Abstract

Background

Parental separation has been associated with adverse child mental health outcomes in the literature. For school-aged children, joint physical custody (JPC), that is, spending equal time in both parents’ homes after a divorce, has been associated with better health and well-being than single care arrangements. Preschool children’s well-being in JPC is less studied. The aim of this study was to investigate the association of living arrangements and coparenting quality with mental health in preschool children after parental separation.

Methods

This cross-sectional population-based study includes 12 845 three-year-old children in Sweden. Mental health was measured by parental reports of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire and coparenting quality with a four-item scale. The living arrangements of the 642 children in non-intact families were categorised into JPC, living mostly with one parent and living only with one parent.

Results

Linear regression models, adjusted for sociodemographic confounders, showed an association between increased mental health problems and living mostly and only with one parent (B=1.18; 95% CI 0.37 to 2.00, and B=1.20; 95% CI 0.40 to 2.00, respectively), while children in intact families vs JPC did not differ significantly (B=−0.11; 95% CI −0.58 to 0.36). After adjusting the analyses for coparenting quality, differences in child mental health between the post divorce living arrangements were, however, minimal while children in intact families had more mental health problems compared with JPC (B=0.70; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.15). Factorial analysis of covariance revealed that low coparenting quality was more strongly related to mental health problems for children in intact families and JPC compared with children living mostly or only with one parent.

Conclusions

This study suggests that coparenting quality is a key determinant of mental health in preschool children and thus should be targeted in preventive interventions.

Keywords: child psychology, comm child health

What is known about the subject?

Parental separation is a common experience for children in high-income countries.

Joint physical custody, where children share their time about equally between their parents’ homes, has become an increasingly common living arrangement after parental separation.

There is a dearth of empirical studies on child mental health in joint physical custody in the preschool age.

What this study adds?

We found similar mental health in 3 year-old children in joint physical custody and intact families, while children living only and mostly with one parent had more mental health problems, net of sociodemographic characteristics.

Once we accounted for coparenting quality, child mental health in the diverse living arrangements after parental divorce was very similar.

Our results imply that coparenting is of major importance for understanding mental health problems that emerge early in life, and could be targeted with interventions in families with young children.

Introduction

Around 35% of Swedish children experience parental separation before reaching the age of 18 years, and previous studies have shown that the experience of parental separation is associated with adverse mental health outcomes in the short as well as the long term.1 2 During recent decades, parenting norms have changed in the Nordic countries, and sole custody among mothers has become less common than joint physical custody (JPC), where children share their time about equally between their parents’ respective homes.3–5 In Sweden, approximately 10% of all school children live in JPC arrangements.3 JPC is also increasingly common even in countries with more conservative family values such as Germany and France.6 7

Living arrangements and child well-being

A growing body of research has shown that living arrangements and contact with both parents is associated with postdivorce child well-being.8 Most studies in the literature have suggested that school-aged children and adolescents in JPC fare better on several outcomes compared with children in single-parent arrangements.9 10 JPC arrangements among preschool children has been much less studied. In a recent Swedish study,11 3–5 years old who lived in JPC had fewer mental health problems compared with those living in single-parent arrangements. Similar findings were reported in a Nordic study on children aged 2–9 years.12 Studies in contexts outside of the Nordic countries have shown similar but somewhat more diverse results.13–15 Pruett et al14 found that overnight stays with the second parent were associated with advantages in social functioning and fewer psychological problems among girls. However, McIntosh et al13 found that generally the 2–3 years old who spent 35% or more time with their second parent, experienced more problems compared with their peers who has less contact with their second parent. Tornello et al15 did not find any significant association between custody arrangements in socially and economically disadvantaged families and psychological problems at age 3, but nonetheless found fewer problems among 5-year-old children who had JPC vs single-parent arrangements at age 3.

Coparenting quality and child well-being

High-quality coparenting has been found to contribute to a positive emotional family climate and to affect child mental health and social adjustment positively.16 Children whose parents work well together in childrearing issues are typically better off during early childhood, adolescence and adulthood.17 The association between coparenting quality and child well-being outcomes seems to be stronger than other characteristics of parental relationships, such as intimacy and love.18 The lower levels of health and well-being observed among children with separated parents may thus hypothetically be linked to their parents’ ability to amicably share the responsibilities of childrearing.19 It is important to highlight that coparenting quality is a broader construct than parental conflict. Not only does coparenting include positive measures, it is conceptually distinct from the quality of parental relationships because it directly involves the children.17

The aim of this study was to investigate whether mental health in the 3-year-old children is associated with their living arrangements after a parental separation, and whether parental coparenting quality moderates this association.

Methods

Study population

The population of this study was sampled from a total population of 19 294 children in a defined geographical area in the Stockholm county, who were invited to a routine visit at the age of 3 years by the regional Preventive Child Healthcare (PCHC) from December 2015 to May 2018. The PCHC is funded by regional taxes and their services are offered to all children who reside in the county free of charge. In the invitation letter, parents were informed about the study and that the survey would be used to individualise the visit at the PCHC. The letter included a web-link to the survey which was only available in Swedish.

In total, 13 493 surveys were submitted. Of these, 112 surveys were excluded because the participants had reported that they were the sole parent of the child since childbirth and 32 surveys were excluded because parents had completed the survey twice for the same child. We also excluded 504 surveys because they were completed by someone other than a parent or because information was missing on main variables of interest. Thus, 12 845 children were included in the study, equivalent to a participation rate of 66.6% of the total population of 3 years old in the area.

Patient and public involvement statement

Parents to children in the child health services in Stockholm were involved in the piloting phase of this study, where they provided feedback on questionnaires and the procedure in qualitative interviews and in a quantitative evaluation in writing. We do not plan to have parents involved in the dissemination of the results of the study.

Procedure

The survey included questions on sociodemographic background, children’s development, behaviours and symptoms, parents’ worries, and coparenting quality. Parents were encouraged to complete the survey together.

Measures

Outcome measure

The main outcome in the study was based on parental report of the Swedish version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) which has been successfully validated for preschool-aged children.20 We used the total sum of scores from the four symptom subscales (SDQ Total Difficulties) ranging from 0 to 40.

Living arrangements

Living arrangement groups were based on parents’ answers to the question ‘What does the child’s family look like? The child lives with…’. The options were: (1) intact family, (2) JPC (about 50/50 in each parent’s home), (3) living mostly with mother/father (collapsed here to living mostly with one parent) and (4) living only with mother/father (collapsed here to living only with one parent).

Coparenting quality

Coparenting was measured using a four-item scale inspired by the coparenting scale posited by McHale and Kuersten-Hogan.21 Parents were asked about their ability to cooperate, support each other and confide in/trust each other, and the extent to which they experienced conflict related to their children. Items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (disagree completely) to 5 (agree completely). Higher scores indicated better coparenting. The scale showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.79). Confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit for the one factor model: Comparative Fit Index=0.99; Tucker-Lewis Index=0.98; root mean square error of approximation=0.066 (90% CI=0.056–0.076). For the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) analyses, we used a dichotomisation where coparenting quality of 15 and below was considered low while coparenting quality of 16 and above was considered high. Parents who had chosen the option 3 (neither agree or disagree) for at least one of the four items were thus dichotomised as reporting low coparenting quality.

Background data on children and parents

We used the following background characteristics: child gender (girl/boy); responding parent (categorised as mother/father/both, where both included a few cases of same-sex parents); mothers’ and fathers’ age presented as mean and SD; mothers’ and fathers’ highest level of education (compulsory/high school/university (less than 3 years)/university (3 years or more)/not reported); and mothers’ and fathers’ country of birth (grouped as Sweden/other/not reported).

Statistical analyses

The scores were scaled up prorata for the coparenting scale if only one item was missing, and for SDQ if only one or two items per subscale were missing. Hierarchical regression models were estimated in three steps with the SDQ total score as the outcome, living arrangements as the exposure variable and JPC as reference. Model 1 adjusted for child gender and whether the survey was filled in by the mother, father or both. Model 2 added maternal education. In the fully adjusted model 3, coparenting quality as a continuous measure was added to model 2. To investigate the possibility that coparenting quality moderated the association between family type and the SDQ total score for children, we used factorial ANCOVA with children’s living arrangement and coparenting quality (dichotomised into high and low levels) as factors and child gender, the survey being filled in by the mother and mother’s education (at least 3 years of university education) entered as covariates. Due to small sample sizes the categories of children living mostly or only with one parent were collapsed in the sensitivity analyses.

Results

Background characteristics

Characteristics of children and parents are presented in table 1. About 95% of the 3 years old lived with both parents, in intact families. Children in equal JPC constituted 2.6% of the total sample, while 1.2% of the children lived mostly with one parent and as many lived only with one parent. The sample included slightly more boys than girls in all family types. In intact families, most parents completed the survey together, while in other family types, mothers often completed the survey alone. Separated mothers were slightly younger than those in intact families and fathers in single care families were younger than fathers in the other family types. A university-level education of at least 3 years was most common for mothers and fathers in intact families and least common in families where the child only lived with one parent. More children to parents born outside of Sweden lived only with one parent compared with JPC. Data on father’s educational level as well as on parents’ country of birth was missing for a large part of the sample. Low coparenting quality was more common among parents who did not live together and in particular in families where the child only lived with one parent.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children and parents in different living arrangements

| Sociodemographic variables | Total sample (n=12 845) |

Children’s living arrangements | ||||||||

| Intact family (n=12 203) |

Joint physical custody (n=332) |

Mostly with one parent (n=151) |

Only with one parent (n=159) |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Child gender | ||||||||||

| Girl | 6220 | 48.1 | 5903 | 48.0 | 163 | 48.5 | 75 | 49.7 | 79 | 49.1 |

| Boy | 6641 | 51.3 | 6313 | 51.4 | 171 | 50.9 | 76 | 50.3 | 81 | 50.3 |

| Not reported | 76 | 0.6 | 73 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Responding parent | ||||||||||

| Female (mother) | 5342 | 41.3 | 4873 | 39.7 | 201 | 59.8 | 126 | 83.4 | 142 | 88.2 |

| Male (father) | 1058 | 8.2 | 968 | 7.9 | 73 | 21.7 | 12 | 7.9 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Two parents together* | 6519 | 50.4 | 6433 | 52.3 | 60 | 17.9 | 13 | 8.6 | 13 | 8.1 |

| Not reported | 18 | 0.1 | 15 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Mother age (mean, SD)† | 35.39 | 4.66 | 35.47 | 4.58 | 34.18 | 5.06 | 33.99 | 6.26 | 32.84 | 6.49 |

| Father age (mean, SD)‡ | 37.60 | 5.48 | 37.64 | 5.46 | 36.05 | 5.56 | 37.85 | 4.42 | 33.56 | 9.00 |

| Mother highest level of education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory | 203 | 1.6 | 168 | 1.4 | 15 | 4.5 | 7 | 4.6 | 13 | 8.2 |

| High school | 2751 | 21.4 | 2528 | 20.7 | 85 | 25.6 | 65 | 43.0 | 73 | 45.9 |

| University less than 3 years | 1307 | 10.2 | 1238 | 10.1 | 35 | 10.5 | 16 | 10.6 | 18 | 11.3 |

| University more than 3 years | 7284 | 56.7 | 7075 | 58.0 | 115 | 34.6 | 49 | 32.5 | 45 | 28.3 |

| Not reported | 1300 | 10.1 | 1194 | 9.8 | 82 | 24.7 | 14 | 9.3 | 10 | 6.3 |

| Father highest level of education | ||||||||||

| Compulsory | 172 | 1.3 | 161 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.2 | 3 | 2.0 | 4 | 2.5 |

| High school | 2046 | 15.9 | 1984 | 16.3 | 52 | 15.7 | 5 | 3.3 | 5 | 3.1 |

| University less than 3 years | 902 | 7.0 | 879 | 7.2 | 17 | 5.1 | 6 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| University more than 3 years | 4166 | 32.4 | 4098 | 33.6 | 55 | 16.6 | 8 | 5.3 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Not reported | 5559 | 43.3 | 5081 | 41.6 | 204 | 61.4 | 129 | 85.4 | 145 | 91.2 |

| Mother country of birth | ||||||||||

| Sweden | 7051 | 54.9 | 6716 | 55.0 | 171 | 51.5 | 81 | 53.6 | 83 | 52.2 |

| Other | 1440 | 11.2 | 1383 | 11.3 | 18 | 5.4 | 13 | 8.6 | 26 | 16.4 |

| Not reported | 4354 | 33.9 | 4104 | 33.6 | 143 | 43.1 | 57 | 37.7 | 50 | 31.4 |

| Father country of birth | ||||||||||

| Sweden | 4484 | 34.9 | 4374 | 35.8 | 89 | 26.8 | 14 | 9.3 | 7 | 4.4 |

| Other | 872 | 6.8 | 853 | 7.0 | 9 | 2.7 | 2 | 1.3 | 8 | 5.0 |

| Not reported | 7489 | 58.3 | 6976 | 57.2 | 234 | 70.5 | 135 | 89.4 | 144 | 90.6 |

| Coparenting quality | ||||||||||

| High | 11 314 | 88.1 | 10 972 | 89.9 | 218 | 65.7 | 70 | 46.4 | 54 | 34.0 |

| Low | 1531 | 11.9 | 1231 | 10.1 | 114 | 34.3 | 81 | 53.6 | 105 | 66.0 |

*Includes some same sex parents,

†n=9028.

‡n=5697.

Child mental health in relation to background characteristics

Mental health problems according to SDQ for children in different family types are reported in table 2. Fewer problems were reported for children in intact families followed by children in JPC. Children living mostly or only with one parent had more mental health problems. Boys had more problems compared with girls and children of mothers with high educational levels suffered from less problems compared with those with less educated mothers.

Table 2.

Mean values and SD of the SDQ in relation to sociodemographic variables

| SDQ total score | |||

| n | Mean | SD | |

| Living arrangement | |||

| Intact family | 12 203 | 7.07 | 4.23 |

| Joint physical custody | 332 | 7.26 | 4.50 |

| Mostly with one parent | 151 | 8.45 | 5.28 |

| Only with one parent | 159 | 8.55 | 5.32 |

| Child gender | |||

| Girl | 6213 | 6.70 | 4.10 |

| Boy | 6632 | 7.50 | 4.39 |

| Responding parent | |||

| Female (mother) | 5315 | 6.95 | 4.26 |

| Male (father) | 1052 | 7.30 | 4.34 |

| Two parents together* | 6478 | 7.21 | 4.27 |

| Mother highest level of education | |||

| Compulsory | 203 | 8.72 | 5.56 |

| High school | 2751 | 7.67 | 4.53 |

| University less than 3 years | 1307 | 7.31 | 4.31 |

| University more than 3 years | 7284 | 6.77 | 4.04 |

| Not reported | 1300 | 7.41 | 4.45 |

*Includes some same sex parents.

SDQ, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Multivariate modelling

Table 3 shows the results from linear regression models, which suggest, in model 1 controlling for child gender and respondent parent, that 3 years old living mostly or only with one parent, compared with those in JPC, had more mental health problems. However, the 3 years old in intact families were not significantly different from those in JPC in terms of mental health. When maternal education was added, in model 2, the differences between those living only and mostly with one parent and those in JPC were attenuated. Coefficients remained significant, however, indicating that only some of the differences were explained by the background characteristics. In model 3, after including coparenting quality, the differences between those living only and mostly with one parent and in JPC were no longer significant. Instead, differences between children in intact families and JPC became significant suggesting that children living in JPC showed fewer problems compared with children in intact families after controlling for coparenting quality.

Table 3.

Linear regression models of parental reports of the SDQ total difficulties by living arrangement, sociodemographic variables and coparenting quality (n=12 845)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

| B | 95% CI | P value | B | 95% CI | P value | B | 95% CI | P value | |

| Living arrangement | |||||||||

| Joint physical custody | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Intact family | −0.26 | −0.72 to 0.21 | 0.283 | −0.11 | −0.58 to 0.36 | 0.643 | 0.70* | 0.24 to 1.15 | 0.003 |

| Living mostly with one parent | 1.27* | 0.45 to 2.09 | 0.002 | 1.18* | 0.37 to 2.00 | 0.004 | 0.14 | −0.66 to 0.93 | 0.735 |

| Living only with one parent | 1.38* | 0.58 to 2.19 | 0.001 | 1.20* | 0.40 to 2.00 | 0.003 | −0.25 | −1.03 to 0.54 | 0.537 |

| Child gender | |||||||||

| Girl | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Boy | 0.78* | 0.64 to 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.78* | 0.63 to 0.93 | 0.000 | 0.74* | 0.60 to 0.88 | 0.000 |

| Respondent | |||||||||

| Female (mother) | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Male (father) | 0.34* | 0.06 to 0.62 | 0.019 | −0.37 | −0.96 to 0.22 | 0.220 | −0.38 | −0.95 to 0.20 | 0.199 |

| Two parents together | 0.31* | 0.16 to 0.47 | 0.000 | 0.37* | 0.21 to 0.53 | 0.000 | 0.60* | 0.45 to 0.75 | 0.000 |

| Mother’s highest level of education | |||||||||

| University (3 years or more) | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Compulsory | 1.92* | 1.32 to 2.51 | 0.000 | 1.99* | 1.42 to 2.57 | 0.000 | |||

| High school | 0.88* | 0.69 to 1.07 | 0.000 | 0.80* | 0.62 to 0.98 | 0.000 | |||

| University (less than 3 years) | 0.56* | 0.32 to 0.81 | 0.000 | 0.52* | 0.28 to 0.76 | 0.000 | |||

| Not reported | 1.07* | 0.53 to 1.60 | 0.000 | 1.06* | 0.54 to 1.58 | 0.000 | |||

| Coparenting quality | −0.45* | −0.48 to −0.42 | 0.000 | ||||||

*P<0.05.

†Includes some same sex parents.

SDQ, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire.

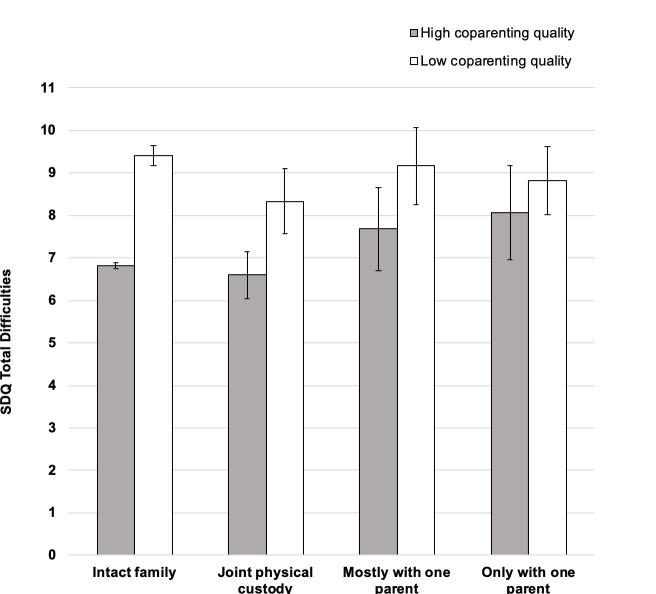

Factorial ANCOVA

The factorial ANCOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction effect for children’s living arrangement by coparenting quality F(3, 12 834)=3.770, p=0.010. Figure 1 shows the estimated marginal means for children’s living arrangement by coparenting quality. Separate one-way ANCOVAs on low and high coparenting groups showed that the overall effect of family type was significant for the high coparenting group (F(3, 11 307)=2.83, p=0.037) and non-significant for the low coparenting group (F(3, 1524)=2.11, p=0.097). To limit the number of post-hoc comparisons and in line with our main research question, we only tested the differences between JPC and other family types. In the high coparenting group, children in JPC showed fewer problems compared with those living only with one parent (mean difference=−1.44, p=0.020). No significant differences were found between children living in JPC families and those in intact families or living mostly with one parent (mean difference=−0.21 and −1.06, p=0.458, and 0.058, respectively).

Figure 1.

Estimated marginal means with error bars with 95% CIs for children’s living arrangements by coparenting quality. SDQ, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Next, separate one-way ANCOVAs on the four family types showed that high-quality coparenting was associated with fewer mental health problems for children living in intact and JPC families (F(1, 12 198)=435.25, p<0.001 and F(1, 327)=9.40, p=0.002, respectively). For children living mostly or only with one parent this difference was smaller and not statistically significant (F(1, 146)=2.38, p=0.125 and F(1, 154)=0.54, p=0.463, respectively).

Sensitivity analyses

As sensitivity analyses, we used multiple imputation (MI) to impute missing values on SDQ and coparenting scale (imputed at item level), as well as mother education (compulsory and high school had to be combined to run the MI). The regression analyses and estimated marginal means in the ANCOVA model revealed the same pattern of results (not shown).

Furthermore, considering that1 the overall pattern of results was very similar for children living mostly and only with one parent, and2 the sample size was smaller in these two groups, we repeated all the ANOCVA analyses with these two family types grouped together.

The factorial ANCOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction effect for children’s living arrangement by coparenting quality F(2, 12 836)=5.48, p=0.004. Separate one-way ANCOVAs on low and high coparenting groups indicated that the overall effect of family type was significant for both high and low coparenting groups (F(2, 11 308)=4.12, p=0.016 and (F(2, 1525)=3.05, p=0.048). Post hoc comparisons showed that in the high coparenting group, children in JPC showed similar levels of problems to those living in intact families (mean difference=−0.21, p=0.458), but fewer problems compared with those living mostly/only with one parent (mean difference=−1.23, p=0.008). In the low coparenting group, children in JPC showed fewer problems compared with those living in intact families (mean difference=−1.10, p=0.018), but did not differ significantly from children living mostly/only with one parent (mean difference=−0.687, p=0.222). Separate one-way ANCOVA on children living mostly/only with one parent revealed a non-significant overall effect of the two coparenting levels (F(1, 305)=2.43, p=0.120).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of 12 845 three years old in Stockholm demonstrated very similar mental health outcomes in children in JPC after parental separation compared with children in intact families, while children living mostly and only with one parent had more mental health problems, net of sociodemographic characteristics. These findings are consistent with another Swedish cohort of 3–5 years old11 and studies on older children in the Nordic countries.(eg, 12 22 23) The addition of coparenting quality in the analyses, however, changed the picture of how children’s mental health is related to family type.

The findings in relation to coparenting quality

Coparenting quality varied largely between the different family forms, with intact families reporting the highest quality and single care parents the lowest. When we adjusted for coparenting quality the differences in mental health between children in JPC and those living mostly or only with one parent disappeared. This finding confirms the conclusion of a systematic review describing coparenting as a key mechanism within the family system for child mental health outcomes following divorce.24

Interestingly, the differences between children in intact families and JPC instead became significant in this analysis, suggesting better mental health in children in JPC. This is surprising since JPC for young children has been questioned by scientists and child experts.25 In the debate the frequent separations from the parents imposed by JPC have been assumed to harm children’s ability to regulate stress and emotions as well as the security in their attachment relations.25 A potential explanation for the positive outcome for children in JPC may however be the positive prerequisites for parenting involved in this living arrangement, as described by parents of 1–4 years old in JPC in an interview study.26 For young children’s mental health, positive parenting practices and high quality in the parent–child relations are particularly important and the interviewed parents described improved parent-child relationships and increased satisfaction in parenting after their divorce.26 27 JPC allowed them to focus entirely on the child when together and they could make decision without having to compromise with a coparent. In a previous study of 3–5 years old, we found no differences in parent reported child mental health between JPC and intact families but could then not include information on coparenting quality or parental conflict.11 It is however possible that this finding is an artefact and it needs to be confirmed in future studies.

The interaction analyses revealed significant interaction effects for living arrangement by coparenting quality for both the high and the low coparenting groups when the categories mostly/only with one parent were collapsed. When coparenting quality is high children in JPC and intact families show similar levels of problems and children in JPC have fewer problems compared with those living mostly/only with one parent.

For families with low coparenting quality the results were similar to those of the main analysis; children in JPC showed fewer problems compared with those living in intact families but did not differ significantly from children living mostly/only with one parent. Coparenting quality hence seems to be a determinant of children’s mental health not only among children with JPC parents, but may be particularly troublesome in intact families. Obviously fights over the children and lack of support, trust and cooperation in the parental relationship influences the family atmosphere to a higher degree when parents live together, compared with when they have separate homes. Low coparenting quality may also hamper parent’s individual relationships to the child and parental efficacy more in intact families. Indeed, prior research has found similar patterns related to parental conflict. In a longitudinal Swedish study, adults who had grown up in intact families characterised by serious disagreement, reported the lowest level of psychological well-being, followed by those who had experienced parental conflict and parental divorce.28 Similarly, another Swedish study found that children who grew up with divorced parents had poorer psychological health as young adults, but parental conflict and economic hardship during childhood attenuated the association.29

We found high-quality coparenting to be associated with fewer mental health problems for children living in intact and JPC families but not for children living mostly or only with one parent. Coparenting quality hence seems to play a lesser role for children when one parent is the primary caregiver and the need for cooperation between the parents is limited. Parenting quality of the primary caregiver may, for these children, be of greater importance.

We have previously discussed whether children’s well-being related to custody arrangements may be explained by socioeconomic status, by an increased closeness to the father in JPC, or by whether children experience a loss of social and economic resources. Earlier studies show that although these factors contributed to children’s well-being, adjusting for them did not eliminate the differences in well-being between children living in different family types.2 9 11 12 23 By exploring the interaction between coparenting quality and family types, we may capture a large proportion of the unmeasured variance; these are differences between groups that have been unexplained in previous studies.

Currently, parenting interventions mainly focus on improving the quality of parenting children receive and primarily target mothers.30 Unfortunately, positive effects of such programmes have not been extended to coparenting quality.31 Our results suggest that coparenting skills may be an important and distinct dimension that should be given more attention in parenting interventions and that such programmes should be evaluated in terms of their impact on child well-being and mental health.32 33

Methodological considerations

Compared with earlier studies examining JPC among very young children, this study has considerable advantages. First, the size of our sample of children in this living arrangement by far exceeds that of earlier studies and enables more detailed groupings. However, in some analyses the smallest groups were collapsed to gain power. Second, these children live in about equal JPC, whereas JPC in other studies may be based on overnights or unequal distribution of time between the parents’ homes. Furthermore, the inclusion of the coparenting measure contributes to the explanation of children’s psychological health in different family types. We do, however, acknowledge that our assessment of coparenting quality was a modified tool of four items, inspired by McHale et al. The scale was adapted to a community healthcare setting where survey items needed to be related to child well-being, suitable for discussion with the PCHC nurse and possible for parents to complete together as well as individually. The four items represent the core dimensions of coparenting as stipulated by McHale et al.21 34 Three of the items relate to aspects of the parental relationship that are important for children’s feelings of security and cohesion; ability to cooperate, support each other, and confide in/trust each other. The fourth item address parents’ conflict over the child, which instead disrupts children’s security if it is intense or ongoing.

Another issue with our measure is that we may not capture the whole variance, as most families score rather high on the measure, which may be related to self-serving bias due to the lack of anonymity. Parents who do not wish to discuss their coparenting relationship with the PCHC nurse may be inclined to report high coparenting quality while those who are dissatisfied with the relationship instead may tend to score low. Furthermore, it seems quite probable that this tendency, leading to overadjustment, may explain the unexpected better mental health of children in JPC compared with children in intact families. We acknowledge that the measure thus needs further validation. Even so, factor analysis suggested that the internal validity was good. More parents in the intact family settings assessed coparenting quality together, whereas one parent more often assessed coparenting in the non-intact families. To address this issue, we adjusted for whether the respondent was the father or mother or both parents. Finally, we successfully recruited a high percentage of the children in the general population to the study (67%), though we were not able to examine the differences between those who did and did not participate.

It is important to note that the relation between children’s mental health problems and coparenting quality is not causal. Having a toddler with behavioural problems may impact the coparenting relationship and parents’ perceptions of their children’s mental health may be influenced by their common abilities to handle the child. Further longitudinal studies are needed to determine the direction of this relation. Also, regarding causality, there is no information in this study about what factors lead to better or worse coparenting quality. Sharing parental responsibilities has previously been shown to be associated with reduced workload,35 more time for leisure activities,36 and improved communication between parents.35 37

The results of this study show considerable differences in maternal education between livingarrangements, with more mothers in intact families having a university degree versus separated mothers. There were high numbers of data missing on other potentially important socioeconomic covariates. Socioeconomic as well as other selection factors that were not included in our analysis, such as parent mental health and addictive problems, may hence cause residual confounding in the comparison between family types.

Implications

This study does not support claims that JPC is psychologically harmful for preschool children in general. Our results rather indicate that the promotion of coparenting quality should be emphasised in policy and prevention of mental health for young children living with both parents as well as after parental separation. For children living mostly or only with one parent, interventions that focus on parenting skills and positive parenting behaviours should be given priority.

Conclusion

This study shows that the 3 years old in JPC have better mental health than their counterparts who live mostly or only with one parent and that coparenting quality contributes to the understanding of early child mental health, not only in children with separated parents but also in intact families. Coparenting quality is hence an important health determinant that clinicians and social workers can target with interventions, regardless of the family situation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to nurses at the Stockholm well-baby clinics and to the families that participated in this research project.

Footnotes

MB and RS contributed equally.

Contributors: MB, EF and AH initiated and funded this study and created the framework for the data collection and analysis together with KB. KB supervised the data collection and prepared the collected data for analysis. RS designed and performed all statistical analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript together with MB. All authors revised the draft and have approved of the final version.

Funding: This research was funded by The Wallenberg foundation (AH) and Forte (MB and EF; Dnr 2014-0843).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data to this study come from routine preventive child health services in Stockholm and may only be obtained through the permission of the regional medical council.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2015–2 28 631) and parents to children in the PCHC were involved in the piloting phase of this study.

References

- 1.Weitoft GR, Hjern A, Haglund B, et al. Mortality, severe morbidity, and injury in children living with single parents in Sweden: a population-based study. The Lancet 2003;361:289–95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12324-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergström M, Fransson E, Modin B, et al. Fifty moves a year: is there an association between joint physical custody and psychosomatic problems in children? J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:769–74. 10.1136/jech-2014-205058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swedish Government Official Report . 2011:51 Fortsatt föräldrar - om ansvar, ekonomioch samarbete för barnets skull. [Continuous parenthood: about responsibilities, economy and cooperation for the sake of the child]. Statens offentliga utredningar. Stockholm: Fritze, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitterød RH, Wiik KA. Shared residence among parents living apart in Norway. Fam Court Rev 2017;55:556–71. 10.1111/fcre.12304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottosen HM, Stage S, tal Di. En analyse af skilsmissebørns samvær baseret på SFI’s børneforløbsundersøgelse [Split children in numbers. An analysis of divorce child custody cases based on SFI’s child development study. SFI rapport - Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach . Getrennt gemeinsam erziehen Befragung von Trennungseltern im Auftrag des BMFSFJ [Parenting together separately: A survey of separated parents for the BMFSFJ. Allensbach on Lake Constance, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE) . Structure des familles avec enfants [Structure of families with children], 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastaits K, Mortelmans D. Parenting as mediator between post-divorce family structure and children’s well-being. J Child Fam Stud 2016;25:2178–88. 10.1007/s10826-016-0395-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergström M, Modin B, Fransson E, et al. Living in two homes-a Swedish national survey of wellbeing in 12 and 15 year olds with joint physical custody. BMC Public Health 2013;13:868. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen L. Shared physical custody: summary of 40 studies on outcomes for children. J Divorce Remarriage 2014;55:613–35. 10.1080/10502556.2014.965578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergström M, Fransson E, Fabian H, et al. Preschool children living in joint physical custody arrangements show less psychological symptoms than those living mostly or only with one parent. Acta Paediatr 2018;107:294–300. 10.1111/apa.14004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergström M, Fransson E, Wells MB, et al. Children with two homes: psychological problems in relation to living arrangements in Nordic 2- to 9-year-olds. Scand J Public Health 2019;47:137–45. 10.1177/1403494818769173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntosh J, Smyth B, Kelahar M. Post-separation parenting arrangements and developmental outcomes for infants and children. Collected reports. Three reports prepared for the Australian Government Attorney-General’s. Canberra: Department, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pruett MK, Ebling R, Insabella G. Critical aspects of parenting plans for young children: Interjecting data into the debate about overnights. Fam Court Rev 2004;42:39–59. 10.1177/1531244504421004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tornello SL, Emery R, Rowen J, et al. Overnight custody arrangements, attachment, and adjustment among very young children. J Marriage Fam 2013;75:871–85. 10.1111/jomf.12045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinberg ME. Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: a framework for prevention. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2002;5:173–95. 10.1023/A:1019695015110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHale JP, Irace K. Coparenting in diverse family systems. : McHale JP, Lindahl KM, . Coparenting: a conceptual and clinical examination of family systems. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frosch CA, Mangelsdorf SC. Marital behavior, parenting behavior, and multiple reports of preschoolers' behavior problems: mediation or moderation? Dev Psychol 2001;37:502–19. 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J Marriage and Family 2000;62:1269–87. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahlberg A, Ghaderi A, Sarkadi A, et al. SDQ in the hands of fathers and preschool Teachers-Psychometric properties in a non-clinical sample of 3-5-Year-Olds. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2019;50:132–41. 10.1007/s10578-018-0826-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHale JP, Kuersten-Hogan R, Lauretti A, et al. Parental reports of coparenting and observed coparenting behavior during the toddler period. J Fam Psychol 2000;14:220–36. 10.1037/0893-3200.14.2.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aasen Nilsen S, Breivik K, Wold B, et al. Divorce and family structure in Norway: associations with adolescent mental health. J Divorce Remarriage 2018;59:175–94. 10.1080/10502556.2017.1402655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergström M, Fransson E, Hjern A, et al. Mental health in Swedish children living in joint physical custody and their parents' life satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Psychol 2014;55:433–9. 10.1111/sjop.12148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamela D, Figueiredo B. Coparenting after marital dissolution and children's mental health: a systematic review. J Pediatr 2016;92:331–42. 10.1016/j.jped.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntosh JE, Smyth BM, Kelaher MA. Responding to concerns about a study of infant overnight care postseparation, with comments on consensus: reply to Warshak (2014). Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2015;21:111–9. 10.1037/h0101018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergström M, Sarkadi A, Hjern A, et al. "We also communicate through a book in the diaper bag"-Separated parents’ ways to coparent and promote adaptation of their 1-4 year olds in equal joint physical custody. PLoS One 2019;14:e0214913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renk K, Roddenberry A, Oliveros A, et al. The Relationship of Maternal Characteristics and Perceptions of Children to Children’s Emotional and Behavioral Problems. Child Fam Behav Ther 2007;29:37–57. 10.1300/J019v29n01_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gähler M. Self-Reported psychological well-being among adult children of divorce in Sweden. Acta Sociol 1998;41:209–25. 10.1177/000169939804100212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gähler M, Garriga A. Has the Association Between Parental Divorce and Young Adults’ Psychological Problems Changed Over Time? Evidence From Sweden, 1968-2000. J Fam Issues 2013;34:784–808. 10.1177/0192513X12447177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panter-Brick C, Burgess A, Eggerman M, et al. Practitioner review: Engaging fathers--recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;55:1187–212. 10.1111/jcpp.12280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinquart M, Teubert D. Effects of parenting education with expectant and new parents: a meta-analysis. J Fam Psychol 2010;24:316–27. 10.1037/a0019691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feinberg ME, Kan ML. Establishing family foundations: intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. J Fam Psychol 2008;22:253–63. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doss BD, Cicila LN, Hsueh AC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of brief coparenting and relationship interventions during the transition to parenthood. J Fam Psychol 2014;28:483–94. 10.1037/a0037311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feinberg ME. Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: a framework for prevention. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2002;5:173–95. 10.1023/A:1019695015110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emery RE. Developmental clinical psychology and psychiatry, Vol. 14. Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sodermans AK, Botterman S, Havermans N, et al. Involved fathers, liberated mothers? joint physical custody and the subjective well-being of divorced parents. Soc Indic Res 2015;122:257–77. 10.1007/s11205-014-0676-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinder L. Shared residence: a review of recent research evidence. Child Fam Law Q 2010;22:475–98. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The data to this study come from routine preventive child health services in Stockholm and may only be obtained through the permission of the regional medical council.