Abstract

Background:

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a diverse class of chemicals, are hypothesized mammary carcinogens. We examined plasma levels of 17 PCBs as individual congeners and as a mixture in association with breast cancer using a novel approach based on quantile g-computation.

Methods:

This study included 845 White and 562 Black women who participated in the population-based, case–control Carolina Breast Cancer Study Phase I. Cases (n=748) were women with a first diagnosis of histologically confirmed, invasive breast cancer residing in 24 counties in central and eastern North Carolina; controls (n=659) were women without breast cancer from the same counties. PCBs were measured in plasma samples obtained during the study interview. We estimated associations (covariate-adjusted odds ratios [ORs] and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) between individual PCB congeners and breast cancer using multivariable logistic regression. We assessed PCB mixtures using quantile g-computation and examined effect measure modification by race.

Results:

Comparing highest and lowest tertiles of PCBs resulted in ORs of 1.3 (95%CI=0.95–1.8) for congener 74, 1.4 (95%CI=1.0–1.9) for 99, 1.3 (95%CI=0.91–1.8) for 194, and 1.2 (95%CI=0.90–1.7) for 201. Among all women, we estimated a joint effect of the PCB mixture with an OR of 1.3 (95%CI=0.98–1.6) per tertile change. In race-stratified analyses, associations for tertiles of PCB mixtures were stronger among Black women (OR=1.5, 95%CI=1.0–2.3) than among White women (OR=1.1, 95%CI=0.81–1.6).

Conclusion:

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that exposure to PCB mixtures increase the risk of breast cancer, but studies of populations with different exposure profiles are needed.

Keywords: PCBs, breast cancer, mixture, weighted quantile sum, quantile g-computation

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States (US). In 2020, an estimated 276,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 48,000 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ will be diagnosed1 and more than 40,000 women will die from the disease.2 However, breast cancer incidence and mortality are not distributed equally among US women. Age-adjusted incidence rates today are greater among White women as compared to Black women, but mortality rates are higher among Black women as compared to White women.2 The racial disparities in breast cancer mortality are thought to be attributed to differences in tumor biology, genomics, and access to and quality of care.3 What remains less well understood is the role of the chemicals in the environment including the role of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on breast cancer risk and how this risk may differ between Black and White women.

PCBs are a class of 209 aromatic congeners manufactured and used in the US from 1929 until their ban in 1979.4 Technical PCB products were comprised of mixtures of congeners, which were used heavily as dielectric fluids in capacitors and transformers, among many other uses.5 Although restrictions on the production and use of PCBs globally has generally resulted in decreased human exposure in recent decades, there is continued low-level exposure from the consumption of animal-derived foods, which bioaccumulate PCBs due to their long biologic half-lives ranging between 5 and 15 years, and from environmental contamination due to their environmental perisistence.6 PCB exposures are also unequally distributed among US women. Superfund and toxic waste sites are more frequently found in neighborhoods of color7 resulting in the contamination of locally sourced foods and, consequently, higher PCB levels in Blacks, Latinos, and low-income individuals.8,9

In 2013, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) re-assessed the carcinogenicity of PCBs and determined there was sufficient evidence to classify PCBs as carcinogenic to humans based on epidemiologic and laboratory studies of PCBs and melanoma.10 With respect to breast cancer, IARC determined that the findings from available studies were inconsistent and thus provided only limited evidence. Indeed, a meta-analysis of observational studies of PCB exposure and breast cancer risk published in 2015 reported only a summary 9% increase in breast cancer risk in association with total PCB exposure among 16 case–control and nine nested case–control studies.11 However, in their meta-analysis of PCB congeners subgroups, group 2 (potentially antiestrogenic and immunotoxic, dioxin-like) and group 3 (phenobarbital, CYP1A and CYP2B inducers, biologically persistent)12 PCBs were associated with 23% and 25% increases, respectively, in breast cancer risk.11 In a congener-specific meta-analysis of 16 studies published in 2016, Leng and colleagues reported elevated summary breast cancer odds ratios for PCBs 187, 99, and 183 (ORs=1.18, 1.36, and 1.56, respectively).13 Results from these meta-analyses implicate specific PCBs or PCB groups in breast carcinogenesis, but it is important to acknowledge that women are exposed PCBs as mixtures, so additional epidemiologic evidence is needed that accounts for the high correlations and potential interactions between these chemicals.

In this study, we examined 17 PCB congeners in association with breast cancer among women who participated in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study Phase I (CBCS-I). In previous CBCS-I analyses, total PCBs were not associated with breast cancer incidence among all women or among White women, but were associated with a 74% increase in the odds of breast cancer among Black women.14 Given the marked differences in biological activity between PCB congeners, in this study we examined the impact of each PCB congener individually as well as the overall impact of the PCB mixture using recently developed analytical methods by Keil et al. (i.e., quantile g-computation15). We also used a traditional weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression approach for comparison purposes. Last, we examined racial differences in breast cancer incidence for both the congener-specific and the mixture analyses.

METHODS

Study Population

This study included a subsample of 1,407 Black and White women (748 cases and 659 controls) with available plasma PCB and lipid measurements, from the 1,730 women (889 cases and 841 controls) who participated in CBCS-I, a population-based case–control study of female breast cancer conducted in 24 counties in central and eastern North Carolina.14,16 Cases were women with a first diagnosis of histologically confirmed, invasive breast cancer diagnosed between May 1993 and December 1996 identified by the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry using rapid case ascertainment. Controls were women from the same 24 counties selected from lists provided by the North Carolina Division of Motor Vehicles for women younger than 65 years old, and from records of the US Health Care Financing Administration for women 65–74 years of age. Black women and younger women (age <50) were oversampled using a modification of randomized recruitment17 in which 100% Black women under the age of 50 years, 75% Black women aged 50 years or older, 67% non-Black women under the age of 50 years, and 20% non-Black women aged 50 years or older were recruited. Overall response proportions (number of completed interviews/number of eligible participants) were 74% for cases and 53% for controls, as previously described.18 Approximately 98% of participants who were interviewed provided a non-fasting 30 mL blood sample at the time of interview (an average of 4.1 months after diagnosis for cases), which was used to measure plasma levels of 35 PCB congeners, as described below.14

All procedures performed in the CBCS involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Laboratory Assessment

PCB levels were measured in plasma samples using gas chromatography (GC) with electron capture detection at the Research Triangle Institute (Research Triangle Park, NC).14 A detailed description of the laboratory analyses is provided in Millikan et al. 2000.14 In brief, 2.0 mL plasma samples were treated with 1.0 mL of methanol, spiked with a surrogate standard of PCB198, and extracted with three 2.5 mL portions of hexane:diethyl ether (1:1). The extract was fractionated using Florisil (R) open-column chromatography and eluted with 35 mL of hexane. The fraction was concentrated to 0.5 mL and spiked with octachloronaphthalene as an external quantitation standard. Individual compounds were identified based on chromatographic retention times relative to the internal standards and pattern recognition in the sample extract. Calibration solutions were prepared from certified standard solutions for each of the 35 congeners measured. Of these, 18 PCBs were detected in <70% of participants (eTable 1) and were not considered further. Four PCB pairs were quantitated and reported as the sum of their concentrations because they co-elute during GC analysis. Thus, we report on nine individual PCB congeners and four PCB congener pairs. PCB levels below the limit of detection (LOD, 0.0125 ng/mL) were imputed as LOD/√2.19 Plasma lipid profiles, which were used to adjust PCB levels using the adjustment method of Phillips et al.,19 were measured using automated enzymatic assays at the Core Laboratory for Clinical Studies at Washington University School of Medicine (St. Louis, MO), as previously reported.14

Statistical Analysis

Congener-specific Analysis

We categorized individual lipid-adjusted PCB levels into tertiles based on the distributions in the controls and used multivariable unconditional logistic regression to estimate covariate-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between each PCB congener and incident breast cancer. We used the glm() function [family=binomial] in R and incorporated offsets derived from the sampling probabilities used to identify eligible participants, and the following a priori selected covariates derived from the nurse-administered case–control interview questionnaire: age at diagnosis (continuous in years), age-squared, menopausal status (pre-menopausal vs. post-menopausal), BMI (<25.0, 25.0–29.9, vs. ≥30.0 kg/m2), parity and breastfeeding composite (parity 1–2, never breastfeed; parity 1–2, ever breastfed; parity 3+, never breastfed; parity 3+, ever breastfed; vs. nulliparous), hormone replacement therapy use (ever vs. never), and annual household income (<$15,000, $15,000 to <$30,000, $30,000 to <$50,000, vs. ≥$50,000). We examined race-stratified models for each PCB or PCB pair and evaluated the effect measure modification on the multiplicative scale by including interaction terms between each log-transformed PCB congener concentration and race (White, Black) in the fully-adjusted regression models. We also compared stratified analyses (by race) by using a Cochran Q test for heterogeneity.

Mixture Analysis

Quantile g-computation has been recently proposed to study the effects of complex chemical exposure mixtures as a robust alternative to traditional methods. G-computation is a generalization of standardization that computes estimates of the expected outcome distribution under specific exposure patterns.20 Quantile g-computation is a an extension of weighted quantile sum regression, which uses a quantized exposure index with empirical weights for each exposure derived from quantiles of the exposures.21 However, quantile g-computation has two main advantages over weighted quantile sum regression: 1) quantile g-computation does not require a directional homogeneity assumption, whereas weighted quantile sum regression assumes the individual exposures have covariate adjusted associations with the outcome that are in the same direction or null, and 2) quantile g-computation allows for non-linearity and non-additivity of the effects of individual exposures and the mixture as a whole, whereas weighted quantile sum regression assumes that the individual exposures have linear and additive effects. We first examined Spearman correlations between each of the lipid-adjusted PCB congeners. We then employed quantile g-computation (i.e., g-computation performed using quantized exposures) in conjunction with logistic regression [family=binomial()], which included offsets derived from the sampling probabilities used to identify eligible participants and the covariates described above using the R package qgComp15 (version 2.3.0) to examine the associations between the mixture of the 17 PCB congeners ranked manually in tertiles based on the exposure distribution of all controls and odds of incident breast cancer, overall and by race. For quantile g-computation, the estimated coefficient 𝜓 is interpretable as the log odds ratio of changing (by increasing or decreasing) all exposures by one tertile at the same time.

In sensitivity analyses, we compared our results derived from the quantile g-computation approach to those derived using generalized weighted quantile sum regression.21,22 We used logistic regression using the R package qWQS (version 2.0.1) to examine the associations between the covariate-adjusted mixture of the 17 PCB congeners and odds of incident breast cancer, overall and by race. In the weighted quantile sum regression, we used 40% of the data as a training set and 60% as a validation set, derived the weights from models where the beta values were positive, ranked the PCB variables in tertiles, and used 100 bootstrapped estimates. For weighted quantile sum regression, the estimated coefficient 𝜓 is interpretable as the log odds ratio of increasing all exposures by one tertile at the same time.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and used a completed-case approach.

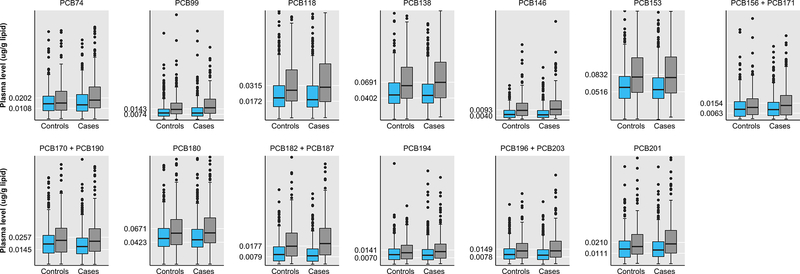

RESULTS

The characteristics of the women included in this study are presented in Table 1. The mean age of cases at diagnosis was 50.2 (SD=12.0) years, and 51% of women were pre-menopausal, 31% had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and 85% reported being parous. The mean age of controls at the time of identification was 51.5 (SD=11.7) years, and 46% were pre-menopausal, 34 had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and 90% reported being parous. As shown in Figure 1, Black women had higher median and more extreme PCB levels compared to White women. For example, median levels of PCB201 were higher among Black cases (0.0197, interquartile range (IQR)=0.0112–0.0320 μg/g lipid) than White cases (0.0141, IQR=0.00805–0.0217 μg/g lipid), and among Black controls (0.0173, IQR=0.0102–0.0285 μg/g lipid) than White controls (0.0150, IQR=0.00742–0.0223 μg/g lipid).

Table 1.

Characteristics of CBCS-I women with and without invasive breast cancer and with available plasma PCB and lipid data, by case–control status (n=1,407).

| Characteristic | Controls n (%)a | Cases n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||

| <50 | 350 (53) | 438 (59) |

| ≥50 | 309 (47) | 310 (41) |

| Race | ||

| White | 389 (59) | 456 (61) |

| Black | 270 (41) | 292 (39) |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Pre-menopausal | 306 (46) | 382 (51) |

| Post-menopausal | 353 (54) | 366 (49) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| <25.0 | 212 (33) | 284 (39) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 213 (33) | 221 (30) |

| ≥30.0 | 223 (34) | 229 (31) |

| Missing | 11 | 14 |

| Parity/breastfeeding history | ||

| Parity 1–2, never breastfeed | 219 (33) | 256 (34) |

| Parity 1–2, ever breastfed | 118 (18) | 125 (17) |

| Parity 3+, never breastfed | 117 (18) | 131 (18) |

| Parity 3+, ever breastfed | 140 (21) | 124 (17) |

| Nulliparous | 65 (10) | 112 (15) |

| Hormone replacement therapy use | ||

| Never | 466 (71) | 567 (76) |

| Ever | 193 (29) | 181 (24) |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$15,000 | 135 (23) | 169 (24) |

| $15,000 – <$30,000 | 127 (21) | 161 (23) |

| $30,000 – <$50,000 | 158 (26) | 169 (24) |

| ≥$50,000 | 179 (30) | 197 (28) |

| Missing | 60 | 52 |

Unweighted column percentages.

Figure 1.

Box plots of the distribution of lipid-adjusted polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners by case–control status and race (blue = White women, gray = Black women) in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study Phase I (n=1,407). Boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, lines inside the boxes are medians, whiskers represent values within the 1.5 IQR of the 25th and 75th percentiles, and circles represent outliers (N.B. extreme outliers not shown). Tick marks on the y-axes represent the tertile cutpoints for each PCB based on the exposure distribution of all controls.

Congener-Specific Analysis

The results of the congener-specific analyses between individual PCBs and breast cancer among all women overall and by race are reported in Table 2. Four PCBs (74, 99, 194, and 201) showed estimated ORs of 1.2 or higher for the highest vs lowest tertiles. The highest was PCB99 (OR=1.4; 95% CI=1.0–1.9). Continuous ln-transformed levels of these four PCB congeners and of PCBs 118 and 138 were associated with ORs of 1.2 per ln-unit increase. Associations between PCBs 74, 99, 180, 182 + 187, and 201 were more pronounced among Black women than among White women. For example, the highest (vs. lowest) tertile of PCB201 was associated with a breast cancer OR of 1.7 (95%CI=1.0–2.8) among Black women, and with a breast cancer OR of 1.1 (95%CI=0.69–1.6) among White women (Cochran Q=1.97; p=0.16). A one-ln-unit increase in PCB201 was associated with breast cancer ORs of 1.3 (95%CI=1.0–1.7) for Black women and 1.1 (95%CI=0.93–1.4) for White women.

Table 2.

Logistic regression odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between plasma levels of lipid-adjusted polychlorinated biphenyls and odds of incident breast cancer in CBCS-I (n=1,407).

| Overall |

White |

Black |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCBs (μ/g lipid) | Median in controls (μg/g lipid) | n cases / n controls | OR (95% CI)a | n cases / n controls | OR (95% CI)a | n cases / n controls | OR (95% CI)a | PInteractionb |

| PCB74 | 0.87 | |||||||

| ≤0.0108 | 0.00631 | 242/220 | 1.0 | 172/134 | 1.0 | 70/86 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0109–0.0202 | 0.0153 | 235/220 | 1.1 (0.83–1.5) | 142/138 | 0.90 (0.63–1.3) | 93/82 | 1.6 (0.98–2.6) | |

| >0.0202 | 0.0290 | 271/219 | 1.3 (0.95–1.8) | 142/117 | 1.2 (0.80–1.8) | 129/102 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) | |

| Ln(PCB74) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.2 (0.95–1.4) | 1.3 (0.99–1.6) | |||||

| PCB99 | 0.90 | |||||||

| ≤0.00742 | 0.00472 | 245/217 | 1.0 | 190/158 | 1.0 | 55/59 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00743–0.0143 | 0.0106 | 217/217 | 1.1 (0.80–1.4) | 135/132 | 1.0 (0.71–1.4) | 82/85 | 1.2 (0.70–2.0) | |

| >0.0143 | 0.0226 | 279/216 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 126/93 | 1.4 (0.97–2.1) | 153/123 | 1.5 (0.89–2.6) | |

| Ln(PCB99) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.2 (0.97–1.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |||||

| PCB118 | 0.77 | |||||||

| ≤0.0172 | 0.0115 | 273/216 | 1.0 | 198/154 | 1.0 | 75/62 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0173–0.0315 | 0.0228 | 216/218 | 0.90 (0.68–1.2) | 139/132 | 0.96 (0.67–1.4) | 77/86 | 0.80 (0.48–1.3) | |

| >0.0315 | 0.0476 | 252/216 | 1.1 (0.79–1.5) | 114/97 | 1.2 (0.81–1.9) | 138/119 | 1.0 (0.59–1.7) | |

| Ln(PCB118) | 1.2 (0.99–1.4) | 1.2 (0.95–1.5) | 1.2 (0.93–1.6) | |||||

| PCB138 | 0.32 | |||||||

| ≤0.0402 | 0.0288 | 248/216 | 1.0 | 179/149 | 1.0 | 69/67 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0403–0.0691 | 0.0515 | 244/218 | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 171/142 | 1.2 (0.83–1.7) | 73/76 | 0.91 (0.54–1.5) | |

| >0.0691 | 0.0973 | 249/216 | 1.1 (0.78–1.5) | 101/92 | 1.0 (0.67–1.6) | 148/124 | 1.2 (0.70–2.0) | |

| Ln(PCB138) | 1.2 (0.99–1.4) | 1.2 (0.97–1.6) | 1.2 (0.87–1.6) | |||||

| PCB146 | 0.92 | |||||||

| ≤0.00401 | 0.00213 | 253/216 | 1.0 | 192/151 | 1.0 | 61/65 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00402–0.00925 | 0.00616 | 237/216 | 1.1 (0.82–1.5) | 160/143 | 1.1 (0.74–1.5) | 77/73 | 1.2 (0.71–2.1) | |

| >0.00925 | 0.0147 | 251/216 | 1.1 (0.80–1.6) | 99/86 | 1.1 (0.68–1.6) | 152/130 | 1.4 (0.80–2.3) | |

| Ln(PCB146) | 1.1 (0.96–1.3) | 1.1 (0.88–1.4) | 1.3 (0.97–1.6) | |||||

| PCB153 | 0.81 | |||||||

| ≤0.0516 | 0.0372 | 268/216 | 1.0 | 195/149 | 1.0 | 73/68 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0517–0.0832 | 0.0644 | 233/219 | 1.0 (0.75–1.3) | 158/147 | 0.93 (0.66–1.3) | 75/72 | 1.1 (0.67–1.9) | |

| >0.0832 | 0.116 | 240/215 | 0.96 (0.69–1.3) | 98/88 | 0.90 (0.59–1.4) | 142/127 | 1.2 (0.69–2.0) | |

| Ln(PCB153) | 1.0 (0.86–1.3) | 0.97 (0.76–1.3) | 1.3 (0.91–1.8) | |||||

| PCB156 + PCB171c | 0.34 | |||||||

| ≤0.00626 | 0.00230 | 245/220 | 1.0 | 158/136 | 1.0 | 87/84 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00627–0.0154 | 0.0104 | 257/220 | 1.1 (0.86–1.5) | 178/138 | 1.2 (0.84–1.7) | 79/82 | 1.1 (0.65–1.7) | |

| >0.0154 | 0.0234 | 246/219 | 1.1 (0.81–1.5) | 120/115 | 1.1 (0.72–1.7) | 126/104 | 1.3 (0.75–2.1) | |

| Ln(PCB156 + PCB171) | 1.1 (0.94–1.2) | 1.1 (0.93–1.3) | 1.1 (0.87–1.3) | |||||

| PCB170 + PCB190c | 0.92 | |||||||

| ≤0.0145 | 0.00838 | 246/210 | 1.0 | 165/131 | 1.0 | 81/79 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0146–0.0257 | 0.0208 | 253/211 | 1.2 (0.86–1.5) | 170/131 | 1.2 (0.81–1.7) | 83/80 | 1.2 (0.73–2.0) | |

| >0.0257 | 0.0356 | 222/210 | 0.87 (0.64–1.2) | 103/109 | 0.75 (0.50–1.1) | 119/101 | 1.1 (0.68–1.8) | |

| Ln(PCB170 + PCB190) | 0.91 (0.79–1.0) | 0.87 (0.73–1.0) | 0.98 (0.79–1.2) | |||||

| PCB180 | 0.30 | |||||||

| ≤0.0423 | 0.0314 | 260/216 | 1.0 | 187/140 | 1.0 | 73/76 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0424–0.0671 | 0.0531 | 237/216 | 1.0 (0.77–1.4) | 151/134 | 0.98 (0.68–1.4) | 86/82 | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | |

| >0.0671 | 0.0914 | 242/216 | 0.98 (0.72–1.3) | 112/107 | 0.85 (0.57–1.3) | 130/109 | 1.4 (0.84–2.4) | |

| Ln(PCB180) | 1.1 (0.86–1.3) | 0.92 (0.72–1.2) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | |||||

| PCB182 + PCB187b | 0.67 | |||||||

| ≤0.00787 | 0.00279 | 272/219 | 1.0 | 210/159 | 1.0 | 62/60 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00788–0.0177 | 0.0119 | 224/221 | 0.97 (0.73–1.3) | 157/145 | 0.95 (0.67–1.4) | 67/76 | 1.0 (0.58–1.8) | |

| >0.0177 | 0.0267 | 252/219 | 1.1 (0.78–1.6) | 89/85 | 1.0 (0.64–1.6) | 163/134 | 1.4 (0.82–2.5) | |

| Ln(PCB182 + PCB187) | 1.1 (0.95–1.3) | 1.1 (0.89–1.3) | 1.2 (0.94–1.5) | |||||

| PCB194 | 0.83 | |||||||

| ≤0.00700 | 0.00374 | 239/219 | 1.0 | 210/159 | 1.0 | 78/86 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00701–0.0141 | 0.0107 | 252/220 | 1.1 (0.84–1.5) | 157/145 | 1.0 (0.69–1.5) | 81/77 | 1.3 (0.81–2.2) | |

| >0.0141 | 0.0192 | 257/220 | 1.3 (0.91–1.8) | 89/85 | 1.1 (0.72–1.7) | 133/107 | 1.6 (0.96–2.7) | |

| Ln(PCB194) | 1.2 (0.97–1.4) | 1.1 (0.87–1.3) | 1.3 (0.99–1.7) | |||||

| PCB196 + PCB203c | 0.73 | |||||||

| ≤0.00780 | 0.00440 | 264/219 | 1.0 | 186/135 | 1.0 | 78/84 | 1.0 | |

| 0.00781–0.0149 | 0.0112 | 246/220 | 1.0 (0.75–1.4) | 162/151 | 0.80 (0.55–1.2) | 84/69 | 1.7 (0.97–2.8) | |

| >0.0149 | 0.0203 | 238/220 | 1.0 (0.73–1.5) | 108/103 | 1.0 (0.63–1.6) | 130/117 | 1.4 (0.79–2.4) | |

| Ln(PCB196 + PCB203) | 1.1 (0.89–1.3) | 1.0 (0.80–1.3) | 1.2 (0.89–1.6) | |||||

| PCB201 | 0.98 | |||||||

| ≤0.0111 | 0.00559 | 250/219 | 1.0 | 180/140 | 1.0 | 70/79 | 1.0 | |

| 0.0112–0.0210 | 0.0159 | 233/221 | 1.0 (0.75–1.3) | 151/137 | 0.90 (0.63–1.3) | 82/84 | 1.2 (0.71–1.9) | |

| >0.0210 | 0.02963 | 265/219 | 1.2 (0.90–1.7) | 125/112 | 1.1 (0.69–1.6) | 140/107 | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | |

| Ln(PCB201) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (0.93–1.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | |||||

Adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous in years), age-squared, race (Black vs. White), menopausal status (pre-menopausal vs. post-menopausal), BMI (<25.0, 25.0–29.9, vs. ≥30.0 kg/m2), parity and breastfeeding composite (parity 1–2, never breastfeed; parity 1–2, ever breastfed; parity 3+, never breastfed; parity 3+, ever breastfed; vs. nulliparous), hormone replacement therapy use (ever vs. never), and annual household income (<$15,000, $15,000 – <$30,000, $30,000 – <$50,000, vs. ≥$50,000), as appropriate.

P for multiplicative interaction from logistic regression models using continuous natural log-transformed lipid-standardized PCB levels and race.

These analytes are quantitated and reported as the sum of their concentrations because they co-elute during GC/MS analysis.

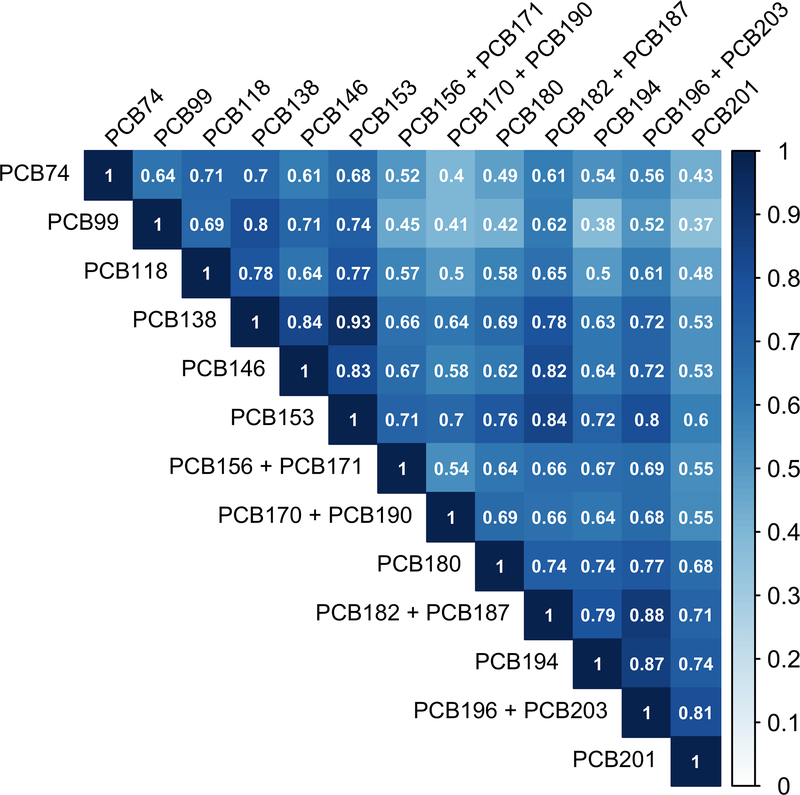

Mixtures Analysis

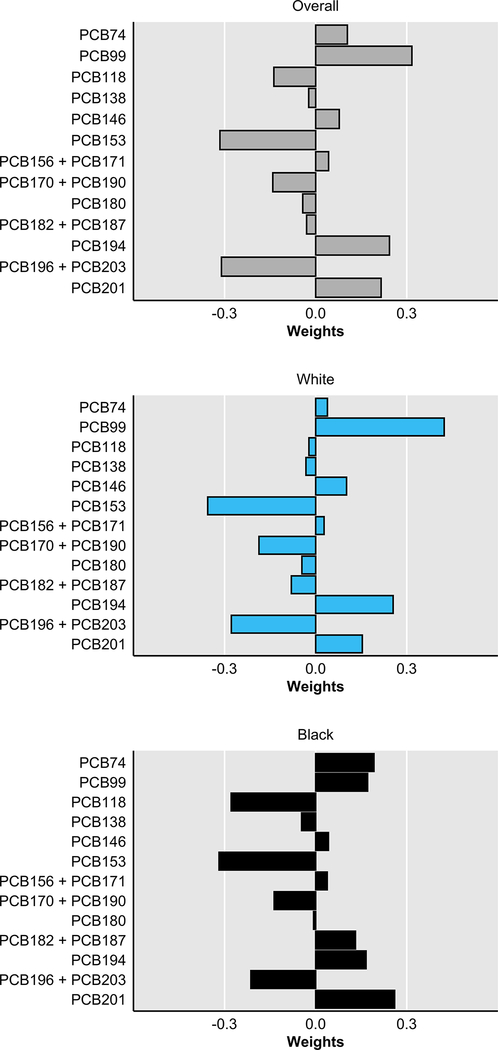

As shown in Figure 2, among CBCS-I controls, Spearman correlations between pairs of lipid-adjusted PCB congeners were positive and most correlations were high (ρ≥0.50). The lowest correlation observed was between PCBs 99 and 201 (ρ=0.37) and the highest correlation observed was between PCBs 138 and 153 (ρ=0.93). Due to the high dimensionality and high correlation structure, we employed a mixture analysis (i.e., quantile g-computation). The first step in quantile g-computation is the empirical estimation of the scaled weights corresponding to the proportion of the effect for each PCB congener. Quantile g-computation allows weights to be positive or negative and thus range between −1 and 1; positive weights sum to 1 and negative weights sum to −1. As shown in Figure 3, among all women, the PCBs with the highest positive weights included PCB99 (0.32), PCB194 (0.24), and PCB201 (0.22), while the PCBs with the highest negative weights included PCB153 (−0.32), PCB196 + PCB203 (−0.31), and PCB170 + PCB190 (−0.14). Among White women, the highest positive weights included PCB99 (0.42), PCB194 (0.26), and PCB201 (0.15) and among Black women, the highest positive weights included PCB201 (0.26), PCB74 (0.19), and PCB99 (0.17). PCB118 had a high negative weight among Black women (0.28), but not among White women (−0.02). In the quantile g-computation model with weighted tertiles of each exposure, changing all PCB congeners by one tertile at the same time was associated with a breast cancer OR of 1.3 (95%CI=0.98–1.6; 𝜓=0.233, SE=0.130) among all women overall, and with an OR of 1.1 (95%CI=0.81–1.6; 𝜓=0.135, SE=0.177) among White women and an OR of 1.5 (95%CI=1.0–2.3; 𝜓=0.422, SE=0.203) among Black women.

Figure 2.

Spearman correlations between plasma levels of lipid-adjusted polychlorinated biphenyls (μg/g lipid) among the Carolina Breast Cancer Study Phase I women without breast cancer (n=659).

Figure 3.

Quantile g-computation scaled weights corresponding to the proportion of the effect for each polychlorinated biphenyl congener in CBCS-I women (n=1,407), overall and by race. Negative weights indicate a reduced odds of incident breast cancer, whereas positive weights indicate increased odds of incident breast cancer.

In sensitivity analyses, we compared our results generated from the quantile g-computation mixture analysis to those generated using WQS regression. As WQS regression forces all weights to be constrained to sum to 1 and to range between 0 and 1, among all women the PCB congeners that had the largest weights included PCB99 (0.35), PCB201 (0.19), PCB182 + PCB187 (0.16), and PCB74 (0.15); the weights for the remaining PCBs were <0.05 (eFigure 1). Among White women, the three PCB congeners with the largest weights included PCB194 (0.28), PCB201 (0.25), and PCB99 (0.13). Among Black women, the three PCB congeners with the largest weights included PCB156 + PCB171 (0.35), PCB180 (0.16), and PCB201 (0.15). In the WQS logistic regression model with weighted tertiles of each exposure, increasing all PCB congeners by one tertile at the same time was associated with a breast cancer OR of 1.2 (95%CI=0.85–1.6; 𝜓=0.143, SE=0.157) among all women overall, and with an OR of 0.97 (95%CI=0.65–1.5; 𝜓=−0.028, SE=0.206) among White women and an OR of 1.5 (95%CI=0.95–2.4; 𝜓=0.399, SE=0.232) among Black women.

DISCUSSION

In this case–control study of breast cancer, we examined 17 PCBs as individual congeners and as a mixture. In the congener-specific analysis, we found that the highest tertiles of PCBs 74, 99, 194, and 201 were associated with increased odds of breast cancer compared to the lowest tertiles. It is important to note, however, that the congener-specific analyses do not control for the effects of the other PCB congeners, which were not included in the multivariable regression models given the high correlations between the PCB congeners, and thus a mixture analysis approach is important for understanding the effect of all PCBs simultaneously. In the mixture analysis, we estimated a joint effect of the PCBs with breast cancer, which among all women was more heavily weighted by these same four PCBs. When we stratified by race, some PCB associations were more pronounced among Black women than among White women for both the congener-specific analysis and the mixture analysis; however, we were not able to identify the presence of heterogeneous effects. Finally, when we compared the results from the quantile g-computation to those from the more traditional WQS regression analysis, we observed consistent patterns of association, though there were some differences. In the WQS regression, PCB182 +PCB187 was more heavily weighted in the mixture than PCB194, and associations were closer to the null and confidence intervals were wider.

Previous studies of individual PCB congeners or congener groupings have reported increased risk of breast cancer associated with higher levels of PCBs 99, 183, and 18713 and with PCBs categorized as group 2 or group 3 congeners.11 Our results reported here of an increase in odds of breast cancer among women with higher levels of PCB99 (a group 3 congener), and of mixtures more heavily weighted by PCB99 are consistent with prior studies. Interestingly, PCB99 (and PCB74) has also been shown to be associated with increased risk of 5-year breast cancer mortality among CBCS-I women with breast cancer.23 PCB183 was detected with too low a frequency to be investigated in the CBCS-I, but may nonetheless play an important role in the development of breast cancer among women with detectable levels.

To date, few studies have examined racial differences in PCB exposure in association with breast cancer risk. In a previous analysis in this same population, an analysis of total PCBs and breast cancer indicated that the highest tertile of the sum of the 35 measured PCBs was associated with a 74% increase in the odds of breast cancer among Black women, but not among White women.14 Those results were in agreement with a previous report by Krieger and colleagues in which the highest versus lowest tertile of total PCBs was associated with a 121% increase in the odds of breast cancer among Black women, and inversely associated with breast cancer in White women.24 However, results in both the CBCS and in Krieger et al. conflict with findings from the Women’s Contraceptive and Reproductive Experiences (CARE) Study conducted from 1995–1998, which reported no increase in breast cancer risk with increasing total PCB quintiles.25 The CARE Study, however, included fewer participants (355 cases and 327 controls) and did not examine individual PCBs. A limitation of using the total sum of measured PCBs, however, is that this approach assumes that PCBs have additive effects (whereas PCBs can vary in biologic activity) and thus the relative contributions of each PCB may not be appropriately weighted. If our findings are confirmed, future studies should aim to understand possible drivers of the racial disparities, such as lower rates of breast feeding26 or more aggressive tumors27 in Black women than in White women.25

Several mechanisms of carcinogenesis for PCBs have been proposed.10 First, PCB parent compounds and their metabolites are known endocrine disruptors and show estrogenic activity in vitro and in vivo.28–30 In estrogen-responsive tissues such as the mammary gland, PCBs may promote the proliferation of cells with existing mutations or increase the opportunity for novel mutations.31 Second, PCBs bind and activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), the human pregnane-X receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor,32 which may result in sustained upregulation or downregulation of a number of genes controlling cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell–cell communication and adhesion, and cell invasiveness.33 Third, PCBs induce the expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes,34 resulting in increased metabolism of PCBs and other environmental chemicals into highly reactive electrophilic species such as arene oxides and quinones, which can produce DNA adducts and reactive oxygen species.35 Additional laboratory evidence, however, is needed regarding the carcinogenic potential of PCB mixtures.

The strengths of our study include the biomarker measurement of PCBs and the inclusion of large numbers of Black women and women from the rural South. Additionally, for the first time, we examined both congener-specific and mixtures of PCBs in association with incident breast cancer. PCB levels are highly collinear with each other and with other persistent organic pollutants, which complicates their assessment in an analysis of PCB mixtures. To overcome many of the limitations of previous methods such as weighted quantile sum regression,21 we employed recently developed analytical methods by Keil et al. (i.e., quantile g-computation15). However, several limitations of our study should be noted. First, as with other case–control studies of PCBs and breast cancer, PCBs were measured shortly after diagnosis among women with breast cancer. Whether PCB levels at diagnosis reflect the etiologically relevant period for breast cancer is unknown. However, because PCBs are highly persistent and have long biologic half-lives measured in years,36 these levels may still be relevant in relation to breast cancer progression. Secondly, in this study, only 35 of 209 PCB congeners were measured, 18 of which were detected in <70% of participants. PCB exposure profiles are likely to vary across populations, and so our findings may not be generalizable to certain groups of women. Third, although we included large numbers of Black and White women, this study had limited power to examine interactions by race. Future studies should aim to include even larger numbers of Black and White women and women from other racial ethnic groups in their studies of PCBs and breast cancer.

Conclusions

In 2013, the Interagency Breast Cancer and Environmental Research Coordinating Committee (IBCERCC) published its report in which they made several recommendations for research on the effects of environmental chemicals hypothesized to be associated with breast cancer.37 One of the recommendations was to intensify the study of these chemicals, with an emphasis on research aimed at understanding how and when environmental exposures, singly and as mixtures, influence breast cancer risk. Herein, we help to fill this research gap by examining PCBs as individual congeners and as a mixture in association with breast cancer risk. Our results indicate increased risk associated with specific PCB congeners (PCBs 74, 99, 194, and 201) and suggest that some associations may be stronger in Black women than in White women. If confirmed, future studies should focus on elucidating the biologic mechanism(s) by which PCB mixtures increase breast cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Carolina Breast Cancer Study was funded by the University Cancer Research Fund of North Carolina, the National Cancer Institute Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (NIH/NCI P50-CA 58223), and Susan G. Komen for the Cure (Komen OGUNC1202). H Parada Jr was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K01 CA234317), the SDSU/UCSD Comprehensive Cancer Center Partnership (U54 CA132384 & U54 CA132379), and by the Alzheimer’s Disease Resource Center for Advancing Minority Aging Research at the University of California San Diego (P30AG059299).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards: All procedures performed in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and were in compliance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Ethical approval: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Obtaining data: The data and computer code for replicating these results would require a collaboration with the senior author, a formal data use agreement, and institutional review board approval from the participating institutions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Breast Cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Published 2020. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 3.Daly B, Olopade OI. A perfect storm: how tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(3):221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). https://www.epa.gov/pcbs/learn-about-polychlorinated-biphenyls-pcbs. Published 2020. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 5.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological Profile for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=142&tid=26. Published 2015. Accessed August 29, 2019. [PubMed]

- 6.Patandin S, Dagnelie PC, Mulder PGH, et al. Dietary exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins from infancy until adulthood: A comparison between breast-feeding, toddler, and long-term exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(1):45–51. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9910745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banzhaf S, Ma L, Timmins C. Environmental justice: The economics of race, place, and pollution. J Econ Perspect. 2019;33(1):185–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavuk M, Olson JR, Wattigney WA, et al. Predictors of serum polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations in Anniston residents. Sci Total Environ. 2014;496:624–634. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xue J, Liu SV., Zartarian VG, Geller AM, Schultz BD. Analysis of NHANES measured blood PCBs in the general US population and application of SHEDS model to identify key exposure factors. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24(6):615–621. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Grosse Y, et al. Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, Huang Y, Wang X, Lin K, Wu K. Environmental polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Lehmler H-J, ed. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negri E, Bosetti C, Fattore E, La Vecchia C. Environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and breast cancer: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:509–516. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000102559.94285.c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leng L, Li J, Luo X mei, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls and breast cancer: a congener-specific meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2016;88:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millikan R, DeVoto E, Duell EJ, et al. Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethene, polychlorinated biphenyls, and breast cancer among African-American and white women in North Carolina. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(11):1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keil AP, Buckley JP, O’Brien KM, Ferguson KK, Zhao S, White AJ. A quantile-based g-computation approach to addressing the effects of exposure mixtures. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128(4):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman B, Moorman PG, Millikan R, et al. The Carolina Breast Cancer Study: integrating population-based epidemiology and molecular biology. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35(1):51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Randomized recruitment in case–control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(4):421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moorman PG, Newman B, Millikan RC, Tse CK, Sandler DP. Participation rates in a case–control study: the impact of age, race, and race of interviewer. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(3):188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips DL, Pirkle JL, Burse VW, Bernert JT, Henderson LO, Needham LL. Chlorinated hydrocarbon levels in human serum: effects of fasting and feeding. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989;18(4):495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snowden JM, Rose S, Mortimer KM. Implementation of G-computation on a simulated data set: Demonstration of a causal inference technique. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):731–738. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrico C, Gennings C, Wheeler DC, Factor-Litvak P. Characterization of weighted quantile sum regression for highly correlated data in a risk analysis setting. J Agric Biol Environ Stat. 2015;20(1):100–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renzetti S, Gennings C, Curtin P. gWQS: An R package for linear and generalized weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression. J Stat Softw. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parada H, Sun X, Tse C, et al. Plasma levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and breast cancer mortality: The Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2020;227(March):113522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N, Wolff MS, Hiatt RA, Rivera M, Vogelman J, Orentreich N. Breast cancer and serum organochlorines: a prospective study among white, black, and Asian women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86(8):589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gatto NM, Longnecker MP, Press MF, Sullivan-Halley J, McKean-Cowdin R, Bernstein L. Serum organochlorines and breast cancer: A case–control study among African-American women. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(1):29–39. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0070-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein L, Teal CR, Joslyn S, Wilson J. Ethnicity-related variation in breast cancer risk factors. Cancer. 2003;97(S1):222–229. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gierthy JF, Arcaro KF, Floyd M. Assessment of PCB estrogenicity in a human breast cancer cell line. Chemosphere. 1997;34(5–7):1495–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(97)00446-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arcaro KF, Yi L, Seegal RF, et al. 2,2’,6,6’-tetrachlorobiphenyl is estrogenic in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Biochem. 1999;(72):94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hany J, Lilienthal H, Sarasin A, et al. Developmental exposure of rats to a reconstituted PCB mixture or aroclor 1254: Effects on organ weights, aromatase activity, sex hormone levels, and sweet preference behavior. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;158(3):231–243. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pike MC, Spicer D V, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Salman F, Plant N. Non-coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are direct agonists for the human pregnane-X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor, and activate target gene expression in a tissue-specific manner. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;263(1):7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauby-secretan B, Loomis D, Baan R, et al. Use of mechanistic data in the IARC evaluations of the carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and related compounds. Env Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:2220–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spink BC, Pang S, Pentecost BT, Spink DC. Induction of cytochrome P450 1B1 in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells by non-ortho-substituted polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicol Vitr. 2002;16(6):695–704. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2333(02)00091-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penning TM. Genotoxicity of ortho-quinones: reactive oxygen species versus covalent modification. Toxicol Res (Camb). 2017;6(6):740–754. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00223h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritter R, Scheringer M, MacLeod M, Moeckel C, Jones KC, Hungerbühler K. Intrinsic human elimination half-lives of polychlorinated biphenyls derived from the temporal evolution of cross-sectional biomonitoring data from the United Kingdom. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(2):225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Interagency Breast Cancer and Environmental Research Coordinating Committee (IBCERCC). Breast Cancer and the Environment. Prioritizing Prevention. Research Triangle Park, NC; 2013. http://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/assets/docs/ibcercc_full_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.