Resumo

A fibrilação atrial é a arritmia sustentada mais comum na prática clínica com predileção pelas faixas etárias mais avançadas. Com o envelhecimento populacional, as projeções para as próximas décadas são alarmantes. Além de sua importância epidemiológica, a fibrilação atrial é destacada por suas repercussões clínicas, incluindo fenômenos tromboembólicos, hospitalizações e maior taxa de mortalidade. Seu mecanismo fisiopatológico é complexo, envolvendo uma associação de fatores hemodinâmicos, estruturais, eletrofisiológicos e autonômicos. Desde os anos 1990, o estudo Framingham em análises multivariadas já demonstrou que, além da idade, a presença de hipertensão, diabetes, insuficiência cardíaca e doença valvar é preditor independente dessa normalidade do ritmo. Entretanto, recentemente, vários outros fatores de risco estão sendo implicados no aumento do número de casos de fibrilação atrial, tais como sedentarismo, obesidade, anormalidades do sono, tabagismo e uso excessivo de álcool. Além disso, as mudanças na qualidade de vida apontam para uma redução na recorrência de fibrilação atrial, tornando-se uma nova estratégia para o tratamento de excelência dessa arritmia cardíaca. A abordagem terapêutica envolve um amplo conhecimento do estado de saúde e hábitos do paciente, e compreende quatro pilares principais: mudança de hábitos de vida e tratamento rigoroso de fatores de risco; prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos; controle da frequência; e controle do ritmo. Pela dimensão de fatores envolvidos no cuidado ao paciente portador de fibrilação atrial, ações integradas com equipes multiprofissionais estão associadas aos melhores resultados clínicos.

Keywords: Fibrilação Atrial/fisiopatologia, Arritmias Cardíacas/fisiopatologia, Fatores de Risco, Obesidade, Sedentarismo, Terapia Combinada

Introdução

A fibrilação atrial (FA) é caracterizada pela completa desorganização da atividade elétrica atrial e consequente perda da sístole atrial com padrão eletrocardiográfico característico e de fácil reconhecimento. Entretanto, o diagnóstico é desafiador, uma vez que muitos pacientes se apresentam assintomáticos ou com sintomas fugazes, dificultando o registro da arritmia. É a arritmia sustentada mais comum na prática clínica afetando 3% da população adulta, com predileção para faixas etárias mais avançadas.1 Com o envelhecimento populacional, as projeções para as próximas décadas são alarmantes. Estima-se que o número de pacientes portadores de FA com idade superior a 55 anos será mais que o dobro em 2060, o que consumirá grande quantidade de recursos dos cofres públicos.2 Além da importância epidemiológica, a FA é destacada pelas suas repercussões clínicas, incluindo os fenômenos tromboembólicos, com aumento, em média, de 4 vezes a chance de um acidente vascular cerebral (AVC), além de ser associada ao maior risco de mortalidade por todas as causas e outras importantes condições, como insuficiência cardíaca.3 , 4A incidência ajustada para idade e a prevalência de FA é menor nas mulheres em comparação com os homens; contudo, não acontece com a morbimortalidade. A FA está associada ao maior risco relativo para mortalidade por todas as causas, AVC, mortalidade cardiovascular, eventos cardíacos e insuficiência cardíaca no sexo feminino.5

Pacientes com essa anormalidade do ritmo também são mais vulneráveis a hospitalizações. Em uma recente metanálise incluindo 35 estudos e 311.314 pacientes, a incidência de admissão hospitalar foi de 43,7/100 pessoas ao ano. As doenças cardiovasculares representam as maiores causas de hospitalizações; no entanto, as causas não cardiovasculares também são frequentes nesse grupo de pacientes, como câncer e doenças pulmonares.6

Este artigo tem por objetivo revisar aspectos fisiopatológicos, fatores de risco e bases para o tratamento. As diretrizes para prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos e a ablação por cateter serão abordadas em outros manuscritos.

Mecanismos fisiopatológicos

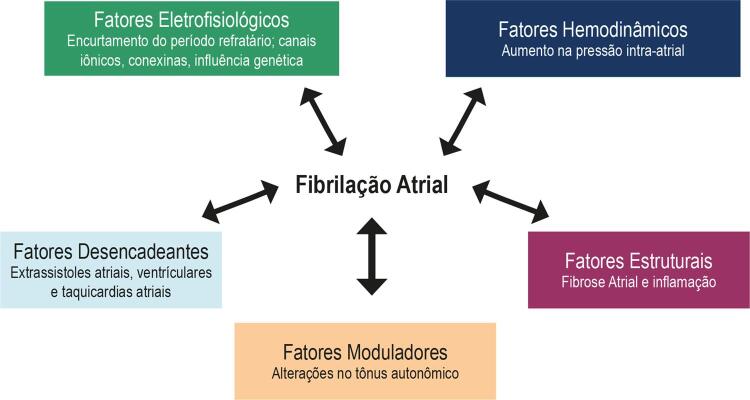

Várias alterações fisiopatológicas levam à ocorrência de fibrilação, incluindo fatores hemodinâmicos, eletrofisiológicos, estruturais, autonômicos (moduladores), além de fatores desencadeantes representados pelas extrassístoles e taquicardias atriais ( Figura 1 ). Essas variam desde polimorfismos genéticos a modificações macroscópicas da estrutura do átrio, interferindo na atividade elétrica das células e resultando em desorganização da atividade elétrica atrial.

Figura 1. – Fatores fisiopatológicos implicados na gênese de fibrilação atrial.

As propriedades elétricas do miocárdio são controladas por canais iônicos presentes na membrana celular. A ativação das células depende basicamente de canais de sódio, cálcio e potássio. O período refratário da célula depende, grosseiramente, do tempo entre a ativação da célula e o retorno do potencial de ação ao nível inicial. O aumento das correntes de influxo iônico (cálcio e sódio) prolonga o período refratário celular, e o aumento da corrente de efluxo (potássio) resulta no seu encurtamento. Outro componente importante na eletrofisiologia normal do coração são as conexinas, que são proteínas presentes nas junções entre os cardiomiócitos, responsáveis pela permeabilidade iônica entre as células, permitindo a propagação normal do impulso elétrico.7 Na FA, ocorrem alterações desses componentes da eletrofisiologia normal das células, o que se convencionou chamar de remodelamento elétrico. A sua forma mais comum decorre da entrada acentuada de cálcio nas células que se despolarizam com frequência aumentada. Esse aumento leva à inativação de correntes de cálcio e aumento de correntes de potássio, que resultam no encurtamento da duração do potencial de ação e aumento da vulnerabilidade à FA, além de favorecer a recorrência precoce após a cardioversão e a progressão de formas paroxísticas para formas mais persistentes da arritmia.8 Fatores genéticos podem estar relacionados a defeitos dos canais iônicos, e podem predispor à ocorrência de FA. Formas familiares da arritmia, embora sejam situações raras e heterogêneas, são bem descritas na literatura.9 , 10 O papel da genética na FA está sendo estudado, sendo uma corrente promissora na busca, cada vez mais atual, de formas de tratamento personalizado.

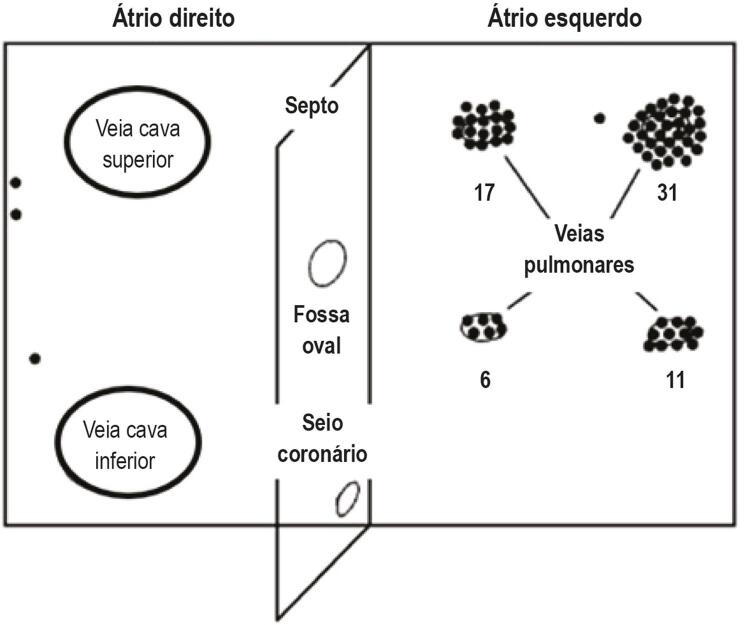

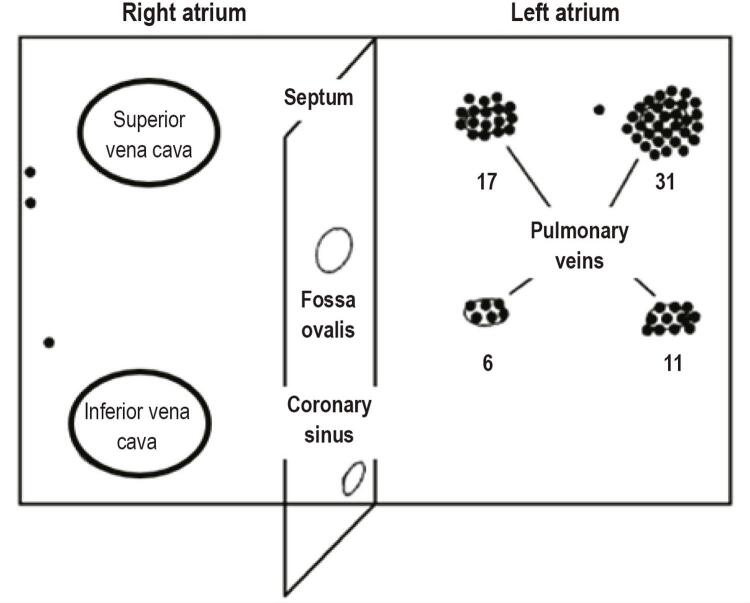

Atualmente, as teorias mais aceitas para o início da arritmia e a sua manutenção são a presença de focos ectópicos como deflagradores da arritmia e a reentrada como fator de manutenção. Estudos iniciais já indicavam que a aplicação tópica de substâncias estimulantes no átrio, como a aconitina (alcaloide capaz de ocasionar bradicardia e hipotensão), no átrio originava taquicardia atrial rápida, que, por sua vez, induzia a FA.11 O estudo crucial no entendimento da origem focal da FA foi conduzido por Haïssaguerre et al.,12 no qual os autores, mapeando a atividade elétrica atrial em pacientes com FA, observaram focos ectópicos precoces que precediam a ocorrência da arritmia provenientes, principalmente, do interior das veias pulmonares ( Figura 2 ).

Figura 2. – Focos deflagradores de fibrilação atrial em vários pontos nos átrios (pontos escuros) provenientes, predominantemente, das veias pulmonares. Adaptada de Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC et al.12 Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339(10):659–66.

Enquanto a atividade focal é necessária para o início da FA, um substrato atrial propício para a sua manutenção é igualmente importante. Características estruturais, anatômicas e eletrofisiológicas são fundamentais para a ocorrência e a manutenção de circuitos de reentrada, que são tidos, atualmente, como fundamentais na manutenção da arritmia. A reentrada pode ser anatômica (com obstáculos criando zonas de condução lenta, como fibrose) ou funcional (refratariedade heterogênea, decorrente de propagação errática da frente de onda de ativação elétrica atrial). Essas condições aumentam a probabilidade de ocorrência de múltiplas ondas simultâneas de reentrada, facilitando a perpetuação da FA.13

A atividade autonômica também desempenha papel importante no início e na manutenção da FA.14 A ativação vagal pode alterar correntes de potássio dependentes da acetilcolina, com consequente redução da duração do potencial de ação podendo, assim, estabilizar circuitos de reentrada.15 Além disso, a ativação adrenérgica pode provocar o acúmulo de cálcio intracelular, o que pode deflagrar a arritmia.

Mudanças na estrutura do miocárdio atrial, particularmente a fibrose, separam as fibras musculares, interferindo na continuidade da condução do impulso elétrico, resultando em redução da velocidade de condução, que é fundamental para a reentrada.16 A fibrose leva à progressão da FA, podendo ser um alvo terapêutico17 e um preditor da resposta ao tratamento.18 Embora fatores eletrofisiológicos, incluindo o remodelamento elétrico, e morfológicos, como a fibrose e a dilatação atrial (remodelamento estrutural), sejam considerados os principais fatores envolvidos na fisiopatologia da FA, vem crescendo a quantidade de evidências que processos infecciosos ou inflamatórios podem permear e unir essas duas situações. Um estudo de caso controle com 56.870 participantes analisou a associação entre infecção pelo virus influenza, vacinação e risco de FA. Os autores demonstraram que a infeção aumentou o risco para o desenvolvimento da arritmia, ao passo que a vacinação apresentou efeito protetor em diferentes grupos de pacientes.19 A presença de infiltrado inflamatório, necrose celular e fibrose intersticial em pacientes com FA sem doença cardíaca estrutural documentada é maior em comparação com um grupo de pacientes sem a arritmia.20 Esses estudos vêm demonstrando maior concentração de mediadores ou de marcadores de atividade inflamatória, como a interleucina 6 ou a proteína C-reativa ultrassensível em pacientes com FA.21

Fatores de risco para fibrilação atrial

O alto número de casos de FA encontrados na prática clínica não é apenas justificado pela idade – outros fatores contribuem para esse desfecho. Desde os anos 1990, o estudo Framingham em análises multivariadas já demonstrou que, além da idade, a presença de hipertensão, diabetes, insuficiência cardíaca e doença valvar é preditora independente dessa normalidade do ritmo.22 Entretanto, recentemente, vários outros fatores de risco são implicados, e as mudanças na qualidade de vida apontam para uma redução no número de casos de FA, tornando-se um novo pilar para o tratamento de excelência da FA.23

Obesidade e fibrilação atrial

A obesidade, definida como índice de massa corporal (IMC) superior a 30 kg/m2, demonstra uma clara associação com a ocorrência de FA. Uma importante metanálise incluindo 51 estudos e 626.603 indivíduos demonstrou um aumento no risco de FA em 29% para cada aumento de 5 unidades no IMC. Além disso, o risco de FA pós-operatória e pós-ablação também foi 10% e 13% maior, respectivamente, para o mesmo aumento de peso.24 A progressão da doença da forma paroxística para a forma permanente também é mais significativa nos pacientes obesos conforme documentação em estudo coorte longitudinal com 21 anos de acompanhamento.25 A genética também parece justificar essa associação. Um estudo com mais de 50.000 indivíduos demonstra que as variantes genéticas associadas ao IMC alto se correlacionam com a incidência de FA, sugerindo uma relação causal entre as duas condições.26

A partir desse conhecimento, vários estudos prospectivos foram conduzidos para demonstrar o impacto da redução do peso na recorrência de FA.27 - 32 O estudo Long-Term Effect of Goal-Directed Weight Management in an Atrial Fibrillation Cohort (LEGACY) incluiu 355 pacientes, que foram acompanhados por 4 anos e divididos em três grupos de acordo com a perda de peso no final do estudo. Uma probabilidade 6 vezes maior de estarem livres de anormalidades do ritmo foi observada nos participantes com perda e manutenção de peso superior a 10% do peso corporal em comparação com o grupo que perdeu menos de 3% ou ganhou peso no período.28 Outro estudo, prospectivo e observacional, avaliou 149 pacientes com IMC superior a 27 kg/m2submetidos à ablação de FA e a um programa de redução de peso presencial, demonstrando maior tempo de sobrevida livre de eventos arrítmicos em comparação com o grupo controle.27 Resultados semelhantes foram observados em um estudo prospectivo com 4.021 pacientes obesos, em ritmo sinusal e sem história prévia de arritmia. O grupo foi submetido a cirurgia bariátrica ou tratamento conservador. A perda de peso observada no grupo com intervenção foi associada à redução significativa no risco de FA.33

Por outro lado, em uma análise secundária do estudo Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) que avaliou pacientes com diabetes, a implementação de programa de perda de peso e atividade física não reduziu a ocorrência de FA.34 Um outro estudo populacional demonstra que a baixa massa magra também se relaciona com a presença de FA.35 Dessa forma, o real papel da distribuição de gordura corporal na arritmogênese ainda requer mais esclarecimentos, entretanto, é necessário reconhecer a obesidade como um fator de risco potencialmente modificável; e, em pacientes obesos e sobrepesos, a redução do peso em, pelo menos, 10% pode reduzir o risco de FA.

Apneia obstrutiva do sono

Apneia obstrutiva do sono (AOS) é caracterizada pela obstrução completa ou parcial, recorrente das vias aérea superiores durante o sono, resultando em períodos de apneia, dessaturação de oxi-hemoglobina e despertares noturnos frequentes. O reconhecimento dessa anormalidade do sono por parte dos cardiologistas tornou-se fundamental após as publicações demonstrando aumento na mortalidade cardiovascular nos pacientes com AOS não tratada.36 Vários fatores contribuem para o dano cardiovascular nesses pacientes e, possivelmente inúmeros mecanismos estejam envolvidos. Entretanto, três fatores principais merecem destaque: hipóxia intermitente, despertares frequentes e alterações na pressão intratorácica. Essas alterações acabam por desencadear hiperatividade do sistema nervoso simpático; disfunção endotelial e inflamação.37 - 40 A ativação simpática observada nesses pacientes é um importante fator que, em parte, justifica a elevada prevalência de arritmias cardíacas nessa população, incluindo a FA. Além disso, a AOS pode prejudicar o funcionamento do átrio esquerdo. Estudos com ecocardiografia tridimensional demonstraram disfunção e remodelamento atrial esquerdo com reversão após tratamento efetivo com pressão positiva.41 , 42

Em um estudo epidemiológico, a ocorrência de arritmias cardíacas noturnas foi mais frequente nos pacientes portadores de AOS grave, definida como índice de apneia/hiponeia (IAH) superior a 30 eventos/hora. A FA ocorreu em 1,65% dos casos de AOS grave e 0,2% nos controles (p=0,03).43 Em outra análise de pacientes em acompanhamento ambulatorial por FA crônica em um hospital terciário submetidos à polissonografia basal, 81,6% apresentavam AOS.44 De fato, AOS e FA são condições que compartilham fatores de risco como idade, sexo, obesidade, hipertensão e insuficiência cardíaca e, dessa forma, a demonstração de casualidade é desafiadora na literatura científica.

Em um estudo prospectivo45 com pacientes referidos para a cardioversão elétrica de FA/ flutter atrial, observou-se 82% de recorrência nos pacientes com AOS sem tratamento ou com tratamento inadequado e 42% de recorrência nos pacientes tratados (p=0,013). Além disso, no grupo de pacientes não tratados, a recorrência foi ainda maior entre os que apresentavam maior queda na saturação de oxigênio durante o evento de apneia (p=0,034). O tratamento da AOS reduz o risco de recorrência de FA não somente em pacientes submetidos à cardioversão elétrica, mas também após ablação por cateter. Em estudo com 426 pacientes submetidos ao isolamento elétrico das veias pulmonares, 62 pacientes apresentaram AOS confirmada pela polissonografia, sendo 32 pacientes usuários de CPAP e 30 pacientes sem tratamento. O uso do CPAP foi associado a uma maior taxa de sobrevida livre de FA quando comparado ao grupo sem o uso do CPAP (71,9% vs. 36,7%; p=0,01). Os autores concluíram que o tratamento com CPAP em pacientes portadores de AOS submetidos a tratamento percutâneo da FA melhora a recorrência da arritmia, e nos casos de AOS sem tratamento adequado, o isolamento elétrico tem pouco valor terapêutico.46 Uma metanálise foi, então, realizada para determinar o papel da AOS no paciente portador de FA submetido à ablação por cateter, concluindo-se que a presença de AOS é associada ao maior risco de recorrência de FA após ablação (RR 1,25, 95% CI 1,08 a 1,45, p=0,003).47

Concluindo, a presença de AOS é alta em pacientes com FA, e os dados atuais sugerem a presença de uma relação dose-resposta entre a gravidade da AOS e a recorrência de FA. O tratamento adequado dessa anormalidade do sono reduz a recorrência clínica de FA mesmo em pacientes submetidos à ablação por cateter. Dessa forma, a adequada investigação e o tratamento, caso necessários, são uma medida importante no manejo clínico desses pacientes.

Atividade física e fibrilação atrial

A inatividade física é um problema de saúde pública associado ao aumento das doenças cardiovasculares, insuficiência cardíaca, AVC, câncer, obesidade, diabetes tipo 2 e hipertensão.48 Sendo assim, propicia diversos fatores de risco para FA; contudo, mais recentemente, a literatura sugere a inatividade física como um fator de risco independente para FA. Cinco estudos populacionais demonstraram uma clara relação entre inatividade física e aumento do risco de FA.49 - 53 O estudo Cardiorespiratory Fitness on Arrhythmia Recurrence in Obese Individuals With Atrial Fibrillation (CARDIO-FIT) avaliou o impacto do ganho na capacidade cardiorrespiratória na ocorrência de FA em pacientes obesos e com sobrepeso.32 A cada equivalente metabólico adquirido durante o acompanhamento associou-se 9% de redução na recorrência da arritmia mesmo após a correção para o peso e fatores de risco. Um estudo com pacientes portadores de FA permanente submetidos a 12 semanas de exercício moderado a intenso foi relacionado a um aumento significativo da qualidade de vida quando comparado aos controles.54 Esses achados foram reprodutíveis por outros estudos randomizados e controlados, e a metanálise resultante demonstra que o treinamento físico melhora a capacidade ao esforço, qualidade de vida e fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo.55

Por outro lado, a relação entre atividade física e FA parece não ser linear, e sim uma curva em “u”, ou seja, os extremos – sedentarismo ou a prática extenuante de exercícios – aumentam o risco de FA.56 Vale lembrar que se trata da prática de exercícios com doses muito altas que excedem a recomendação e correspondem a uma porcentagem muito pequena da população. De forma interessante, o efeito do exercício intenso parece ser influenciado pelo sexo. Uma metanálise sobre o assunto demostrou que a atividade física vigorosa foi associada a um aumento significativo no risco em homens (OR: 3,30; 95% CI: 1,97 a 4,63; p=0,0002); entretanto, a atividade intensa foi relacionada a uma redução ainda mais significativa no risco de FA em mulheres.57 Os mecanismos envolvidos nessa diferença de comportamento ainda não estão totalmente esclarecidos, mas o fato é que a prática de atividade física moderada deve ser encorajada como prevenção, tratamento e melhora da qualidade de vida em todos os pacientes portadores de FA.

Outros potenciais fatores de risco modificáveis

Os efeitos do álcool no remodelamento atrial e no sistema nervoso autônomo podem, em parte, justificar a maior recorrência de FA nos indivíduos que utilizam álcool.58 Um estudo populacional com 109.230 participantes saudáveis e com consumo de álcool quantificado através de questionários demonstrou que, entre homens, o risco de FA aumentou de acordo com os quartis de uso semanal de álcool, sugerindo uma associação dose-resposta. O mesmo não foi verificado entre as mulheres.59 Mais interessante é a recente documentação de que a abstinência ao álcool se relaciona com a redução da recorrência de arritmia em pacientes com FA. Em um estudo multicêntrico, prospectivo e randomizado, realizado nos hospitais da Austrália, foram selecionados pacientes com consumo superior a 10 doses semanais e portadores de FA paroxística ou permanente, e que estavam em ritmo sinusal na avaliação basal. O grupo foi selecionado 1:1 para continuar com o uso habitual e a abstinência ao álcool. No total, 140 pacientes foram inclusos. A recorrência de FA ocorreu em 53% dos pacientes do grupo de abstinência e 73% no grupo controle. O tempo para a primeira recorrência foi maior no grupo de abstinência, e o numero total de eventos após 6 meses de acompanhamento foi significativamente menor nos que pararam com o uso em comparação aos controles.60

Os estudos que avaliaram a relação entre tabagismo e FA apresentaram resultados, inicialmente, discordantes; entretanto, uma metanálise incluindo 16 estudos prospectivos e 286.217 participantes demonstrou maior prevalência de FA entre os tabagistas, e a cessação do hábito foi associada à redução do risco.61 O tabagismo também influência negativamente os resultados do tratamento intervencionista da FA.62

Vale lembrar que o uso de altas doses de corticosteroides também foi relacionado ao aumento no risco de FA.63 Até o momento, não existem dados convincentes relacionando o uso de cafeína e o aumento do risco de FA; alguns estudos sugerem um modesto efeito protetor.64 O mesmo ocorre com transtornos de ansiedade. Em um recente estudo populacional com 37.402 adultos, não houve relação entre os sintomas de ansiedade ou depressão severa e FA.65

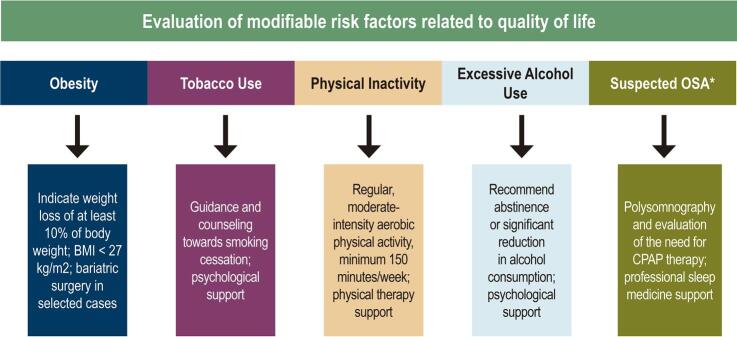

A Figura 3 resume os principais fatores de risco modificáveis relacionados à qualidade de vida.

Figura 3. – Fatores de risco para fibrilação atrial relacionados à qualidade de vida e suas respectivas orientações.

*Presença de ronco, sonolência excessiva diurna, fadiga, sono não reparador, alteração de memória

Bases terapêuticas para fibrilação atrial

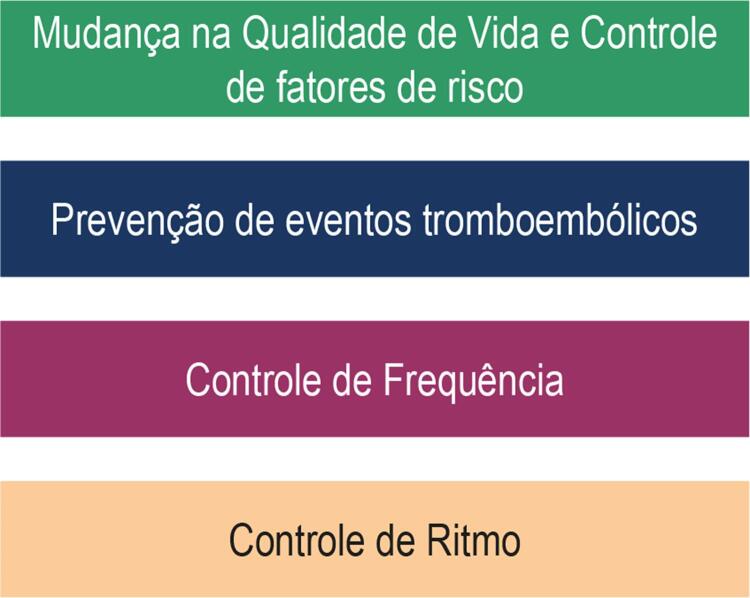

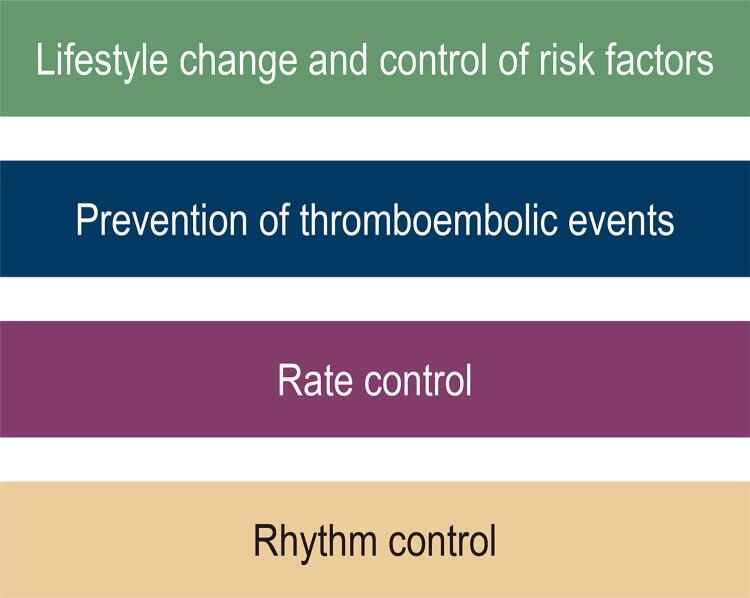

A abordagem terapêutica da FA envolve um amplo conhecimento do estado de saúde e hábitos do paciente e compreende quatro pilares principais: mudança de hábitos de vida e tratamento rigoroso de fatores de risco; prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos; controle da frequência; e controle do ritmo66 ( Figura 4 ). Serão mencionadas as bases terapêuticas relacionadas ao tratamento a longo prazo.

Figura 4. Pilares na abordagem terapêutica do paciente portador de fibrilação atrial.

Mudança na qualidade de vida e controle rigoroso de fatores de risco

Visa reduzir os fatores de risco modificáveis associados à qualidade de vida e ao tratamento rigoroso das comorbidades cardiovasculares. Dessa forma, além do controle do peso, tratamento do tabagismo, combate ao sedentarismo, uso comedido de álcool e otimização do padrão do sono, deve-se implementar o controle rigoroso de hipertensão arterial, diabetes e dislipidemia.

A hipertensão arterial é deletéria para o paciente com FA; além de constituir um fator de risco para eventos tromboembólicos, está associada a maior probabilidade de sangramento e recorrência dessa arritmia. Uma metanálise para prevenção de FA com o uso dos inibidores do sistema-renina angiotensina-aldosterona incluindo 87.048 pacientes provenientes de 23 estudos controlados e randomizados demonstrou que o uso desses medicamentos reduziu a probabilidade de ocorrência da arritmia em 33%, aproximadamente.67

Uma subanálise do estudo Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) avaliou as estratégias de controle intensivo da pressão arterial (PAS <120 mmHg) e controle convencional (PAS <140 mmHg) na ocorrência de FA. Após 5,2 anos de acompanhamento, foi observada uma redução de 26% no risco de FA no grupo de controle intensivo quando comparado com o controle convencional.68

Estudos demonstrando o benefício do controle da pressão arterial na redução do risco de FA foram reprodutíveis na literatura, incluindo pacientes com redução da fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo,69 , 70 mas alguns dados contraditórios também estão disponíveis.71 , 72 Possivelmente, outros fatores devem influenciar a prevenção primária e secundária de FA no paciente hipertenso, e estudos ainda são necessários para o melhor esclarecimento dessa relação.

Em uma metanálise envolvendo 7 estudos de coorte prospectivos e 4 estudos caso-controle, incluindo 108.703 casos de FA, demonstrou-se que a presença de diabetes está associada ao aumento no risco de desenvolver essa arritmia em 34%, mesmo após ajuste para fatores de confusão.73 Os mecanismos fisiopatológicos dessa relação ainda estão em investigação, mas possivelmente são múltiplos, incluindo os impactos do diabetes no sistema nervoso autônomo como na neuropatia diabética. Além disso, a hiperglicemia, isoladamente, é capaz de aumentar o tônus simpático e diminuir o tônus parassimpático, o que pode facilitar a ocorrência da arritmia. O remodelamento elétrico e estrutural atrial associado ao estresse oxidativo também corrobora a FA. 74 Entretanto, a relação entre diabetes e FA torna-se mais importante após a documentação de que o controle rigoroso da glicemia está associado a um melhor controle da FA. Em uma análise com 12.605 pacientes, o tratamento do diabetes por 5 anos foi associado a uma redução de aproximadamente 30% nos casos de FA.75

O diabetes também pode prejudicar a evolução dos pacientes com FA submetidos à ablação por cateter. Em um recente estudo multicêntrico incluindo 7 centros de alto volume na Europa, foi demonstrada uma maior recorrência de FA em 1 ano no grupo diabético.76 O controle da glicemia também parece influenciar favoravelmente a evolução de pacientes submetidos à ablação. Uma análise observacional de pacientes após ablação demonstrou que o uso da pioglitazona foi associado a menor necessidade de um segundo procedimento ablativo.77

A relação entre dislipidemia e FA ainda está em investigação. Uma análise observacional incluindo dois grandes bancos de dados (MESA e Framingham) demonstrou que altos níveis de HDL estavam associados ao menor risco de FA, ao passo que altos níveis de triglicérides estavam associados ao seu maior risco. Nenhuma relação foi encontrada com o LDL.78 Por outro lado, em um estudo prospectivo populacional, não houve associação entre os níveis de HDL, triglicérides e FA, e baixos níveis de LDL foram associados ao maior risco de FA. Além disso, o uso de fármacos hipolipemiantes não influenciou a ocorrência de FA.79

Na verdade, essas análises pontuais voltadas a um único fator de risco falham em demonstrar ações combinadas que, normalmente, são aplicadas na prática clínica. Para avaliar esse efeito, foram selecionados 281 pacientes consecutivos submetidos à ablação por cateter com múltiplos fatores de risco, e foi oferecido um programa de controle agressivo desses fatores. Os pacientes submetidos ao programa apresentaram significativamente maior redução de peso e melhor controle da pressão arterial, glicemia e dislipidemia. Como consequência, apresentaram uma maior redução na frequência, duração e sintomas de FA quando comparado com o grupo controle (p <0,001).80

Prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos

A FA é uma arritmia em que a avaliação de elegibilidade para prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos é mandatória. O uso do anticoagulante pode prevenir a maioria desses eventos e prolongar a sobrevida. O anticoagulante é superior ao tratamento com ácido acetilsalicílico isolado ou associado ao clopidogrel. Deve ser instituído a todos os pacientes portadores de FA, exceto quando classificados com muito baixo risco ou na vigência de alguma contraindicação ao uso dessa classe de medicamentos.81 A oclusão do apêndice atrial esquerdo constitui uma segunda alternativa para prevenção de eventos tromboembólicos no paciente com limitações ao uso dos anticoagulantes.

Controle da frequência cardíaca na fibrilação atrial

O controle da frequência cardíaca (FC) é parte integrante do tratamento do paciente com FA e, normalmente, é suficiente para reduzir os sintomas. O alvo terapêutico da FC ainda não está estabelecido na literatura. O estudo Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation ( RACE) selecionou 614 paciente com FA permanente elegíveis ao controle da frequência randomizados para estratégia leniente (FC repouso <110 bpm) ou estratégia rigorosa (FC de repouso <80 bpm e inferior a 110 bpm no exercício moderado). O objetivo foi avaliar as duas estratégias em relação ao desfecho combinado de morte cardiovascular, hospitalização por insuficiência cardíaca, AVC, embolia sistêmica, sangramento e arritmias graves. Após um seguimento de 2 anos, não houve diferenças significativas entre ambas as abordagens, e a frequência de sintomas e eventos adversos foi semelhante entre os dois grupos.82 Em análise subsequente, a estratégia leniente também não foi associada a remodelamento cardíaco adverso.83

Os fármacos utilizados para essa finalidade incluem: betabloqueadores, bloqueadores de canais de cálcio (diltiazen, verapamil), digoxina ou combinação dessas substâncias.84 Vale lembrar que a amiodarona pode ser utilizada em casos selecionados.

Os betabloqueadores são considerados os fármacos de primeira linha para o controle da FC no paciente com FA pela sua boa tolerabilidade, redução dos sintomas e melhora funcional. As opções terapêuticas, as doses e os efeitos colaterais mais comuns estão demonstrados na Tabela 1 . Vale lembrar que, no insucesso terapêutico, a combinação de medicamentos pode ser tentada. No paciente com disfunção ventricular, o betabloqueador permanece como fármaco de primeira escolha pelos seus conhecidos benefícios nessa população, e a associação com digoxina pode ser tentada, quando necessário. Os bloqueadores de canais de cálcio não devem ser usados no paciente com insuficiência cardíaca com fração de ejeção reduzida pelo seu efeito inotrópico negativo.84 Por fim, a ablação do nó atrioventricular seguida de estimulação cardíaca artificial constitui uma opção terapêutica nos casos de falência da estratégica medicamentosa.

Tabela 1. – Medicamentos utilizados para o controle da frequência cardíaca em pacientes portadores de fibrilação atrial. Adaptada de ESC Scientific Document Group.84 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893-2962.

| Drogas mais utilizadas para o controle da Frequência cardiaca em pacientes com FA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | Efeitos colaterais | ||

| Betabloqueadores | Metoprolol | 100 a 200mg/dia | letargia, dor de cabeça, edema, sistomas respiratórios, alterações gastrointestinais, tontura, bradicardia, bloqueio atrioventricular, hipotensão |

| Nebivolol | 2,5 a 10mg/dia | ||

| Bisoprolol | 1,25 a 20mg/dia | ||

| Carvedilol | 3,125 a 50mg/ duas vezes ao dia | ||

| Bloqueador canais de cácio | Diltiazen | 60mg/ três vezes ao dia (máximo 360mg/dia) | tontura, mal-estar, letargia, dor de cabeça, edema, alterações gastrointestinais, bloqueio atrioventricular, hipotensão |

| Verapamil | 40 a 120mg/ três vezes ao dia (máximo 480mg/dia) | ||

| Digoxina | 0,0625 a0,25mg/dia | Alteração gstrointestinal, tontura, embaçamento visual, dor de cabeça, efeitos pro-arritmicos em doses tóxicas | |

Controle do ritmo no paciente com fibrilação atrial

A reversão aguda ao ritmo sinusal e a terapia de manutenção do ritmo sinusal são importantes estratégias no manejo do paciente com FA. Apesar da manutenção do ritmo sinusal parecer, intuitivamente, superior quando comparada à estratégia de controle da frequência, não há forte documentação científica dessa afirmação. O estudo multicêntrico AFFIRM randomizou para essas duas estratégias de tratamento pacientes portadores de FA. Foram 4.060 pacientes com idade média de 69,7 anos, em que 70,8% apresentavam hipertensão arterial e 38,2%, doença da artéria coronária. Foram documentadas 310 mortes entre os pacientes alocados na estratégia de controle de frequência, e 356 nos pacientes com controle do ritmo após um seguimento médio de 3,5 anos com máximo de 6 anos (p=0,08). Além disso, o grupo submetido ao controle do ritmo apresentou mais efeitos adversos a medicações e um maior número de hospitalizações.85 Resultado semelhante foi observado no estudo RACE, em que o desfecho primário (morte e morbidade cardiovascular) ocorreu em 17,2% dos pacientes na estratégia controle da frequência e em 22,6% no controle do ritmo, após seguimento de 2,3 anos (p=0,11).86

Apesar de esses estudos não demonstrarem vantagem do controle do ritmo na sobrevida, alguns pontos devem ser mencionados. Uma subanálise do estudo AFFIRM utilizando modelos para determinar as relações entre sobrevida, variáveis clínicas basais e variáveis dependentes de tempo, demonstrou que a presença do ritmo sinusal e o uso de anticoagulante foram associados ao menor risco de morte. Por outro lado, o uso de fármacos antiarrítmicos foi associado ao aumento da mortalidade após ajuste para ritmo sinusal. Esses dados sugerem que o benefício do ritmo sinusal pode ter sido minimizado, e métodos alternativos para manutenção de ritmo sinusal com menores efeitos adversos podem ser promissores.87 Outra crítica a esses resultados é o tempo curto de seguimento. De fato, em uma análise populacional com seguimento superior a 5 anos, a mortalidade foi de 41,7% no grupo submetido à estratégia de controle do ritmo, e 46,3% no controle da frequência.88 Sendo assim, deve-se ter em mente que a escolha entre o controle do ritmo ou da frequência deve ser individualizada e, muitas vezes, é um processo dinâmico. Em um determinado momento, a estratégia de controle do ritmo pode ser atrativa, mas, em pacientes mais velhos com sintomas pouco expressivos, o controle da frequência pode constituir uma alternativa.

A reversão aguda ao ritmo sinusal é realizada por meio de cardioversão química ou elétrica, segundo os protocolos vigentes. Para a manutenção subsequente do ritmo sinusal, o uso de fármacos antiarrítmicos a longo prazo, a ablação por cateter ou a associação de estratégias são possibilidades que devem ser discutidas com o paciente. O uso de fármacos antiarrítmicos para manutenção do ritmo é comum no manejo clínico do paciente. A Tabela 2 demonstra os medicamentos utilizados para essa finalidade disponíveis no Brasil, com suas respectivas dosagens e efeitos colaterais. É importante mencionar que os efeitos colaterais dos fármacos antiarrítmicos usados a longo prazo são inúmeros, e foram expostos os mais comuns ou de maior gravidade. De fato, a escolha de tais medicamentos é estabelecida mais pelo seu perfil de segurança do que pela sua eficácia. O exemplo clássico é a amiodarona, que, apesar de apresentar superioridade frente a outros fármacos antiarrítmicos na manutenção do ritmo sinusal, tem seu uso restrito a pacientes com insuficiência cardíaca devido a seus efeitos tóxicos importantes com o uso prolongado.81 A propafenona e sotalol têm seu uso predominante no paciente sem doença cardíaca estrutural, lembrando que o sotalol pode prolongar o intervalo QT, e o monitoramento eletrocardiográfico é recomendado com o uso dessas medicações.

Tabela 2. – Fármacos antiarrítmicos utilizados para a manutenção do ritmo sinusal.

| Drogas utilizados para a manutenção do ritmo sinusal | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dose | Efeitos Colaterais | |

| Propafenona | 150 a 300mg / 3 vezes ao dia | Vertigem, palpitações disturbios da condução cardíaca, bradicardias, taquicardias, ansiedade, disturbios do sono, cefaéia |

| Sotalol | 80 a 160mg / 2 vezes ao dia | Bradicardia, dispneia, dor no peito, palpitação, sincope, tontura, diarréia, nausea, vômito, fadiga, erupção cutânea, torsade de pointes |

| Amiodarona | 100 a 200mg ao dia | neutropenia, agranulocitose, bradicardia, taquicardia. torsade de pointes , hipo e hipertireoidismo, neuropatia ótica, neurite, pancreatite, aumento de transaminases, transtorno hepático agudo, estado confusional, penumonite intersticial, brancoespasmo, eczema, urticária, hipotensão |

A ablação por cateter visando ao isolamento elétrico das veias pulmonares é o tratamento intervencionista largamente utilizado para a prevenção de recorrência de FA. De modo geral, a ablação por cateter é superior aos fármacos antiarrítmicos na manutenção do ritmo sinusal89 e, atualmente, apresenta sua indicação em pacientes sintomáticos com FA paroxística ou persistente refratária ou intolerante a pelo menos um medicamento antiarrítmico, ou como primeira linha de tratamento na FA paroxística, sintomática de acordo com as preferências do paciente. Outras indicações individualizadas também podem ocorrer. O estudo CABANA comparou a ablação por cateter com a terapia medicamentosa otimizada em pacientes com FA paroxística e persistente de acordo com o desfecho combinado de mortalidade total, AVC, sangramento maior e parada cardíaca. Após 5 anos de seguimento, não houve diferenças significativas entre as duas estratégias,90 mas as análises relacionadas à qualidade de vida demonstram uma melhora clínica significativa, e também na qualidade de vida dos pacientes submetidos à ablação.91

Cuidado integrado no cuidado do paciente com fibrilação atrial

Oferecer a complexidade de ações necessárias para o atendimento de excelência no paciente com FA é desafiador na prática clínica. Instituir mudanças na qualidade de vida, promover o controle rigoroso de fatores de risco, além da anticoagulação adequada e decisões relacionadas às diferentes estratégias terapêuticas quando centradas em um único profissional, podem ocasionar resultados insatisfatórios. Nesse sentido, a organização dos serviços de saúde com equipes multiprofissionais para o atendimento do paciente com FA é fundamental para assegurar o melhor atendimento. De fato, um estudo randomizado comparando o cuidado usual com o cuidado multidisciplinar demostrou uma redução no risco relativo de 35% no desfecho combinado de hospitalização e mortalidade.92 Outro ponto importante é que a ausência completa de eventos de FA, muitas vezes, é utópica, e o objetivo para o tratamento deve consistir em melhora da qualidade de vida, prevenção cardiovascular e mitigação das recorrências clínicas.

Agradecimentos

Agradecemos ao Dr. Andre d’Avila pelos constantes auxílios durante todo o processo de escrita, além da revisão final do material.

Vinculação acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Fontes de financiamento .O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114(2):119-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.. Krijthe BP, Kunst A, Benjamin EJ, Lip GY, Franco OH, Hofman A, et al. Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(35):2746-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1998;98(10):946–952. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.. Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med 1995;98(5):476–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.. Emdin CA, Wong CX, Hsiao AJ, Altman DG, Peters SA, Woodward M, et al. Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2016;532:h7013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.. Meyre P, Blum S, Berger S, Aeschbacher S, Schoepfer H, Briel M, et al. Risk of Hospital Admissions in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35(10):1332-1343. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.. Iwasaki Y, Nishida K, Kato T, Nattel S. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation. 2011;124(20):2264–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.. Schotten U, Verheule S, Kirchhof P, Goette A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: a translational appraisal. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):265–325. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.. Brugada R, Tapscott T, Czernuszewicz GZ, Marian AJ, Iglesias A, Mont L, et al. Identification of a genetic locus for familial atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(13):905–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.. Christophersen IE, Rienstra M, Roselli C, Yin X, Geelhoed B, Barnard J, et al. Large-scale analyses of common and rare variants identify 12 new loci associated with atrial fibrillation. Nat Genet. 2017;49(6):946–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.. Sharma PL. Mechanism of atrial flutter and fibrillation induced by aconitine in dogs, with observations on the role of cholinergic factors. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1963;21(2):368-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.. Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):659–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.. Atienza F, Jalife J. Reentry and atrial fibrillation. Hear Rhythm. 2007;4(3 Suppl):S13-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.. Chou CC, Chen PS. New concepts in atrial fibrillation: neural mechanisms and calcium dynamics. Cardiol Clin. 2009 Feb;27(1):35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.. Kneller J, Zou R, Vigmond EJ, Wang Z, Leon LJ, Nattel S. Cholinergic atrial fibrillation in a computer model of a two-dimensional sheet of canine atrial cells with realistic ionic properties. Circ Res. 2002;90(9):E73-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.. Burstein B, Nattel S. Atrial Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance in Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(8):802–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.. Yue L, Xie J, Nattel S. Molecular determinants of cardiac fibroblast electrical function and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2011 Mar 1;89(4):744–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.. Akoum N, Daccarett M, McGann C, Segerson N, Vergara G, Kuppahally S, et al. Atrial fibrosis helps select the appropriate patient and strategy in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a DE-MRI guided approach. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011 Jan;22(1):16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.. Chang TY, Chao TF, Liu CJ, Chen SJ, Chung FP, Liao JN, et al. The association between influenza infection, vaccination, and atrial fibrillation: A nationwide case-control study. Heart Rhythm. 2016 Jun;13(6):1189-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.. Issac TT, Dokainish H, Lakkis NM. Role of Inflammation in Initiation and Perpetuation of Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Nov;50(21):2021–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.. Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, et al. C-Reactive Protein Elevation in Patients With Atrial Arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001 Dec 11;104(24):2886–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.. Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994 Mar 16;271(11):840-4. [PubMed]

- 23.. Chung MK, Eckhardt LL, Chen LY, Ahmed HM, Gopinathannair R, Joglar JA, et al. Lifestyle and Risk Factor Modification for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Apr 21;141(16):e750-e772 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.. Wong CX, Sullivan T, Sun MT, Mahajan R, Pathak RK, Middeldorp M et al. Obesity and the risk of incident, post-operative, and post-ablation atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of 626,603 individuals in 51 studies. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1(3):139–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.. Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Miyasaka Y, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Verzosa GC, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for the progression of paroxysmal to permanent atrial fibrillation: a longitudinal cohort study of 21 years. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(18):2227–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.. Chatterjee NA, Giulianini F, Geelhoed B, Lunetta KL, Misialek JR, Niemeijer MN, et al. Genetic Obesity and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: Causal Estimates from Mendelian Randomization. Circulation. 2017;135(8):741-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, et al. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2222–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Wong CX, et al. Long-Term Effect Of Goal-Directed Weight Management in an Atrial Fibrillation Cohort: a long-term follow-up study (LEGACY). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(20):2159–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.. Rienstra M, Hobbelt AH, Alings M, Tijssen JGP, Smit MD, Brügemann J, et al; RACE 3 Investigators. Targeted therapy of underlying conditions improves sinus rhythm maintenance in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: results of the RACE 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(32):2987–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.. Middeldorp ME, Pathak RK, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Elliott AD, Mahajan R, et al. PREVEntion and regReSsive Effect of weight-loss and risk factor modification on Atrial Fibrillation: the REVERSE-AF study. Europace. 2018;20(12):1929–35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.. Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME, et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(19):2050–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.. Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, et al. Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on Arrhythmia Recurrence in Obese Individuals With Atrial Fibrillation: the CARDIO-FIT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(9):985–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.. Jamaly S, Carlsson L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjöström L, Karason K. Bariatric Surgery and the Risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Swedish Obese Subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(23):2497-2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.. Alonso A, Bahnson JL, Gaussoin SA, Bertoni AG, Johnson KC, Lewis CE et al ; Look AHEAD Research Group. Effect of an intensive lifestyle intervention on atrial fibrillation risk in individuals with type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2015;170(4):770–7.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.. Frost L, Benjamin EJ, Fenger-Grøn M, Pedersen A, Tjønneland A, Overvad K. Body fat, body fat distribution, lean body mass and atrial fibrillation and flutter: a Danish cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(6):1546– 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AGN. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 2005;365(9464):1046-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.. Peled N, Greenberg A, Pillar G, Zinder O, Levi N, Lavie P. Contributions of hypoxia and respiratory disturbance index to sympathetic activation and blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11(11 Pt 1):1284-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.. Fletcher EC. Cardiovascular consequences of obstructive sleep apnea: experimental hypoxia and sympathetic activity. Sleep. 2000;23(Suppl. 4):S127-31. [PubMed]

- 39.. Remsburg S, Launois SH, Weiss JW. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea have an abnormal peripheral vascular response to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87(3):1148-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.. Guilleminault C, Poyares D, Rosa A, Huang YS. Heart rate variability, sympathetic and vagal balance and EEG arousals in upper airway resistance and mild obstructive sleep apnea syndromes. Sleep Med. 2005;6(5):451-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.. Oliveira W, Campos O, Bezerra Lira-Filho E, Cintra FD, Vieira M, Ponchirolli A, et al. Left atrial volume and function in patients with obstructive sleep apnea assessed by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(12):1355-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.. Oliveira W, Campos O, Cintra F, Matos L, Vieira ML, Rollim B, et al. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on left atrial volume and function in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea assessed by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. Heart. 2009;95(22):1872-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.. Cintra F, Leite RP, Storti LJ, Bittencourt LA, Poyares D, Castro LD, et al. Sleep Apnea and Nocturnal Cardiac Arrhythmia: A Populational Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014;103(5):368-374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.. Braga B, Poyares D, Cintra F, Guilleminault C, Cirenza C, Horbach S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and chronic atrial fibrillation. Sleep Med. 2009;10(2):212-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.. Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA; Ammash NM; Gersh BJ; Ballman KV; et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;107(20):2589-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.. Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, Haffajee CI, Das S, Kumar K, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jul 23;62(4):300-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.. Ng CY, Liu T, Shehata M, Stevens S, Chugh SS, Wang X. Meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea as predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Am J Cardiol. 2011 Jul 1;108(1):47-51 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.. Kesaniemi YK, Danforth E Jr, Jensen MD, Kopelman PG, Lefèbvre P, Reeder BA. Dose-response issues concerning physical activity and health: an evidence-based symposium. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S351-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.. Mozaffarian D, Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Siscovick D. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2008;118(8):800–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.. Drca N, Wolk A, Jensen-Urstad M, Larsson SC. Physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of atrial fibrillation in middle-aged and elderly women. Heart. 2015;101(20):1627–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.. Everett BM, Conen D, Buring JE, Moorthy MV, Lee IM, Albert CM. Physical activity and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(3):321–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.. Azarbal F, Stefanick ML, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Manson JE, Albert CM, LaMonte MJ, et al. Obesity, physical activity, and their interaction in incident atrial fibrillation in postmenopausal women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(4):e001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.. Garnvik LE, Malmo V, Janszky I, Wisløff U, Loennechen JP, Nes BM. Physical activity modifies the risk of atrial fibrillation in obese individuals: the HUNT3 study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(15):1646–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.. Osbak PS, Mourier M, Kjaer A, Henriksen JH, Kofoed KF, Jensen GB. A randomized study of the effects of exercise training on patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2011;162(6):1080–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.. Kato M, Kubo A, Nihei F, Ogano M, Takagi H. Effects of exercise training on exercise capacity, cardiac function, BMI, and quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Int J Rehabil Res. 2017;40(3):193–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.. Abdulla J, Nielsen JR. Is the risk of atrial fibrillation higher in athletes than in the general population? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2009;11(9):1156–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.. Mohanty S, Mohanty P, Tamaki M, Natale V, Gianni C, Trivedi C, et al. Differential Association of Exercise Intensity with Risk of Atrial Fibrillation in Men and Women: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27(9):1021-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.. Mandyam MC, Vedantham V, Scheinman MM, Tseng ZH, Badhwar N, Lee BK, et al. Alcohol and vagal tone as triggers for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):364–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.. Johansson C, Lind MM, Eriksson M, Wennberg M, Andersson J, Johansson L. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: A population-based cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2020 Jun;76:50-57 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.. Voskoboinik A, Kalman JM, De Silva A, Nicholls T, Costello B, Nanayakkara S, et al. Alcohol Abstinence in Drinkers with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 2;382(1):20-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.. Zhu W, Yuan P, Shen Y, Wan R, Hong K. Association of smoking with the risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2016;218:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.. Cheng WH, Lo LW, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Hu YF, Hung Y, et al. Cigarette smoking causes a worse long-term outcome in persistent atrial fibrillation following catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2018;29(5):699–706. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.. van der Hooft CS, Heeringa J, Brusselle GG, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Kingma JH, et al. Corticosteroids and the risk of atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1016-20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.. Cheng M, Hu Z, Lu X, Huang J, Gu D. Caffeine intake and atrial fibrillation incidence: dose response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(4):448–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.. Feng T, Malmo V, Laugsand LE, Strand LB, Gustad LT, Ellekjær H, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression and risk of atrial fibrillation-The HUNT study. Int J Cardiol. 2020;306:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.. Chung MK, Eckhardt LL, Chen LY, Ahmed HM, Gopinathannair R, Joglar JA, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee and Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Lifestyle and Risk Factor Modification for Reduction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(16):e750-e772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.. Schneider MP, Hua TA, Böhm M, Wachtell K, Kjeldsen SE, Schmieder RE. Prevention of atrial fibrillation by Renin-Angiotensin system inhibition a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(21):2299-307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.. Soliman EZ, Rahman AF, Zhang ZM, Rodriguez CJ, Chang TI, Bates JT, et al. Effect of Intensive Blood Pressure Lowering on the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1491-1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.. Marott SC, Nielsen SF, Benn M, Nordestgaard BG. Antihypertensive treatment and risk of atrial fibrillation: a nationwide study. Eur Heart J 2014;35(18):1205–1214. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.. Wachtell K, Lehto M, Gerdts E, Olsen MH, Hornestam B, Dahlöf B, Ibsen H, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Devereux RB. Angiotensin II receptor blockade reduces new-onset atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke compared to atenolol: the Losartan Intervention For End Point Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(5):712-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.. GISSI-AF Investigators, Disertori M, Latini R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Staszewsky L, Maggioni AP, et al. Valsartan for prevention of recurrent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;360(16):1606–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.. Goette A, Schon N, Kirchhof P, Breithardt G, Fetsch T, Hausler KG, et al. Angiotensin II antagonist in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (ANTIPAF) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5(1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.. Huxley RR, Filion KB, Konety S, Alonso A. Meta-analysis of cohort and case- control studies of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2011;108(1):56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Goudis CA, Korantzopoulos P, Ntalas IV, Kallergis EM, Liu T, Ketikoglou DG. Diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation: pathophysiological mechanisms and potential upstream therapies. Int J Cardiol 2015;184(2015):617–622. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.. Chao TF, Leu HB, Huang CC, Chen JW, Chan WL, Lin SJ, et al. Thiazolidinediones can prevent new onset atrial fibrillation in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes. Int J Cardiol. 2012;156(2):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.. Creta A, Providência R, Adragão P, de Asmundis C, Chun J, Chierchia G, et al. Impact of Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus on the Outcomes of Catheter Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation (European Observational Multicentre Study). Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(6):901-906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.. Gu J, Liu X, Wang X, Shi H, Tan H, Zhou L, et al. Beneficial effect of pioglitazone on the outcome of catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Europace. 2011;13(9):1256–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.. Alonso A, Yin X, Roetker NS, Magnani JW, Kronmal RA, Ellinor PT, et al. Blood lipids and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014; 3(5):e001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.. Lopez FL, Agarwal SK, Maclehose RF, Soliman EZ, Sharrett AR, Huxley RR, et al. Blood lipid levels, lipid-lowering medications, and the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5(1):155– 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, et al. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2222-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.. Magalhães LP, Figueiredo MJO, Cintra FD, Saad EB, Kuniyishi RR, Teixeira RA, et al. II Diretrizes Brasileiras de Fibrilação Atrial. Arq Bras Cardiol 2016; 106(4Supl.2):1-22.

- 82.. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, Tuininga YS, Tijssen JG, Alings AM, et al, RACE II Investigators. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2010;362(15):1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.. Smit MD, Crijns HJ, Tijssen JG, Hillege HL, Alings M, Tuininga YS, et al; RACE II Investigators. Effect of lenient versus strict rate control on cardiac remodeling in patients with atrial fibrillation data of the RACE II (RAte Control Efficacy in permanent atrial fibrillation II) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(9):942-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893-2962. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Rosenberg Y, Schron EB et al; Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(23):1825- 1833. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.. Van Gelder IC, Hagens VE, Bosker HA, Kingma JH, Kamp O, Kingma T et al; Rate Control versus Electrical Cardioversion for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation Study Group. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(23):1834-1840. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.. Corley SD, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Domanski MJ, Geller N, Greene HL, et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1509-1513 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.. Ionescu-Ittu R, Abrahamowicz M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Wynant W, et al. Comparative effectiveness of rhythm control vs rate control drug treatment effect on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(13):997-1004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.. Mont L, Bisbal F, Hernandez-Madrid A, Perez-Castellano N, Vinolas X, Arenal A, et al, SARA investigators. Catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation: a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (SARA study). Eur Heart J 2014;35(8): 501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.. Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, Monahan KH, Bahnson TD, Poole JE, et al; CABANA Investigators. Effect of Catheter Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy on Mortality, Stroke, Bleeding, and Cardiac Arrest Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The CABANA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1261-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.. Mark DB, Anstrom KJ, Sheng S, Piccini JP, Baloch KN, Monahan KH, et al; CABANA Investigators. Effect of Catheter Ablation vs Medical Therapy on Quality of Life Among Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: The CABANA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1275-1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.. Hendriks JM, de Wit R, Crijns HJ, Vrijhoef HJ, Prins MH, Pisters R, et al. Nurse-led care vs. usual care for patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized trial of integrated chronic care vs. routine clinical care in ambulatory patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(21):2692–9. [DOI] [PubMed]