Abstract

On the basis of density functional theory calculations, we explored the catalytic properties of various heteroatom-doped black and gray arsenene toward the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). The calculation results show that pristine black (b-As) and gray arsenene (g-As) exhibit poor catalytic performance because of too weak intermediate adsorption. Heteroatom doping plays a key role in optimizing catalytic performance. Among the candidate dopants O, C, P, S, and Sb, O is the most promising one used in arsenene to improve the ORR and OER catalytic performance. Embedding O atoms could widely tune the binding strength of reactive intermediates and improve the catalytic activity. Single O-doped g-AsO1 can achieve efficient bifunctional activity for both the OER and the ORR with optimal potential gap. b-AsO and b-AsO2 exhibit the optimal OER and ORR catalytic performance, respectively. For the HER, double C-doped g-AsC could tune the adsorption of hydrogen to an optimal value and significantly enhance the catalytic performance. These findings indicate that arsenene could provide a new platform to explore high-efficiency electrocatalysts.

Introduction

The development of effective catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) are highly desirable for new clean energy technologies. Nowadays, various two-dimensional (2D) layered materials have been extensively explored as high-performance catalysts, including heteroatom-doped graphene for the ORR and OER,1,2 black phosphorus (BP) for the OER,3−5 MoS2 and SnS2 for the HER,6,7 transition-metal-anchored C2N for the HER and OER,8 etc.9,10

Recently, elemental 2D layered arsenic (As) of the same group V element as P has attracted extensive attention due to its unique electronic and structural properties. Arsenic exists in two most widely studied allotropes: black arsenic and gray arsenic.11−14 As a cousin of BP, black arsenic also possesses the orthorhombic puckered honeycomb structure.11,12 Gray arsenic has the same hexagonal buckled geometry as blue phosphorus.12 Some studies have verified that black arsenic shows anisotropic and thickness-dependent semiconductor characteristics.15,16 Upon reducing the layer numbers to the monolayer, black arsenic exhibits the transformation of the direct–indirect band gap,17 while gray arsenic exhibits the transformation from semimetals to semiconductors.18 More importantly, black and gray arsenic monolayers (arsenene) have been predicted to possess high carrier mobility,15,16,19 which will accelerate the electron transport of the electrocatalytic reaction. Black and gray arsenene also possess a relatively good environmental stability that is critical for catalytic durability.16 On the basis of these distinct properties, arsenene has shown great potential for many emerging applications, including thermoelectric applications20,21 and field-effect transistors.16 In addition to the above applications, these excellent structural and electronic characteristics may also endow arsenene with potential catalytic application for the ORR, OER, and HER.

Pristine black and gray arsenene could also be chemically modified to exhibit superior structural and electronic properties. For example, Sturala et al. have predicted that through chemical modification of the surface, multilayer and monolayer arsenic materials can obtain large surface coverage and high luminescence.22 Li et al. have suggested that by doping heteroatoms B, C, N, O, etc., gray arsenene can realize tunable electronic structures and magnetic properties, which indicates that doped gray arsenene will possess promising potential for applications in electronics and spintronics.23 In addition, it was reported that O-dopant-modified black arsenene can act as an effective HER electrocatalyst with high catalytic activity.24 Therefore, we believe that impurity doping could greatly tune the catalytic activities of black and gray arsenene. Although great progress has been made in investigating the geometric structures and electronic properties of pristine and impurity-doped arsenene, experimental and theoretical research toward the ORR, OER, and HER of heteroatom-doped black and gray arsenene materials has never been reported.

In this work,

based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations,

the ORR, OER, and HER catalytic performances of heteroatom-doped black

arsenene (b-As) and gray arsenene (g-As) have been studied. The results

show that O atoms are more easily embedded into the arsenene lattice

than other heteroatoms, especially for double O-atom doping. By calculating

the overpotentials of the ORR/OER processes and the Gibbs free energy

of H* adsorption for the HER, we find that pristine b-As and g-As

exhibit poor catalytic activities. O and C dopants can effectively

tune the absorption strength of intermediates and thus enhance catalytic

activities. Single O-doped  is best suited for

the OER process, and

optimal ORR activities could be realized on double O-doped

is best suited for

the OER process, and

optimal ORR activities could be realized on double O-doped  . The reaction free

energies of H* could

be optimized to the appropriate value on double C-doped

. The reaction free

energies of H* could

be optimized to the appropriate value on double C-doped  , indicating improved

HER catalytic performance.

The present findings could provide a useful guidance for developing

multifunctional arsenene-based metal-free catalysts.

, indicating improved

HER catalytic performance.

The present findings could provide a useful guidance for developing

multifunctional arsenene-based metal-free catalysts.

Computational Methods

First-principle calculations were performed within the framework of spin-polarized DFT, as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP).25,26 The projector augmented wave pseudopotential is used to describe nuclei–electron interactions,27 while the electronic exchange–correlation corrections were described within the generalized gradient approximation, as parameterized by Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof.28 A cutoff energy of 500 eV was used within the plane wave basis set. To evaluate the catalytic performance, we constructed 4 × 4 × 1 b-As and 5 × 5 × 1 g-As supercells, as shown in Figure S1. The Brillouin zone was sampled using a 5 × 5 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack grid centered at the gamma (Γ) point. All atoms in the cell are fully optimized until the force acting on each atom is less than 0.02 eV Å–1. A vacuum region of 15 Å is created in the slab model to neglect the interaction between adjacent models, and we employ the DFT-D3 scheme to describe the dispersion interaction between model surfaces and adsorbed intermediates.29,30

The formation energies Ef’S of substitutional atoms (O, C, P, S, and Sb) in b-As and g-As lattices are calculated by31,32

| 1 |

where Etot(m) and Etot are the total energies of the heteroatom-doped and pristine b-As/g-As surface, respectively; μAs is the chemical potential of As and is calculated from the bulk phase of As; μX is the chemical potential of the introduced X atoms (X = O, C, P, S, and Sb) and calculated as in O2, graphene, bulk phase of BP, alpha-S, and Sb, respectively; and m is the number of substituted X atoms in the model.

According to the standard hydrogen electrode method, the four-electron ORR and OER reaction progress is investigated in an acidic environment.33,34 The OER could occur along the following reaction paths:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where * stands for the absorption site on the catalyst surface; (l) and (g) indicate the liquid and gas phases, respectively; O*, OH*, and OOH* represent the adsorbed intermediates. The ORR reaction is the reverse process of the OER listed above from eqs 2–5.

The ORR and OER overpotentials (η’s) can be obtained by calculating the Gibbs free energy ΔG for each reactive step of eqs 2–5. ΔG is defined by the following equation:

| 6 |

The details of the parametric description in eq 6 and the calculation process for η’s are described in the Supporting Information.

The HER reaction progress is also investigated in an acidic environment, and the catalytic performance can be evaluated by calculating the Gibbs free energy ΔGH* of adsorbed hydrogen, defined as6

| 7 |

where ΔZPE and ΔS are the zero-point energy change and vibrational entropy correction and ΔEH* is the adsorbed energy of H* and can be calculated by10

| 8 |

where EH* and Esurface are the total energies

of the surface

with and without adsorbed H*, respectively, and  is

the total energy of the gas-phase H2 molecule. The vibrational

entropy of H* is negligible; hence,

is

the total energy of the gas-phase H2 molecule. The vibrational

entropy of H* is negligible; hence,  , where

, where  is

the entropy of H2 in the

gas phase under standard conditions, as shown in Table S1. Therefore, ΔGH* with the overall correction can be written as35

is

the entropy of H2 in the

gas phase under standard conditions, as shown in Table S1. Therefore, ΔGH* with the overall correction can be written as35

| 9 |

Results and Discussion

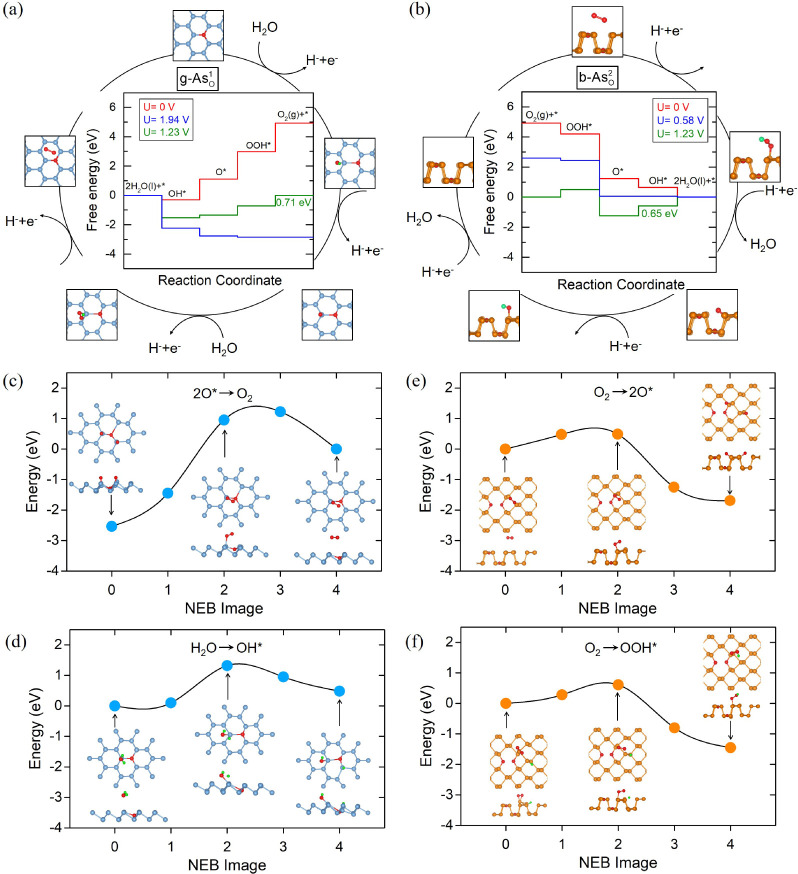

The ORR (ηORR) and OER (ηOER) overpotentials are usually used to characterize the ORR/OER catalytic performance, which can be obtained from the reaction free-energy diagrams.33,34,36Figure 1a,b displays the free-energy diagrams for the ORR/OER of pristine black arsenene (b-As) and gray arsenene (g-As) at different electrode potentials U. The forward (2H2O + * → O2) and backward (O2 → 2H2O + *) processes represent the OER and ORR, respectively. The overpotentials of ηOER and ηORR are denoted by blue and red arrows, and the adsorbed intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*) are displayed below each free-energy diagram. For the OER on pristine b-As in Figure 1a, at U = 1.23 V of the equilibrium potential shown in green lines, the transformations of OH* → O* and OOH* → O2 are downhill. However, elementary reaction steps of H2O → OH* and O* → OOH* both are uphill, and the highest free-energy gain of 1.85 eV for O* → OOH* has to be overcome. Only when U increases to 3.08 V, as shown in blue lines, can all reaction steps become downhill and occur spontaneously. Hence, 1.85 V is the OER overpotential ηOER and the step of O* → OOH* is the rate-determining step (RDS). For the ORR process, at U = 1.23 V, the step of O2 → OOH* possesses the highest free-energy gain of 2.49 eV, determining the ORR-RDS. As shown in the red lines, at U = −1.26 V, this free-energy gain will vanish and all steps are downhill, corresponding to ηORR = 2.49 V. Similarly, for pristine g-As in Figure 1b, the RDSs of the OER and ORR also arise from O* → OOH* with ηOER = 1.72 V and from O2 → OOH* with ηORR = 2.40 V, respectively, which are mainly attributed to the weak adsorption of the intermediate OOH*. According to the Sabatier principle, the catalytic activities strongly depend on the adsorption strength of intermediates, which should be not too weak nor too strong for an effective catalyst.37 Too weak adsorption will result in an inefficient reaction, while too strong adsorption of the intermediates will gradually terminate the reaction by blocking the catalytic active sites. The calculated high OER and ORR overpotentials in Figure 1 indicate that pristine b-As and g-As could not act as effective catalysts.

Figure 1.

Free-energy diagrams for OER and ORR elementary steps on pristine (a) black and (b) gray arsenene at different electrode potentials U. The atomic structures (top and side views) of the adsorbed intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* are also shown below each diagram.

To improve the catalytic properties of b-As and

g-As, we employ

chemical modification by embedding a variety of heteroatoms including

O, C, P, S, and Sb into the arsenene lattice. The calculated formation

energies Ef’s for different kinds

of X-doped (X = O, C, P, S, and

Sb) b-As and g-As are presented in Figure 2a. For each heteroatom, two types of configurations

with a single dopant and double dopants are calculated. The more negative

value of Ef corresponds to more stable

doping configurations. As shown in Figure 2a, compared to other heteroatoms, O atom

doping exhibits a relatively smaller Ef value whether for a single dopant and double dopants, indicating

that it is more likely to be embedded into b-As and g-As lattices

than other heteroatoms. Furthermore, Ef’s of double O-doped  and

and  are smaller than those

of single O-doped

are smaller than those

of single O-doped  and

and  , which suggests that

the interaction with

each other between O atoms can further help stabilize defective configuration.

In addition, other double atom-doped configurations also exhibit a

negative Ef value, such as

, which suggests that

the interaction with

each other between O atoms can further help stabilize defective configuration.

In addition, other double atom-doped configurations also exhibit a

negative Ef value, such as  ,

,  , and

, and  . Based on the above

analysis, in the following

discussion, we will focus on the catalytic properties for the ORR,

OER, and HER on O-doped b-As and g-As and add other stable heteroatom-doped

configurations for comparison. Figure 2b–e displays the atomic structures of respective

single and double O-doped b-As (

. Based on the above

analysis, in the following

discussion, we will focus on the catalytic properties for the ORR,

OER, and HER on O-doped b-As and g-As and add other stable heteroatom-doped

configurations for comparison. Figure 2b–e displays the atomic structures of respective

single and double O-doped b-As ( and

and  ) and g-As (

) and g-As ( and

and  ). To further identify

the stability of

heteroatom-doped arsenene, we perform the ab initio molecular dynamic

simulations at a temperature of 300 K to examine the dynamic stability. Figure S2 shows the fluctuation of the total

energy during the MD simulations and the corresponding snapshots for

representative

). To further identify

the stability of

heteroatom-doped arsenene, we perform the ab initio molecular dynamic

simulations at a temperature of 300 K to examine the dynamic stability. Figure S2 shows the fluctuation of the total

energy during the MD simulations and the corresponding snapshots for

representative  ,

,  , and

, and  . Compared with the

initial snapshots at

0 ps, all structures exhibit slight changes at room temperature, suggesting

the high structural stability.

. Compared with the

initial snapshots at

0 ps, all structures exhibit slight changes at room temperature, suggesting

the high structural stability.

Figure 2.

(a) Formation energy for single and double

X-doped gray arsenene

( and

and  ) and black arsenene

(

) and black arsenene

( and

and  ) (X = C, O, P, S, and

Sb). O-doped atomic structures of (b)

) (X = C, O, P, S, and

Sb). O-doped atomic structures of (b)  , (c)

, (c)  , (d)

, (d)  , and (e)

, and (e)  . Purple, blue, and

red balls indicate As

atoms in black and gray arsenene, and O atoms, respectively.

. Purple, blue, and

red balls indicate As

atoms in black and gray arsenene, and O atoms, respectively.

Figure 3a shows

the calculated OER overpotentials ηOER’s at

different active sites for pristine and O-doped b-As/g-As. For comparison,

we add the overpotential data of C-doped b-As/g-As. Table 1 summarizes the calculated free

energies of the adsorbed intermediates and overpotentials in investigated

configurations, and atomic structures of O- and C-doped clusters with

detailed active sites are shown in Figure S3. As shown in Figure 3a, the ηOER’s of these structures exhibit

a typical volcano shape, suggesting that introducing heteroatoms can

tune the OER catalytic activity in a wide range. Obviously, pristine

b-As and g-As with high ηOER values of 1.85 and 1.72

V locate at the bottom of the OER volcano, indicating the poor OER

catalytic activity. In contrast, close to the peak of the volcano,

as shown by the red arrow, single O-doped  exhibits the lowest

ηOER of 0.71 V, indicating improved OER catalytic

activity. For O-doped

b-As, the optimal OER catalytic active site also locates on the single

O-doped configuration

exhibits the lowest

ηOER of 0.71 V, indicating improved OER catalytic

activity. For O-doped

b-As, the optimal OER catalytic active site also locates on the single

O-doped configuration  with ηOER = 0.94 V, as

denoted by the blue arrow. In addition, it is worth noting that single

C-doped

with ηOER = 0.94 V, as

denoted by the blue arrow. In addition, it is worth noting that single

C-doped  shown by

the black diamond also locates

near the peak of the volcano, indicating excellent catalytic performance,

but it is very difficult to prepare

shown by

the black diamond also locates

near the peak of the volcano, indicating excellent catalytic performance,

but it is very difficult to prepare  in experiments because

of its high Ef, as shown in Figure 2a. Therefore, we do not choose

in experiments because

of its high Ef, as shown in Figure 2a. Therefore, we do not choose  as an effective OER

catalyst.

as an effective OER

catalyst.

Figure 3.

(a) Volcano plots for the OER vs the difference between adsorption

energies of O* and OH* for single and double C- and O-doped b-As and

g-As. Free-energy diagrams for the optimal OER on (b)  and (c)

and (c)  at U = 1.23 V. The corresponding

atomic structures of the adsorbed intermediate OOH* are shown in the

insets.

at U = 1.23 V. The corresponding

atomic structures of the adsorbed intermediate OOH* are shown in the

insets.

Table 1. Adsorption Energies of Intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*) in Electronvolt, Reaction Free Energies in Electronvolt of Each Reactive Step along the OER Reaction Pathway and OER/ORR Overpotentials in Volt at Different Active sites for C- and O-doped black and gray arsenenea.

| ΔGOH* | ΔGO* | ΔGOOH* | ΔG1 | ΔG2 | ΔG3 | ΔG4 | ηOER | ηORR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A | –0.30 | 1.11 | 2.97 | –0.30 | 1.41 | 1.86 | 1.94 | 0.71 | 1.53 |

| B | 0.95 | 1.64 | 4.38 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 2.74 | 0.54 | 1.52 | 0.68 | |

| C | 0.75 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 2.99 | 1.76 | 0.89 | |

|

A | 0.74 | 1.15 | 4.10 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 2.95 | 0.81 | 1.72 | 0.82 |

| B | 1.19 | 1.44 | 4.44 | 1.19 | 0.25 | 2.99 | 0.47 | 1.76 | 0.97 | |

|

A | –0.81 | 0.87 | 2.74 | –0.81 | 1.68 | 1.86 | 2.17 | 0.94 | 2.04 |

| B | –0.01 | 1.18 | 3.36 | –0.01 | 1.19 | 2.18 | 1.56 | 0.95 | 1.24 | |

|

A | 0.33 | 2.74 | 3.96 | 0.33 | 2.40 | 1.22 | 0.95 | 1.17 | 0.89 |

| B | 0.64 | 1.22 | 4.19 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 2.97 | 0.72 | 1.74 | 0.65 | |

|

A | 0.43 | 1.48 | 3.50 | 0.43 | 1.04 | 2.00 | 1.42 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| B | 1.14 | 1.66 | 4.42 | 1.14 | 0.51 | 2.76 | 0.49 | 1.53 | 0.73 | |

| C | 0.62 | 1.54 | 3.84 | 0.62 | 0.91 | 2.27 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 0.60 | |

|

A | 1.98 | 1.54 | 5.26 | 1.98 | –0.44 | 3.72 | –0.34 | 2.49 | 1.67 |

| B | 1.38 | 1.69 | 4.86 | 1.38 | 0.31 | 3.17 | 0.06 | 1.94 | 1.17 | |

| C | 1.68 | 1.87 | 5.00 | 1.68 | 0.20 | 3.13 | –0.08 | 1.90 | 1.31 | |

|

A | –0.06 | 0.16 | 3.04 | –0.06 | 0.22 | 2.88 | 1.88 | 1.65 | 1.29 |

| B | 0.84 | 1.25 | 4.29 | 0.84 | 0.41 | 3.03 | 0.62 | 1.80 | 0.81 | |

|

A | 1.72 | 1.78 | 4.89 | 1.72 | 0.06 | 3.11 | 0.03 | 1.88 | 1.20 |

| B | 1.50 | 1.47 | 4.82 | 1.50 | –0.04 | 3.35 | 0.10 | 2.12 | 1.27 | |

| C | 0.77 | 1.30 | 4.29 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 2.98 | 0.62 | 1.75 | 0.69 |

The detailed atomic structures are displayed in Figure S3.

The origin of reactive overpotentials

can be better understood

by plotting the free-energy diagrams, and the overpotentials strongly

depend on the free-energy difference between two reactive intermediates

of the RDSs. Figure 3b,c shows the OER free-energy diagrams on  and

and  at the equilibrium

potential (U = 1.23 V), respectively. By comparing

the free-energy diagrams at U = 1.23 V in Figures 1a,b and 3b,c, it is clearly

shown that the introduction of O atoms considerably tunes and enhances

the binding strength of reactive intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*)

with more negative adsorption energies. For the OER on

at the equilibrium

potential (U = 1.23 V), respectively. By comparing

the free-energy diagrams at U = 1.23 V in Figures 1a,b and 3b,c, it is clearly

shown that the introduction of O atoms considerably tunes and enhances

the binding strength of reactive intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*)

with more negative adsorption energies. For the OER on  in Figure 3b, the RDS has translated to

the step of OOH* →

O2 (g) with a free-energy difference of 0.71 eV, corresponding

to the ηOER of 0.71 V. For

in Figure 3b, the RDS has translated to

the step of OOH* →

O2 (g) with a free-energy difference of 0.71 eV, corresponding

to the ηOER of 0.71 V. For  in Figure 3c, compared with pristine b-As

in Figure 1b, the step

of O* →

OOH* is still the OER RDS, while the free-energy gain has been reduced

to 0.94 eV, determining a better ηOER = 0.94 V.

in Figure 3c, compared with pristine b-As

in Figure 1b, the step

of O* →

OOH* is still the OER RDS, while the free-energy gain has been reduced

to 0.94 eV, determining a better ηOER = 0.94 V.

Similarly, in Figure 4a, we summarize the ORR overpotentials ηORR’s

at different active sites on pristine and C- and O-doped b-As/g-As.

ORR overpotentials exhibit a similar volcano shape and can be tuned

within a wide range. Clearly, as denoted by the green circles, pristine

b-As and g-As locate at the bottom of the volcano shape, indicating

poor catalytic activity. For b-As, double O-doped  locates near the top

of the volcano peak

and exhibits the best ORR catalytic performance, with the lowest ηORR = 0.65 V. Among all O-doped g-As,

locates near the top

of the volcano peak

and exhibits the best ORR catalytic performance, with the lowest ηORR = 0.65 V. Among all O-doped g-As,  is the most effective

ORR catalytic structure,

with ηORR = 0.68 V. The corresponding ORR free-energy

diagrams on

is the most effective

ORR catalytic structure,

with ηORR = 0.68 V. The corresponding ORR free-energy

diagrams on  and

and  are shown in Figure 4b,c, respectively.

The free-energy diagrams

in Figure 1 have shown

that the step of O2 → OOH* determines the ORR RDS

of pristine structures. In Figure 4b, the ORR RDS of

are shown in Figure 4b,c, respectively.

The free-energy diagrams

in Figure 1 have shown

that the step of O2 → OOH* determines the ORR RDS

of pristine structures. In Figure 4b, the ORR RDS of  still originates from

O2 →

OOH*, but compared to over-high ηORR of 2.40 V on

pristine g-As, the ηORR has been significantly reduced

to 0.68 V due to the enhanced adsorption of OOH*. For

still originates from

O2 →

OOH*, but compared to over-high ηORR of 2.40 V on

pristine g-As, the ηORR has been significantly reduced

to 0.68 V due to the enhanced adsorption of OOH*. For  in Figure 4c, the ORR RDS has translated

to the step of O →

OH*, and excessive overpotential for pristine b-As (2.49 V) has been

optimized to 0.65 V.

in Figure 4c, the ORR RDS has translated

to the step of O →

OH*, and excessive overpotential for pristine b-As (2.49 V) has been

optimized to 0.65 V.

Figure 4.

(a) Volcano plots for the ORR vs adsorption energies of

OH* on

single and double C and O-doped b-As and g-As. Free-energy diagrams

for the optimal ORR on (b)  and (c)

and (c)  at U = 1.23 V. The corresponding

atomic structures of the adsorbed intermediate OOH* are shown in the

insets.

at U = 1.23 V. The corresponding

atomic structures of the adsorbed intermediate OOH* are shown in the

insets.

The improved OER/ORR activities of the above-mentioned O-doped configurations can be effectively attributed to the redistribution of surface charges induced by the introduction of O dopants into g- and b-As lattices. As shown in Figure S5, the distribution map of the charge density difference clearly demonstrates strong charge transfer between O atoms and the surrounding As atoms. Furthermore, Bader charge analysis shows that due to the larger electronegativity of O than As, the embedded O atoms attract more electrons with a negative Bader charge value, while the surrounding As atoms lose electrons and become positively charged. These As atoms with positive effective charges will facilitate the adsorption of reactive intermediates (O*, OH*, and OOH*) with negative charges and can act as potential active sites. As shown in Figure S6, the adsorbed intermediates usually obtain electrons from the catalyst surface and compared with the adsorption on the pristine surface, there is much more charge transfer from the O-doped surface to intermediates. Therefore, the resulting charge transfer has an effect on the ability of the adsorbed intermediates to obtain electrons from the catalyst surface, which is related to the adsorption strength of the intermediates, thus tuning the catalytic activity within a wide range.

Nowadays,

people are developing high-performance bifunctional catalysts,

which can catalyze the ORR and OER simultaneously.1,38 The

bifunctional catalytic performance could be well evaluated by calculating

the ORR/OER potential gap, that is, the sum of ηORR and ηOER.39,40 The lower ORR/OER potential

gap corresponds to a better bifunctional catalytic activity. Figure 3a shows that  exhibits the best

OER catalytic performance,

with ηOER = 0.71 V. Considering that the optimal

ORR activity with ηORR = 0.68 V, as shown in Figure 4a,

exhibits the best

OER catalytic performance,

with ηOER = 0.71 V. Considering that the optimal

ORR activity with ηORR = 0.68 V, as shown in Figure 4a,  shows great potential

to act as an effective

bifunctional catalyst with a low ORR/OER potential gap of 1.39 V.

shows great potential

to act as an effective

bifunctional catalyst with a low ORR/OER potential gap of 1.39 V.

To better understand the overpotential origin, Figure 5a,b displays more detailed

free-energy diagrams for the optimal OER on  and ORR on

and ORR on  at different electrode

potentials, respectively.

In Figure 5a, for the

OER on

at different electrode

potentials, respectively.

In Figure 5a, for the

OER on  , when the

electrode potential U is 0 V, only the step of H2O → OH* is downhill

and other steps of OH* → O*, O* → OOH*, and OOH* →

O2 are uphill. As shown by the green lines, when U increases to the equilibrium potential 1.23 V, the free-energy

gains for the steps OH* → O*, O* → OOH*, and OOH* →

O2 have to be greatly reduced, but these three reactive

steps are still uphill, with the highest free-energy gain of 0.71

eV for OOH* → O2. Only when U increases

to 1.94 V shown by the blue lines, the free-energy gain of OOH* →

O2 could be reduced to zero and all reactive steps become

downhill, indicating that the OER reaction can occur spontaneously.

Therefore, ηOER is 1.94–1.23 = 0.71 V and

the RDS is the transformation from OOH* to O2. For the

ORR on

, when the

electrode potential U is 0 V, only the step of H2O → OH* is downhill

and other steps of OH* → O*, O* → OOH*, and OOH* →

O2 are uphill. As shown by the green lines, when U increases to the equilibrium potential 1.23 V, the free-energy

gains for the steps OH* → O*, O* → OOH*, and OOH* →

O2 have to be greatly reduced, but these three reactive

steps are still uphill, with the highest free-energy gain of 0.71

eV for OOH* → O2. Only when U increases

to 1.94 V shown by the blue lines, the free-energy gain of OOH* →

O2 could be reduced to zero and all reactive steps become

downhill, indicating that the OER reaction can occur spontaneously.

Therefore, ηOER is 1.94–1.23 = 0.71 V and

the RDS is the transformation from OOH* to O2. For the

ORR on  in Figure 5b, at U = 0 V, all steps are downhill.

However, when U increases to the equilibrium potential

1.23 V, three uphill steps appear and the transformation from O* to

OH* of the most endoergic step possesses the highest free-energy gain

of 0.65 eV. This free-energy gain will be reduced to zero only when U decreases to 0.58 V, corresponding to the ORR RDS of O*

→ OH*, with ηORR of 1.23–0.58 = 0.65

V. In addition, adsorbed intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* on

in Figure 5b, at U = 0 V, all steps are downhill.

However, when U increases to the equilibrium potential

1.23 V, three uphill steps appear and the transformation from O* to

OH* of the most endoergic step possesses the highest free-energy gain

of 0.65 eV. This free-energy gain will be reduced to zero only when U decreases to 0.58 V, corresponding to the ORR RDS of O*

→ OH*, with ηORR of 1.23–0.58 = 0.65

V. In addition, adsorbed intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* on  and

and  are shown in each

diagram. The detailed

top and side views of atomic structures and charge density difference

of the adsorbed intermediates are displayed in Figure S6. It is clearly shown that the reactive active sites

in

are shown in each

diagram. The detailed

top and side views of atomic structures and charge density difference

of the adsorbed intermediates are displayed in Figure S6. It is clearly shown that the reactive active sites

in  and

and  locate at As sites

around embedded O atoms,

and strong charge transfer usually occur at adsorbed intermediates,

active sites, and neighboring As atoms.

locate at As sites

around embedded O atoms,

and strong charge transfer usually occur at adsorbed intermediates,

active sites, and neighboring As atoms.

Figure 5.

Free-energy diagrams

for the optimal (a) OER on  and (b) ORR on

and (b) ORR on  at different electrode

potentials U. The

adsorbed intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* on

at different electrode

potentials U. The

adsorbed intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* on  and

and  are also shown. The

kinetic barriers for

(c) 2O* → O2 and (d) H2O → OH*

on

are also shown. The

kinetic barriers for

(c) 2O* → O2 and (d) H2O → OH*

on  , and (e) O2 dissociation via

O2 → 2O* and (f) O2 → OOH* on

, and (e) O2 dissociation via

O2 → 2O* and (f) O2 → OOH* on  .

.

Through evaluating the kinetic barrier using the climbing image

nudged elastic band method,32,41 we further examine

the possibility of particular reactive steps, in which two adsorbed

O* species combine to form a O2 molecule (2O* →

O2) on  for the OER

and a O2 molecule

dissociates to two O* species (O2 → 2O*) on

for the OER

and a O2 molecule

dissociates to two O* species (O2 → 2O*) on  for the ORR. For comparison,

we also examine

the kinetic feasibility of the OER and ORR initial reaction steps

of H2O → OH* on

for the ORR. For comparison,

we also examine

the kinetic feasibility of the OER and ORR initial reaction steps

of H2O → OH* on  and O2 →

OOH* on

and O2 →

OOH* on  , as shown

in Figure 5d,f, respectively. Figure 5c shows the reaction

progress of 2O* →

O2 on

, as shown

in Figure 5d,f, respectively. Figure 5c shows the reaction

progress of 2O* →

O2 on  , and it is

shown that the progress is endothermic

with a high energy barrier of ∼3.7 eV. This indicates that

during the OER on

, and it is

shown that the progress is endothermic

with a high energy barrier of ∼3.7 eV. This indicates that

during the OER on  , O* species

cannot directly coalesce to

produce O2 but must be assisted by the OOH* intermediate

group, as shown in Figure 5a. In contrast, in Figure 5d, the initial step of H2O → OH*

on

, O* species

cannot directly coalesce to

produce O2 but must be assisted by the OOH* intermediate

group, as shown in Figure 5a. In contrast, in Figure 5d, the initial step of H2O → OH*

on  exhibits a lower energy

barrier of ∼1.32

eV, suggesting better OER kinetic feasibility. In Figure 5e, the energy barrier for the

dissociative O2 → 2O* pathway on

exhibits a lower energy

barrier of ∼1.32

eV, suggesting better OER kinetic feasibility. In Figure 5e, the energy barrier for the

dissociative O2 → 2O* pathway on  is as low as ∼0.48

eV with the exothermic

feature, indicating that this reaction pathway could easily occur

kinetically. In addition, from Figure 5f, it can be seen that the associative reaction step

of O2 → OOH* on

is as low as ∼0.48

eV with the exothermic

feature, indicating that this reaction pathway could easily occur

kinetically. In addition, from Figure 5f, it can be seen that the associative reaction step

of O2 → OOH* on  also possesses a low

barrier of ∼0.61

eV, and the exothermic feature indicates that this pathway is favored

energetically. Therefore, for the ORR on

also possesses a low

barrier of ∼0.61

eV, and the exothermic feature indicates that this pathway is favored

energetically. Therefore, for the ORR on  , the O2 molecule may be able

to efficiently dissociate through dual reaction pathways: one is the

step-by-step reaction accompanied by the formation of the OOH* intermediate

(O2 → OOH* → 2O*), or the O2 molecule

dissociates directly into O* (O2 → 2O*). Such dual

reaction pathways will promote the ORR reaction rate on

, the O2 molecule may be able

to efficiently dissociate through dual reaction pathways: one is the

step-by-step reaction accompanied by the formation of the OOH* intermediate

(O2 → OOH* → 2O*), or the O2 molecule

dissociates directly into O* (O2 → 2O*). Such dual

reaction pathways will promote the ORR reaction rate on  .

.

Furthermore,

the influence of doping elements on HER catalytic

activity is also investigated. The HER catalytic performance can be

well characterized by the Gibbs free energy of H* adsorption (ΔGH*) on the reactive surface.42,43 The value of ΔGH* for an ideal

catalyst should be close to zero (ΔGH* ∼ 0). High ΔGH* will lead

to weak hydrogen adsorption on the catalyst surface, while low ΔGH* represents the strong binding of adsorbed

hydrogen and the surface, which will go against the dissociation of

the generated H2 molecule, both resulting in a slow HER

reaction. For better comparing the ΔGH* between different doping systems, we summarize the calculated ΔGH* at different reactive sites on  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  in Figure 6a. It can be seen that embedded

heteroatoms can tune

ΔGH* within a wide range, especially

for C and O dopants. Among these doped configurations,

in Figure 6a. It can be seen that embedded

heteroatoms can tune

ΔGH* within a wide range, especially

for C and O dopants. Among these doped configurations,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  can optimize ΔGH* to an appropriate value, which is close to zero and eligible

for HER catalysis, indicating improved reaction activity. Considering

the high formation energy of Sb dopants in Figure 2a, we only select C- and O-doped configurations

as effective HER catalysts, as labeled by black dotted rectangles

in Figure 6a. Figure 6b shows the HER free-energy

diagrams for pristine b-As/g-As,

can optimize ΔGH* to an appropriate value, which is close to zero and eligible

for HER catalysis, indicating improved reaction activity. Considering

the high formation energy of Sb dopants in Figure 2a, we only select C- and O-doped configurations

as effective HER catalysts, as labeled by black dotted rectangles

in Figure 6a. Figure 6b shows the HER free-energy

diagrams for pristine b-As/g-As,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . As indicated by green

and red lines, pristine

b-As and g-As exhibit very weak hydrogen adsorption, with ΔGH* = 1.29 and 1.38 eV, which are not conducive

to the catalytic reaction and even prevents the reaction from occurring.

Clearly, embedding C and O dopants can provide sufficient adsorption

strength, especially for

. As indicated by green

and red lines, pristine

b-As and g-As exhibit very weak hydrogen adsorption, with ΔGH* = 1.29 and 1.38 eV, which are not conducive

to the catalytic reaction and even prevents the reaction from occurring.

Clearly, embedding C and O dopants can provide sufficient adsorption

strength, especially for  with ΔGH* = 0.15 eV. The atomic structure of

with ΔGH* = 0.15 eV. The atomic structure of  with adsorbed H* is

displayed in the inset

of Figure 6b and the

active site arises from the embedded C atom. In Figure S5, the charge density difference and Bader charge

analysis clearly indicate that the enhanced HER activity mainly arises

from the strong charge transfer induced by the embedded O and C dopants,

which can effectively improve the adsorption strength of H*.

with adsorbed H* is

displayed in the inset

of Figure 6b and the

active site arises from the embedded C atom. In Figure S5, the charge density difference and Bader charge

analysis clearly indicate that the enhanced HER activity mainly arises

from the strong charge transfer induced by the embedded O and C dopants,

which can effectively improve the adsorption strength of H*.

Figure 6.

(a) Calculated

ΔGH* for single-

and double-doped structures ( ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , X = C, O, P, S, and Sb).

(b) HER free-energy diagrams for b-As, g-As,

, X = C, O, P, S, and Sb).

(b) HER free-energy diagrams for b-As, g-As,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . (c) Kinetic barriers

of the HER Tafel-step

reaction on

. (c) Kinetic barriers

of the HER Tafel-step

reaction on  . (d) Atomic

structures of initial, final,

and intermediate NEB images.

. (d) Atomic

structures of initial, final,

and intermediate NEB images.

For reducing protons to hydrogen in acid media, there exist two

different types of reaction pathways of the Volmer–Tafel and

Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism.6 The

Volmer reaction is the first step in the HER process and refers to

forming adsorbed H* from the initial adsorption of proton in acid

solution. Based on the Volmer reaction, in the Volmer–Tafel

mechanism, two adjacent adsorbed H* species then react to form a H2 molecule (H* + H* → H2). However, in the

Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism, adsorbed H* species reacts with

a proton accompanied by one electron to form a H2 molecule

(H* + H+ + e– → H2). Figure 6c presents the kinetic

progress of the HER on optimal  via the Tafel-step

reaction. The kinetic

barrier for this reaction is as high as ∼1.13 eV, comparable

to that of graphene(G)/MXene heterostructures (1.56 and 1.33 eV for

G/Mo2C and G/V2C, respectively)44 and MoS2 edges (1.0–1.5 eV),6 which will severely slow down the Tafel reaction.

However, the Heyrovsky-step reaction with a lower kinetic barrier

is usually much faster than the Tafel-step reaction.6 Therefore, the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism may be

the main reaction pathway of the HER on

via the Tafel-step

reaction. The kinetic

barrier for this reaction is as high as ∼1.13 eV, comparable

to that of graphene(G)/MXene heterostructures (1.56 and 1.33 eV for

G/Mo2C and G/V2C, respectively)44 and MoS2 edges (1.0–1.5 eV),6 which will severely slow down the Tafel reaction.

However, the Heyrovsky-step reaction with a lower kinetic barrier

is usually much faster than the Tafel-step reaction.6 Therefore, the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism may be

the main reaction pathway of the HER on  .

.

Since the electrocatalytic

processes typically take place at the

solid–liquid interfaces,45 it is

very necessary to explore the influence of the solvent effect on catalytic

activities. As shown in Figures S7–S9, we adopted the simple explicit model to tackle solvent effects,

in which multiple water molecules are added on the catalyst surfaces

to model the aqueous interface. The atomic structures of intermediates

clearly indicate that there exists obvious hydrogen bonding between

adsorbates and water molecules, which could further stabilize the

adsorption of intermediates. As shown in Figures S7 and S8, the hydrogen bonding has different stabilizing effects

for intermediates O*, OH*, and OOH* on  and

and  , affecting the catalytic

performance to

some extent. For example, the calculated OER overpotential on

, affecting the catalytic

performance to

some extent. For example, the calculated OER overpotential on  degenerates from 0.71

to 0.80 V at an aqueous

interface. For the HER process in Figure S9, it is clearly seen that the H* adsorption on

degenerates from 0.71

to 0.80 V at an aqueous

interface. For the HER process in Figure S9, it is clearly seen that the H* adsorption on  is further stabilized

by hydrogen bonding

with a lower ΔGH* value; hence,

the solvent effects give rise to a positive influence for the HER

activity on

is further stabilized

by hydrogen bonding

with a lower ΔGH* value; hence,

the solvent effects give rise to a positive influence for the HER

activity on  . Therefore,

to more accurately describe

the catalytic characteristics of real solid–liquid systems,

solvent effects should be carefully considered in computational simulation.

. Therefore,

to more accurately describe

the catalytic characteristics of real solid–liquid systems,

solvent effects should be carefully considered in computational simulation.

As we know that electrical conductivity is a critical characteristic

quantity that determines the electron-transfer efficiency and catalytic

activity, which requires that the catalysts should be metallic or

semiconductors. Therefore, it is very necessary to characterize the

electrical conductivity properties of catalysts. Figure S10 shows the density of states of  ,

,  , and

, and  with optimal catalytic

activities. It can

be clearly seen that

with optimal catalytic

activities. It can

be clearly seen that  and

and  demonstrate obvious

semiconductor properties,

and

demonstrate obvious

semiconductor properties,

and  exhibits favorable

metallicity, which indicates

that these explored surfaces possess good electrical conductivity

and can guarantee efficient electron transfer during catalytic reaction

progress. The calculated optimal overpotentials/ΔGH* and good electron-transfer characteristics together

prove the feasibility of our proposed effective catalysts.

exhibits favorable

metallicity, which indicates

that these explored surfaces possess good electrical conductivity

and can guarantee efficient electron transfer during catalytic reaction

progress. The calculated optimal overpotentials/ΔGH* and good electron-transfer characteristics together

prove the feasibility of our proposed effective catalysts.

Conclusions

In summary, using DFT calculations, we study the ORR, OER, and

HER catalytic activities of pristine and various heteroatom (O, C,

P, S, and Sb)-doped b-As/g-As. The results show that pristine b-As

and g-As exhibit poor catalytic performance for the ORR, OER, and

HER. Embedding heteroatoms can effectively tune the adsorption strength

of reactive intermediations and thus improve catalytic activities.

Compared with other candidate dopants (C, P, S, and Sb), O atoms are

more likely to be embedded into b-As and g-As lattices. More importantly,

O atom-modified b-As and g-As show superior catalytic properties for

the OER and ORR. For g-As, the OER and ORR catalytic activity can

be optimized simultaneously on single  , which exhibits great

potential as effective

bifunctional catalysts. However, the optimal OER and ORR catalytic

performance on b-As can be realized in

, which exhibits great

potential as effective

bifunctional catalysts. However, the optimal OER and ORR catalytic

performance on b-As can be realized in  and

and  , respectively. NEB

calculations suggest

that

, respectively. NEB

calculations suggest

that  can achieve

the dual ORR reaction pathway

through O2 → OOH* → 2O* and O2 → 2O*. For the HER, C-doped

can achieve

the dual ORR reaction pathway

through O2 → OOH* → 2O* and O2 → 2O*. For the HER, C-doped  shows the best catalytic

performance, with

an appropriate ΔGH* of 0.15 eV,

and the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism is the main reaction pathway.

These findings would trigger more theoretical and experimental works

to further investigate the catalytic properties of As-based materials.

shows the best catalytic

performance, with

an appropriate ΔGH* of 0.15 eV,

and the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism is the main reaction pathway.

These findings would trigger more theoretical and experimental works

to further investigate the catalytic properties of As-based materials.

Acknowledgments

Y.F. is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 11604092 and 11634001) and the National Basic Research Programs of China (grant no. 2016YFA0300900). The computational resources were provided by the supercomputer TianHe-1 in Changsha, China.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00908.

Further computational setups, detailed atomic structures of pristine black/gray arsenene and C- and O-doped configurations; scaling relationship between the adsorbed energies of reactive intermediates; and charge density difference for O*, OH*, and OOH* on

and

and  (PDF)

(PDF)

Author Contributions

# S.S. and P.S. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhang J.; Zhao Z.; Xia Z.; Dai L. A Metal-Free Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction and Oxygen Evolution Reactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 444–452. 10.1038/nnano.2015.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X. X.; Tang L. M.; Chen K.; Zhang L.; Wang E. G.; Feng Y. Bifunctional Mechanism of N, P Co-Doped Graphene for Catalyzing Oxygen Reduction and Evolution Reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 104701 10.1063/1.5082996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.; Zhou J.; Qi X.; Liu Y.; Huang Z.; Li Z.; Ge Y.; Dhanabalan S. C.; Ponraj J. S.; Wang S.; Zhong J.; Zhang H. Few-Layer Black Phosphorus Nanosheets as Electrocatalysts for Highly Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700396 10.1002/aenm.201700396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X.-X.; Shen S.; Jiang X.; Sengdala P.; Chen K.; Feng Y. Tuning the Catalytic Property of Phosphorene for Oxygen Evolution and Reduction Reactions by Changing Oxidation Degree. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 3440–3446. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.; Jiang X.; Yang Y.; Chen Q.; Xue X. X.; Chen K.; Feng Y. Synergy of Tellurium and Defects in Control of Activity of Phosphorene for Oxygen Evolution and Reduction Reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 22939–22946. 10.1039/C9CP04164H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Jiang D.-E. Mechanism of Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on 1T-MoS2 from First Principles. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4953–4961. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao G.; Xue X. X.; Wu B.; Lin Y. C.; Ouzounian M.; Hu T. S.; Xu Y.; Liu X.; Li S.; Suenaga K.; Feng Y.; Liu S. Template-Assisted Synthesis of Metallic 1T’-Sn0.3W0.7S2 Nanosheets for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 30, 1906069 10.1002/adfm.201906069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Chen A.; Zhang Z.; Jiao M.; Zhou Z. Transition Metal Anchored C2N Monolayers as Efficient Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen and Oxygen Evolution Reactions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11446–11452. 10.1039/C8TA03302A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.; Waclawik E. R.; Du A. Computational Screening of Two-Dimensional Coordination Polymers as Efficient Catalysts for Oxygen Evolution and Reduction Reaction. J. Catal. 2017, 352, 579–585. 10.1016/j.jcat.2017.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.; O’Mullane A. P.; Du A. 2d Mxenes: A New Family of Promising Catalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 494–500. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kou L.; Ma Y.; Tan X.; Frauenheim T.; Du A.; Smith S. Structural and Electronic Properties of Layered Arsenic and Antimony Arsenide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 6918–6922. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b02096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ersan F.; Aktürk E.; Ciraci S. Interaction of Adatoms and Molecules with Single-Layer Arsenene Phases. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 14345–14355. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b02439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Xie M.; Li F.; Yan Z.; Li Y.; Kan E.; Liu W.; Chen Z.; Zeng H. Semiconducting Group 15 Monolayers: A Broad Range of Band Gaps and High Carrier Mobilities. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 1698–1701. 10.1002/ange.201507568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal C.; Ezawa M. Arsenene: Two-Dimensional Buckled and Puckered Honeycomb Arsenic Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 085423. 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.085423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Chen C.; Kealhofer R.; Liu H.; Yuan Z.; Jiang L.; Suh J.; Park J.; Ko C.; Choe H. S.; Avila J.; Zhong M.; Wei Z.; Li J.; Gao H.; Liu Y.; Analytis J.; Xia Q.; Asensio M. C.; Wu J. Black Arsenic: A Layered Semiconductor with Extreme in-Plane Anisotropy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1800754 10.1002/adma.201800754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M.; Xia Q.; Pan L.; Liu Y.; Chen Y.; Deng H.-X.; Li J.; Wei Z. Thickness-Dependent Carrier Transport Characteristics of a New 2d Elemental Semiconductor: Black Arsenic. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1802581 10.1002/adfm.201802581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K.; Chen S.; Duan C. Indirect-Direct Band Gap Transition of Two-Dimensional Arsenic Layered Semiconductors—Cousins of Black Phosphorus. Sci. China: Phys., Mech. Astron. 2015, 58, 87301 10.1007/s11433-015-5665-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Yan Z.; Li Y.; Chen Z.; Zeng H. Atomically Thin Arsenene and Antimonene: Semimetal-Semiconductor and Indirect-Direct Band-Gap Transitions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 3112–3115. 10.1002/anie.201411246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Xie J.; Yang D.; Wang Y.; Si M.; Xue D. Manifestation of Unexpected Semiconducting Properties in Few-Layer Orthorhombic Arsenene. Appl. Phys. Express 2015, 8, 055201 10.7567/APEX.8.055201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Wang D.; Shuai Z. Puckered Arsenene: A Promising Room-Temperature Thermoelectric Material from First-Principles Prediction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 19080–19086. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b06196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeraati M.; Vaez Allaei S. M.; Abdolhosseini Sarsari I.; Pourfath M.; Donadio D. Highly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity of Arsenene: An Ab Initio Study. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 085424 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.085424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sturala J.; Ambrosi A.; Sofer Z.; Pumera M. Covalent Functionalization of Exfoliated Arsenic with Chlorocarbene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 14837–14840. 10.1002/anie.201809341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Xu W.; Yu Y.; Du H.; Zhen K.; Wang J.; Luo L.; Qiu H.; Yang X. Monolayer Hexagonal Arsenene with Tunable Electronic Structures and Magnetic Properties Via Impurity Doping. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 362–370. 10.1039/C5TC03001C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S.; Gan Y.; Xue X.-X.; Wei J.; Tang L.-M.; Chen K.; Feng Y. Role of Defects on the Catalytic Property of 2D Black Arsenic for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Appl. Phys. Express 2019, 12, 075502 10.7567/1882-0786/ab27dc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Furthmüller J. Efficiency of Ab-Initio Total Energy Calculations for Metals and Semiconductors Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996, 6, 15–50. 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Furthmüller J. Efficient Iterative Schemes for Ab Initio Total-Energy Calculations Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Joubert D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X. X.; Feng Y. X.; Liao L.; Chen Q. J.; Wang D.; Tang L. M.; Chen K. Strain Tuning of Electronic Properties of Various Dimension Elemental Tellurium with Broken Screw Symmetry. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2018, 30, 125001 10.1088/1361-648X/aaaea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Chen K.; Li X. Z.; Wang E.; Zhang L. Hydrogen Induced Contrasting Modes of Initial Nucleations of Graphene on Transition Metal Surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 034704 10.1063/1.4974178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue X. X.; Feng Y.; Chen K.; Zhang L. The Vertical Growth of MoS2 Layers at the Initial Stage of CVD from First-Principles. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 134704 10.1063/1.5010996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nørskov J. K.; Rossmeisl J.; Logadottir A.; Lindqvist L.; Kitchin J. R.; Bligaard T.; Jonsson H. Origin of the Overpotential for Oxygen Reduction at a Fuel-Cell Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 17886–17892. 10.1021/jp047349j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Man I. C.; Su H.-Y.; Calle-Vallejo F.; Hansen H. A.; Martínez J. I.; Inoglu N. G.; Kitchin J.; Jaramillo T. F.; Nørskov J. K.; Rossmeisl J. Universality in Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysis on Oxide Surfaces. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 1159–1165. 10.1002/cctc.201000397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noerskov J. K.; Bligaard T.; Logadottir A.; Kitchin J. R.; Chen J. G.; Pandelov S.; Stimming U.; Trends in the Exchange Current for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 36, J23. [Google Scholar]

- Hajiyani H.; Pentcheva R. Influence of 3d, 4d, and 5d Dopants on the Oxygen Evolution Reaction at Alpha-Fe2O3(0001) under Dark and Illumination Conditions. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 124709 10.1063/1.5143236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P. Hydrogénations et déshydrogénations par catalyse. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1911, 44, 1984–2001. 10.1002/CBER.19110440303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Wei Z.; Gou X. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Dual-Doped Graphene/Carbon Nanosheets as Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction and Evolution. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4133–4142. 10.1021/acscatal.5b00601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlin Y.; Jaramillo T. F. A Bifunctional Nonprecious Metal Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction and Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13612–13614. 10.1021/ja104587v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.; Wang H. F.; Chen X.; Li B. Q.; Hou T. Z.; Zhang B.; Zhang Q.; Titirici M. M.; Wei F. Topological Defects in Metal-Free Nanocarbon for Oxygen Electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6845–6851. 10.1002/adma.201601406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman G.; Uberuaga B. P.; Jónsson H. A Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Saddle Points and Minimum Energy Paths. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9901–9904. 10.1063/1.1329672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J.; Jaramillo T. F.; Bonde J.; Chorkendorff I. B.; Norskov J. K. Computational High-Throughput Screening of Electrocatalytic Materials for Hydrogen Evolution. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 909–913. 10.1038/nmat1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y.; Zheng Y.; Davey K.; Qiao S.-Z. Activity Origin and Catalyst Design Principles For electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution on Heteroatom-Doped graphene. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16130 10.1038/nenergy.2016.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Yang X.; Pei W.; Liu N.; Zhao J. Heterostructures of Mxenes and N-Doped Graphene as Highly Active Bifunctional Electrocatalysts. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 10876–10883. 10.1039/C8NR01090K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Chen A.; Chen L.; Zhou Z. 2D Materials Bridging Experiments and Computations for Electro/Photocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 2003841 10.1002/aenm.202003841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.