Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) is regarded as a high-grade malignancy in the current classification of salivary gland neoplasms. The aim of our study was to describe the MR imaging features of SDC.

METHODS: Nine patients with SDC underwent MR imaging study. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values of SDCs were measured from diffusion-weighted images. Time–signal intensity curves (TICs) of the tumors on dynamic MR images were plotted, and washout ratios were also calculated. TICs were divided into four types: type A, curve peaks <120 seconds after administration of contrast material with high washout ratio (≥30%); type B, curve peaks <120 seconds with low washout ratio (<30%); type C, curve peaks >120 seconds; type D, nonenhanced. We correlated the MR findings of SDC with the pathologic findings.

RESULTS: All tumors had ill-defined margins and showed low to moderately high signal intensity for contralateral parotid gland on T2-weighted images. The average of the ADC values of the SDCs was 1.16 ± 0.14 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s. Seven of nine (78%) tumors had type B enhancement. On the other hand, six of nine (67%) tumors with rich fibrotic tissue also had type C enhancement.

CONCLUSION: The findings of ill-defined margin, early enhancement with low washout ratio (type B), and low ADC value (1.22 × 10−3mm2/s) were useful for suggesting malignant salivary gland tumors. Although it was reported that type C enhancement was specific for pleomorphic adenoma, SDC frequently has type C-enhanced focus.

Salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) is a rare, distinctive, and aggressive neoplasm of salivary glands. Structures of SDC are characterized by a striking resemblance to mammary duct carcinoma. Comedonecrosis is a frequent feature. SDC was first described by Kleinsasser et al (1) and was included in the recent World Health Organization classification (2). To the best of our knowledge, MR images of this rare entity have not been reported in the English-language literature. We present nine SDCs in parotid glands on MR images, including T1-weighted, T2-weighted, short-inversion-time inversion recovery (STIR), diffusion-weighted (DW), and dynamic contrast-enhanced MR (dynamic MR) images.

Methods

Subjects

Between May 2000 and January 2004, we encountered 12 SDCs, but three of them—carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenomas—were excluded. The nine patients with de novo SDC—seven men and two women with a mean age of 62 years (range, 37–83 years)—underwent MR imaging. Eight of them had a palpable hard mass in the parotid gland, and one had a hard mass in the submandibular gland. Of the eight patients with parotid tumors, two (25%) complained of parotid pain and six (75%) suffered ipsilateral facial nerve palsy.

MR Imaging Techniques

All MR examinations were performed by using 1.5T MR imaging units (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) with a neurovascular array coil. T1-weighted images (400–500/9–14 [TR, ms/TE, ms]), T2-weighted images (4000/104, 16 [echo train length]), STIR images (4000/30, 12 [echo train length], 150 [TI, ms]), DW images (spin-echo single-shot echo-planar sequence with b factors of 0 and 1000 s/mm2) were obtained at a section thickness of 6 mm, an intersection gap of 1 mm, an acquisition matrix of 256 × 256 (128 × 128 on DW images), and a field of view (FOV) of 22 × 22 cm. Dynamic MR images were obtained by 3D fat-suppression T1-weighted multiphase spoiled gradient-recalled-echo (6.3/1.4 [TR, ms/TE, ms]) for 4 minutes, with each phase lasting 27 seconds followed by a 3-second interval, an effective section thickness of 4 mm, FOV of 22 × 22 cm, and an acquisition matrix of 256 × 224. After the first set was obtained, contrast material injection was started immediately. Gadodiamide hydrate (Omniscan, Daiichi Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) was administered (0.2 mL/kg body weight) at a rate of 2.0 mL/s followed by a 20-mL saline flush into the antecubital vein. Seven sets of dynamic MR images were obtained serially. Soon after the dynamic MR imaging, fat-suppression T1-weighted images (340–400/20 [TR, ms/TE, ms]) were obtained with an acquisition matrix of 256 × 224. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were automatically constructed from DW images. T1-weighted, STIR, gadolinium-enhanced dynamic images, and fat-suppression contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted images were obtained from all nine cases of SDC. T2-weighted images were obtained from six cases and DW images from seven cases.

Images and Pathologic Analysis

One radiologist (T.U.) measured the signal intensities of the lesions on each dynamic image with an electronic cursor to define the region of interest in each patient. Where markedly heterogeneous enhancement was seen, multiple regions of interest were obtained. TICs were then plotted from signal intensity values obtained for the tumors, the ipsilateral artery, and the ipsilateral vein. Washout ratio was calculated by a modified method of that of Yabuuchi et al (3) as follows:

|

where SImax was the signal intensity at maximal contrast enhancement, SIlast the signal intensity at the last serial image of the dynamic study, and SIpre the precontrast signal intensity. TICs were divided into four types according to those of Yabuuchi et al (3): type A, curve peaks <120 seconds after administration of contrast material with high washout ratio (≥30%); type B, curve peaks <120 seconds with low washout ratio (<30%); type C, curve peaks >120 seconds; type D, nonenhanced.

The ADC values of the SDCs were measured on each DW image with an electronic cursor to define the region of interest. The ADC values of the spinal cord on DW images were also measured to assess the validity of our method and to compare our findings with the results from previous investigations. The tumors were marked at the top during surgery. For MR images, they were cut on an axial plane. An experienced radiologist (K.M.) and a pathologist (Y.N.) correlated the findings from MR images and pathologic specimens. We attempted to identify the areas within the tumor as corresponding to hypointensity on STIR and T2-weighted images and also to identify each area corresponding to type A, B, and C curves on dynamic study.

Results

Eight SDCs occurred in parotid glands and one in the submandibular gland. The average maximal cross-sectional diameter was 3.7 cm (range, 2.2–5.2 cm). All tumors showed invasive or ill-defined margins on T1-weighted, T2-weighted, STIR, and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig 1A–C). On T1-weighted images, all tumors showed hypointensity for parotid gland and isointensity for muscle (Fig 1C). On T2-weighted and STIR images, all tumors showed low to moderately high signal intensity for contralateral parotid gland (Fig 1A and B). The signal intensities of the tumors on T2-weighted images were lower than those of the tumors on STIR images (Fig 1A and B). There was no focus that showed higher signal intensity than that of cerebral spinal fluid on STIR and T2-weighted images.

Fig 1.

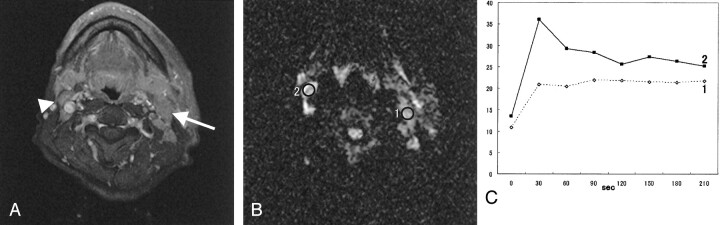

SDC in the left parotid gland of a 48-year-old man.

A, T2-weighted image (4000/104 [TR/TE], coronal plane) shows a tumor with ill-defined margin. The tumor shows low (arrow) to moderately high signal intensity for the contralateral parotid gland.

B, STIR image (4000/30, axial plane) also shows a hypointensity focus (arrow) in the tumor. The border of the tumor is invasive (arrowheads).

C, T1-weighted image (400/9, axial plane) shows an isointense tumor.

D, Third phase images on dynamic study (6.3/1.4, axial plane) show irregular enhancement. Marked enhanced area (region of interest 1), well-enhanced area (region of interest 2), and gradual upward enhanced area (region of interest 3) are detected.

E, Signal intensity graph shows that the washout ratio of region of interest 1 is 35% (type A) and that of region of interest 2 is 13% (type B). Time–signal intensity curves of region of interest 3 show gradual upward enhancement (type C).

F, Radical parotidectomy including facial nerve, mastoid tip, and skin was performed. Tumor extension from the cut specimen (arrowheads) is in good agreement with the MR images. The focus showing hypointensity on STIR and T2-weighted images and gradual upward enhancement on dynamic MR images corresponding to the fibrotic area (asterisk).

G, The light-optic appearance (original magnification ×40) in region of interest 1 shows abundant atypical epithelial cells (white asterisks) with fibrotic stromata (black asterisks).

H, The light-optic appearance (original magnification ×40) in region of interest 2 shows atypical epithelial cells (white asterisks) with fibrotic stromata and many foci of comedonecrosis (double asterisks).

I, The light-optic appearance (original magnification ×40) in region of interest 3 shows dense fibrotic tissue with cellular components (white asterisk).

On dynamic MR images, the artery curve peaked at 3–30 seconds after the administration of contrast agent and the vein curve peaked at 33–60 seconds. Three of the nine (33%) SDCs showed homogeneous enhancement and six of nine (67%) showed heterogeneous enhancement (Table): homogeneously enhanced SDCs, type B in two cases and type C in one case; and heterogeneously enhanced SDCs, type A plus B plus C in one case (Fig 1), type B plus C in three cases, type B plus C plus D in one case, and type B plus D in one case.

MR features of 9 patients with salivary duct carcinoma

| Patient | Age (yr) | Sex | Site | Size (cm) | LNs | TICs | ADC Value (×10−3 mm2/s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | M | rt parotid | 3.2 | Yes | B (11–25) | C | ||

| 2 | 81 | M | rt parotid | 2.1 | No | B (22) | C | ||

| 3 | 37 | M | rt parotid | 3.4 | Yes | B (11) | C | D | 1.03 |

| 4 | 65 | F | rt parotid | 4.0 | No | B (12) | D | 1.06 | |

| 5 | 83 | M | rt parotid | 3.4 | No | C | 1.43 | ||

| 6 | 52 | M | lt parotid | 3.8 | Yes | B (27) | C | 1.15 | |

| 7 | 60 | M | rt parotid | 2.1 | Yes | B (1) | 1.20 | ||

| 8 | 48 | M | lt parotid | 4.5 | No | A (35) | B (13) | C | 1.18 |

| 9 | 83 | F | lt submandibular | 2.8 | Yes | B (19) | 1.05 |

Note.—LNs indicates lymph nodes, TICs, time-signal intensity curves, Washout ratio (WR) in parentheses, expressed as percentage.

All DW images of SDCs showed irregularly high signal intensities. The average of the ADC values of the SDCs was 1.16 ± 0.14 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s (range of ADC values, 1.03–1.43), and that a range of ADC values of spinal cord was 1.05 ± 0.06 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s (0.99–1.15).

Specific cervical lymph nodes >10 mm in minimal axial diameter were found in five cases. Two of the five had irregularly enhanced lymph nodes on contrast-enhanced, fat-suppression T1-weighted images. Nonspecific cervical lymph nodes <10 mm were found in three cases. We could not detect cervical lymph nodes in one case.

Correlations between Radiologic and Pathologic Findings

All tumors had incomplete capsules and invasive borders. The light-optic appearance of the carcinomas resembled that seen in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Architectures of the tumor cells were variable in each case, including solid, papillary, micropapillary, cribiform, and infiltrative patterns. Many tumors had central desmoplasia (Fig 1). The pattern of enhancement on dynamic MR images in central desmoplastic areas was gradual upward enhancement (type C). The area also showed iso- to hypointensity on STIR and T2-weighted images. In the peripheral zones of the tumors, fibrosis, necrosis, comedonecrosis, tumor cells, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration were mixed at various proportions. The combinations were slightly different in each case. The various proportions resulted in a variety of TICs on dynamic MR images: type A, cellular component-dominant area showing early enhancement and high washout ratio (Fig 1G); type B, cellular components with many necrotic foci and fibrosis showing early enhancement with poor washout (Fig 1H); and type C, abundant fibrotic tissue with few cellular components showing gradual upward enhancement (Fig 1I).

Pathologically, five of nine (55.6%) SDCs had metastatic lymph nodes. Four of the five cases with lymph nodes >10 mm in minimal axial diameter were positive, and the other showed reactive change. All cases with smaller lymph nodes were negative. One case without detectable cervical lymphadenopathy had metastatic lymph nodes that were involved in the primary tumor. Reactive lymph nodes showed type A curve on dynamic study. In a case of left parotid SDC with ipsilateral metastatic lymphadenopathies, a metastatic lymph node showed type B curve and a contralateral reactive lymph node showed type A curve (Fig 2). The ADC value of the metastatic lymph node (1.23 × 10−3mm2/s) was higher than that of the reactive lymph node (0.90 × 10−3mm2/s). Reactive lymph nodes possessed the whole normal lymph node structures without the size. Malignant cells were involved in the metastatic lymph nodes, which also contained microscopic necrotic foci, hemorrhagic changes, and reactive fibrosis. Macrosopic necrosis showed hypointensity on contrast-enhanced, fat-suppression T1-weighted imaging.

Fig 2.

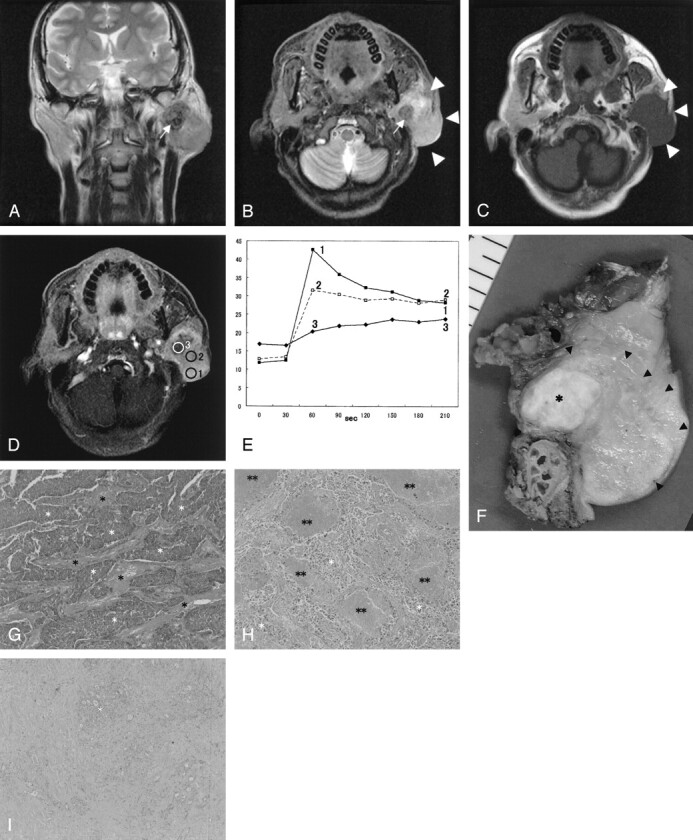

SDC in the left parotid gland of a 52-year-old man. He has ipsilateral metastatic lymph nodes and contralateral reactive lymph nodes.

A, Fat-suppression T1-weighted image (340/20, axial plane) shows multiple cervical lymphadenopathies. Metastatic lymph node (arrow) is >10 mm in minimal axial diameter. Reactive lymph node (arrowhead) is <10 mm in minimal axial diameter.

B, On diffusion-weighted image (spin-echo single-shot echo-planar sequence with b factors of 0 and 1000 s/mm2), both lymph nodes show high signal intensity. The ADC value of the metastatic lymph node (region of interest 1) is 1.23 × 10−3 mm2/s and that of the reactive lymph node is 0.90 × 10−3 mm2/s.

C, Signal intensity graph shows that the washout ratio of region of interest 1 is 2% (type B) and that of region of interest 2 is 48% (type A).

Discussion

SDC is a high-grade malignancy occurring predominantly in the major salivary glands of older male patients (4–14). SDC is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage; in our study, 75% of the patients had facial nerve palsy and 50% of SDCs had already spread to cervical lymph nodes. Surgery and postoperative radiation therapy was the treatment of choice. Despite this aggressive treatment, most patients died within 2–3 years. Local recurrence in SDC has been reported in 16–55% of the cases (9–14). Although local recurrence in this tumor, as well as neck recurrence, is very frequent, it does not present a major clinical problem. Distant metastases are the most common cause of death. Distant spread is related to the presence of metastatic lymph nodes rather than T categories (14). Wide local resection and prophylactic ipsilateral neck dissection have a possible preventive role in distant spread (14). MR imaging is an established and useful way of demonstrating the morphology and extent of head and neck tumors, as well as their relationship with adjacent structures. If, however, MR imaging could make a suggestion of SDC as one of differential diagnosis, its role would have an added value.

SDC is composed of atypical epithelial cells arranged in varying proportions of cribriform, papillary, micropapillary, or solid growth patterns with fibrotic stromata. Comedonecrosis is present in most cases. Perineural, venous, and lymph duct invasions are also common findings. In our study, SDCs had dense fibrosis in the center. On the other hand, in the peripheral zone of the tumors, fibrosis, necrosis, comedonecrosis, tumor cells, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration were at various proportions. Hypointensity on STIR and T2-weighted images and gradual upwardly enhanced foci on dynamic MR images corresponded to the areas with desmoplasia. According to Yabuuchi et al (3), in a study including 22 benign and 11 malignant tumors, gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MR imaging was useful for predicting whether salivary gland tumors were benign or malignant. They reported that a short time of peak enhancement, <120 seconds, and a low washout ratio, <30% (type B), on dynamic MR images were useful criteria for the diagnosis of malignant tumor. They also reported that a gradual upward enhanced tumor (type C) was pleomorphic adenoma. According to Tsushima et al (15), pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma showed gradual upward enhancement. In their study of malignant parotid tumors, except for adenoid cystic carcinoma, three squamous cell carcinomas, two mucoepidermoid carcinomas, one lymphoma, and one acinic cell carcinoma showed early enhancement. In our study, eight of nine (89%) tumors presented an enhancement pattern of malignancy: pure type B in two cases, type B plus C in three cases, type B plus D in one case, type B plus A plus C in one case, and type B plus C plus D in one case. On the other hand, six of nine (67%) tumors had a gradual upwardly enhanced pattern (type C): pure type C in one case, type C plus B in three cases, type C plus A plus B in one case, and type C plus B plus D in one case. The gradual enhancement of pleomorphic adenoma corresponds to myxoid stromata (16). Adenoid cystic carcinomas also have rich interstitial space filled with mucin (15). Myxoid stromata and mucin show high signal intensity on STIR and T2-weighted images (16, 17). The gradual enhanced focus of SDC corresponding to desmoplasia is iso- to hypointense to surrounding structures on STIR and T2-weighted images. Structures of SDC are characterized by a striking resemblance to mammary duct carcinoma. In a case of invasive ductal carcinoma, the central portion of the tumor showed gradual upward enhancement on dynamic MR images because of the low density of microvessels in this region, which is associated with prominent fibrosis (18). Fibrosis can be differentiated from myxoid stromata on the basis of signal intensity characteristics on STIR and T2-weighted images.

According to Wang et al (19), an ADC value <1.22 × 10−3mm2/s was one of the criteria for predicting malignancy. In our study, the average ADC values of SDC (1.16 ± 0.14 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s) agreed well with their data. One tumor showed a slightly high ADC value (1.43 × 10−3mm2/s); this tumor had abundant microscopic necrotic foci, but they could not be detected on MR images. There was a possibility that these many microscopic necroses were the cause of the elevated ADC value. Usually, the mean ADC value of cystic and necrotic components is higher than that of cellular tissue, because the mobility of water protons is relatively freer in fluid than in other tissues.

MR imaging also has the task of identifying gross metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy. Metastasis was suggested if a cervical lymph node was >10 mm in minimal axial diameter (20). Irregular enhancement on contrast-enhanced, fat-suppression T1-weighted imaging was also suggestive of metastatic lymph nodes (21). In our study, four of five pathologically positive cases and one of four pathologically negative cases had lymph nodes >10 mm in minimal axial diameter. In a false-negative case, metastatic lymph nodes could not be detected because of involvement in the primary tumor. In a false-positive case (Fig 2), although metastasis was suggested because of the size of the minimal axial diameter, the type A curve of TIC on dynamic study was atypical for metastasis. The type A curve is a criterion standard for a benign lesion (3). In the case of left SDC with ipsilateral metastatic lymphadenopathies (Fig 2), a metastatic lymph node showed a type B curve and a contralateral reactive lymph node showed a type A curve, and the ADC value of the metastatic lymph node was higher than that of the reactive lymph node (1.23 vs 0.90 × 10−3mm2/s). In our study, the average ADC value of SDCs (1.16 ± 0.14 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s [1.03–1.43]) was higher than that of spinal cord (1.05 ± 0.06 [SD] × 10−3mm2/s [0.99–1.15]). According to Wang et al (18), the ADC value of malignant lymphoma (0.66 ± 0.17 [SD] × 10−3 mm2/s) is lower than that of spinal cord. In the state of hypercellularity with less extracellular space as seen in lymphoma, the mobility of water protons is relatively limited. Thus, it was not surprising that the reactive lymph node showed a low ADC value. Microscopic necrosis and hemorrhagic changes caused the ADC values of metastatic lymph nodes to be higher than those of reactive lymph nodes. The size criterion for cervical lymph node metastasis, 10 mm or more in minimal axial diameter, showed 80% sensitivity and 75% specificity. Combining the information of type B curve on dynamic study and the approximate ADC value to primary tumor strongly suggested metastatic lymph nodes. This information improved sensitivity from 80% to 100% and specificity from 75% to 80%.

Conclusion

The current series shows that various MR imaging findings correlated well with the pathologic findings of SDC. The findings of ill-defined margin, early enhancement with low washout ratio (type B) on dynamic MR images, and low ADC value (1.22 × 10−3mm2/s) were useful for suggesting malignant salivary gland tumors. Although it was reported that gradual upward enhancement (type C) was specific for pleomorphic adenoma, SDC frequently has a type C enhanced focus. The gradual enhanced foci of pleomorphic adenoma showed marked high intensity on STIR and T2-weighted images, a feature associated with myxoid stromata. On the other hand, the gradual enhanced foci of SDC had prominent fibrosis and showed lower signal intensity on STIR and T2-weighted images. The focus in SDC that shows gradual upward enhancement on dynamic MR images and hypointensity on STIR and T2-weighted images may be a clue for making a diagnosis of SDC and separating SDC from the more common malignant salivary gland tumors such as mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma.

References

- 1.Kleinsasser O, Klein HJ, Hubner G. Speichelgangcarcinomas: Ein den Milchgangcarcinomen der Brustdruse Analoge Gruppe von Speicheldrusentumoren. Arch Klin Exp Ohren Nasen Kehlkopfheikd 1968;192:100–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifert G, Sobin LH. Histological Typing of Salivary Gland Tumors: World Health Organization International Histological Classification of tumors. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag;1991

- 3.Yabuuchi H, Fukuya T, Tajima T, et al. Salivary gland tumors: diagnostic value of gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MR imaging with histopathologic correlation. Radiology 2003;226:345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen KT, Hafez GR. Infiltrating salivary duct carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of five cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1981;107:37–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen KT. Intraductal carcinoma of the minor salivary gland. J Laryngol Otol 1983;97:189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garland TA, Innes DJ Jr., Fechner RE. Salivary duct carcinoma: an analysis of four cases with review of literature. Am J Clin Pathol 1984;81:436–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui KK, Batsakis JG, Luna MA, et al. Salivary duct adenocarcinoma: a high grade malignancy. J Laryngol Otol 1986;100:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson C, Muller R, Piorkowski R, et al. Intraductal carcinoma of major salivary gland. Cancer 1992;69:609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afzelius LE, Cameron WR, Svensson C. Salivary duct carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Head Neck Surg 1987;9:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandwein MS, Jagirdar J, Patil J, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma (cribriform salivary carcinoma of excretory ducts): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Cancer 1990;65:2307–2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colmenero Ruiz C, Patron Romero M, Martin Perez M. Salivary duct carcinoma: a report of nine cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;51:641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado R, Vuitch F, Albores-Saavedra J. Salivary duct carcinoma. Cancer 1993;72:1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Barba E, Cortes-Guardiola JA, Minguela-Puras A, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical studies. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1997;25:328–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzzo M, Di Palma S, Grandi C, Molinari R. Salivary duct carcinoma: clinical characteristics and treatment strategies. Head Neck 1997;19:126–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsushima Y, Matsumoto M, Endo K. Parotid and parapharyngeal tumours: tissue characterization with dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Radiol 1994;67:342–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motoori K, Yamamoto S, Ueda T, et al. Inter- and intratumoral variability in magnetic resonance imaging of pleomorphic adenoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004;28:233–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsushima Y, Matsumoto M, Endo K, et al. Characteristic bright signal of parotid pleomorphic adenomas on T2-weighted MR images with pathological correlation. Clin Radiol 1994;49:485–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buadu LD, Murakami J, Murayama S, et al. Breast lesions: correlation of contrast medium enhancement patterns on MR images with histopathologic findings and tumor angiogenesis. Radiology 1996;200:639–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Takashima S, Takayama F, et al. Head and neck lesions: characterization with diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 2001;220:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Brekel MW, Stel HV, Castelijns JA, et al. Cervical lymph node metastasis: assessment of radiologic criteria. Radiology 1990;177:379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Som PM. Detection of metastasis in cervical lymph nodes: CT and MR criteria and differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;158:961–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]