Abstract

Objective:

Soluble CD14 (sCD14) is a circulating pattern recognition receptor involved in inflammatory signaling. Although it is known that sCD14 levels vary by race, information on the genetic and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk relationships of sCD14 in African Americans (AAs) is limited.

Approach and Results:

We measured sCD14 in plasma at the baseline exam from n=3492 AAs from the Jackson Heart Study. We evaluated associations between sCD14 and subclinical CVD measures, incident CVD events and mortality under three levels of covariate adjustment. We used whole genome sequence data from the Trans-Omics for Personalized Medicine (TOPMed) program to identify genetic associations with sCD14. Adjusting for CVD risk factors and C-reactive protein, higher sCD14 was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality (HR=1.25; 95% CI: 1.17, 1.32), incident coronary heart disease (CHD; HR=1.28; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.47) and incident heart failure (HR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.15, 1.41), but not stroke (HR=0.96; 95% CI: 0.84,1.09). Some of these relationships differed by age and / or sex: the association between sCD14 and heart failure was only observed in females; there was an association between sCD14 and stroke only at younger ages (in the lowest tertile of age, <49.4 years). We replicated the association between sCD14 levels with African ancestry-specific allele (rs75652866) on the CD14 region of chromosome 5q31. We additionally identified two novel statistically distinct genetic associations with sCD14 represented by index variants rs770147646 and rs57599368, also in the chromosome 5q31 region.

Conclusions:

sCD14 independently predicts CVD-related outcomes and mortality in AAs.

Keywords: CD14, CVD, genetics, epidemiology

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Cardiovascular Disease

Introduction

The protein cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14) plays an important role in innate immunity as a pattern recognition receptor involved in the activation of several pro-inflammatory signaling pathways,1 acting as a co-receptor for the detection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; endotoxin).2 CD14 exists as a membrane-bound form (mCD14) anchored to the cell surface by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol and expressed on monocytes, macrophages and neutrophils. Its soluble form (sCD14) derives from proteolytic cleavage of the mCD14 in addition to secretion from hepatocytes or intracellular vesicles.1 Levels of sCD14 increase during acute and chronic inflammatory conditions,1,3 and have been linked to diseases and risk factors characterized by inflammation, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,4

Significant racial differences exist in the prevalence of chronic diseases, such as CVD, between African Americans (AA) and White populations. Seeking to explain this disparity, multiple studies have demonstrated a mirroring difference in inflammatory biomarker levels. 4,5 Interestingly, levels of sCD14 tend to be lower in AAs relative to Whites.4,6 Despite this, there is evidence that the association between sCD14 and CVD outcomes may be stronger among AAs than Whites. A recent study by Olson et al. identified elevated sCD14 as a risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischemic stroke in AAs but not in Whites in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort.6 Similarly, two cohorts of White populations, the Framingham Heart Study and the Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME) Study, reported no evidence for association between sCD14 and a composite measure of incident atherosclerotic CVD8 and incident CHD.9 However, sCD14 was associated with an elevated risk of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, CHD, and stroke in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), a cohort of older and mostly White adults. The analyses in CHS were adjusted for race, but not stratified by race, and the observed elevated risk may have been in part driven by AA participants.4

Genetic studies of sCD14 levels are limited, especially in AAs. Three significant loci have been reported to be associated with sCD14 across two genome-wide association studies (GWAS): rs1063412, a missense variant of PIGC on chromosome 1q24, which encodes an enzyme required for glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis; an intronic variant, rs190197089, in solute carrier family 8 member A1 (SLC8A1) on chromosome 2p22; and multiple variants near the CD14 structural locus on chromosome 5q31.4,10 GWAS of sCD14 in AAs have been limited to just 528 AA participants in CHS.4

In order to further understand the relationship of sCD14 to CVD risk, as well as the genetic variants contributing to sCD14 levels in AAs, we analyzed sCD14 in the Jackson Heart Study (JHS), a large community-based cohort of AAs from Jackson, Mississippi with extensive follow-up for incident CVD events and mortality. We characterized the cross-sectional associations between sCD14 and CVD risk factors and subclinical CVD measures and assessed whether baseline sCD14 is a significant predictor for future incident CVD events. Finally, we used whole genome sequence (WGS) data from the NHLBI Trans-Omics for Personalized Medicine (TOPMed) program to identify genetic associations with sCD14. The results from this investigation help clarify the etiology of sCD14, and subsequently mitigate the gap in our knowledge of CVD risk in African Americans.

Materials and Methods

All data and materials have been made publicly available at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC) and can be accessed at https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/jhs/ and additionally at dbGaP (accession phs000964.v2.p1, phs000286.v5.p1, and phs000366.v1.p1) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Study population

The JHS is a longitudinal cohort of AAs aged 21 years and older from both urban and rural areas in the Jackson, Mississippi metropolitan area. The overall goal of the study was to identify reasons for the high prevalence of CVD among AAs and potential approaches to reduce CVD risk. Enrollment in the study included 5306 non-institutionalized self-identified AAs between 2000 and 2004. JHS includes a nested family cohort within the study (approximately 1/3 of the participants with genetic data). A range of measures including health behaviors, medication use, anthropometry, blood pressure, kidney function, diabetes, and CVD biomarkers were assessed at the baseline visit.11,12 Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, self-reported diabetes, or use of a diabetes medication within two weeks prior to the JHS clinical visit. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure >140/90 mmHg or use of blood pressure lowering medication. sCD14 was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) using EDTA plasma collected at the baseline exam and stored at −80°C. The inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was 14.0%. Serum C-reactive protein (CRP) assays were performed using an immunoturbidimetric CRP-Latex assay (Kamiya Biomedical Company).13

Subclinical CVD was assessed using computed tomography (CT), carotid ultrasound, and echocardiography with imaging data collection, reading, and quality control assessed as previously described.11,14,15 Briefly, carotid intima media thickness (cIMT) was quantified using B-mode ultrasonography as the maximum likelihood estimate of average right and left common carotid intima-media thickness.16 Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) was defined as left ventricular mass calculated using the American Society of Echocardiography formula.17 Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as LVMI >51. Ankle brachial index (ABI) was defined as the ratio of systolic blood pressure (SBP) of the posterior tibial artery to that of the brachial artery using Doppler ultrasound.18 All subclinical measures with the exception of the CT-ascertained measures were assessed at Exam 1. CT imaging for coronary and aortic calcium was conducted at Exam 2, a median of 4.4 years after Exam 1. Agatston scores19 were used to quantify calcified plaque. Heart and lower abdomen imaging were performed using a Lightspeed 16 Pro 16-channel multidetector system equipped with cardiac gating (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), using standard protocols developed for the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) studies.20

Clinical outcomes in JHS were assessed through 12/31/2016 and mortality through 12/31/2018. Incident CVD events were adjudicated using data from annual follow-up and medical record review using standardized diagnostic criteria adapted from the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study.21-23 Individuals with a prior history of stroke or CHD and those who did not consent to medical record review were excluded from incident event analyses. CHD included fatal CHD and non-fatal myocardial infarction. Heart failure (HF) hospitalizations were not adjudicated from the beginning of the study; rather, follow-up data was used to determine HF hospitalization status on 01/01/2005. Incident HF events were assessed among participants without a self-reported history of HF and without HF hospitalizations from Exam 1 to the beginning of 2005. HF events were assessed by hospitalization events, identified through annual follow-up telephone interviews, and compared with hospital discharge lists and death certificates by independent reviewers.

All study protocols were approved by appropriate institutional review boards, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

CVD risk factors

We assessed the cross-sectional associations between sCD14 levels and baseline participant characteristics using generalized estimating equations, assuming an independent correlation structure within families, with sCD14 level (transformed as a z-score, with estimates presented per standard deviation [SD] unit) as the primary predictor. Adjustments were made for age and sex and to account for familial relationships. The following quantitative traits were examined as outcomes: body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, SBP, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, fasting glucose, fasting triglycerides, and CRP. Binary traits included smoking status (current versus former/never), hypertension, and type 2 diabetes. CRP, triglycerides, and BMI were natural log transformed prior to analysis.

Subclinical and incident CVD events and mortality

We used similar generalized estimating equation models to assess the covariate-adjusted associations between sCD14 and subclinical CVD measures with sCD14 as the primary predictor. Quantitative traits were ABI, cIMT, LVMI, coronary artery calcium (CAC) Agatston score, and abdominal aorta calcium (AAC) Agatston score. Binary traits were presence of LVH, any AAC and any CAC. We progressively adjusted for the following sets of covariates: 1) age and sex; 2) BMI plus CVD risk factors including blood pressure medication use, diabetes, SBP, total cholesterol, HDL and current smoking status; and 3) CRP, a marker for systemic inflammation. AAC, CAC, LVMI, and cIMT were natural log transformed prior to analysis.

We used Cox proportional hazards models with sandwich-based variance estimation to evaluate covariate-adjusted associations of sCD14 with all-cause mortality and incident CHD, stroke and HF events. We used the same progressive covariate adjustment as was used in the subclinical CVD models. Only individuals with complete covariate data for models 1-3 were included in the analyses of subclinical and clinical CVD measures. We used the Bonferroni method to adjust the significance threshold to account for examining multiple outcomes, using a significance threshold of p≤0.006 for the eight subclinical outcomes examined and p≤0.013 for the four survival outcomes.

Based on our previous findings in REGARDS,6 we additionally assessed interactions between sCD14 and age and sex, and we present stratified results for models with significant interaction terms with a Bonferroni-adjusted threshold of p-value≤0.006 to account for examining the two interaction terms with four outcomes. We used SAS 9.3 (Carey, North Carolina) for the analyses.

Genetic analysis of sCD14 heritability

Heritability of sCD14 was estimated using a subset of 1364 related JHS individuals from 427 families, adjusting for age, sex, and 10 principal components (PCs) for global ancestry, using the SOLAR software package.24 Global proportions of African ancestry in JHS participants were estimated using the software package ADMIXTURE v1.3 using k=2 clusters.25 Local ancestry estimates in targeted regions were determined using the software package RFMix v1.6626 and the 1000 Genomes27 African and European reference populations after phasing using Eagle v2.4.1.28 We tested the associations between global (adjusted for age and sex) and local (adjusted for age, sex and the first 10 PCs) ancestry and inverse normalized sCD14 in R3.6.129 and PLINK v1.90,30 respectively.

Genome-wide analyses of sequence variants

Eligible JHS participants underwent ~30X WGS at the Northwest Genomics Center at the University of Washington through the NHLBI TOPMed program. Details of the sequencing, variant calling, and quality control (QC) protocols used in TOPMed are described at https://www.nhlbiwgs.org/data-sets. While sCD14 was the predictor in the non-genetic analyses described above, it was the outcome in the genetic analyses. Regression of inverse normalized (after a natural log-transformation) sCD14 on genotype was adjusted for age, sex, and the first 10 PCs. We used a linear mixed model approach to account for familial relationships, as implemented in SAIGE v0.35.8.831 on the University of Michigan ENCORE server (https://encore.sph.umich.edu). We included 31,143,179 single nucleotide variants and small indels with sequence depth >10 and minor allele count >7 (which roughly corresponds to a 0.01% minor allele frequency [MAF] in this analysis). A significance threshold of 1.0x10−9 was used for WGS single variant analyses.32 To assess the number of independent association signals at a given locus, we performed forward step-wise conditional regression analysis. For a subset of variants that were significantly independently associated with sCD14, we also examined their associations with outcomes (incident CVD events and mortality) using additive Cox proportional hazards models, controlling for age, sex, BMI, blood pressure medication use, diabetes, SBP, total cholesterol, HDL, current smoking status, and CRP. Rs770147646 was not considered due to the low minor allele frequency.

We also performed genome-wide gene-based testing for rare variants with inverse normalized sCD14 using the Optimized Sequence Kernal Association Test (SKAT-O) implemented in the Efficient and Parallelizable Association Container Toolbox (EPACTS) v3.4.1.33,34 We aggregated variants for association tests, grouping variants by gene and restricting to nonsynonymous and loss-of-function coding variants with MAF <5%. Using a Bonferroni correction for the number of tested genes containing more than one polymorphic variant (n=18,750), the p-value significance threshold was set to 2.7x10−6.

Results

Population characteristics and the association of sCD14 with CVD risk factors, subclinical CVD, CVD events and mortality

The demographic characteristics and CVD risk factors of the 3492 individuals in the JHS cohort with a measurement of sCD14 are shown in Table 1, as well as the associations of these characteristics with sCD14. The mean of sCD14 was 1248 (SD=316) ng/mL. The cohort was predominantly female (62.2%) with an average age of 56 years. Higher sCD14 was significantly associated with older age, female sex, current smoking status, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, triglycerides and CRP. There was a significant inverse relationship between sCD14 and BMI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of CVD risk factors in JHS and associations with sCD14

| Effect estimate of sCD14 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

Beta | 95% CI | p- value |

|

| sCD14 | 3492 | 1247.7 (315.9) | |||

| Age (Years) | 3492 | 55.6 (12.8) | 2.43 | (1.97, 2.88) | <0.001 |

| Male Sex (versus female) | 3492 | 1319 (37.8%) | −0.24 | (−0.3, −0.19) | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 3485 | 31.9 (7.3) | −0.01 | (−0.02, −0.01) | <.001 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 3485 | 101.2 (16.2) | −0.31 | (−0.75, 0.13) | 0.16 |

| Current Smoker (yes versus no) | 3462 | 459 (13.1%) | 0.31 | (0.25, 0.37) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension Status | 3492 | 2004 (57.4%) | 0.13 | (0.08, 0.18) | <0.001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 3458 | 136 (20) | 0.53 | (−0.03, 1.10) | 0.064 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 3458 | 81 (10) | −0.08 | (−0.36, 0.19) | 0.56 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 3490 | 807 (23.1%) | 0.27 | (0.22, 0.33) | <0.001 |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (mg/dL)* | 2591 | 90 (9) | 0.11 | (−0.23, 0.44) | 0.53 |

| Fasting Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 3237 | 108 (82) | 0.07 | (0.04, 0.10) | <0.001 |

| Statin Medication Use | 3459 | 485 (13.9%) | 0.04 | (−0.02, 0.11) | 0.19 |

| Fasting Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 3237 | 199 (41) | 0.57 | (−0.96, 2.10) | 0.47 |

| Fasting LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 3204 | 127 (37) | −0.87 | (−2.11, 0.37) | 0.17 |

| Fasting HDL Cholesterol l (mg/dL) | 3236 | 52 (15) | −0.55 | (−1.57, 0.47) | 0.29 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/dL) | 3490 | 0.5 (1) | 0.23 | (0.2, 0.26) | <0.001 |

Beta values are reported per SD of sCD14 (316 ng/mL), including for binary measures. Models are adjusted for age and sex (except for age and sex). BMI, triglycerides, and CRP are natural log transformed prior to analysis.

Plasma glucose was obtained from fasting blood samples and was assessed only in those without type 2 diabetes.

The relationship between sCD14 and subclinical measures of CVD are shown in Table 2. Only ABI was associated with sCD14 after applying a multiple testing correction (Bonferroni threshold of p=0.006); when adjusting for age, sex, BMI, CVD risk factors and CRP, higher sCD14 was associated with slightly lower ABI (β=−0.014; 95% CI: −0.019, −0.008). We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with ABI>1.3. Values above 1.3 may indicate calcification, hardening and narrowing of blood vessel walls of the medial arteriers at the ankle.35 Results after this exclusion were similar (data not shown).

Table 2:

Cross-sectional associations of sCD14 with subclinical CVD measures in JHS

| Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2† | 3‡ | ||||||

| N | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

Beta (95% CI) | p-value | Beta (95% CI) | p- value |

Beta (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) | 2836 | 1.2 (0.2) | −0.018 (−0.023, −0.012) | <.001 | −0.015 (−0.02, −0.009) | <.001 | −0.014 (−0.019, −0.008) | <.001 |

| Carotid intima media thickness (cIMT) | 3021 | 0.7 (0.2) | −0.005 (−0.01, 0.001) | 0.11 | −0.008 (−0.013, −0.002) | 0.01 | −0.008 (−0.015, −0.002) | 0.01 |

| Left Ventricular Mass Index | 2056 | 36 (9.6) | 0.005 (−0.008, 0.019) | 0.44 | 0.004 (−0.01, 0.019) | 0.57 | 0.003 (−0.012, 0.018) | 0.73 |

| Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) Score | 1787 | 157 (489) | 0.11 (0.02, 0.21) | 0.02 | 0.02 (−0.07, 0.1) | 0.71 | −0.01 (−0.121, 0.101) | 0.86 |

| Abdominal Aorto-iliac Calcium (AAC) Score | 1786 | 861 (1600) | 0.27 (0.05, 0.49) | 0.02 | 0.1 (−0.09, 0.3) | 0.30 | 0.08 (−0.14, 0.3) | 0.50 |

| Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH) | 2233 | 150 (4.7%) | 0.13 (0.01, 0.24) | 0.04 | 0.09 (−0.04, 0.23) | 0.17 | 0.09 (−0.07, 0.24) | 0.28 |

| Any AAC | 1936 | 1173 (37.0%) | 0.14 (−0.03, 0.31) | 0.11 | 0.03 (−0.16, 0.21) | 0.78 | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | 0.94 |

| Any CAC | 1937 | 845 (26.6%) | 0.115 (0.001, 0.229) | 0.05 | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.12) | 0.69 | 0.003 (−0.12, 0.125) | 0.97 |

Beta values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported per SD increase in sCD14 (316 ng/mL). P-values meeting the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 0.006 are shown in bold.

CIMT, LVMI, CAC and AAC were natural log transformed prior to analysis.

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 2: Model 1 + BMI, blood pressure medications, type 2 diabetes, SBP, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, current smoking

Model 3: Model 2 + CRP

In prospective analyses of clinical events, sCD14 was associated with higher adjusted risk for mortality (HR=1.19; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.25) and incident CVD outcomes, including CHD (HR=1.29; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.44) and HF (HR=1.21; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.32) (Table 3). There was nominal evidence for an association between sCD14 and incident stroke, but only in the minimally adjusted model controlling for age and sex (HR=1.2; 95% CI: 1.01,1.42). When comparing the effect estimates of sCD14 to those of standardized CRP (per 1-SD), another biomarker of inflammation (Supplementary Table I), sCD14 was more strongly associated with increased risk of mortality, CHD and HF than CRP, whereas CRP was more strongly associated with risk of stroke.

Table 3:

Associations of sCD14 with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease events in JHS

| Model | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2† | 3‡ | |||||||||

| Outcome | Events | N | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| All-Cause Mortality | 716 | 3,171 | 1.27 | (1.19,1.35) | <.001 | 1.23 | (1.16,1.29) | <.001 | 1.19 | (1.13,1.25) | <.001 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 123 | 2,904 | 1.45 | (1.29,1.63) | <.001 | 1.32 | (1.18,1.48) | <.001 | 1.29 | (1.16,1.44) | <.001 |

| Heart Failure | 227 | 2,755 | 1.25 | (1.15,1.36) | <.001 | 1.20 | (1.11,1.3) | <.001 | 1.21 | (1.11,1.32) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 125 | 2,990 | 1.20 | (1.01,1.42) | 0.04 | 1.10 | (0.93,1.29) | 0.26 | 1.00 | (0.88,1.14) | 0.997 |

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported per standard deviation increase in sCD14 (316 ng/mL). P-values meeting the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of 0.013 are shown in bold.

Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex

Model 2: Model 1 + BMI, blood pressure medications, type 2 diabetes, SBP, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, current smoking

Model 3: Model 2 + CRP

We secondarily investigated whether the associations between sCD14 and clinical outcomes were modified by age or sex by testing for interactions of these variables with sCD14. We observed significant interactions between sex and sCD14 in relation to risk of HF and between age and sCD14 in relation to risk of stroke (Table 4). The association between sCD14 and HF was only observed in females (HR=1.35; 95% CI: 1.19, 1.51 versus HR=0.92 ; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.08 in males).The association between sCD14 and stroke risk was significant at younger but not older ages (HR=1.44; 95% CI: 1.17, 1.77 at <49.4 years [lowest tertile] versus HR=0.92; 95% CI: 0.82, 1.05 ≥62.4 years [highest tertile]).

Table 4:

Stratified regression results for the association of sCD14 with heart failure and stroke events in the JHS

| Outcome | Stratum | Events | N | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Failure | Female | 144 | 1,732 | 1.32 | (1.18,1.47) | <0.001 |

| Male | 83 | 1,023 | 0.94 | (0.79,1.11) | 0.44 | |

| Stroke | <49.4 years | 13 | 1051 | 1.45 | (1.11,1.88) | 0.006 |

| 49.4-62.4 years | 40 | 1009 | 1.14 | (0.9,1.44) | 0.29 | |

| ≥62.4 years | 72 | 930 | 0.93 | (0.78,1.12) | 0.47 |

The relationship between sCD14 and heart failure was significantly modified by sex (pinteraction=0. 005); and between sCD14 and stroke by age (pinteraction<0.001). Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported per standard deviation increase in CD14 (316 ng/mL) by strata of sex or age (tertiles). P-values meeting the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold of p≤0.006 are shown in bold.

Genetic analysis of sCD14

We estimated the heritability (h2) for inverse normalized sCD14, after adjusting for age, sex, and 10 PCs for ancestry in 1364 JHS participants (h2 = 0.33; standard error [SE] = 0.08; p = 9.0x10−6). The individual variant association analysis using WGS data was performed in 3352 JHS TOPMed participants. There was a trend for an association between higher estimated African global ancestry (β=−0.34, SE=0.19, p=0.068) and local ancestry at chromosome 5q31 (β=−0.11, SE=0.07, p=0.08) and lower inverse normalized sCD14 levels. Covariate adjustment for the three independently associated CD14 region variants (described below) removed all evidence for association with local ancestry at chromosome 5q31 (β=−0.01, SE=0.07, p=0.92). There was no genome-wide significant evidence for any association between local ancestry and sCD14 anywhere across the genome (all p>1x10−4; data not shown).

Single variant based tests of association

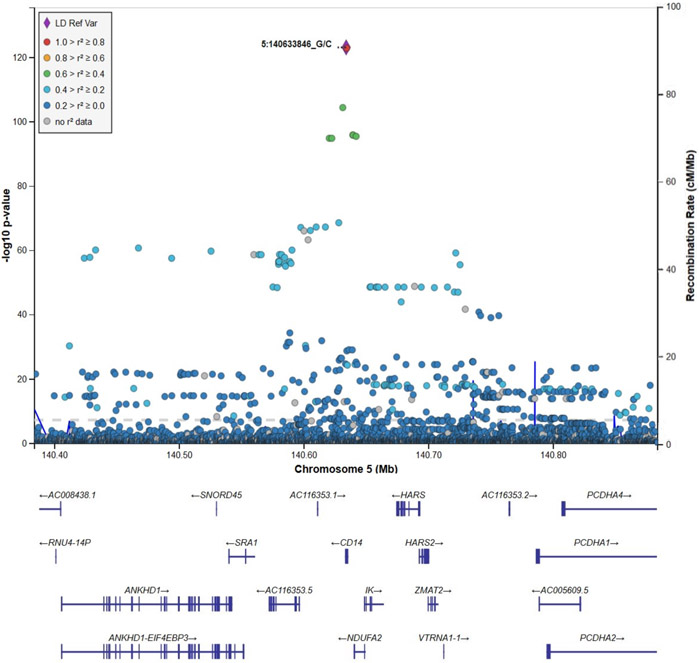

In WGS single variant-based association analyses of the 3349 JHS TOPMed participants, a single genomic region at chromosome 5q31 containing the CD14 gene was associated with sCD14 levels (Supplementary Figure I), and there was no evidence for any systematic inflation of results (λ=0.99; Supplementary Figure II). 527 individual variants were statistically significant at the genome-wide level of 1.0x10−9 in the region. The index variant in this region was rs75652866 at chr5:140633846 (β=−0.99, representing the change in inverse-normalized sCD14 for each copy of the minor allele; SE=0.04; p=6.6x10−124; MAF=0.091), a promoter variant for CD14 (CD14-775C>G) (Figure 1). After additional covariate adjustment for rs75652866, 17 individual variants remained significant, including index variant rs770147646 (6472del) at chr5:140632229 (β=−2.56; SE=0.30; pcond=2.2x10−17; MAF=0.0013), a rare frame-shifting deletion of a single base (G) in the coding sequence of CD14 (Supplementary Figure III). Individuals carrying one copy of the minor alle for rs770147646 had ~2.5 SD decrease in sCD14 (Supplementary Figure IV). After conditioning on both rs75652866 and rs770147646, 12 variants remained statistically significant, including index variant rs57599368 at chr5:140612528 (β=−0.24; SE=0.04; pcond=9.1x10−12; MAF=0.11), which is ~19Kb downstream of CD14 (Supplementary Figure V). Interestingly, rs57599368 was not genome-wide significant (p=1.3x10−4) prior to conditioning on rs75652866, the overall top variant in the initial single variant analyses. No variant remained significant (all p>1.0x10−9) after adjustment for the three index variants. None of the variants significantly associated with sCD14 were associated with risk of mortality or CVD events (p>0.05).

Figure 1:

Locus-Zoom plot of chromosome 5q31 for association with sCD14 in unconditional single variant analyses showing top result, rs75652866 (Chr5:140633846).

JHS results for genetic variants previously associated with sCD14

The observed association in JHS at the top chromosome 5q31 index variant, rs75652866, was consistent with the prior observed top index variant, rs5744451, in CHS AAs.4 Variants rs5744451 and rs75652866 are in high linkage disequilibrium (LD; r2=0.93) in 1000 Genomes African-descent populations. Previously reported variant rs5744451 was the second most significant signal in our initial analyses (β=−1.00; SE=0.04; p=1.1x10−123; MAF=0.089). A previously reported associated variant in both CHS Whites and AAs, rs778584, was also associated with sCD14 in JHS AAs (β=−0.26; SE=0.03; p =2.3x10−23; MAF=0.32). Two additional significant loci in CHS Whites showed nominal evidence for association in JHS, including rs4914 (β=0.20; SE=0.05; p =1.8x10−5; MAF=0.075) and two variants in high LD, rs5744455 and rs5744441 (for each, β=−0.10; SE=0.04; p=0.02; MAF=0.085). In JHS, after conditioning on top variants (rs75652866, rs770147646 and rs57599368), rs5744451 (pcond=0.04), rs778584 (pcond=4.4x10−4), rs5744455 (pcond=0.01), and rs5744441 (pcond=0.01) remained nominally significant while rs4914 was no longer significant (pcond=0.07). Chromosome 2 variant rs190197089, an intronic variant in SLC8A1 that appears to be European specific based on 1000 Genomes data and identified to be associated with sCD14 in a Swedish cohort10 was too rare in JHS and was filtered out prior to analyses.

Similar to CHS AAs, there was no evidence for the chromosome 1 PIGC missense variant rs1063412 (p=0.92) in JHS under an additive model, a significant variant in CHS Whites.4 This missense variant (7264C>T), which is strongly associated with PIGC expression in whole blood based on data from GTEx v836 (lead eQTL variant rs2285170, which is highly correlated with rs1063412 (r2= 0.6558) in 1000G Phase 3 Europeans), has substantial allele frequency differences between African and European populations (Frequency of allele A → Ser is ~0.57 in Europeans and ~0.14 in Africans37). Upon further examination of CHS data, the mode of inheritance model for association of rs1063412 with sCD14 is more consistent with a recessive model for the European common allele (A → Ser) in CHS Whites (see Supplementary Table II). Interestingly, though the homozygous A/A genotype (corresponding to Ser/Ser) is uncommon in both CHS AAs and JHS AAs (frequency of 3% and 2%, respectively, compared to 32% in CHS Whites), a similar association pattern with comparable effect sizes to those observed in Whites was observed under the recessive model in AAs, suggesting the lack of strong supportive evidence at rs1063412 in AAs is due to low statistical power because of differing allele frequencies across populations (Supplementary Table II).

Gene-based tests of association

The initial gene-based association tests for sCD14 revealed 11 significant genes in a ~1 Mb region at chromosome 5q31 (Supplementary Figure VI). There was evidence for modest inflation of overall test results across the genome (λ=1.18; Supplementary Figure VII). No other genes outside of chromosome 5q31 were significant. After additional covariate adjustment for the top index variant from the single variant analyses, rs75652866, the only remaining significant gene was CD14 (p=1.9x10−12). Covariate adjustment for both rs75652866 and rs770147646 (a rare deletion in the coding region of CD14) resulted in no genes being significant.

Discussion

In a population of AA adults from the JHS, we observed that higher sCD14 is associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality and incident CHD and HF, after adjusting for established CVD risk factors and CRP. The association between sCD14 and HF was only observed in females. While no evidence of association was found between sCD14 and stroke in the combined cohort, we did observe an association among younger individuals. Finally, we identified two novel genetic associations in the CD14 region on chromosome 5q31, including a rare and large effect frameshift variant rs770147646, which was associated with lower sCD14 levels in individuals carrying one copy of the minor allele.

Our results in JHS for incident CHD, showing an approximate 25% increased risk per SD increase in sCD14 level after adjusting for CVD risk factors and CRP, are generally consistent with those reported in two prior studies that included AAs. In our previous study in CHS, a cohort of adults at least 65 years old, we reported an increase in incident CHD risk of approximately 10-15% (per 1-SD sCD14 increase) in a combined sample of Whites and AAs (in analyses adjusted for race).4 In a recent report from the REGARDS cohort, we showed in race-stratified analysis that the increased risk of incident CHD with higher sCD14 is larger at younger ages in AAs.6 The association between sCD14 and incident CHD was not significant in Whites in REGARDS, although there was a similar trend for higher risk associated with sCD14 at younger ages.7 In the current study, we did not observe a sCD14-by-age interaction for CHD. However, we did observe an interaction between sCD14 and age for stroke, such that sCD14 was most strongly associated with higher risk at younger ages. Additionally, the association between sCD14 and HF was driven by females. In stratified analyses, we saw no evidence for association between sCD14 and HF in males.

In both CHS (Whites and AAs combined) and REGARDS AAs, sCD14 was predictive of incident stroke,4,6 although the relationship was not significant after adjustment for CVD risk factors, subclinical CVD and inflammation biomarkers in CHS. In the JHS, we likewise observed a nominally significant association between sCD14 and stroke when adjusting for age and sex only, but not when adjusting for CVD risk factors. The definition of stroke varied across these studies; CHS and JHS included both hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes, whereas REGARDS excluded hemorrhagic strokes and included more ischemic stroke cases than JHS (though fewer than CHS). The estimated increase in ischemic stroke risk for AAs per SD sCD14 increase in REGARDS was larger (~40%) as compared to both CHS and JHS. Interestingly, this estimate is comparable to the effect size observed in JHS among younger individuals (below 49.4 years: ~45%), but this association was not observed at older ages. There was no evidence for an association of sCD14 with stroke risk among Whites in REGARDS. These collective results suggest the relationships of sCD14 with CVD risk may differ by age, sex, and race.

Associations of higher sCD14 with older age, female sex, current smoking, diabetes, CRP and lower BMI observed in the JHS confirm results from CHS and REGARDS.4,6 Higher sCD14 was associated with prevalent hypertension in CHS and JHS but not REGARDS and the relationships of sCD14 with lipid levels varied across studies.4,6 Results from several human studies have now observed lower sCD14 concentrations with higher BMI.2,4,6,38-40 This inverse association is potentially explained by a decrease in hepatocyte-secretion of sCD14 as a result of obesity-associated hepatic steatosis,39 or higher sCD14-LPS binding and internalization of the sCD14 receptor complex associated with a high-fat diet.1 Mechanisms underlying the inverse association between BMI and sCD14 require further elucidation.

In JHS, we observed a negative association of sCD14 with ABI, consistent with previous results in CHS.4 We also observed a nominally significant association between sCD14 and lower cIMT, which was unexpected, though this finding did not meet the significance threshold for multiple comparisons and could be spurious. Among those with HIV infection, higher sCD14 was related to IMT progression41,42 and coronary artery stenosis, but was not associated with CAC or calcified plaque.43 In the MONICA Project, sCD14 was positively associated with pulse wave velocity but not cIMT.2 Overall, the relationships between sCD14 and subclinical vascular disease are somewhat inconsistent. Large racially diverse cohort studies evaluating longitudinal associations of sCD14 with subclinical CVD measures may help clarify these relationships.

We identified two novel independent CD14 region variants (rs770147646 and rs57599368) associated with sCD14 levels and replicated another (rs75652866). While prior GWAS of sCD14 have been limited, results from CHS AAs and this investigation in JHS suggest some racial differences in the genetic etiology of sCD14 in the chromosome 5q31 region.4 The top index variant at chromosome 5q31 was rs5744451 in CHS AAs4 and rs75652866 in JHS; these variants are in high LD and are nearly African-ancestry specific (rs5744451 MAF in Europeans = 0.00013 and Africans =0.095; rs75652866 MAF in Europeans = 0.000067 and Africans = 0.09437). In JHS, the second index variant, rs770147646, is a rare African-specific coding single base-pair frame shifting deletion in CD14 (MAF in Europeans = 0.0000 and Africans =0.001537). Moreover, two strongly associated variants in CHS Whites, rs5744455 and rs5744441, which are in high LD (MAF in Europeans = 0.24 and Africans = 0.085), were only nominally associated with sCD14 in both CHS AAs and JHS AAs. These results demonstrate the importance of studying multi-ethnic populations for genetic risk factors influencing protein biomarkers.

In GTEx v8, neither rs57599368, rs75652866, nor their proxies (r2≥0.8, calculated using 1000G Phase 3 AFR LD) are conditionally distinct lead eQTLs for any gene in any tissue. However, in the large blood-based eQTLGen meta-analysis, rs57599368 is the lead eQTL for CD14. rs770147646 is absent from both eQTL resources, and rs75652866 is absent from eQTLGen due to low frequency in European ancestry populations, highlighting the need for more eQTL resources in African ancestry individuals. In our results, no gene-based tests remained significant after conditioning on the top index variants suggesting the index variants (or variants in LD with the index variants) explain most of the genetic variability of sCD14 levels in the chromosome 5q31 region. This demonstrates how long-range LD between regulatory variants strongly associated with a given trait and low frequency coding variants can confound gene-based tests. Conditional analyses were key for determining that these 5q31 region gene-based signals were mostly spurious. The gene-based test for CD14 remained the top, albeit only nominally significant, genome-wide result after conditioning on all three index variants, suggesting there may be additional uncommon coding variants of modest effect in CD14.

While this is the largest study to date of the epidemiology and genetics of sCD14 among AAs, there are notable limitations. To elucidate the relationship between sCD14 and subclinical events, longitudinal assessments of these measures would be helpful. We found evidence that the relationship between sCD14 and stroke varies with age, and the factors underlying these potential differences require elucidation. Due to the recessive inheritance and low prevalence in AAs of PIGC variant rs1063412, larger cohorts of AAs would be necessary to assess the association with sCD14.

In summary, in a cohort of AA adults, sCD14 was a strong predictor of CVD-related outcomes specifically CHD, HF and all-cause mortality with some differences in the relationship with HF by sex; sCD14 was also associated with stroke among younger individuals. We identified two novel independent associations signals in the chromosome 5q31 region and confirmed a previously reported association between sCD14 and an African-specific genetic variant, suggesting some racial differences in the genetic etiology of sCD14. This work adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that sCD14 may have clinical utility as a marker of CVD risk among AAs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Higher circulating levels of soluble CD14 (sCD14) are associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, incident coronary heart disease and heart failure among African American (AAs) adults.

Among younger AA males, higher sCD14 is associated with increased risk of stroke.

The results identified two novel genetic associations with sCD14, including a rare and large effect frameshift variant, and also confirm a previously reported association between sCD14 and an African ancestry-specific allele in the CD14 region of chromosome 5q31.

Acknowledgments

The authors also wish to thank the staff and participants of the JHS. We gratefully acknowledge the studies and participants who provided biological samples and data for TOPMed.

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A full list of participating JHS investigators and institutions can be found at https://www.jacksonheartstudy.org/.

Sources of funding

The JHS is supported and conducted in collaboration with Jackson State University (HHSN268201800013I), Tougaloo College (HHSN268201800014I), the Mississippi State Department of Health (HHSN268201800015I) and the University of Mississippi Medical Center (HHSN268201800010I, HHSN268201800011I and HHSN268201800012I) contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD).

This research project was supported by R01-HL132947 from the NHLBI. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) for the Trans-Omics in Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program was supported by the NHLBI. WGS for “NHLBI TOPMed: The Jackson Heart Study” (phs000964.v1.p1) was performed at the University of Washington Northwest Genomics Center (HHSN268201100037C). Centralized read mapping and genotype calling, along with variant quality metrics and filtering were provided by the TOPMed Informatics Research Center (3R01HL-117626-02S1; contract HHSN268201800002I). Phenotype harmonization, data management, sample-identity quality control, and general study coordination, were provided by the TOPMed Data Coordinating Center (R01HL-120393; U01HL-120393; contract HHSN268201800001I).

NCO was supported by R00HL129045 from the NHLBI. LMR was additionally supported by T32 HL129982 and KL2TR00249.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAC

Abdominal Aorto-iliac Calcium

- AAs

African Americans

- ABI

Ankle Brachial Index

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAC

Coronary Artery Calcium

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- cIMT

Carotid intima media thickness

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- HF

Heart failure

- JHS

Jackson Heart Study

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- LVH

Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

- LVMI

Left Ventricular Mass Index

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- REGARDS

REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- sCD14

Soluble CD14

- WGS

Whole genome sequencing

Footnotes

Disclosure

None

References

- 1.Granucci F, Zanoni I. Role of CD14 in host protection against infections and in metabolism regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poesen R, Ramezani A, Claes K, Augustijns P, Kuypers D, Barrows IR, Muralidharan J, Evenepoel P, Meijers B, Raj DS. Associations of Soluble CD14 and Endotoxin with Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Progression of Kidney Disease among Patients with CKD. CJASN. 2015;10:1525–1533. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03100315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernández-Real JM, Pulgar SP del, Luche E, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Waget A, Serino M, Sorianello E, Sánchez-Pla A, Pontaque FC, Vendrell J, Chacón MR, Ricart W, Burcelin R, Zorzano A. CD14 Modulates Inflammation-Driven Insulin Resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60:2179–2186. doi: 10.2337/db10-1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reiner Alex P, Lange Ethan M, Jenny Nancy S, Chaves Paulo HM, Ellis Jaclyn, Li Jin, Walston Jeremy, Lange Leslie A, Cushman Mary, Tracy Russell P. Soluble CD14. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2013;33:158–164. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cushman M, McClure LA, Howard VJ, Jenny NS, Lakoski SG, Howard G. Implications of Elevated C-reactive Protein for Cardiovascular Risk Stratification in Black and White Men and Women in the United States. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1627–1636. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.122093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson Nels C, Koh Insu, Reiner Alex P, Judd Suzanne E, Irvin Marguerite R, Howard George, Zakai Neil A, Cushman Mary. Soluble CD14, Ischemic Stroke, and Coronary Heart Disease Risk in a Prospective Study: The REGARDS Cohort. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9:e014241. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson Nels C, Koh Insu, Reiner Alex P, Judd Suzanne E, Irvin Marguerite R, Howard George, Zakai Neil A, Cushman Mary. Abstract 10: Higher Soluble CD14 Level is a Risk Factor for Ischemic Stroke in Black but Not White Participants of the Reasons for Geographical and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Stroke. 50:A10–A10. doi: 10.1161/str.50.suppl_1.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho JE, Lyass A, Courchesne P, Chen G, Liu C, Yin X, Hwang S, Massaro JM, Larson MG, Levy D. Protein Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in the Community. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morange PE, Tiret L, Saut N, Luc G, Arveiler D, Ferrieres J, Amouyel P, Evans A, Ducimetiere P, Cambien F, Juhan-Vague I. TLR4/Asp299Gly, CD14/C-260T, plasma levels of the soluble receptor CD14 and the risk of coronary heart disease: The PRIME Study. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;12:1041–1049. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R, Song J, Isgren A, Jakobsson J, Blennow K, Sellgren CM, Zetterberg H, Bergen SE, Landén M. Genome-wide study of immune biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid and serum from patients with bipolar disorder and controls. Translational Psychiatry. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0737-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman T, Wilson JG, Jones DW, Sarpong DF, Asoka S, Garrison RJ, Nelson C, Wyatt SB. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African Americans: Design and methods of the Jackson Heart Study. 2005;15:S6–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JG, Rotimi CN, Ekunwe L, Royal CD, Crump ME, Wyatt SB, Steffes MW, Adeyemo A, Zhou J, Taylor JH, Jaquish C. Study design for genetic analysis in the Jackson Heart Study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:S6–30-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox ER, Benjamin EJ, Sarpong DF, Rotimi CN, Wilson JG, Steffes MW, Chen G, Adeyemo A, Taylor JK, Samdarshi TE, Taylor HA. Epidemiology, Heritability, and Genetic Linkage of C-Reactive Protein in African Americans (from the Jackson Heart Study). The American Journal of Cardiology. 2008;102:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter MA, Crow R, Steffes M, Rock W, Skelton T, Heilbraun J, Evans G, Jensen R, Sarpong D. Laboratory, Reading Center, and Coordinating Center Data Management Methods in the Jackson Heart Study. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2004;328:131–144. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200409000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Fox CS, Hickson D, Sarpong D, Ekunwe L, May WD, Hundley GW, Carr JJ, Taylor HA. Pericardial Adipose Tissue, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: The Jackson Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1635–1639. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deere B, Griswold M, Lirette S, Fox E, Sims M. Life Course Socioeconomic Position and Subclinical Disease: The Jackson Heart Study. Ethn Dis. 26:355–362. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.3.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: Comparison to necropsy findings. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, et al. Measurement and Interpretation of the Ankle-Brachial Index. Circulation. 2012;126:2890–2909. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD, Detrano RC. Calcified Coronary Artery Plaque Measurement with Cardiac CT in Population-based Studies: Standardized Protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keku E, Rosamond W, Taylor H, Garrison R, Wyatt S, Richards M, Jenkins B, Reeves L, Sarpong D. Cardiovascular disease event classification in the Jackson Heart Study: methods and procedures. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:S6–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosamond Wayne D, Folsom Aaron R, Chambless Lloyd E, Wang Chin-Hua, McGovern Paul G, Howard George, Copper Lawton S, Shahar Eyal. Stroke Incidence and Survival Among Middle-Aged Adults. Stroke. 1999;30:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.4.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA, Investigators TA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Methods and initial two years’ experience. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint Quantitative-Trait Linkage Analysis in General Pedigrees. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maples BK, Gravel S, Kenny EE, Bustamante CD. RFMix: A Discriminative Modeling Approach for Rapid and Robust Local-Ancestry Inference. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;93:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh P-R, Palamara PF, Price AL. Fast and accurate long-range phasing in a UK Biobank cohort. Nature Genetics. 2016;48:811–816. doi: 10.1038/ng.3571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2018. https://www.r-project.org/

- 30.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou W, Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nature Genetics. 2018;50:1335–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulit SL, de With SAJ, Bakker PIW de. Resetting the bar: Statistical significance in whole-genome sequencing-based association studies of global populations. Genetic Epidemiology. 2017;41:145–151. doi: 10.1002/gepi.22032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Wu MC, Lin X. Optimal tests for rare variant effects in sequencing association studies. Biostatistics. 2012;13:762–775. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxs014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EPACTS - Genome Analysis Wiki. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/EPACTS

- 35.Ankle Brachial Index: Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2012;39:S21–S29. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182478dde [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science. 2020;369:1318–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Td L, Lm S, Aj H, Tr M, Jl M, La W-M, Dj R. Interaction of CD14 haplotypes and soluble CD14 on pulmonary function in agricultural workers. Respir Res. 2017;18:49–49. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0532-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor BS, So-Armah K, Tate JP, et al. HIV and Obesity Comorbidity Increases Interleukin 6 but not Soluble CD14 or D-dimer. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:500–508. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raj DS, Carrero JJ, Shah VO, Qureshi AR, Barany P, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Ferguson J, Moseley PL, Stenvinkel P. Soluble CD14 Levels, Interleukin-6, and Mortality Among Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:1072–1080. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna DB, Lin J, Post WS, et al. Association of Macrophage Inflammation Biomarkers With Progression of Subclinical Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis in HIV-Infected Women and Men. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1352–1361. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siedner MJ, Kim J-H, Nakku RS, Bibangambah P, Hemphill L, Triant VA, Haberer JE, Martin JN, Mocello AR, Boum Y, Kwon DS, Tracy RP, Burdo T, Huang Y, Cao H, Okello S, Bangsberg DR, Hunt PW. Persistent Immune Activation and Carotid Atherosclerosis in HIV-Infected Ugandans Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:370–378. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKibben RA, Margolick JB, Grinspoon S, Li X, Palella FJ, Kingsley LA, Witt MD, George RT, Jacobson LP, Budoff M, Tracy RP, Brown TT, Post WS. Elevated Levels of Monocyte Activation Markers Are Associated With Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Men With and Those Without HIV Infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Võsa U, Claringbould A, Westra H-J, et al. Unraveling the polygenic architecture of complex traits using blood eQTL metaanalysis. bioRxiv. Published online January 1, 2018:447367. doi: 10.1101/447367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.