Abstract

Insulin replacement therapy for diabetes mellitus seeks to minimise excursions in blood glucose concentration above or below the therapeutic range (hyper- or hypoglycaemia). To mitigate acute and chronic risks of such excursions, glucose-responsive insulin-delivery technologies have long been sought for clinical application in type 1 and long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Such ‘smart’ systems or insulin analogues seek to provide hormonal activity proportional to blood glucose levels without external monitoring. This review highlights three broad strategies to co-optimise mean glycaemic control and time in range: (1) coupling of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) to delivery devices (algorithm-based ‘closed-loop’ systems); (2) glucose-responsive polymer encapsulation of insulin; and (3) mechanism-based hormone modifications. Innovations span control algorithms for CGM-based insulin-delivery systems, glucose-responsive polymer matrices, bio-inspired design based on insulin’s conformational switch mechanism upon insulin receptor engagement, and glucose-responsive modifications of new insulin analogues. In each case, innovations in insulin chemistry and formulation may enhance clinical outcomes. Prospects are discussed for intrinsic glucose-responsive insulin analogues containing a reversible switch (regulating bioavailability or conformation) that can be activated by glucose at high concentrations.

Keywords: Artificial pancreas, Glucose-responsive insulin, Glucose-responsive polymers, Glucose sensor, Hormone-receptor recognition, Review

Introduction

Insulin replacement therapy (IRT) is essential for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus and often required by patients with late-stage type 2 diabetes. Advances in diabetes technologies have been broadly motivated by the aim to link optimisation of IRT (including individualised glycaemic goals in type 2 diabetes [1, 2]) and healthcare outcomes [3–8]. During a typical 24 h period, patients on insulin therapy often exhibit episodes of hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia [9], despite individualised dosing regimens [10, 11] and the broad use of engineered basal and rapid-acting insulin analogues [12–14]. Indeed, glycaemic excursions outside the narrow blood glucose range classified as normoglycaemia (4.4–6.7 mmol/l) [15] are frequent despite strict adherence to dietary and lifestyle recommendations [16, 17]. These challenges have motivated innovation in ancillary technologies: formulation chemistry, protein engineering, glucose-sensing technologies and delivery devices [18, 19]. Integrating IRT with engineered mechanisms of feedback (whether at the level of protein, cell or device) represents a critical current frontier of innovation, with the overarching goal of fewer hyperglycaemic excursions and reduced time in hypoglycaemia (i.e. increased time in range [TIR]). TIR is a major issue, ever-present in the daily life of an individual with type 1 diabetes [20, 21] and in a subset of those with type 2 diabetes [22].

In this review we outline a range of glucose-responsive (‘smart’) approaches to control TIR and discuss the prospects for mechanism-based molecular design of intrinsic glucose-responsive insulin (GRI) analogues [23]. Such delivery systems or insulin analogues seek to optimise TIR by the combined approaches of molecular design of new chemical entities and increased engineering controls to deliver insulin therapeutics. Like endogenous beta cells, such systems (broadly designated GRIs) would provide insulin activity proportionate to the metabolic state. Accordingly, the GRI concept has attracted the attention of the research community [24–27] and funders [28, 29] alike.

GRIs may be broadly classified as: (1) algorithm-based mechanical GRI systems (closed-loop delivery systems as an ‘artificial pancreas’) based on continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)-coupled insulin pumps [30]; (2) polymer-based systems, wherein insulin is encapsulated within a glucose-responsive polymeric matrix-based vesicle or hydrogel [31]; or (3) molecular GRI analogue systems, which involve the introduction of a glucose-sensitive motif to the insulin molecule or its formulation that, in either case, confers glucose-responsive changes to bioavailability or hormonal activity [32] (Fig. 1). We highlight potential synergies among these technologies as molecular GRIs may, in principle, be delivered via a closed-loop system (for further review, please see a related article in this special series by Boughton and Hovorka [33]). Cell-based therapies, which provide biological feedback regulation [34, 35], are beyond the scope of this review.

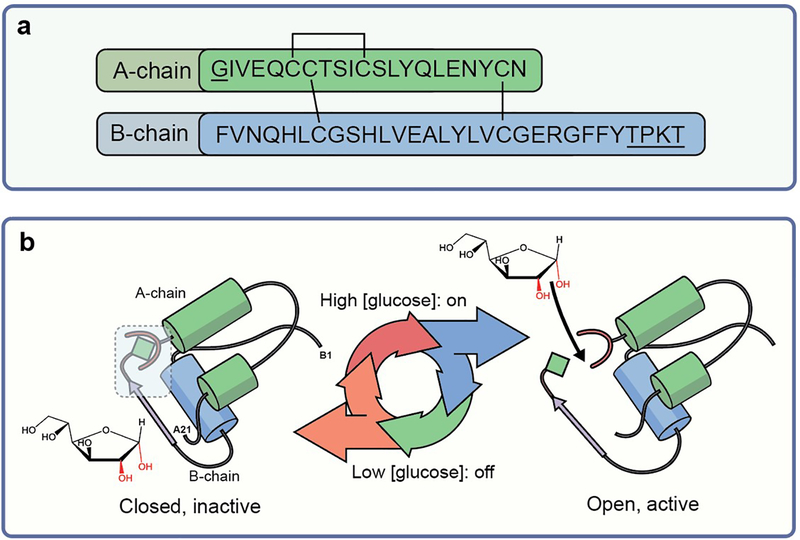

Fig. 1.

(a) Design strategy for intrinsic molecular GRIs. Sequence of insulin showing A-chain and B-chain with typical sites of chemical modification underlined (GlyA1 N-terminal and B-chain residues B27–B30) that affect pharmacokinetics and monosaccharide responsivity. Amino acid residues are labelled using their standard single letter codes. (b) Design scheme of monosaccharide-responsive insulin. The ribbon model of closed inactive insulin (T-state monomer) is shown (with a free glucose molecule adjacent to it); the blue box highlights sites of modification (red horseshoe shapes indicate glucose-binding element; green diamonds indicate internal diol). The envisioned glucose-regulated conformational cycle in which a monosaccharide acts as a competitive ligand to regulate a conformational switch between the closed state (inactive in absence of ligand) and the open state (active in presence of ligand) is illustrated.

Mechanical systems

Closed-loop systems

Mechanical GRI systems [36] integrate: (1) CGM to provide real-time measurement of interstitial glucose concentration; (2) an insulin pump receiving CGM input; and (3) a control algorithm specifying the appropriate dose of insulin for minute-by-minute s.c. injection [11, 37, 38]. Although these systems promise to improve 24 h glycaemic control in diverse patient populations (including adults, adolescents and children), CGM-based measurements of interstitial glucose concentrations lag by ~20 min behind changes in blood glucose levels, complicating prediction of future glycaemic trends. Reliable prediction is important because a ‘rapid-acting’ insulin analogue (once injected) may require 20–40 min for absorption and, once in the blood stream, may exert biological effects lasting 3–4 h [39]. The robustness of current predictive algorithms is likely to be enhanced by development of ‘ultra-fast’ pump insulin analogue formulations [40], such as Fiasp (Novo Nordisk) [41, 42], ultra-rapid lispro (URLi; known as Lyumjev in Europe; Eli Lilly) [43, 44], and respective reformulations of prandial analogues insulin, including insulin aspart (ProB28→Asp) and insulin lispro (ProB28→Lys and LysB29→Pro) [45–47]. The progress of CGM along with automated real-time insulin titration and bolus calculators, has enabled initial regulatory approval of mechanical GRI systems [11].

Dual-hormone pumps

To prevent or treat hypoglycaemia more effectively, bihormonal pumps have been developed to provide either insulin or its counter-regulatory hormone glucagon [48–53]. Dual-hormone algorithms trigger s.c. injections of a stabilised glucagon formulation based on trends in CGM readings predicting an impending hypoglycaemic excursion, thereby maintaining blood-glucose levels within range more efficiently than conventional CGM-coupled insulin pumps [54, 55]; the extent of advantage and its clinical impact have been the subject of debate. Fibrillation-resistant formulations of glucagon or glucagon analogues would be required for practical bihormonal systems [56].

Insulin stability in closed-loop systems

Ultra-miniaturisation of sensors and improved accuracy of pumps [36, 57–58] have encouraged reconsideration of i.p. delivery of insulin via i.p. infusion devices [59, 60]. Implanted refillable pumps [61] have promised ultra-rapid pharmacokinetic dosing profiles of insulin with first-pass hepatic signalling in the portal circulation. These advantageous features have stimulated interest in novel i.p-compatible insulin analogue formulations; desiderata include insulins with even more rapid onset of activity, shorter duration and greater formulation stability compared with the insulin therapeutics currently on the market.

Despite the above theoretical advantages and the convenience of long-term i.p. reservoirs of insulin (up to 3 months), catheter occlusion [62] remains a concern that has limited the feasibility of such systems in otherwise encouraging clinical trials [63]. Occlusions are often mediated by immunogenic and proinflammatory insulin-derived amyloid fibrils [64, 65]. Insulin instability and fibrillation can also occur within the pump reservoir to inactivate the hormone and provide seeds for further cycles of fibrillation.

Risk of insulin degradation in i.p. systems might be mitigated through design and development of ultra-stable, fibrillation-resistant analogues. Examples are provided by single-chain insulins (SCIs) containing a foreshortened C domain [66] and by two-chain insulin analogues containing an engineered non-canonical disulfide bridge between A- and B-chains [67–69] (Fig. 2). The altered topology (connectivity) of such analogues appears incompatible with cross-β assembly, the canonical core structure of an amyloid [70–72]. Their topologies may, in principle, alter the signalling properties of the hormone. Insertion of non-canonical cystine B4–A10 (Fig. 2b), for example, is associated with anomalously prolonged duration of activity of insulin upon intravenous bolus injection in rat studies [67], an unfavourable property of a pump insulin, the safety of which relies on fast-on/fast-off pharmacodynamics. Clinical data are not available.

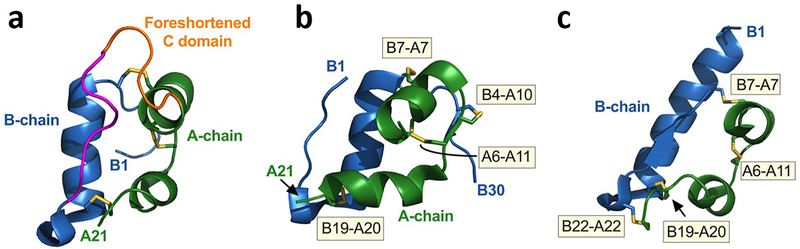

Fig. 2.

Ultra-stable insulin analogues. (a) Single-chain insulin (SCI) analogues exhibit native-like A and B domains (green and blue, respectively) with three native disulfide bridges (yellow). A foreshortened C-domain (5–8 residues; orange) connects the C-terminal B-chain β-strand (magenta) to the A-chain N-terminus. A favourable C-domain sequence can dampen conformational flexibility, augment thermodynamic stability and protect from fibrillation [66]. Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 2LWZ (www.rcsb.org/; accessed: 1 February 2021). Figure adapted from [145] with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. (b, c) Ultra-stable two-chain insulin analogues with engineered fourth disulfide bridges. Crystal structure of the four-disulfide (4SS)-insulin analogues containing a disulfide bond in (b) position A10-B4 (PDB ID: 4EFX) [67] and (c) position A22-B22 (PDB ID: 6TYH) [69]. The disulfide bonds (shown in yellow) and labelled (yellow boxes). Images were created with PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/; accessed: 1 February 2021).

Polymer-based GRI systems

Polymer-based technologies exploit sequestration of native or derivatised insulin within a matrix suitable for s.c. injection by directly integrating glucose-responsive components into delivery systems [73, 74]. The matrix, in principle, senses the glucose concentration and releases a proportional amount of insulin. Three classes of glucose-sensitive motifs have enabled such feedback: (1) glucose-binding proteins, a class that includes lectins, like concanavalin A (ConA); (2) glucose oxidase, an enzyme that catalyses oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid with release of a proton (hence lowering the pH); and (3) boronate-based chemistries, exemplified by phenylboronic acid (PBA; see below), which form reversible ester linkages with diol-containing molecules [75], including glucose [76]. In addition to these categories, an innovative recent technology envisions endogenous biological systems (e.g., the mannose receptor and even components of the erythrocyte) as a ‘smart’ matrix-based insulin deliver system [77, 78].

Insulin–lectin complexes

More than 40 years ago, Brownlee and Cerami pioneered a model GRI system: glycosylated insulin complexed with ConA [24, 79]. This complex was designed to sequester insulin in the s.c. space during normoglycaemia and release the hormone during hyperglycaemia via competition with ambient glucose molecules (Fig. 3a). Although the strategy was successful in vitro, its competitive set point was above the range of typical hyperglycaemic concentrations [79]. ConA’s immunogenicity and mitogenicity might limit clinical translation [80, 81].

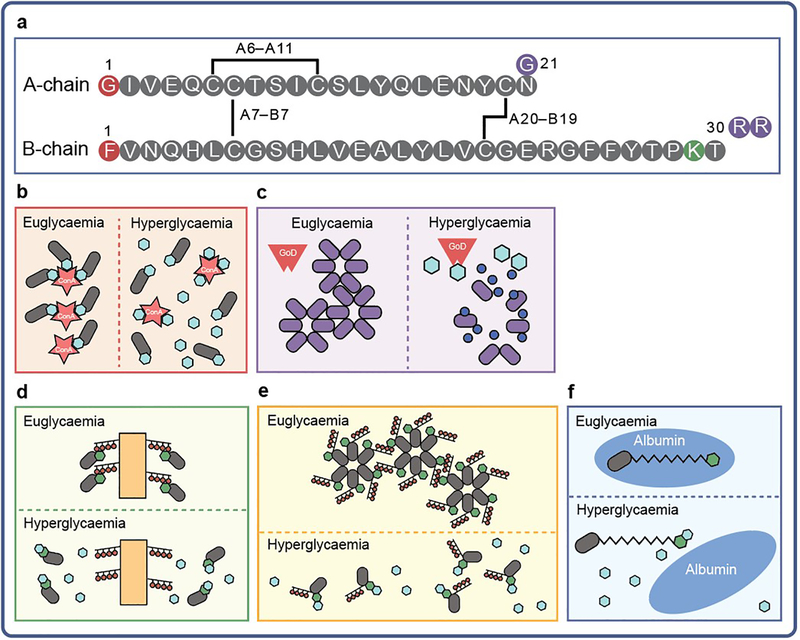

Fig. 3.

GRI-inspired derivatisation of insulin. Insulin contains two peptide chains (designated ‘A’ and ‘B’) connected by two disulfide linkages (cystines A7–B7 and A20–B19). (a) Brownlee and Cerami [24, 79] created a molecular GRI by coupling saccharides to the N-termini of one or both polypeptide chains of insulin (shown as red circles in the A- and B-chain schematic). The analogues (grey ovals) were bound to ConA (red star) before administration in rats. ConA was expected to sequester the modified insulin in the s.c. space under euglycaemic conditions, but allow its liberation following competitive binding of ambient glucose (blue hexagons) during hyperglycaemia [24, 79]. (b) A GRI system employing insulin glargine (purple ovals; its three amino acid substitutions denoted as purple circles in the A- and B-chain schematic) was co-injected with glucose oxidase (GoD; red polygon), which was expected to lower local pH by oxidising glucose to gluconic acid (dark blue circles) at a rate proportional to the glycaemic state, thereby increasing the solubility and, hence, pH-dependent bioavailability of the analogue. (c–e) A number of groups have modified the ε-amino group of LysB29 of the insulin molecule with PBA derivatives (green hexagons) to create candidate GRI systems. (c) Hoeg-Jensen et al [32] directly coupled LysB29 with PBA derivatives, enabling binding to diol-containing polymer carriers (orange rectangles with red circles) in a glucose-dependent fashion [32]. (d) The same group also derivatised residue B29 with a molecule containing a PBA and a polyol group (black lines with red circles), leading to multi-hexameric complexes in vitro that could dissociate in a glucose-dependent fashion [110]. (e) Chou and colleagues [112] created a GRI that contained a PBA derivative coupled via a fatty-acyl linker (black jagged line) to LysB29. They hypothesised that this analogue would bind to albumin (blue oval) below a threshold level of blood glucose, being liberated during hyperglycaemia as glucose-modified PBA–insulin, which was envisioned to have decreased affinity for albumin; however, the GRI-responsive mechanism of lower affinity of the glucose-modified PBA–insulin for albumin was not confirmed [112]. Figure adapted from [145] with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Glucose-responsive polymers

Advances in materials science have enabled design of diverse candidate polymer-based GRI systems. These were based on initial observations of Lorand and Edwards [75] that boronic acids react reversibly with vicinal (1,2-) diols (like those that occur naturally in carbohydrates and catechol); their reaction yields boronate esters. Norrild and Eggert first provided NMR evidence that binding of PBA to d-glucose is primarily mediated by the α-d -glucofuranose conformer (Fig. 4) [76]. Subsequently, Wang’s group [82, 83] described a mechanism/mechanisms of binding between diols and boronic acids (reviewed by Joop A. Peters in relation to monosaccharides [84]). Such systems envisaged encapsulation of insulin within polymeric matrices to form a ‘smart’ s.c. depot. The set points of chemical equilibrium-based glucose-recognition technologies (relative to enzyme- or protein-based schemes) may be more amenable to optimisation than ConA systems were found to be.

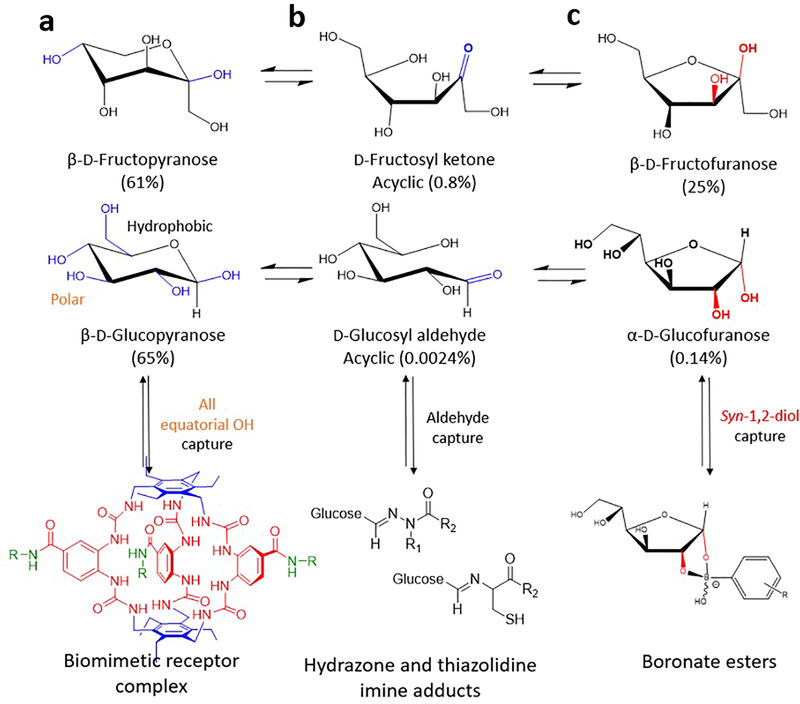

Fig. 4.

Biomimetic and chemical strategies to bind glucose vs fructose. Selective but reversible capture strategies exploit different molecular features and reactivity in conformational equilibria in water at pH 7.4 between saccharides, such as d-fructose and d-glucose conformations. d-Fructose populates β-d-fructopyranose, d-fructosyl ketone and β-d-fructofuranose (per cent population: 61%, 0.8% and 25%, respectively) and d-glucose populates β-d-glucopyranose, d-glucosyl aldehyde and α-d-glucofuranose (per cent population: 65%, 0.0024% and 0.14%, respectively) (data from [75]). (a) The biomimetic approach has achieved selective binding of β-d-glucopyranose over β-d-fructopyranose (dissociation constant [Ka] ~18,000 M−1 and Ka ~51 M−1, respectively). This is owing to the all equatorial polar hydroxy groups in β-d-glucopyranose (shown in blue) that form specific hydrogen bonds with the preorganised urea-based cage elements and the dual phenyl groups in the biomimetic receptor complex (shown in red and blue, respectively), which make apolar hydrophobic contacts with the glucopyranose ring with solubilising groups (shown in green) [146]. Neither d-fructose nor other saccharides accommodate these requirements for interaction with the biomimetic receptor complex [125]. (b) Jensen and colleagues [114] demonstrated a novel chemical approach to d-glucose selectivity by exploiting its open chain, acyclic d-glucosyl aldehyde. A series of masked cleavable hydrazones or thiazolidines were tuned for aldehyde reactivity (carbonyl groups shown in blue). These GRI designs relied on hydrolysis of a hydrazone or thiazolidine linker that was covalently attached to insulin at one end and C18 fatty acid at the other. On hydrolysis, d-glucosyl aldehyde reacts with the free unmasked linker-moiety, resulting in a shift of equilibrium towards a free active insulin analogue. Increasing concentrations of glucose (from normoglycaemia to hyperglycaemia) are proposed to drive this shift. In contrast, d-fructose’s acyclic form (d-fructosyl ketone [shown in blue]) is reactive to the unmasked linkers but not generally found in the body [114]. (c) PBAs bind most strongly to aligned 1,2-diol elements, such as those found in β-d-fructofuranose; respective conformational equilibria, thus, favour selective binding to fructose [84]. The acidity of PBAs is also known to affect diol reactivity, with vicinal diols known to produce boronate esters [75, 83], as illustrated by the α-d-glucofuranose/boronate ester in the figure. Key cis-hydroxyl groups are coloured red. d-Fructopyranose, β-d-fructofuranose, β-d-glucopyranose and α-d-glucofuranose images adapted from [108], published by The Royal Society of Chemistry under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Biomimetic receptor complex image adapted from [146] by permission from Springer Nature, ©2018.

Polymer-based GRIs can, in principle, employ a variety of encapsulation chemistries, including polyethylene glycol (PEF), poly(N-vinyl-pyrrolidone) and succinyl-amidophenyl-glucopyranoside [31, 74, 85]. Whereas the matrices are impermeable to insulin during normoglycaemic or hypoglycaemic conditions, their permeability may increase as a result of physical changes that cause swelling or increased water solubility of the polymer in response to an increase in interstitial glucose concentration. Examples include matrices co-derivatised with PBA, other boronic acids [86–88] and dot-immobilised glucose ester-based crosslinks [74, 85, 89].

Immobilised glucose-binding proteins and enzymes may also be integrated with glucose-modified polymers [77, 90]. Of particular interest, glucose oxidase has been encapsulated in matrices that are chemically sensitive to H2O2, hypoxia or decreases in local pH. Unlike PBA and non-enzymatic glucose-binding-protein-based technologies, polymeric matrices in glucose oxidase-based systems exploit its catalytic activity to increase the polymer’s water permeability and, so, regulate hormone release [91, 92] (for review, see Wang et al [73]).

Polymer-based GRI technologies are challenged by limited particle stability [93, 94], lag times and suboptimal insulin-response rates leading to hyperglycaemic or hypoglycaemic excursions. Addressing these limitations has encountered a catch-22: sensitising matrices to hyperglycaemia, for example, can limit their ability to attenuate insulin release at low glucose concentrations. The latter problem can be exacerbated by matrix degradation, in principle raising the risk of severe hypoglycaemic episodes in patients due to bolus over-delivery [95, 96].

Intrinsic GRI systems

Intrinsic (or unimolecular) GRIs define a novel class of analogues wherein the modified hormone itself confers glucose-dependent activity or bioavailability. Initial candidate technologies relied on sequestration of active insulin hormone within the s.c. space or within the bloodstream (as inactive complexes) with enhanced release or activation only during hyperglycaemia. Recent bio-inspired advances exploit specific endogenous features of the s.c. space, potential hormone-carrier proteins or cellular clearance systems. Although these elegant strategies remain in the early stages of development, their simplicity, convenience and potential cost-effectiveness make them an attractive target of ongoing research. Because standard insulin products are becoming a commodity in the pharmaceutical industry, clinical introduction of chemically modified insulins that are glucose responsive will likely require detailed analysis of cost effectiveness despite their elegance.

Insulin fusion proteins

A pioneering approach employed an insulin–glucose oxidase fusion molecule [97]. A cysteine-based linkage was broken as the enzyme oxidised glucose. Although proof of principle was obtained in vitro, the low Km of the enzyme for glucose led to liberation of the hormone under hypoglycaemic, as well as hyperglycaemic conditions [97]. In addition, release of H2O2 by glucose oxidase (as a byproduct of glucose oxidation) and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) could cause tissue injury. In a complementary approach, glucose oxidase-dependent changes in s.c. pH were exploited to modulate the solubility (and, hence, rate of absorption) of insulin glargine, the isoelectric point-shifted active component of Lantus (Sanofi) [98]. Because this basal analogue is insoluble at neutral pH but soluble under acidic conditions, glucose oxidase-mediated acidification (via production of gluconic acid), in principle, enhances bioavailability [99] (Fig. 3b). Although in vitro and pilot animal studies appear promising, clinical data has not yet been obtained [100].

Biology-inspired GRI systems

An attractive frontier of GRI engineering takes advantage of an endogenous biological system, ‘hijacked’ in its native form to provide an active component of a glucose-dependent regulatory scheme. Such an approach was developed by Merck, based on competitive clearance of a saccharide-modified insulin by the endogenous mannose receptor [101, 102]. The saccharide adduct presented terminal mannose moieties and so provided a substrate for clearance by the ubiquitous mannose receptor system. The essential idea envisioned rapid clearance of the modified insulin under conditions of hypoglycaemia but slow clearance under conditions of hyperglycaemia due to low-affinity binding of glucose to (and, hence, competition at) the mannose receptor. The glucose-dependent differences in rates of clearance, although not large, were sufficient to provide partial protection from hypoglycaemia relative to the same dose of an unmodified insulin. Although animal-based and pilot clinical studies were pursued, this approach is no longer under development. These challenges to create a modified insulin with an improved therapeutic index that enables tighter glycaemic control with a reduced risk for hypoglycaemia, as well as the challenges of translating in vivo animal models and data for application in humans, highlight the importance of developing better in silico GRI modelling in the developmental pipeline [23, 103–105].

PBA-modified insulin derivatives

PBA is a diol-binding element that is able to sense carbohydrates [106–108]. A PBA-modified insulin derivative was first described as a potential intrinsic GRI by Hoeg-Jensen et al [32]. This work established that PBA could be coupled to the insulin B29 position without affecting its biological activity, in turn enabling the analogue to bind diol-containing sequestering agents (Fig.3). The investigators further demonstrated that a modified insulin carrying both a PBA and a polyol group attached to the LysB29 sidechain could form high molecular weight multimeric complexes that dissociate under control by d-sorbitol or d-glucose. (Fig. 3d) [109, 110], A sidechain glutamic acid linker was required for in vitro activity, as is the case for insulin degludec, a second-generation basal acylated insulin [111]. To our knowledge, no in vivo results have been described.

Novel use of a PBA-based GRI was described by Chou and colleagues [112] who employed an acylated insulin analogue (insulin detemir) in which myristic acid was coupled onto lysine (LysB29) to mediate binding to serum albumin and, so, provide a long-lived circulating depot of insulin. The hydrocarbon acyl tag was further derivatised with PBA so that its affinity for albumin might be glucose-responsive. The essential idea thus envisioned albumin as a glucose-dependent carrier, similar, in spirit, to the reported use of erythrocyte membranes as glucose-dependent carriers [77, 113]. Although this goal was not achieved in vitro with this analogue (i.e. the albumin-binding properties of the analogues were not glucose-dependent), several such candidate GRI analogues exhibited glucose-responsive biological activity in a peritoneal glucose-infusion assay in mice [73].

In a similar manner to the above, Jensen and colleagues [114] took advantage of albumin binding as a plasma depot to demonstrate novel GRI activity acceleration, which was mediated by aldehyde-responsive capture of released insulin. The strategy biased for glucose reactivity over fructose by virtue of aldehyde capture based on the increased reactivity of acyclic glucosyl aldehyde over fructosyl ketone and the fact that fasting glucose concentrations are about >1000-fold greater than those of fructose (Fig. 4) [114]. In the same study [114], in glucose clamp models, some insulin analogues demonstrated GRI activity, but their in vitro hydrolysis rates were >6 h, suggesting that lag time might be an issue.

Glucose-regulated conformational switches

A reversible conformational cycle between active and inactive states of insulin may, in principle, be regulated by a ligand, such as glucose (Fig. 1b). A new avenue for molecular GRI design was inspired by crystallographic and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies of insulin bound to fragments of the insulin receptor [115, 116], including the intact ectodomain [117, 118]. Such studies revealed a major change in the conformation of insulin on receptor binding in which the hormone ‘opens’ with detachment of the C-terminal B-chain segment; this enables intimate contact between the N-terminal A-chain α-helix and the receptor complex [117, 118].

It may be possible to exploit the mechanism of insulin–insulin receptor binding and signalling to design a glucose-dependent conformational switch, such that binding of the modified insulin to the insulin receptor is impaired under hypoglycaemic conditions. A glucose-displaceable bridge between a glucose-binding element attached to one position in the insulin molecule and an internal ligand (such as a diol or saccharide) may, in principle, be placed at any pair of sites, such that the ‘closed state’ is inactive and the ‘open state’ is active. Proof of principle was recently provided in studies of a fructose-responsive insulin (FRI), in which meta-fluoro-PBA was attached to the A-chain N-terminus, and an aromatic diol group was attached to the ε-amino group of LysB28 to provide an internal tether between the A- and B-chains (see ‘open, active’ form in Fig. 1b) [119]. Whilst the baseline activity of this analogue was low, near-native activity (as assessed in studies of the liver-derived cell line HepG2) was restored by 50 mmol/l fructose, but not by 50 mmol/l glucose [119].

The binding preference of PBA and its derivatives for fructose (relative to glucose) reflects their respective conformational equilibria and, in particular, the subpopulation of conformers displaying cis-1,2-diols that have hydroxyl groups that are oriented syn-periplanar (same side) for joint presentation to the boronic acid (Fig. 4c) [108]. Such alignment depends on the conformational equilibrium of a monosaccharide, as is observed in the β-d-fructofuranose form (Fig. 4c). Because the analogous conformation of glucose (α-d-glucofuranose; Fig. 4c) is >100-fold less populated compared with β-d-fructofuranose at equilibrium in solution [84, 120], binding of PBAs to fructose is significantly favoured. Improved glucose-binding elements will be required to extend the FRI proof-of-principle results to obtain bona fide GRIs. A chemical diversity of candidate boronate-based glucose sensors has been described [73, 82, 121–124], as well as non-boronate-based chemistries [125–127]. In addition, the above FRI’s bridge between the A-chain N-terminus and B-chain C-terminus follows naturally from the hormone’s mechanism of insulin receptor binding [116], but a wide variety of bridges might exhibit analogous glucose-responsive properties. Such design options promise an opportunity to co-optimise other GRI molecular features, including stability and immunogenicity.

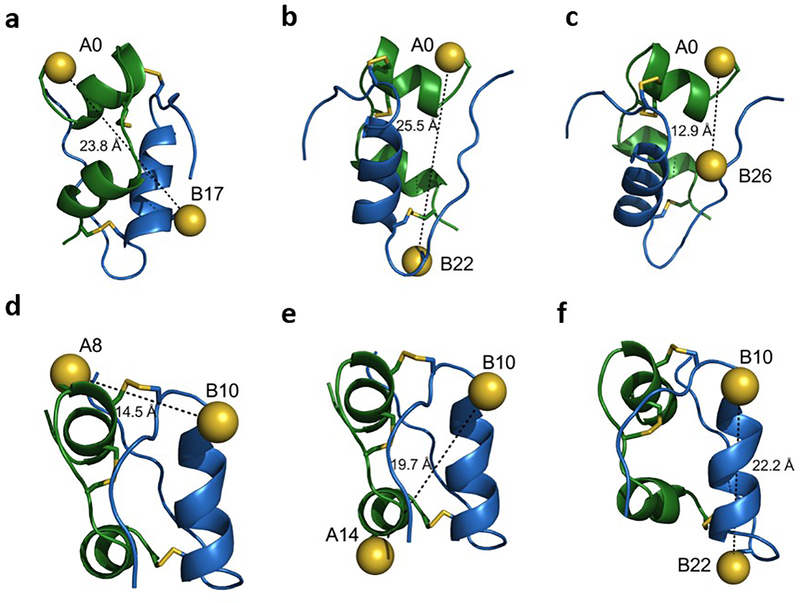

To define potential non-canonical pairs of conformational switch sites suitable for GRI design, DiMarchi and colleagues [128] undertook a systematic survey of fourth disulfide bridges in an insulin analogue (des-[B29,B30]-LysB28-insulin; ‘DesDi’ [129]). Whereas previous efforts to engineer additional disulfide bridges into insulin were motivated by stability [67–69], this study’s emphasis was on differences in insulin receptor binding on closure of the fourth bridge. Six such pairs of putative switch sites were identified based on this functional criterion (Fig. 5). These pairs are distant in the native structure of insulin; formation of the engineered disulfide bridge (forced by selective chemical tactics) presumably distorts the conformation of the hormone, including its insulin receptor-binding surface. Predicted distances between the unpaired cysteines in the framework of native insulin (T state) are given in the Fig. 5 and reported as interatomic distances.

Fig. 5.

Search for non-canonical disulfide-based conformational switch sites as designed by Brunel et al [128]. Location of fourth disulfide bonds and their predicted interatomic distances (indicated by dashed lines between sulphur atoms [yellow spheres]; predicted interatomic distances shown in angstroms [Å]) in the insulin monomer (crystallographic T state; Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 4INS [www.rcsb.org/; accessed: 1 February 2021]). The disulfide pairs in (a–f) were chosen based on their reported insulin receptor binding activity, the open:closed ratio of which was >100; they were associated with >100-fold decrease in activity on fourth disulfide-bond formation. The pairs are: (a) A0–B17; (b) A0–B22; (c) A0–B26; (d) A8–B10; (e) A14–B10; and (f) B10–B22. Sulphur atoms are shown in the substituted cysteines. Native disulfide bonds are shown as yellow lines; A-chain shown in green and B-chain in blue. Data were taken from [128]; images were created with PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/; accessed: 1 February 2021).

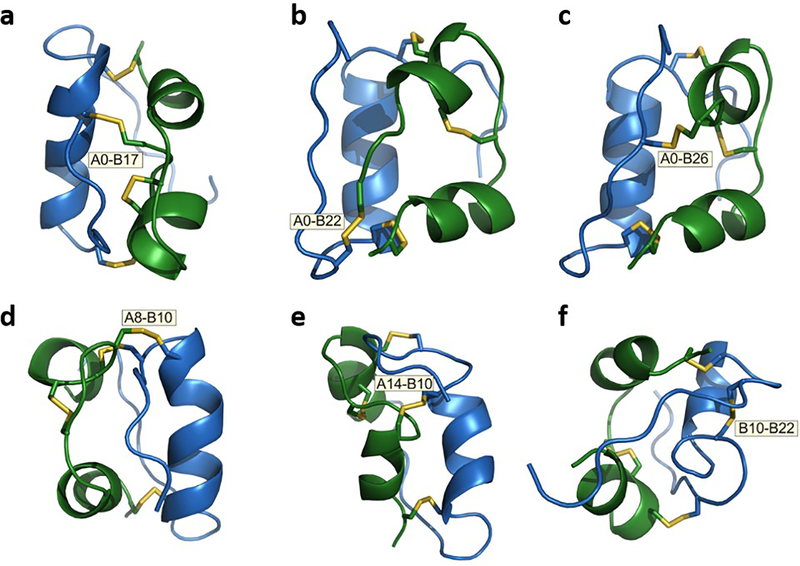

To visualise these novel analogues on closure of the non-native disulfide bridge, we undertook molecular modelling of the six constrained insulin analogues based on distance-geometry and restrained molecular dynamics. A baseline set of restraints was provided by prior NMR analysis of engineered insulin monomers [130, 131]. Of such fourth disulfide bridges, only cystine A0–B26 (Fig. 6c) could be accommodated within a native-like protein conformation (Fig. 7). A glucose-displaceable tether between amino acid residues A0 and B26 would, thus, be analogous to the fructose-regulated switch described above (residues A0–B26) [119].

Fig. 6.

Structural distortions among putative disulfide switch analogues [128] predicted on closure of a fourth disulfide bridge involve (a) cystine A0–B17, (b) cystine A0–B22, (c) cystine A0–B26, (d) cystine A8–B10, (e) cystine A14–B10 and (f) cystine B10–B22. A0 represents N-terminal extension of the A-chain by cystine. Only the model in (c) contains native α-helical segments and a native-like tertiary structure; the other five models are remarkable for segmental unfolding of helical segments and distortion of helix–helix orientations. Models were calculated using Xplor-NIH (https://nmr.cit.nih.gov/xplor-nih/; accessed: 1 February 2021), based on distant restraints (~750 per model) derived from NMR analysis of an engineered insulin monomer (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 2JMN [www.rcsb.org/; accessed: 1 February 2021]; [147]). Specific subsets of native distance restraints were removed to enable the designated additional disulfide bridge to be formed; distance restraints were omitted involving residues in: B9–B22 (a,b); B25–B30 and A0–A3 (c); B9–B16 and A2–A9 (d); A11–A16 and B9–B16 (e); and B9–B22 (f). Representative models were visualised and analysed using PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/; accessed: 1 February 2021). A-chain shown in green and B-chain in blue.

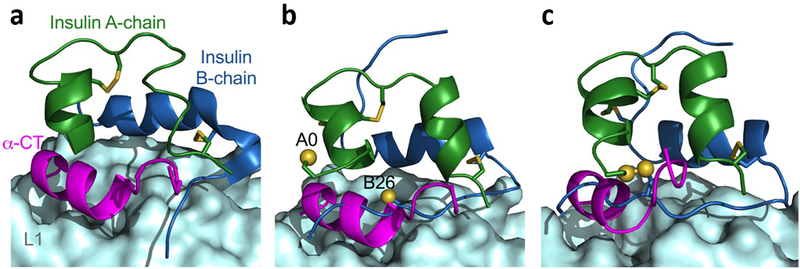

Fig. 7.

Mechanism of insulin–insulin receptor binding excludes certain engineered disulfide bridges. (a) Co-crystal structure of wild-type insulin bound to the micro-receptor (μIR) (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 4OGA [www.rcsb.org/; accessed: 1 February 2021]). Upon insulin binding to its receptor, the B-chain C-terminus moves away from A-chain, giving way to the α-CT domain. (b) A0–B26 three-disulfide (3SS) insulin monomer bound to the μIR. The location of sulphur atoms in the fourth cysteine pairs is shown. (c) Modelled structure of four-disulfide (4SS) insulin (A0–B26; see Fig. 6c) bound to the μIR. If the normal mode of binding takes place, the fourth A0–B26 disulfide bridge hinders the opening of the B-chain and causes a steric clash with the α-CT domain. Images were created with PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/; accessed: 1 February 2021). L1 domain shown as a pale cyan surface; α-chain of carboxyl terminal (α-CT) domain shown in magenta; insulin A-chain shown in green and B-chain in blue; sulphur atoms shown as yellow sphere.

In the other five cases, formation of the fourth disulfide seems to require partial unfolding of the protein, perturbing one or more α-helical elements (Fig. 6a,b,d–f); these distortions are incompatible with the structure of the primary insulin-binding site in the insulin receptor. For example, imposing cystines A8–B10 or A14–B10 in our modelling (Fig. 6d,e) distorted the central B-chain α-helix and N-terminal A-chain α-helix, key insulin receptor-binding elements [116]. Displacement of such aberrant bridges by glucose would presumably relieve the distortion and, so, restore activity. A rational path towards switchable intrinsic GRIs, based on strained disulfide engineering, was envisaged by DiMarchi and colleagues [128]. It would be of future interest to probe the structures and stabilities of these strained analogues, whether they contain cystine or reversible glucose-displaceable tethers. We anticipate that the set point for glucose displacement would be modulated by the degree of conformational strain.

Clinical significance and conclusions

The centennial of the discovery of insulin marks a time of continuing innovation in insulin technologies. Even as the events leading to insulin discovery in Toronto in 1921 are celebrated as a landmark in molecular medicine, a comprehensive history recognises not only the contributions of Frederick Banting, Charles Best, James B. Collip and John J. R. Macleod, but also the key insights and advances made by others in the preceding five decades, beginning with Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering (Germany) and continuing with Étienne Lancereaux (France), Nicolae C. Paulescu (Romania) and Israel Kleiner (USA) [132].

The present review highlights a vibrant frontier of insulin technologies. Whereas closed-loop systems have recently become a clinical reality [133–135], polymer-based and intrinsic GRIs promise to enhance the safety and efficacy of IRT. In addition to the elegance of the associated chemistries and macromolecular structures, ongoing research has a compelling clinical motivation: to enhance the health and quality of life of patients with type 1 diabetes and of patients with type 2 diabetes refractory to oral therapy—and with less burden on patients [136]. To bridge the valley between basic science and clinical applications, in silico simulations of animal physiology and human patients are likely to provide key guidance [23, 103–105].

All three classes of GRI technologies considered here, namely closed-loop delivery (as an ‘artificial pancreas’), polymer-based systems and molecular GRI analogue systems, seek to achieve optimal TIR. Standard IRT faces a trade-off: on the one hand, strict glycaemic control has been shown to retard or prevent microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes [6] and is likely to be beneficial in early stages of type 2 diabetes [137–139] but, on the other hand, aggressive glycaemic targets increase the acute and long-term risks of hypoglycaemia [10, 140–143]. Whereas CGM pump-based GRIs presently employ the most mature component technologies, recent innovations in matrix-based and unimolecular GRIs suggest promising routes towards safe and effective approximation of pancreatic beta cell function. We anticipate continuing progress in the coming years to reduce the burden of diabetes. Given the balance of price and access to new therapeutics (especially derivatised insulin analogues [144]) and the high human and economic costs of long-term diabetes complications, such innovative technologies are likely to be cost-effective when considering the integrated impact on society.

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Ismail-Beigi (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA), R. DiMarchi (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA), M. D. Michael (Thermalin, Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) and N. B. Phillips (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA) for helpful discussions.

Funding Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the JDRF, the Leon M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and NIH R01 grants DK040949 and DK127761 (to MAW).

Authors’ relationships and activities MAW is Chief Innovation Officer of Thermalin, Inc. (Waban, MA, USA) in which he has equity. All the other authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

References

- [1].Ismail-Beigi F (2011) Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial - clinical implications. Clin Chem 57: 261–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ismail-Beigi F (2012) Glycemic management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 366(14): 1319–1327. 10.1056/NEJMcp1013127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329(14): 977–986. 10.1056/nejm199309303291401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. (2005) Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 353(25): 2643–2653. 10.1056/NEJMoa052187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stolar M (2010) Glycemic control and complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 123(3): S3–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Nathan DM, Group DER (2014) The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care 37(1): 9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hayward RA, Reaven PD, Wiitala WL, et al. (2015) Follow-up of glycemic control and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 372(23): 2197–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bebu I, Braffett BH, Orchard TJ, Lorenzi GM, Lachin JM, DCCT/EDIC Research Group (2019) Mediation of the effect of glycemia on the risk of CVD outcomes in type 1 diabetes: the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care 42(7): 1284–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Campbell MD, Walker M, Bracken RM, et al. (2015) Insulin therapy and dietary adjustments to normalize glycemia and prevent nocturnal hypoglycemia after evening exercise in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 3(1): e000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, Hirsch IB, Inzucchi SE, Genuth S (2011) Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 154(8): 554–559. 10.1059/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nimri R, Battelino T, Laffel LM, et al. (2020) Insulin dose optimization using an automated artificial intelligence-based decision support system in youths with type 1 diabetes. Nature Med 26(9): 1380–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vajo Z, Fawcett J, Duckworth WC (2001) Recombinant DNA technology in the treatment of diabetes: insulin analogs. Endocr Rev 22: 706–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hartman I (2008) Insulin analogs: impact on treatment success, satisfaction, quality of life, and adherence. Clinical medicine & research 6(2): 54–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tibaldi JM (2014) Evolution of insulin: from human to analog. Am J Med 127(10 Suppl): S25–S38. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Petznick A (2011) Insulin management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician 84(2): 183–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dandona P (2017) Minimizing glycemic fluctuations in patients with type 2 diabetes: approaches and importance. Diabetes Techn Therap 19(9): 498–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chehregosha H, Khamseh ME, Malek M, Hosseinpanah F, Ismail-Beigi F (2019) A view beyond HbA1c: role of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Ther 10(3): 853–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Grant AK, Golden L (2019) Technological Advancements in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 19(12): 163. 10.1007/s11892-019-1278-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zimmerman C, Albanese-O’Neill A, Haller MJ (2019) Advances in Type 1 Diabetes Technology Over the Last Decade. Eur Endocrin 15(2): 70–76. 10.17925/ee.2019.15.2.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yu S, Fu AZ, Engel SS, Shankar RR, Radican L (2016) Association between hypoglycemia risk and hemoglobin A1C in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Med Res Opin 32(8): 1409–1416. 10.1080/03007995.2016.1176017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Martyn-Nemeth P, Quinn L, Penckofer S, Park C, Hofer V, Burke L (2017) Fear of hypoglycemia: Influence on glycemic variability and self-management behavior in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complic 31(4): 735–741. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lipska KJ, Warton EM, Huang ES, et al. (2013) HbA1c and risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes and Aging Study. Diabetes Care 36(11): 3535–3542. 10.2337/dc13-0610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bakh NA, Cortinas AB, Weiss MA, et al. (2017) Glucose-responsive insulin by molecular and physical design. Nature Chem 9(10): 937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brownlee M, Cerami A (1979) A glucose-controlled insulin-delivery system: semisynthetic insulin bound to lectin. Science 206(4423): 1190–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zaykov AN, Mayer JP, DiMarchi RD (2016) Pursuit of a perfect insulin. Nature Rev Drug Discov 15(6):425–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hoeg-Jensen T (2020) Glucose-sensitive insulin. Molecular Metabolism: 101107. 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Disotuar MM, Chen D, Lin N-P, Chou DH-C (2020) Glucose-Responsive Insulin Through Bioconjugation Approaches. J Diabetes Sci Techn 14(2): 198–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].NIDDK (2011) Advances and emerging opportunities in diabetes research: a Strategic Planning report of the Diabetes Mellitus Interagency Coordinating Committee. Available from: www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/advances-emerging-opportunities-diabetes-research-strategic-planning-report. Accessed: 31 January 2021

- [29].Insel RA, Deecher DC, Brewer J (2012) Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation: mission, strategy, and priorities. Diabetes 61(1): 30–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Halvorson M, Carpenter S, Kaiserman K, Kaufman FR (2007) A pilot trial in pediatrics with the sensor-augmented pump: combining real-time continuous glucose monitoring with the insulin pump. J Ped 150(1): 103–105. e101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ravaine V, Ancla C, Catargi B (2008) Chemically controlled closed-loop insulin delivery. J Control Release 132(1): 2–11. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hoeg-Jensen T, Ridderberg S, Havelund S, et al. (2005) Insulins with built-in glucose sensors for glucose responsive insulin release. J Pept Sci 11(6): 339–346. 10.1002/psc.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Boughton CK, Hovorka R (2021) New closed-loop insulin systems. Diabetologia. 10.1007/s00125-021-05391-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vegas AJ, Veiseh O, Gürtler M, et al. (2016) Long-term glycemic control using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell–derived beta cells in immune-competent mice. Nature medicine 22(3): 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chen Z, Hu Q, Gu Z (2018) Leveraging Engineering of Cells for Drug Delivery. Acc Chem Res 51(3): 668–677. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Thabit H, Hovorka R (2016) Coming of age: the artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 59(9): 1795–1805. 10.1007/s00125-016-4022-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Garg SK, Weinzimer SA, Tamborlane WV, et al. (2017) Glucose outcomes with the in-home use of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Techn Therap 19(3): 155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hanaire H, Franc S, Borot S, et al. (2020) Efficacy of the Diabeloop closed-loop system to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes exposed to gastronomic dinners or to sustained physical exercise. Diabetes, Obesity Metab 22(3): 324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Genuth SM (1972) Metabolic clearance of insulin in man. Diabetes 21(10): 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Breton M, Farret A, Bruttomesso D, et al. (2012) Fully integrated artificial pancreas in type 1 diabetes: modular closed-loop glucose control maintains near normoglycemia. Diabetes 61(9): 2230–2237. 10.2337/db11-1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cypryk K, Wyrębska-Niewęgłowska A (2018) New faster-acting insulin Fiasp®—do we need a new meal-time insulin? Clin Diabetology 7(6): 282–286 [Google Scholar]

- [42].Majdpour D, Yale J-F, Legault L, et al. (2020) 10-Novel Fully Automated Fiasp-Plus-Pramlintide Artificial Pancreas for Type 1 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. Can J Diabetes 44(7): S4–S5 [Google Scholar]

- [43].Linnebjerg H, Zhang Q, LaBell E, et al. (2020) Pharmacokinetics and Glucodynamics of Ultra Rapid Lispro (URLi) versus Humalog® (Lispro) in Younger Adults and Elderly Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Clinical Pharm 59(12):1589–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Blevins T, Zhang Q, Frias JP, Jinnouchi H, Chang AM (2020) Randomized double-blind clinical trial comparing Ultra rapid lispro with Lispro in a basal-bolus regimen in patients with type 2 diabetes: PRONTO-T2D. Diabetes Care 43(12): 2991–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lougheed WD, Zinman B, Strack TR, et al. (1997) Stability of insulin lispro in insulin infusion systems. Diabetes Care 20: 1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mudaliar SR, Lindberg FA, Joyce M, et al. (1999) Insulin Aspart (B28 Asp-Insulin): A Fast-Acting Analog of Human Insulin. Diabetes Care 22: 1501–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Becker RH, Frick AD, Burger F, Potgieter JH, Scholtz H (2005) Insulin glulisine, a new rapid-acting insulin analogue, displays a rapid time-action profile in obese non-diabetic subjects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 113: 435–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bakhtiani PA, Caputo N, Castle JR, et al. (2014) A novel, stable, aqueous glucagon formulation using ferulic acid as an excipient. J Diabetes Sci Techn 9(1): 17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jacobs PG, El Youssef J, Reddy R, et al. (2016) Randomized trial of a dual-hormone artificial pancreas with dosing adjustment during exercise compared with no adjustment and sensor-augmented pump therapy. Diabetes, Obesity Metab 18(11): 1110–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Haidar A, Legault L, Messier V, Mitre TM, Leroux C, Rabasa-Lhoret R (2015) Comparison of dual-hormone artificial pancreas, single-hormone artificial pancreas, and conventional insulin pump therapy for glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: an open-label randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endo 3(1): 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Haidar A, Legault L, Matteau-Pelletier L, et al. (2015) Outpatient overnight glucose control with dual-hormone artificial pancreas, single-hormone artificial pancreas, or conventional insulin pump therapy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endo 3(8): 595–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Haidar A (2019) Insulin-and-Glucagon Artificial Pancreas Versus Insulin-Alone Artificial Pancreas: A Short Review. Diabetes Spectrum 32(3): 215–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Castle JR, El Youssef J, Wilson LM, et al. (2018) Randomized outpatient trial of single-and dual-hormone closed-loop systems that adapt to exercise using wearable sensors. Diabetes Care 41(7): 1471–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Blauw H, Keith-Hynes P, Koops R, DeVries JH (2016) A review of safety and design requirements of the artificial pancreas. Ann Biomed Engin 44(11): 3158–3172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].El-Khatib FH, Balliro C, Hillard MA, et al. (2016) Home use of a bihormonal bionic pancreas versus insulin pump therapy in adults with type 1 diabetes: a multicentre randomised crossover trial. Lancet 389(10067):369–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jackson MA, Caputo N, Castle JR, David LL, Roberts CT, Ward WK (2012) Stable liquid glucagon formulations for rescue treatment and bi-hormonal closed-loop pancreas. Curr Diabetes Rep 12(6): 705–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ribet F, Stemme G, Roxhed N (2017) Ultra-miniaturization of a planar amperometric sensor targeting continuous intradermal glucose monitoring. Biosensors Bioelectr 90: 577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Graf A, McAuley SA, Sims C, et al. (2016) Moving Toward a Unified Platform for Insulin Delivery and Sensing of Inputs Relevant to an Artificial Pancreas. J Diabetes Sci Techn 1932296816682762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schade DS, Eaton RP, Friedman JE, Spencer WJ (1980) Normalization of plasma insulin profiles with intraperitoneal insulin in diabetic man. Diabetologia 19: 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schade DS, Eaton P (1980) The peritoneum—a potential insulin delivery route for a mechanical pancreas. Diabetes Care 3(2): 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Irsigler K, Kritz H, Hagmüller G, et al. (1981) Long-term continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion with an implanted remote-controlled insulin infusion device. Diabetes 30(12): 1072–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Renard E, Boutleau S, Jacques-Apostol D, et al. (1996) Insulin underdelivery from implanted pumps using peritoneal route. Determinant role of insulin pump compatibility. Diabetes Care 19: 812–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Saudek CD, Duckworth WC, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. (1996) Implantable insulin pump vs multiple-dose insulin for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. Department of Veterans Affairs Implantable Insulin Pump Study Group. JAMA 276: 1322–1327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bally L, Thabit H, Hovorka R (2017) Finding the right route for insulin delivery–an overview of implantable pump therapy. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 14(9):1103–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jeandidier N, Boivin S, Sapin R, et al. (1995) Immunogenicity of intraperitoneal insulin infusion using programmable implantable devices. Diabetologia 38: 577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hua QX, Nakagawa SH, Jia W, et al. (2008) Design of an active ultrastable single-chain insulin analog: synthesis, structure, and therapeutic implications. J Biol Chem 283: 14703–14716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Vinther TN, Norrman M, Ribel U, et al. (2013) Insulin analog with additional disulfide bond has increased stability and preserved activity. Protein Sci 22(3): 296–305. 10.1002/pro.2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu F, Mayer JP, Gelfanov VM, Liu F, DiMarchi RD (2017) Synthesis of four-disulfide insulin analogs via sequential disulfide bond formation. J Org Chem 82(7): 3506–3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Xiong X, Blakely A, Karra P, et al. (2020) Novel four-disulfide insulin analog with high aggregation stability and potency. Chemical science 11(1): 195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Tycko R (2011) Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibril structure. Annu Rev Phys Chem 62: 279–299. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tycko R, Ishii Y (2003) Constraints on supramolecular structure in amyloid fibrils from two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy with uniform isotopic labeling. J Am Chem Soc 125: 6606–6607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Dobson CM (2003) Protein folding and misfolding. Nature 426: 884–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wang J, Wang Z, Yu J, Kahkoska AR, Buse JB, Gu Z (2020) Glucose-Responsive Insulin and Delivery Systems: Innovation and Translation. Adv Mat 32(13): 1902004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Shen D, Yu H, Wang L, et al. (2020) Recent progress in design and preparation of glucose-responsive insulin delivery systems. J Contr Release 321: 236–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lorand JP, Edwards JO (1959) Polyol complexes and structure of the benzeneboronate ion. J Org Chem 24(6): 769–774 [Google Scholar]

- [76].Norrild JC, Eggert H (1995) Evidence for mono-and bisdentate boronate complexes of glucose in the furanose form. Application of 1JC-C coupling constants as a structural probe. J Am Chem Soc 117(5): 1479–1484 [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wang C, Ye Y, Sun W, et al. (2017) Red blood cells for glucose-responsive insulin delivery. Adv Mat 29(18): 1606617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Yang J, Wang F, Lu Y, et al. (2019) Recent advance of erythrocyte-mimicking nanovehicles: From bench to bedside. J Contr Release 314: 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Brownlee M, Cerami A (1983) Glycosylated insulin complexed to Concanavalin A. Biochemical basis for a closed-loop insulin delivery system. Diabetes 32(6): 499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ballerstadt R, Evans C, McNichols R, Gowda A (2006) Concanavalin A for in vivo glucose sensing: a biotoxicity review. Biosens Bioelectron 22(2): 275–284. 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Coutinho A, Larsson EL, Grönvik KO, Andersson J (1979) Studies on T lymphocyte activation II. The target cells for concanavalin A-induced growth factors. Eur J Immun 9(8): 587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Karnati VV, Gao X, Gao S, et al. (2002) A glucose-selective fluorescence sensor based on boronicacid-diol recognition. Bioorg Medicinal Chem Lett 12(23): 3373–3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Fang H, Kaur G, Wang B (2004) Progress in boronic acid-based fluorescent glucose sensors. J Fluoresc 14(5): 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Peters JA (2014) Interactions between boric acid derivatives and saccharides in aqueous media: Structures and stabilities of resulting esters. Coord Chem Rev 268: 1–22 [Google Scholar]

- [85].Zhao R, Lu Z, Yang J, Zhang L, Li Y, Zhang X (2020) Drug Delivery System in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Frontiers Bioengin Biotechn 8: 880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Jin X, Zhang X, Wu Z, et al. (2009) Amphiphilic random glycopolymer based on phenylboronic acid: synthesis, characterization, and potential as glucose-sensitive matrix. Biomacromol 10(6): 1337–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wang Y, Huang F, Sun Y, Gao M, Chai Z (2017) Development of shell cross-linked nanoparticles based on boronic acid-related reactions for self-regulated insulin delivery. J Biomat Sci, Polymer Ed 28(1): 93–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wang H, Yi J, Yu Y, Zhou S (2017) NIR upconversion fluorescence glucose sensing and glucose-responsive insulin release of carbon dot-immobilized hybrid microgels at physiological pH. Nanoscale 9(2): 509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Dong Y, Wang W, Veiseh O, et al. (2016) Injectable and Glucose-Responsive Hydrogels Based on Boronic Acid–Glucose Complexation. Langmuir 32(34): 8743–8747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Zion TC, Tsang HH, Ying JY (2003) Glucose-sensitive nanoparticles for controlled insulin delivery. Available from: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/3783. Accessed: 31 January 2021 [Google Scholar]

- [91].Li X, Fu M, Wu J, et al. (2017) pH-sensitive peptide hydrogel for glucose-responsive insulin delivery. Acta Biomat 51:294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Anirudhan T, Nair AS, Nair SS (2016) Enzyme coated beta-cyclodextrin for effective adsorption and glucose-responsive closed-loop insulin delivery. Int J Biol Macromol 91: 818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Shi D, Ran M, Zhang L, et al. (2016) Fabrication of biobased polyelectrolyte capsules and their application for glucose-triggered insulin delivery. ACS Applied Mat Inter 8(22): 13688–13697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Taylor MJ, Chauhan KP, Sahota TS (2020) Gels for constant and smart delivery of insulin. Brit J Diabetes 20(1): 41–51 [Google Scholar]

- [95].Gu Z, Dang TT, Ma M, et al. (2013) Glucose-responsive microgels integrated with enzyme nanocapsules for closed-loop insulin delivery. ACS Nano 7(8): 6758–6766. 10.1021/nn401617u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Yesilyurt V, Webber MJ, Appel EA, Godwin C, Langer R, Anderson DG (2016) Injectable Self-Healing Glucose-Responsive Hydrogels with pH-Regulated Mechanical Properties. Adv Mater 28(1): 86–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Ito Y, Imanishi Y (1994) Protein device for glucose-sensitive release of insulin. Design and synthesis of a protein device that releases insulin in response to glucose concentration. Bioconjug Chem 5(1):84–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Hilgenfeld R, Seipke G, Berchtold H, D.R. Owens DR (2014) The Evolution of Insulin Glargine and its Continuing Contribution to Diabetes Care. Drugs 74 (8): 911–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Gillies PS, Figgitt DP, Lamb HM (2000) Insulin glargine. Drugs 59(2): 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Kashyap N, Steiner SS, Pohl R, inventors; Biodel, Inc., assignee. Insulin formulations for insulin release as a function of tissue glucose levels. US patent application 2009/0,175,840 A1. 9 July 2009.

- [101].Kaarsholm NC, Lin S, Yan L, et al. (2018) Engineering Glucose Responsiveness Into Insulin. Diabetes 67(2): 299–308. 10.2337/db17-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Yang R, Wu M, Lin S, et al. (2018) A glucose-responsive insulin therapy protects animals against hypoglycemia. JCI Insight 3(1):e97476. 10.1172/jci.insight.97476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Yang JF, Gong X, Bakh NA, et al. (2020) Connecting Rodent and Human Pharmacokinetic Models for the Design and Translation of Glucose-Responsive Insulin. Diabetes 69(8):1815–1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Taylor SI, DiMarchi RD (2020) Smarter modeling to enable a smarter insulin. Diabetes 69(8): 1608–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Visser SA, Kandala B, Fancourt C, Krug AW, Cho CR (2020) A Model-Informed Drug Discovery and Development Strategy for the Novel Glucose-Responsive Insulin MK-2640 Enabled Rapid Decision Making. Clin Pharm Therap 107(6): 1296–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Friedman S, Pizer R (1975) Mechanism of the complexation of phenylboronic acid with oxalic acid. Reaction which requires ligand donor atom protonation. J Am Chem Soc 97(21): 6059–6062 [Google Scholar]

- [107].Springsteen G, Wang B (2002) A detailed examination of boronic acid–diol complexation. Tetrahedron 58(26): 5291–5300. 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00489-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Wu X, Li Z, Chen X-X, Fossey JS, James TD, Jiang Y-B (2013) Selective sensing of saccharides using simple boronic acids and their aggregates. Chem Soc Rev 42(20): 8032–8048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Hoeg-Jensen T, Havelund S, Markussen J, inventors; Novo Nordisk A/S, assignee. Glucose-dependent insulins. US patent 7,317,000 B2. 8 January 2008.

- [110].Hoeg-Jensen T, Havelund S, Markussen J, Ostergaard S, Ridderberg S, Balschmidt P, Schaffer L, Jonassen I, inventors; Novo Nordisk A/S, assignee. Glucose dependent release of insulin from glucose sensing insulin derivatives. US patent 7,316,999 B2. 8 January 2008.

- [111].Jonassen I, Havelund S, Hoeg-Jensen T, Steensgaard DB, Wahlund PO, Ribel U (2012) Design of the novel protraction mechanism of insulin degludec, an ultra-long-acting basal insulin. Pharm Res 29(8): 2104–2114. 10.1007/s11095-012-0739-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Chou DH-C, Webber MJ, Tang BC, et al. (2015) Glucose-responsive insulin activity by covalent modification with aliphatic phenylboronic acid conjugates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112(8): 2401–2406. 10.1073/pnas.1424684112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Wang J, Yu J, Zhang Y, et al. (2019) Glucose transporter inhibitor-conjugated insulin mitigates hypoglycemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116(22): 10744–10748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Jensen KJ, Mannerstedt K, Mishra NK, et al. (2020) An Aldehyde Responsive, Cleavable Linker for Glucose Responsive Insulins. Chemistry. 10.1002/chem.202004878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Menting JG, Whittaker J, Margetts MB, et al. (2013) How insulin engages its primary binding site on the insulin receptor. Nature 493(7431): 241–245. 10.1038/nature11781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Menting JG, Yang Y, Chan SJ, et al. (2014) Protective hinge in insulin opens to enable its receptor engagement.Proc Natl Acad Sci 111(33): E3395–E3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Scapin G, Dandey VP, Zhang Z, et al. (2018) Structure of the insulin receptor-insulin complex by single-particle cryo-EM analysis. Nature 556(7699): 122–125. 10.1038/nature26153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Weis F, Menting JG, Margetts MB, et al. (2018) The signalling conformation of the insulin receptor ectodomain. Nat Commun 9(1): 4420. 10.1038/s41467-018-06826-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Weiss M, inventor; Case Western Reserve University, assignee. Insulin analogues with a glucose-regulated conformational switch. US patent 10,584,156 B2. 10 March 2020.

- [120].Angyal SJ (1984) The composition of reducing sugars in solution. In: Tipson RS, Horton D(eds), Advances in carbohydrate chemistry and biochemistry, vol. 42. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 15–68 [Google Scholar]

- [121].Bérubé M, Dowlut M, Hall DG (2008) Benzoboroxoles as efficient glycopyranoside-binding agents in physiological conditions: structure and selectivity of complex formation. J Org Chem 73(17): 6471–6479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Pal A, Bérubé M, Hall DG (2010) Design, synthesis, and screening of a library of peptidyl bis (boroxoles) as oligosaccharide receptors in water: identification of a receptor for the tumor marker TF-antigen disaccharide. Angewandte Chem Int Ed 49(8): 1492–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Sharma B, Bugga P, Madison LR, et al. (2016) Bisboronic acids for selective, physiologically relevant direct glucose sensing with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 138(42): 13952–13959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Bian Z, Liu A, Li Y, et al. (2020) Boronic acid sensors with double recognition sites: a review. Analyst 145(3): 719–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Sun X, James TD (2015) Glucose sensing in supramolecular chemistry. Chem Rev 115(15): 8001–8037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Davis AP (2020) Biomimetic carbohydrate recognition. Chem Soc Rev 49(9): 2531–2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Tromans RA, Samanta SK, Chapman AM, Davis AP (2020) Selective glucose sensing in complex media using a biomimetic receptor. Chem Sci 11(12): 3223–3227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Brunel FM, Mayer JP, Gelfanov VM, et al. (2019) A disulfide scan of insulin by [3+ 1] methodology exhibits site-specific influence on bioactivity. ACS Chem Biol 14(8): 1829–1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Zaykov AN, Mayer JP, Gelfanov VM, Dimarchi RD (2014) Chemical Synthesis of Insulin Analogs through a Novel Precursor. ACS Chem Biol 9(3): 683–691. 10.1021/cb400792s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Hua QX, Hu SQ, Frank BH, et al. (1996) Mapping the functional surface of insulin by design: structure and function of a novel A-chain analogue. J Mol Biol 264: 390–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Hua QX, Xu B, Huang K, et al. (2009) Enhancing the activity of insulin by stereospecific unfolding. Conformational life cycle of insulin and its evolutionary origins. J Biol Chem 284: 14586–14596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Bliss M (2103) The Discovery of Insulin: the twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL [Google Scholar]

- [133].Hovorka R (2011) Closed-loop insulin delivery: from bench to clinical practice. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 7(7): 385–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Jazowski SA, Winn AN (2017) The role of the FDA and regulatory approval of new devices for diabetes care. Curr Diabetes Rep 17(6): 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Boughton CK, Hovorka R (2019) Is an artificial pancreas (closed-loop system) for Type 1 diabetes effective? Diabet Med 36(3): 279–286. 10.1111/dme.13816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Beregszàszi M, Tubiana-Rufi N, Benali K, Noël M, Bloch J, Czernichow P (1997) Nocturnal hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: prevalence and risk factors. The Journal of pediatrics 131(1): 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group (1998) Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 352(9131): 837–853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. (2008) Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358(24): 2560–2572. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. (2009) Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 360(2): 129–139. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].The DCCT Research Group (1991) Epidemiology of severe hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. Am J Med 90(4): 450–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1997) Hypoglycemia in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 46(2): 271–286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. (2008) Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358(24): 2545–2559. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F (2012) Clinical Implications of the ACCORD Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(1): 41–48. 10.1210/jc.2011-1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Beran D, Hirsch IB, Yudkin JS (2018) Why are we failing to address the issue of access to insulin? A national and global perspective. Diabetes Care 41(6): 1125–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Rege NK, Phillips NFB, Weiss MA (2017) Development of glucose-responsive ‘smart’ insulin systems. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 24(4): 267–278. 10.1097/med.0000000000000345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Tromans RA, Carter TS, Chabanne L, et al. (2019) A biomimetic receptor for glucose. Nature Chem 11(1): 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Hua QX, Nakagawa SH, Hu SQ, Jia W, Wang S, Weiss MA (2006) Toward the active conformation of insulin. Stereospecific modulation of a structural switch in the B chain. J Biol Chem 281: 24900–24909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]