Abstract

In recent years, the federal administration has ramped up efforts to curb and enforce immigration laws, in essence redefining how immigration, particularly in the Latinx population, is viewed and dealt with in the United States. The aim of the present study was to examine Latinx family strengths in relation to youth externalizing behavior, considering the modifying impacts of the current anti-immigration environment. Data were drawn from a study of 547 mother–adolescent dyads. Adolescents were 12.80 years old (SD = 1.03) on average and 55% female; 88% were U.S. born. Adolescents completed measures of family strengths, including parental behavioral control, parental support, and respeto. They also reported on their own externalizing behavior. Mothers completed a measure of their affective and behavioral responses to immigration actions and news. Results showed that in families of mothers who reported adverse responses to the immigration context, parental behavioral control, parental support (boys only), and respeto were more strongly related to youth behavior. Results align with the family compensatory effects model, in which strengths at the family level help to offset adversities outside the home. Discussion focuses on ways to support families in establishing and maintaining high levels of protective processes and on the need to challenge anti-immigration rhetoric, practices, and policies that undermine healthy youth development in the Latinx population.

Keywords: immigration context, parental behavioral control, parental warmth, respeto, youth externalizing behavior

Resumen

En años recientes, la administración federal ha cambiado las leyes de inmigración, en efecto creando e intensificando un contexto antiinmigratorio para los Latinos en los EEUU. El proposito de este estudio fue la investigación de los procesos familiares en relación al comportamiento de adolescentes, tomando en cuenta los efectos del contexto de inmigración. Utilizamos datos de 547 madres e hijos. Los adolescentes tenian un promedio de 12.80 años (SD = 1.03), 55% eran hembra, y 88% nacieron en los EEUU. Los adolescentes reportaron sobre los procesos familiares (control, apoyo y respeto) y su propio comportamiento. Las madres reportaron sobre los efectos del contexto de inmigración. Segun los resultados, los efectos del contexto de inmigración, el control de madres, el apoyo hacia los hijos (solo para varones), y el respeto fueron relacionados con el comportamiento de los adolescentes. Los resultados muestran que las caracteristicas familiares ayudan a los adolescentes a superar la adversidad. Es importante apoyar a los padres Latinos a establecer y mantener procesos familiares que protejen sus hijos. A la vez, es importante desafiar la retórica, las practicas y las leyes antiinmigratorias que debilitan la salud de los adolescentes.

Scholarship on Latinx youth and families has burgeoned in recent decades, grounded in ecological theories that highlight the complex and unique ways in which human development is shaped by cultural processes within diverse families, which themselves are embedded in and shaped by broader systemic forces (García Coll et al., 1996; White, Nair, & Bradley, 2018). Culture at the family level is reflected across domains including household structures, daily activities, childcare and educational decisions, socialization goals, and parenting practices, all undergirded by cultural values (Calzada, Fernandez, & Cortes, 2010; Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2013; Hughes et al., 2006). Outside the home, systems may challenge, redefine, or support family processes depending on a host of neighborhood and school factors like socioeconomic resources, neighborhood cohesion, and ethnic composition (White, Knight, Jensen, & Gonzales, 2018). Less attention has been given to exo- and macrolevel influences such as the immigration policies and rhetoric directed at Latinx populations in the United States. Such research is critical given the drastic rise in nationalist and anti-immigrant sentiment, policies, and practices observed in recent history (Torres, Santiago, Walts, & Richards, 2018). The goal of the present study is to examine family processes in relation to externalizing behavior in Latinx youth, considering the role of the immigration environment.

The Immigration Environment for Latinx Families

Since early 2017, the federal administration has ramped up efforts to curb and enforce immigration laws, in essence redefining how immigration is viewed and dealt with in the United States (Schmidt, 2019). Through restrictions on admissions, threats to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, detentions, family separations at the border, and deportations, federal and local authorities have caused clear and direct psychological harm to those targeted. Research with families that are legally vulnerable shows that anti-immigrant policies contribute to financial strain, housing instability, limited social support, psychological distress in parents, compromised parenting practices, and strained parent–child relationships at the family level (e.g., Allen, Cisneros, & Tellez, 2015; Brabeck & Xu, 2010; Dreby, 2012; Rubio-Hernandez & Ayón, 2016).

While these government practices target a relatively modest segment of the Latinx population (i.e. 13% of Latinx are undocumented; Passel & Cohn, 2019), anti-immigrant policies have implications for the broader population (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017). Immigration policies have created a culture of uncertainty and fear for Latinxs regardless of individual documentation status (Barajas-Gonzalez, Ayón, & Torres, 2018). A recent study found that all Latinx parents, including U.S. citizens, experienced the adverse effects of anti-immigration policies (Roche, Vaquera, White, & Rivera, 2018). Worries about family separation, for example, were reported by 88% of undocumented parents and 84% of parents with temporary protected status, but also by 57% of parents with permanent resident status and 22% of U.S. citizen parents. These kinds of worries and fears appear to contribute to psychological distress indicated by clinical symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as avoidance behaviors, such as delaying prenatal care or primary care visits, that compromise health (Novak, Geronimus, & Martinez-Cardoso, 2017; Rhodes et al., 2015; Roche et al., 2018). In a review of the literature, Philbin and colleagues (2018) concluded that immigration policies amplify health disparities by a) limiting access to resources including housing, education, fair-wage jobs, social services, and health services, and b) increasing stress due to experiences of racism.

The population-wide impacts documented in the literature appear to reflect the cascading effects by which macrolevel forces reify systems (e.g., health, education) of exclusion (Ayón, Valencia-Garcia, & Kim, 2017). Public discourse, such as political and pundit debates over immigration, dehumanizes immigrant populations by framing migration as a problem to be solved and linking concepts of danger and invasion (i.e. criminality) with the act of migration (Menjívar & Abrego, 2012). Anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, in turn, contribute to negative stereotyped beliefs about and discriminatory actions toward all Latinxs, irrespective of legal status (Androff et al., 2011; Aranda, Menjivar, & Donato, 2014; Ayón & Becerra, 2013; Rhodes et al., 2015; Rojas-Flores, Clements, Hwang Koo, & London, 2017; Stacey, Carbone-Lopez, & Rosenfeld, 2011). Experiences of exclusion and discrimination increase risk for negative outcomes including externalizing behaviors (Torres et al., 2018).

Externalizing Behavior in Latinx Youth

Though adolescent externalizing problems, characterized by defiance, aggression and rule-breaking, represent a critical public health issue for the U.S. population broadly (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2009), there is evidence that the costs and consequences of externalizing behavior may be greater for youth of color, including Latinxs. National survey data indicate that relative to other pan-ethnic groups, Latinx youth self-report high rates of problem behaviors including getting in arguments and physical fights, carrying a weapon, and skipping school (Kann et al., 2018). As described below, such behavior problems appear to reflect, at least in part, structural and systemic forces that marginalize and oppress immigrant and minority youth. Nonetheless, for Latinx and other youth of color, the implications of these behaviors can be severe.

First, the mental health service system is less accessible to Latinx populations (Alegria, Green, McLaughlin, & Loder, 2015), and without treatment, externalizing problems may worsen (Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Second, the juvenile justice system is more likely to arrest and convict youth of color (relative to White youth) for behaviors like carrying a weapon, diverting youth from educational and occupational opportunities and increasing the risk of ongoing involvement in the criminal justice system (Loeber & Farrington, 2001). Third, immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) is more likely to become aware of and intentionally pursue those who are deemed a threat to public safety (https://www.ice.gov/ero), increasing the risk that Latinx youth and/or their parents will be detained due to their immigrant status. In light of these considerations, it is imperative to study predictors of externalizing problems so that we can best support efforts to prevent youth from engaging in these costly behaviors to begin with.

Family Strengths and Youth Functioning

Parental responsiveness (e.g., warmth, support) and demandingness (e.g., expectations, monitoring) have long been considered central tasks of parenting that shape youth outcomes. During adolescence, high levels of behavior control, such as monitoring youth activities outside the home, are especially important for development. Research with Latinx youth show a negative association between monitoring levels and their engagement in substance use, sexual activity, and antisocial behavior (Killoren & Deutsch, 2014; Merianos, King, Vidourek, & Nabors, 2015). Behavior control reflects a reciprocal process that includes parent solicitation of information and youth communication regarding their activities and whereabouts. Parental support refers to responsive, encouraging, and affectionate behaviors that foster the parent–child relationship. High levels of support have positive effects on Latinx youth generally, and on externalizing behaviors specifically (Eamon & Mulder, 2005; White, Knight, et al., 2018; White, Roosa, & Zeiders, 2012). A study with Mexican-origin youth found that demanding and responsive parenting was associated with the most favorable mental health trajectories from late childhood to late adolescence (White, Liu, Gonzales, Knight, & Tein, 2016).

Traditional cultural values are increasingly recognized as family strengths. Respeto, or a polite deference to authority that, in childhood, manifests as a duty to obey parents and elders, represents a core cultural Latinx value (Calzada et al., 2010). Scholars theorize that respeto serves to maintain interpersonal harmony and reinforce hierarchical parent–child relationships in families (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006). Endorsement of respeto is high among Latinx youth, even throughout adolescence, and Latinx youth who endorse higher levels of respeto report less family conflict and more family cohesion (Knight et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Baezconde-Garbanati, Ritt-Olson, & Soto, 2012; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013). Moreover, evidence shows that endorsement of respeto by youth and young adults is negatively associated with depression, unsafe sexual activity, and substance use (Escobedo, Allem, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Unger, 2018; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2012, 2013; Ma et al., 2014; Soto et al., 2011). It is not known whether respeto is associated with externalizing behavior among youth experiencing negative impacts related to the immigration environment, but research with Black youth suggests this may be the case. In Black families that fear police brutality, youth are encouraged to behave in ways that will go undetected by staying quiet, calm, and respectful (Thomas & Blackmon, 2015; Whitaker & Snell, 2016). This form of socialization has been described as critical to survival even as it is potentially disempowering to youth (Whitaker & Snell, 2016).

Family Strengths in the Context of Immigration Adversity

There are a number of ways in which family processes may influence youth functioning depending on broader contextual influences. According to the family compensatory effects model, and consistent with models of resilience, family strengths may have the greatest protective effect for youth living in adversity (Roche & Leventhal, 2009; White et al., 2012). One aspect of contextual adversity that has been examined previously is residence in high-risk, under resourced, or disordered neighborhood environments. For example, a study with diverse school-age children found that restrictive (i.e. high in monitoring and behavioral limits) and supportive (i.e. high in warmth and engagement) parenting showed the strongest inverse associations with depression and academic problems in low-quality neighborhoods (Dearing, 2004). Similarly, Roche and Leventhal (2009) found that low levels of parental behavior control and family routines were most strongly associated with sexual onset among Latinx and African American youth in neighborhoods characterized by disorder. A study with Mexican-origin youth found that family cohesion was related to fewer internalizing problems in high-risk, but not low-risk, neighborhoods (White et al., 2012).

Past studies have examined youth outcomes in relation to immigration adversity and found a host of negative impacts such as appetite and sleep changes, feelings of anxiety and avoidance, depressive symptoms, withdrawn and aggressive behavior, and trauma (e.g., Allen et al., 2015; Brabeck & Xu, 2010; Dreby, 2012; Giano et al., 2019; Rubio-Hernandez & Ayón, 2016; Zayas, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Yoon, & Rey, 2015). For example, using a longitudinal design and controlling for baseline functioning, Roche and colleagues (2020) showed increased odds of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and clinical behavior problems over time among Latinx youth who had experienced the detention or deportation of a family member. In light of the mounting evidence that anti-immigrant policies undermine mental health in Latinx youth, it is important to examine the potential benefits of family strengths for youth living in the context of immigration adversity.

The Present Study

The aim of the present study is to examine family strengths in relation to youth externalizing behavior, considering the modifying impacts of the immigration environment. With a sample of 547 mother-adolescent dyads, we expected that parental behavioral control, parental support, and youth endorsement of respeto would all be associated with lower levels of youth externalizing behaviors. Consistent with the notion of compensatory effects, however, we hypothesized that the benefits of family strengths would be strongest in families experiencing a more adverse immigration environment. We also considered moderation by youth gender in light of numerous studies showing differential associations between parenting and externalizing behaviors for boys relative to girls (e.g., Nelson et al., 2017). These findings, coupled with theory indicating a greater salience of social bonds and relationships for adolescent females’ adjustment, suggest that parental support, behavioral control, and respeto may be more strongly tied to externalizing symptoms among adolescent females, as compared to males (Fagan, Lee Van Horn, Antaramian, & Hawkins, 2011). Finally, models control for youth age, nativity, maternal education, and household structure, as these are important correlates of Latinx parenting and youth problem behaviors (Halgunseth, 2019).

Method

Sampling and Procedure

Data derive from Pathways to Health/Caminos al Bienestar (“Caminos”), a study of Latinx youth and mothers in suburban Atlanta, GA. Caminos identified 1,105 students listed as “Hispanic” on 2017–18 middle school enrollment lists to screen for eligibility. Participants were then selected at random, stratifying on grade (6th, 7th, 8th) and gender, and evenly distributed across schools that had a “low,” “moderate,” or “high” concentration of Latinx students. Exclusion criteria included having a severe emotional or learning disability indicated by an individualized education plan, being unable to read either English or Spanish, not being Latinx (or a related term) based on self-report, being a sibling of a previously selected participant, or having an age outside the typical range for the school grade.

The final sample included 547 youth who provided assent and had parental consent. Response rates are based on the reachable parents and adolescents because eligibility could not be determined without this contact. The response rate among eligible youth whose parents were contacted and provided permission (n = 839) was 65.2%, and the response rate among eligible youth contacted (n = 574) was 95.3%. An intentionally missing study design was used for the collection of mother survey data. A mother or mother-figure was also selected for inclusion in the study for a randomly selected 50% of youth (Little & Rhemtulla, 2013). This design ensured a cost-effective approach to collecting dyad data without compromising the quality of mother data. Among the 386 mothers who were eligible (i.e. Latina; spoke Spanish or English) and reachable, 271 (49.5% of youth participants) completed Time 1 parent surveys, an 83.9% response rate.

The present study used Time 1 data collected in 2018. All participants completed surveys in English or Spanish; the majority of youth (>95%) completed the survey in English, whereas most mothers (80%) completed the survey in Spanish. Youth surveys were self-administered in school and online, and mother surveys were conducted over the telephone by trained bilingual, bicultural research staff. Responses were recorded using the Qualtrics software program (Qualtrics XM Research Core Survey Software, 2018). Informed consent was obtained via parents’ written or oral permission and adolescents’ written informed assent. For mother surveys, oral parental consent was obtained from mothers. Investigators obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health and institutional review board approval.

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The sample included slightly more females, and youth were, on average, 12.80 (SD = 1.03) years old. About two thirds of youth lived with both parents, and just over two thirds of youth were second-generation immigrants. Mothers were born in Latin America or the United States, and about half were born in Mexico. Average maternal education was high school completion.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Characteristics (N = 547)

| Variables | n (%) or M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Youth gender | ||

| Male | 244 (44.60) | |

| Female | 303 (55.40) | |

| Youth nativity | ||

| U.S. born | 482 (88.10) | |

| Foreign born | 65 (11.90) | |

| Youth age | 12.80 (1.03) | 11–16 |

| Household structure | ||

| Two parents | 368 (67.30) | |

| Stepparent | 73 (13.30) | |

| One or no parent | 106 (19.40) | |

| Mother’s education | 3.13 (1.63) | 1–6 |

| Parental behavioral control | 4.39 (0.03) | 1–5 |

| Parental support | 4.02 (0.04) | 1–5 |

| Respeto | 4.43 (0.02) | 1–5 |

| Responses to immigration actions and news | 2.62 (0.04) | 1–5 |

| Youth externalizing behaviors | 0.31 (0.01) | 0–2 |

Measures

Demographic characteristics.

Youth reported their age in years, gender (0 = male; 1 = female); and mother’s educational attainment (1 = 8th grade or less; 2 = some high school; 3 = completed high school; 4 = some college; 5 = completed college; 6 = graduate or professional school after college). Using youth reports of their country of birth, we created dummy-coded variables to indicate their nativity (0 = foreign born; 1 = U.S. born). Youth reports of household relatives also were used to create dummy variables indicating: two-parent (the omitted reference group); stepparent; or single parent (a small number of youth living with kin only—no parent—were included in the single-parent category).

Responses to immigration actions and news.

A modified version of the Political Climate Scale (Roche et al., 2018; White, Knight, et al., 2018) was administered to mothers to assess responses to immigration actions and news (e.g., worry family members may get separated; warned child to avoid authorities). The 16-item scale begins with: “As you know, there have been stories in the news about immigrants and immigration, and there have been official actions affecting immigrants and other people. We would like to know whether these news stories and official actions have affected you or your family over the past year” (response categories: 1 = never/almost never, 2 = not very often, 3 = sometimes, 4 = a lot of the time, and 5 = always or almost always). The scale was developed with and for Spanish- and English-speakers. Higher mean scores indicated greater responses to immigration actions and news (M = 2.62, SD = .04, α = .87; note that due to the small number of English surveys (n = 54), we were not able to calculate alphas separately by language of administration).

Youth perceptions of family strengths.

Parental support was assessed by eight items from the Children’s Reports of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRBPI; Schaefer, 1965) indicating adolescent perceptions of the parent’s warmth and acceptance (“speaks to you in a warm, friendly voice,” “tells/shows you that she likes you just the way you are”). Response categories ranged from 1 = almost never or never to 5 = almost always or always (M = 4.02, SD = .04, α = .93). Parental behavioral control (Stattin & Kerr, 2000) was assessed by seven items indicating parental limits on youths’ behaviors and inquiry about youth activities and whereabouts (e.g., “Do you need to tell your parent where you are going after school,” “If you have been out late at night, do you have to tell your parent what you did and whom you were with”). Response categories ranged from 1 = almost never or never to 5 = almost always or always (M = 4.39, SD = .03, α = .86). Respeto was assessed using eight items from the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010) indicating youth values on respect for, and obedience to, parents and other adults (e.g., “Children should never question their parents’ decisions,” “Children should always be polite when speaking to any adult”). Response categories ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (M = 4.43, SD = .02, α = .86). The support and respeto scales have been validated in Spanish in past studies (Knight et al., 2010; Nair, White, Knight, & Roosa, 2009), and the behavioral control scale was translated by the present study team using a double-translation and double back-translation method combined with a review team approach. In the present study sample, we were not able to calculate alphas separately by language of administration due to the small number of Spanish surveys (n = 25).

Youth externalizing symptoms.

Externalizing symptoms were assessed using two sub-scales from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991): rule breaking (e.g., “I break rules at home, school, or elsewhere,” α = .79) and aggression (e.g., “I get into many fights,” α = .84). The total externalizing symptoms scale was reliable (α = .90), with a mean score of 0.31 (SD = .01). For each item, youth indicated if the symptom was not true (0), somewhat or sometimes true (1), or very true or often true (2) over the past six months. The CBCL is a widely used child behavior rating scale that is available from the developers in Spanish.

Analytic Plan

Initial analyses included examining amounts and patterns of missing data and conducting best practice multiple imputation for missing data. The intentionally missing data, stemming from the 50% of the mothers not being surveyed randomly, was categorized as missing at random (MAR) because mothers who participated in surveys included fewer U.S. born mothers and had younger adolescents when compared to mothers who were sampled but difficult to reach for obtaining consent or who were reached but did not provide consent. Data missing due to item nonresponse ranged from 1.5 to 4.5%, except maternal education (16%). Missing due to item nonresponse was assumed to be MAR based on low correlations with variables in the data set. Exploratory analyses of missing data were run using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., 2016). Missing data were imputed using the PcAux package in R (Lang & Little, 2018) because it optimizes recovery of auxiliary information under MCAR, MAR, and MNAR (Enders, 2010); here the entire data frame is reduced into principal components for use in the multiple imputation procedure (Howard, Rhemtulla, & Little, 2015). Analyses were run using 200 multiply imputed data sets produced using the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) package in R (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011). For data imputation, we extracted 85 linear principle components (60% variance explained) and one nonlinear principle component (96% variance explained) to use as auxiliary variables (Howard et al., 2015). We created a grand mean data set (averaged estimates across 200 imputed data sets; Lang & Little, 2014). Validity for latent variables—parental support, parental behavioral control, respeto, youth externalizing symptoms—was determined using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), which corrects for item measurement error in relationships between survey items and the latent constructs. We used parceling techniques whereby the average score of at least two survey items was calculated and included in measurement models as indicators predicted by a latent variable. Facet representative parceling was used for externalizing symptoms where each parcel consists of items related to the two dimensions of the construct, rule breaking and aggressive behaviors. For the remaining unidimensional latent constructs, we used a balanced parceling technique, assigning items to a parcel based on high and low correlations or loadings (Little, Rhemtulla, Gibson, & Schoemann, 2013). When compared to single-item indicators, parceled indicators attain greater reliability, more communality, a higher ratio of common-to-unique factor variance, fewer distributional violations, and less chance for correlated residuals or dual loadings. The scale for each latent construct was set using effects coding; factor loadings were constrained to have a value of 1 and intercepts were constrained to have a value of 0 on average (Little et al., 2013). Measurement models were deemed to fit underlying data adequately when the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than .08, and the comparative fit index (CFI) was greater than .90 (Little, 2013).

Measurement invariance for each latent construct across youth gender and nativity was examined by assessing the change in model fit when proceeding from configural (no invariance in parameter estimates) to weak (invariant loadings) to strong (invariant intercepts) invariance. Evidence for invariance was apparent if the change in CFI was less than .01; the value of the RMSEA remained within the confidence interval of the preceding model (Little, 2013). Structural models examined associations between family strengths and youth externalizing behavior as well as the ways in which maternal responses to immigration actions and news modified these associations. These moderating effects were examined in separate models including a two-way interaction term between a family strengths variable (behavioral control, support, respeto) and maternal responses to immigration actions and news. Externalizing symptoms also were regressed on the study’s sociodemographic variables. Change in model fit statistics were also examined from multiple group models run to identify statistically significant gender differences in structural model pathways (results available from authors). Structural models included rescaling constructs for latent variables in order to estimate the constructs on a standardized metric; rescaling constructs into what are known as phantom variables entails simple reparameterizations of model estimates that convert variances to standard deviations and covariances into correlational metric (Little, 2013). All SEM work was conducted using Mplus 8.15 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012–2017).

Due to underestimated standard errors in results derived from analyses of the grand mean imputed data set, we determined statistical significance of parameter estimates by examining the change in F-statistic for analyses run outside of a latent variable framework and by a change in the chi-square statistic for latent variable models (Lang & Little, 2014). In the case of interaction effects, we used bootstrapping methods to test statistical significance. In this iterative process, we compute the estimates for interaction effects a total of k = 20,000 times. Confidence intervals (CIs) were computed for each interaction effect. In cases where the 95% CIs did not include zero, the interaction effect was determined to be statistically significant. Significant gender differences in interaction effects were evidenced by point estimates for males and females not falling within the other’s 95% CI (Little, 2013).

Results

Measurement Models

The CFA results indicated a good fit for the overall measurement model (χ2 = 96.23, df = 67; RMSEA = .028, 90% CI [.014, −.040]; CFI = .993). As shown in Table 2, standardized factor loadings, significant at p < .001, for the three parceled items for parental support, parental behavioral control, and respeto were consistently strong for all constructs. Changes in model fit statistics indicated measurement equivalence across both gender and nativity (results available from the authors).

Table 2.

Unstandardized (Standard Error) and Standardized Factor Loadings for Final Measurement Model

| Parameter estimate | b (SE) | β |

|---|---|---|

| Parental behavioral control | ||

| Parcel 1: need to tell parent how spent late evening out + need parent permission to go out on weekend night | 1.09 (.03) | .86 |

| Parcel 2: need parent permission to go out on school night + need parent permission to go out on weekend evening + need to tell parent how spend money | .84 (.03) | .78 |

| Parcel 3: need to tell parent how spend evenings out + need to tell parent where going after school | 1.07 (.03) | .90 |

| Parental support | ||

| Parcel 1: sees your good points more than your faults + speaks to you in a warm, friendly voice + tells/shows you that she likes you just the way you are | .94 (.02) | .88 |

| Parcel 2: cheers you up when you are sad + is able to make you feel better when upset | 1.08 (.02) | .88 |

| Parcel 3: makes you feel better after talking over your worries + has a good time with you + understands your problems and worries | .99 (.02) | .93 |

| Respeto | ||

| Parcel 1: understand parents have final say for family decisions + on best behavior when visiting friends/family + respect parents | .95 (.03) | .85 |

| Parcel 2: honor parents + never question parents’ decisions + respect adult relatives | 1.06 (.03) | .81 |

| Parcel 3: be polite when speaking to adults + follow parents’ rules even if think unfair | .99 (.03) | .79 |

| Externalizing behaviors | ||

| Parcel 1: aggressive syndrome (13 items) | .97 (.04) | .90 |

| Parcel 2: rule-breaking syndrome (17 items) | 1.03 (.04) | .82 |

| Responses to immigration actions and news | ||

| Parcel 1: worry about contact with police/authorities + changed daily routines + considered leaving U.S. + affected child at school + talked to child about changing their behavior, like where they hang out + warned child be careful of authorities | 1.09 (.03) | .88 |

| Parcel 2: harder to keep/find a job + harder to imagine hope for better job/making more money + worry about family separation + avoid seeking medical help or services + been stopped, questioned, harassed | .92 (.03) | .78 |

| Parcel 3: worry harder for child to finish school + worry difficult for child to get a job + parent negatively affected + children in general negatively affected + child misses school because afraid | .99 (.03) | .74 |

Note. Fit statistics for measurement model included: χ2 = 96.23, df = 67, p < .05; RMSEA = .028, 90 % CI [.014, −.040]; CFI = .993. All parameter estimates significant at p < .001.

Bivariate Associations

Table 3 presents the results of the bivariate correlation matrix for family strengths, externalizing behaviors, and responses to immigration action and news. As shown, parental behavioral control was positively associated with parental support and respeto, and respeto was positively associated with parental support. Family strengths—parental behavioral control, parental support, and respeto — were each inversely related to externalizing behaviors. While responses to immigration action and news was significantly associated with more externalizing behaviors, it was not significantly associated with any family strengths.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental behavioral control | — | |||

| 2. Parental support | .38*** | — | ||

| 3. Respeto | .40*** | .51*** | — | |

| 4. Externalizing behaviors | −.37*** | −.42*** | −.42*** | — |

| 5. Responses to immigration actions and news | .02 | −.02 | .05 | .11* |

Note. Values shown are standardized estimates based on latent variables.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Structural Model: Main Effects

Results from multiple group models across gender indicated a significant improvement in model fit when comparing the model that was fully constrained across gender to the model allowing pathways from parental support to externalizing and from parental behavioral control to externalizing to differ by gender (Δχ2(2) = 10.02, p < .01). Results from the final structural model testing main effects (see Table 4) indicated that externalizing behaviors were significantly lower among youth reporting greater respeto, among boys reporting greater parental behavioral control, and among girls reporting greater parental support. Structural model results also indicated that maternal reports of greater responses to immigration actions and news were positively associated with externalizing behaviors. Results for demographic variables indicated that externalizing behaviors were positively associated with youth age, household structure, and youth nativity status. The final structural model demonstrated strong model fit (χ2 (334) = 528.73, p < .00001, RMSEA = .044 (90% CI [.037, .052]); CFI = .96).

Table 4.

Main Effects of Sociodemographic Characteristics and Family Strengths on Youth Externalizing Symptomology (N = 547)

| Parameter estimatea | B or βb | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Youth age | 0.10* | .04 |

| Mother’s education | 0.00 | .05 |

| Household structure | ||

| Stepparent | 0.08* | .04 |

| Single parent | 0.01 | .04 |

| School Latinx concentration | ||

| Low | −0.06 | .05 |

| Middle | 0.05 | .05 |

| U.S. born | 0.12** | .04 |

| Responses to immigration actions & news | 0.14* | .05 |

| Parental behavioral control | male: −0.37*** | .09 |

| female: −0.13 | .07 | |

| Parental support | male: −0.03 | .10 |

| female: −0.38*** | .08 | |

| Respeto | −0.27*** | .07 |

Results derive from multiple group models for youth gender.

Standardized betas provided for sociodemographic variables; unstandardized betas provided for latent constructs (responses to immigration action & news; parental behavioral control; parental support) based on the use of phantom variables for measuring latent constructs.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

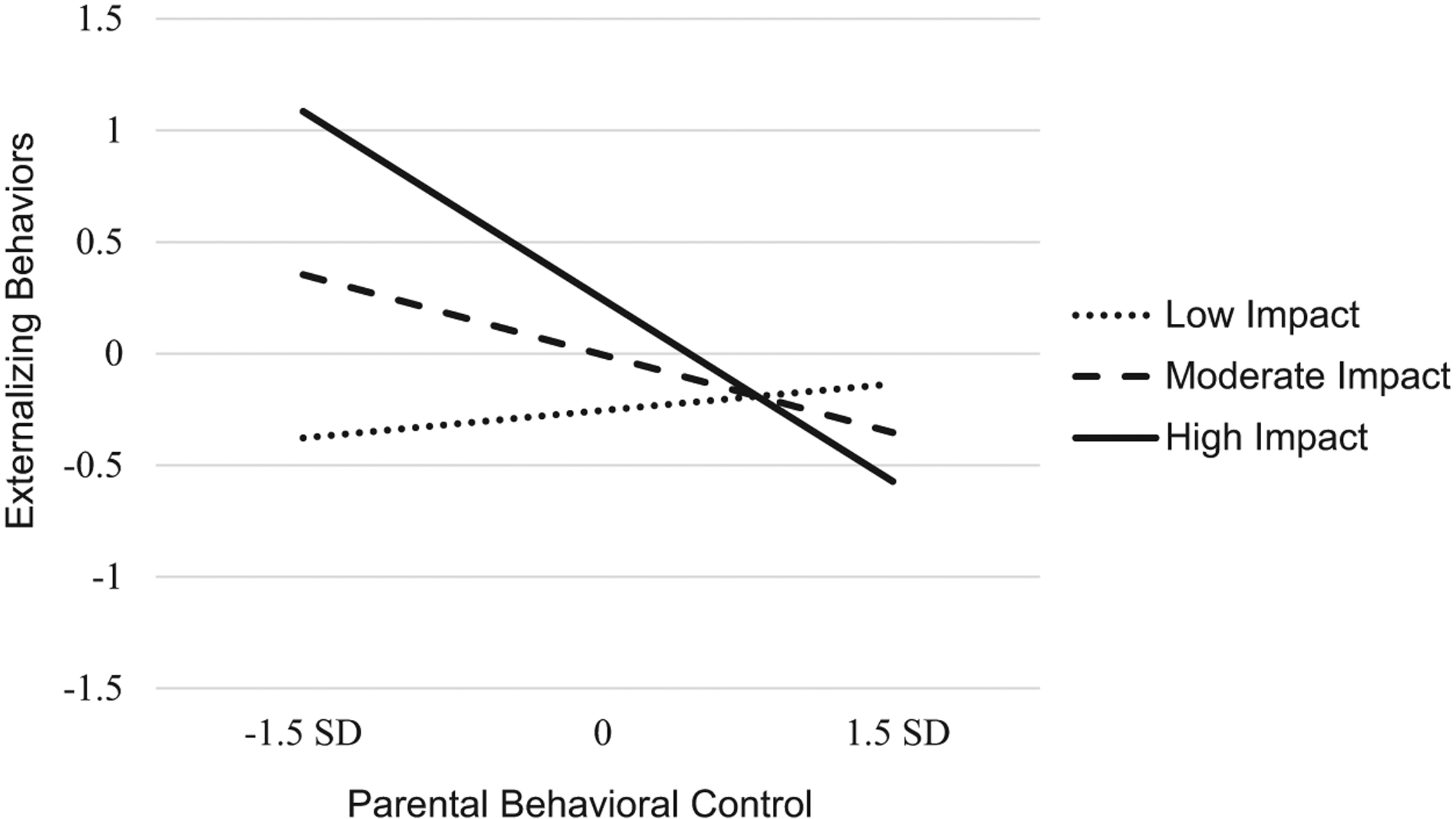

Structural Model: Interactions Effects

Results from structural models testing interaction effects indicated that pathways from parental behavioral control, parental support, and respeto to lower levels of externalizing behavior differed according to mother-reported responses to immigration action and news. As shown in Figure 1, lower levels of parental behavioral control were more strongly associated with higher externalizing behavior scores when mothers reported higher impact in response to immigration actions and news (behavioral control × immigration responses: β =−.21, 95% CI [−.37, −.04], p < .05). Second, results from bootstrap estimations indicated that, among boys, there was a significant interaction between immigration responses and parental support (parental support × immigration responses: β =−.28, 95% CI [−.46, −.10], p < .01). As shown in Figure 2, parental support was more strongly associated with less externalizing behaviors for boys whose mothers reported higher impact in response to immigration actions and news. Finally, as shown in Figure 3, the association between respeto and externalizing behavior was stronger when mothers reported higher impact in response to immigration (Respeto × Immigration Responses: β =−.18, 95% CI [−.33, −.03], p < .05).

Figure 1.

Adolescent externalizing behavior by parental behavioral control and responses to immigration actions and news. n = 547.

Figure 2.

Adolescent Externalizing Behavior by Parental Support and Responses to Immigration Actions & News, Males. n = 244.

Figure 3.

Adolescent Externalizing Behavior by Respeto and Responses to Immigration Actions & News. n = 547.

Discussion

In recent history, immigration policies have become increasingly restrictive and punitive, limiting opportunities for immigrants to obtain permission to enter and remain in the United States and criminalizing entry and residence in the United States without official documentation (Schmidt, 2019). Anti-immigration efforts have been broadly publicized and have sparked considerable debate, filtering down to individual intolerance of all Latinos (Stacey et al., 2011). The present study examined whether family strengths were differentially associated with Latinx youth externalizing behavior problems in the context of an adverse immigration environment and found that parental behavioral control, parental support, and respeto may be especially important to the development of youth faced with this type of adversity.

The Compensatory Effects of Parenting in Immigrant Latinx Families

We first examined maternal responses to immigration news and events on families in a sample of early adolescents from various countries of origin (including Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador). While we did not assess legal vulnerability, past research shows that resident and citizen parents are not immune to these corollaries (Roche et al., 2018). As a whole, mothers reported somewhat frequent worries related to financial stability, job security, access to services, family separation, interaction with authorities, and the psychological impact of the immigration climate on themselves and their children. We then examined the modifying influence of an adverse immigration environment on the association between family strengths and youth externalizing behaviors and found evidence of moderation. These facets of family functioning had the strongest negative associations with youth externalizing behavior problems when mothers reported more frequent worries, behavioral changes, and adversities tied to immigration events. Parents are known to develop adaptive strategies to deal with adversity, for example by using high levels of control when living in dangerous neighborhoods or shifting their behavioral routines to avoid risks related to immigration enforcement (Ayón, 2018; Roche et al., 2018; White et al., 2016). Our findings on the compensatory effects of family strengths add to the robust literature on resilience by documenting the importance of parenting and respeto especially within the context of risk.

Considering the ways in which immigration events are believed to impact families (e.g., worries and avoidance behaviors), it is not surprising that behavioral control, or mothers’ efforts to ensure that they know and sanction what their children are doing outside the home, are critically important. Parental control is undergirded by the cultural value of respeto, which reinforces expectations and norms that youth defer to parental authority (Calzada et al., 2010). When endorsed by youth, studies show that high levels of cultural values like respeto help Latinx youth balance the desire for autonomy with the need to prioritize and defer to family in adolescence (Knight et al., 2010; Villalobos Solís, Smetana, & Tasopoulos-Chan, 2017). In families with low behavioral control and in the absence of respeto, youth may be more likely to act out and engage in rule-breaking outside the home. To the extent that youth participate in behaviors that may draw the attention of authorities, stress and conflict is likely amplified for families who are worried about immigration enforcement.

The positive effects of parental support were also as expected. Mothers’ support, as a reflection of the affective quality of the mother–child relationship, has been found to predict self-esteem in youth, which may be especially important for youth exposed to racially motivated slights and insults, or microaggressions (Bulanda & Majumdar, 2009). According to James (2016), explicit expressions of warmth, love, and acceptance from parents reassure children of color who are devalued outside of the home of their humanity and dignity. Interestingly, the protective effects of parental support were limited to boys in families with high responses to immigration changes. This gender-specific effect may reflect the nature of Latinx stereotypes, which are largely based on criminality most often associated with males (e.g., gang member, rapist; Shinnar, 2008). For example, a recent media analysis found that immigrant men are predominantly portrayed as drug lords and human traffickers, playing into beliefs that Latinx men are dangerous (The Opportunity Agenda, 2017). Thus, parental support may be more important for counteracting negative societal perceptions among boys than girls. It is also important to note gender differences in the expression of distress, with internalizing behaviors being more salient for girls (Kann et al., 2018). Future work should examine whether family strengths play a protective role against anxiety and depression for girls in particular.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

There are a number of limitations that must be considered in interpreting findings from the present study. First, we were unable to examine temporal relations between study variables because of our reliance on cross-sectional data. Second, we did not have sufficient power to examine families based on country of origin or youth nativity status, potentially obscuring important sources of heterogeneity. Similarly, we did not assess the legal vulnerability of families, precluding analysis of how parenting and its association with youth externalizing behavior may differ based on status (undocumented, temporary, permanent, citizen). Future research should look at longer-term impacts in and across specific subgroups to better understand how the immigration environment affects families based on their social and demographic background. For example, some evidence suggests that some Latinx youth become more politically aware (e.g., watching news, attending protests) in the face of social injustice and that political engagement may be especially salient among the second generation (Flores-González, 2010; Wray-Lake et al., 2018). More research is needed to explore the circumstances under which youth show resilience when faced with oppressive systemic forces.

Future work should also consider other variables that may influence parenting and youth outcomes in Latinx families living in an anti-immigrant climate. Research shows that immigration stressors cause distress in parents, making it harder for them to engage in effective parenting such as monitoring and consistent discipline (Ayón et al., 2017; Brabeck & Xu, 2010). Over time, experiences of discrimination and acculturation stress have been shown to cause spillover effects that decrease positive parenting, including warmth and monitoring, in immigrant families (Miao, Costigan, & MacDonald, 2018). Similarly, scholars describe the ongoing strain related to a “culture script of silence” regarding immigration issues that is meant to ensure survival but that, in some families, limits parent–child interactions and engagement (Gulbas & Zayas, 2017). In other words, while strong support and appropriate behavior control appear to function as family strengths that protect youth from the negative impacts of an anti-immigrant climate, these practices may be difficult to maintain in this context. Further, it may be that youth with high levels of respeto are more likely to accept parental directives even when parents provide limited rationale for the sake of maintaining silence.

Engaging in positive parenting is unquestionably a central task facing Latinx families of adolescents, as externalizing behavior problems has potentially dire implications for the entire family. Early adolescence marks the developmental stage when, at least by mainstream U.S. norms, youth seek increased autonomy, and parents must balance these developmental needs with safety for themselves and their child. In many ways, this dilemma mirrors that of Black families who must act as “super-parents” to protect their children without societal safety nets, even as they contend with the chronic stressors stemming from racism (Jarrett, 1999). Prevention programs that empower Latinx parents to navigate these processes successfully may help families adapt to the ongoing challenges of a hostile immigrant environment. For example, Parra and colleagues documented positive impacts of an adapted version of Parent Management Training with Latinx parents of middle schoolers that included an explicit focus on how immigration experiences shape parenting practices (Parra et al., 2018). At the same time, it is imperative that we advocate for a shift toward more humane immigration policies and practices for the health and safety of Latinx youth in the United States.

Public Significance Statement.

Anti-immigration actions and news have an adverse effect on Latinx families. High levels of parental behavioral control, parental warmth, and the cultural value of respeto function as family strengths that protect youth from the negative impacts of anti-immigrant rhetoric and practice.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen M. Roche received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01-HD090232-01A1).

Contributor Information

Esther J. Calzada, University of Texas at Austin.

Kathleen M. Roche, George Washington University

Rebecca M. B. White, Arizona State University.

Roushanac Partovi, George Washington University.

Todd D. Little, Texas Tech University.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist 4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://aseba.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, & Loder S (2015). Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S. William T. Grant Foundation. Retrieved from https://philanthropynewyork.org/sites/default/files/resources/Disparities_in_child_and_adolescent_health.pdf

- Allen B, Cisneros EM, & Tellez A (2015). The children left behind: The impact of parental deportation on mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 386–392. 10.1007/s10826-013-9848-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Androff D, Ayón C, Becerra D, Gurrola M, Salas L, Krysik J, … Segal E (2011). U.S. immigration policy and immigrant children’s well-being: The impact of policy shifts. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 38, 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda E, Menjivar C, & Donato KM (2014). The spillover consequences of an enforcement-first U.S. immigration regime. American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 1687–1695. 10.1177/0002764214537264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C (2018). “Vivimos en Jaula de Oro”: The impact of state-level legislation on immigrant Latino families. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16, 351–371. 10.1080/15562948.2017.1306151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, & Becerra D (2013). Mexican immigrant families under siege: The impact of anti-immigrant policies, discrimination. Advances in Social Work, 14, 206–228. 10.18060/2692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Valencia-Garcia D, & Kim SH (2017). Latino immigrant families and restrictive immigration climate: Perceived experiences with discrimination, threat to family, social exclusion, children’s vulnerability, and related factors. Race and Social Problems, 9, 300–312. 10.1007/s12552-017-9215-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barajas-Gonzalez RG, Ayón C, & Torres F (2018). Applying a community violence framework to understand the impact of immigration enforcement threat on Latino children. Social Policy Report, 31, 1–24. 10.1002/sop2.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck K, & Xu Q (2010). The impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children and families: A quantitative exploration. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32, 341–361. 10.1177/0739986310374053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda RE, & Majumdar D (2009). Parent-child relations and adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, & Cortes DE (2010). Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 77–86. 10.1037/a0016071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda C, & Yoshikawa H (2013). Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 1696–1724. 10.1177/0192513X12460218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E (2004). The developmental implications of restrictive and supportive parenting across neighborhoods and ethnicities: Exceptions are the rule. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25, 555–575. 10.1016/j.appdev.2004.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (2003). A biopsycho-social model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371. 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreby J (2012). The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 829–845. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00989.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK, & Mulder C (2005). Predicting antisocial behavior among Latino young adolescents: An ecological systems analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75, 117–127. 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo P, Allem JP, Baezconde-Garbanati L, & Unger JB (2018). Cultural values associated with substance use among Hispanic emerging adults in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors, 77, 267–271. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Lee Van Horn M, Antaramian S, & Hawkins JD (2011). How do families matter? Age and gender differences in family influences on delinquency and drug use. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 9, 150–170. 10.1177/1541204010377748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-González N (2010). Immigrants, citizens, or both? The second generation in the immigrant rights marches. In Pallares A & Flores-González N (Eds.), Marcha!: Latino Chicago and the Immigrant Rights Movement (pp. 198–214). Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Vázquez García H (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. 10.2307/1131600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giano Z, Anderson M, Shreffler KM, Cox RB, Merten MJ, & Gallus KL (2019). Immigration-related arrest, parental documentation status, and depressive symptoms among early adolescent Latinos. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. Advance online publication. 10.1037/cdp0000299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas LE, & Zayas LH (2017). Exploring the effects of U.S. immigration enforcement on the well-being of citizen-children in Mexican immigrant families. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 3, 53–69. 10.7758/rsf.2017.3.4.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L (2019). Latino and Latin American parenting. In Bornstein M (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 4. Social Conditions and Applied Parenting (3rd ed., pp. 24–56). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. 10.4324/9780429398995-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, & Rudy D (2006). Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development, 77, 1282–1297. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Prins SJ, Flake M, Philbin M, Frazer MS, Hagen D, & Hirsch J (2017). Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 169–178. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard WJ, Rhemtulla M, & Little TD (2015). Using principal components as auxiliary variables in missing data estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 285–299. 10.1080/00273171.2014.999267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corp IBM. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- James AG (2016). Parenting and protecting: Advocating microprotections through loving and supporting Black parent–child relationships. NCFR Report. Retrieved from https://www.ncfr.org/ncfr-report/focus/family-focus-cultural-seachange-and-families/parenting-and-protecting-advocating [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RL (1999). Successful parenting in high-risk neighborhoods. The Future of Children, 9, 45–50. 10.2307/1602704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, … Ethier KA (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 67 (No. SS–8). 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killoren SE, & Deutsch AR (2014). A longitudinal examination of parenting processes and Latino youth’s risky sexual behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1982–1993. 10.1007/s10964-013-0053-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Basilio CD, Cham H, Gonzales NA, Liu Y, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2014). Trajectories of Mexican American and Main-stream Cultural Values Among Mexican American Adolescents. J Youth Adolescence, 43, 2012–2027. 10.1007/s10964-013-9983-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, … Updegraff KA (2010). The Mexican-American cultural values scales for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30, 444–481. 10.1177/0272431609338178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KM, & Little TD (2014). The supermatrix technique: A simple framework for hypothesis testing with missing data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 461–470. 10.1177/0165025413514326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KM, & Little TD (2018). Principled missing data treatments. Prevention Science, 19, 284–294. 10.1007/s11121-016-0644-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, & Rhemtulla M (2013). Planned missing data designs for developmental researchers. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 199–204. 10.1111/cdep.12043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, & Schoemann AM (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18, 285–300. 10.1037/a0033266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, & Farrington DP (2001). Child delinquents: Development, intervention, and service needs. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 10.4135/9781452229089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, & Soto D (2012). Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1350–1365. 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2013). A longitudinal analysis of Hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family, and discrimination. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 957–968. 10.1093/ntr/nts204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Malcolm LR, Diaz-Albertini K, Klinoff VA, Leeder E, Barrientos S, & Kibler JL (2014). Latino cultural values as protective factors against sexual risks among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 1215–1225. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C, & Abrego L (2012). Legal violence: Immigration law and the lives of Central American immigrants. American Journal of Sociology, 117, 1380–1421. 10.1086/663575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merianos AL, King KA, Vidourek RA, & Nabors LA (2015). Recent alcohol use and binge drinking based on authoritative parenting among Hispanic youth nationwide. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1966–1976. 10.1007/s10826-014-9996-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao SW, Costigan C, & MacDonald S (2018). Spillover of stress to Chinese Canadian immigrants’ parenting: Impact of acculturation and parent–child stressors. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9, 190–199. 10.1037/aap0000105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2012–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth edition. Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nair RL, White RMB, Knight GP, & Roosa MW (2009). Cross-language measurement equivalence of parenting measures for use with Mexican American populations. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 680–689. 10.1037/a0016142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KM, Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon L, Eckert TL, Park A, Vanable PA, … Carey MP (2017). Gender differences in relations among perceived family characteristics and risky health behaviors in urban adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 51, 416–422. 10.1007/s12160-016-9865-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak NL, Geronimus AT, & Martinez-Cardoso AM (2017). Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46, 839–849. 10.1093/ije/dyw346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra CR, López ZG, Leija SG, Maas MK, Villa M, Zamudio E, … Domenech Rodríguez MM (2018). A culturally adapted intervention for Mexican-origin parents of adolescents: The need to overtly address culture and discrimination in evidence-based practice. Family Process. 10.1111/famp.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel J, & Cohn D (2019). Mexicans decline to less than half the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population for the first time. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/us-unauthorized-immigrant-population-2017/ [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hirsch JS (2018). State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 29–38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics XM Research Core Survey Software. (2018). [Computer software]. Provo, UT: Qualtrics. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, Song E, Alonzo J, Downs M, … Hall MA (2015). The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 329–337. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, & Leventhal T (2009). Beyond neighborhood poverty: Family management, neighborhood disorder, and adolescents’ early sexual onset. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 819–827. 10.1037/a0016554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, Vaquera E, White RMB, & Rivera MI (2018). Impacts of immigration actions and news and the psychological distress of U.S. Latino parents raising adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62, 525–531. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche KM, White RBM, Lambert SF, Schulenberg J, Calzada EJ, Kuperminc GP, & Little TD (2020). Association of family member detention or deportation with Latino or Latina adolescents’ later risks of suicidal ideation, alcohol use, and externalizing problems. Pediatrics, 174, 478–486. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Flores L, Clements ML, Hwang Koo J, & London J (2017). Trauma and psychological distress in Latino citizen children following parental detention and deportation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, 352–361. 10.1037/tra0000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Hernandez SP, & Ayón C (2016). Pobrecitos los Niños: The emotional impact of anti-immigration policies on Latino children. Children and Youth Services Review, 60, 20–26. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424. 10.2307/1126465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PW (2019). An overview and critique of U.S. immigration and asylum policies in the Trump era. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 7, 92–102. 10.1177/2331502419866203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar RS (2008). Coping with negative social identity: The case of Mexican immigrants. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148, 553–576. 10.3200/SOCP.148.5.553-576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Black DS, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2011). Cultural values associated with substance use among Hispanic adolescents in southern California. Substance Use & Misuse, 46, 1223–1233. 10.3109/10826084.2011.567366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey M, Carbone-Lopez K, & Rosenfeld R (2011). Demographic change and ethnically motivated crime: The impact of immigration on anti-Hispanic hate crime in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 27, 278–298. 10.1177/1043986211412560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, & Kerr M (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085. 10.1111/1467-8624.00210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Opportunity Agenda. (2017). Power of pop: Analyzing portrayals of immigrants in popular television. Retrieved on September 5, 2019 from https://www.opportunityagenda.org/explore/resources-publications/power-pop/executive-summary

- Thomas AJ, & Blackmon SM (2015). The influence of the Trayvon Martin shooting on racial socialization practices of African American parents. Journal of Black Psychology, 41, 75–89. 10.1177/0095798414563610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres SA, Santiago CD, Walts KK, & Richards MH (2018). Immigration policy, practices, and procedures: The impact on the mental health of Mexican and Central American youth and families. American Psychologist, 73, 843–854. 10.1037/amp0000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S, & Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos Solís M, Smetana JG, & Tasopoulos-Chan M (2017). Evaluations of conflicts between Latino values and autonomy desires among Puerto Rican adolescents. Child Development, 88, 1581–1597. 10.1111/cdev.12687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker TR, & Snell CL (2016). Parenting while powerless: Consequences of “the talk”. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26, 303–309. 10.1080/10911359.2015.1127736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Knight GP, Jensen M, & Gonzales NA (2018). Ethnic socialization in neighborhood contexts: Implications for ethnic attitude and identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents. Child Development, 89, 1004–1021. 10.1111/cdev.12772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Liu Y, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, & Tein JY (2016). Neighborhood qualification of the association between parenting and problem behavior trajectories among Mexican-origin father-adolescent dyads. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 927–946. 10.1111/jora.12245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Nair RL, & Bradley RH (2018). Theorizing the benefits and costs of adaptive cultures for development. American Psychologist, 73, 727–739. 10.1037/amp0000237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Roosa MW, & Zeiders KH (2012). Neighborhood and family intersections: Prospective implications for Mexican American adolescents’ mental health. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 793–804. 10.1037/a0029426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray-Lake L, Wells R, Alvis L, Delgado S, Syvertsen AK, & Metzger A (2018). Being a Latinx adolescent under a Trump presidency: Analysis of Latinx youth’s reactions to immigration politics. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 192–204. 10.1016/j.childy-outh.2018.02.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Yoon H, & Rey GN (2015). The distress of citizen-children with detained and deported parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3213–3223. 10.1007/s10826-015-0124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]