Abstract

Husk and pellicle as the agri-food waste in the walnut-product industry are in soaring demand because of their rich polyphenol content. This study investigated the differential compounds related to walnut polyphenol between husk and pellicle during fruit development stage. By using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole-orbitrap (UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap), a total of 110 bioactive components, including hydrolysable tannins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and quinones, were tentatively identified, 33 of which were different between husk and pellicle. The trend of dynamic content of 16 polyphenols was clarified during walnut development stage by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This is the first time to comprehensive identification of phenolic compounds in walnut husk and pellicle, and our results indicated that the pellicle is a rich resource of polyphenols. The dynamic trend of some polyphenols was consistent with total phenols. The comprehensive characterization of walnut polyphenol and quantification of main phenolic compounds will be beneficial for understanding the potential application value of walnut and for exploiting its metabolism pathway.

Keywords: polyphenol, identification, quantification analysis, metabolic regulation

1. Introduction

Walnut (Juglans regia L.) is a high nutritional nut due to the rich contents of unsaturated fatty acids, melatonin, vitamins, polyphenols and so on [1,2]. Among which, polyphenols are considered as to be important bioactive substance [2]. In addition, walnuts were also popular around the world for their health-promoting properties, such as reducing the risk of heart disease and cancer, improving blood circulation and reducing oxidative stress and inflammation [3,4,5]. Nowadays, walnut kernel is usually processed into various food; however, walnut husk and pellicle were usually directly discarded as waste or fuel, which caused resource waste and environmental pollution. Although walnut husk contained rich polyphenols [6], walnuts are mainly cultivated in order to obtain the kernels, and other parts of the nut, such as the shell and husk, are produced as waste during the fruit harvesting and processing [7,8]. Walnut pellicle only accounts for 5–8% of the whole walnut kernel [9] and is also the main source of walnut polyphenols, which could cause slight astringency and bitterness [10]; it is removed in the food processing, resulting in a waste of resources. At present, the research and development of agricultural waste with potential application value has been popularized and valued all over the world.

Walnut polyphenols contains phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannin and quinones [11]. Polyphenols exhibit a variety of activities, were the main compounds of walnut, which are important for human health [12]. However, there has been neither a systematic description of the chemical compound species nor a comprehensive comparison of the difference that exists in the polyphenol metabolites between the husk and pellicle of the walnut; the dynamic trend of the main compounds in the walnut polyphenol metabolism is especially unclear. Q-Orbitrap enables fast, sensitive and reliable detection and identification of small molecules without considering the relative ion abundance; it also has an extremely fast scanning speed, and the front body ions and product ions provide high-quality measurement results [11]. In addition, HPLC can be used for quick and accurate quantification the identification components, which has become one of the most economical technology [13]. Therefore, in order to explore the application value and main metabolites of the material, it is necessary to combine the new technology to comprehensively identify the polyphenol components in the husk and pellicle of the walnut.

In this study, Q-Orbitrap and HPLC were used for the systematic characterization and accurate quantification of the compounds in walnut husk and pellicle. Systematic characterization and quantification of polyphenol offers a comprehensive understanding of the potential application value of the walnut to improve recycling and help to explain its metabolism pathway.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Changes of Phenols and Flavonoid Content of Walnut Husk and Pellicle

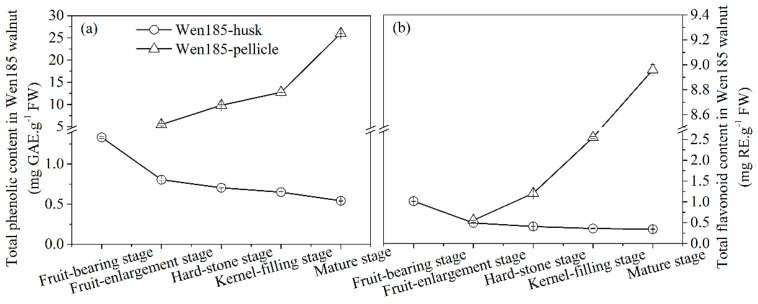

The walnut husk and pellicle are a rich source of phenolic and flavonoid compounds [1]. In order to explore the change relationship between the total phenols (TPC) and total flavonoids (TFC) and the important polyphenol components, TPC and TFC were measured. TPC and TFC decreased continuously from fruit-bearing stage to mature stage in walnut husk but increased in pellicle (Figure 1). During the mature process, the range of TPC and TFC was 0.54–1.33 mg gallic acid equivalent/g fresh weight (GAE/g FW) and 0.34–1.01 mg rutin equivalent/g (RE/g) FW in walnut husk, respectively, which was similar to the results of Shi et al. [14]. For pellicle, the pellicle area increased gradually, but its weight gradually lightened with the growth cycle close to the mature stage; therefore, the accumulation of TPC and TFC showed an upward trend. The highest TPC and TFC was 26.02 mg GAE/g FW and 8.95 mg RE/g FW in walnut pellicle, respectively, compared with the phenolic contents in walnut reported in previous studies, such as leaf (0.34 mg GAE/g FW) [15], kernel (1.76 mg GAE/g FW) [16], shell (0.10 mg GAE/g FW) [16] and husk (1.14 mg GAE/g FW) [14], indicating that the pellicle was an abundant source of polyphenols.

Figure 1.

Changes of total phenol (a) and flavonoid (b) contents of walnut husk and pellicle.

2.2. Characterization of Phenolic Components in Walnut Husk and Pellicle

In this study, the UPLC system coupled with Q-Orbitrap system was used to analyze the phenolic compounds in husk and pellicle of the walnut, and a highly complex mixture of hydrolysable tannins, flavonoids and phenolic acids was contained. Moreover 110 compounds were successfully identified. Information on all compounds is listed in Table 1. Part of these compounds was reported in walnuts for the first time.

Table 1.

Characterization of the components from walnut extracts by UHPLC–Q-Orbitrap HRMS.

| No. | RT (min) |

Formula | Ion Mode | Measured Mass (m/z) | MS/MS Fragments (m/z) |

Error (ppm) | Compound Identification | Reference | Classification | Walnut | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husk | Pellicle | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.744 | C20H18O14 | M−H | 481.06317 | 301.000, 275.020, 229.014, 257.010 | 1.666 | HHDP-glucose isomer | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 2 | 0.895 | C7H12O6 | M−H | 191.05539 | 85.028, 93.033, 87.008, 59.013, 173.045 | −3.772 | quinic acid | [17] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | + |

| 3 | 1.162 | C13H16O10 | M−H | 331.06760 | 169.014, 271.046, 211.025, 125.023 | 1.620 | monogalloyl-glucose isomer | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | + |

| 4 | 1.307 | C7H6O5 | M−H | 169.01352 | 125.023, 107.013 | −4.264 | gallic acid | [11] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 5 | 1.361 | C8H8O4 | M−H | 167.03427 | 123.044, 139.003 | −4.243 | hydroxymandelic acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 6 | 2.073 | C13H16O10 | M−H | 331.06760 | 169.014, 125.023, 271.046, 211.025 | 1.620 | gallic acid hexoside | [19] | Phenolic Acid | − | + |

| 7 | 2.699 | C13H16O9 | M−H | 315.07281 | 108.021, 152.011 | 2.110 | protocatechuic acid-O-hexoside | [20] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 8 | 3.749 | C8H8O4 | M+H | 169.04951 | 111.044, 65.039, 125.060, 169.050, 151.039, 93.034 | −3.284 | isovanillic acid | Phenolic Acid | + | + | |

| 9 | 3.786 | C7H6O3 | M−H | 137.02347 | 108.021, 93.033 | −2.861 | protocatechualdehyde | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | − |

| 10 | 3.971 | C16H18O9 | M−H | 353.08832 | 191.056, 135.044, 179.034 | 1.467 | neochlorogenic acid | [11] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 11 | 4.090 | C9H6O3 | M+H | 163.03888 | 163.039, 107.049, 95.050 | −3.377 | 7-hydroxycoumarine | Other | + | + | |

| 12 | 4.102 | C14H18O10 | M−H | 345.08307 | 168.006, 124.016 | 1.040 | methyl galloyl hexoside | [18] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | + |

| 13 | 4.171 | C7H6O4 | M−H | 153.01846 | 109.028, 81.033 | −5.665 | protocatehuic acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 14 | 4.270 | C15H20O10 | M−H | 359.09897 | 197.045, 153.055 | 1.667 | dimethyl galloyl hexoside | [18] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | + |

| 15 | 4.447 | C15H18O9 | M−H | 341.08826 | 177.055, 135.044 | 1.662 | caffeic acid hexoside II | [21] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 16 | 4.448 | C8H8O5 | M−H | 183.02930 | 168.006, 124.016 | −3.240 | methyl gallate | [19] | Other | + | + |

| 17 | 4.470 | C13H15O8 | M−H | 299.07767 | 137.024 | 1.872 | hydroxybenzoyl hexoside | [20] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 18 | 4.485 | C30H26O12 | M−H | 577.13678 | 125.024, 289.072, 407.078, 425.089, 109.029, 137.024 | 2.841 | B-type procyanidin dimer isomer | [11] | Flavonoid | − | + |

| 19 | 4.814 | C21H22O12 | M−H | 465.10535 | 303.051, 285.039, 201.113 | 3.239 | epicatechin-3-O-glucoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 20 | 4.911 | C7H6O3 | M−H | 137.02348 | 93.033, 108.021, 137.024 | −6.763 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | [19] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 21 | 4.912 | C15H14O6 | M−H | 289.07224 | 109.029, 245.082, 123.044, 125.024, 203.071, 137.024, 151.039, 205.050, 97.028 | 1.644 | (+)-catechin | [11] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 22 | 4.930 | C14H10O9 | M−H | 321.02539 | 169.014, 125.024 | 0.594 | m-digallate | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 23 | 4.930 | C10H6O3 | M−H | 173.02376 | 173.024, 145.029, 117.034 | 3.225 | 2-hydroxy-1, 4-naphthoquinone | Quinones | + | + | |

| 24 | 5.099 | C20H20O14 | M−H | 483.07886 | 169.014, 125.024, 271.047, 211.025, 313.057, 331.068 | 1.733 | digalloyl-glucose isomer | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 25 | 5.102 | C8H8O4 | M−H | 167.03427 | 152.011, 108.021, 123.044 | −4.243 | vanillic acid | [17] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 26 | 5.175 | C16H18O8 | M−H | 337.09344 | 163.039, 119.049, 173.045, 93.033 | 1.646 | 3-p-coumaroylquinic acid | [11] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 27 | 5.199 | C45H38O18 | M−H | 865.19952 | 125.024, 289.072, 407.078, 151.039 | 1.149 | B-type procyanidin trimer isomer | [11] | Flavonoid | − | + |

| 28 | 5.266 | C10H10O3 | M+H | 179.07021 | 133.065, 147.044 | −0.415 | juglanoside isomer | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 29 | 5.352 | C60H50O24 | M−2H | 576.12830 | 289.072, 287.057, 407.079 | 2.171 | B-type procyanidin tetramer isomer | [11] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 30 | 5.452 | C9H8O4 | M−H | 179.03435 | 135.044, 107.049 | −3.533 | caffeic acid | [17] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 31 | 5.473 | C27H22O18 | M−H | 633.07495 | 301.000, 275.020, 125.023, 229.014, 257.010 | 2.561 | galloyl-HHDP-glucose | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 32 | 5.701 | C9H10O5 | M−H | 197.04512 | 182.022, 123.008, 166.998, 153.055, 138.031 | −2.130 | syringic acid | [17] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 33 | 5.777 | C41H28O26 | M−H | 935.08185 | 275.020, 301.000, 229.014, 257.010, 299.020 | 2.500 | galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose | [18] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | − |

| 34 | 5.887 | C15H22O5 | M−H | 281.13980 | 237.150, 171.118, 123.080, 189.129 | 1.284 | dihydrophaseic acid | [18] | Other | + | + |

| 35 | 5.927 | C10H10O3 | M−H | 177.05504 | 177.055, 159.044, 149.060, 131.049 | −3.793 | isosclerone isomer | [18] | Other | + | + |

| 36 | 5.951 | C10H8O3 | M+H | 177.05447 | 177.055, 149.060, 131.049, 121.065, 159.044 | −3.977 | 5-hydroxy-1, 4-naphthaoquinon | [22] | Quinones | + | + |

| 37 | 5.961 | C16H18O9 | M−H | 353.08832 | 135.044, 179.034, 191.056 | 1.467 | chlorogenic acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 38 | 6.177 | C15H18O8 | M−H | 325.09341 | 265.072, 119.049, 163.039, 205.050, 235.061, 145.029 | 1.613 | coumaric acid hexoside isomer | [11] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 39 | 6.185 | C10H10O2 | M+H | 163.07530 | 131.049, 103.055, 163.075 | −3.421 | methyl cinnamate | Phenolic Acid | + | + | |

| 40 | 6.205 | C11H12O5 | M+H | 225.07591 | 175.039, 91.055, 119.049, 147.044, 207.101 | −2.477 | sinapinic acid | Phenolic Acid | + | + | |

| 41 | 6.342 | C15H14O6 | M−H | 289.07224 | 109.029, 245.082, 123.044, 125.024, 203.071, 137.024, 151.039 | 1.644 | (−)-epicatechin | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 42 | 6.344 | C8H8O3 | M−H | 151.03922 | 136.016, 108.021, 123.045 | −5.594 | vanillin | [18] | Other | + | + |

| 43 | 6.387 | C21H22O13 | M−H | 481.09924 | 169.014, 125.024, 300.999 | 1.004 | galloyl methylgalloyl dexoyhexoside isomer | [18] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 44 | 6.400 | C16H18O8 | M+H | 339.10748 | 177.055, 145.028, 321.097, 117.034 | 0.097 | trihydroxynaphthaline glucoside | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 45 | 6.510 | C40H28O25 | M−H | 907.08575 | 301.000, 275.020, 783.070 | 1.769 | heterophylliin E isomer | [23] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 46 | 6.546 | C10H6O3 | M+H | 175.07520 | 119.086, 147.080, 129.070 | −2.280 | juglone | [22] | Quinones | + | + |

| 47 | 6.571 | C14H18O9 | M−H | 329.08835 | 167.034, 123.044 | 3.307 | vanillic acid hexoside | Phenolic Acid | + | + | |

| 48 | 6.743 | C21H10O13 | M−H | 469.00540 | 425.016, 301.000 | 1.155 | valoneic acid dilactone | [23] | Other | − | + |

| 49 | 6.854 | C10H8O3 | M−H | 175.03929 | 147.044, 131.049 | −4.391 | 7-hydroxy-methylcoumarin | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | − |

| 50 | 6.920 | C21H22O12 | M−H | 465.10403 | 285.041 | 0.418 | quercetin-3-O-galactopyranoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 51 | 6.953 | C20H16O13 | M−H | 463.05298 | 300.999, 301.072 | 3.729 | ellagic acid hexoside isomer | [11] | Phenolic Acid | − | + |

| 52 | 7.085 | C9H10O4 | M−H | 181.05002 | 166.027, 151.003, 123.008 | −3.379 | syringaldehyde | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 53 | 7.103 | C41H28O27 | M−H | 951.07581 | 301.000, 275.020, 783.071, 299.992, 229.014, 257.010, 907.087 | 1.362 | trigalloyl-HHDP-glucose | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 54 | 7.135 | C9H8O3 | M−H | 163.03932 | 119.049, 93.033 | −4.527 | o-coumaric acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 55 | 7.299 | C27H22O19 | M−H | 649.06903 | 300.999 | 1.203 | valoneoyl-glucose | [19] | Hydrolysable Tannins | + | + |

| 56 | 7.384 | C22H18O10 | M−H | 441.08365 | 289.072, 109.029, 245.082, 125.024, 203.071, 151.039, 205.050 | 2.128 | (−)-epicatechin 3-O-gallate | [11] | Flavonoid | − | + |

| 57 | 7.460 | C27H24O18 | M−H | 635.09070 | 169.014, 125.024, 483.079, 313.057, 465.068, 211.025 | 2.705 | trigalloyl-glucose isomer | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 58 | 7.527 | C19H14O12 | M−H | 433.04199 | 299.992, 301.000, 229.014 | 1.737 | ellagic acid pentoside isomer | [11] | Phenolic Acid | − | + |

| 59 | 7.547 | C34H26O22 | M−H | 785.08685 | 301.000, 275.020, 229.014, 125.023, 257.010, 169.014 | 3.265 | digalloyl-HHDP-glucose | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 60 | 7.696 | C21H20O13 | M−H | 479.08334 | 316.023, 317.031 | 0.487 | myricetin-O-hexoside | [20] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 61 | 7.802 | C21H20O13 | M+H | 481.09705 | 319.045, 153.018, 85.029, 91.039 | −1.152 | myricetin-3-O-beta-D-galactopyranoside | [22] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 62 | 7.835 | C20H20O11 | M−H | 435.09390 | 151.003, 285.041, 107.013 | 1.431 | taxifolin-3-O-arabinofuranoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | − |

| 63 | 7.874 | C9H10O3 | M+H | 167.07022 | 167.070, 123.044, 149.096, 121.029 | −3.286 | ethyl paraben | Phenolic Acid | + | + | |

| 64 | 7.878 | C9H10O3 | M−H | 165.05498 | 121.029, 108.021 | −4.438 | hydroxyphenyl-propionic acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 65 | 8.121 | C28H24O16 | M−H | 615.10004 | 300.028, 301.036, 271.025, 169.014, 125.024 | 1.441 | quercetin galloyl hexoside isomer | [11] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 66 | 8.140 | C34H24O22 | M−H | 783.07117 | 301.000, 275.020, 229.014, 257.009 | 3.227 | pedunculagin/casuariin isomer (bis-HHDP-glucose) | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 67 | 8.298 | C14H6O8 | M−H | 300.99945 | 229.015, 283.997, 257.010, 185.024 | 1.531 | ellagic acid | [11] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 68 | 8.320 | C15H12O7 | M−H | 303.05136 | 125.024, 285.041, 177.019 | 1.980 | taxifolin isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | − |

| 69 | 8.356 | C10H10O4 | M−H | 193.05016 | 175.039, 147.044, 178.027, 131.049 | −2.457 | ferulic acid | [18] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 70 | 8.429 | C9H8O3 | M−H | 163.03925 | 119.049, 93.033 | −4.995 | p-coumaric acid | [17] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 71 | 8.502 | C21H18O13 | M−H | 477.06006 | 299.992, 315.016 | 1.150 | methyl ellagic acid hexoside | [19] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 72 | 8.704 | C10H8O2 | M+H | 161.05965 | 133.065, 105.070, 115.054, 91.055 | −0.394 | naphthalened iol isomer | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 73 | 8.718 | C34H28O22 | M−H | 787.10297 | 169.014, 125.024, 617.080, 465.069, 313.057 | 3.845 | tetragalloyl-glucose isomer | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 74 | 8.779 | C21H20O12 | M−H | 463.08939 | 271.025, 151.003, 178.998 | 3.764 | myricitrin | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 75 | 9.040 | C21H22O11 | M−H | 449.10910 | 151.003, 285.041, 125.023, 107.013, 303.051, 178.998 | 0.379 | astilbin isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 76 | 9.116 | C15H10O6 | M+H | 287.05499 | 287.055, 213.055, 153.018, 121.029, 241.050 | −1.973 | kaempferol | [22] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 77 | 9.153 | C15H10O6 | M−H | 285.04068 | 175.039, 133.029, 151.003 | 0.772 | luteolin | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 78 | 9.235 | C41H30O26 | M−H | 937.09729 | 301.000, 257.010, 635.090, 785.086 | 2.754 | tellimagrandin II | [11] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 79 | 9.630 | C20H18O11 | M−H | 433.07828 | 300.028, 301.036, 271.025, 151.003 | 2.788 | quercetin pentoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | − |

| 80 | 9.679 | C20H16O12 | M−H | 447.05780 | 315.015 | 1.231 | methyl ellagic acid pentose | [19] | Phenolic Acid | − | + |

| 81 | 9.742 | C23H22O12 | M−H | 489.10464 | 175.039, 169.014, 271.047, 125.023, 313.057, 229.051 | 1.645 | 3’-O-acetylquercitrin isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 82 | 9.844 | C23H22O12 | M+H | 491.11835 | 153.018, 201.054, 297.060 | −0.128 | trihydroxynaphthalene-O-(O-trihydroxybenzoyl) glucoside | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 83 | 9.910 | C21H20O11 | M−H | 447.09402 | 300.028, 301.036, 271.025, 255.030, 151.003, 243.030, 178.998 | 1.666 | quercitrin | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 84 | 9.960 | C21H22O10 | M−H | 433.11514 | 271.062, 151.003, 119.049, 177.019 | 3.846 | naringenin-7-O-glucoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 85 | 10.131 | C48H32O31 | M−2H | 551.03961 | 301.000, 169.014, 125.023, 275.020 | 1.437 | calamanin A isomer | [18] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 86 | 10.167 | C9H16O4 | M−H | 187.09717 | 125.096, 97.065, 168.888 | −2.202 | azelaic acid | [18] | Other | + | − |

| 87 | 10.239 | C22H22O12 | M−H | 477.10464 | 169.014, 125.024 | 1.687 | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | − |

| 88 | 10.423 | C21H22O11 | M−H | 449.10995 | 287.057 | 2.282 | eriodictyol-O-hexoside | [20] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 89 | 10.526 | C26H18O16 | M−H | 585.05341 | 301.000, 433.040 | 2.061 | ellagic acid galloyl pentose | [19] | Hydrolysable Tannins | − | + |

| 90 | 10.676 | C28H24O14 | M−H | 583.11023 | 300.028, 271.025, 255.030, 301.035, 151.003 | 1.560 | quercetin-O-(p-hydroxy)benzoyl-hexoside | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 91 | 10.904 | C21H20O12 | M−H | 463.08951 | 301.036, 151.003, 178.998 | 2.846 | quercetin-O-glucoside | [20] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 92 | 10.909 | C25H26O12 | M−H | 517.13623 | 175.039 | 2.109 | dihydroxynaphthol-O-[O-(dimethoxy-hydroxybenzoyl)] glucopyranoside | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 93 | 11.014 | C23H20O12 | M+H | 489.10269 | 327.050, 265.049, 237.055, 309.039 | −0.140 | jugnaphthalenoside A | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 94 | 11.015 | C20H16O11 | M−H | 431.09912 | 285.041, 255.030, 284.033, 227.035 | 1.742 | kaempferol-rhamnoside | [11] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 95 | 11.085 | C37H30O16 | M−H | 729.14972 | 125.023, 169.014, 407.078, 289.072 | 4.964 | (epi)catechin-(4,8’)-3’-O-galloyl-(epi)catechin | [18] | Flavonoid | − | + |

| 96 | 11.231 | C16H20O9 | M−H | 355.10428 | 175.040, 134.036, 160.016 | 2.333 | juglanoside D isomer | [18] | Quinones | + | + |

| 97 | 11.312 | C28H35NO13 | M−H | 592.20520 | 241.108, 403.162, 343.140 | 3.741 | glansreginin A | [23] | Other | − | + |

| 98 | 11.812 | C15H12O6 | M−H | 287.05640 | 135.044, 151.003 | 0.998 | eriodictyol | [20] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 99 | 11.813 | C21H24O10 | M−H | 435.13080 | 167.034, 125.023, 123.044, 273.078, 119.049 | 2.593 | phlorizin | [18] | Other | + | + |

| 100 | 12.186 | C15H20O10 | M−H | 359.09894 | 197.045 | 1.582 | syringic acid hexoside | [24] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 101 | 12.229 | C15H10O7 | M−H | 301.03577 | 151.003, 107.013, 178.998 | 1.317 | quercetin | [23] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 102 | 13.474 | C15H12O5 | M−H | 271.06180 | 93.033, 177.019, 119.049, 107.013, 151.003 | 2.243 | naringenin | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 103 | 14.008 | C15H14O5 | M−H | 273.07748 | 151.003, 189.055, 125.024, 167.034, 123.044, 119.049 | 2.359 | phloretin | [18] | Other | + | + |

| 104 | 14.024 | C9H10O2 | M−H | 149.05992 | 149.009, 105.070 | 3.698 | hydrocinnamic acid | Other | + | + | |

| 105 | 14.582 | C10H12O | M+H | 149.09618 | 149.096, 105.070, 79.055, 65.039 | −3.715 | cuminaldehyde | Other | − | + | |

| 106 | 14.630 | C16H12O6 | M−H | 299.05661 | 256.039, 227.035, 284.033 | 1.672 | kaempferide isomer | [18] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 107 | 17.493 | C20H20O7 | M+H | 373.12814 | 343.081, 183.029, 271.059, 297.075 | −1.492 | tangeritin | Flavonoid | + | + | |

| 108 | 20.835 | C13H11O9 | M−H | 311.25992 | 149.096 | 2.436 | caftaric acid | [20] | Phenolic Acid | + | + |

| 109 | 21.734 | C27H30O16 | M−H | 609.51074 | 255.233, 271.047 | 1.936 | rutin | [17] | Flavonoid | + | + |

| 110 | 23.493 | C10H6O4 | M−H | 189.01877 | 161.024, 117.034 | −2.972 | dihydroxy-naphthoquinone isomer | [18] | Quinones | + | − |

Note: A plus sign (+) and a minus sign (−) represent the presence or absence of the data in walnut husk or pellicle at the corresponding level, respectively.

2.2.1. Hydrolysable Tannins and Related Compounds

The ellagitannins (ET) contain the hexahydroxydiphenoyl (HHDP) group and monosaccharide [25], which were released on acid hydrolysis and spontaneously lactonized to ellagic acid (EA). The free EA was confirmed by [M−H]− ion at m/z 300.99 (peak 67), and the fragment ions were confirmed at m/z 257.01 [M−H−CO2]−, m/z 229.02 [M−H−CO2−CO]− and m/z 185.02 [M−H−2CO2−CO]− [11]. In addition to EA, several monoglycosylated EA derivatives were observed in walnuts, such as EA pentoside (m/z 433.04, peak 58) (Supplementary Materials Figure S1) and EA hexaglucoside (m/z 463.05, peak 51). The ions at m/z 481.06, m/z 783.07 (peaks 1; 66), m/z 907.09 and m/z 951.08 (peaks 45; 53) were detected and identified as the hexahydroxydiphenolic acid (HHDP) glucose isomer, their intense fragment ion at m/z 301 [M−H−C6H12O6]− indicated the loss of a glucose and the existence of an ellagic acid group, which has been reported as the main ET in walnuts [11]. The similar methyl ellagic acid derivatives can be identified by characteristic fragment ions at m/z 315.02 including methyl ellagic acid, for example methyl ellagic acid hexoside (m/z 477.06, peak 71), methyl ellagic acid pentose (m/z 447.06, peak 80).

A large number of gallotannins also presented in the extracts, ellagitannins were metabolically derived from gallotannins, mainly through C-C oxidative coupling of galloyl groups of pentagalloyl-glucose [23]. The characteristic of galloyl-glucose fragmentation was the generation of ion fragments by the continuous loss of gallic acid (170 Da) and galloyl (152 Da) [11]. The existence of [M−H]− in 331.07, 483.08, 635.09 (Supplementary Materials Figure S2) and 787.10 indicated the presence of mono-, di-, tri- and tetra-galloyl glucose (peaks 3, 24, 57, 73, etc.), respectively. Several isomeric forms of these gallic acid esters of glucose with different retention times were found in our samples. Three or four galloyl acyl glucose also have found in walnut kernels and septum [11,17].

2.2.2. Flavonoids

(+)-Catechin was identified as the main flavan-3-ol with [M−H]− ion at m/z 289.07 and mass spectra/mass spectra (MS/MS) fragments at m/z 245.08, 205.05 and 123.04, which were consistent with the results reported by Gómez-Caravaca et al. [26]. Moreover, (−)-epicatechin (peak 41) shared the same molecular ion with catechin. The [M−H]− ion (peak 56) at m/z 441.08 with the fragment ions of m/z 289.07, which was generated due to the breaking of the ester bond, was tentatively identified as (−)-epicatechin gallate isomer (Supplementary Materials Figure S3). It was also found in walnut kernel [17]. Procyanidins were polymers of catechin and epicatechin, with the oligomeric procyanidin monomers linking mainly through C4→C8 or C4→C6 bonds [19]. In this study, four kinds of oligomers of procyanidins were detected, with degree of polymerization (DP) from 2 to 4, and all belonged to type B. The [M−H]− ion of procyanidin dimer (18) and trimer (27) were at m/z 577.14 and 865.20 [11], respectively. The [M−2H]2− ion of procyanidin tetramer (peak 29) at m/z 576.13 was observed (Supplementary Materials Figure S4). It has been reported that procyanidins with DP from 4 to 6 in walnut kernel [23], however, more species of oligomeric procyanidins were found in this study.

Flavonol has been concerned for its free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory activities and its ability to resist to cardiovascular disease [27,28]. The peak 65 was detected at m/z 615.09, with its fragments at m/z 463.13 (M−H−152, loss of galloyl group) and m/z 301.00 (M−H−162, loss of hexosyl group). It was tentatively identified as quercetin galloyl-hexoside [11]. Peak 79 at m/z 433.08, including the 301.00 fragment (M−H−132, loss of pentose unit), was identified as quercetin pentoside (Supplementary Materials Figure S5). Peak 91 at m/z 463.09 produced a fragment ion at m/z 301.03 (M−H−162, loss of hexoside moiety), and 300.02 (H rearrangement) was identified as quercetin-O-glucoside [20]. Myricetin-O-hexoside (m/z 479.08, peak 60) showed fragment ions at m/z 317.03 and 316.02, corresponding to the loss of a hexoside moiety (−162 Da). Peak 94 was identified as kaempferol-rhamnoside, with fragments at m/z 285.04 and [M−H]− ion at m/z 431.10, and it was also detected in the walnut septum [11].

Flavanol, also known as dihydroflavonol, is a subclass of polyphenols that is negatively related to diabetes in animal and in vitro models. Taxifolin (m/z 303.05, peak 68) showed fragment ions at m/z 285.04, 177.02 and 125.02; the ion at m/z 285 was due to the loss of a water molecule (−18 Da), whereas, at m/z 177 and 125, the ions correspond to cleavage of the C ring [18] (Supplementary Materials Figure S6). The astilbin (m/z 449.11, peak 75) was preliminarily identified; the MS2 spectrum of m/z 449.11 produced ions at m/z 303.05, 285.04 and 151.00, and those at m/z 303 and 285 were generated by the loss of a rhamnose (−146 Da) and consecutive loss of a water molecule (−18 Da) [18], which has been identified in grapes and was identified in walnuts for the first time.

Eriodictyol and its glycoside derivatives are the main flavanones in the walnut husk and pellicle. Eriodictyol (m/z 287.06, peak 98) showed products at m/z 151.00 and 135.04 formed by an retro diels-alder (RDA) type fragmentation in the C ring. The MS2 spectrum of eriodictyol-O-hexoside (m/z 449.11, peak 88) produced ions at m/z 287.06 generated by the loss of a hexosyl moiety (−162 Da); this is the first report of eriodictyol-O-hexoside in walnuts.

2.2.3. Phenolic Acid and Derivatives

Phenolic acid and its derivatives are easy to cleavage CO2 from carboxylic acid [11]. The neutral loss of CO2 was observed in MS/MS data of gallic acid (m/z 169.01, peak 4), protocatechuic acid (m/z 153.02, peak13), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (m/z 137.02, peak 20), vanillic acid (m/z 167.03, peak 25), caffeic acid (m/z 179.03, peak 30), syringic acid (m/z 197.04, peak 32) and p-coumaric acid (m/z 163.03, peak 70). The peak 10 was detected at m/z 353.09 with its fragments at m/z 191.06 and 179.03, which can be identified as caffeoylquinic acids (neochlorogenic acid). The [M−H]− ion at m/z 337.09 (peak 26) generated fragments ion at m/z 163.04, m/z 173.05, 119.05 and 93.03, which was corresponding to the loss of quinic acid, according to published literature, it was identified as coumaroylquinic acid [11]. Based on the [M−H]− ion and the MS2 spectra showed the characteristic fragmentation involving in cleavage of the hexosyl moiety (−162 Da) [29], hexoside derivatives of gallic acid were detected in walnut extract, for example gallic acid hexoside (m/z 331.07, peak 6) showed product ion at m/z 271 and 211, probably generated the hexose moiety fragmentation (−60 Da) and removal of two formaldehyde (CH2O) groups in the glucose moiety, respectively.

2.2.4. Identification of Quinones

The fragmentation of quinones was produced by cleaving the substituents or eliminating the carbon on the benzene ring; Quinones were identified by the characteristic ions produced by the neutral loss of H2O, CO or CH2 due to the cleavage of hydroxy group on the benzene ring [11]. For example, compound 72 was tentatively identified as naphthalenediol isomers on the molecular ions at m/z 161.06 and fragment ion at m/z 133.07, 115.06, 105.07 and 91.06 (Supplementary Materials Figure S7).

2.3. Comparative Analysis of Components in Walnut Husk and Pellicle

Among the characterized active components, 86 and 101 species were identified in the walnut husk and pellicle (Supplementary Materials Figure S8), respectively, with 33 different components in total (Table 2). Further analysis showed that the most diverse type was hydrolysable tannin (17 kinds), followed by flavonoids (5 kinds). Compared with the pellicle, naphthoquinones and flavonoids mainly appeared in husk, which was consistent with the main components detected in walnut husk in previous studies [30]. However, most of the flavanols and condensed tannins appeared in the pellicle; flavanol is a precursor for the synthesis of condensed tannins, which was consistent with the astringency in pellicle [31].

Table 2.

Classification of different components in husk and pellicle of walnut.

| Classification | Husk | Pellicle |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrolyzable tannins |

digalloyl-glucose, ellagic acid galloyl pentose, galloyl methylgalloyl dexoyhexoside isomer, tetragalloyl-glucose, trigalloyl-glucose, calamanin A isomer, digalloyl-HHDP-glucose, ellagic acid hexoside isomer, ellagic acid pentoside isomer, galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose, galloyl-HHDP-glucose, heterophylliin E isomer, methyl ellagic acid pentose, Tellimagrandin II, trigalloyl-HHDP-glucose, HHDP-glucose isomer, pedunculagin/casuariin isomer (bis-HHDP-glucose) | |

| Flavonoids | quercetin pentoside isomer, taxifolin, taxifolin-3-O-arabinofuranoside isomer | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside isomer, (−)-epicatechin 3-O-gallate |

| Phenolic acid | protocatechualdehyde, 7-hydroxy-methylcoumarin | gallic acid hexoside |

| Quinones | dihydroxy-naphthoquinone isomer | |

| Terpenoids | cuminaldehyde, valoneic acid dilactone | |

| Condensed tannins |

B-type procyanidin dimer isomer, procyanidin trimer, (epi)catechin-(4, 8’)-3’-O-galloyl-(epi)catechin |

2.4. Content Variation of Main Phenolic Compounds during Walnut Ripening

Sixteen polyphenols were chosen for further quantification. In order to determine the polyphenols quickly and accurately, the composition and pH of the mobile phase, flow rate, injection volume, column temperature and elution condition were optimized. The calibration curves and results of individual components of walnut polyphenols are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S1 and Figure S9.

Although Q-Orbitrap is highly sensitive and suitable for identification compounds, due to its relatively high instrument cost, HPLC was used to quantify the dynamic changes of several main phenolics. During walnut growth and development stage, in the husk, the content of neochlorogenic acid, catechin, chlorogenic acid, myricetin and juglone showed a downward trend; p-hydroxybenzoic acid, p-coumaric acid and vanillic acid showed an upward trend; rutin, syringic acid, ferulic acid, o-coumaric acid, caffeic acid and quercetin showed a W-type curve, all of their content was highest in fruit-bearing stage; and caffeic acid was only detected in the mature stage. In the pellicle, most of the polyphenol components showed an increasing trend; however, the content of juglone was higher in the fruit enlargement stage; it then decreased and rose again in the hard-stone stage and slightly decreased in the mature stage. The change trend of ferulic acid was contrary to juglone; quercetin content increased from fruit enlargement stage to kernel filling stage and then decreased; neochlorogenic acid and vanillic acid were only detected in the hard-stone stage and mature stage (Table 3).

Table 3.

The contents of 16 polyphenols in walnut husk and pellicle during development by HPLC.

| Husk | Pellicle | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | FBS | FES | HSS | KFS | MS | FES | HSS | KFS | MS |

| Gallic acid | 16.52 ± 0.49 a | 2.88 ± 0.30 c | 2.72 ± 0.08 c | 4.24 ± 0.08 b c | 1.11 ± 0.01 d | 77.08 ± 6.11 d | 214.28 ± 6.62 c | 353.38 ± 12.26 a | 325.78 ± 1.93 b |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 89.09 ± 3.90 a | 34.61 ± 1.25 b | 23.42 ± 1.50 d | 17.34 ± 0.62 c | 13.65 ± 0.58 e | <LOD a | <LOD a | 374.60 ± 20.48 b | 530.92 ± 18.87 a |

| Catechin | 162.37 ± 3.30 a | 93.97 ± 0.99 b | 68.37 ± 0.29 c | 63.30 ± 2.53 c | 54.71 ± 4.50 c | 587.29 ± 47.49 b | 787.23 ± 44.09 a b | 942.33 ± 53.93 a | 302.39 ± 6.83 c |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 10.44 ± 0.87 a | 0.30 ± 0.01 c | 0.26 ± 0.01 d | 1.01 ± 0.03 b c | 1.10 ± 0.11 b | 152.98 ± 3.36 b | 174.55 ± 7.91 a | 171.54 ± 18.13 a | 195.56 ± 8.64 a |

| Chlorogenic acid | 2.41 ± 0.14 a | 1.61 ± 0.08 b | 1.18 ± 0.01 c | <LOD a | <LOD a | 15.96 ± 1.32 c | 30.25 ± 0.01 b | 41.36 ± 1.29 a | <LOD a |

| Vanillic acid | 30.25 ± 0.12 a | 0.25 ± 0.04 e | 0.57 ± 0.02 d | 0.94 ± 0.08 c | 1.47 ± 0.04 b | <LOD a | 77.09 ± 6.11 a | 47.24 ± 0.60 b | <LOD a |

| Caffeic acid | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a | 0.66 ± 0.01 a | 13.42 ± 0.86 c | 24.83 ± 0.68 b | 60.12 ± 2.51 a | 80.15 ± 2.75 a |

| Epicatechin | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a | 1.31 ± 0.08 a | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a | <LOD a |

| Syringic acid | 8.23 ± 0.05 a | 2.18 ± 0.15 c | 5.46 ± 0.05 b | 1.61 ± 0.09 c | 2.07 ± 0.22 c | 113.94 ± 5.77 c | 154.54 ± 2.94 b | 210.84 ± 9.07 a | 214.35 ± 8.67 a |

| p-Coumaric acid | 0.76 ± 0.06 a | <LOD a | 0.12 ± 0.00 d | 0.16 ± 0.00 c | 0.29 ± 0.00 b | 2.99 ± 0.26 d | 5.42 ± 0.32 c | 7.42 ± 0.17 b | 12.72 ± 0.02 a |

| Ferulic acid | 2.14 ± 0.10 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 c | 0.46 ± 0.04 b c | 0.30 ± 0.03 d | 0.65 ± 0.03 b | 1.49 ± 0.03 c | 4.70 ± 0.06 a | 1.85 ± 0.12 c | 4.24 ± 0.11 b |

| o-Coumaric acid | 0.37 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 d | 0.29 ± 0.01 c | 0.19 ± 0.00 d | 0.33 ± 0.01 b | 0.52 ± 0.03 c | 1.50 ± 0.05 b c | 1.52 ± 0.10 b | 1.77 ± 0.06 a |

| Rutin | 54.39 ± 2.53 a | 6.21 ± 0.75 b c | 8.33 ± 0.95 b | 1.52 ± 0.36 d | 2.63 ± 0.04 c | 308.37 ± 10.35 d | 1023.80 ± 7.62 c | 1626.42 ± 7.61 b | 3623.17 ± 32.49 a |

| Myricetin | 326.56 ± 5.48 a | 64.16 ± 7.63 b | 61.21 ± 12.95 b | 34.20 ± 5.14 c | 34.98 ± 2.37 c | 3366.58 ± 9.27 c | 3086.85 ± 37.77 d | 4375.62 ± 83.86 b | 8453.82 ± 383.06 a |

| Quercetin | 23.32 ± 0.79 a | 6.02 ± 0.04 c | 9.99 ± 0.44 b | 5.97 ± 0.44 c | 6.48 ± 0.20 c | 24.52 ± 2.14 b | 34.84 ± 0.75 a | 18.04 ± 1.97 c | 4.54 ± 0.07 d |

| Juglone | 15.42 ± 0.46 a | 5.44 ± 0.20 b | 1.88 ± 0.13 c | 0.79 ± 0.01 d | 0.57 ± 0.01 e | 2.13 ± 0.17 a | 1.37 ± 0.04 b | 2.10 ± 0.08 a | 1.78 ± 0.01 a |

Note: FBS, fruit-bearing stage; FES, fruit enlargement stage; HSS, hard-stone stage; KFS, kernel filling stage; MS, mature stage; LOD, limit of detection. The number of independent original samples is 3; data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (μg/g fresh weight). Different letters for the same phenolic compound indicate significant differences among the different developmental stages (p < 0.05).

The content of polyphenols was significantly different between husk and pellicle, and it was higher in pellicle. At present, there are few studies on the trend of walnut components. In Shi’s study [14], a series of time nodes were chosen, and no trend was found. In this study, only the key nodes were studied, and we found a certain regularity trend between main components and the TPC/TFC (Table 4). In husk, the changes of gallic acid, neochlorogenic acid, catechin, rutin, myricetin and juglone were highly correlated with the changes of TPC/TFC, while in pellicle, the changes of p-coumaric acid, rutin and myricetin were highly correlated with the changes of TPC/TFC. In addition, the growth and development dynamics of walnuts in different environments are not identical, which also affect the content and composition of walnut polyphenols. Although the results in this paper are not exactly same as those of Shi et al., the main conclusion is identical, at the fruit bearing and early development stage, TPC and most polyphenols were the highest in husk, young fruit can be used as the first choice to study phenolic component.

Table 4.

Pearson-correlation study between individual phenolic and TPC/TFC in husk and pellicle of walnut.

| Husk | Pellicle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | TPC | TFC | TPC | TFC |

| Gallic acid | 0.962 ** | 0.969 ** | 0.716 | 0.62 |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 0.996 ** | 0.999 ** | 0.889 | 0.871 |

| Catechin | 0.994 ** | 0.991 ** | −0.632 | −0.721 |

| p-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 0.925 * | 0.959 | 0.946 | 0.895 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.884 * | 0.849 | −0.571 | −0.675 |

| Vanillic acid | 0.940 * | 0.971 ** | −0.319 | −0.455 |

| Caffeic acid | −0.48 | −0.36 | 0.921 | 0.886 |

| Epicatechin | −0.48 | −0.36 | - | - |

| Syringic acid | 0.83 | 0.842 | 0.805 | 0.729 |

| p−Coumaric acid | 0.783 | 0.847 | 0.994 ** | 0.969 * |

| Ferulic acid | 0.903 * | 0.949 | 0.512 | 0.448 |

| o−Coumaric acid | 0.439 | 0.532 | 0.766 | 0.661 |

| Rutin | 0.968 ** | 0.987 ** | 0.999 ** | 0.983 * |

| Myricetin | 0.975 ** | 0.992 ** | 0.968 * | 0.993 ** |

| Quercetin | 0.933 * | 0.953 * | −0.84 | −0.884 |

| Juglone | 0.990 ** | 0.993 ** | −0.164 | −0.085 |

| TFC | 0.991 ** | 0.989 * | ||

* There was significant correlation at 0.05 level (bilateral). ** There was significant correlation at 0.01 level (bilateral). Symbol “-” means no date.

There are relatively few studies on walnut components, and no reports about its tannin biosynthesis pathway, which limits the improvement of walnut genetic breeding. Therefore, to screen the key metabolism of walnut tannins, explore their relationship with the synthesis of walnut astringent substances and their regulatory of tannin metabolism for a deeper understanding of the regulatory mechanism of walnut tannin synthesis, and clarify its biology synthetic pathways, it is of great significance to enrich walnut genetics and breeding.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

“Wen 185” were collected from the Germplasm Resources Base in Tarim University (44°55′ N, 81°28′ E), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Five stages’ fruits were collected from April to September, namely fruit-bearing, fruit-enlargement, hard-stone, kernel-filling and mature stages; the green husk and pellicle of the seed were separated and treated with liquid nitrogen, and then they were stored in a freezer (−80 °C) until analysis.

3.2. Standards and Reagents

All standards were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid and acetic acid were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ, USA). Deionized water was prepared by using a Milli-Q system (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

3.3. Polyphenols Extraction

TPCs and TFCs were measured according to the method of Slinkard and Singleton [32] and Jia et al. [33], with some modifications. The extraction method is as follows: 2 g of each fresh mixed sample was grounded into powder and extracted with 40 mL of 50% methanol under ultrasonic conditions at 50 °C temperature for 45 min. The solution was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, and we collected the supernatants. Then, using a vacuum rotary evaporator, the residue was frozen in a lyophilizer (Labconco, Kansas, MO, USA). All samples were dissolved with 10 mL pure methanol, filtered (0.22 μm) and stored in a refrigerator (−20 °C) [14].

3.4. Preparation Standard Solution

Sixteen reference standards were accurately weighed and dissolved in the mixed standard working solutions at concentrations of 5.0–10.0 mg/mL for quantitative analysis. For the construction of calibration curves, 16 standard stock solutions were mixed and further diluted with 50% methanol to produce a series of standard solutions at the concentration range of 0.25–625.0 μg/mL. All solutions were stored at 4 °C, in a refrigerator, before analysis.

3.5. Qualitative and Quantitative Components in Walnut Husk and Pellicle

The identification samples were prepared by the following method of Liu et al. [11]. The extraction solution in 3.3 was diluted to 50% methanol for the quantification analysis.

A Thermo U-3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Q Exactive Orbitrap MS system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to identify the components in walnut. A Hypersil GOLD C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm) was applied for chromatographic separation, the condition of chromatography and mass spectrometry refer to the method used in Liu et al. [11]. The mass spectrometer was operated in both positive- and negative-ion modes. MS detection conditions were set as follows: spray voltage, +3.5 kV/−3.2 kV; capillary temperature, 320 °C; sheath gas, 35 arb; AUX gas, 10 arb; AUX gas heater temperature, 350 °C; s-lens RF level, 50; scan range, m/z 100−1500; resolution, 70,000 (MS1) and 17,500 (MS2 ); stepped normalized collision energy (NCE), 20, 40 and 60%; injection time, 3 s; frequency of Orbitrap mass calibration, once a week. The compounds library was build; a high-throughput search and a manual search were performed by matching with the library and fragment-ion information.

A Waters high-performance liquid chromatography system (Waters, Milford, MA) and an Agilent SB-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) were used to detect walnut polyphenols. The column temperature was 30 °C, and the injection volume was 10 μL. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min; the mobile phase consisted of water containing 0.5% acetic acid as eluent A and methanol as eluent B. The program of 280 nm detection wavelength was as follows: 0–10 min, 10–17.5% B; 10–11 min, 17.5–20% B; 11–35 min, 20–37% B; 35–38 min, 37–50% B; 38–40 min, 50–10% B (for gallic acid, neochlorogenic acid, (+)-catechin, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, epicatechin, syringic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid and o-coumaric acid). The gradient elution program of 251 nm wavelength was as follows: 0–5 min, 10–50% B; 5–15 min, 50–60% B; 15–25 min, 60–70% B; 25–30 min, 70–10% B (for rutin, myricetin, quercetin and juglone).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in triplicate. Quantification data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out on the quantitative data, using Microsoft Excel 2010 at a significance level of p < 0.05. MS data were processed by using Compound Discoverer 3.0 (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA, USA).

4. Conclusions

In this experiment, the components and contents of polyphenols in walnut husk and pellicle were analyzed by Q-Orbitrap combined with HPLC. This was the first time that the compositions of the walnut husk and pellicle were characterized and compared. A total of 110 components were successful characterized, and 33 different components were found in the husk and pellicle; most was hydrolysable tannin. The obtained compound information can be used as a reference for rapid analysis and identification compounds, which will not only support its efficient development and reuse but also benefit to explore hidden application value. In addition, 16 polyphenols were quantified; the dynamic trend analysis of the main phenolic content which was contained in walnut husk and pellicle provides a basis for exploring the differences between their metabolic pathways and analyzing their regulatory networks.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online, Figure S1: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of ellagitannins identified in the extract of walnut. * The peak numbers are according to Table 1, Figure S2: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of gallotannins identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S3: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of flavonoids identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S4: Extracted tandem mass spectra (MS2) of peak 29 identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S5: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of flavonol identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S6: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of flavanol identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S7: Extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) and tandem mass spectra (MS2) of quinones identified in the extract of walnut, Figure S8: Total-ion chromatograms in negative mode of walnut husk and pellicle extracts, Figure S9: HPLC chromatogram of the standard optimized system, Table S1: Calibration curves, Retention time, Linear ranges, LODs and LOQs for 16 analytes.

Author Contributions

F.S., conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation and writing—original draft; B.H., preparation the sample; Q.J., J.W. and C.W., resources; Z.L., writing—review and editing, and experimental guidance. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the XPCC’s key industry support plan project in Southern Xinjiang (2017DB006-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jahanban-Esfahlan A., Ostadrahimi A., Tabibiazar M., Amarowicz R. A Comprehensive review on the chemical constituents and functional uses of walnut (Juglans spp.) Husk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3920. doi: 10.3390/ijms20163920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grace M.H., Warlick C.W., Neff S.A., Lila M.A. Efficient preparative isolation and identification of walnut bioactive components using high-speed counter-current chromatography and LC-ESI-IT-TOF-MS. Food Chem. 2014;158:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardman W.E. Walnuts have potential for cancer prevention and treatment in mice. J. Nutr. 2014;144:555S–560S. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.188466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puupponen-Pimiä R., Nohynek L., Meier C., Kähkönen M., Heinonen M., Hopia A., Oksman-Caldentey K.M. Antimicrobial properties of phenolic compounds from berries. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;90:494–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey K.B., Rizvi S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009;2:270–278. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trandafir I., Cosmulescu S., Nour V. Phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity of walnut extract as influenced by the extraction method and solvent. Int. J. Food Eng. 2017;13:1–8. doi: 10.1515/ijfe-2015-0284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahanban-Esfahlan A., Amarowicz R. Walnut (Juglans regia L.) shell pyroligneous acid: Chemical constituents and functional applications. RSC Adv. 2018;8:22376–22391. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03684E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez M.L., Labuckas D.O., Lamarque A.L., Maestri D.M. Walnut (Juglans regia L.): Genetic resources, chemistry, by-products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010;90:1959–1967. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Persic M., Mikulic-Petkovsek M., Slatnar A., Solar A., Veberic R. Changes in phenolic profiles of red-colored pellicle walnut and hazelnut kernel during ripening. Food Chem. 2018;252:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colaric M., Veberic R., Solar A., Hudina M., Stampar F. Phenolic acids, syringaldehyde, and juglone in fruits of different cultivars of Juglans regia L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:6390–6396. doi: 10.1021/jf050721n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P.Z., Li L.L., Song L.J., Sun X.T., Yan S.J., Huang W.J. Characterisation of phenolics in fruit septum of Juglans regia Linn. by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Food Chem. 2019;286:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koleckar V., Kubikova K., Rehakova Z., Kuca K., Jun D., Jahodar L., Opletal L. Condensed and hydrolysable tannins as antioxidants influencing the health. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2008;8:436–447. doi: 10.2174/138955708784223486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum F. High performance liquid chromatography. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2014;75:C18–C21. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2014.75.Sup2.C18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi B.B., Zhang W.E., Li X., Pan X.J. Seasonal variations of phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity of walnut (Juglans sigillata Dode) green husks. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20:S2635–S2646. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2017.1381706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosmulescu S., Trandafir I. Seasonal variation of total phenols in leaves of walnut (Juglans regia L.) J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:4938–4942. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu W.J., Wang M.M., Han F., Li M.C. Comparison of polyphenols content in different parts of different walnut of Xinjiang. Fram Prod. Process. 2018;11:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vu D.C., Vo P.H., Coggeshall M.V., Lin C.H. Identification and characterization of phenolic compounds in black walnut kernels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:4503–4511. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu R.X., Zhao Z.Y., Dai S.J., Che X., Liu W.H. Identification and quantification of bioactive compounds in Diaphragma juglandis fructus by UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS and UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:3811–3825. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia X.D., Luo H.T., Xu M.Y., Zhai M., Guo Z.R., Qiao Y.S., Wang L.J. Dynamic changes in phenolics and antioxidant capacity during pecan (Carya illinoinensis) kernel ripening and its phenolics profiles. Molecules. 2018;23:435. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escobar-Avello D., Lozano-Castellón J., Mardones C., Pérez A.J., Saéz V., Riquelme S., Baer D.V., Vallverdú-Queralt A. Phenolic profile of grape canes: Novel compounds identified by LC-ESI-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS. Molecules. 2019;24:3763. doi: 10.3390/molecules24203763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasić V., Gašić U., Stanković D., Lušić D., Vukić-Lušić D., Milojković-Opsenica D., Tešić Ž., Trifković J. Towards better quality criteria of European honeydew honey: Phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2019;274:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun G.D., Huo J.H., Wang G.L., Wang W.M. Identification and characterization of chemical constituents in Cortex Juglandis Mandshuricae based on UPLC-Q-TOF/MS. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 2017;48:657–667. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regueiro J., Sánchez-González C., Vallverdú-Queralt A., Simal-Gándara J., Lamuela-Raventós R., Izquierdo-Pulido M. Comprehensive identification of walnut polyphenols by liquid chromatography coupled to linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2014;152:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilary S., Tomás-Barberán F.A., Martinez-Blazquez J.A., Kizhakkayi J., Souka U., Al-Hammadi S., Habib H., Ibrahim W., Platat C. Polyphenol characterisation of Phoenix dactylifera L. (date) seeds using HPLC-mass spectrometry and its bioaccessibility using simulated in-vitro digestion/Caco-2 culture model. Food Chem. 2020;311:125969.1–125969.9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada H., Wakamori S., Hirokane T., Ikeuchi K., Matsumoto S. Structural revisions in natural ellagitannins. Molecules. 2018;23:1901. doi: 10.3390/molecules23081901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez-Caravaca A.M., Verardo V., Segura-Carretero A., Caboni M.F., Fernández-Gutiérrez A. Development of a rapid method to determine phenolic and other polar compounds in walnut by capillary electrophoresis-electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1209:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terra X., Pallarés V., Ardèvol A., Bladé C., Fernández-Larrea J., Pujadas G., Salvadó J., Arola L., Blay M. Modulatory effect of grape-seed procyanidins on local and systemic inflammation in diet-induced obesity rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011;22:380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonetti D., Soleti R., Clere N., Vergori L., Jacques C., Duluc L., Dourguia C., Maitinez M.C., Andriantsitohaina R. Extract enriched in flavan-3-ols and mainly procyanidin dimers improves metabolic alterations in a mouse model of obesity-related disorders partially via estrogen receptor alpha. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:406–419. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallverdú-Queralt A., Boix N., Piqué E., Gómez-Catalan J., Medina-Remon A., Sasot G., Mercader-Martí M., Llobet J.M., Lamuela-Raventos R.M. Identification of phenolic compounds in red wine extract samples and zebrafish embryos by HPLC-ESI-LTQ-Orbitrap-MS. Food Chem. 2015;181:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao L.J., Zhang X., Chen C.Y., Li J., Zhao S.L. Research on the chemical components and pharmaceutical actions of walnut green husk. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2016;55:4630–4633. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimoda H., Tanaka J., Kikuchi M., Fukuda T., Ito H., Hatano T., Yoshida T. Effect of polyphenol-rich extract from walnut on diet-induced hypertriglyceridemia in mice via enhancement of fatty acid oxidation in the liver. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:1786–1792. doi: 10.1021/jf803441c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slinkard K., Singleton V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1977;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia Z.S., Tang M.C., Wu J.M. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999;64:555–559. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.