Abstract

Plants belonging to the genus Hypericum (Hypericaceae) are recognized as an abundant source of natural products with interesting chemical structures and intriguing biological activities. In the course of our continuing study on constituents of Hypericum plants, aiming at searching natural product-based lead compounds for therapeutic agents, we have isolated more than 100 new characteristic metabolites classified as prenylated acylphloroglucinols, meroterpenes, ketides, dibenzo-1,4-dioxane derivatives, and xanthones including prenylated xanthones, phenylxanthones, and xanthonolignoids from 11 Hypericum plants and one Triadenum plant collected in Japan, China, and Uzbekistan or cultivated in Japan. This review summarizes their chemical structures and biological activities.

Keywords: Hypericum, Hypericaceae, Characteristic metabolite, Chemical structure, Biological activity

Introduction

Hypericum plants of the family Hypericaceae, consisting of over 500 perennial herbs or shrubs subdivided into 30 sections, are mainly distributed in temperate area [1]. Some of Hypericum plants have been used as traditional remedies in various parts of the world. A number of researches on the constituents of Hypericum plants have resulted in the isolation of various classes of natural products including terpenoids, flavonoids, xanthones, naphthodianthrones, and prenylated acylphloroglucinols (PAPs) [2]. Among others, hypericin, a naphthodianthrone derivative found in Hypericum plants belonging to the sections Hypericum, Adenotras, and Drosocarpium, is recognized as one of the most potent naturally occurring photodynamic agents [3]. PAPs are specialized metabolites of plants belonging to some genera of the Hypericaceae and Clusiaceae families including Hypericum, Garcinia, Clusia, and so on [4–6], while several meroterpenes structurally and biosynthetically related to PAPs have also been reported from these plant species [7]. Since diverse and complex chemical structures and intriguing biological activities of the PAPs have attracted huge interests of researchers, some excellent systematic reviews for PAPs have been published [4–6, 8].

Our research group has been conducting a study searching for new plant metabolites with unique chemical structures and biological activities [9–11]. In the course of this research project, we investigated 11 Hypericum species belonging to the sections Roscyna (H. ascyron), Ascyreia (H. monogynum and H. patulum), Hypericum (H. sikokumontanum, H. kiusianum, H. yojiroanum, H. yezoense, and H. erectum), Myriandra (H. frondosum ‘Sunburst’), Elodeoida (H. elodeoides), and Hirtella (H. scabrum) collected in Japan, China, and Uzbekistan or cultivated in Japan together with one species of Triadenum (T. japonicum), a sister genus of Hypericum, to isolate more than 100 of new characteristic metabolites. In this review, their chemical structures and biological activities as well as related studies conducted by other research groups are summarized.

PAPs, prenylated xanthones, and dibenzo-1,4-dioxane from Hypericum ascyron (section Roscyna)

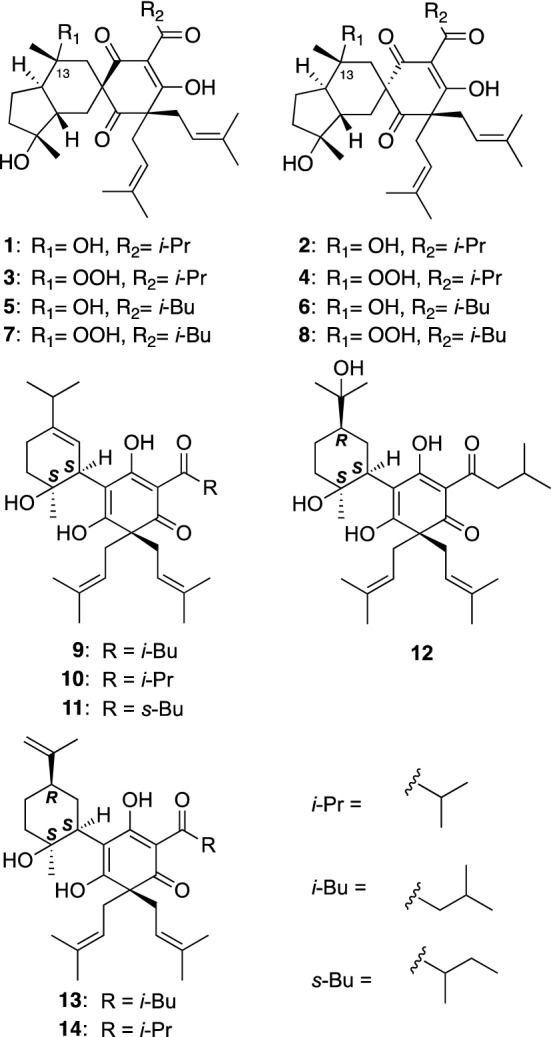

Hypericum ascyron (Tomoesou in Japanese) is a perennial herb widely distributed in eastern Asia, and the whole plants have been used as an herbal medicine to treat headache, wounds, and abscesses in China. The whole plants of H. ascyron collected in Tokushima prefecture, Japan were separated into the aerial parts and roots. Their chemical constituents were separately investigated by chromatographic techniques to isolate some PAPs (1–15). Their structures were established based on spectroscopic analyses. Tomoeones A–H (1–8) isolated from the aerial parts of H. ascyron were assigned as the first example of spirocyclic PAPs (Fig. 1) [12], whereas about 50 related spirocyclic PAPs have been isolated from some Hypericum plants to date [4]. The hydroxy substituents and the relative configurations of C-13 in tomoeones C (3), D (4), G (7), and H (8) have been revised by Zhang et al. [13]. Antiproliferative activity of tomoeones A–H (1–8) against human tumor cell lines including multidrug-resistant (MDR) cancer cell lines was evaluated to show a significant cytotoxicity of 6 against KB cells with an IC50 value of 6.2 μM [12]. Tomoeone F (6) also exhibited antiproliferative activity against MDR cancer cell lines (KB-C2 and K562/Adr), which was more potent than doxorubicin.

Fig. 1.

The structures of tomoeones A–H (1–8), hypascyrins A–E (9–13), and ent-hyphenrone J (14) isolated from Hypericum ascyron

Investigation of H. ascyron roots gave six new PAPs with menthane moieties, hypascyrins A–E (9–13) and ent-hyphenrone J (14) (Fig. 1) [14]. The absolute configuration of 9 was deduced by comparison of experimental and time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculated electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra, while those of 10–14 were assigned by ECD analyses as well as chemical conversions. Hypascyrins A (9), C (11), and E (13), and ent-hyphenrone J (14) exhibited potent antimicrobial activities against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (MIC50 values of 4.0, 8.0, 2.0, and 4.0 μM, respectively, for seven strains) and Bacillus subtilis (MIC values of 4.0, 4.0, 2.0, and 4.0 μM, respectively).

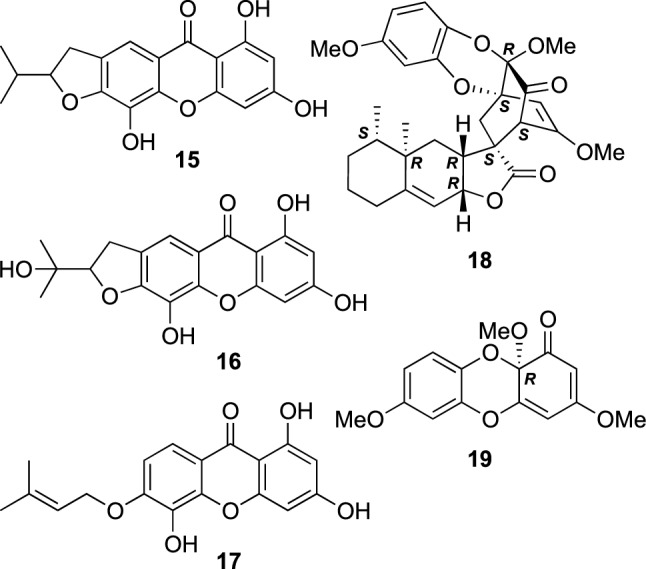

Hypericum plants are known to be a rich source of aromatic compounds including xanthones. Some prenylated xanthones, 1,3,5-trihydroxy-6,7-[2′-(1-methylethenyl)-dihydrofurano]-xanthone (15), 1,3,5-trihydroxy-6,7-[2′-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)-dihydrofurano]-xanthone (16), and 1,3,5-trihydroxy-6-O-prenylxanthone (17) were isolated from the aerial parts of H. ascyron (Fig. 2) [15]. In contrast, the roots of H. ascyron were studied to isolate two naturally rare dibenzo-1,4-dioxane derivatives, hyperdioxanes A (18) and B (19) (Fig. 2) [16]. Hyperdioxane A (18) is a unique conjugate of 19 and a sesquiterpene, eremophil-9,11(13)-dien-8β,12-olide, possessing an unprecedented heptacyclic ring system. The structures of 18 and 19 were assigned by detailed spectroscopic analyses, including application of a modified Mosher’s method to a derivative of 19. An evaluation of biological activity of 18 and 19 is ongoing.

Fig. 2.

The structures of prenylated xanthones (15–17) and hyperdioxanes A (18) and B (19) isolated from Hypericum ascyron

PAPs, meroterpenes, and xanthones from Hypericum monogynum and H. patulum (section Ascyreia)

Hypericum monogynum (syn. H. chinense var. salicifolium) (Biyouyanagi in Japanese), an evergreen shrub originated in China, is cultivated as an ornamental plant in Japan. Its stems and leaves have been used for the treatment of female disorders in Japan. In contrast, the roots of this plant have been used to treat various disorders, such as rheumatism, snakebite, and furuncle, in China. Chemical constituents of the roots, stems, and leaves of H. monogynum cultivated in Tokushima prefecture were separately and thoroughly investigated to isolate new characteristic metabolites. Chipericumins A–D (20–23) are spirocyclic PAPs isolated from the roots (Fig. 3) [17], of which chipericumins A (20) and B (21) have a unique 5/6/6/5 tetracyclic ring system. Chinesins I and II (Fig. 3), PAPs previously isolated from the same plant by Tada et al. [18], might be biogenetic precursors of 20–23. Unique meroterpenes structurally related to 20–23, biyoulactones A–E (24–28), were also isolated from the roots of H. monogynum. Among others, biyoulactones A–C (24–26) are novel pentacyclic meroterpenes possessing bi- and tricyclic γ-lactone moieties connected through a C–C single bond [19]. The structure including the absolute configuration of biyoulactone A (24) was assigned by a combination of NMR and single crystal X-ray diffraction analyses. Biyoulactones D (27) and E (28) are PAP-related meroterpenes having an octahydroindene ring, a γ-butyrolactone ring, and an enolized β-diketone moiety [20]. Their relative configurations were deduced based on NOESY data aided with computational conformational analysis.

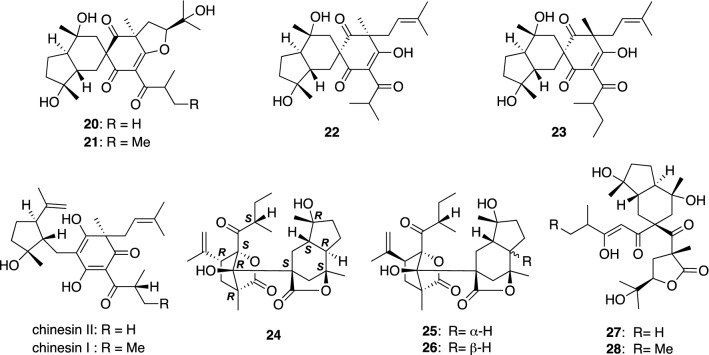

Fig. 3.

The structures of chipericumins A–D (20–23) and biyoulactones A–E (24–28) as well as chinesins I and II isolated from Hypericum monogynum

From the leaves of H. monogynum, we isolated biyouyanagins A (29) and B (30) (Fig. 4) [21, 22], novel meroterpenes possessing a unique 6/4/5/5 tetracyclic ring system including a spiro-lactone moiety, and proposed their biogenetic pathway from a sesquiterpene (ent-zingiberene) and a spiro-lactone derivative (hyperolactone C), of which the latter had been reported from the same plant by Tada et al. [23] (Fig. 4). The total syntheses of 29 and 30 proceeded by Nicolaou et al. resulted in the revision of the stereochemistries of 29 and 30 [24–26]. Xie et al. also achieved the total synthesis of 29 [27]. Biyouyanagin A (29) exhibited a potent and selective inhibitory effect on HIV replication in H9 lymphocytes with therapeutic index (TI) value of > 31.3 [21]. Furthermore, 29 inhibited LPS-induced cytokine productions (IL-10, IL-12, and TNF-α) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells [21]. An analogue of biyouyanagin A (29) possessing more potent biological activity was discovered by Nicolaou et al. in their synthetic study on analogues of 29 [28, 29]. 5,6-Dihydrohyperolactone D (31) and 4-hydroxyhyperolactone D (32) are simple linear meroterpenes co-isolated with biyouyanagins (Fig. 4) [22], while Xie et al. reported the biomimetic synthesis of 32 [30].

Fig. 4.

The structures of biyouyanagins A (29) and B (30), 5,6-dihydrohyperolactone D (31), 4-hydroxyhyperolactone D (32), and merohyperins A–C (33–35) isolated from Hypericum monogynum as well as biyouyanagin A analogue and hyperolactones A and C

Further investigation on the constituents of H. monogynum leaves gave merohyperins A–C (33–35) (Fig. 4) [31], of which merohyperins A (33) and B (34) had a novel carbon skeleton. Comparison of the experimental and DFT calculated 13C NMR data implied the geometory of a double bound in 34 to be E. Merohyperin C (35) was obtained as a separable epimeric mixture, and the structure of 35 was assigned by chemical conversion of a known meroterpene, hyperolactone A (Fig. 4) [23] into 35 [31].

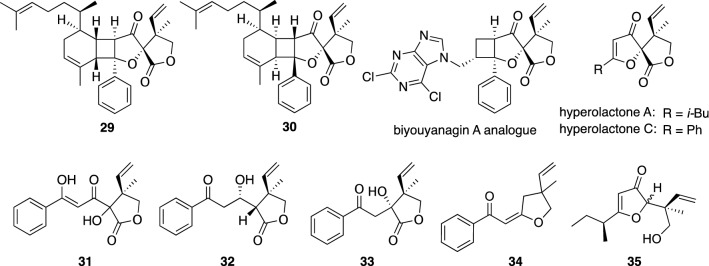

We reported the isolation of about 50 xanthones from the leaves and stems of H. monogyum [32–35], of which one was phenylxanthone, four were prenylated xanthones, five were xanthonolignoids, and others were simple xanthones with hydroxy and/or methoxy groups. Among them, chinexanthone (36), two prenylated xanthones (37 and 38), and 2-demethylkielcorin (39) were new compounds (Fig. 5). Ten simple xanthones, 4,6-dihydroxy-2,3-dimethoxyxanthone, 2,6-dihydroxy-3,4-dimethoxyxanthone, 6-hydroxy-2,3,4-trimethoxyxanthone, 3,6-dihydroxy-1,2-dimethoxyxanthone, 4,7-dihydroxy-2,3-dimethoxyxanthone, 3,7-dihydroxy-2,4-dimethoxyxanthone, 1,3,7-trihydroxy-5-methoxyxanthone, 1,7-dihydroxy-5,6-dimethoxyxanthone, 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-dimethoxyxanthone, and 1,3-dihydroxy-2,4-dimethoxyxanthone, were also identified to be new compounds [32, 33]. Chinexanthone (36), possessing a phenyl substituent in xanthone skeleton, appeared to be a new class of xanthones as phenylxanthone [34]. Many xanthonolignoid, a class of xanthone fused with a C6-C3 moiety forming a 1,4-dioxane ring, reported previously were isolated as racemic mixtures. In contrast, the xanthonolignoids including 2-O-demethylkielcorin (39) isolated by our study were shown to be a partial racemate {[α]D + 15.4 (c 0.5, MeOH)}. Assignments of the absolute configuration for the major enantiomer of 39 as well as the ratio of enantiomers (88:12) were elucidated by analyzing their MTPA ester derivatives [34]. We evaluated antiproliferative activities of the xanthones isolated from H. monogynum against a panel of human cancer cell lines including MDR human cancer cell lines [34]. Though most xanthones were non-cytotoxic, some xanthones were shown to be more toxic against MDR cancer cells.

Fig. 5.

The structures of chinexanthone (36), prenylated xanthones (37 and 38), 2-demethylkielcorin (39), and biyouxanthones A–D (40–43) isolated from Hypericum monogynum

Biyouxanthones A–D (40–43) are highly prenylated xanthones isolated from the roots of H. monogynum (Fig. 5) [35]. Biyouxanthones A (40) and B (41) inhibited the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein level in the culture of HCV-infected human hepatoma Huh7 cells (89% and 61%, respectively) at 10 μM. Luo et al. showed a neuroprotective effect against corticosterone-induced lesions of PC12 cells and an inhibitory effect on NO production in LPS-induced BV2 microglia cells of biyouxanthone D (43) [36].

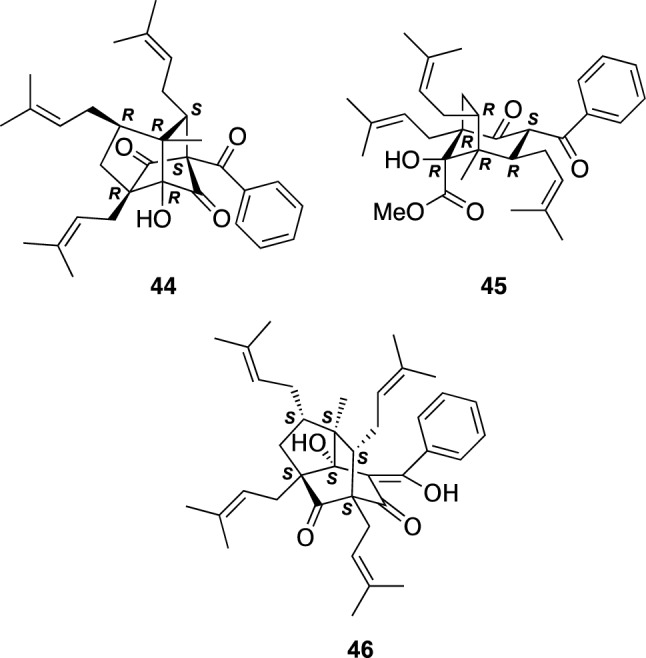

Two PAP-related meroterpenes, hypatulins A (44) and B (45), and a PAP, hypatulin C (46), were isolated from the leaves of H. patulum (Kinshibai in Japanese), an evergreen shrub originated from China (Fig. 6) [37, 38]. Hypatulin A (44) had a unique densely substituted tricyclic octahydro-1,5-methanopentalene core. The absolute configuration of 44 was elucidated on the basis of TDDFT calculation of ECD spectrum, while chemical conversion of 44 into 45 led to the assignment of that of 45. Hypatulin C (46) had a tricyclic [4.3.1.03,7]-decane core highly substituted by prenyl groups, whose absolute configuration was also deduced on the basis of ECD calculation. Hypatulin A (44) exhibited a moderate antimicrobial activity against B. subtilis [37].

Fig. 6.

The structures of hypatulins A–C (44–46) isolated from Hypericum patulum

PAPs, chromone glucosides, chromanone glucosides, and meroterpenes from Hypericum sikokumontanum, H. kiusianum, H. yojiroanum, H. yezoense, and H. erectum (section Hypericum)

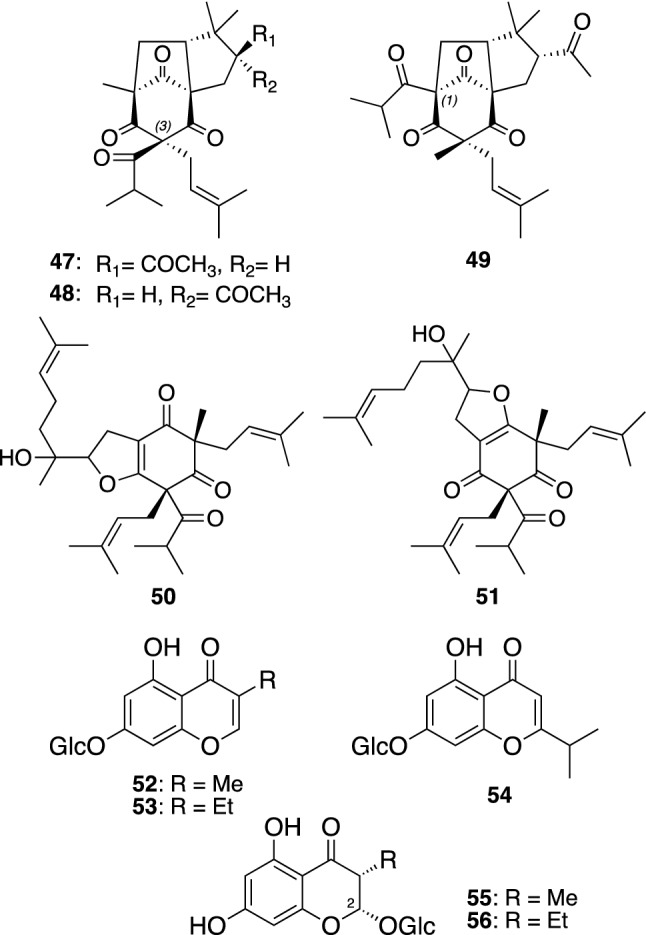

Hypericum sikokumontanum (Takane-otogiri in Japanese) is a perennial herb grown on mountain areas more than 1,400 m above the sea level in Shikoku island, Japan. Phytochemical investigation of the aerial parts of H. sikokumontanum afforded five PAPs, three chromone glucosides, and two chromanone glucosides [39, 40]. Takaneones A–C (47–49) are PAPs possessing a tricyclic moiety including a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4,8-trione core with a characteristic C4 alkyl moiety (Fig. 7) [39]. Although a large number of polycyclic PAPs possessing a bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-2,4,9-trione or bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4,8-trione have been reported from various Hypericaceous and Clusiaceous plants, they could be divided into two classes (types A and B) depending on the relative position of the acyl group on the phloroglucinol moiety [4, 5]. Namely type A PAPs have the acyl groups at C-1 position of their phloroglucinol moieties, while the acyl groups of type B PAPs are located at C-3 position [4]. Takaneones A (47) and B (48) are type B PAPs, whereas takaneone C (49) is the first example of type A PAP with a bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4,8-trione core. Takaneols A (50) and B (51) are PAPs with a dihydrofuran moiety fused to the phloroglucinol moiety [39]. The enantiospecific synthesis of the tricyclic core of takaneones A–C (47–49) was conducted by Srikrishna et al. [41]. Takaneones B (48) and C (49) and takaneol A (50) showed cytotoxicities against K562/Adr MDR cancer cells with IC50 values ranging from 4.7 to 10.0 μg/mL, which were slightly more potent than doxorubicin. Their potency of cytotoxicity against MDR cancer cell lines (KB-C2 and K562/Adr) was similar to those against sensitive cell lines (KB and K562) [39].

Fig. 7.

The structures of takaneones A–C (47–49), takaneols A (50) and B (51), takanechromones A–C (52–54), and takanechromanones A (55) and B (56) isolated from Hypericum sikokumontanum

Takanechromones A–C (52–54) and takanechromanones A (55) and B (56) are simple chromone glucosides and chromanone glucosides, respectively (Fig. 7) [40]. They are considered to be cyclized products of acylphloroglucinols with amino acid-derived acyl starters, and 55 and 56 are the first 2-hydroxychromanone derivatives from natural source [42]. 5,7-Dihydroxy-3-methylchromone and 5,7-dihydroxy-3-ethylchromone, aglycones of 52 and 53, respectively, co-isolated with 52–56 in our study, exhibited an antimicrobial activity against Helicobacter pylori and antiproliferative activities against MDR cancer cell lines [40]. Takanechromone C (54) was also isolated from a Rosaceous plant Agrimonia pilosa by Li et al. [43].

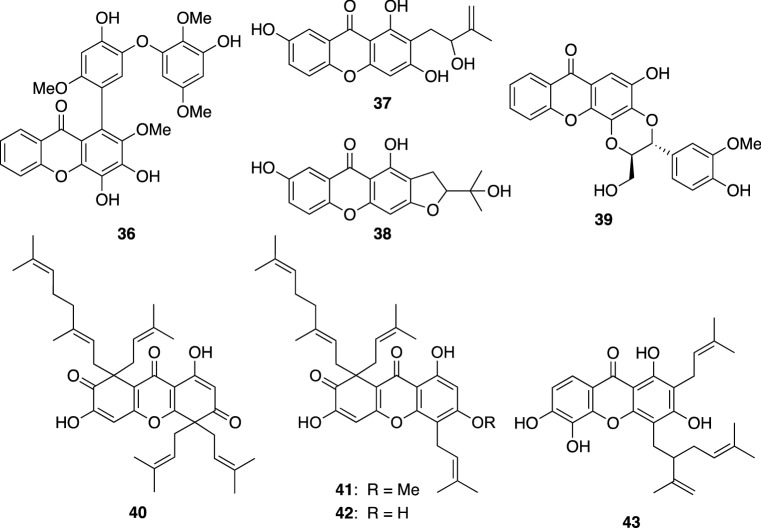

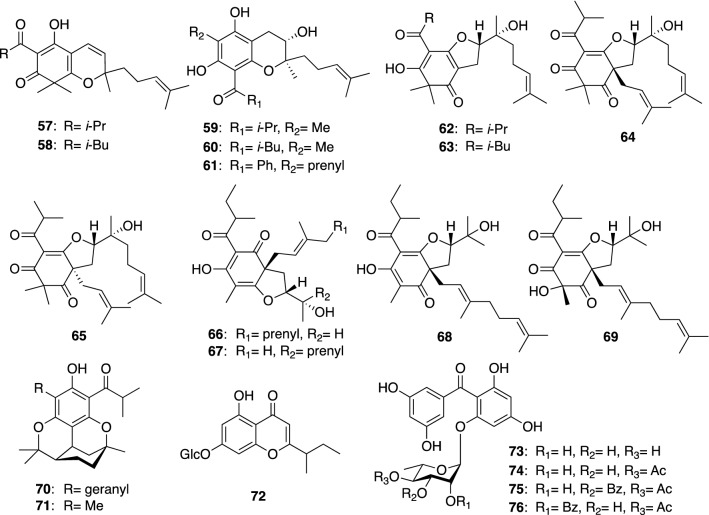

Hypericum kiusianum (syn. H. pseudopetiolatum var. kiusianum) (Nagasaki-otogiri in Japanese) is a perennial herb distributed mainly in Kyushu and Shikoku islands, Japan, while a small perennial herb H. yojiroanum (Daisetsuhina-otogiri in Japanese) grows in Hokkaido, Japan. From the aerial parts of H. kiusianum collected at Kochi prefecture and the purchased whole plants of H. yojiroanum, we isolated a series of simple bicyclic PAPs named petiolins A–C (57, 58, and 62), J (59), L (64), and M (65) and yojironins C (63), D (60), E (66), F (67), G (68), H (69), and I (61) (Fig. 8) [44–47]. Petiolins A–C (57, 58, and 62) showed a moderate cytotoxicity against human epidermoid carcinoma KB cells [44]. Petiolin C (62) also exhibited a weak antifungal activity against Trichophyton mentagrophytes, whereas petiolin J (59) showed antimicrobial activities against Micrococcus luteus, Cryptococcus neoformans, and T. mentagrophytes [45]. Petiolins D (70) and K (71) are racemic tetracyclic PAPs with the citran skeleton isolated from H. kiusianum, whose structures were elucidated by X-ray crystallographic analyses [45, 48]. In addition to the PAPs mentioned above, a chromone glucoside, petiolin E (72), and benzophenone rhamnosides, petiolins F–I (73–76), were isolated from H. kiusianum [48, 49]. Recently, Wang et al. isolated petiolin G (74) from another Hypericum plant (H. wightianum) and reported its neuroprotective effect against corticosterone-induced PC12 cell injury [50]. Yojironins A (77) and B (78), isolated from H. yojiroanum, are biogenetically unique meroterpenes (Fig. 9) [46], being composed of only two acetate units with a 2-methylbutanoyl group and three isoprene units. Yojironin A (77) exhibited potent antimicrobial activities against Aspergillus niger (IC50 8 μg/mL), Candida albicans (IC50 2 μg/mL), Cryptococcus neoformans (IC50 4 μg/mL), T. mentagrophytes (IC50 2 μg/mL), S. aureus (MIC 8 μg/mL), and Bacillus subtilis (MIC 4 μg/mL) as well as antiproliferative activities against KB cells and murine lymphoma L1210 cells in vitro [46].

Fig. 8.

The structures of petiolins A–C (57, 58, and 62), D (70), E (72), F–I (73–76), J (59), L (64), and M (65) isolated from Hypericum kiusianum and yojironins C (63), D (60), E–H (66–69), and I (61) isolated from H. yojiroanum

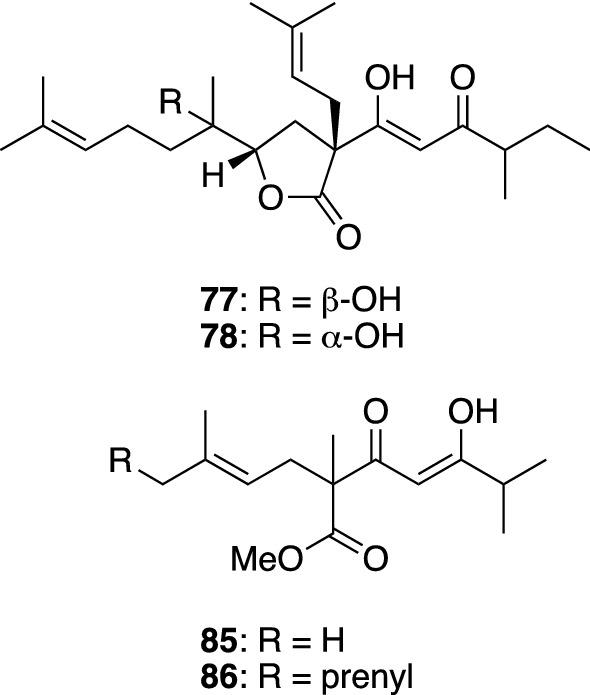

Fig. 9.

The structures of yojironins A (77) and B (78) isolated from Hypericum yojiroanum and yezo’otogirins G (85) and H (86) isolated from H. yezoense

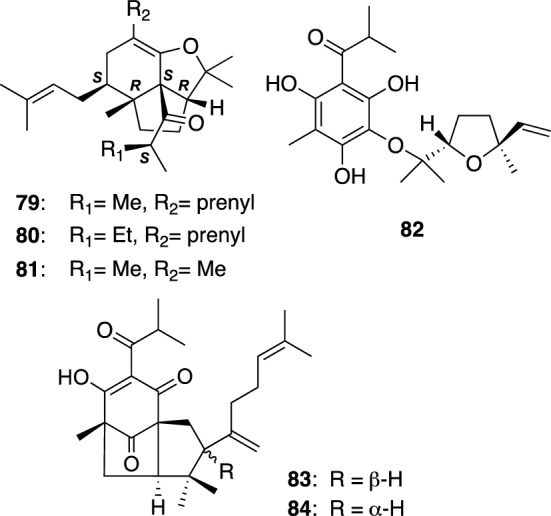

Hypericum yezoense (Yezo-otogiri in Japanese) is a perennial herb grown in the northern area of Japan. The investigation on constituents of the aerial parts of H. yezoense collected in Hokkaido gave three PAP-related meroterpenes possessing an unusual fused 6/5/5 tricyclic core, yezo’otogirins A–C (79–81) (Fig. 10) [51]. We assigned the absolute configurations of 79–81 by interpretation of ECD spectra aided with conformational analysis. George et al. achieved the biomimetic total synthesis of (±)-yezo’otogirin A [52]. Furthermore, the total synthesis and a moderate cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines of (±)-yezo’otogirin C were reported by He and Lee et al. [53, 54]. Yezo’otogirins D–H (82–86) were isolated from the aerial parts of H. yezoense cultivated at Hokkaido [55]. Yezo’otogirins G (85) and H (86) are simple linear meroterpenes with an enolized β-diketone moiety possessing a weak antimicrobial activity against B. subtilis and T. mentagrophytes, and are structurally related to yojironins A (77) and B (78) (Fig. 9). Yezo’otogirin D (82) is an acylphloroglucinol with a monoterpene moiety linked through an ether bond, while yezo’otogirins E (83) and F (84) are PAPs possessing a bicyclo[3.2.1]-octane-2,4,8-trione core (Fig. 10). Yezo’otogirin E (83) exhibited antimicrobial activites against Escherichia coli (MIC 4.0 μg/mL) and S. aureus (MIC 8.0 μg/mL) [55].

Fig. 10.

The structures of yezo’otogirins A–F (79–84) isolated from Hypericum yezoense

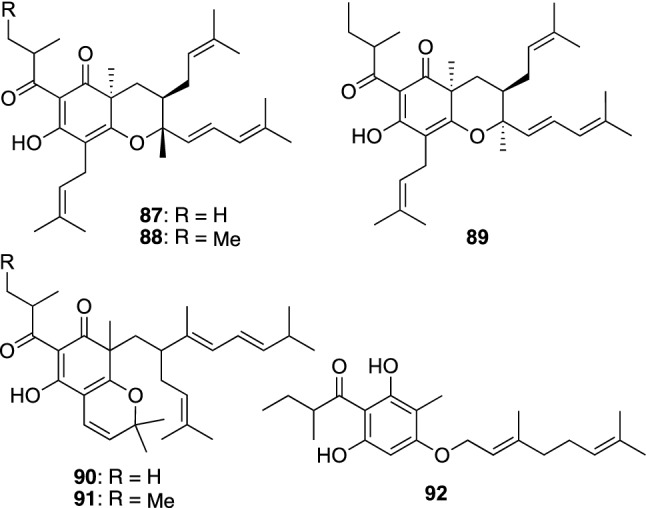

Hypericum erecturm is a perennial herb widely distributed in east Asia. This plant is called “Otogirisou” in Japanese and a representative species of Hypericum plants seen in Japan. The aerial parts of H. erectum have been used as a traditional remedy to heal wounds, burn wounds, bruises, swelling, and rheumatism. Interestingly, the aerial parts of H. erectum were also used for treating disorders of birds. We, however, had an interest in the root constituents of H. erectum, and investigated them to isolated PAPs named erecricins A–E (87–91) and adotogirin (92) (Fig. 11) [56]. Erecricins A–E (87–91) are PAPs possessing a chromane or a chromene skeleton. Adotogirin (92), a simple acylphloroglucinol with an O-geranyl moiety, displayed antimicrobial activities against MRSA {MIC range 0.5–4.0 μg/mL for seven strains (MIC50 1.0 μg/mL)}, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (MICs 1.0 μg/mL for five strains), and B. subtilis (MIC 2.0 μg/mL), while 87–91 did not show any antimicrobial activities [56].

Fig. 11.

The structures of erecricins A–E (87–91) and adotogirin (92) isolated from Hypericum erectum

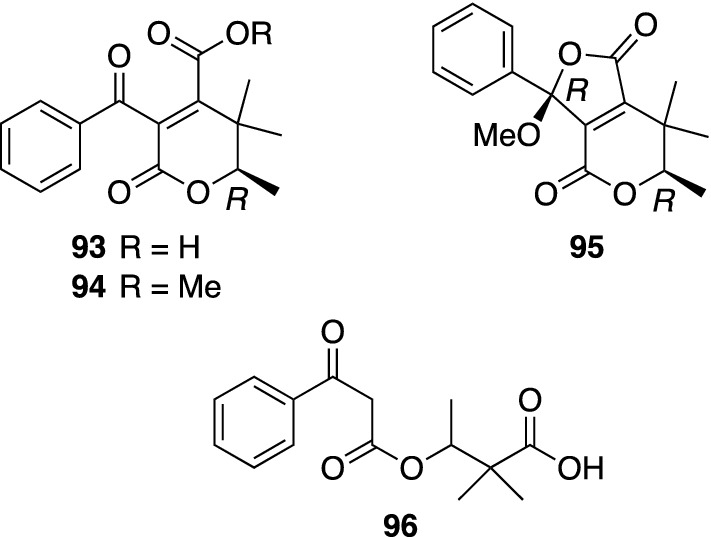

Ketides from Hypericum frondosum ‘Sunburst’ (section Myriandra)

Some woody Hypericum plants are cultivated as ornamental plants because of their beautiful yellow flowers that bloom in early summer. H. frondosum ‘Sunburst’ is a cultivar with larger flowers, and the investigation on the aerial parts of this plant cultivated at the botanical garden of Tokushima University gave four new ketides, frondhyperins A–D (93–96) (Fig. 12) [57]. Frondhyperins A–D (93–96) had novel chemical structures comprising short ketide and phenylketide moieties in common. The absolute configuration of 94 was assigned by ECD calculation, while those of 93 and 95 were revealed by their chemical correlation of 94. Frondhyperin D (96) was shown to be a racemate. It is noteworthy that PAPs, common constituents of Hypericum plants, were not found in this plant material in our study, although frondhyperin B (94) was isolated as a major constituent (325 mg from 870 g of dried aerial parts) [57].

Fig. 12.

The structures of frondhyperins A–D (93–96) isolated from Hypericum frondosum ‘Sunburst’

PAPs from Hypericum elodeoides (section Elodeoida) and H. scabrum (section Hirtella)

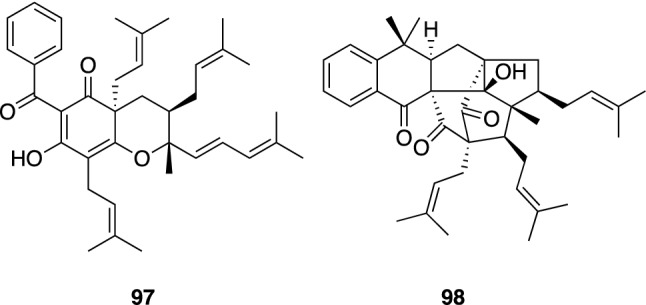

Hypericum elodeoides and H. scabrum are medicinally used perennial herbs grown in central to west regions of China and in central Asia, respectively. H. elodeoides has been used for the treatment of diarrhea and snake bite in China. Chromatographic separations of the extract from the aerial parts of H. elodeoides collected in Yunnan province, China furnished two PAPs, hypelodins A (97) and B (98) (Fig. 13) [58]. Hypelodin A (97) is a bicyclic PAP with three prenyl groups and one 4-methyl-1,3-pentadiene moiety, while hypelodin B (98) has a cage-like structure with a 6/6/5/7/6/5 hexacyclic ring system. Recently, Park et al. isolated hyperlodin B (98) from H. ascyron and reported its inhibitory activity against human neutrophil elastase [59].

Fig. 13.

The structures of hypelodins A (97) and B (98) isolated from Hypericum elodeoides

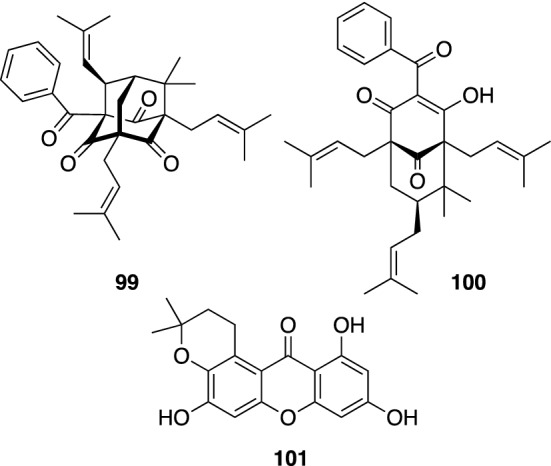

H. scabrum is one of the most popular medicinal herbs in Uzbekistan to treat numerous disorders, such as liver, gall bladder, intestinal, and heart diseases, rheumatism, and cystitis. Investigation on constituents of the aerial parts of H. scabrum collected at Chimgan, Uzbekistan showed this plant to be a rich source of polycyclic PAPs with a benzoyl group as their acyl moieties. Hyperibone K (99) is the first example of type B PAP possessing a “diamond-like” adamantane skeleton (Fig. 14) [60], whereas a number of type A adamantane or homoadamantane polycyclic PAPs have been reported to date [4, 5]. The absolute configuration of hyperibone K (99) was assigned based on the enantioselective total synthesis of an enantiomer of 99 by Porco, Jr. et al. [61]. Hyperibone L (100) is a polycyclic PAP with bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-2,4,9-trione core (Fig. 14) [60]. The synthesis of hyperibone L (100) was also achieved by Plietker et al. [62]. We reported a moderate cytotoxicity of hyperibones K (99) and L (100) against human cancer cell lines (A549 and MCF-7) [60], while a neuroprotective effect on the glutamate-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells and a hepatoprotective activity against paracetamol-induced HepG2 cell damage of 99 were reported by Gu et al. [63]. We also isolated prenylated xanthones, hyperxanthones A–F [60], from the same plant material. An inhibitory effect of hyperxanthone E (101) (Fig. 14) on interferon-γ plus LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 cells was reported by Xu et al. [64].

Fig. 14.

The structures of hyperibones K (99) and L (100) and hyperxanthone E (101) isolated from Hypericum scabrum

PAPs from Triadenum japonicum

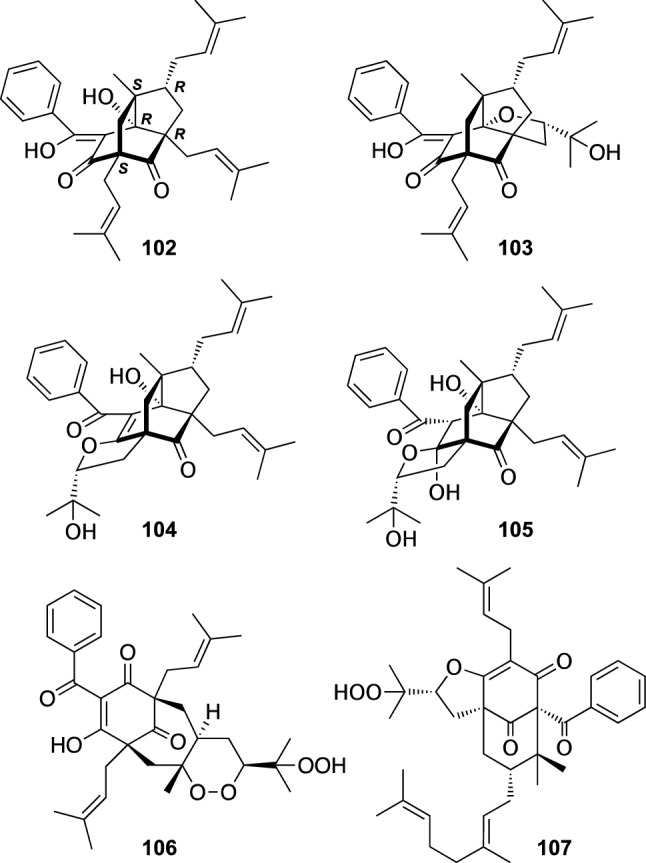

Triadenum is a sister genus of Hypericum consisting of six species. T. japonicum, a perennial herb bearing small pale pink flowers in contrast with yellow flowers of Hypericum plants, grows in marshy places in the eastern Asia and coastal area of eastern Russia. Our phytochemical investigation on the aerial parts of T. japonicum collected at Hokkaido resulted in the isolation of six new PAPs, (−)-nemorosonol (102) and trijapins A–E (103–107) [65]. The structure including the absolute configuration of 102 was assigned by NMR analysis and TDDFT ECD calculation. Interestingly, 102 was an enantiomer of (+)-nemorosonol previously isolated from Clusia nemorosa (Clusiaceae) [66]. Trijapins A–C (103–105) were assigned as analogues of (−)-nemorosonol (102) with an additional tetrahydrofuran ring, whereas trijapin D (100) was shown to be a PAP with an endperoxy moiety. (−)-Nemorosonol (102) exhibited antimicrobial activities against A. niger (IC50 16 μg/mL), T. mentagrophytes (IC50 8 μg/mL), C. albicans (IC50 32 μg/mL), E. coli (MIC 8 μg/mL), S. aureus (MIC 16 μg/mL), B. subtilis (MIC 16 μg/mL), and M. luteus (MIC 32 μg/mL), while trijapin D (106) showed an antimicrobial activity against C. albicans (IC50 8 μg/mL) [65] (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15.

The structures of (−)-nemorosonol (102) and trijapins A–E (103–107) isolated from Triadenum japonicum

Conclusion

This review summarized the chemical structures of 107 characteristic metabolites isolated from 11 Hypericum plants and one Triadenum plant by our research. Their structures were elucidated mainly on the basis of NMR, MS, X-ray, and ECD analyses including a TDDFT ECD calculation method, which has been widely applied to assignment of the absolute configuration of natural products in recent years [67]. Interesting biological activities of the characteristic metabolites, such as antiviral activities against HIV and HCV, antiproliferative activities against cancer cell lines including MDR cancer cell lines, and antimicrobial activities against various bacteria and fungus were also demonstrated. Our phytochemical studies suggested that Hypericum plants are a rich source of not only well-known PAPs and xanthones but also meroterpenes. Biyoulactones A–E (24–28) isolated from H. monogynum, hypatulins A (44) and B (45) isolated from H. patulum, and yezo’otogirins A–C (79–81) isolated from H. yezoense were meroterpenes structurally and biosynthetically related to PAPs, while plausible biosynthetic pathway of the PAPs was summarized in previous reviews [4, 5]. In contrast, some meroterpenes were conjugates with unprecedented structures composed of sesquiterpenes and a dibenzo-1,4-dioxane derivative {hyperdioxane A (18) isolated from H. ascyron} or a spirolactone derivative {biyouyanagins A (29) and B (30) isolated from H. monogynum}. Simple meroterpenes {yojironins A (77) and B (78) isolated from H. yojiroanum and yezo’otogirins D (85) and E (86) isolated from H. yezoense} and ketides {frondhyperins A–D (93–96) isolated from a cultivar H. frondosum ‘Sunburst’} were also biogenetically interesting compounds. Thus, Hypericum plants are an attractive source of various characteristic metabolites, and therefore a systematic biological evaluation of our compounds isolated from Hypericum plants is in progress.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nürk NM, Madriñán S, Carine MA, Chase MW, Blattner FR. Molecular phylogenetics and morphological evolution of St. Jon’s wort (Hypericum; Hypericaceae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;66:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao J, Liu W, Wang J-C. Recent advances regarding constituents and bioactivities of plants from the genus Hypericum. Chem Biodivers. 2015;12:309–349. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karioti A, Bilia AR. Hypericins as potential leads for new therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:562–594. doi: 10.3390/ijms11020562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X-W, Grossman RB, Xu G. Research progress of polycyclic polyprenylated acylophloroglucinols. Chem Rev. 2018;118:3508–3558. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciochina R, Grossman RB. Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3963–3986. doi: 10.1021/cr0500582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh IP, Bharate SB. Phloroglucinol compounds of natural origin. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:558–591. doi: 10.1039/b600518g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka N, Kobayashi J. Prenylated acylphloroglucinols and meroterpenoids from Hypericum plants. Heterocycles. 2015;90:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richard J-A, Pouwer RH, Chen DY-K. The chemistry of the polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:4536–4561. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka N, Niwa K, Kajihara S, Tsuji D, Itoh K, Mamadalieva NZ, Kashiwada Y. C28 terpenoids from Lamiaceous plant Perovskia scrophulariifolia: their structures and anti-neuroinflammatory activity. Org Lett. 2020;22:7667–7670. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X-R, Tanaka N, Tsuji D, Lu F-L, Yan X-J, Itoh K, Li D-P, Kashiwada Y. Sarcaglabrin A, a conjugate of C15 and C10 terpenes from the aerial parts of Sarcandra glabra. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020;61:151916. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niwa K, Yi R, Tanaka N, Kitaguchi S, Tsuji D, Kim S-Y, Tsogtbaatar A, Bunddulam P, Kawazoe K, Kojoma M, Damdinjav D, Itoh K, Kashiwada Y. Linaburiosides A-D, acylated iridoid glucosides from Linaria buriatica. Phytochemistry. 2020;171:12247. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashida W, Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y, Sekiya M, Ikeshiro Y, Takaishi Y. Tomoeones A-H, cytotoxic phloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum ascyron. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2225–2230. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu H, Chen C, Liu J, Sun B, Wei G, Li Y, Zhang J, Yao G, Luo Z, Xue Y, Zhang Y. Hyperascyrones A-H, polyprenylated spirocyclic acylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum ascyron Linn. Phytochemistry. 2015;115:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niwa K, Tanaka N, Tatano Y, Yagi H, Kashiwada Y. Hypascyrins A-E, prenylated acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum ascyron. J Nat Prod. 2019;82:2754–2760. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashida W, Tanaka N, Takaishi Y. Prenylated xanthones from Hypericum ascyron. J Nat Med. 2007;61:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niwa K, Tanaka N, Kim S-Y, Kojoma M, Kashiwada Y. Hyperdioxane A, a conjugate of dibenzo-1,4-dioxane and sesquiterpene from Hypericum ascyron. Org Lett. 2018;20:5977–5980. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b02739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe S, Tanaka N, Kobayashi J. Prenylated acylphloroglucinols, chipericumins A-D, from Hypericum chinense. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:484–488. doi: 10.1021/np200741x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagai M, Tada M. Antimicrobial compounds, chinesin I and II from flowers of Hypericum chinense L. Chem Lett. 1987;16:1337–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka N, Abe S, Hasegawa K, Shiro M, Kobayashi J. Biyoulactones A-C, new pentacyclic meroterpenoids from Hypericum chinense. Org Lett. 2011;13:5488–5491. doi: 10.1021/ol2021548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka N, Abe S, Kobayashi J. Biyoulactones D and E, meroterpenoids from Hypericum chinense. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:1507–1510. doi: 10.1021/ol2021548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka N, Okasaka M, Ishimaru Y, Takaishi Y, Sato M, Okamoto M, Oshikawa T, Ahmed SU, Consentino LM, Lee K-H. Biyouyangin A, an anti-HIV agent from Hypericum chinense L. var. salicifolium. Org Lett. 2005;7:2997–2999. doi: 10.1021/ol050960w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y, Kim SY, Hashida W, Sekiya M, Ikeshiro Y, Takaishi Y. Acylphloroglucinol, biyouyangiol, biyouyanagin B, and related spiro-lactones from Hypericum chinense. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1447–1452. doi: 10.1021/np900109y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aramaki Y, Chiba K, Tada M. Spiro-lactones, hyperolactone A-D from Hypericum chinense. Phytochemistry. 1995;38:1419–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicolaou KC, Sarlah D, Shaw DM. Total synthesis and revised structure of biyouyanagin A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:4708–4711. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolaou KC, Wu TR, Sarlah D, Shaw DM, Rowcliffe E, Burton DR. Total synthesis, revised structure, and biological evaluation of biyouyanagin A and analogues thereof. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11114–11121. doi: 10.1021/ja802805c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicolaou KC, Sanchini S, Wu TR, Sarlah D. Total synthesis and structural revision of biyouyanagin B. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:7678–7682. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du C, Li L, Li Y, Xie Z. Construction of two vicinal quaternary carbons by asymmetric allylic alkylation: total synthesis of hyperolactone C and (–)-biyouyanagin A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:7853–7856. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolaou KC, Sanchini S, Sarlah D, Lu G, Wu TR, Nomura DK, Cravatt BF, Cubitt B, de la Torre JC, Hessell AJ, Burton DR. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a biyouyanagin compound library. PNAS. 2011;108:6715–6720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015258108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savva CG, Totokotsopoulos S, Nicolaou KC, Neophytou CM, Constantinou AI. Selective activation of TNFR1 and NF-κB inhibition by a novel biyouyanagin analogue promotes apoptosis in acute leukemia cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:279. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Du C, Hu C, Li Y, Xie Z. Biomimetic synthesis of hyperolactones. J Org Chem. 2011;76:4075–4081. doi: 10.1021/jo102511x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka N, Niwa K, Kashiwada Y. Merohyperins A-C, meroterpenes from the leaves of Hypericum chinense. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:3175–3178. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka N, Takaishi Y. Xanthones from Hypericum chinense. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2146–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka N, Takaishi Y. Xanthones from stems of Hypericum chinense. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:19–21. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y, Kim S-Y, Sekiya M, Ikeshiro Y, Takaishi Y. Xanthones from Hypericum chinense and their cytotoxicity evaluation. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1456–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka N, Mamemura T, Abe S, Imabayashi K, Kashiwada Y, Takaishi Y, Suzuki T, Takebe Y, Kubota T, Kobayashi J. Biyouxanthones A-D, prenylated xanthones from roots of Hypericum chinense. Heterocycles. 2010;80:613–621. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W-J, Li R-J, Quasie O, Yang M-H, Kong L-Y, Luo J. Polyprenylated tetraoxygenated xanthones from the roots of Hypericum monogynum and their neuroprotective activities. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:1971–1981. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka N, Yano Y, Tatano Y, Kashiwada Y. Hypatulins A and B, meroterpenes from Hypericum patulum. Org Lett. 2016;18:5360–5363. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka N, Niwa K, Yano Y, Kashiwada Y. Prenylated benzophenone derivatives from Hypericum patulum. J Nat Med. 2020;74:264–268. doi: 10.1007/s11418-019-01350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y, Sekiya M, Ikeshiro Y, Takaishi Y. Takaneons A-C, prenylated butylphloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum sikokumontanum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2799–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y, Nakano T, Shibata H, Higuchi T, Sekiya M, Ikeshiro Y, Takaishi Y. Chromone and chromanone glucosides from Hypericum sikokumontanum and their anti-Helicobacter pylori activities. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srikrishna A, Beeraiah B, Gowri V. Enantiospecific approach to the tricyclic core structure of tricycloillicinone, ialibinones, and takaneones via ring-closing metathesis reaction. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:2649–2654. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka Y, Honma D, Tamura M, Yanagida A, Zhao P, Shoji T, Tagashira M, Shibusawa Y, Kanda T. New chromane and acylphloroglucinol glycosides from the bracts of hops. Phytochemistry Lett. 2012;5:514–518. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato H, Li W, Koike M, Wang Y, Koike K. Phenolic glycosides from Agrimonia pilosa. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1925–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka N, Kubota T, Ishiyama H, Araki A, Kashiwada Y, Takaishi Y, Mikami Y, Kobayashi J. Petiolins A-C, phloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum pseudopetiolatum var. kiusianum. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:5619–5623. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka N, Otani M, Kashiwada Y, Takaishi Y, Shibazaki A, Gonoi T, Shiro M, Kobayashi J. Petiolins J-M, prenylated acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum pseudopetiolatum var. kiusianum. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4451–4455. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mamemura T, Tanaka N, Shibazaki A, Gonoi T, Kobayashi J. Yojironins A-D, meroterpenes and prenylated acylophloglucinols from Hypericum yojiroanum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:3575–3578. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka N, Mamemura T, Shibazaki A, Gonoi T, Kobayashi J. Yojironins E-I, prenylated acylphloglucinols from Hypericum yojiroanum. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5393–5937. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka N, Kubota T, Ishiyama H, Kashiwada Y, Takaishi Y, Ito J, Mikami Y, Shiro M, Kobayashi J. Petiolins D and E, phloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum pseudopetiolatum var. kiusianum. Heterocycles. 2009;79:917–924. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka N, Kubota T, Kashiwada Y, Takaishi Y, Kobayashi J. Petiolins F-I, benzophenone rhamnosides from Hypericum pseudopetiolatum var. kiusianum. Chem Pharm Bull. 2009;57:1171–1173. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang L, Wang Z-M, Wang Y, Li R-S, Wang F, Wang K. Phenolic constituents with neuroprotective activities from Hypericum wightianum. Phytochemistry. 2019;165:112049. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanaka N, Kakuguchi Y, Ishiyama H, Kubota T, Kobayashi J. Yezo’otogirins A-C, new tricyclic terpenoids from Hypericum yezoense. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:4747–4750. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam HC, Kuan KKW, George JH. Biomimetic total synthesis of (±)-yezo’otogirin A. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:2519–2522. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00186a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He S, Yang W, Zhu L, Du G, Lee C-S. Bioinspired total synthesis of (±)-yezo’otogirin C. Org Lett. 2014;16:496–499. doi: 10.1021/ol403374h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang W, Cao J, Zhang M, Lan R, Zhu L, Du G, He S, Lee C-S. Systemic study on the biogenic pathways of yezo’otogirins: total synthesis and antitumor activities of (±)-yezo’otogirin C and its structural analogues. J Org Chem. 2015;80:836–846. doi: 10.1021/jo502267g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka N, Tsuji E, Kashiwada Y, Kobayashi J. Yezo’otogirins D-H, acylphloroglucinols and meroterpenes from Hypericum yezoense. Chem Pharm Bull. 2016;64:991–995. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c16-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu S, Tanaka N, Tatano Y, Kashiwada Y. Erecricins A-E, prenylated acylphloroglucinols from the roots of Hypericum erectum. Fitoterapia. 2016;114:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niwa K, Tanaka N, Kashiwada Y. Frondhyperins A-D, short ketide–phenylketide conjugates from Hypericum frondosum cv. Sunburst Tetraheron Lett. 2017;58:1495–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashida C, Tanaka N, Kawazoe K, Murakami K, Sun HD, Takaishi Y, Kashiwada Y. Hypelodins A and B, polyprenylated benzophenones from Hypericum elodeoides. J Nat Med. 2014;68:737–742. doi: 10.1007/s11418-014-0853-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li ZP, Kim JY, Ban YJ, Park KH. Human neutrophil elastase (HNE) inhibitory polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols from the flowers of Hypericum ascyron. Bioorg Chem. 2019;90:103075. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka N, Takaishi Y, Shikishima Y, Nakanishi Y, Bastow K, Lee KH, Honda G, Ito M, Takeda Y, Kodzhimatov OK, Ashurmetov O. Prenylated benzophenones and xanthones from Hyepricum scabrum. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1870–1875. doi: 10.1021/np040024+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qi J, Beeler AB, Zhang Q, Porco JA., Jr Catalytic enantioselective alkylative dearomatization–annuation: total synthesis and absolute configuration assignment of hyperibone K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13642–13644. doi: 10.1021/ja1057828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biber N, Möws K, Plietker B. The total synthesis of hyperpapuanone, hyperibone L, epi-clusianone and oblongifolin A. Nat Chem. 2011;3:938–942. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao W, Hou W-Z, Zhao J, Xu F, Li L, Fang Xu, Sun H, Xing J-G, Peng Y, Wang X-L, Ji T-F, Gu Z-Y. Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinol congeners from Hypericum scabrum. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:1538–1547. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang H, Zhang D-D, Lao Y-Z, Fu W-W, Liang S, Yuan Q-H, Yang L, Xu H-X. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory prenylated benzoylphloroglucinols and xanthones from the twigs of Garcinia esculenta. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:1700–1707. doi: 10.1021/np5003498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oya A, Tanaka N, Kusama T, Kim SY, Hayashi S, Kojoma M, Hishida A, Kawahara N, Sakai K, Gonoi T, Kobayashi J. Prenylated benzophenones from Triadenum japonicum. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:258–264. doi: 10.1021/np500827h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cerrini S, Lamba D, Monache FD, Pinherio RM. Nemorosonol, a derivative of tricyclo-[4.3.1.03,7]-decane-7-hydroxy-2,9-dione from Clusia nemorosa. Pytochemistry. 1993;32:1023–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nugroho AE, Morita H. Computationally-assisted discovery and structure elucidation of natural products. J Nat Med. 2019;73:687–695. doi: 10.1007/s11418-019-01321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]