Abstract

We report on the electrical transport properties of Nb based Josephson junctions with Pt/CoB/Pt ferromagnetic barriers. The barriers exhibit perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, which has the main advantage for potential applications over magnetisation in-plane systems of not affecting the Fraunhofer response of the junction. In addition, we report that there is no magnetic dead layer at the Pt/CoB interfaces, allowing us to study barriers with ultra-thin CoB. In the junctions, we observe that the magnitude of the critical current oscillates with increasing thickness of the CoB strong ferromagnetic alloy layer. The oscillations are attributed to the ground state phase difference across the junctions being modified from zero to . The multiple oscillations in the thickness range nm suggests that we have access to the first zero- and -zero phase transitions. Our results fuel the development of low-temperature memory devices based on ferromagnetic Josephson junctions.

Subject terms: Spintronics, Superconducting properties and materials, Magnetic devices, Superconducting devices, Magnetic properties and materials

Introduction

Proximity effects between superconducting (S) and ferromagnetic (F) materials are a topic of intense research effort due to the new physics at S–F interfaces1–6. In S–F–S Josephson junctions, it is well established that the ground-state phase difference across the junction can be tuned from zero to , depending on the F layer thickness1. Experimentally, the zero- transitions correspond to oscillations in the junction’s characteristic voltage, , with increasing F layer thickness7. To date, experimental demonstrations of -junctions include: the weak ferromagnetic alloys CuNi8–14, PdNi15,16 and PdFe17, the ferromagnetic elements Ni18–26, Co20–22,27 and Fe20,21,28, and the strong ferromagnetic alloys NiFe20–22,29–32, NiAl33, NiFeMo34 and NiFeCo31.

In general, most previous works measure Josephson junctions with F layers having in-plane magnetisation. When the magnetisation is in-plane, the F layer can contribute significant magnetic flux density in the junction, modifying the response of the junction to an externally applied measurement field and shifting the maximum critical current away from . In addition, when applying an in-plane field to measure the junction, the F layer may switch in the measurement field. Josephson junctions containing perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (PMA) F layers have advantages over in-plane systems as, in principle, the magnetisation and magnetic switching of layers in the junction should not affect the in-plane magnetic flux. The application of an in-plane measurement field will tilt the magnetisation of the PMA layer slightly, however the field required to fully saturate the PMA layers considered in this work is far larger than the field required to characterise the junctions, so the tilting effect can be neglected.

Of the previous F layers characterised, only CuNi and PdNi have an intrinsic PMA component of their magnetisation. An alternative to intrinsic PMA is interfacial PMA, which can give a F layer an overall PMA so long as the F layer is thin enough that the interfacial anisotropy dominates over the bulk anisotropy. Josephson junctions containing interfacial PMA F layers have been previously studied theoretically35–37 and experimentally in the context of spin-triplet supercurrents, however, no zero- oscillations were expected or observed in the particular geometries studied38–41.

In this work, we study the amorphous strong ferromagnetic alloy CoB42. For many spintronic applications, the amorphous Co based alloys are advantageous over crystalline Co due to their lack of crystalline anisotropy and weaker pinning of magnetic domain walls due to the reduced density of grain boundaries43. Recently, thin film CoB has been studied for magnetic memory application and as a host of magnetic skyrmions44–46. When placed adjacent to Pt layers, the Pt/CoB interfaces exhibit PMA, giving an overall PMA for the thin layers considered in this work. Previously, we used CoB in PMA pseudospin-valve junctions, where the critical current of the junction could be controlled by the relative orientation of two ferromagnets in the Pt/Co/Pt/CoB/Pt barrier47. For application in cryogenic memory, it is important to demonstrate that in addition to modulating the critical current of such devices, it is also possible to switch such devices from the zero to state48–51. For this, the zero– critical current oscillations of the component ferromagnets in the pseudospin-valve should be well characterised. In this work, we present evidence of such zero– critical current oscillations in Pt/CoB/Pt junctions.

Results

Magnetic characterisation

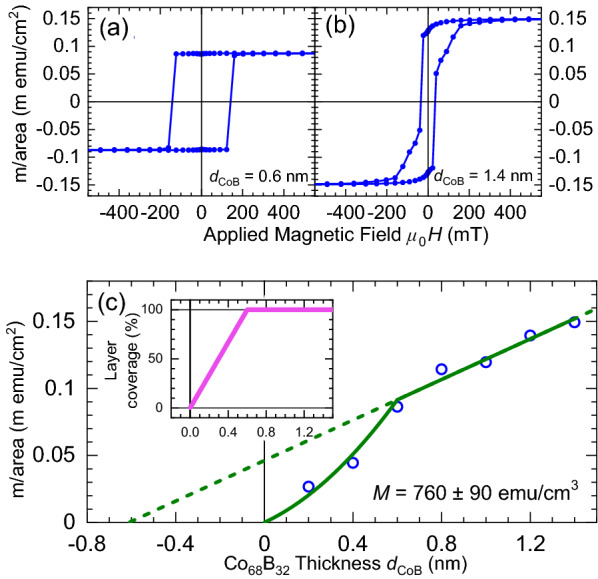

Magnetic moment per area versus out-of-plane field data are shown in Fig. 1a,b for S-Pt(10)-CoB(d)-Pt(5)-S sheet film samples at 10 K with a nominal thickness (a) d nm and (b) d nm. For d nm, the square hysteresis loop indicates a strong PMA. As the nominal thickness of the CoB is increased towards the largest thickness studied in this work, d nm Fig. 1b, we observe two changing characteristics in the hysteresis loops. Firstly, the coercive field reduces. Secondly, the squareness ratio of the loop reduces - indicating competing anisotropies in the CoB layer. Upon making the CoB thicker, we would expect that the anisotropy of the layer will change from being predominately PMA to predominately in-plane.

Figure 1.

Magnetic characterisation of the sheet film samples S-Pt(10)-CoB(d)-Pt(5)-S. (a,b) Magnetic hysteresis loops of the magnetic moment (m) per area acquired at a temperature of 10 K with the applied field oriented out-of-plane for (a) d nm and (b) d nm. The diamagnetic contribution from the substrate has been subtracted. (c) Collated saturation moment per area versus nominal thickness of CoB. To model the lower m/area of the thinnest samples in the study, we construct a partial layer coverage model detailed in the text and shown in the inset. The result of fitting the model over the entire data range is shown by the solid line. The extracted magnetisation emu/cm. The dashed line shows an extrapolation of the linear part of the model to the intercepts. Values of m/area are calculated from the measured total magnetic moments and areas of the samples. The uncertainty in each point is dominated by the area measurements, and is less than 5%.

Saturation magnetic moment per area versus nominal thickness of the CoB(d) at 10 K are shown in Fig. 1c. These data are best described in two regimes. For the thicker samples in this study, we observe the expected linear dependence with increasing thickness of ferromagnet. The thinnest two samples in this study deviate from this linear trend, showing a lower moment/area than implied by the trend in the thicker samples.

In order to apply a fitting model which describes the entire data set, we construct a partial layer coverage toy model of our system. The basis of the model is the assumption that the F-layers in the thinnest samples may not be continuous. From zero thickness to some critical thickness, we assume that the layer coverage increases linearly by the profile shown in Fig. 1c inset. The physical picture implied by this model is consistent with island nucleation, coalescence followed by layered growth – which is not an atypical growth mode for ambient temperature sputtered thin films. Above the critical thickness, we assume that the layer is now continuous, so the data can be described by the expected linear trend. More information on the model and extracting magnetisation from moment/area data are included in the Supplementary Information along with alternative fitting models to the data presented in Fig. 1c (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online).

The result of our toy model is shown by the solid line in Fig. 1c. The toy model gives a critical thickness for layer growth of nm, which is comparable to a couple of unit cells of nominal thickness, and gives the magnetisation of the CoB to be emu/cm, consistent with the expected bulk magnetisation of 730 emu/cm52. The model also includes a contribution to the total magnetic signal from the polarisation of the adjacent Pt layer, this is commonly observed in such systems53–57. In Figure 1 (c), the polarised Pt contribution can be extracted from the y-intercept of the dashed line, which is an extrapolation of the linear part of the model. The magnetic contribution to the total magnetic response of the sample by the polarised Pt is emu/cm, or emu/cm per Pt/CoB interface, consistent with Suzuki et al.55.

It has been reported elsewhere that significant magnetic dead layers can form in ferromagnetic Josephson junction barriers at the Nb/F interfaces, see for example21, however adding buffer layers such as Rh, Cu or Pt can significantly improve the morphology of the F layer27,41,58,59. The signature of magnetic dead layers is a positive x-intercept when plotting moment/area versus thickness. In our Pt/CoB/Pt barriers, the x-intercept when fitting to Fig. 1c is not positive (regardless of the model used, see Supplementary Fig. S1 online), suggesting that such dead layers have been minimised by the Pt interfaces. Additionally, when the nominal thickness of the CoB is equivalent to only one or two monolayers, and so the layer is modelled with partial coverage, the polarised Pt appears to have stabilised the magnetisation of what we expect are islands of CoB, allowing us to measure a magnetic response even for d nm, a significant advantage of our approach.

Electrical transport

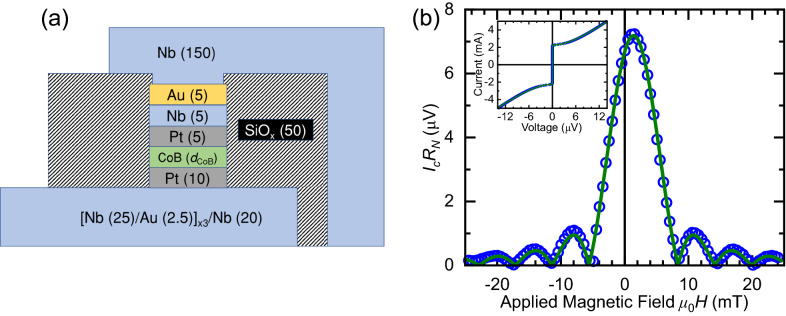

Samples were fabricated using standard lithography techniques into circular current perpendicular-to-plane Josephson junction devices, as depicted schematically in Fig. 2a. We load the devices into our cryostat at room temperature and first cool to 15 K, just above the superconducting transition (9 K), where we apply a 1 T out-of-plane saturating field. Once the saturating field is removed, we rotate the sample so the field is applied in-plane and cool the samples to the base temperature of our cryostat, 1.8 K. We measure the I–V characteristic of each junction as a function of in-plane applied magnetic field between mT to determine the Fraunhofer pattern. The field necessary to saturate our Pt/CoB/Pt barriers is in excess of 1 T so the maximum deviation of the magnetisation from the perpendicular is less than 1.5.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic cross section of the S-F-S Josephson junction device (not to scale). The thickness of each layer is given in nanometers. The CoB layer thickness, d, is ranged from 0.2 to 1.4 nm. (b) Product of critical Josephson current times normal-state resistance versus applied magnetic field for the device depicted in (a) with d nm at 1.8 K. is determined from the measured I–V characteristic at each field value and is the average normal state resistance across all measured fields. The uncertainty in determining is smaller than the data points. The data are fit with Eqs. (2) and (3). Inset: The I–V characteristic at zero applied field with fit to Eq. (1).

The I–V characteristics of our devices follow the standard square-root form expected for over-damped Josephson junctions60,

| 1 |

where is the critical Josephson current and is the normal state resistance of the junction. For circular Josephson junctions, the (B) Fraunhofer response can be described by the Airy function60,

| 2 |

where is the maximum critical current, is a Bessel function of the first kind, is the flux quantum, and is the flux through the junction60,

| 3 |

where w, , , and d are the width of the junction, the London penetration depth, the thickness of the superconducting electrode, and the total thickness of all the normal metal layers and F layers in the junction, respectively. The bottom electrode is a Nb/Au multilayer ( = 190 nm61) and the top electrode is single layer Nb ( = 150 nm62). is the applied field and is the amount is shifted from H = 0. arises from a combination of an intrinsic contribution due to any in-plane magnetisation of the junction, and extrinsic artifacts from trapped flux in the 3 superconducting coil used to perform the measurements. Fits to these equations are shown along with the data on a typical device in Fig. 2b. We attribute the small in Fig. 2b to trapped flux in our superconducting coil, which is supported by additional Fraunhofer data for both +1 T and -1 T saturation fields (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online). We determine for many samples of different CoB thicknesses (d) following the same protocol.

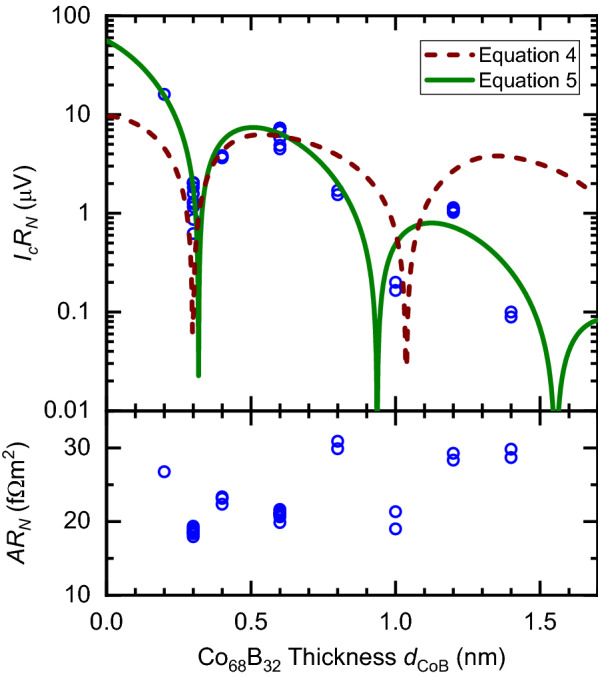

Figure 3 shows the collated and (area times normal-state resistance) products for the Josephson junctions measured in this study. corresponds to the maximum of the (B) Fraunhofer response and is the average resistance from measurements at all field values. As the thickness of the CoB is increased, the shows nonmonotonic behaviour. When plotting , we fix A by the nominal design dimension. The product for our samples is suggestive that within the same chip the junction-to-junction reproducibility is very good, which is also supported by the small spread of values for junctions on the same chip. It is possible to determine A by fitting (B) to Eqs. (2) and (3), and we find that across all our junctions the extracted average m is consistent with the lithography design. The scatter in is therefore similar to the scatter in the linear dimensions of the junctions. Variations in A between samples will not affect the reported , which is a size independent quantity. Indeed, there is no correlation between a high/low and .

Figure 3.

Top: Product of critical Josephson current times normal-state resistance versus nominal CoB thickness for ferromagnetic Josephson junctions of the form S-Pt(10)-CoB(d)-Pt(5)-S at 1.8 K. Each data point represents one Josephson junction and the uncertainty in determining is smaller than the data points. The data are fit to Eqs. (4) and (5). The best fit parameters for Eq. (4) corresponds to nm, and for Eq. (5) to nm and nm. The first minimum at nm indicates a transition between the zero and -phase states. Bottom: Product of the area times normal-state resistance for the same junctions. The scatter in is most likely sample-to-sample variation in A.

We report strong reproduciblity of our results, as multiple samples for and 0.6 nm are grown and fabricated in independent cycles and show consistency in , Fig. 3. Scatter in is most likely driven by sample-to-sample variations in the thickness of the CoB.

Coherence lengths in S/F/S Josephson junctions

The transport properties of S–F–S Josephson junctions are well described in three limits, driven by the relative magnitude of three lengthscales; the mean free path (), the superconducting coherence length () and the effective coherence length inside the ferromagnet (). In the ballistic limit , in the intermediate limit , and in the diffusive limit .

In the ballistic limit, the decay and oscillations of is given by the numerical maximum with respect to of the ballistic limit supercurrent 7,

| 4 |

where is the phase difference across the junction, is the energy gap, T is the temperature, and . In the ballistic limit, , where is the Fermi velocity and is the exchange energy. Ballistic limit transport has been reported in the ferromagnetic elements when sufficiently thin, for example in Ni barriers studied by Robinson et al.20 and Baek et al.25.

In the intermediate limit, the decay and oscillations of is given by63,

| 5 |

where is the thickness of the first zero– transition, and are the lengthscales governing the decay and oscillation of , respectively. In the intermediate limit, one finds . Most ferromagnetic alloys studied in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions are solid-solutions with short mean free paths and are found to be best described in the intermediate limit17,31, for example PdNi barriers studied by Khaire et al.16.

It is well established that Rashba effects arising from spin-orbit coupling can be found at the interface between metallic ferromagnets, such as Co, and heavy metals, such as Pt64–66 and so in the diffusive limit with spin-flip or spin-orbit scattering, the transport may be described by Eq. (5)67. However in the diffusive limit one will find 67,68. In experimental literature, this situation is somewhat rarer, for example CuNi barriers studied by Oboznov et al.10 and NiFeMo barriers studied by Niedzielski et al.34.

Fitting to our results taking and as fitting parameters (shown in Fig. 3), we find that Eq. (4) does not reproduce our CoB data as well as Eq. (5), particularly for larger . The fits for Eq. (5) correspond to the limit , placing our junctions in the intermediate limit. The best fit parameters are given in Table 1, which also includes results from other ferromagnetic alloys best described by Eq. (5). For further analysis on our data see Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4 online.

Table 1.

Best fit parameters determined for selected Josephson junctions where the F layers are ferromagnetic alloys and the oscillations are well described by Eq. (5).

Discussion

Systems, such as ours, with a source of s-wave superconductivity, large spin-orbit coupling, and ferromagnetism are predicted to display transport properties consistent with spin-triplet supercurrents69, reported to be observed in ferromagnetic resonance measurements70. In this work, however, within the resolution of our measurements, the data are well described by singlet transport physics alone and we do not need to invoke a significant spin-triplet supercurrent to explain our results – for further details see the Supplementary Information online. The lack of evidence for spin-triplet supercurrents in these Josephson junctions is consistent with previous works41,59.

In comparison to other ferromagnetic alloys, such as those in Table 1, our CoB junctions display significantly shorter and characteristic lengthscales. We attribute the short to the common property of amorphous alloys having a short due to structural disorder, however scattering at the Pt/CoB interfaces may also be considerable for very thin F layers. The advantage of the short in our system is that we have access to the first zero- and -zero transitions before the F layer undergoes the reorientation transition to in-plane magnetisation. Despite the short , the extrapolated at zero thickness for our junctions, V, is comparable to NiFe junctions, V31, which have been extensively studied for similar applications20–22,29–32,48–51. In addition, the product at the peak of the first state, V, is comparable to other ferromagnetic alloys, for example V in NiFeCo and V in NiFe31. The disadvantage of the short for application is that precise control over thickness is necessary, since small variations will cause large changes to the product and could potentially change the phase difference across the junction. Fortunately, such PMA multilayer stacks have an established industrial process for applications in magnetic recording.

The key application of ferromagnetic Josephson junctions is Josephson magnetic RAM (JMRAM)71. In this technology, the CoB forms one layer in a pseudospin-valve Josephson junction of the general type reported in our previous publication where we used Co and CoB47. In order to use the pseudospin-valve for JMRAM, the component ferromagnetic layers must be well characterised, as we report here for Pt/CoB/Pt PMA trilayers. In JMRAM, the zero- ferromagnetic junction is a passive phase shifter in a SQUID loop containing two S/I/S junctions. As the zero- junction is passive, there is no need for this junction to have a large , however as we demonstrate our CoB has comparable performance in this regard to NiFe, which is used in state-of-the-art devices. A JMRAM memory cell with in-plane ferromagnets (NiFe and Ni) was recently demonstrated by Dayton et al.50.

The detrimental features of magnetisation in-plane junctions are driven by the interaction between the physics underlying the Fraunhofer response and the vector potential of the ferromagnet. For in-plane single domain junctions, the Fraunhofer pattern will be uniformly shifted from zero global applied field by the vector potential of the ferromagnet in the plane of the junction. For example, Glick et al. characterise candidate in-plane F layers31, where the Fraunhofer patterns are uniformly shifted by . To ensure that the F layers are single domain, the maximum junction area in that work is m. If the area of the junctions is increased so that the ferromagnet becomes multidomain, it may not be possible to recover a Fraunhofer pattern due to the distortion by the stray fields emanating from the domains16,58,72. Such size considerations place an upper limit on the critical current of devices. Finally, the in-plane measurement field required to characterise the Fraunhofer pattern can cause premature switching of in-plane ferromagnets. Combined, the shift and premature switching means that JMRAM devices with in-plane ferromagnets may not have access to the highest critical current state, as observed for in-plane pseudospin-valve devices by Niedzielski et al.32.

In contrast, the use of PMA ferromagnets as we have demonstrated offers solutions to the issues introduced by in-plane ferromagnets. As the direction of the magnetisation and stray fields of PMA layers are parallel to the direction of current in the junction, they do not shift or distort the Fraunhofer pattern. Furthermore, due to the favourable demagnetisation effects, PMA materials systems have less stray fields and larger domain size limits compared to in-plane systems. Combined, these advantages allow us to successfully measure well defined Fraunhofer patterns on junctions with an area of m, much larger than those Glick et al. require to characterise in-plane layers. As a result of the PMA, the highest critical current state of the junction is available at zero global applied field, as demonstrated in Fig. 2b. Finally, the application of in-plane measurement fields will not switch a PMA ferromagnet.

For practicable memory devices, it will be important to remove the need for an applied out-of-plane switching field. Such a field to switch a PMA ferromagnet may introduce flux vortices into the superconducting Nb electrodes, which we negated in this work by applying such fields only above . Routes towards removing this restriction by implementing an all electrical switching process include spin-transfer torque and spin-orbit torque switching of the barriers65,66,73.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate Josephson -junctions with Pt/CoB/Pt perpendicular magnetic anisotropy barriers. CoB is a strong ferromagnetic amorphous alloy of interest in spintronics due to its low pinning properties. We show that at the Pt/CoB interfaces there is significant polarisation of the Pt and that the samples are magnetic down to a nominal CoB thickness of 0.2 nm. In Josephson junctions, as the thickness of CoB is increased, we observe the nonmonotonic decay and oscillation of the critical Josephson current. These oscillations are attributed to the junctions undergoing the zero to transition. -junctions have important applications in superconducting electronics, including cryogenic memory. Systematic material studies are crucial for the development of such technologies. The performance of our perpendicular magnetic anisotropy -junctions are at least comparable to that of NiFe, which has in-plane magnetisation.

Methods

Samples are deposited, fabricated, and measured using identical methodology to our previous work47. The final product of cleanroom processing are standard “sandwich” planar Josephson junctions, defined by photolithography and Ar ion milling, where the current flows perpendicular to the plane. The diameter of the circular junctions is a design parameter and is nominally m.

We dc sputter deposit the multilayer samples onto thermally oxidised Si substrates in the Royce Deposition System74. The magnetrons are mounted below, and confocal to, the substrate with source-substrate distances of 134 mm. The base pressure of the vacuum chamber is 110. The samples are deposited at room temperature with an Ar (6N purity) gas pressure of 3.610 for the [Nb/Au]/Nb bottom electrode layers and 4.810 for the Pt/CoB/Pt barrier layers. The [Nb/Au]/Nb superlattice is used for the bottom electrode as the superlattice has a lower surface roughness compared to a single Nb layer of comparable total thickness61,75. Finally, a Nb/Au cap is deposited to prevent oxidation during the processing. In the final stage of sample fabrication, the top electrode, 150 nm of Nb, is deposited after an in-situ ion milling process to remove 5 nm from the 10 nm Au cap. The full structure of the final device with thickness in (nm) is [Nb (25)/Au(2.5)]/Nb (20)/Pt (10)/CoB (d)/ Pt (5)/Nb (5)/Au (5)/ Nb (150).

The choice of Pt thicknesses in this study is informed by previous results41, being a balance between developing a suitable textured surface on which to grow the CoB layer whilst not being in a range that significantly affects the critical current density. The total thickness of the Pt in this work is the same as that required for pseudospin-valve devices47.

Fabricated devices are measured in a continuous flow cryostat with 3 horizontal superconducting Helmholtz coils. The sample can be rotated about the vertical axis, which we perform in increments of to bring that field in- and out-of-plane of the junctions. In order to avoid trapping flux in the superconducting Nb layers in the devices, we performed all sample rotations in zero field above the of the Nb and always cooled the sample in zero applied field (in practice there will inevitably be a small remanent field due to trapped flux in the magnet). The full sequence of setting the magnetic state of our samples and performing the measurement field sweeps is: warm to 15K, rotate sample to apply field out-of-plane, apply saturating field, remove saturating field, rotate sample by , cool sample, apply field in-plane, measure. Once we have finished measuring that magnetic state of the sample, we may wish to measure a further condition, such as reversing the magnetisation. To do so, we remove the in-plane field, warm to 15K and repeat the cycle described above.

Traditional 4-point-probe transport geometry is used to measure the current-voltage characteristic of the junction with combined Keithley 6221-2182A current source and nano-voltmeter. Magnetisation loops of sheet films are measured using a Quantum Design MPMS 3 magnetometer.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Norman Birge for advice and helpful discussions, M. Vaughan, J. Massey, M. Rogers, T. Moorsom, M. Ali, M. Rosamond, and L. Chen for experimental assistance. We acknowledge support from the Henry Royce Institute. The work was supported financially through the following EPSRC grants: EP/M000923/1, EP/P022464/1 and EP/R00661X/1. This project has received funding from the European Unions Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 743791 (SUPERSPIN).

Author contributions

N.S. and G.B. conceived and designed the experiment. N.S., P.M.S., E.D., B.J.H. and G.B. undertook the materials development including optimisation and characterisation of the growth process. N.S., T.M. and G.B. undertook the low temperature transport and magnetometry measurements and analysed the data. N.S. undertook the sample fabrication and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the University of Leeds repository, https://doi.org/10.5518/817.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-90432-y.

References

- 1.Buzdin AI. Proximity effects in superconductor-ferromagnet heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005;77:935–976. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.77.935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeret FS, Volkov AF, Efetov KB. Odd triplet superconductivity and related phenomena in superconductor-ferromagnet structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005;77:1321–1373. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.77.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eschrig M. Spin-polarized supercurrents for spintronics. Phys. Today. 2011;64:43–49. doi: 10.1063/1.3541944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linder J, Robinson JWA. Superconducting spintronics. Nat. Phys. 2015;11:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nphys3242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eschrig M. Spin-polarized supercurrents for spintronics: a review of current progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015;78:104501. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/78/10/104501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birge NO. Spin-triplet supercurrents in Josephson junctions containing strong ferromagnetic materials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2018;376:20150150. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzdin AI, Bulaevskii LN, Panyukov SV. Critical-current oscillations as a function of the exchange field and thickness of the ferromagnetic metal (F) in an SFS Josephson junction. JETP Lett. 1982;35:178–180. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryazanov VV, et al. Coupling of Two Superconductors through a Ferromagnet: evidence for a Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;86:2427–2430. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sellier H, Baraduc C, Lefloch F, Calemczuk R. Temperature-induced crossover between and states in S/F/S junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2003;68:054531. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.68.054531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oboznov VA, Bol’ginov VV, Feofanov AK, Ryazanov VV, Buzdin AI. Thickness dependence of the Josephson ground states of superconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:197003. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.197003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weides M, et al. Josephson tunnel junctions with ferromagnetic barrier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:247001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.247001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weides M, et al. High quality ferromagnetic 0 and Josephson tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:122511. doi: 10.1063/1.2356104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoutimore MJA, et al. Second-harmonic current-phase relation in Josephson junctions with ferromagnetic barriers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;121:177702. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.177702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolginov VV, Rossolenko AN, Shkarin AB, Oboznov VA, Ryazanov VV. Fabrication of Optimized superconducting phase inverters based on superconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor -junctions. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2018;190:302–314. doi: 10.1007/s10909-017-1843-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kontos T, et al. Josephson junction through a thin ferromagnetic layer: negative coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:137007. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.137007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khaire TS, Pratt WP, Birge NO. Critical current behavior in Josephson junctions with the weak ferromagnet PdNi. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;79:094523. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.79.094523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glick JA, Loloee R, Pratt WP, Birge NO. Critical current oscillations of Josephson junctions containing PdFe nanomagnets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017;27:1–5. doi: 10.1109/TASC.2016.2630024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blum Y, Tsukernik A, Karpovski M, Palevski A. Oscillations of the superconducting critical current in Nb-Cu-Ni-Cu-Nb junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:187004. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.187004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shelukhin V, et al. Observation of periodic -phase shifts in ferromagnet-superconductor multilayers. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:174506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.174506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JWA, Piano S, Burnell G, Bell C, Blamire MG. Critical current oscillations in strong ferromagnetic junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:177003. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.177003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson JWA, Piano S, Burnell G, Bell C, Blamire MG. Zero to transition in superconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76:094522. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.76.094522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson JWA, Piano S, Burnell G, Bell C, Blamire MG. Transport and magnetic properties of strong ferromagnetic pi-junctions. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007;17:641–644. doi: 10.1109/TASC.2007.898720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bannykh AA, et al. Josephson tunnel junctions with a strong ferromagnetic interlayer. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;79:054501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.79.054501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baek B, Rippard WH, Benz SP, Russek SE, Dresselhaus PD. Hybrid superconducting-magnetic memory device using competing order parameters. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3888. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baek B, Schneider ML, Pufall MR, Rippard WH. Phase offsets in the critical-current oscillations of Josephson junctions based on Ni and Ni-( barriers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2017;7:064013. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.7.064013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baek B, Schneider ML, Pufall MR, Rippard WH. Anomalous supercurrent modulation in Josephson junctions with Ni-based barriers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018;28:1–5. doi: 10.1109/TASC.2018.2836961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JWA, Barber ZH, Blamire MG. Strong ferromagnetic Josephson devices with optimized magnetism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;95:192509. doi: 10.1063/1.3262969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piano S, Robinson JWA, Burnell G, Blamire MG. 0- oscillations in nanostructured Nb/Fe/Nb Josephson junctions. Eur. Phys. J. B. 2007;58:123–126. doi: 10.1140/epjb/e2007-00210-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell C, Loloee R, Burnell G, Blamire MG. Characteristics of strong ferromagnetic Josephson junctions with epitaxial barriers. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;71:180501(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.180501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abd El Qader M, et al. Switching at small magnetic fields in Josephson junctions fabricated with ferromagnetic barrier layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014;104:022602. doi: 10.1063/1.4862195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glick JA, et al. Critical current oscillations of elliptical Josephson junctions with single-domain ferromagnetic layers. J. Appl. Phys. 2017;122:133906. doi: 10.1063/1.4989392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niedzielski BM, et al. Spin-valve Josephson junctions for cryogenic memory. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:024517. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.024517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Born F, et al. Multiple transitions in superconductor/insulator/ferromagnet/superconductor Josephson tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;74:140501(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.74.140501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niedzielski BM, Gingrich EC, Loloee R, Pratt WP, Birge NO. S/F/S Josephson junctions with single-domain ferromagnets for memory applications. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2015;28:085012. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/28/8/085012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margaris I, Paltoglou V, Flytzanis N. Zero phase difference supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2010;22:445701. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/44/445701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halterman K, Valls OT, Wu C-T. Charge and spin currents in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;92:174516. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.92.174516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silaev MA, Tokatly IV, Bergeret FS. Anomalous current in diffusive ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;95:184508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.184508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gingrich EC, et al. Spin-triplet supercurrent in Co/Ni multilayer Josephson junctions with perpendicular anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;86:224506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.224506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glick JA, et al. Spin-triplet supercurrent in Josephson junctions containing a synthetic antiferromagnet with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B. 2017;96:224515. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.224515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glick JA, et al. Phase control in a spin-triplet SQUID. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaat9457. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satchell N, Loloee R, Birge NO. Supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions with heavy-metal interlayers. II. Canted magnetization. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;99:174519. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.99.174519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka H, et al. Electronic structure and magnetism of amorphous CoB alloys. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:2671–2677. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavrijsen R, et al. Reduced domain wall pinning in ultrathin Pt/CoB/Pt with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;96:022501. doi: 10.1063/1.3280373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schellekens AJ, Van den Brink A, Franken JH, Swagten HJM, Koopmans B. Electric-field control of domain wall motion in perpendicularly magnetized materials. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:847. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finizio S, et al. Deterministic field-free Skyrmion nucleation at a nanoengineered injector device. Nano Lett. 2019;19:7246–7255. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeissler K, et al. Diameter-independent skyrmion Hall angle observed in chiral magnetic multilayers. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:428. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14232-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satchell N, et al. Spin-valve Josephson junctions with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy for cryogenic memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020;116:022601. doi: 10.1063/1.5140095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bell C, et al. Controllable Josephson current through a pseudospin-valve structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84:1153–1155. doi: 10.1063/1.1646217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gingrich EC, et al. Controllable 0- Josephson junctions containing a ferromagnetic spin valve. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:564. doi: 10.1038/nphys3681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dayton IM, et al. Experimental demonstration of a Josephson magnetic memory cell with a programmable -junction. IEEE Magn. Lett. 2018;9:3301905. doi: 10.1109/LMAG.2018.2801820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Madden AE, Willard JC, Loloee R, Birge NO. Phase controllable Josephson junctions for cryogenic memory. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2018;32:015001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6668/aae8cf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Konc̆ M, et al. Temperature dependence of the magnetization and of the other physical properties of rapidly quenched amorphous CoB alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1994;30:524–526. doi: 10.1109/20.312324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schütz G, et al. Spin-dependent X-ray absorption in Co/Pt multilayers and CoPt alloy. J. Appl. Phys. 1990;67:4456–4458. doi: 10.1063/1.344903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geissler J, et al. Pt magnetization profile in a Pt/Co bilayer studied by resonant magnetic X-ray reflectometry. Phys. Rev. B. 2001;65:020405(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.020405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suzuki M, et al. Depth profile of spin and orbital magnetic moments in a subnanometer Pt film on Co. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;72:054430. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.72.054430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowan-Robinson RM, et al. The interfacial nature of proximity-induced magnetism and the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction at the Pt/Co interface. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16835. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17137-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inyang O, et al. Threshold interface magnetization required to induce magnetic proximity effect. Phys. Rev. B. 2019;100:174418. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.100.174418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khasawneh MA, Pratt WP, Birge NO. Josephson junctions with a synthetic antiferromagnetic interlayer. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:020506(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.020506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Satchell N, Birge NO. Supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions with heavy metal interlayers. Phys. Rev. B. 2018;97:214509. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.214509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barone A, Paternò G. Physics and Applications of the Josephson Effect. Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quarterman P, et al. Distortions to the penetration depth and coherence length of superconductor/normal-metal superlattices. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020;4:074801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.4.074801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flokstra MG, et al. Observation of Anomalous Meissner Screening in Cu/Nb and Cu/Nb/Co Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018;120:247001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.247001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bergeret FS, Volkov AF, Efetov KB. Josephson current in superconductor-ferromagnet structures with a nonhomogeneous magnetization. Phys. Rev. B. 2001;64:134506. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.64.134506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krupin O, et al. Rashba effect at magnetic metal surfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2005;71:201403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.201403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miron IM, et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nmat2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miron IM, et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature. 2011;476:189. doi: 10.1038/nature10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fauré M, Buzdin AI, Golubov AA, Kupriyanov MY. Properties of superconductor/ferromagnet structures with spin-dependent scattering. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73:064505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.064505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pugach NG, Kupriyanov MY, Goldobin E, Kleiner R, Koelle D. Superconductor-insulator-ferromagnet-superconductor Josephson junction: from the dirty to the clean limit. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:144513. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.144513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergeret FS, Tokatly IV. Spin-orbit coupling as a source of long-range triplet proximity effect in superconductor-ferromagnet hybrid structures. Phys. Rev. B. 2014;89:134517. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.134517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jeon K-R, et al. Enhanced spin pumping into superconductors provides evidence for superconducting pure spin currents. Nat. Mater. 2018;17:499–503. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herr, A. Y. & Herr, Q. P. Josephson magnetic random access memory system and method (2012). US Patent 8 270 209.

- 72.Bourgeois O, et al. Josephson effect through a ferromagnetic layer. Eur. Phys. J. B. 2001;21:75–80. doi: 10.1007/s100510170215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baek B, et al. Spin-transfer torque switching in nanopillar superconducting-magnetic hybrid Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2015;3:011001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.3.011001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The Royce Deposition System is a multi-chamber, multi-technique thin film deposition tool based at the University of Leeds as part of the Henry Royce Institute.

- 75.Wang Y, Pratt WP, Birge NO. Area-dependence of spin-triplet supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B. 2012;85:214522. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.214522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the University of Leeds repository, https://doi.org/10.5518/817.