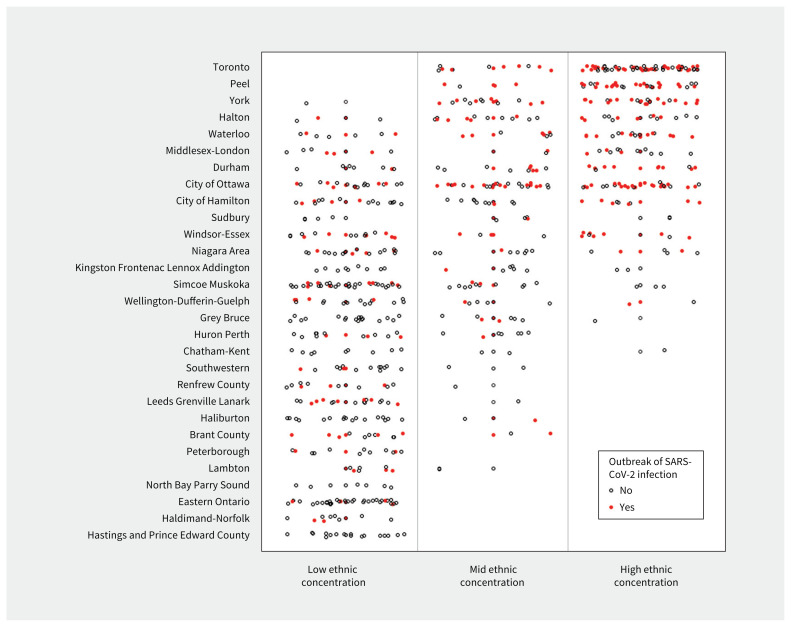

Increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection were associated with outbreaks in retirement homes, where an increase of 1 case per 1000 people in the previous 14 days was associated with a 1.6-fold increase in the hazard of an outbreak (Table 3). The number of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection was more sensitive to increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection during Wave 1 than in Wave 2 (Appendix 3). In addition to regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the adjusted hazard of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection was positively associated with homes that had a large resident capacity, were part of a larger chain, were co-located with a long-term care facility, offered many services onsite, and had a higher community-level ethnic concentration (Table 3). We observed more outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes with a higher community-level ethnic concentration across many public health regions (Figure 1).

Table 3:

Associations between facility and regional characteristics with time to outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection among residents*

| Characteristics | HR of outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection† (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR | Adjusted HR | |

| Regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection | ||

| Time-varying incidence in previous 14 d, increase in 1 case per 1000 | 2.03 (1.83–2.27) | 1.61 (1.42–1.83) |

| Facility characteristics | ||

| Total resident capacity | ||

| < 45 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 45–74 | 1.46 (0.86–2.49) | 1.53 (0.89–2.63) |

| 75–109 | 3.01 (1.87–4.85) | 2.36 (1.41–3.96) |

| 110–151 | 3.73 (2.35–5.93) | 3.24 (1.96–5.35) |

| ≥ 152 | 5.54 (3.52–8.73) | 3.56 (2.15–5.89) |

| Co-located with nursing home or LTC facility | 1.26 (0.90–1.75) | 1.66 (1.24–2.21) |

| No. of external care providers who enter facility daily | ||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. |

| ≥ 1, exact number unknown | 2.14 (1.34–3.42) | 0.82 (0.52–1.29) |

| 1 or 2 | 1.22 (0.79–1.88) | 0.90 (0.58–1.38) |

| 3–6 | 1.96 (1.32–2.92) | 0.94 (0.63–1.43) |

| ≥ 7 | 3.26 (2.11–5.02) | 1.06 (0.68–1.64) |

| Missing | 1.25 (0.65–2.40) | 1.19 (0.31–4.50) |

| Staff-to-resident ratio | ||

| < 0.49 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 0.49–0.64 | 1.18 (0.82–1.68) | 1.21 (0.90–1.63) |

| 0.65–0.84 | 1.40 (0.99–1.99) | 0.96 (0.71–1.29) |

| > 0.84 | 2.04 (1.48–2.82) | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) |

| Missing | 0.95 (0.54–1.65) | 1.04 (0.32–3.41) |

| Size of chain | ||

| Not a chain | Ref. | Ref. |

| Small (2–5) | 0.94 (0.59–1.49) | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) |

| Medium (6–20) | 1.94 (1.41–2.66) | 1.40 (1.03–1.89) |

| Large (> 20) | 2.22 (1.67–2.95) | 1.34 (0.98–1.83) |

| No. of RH services available‡ | ||

| ≤ 6 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 7 | 1.95 (1.31–2.91) | 1.22 (0.82–1.83) |

| 8 | 2.29 (1.50–3.48) | 1.57 (1.05–2.36) |

| ≥ 9 | 4.65 (3.13–6.91) | 2.31 (1.55 – 3.43) |

| Community population size, n (%) | ||

| ≥ 500 000 | 4.75 (3.00–7.52) | 1.21 (0.72–2.04) |

| 10 000–499 999 | 1.80 (1.01–2.94) | 0.94 (0.58–1.52) |

| < 10 000 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Median household income in dollars | ||

| Quintiles 1, 2 (14 777–68 032) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Quintile 3 (68 352–84 160) | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 1.01 (0.77–1.32) |

| Quintiles 4, 5 (84 352–251 008) | 1.12 (0.87–1.44) | 0.83 (0.68–1.04) |

| Ethnic concentration,§ n (%) | ||

| Quintiles 1, 2 (less concentrated) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Quintile 3 | 2.20 (1.58–3.06) | 1.31 (0.91–1.88) |

| Quintiles 4, 5 (more concentrated) | 4.02 (3.08–5.24) | 1.63 (1.14–2.32) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, LTC = long-term care, Ref. = reference category, RH = retirement home.

Mar. 1 to Dec. 18, 2020. Number of facilities: 770.

As of Dec. 18, 2020. Defined as ≥ 1 case of SARS-CoV-2 infection among residents or staff.

See Appendix 1 for the full list of services, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.202756/tab-related-content.

Defined by the Ontario Marginalization Index as the proportion of residents who were not White or Indigenous and the proportion of immigrants who arrived in Canada within the past 5 years.

Figure 1:

Outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection at retirement homes, by community-level ethnic concentration and public health unit region. Note: Public health unit regions with fewer than 5 retirement homes are excluded.

Interpretation

In this study of all 770 retirement homes in Ontario, Canada, we found that the hazard of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection was positively associated with increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and with homes that had a large resident capacity, were co-located with a long-term care facility, were part of larger chains, offered many services onsite, and were located in a region with a higher community-level ethnic concentration. We identified risk factors for outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes that can inform risk identification and vaccine priority at the provincial and regional levels, as has been done for the long-term care sector.25 We showed that a subset of retirement homes in Ontario have been severely affected by the pandemic, with case fatality rates approaching those of long-term care facilities.14,26

Consistent with findings regarding other congregate care environments,2,14,26,27 our results support that the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a public health region, larger chains of retirement homes and the size of home are risk factors for outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our findings are similar to the temporal relationship between community incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and outbreaks in long-term care homes.28 The rate of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Wave 2 was less sensitive to increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which suggests that mandatory surveillance testing and more local preventive measures introduced after Wave 1 were likely effective.

Larger homes were associated with a 3-fold increased risk of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection. They have more staff travelling in and out of the home to provide necessary services, and this likely increased the number of opportunities to seed an infection.29 The lack of an adjusted association between the number of external care providers entering the home daily and an outbreak might be explained by the fact that homes of the same size have comparable numbers of external care providers entering the facility.

Homes that offered 9 or more services had a 2.5-fold increase in risk for an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This likely reflects the additional exposure to SARS-CoV-2 associated with more direct and prolonged personal interactions between staff and residents who require a higher level of care. Our findings support limiting the number of different staff providing care and services within retirement homes, particularly external care providers who provide care to multiple clients across community settings. Improved surveillance testing for retirement home staff, essential caregivers and external care providers — not mandatory in all provinces — is also a crucial priority. Retirement homes that provide a high level of care (about 20%) should be identified by public health officials and prioritized for additional surveillance and vaccinations.

Retirement homes that are co-located with a long-term care facility had a more than 1.6-fold increase in risk for outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite provincial orders restricting work at multiple health care settings within a 14-day period, emerging evidence suggests that residual connectivity among congregate living settings may still exist.25,30,31 The association might be explained by temporary agency workers and contract staff who are exempted from the provincial order, or staff working in the co-located homes, commuting together. Reducing connectivity between retirement and long-term care homes remains a priority and may reduce the risk of outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection during successive waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethnic concentration in the community surrounding a retirement home was associated with the risk of an outbreak, even after adjusting for regional rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and community-level household income. Public Health Ontario reports show that ethnoculturally dense neighbourhoods have experienced disproportionately higher rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection.32 Congregate care settings with more residents who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups have reported higher cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection or deaths from COVID-19, or both.33

Limitations

We could not examine the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and ethnocultural characteristics in our analyses, and further individual-level data and analysis are needed to understand this mechanism.

As with many emerging and rapidly collected sources of data on COVID-19, we could not independently validate completeness with respect to SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 deaths at the home level. We also could not accurately account for temporal changes in infection prevention and control practices that may have influenced these results. Our study was limited by the lack of individual-level data on clinical, organizational and sociocultural characteristics that may differ across homes. Our adjustment for regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection may have caused overadjustment, given that some community cases may have been secondary to retirement home cases.

Conclusion

We found that the risk of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infection in retirement homes is positively associated with larger resident capacity, co-location with a long-term care facility, larger chains, a higher availability of services onsite, increases in regional incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the ethnic concentration of the neighbourhood in which the home is located. Limiting the number of different staff providing care and services within retirement homes and a reduction in staff connectivity between settings are modifiable factors that may reduce the risk of future outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. Kamil Malikov of the Ontario Ministry of Health’s Capacity Planning and Analytics Division for assistance with data acquisition.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Andrew Costa reports receiving support during the conduct of the study from the Juravinski Research Institute. Dr. Costa also reports receiving grants from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and payments or honoraria from CIHR and Florida Society for Post-Acute & Long-Term Care Medicine, outside the submitted work. Dr. Costa reports being a member of Ontario COVID-19 Congregate Care Setting Science Advisory Table Working Group, Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, Ontario Ministry of Health and the Government of Ontario, and is the Schlegel Chair in Clinical Epidemiology and Aging. George Heckman reports receiving fees from Merck for participation in an advisory board. Michael Himmer reports receiving support for attending a meeting. Adriane Castellino, Chloe Ma and Paul Pham report being employees of the Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority (RHRA), an independent, self-funded, not-for-profit regulator mandated by the Ontario government; members of RHRA’s Board of Directors include executives of Chartwell Retirement Residences, Diversicare Canada and Amica Senior Lifestyles, which represent the retirement home industry on the Board.. Derek Manis reports receiving Mitacs Accelerate Fellowship, during the conduct of this study, and student membership of the Board of Directors of the Justice Emmett Hall Memorial Foundation. Samir Sinha reports receiving consulting fees from Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations or educational events from the Alberta Continuing Care Association, BC Care Providers Association, Canadian Association for Long-Term Care, Canadian Institutes of Health Research Best Brains Exchange Program on the Regulation of the Ontario Retirement Homes Sector, Long-Term Care Association of Manitoba, New Brunswick Association of Nursing Homes, Ontario Long-Term Care Association and the Ontario Retirement Communities Association. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Andrew Costa, Jeff Poss, Derek Manis, Aaron Jones, Nathan Stall and Kevin Brown contributed to the original conception and design of the work. All of the authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. Jeff Poss performed the statistical analysis. Andrew Costa drafted the manuscript. All of the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was funded by the Juravinski Research Institute, in partnership with the St. Joseph’s Healthcare Foundation, McMaster University and the Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation, Ontario, Canada.

Data sharing: The study protocol and statistical code are available on request (e-mail: acosta@mcmaster.ca), with the understanding that the computer programs may rely on coding templates or macros that may be inaccessible or require modification. The data sets from this study are held securely at the Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority and Ontario Ministry of Health’s Capacity Planning and Analytics Division, and data-sharing agreements prohibit making the data set publicly available.

Disclaimer: Nathan Stall is an associate editor with CMAJ and was not involved in the editorial decision-making for this article.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Available: www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/long-term-care.html (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown KA, Jones A, Daneman N, et al. Association between nursing home crowding and COVID-19 infection and mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181:229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu AT, Lane N. Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes — ongoing challenges and policy response. London (UK): International Long Term Care Policy Network; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Katz PR, et al. The need to include assisted living in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21 572–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poss JW, Sinn C-LJ, Grinchenko G, et al. Location, location, location: characteristics and services of long-stay home care recipients in retirement homes compared to others in private homes and long-term care homes. Healthc Policy 2017;12:80–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ducharme J. America’s assisted living residents are “falling through the cracks” of COVID-19 response. Time 2020. May 28. Available: https://time.com/5843260/assisted-living-facilities-covid-19/ (accessed 2020 Nov. 24).

- 7.Facts & figures — assisted living. Washington (D.C.): American Health Care Association; 2020. Available: https://www.ahcancal.org/Assisted-Living/Facts-and-Figures/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roblin B, Deber R, Kuluski K, et al. Ontario’s retirement homes and long-term care homes: a comparison of care services and funding regimes. Can J Aging 2019;38:155–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.True S, Ochieng N, Chidambaram P. Overlooked and undercounted: the growing impact of COVID-19 on assisted living facilities. KFF.org 2020. Sept. 1. Available: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/overlooked-and-undercounted-the-growing-impact-of-covid-19-on-assisted-living-facilities/ (accessed 2020 Nov. 9).

- 10.Annual report 2019/2020. Toronto: Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority; 2020:47. Available: www.rhra.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/20192020-RHRA-Annual-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVID-19 Dashboard. Toronto: Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority; 2020. Available: https://www.rhra.ca/en/covid19dashboard/ (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi SH, See I, Kent AG, et al. Characterization of COVID-19 in assisted living facilities — 39 states, October 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1730–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roxby AC, Greninger AL, Hatfield KM, et al. Outbreak Investigation of COVID-19 Among Residents and Staff of an Independent and Assisted Living Community for Older Adults in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Intern Med 2020. May 21: e202233. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2233 (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stall NM, Jones A, Brown KA, et al. For-profit long-term care homes and the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and resident deaths. CMAJ 2020;192:E946–E55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ontario releases updated COVID-19 modelling for second wave. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2020. Available: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/58602/ontario-releases-updated-covid-19-modelling-for-second-wave (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 2007;18:800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Retirement Homes Act, 2010, S.O. 2010, c. 11Jun 8, 2010. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/10r11#BK13 (accessed 2020 Nov. 27).

- 19.Understanding the Act. Toronto: Retirement Homes Regulatory Authority; 2020. Available: www.rhra.ca/en/about-rhra/our-role/understanding-the-act/ (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 20.iPHIS resources. Toronto: Public Health Ontario; 2020. Available: www.publichealthontario.ca/Diseasesand Conditions/Infectious Diseases/CCM/iPHIS (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Confirmed positive cases of COVID19 in Ontario. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2020. Available: https://data.ontario.ca/dataset/f4112442-bdc8-45d2-be3c-12efae72fb27/resource/455fd63b-603d-4608-8216-7d8647f43350/download/conposcovidloc.csv (accessed 2020 Sept. 30). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matheson FI, Dunn JR, Smith KLW, et al. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: a new tool for the study of inequality. Can J Public Health 2012;103(Suppl 2):S12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg). Toronto: Public Health Ontario; 2020. Available: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/Dataand Analysis/Health Equity/OntarioMarginalizationIndex (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postal Code OM Conversion File Plus (PCCF+).Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. Cat no82F0086X. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/82F0086X (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capacity Panning and Analytics Division. Toronto: Ontario’s Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission; 2020:23. Available: http://ltccommission-commissionsld.ca/cm/pdf/LTCC_Capacity_Planning_and_Analytics_Overview.pdf (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisman DN, Bogoch I, Lapointe-Shaw L, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among residents with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in long-term care facilities in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2015957. Available: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7376390/ (accessed 2020 Nov. 24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2005–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malikov K, Huang Q, Shi S, et al. Temporal associations between community incidence of COVID-19 and nursing home outbreaks in Ontario, Canada. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:260–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chow EJ, Schwartz NG, Tobolowsky FA, et al. Symptom screening at illness onset of health care personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection in King County, Washington. JAMA 2020;323:2087–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Houtven CH, DePasquale N, Coe NB. Essential long-term care workers commonly hold second jobs and double- or triple-duty caregiving roles. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:1657–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones A, Watts AG, Khan SU, et al. Impact of a public policy restricting staff mobility between nursing homes in Ontario, Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:494–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enhanced epidemiological summary: COVID-19 in Ontario — a focus on diversity. Toronto: Public Health Ontario; 2020. Available: www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/epi/2020/06/covid-19-epi-diversity.pdf?la=en (accessed 2020 Nov. 9). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Cen X, Cai X, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and deaths across U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:2454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]