Abstract

Background:

Recovery homes for persons with alcohol and drug problems provide an abstinent living environment and social support for recovery. Research shows residents in these homes make significant, sustained improvements. However, descriptions of recovery environments within the homes have been limited.

Purpose:

The current study assessed psychometric properties for the Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES), which assessed social environments within one type of recovery home, sober living houses (SLHs).

Methods:

373 residents were interviewed at entry into the house, 1-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up. Measures included the RHES, other measures of the social environment, days of substance use, and length of stay.

Results:

Principal components analysis suggested the RHES was largely unidimensional. Exploratory factor analysis suggested items could be grouped into recovery support (3 items) and recovery skills (5 items). Cronbach’s alphas for the full scale and the recovery support and recovery skills subscales were 0.91, 0.89, and 0.87, respectively. As hypothesized, construct validity of the RHES was supported by correlations with other measures of the social environment and predictive validity was supported by associations with length of stay and substance use.

Conclusions:

SLHs have been described as “the setting is the service.” However, the field has lacked a way to capture characteristics of the social environment. The RHES represents a new way to measure the recovery environment by focusing on social interactions among residents within SLHs and shared activities in the community.

Keywords: recovery home, social model, sober living house, factor analysis, social support

Recovery homes are alcohol- and drug-free living environments for persons attempting to abstain from using substances and there is a growing body of evidence showing favorable outcomes (Reif, et al, 2014). Recovery homes serve persons who need a supportive living environment after they complete residential treatment, while they attend outpatient treatment, after they leave incarceration, or those currently seeking recovery services outside the realm of professional treatment. Although some homeless persons with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders require a more structured living environment than that offered in many recovery residences, others who are relatively stable and present with higher levels of interpersonal strengths can be well-served in these settings (Polcin, 2016). In addition, some recovery residences have made modifications to be more responsive to the needs of persons with co-occurring disorders (Polcin & Korcha, 2015).

This study reports on one type of recovery home, sober living houses (SLHs), which are typically operated by persons in recovery. SLHs originated in California during the late 1940’s (Wittman & Polcin, 2014). At that time, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was expanding, particularly in urban areas such as Los Angeles. Some persons attending AA needed stable housing that supported recovery. AA members who had achieved abstinence and had sufficient resources provided temporary shelter to some of these individuals. Over time, rooms were rented out to these individuals and eventually entire houses were rented to groups of persons seeking an affordable living environment that supported recovery. These residences eventually became known as sober living houses and they expanded rapidly over subsequent decades.

SLHs do not provide counseling, case management, treatment planning, or a structure of daily activities. Instead, they use a “social model” approach to recovery that emphasizes peer support and peer involvement in how the houses are operated (Wittman & Polcin, 2014). Also consistent with social model recovery is an emphasis on 12-step recovery. Most houses require or strongly recommend involvement in 12-step recovery groups. Typically, a house manager oversees operation of the house, including payment of rent and bills, admissions, evictions, consequences for rule violations, and facilitation of house meetings (Polcin, Mahoney & Mericle, 2020). However, managers of well-run SLHs encourage resident involvement and input into all of these issues (Polcin, Mericle, Howell, Sheridan, & Christensen, 2014). The social model approach results in a shared sense of responsibility for house operations and an understanding of how rules and regulations promote efficient functioning of the household and a social environment that supports recovery.

Because SLHs are not licensed or required to report their existence to any agency or local government, it is difficult to ascertain their exact numbers. However, in California, Sober Living House Associations such as the Sober Living Network (SLN) and California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals (CCAPP) report a combined membership of nearly 800 houses in the state (Wittman & Polcin, 2014). The National Alliance of Recovery Residences (NARR), which includes a broad range of different types of recovery homes in the U.S., reports a membership of 25,000 persons who are living in over 2,500 certified recovery residences (National Association of Recovery Residences, 2012). Another type of recovery home, Oxford Houses (O’Neill, 1990), is popular outside California, with over 1,200 homes nationwide. It should be noted that since the onset of COVID-19, many recovery homes have struggled to remain open. Some have closed as a result of COVID and most have modified their practices to comply with mitigation procedures (Polcin, et al., 2020).

Studies have shown that residents of different types of recovery homes make significant improvements in multiple areas of functioning, including alcohol and drug use, arrests, and employment (Reif, et al., 2014). Studies show improvements are made by individuals with diverse demographic, criminal justice, and problem severity characteristics (National Association of Recovery Residences, 2012). However, some residents fare better than others. A study of SLHs showed residents who reported having fewer drug and alcohol users in their social networks and more involvement in 12-step groups had better alcohol and drug outcomes (Polcin, Korcha, Bond, & Galloway, 2010). A study of a similar type of recovery home, Oxford Houses, showed general social support from friends and family was associated with better outcome (Groh, Jason, Davis, Olson, & Ferrari, 2007). In a more recent study of SLHs, Witbrodt, Polcin, Korcha & Li (2019) found residents who entered SLHs with higher levels of recovery capital had better outcomes and more readily able to benefit from a motivational interviewing case management intervention.

Papers addressing the characteristics of the recovery houses have mostly been descriptions of specific issues, such as house rules (Ferrari, et al., 2004), physical design of facilities (Ferrari, Jason, Sasser, et al., 2006), and neighborhood factors (Ferrari, Jason, Blake, et al., 2006). Social environment aspects of the have been studied minimally and primarily limited to descriptions of Oxford Houses. These studies have focused on broad aspects of the social environment, rather than environmental characteristics specific to recovery. For example, Harvey and Jason (2011), examined generic social environment factors in Oxford Houses using the Community Oriented Evaluation Scale (COPES) (Moos, 1988). The investigators reported that, compared to residents of Oxford Houses, residents of one therapeutic community program experienced lower scores on Support and Involvement subscales. Other studies of Oxford Houses elicited individual self-reports about generic social behaviors, such as willingness to loan money, friendship, and advice-giving among residents (Jason et al., 2020). Viola, Davis, and Jason (2009) assessed helping in Oxford Houses. They found Oxford House residents who were 12-step sponsors and women were involved in more helping behaviors than other residents.

These measures represent efforts to understand some social dynamics within Oxford Houses. However, whether they are appropriate for other types of recovery homes (e.g., SLHs) remains to be determined. In addition, these measures miss assessments of important recovery-specific issues. For example, existing measures are limited in terms of assessing the extent to which houses integrate social model recovery principles into their operations. One paper addressing this limitation was published by Kaskutas et al (1998), who described a scale to assess social model characteristics in a variety of substance abuse service settings.

The Social Model Philosophy Scale (SMPS) (Kaskutas, Greenfield, Borkman, & Room, 1998) was designed to describe the physical characteristics, recovery philosophy, and operational structures of substance abuse programs. The scale measures the extent to which programs adhere to social model philosophy using six subscales: physical environment, staff role, authority base, view of dealing with substance abuse problems, governance, and community orientation. Scores that are higher on these scales reflect social model characteristics such as a homelike environment, egalitarian roles between staff and clients, client involvement in decision making, and an emphasis on 12-step recovery principles.

One goal of the SMPS is to provide an overall cutoff score that depicts whether a program meets criteria to be described as social model. However, Mericle and colleagues (Mericle, Miles, Cacciola, & Howell, 2014) studied recovery homes in Philadelphia and found there was wide variation of subscale scores. For example, most directors or managers rated their homes high on recovery philosophy but low on peer governance.

There are several limitations to the SMPS. First. using the SMPS, data are generated by interviewing program directors or managers who oversee delivery of services. Missing in these assessments are the perceptions and experiences of the persons receiving services. Second, data from the SMPS primarily reflect how programs are designed and structured, not what actually occurs in terms of social model activities and behaviors among persons in the program. Finally, the scale was designed to measure a wide variety of treatment and recovery homes. There is a need for assessments that specifically target recovery homes.

The main goal of the current study was to examine the extent to which social model activities and behaviors were prevalent from the perspectives of individuals residing in sober living recovery homes. There is a need for information about the extent to which SLHs create environments where different aspects of social model recovery are practiced and how the extent of social model practices relate to outcome. For example, although recovery homes generally encourage residents to practice the 12-steps to manage daily stresses, current measures do not assess the extent to which this occurs as an ordinary aspect of household functioning. Other issues not assessed by current measures include the extent to which residents engage in social activities in the community and attendance at 12-step meetings together. These activities can play important roles in building interpersonal cohesion among residents, a key principle of social model recovery (Polcin et al., 2014). We posit these issues are vitally important to understanding recovery environments, yet they have been largely overlooked in research on recovery homes.

Purpose

The purpose of the current study was to develop a psychometrically sound measure of recovery environments within recovery homes that addressed the limitations of current measures. We aimed to achieve this goal by drawing on data from a large ongoing study of SLHs. Our goal was to examine the factor structure of a newly developed measure, the Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES), as well as the internal consistency of subscales, construct validity, and predictive validity. Because the RHES emphasized peer support and involvement of residents in recovery homes, we hypothesized that construct validity would be supported by positive correlations between the RHES scale(s) and the Involvement and Support subscales on the Community Oriented Evaluation Scale (COPES). We reasoned high levels of anger and aggressive interactions would be antithetical to the supportive aspects of the RHES, so we hypothesized a negative correlation between the RHES and the COPES Anger and Aggression subscale. We hypothesized that predictive validity of the RHES would be supported by significant positive associations with length of stay and negative associations with days of substance use at follow-up. We chose to collect data on recovery environments in sober living houses (SLHs) because the social model recovery approach is promoted as the primary beneficial influence (Polcin et al., 2014). It is therefore important to have a psychometrically sound measure to assess the strengths and weaknesses from a social model perspective and assess social model processes associated with outcome.

Methods

Development of Scale Items

Items for the Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES) were developed by the research team to assess issues that are central to social model recovery. For example, we wanted to assess the extent to which social model principles, such as peer support and 12-step recovery, guided house operations and interactions among residents. The initial content for scales items drew from qualitative interviews and focus groups with SLH managers (Polcin, Henderson, Trocki, Evans & Wittman, 2012; Polcin & Korcha, 2015). The initial draft consisted of eight items. As part of our preliminary work, we administered the items to 26 SLH managers and found acceptable levels of internal consistency (alpha=0.82). Based on feedback from these managers, minor adjustments were made in the wording of items. Table 2 indicates the wording of each of the eight items. The final version of the RHES contains 8 items measured in a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all; 2 = A Little; 3 = Somewhat; 4 = Quite a bit; 5 = A lot).

Table 2.

Item Scores and Varimax-rotated Factor Loadings of RHES Questions

| M | SD | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. To what extent do residents provide emotional support to one another? | 3.28 | 1.27 | 0.766 | 0.364 | 0.281 |

| 2. To what extent do residents socialize together? | 3.48 | 1.20 | 0.790 | 0.284 | 0.295 |

| 3. To what extent do residents support each other to address practical problems, such as where to find needed services, how to find employment, and transportation? | 3.51 | 1.20 | 0.764 | 0.326 | 0.310 |

| 4. To what extent do residents go to 12‐step meeting together? | 3.29 | 1.40 | 0.379 | 0.636 | 0.453 |

| 5. How effective are house meetings in terms of resolving problems and conflicts? | 3.45 | 1.31 | 0.477 | 0.591 | 0.424 |

| 6. To what extent are residents involved in decisions that affect the house? | 2.89 | 1.29 | 0.397 | 0.541 | 0.550 |

| 7. To what extent do residents work a 12-step recovery program on a daily basis within the SLH environment? This would include things like using 12‐step principles to address conflicts and other problems. | 3.20 | 1.40 | 0.334 | 0.754 | 0.321 |

| 8. To what extent do residents point out potential harm that could result from relapse or not continuing to work a strong recovery program? | 3.30 | 1.34 | 0.393 | 0.651 | 0.422 |

Note. Recovery Home Environment Scale (RHES) items rated on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) Not at all, (2) A little, (3) Somewhat, (4) Quite a bit, (5) A lot

Sites and Participants

The current study is part of a larger, ongoing study examining longitudinal outcomes of residents in SLHs. The sample for the current analyses consisted of 373 individuals residing in 44 SLHs in Los Angeles who were recruited into the larger study and completed the RHES at their 1-month interview. Mangers or owners of the SLHs were contacted and their houses were invited to participate. All houses were recruited through contact information obtained from the Sober Living Network, which is an association of SLH houses located in Southern California. Recruitment of houses targeted a mix of residences located in different geographical sections of Los Angeles. We also sought a mix of houses by gender and socioeconomic status of the neighborhoods where they were located. Of the 44 houses recruited, 22 were for men, 11 for women, and 11 were mixed gender residences. 20% of the houses were located in West Los Angeles, 20% in Central Los Angeles, 30% in San Gabriel/San Fernando Valley, and 30% in South Bay/Long Beach. The distribution by neighborhoods included 25% in low income areas, 20% in low-middle income areas, 27% in middle-high income areas, and 27% in upper income areas.

Our goal was to maximize generalization of research findings, so few inclusion/exclusion criteria were stipulated. To be enrolled in the study, residents needed to be competent to provide informed consent. The other inclusion criterion was that the person needed to be in the house for a period of at least one month. The rationale was that residents needed a reasonable period of time in the house to formulate their views about the social environment. Table 1 displays the majority of the sample was male (63.8%), White/Caucasian (52.0%), 30 years of age or older (75.3%), never married (63.0%), childless (70.5%), not currently on parole/probation (71.4%), earner less than $12, 490 annually (62.9%), and was unstably housed in the past 6 months (87.4%). A little over a quarter (28.7%) reported receiving substance use treatment in the past 30 days and all but 26.5% reported substance use in the 6 months prior to SLH entry.

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics (N=373)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 135 | 36.2 |

| Male | 238 | 63.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 194 | 52.0 |

| Black/African-American | 58 | 15.6 |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 96 | 25.7 |

| Other/Mixed | 25 | 6.7 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 92 | 24.7 |

| 30–39 | 109 | 29.2 |

| 40+ | 172 | 46.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never Married | 235 | 63.0 |

| Married/Live-in Partner | 14 | 3.8 |

| Separated/Divorced/Other | 124 | 33.2 |

| Parental Status | ||

| No Children | 263 | 70.5 |

| Children | 110 | 29.5 |

| Days of Substance use in the Past 6 Months (M, SD) | 50.4 | 56.9 |

| Past 30 Day Treatment Status | ||

| At least 1 Day of Treatment | 107 | 28.7 |

| Legal Status (N=371) | ||

| n | % | |

| Income (N=372) | ||

| $12,490 or Less | 234 | 62.9 |

| > $12,490 | 138 | 37.1 |

| Prior Housing Status | ||

| Own Home or Rent | 47 | 12.6 |

| Temporarily Housed | 279 | 74.8 |

| No Fixed Housing | 47 | 12.6 |

Procedures

Data collection took place between November 2016 and May 2020. House managers were contacted on a regular basis to monitor persons entering the homes. When a new resident was admitted, they were contacted within one month of their entry date by a research interviewer and invited to participate. After the study participation was described, those who were interested signed an informed consent document. All study participants were required to provide some type of contact information so they could be reached for follow-up interviews. The initial baseline interview was then completed, which took approximately one to two hours. To assess improvement on outcome measures, a similar assessment was made at 6 months. An interview was also conducted one month after entering the house. The purpose of that interview was to ascertain residents’ perceptions of the recovery environment in the SLHs. The one-month time period was chosen because it enabled the participant adequate time to experience social dynamics in the household and form opinions about them. All study procedures were approved by the Public Health Institute Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Sample characteristics measured at baseline consisted of standard items assessing gender, age, race, and marital and parenting status. The Addiction Severity Index (McLellan, Luborsky, Woody, & O’Brien (1980) was used to assess socioeconomic status and treatment during the past 30 days . The Timeline Follow-Back Interview (Sobell, et al., 1996) assessed days of substance use over the past 6 months.

The Community Oriented Program Environment Scale (COPES) was developed to study mental health and substance abuse treatment environments (Moos, 1997). The scale consists of 1oo items divided into 10 subscales: Involvement, Support, Spontaneity, Autonomy, Practical Orientation, Personal Problem Orientation, Anger and Aggression, Order and Organization, Program Clarity, and Staff Control. Items reflecting each domain are scored true or false and subscale scores range from 0 −10. Standard scores were used for all analyses. Psychometrics of the COPES have varied depending on the population and service setting. For example, Moos (1997) reported generally acceptable levels of internal consistency in his work assessing community-based residential substance abuse and mental heal programs. However, in a study of Oxford Houses (Harvey & Jason, 2011), eight of the ten scales had low internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha <0.70). Internal consistency for the subscales used with our sample included Involvement (alpha=0.79), Support (alpha=0,76), and Anger and Aggression (alpha= 0.67).

Length of Stay (LOS) was assessed as the number of days residing in the home from date of entry to exit. In previous studies of SLHs LOS was found to be a strong indicator of subsequent substance use (Polcin et al., 2016).

Days of Alcohol or Drug Use was assessed as the number of days of any substance use between entry into the SLH and 6-month follow-up. Data were collected using the Time-Line-Follow-Back (Sobell, et al., 1996).

Analysis

Mean scores and standard deviations for each of the eight items in the scale were calculated to describe resident perceptions of social model characteristics in the houses. To assess unidimensionality of the measure created with the RHES items, we conducted a principal components analysis. Because of the natural clustering of residents within the sober living houses studied, we created factor scores (using the regression method) for residents and calculated Intra Class Correlations (ICCs) to examine how much of the variation in residents’ scores could be attributed to their house. We also ran sensitivity analyses conducting multilevel exploratory factor analysis in Mplus to examine factor structure at the within and between levels.

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency of the resulting scale and subscales. To assess construct validity, we examined correlations between scores on the RHES scales and subscales from the COPES. Predictive validity was examined by assessing the associations between the RHES and two outcome measures at 6-month follow-up: length of stay and days of substance use. These analyses consisted of linear regression models adjusting for baseline sample characteristics. With the exception of the aforementioned multilevel factor analysis, all analyses were conducted in Stata v16.0 (StataCorp, 2019).

Results

As Table 2 indicates, seven of the eight items on the total RHES scale had mean scores between “somewhat” and “quite a bit.” The one exception was the item measuring resident involvement in decisions that affect the house (Item 6), which had a mean of 2.89 (sd=1.29). The highest means were on items the assessing extent to which there is support for practical problems, extent to which residents socialize together, and the effectiveness of house meetings. All three of these items had over half the participants indicating “quite a bit” or “a lot.” Standard scores for the three COPES subscale used to support construct validity revealed moderate degrees of Involvement (mean=50.70, sd=11.58) and Support (mean=49.59, sd=12.03). The Anger subscale was somewhat lower (mean=42.53, sd=10.77).

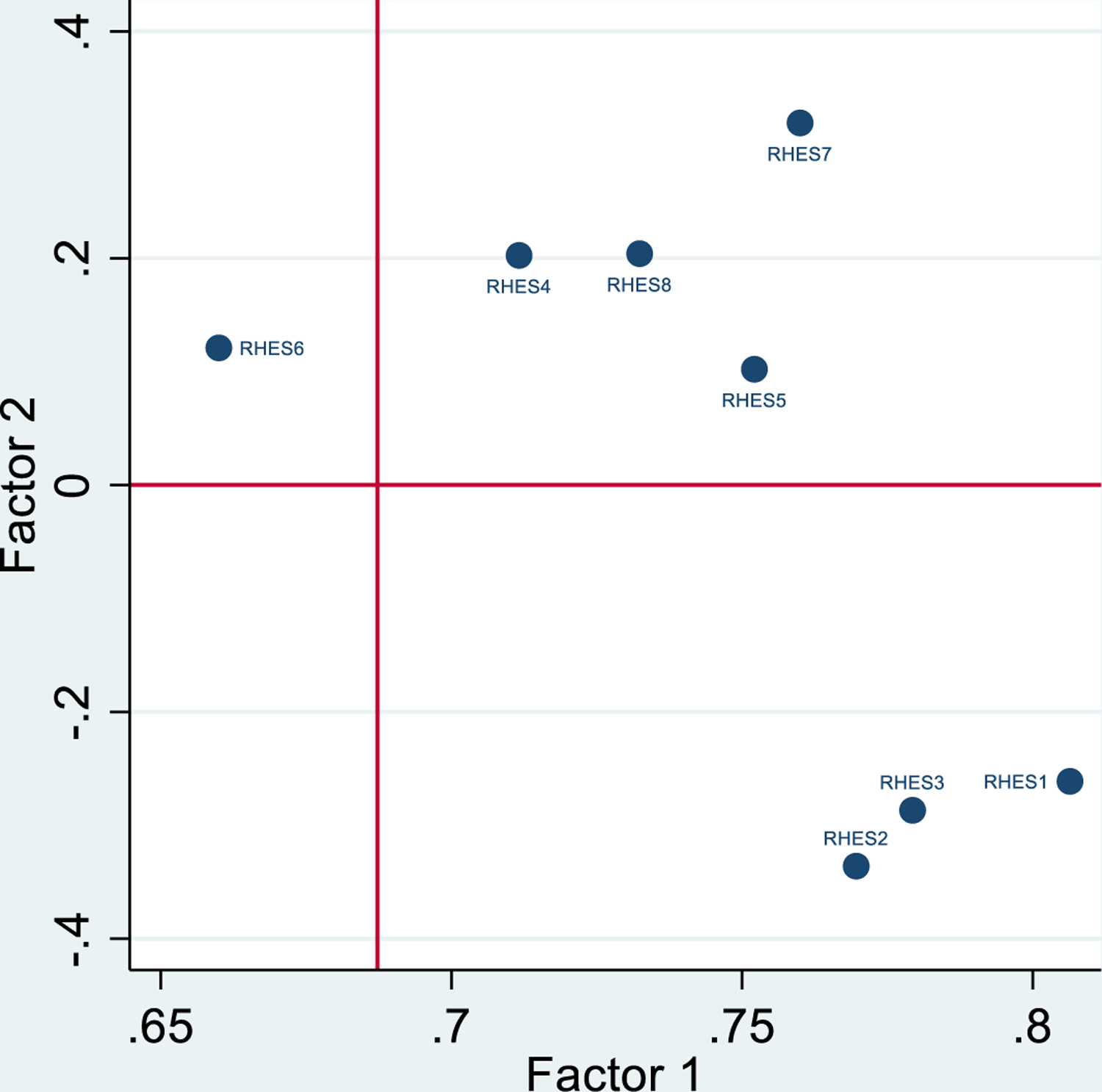

Principal components analysis of the of the RHES suggested that it was largely unidimensional, with the only one factor containing an Eigen value greater than 1, which comprised 61% of the variance among the eight RHES items. As Figure 1 displays, exploratory factor analysis suggested that items could further be broken into two groups: items 1–3 and items 4–8. Rotated factor loadings are also presented in Table 2. Items 1–3 query residents about emotional support, practical support, and resident socialization together; these items speak to recovery support provided in the residence. Items 4–8 include questions about groups of residents attending 12-step meetings together, the practice of 12-step principles among residents in the house, the effectiveness of house meetings to resolve conflict, and supportive confrontation about potential harm associated with relapse. These items speak to recovery skills developed within the house.

Figure 1.

Factor Loadings

Notes. Unrotated principal factors

Factor scores were created for these two groupings of items to examine potential clustering of scores among residents by house. Intraclass correlations calculated from null mixed-effects models were generally small for both the recovery support and the recovery skills scores (0.14 and 0.24, respectively) given the number of residents and the number of houses, but they were by no means negligible (Musca et al., 2011). To ensure that the observed factor structure would hold up when potential clustering by SLH was explicitly modeled, we reran the exploratory factor analysis in Mplus. Goodness-of-fit across multiple models was evaluated using standard fit indices (e.g., model chi-squared test, normed comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Models with two within factors fit better than models with one within covariance were virtually identical, thus supporting results obtained with the initial analyses. factor, and fit statistics comparing models with one between factor and unrestricted between

Internal consistency of items using the total scale was strong (alpha=.90), as were alphas for the recovery support (alpha=.89) and recovery skills (alpha=.87) subscales. As predicted, construct validity was supported by correlations between the total RHES scale and subscales scores on the COPES. Table 3 shows, total RHES score was positively associated with the COPES Involvement (r=0.66, p<0.001) and Support (r=0.63, p<0.001) scales but negatively associated with the Anger and Aggression scale (r=−0.191, p<0.01).

Table 3.

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients (Pairwise Correlations) for RHES and CPES Subscales

| RHES Score | CPES: Involvement | CPES: Support | CPES: Anger & Aggression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHES Score | 1.000 | |||

| CPES: Involvement | 0.656** | 1.000 | ||

| CPES: Support | 0.639** | 0.732** | 1.000 | |

| CPES: Anger & Aggression | −0.191* | −0.346** | −0.339** | 1.000 |

Notes.

p<0.01;

p<0.001

As hypothesized, predictive validity was supported using measures of length of stay and days of substance use (Table 4). Six-month follow-up data were available for a total of 275 residents who completed the 1-month interview (some had not yet come due for their six-month follow-up interview at the time the data were analyzed). Among this group, mean length of stay was 179 days (sd=116); median length of stay was 170 days. Mean days of alcohol or drug use at 6 months was 17 (sd=38); the median days of use was 0. In regression models adjusting for sample characteristics assessed at baseline, RHES total score was positively associated with length of stay (Coef=2.81, p=0.002) and negatively associated with number days substances were used over the past 180 days measured at the 6-month interview (Coef=−0.64, p=0.035).

Table 4.

Regression Model Examining RHES Score and Length of Stay (LoS) and Substance Use at 6-month Follow-up Adjusting for Baseline Sample Characteristics

| LoS | Days of Use at 6m Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | p | Coef | SE | P | |

| RHES Score | 2.81 | 0.90 | 0.002 | −0.64 | 0.30 | 0.035 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (Ref) | ||||||

| Male | 23.60 | 15.18 | 0.121 | 12.91 | 5.07 | 0.011 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White (Ref) | ||||||

| Black/African-American | −19.86 | 21.05 | 0.346 | 2.77 | 6.94 | 0.690 |

| Latinx/Hispanic | −18.41 | 17.90 | 0.305 | 3.25 | 5.99 | 0.587 |

| Other/Mixed | 3.23 | 30.87 | 0.917 | −1.48 | 10.23 | 0.885 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 (Ref) | ||||||

| 30–39 | 7.33 | 20.89 | 0.726 | −4.34 | 7.04 | 0.538 |

| 40+ | 8.97 | 21.44 | 0.676 | −10.07 | 7.24 | 0.165 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Never Married (Ref) | ||||||

| Married/Live-in Partner | 18.76 | 41.16 | 0.649 | 6.47 | 13.64 | 0.636 |

| Separated/Divorced/Other | −9.48 | 18.01 | 0.599 | 0.31 | 6.01 | 0.958 |

| Parental Status | ||||||

| No Children (Ref) | ||||||

| Children | −18.64 | 17.71 | 0.293 | 6.24 | 5.88 | 0.290 |

| Days of Substance use in the Past 6 Months at Baseline | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.301 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.021 |

| Past 30 Day Treatment Status | ||||||

| No Drug/Alcohol Treatment (Ref) | ||||||

| At least 1 Day of Treatment | −2.50 | 16.29 | 0.878 | 0.54 | 5.38 | 0.919 |

| Legal Status (N=371) | ||||||

| Not on Probation/Parole (Ref) | ||||||

| Currently on Probation/Parole | −11.06 | 16.49 | 0.503 | 8.69 | 5.51 | 0.116 |

| Income (N=372) | ||||||

| $12,490 or Less (Ref) | ||||||

| > $12,490 | 11.75 | 16.07 | 0.465 | 6.26 | 5.36 | 0.244 |

| Prior Housing Status | ||||||

| Own Home or Rent (Ref) | ||||||

| Temporarily Housed | 10.26 | 23.13 | 0.658 | 8.96 | 7.67 | 0.244 |

| No Fixed Housing | −5.34 | 29.28 | 0.856 | 4.06 | 9.73 | 0.677 |

Discussion

The RHES was designed to study recovery home residents’ perceptions about aspects of the social environment, including interpersonal interactions, house operations, and 12-step activities. Overall, residents perceived the social environments of the SLHs where they lived to be supportive of their recovery by providing critical emotional, social, and practical support and help that would lead to developing practical skills (e.g., attending 12-step meetings and applying principle learned in those meeting within the house with fellow residents ) to assist them in maintaining their recovery.

Study findings show that residents of SLHs viewed elements of social model recovery to be consistently present in their homes “somewhat” to “quite a bit.” There was only limited variation of item means assessing various aspects of social model. However, items applying social model to practical issues were viewed as slightly stronger than others. Examples included receiving help from other residents to address practical issues such as transportation, finding a job, and how to find services they need. Another example included a slightly higher rating on the effectiveness of house meetings to address conflicts and problems.

The highest mean on the scale was on the item assessing the extent to which residents socialize together. Nearly 54% indicated “quite a bit” or “a lot” on this item. The responses here are important for several reasons. First, social isolation is known to be a relapse trigger for many persons and engaging in social activities with others counteracts isolation. Second, the fact that the socialization here is among persons in recovery is important. Alcohol and drug use in one’s social network have been shown to be associated relapse (Bond, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 2003), including in studies of SLH residents (Polcin et al., 2010).

Factor Structure and Validity

Our primary interest was to create an overall scale that measured the extent to which social model principles were evident in SLHs from the perspectives of residents. Factor analysis results showed that items on the RHES did, to a large extent, map onto one overall scale with strong internal consistency. However, we also found evidence for subscales we labeled Recovery Support and Recovery Skills. Thus, the scale can be used be used to assess these more narrowly focused issues in addition to the overall environment.

As expected, the RHES correlated with scales on the COPES, which supported construct validity. However, the RHES represents significant innovation in the assessment of social environments in SLHs and other types of recovery homes because it measures issues specific to social model recovery in these settings. In addition, the instrument is shorter and possesses psychometric properties that are stronger than the COPES. These include issues not addressed on the COPES, such as items addressing the practice of 12-step principles in the house, supportive confrontation about harms associated with relapse, and groups of residents attending outside meetings together.

Also as predicted, higher scores on the RHES was positively associated with length of stay and negatively associated with days of substance use. These findings lend support to the contention that the social environments within the houses are important and the study is one of very few showing favorable outcomes associated with measures of social model recovery.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

A number of limitations bear noting. First, the sample was collected in one type of recovery residence, SLHs. Additional research is needed to assess psychometric properties in other types of treatment and recovery settings. Additionally, the sample was limited geographically to Los Angeles County and studies are needed in other geographical locations. Additional research is also needed to assess associations with other outcomes (e.g., mental health, legal problems, employment, etc.) and to establish cut-points for determining ranges that promote optimal recovery outcomes. Finally, while the RHES assesses the extent to which social model principles are reflected in resident interactions, there are important aspects of social model not addressed, such as the architecture of houses where residents live (Wittman, Polcin, & Sheridan, 2017). Additional research is needed on the interface between architecture and social environment. Discussion of some of the architecture issues needing attention can be found in Wittman et al. (2014). Despite these limitations, study findings provide initial support for the reliability and validity of a scale to measure recovery home environments by focusing on recovery support and recovery skills developed within these residences.

Acknowledgement:

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant number DA042938. The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Bond J, Kaskutas LA, & Weisner C (2003). The persistent influence of social networks and Alcoholics Anonymous on abstinence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(4), 579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari J, Jason L, Davis M, Olson B, & Alvarez J (2004). Similarities and differences in governance among residents in drug and/or alcohol misuse recovery: Self vs. staff rules and regulations. Therapeutic Communities, 25(3), 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari J, Jason L, Sasser K, Davis M, & Olson B (2006). Chapter 3: Creating a Home to Promote Recovery: The Physical Environments of Oxford House. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 31(1–2), 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari J, Jason L, Blake R, Davis M, & Olson B (2006). Chapter 4: “This Is My Neighborhood”: Comparing United States and Australian Oxford House Neighborhoods. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 31(1–2), 41–49; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh DR, Jason LA, Davis MI, Olson BD, & Ferrari JR (2007). Friends, family, and alcohol abuse: An examination of general and alcohol-specific social support. American Journal on Addictions, 16(1), 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey R, & Jason LA (2011). Contrasting social climates of small peer-run versus a larger staff-run substance abuse recovery setting. American journal of community psychology, 48(3–4), 365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Guerrero M, Lynch G, Stevens E, Salomon‐Amend M, & Light JM (2020). Recovery home networks as social capital. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3), 645–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Greenfield TK, Borkman TJ, & Room JA (1998). Measuring treatment philosophy: A scale for substance abuse recovery programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 15(1), 27–36. 10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00246-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. (980). An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168, 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mericle AA, Miles J, Cacciola J, & Howell J (2014). Adherence to the social model approach in Philadelphia recovery homes. International Journal of Self-Help & Self-Care, 8(2). [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1988). Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale Manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1997). Evaluating Treatment Environments: The quality of psychiatric and substance abuse programs (2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Musca SC, Kamiejski R, Nugier A, Méot A, Er-Rafiy A, & Brauer M (2011). Data with hierarchical structure: impact of intraclass correlation and sample size on type-I error. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Recovery Residences. (2012). A primer on recovery residences: FAQ [Accessed: 2012–10–02. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6B7e01VSk]. Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: file://G:%5CPUBLIC%5CCopy%20Of%20B-pdfs%5CB1377.pdf [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill JV (1990). History of Oxford House, Inc. In Shaw S & Borkman T (Eds.), Social model alcohol recovery: An environmental approach (pp. 103–117). Bridge-Focus. [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL (2016). Co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems among homeless persons: suggestions for research and practice. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 25(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1179/1573658X15Y.0000000004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Henderson D, Trocki K, Evans K, & Wittman F (2012). Community context of sober living houses. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(6), 480–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, & Korcha R (2015). Motivation to maintain sobriety among residents of sober living recovery homes. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 6, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin D, Korcha R, Gupta S, Subbaraman MS, & Mericle AA (2016). Prevalence and trajectories of psychiatric symptoms among sober living house residents. Journal of dual diagnosis, 12(2), 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha R, Witbrodt J, Mericle AA, & Mahoney E (2018). Motivational Interviewing Case Management (MICM) for persons on probation or parole entering sober living houses. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 45(11), 1634–1659. doi: 10.1177/0093854818784099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Korcha RA, Bond J, & Galloway G (2010). Sober living houses for alcohol and drug dependence: 18-month outcomes. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 38(4), 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Mahoney E, & Mericle AA (2020). House manager roles in sober living houses. Journal of Substance Use, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Polcin DL, Mahoney E, Wittman F, Sheridan D, & Mericle AA (2020). Understanding challenges for recovery homes during COVID-19. International Journal of Drug Policy, 102986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Polcin DL, Mericle A, Howell J, Sheridan D, & Christensen J (2014). Maximizing social model principles in residential recovery settings. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 46(5), 436–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.960112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif S, George P, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, & Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014). Recovery housing: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(3), 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Cleland PA, Fedoroff IC, & Leo GI (1996). The reliability of the Timeline Followback method applied to drug, cigarette, and cannabis use. In Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy. New York, NY: November 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Viola JJ, Ferrari JR, Davis MI, & Jason LA (2009). Measuring in-group and out-group helping in communal living: Helping and substance abuse recovery. Journal of groups in qaddiction & recovery, 4(1–2), 110–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Polcin D, Korcha R, & Li L (2019). Beneficial effects of motivational interviewing case management: a latent class analysis of recovery capital among sober living residents with criminal justice involvement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittman FD, Jee B, Polcin DL, & Henderson D (2014). The setting is the service: how the architecture of the sober living residence supports community based recovery. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care, 8(2), 189–225. doi: 10.2190/SH.8.2.d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittman FD, & Polcin D (2014). The evolution of peer run sober housing as a recovery resource for California communities. International journal of self help & self care, 8(2), 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittman FD, Polcin DL, & Sheridan D (2017). The architecture of recovery: two kinds of housing assistance for chronic homeless persons with substance use disorders. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 17(3), 157–167. doi: 10.1108/DAT-12-2016-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]