Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is useful in diagnosing bacterial brain abscesses, but DWI features of fungal brain abscesses have not been characterized. Because fungal abscesses are not purulent, we hypothesized that their DWI characteristics are distinct from those of bacterial abscesses.

METHODS: We reviewed clinical, neuropathologic and neuroimaging findings of patients with fungal brain infections due to Aspergillus (n = 6), Rhizopus (n = 1), or Scedosporium (n = 1) species. DWI and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were obtained before definitive diagnosis and antifungal therapy. ADC ratios (lesion/contralateral white matter) were calculated.

RESULTS: Two patients had a rapidly progressive, fatal course, with cerebritis and acute inflammation; fungal organisms were largely restricted to vessels. Lesions were predominantly nonenhancing and had heterogeneous foci of restricted diffusion. Six patients with subacute neurologic presentations had acute or chronic inflammation, capsule formation, focal necrosis, and fungal organisms disseminated throughout the lesion. Their abscesses were ring enhancing. In five, lesions had restricted diffusion in the central nonenhancing portions. The sixth patient had a lesion with a peripheral rim of restricted diffusion but elevated central diffusion; histopathology showed early abscess formation. Mean ADC for all lesions was 0.33 ± 0.06 × 10−3 mm2/s, with an average ADC ratio of 0.43.

CONCLUSION: Fungal cerebral abscesses may have central restricted diffusion similar to that of bacterial abscesses but with histologic features of acute or chronic inflammation and necrosis rather than suppuration. Altered water diffusion in these lesions likely reflects highly proteinaceous fluid and cellular infiltration.

Cerebral abscess is a well-described condition in immunocompromised patients (1). Abscesses may be secondary to bacterial, fungal, or parasitic organisms. These lesions often produce complex clinical and radiologic findings and require prompt recognition and treatment to avoid a fatal neurologic outcome.

MR imaging is a sensitive and specific technique for the diagnosis of pyogenic bacterial abscess. Typical findings are a mass lesion with a thin, smooth rim of contrast enhancement, a variable degree of surrounding vasogenic edema, and markedly restricted diffusion of water in the central nonenhancing region (2). Abnormal diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) findings in pyogenic brain abscess have been attributed to restricted diffusion of water due to the high viscosity and cellularity of pus (2–4).

The features of nonpyogenic infectious lesions on DWI are less specific. For instance, abscesses due to Toxoplasma gondii have central necrosis without purulent material, and they do not demonstrate the prominent restricted diffusion seen with pyogenic abscesses (5). DWI characteristics of fungal abscesses have not been well characterized (6). Because fungal cerebral abscesses are not pyogenic, we hypothesized that these lesions do not have restricted diffusion in their central nonenhancing portion. The purpose of this study was to evaluate pretreatment DWI findings in eight patients with fungal brain abscess and to correlate these findings with clinical and histopathologic features.

Methods

Patients

We reviewed the medical records and neuroimaging studies of patients admitted with a proved diagnosis of fungal brain abscess between January 2000 and December 2003. Inclusion criteria included the performance of DWI before diagnosis (range, 1–28 days before diagnosis) and before antifungal treatment. We identified eight patients (four women, four men; mean age, 56 years; age range, 22–79 years). Histologic diagnosis was achieved by means of brain biopsy in four patients and autopsy in four. In seven patients, neuropathologic material was available for review and stained with routine hematoxylin-eosin. Fungal organisms were detected by using methenamine silver stain. The clinical course of each patient was reviewed. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

For a comparison group, we also identified five patients (two women, three men; mean age, 59.2 years; age range, 40–80 years) who were admitted between January 2000 and December 2003. This group had a proved diagnosis of bacterial brain abscess, and their neuroimaging studies were reviewed.

Imaging

MR imaging was performed by using a 1.5-T system (Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with echo-planar gradients. DWIs were obtained by using single-shot, echo-planar imaging with sampling of the entire diffusion tensor. Three to six high b value images corresponding to diffusion measurements in different gradient directions were acquired followed by a single b value image. The high b value was 1000 s/mm2, and the low b value was 0 s/mm2. Imaging parameters were a TR/TE/NEX of 7500–10,000/72–100/1–3, a FOV of 22 × 22 cm, an image matrix of 128 × 128 pixels, a section thickness of 5 mm with a 0–1 mm gap, and 23 axial sections. Isotropic DWIs were generated offline on a network workstation. ADC maps were also generated. This method has been described in detail (7).

The following sequences were also applied: (1) axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo, with a TR/effective TE/NEX of 4700–6000/102–108/1–2, FOV of 240 × 180 mm, matrix of 256 × 192, section thickness of 5 mm, and echo train length of 8–10; (2) axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), with a TR/TE/TI/NEX of 8000–9000/120/2,000–2200/1, FOV of 240 × 180 mm, matrix of 256 × 192, and section thickness of 5 mm; (3) axial T2*-weighted gradient-echo, with a TR/TE/NEX of 700–750/25–35/0.75–2, flip angle of 20°–30° FOV of 240 × 180 mm, matrix of 256 × 192, and section thickness of 5; and (4) T1-weighted images with a TR/TE/NEX of 400–625/14–17/0.5–1 and section thickness of 5 mm performed both before and after the intravenous administration of gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist; Berlex, Wayne, NJ) 0.1 mmol/kg.

Image Analysis

Regions of interest corresponding to areas of greatest visually decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) were manually outlined on ADC maps. In each patient, two or more regions of interests (0.10–0.60 cm2) were placed on a single section, and their values were averaged. ADC values were also obtained from equal regions of interest in normal contralateral white matter. ADC ratios were calculated as ADC of the lesion/ADC of the contralateral normal white matter. We similarly calculated the ADC values and ratios in the five patients with a proved diagnosis of bacterial cerebral abscess. ADC values and ratios for fungal and bacterial lesions were compared by using the Student t test with a P ≤ .05 level of significance.

Results

At the time of the diagnosis, all patients with fungal infection had underlying medical conditions known to be associated with immunosuppression. Five patients had hematologic malignancies (chronic lymphocytic leukemia in two, myelogenous leukemia in two, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in one). Two patients were receiving immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis in one, ulcerative colitis in one). One patient had HIV infection. All patients had neutropenia and lymphopenia. In five of eight patients, active pulmonary fungal infections were present at the time of diagnosis, whereas in three patients, the infection was isolated to the CNS.

Neurologic symptoms at onset were alteration in mental status and decreased cognitive function (n = 6), weakness (n = 3), fever (n = 2), headache (n = 2), and seizures (n = 1). Findings on neurologic examination were abnormal in all patients, and all patients were treated with glucocorticoids after initial MR imaging. Six patients received antifungal agents. Two patients did not receive antifungal therapy because they died soon after diagnosis. Five patients (63%) died from their brain abscesses (at 1, 2, 5, 15, or 28 days after diagnosis). Two patients were still alive and clinically stable at 1 and 11 months after diagnosis, and one patient died from bone marrow failure related to leukemia 4 years after diagnosis.

The presence of fungal organisms was histopathologically or microbiologically confirmed in each lesion (Table). All had classic histopathologic findings of fungal infection resulting in cerebritis or abscess and/or granuloma formation (8).

Clinical presentation and pathologic and DWI findings in patients with fungal cerebral infection or pyogenic bacterial abscess

| Patient | Clinical Presentation | Lesion Aspiration | Organism | MR Imaging Finding | ADC (×10−3 mm2/s) |

ADC Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | WM | ||||||

| 1 | Acute | Not done, autopsy | Rhizopus | Minimal enhancement, DWI heterogeneously hyperintense | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 2 | Acute | Not done, autopsy | Aspergillus | No enhancement, DWI heterogeneously hyperintense | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.27 |

| 3 | Subacute | Not done, autopsy | Aspergillus | Ring-enhancement, DWI peripherally hyperintense | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.19 |

| 4 | Subacute | Mucoid fluid | Aspergillus | Ring-enhancement, DWI centrally hyperintense | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.74 |

| 5 | Subacute | Not done, autopsy | Aspergillus | Ring-enhancement, DWI centrally hyperintense | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.81 |

| 6 | Subacute | Mucoid fluid | Aspergillus | Ring-enhancement, DWI centrally hyperintense | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.53 |

| 7 | Subacute | Mucoid fluid | Scedosporium | Ring-enhancement, DWI centrally hyperintense | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.39 |

| 8 | Subacute | Mucoid fluid | Aspergillus | Ring-enhancement, DWI hyperintense | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 0.31 |

Note.—Mean lesion and white matter ADC and ADC ratio were, respectively, 0.33 ± 0.06 × 10−3 mm2/s, 0.76 ± 0.05 × 10−3 mm2/s, and 0.43 in the fungal group and 0.46 ± 0.06 × 10−3 mm2/s (difference not significant), 0.76 ± 0.05 × 10−3 mm2/s, and 0.61 (difference not significant) in the bacterial group.

Fungal Cerebritis

In two patients with rapidly progressive neurologic dysfunction who died within 48 hours, review of their neuropathologic features at autopsy demonstrated fungal organisms predominantly restricted to the lumina of the vessels, an acute inflammatory response with perivascular polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), fibrinoid perivascular degeneration, focal necrosis, multifocal infarction, and an absence of capsule formation (Fig 1). These findings were consistent with cerebritis rather than well-formed abscesses. In these two patients, MR imaging showed large, predominantly nonenhancing lesions in the basal ganglia and deep white matter, as well as mild surrounding T2-weighted hyperintensity consistent with vasogenic edema (Fig 1). One patient had a single lesion, and the other had multiple lesions. DWI showed a heterogeneous pattern with regions of decreased and elevated diffusion (Fig 1).

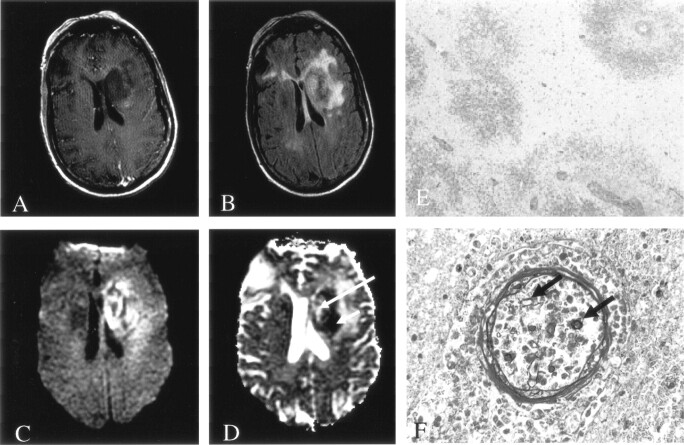

Fig 1.

Patient 1. Fungal cerebritis due to Rhizopus infection of the left basal ganglia and corona radiata.

A, On Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, the lesion is hypointense with minimal peripheral enhancement.

B, On FLAIR imaging, the lesion has heterogeneous signal intensity with moderate surrounding edema.

C and D, DWI (C) and ADC (D) images show predominantly decreased diffusion (short arrow in D) with a smaller region of elevated diffusion (long arrow in D).

E, Hematoxylin-eosin stain (40×) shows perivascular ring hemorrhages and necrosis. Moderate amount of acute and chronic inflammation was also found (data not shown).

F, Methenamine silver stain (450×) shows fungal organisms predominantly in the lumen of blood vessels (arrows).

Fungal Abscess

Six patients had a subacute neurologic presentation. At surgery, mucoid fluid was aspirated from a lesion in four cases. Histologic analysis revealed characteristic findings of cerebral abscess formation, with circumscribed lesions having central necrosis containing moderate amounts of acute (PMN) or chronic (lymphohistiocytic) inflammation. Fungal organisms were detected in the encapsulated lesion, but they were not commonly found in vessels or in the parenchyma outside the abscess. Histologic evidence showed capsule formation with chronic inflammation and granulation tissue. Two patients had granuloma formation with multinucleated giant cells. In some cases, small foci of hemorrhage or infarction adjacent to the abscess were noted. In one patient, histopathologic material was not available for review, but fungal stains of the mucoid aspirate revealed scant cellularity, rare PMNs, and fungal organisms with septate hyphae.

MR imaging demonstrated a single ring-enhancing lesion in two patients and multiple (two to eight) ring-enhancing lesions in four patients. Lesions were located at gray matter–white matter junctions and in the basal ganglia. In two patients, T2-weighted images showed substantial, surrounding hyperintensity in a pattern consistent with that of vasogenic edema (Fig 2); four patients had minimal vasogenic edema. We observed no evidence of prominent hemorrhage, focal infarction, or hydrocephalus in any patient.

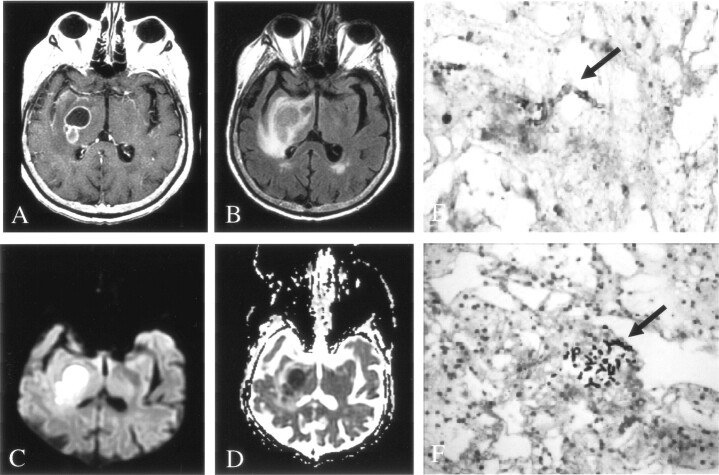

Fig 2.

Patient 7. Fungal abscess due to Scedosporium infection.

A, On Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, the lesion is ring enhancing.

B, On FLAIR imaging, the lesion is isointense to brain parenchyma, with moderate surrounding edema.

C and D, DWI (C) and ADC (D) images show homogeneously decreased diffusion in the center of the lesion, similar to that seen with pyogenic abscess.

E and F, Hematoxylin-eosin (E) (450×) and methenamine silver stain (F) (250×) stains show fungal organisms (arrow) in necrotic tissue and chronic inflammation.

On DWI, the lesions of five of six patients with fungal abscess had prominent central hyperintensity, and ADC maps showed hypointensity, consistent with restricted diffusion (Figs 2 and 3). In patient 3 (Table), whose lesion had not yet developed a well-defined capsule, DWI showed decreased diffusion along the periphery of the abscess but increased diffusion in the central portion (Fig 4).

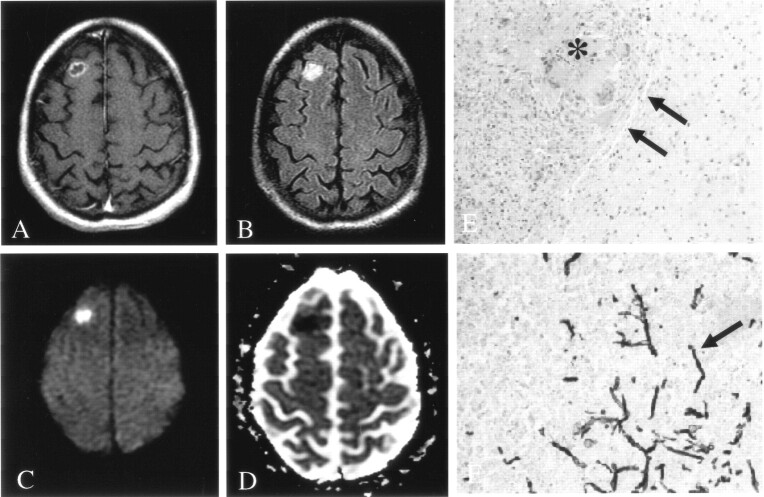

Fig 3.

Patient 6. Fungal abscess due to Aspergillus infection.

A, On Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, the lesion is ring enhancing.

B, On FLAIR imaging, the lesion is hyperintense to brain parenchyma, without surrounding edema.

C and D, DWI (C) and ADC (D) images show homogeneously decreased diffusion in the center of the lesion.

E, Hematoxylin-eosin stain (100×) shows a lesion discrete from brain with a well-defined capsule (arrows). Lesions were composed of granulomatous chronic inflammation with numerous histiocytes and giant cells engulfing fungal organisms (asterisk).

F, Methenamine silver stain (250×) shows fungal organisms (arrow) with 45° angle branching, consistent with Aspergillus infection.

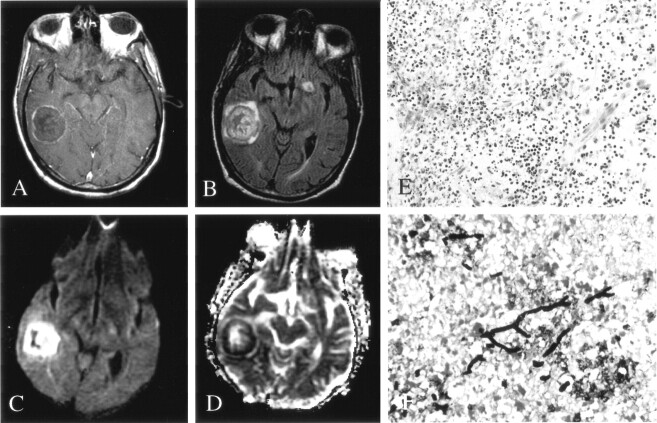

Fig 4.

Patient 3. Early fungal abscess due to Aspergillus infection.

A, On Gd-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, the lesion has a thin rim of peripheral enhancement.

B, On FLAIR imaging, the lesion has heterogeneous signal intensity with minimal surrounding edema.

C and D, DWI (C) and ADC (D) maps show peripherally decreased diffusion, with elevated diffusion in the center of the lesion.

E, Hematoxylin-eosin stain (100×) shows acute and chronic inflammation in the brain parenchyma, without a well-defined capsule.

F, Methenamine silver stain (250×) shows septate and 45°-branching hyphae in necrotic parenchyma.

The Table shows ADC values for patients with fungal infections. Three patients with fungal abscesses underwent follow-up MR imaging at least 1 month after diagnosis. The abscesses were stable or minimally decreased in size, and the surrounding T2-weighted hyperintensity had substantially decreased. No new lesions were seen. Restricted diffusion persisted in two patients and resolved in one.

Bacterial Abscess

In the comparison group of five patients with pyogenic bacterial abscesses, four had a single ring-enhancing lesion located at the gray matter–white matter junction (n = 3) or basal ganglia (n = 1). One patient had two ring-enhancing lesions at the gray matter–white matter junction. All lesions had notable surrounding T2-weighted hyperintensity in a pattern consistent with that of vasogenic edema. The bacterial abscesses had restricted diffusion (Table). These ADC values were not significantly different from those of fungal lesions.

Discussion

Diffusion imaging is helpful in the differential diagnosis of ring-enhancing brain lesions. Although exceptions exist, lesions such as neoplasms, subacute late ischemic infarctions, toxoplasmosis abscesses, and demyelinating plaques typically have elevated diffusion, whereas pyogenic bacterial abscesses typically have decreased diffusion in the central nonenhancing portion (9–12). Ebisu et al (2) were the first to recognize the usefulness of DWI in the diagnosis of brain abscesses. However, the DWI features of fungal abscesses have not been well characterized. Tung and Rogg (6) reported a single case of cerebral fungal cerebritis as a complication of frontoethmoid sinusitis. The ADC value in the central portion of the cerebritis was 0.56 × 10−3 mm2/s.

We examined the DWI characteristics of fungal abscesses and correlated these findings with the clinical and histopathologic features. In two patients with acute fungal cerebritis, lesions had little to no enhancement. Of note, their neurologic symptoms were more acute in onset (hours) than those of patients whose lesions showed enhancement (days). In addition, the two patients died shortly after the diagnosis was established. Both had received a bone marrow transplant (for myelogenous leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and had graft-versus-host disease. Their histologic findings at autopsy were characteristic of acute cerebritis and showed fungal organisms largely associated with vessels. Therefore, these patients appeared to have highly aggressive CNS infections with acute cerebritis that had not progressed to abscess formation. Consequently, the lesions did not show the characteristic ring enhancement (6). Areas of cellular infiltrate and multifocal infarction may have been responsible for the heterogeneous restricted diffusion seen in these lesions.

In six patients with fungal cerebral abscesses, ring enhancement was present, and five had centrally restricted diffusion in a pattern similar to that seen in pyogenic abscesses. The changes in diffusion likely reflected proteinaceous fluid and cellular infiltration in the lesions. The lesion in patient 3 had a peripheral rim of restricted diffusion with central region of elevated diffusion (Fig 4), and histopathology revealed that this lesion had not yet developed a well-defined capsule, consistent with early abscess formation. Although hemorrhage was not a prominent feature in any of the abscesses we studied, it is common in CNS infection caused by Aspergillus species, and it might have contributed to restricted diffusion in some cases.

In the two patients with acute fungal cerebritis, the initial neuroradiologic impression was infarction (n = 1) or lymphoma (n = 1). In six patients with abscesses, the neuroradiologic report suggested that an infectious process was more likely than tumor.

The fact that fungal abscesses produce ring-enhancing lesions with centrally restricted diffusion similar to that of bacterial abscesses has several implications. Antifungal agents should be added to the antibiotic regimen of immunosuppressed patients with these findings if biopsy results are pending or if biopsy is not possible. When lesion aspirate or tissue becomes available, the neuropathologist and microbiologist should be alerted to the possibility of fungal infection in addition to bacterial infection. Furthermore, clinicians should seek evidence of a coexisting systemic fungal infection, as this was present in five of our eight patients. Our findings also suggest that highly virulent fungal cerebritis should be considered in the presence of nonenhancing mass lesion in immunocompromised patients with acute-onset neurologic symptoms and signs; these patients should be treated aggressively.

Conclusion

Fungal cerebral abscesses have decreased diffusion, similar to pyogenic abscesses. Fungal cerebral abscesses should be included in the differential diagnosis of ring-enhancing lesions with centrally restricted diffusion, especially in immunocompromised patients, and also in the differential diagnosis of predominantly nonenhancing lesions with decreased diffusion in immunocompromised patients.

Footnotes

Supported by the Stephen E. and Catherine Pappas Brain Tumor Imaging Research program.

References

- 1.Guppy KH, Thomas C, Thoma K, Anderson D. Cerebral fungal infections in the immunocompromised host: a literature review and a new pathogen—Chaetomium atrobrunneum: case report. Neurosurgery 1992;43:1463–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebisu T, Tanaka C, Umeda M, et al. Discrimination of brain abscess from necrotic or cystic tumors by diffusion-weighted echo planar imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 1996;14:1113–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leuthardt EC, Wippold FJ II, Oswood MC, Rich KM. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the preoperative assessment of brain abscesses. Surg Neurol 2002;58:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rana S, Albayram S, Lin DD, Yousem DM. Diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient maps in a case of intracerebral abscess with ventricular extension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:109–112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong-Han CH, Cortez SC, Tung GA. Diffusion-weighted MRI of cerebral Toxoplasma abscess. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1711–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tung GA, Rogg JM. Diffusion-weighted imaging of cerebritis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:1110–1113 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorensen AG, Buonanno FS, Gonzalez RG, Schwamm LH, Lev MH, Huang-Hellinger FR. Hyperacute stroke: evaluation with combined multisection diffusion-weighted and hemodynamically weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 1996;199:391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DI, Lantos PL. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. London: Hodder Arnold;2001. :107–150

- 9.Schaefer PW, Grant PE, Gonzalez RG. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the brain. Radiology 2000;217:331–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desprechins B, Stadnik T, Koerts G, Shabana W, Breucq C, Osteaux M. Use of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in differential diagnosis between intracerebral necrotic tumors and cerebral abscesses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1252–1257 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman R, Barth A, Lovblad KO, et al. Use of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating purulent brain processes from cystic brain tumors. J Neurosurg 2002;97:1101–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann M, Jansen O, Heiland S, Sommer C, Munkel K, Sartor K. Restricted diffusion within ring enhancement is not pathognomonic for brain abscess. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:1738–1742 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]