Abstract

Objective:

The network theory of psychopathology examines networks of interconnections across symptoms. Several network studies of disordered eating have identified central and bridge symptoms in Western samples, yet network models of disordered eating have not been tested in non-Western samples. The current study tested a network model of disordered eating in Iranian adolescents and college students, as well as models of co-occurring depression and self-esteem.

Method:

Participants were Iranian college students (n = 637) and adolescents (n = 1,111) who completed the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) and Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-II). We computed six Glasso networks and identified central and bridge symptoms.

Results:

Central disordered eating nodes in most models were a desire to lose weight and discomfort when seeing one’s own body. Central self-esteem and depression nodes were feeling useless and self-dislike, respectively. Feeling like a failure was the most common bridge symptom between disordered eating and depression symptoms. With exception of a few differences in some edges, networks did not significantly differ in structure.

Discussion:

Desire to lose weight was the most central node in the networks, which is consistent with sociocultural theories of disordered eating development, as well as prior network models from Western-culture samples. Feeling like a failure was the most central bridge symptom between depression and disordered eating, suggesting that very low self-esteem may be a shared correlate or risk factor for disordered eating and depression in Iranian adolescents and young adults.

Keywords: Disordered eating, Self-esteem, Depression, Network analysis

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) affect adolescents and adults, and across the lifespan are best conceptualized as dimensional in nature (Luo et al., 2016). An approach to classifying EDs that incorporates dimensions of comorbid psychopathology might help to elucidate within-group differences in the mechanisms that underlie the expression of disordered eating (Wildes & Marcus, 2013). Low self-esteem and depression symptoms often co-occur with disordered eating (Santos, Richards, & Bleckley, 2007) and have been shown to contribute to disordered eating symptoms (Brechan & Kvalem, 2015; Fairburn, Cooper, & Shafran, 2003; Pauli-Pott et al., 2013; Puccio et al., 2017).

Most research on the links between disordered eating symptoms and comorbidities (e.g., depression) has been conceptualized from the perspective that psychopathology symptoms result from a common latent variable (Borsboom, Mellenbergh, & van Heerden, 2003). For instance, these traditional approaches postulate that an underlying latent disease (i.e., depression) produces a variety of psychological symptoms (e.g., low energy, low mood) without symptoms relating to one another. On the other hand, network theory (Fried & Cramer, 2017) is a framework that suggests that symptom-level interrelations are what cause and constitute psychopathology (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; McNally, 2016). In a network, symptoms are represented as nodes, connected by edges that depict the strength and direction of associations. ‘Central’ symptoms are those that demonstrate the strongest connections to other nodes, and central symptoms are thought to maintain the network (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Freeman, 1978; McNally, 2016). With respect to comorbidities, network theory refers to symptoms from one diagnostic cluster that are connected to symptoms in another cluster as ‘bridge’ symptoms.

Network theory has recently been used to conceptualize EDs. Most studies find that overvaluation of weight or shape or desire to lose weight are the most central symptoms (Brown et al., 2020; Calugi et al., 2020; Christian et al., 2020; DuBois et al., 2017; Elliott, Jones, & Schmidt, 2020a; Forrest, Jones, Ortiz, & Smith, 2018; Goldschmidt et al., 2018; Levinson et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Network models have also been used to explore the interrelations among EDs and common comorbidities (Forrest, Sarfan, Ortiz, Brown, & Smith, 2019; Levinson et al., 2018; Levinson et al., 2017; Monteleone et al., 2019). Levinson and colleagues (2017) found that physical sensations (i.e., feelings of wobbliness, lack of interest in sex, changes in appetite) were the bridge symptoms between bulimia nervosa and anxiety and depression symptoms. Given that misperception of physiological sensations (i.e., altered interoceptive processing) is implicated in EDs (Jenkinson et al., 2018), depression (Paulus & Stein, 2010), and anxiety (Paulus & Stein, 2010), perhaps interoceptive dysfunction may be an important bridge between EDs and depression and anxiety. However, little is known about how self-esteem may bridge disordered eating and depression, and most research has been conducted in Western societies among clinical samples.

Although once thought to be an exclusively Western phenomenon, disordered eating and EDs are observed among Iranian adolescents and college-aged individuals (Jalali-Farahani et al., 2015; Rauof et al., 2015; Sahlan, Taravatrooy, Quick, & Mond, 2020). Two studies have found that disordered eating symptoms are higher in adolescent females than males (Jalali-Farahani et al., 2015; Rauof et al., 2015). However, among college students, binge eating frequency is comparable across sex, though sex differences are observed for some individual symptoms (e.g., purging is higher in males vs. females; Sahlan et al., 2020). These data indicate that disordered eating symptoms do occur outside of non-Western societies. Importantly, ED and depression comorbidity occurs at a rate of 16.46% in Iranian children and adolescents (Mohammadi et al., 2020); however, unknown is how individual depression and disordered eating symptoms relate to one another among Iranian people. This question is examined for the first time in the current study.

The current study used network analysis to identify central disordered eating symptoms among a large, non-clinical sample of Iranian adolescents and young adults. We also examined bridge symptoms among disordered eating, depression, and self-esteem, and compared networks between adolescents vs. adults and males vs. females. In line with previous studies (e.g., Brown et al., 2020; Calugi et al., 2020), we hypothesized that desire to lose weight would be the most central symptom. Given previous findings (Levinson et al., 2017), we hypothesized that physical sensations would bridge disordered eating and depression symptoms. Finally, as the existing literature on gender and age-related differences in symptom networks is sparse, we examined sex and age-related network models from an exploratory lens.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 1,749) came from two samples. Data from Sample 1 (n = 637, 60.3% female) were also used in Sahlan et al. (2020). However, the aims and analyses of the current project are unique and have not been published previously. Additionally, the adolescent sample was not published previously. Potential participants from multiple cities in Iran were approached during class and given information about the study. Participants provided written informed consent, and those who agreed to participate completed questionnaires (provided in Farsi) in the presence of research staff without remuneration. Sample 2 included adolescents (n =1,112, 54.6% female) who were recruited from approximately 4,100 adolescents and 19 schools (9 schools for boys and 10 schools for girls) comprised of 154 classes (Tehran: n = 7 schools, n = 56 classes; Tabriz: n = 4 schools, n = 36 classes; Kurdistan: n = 4 schools, n = 30 classes; Rasht: n = 4 schools, n = 32 classes). Participation rate was 27.1% in adolescents. All potential participants were approached on campus or during class and were invited to participate in a study that would test psychological issues among college students or adolescents. One adolescent did not include demographic information and was excluded from the analyses. For adolescent participants, school and regional administrators approved the research procedures and parental consent was obtained prior to their child’s participation. Also, adolescents provided assent. Study 1 and 2 were approved by the institutional review board of Iran University of Medical Sciences. Age ranged from 12–19 in the adolescent sample and 18–54 in college students. Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for disordered eating symptoms, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem

| Full sample n = 1,748 |

College n = 637 |

Adolescents n = 1,111 |

Males n = 757 |

Females n = 991 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| EDE-Q clinical thresholda | 325 (18.60) | 215 (19.40) | 110 (17.30) | 103 (13.60) | 222 (22.40) | |

| Recurrent eating disorder behaviorb | ||||||

| Binging | 390 (22.80) | 168 (26.70) | 222 (20.30) | 156 (20.70) | 234 (23.40) | |

| Self-induced vomiting | 58 (3.40) | 11 (1.80) | 47 (4.40) | 35 (4.50) | 23 (2.30) | |

| Laxative misuse | 88 (5.20) | 13 (2.30) | 75 (6.90) | 41 (5.40) | 47 (4.70) | |

| Over-exercise | 326 (18.70) | 74 (11.80) | 252 (23.0) | 151 (21.10) | 175 (17. 50) | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Min-max | |

| Age | 17.86 (3.96) | 21.89 (3.62) | 15.55 (1.59) | 17.53 (3.76) | 18.11 (4.09) | 12–54 |

| BMI | 21.53 (3.61) | 22.21 (3.49) | 21.15 (3.62) | 21.78 (3.79) | 21.35 (3.46) | 11.10–39.18 |

| Eating Disorder Examination–Questionnaire | ||||||

| Restraint | 1.64 (2.16) | 1.42 (2.06) | 1.78 (2.21) | 1.43 (2.07) | 1.81 (2.22) | 0–6 |

| Fasting | 0.87 (1.55) | 0.82 (1.53) | 0.89 (1.56) | 0.75 (1.48) | 0.95 (1.60) | 0–6 |

| Excluding food | 1.02 (1.75) | 0.93 (1.67) | 1.07 (1.79) | 0.90 (1.70) | 1.11 (1.78) | 0–6 |

| Food rules | 1.30 (1.87) | 1.31 (1.85) | 1.30 (1.88) | 1.27 (1.92) | 1.33 (1.83) | 0–6 |

| A desire to have an empty stomach | 0.96 (1.73) | 0.79 (1.57) | 1.07 (1.80) | 0.73 (1.50) | 1.14 (1.86) | 0–6 |

| A desire to have a flat stomach | 3.35 (2.56) | 3.23 (2.53) | 3.42 (2.57) | 3.19 (2.58) | 3.47 (2.54) | 0–6 |

| Difficulty concentrating because of thoughts of food | 0.98 (1.66) | 0.89 (1.52) | 1.03 (1.74) | 0.87 (1.56) | 1.06 (1.73) | 0–6 |

| Difficulty concentrating because of thoughts of weight/shape | 1.15 (1.81) | 1.02 (1.66) | 1.22 (1.89) | 1.06 (1.71) | 1.22 (1.88) | 0–6 |

| Fear of losing control over eating | 1.26 (1.97) | 1.15 (1.85) | 1.32 (2.03) | 0.88 (1.69) | 1.54 (2.12) | 0–6 |

| Fear of weight gain | 1.93 (2.34) | 1.75 (2.23) | 2.04 (2.40) | 1.44 (2.11) | 2.30 (2.44) | 0–6 |

| Feeling fat | 1.78 (2.28) | 1.70 (2.20) | 1.83 (2.33) | 1.39 (2.07) | 2.08 (2.39) | 0–6 |

| Desire to lose weight | 2.24 (2.63) | 1.91 (2.40) | 2.42 (2.73) | 1.88 (2.46) | 2.50 (2.72) | 0–6 |

| Eating in secret | 0.50 (1.15) | 0.34 (0.85) | 0.58 (1.28) | 0.57 (1.24) | 0.44 (1.07) | 0–6 |

| Feeling guilty after eating | 0.97 (1.56) | 0.93 (1.53) | 0.99 (1.58) | 0.77 (1.38) | 1.12 (1.67) | 0–6 |

| Concerns about others seeing one eat | 0.69 (1.37) | 0.54 (1.20) | 0.78 (1.45) | 0.72 (1.40) | 0.67 (1.34) | 0–6 |

| Overvaluation of weight | 1.83 (2.01) | 1.84 (1.97) | 1.83 (2.03) | 1.74 (2.03) | 1.91 (1.99) | 0–6 |

| Overvaluation of shape | 2.14 (2.12) | 2.28 (2.07) | 2.05 (2.14) | 2.10 (2.14) | 2.17 (2.10) | 0–6 |

| Upset with weighing oneself more than once a week | 1.27 (1.79) | 1.12 (1.62) | 1.36 (1.87) | 1.13 (1.72) | 1.38 (1.83) | 0–6 |

| Weight dissatisfaction | 2.08 (2.09) | 2.16 (2.02) | 2.02 (2.13) | 1.78 (1.96) | 2.30 (2.16) | 0–6 |

| Shape dissatisfaction | 2.09 (2.06) | 2.20 (1.95) | 2.02 (2.12) | 1.90 (1.98) | 2.23 (2.11) | 0–6 |

| Discomfort when seeing one’s own body | 1.67 (1.95) | 1.75 (1.84) | 1.62 (2.00) | 1.38 (1.78) | 1.90 (2.03) | 0–6 |

| Discomfort when others see one’s body | 1.50 (1.93) | 1.38 (1.75) | 1.57 (2.03) | 1.25 (1.73) | 1.69 (2.05) | 0–6 |

| Binging | 2.78 (5.22) | 2.88 (4.79) | 2.72 (5.45) | 2.66 (5.08) | 2.86 (5.32) | 0–50 |

| Self-induced vomiting | 0.37 (1.82) | 0.16 (0.79) | 0.50 (2.19) | 0.49 (1.91) | 0.29 (1.74) | 0–28 |

| Laxative misuse | 0.63 (2.66) | 0.34 (1.95) | 0.80 (2.98) | 0.65 (2.53) | 0.61 (2.75) | 0–28 |

| Over-exercise | 2.40 (5.51) | 1.45 (4.33) | 2.94 (6.02) | 2.56 (5.66) | 2.27 (5.40) | 0–30 |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | ||||||

| Feeling worthy | 1.66 (0.76) | 1.54 (0.62) | 1.73 (0.82) | 1.65 (0.78) | 1.67 (0.74) | 1–4 |

| Having good qualities | 1.55 (0.66) | 1.46 (0.55) | 1.60 (0.72) | 1.56 (0.69) | 1.54 (0.64) | 1–4 |

| Being capable | 1.72 (0.73) | 1.64 (0.67) | 1.77 (0.76) | 1.71 (0.75) | 1.72 (0.71) | 1–4 |

| Having a positive self-attitude | 1.72 (0.78) | 1.67 (0.73) | 1.75 (0.80) | 1.67 (0.75) | 1.77 (0.79) | 1–4 |

| Satisfaction with one’s self | 1.91 (0.84) | 1.91 (0.81) | 1.90 (0.86) | 1.87 (0.84) | 1.94 (0.85) | 1–4 |

| Not having much to be proud ofc | 1.93 (0.86) | 2.01 (0.81) | 1.88 (0.89) | 1.91 (0.87) | 1.94 (0.86) | 1–4 |

| Feeling like a failurec | 1.89 (0.85) | 1.95 (0.82) | 1.85 (0.87) | 1.85 (0.85) | 1.91 (0.85) | 1–4 |

| Wishing for more respect for one’s selfc | 2.25 (0.99) | 2.28 (0.96) | 2.23 (1.01) | 2.17 (1.00) | 2.30 (0.99) | 1–4 |

| Feeling uselessc | 1.88 (0.92) | 1.98 (0.88) | 1.82 (0.93) | 1.81 (0.92) | 1.93 (0.91) | 1–4 |

| Thinking one is no goodc | 1.88 (0.91) | 2.02 (0.89) | 1.80 (0.92) | 1.80 (0.90) | 1.94 (0.92) | 1–4 |

| Beck Depression Inventory–II | ||||||

| Sadness | 0.64 (0.80) | 0.64 (0.72) | 0.65 (0.84) | 0.51 (0.74) | 0.75 (0.83) | 0–3 |

| Pessimism | 0.70 (1.00) | 0.69 (0.96) | 0.71 (1.02) | 0.62 (0.93) | 0.76 (1.04) | 0–3 |

| Past failure | 0.62 (0.92) | 0.65 (0.91) | 0.60 (0.93) | 0.54 (0.88) | 0.68 (0.95) | 0–3 |

| Loss of pleasure | 0.69 (0.92) | 0.65 (0.87) | 0.71 (0.95) | 0.59 (0.85) | 0.76 (0.97) | 0–3 |

| Feeling guilty | 0.62 (0.84) | 0.56 (0.80) | 0.65 (0.86) | 0.55 (0.82) | 0.67 (0.85) | 0–3 |

| Feeling like one is being punished | 0.65 (0.96) | 0.62 (0.92) | 0.67 (0.98) | 0.60 (0.89) | 0.69 (1.00) | 0–3 |

| Self-dislike | 0.52 (0.88) | 0.47 (0.80) | 0.54 (0.92) | 0.44 (0.81) | 0.57 (0.92) | 0–3 |

| Self-criticism | 0.80 (0.94) | 0.85 (0.89) | 0.77 (0.96) | 0.70 (0.86) | 0.88 (0.98) | 0–3 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.47 (0.84) | 0.34 (0.71) | 0.55 (0.90) | 0.42 (0.78) | 0.52 (0.88) | 0–3 |

| Crying | 0.75 (1.03) | 0.70 (1.02) | 0.77 (1.03) | 0.51 (0.93) | 0.92 (1.06) | 0–3 |

| Agitation | 0.60 (0.91) | 0.50 (0.82) | 0.66 (0.96) | 0.55 (0.90) | 0.63 (0.92) | 0–3 |

| Loss of interest | 0.78 (1.00) | 0.68 (0.90) | 0.83 (1.05) | 0.69 (0.97) | 0.84 (1.02) | 0–3 |

| Indecision | 0.61 (0.92) | 0.65 (0.91) | 0.59 (0.93) | 0.50 (0.84) | 0.70 (0.97) | 0–3 |

| Feeling worthless | 0.46 (0.85) | 0.43 (0.80) | 0.48 (0.87) | 0.43 (0.83) | 0.48 (0.86) | 0–3 |

| Loss of energy | 0.60 (0.86) | 0.59 (0.83) | 0.61 (0.88) | 0.51 (0.82) | 0.67 (0.88) | 0–3 |

| Sleep disturbance | 0.85 (0.89) | 0.77 (0.81) | 0.89 (0.93) | 0.79 (0.88) | 0.89 (0.90) | 0–3 |

| Irritability | 0.50 (0.81) | 0.41 (0.70) | 0.55 (0.87) | 0.54 (0.85) | 0.47 (0.79) | 0–3 |

| Changes in appetite | 0.89 (0.97) | 0.89 (0.94) | 0.89 (0.98) | 0.76 (0.90) | 0.99 (1.01) | 0–3 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 0.66 (0.86) | 0.66 (0.83) | 0.66 (0.88) | 0.57 (0.83) | 0.73 (0.88) | 0–3 |

| Tiredness | 0.73 (0.93) | 0.67 (0.84) | 0.77 (0.97) | 0.62 (0.88) | 0.82 (0.95) | 0–3 |

| Loss of interest in sex | 0.54 (0.86) | 0.45 (0.77) | 0.60 (0.91) | 0.52 (0.82) | 0.56 (0.90) | 0–3 |

Note: EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire.

The clinical threshold of the EDE-Q is a global score ≥ 2.5.

Recurrent eating disorder behavior was defined as engaging in binging, self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, and over exercise ≥ 4 times during the past 28 days.

Items were reverse coded such that higher scores indicated lower self-esteem to facilitate ease of interpretation of the network model.

Measures

Items from all measures were included as individual nodes in the networks. All measures are appropriate for use in both adolescents and adults (Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire [EDE-Q]: Carrard et al., 2015; Mond et al., 2014, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [RSES]: Bagley & Mallick, 2001; Sinclair et al., 2010, Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]: Dardas, Silva, Noonan, & Simmons, 2018; Segal, Coolidge, Cahill, & O’Riley, 2008).

Disordered eating.

The Persian translation of the EDE-Q (Sahlan et al., 2020) assessed disordered eating symptoms over the past 28 days. Twenty-two items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (No days) to 6 (Every day). Five items assess the frequency of disordered eating behaviors. Internal consistency was excellent (αs=.90–.92). Between 13.6–22.4% of participants reported clinical levels of disordered eating (i.e., ≥2.5; EDE-Q global score, Rø, Reas, & Stedal, 2015). Additionally, between 1.8–26.7% of participants reported recurrent binging, or purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, and over-exercise) in past 28 days.

Self-esteem.

The Persian translation of the RSES (Shapurian, Hojat, & Nayerahmadi, 1987) assessed global self-esteem. The scale includes ten items rated on a four-point Likert ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). Some items were reverse-scored so that higher scores reflect lower self-esteem. Internal consistency was strong (αs=.84–.87).

Depressive symptoms.

The Persian translation of the BDI-II (Ghassemzadeh, Mojtabai, Karamghadiri, & Ebrahimkhani, 2005) assessed depressive symptoms. The scale includes 21 items which rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (Did not apply to me at all) to 3 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time). Internal consistency was excellent (αs=.92).

Data Analytic Procedure

Analyses were conducted using R software. Six Glasso networks were estimated using the estimateNetwork function in the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2020). Model 1 included the full sample (N=1,748) with only the EDE-Q items. Models 2–6 included items from all three measures. Model 2 included the full sample. Model 3 included the college sample. Model 4 included the adolescent sample. Model 5 included males from both samples. Model 6 included females from both samples. The goldbricker function in the networktools package (Jones, 2019) was used to determine whether any items may measure the same construct by identifying items with highly similar correlations to other items. Goldbricker indicated that binge eating and losing control when eating appeared to be measuring the same construct, and due to eating a large amount of food also conceptually overlapping with binge eating, we chose to remove the two items and include only binge eating in the models. All other items were included in Models 2–6. Table 2 includes the symptoms and corresponding labels.

Table 2.

Network node labels with their corresponding symptom and item wording

| Node label | Symptom | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Disordered Eating Symptoms (EDE-Q) | ||

| restraint | Restraint | Have you been deliberately trying to limit the amount of food you eat to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)? |

| fast | Fasting | Have you gone for long periods of time (8 waking hours or more) without eating anything at all in order to influence your shape or weight? |

| exclfood | Excluding food | Have you tried to exclude from your diet any foods that you like in order to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)? |

| rules | Food rules | Have you tried to follow definite rules regarding your eating (for example, a calorie limit) in order to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)? |

| empty | Desire to have an empty stomach | Have you had a definite desire to have an empty stomach with the aim of influencing your shape or weight? |

| flat | Desire to have a flat stomach | Have you had a definite desire to have a totally flat stomach? |

| foodconc | Difficulty concentrating because of thoughts of food | Has thinking about food, eating, or calories made it very difficult to concentrate on things you are interested in (for example, working, following a conversation, or reading)? |

| wsconc | Difficulty concentrating because of thoughts of weight/shape | Has thinking about shape or weight made it very difficult to concentrate on things you are interested in (for example, working, following a conversation, or reading)? |

| losecnt | Fear of losing control over eating | Have you had a definite fear of losing control over eating? |

| gainw | Fear of weight gain | Have you had a definite fear that you might gain weight? |

| feelfat | Feeling fat | Have you felt fat? |

| dsrlosew | Desire to lose weight | Have you had a strong desire to lose weight? |

| secret | Eating in secret | Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you eaten in secret (i.e., furtively)? |

| eatguilty | Feeling guilty after eating | On what proportion of the times that you have eaten have you felt guilty (felt that you’ve done wrong) because of its effect on your shape or weight? |

| eatothers | Concerns about others seeing one eat | Over the past 28 days, how concerned have you been about other people seeing you eat? |

| wjudge | Overvaluation of weight | Has your weight influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person? |

| sjudge | Overvaluation of shape | Has your shape influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person? |

| weigh | Upset with weighing oneself more than once a week | How much would it have upset you if you had been asked to weigh yourself once a week (no more, or less, often) for the next four weeks? |

| wdissat | Weight dissatisfaction | How dissatisfied have you been with your weight? |

| sdissat | Shape dissatisfaction | How dissatisfied have you been with your shape? |

| seebody | Discomfort when seeing one’s own body | How uncomfortable have you felt seeing your body (for example, seeing your shape in the mirror, in a shop window reflection, while undressing or taking a bath or shower)? |

| othersee | Discomfort when others see one’s body | How uncomfortable have you felt about others seeing your shape or figure (for example, in communal changing rooms, when swimming, or wearing tight clothes? |

| binge | Binging | Had a sense of losing control over your eating and ate an unusually large amount of food. |

| vomit | Self-induced vomiting | Made yourself sick (vomit) for shape or weight concerns. |

| lax | Laxative misuse | Taken laxatives for shape or weight concerns. |

| exc | Over-exercise | Exercised in a “driven” or “compulsive” way for shape or weight concerns. |

| Self-Esteem (RSES) | ||

| worth | Feeling worthy | I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others. |

| goodqual | Having good qualities | I feel that I have a number of good qualities. |

| dothings | Being capable | I am able to do things as well as most other people. |

| posattit | Having a positive self-attitude | I take a positive attitude toward myself. |

| satisf | Satisfaction with one’s self | On the whole, I am satisfied with myself. |

| notproud | Not having much to be proud of | I feel I do not have much to be proud of. |

| failure | Feeling like a failure | All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure. |

| moreresp | Low self-respect | I wish I could have more respect for myself. |

| useless | Feeling useless | I certainly feel useless at times. |

| nogood | Thinking one is no good | At times I think I am no good at all. |

| Depression Symptoms (BDI-II) | ||

| sad | Sadness | I am so sad and unhappy that I can’t stand it. |

| pess | Pessimism | I feel the future is hopeless and will only get worse. |

| pastfail | Past failure | I feel I am a total failure as a person. |

| losspleas | Loss of pleasure | I can’t get any pleasure from the things I used to enjoy. |

| guilty | Feeling guilty | I feel guilty all of the time. |

| punish | Feeling like one is being punished | I feel I am being punished. |

| selfdislike | Self-dislike | I dislike myself. |

| selfcritic | Self-criticism | I blame myself for everything bad that happens. |

| suicidal | Suicidal ideation | I would kill myself if I had the chance. |

| cry | Crying | I feel like crying, but I can’t. |

| agitate | Agitation | I am so restless or agitated that I have to keep moving or doing something. |

| lossint | Loss of interest | It’s hard to get interested in anything. |

| indecis | Indecision | I have trouble making any decisions. |

| worthless | Feeling worthless | I feel utterly worthless. |

| lossener | Loss of energy | I don’t have enough energy to do anything. |

| sleep | Sleep disturbance | I sleep most of the day or I wake up 1–2 hours early and can’t get back to sleep. |

| irritable | Irritability | I am irritable all the time. |

| appetite | Changes in appetite | I have no appetite at all or I crave food all the time. |

| conc | Difficulty concentrating | I find I can’t concentrate on anything. |

| tired | Tiredness | I am too tired or fatigued to too most of the things I used to. |

| sex | Loss of interest in sex | I have lost interest in sex completely. |

The Glasso function estimates partial correlations between nodes. Networks were estimated using Spearman correlations rather than polychoric correlations, as Spearman correlations produce more stable networks (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). The Glasso function utilizes the ‘least absolute shrinkage and selection operator’ (LASSO; Tibshirani, 1996), which causes many of the edge estimates (i.e., correlations) to be reduced to zero, therefore dropping them out of the model. Thus, LASSO estimates a ‘conservative’ network model where only a small number of edges are included in the network structure (Epskamp, Borsboom, & Fried, 2018). Edge weight confidence intervals, which represent the confidence intervals for each individual edge, can be found in Supplementary materials. Stability estimates of each network were calculated with the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2020), which utilizes bootstrapping techniques. Stability values above .50 indicate network stability (Epskamp, Borsboom, & Fried, 2018), such that a stability coefficient of .50 indicates that 50% of the cases could be removed from the analysis while still obtaining a similar network structure.

Strength centrality (i.e., the sum of the absolute values of edges) was calculated using the centralityplot function in the qgraph package (Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittman, & Bosboom, 2012). We used strength centrality as it is the most stable and has been suggested to be the most appropriate measure of centrality in psychological networks compared to other measures of centrality (i.e., betweenness, closeness; Bringmann et al., 2019).

Centrality difference tests were conducted using the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2020) to determine if specific symptoms were significantly more central than others. Based on the results of each of the centrality difference tests, two to five of the most central symptoms of each network was included in our interpretation of the results. We did not use a standard cut-off value for each network due to variability among networks. Centrality difference tests can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Bridge symptoms were identified using the bridge function of the networktools package (Jones, 2019). This function allows for groups of symptoms to be analyzed (e.g., psychiatric diagnoses). Each group in this analysis represented disordered eating symptoms, depression, or self-esteem. The bridge function of the networktools package (Jones, 2019) quantifies the partial correlations between nodes in different symptom clusters with a metric called bridge expected influence (i.e., the sum of the value of all the edges that exist between a node and all nodes in other groups [Jones, 2019]). Stability estimates of bridge expected influence (BEI) were estimated using the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). We used BEI estimates to identify the strongest bridge symptoms. BEI difference tests were conducted using the bootnet package (Epskamp & Fried, 2018).

When analyzing symptoms from multiple constructs, symptoms commonly cluster by construct or measure due to high correlations between items (Cramer et al., 2010; Borsboom, 2017; Fried & Cramer, 2017). In this study, we expected symptoms to cluster by construct, such that disordered eating, depression, and self-esteem items would be highly connected. Similar construct clusters have been found in other comorbidity network studies (Afzali et al., 2017; Choi, Batchelder, Ehlinger, Safren, & O’Cleirigh, 2017; Robinaugh, LeBlanc, Vuletich, & McNally, 2014; Ruzzano, Borsboom, & Geurts, 2015).

We compared both the college vs. adolescent samples and males vs. females using the NetworkComparisonTest package (van Borkulo et al., 2016). Three estimates were obtained to analyze differences between networks: network invariance (i.e., whether the structure of the network is different by measuring the differences in maximum edge strength), global strength invariance (i.e., whether the overall connectivity differs across networks by measuring the differences in the sum of the edge strength), and edge invariance (i.e., whether a specific edge between nodes differs between networks by measuring the differences between specific edges; van Borkulo et al., 2016).

Results

Missing Data

Missing data ranged from 0–0.8% in the adolescent sample and 0–0.2% in the college sample. Missing data were handled with pairwise deletion.

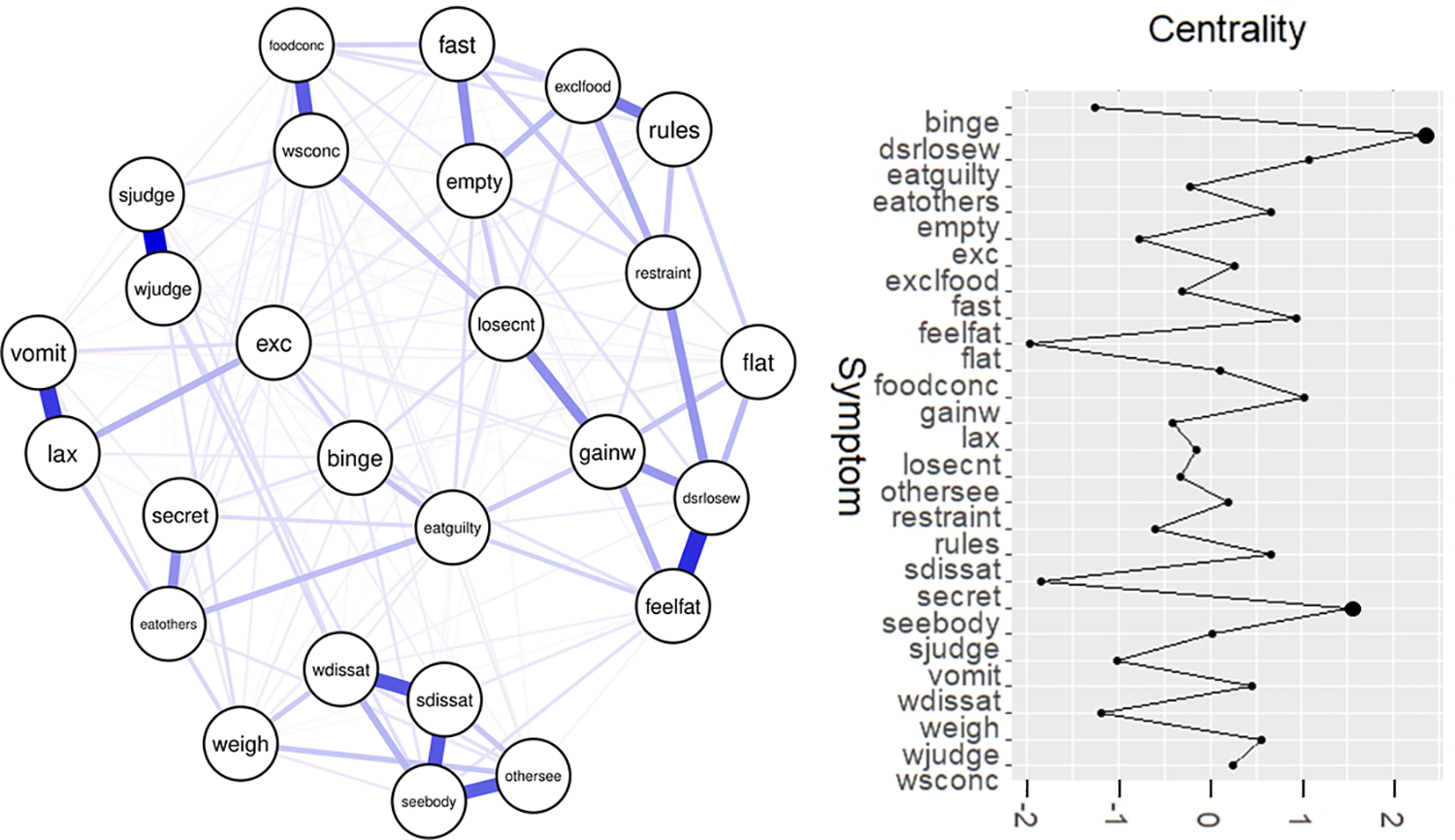

Model 1

Model 1 was stable (strength=.75, edge=.75). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: desire to lose weight (strength [S]=2.32) and discomfort when seeing one’s own body (S=1.51; Figure 1 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥84.00% of other symptoms (ps<.05).

Figure 1. Model 1 network and centrality plot.

Notes: See Table 2 for a list of all node names and their corresponding symptoms/measure items. Larger dots on the centrality graph (right) denote the most central symptoms.

Table 3.

Networks and their most central symptoms, in order of the most consistent central symptoms.

| Model 2 (full sample) | Central Symptoms | Bridge Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Desire to lose weight | Feeling like a failure | |

| Feeling useless | ||

| Discomfort when seeing one’s own body | ||

| Self-dislike | ||

| Model 3 (college students) | Central Symptoms | Bridge Symptoms |

| Desire to lose weight Feeling worthless |

Not having much to be proud of | |

| Feeling like a failure | ||

| Feeling useless | ||

| Model 4 (adolescents) | Central Symptoms | Bridge Symptoms |

| Desire to lose weight Feeling useless Discomfort when seeing one’s own body |

Feeling like a failure | |

| Self-dislike | ||

| Model 5 (males) | Central Symptoms | Bridge Symptoms |

| Desire to lose weight Feeling useless Self-dislike |

Feeling like a failure Feeling useless |

|

| Model 6 (females) | Central Symptoms | Bridge Symptoms |

| Desire to lose weight | Feeling like a failure | |

| Discomfort when seeing one’s own body |

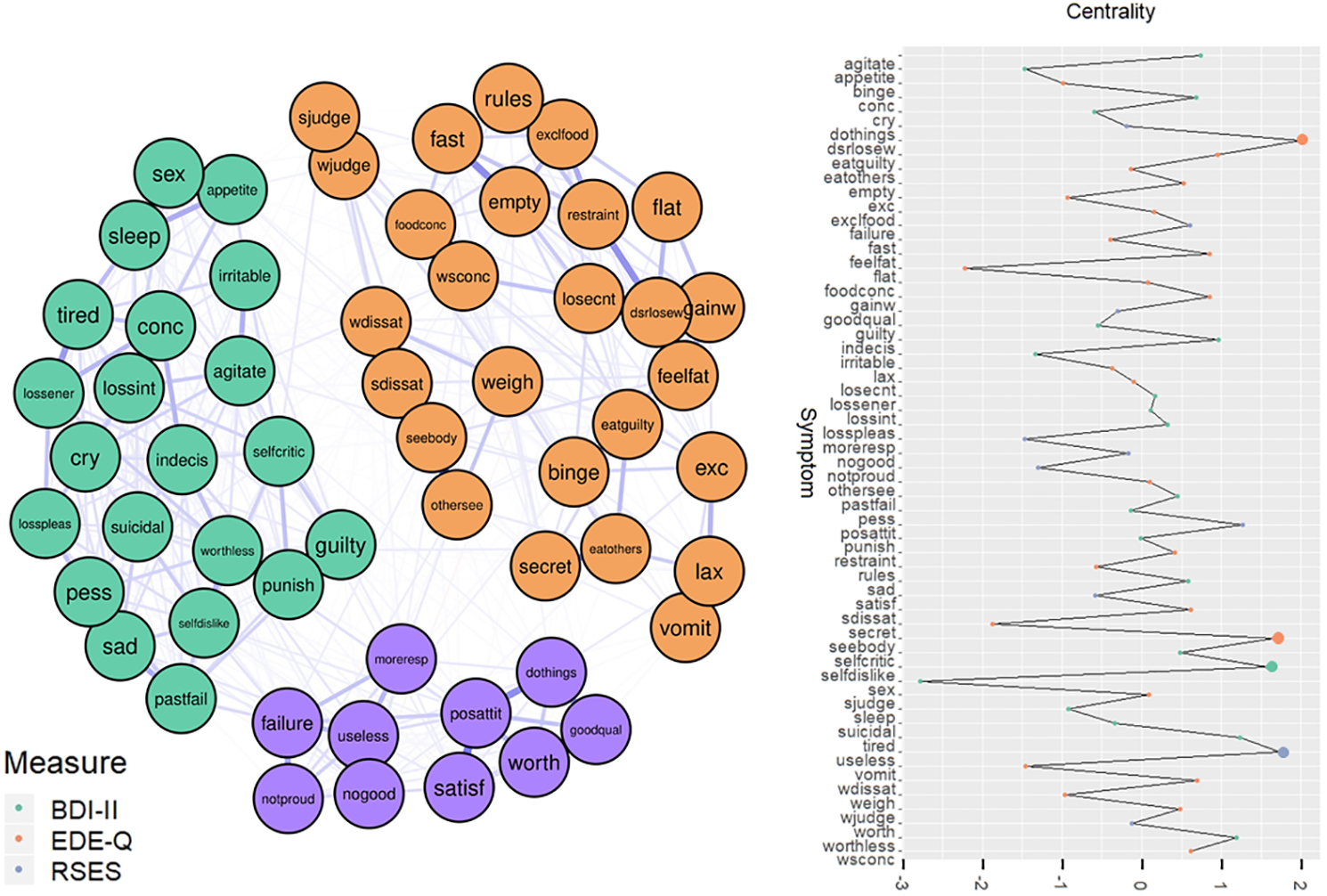

Model 2

Central symptoms.

Model 2 was stable (strength=.75, edge=.75). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: desire to lose weight (S=2.00), feeling useless (S=1.73), discomfort when seeing one’s own body (S=1.66), self-dislike (S=1.58; Figure 2 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥83.93% of other symptoms (ps<.05).

Figure 2. Model 2 network and centrality plot.

Notes: Orange items = EDE-Q items; purple items = RSES items; green items = BDI-II items. Larger dots on the centrality graph (right) denote the most central symptoms. Model 2 is made up of the full sample (N = 1,748). See Table 2 for a list of all node names and their corresponding symptoms/measure items.

Bridge symptoms.

BEI was stable (BEI stability=.75). The bridge symptom with the greatest expected influence was feeling like a failure. Feeling like a failure was connected to one disordered eating symptom and eight depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.07).

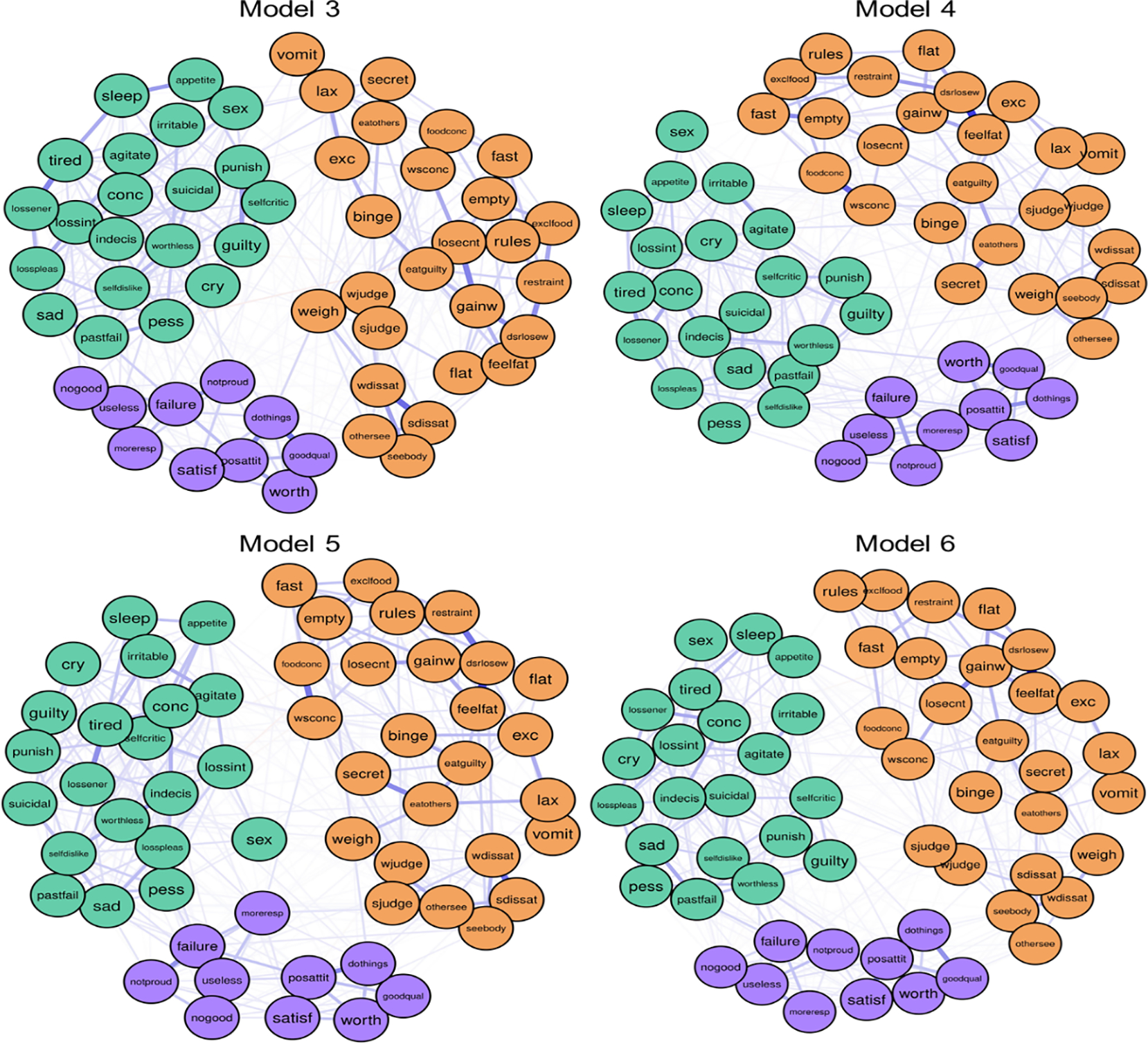

Model 3

Central symptoms.

Model 3 was stable (strength=.60, edge=.67). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: feeling worthless (S=2.26 and desire to lose weight (S=2.145; Figures 3–4 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥85.719% of other symptoms (ps<.05).

Figure 3. Models 3–6 networks.

Notes: Orange items = EDE-Q items; purple items = RSES items; green items = BDI-II items. Model 3 is made up of a college sample (n = 637). Model 4 is made up of an adolescent sample (n = 1,111). Model 5 is made up of a male sample (n = 757). Model 6 is made up of a female sample (n = 991). See Table 2 for a list of all node names and their corresponding symptoms/measure items.

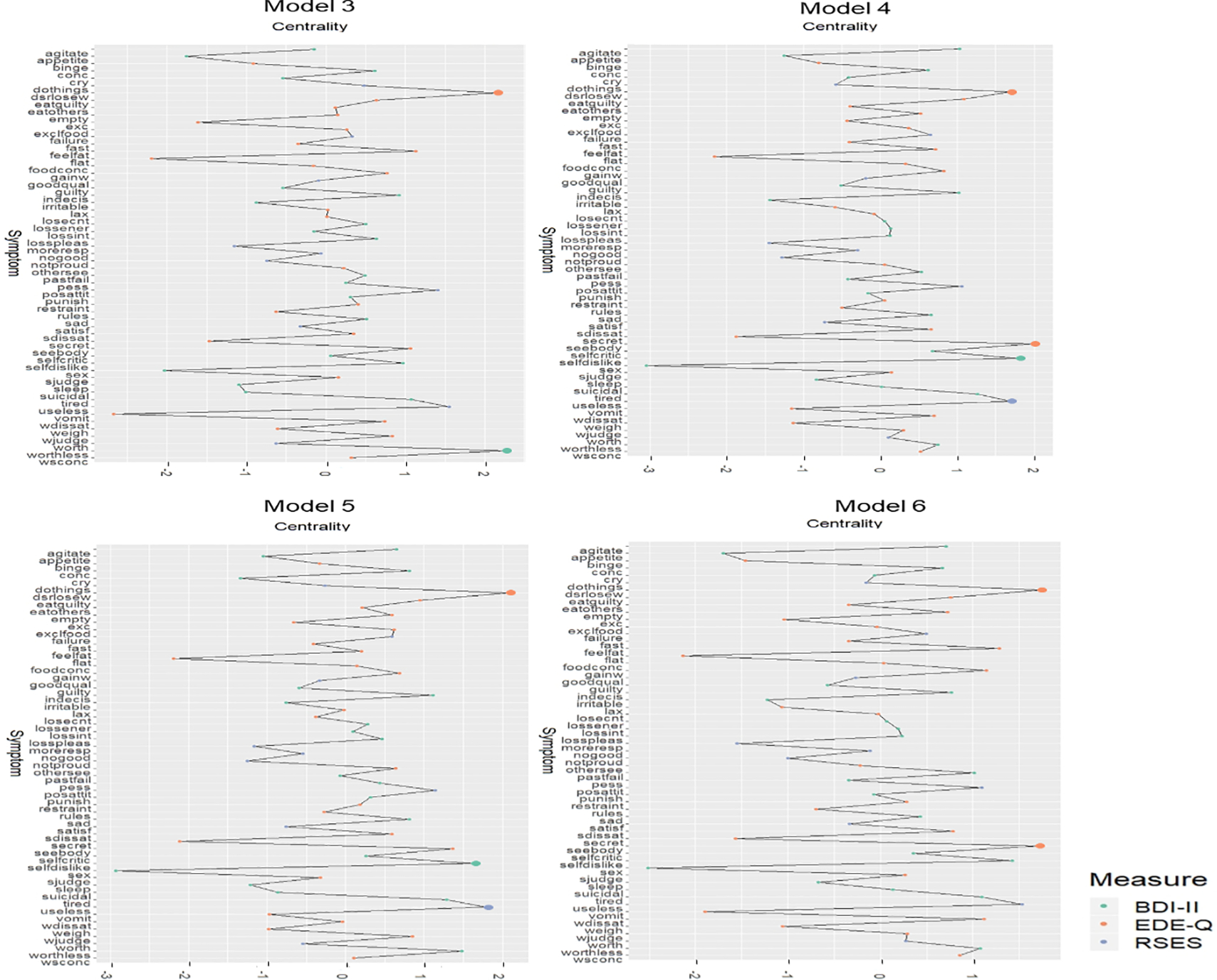

Figure 4. Models 3–6 centrality plots.

Notes: Orange items = EDE-Q items; purple items = RSES items; green items = BDI-II items. Larger dots denote the most central symptoms. Model 3 is made up of a college sample (n = 637). Model 4 is made up of an adolescent sample (n = 1,111). Model 5 is made up of a male sample (n = 757). Model 6 is made up of a female sample (n = 991). See Table 2 for a list of all node names and their corresponding symptoms/measure items.

Bridge symptoms.

BEI was stable (BEI stability=.52). The bridge symptom with the greatest expected influence were not having much to be proud of, feeling like a failure, and feeling useless. Not having much to be proud of was connected to four disordered eating symptom and two depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.05). Feeling like a failure was connected to two disordered eating symptoms and three depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.09). Feeling useless was connected to one disordered eating symptom and three depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.06).

Model 4

Central symptoms.

Model 4 was stable (strength=.75, edge=.75). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: discomfort when seeing one’s own body (S=1.99), self-dislike (S=1.79), feeling useless (S=1.70), and desire to lose weight (S=1.69; Figures 3–4 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥85.71% of the other symptoms (ps < .05).

Bridge symptoms.

BEI was stable (BEI stability=.67). The bridge symptom with the greatest expected influence was feeling like a failure. Feeling like a failure was connected to two disordered eating symptoms and ten depression symptoms (partial rs = .02–.07)

Model 5

Central symptoms.

Model 5 was stable (strength=.60, edge=.67). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: desire to lose weight (S=2.08), feeling useless (S=1.78), and self-dislike (S=1.64; Figures 3–4 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥78.57% of other symptoms (ps<.05).

Bridge symptoms.

BEI was stable (BEI stability=.52). The bridge symptoms with the greatest expected influence were feeling like a failure and feeling useless. Feeling like a failure was connected to one disordered eating symptom and six depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.07). Feeling useless was connected to one disordered eating symptom and seven depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.05).

Model 6

Central symptoms.

Model 6 was stable (strength = 75, edge=.75). The symptoms with the highest centrality were: desire to lose weight (S=1.73) and discomfort when seeing one’s own body (S=1.69; Figures 3–4 and Table 3). Strength centrality difference tests indicated that the most central symptoms had significantly greater strength than ≥82.14% of other symptoms (ps<.05).

Bridge symptoms.

BEI was stable (BEI stability=.67). The bridge symptom with the greatest expected influence was feeling like a failure. Feeling like a failure was connected to six depression symptoms (partial rs=.02–.08).

Network Comparison Tests

Model 3 (n=637 college students) was compared to Model 4 (n=1,111 adolescents). The Network Invariance test (M) and Global Strength Invariance test (GSI) indicated that the models did not significantly differ (M=.16, p=.470; GSI=.00, p=1.00). The Edge Invariance test (E) indicated that the edges between the following symptoms significantly differed: not having much to be proud of, thoughts about weight affecting concentration (E=.01, p=.040) and not having much to be proud of and fear of losing control (E=.03, p=.010), not having much to be proud of and suicidal ideation (E=.04, p<.01), and feeling like a failure and agitation (E=.03, p=.020). All other bridged edges were not significantly different (ps≥.12).

Model 5 (n=757 males) was compared to Model 6 (n=991 females). The Network Invariance test indicated that the models did not significantly differ (M=.19, p=.100). The Global Strength Invariance test was significant (GSI=.23, p=.610), indicating that the models’ overall connectivity differed from each other. The Edge Invariance test indicated that the edges between the following symptoms differed: feeling like a failure and discomfort seeing one’s own body (E=.04, p=.030), feeling like a failure and loss of pleasure (E=.07, p=.010), feeling like a failure and tiredness (E=.03, p=.040), feeling useless and guilt (E=.03, p=.020), feeling useless and indecision (E=.03, p=.050), and feeling useless and loss of energy (E=.04, p=.050). All other bridged edges were not significantly different (p>.09).

Discussion

Across networks of disordered eating, depression, and self-esteem among a large sample of Iranian adolescents and young adults, desiring to lose weight was the most central symptom. Across most models (Model 3), feeling like a failure was an influential bridge symptom. With exception of a few differences in edges, no significant differences were found in network structure or global strength. Overall, these findings are consistent with Western-based sociocultural models of EDs. We interpret our findings in the context of a literature comprised mostly of findings from Western, clinical samples. While no disordered eating networks have been compared between Western and non-Western samples, ED networks of clinical and non-clinical samples are more similar than different (Vanzhula et al., 2019; Forrest et al., 2019), which is consistent with dimensional models of EDs (Wildes & Marcus, 2013).

Central Symptoms

Desiring weight loss was the most central symptom across all models, regardless of age and sex. Findings from clinical samples also support that central ED symptoms are similar between adolescents vs. adults (e.g., Brown et al., 2020; Calugi et al., 2020; Forrest et al., 2018; Goldschmidt et al., 2018) and males vs. females (Perko, Forbush, Siew, & Tregarthen, 2019). However, a small proportion of edges differed between adolescents vs. college students. This aligns with Christian and colleagues’ (2020) findings that symptom relationships differ across age groups. Unlike most ED network studies, the items assessing shape/weight overvaluation were not highly central in this study. Potential reasons for this could be due to differences in symptom severity, culture, or both.

With respect to symptom severity differences, Western-based sociocultural theories of ED development (e.g., Pennesi & Wade, 2016; Schaefer & Thompson, 2018; Stice, 2001; Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999; Weissman, 2019) propose that thin-ideal internalization, which could manifest as desiring weight loss, is a risk factor for body dissatisfaction, which then increases risk for EDs. Indeed, two studies conducted among Iranian samples support that thin-ideal internalization is strongly and positively associated with body dissatisfaction (Shahyad, Pakdaman, Shokri, & Saadat; 2018; Sahlan, Akoury, & Taravatrooy, under review). However, body dissatisfaction is dimensional and only severe manifestations are indicative of clinical EDs (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2013). Specifically, shape and weight overvaluation manifests as the belief that one’s body shape or weight is one of the most important indicators of one’s self-worth. Shape and weight overvaluation is thought to be a critical maintenance factor for ED psychopathology (Fairburn et al., 2003) and consistently emerges as one of the most highly central symptoms in ED network studies (e.g., Forrest et al., 2018; Levinson et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Taken together, desiring weight loss emerging as central in a nonclinical sample (perhaps reflective of “normative discontent”), versus the presence of shape and weight overvaluation emerging as central in clinical samples, could be considered consistent with theories that differentiate between risk (e.g., thin-ideal internalization) vs. maintenance (e.g., shape and weight overvaluation) factors for EDs (Rodin, Silberstein, & Striegel-Moore, 1984). However, additional research is needed to empirically determine whether desiring weight loss is actually more consistent with weight dissatisfaction vs. overvaluation. We find it notable that desiring weight loss and weight overvaluation are both weight-related cognitive ED symptoms, which have strong connections to other ED network symptoms among Western and non-Western and clinical and non-clinical samples alike.

Women in Iran are mandated to wear the hijab (i.e., Islamic head cover), which may confer protective effects against extreme forms of body dissatisfaction. Indeed, comparisons of British Muslim women who do vs. do not wear the hijab reveal that women who wear the hijab place less importance on appearance than women who do not wear the hijab (Swami, Miah, Noorani, & Taylor, 2014). It may make sense that discomfort seeing one’s body was among the highly central symptoms in the full sample model (Model 2), adolescent model (Model 4), and female model (Model 6). Arguably, Iranian people have less exposure to seeing female bodies relative to cultures without mandates that women dress in hijab. While these dress codes may positively impact the way others interact with Muslim women (e.g., reduced experiences of sexual objectification; Tolaymat & Moradi, 2011) and could protect against shape and weight overvaluation, wearing the hijab may lead Muslim people to have negative reactions to seeing women’s bodies. In this cultural context, seeing women’s bodies could cue anxiety due to it being a novel and somewhat forbidden experience. Wearing the hijab may also not guarantee that women have positive experiences of seeing their own bodies. Indeed, disordered eating and key ED risk factors have a small yet notable prevalence among Iranian people (Abdollahi & Mann, 2001; Mohammadi et al., 2020; Sahlan et al., 2020).

Bridge Symptoms

Feeling like a failure was the most influential bridge symptom connecting disordered eating symptoms, depression symptoms, and self-esteem in the combined model (Model 2), the adolescent-only model (Model 4), the male-specific model (Model 5), and the female-specific model (Model 6). In the college student-only model (Model 3), not having much to be proud of, feeling like a failure, and feeling useless were the most influential bridge symptoms. Very low self-esteem may be a shared correlate or risk factor for multiple forms of psychopathology. Indeed, several network analysis studies investigated symptoms that may represent illness pathways from disordered eating to depression/anxiety (Levinson et al., 2017, 2018). Results consistently point to indicators of very low self-esteem, such as feeling like a failure or feeling worthless or useless, as bridge symptoms (Elliott et al., 2020a; Smith et al., 2018). Even though the current study sample differed from those of previous studies, the similarity in bridge symptoms is notable and consistent with dimensional approaches to psychopathology (e.g., Wildes & Marcus, 2013). Moreover, outside of network studies, a large body of research supports that self-esteem may increase risk for both depression and EDs (see review in Becker, Plasencia, Kilpela, Briggs, & Stewart, 2014).

Clinical Implications

Network theory predicts that clinical interventions targeted to central symptoms should lead to reductions in other symptoms (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Fried & Cramer, 2017). Similarly, clinical interventions targeted to bridge symptoms should theoretically improve symptoms transdiagnostically (Jones, Ma, & McNally, 2019). While some evidence supports that centrality corresponds to treatment outcomes (Elliott et al., 2020a; Olatunji, Levinson, & Calebs, 2018), item variance is also associated with treatment outcomes (Elliott et al., 2020b; Rodebaugh et al., 2018). To fully understand the utility of centrality specifically in relation to treatment outcomes, experimental and longitudinal research are needed. With this caveat in mind, results suggest that, broadly, intervention targets may change based on whether an intervention’s primary objective is to prevent EDs overall vs. prevent EDs and common comorbidities (e.g., depression).

With respect to ED prevention specifically, one prevention program that has demonstrated efficacy is the Body Project (e.g., Le, Barendregt, Hay, & Mihalopoulos, 2017). The Body Project is a dissonance-based program that directly targets thin-ideal internalization and greatly decreases risk for ED development among females (Stice, Marti, Shaw, & Rohde, 2019; Stice, Rohde, Shaw, & Gau, 2011). The Body Project has not been evaluated in Iranian people, and only preliminary evidence is available for males (Brown & Keel, 2015). Because a symptom related to thin-ideal internalization was consistently central across groups (i.e., desiring weight loss) and thin-ideal internalization is conceptualized as a “trans-ethnicity risk factor for EDs” (Stice et al., 2019, p. 103), implementation of the Body Project with Iranian adolescents and young adults could be efficacious in preventing EDs.

However, the Body Project is not designed to prevent EDs with comorbid depression and does not produce changes in depression over time (Christian et al., 2019; Stice et al., 2011). If a prevention program intends to target both disordered eating and comorbid symptoms, intervening on shared risk factors may be necessary (Becker et al., 2014). In the case of preventing both disordered eating and depression, prevention efforts may need to target low self-esteem. Indeed, a version of the effective Student Bodies prevention program (Jacobi, Völker, Trockel, & Taylor, 2012) designed to reduce ED and comorbid pathology among those at very high risk for ED onset was shown to be more effective than controls in improving ED attitudes and behaviors (Taylor et al., 2016) and could be adapted for use in Iran. Media literacy approaches have also demonstrated efficacy (Wilksch et al., 2017, 2018) and should be evaluated in this context.

Strengths and Limitations

A notable strength is investigating how disordered eating and other psychological symptoms interconnect among Middle Eastern adolescents and adults. Moreover, we investigated differences by age and sex. This is important considering that most disordered eating theories and research are based on findings among women, and the extent to which these generalize to men remains understudied.

Several limitations deserve mention. First, we included a non-clinical sample. While this is consistent with dimensional models of EDs, results do not indicate which symptoms may be at the core of ED psychopathology among Iranian individuals with EDs. Second, our study was cross-sectional and utilized single items as indicators of symptoms. To enhance reliability and validity of findings, future studies should consider inclusion of composite measures instead of single items. Third, although Bringmann and colleagues (2019) suggest that strength centrality is the best current measure of network centrality, the reliability and validity of strength centrality have limits as is the case with any statistical analysis. Future research may benefit from replicating these findings and measuring the reliability and validity of strength centrality, as well as identifying alternative measures of centrality in network analysis. Fourth, our assessment of disordered eating did not include items specifically tailored to males, which may be needed to fully capture the extent of males’ symptoms (Forrest et al., 2019). Fifth, item variability may influence centrality (Elliott et al., 2020b). Continued work is needed to determine (1) the utility of centrality in predicting treatment outcomes and (2) mechanisms explaining why item variability and/or centrality are related to treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that desiring weight loss was the most central item, which is consistent with sociocultural theories of ED development and transdiagnostic models of EDs. Feeling like a failure was the central bridge symptom in most networks, which is consistent with the conceptualization of very low self-esteem as a shared risk factor for both disordered eating symptoms and depression. Results are largely consistent with Western conceptualizations of EDs and identify potential targets for the prevention of disordered eating and depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health grant K08 MH120341.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding or first author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abdollahi P, & Mann T (2001). Eating disorder symptoms and body image concerns in Iran: Comparisons between Iranian women in Iran and in America. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30(3), 259–268. 10.1002/eat.1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzali MH, Sunderland M, Batterham PJ, Carragher N, Calear A, & Slade T (2017). Network approach to the symptom-level association between alcohol use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52, 329–339. 10.1007/s00127-016-1331-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bagley C, & Mallick K (2001). Normative data and mental health construct validity for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in British adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 9(2–3), 117–126. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2001.9747871 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Plasencia M, Kilpela LS, Briggs M, & Stewart T (2014). Changing the course of comorbid eating disorders and depression: What is the role of public health interventions in targeting shared risk factors? Journal of Eating Disorders, 2:15. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-2-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. doi: 10.1002/wps.20375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, & Cramer AO (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, Mellenbergh GJ, & van Heerden J (2003). The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review, 110(2), 203–219. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.2.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechan I, & Kvalem IL (2015). Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eating Behaviors, 17, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, Krause RW, Schoch D, Wichers M, Wigman JTW, & Snippe E (2019). What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(8), 892–903. 10.1037/abn0000446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Vanzhula IA, Reilly EE, Levinson CA, Berner LA, Krueger A, … Wierenga CE (2020). Body mistrust bridges interoceptive awareness and eating disorder symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, & Keel PK (2015). A randomized controlled trial of a peer co-led dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for gay men. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 1–10. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrard I, Rebetez MM, Mobbs O, & Van der Linden M (2015). Factor structure of a French version of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire among women with and without binge eating disorder symptoms. Eating and Weight Disorders, 20(1), 137–144. doi: 10.1007/s40519-014-0148-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calugi S, Sartirana M, Misconel A, Boglioli C, & Dalle Grave DR (2020). Eating disorder psychopathology in adults and adolescents with anorexia nervosa: A network approach. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.23270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KM, Batchelder AW, Ehlinger PP, Safren SA & O’Cleirigh C (2017). Applying network analysis to psychological comorbidity and health behavior: Depression, PTSD, and sexual risk in sexual minority men with trauma histories. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12). 1158–1170. 10.1037/ccp0000241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian C, Brosof LC, Vanzhula IA, Williams BM, Shankar Ram S, & Levinson CA (2019). Implementation of a dissonance-based, eating disorder prevention program in Southern, all-female high schools. Body Image, 30, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian C, Perko VL, Vanzhula IA, Tregarthen JP, Forbush KT, & Levinson CA (2020). Eating disorder core symptoms and symptom pathways across developmental stages: A network analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1037/abn0000477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois RH, Rodgers RF, Franko DL, Eddy KT, & Thomas JJ (2017). A network analysis investigation of the cognitive-behavioral theory of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 97, 213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott H, Jones PJ, & Schmidt U (2020a). Central symptoms predict pos-treatment outcomes and clinical impairment in anorexia nervosa: A network analysis. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(1), 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott H, Jones PJ, & Schmidt U (2020b). Corrigendum: Central Symptoms Predict Posttreatment Outcomes and Clinical Impairment in Anorexia Nervosa: A Network Analysis. (2020). Clinical Psychological Science, 8(2), 388–389. 10.1177/2167702620908574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, & Fried EI (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittman VD, & Bosboom D (2012). qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, & Fried EI (2020). Package ‘bootnet.’ R package version 1.3. [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, & Fried EI (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, & Shafran R (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LN, Jones PJ, Ortiz SN, & Smith AR (2018). Core psychopathology in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A network analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(7), 668–679. doi: 10.1002/eat.22871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LN, Perkins NM, Lavender JM, & Smith AR (2019). Using network analysis to identify central eating disorder symptoms among men. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(8), 871–884. doi: 10.1002/eat.23123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LN, Sarfan LD, Ortiz SN, Brown TA, & Smith AR (2019). Bridging eating disorder symptoms and trait anxiety in patients with eating disorders: A network approach. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(6), 701–711. doi: 10.1002/eat.23070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC (1978). Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social Networks, 1(3), 215–239. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fried EI, & Cramer AOJ (2017). Moving Forward: Challenges and Directions for Psychopathological Network Theory and Methodology. Perspective on Psychological Science, 12(6), 999–1020. doi: 10.1177/1745691617705892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, & Ebrahimkhani N (2005). Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory - Second edition: BDI-II-Persian. Depression and Anxiety, 21(4), 185–192. doi: 10.1002/da.20070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Moessner M, Forbush KT, Accurso EC, & Le Grange D (2018). Network analysis of pediatric eating disorder symptoms in a treatment-seeking, transdiagnostic sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(2), 251–264. doi: 10.1037/abn0000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Völker U, Trockel MT, & Taylor CB (2012). Effects of an Internet-based intervention for subthreshold eating disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(2), 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalali-Farahani S, Chin YS, Nasir MTM, & Amiri P (2015). Disordered eating and its association with overweight and health-related quality of life among adolescents in selected high schools of Tehran. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46(3), 485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson PM, Taylor L, & Laws KR (2018). Self-reported interoceptive deficits in eating disorders: A meta-analysis of studies using the eating disorder inventory. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 110, 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P (2019). Network tools. R package version 1.2.1 [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ, Ma R, & McNally RJ (2019). Bridge centrality: A network approach to comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1:15. 10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le LK, Barendregt JJ, Hay P, & Mihalopoulos C (2017). Prevention of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Brosof LC, Vanzhula I, Christian C, Jones P, Rodebaugh TL, … Fernandez KC (2018). Social anxiety and eating disorder comorbidity and underlying vulnerabilities: Using network analysis to conceptualize comorbidity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(7), 693–709. doi: 10.1002/eat.22890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson CA, Zerwas S, Calebs B, Forbush K, Kordy H, Watson H, … Bulik CM (2017). The core symptoms of bulimia nervosa, anxiety, and depression: A network analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(3), 340–354. doi: 10.1037/abn0000254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Donnellan MB, Burt SA, & Klump KL (2016). The dimensional nature of eating pathology: Evidence from a direct comparison of categorical, dimensional, and hybrid models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 715–726. doi: 10.1037/abn0000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ (2016). Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi MR, Mostafavi SA, Hooshyari Z, Khaleghi A, Ahmadi N, Molavi P, … & Zarafshan H (2020). Prevalence, correlates and comorbidities of feeding and eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of Iranian children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(3), 349–361. doi: 10.1002/eat.23197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond J, Hall A, Bentley C, Harrison C, Gratwick-Sarll K, & Lewis V (2014). Eating-disordered behavior in adolescent boys: Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire norms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(4), 335–341. doi: 10.1002/eat.22237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone AM, Mereu A, Cascino G, Criscuolo M, Castiglioni MC, Pellegrino F, … Zanna V (2019). Re-conceptualization of anorexia nervosa psychopathology: A network analysis study in adolescents with short duration of the illness. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(11), 1263–1273. doi: 10.1002/eat.23137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Levinson C, & Calebs B (2018). A network analysis of eating disorder symptoms and characteristics in an inpatient sample. Psychiatry Research, 262, 270–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli-Pott U, Becker K, Albayrak Ö, Hebebrand J, & Pott W (2013). Links between psychopathological symptoms and disordered eating behaviors in overweight/obese youths. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(2), 156–163. doi: 10.1002/eat.22055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, & Stein MB (2010). Interoception in anxiety and depression. Brain Structure & Function, 214(5–6), 451–463. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0258-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennesi JL, & Wade TD (2016). A systematic review of the existing models of disordered eating: Do they inform the development of effective interventions?. Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 175–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perko VL, Forbush KT, Siew CSQ, & Tregarthen JP (2019). Application of network analysis to investigate sex differences in interactive systems of eating-disorder psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(12). doi: 10.1002/eat.23170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell K, Stice E, Seidel A, & Madeley MC (2009). Depression and eating pathology: prospective reciprocal relations in adolescents. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 16(4), 357–365. doi: 10.1002/cpp.630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puccio F, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Youssef G, Mitchell S, Byrne M, Allen N, & Krug I (2017). Longitudinal Bi-directional Effects of Disordered Eating, Depression and Anxiety. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(5), 351–358. doi: 10.1002/erv.2525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauof M, Ebrahimi H, Jafarabadi MA, Malek A, & Kheiroddin JB (2015). Prevalence of eating disorders among adolescents in the Northwest of Iran. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(10), e19331. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, LeBlanc NJ, Vuletich HA, & McNally RJ (2014). Network analysis of persistent complex bereavement disorder in conjugally bereaved adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(3). 510–522. 10.1037/abn0000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Tonge NA, Piccirillo ML, Fried E, Horenstein A, Morrison AS, … Heimberg RG (2018). Does centrality in a cross-sectional network suggest intervention targets for social anxiety disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(10), 831–844. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, Silberstein L, & Striegel-Moore R (1984). Women and weight: A normative discontent. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 32, 267–307. PMID: 6398857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzano L, Borsboom D, & Geurts HM (2015). Repetitive behaviors in autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder: New perspectives from a network analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(1), 192–202. 10.1007/s10803-014-2204-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rø Ø, Reas DL, & Stedal K (2015). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in Norwegian adults: Discrimination between female controls and eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review, 23(5), 408–412. doi: 10.1002/erv.2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlan RN, Akoury LM, & Taravatrooy F Validation of a Farsi version of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (F-SATAQ-4) in Iranian men and women. Under review. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sahlan RN, Taravatrooy F, Quick V, & Mond JM (2020). Eating-disordered behavior among male and female college students in Iran. Eating Behaviors, 37, 101378. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, Richards CS, & Bleckley MK (2007). Comorbidity between depression and disordered eating in adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 8(4), 440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer LM, & Thompson JK (2018). Self-objectification and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(6), 483–502. doi: 10.1002/eat.22854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahyad S, Pakdaman S, Shokri O, & Saadat SH (2018). The role of individual and social variables in predicting body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms among Iranian adolescent girls: An expanding of the Tripartite Influence Mode. European Journal of Translational Myology, 28(1), 7277–7277. doi: 10.4081/ejtm.2018.7277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapurian R, Hojat M, & Nayerahmadi H (1987). Psychometric Characteristics and Dimensionality of a Persian Version of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 65(1), 27–34. doi: 10.2466/pms.1987.65.1.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair SJ, Blais MA, Gansler DA, Sandberg E, Bistis K, & LoCicero A (2010). Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Overall and across semographic groups living within the United States. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 33(1), 56–80. doi: 10.1177/0163278709356187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Forbush KT, Mason TB, & Moessner M (2018). Network analysis: An innovative framework for understanding eating disorder psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 51(3), 214–222. doi: 10.1002/eat.22836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(1), 124–130. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, & Rohde P (2019). Meta-analytic review of dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Intervention, participant, and facilitator features that predict larger effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 91–107. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, & Gau J (2011). An effectiveness trial of a selected dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for female high school students: Long-term effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 500–508. doi: 10.1037/a0024351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami V, Miah J, Noorani N, & Taylor D (2014). Is the hijab protective? An investigation of body image and related constructs among British Muslim women. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 352–363. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CB, Kass AE, Trockel M, Cunning D, Weisman H, Bailey J, … Wilfley DE (2016). Reducing eating disorder onset in a very high risk sample with significant comorbid depression: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 402–414. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, & Tantleff-Dunn S (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association, Washington DC. doi: 10.1037/10312-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 58(1), 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tolaymat LD, & Moradi B (2011). U.S. Muslim women and body image: Links among objectification theory constrcuts and the hijab. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Borkulo C, Boschloo L, Bosboom D, Penninx BWJH, Waldorp LJ, & Schoevers RA (2016). Association of symptom network structure with the course of depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1219–1226. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzhula IA, Calebs B, Fewell L, & Levinson CA (2019). Illness pathways between eating disoreder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: Understanding comorbidity with network analysis. European Eating Disorders Review, 27, 147–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SB, Jones PJ, Dreier M, Elliott H, & Grilo CM (2019). Core psychopathology of treatment-seeking patients with binge-eating disorder: A network analysis investigation. Psychological Medicine, 49(11), 1923–1928. doi: 10.1017/s0033291718002702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman RS (2019). The role of sociocultural factors in the etiology of eating disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 42(1), 121–144. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildes JE, & Marcus MD (2013). Incorporating dimensions into the classification of eating disorders: Three models and their implications for research and clinical practice. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(5), 396–403. 10.1002/eat.22091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch SM, O’Shea A, Taylor CB, Wilfley D, Jacobi C, & Wade TD (2018). Online prevention of disordered eating in at-risk young-adult women: A two-country pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 48(12), 2034–2044. doi: 10.1017/s0033291717003567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilksch SM, Paxton SJ, Byrne SM, Austin SB, O’Shea A, & Wade TD (2017). Outcomes of three universal eating disorder risk reduction programs by participants with higher and lower baseline shape and weight concern. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(1), 66–75. doi: 10.1002/eat.22642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.