Abstract

Background

Collaborative practice involving nurse practitioners (NPs) and family physicians (FPs) is undergoing a renaissance in Canada. However, it is not understood what services are delivered by FPs and NPs working collaboratively. One objective of this study was to determine what primary health care services are provided to patients by NPs and FPs working in the same rural practice setting.

Methods

Baseline data from 2 rural Ontario primary care practices that participated in a pilot study of an outreach intervention to improve structured collaborative practice between NPs and FPs were analyzed to compare service provision by NPs and FPs. A total of 2 NPs and 4 FPs participated in data collection for 400 unique patient encounters over a 2-month period; the data included reasons for the visit, services provided during the visit and recommendations for further care. Indices of service delivery and descriptive statistics were generated to compare service provision by NPs and FPs.

Results

We analzyed data from a total of 122 encounters involving NPs and 278 involving FPs. The most frequent reason for visiting an NP was to undergo a periodic health examination (27% of reasons for visit), whereas the most frequent reason for visiting an FP was cardiovascular disease other than hypertension (8%). Delivery of health promotion services was similar for NPs and FPs (11.3 v. 10.0 instances per full-time equivalent [FTE]). Delivery of curative services was lower for NPs than for FPs (18.8 v. 29.3 instances per FTE), as was provision of rehabilitative services (15.0 v. 63.7 instances per FTE). In contrast, NPs provided more services related to disease prevention (78.8 v. 55.7 instances per FTE) and more supportive services (43.8 v. 33.7 instances per FTE) than FPs. Of the 173 referrals made during encounters with FPs, follow-up with an FP was recommended in 132 (76%) cases and with an NP in 3 (2%). Of the 79 referrals made during encounters with NPs, follow-up with an NP was recommended in 47 (59%) cases and with an FP in 13 (16%) (p < 0.001).

Interpretation

For the practices in this study NPs were underutilized with regard to curative and rehabilitative care. Referral patterns indicate little evidence of bidirectional referral (a measure of shared care). Explanations for the findings include medicolegal issues related to shared responsibility, lack of interdisciplinary education and lack of familiarity with the scope of NP practice.

The purpose of collaborative practice is to deliver comprehensive primary health care to meet the needs of a particular practice population, through full and effective application of the knowledge and skills of the health care providers. Comprehensive primary health care includes service delivery in 5 domains: health promotion, disease prevention (e.g., performing periodic health examinations), curative care (diagnosing and treating acute illness and injury), rehabilitative care (monitoring and treating chronic illness and disability) and supportive care.1

Family physicians (FPs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) bring both shared and unique knowledge and skills to their roles. FPs have the knowledge and skills to participate in all domains of care, with a primary responsibility for curative and rehabilitative care and service coordination. NPs bring their nursing knowledge and skills to population and individual health promotion, to disease prevention and to supportive care. In their extended role, NPs can also contribute to disease prevention, curative care and rehabilitative care. The NPs in the study reported here were certified in Ontario as registered nurses in the extended class and had the legislated authority to carry out this extended role.2,3,4,5

A recent Cochrane review indicated that there is no rigorous evidence supporting the use or abandonment of strategies to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care.6 Two of us (D.W. and L.J.)7 previously described a structured collaborative practice, and the accompanying editorial challenged us to further our research in this area.8 We have now undertaken a pilot study of an educational intervention to improve structured collaborative practice between NPs and FPs. In this article we report baseline data on service provision at 2 of 4 rural Ontario sites participating in an evaluation of the intervention. The primary objective of the current analysis was to determine which primary health care services are provided to patients by NPs and FPs working in the same practice setting. Specifically, the study was designed to answer the following questions:

· What specific patient problems do NPs and FPs address?

· For these 2 groups of practitioners, what is the frequency of activity within each of the 5 domains of primary health care?

· To what degree do NPs and FPs share the care of their patients?

Methods

As part of our evaluation of an intervention to improve structured collaborative practice, we conducted a cross-sectional study to obtain a baseline estimate of service provision in primary care settings

We approached 6 rural primary care practice sites, asking them to participate in an intervention to improve collaborative practice. To be eligible for inclusion, rural sites had to have practising NPs and FPs. Potential participants from Nunavut, Saskatchewan and Ontario were approached. Four sites agreed to participate, 2 in eastern Ontario and 2 in northern Ontario. At least 1 NP and 2 FPs were practising at each site, and a total of 5 NPs and 13 FPs took part in the study. Baseline data on patient encounters were collected by 2 NPs and 4 FPs at the eastern Ontario sites and 3 NPs and 9 FPs at the northern Ontario sites. However, the data from the northern Ontario sites were withdrawn because of concerns about the process for patient consent. The research protocol called for NPs and FPs to give consent to the completion of non-nominal patient encounter forms and for patients to give consent to be interviewed. Administrators at the 2 northern Ontario sites disagreed with the release of patient encounter data without individual patient consent.

We developed a patient encounter form, to be completed by the NP or the FP, and a patient interview form, to be completed by a data collector. We pilot-tested the forms at 2 urban community health centres. A data collector trained in the data collection protocol for this study and hired from the community was available for each site. The NPs and FPs completed a patient encounter form for each patient seen on the days when the data collector was present. A sample of these patients was then selected by convenience from the appointment register. Selected patients were approached, after completing the visit with the health care provider, for a same-day, on-site interview, during which the data collector completed the patient interview form. Patients were asked to provide informed consent before they were interviewed. The health care providers were not aware of which patients had agreed to be interviewed.

The following data were collected through the encounter and interview forms: sex; date of birth; reason for visit, problem or diagnosis; language spoken at home; employment status; services provided by the NP or the FP (or both) during the encounter, grouped according to the 5 domains of primary health care; and recommendations for further care (in-house follow-up, external referral or both). The frequency of activity in each of the 5 domains (Table 1) was computed for each patient encounter. Lifestyle counselling to individuals was used as the measure of health promotion activity. The diagnoses or the reasons for visiting the clinic, as given on the encounter form, were recoded on the basis of common acute and chronic conditions of various body systems; our categories were adapted from the coding conventions described by Stange and colleagues.9

Table 1

Frequency tables were generated for categorical and nominal data. Descriptive statistical procedures were used for continuous variables. To compare sites, contingency table analysis and a χ-square statistic were generated for categorical data, and a one-way analysis of variance was used for continuous data, along with tests for multiple comparisons. Multiple response tables were generated as appropriate. In addition to calculating absolute numbers of services provided and referrals made, we also determined the rates on the basis of full-time equivalents (FTEs) for each type of health care provider (1.6 FTE NPs and 3.0 FTE FPs).

Results

A total of 958 unique patient encounters took place at the 2 eastern Ontario sites over a 2-month period (September and October 1999): 548 at one site in 42 days and 374 at the other site in 30 days. There were more encounters at one site than the other because of differences in practice size. A total of 566 patient encounters were selected from visits for which completed encounter forms were available. For 96 of the encounters, the patient was not interviewed because he or she had already been interviewed for this study with respect to a previous encounter. Therefore, there were 470 eligible patients; of these, 400 patients (200 from each site) consented to be interviewed, 122 who had been seen by an NP and 278 who had been seen by an FP. Reasons for refusal were as follows: 42 patients were unwilling to participate, 16 did not have the time to complete the interview, 7 were not fluent in English and 5 were too ill to participate.

A total of 260 (65%) of the 400 participants were female. For almost all participants (392 [98%]), the language spoken at home was English. Participants were significantly older than nonparticipants (49.2 v. 43.1 years, p < 0.001), but the 2 groups did not differ with regard to sex.

Overall, the most frequent reasons for visits were periodic health examination (16%), acute respiratory infection (9%), diabetes mellitus (7%), acute musculoskeletal conditions (6%) and cardiovascular conditions other than hypertension (5%).

The 5 most frequent reasons for visiting an NP were periodic health examination (27%), acute respiratory infection (12%), diabetes mellitus (8%), contraception and pregnancy (5%) and hypertension (4%). The 5 most frequent reasons for visiting an FP were cardiovascular conditions other then hypertension (10%), acute musculoskeletal conditions (8%), diabetes mellitus (7%), periodic health examination (5%) and acute mental illness (4%).

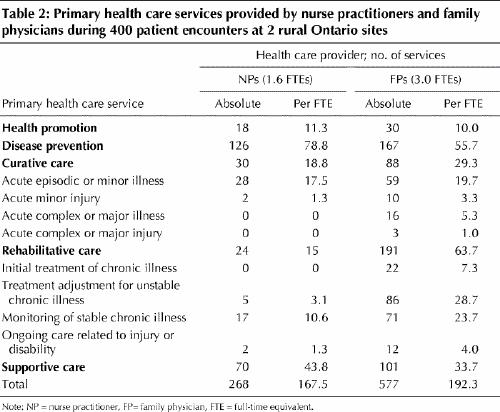

The number of services provided per FTE health care provider offers the most accurate view of service delivery. In these terms, health promotion activity, as measured by lifestyle counselling, was comparable between NPs and FPs (11.3 v. 10.0 instances) (Table 2). NPs provided fewer curative and rehabilitative services than FPs on a per-FTE basis (18.8 v. 29.3 and 15.0 v. 63.7 respectively) (Table 2). In contrast, NPs provided more disease prevention and supportive services than FPs on a per-FTE basis (78.8 v. 55.7 and 43.8 v. 33.7 respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2

Within the curative domain, NP involvement was primarily related to acute episodic illness; in this category of curative care, activity was similar for NPs and FPs (17.5 and 19.7 instances per FTE) (Table 2). Within the rehabilitative domain, NPs were primarily involved in monitoring stable chronic conditions; in this category, activity was much lower for NPs than for FPs (10.6 v. 23.7 instances per FTE) (Table 2).

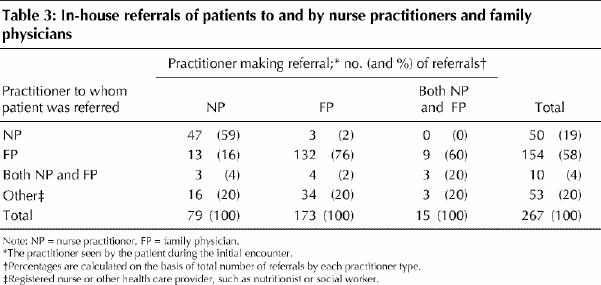

During 267 of the encounters, follow-up visits were recommended. During these initial encounters, 173 patients (65%) saw an FP, 79 (30%) saw an NP, and 15 (6%) saw both (Table 3). For the 173 encounters with an FP only, follow-up with an FP was recommended for 132 (76%) patients, whereas follow-up with an NP was recommended for 3 patients (2%). In contrast, for the 79 encounters with an NP only, follow-up with an NP was recommended for 47 (59%) patients, and follow-up with an FP was recommended for 13 patients (16%) (p < 0.001).

Table 3

Interpretation

In this study, NPs' involvement in curative services related to acute episodic illness and clinical health promotion was similar to that of FPs (on a per-FTE basis). Their involvement in rehabilitative care was much lower than that of FPs, whereas their involvement in disease prevention and supportive care was greater than that of FPs. Referral patterns were more unidirectional (NP to FP) than bidirectional (NP to FP and FP to NP).

In a descriptive study conducted in Ontario in spring 1999, 123 NPs reported their service delivery as follows: 31% acute care (curative domain) and 29% chronic care and palliative care (rehabilitative domain).17 In contrast, for the NPs in the study reported here, only 11% (30) of the 268 services documented were characterized as acute care and only 9% (24) were characterized as chronic care, including palliative care.

Periodic health examination ranked as the primary reason for visits to the NP, similar to the result in a study of Tennessee NPs.10 Acute respiratory illness (acute episodic illness) and reproductive issues also ranked high in both studies. In contrast to our findings, chronic conditions (specifically hypertension and diabetes) ranked higher for the Tennessee NPs. The comparable involvement of FPs and NPs in clinical health promotion and the greater involvement of NPs in disease prevention and supportive care that we observed are consistent with professional role descriptions.2,3,4,5,22

No guidelines are available with regard to the expected involvement of each discipline in primary health care in rural settings. Such guidelines would need to be sufficiently flexible to reflect specific practice needs. However, the application of the NPs' extended role at these 2 sites was less than would be expected on the basis of the literature regarding NP practice. For example, British, American and previous Canadian studies have addressed the extensive role of NPs in acute care management and monitoring of chronic illnesses.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21

Data about the provider seen during the visit and about in-house referral were used to answer the question of the degree to which NPs and FPs share in caring for their patients. Only a few patients saw both an NP and an FP in the same visit. Of referrals by NPs, 16% were to FPs; in contrast, only 2% of referrals by FPs were to NPs. These data do not provide strong evidence of collaborative care.

A variety of reasons may explain our findings. First, FPs lack familiarity with the full scope of practice of NPs. The first Canadian NP initiative was started in the 1970s but ended in the early 1980s, leaving few practising NPs and therefore few opportunities for shared practice between NPs and FPs. The educational program was reinstated in Ontario in 1995, supporting legislation was proclaimed, and certification in an extended class was begun in 1998. However, current Ontario funding of NP positions has been primarily confined to agencies with global funding, with some positions in underserviced areas that include rural physician practices. As well, there is a lack of interdisciplinary education at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels.23 FPs may be hesitant to become involved in shared decision-making because of unclear medicolegal responsibilities. Although FPs may be unclear about when to consult with or refer patients to NPs, Ontario certification clearly indicates when an NP must consult with or refer patients to an FP. Patients who are seeing an FP may choose not to be referred to another provider and may not have experience with or understanding of the extended nursing role. The Ontario NP regulated drug list may be a barrier to NP involvement in rehabilitative care, because it does not allow for independent renewal of medications for stable chronic conditions.

The study had a number of limitations. Because we were able to analyze data from only 2 sites, our findings cannot be generalized to all Ontario rural practices where both NPs and FPs work. At one of the sites, the NP positions had been in place for less than a year. Data about services provided depends on conscientious and consistent recording of all activities during a visit, but we did not assess the consistency and quality of data recorded by the NPs and FPs. Finally, patients who participated in the study were significantly older than nonparticipants.

A multitude of authors have emphasized the need for collaborative practice involving NPs and FPs. All jurisdictions in Canada face challenges in providing adequate human resources for health care delivery. NP initiatives begun in the 1990s and now in various stages of implementation involve most provinces and the 3 territories.22,24,25,26,27,28,29 Common to all of these initiatives is the goal of increasing access to primary health care through the integration of NPs into collaborative practice and the inclusion of the extended NP skill set as part of the role description. Primary care practices will be challenged to use NP resources appropriately as their availability increases. Our data suggest that strategies to improve collaborative practice, in particular by using NPs more effectively in the management of acute episodic and stable chronic illness, and to promote bidirectional referral between NPs and FPs, could assist in optimizing care delivery within currently available resources. Our project team is continuing our research in this area to determine the effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve collaboration between NPs and FPs.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements: All authors were members of the research team for the project “Improving the Effectiveness of Primary Health Care Delivery through Nurse Practitioner / Family Physician Structured Collaborative Practice,” a joint endeavour of the School of Nursing and the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Ottawa, funded by Health Canada's Health Transition Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Daniel Way, Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa, Elisabeth-Bruyère Pavilion, 43 Bruyère St. (375 Floor 3JB), Ottawa ON K1N 5C8

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Primary health care: report of the international conference on PHC. Geneva: The Organization; 1978.

- 2.Canadian Medical Association. Strengthening the foundation: the role of the physician in primary health care in Canada. Ottawa: The Association; 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.College of Family Physicians of Canada. Primary care and family medicine in Canada: a prescription for renewal. Toronto: The College; 2000.

- 4.College of Nurses of Ontario. Standards of practice for registered nurses in the extended class. Toronto: The College; 1998.

- 5.Way D, Jones L, Busing N. Implementation strategies: “collaboration in primary care — family doctors and nurse practitioners delivering shared care” [discussion paper]. Toronto: Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2000.

- 6.Zwarenstein M, Bryant W, Baillie R, Sibthorpe B. Interventions to promote collaboration between nurses and doctors [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 4, 1998. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Way DO, Jones LM. The family physician–nurse practitioner dyad: indications and guidelines. CMAJ 1994;151(1):29-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Moore CA. Family physicians and nurse practitioners: guidelines, not battlelines. CMAJ 1994;151(1):19-21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, Callahan EJ, Kelly RB, Gillanders WR, et al. Illuminating the “black box”. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract 1998;46(5):377-89. [PubMed]

- 10.Moody B, Smith PL, Glenn L. Client characteristics and practice patterns of nurse practitioners and physicians. Nurse Pract 1999;24(3):94-103. [PubMed]

- 11.Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, Totten AM, Tsai WY, Cleary PD, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2000;283(1):59-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mitchell A, Pinelli J, Patterson C, Southwell D. Utilization of nurse practitioners in Ontario [discussion paper]. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health; 1993.

- 13.Shum C, Humphreys A, Wheeler D, Cochrane MA, Skoda S, Clement S. Nurse management of patients with minor illnesses in general practice: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2000;320:1038-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Brown S, Grimes D. Nurse practitioners and certified nurse-midwives: a meta-analysis of studies on nurses in primary care roles. Washington: American Nurses Association; 1993. [PubMed]

- 15.Brown S, Grimes D. A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nurs Res 1995;44:332-9. [PubMed]

- 16.Kinnersley EA, Anderson E, Parry K, Clement J, Archard L, Turton P, et al. Randomised controlled trial of nurse practitioner versus general practitioner care for patients requesting “same day” consultations in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:1043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sidani S, Irvine D, DiCenso A. Implementation of the primary care nurse practitioner role in Ontario. Can J Program Eval 2000;13(3):13-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Spitzer W, Sackett D, Sibley JC, Roberts M, Gent M, Kergin D, et al. The Burlington Trial of the Nurse Practitioner. N Engl J Med 1974;290(5):251-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Spitzer W, Robin S, Roberts M, Delmore T. Nurse practitioners in primary care. VI. Assessment of their deployment with the utilization and financial index. CMAJ 1976;114:1103-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. RN effectiveness: clinical, financial, and systems outcomes focus on 1994–1997 literature: primary health care nurse practitioner. Toronto: The Association; 1998. p. 8-1 to 8-6.

- 21.Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. RN effectiveness: clinical, financial, and systems outcomes focus on 1998 literature: primary health care nurse practitioner. Toronto: The Association; 1999. p. 3.

- 22.Ontario Ministry of Health. Nurse practitioners in Ontario: a plan for their education and employment. Toronto: The Ministry; 1994.

- 23.Pringle D, Levitt C, Horsburgh ME, Wilson R, Whittaker MK. Interdisciplinary collaboration and primary health care reform. Can J Public Health 2000;91(2):85-88,97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Advisory Committee on Health Human Resources. Final report: the nature of the extended/expanded nursing role in Canada. St. John's: Centre for Nursing Consultants; 2000. Available: www.cns.nf.ca/research/research.html (accessed 2001 Sep 18).

- 25.Alberta Association of Registered Nurses. Competencies for registered nurses providing extended health services in the province of Alberta. Edmonton: The Association; 1995.

- 26.Association of Registered Nurses of Newfoundland. Plan of action for the utilization of nurses in advanced practices throughout Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John's: The Association; 1997.

- 27.Northwest Territories Medical Association and Northwest Territories Registered Nurses Association. The provision of primary health care in the Northwest Territories: a joint statement on health care reform in the NWT. Yellowknife: The Associations; 1998.

- 28.Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association, Saskatchewan College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Saskatchewan Pharmaceutical Association. A letter of understanding between the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses Association, the Saskatchewan College of Physicians and Surgeons, and the Saskatchewan Pharmaceutical Association in respect to the Beechy Project. Regina: The Associations and The College; 1995.

- 29.Short P. Nurse practitioners in New Brunswick [discussion paper]. Moncton: Worklife Redesign Committee; 1996.