Abstract

Substance use and psychopathology symptoms increase in adolescence. One key risk factor for these is high parent stress. Mindfulness interventions reduce stress in adults and may be useful to reduce parent stress and prevent substance use (SU) and psychopathology in adolescents. This study tested the feasibility and effects of a mindfulness intervention for parents on adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms. Ninety-six mothers of 11-17 year olds were randomly assigned to a mindfulness intervention for parents (the Parenting Mindfully [PM] intervention) or a brief parent education [PE] control group. At pre-intervention, post-intervention, 6-month follow-up, and 1-year follow-up, adolescents reported on SU and mothers and adolescents reported on adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Primary intent to treat analyses found that the PM intervention prevented increases in adolescent SU over time, relative to the PE control group. The PM intervention also prevented increases in mother-reported externalizing symptoms over time relative to the PE control group. However, PM did not have a significant effect on internalizing symptoms. PM had an indirect effect on adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms through greater mother mindfulness levels at post-intervention, suggesting mother mindfulness as a potential intervention mechanism. Notably, while mothers reported high satisfaction with PM, intervention attendance was low (31% of mothers attended zero sessions). Secondary analyses with mothers who attended >=50% of the interventions (n = 48) found significant PM effects on externalizing symptoms, but not SU. Overall, findings support mindfulness training for parents as a promising intervention and future studies should work to promote accessibility for stressed parents.

Clinical Trials Identifier:

NCT02038231; Date of Registration: January 13, 2014

Keywords: Mindfulness, Parenting, Intervention, Adolescence, Substance use, Externalizing behavior problems

Adolescence is a risk period for increases in substance use (SU) and several forms of psychopathology, including internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression and generalized anxiety), and some externalizing symptoms (Hankin et al., 1998; Johnston et al., 2018). Adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms have significant consequences, including increased risk for impaired driving, criminal activity, academic problems, and suicide (e.g., Bevilacqua et al., 2018; Windle et al., 2008). Further, adolescent SU (particularly early and heavy use) and psychopathology symptoms longitudinally predict substance use disorders and psychopathology diagnoses in adulthood (e.g., Chassin et al., 2002; Pine et al., 1999).

Parent Stress

Given the significant problem of adolescent SU and psychopathology, it is critical to develop novel, developmentally informed prevention programs that target known risk factors. One well-established risk factor for SU and symptoms is parent stress (Repetti et al., 2002). High parent stress (i.e., stress arousal) longitudinally predicts increased child and adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms (Burk et al., 2011; Neece et al., 2012). Parent stress may directly affect youth through exposure to high stress levels in the home (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Parent stress may also have indirect effects on youth outcomes through parenting and parent–youth relationship quality. High parent stress has been associated with more harsh, less warm, and less effective parenting behaviors (Belsky et al., 1996; Chan, 1994), and lower parent–youth bonding (Deater-Deckard, 1998), all of which are known to predict greater adolescent SU and psychopathology (Barnes et al., 2000; Galambos et al., 2003).

Parents may experience heightened stress in particular when their children go through adolescence. In adolescence, youth spend less time with parents and more time with peers, assert autonomy with parents, and show high emotional arousal and emotional lability due to multiple biological and social changes (Steinberg, 2001), all of which can stress parent-youth relationships. Consistent with this, many parents report that adolescence is the most stressful period of parenting (Pasley & Gecas, 1984). At the same time, adolescents still require close family relationships as they are exposed to peer contexts that may introduce risky behaviors (Kapetanovic et al., 2019; Steinberg 2001). Thus, interventions to decrease parent stress may be particularly useful for parents of adolescents.

Mindfulness Interventions

Given that parent stress predicts adolescent SU and symptoms, interventions that target and reduce parent’s stress levels may prevent SU and symptoms. One promising way to reduce parent stress is through mindfulness interventions. Mindfulness interventions are specifically designed to target and reduce stress levels. Mindfulness (“the practice of focusing full attention on the present moment intentionally and without judgement,” Kabat-Zinn, 1990) is hypothesized to increase awareness of and ability to tolerate thoughts and emotions, decrease over-reactivity to events, and increase responding to events in intentional ways. Mindfulness interventions (e.g., Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [MBSR], Kabat-Zinn 1982, 1990; Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy [MBCT], Segal et al. 2002) foster mindfulness through meditation, encouragement of present-minded awareness in daily life, and discussions of mindfulness applications to stress, coping, and relationships. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that mindfulness interventions reduce self-reported and physiological stress reactivity (Brewer et al., 2009) and stress-related disorders including anxiety, depression, and substance use as compared to treatment as usual or active controls in adults (Bowen et al., 2014; Hoge et al., 2013; Eisendrath et al., 2016) (and also in youth- Lin et al., 2019).

Mindfulness Interventions for Parents

Given evidence for mindfulness interventions in reducing stress in adults, researchers have called for their use with parents (Cohen & Semple, 2010). Other interventions for parents, such as parent training interventions, teach specific parenting skills and have effects on youth SU and psychopathology (e.g., Shelleby & Shaw, 2014; Spoth et al., 2001). However, while parent training interventions are useful, they typically have small to medium effect sizes and do not work for all families (Lundahl et al., 2006). It can be difficult to engage some parents in these interventions, particularly if they are highly stressed (Dumas, 2005). Further, parents who are unable to stay calm in the face of challenging adolescent behaviors may have difficulty implementing the parenting skills they learn (Maliken & Katz, 2013). Mindfulness interventions can reduce parent stress and emotional reactivity and thus may be a useful alternative or complement to parent training programs (Dumas, 2005).

Researchers have begun to develop mindfulness interventions for parents, which foster mindfulness practice, particularly in parenting. By teaching parents to practice mindfulness, mindfulness interventions for parents are hypothesized to reduce parent stress, improve parenting and parent-child relationship quality, and, through this, prevent child and adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms (e.g., Dumas, 2005). Mindfulness may reduce parent stress and improve parenting in several ways (Dumas, 2005; Duncan et al., 2009; Kabat-Zinn & Kabat-Zinn, 1997). First, mindfulness training can help parents increase awareness of their own and their adolescents’ emotions and decrease parents’ emotional reactivity to normative adolescent behaviors (e.g., bids for autonomy), allowing them to respond calmly and intentionally. Second, mindfulness can help parents be more present in interactions with adolescents, increasing parent–adolescent relationship closeness. Third, mindfulness training can help parents become less judgmental of and more compassionate towards their adolescent, and towards themselves as parents, which may improve parenting and parent–adolescent relationship quality and, through this, may prevent adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms. Consistent with this, higher levels of self-reported dispositional mindful parenting (e.g., low reactivity, high compassion in parenting) are correlated with more positive emotion in parenting and less negative parenting behavior (de Bruin et al., 2014; Turpyn & Chaplin, 2016) and lower externalizing and internalizing symptoms in children (e.g., Geurtzen et al. 2015; Parent et al. 2016).

Despite the potential of mindfulness interventions for parents, there are only a few published RCTs of these interventions. Uncontrolled trials have found mindfulness interventions to increase adaptive and mindful parenting and decrease child and adolescent externalizing symptoms (e.g., Bögels et al., 2014; Altmaier & Maloney, 2007). Three RCTs examined mindfulness training for parents of children with special needs or involved in child welfare compared to no-intervention control and found that mindfulness training decreased parent stress and child psychopathology symptoms (Benn et al., 2012- N = 60; Brown et al., 2018- N = 28; Neece, 2014- N = 46).

Four additional RCTs involved parents of adolescents. One found that a mindfulness intervention delivered to parents and children increased children’s attention regulation abilities compared to wait-list control in 41 9-12 year olds (Felver et al., 2017). Two RCTs of a mindfulness-infused parent-training program for parents of 10-14 year olds found that mindfulness-infused parent-training produced stronger effects than parent training alone (Coatsworth et al., 2010- N = 65) and stronger and more sustained effects, particularly for fathers (Coatsworth et al., 2015- N = 432), on adaptive parenting and parent-adolescent relationship quality. Fourth, our team conducted a RCT of a mindfulness intervention with 96 highly stressed mothers of adolescents (the Parenting Mindfully [PM] intervention). In our first paper on this study, we reported effects of PM on mothers’ mindfulness and parenting. We found that PM increased mothers’ mindfulness, and increased mother-adolescent relationship quality compared to a parent education control group (Chaplin et al., 2021). PM also reduced negative parenting for mothers of girls, but not boys. Notably, these four RCTs did not report effects on adolescent SU or psychopathology symptoms.

The Present Study

The present manuscript takes the next step by examining feasibility and effects of PM with stressed mothers, compared to a Parent Education (PE) minimal intervention control, on adolescent SU and symptoms, using a RCT design. We examined PM effects on growth in adolescent SU and externalizing and internalizing symptoms from pre-intervention through postintervention, 6-month, and 1-year follow-up. We hypothesized that PM would prevent increases in SU and prevent increases in (or lead to decreases in) externalizing and internalizing symptoms through 1-year follow-up compared to PE. In addition, we explored mothers’ mindfulness and mother–adolescent relationship quality (two variables that were affected by PM in this RCT, as previously reported- Chaplin et al., 2021) as mediators of PM effects on adolescent outcomes.

Method

Participants

Parents were recruited in 2014-2015 from a suburban community in the mid-Atlantic U.S. Participants were 96 mothers of 11-17 year olds who reported moderate to high stress. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at George Mason University. Both mothers and fathers were invited to participate, however, only 5 fathers attended intervention sessions with mothers. Thus, this report focuses on data for female primary caregivers (94% biological mothers, 4% adoptive mothers, 2% grandmothers), referred to as “mothers.” Similar to the local community, adolescent race was 62 (64.6%) Non-Hispanic White, 9 Hispanic White, 11 more than one race (e.g., Black and White), 5 Other Race, 4 Asian (with 1 Asian-Hispanic), 4 Black, and 1 Native American-Hispanic. Additional demographic information is in Table 1. Families were recruited through fliers posted/distributed at two community behavioral health services providers and mailings to households with 11-16 year olds in the local county. Recruitment materials targeted parents with high stress. 52.2% of adolescents were engaged in psychotherapy at the time of recruitment (in addition to PM/PE intervention).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations by Intervention Group for Demographics and Adolescent Outcomes

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | 6-Month F/U | 1-Year F/U | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 96* | n = 78 | n = 69* | n = 82* | |||||||||||||

| PM | PE | PM | PE | PM | PE | PM | PE | |||||||||

| n = 48 | n = 48 | n = 38 | n = 40 | n = 37 | n = 32 | n = 42 | n = 40 | |||||||||

| Demographics | M | SD | M | SD | ||||||||||||

| Adol Age | 13.98 | 1.69 | 14.00 | 1.49 | ||||||||||||

| Mother Age | 47.23 | 6.81 | 47.21 | 5.78 | ||||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | |||||||||||||

| Adol Male | 24 | 50.0 | 25 | 52.1 | ||||||||||||

| Adol White | 31 | 64.6 | 31 | 64.6 | ||||||||||||

| In Therapy | 24 | 50.0 | 26 | 54.2 | ||||||||||||

| Mom Married | 37 | 77.1 | 38 | 79.2 | ||||||||||||

| Mom College | 44 | 91.7 | 42 | 87.5 | ||||||||||||

| Income >100k | 30 | 63.8 | 31 | 64.6 | ||||||||||||

|

Adol Outcomes |

M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Sub. Use | 1.87 | 4.33 | 1.92 | 4.09 | 2.20 | 5.67 | 1.73 | 3.81 | 2.16 | 5.35 | 2.32 | 4.55 | 2.04 | 5.49 | 2.51 | 4.33 |

| Ext. Sx (MR) | 0.01 | 2.69 | 0.10 | 2.53 | −0.18 | 2.41 | 0.06 | 2.42 | −0.55 | 2.37 | 0.68 | 2.59 | −0.34 | 2.67 | 0.35 | 2.91 |

| Ext Sx (AR) | 0.02 | 1.66 | −0.05 | 1.63 | 0.12 | 1.93 | −0.16 | 1.32 | 0.03 | 1.70 | −0.13 | 1.42 | 0.16 | 1.81 | −0.19 | 1.43 |

| Int. Sx (MR) | 0.05 | 1.81 | 0.04 | 1.86 | −0.19 | 1.58 | 0.18 | 2.06 | −0.28 | 1.82 | 0.35 | 1.66 | −0.07 | 1.59 | 0.07 | 1.91 |

| Int Sx (AR) | 0.09 | 1.79 | −0.08 | 1.99 | 0.09 | 1.89 | −0.09 | 1.92 | −0.07 | 1.87 | 0.05 | 2.02 | −0.002 | 1.74 | 0.002 | 2.03 |

Note. F/U =Follow-up, Adol = Adolescent, White = Non-Flispanic White, College = College graduate, Income > 100k = Family income > $ 100,000/year; Sub. Use= Substance Use; Ext= Externalizing; Int= Internalizing; AR= Adolescent Reported; MR= Mother Reported, Sx = Symptoms. Externalizing and internalizing symptoms are composites of z-scored variables. In Therapy refers to adolescent being in psychotherapy at pre-intervention

n’s are slightly different for some variables, as noted in Methods section.

Interested mothers were screened by phone for inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were adolescent between 11-17 years old, adequate English proficiency to complete questionnaires, and elevated mother stress levels (mean score of at least 3 [on a 1-5 scale] for two questions adapted from perceived stress and parenting stress scales: “In the last month, how often have you felt stressed?” and “In the last month, how often have you felt stressed by parenting your teenager or worried about your teenager?”). Exclusion criteria were diagnosis of intellectual disability or psychotic disorder (for adolescent).

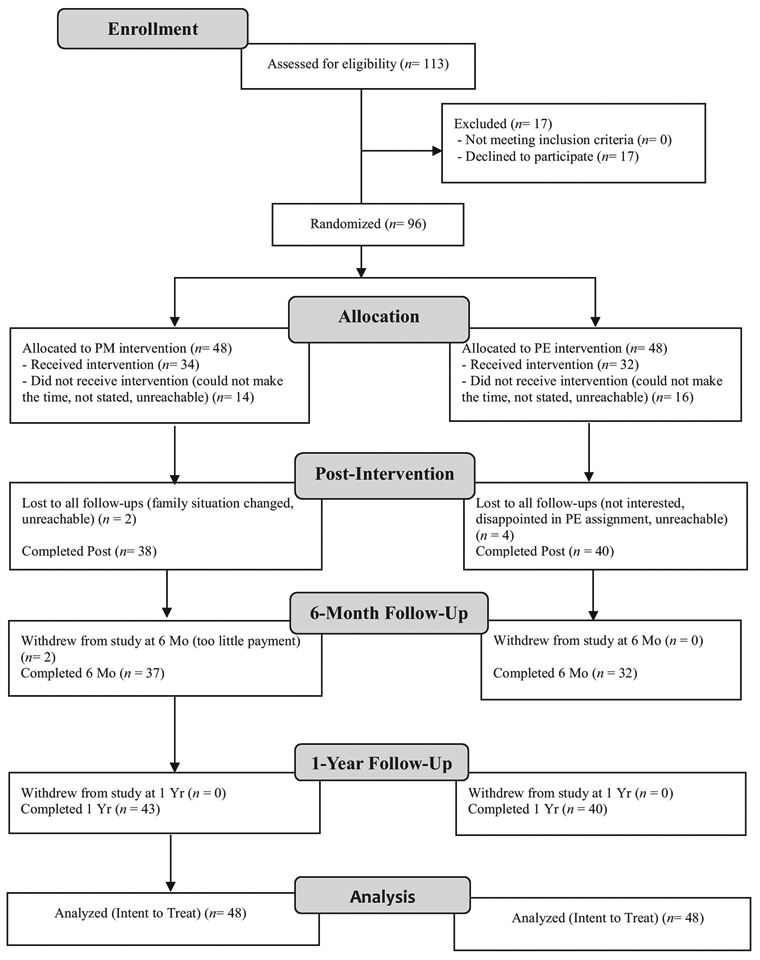

As shown in Figure 1, 96 families were randomly assigned to PM/PE and are the sample for analyses. 78 (81%) completed post-intervention, 69 (72%) completed 6-month, and 82 (85%) completed 1-year follow-ups. Six-month completion was low. One reason is that several families repeatedly cancelled their 6-months sessions until they entered the 1-year session timeframe. Completion of follow-ups was not correlated with any demographic or outcome variable at preintervention. There was an additional small amount of missing data due to refusal to complete measures (1-3 families were missing mother- or adolescent-report data at each time-point).

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram of PM Study.

Procedures and Interventions

Families were randomly assigned to PM (n = 48) or PE control (n = 48) using a computer-generated random numbers sequence. Families completed pre-intervention assessment sessions, the 8-week intervention phase, post-intervention sessions, 6-month follow-up sessions, and 1-year follow-up sessions. Assessment sessions included the questionnaires described below and additional interviews and tasks as part of the larger study. Informed consent and assent were obtained by trained research assistants before the start of the pre-intervention assessments.

PM.

The PM and PE interventions were group-based, with 10-16 parents per group. PM groups met for 2 hours once per week for 8 weeks, similar to prior mindfulness interventions (e.g., MBSR). PM focused on encouraging mindfulness in daily life and in parenting, based on mindfulness interventions for adults (e.g., MBSR, MBCT) and models of mindful parenting (e.g., Duncan et al. 2009). PM focused on increasing: 1. Present-focused awareness in daily life and in parenting, 2. Awareness of emotions in self and in adolescent, 3. Non-judgmental acceptance of experiences, including of the adolescent and of self as parent, 4. Non-reactivity to experience, including non-reactivity to normative adolescent behaviors (and using behaviors consistent with parenting values), and 5. Increasing compassion for self and adolescent. PM did not include explicit parent training beyond practicing present-focused awareness and reflecting on parents’ own parenting values.

PM sessions included: 1. Formal mindfulness practice (meditation or gentle yoga), 2. Discussion of and practice in informal mindfulness (e.g., practicing present-focus while eating), 3. Discussion of mindfulness applications to parenting, and 4. Discussion of homework. Homework was 30 minutes of formal mindfulness practice and 15-30 minutes of informal mindfulness practice in parenting interactions, 6 days per week. In session 6, adolescents were invited to attend. Adolescents and parents participated in meditation and practiced present-focused awareness during a parent-adolescent discussion.

PE.

PE was modeled on brief interventions used in prior SU prevention work (e.g., Turrisi et al. 2009) and was intended as a control for some non-specific factors, including expectancies for improvement and attending groups. However, as it was modeled on brief interventions, it included fewer sessions than PM (PE groups met 3 times for 30 minutes each time). At each PE group, the group leader handed out an informational packet, provided a power-point presentation, and answered parent questions. PE groups provided education on: 1. Adolescent physical and social development, 2. Changes in family and peer relations in adolescence, and 3. Adolescent risk behaviors (content based on pamphlets created by NIH- e.g., Robertson et al. 2003).

Intervention leaders.

Interventions were held in the behavioral health centers that were used for recruitment. PM Groups were co-led by the study co-investigator (co-I) and one doctoral student in clinical psychology or by two doctoral students. PE groups were led by a doctoral student in clinical psychology. Students received 16 hours of training and weekly supervision by study co-I (for PM) or the study Principal Investigator (PI) (for PE).

Measures

Substance use.

Adolescents reported on their SU in lifetime at each time-point on the Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2011 National Version (YRBS; CDC, 2017). The YRBS asks about number of days in lifetime using substances for 11 substances (e.g., alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalants) and number of days in past 30 using nicotine. For each substance, youth reported if they had never used it (scored a 0), used 1-2 days (scored 1), 3-9 days (scored 2), 10-19 days (scored 3), 20-39 days (scored 4), or 40 or more days (scored 5). We summed these scores across all substances to get a lifetime SU frequency variable (to reflect a combination of days used each substance and number of substances used). Of note, for nicotine, this reflects past 30 day use because the YRBS did not contain a lifetime nicotine use question. We also collected urine drug screens but those did not identify additional users who did not report use on YRBS. 30% of youth had used a substance at pre-intervention, consistent with national rates (Johnston et al., 2011). Of the users, 90% used alcohol, 38% used nicotine, 38% used marijuana, 17% used prescription drugs, 17% used inhalants, and 7% used ecstacy, methamphetamines, hallucinogens, or steroids (methamphetamine use was not due to ADHD medication). 41 adolescents (43%) used a substance at one or more time-point throughout the study.

Externalizing symptoms- mother report.

Mother-reported externalizing symptoms were a composite of the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI; Gadow & Sprafkin, 2002) Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) symptom subscale (8 items, rated 0-3, α = .93), the CSI Conduct Disorder (CD) symptom subscale (15 items, rated 0-3, α = .74), and the Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents (SIPA; Sheras et al. 1998) Adolescent Delinquency/Antisocial (ADDEL) subscale (10 items, rated 1-5, α = .83). The CSI is a widely used parent report of current child psychological symptoms that correlates with clinical interviews (Gadow & Sprafkin, 2002). The SIPA ADDEL is a subscale of a parent stress measure that assesses parent perceptions of current delinquent behavior and correlates with other externalizing measures (Sheras et al., 1998). Scores ranged from 0 to 24 for CSI ODD (M = 9.99, SD = 6.05), 0 to 17 for CSI CD (M = 2.57, SD = 3.23), and 10 to 37 for SIPA ADDEL (M = 16.50, SD = 6.49) at pre-intervention, similar to clinical samples (Gadow et al., 2002). CSI ODD, CSI CD, and ADDEL scores were z-scored (because of different scaling and numbers of items) and summed to create a composite score.

Externalizing symptoms- adolescent report.

Adolescents self-reported externalizing symptoms on the Youth Inventory-4R (YI: Gadow, Sprafkin, et al., 2002) ODD subscale (8 items, rated 0-3, α = .81) and CD subscale (15 items, rated 0-3, α = .82). The YI is a widely-used report of current symptoms that correlates with clinical diagnoses. Scores ranged from 0 to 24 for YI ODD (M = 7.12, SD = 3.84) and from 0 to 20 for YI CD (M = 1.97, SD = 3.52) at pre-intervention, similar to clinical samples. YI ODD and CD scores were z-scored and summed.

Internalizing symptoms- mother report.

Mother-reported internalizing symptoms were a composite of the CSI Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) subscale (11 items, rated 0-3, α = .85) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) subscale (7 items, rated 0-3, α = .85). Scores ranged from 0 to 30 for CSI MDD (M = 6.35, SD = 6.49) and from 0 to 21 for CSI GAD (M = 7.86, SD = 5.06) at pre-intervention, similar to clinical samples (Gadow, Nolan, et al., 2002). CSI MDD and GAD scores were z-scored and summed to create a composite score.

Internalizing symptoms- adolescent report.

Adolescents self-reported internalizing symptoms on the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI, Kovacs, 2001) (27 items, rated 0-2, α = .93) and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1997) (28 items, rated 0-1, α = .92). The CDI and RCMAS are self-reports of past 2 week depressive and current anxiety symptoms for adolescents. Scores from 0 to 48 on the CDI (M = 12.53, SD = 9.88), and from 0 to 27 on the RCMAS (M = 11.50, SD = 7.35), consistent with clinical samples (Chorpita et al., 2005; Timbremont et al., 2004). CDI and RCMAS scores were z-scored and summed to create a composite score.

Mother mindfulness.

The Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan 2003) is a self-report of mindfulness that measures the extent to which individuals experience present-focused awareness and attention (15 items, rated 1-6, α = .90). Items were scored such that higher scores reflected higher mindfulness and summed.

Mother–adolescent relationship quality.

The SIPA Adolescent-Parent Relationship Domain scale (Sheras et al. 1998) was used as a mother-report of mother-adolescent relationship, including the amount of affection and communication between them (16 items, rated 1-5, α = .88). Items were scored such that higher scores reflected higher relationship quality and summed.

Data Analyses

Covariates.

We considered adolescent age, race, therapy status (receiving psychotherapy), maternal education, and maternal past month SU at pre-intervention as potential covariates. We examined these variables as predictors in Hierarchical Linear Models (HLMs) predicting slope of the outcome variables. Adolescent age predicted slope of mother-reported internalizing symptoms at p = .05, and therapy status significantly predicted slope of mother-reported externalizing symptoms (p = .03). Based on this and the theoretical importance of these variables, we included age and therapy status as covariates in all analyses.

Main analyses.

We used intention-to-treat (ITT) for main analyses because ITT is considered the most rigorous approach to estimating intervention effects in real-world trials (Gupta, 2011) and has been used in RCTs with low attendance- e.g., Barkley et al., 2000). We conducted secondary analyses with mothers that attended at least 50% of intervention sessions (in Supplementary Materials). Our analytic approach involved creating growth models in HLM 8.0 software. On Level 1, HLMs predicted change in 5 outcome variables (SU and mother- and adolescent-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms) over time (pre-intervention through post-intervention, 6-month, and 1-year follow-ups). Time was modeled as the number of months before/since the start date of the intervention for that participant. On Level 2, person-attributes including intervention group (PM = 1 vs. PE = 0) and covariates (Adolescent Age – centered, and Therapy Status 0/1) were entered as having effects on both the intercept and slope. Random effects were estimated to allow for variability across individuals in their both their intercepts and slopes. Given sex differences in prior studies, we explored moderation of PM by adolescent sex by re-running the HLMs with sex and sex X intervention group as predictors.

Follow-ups.

For significant effects of group on slope of SU/symptoms, we calculated the proportion of variance in the slope explained by group by examining (variance component for level 2 slope in a HLM model without group – variance component for level 2 slope in model with group)/variance component in model without group. Based on this, we calculated an f2 effect size (see Lorah, 2018). f2 is considered small at 0.02, medium at 0.15, and large at 0.35. In addition, significant effects of intervention group on slope of SU/symptoms in HLMs were followed-up with ANCOVAs examining intervention group effects on SU/symptoms at each time-point, covarying pre-intervention SU/symptoms. Cohen’s deffect sizes from ANCOVA results were calculated. Cohen’s dis considered small at 0.20, medium at 0.50, and large at 0.80.

Exploratory analyses.

To explore mother’s mindfulness and mother-adolescent relationship quality as mediators, we first used regressions to confirm that intervention group predicted these variables at post-intervention. Next, we included mindfulness/relationship quality at post-intervention (centered) as an additional Level-2 predictor in the 5 HLM models above. If the mindfulness/relationship variable had an effect on slope in SU/symptoms in this model, we tested the indirect effect from group through mindfulness/relationship quality at post-intervention to SU/symptoms at 1 year, covarying pre-intervention SU/symptoms, age, and therapy status, in regression using the PROCESS Macro for SPSS with model 4 and 5,000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Session Attendance, Satisfaction, and Intervention Fidelity

Of the 96 mothers in our sample, 66 (69%) attended at least one intervention session and 30 (31%) attended zero sessions. Of the 30 non-attenders, 6 withdrew from the study altogether after being randomized (see Figure 1). Of the remaining 24 non-attenders, 6 did not attend due to scheduling conflicts (they could not make the time that groups were held) and 18 stated that they were too busy or did not state a reason. For mothers that attended, mean number of sessions was 4.65 (SD = 2.32) for PM and 2.16 (SD = 0.77) for PE (there were fewer PE sessions). Higher attendance correlated with mother being married (r = .22, p = .03), but no other variable.

Mothers reported on satisfaction with intervention groups from 1 (“not satisfied”), 2 (“a little satisfied”), 3 (“satisfied”), 4 (“very satisfied”), to 5 (“extremely satisfied”). Mean satisfaction was 4.18 (SD = 0.72; “very satisfied”) for PM and 3.62 (SD = 0.72, between “satisfied” and “very satisfied”) for PE. While both groups were satisfied, satisfaction was statistically higher in PM than PE (t[195] = 3.17, p < .01). The study co-I/PI reviewed audiotape and rated intervention fidelity (whether 6-10 concepts were covered) on a scale from 1 (not covered) to 3 (covered) (our use of co-I/PI as raters is a limit and may have introduced bias in the fidelity ratings). Mean fidelity was 2.96 (SD = 0.05) for PM and 3.00 (SD = 0) for PE.

Intervention Group Differences

There were no significant differences between PM and PE families on demographic variables, therapy status, or outcome variables at pre-intervention.

Data Inspection

Three outcome variables (SU and mother- and adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms) and one mediator variable (mother-adolescent relationship quality) had 1-3 outlier cases each, and these were winsorized (set equal to 3 SDs above/below the mean). Following this, the SU variable was still skewed and so was square root transformed for analyses (following transformation, skewedness = 2.13). SU had a number of zero values and so we conducted secondary zero-inflated modeling analyses. Means and SDs of outcome variables are shown in Table 1. Untransformed SU data is reported in Table 1 for ease of interpretation.

PM Intervention Effects on Adolescent SU and Symptoms

Substance use.

As expected given the random assignment, PM/PE groups did not differ at the intercept (b = −0.01, t[92] = −.08, p = .94), see Table 2. As predicted, HLM results showed a significant effect of intervention group on slope of adolescent SU (b = −0.02, SE = 0.01, t[92] = −2.27, p = .03), see Table 2. Adolescents in the PE condition grew significantly at 0.02 units per month and adolescents in the PM condition had a growth rate that was 0.02 units lower than the PE condition. In other words, substance use among PE adolescents grew while substance use among PM adolescents remained about the same. The addition of intervention group explained 6.5% of the variance in slope of SU compared to the model without intervention group, with a small effect size f2 = .07. (Of note- 12.0% of the overall variance in the unconditional growth model for SU is attributable to slope).

Table 2.

Results of Hierarchical Linear Modeling Analyses

| Substance Use (Adol-Reported) |

Externalizing Symptoms (Mother-Reported) |

Externalizing Symptom (Adol-Reported) |

Internalizing Symptoms (Mother-Reported) |

Internalizing Sx (Adol-Reported) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Coef. | df | t | Coef. | df | t | Coef. | df | t | Coef. | df | t | Coef. | df | t |

| For Intercept: | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.46 | 92 | 11.64*** | −0.37 | 92 | −0.09 | −0.43 | 92 | −2.19* | −0.65 | 92 | −2.88** | −0.72 | 92 | −2.50* |

| Adolescent Age | 0.25 | 92 | 4.28*** | 0.06 | 92 | 0.44 | 0.13 | 92 | 1.37 | 0.42 | 92 | 5.16*** | 0.38 | 92 | 4.22*** |

| Therapy Status | 0.01 | 92 | 0.07 | 1.08 | 92 | 2.24* | 0.73 | 92 | 2.49* | 1.44 | 92 | 5.07*** | 1.22 | 92 | 3.79*** |

| Intervention Grp | −0.01 | 92 | −0.08 | −0.48 | 92 | −0.48 | 0.10 | 92 | 0.34 | −0.14 | 92 | −0.50 | 0.22 | 92 | 0.68 |

| For Slope: | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.02 | 92 | 3.51*** | 0.05 | 92 | 3.26** | 0.03 | 92 | 1.84 | 0.02 | 92 | 1.60 | 0.03 | 92 | 1.84 |

| Adolescent Age | <0.01 | 92 | 1.07 | <0.01 | 92 | 0.41 | <0.01 | 92 | 0.76 | −0.01 | 92 | −2.39* | −0.01 | 92 | −1.30 |

| Therapy Status | −0.01 | 92 | −1.38 | −0.04 | 92 | −2.43* | −0.05 | 92 | −2.55* | −0.02 | 92 | −1.34 | −0.04 | 92 | −2.14* |

| Intervention Grp | −0.02 | 92 | −2.27* | −0.05 | 92 | −2.73** | 0.01 | 92 | 0.34 | −0.01 | 92 | −0.71 | −0.02 | 92 | −1.07 |

| Random Effects | Var | df | χ2 | Var | df | χ2 | Var | df | χ2 | Var | df | χ2 | Var | df | χ2 |

| Intercept | 0.57 | 84 | 1384.71*** | 5.50 | 86 | 982.41*** | 1.89 | 84 | 429.70*** | 1.62 | 86 | 424.64*** | 2.21 | 84 | 657.90*** |

| Slope | <0.01 | 84 | 243.06*** | <0.01 | 86 | 105.79 | <0.01 | 84 | 139.96*** | <0.01 | 86 | 122.95** | <0.01 | 84 | 180.54*** |

| Level-1 Error | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.59 | ||||||||||

Note. Adol = Adolescent; Grp = Group; Coef. = regression coefficient from HLM model, Var = Variance component. Therapy Status at pre-intervention was coded as 1 = adolescent in therapy, 0 = adolescent not in therapy. Intervention group was coded as 1 = PM, 0 = PE.

p< .05

p< .01

p< .001

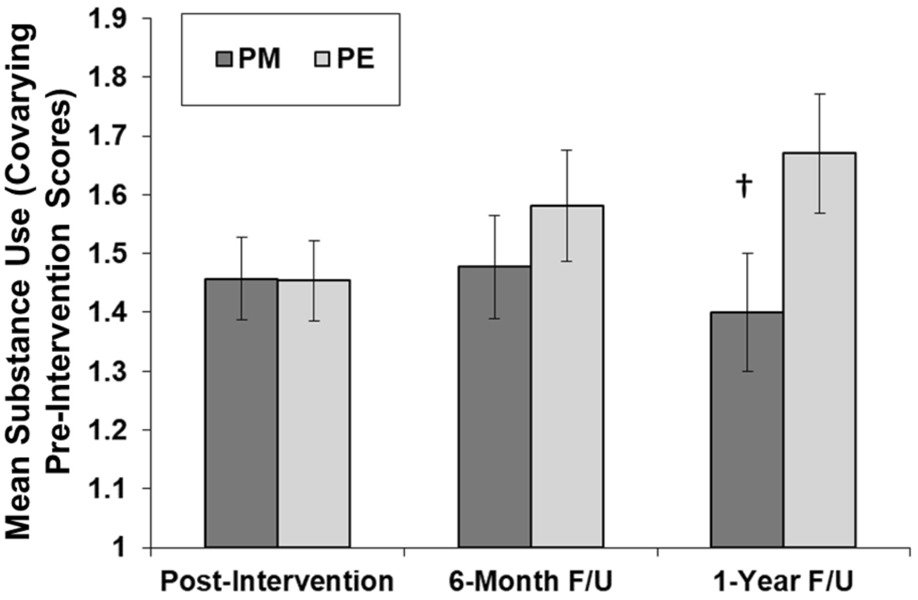

Follow-up ANCOVAs did not show significant intervention group differences in SU at post or 6-month follow-ups (post: F[1,73] = 0.001, p = .97, d = .01; 6-month: F[1,63]= 0.64, p = .43, d = −.20). There was a trend for an intervention group difference in SU at 1-year follow-up, covarying pre-intervention SU, with a medium effect size, F[1,73]= 3.57, p = .06. d = −.43), with PM youth showing lower SU than PE youth, see Figure 2. Using untransformed SU scores, at 1 year follow-up, estimated marginal mean SU scores were 1.72 (SE = .45) for PM and 2.83 (SE = .45) for PE (1 indicates 1-2 days, 2 indicates 3-9 days, and 3 indicates 10-19 days in lifetime using substances).

Figure 2. Mean Adolescent Substance Use through 1-Year Follow-Up for Parenting Mindfully (PM) and Parent Education (PE) Groups, Controlling Pre-Intervention Scores.

Note. Figure shows estimated marginal means from analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests at each time-point, using transformed scores (square root [substance use score +1]).

ᵻ indicates difference between the two groups at p < . 10

Secondary analyses.

First, as is common in studies of lifetime SU, 3 youth were inconsistent reporters (reported lifetime SU at pre-intervention, but not at follow-ups). We re-ran the above HLMs excluding these 3 youth and the intervention effect on SU slope was similar (b = −0.02, SE = 0.01, p = .045). Second, we conducted secondary HLMs using a zero-inflated modeling approach for SU. We examined growth in dichotomous use/no use. Then, we restricted analysis to users and examined growth in the continuous SU frequency variable. Intervention effects on slope were not significant for the use/no use model (b = −0.01, ns), but were significant for the continuous SU frequency model (b = −0.04, p = .04, f2 = .16).

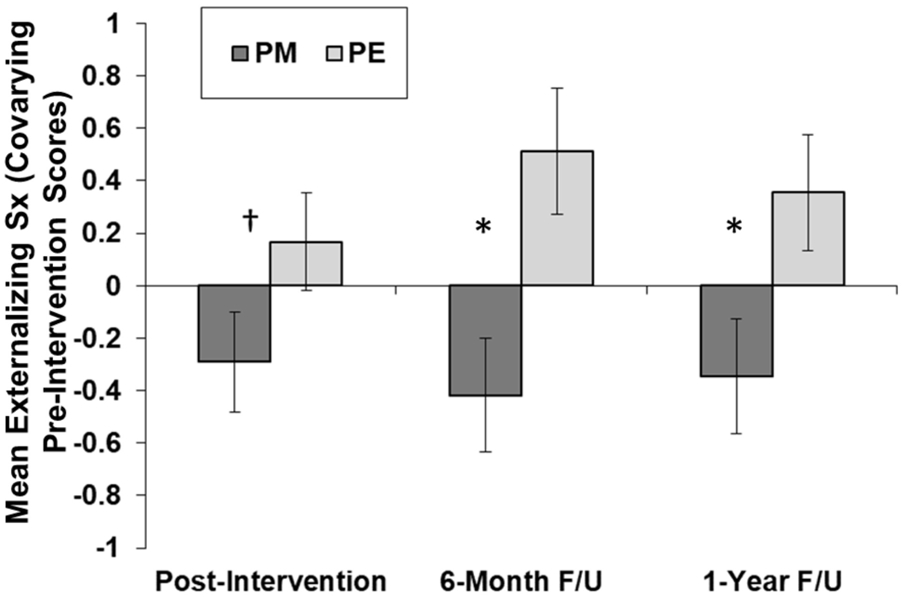

Externalizing symptoms, mother report.

As expected, there were no PM/PE group differences at the intercept (b = −0.48, t[92] = −.09, ns), see Table 2. As predicted, HLM results showed a significant effect of intervention group on slope of mother-reported externalizing symptoms (b = −0.05, SE = 0.02, t[92] = −2.73, p = .01), see Table 2. Adolescents in the PE condition grew significantly at 0.05 units per month. Adolescents in the PM condition had a growth rate that was 0.05 units lower than the PE condition. In other words, externalizing symptoms among PE adolescents grew while externalizing symptoms among PM adolescents remained about the same. The addition of intervention group explained 26.9% of the variance in slope of externalizing symptoms compared to the model without intervention group, with a large effect size f2 = .37. (Of note- 3% of the overall variance in the unconditional growth model for externalizing symptoms is attributable to slope).

Follow-up ANCOVAs showed a trend for an intervention group difference at postintervention with a medium effect size (F[1,73] = 2.91, p = .09. d = −.39), a significant intervention group difference at 6-month-follow-up with a large effect size (F[1,64] = 8.23, p = .01. d = −.70), and a significant intervention group difference at 1-year follow-up with a medium effect size (F[1,74] = 4.63, p = .04, d = −.48), with PM youth showing lower externalizing symptoms than PE youth.

Externalizing symptoms, adolescent report.

HLMs did not find a significant effect of intervention group on slope of adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms (see Table 2).

Internalizing symptoms.

HLM analysis did not find a significant effect of intervention group on growth in mother- or adolescent-reported internalizing symptoms (see Table 2).

Sex interactions.

Intervention group X adolescent sex interaction effects on growth in SU and symptoms were not significant and so moderation by sex was not supported.

Exploring Mediated Intervention Effects

Regressions found that intervention group significantly predicted mothers’ mindfulness and mother-adolescent relationship quality at post-intervention, covarying the variable at preintervention, with PM mothers reporting greater mindfulness (β = 0.21, t[73] = 2.24, p = .03) and better parent-adolescent relationship quality (β = 0.17, t[73] = 2.54, p = .01) than PE (see also Chaplin et al., 2021). In the HLM, mothers’ higher mindfulness at post-intervention significantly predicted lower slope in adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms from post through 1-year follow-up, controlling for intervention group (b = −0.002, SE = 0.001, t = −2.63, p = .01). The PROCESS analyses found a significant indirect effect of intervention group on externalizing symptoms at 1-year through mother mindfulness (Indirect effect = −0.22, SE = 0.15, Lower CI = −0.55, Higher CI = −0.004). HLMs did not find significant effects of mother mindfulness on other outcomes and did not find effects of relationship quality on outcomes.

Discussion

The present study was the first RCT to test effects of a mindfulness intervention for parents on adolescent SU and psychopathology symptoms (past RCTs with adolescents examined effects on parenting, but not on SU or symptoms). The PM intervention prevented increases in adolescent-reported substance use and mother-reported externalizing symptoms through a 1-year follow-up, compared to a minimal intervention Parent Education control, with small (for SU) to large (for externalizing symptoms) effect sizes and had an indirect effect on adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms through increased mother mindfulness. PM effects on internalizing symptoms were not significant. However, although mothers reported high satisfaction with PM, intervention attendance was low (31% of mothers did not attend any intervention groups). In secondary analyses of mothers that attended at least 50% of the intervention, PM prevented mother-reported externalizing symptoms, but not substance use.

PM Effects on Adolescent SU and Externalizing Symptoms

Effect sizes for PM effects on prevention of SU and mother-reported externalizing symptoms were similar to effect sizes found in traditional parent training programs, which are small to medium (Lundahl et al., 2006). Thus, mindfulness training may be a good alternative preventative intervention for parents who do not respond to (or have difficulty implementing) parent training focused prevention programs. Given that this study’s sample of mothers had elevated stress levels, it may be that parents with high stress is one group that is well-suited for mindfulness training. Our findings are also in line with two prior RCTs of mindfulness interventions for parents of young children who faced stressors (child welfare involved families- Brown et al., 2018; parents of children with developmental delays- Neece, 2014), which found medium to large intervention effects on child externalizing symptoms. The present study extends these findings to adolescence and to substance use. Given that adolescence is a critical period for the development of symptoms and SU and for family relationships, this is significant and future research should continue to test mindfulness interventions for parents of adolescents.

Attendance.

However, the promising results for PM must be tempered by considering that intervention attendance was low, raising concerns about feasibility. Low attendance is a common problem in preventative interventions with parents (e.g., Barkley et al., 2000- 35% of parents did not attend the intervention; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001- 37% did not attend). Typically, low attendance is due to parents being too busy (parents in our study frequently stated that they were too busy taking their children to activities and appointments to attend the evening groups) or having low perceived need for help (particularly because these are preventions) (Gonzalez et al., 2018). Future research should work to increase accessibility of PM for stressed parents and increase motivation to attend. To promote accessibility, internet-delivered versions of PM could be developed so that parents can attend sessions more easily. To promote motivation, research can used empirically-supported strategies including increased monetary compensation and group leader phone calls with parents that highlight positive effects of parent programs on youth outcomes (Gonzalez et al., 2018). Despite low attendance, mothers who attended reported high satisfaction with PM (a common pattern in parenting interventions- Gonzalez et al, 2018), suggesting that low attendance was not due to lack of satisfaction.

Notably, in the secondary analyses with those that attended at least 50% of the intervention, PM had significant effects on mother-reported externalizing symptoms, but not SU. These secondary analyses should be viewed with caution given that they selected a sub-set of participants, which introduces bias (Gupta, 2011). However, it is unusual that findings for SU were weaker for families that attended the interventions. This may be due to lower power in the sub-set analyses (see Gupta, 2011) or another variable that led non-attenders who were assigned to PM to show lower SU than PE (perhaps expectancies associated with being assigned to PM).

Substance use.

Notably, PM effects on lower SU found in the main ITT analyses increased over time following the intervention, with stronger results one year later than immediately post-intervention (Figure 2). Also, PM effects on SU were stronger for preventing increasing SU frequency than for SU initiation. The pattern of delayed effects of mindfulness training on SU has been found in other studies with adults (e.g., Bowen et al., 2014). Mindfulness can build over time. As parents tolerate negative emotions they increase exposure to emotions, leading to lower arousal (Bowen et al., 2014). This building parental mindfulness can be useful later in development, as adolescents encounter risks for increasing SU in the months (and years) after the intervention. The earlier effects of PM on externalizing symptoms may also have led to lower SU later, given that externalizing symptoms predict SU.

Externalizing symptoms.

PM showed prevention effects on mother-reported, but not adolescent-reported, externalizing symptoms. Parent interventions often have stronger effects on parent-reported constructs (e.g., Coatsworth et al., 2010), given that the interventions occur with parents. Mindfulness interventions may have particularly strong effects on parental perceptions of adolescents’ symptoms because they aim to increase parent understanding of their child’s emotions/behaviors. Finally, consistent with research finding that parents report greater levels of externalizing symptoms than adolescents in clinical samples (Bien et al., 2015), the present study found slightly higher means for mother- than adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms, which may have led to greater power to detect intervention effects.

Mediation.

Although PM did not have a direct effect on adolescent-reported externalizing symptoms, PM had an indirect effect on these symptoms through improving mother mindfulness (but not through mother-adolescent relationship quality). Perhaps improving mothers’ ability to calmly respond to adolescent behaviors helped shape adolescents’ view of themselves. However, mediation by mother mindfulness was only found for one out of five outcomes. This may be due to low power. Or there may be other more robust mediators, such as parent’s own SU or symptoms, that can be explored in future work.

PM Effects on Internalizing Symptoms

PM did not have significant effects on internalizing symptoms. Mindfulness training is theorized to help parents stay calm and use intentional parenting. Calm responses may be more necessary when parents are confronted with angry and non-compliant (externalizing) behaviors than with sad or anxious (internalizing) behaviors, as externalizing behaviors may be more aversive. Thus, mindfulness interventions for parents may have stronger effects on preventing externalizing behaviors. This pattern has been found in parent training interventions, which find stronger effects on externalizing than internalizing symptoms (Buchanan-Pascall et al., 2018).

Study Strengths and Limitations

The present study had several strengths. First, the study used a RCT design and included an active control group. However, the PM group had more contact hours than PE, included more group leaders, and involved one session that adolescents attended. Second, the present study included both mother- and adolescent-reported outcomes and found effects on both. However, there were several non-significant findings, such as for internalizing symptoms. Also, the main measure of SU was lifetime use, which may be less sensitive to change. Further, zero-inflated analyses found that PM was most effective in preventing increases in frequency of use in those who were already using substances, however our sample had many non-users. And secondary analyses with attenders (n = 48) were not significant for SU. Future studies should target adolescents with greater variability in use. Third, families in this study had elevated stress. However, most were White and high income. While PM was important to examine in our sample with elevated stress, future research should also examine PM with parents of color and lower income parents, who may experience unique stressors related to discrimination and poverty. Fourth, the study attempted to involve fathers. However, while we invited both caregivers, we had very low father attendance and thus our findings are limited to mothers.

Summary & Future Directions

Overall, our study adds to the growing literature on parent mindfulness interventions in showing that a stand-alone mindfulness intervention with highly-stressed mothers prevented increases in mother-reported externalizing (but not internalizing) symptoms and adolescent SU (in ITT but not in attender analyses) over a 1-year follow-up. If this is confirmed with larger trials, it suggests that teaching parents mindfulness may be a useful alternative for parents who do not respond to parent training focused prevention programs. The study also found some limited support for mother mindfulness as a potential mechanism of PM effects. Overall, the present study supports the application of mindfulness training for parents as a potential novel approach for prevention of externalizing symptoms and SU in adolescents.

Future studies should continue to examine effects of mindfulness interventions for parents on adolescent outcomes to confirm effect sizes. Future work should also focus on making PM more accessible. To do this, studies could continue to identify key mediators of PM and use this knowledge to create shorter versions of PM that target the key mediators. These can be delivered more easily either in-person or via internet delivery. The present study’s findings suggests that brief versions of PM should retain elements that target parent mindfulness, such as meditation. Future research could also examine moderators to determine which parents benefit from mindfulness training versus, for example, traditional parent training. This information can then be used to deliver personalized family-based interventions to prevent adolescent symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3. Mean Adolescent Externalizing Symptoms through 1-Year Follow-Up for Parenting Mindfidly (PM) and Parent Education (PE) Groups, Controlling Pre-Intervention Scores.

Note. Figure shows estimated marginal means from analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests at each time-point, using mother-reported externalizing symptoms composite scores (z scores of three externalizing symptom scales, summed).

ᵻ indicates difference between the two groups at p < . 10

* indicates significant difference p < .05) between two groups

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the study sponsor (NIH), the participating families, and the study research assistants.

Funding

Support for this project was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) through grants R34-DA-034823 (PI: Chaplin) and F31-DA-041790 (PI: Turpyn).

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material

Data and materials may be requested from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval

The present study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and therefore was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained for all adult participants. Informed parental/guardian consent and informed assent was obtained for all participants under age 18.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Altmaier E, & Maloney R (2007). An initial evaluation of a mindful parenting program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(12), 1231–1238. 10.1002/jclp.20395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Shelton TL, Crosswait C, Moorehouse M, Fletcher K, Barrett S, Jenkins L, & Metevia L (2000). Multi-method psycho-educational intervention for preschool children with disruptive behavior: Preliminary results at post-treatment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(3), 319–332. 10.1111/1469-7610.00616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Reifman AS, Farrell MP, & Dintcheff BA (2000). The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-year wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62(1), 175–186. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00175.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bein LA, Petrik ML, Saunders SM, & Wojcik JV (2015). Discrepancy between parents and children in reporting of distress and impairment: Association with critical symptoms. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(3), 515–524. 10.1177/1359104514532185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Woodworth S, & Cmic K (1996). Trouble in the second year: three questions about family interaction. Child Development, 67(2), 556–578. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8625728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn R, Akiva T, Arel S, & Roeser RW (2012). Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1476–1487. 10.1037/a0027537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua L, Hale D, Barker ED, & Viner R (2018). Conduct problems trajectories and psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(10), 1239–1260. 10.1007/s00787-017-1053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, & Larimer ME (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 547–556. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, Michalsen RN, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Grier A, Bergquist KL, Reis DL, Potenza MN, Carroll KM, & Rounsaville BJ (2009). Mindfulness training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: results from a randomized, controlled stage I pilot study. Substance Abuse, 30(4), 306–317. 10.1080/08897070903250241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Bender KA, Bellamy JL, Garland EL, Dmitrieva J, & Jenson JM (2018). A pilot randomized trial of a mindfulness-informed intervention for child welfare-involved families. Mindfulness. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Pascall S, Gray KM, Gordon M, & Melvin GA (2018). Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Parent Group Interventions for Primary School Children Aged 4-12 Years with Externalizing and/or Internalizing Problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 49(2), 244–267. 10.1007/s10578-017-0745-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk LR, Armstrong JM, Goldsmith HH , Klein MH, Strauman TJ, Costanzo P, & Essex MJ (2011). Sex, temperament, and family context: how the interaction of early factors differentially predict adolescent alcohol use and are mediated by proximal adolescent factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 1–15. 10.1037/a0022349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017) Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire: 2017 National Version. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbs. [Google Scholar]

- Chan YC (1994). Parenting stress and social support of mothers who physically abuse their children in Hong Kong. Child Abuse and Neglect, 18(3), 261–269. 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Turpyn CC, Fischer S, Martelli AM, Ross CE, Leichtweis RN, Miller AB, & Sinha R (2021). Parenting-focused mindfulness intervention reduces stress and improves parenting in highly-stressed mothers of adolescents. Mindfulness, 12, 1–15. 10.1007/s12671-018-1026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, & Prost J (2002). Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 67–78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11860058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Moffitt CE, & Gray J (2005). Psychometric properties of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour research and therapy, 43(3), 309–322. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Greenberg MT, & Nix RL (2010). Changing Parent's Mindfulness, Child Management Skills and Relationship Quality With Their Youth: Results From a Randomized Pilot Intervention Trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 203–217. 10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Gayles JG, Bamberger KT, Berrena E, & Demi MA (2015). Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the Mindfulness-Enhanced Strengthening Families Program. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 26–35. 10.1037/a0038212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JAS, & Semple RJ (2010). Mindful parenting: A call for research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 145–151. 10.1007/s10826-009-9285-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EI, Zijlstra BJ, Geurtzen N, van Zundert RM, van de Weijer-Bergsma E, Hartman EE, Nieuwesteeg AM, Duncan LG, & Bogels SM (2014). Mindful Parenting Assessed Further: Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Version of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale (IM-P). Mindfidness (N Y), 5(2), 200–212. 10.1007/s12671-012-0168-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, & Greenberg MT (2009). A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychoogyl Review, 12(3), 255–270. 10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisendrath SJ, Gillung E, Delucchi KL, Segal ZV, Nelson JC, McInnes LA, Mathalon DH , & Feldman MD (2016). A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(2), 99–110. 10.1159/000442260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felver JC, Tipsord JM, Morris MJ, Racer KH , & Dishion TJ (2017). The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Children's Attention Regulation. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21(10), 872–881. 10.1177/1087054714548032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, & Mackinnon DP (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Nolan EE, Sprafkin J, & Schwartz J (2002). Tics and psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 44, 330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J, Carlson GA, Schneider J, Nolan EE, Mattison RE, & Rundberg-Rivera V (2002). A DSM-IV–referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD & Sprafkin J (2002). Child Symptom Inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, & Almeida DM (2003). Parents do matter: trajectories of change in externalizing and internalizing problems in early adolescence. Child Development, 74(2), 578–594. 10.1111/1467-8624.7402017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurtzen N, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Tak YR, & van Zundert RM (2015). Association between mindful parenting and adolescents’ internalizing problems: Non-judgmental acceptance of parenting as core element. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(4), 1117–1128. 10.1007/s10826-014-9920-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Morawska A, & Haslam DM (2018). Enhancing initial parental engagement in interventions for parents of young children: A systematic review of experimental studies. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 415–432. 10.1007/s10567-018-0259-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK (2011). Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2(3), 109. 10.4103/2229-3485.83221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, & Angell KE (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 128–140. 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, Worthington JJ, Pollack MH, & Simon NM (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 786–792. 10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/142406/Overview%202017%20FINAL.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2011). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED528077.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General hospital psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full castrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn M & Kabat-Zinn J (1997). Everyday blessings: The inner work of mindful parenting. New York, NY: Hyperion. [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Skoog T, Bohlin M, & Gerdner A (2019). Aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship and associations with adolescent risk behaviors over time. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(1), 1–11. 10.1037/fam0000436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (2001) Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, Cicchetti C, Jessup BW, Arend R, et al. (2007). Predictor and moderator effects in the treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(5), 462–472. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Chadi N, & Shrier L (2019). Mindfulness-based interventions for adolescent health. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 37(4), 469–475. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorah J (2018). Effect size measures for multilevel models: Definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-scale Assessment in Education, 6. 10.1186/s40536-018-0061-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, & Lovejoy MC (2006). A meta-analysis of parent training: moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 86–104. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliken AC, & Katz LF (2013). Exploring the impact of parental psychopathology and emotion regulation on evidence-based parenting interventions: a transdiagnostic approach to improving treatment effectiveness. Clininical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(2), 173–186. 10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 174–186. 10.1111/jar.12064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, & Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems a transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. 10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasley K, & Gecas V (1984). Stresses and satisfactions of the parental role. Journal of Counseling & Development, 62(1), 400–404. 10.1111/j.2164-4918.1984.tb00236.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parent J, McKee LG, J NR, & Forehand R (2016). The Association of Parent Mindfulness with Parenting and Youth Psychopathology Across Three Developmental Stages. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(1), 191–202. 10.1007/s10802-015-9978-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, & Brook J (1999). Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: moodiness or mood disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(1), 133–135. 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, & Seeman TE (2002). Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11931522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR & Richmond BO (1997). Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EB, David SL, & Rao SA (2003). Preventing drug use among children and adolescents: A research-based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, & Teasdale JD (2002). Mindfidness-basedcognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shelleby EC, & Shaw DS (2014). Outcomes of parenting interventions for child conduct problems: a review of differential effectiveness. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(5), 628–645. 10.1007/s10578-013-0431-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheras PR, Abidin RR, & Konold TR (1998) Stress Index for Parents of Adolescents. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Singh NN, Singh AN, Lancioni GE, Singh J, Winton ASW, & Adkins AD (2010). Mindfulness training for parents and their children with ADHD increases the children’s compliance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 157–166. 10.1007/sl0826-009-9272-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Redmond C, & Shin C (2001). Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 627–642. 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2001). We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1–19. 10.1111/1532-7795.00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C, & Dreessen L (2004). Assessing depression in youth: relation between the Children's Depression Inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinican Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 149–157. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpyn CC, & Chaplin TM (2016). Mindful Parenting and Parents' Emotion Expression: Effects on Adolescent Risk Behaviors. Mindfulness (N Y), 7(1), 246–254. 10.1007/s12671-015-0440-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, Mastroleo NR, et al. (2009). A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(4), 555–567. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, & Hammond M (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 283–302. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, Smith GT, Giedd J, & Dahl RE (2008). Transitions into underage and problem drinking: developmental processes and mechanisms between 10 and 15 years of age. Pediatrics, 121 Suppl 4, S273–289. 10.1542/peds.2007-2243C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.