Abstract

Gut microbiota (GM) metabolites can modulate the physiology of the host brain through the gut–brain axis. We wished to discover connections between the GM, neurotransmitters, and brain function using direct and indirect methods. A diet with increased amounts of sugar and fat (high-sugar and high-fat (HSHF) diet) was employed to disturb the host GM. Then, we monitored the effect on pathology, neurotransmitter metabolism, transcription, and brain circularRNAs (circRNAs) profiles in mice. Administration of a HSHF diet-induced dysbacteriosis, damaged the intestinal tract, changed the neurotransmitter metabolism in the intestine and brain, and then caused changes in brain function and circRNA profiles. The GM byproduct trimethylamine-n-oxide could degrade some circRNAs. The basal level of the GM decided the conversion rate of choline to trimethylamine-n-oxide. A change in the abundance of a single bacterial strain could influence neurotransmitter secretion. These findings suggest that a new link between metabolism, brain circRNAs, and GM. Our data could enlarge the “microbiome–transcriptome” linkage library and provide more information on the gut–brain axis. Hence, our findings could provide more information on the interplay between the gut and brain to aid the identification of potential therapeutic markers and mechanistic solutions to complex problems encountered in studies of pathology, toxicology, diet, and nutrition development.

Subject terms: Molecular neuroscience, Neuroscience

Introduction

Gut microbiota (GM) metabolites can potentially modulate nearly all aspects of host physiology1, from regulating immunity2 and metabolism3 in the gut to shaping mood and behavior4. These metabolites can act locally in the intestine or can accumulate up to millimolar concentrations in the serum and organs5. Studies have shown that formation of a gut–brain neural circuit for sensory transduction of nutrients enables the gut to inform the brain of all occurrences, and make sense of what has been eaten6. Recent studies have revealed that the GM is important in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD)7,8 and Parkinson’s disease (PD), and that targeting the GM or/GM metabolites could be used to treat neurodegenerative diseases 9,10.

An imbalanced diet that includes a high intake of sugar and fat and insufficient dietary fiber over a long time can cause enteric dysbacteriosis. The latter increases the permeability of the intestinal mucosa, and results in abnormalities in intestinal immunity and glucolipid metabolism. At this time, the dominant bacteria can change readily. For example, Fujisaka and colleagues showed that the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium species and Bacillus species decreased in mice fed a high-fat diet, whereas the abundance of Gram-negative bacteria increased11. Recent studies have shown that obesity is not necessary for dysfunction of the intestinal barrier. That is, hyperglycemia is more likely to drive intestinal-barrier dysfunction and the risk of enteric infection. Hyperglycemia increases the permeability of the intestinal barrier, which provides microbes with more chances to enter the body and cause proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and focal shifts12. Studies have demonstrated that some bacteria can produce bioactive neurotransmitters13,14, and these neurotransmitters are thought to regulate the nervous system activity and behavior of the host15,16. Recently, O Donnell and coworkers revealed that the neuromodulator tyramine produced by commensal bacteria of Providencia species (which colonize the gut) bypassed the requirement for host tyramine biosynthesis and manipulated a host sensory decision in Caenorhabditis elegans17. However, how these bacteria release signals to activate the brain is not known.

Using animal models, several pathways of communication have been identified along the “gut–brain–axis”, including those driven by the immune system, vagus nerve, or by modulation of neuroactive compounds by the microbiota18,19. In recent years, microbiota have been shown to produce and/or consume a wide range of mammalian neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, or gamma-aminobutyric acid13,20. Accumulating evidence in animals suggests that manipulation of these neurotransmitters by bacteria may have an impact in host physiology. Preliminary clinical studies have revealed that microbiota-based interventions can also alter neurotransmitter levels13. Nonetheless, substantially more work is required to determine if microbiota-mediated manipulation of human neurotransmission has physiological implications and, if so, how it may be exploited therapeutically.

We chose a diet with increased amounts of sugar and fat (i.e., a high-sugar and high-fat (HSHF) diet) to disturb the GM, then monitored the effect on pathology, neurotransmitters, metabolism, and transcription of circularRNAs (circRNAs) in mice. We aimed to identify some associations between the functions of the GM, neurotransmitters, and the brain. We also aimed to enlarge the “microbiome–transcriptome” linkage library. This approach would provide more information on the interplay between the gut and brain to aid identification of potential therapeutic markers and mechanistic solutions to complex problems encountered in studies on pathology, toxicology, diets and nutrition development.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ethical approval of the study protocol

All experimental protocols were approved by the Center of Laboratory Animals of the Guangdong Institute of Microbiology (Guangzhou, China). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used.

Preparation and treatments of mice suffering from dysbacteriosis

Adult male KM mice (18–22 g, 6 weeks) were obtained from the Center of Laboratory Animals of Guangdong Province (certificate number: SCXK [Yue] 2008-0020, SYXK [Yue] 2008-0085). They were pair-housed in plastic cages in a temperature-controlled (25 ± 2 °C) colony room at a 12-h light–dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Mice were allocated randomly into two groups of 12: control and model. The mice in the control group were fed a standard diet. The mice in the model groups were fed a HSHF diet. Water was available freely. These treatments lasted for 3 months.

The components of the HSHF diet were 20% sucrose, 15% fat, 1.2% cholesterol, 0.2% of bile acid sodium, 10% casein, 0.6% calcium hydrogen phosphate, 0.4% stone powder, 0.4% premix, and 52.2% basic feed. Heat ratio: protein 17%, fat 17%, carbohydrate 46%.

Preparation and treatment of SAMP8 mice and newborn KM mice

Male SAMP8 mice (5 months; mean bodyweight, 20 ± 5 g) were purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience (SCXK [Jing] 2014-0004). Adult KM mice (18–22 g, 16 females and 8 males, 8 weeks) were obtained from the Center of Laboratory Animal of Guangdong Province (SCXK [Yue] 2008-0020, SYXK [Yue] 2008-0085). All mice were pair-housed in plastic cages in a temperature-controlled (25 ± 2 °C) colony room with a 12-h light–dark cycle. Mice had free access to food and water. All animals were allowed to acclimatize to their surroundings for ≥1 week before initiation of experimentation.

Effects of TMA on Sprague–Dawley rats

Twenty male Sprague–Dawley rats (180–220 g) obtained from the Center of Laboratory Animal of Guangdong Province (SCXK [Yue] 2008-0020, SYXK [Yue] 2008-0085). They were pair-housed in plastic cages in a temperature-controlled (25 ± 2 °C) colony room at a 12-h light–dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats were divided into two groups of 10: normal group, trimethylamine (TMA)-induced group (2 mL/kg/d of 2.5% TMA purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology, Shanghai China).

Influences of Candida albicans and Klebsiella pneumoniae on the cholinergic system in mice

The abundance of C. albicans (a symbiotic opportunistic pathogen in humans) and K. pneumoniae was found to be high in AD patients in our other study (data not shown). We chose these pathogens to ascertain the potential routes of communication/interaction between the host and its resident bacteria on neurotransmitter metabolism and brain function. C. albicans and K. pneumoniae were administered (i.g.) to normal C57 mice by monotherapy or in combination.

Adult male C57 mice (18–22 g, 6 weeks) obtained from Center of Laboratory Animal of Guangdong Province, SCXK [Yue] 2008-0020, SYXK [Yue] 2008-0085 were pair-housed in plastic cages in a temperature-controlled (25 ± 2 °C) colony room at a 12-h light–dark cycle. Twenty C57 mice were divided into four groups: normal, C. albicans-treated, K. pneumoniae-treated, and C. albicans + K. pneumoniae-treated (Ca + Kp).

Measurement of physiological and biochemical indices

The appearance, behavior, and fur color of animals were documented every day. Bodyweight was measured every 3 days during the period of drug administration. Blood samples were drawn by removing the eye under anesthesia (isoflurane). Serum was acquired by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C until measurement. Levels of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, (T-CHO) and high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured with commercially available kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Jiangsu, China). Serum and brain-tissue levels of trimethylamine-n-oxide (TMAO), and neurotransmitter levels were quantified using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

Histopathology and immunostaining

Brain, liver, renal, spinal marrow, spleen, and adipose tissues were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at pH 7.4 for further pathologic observation. These tissue samples were made into paraffin sections after drawing materials, fixation, washing, dehydration, transparency, dipping in wax, and embedding. Obesity-related parameters or other related pathologic changes were measured.

The brains of animals were dissected. Four brains from each group were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and prepared as paraffin sections. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). silver, or underwent Nissl staining and TUNEL staining. Immunostaining using paraffin-embedded sections (thickness = 3 μm) and a two-step method involving a peroxidase-conjugated polymer kit (Envision®; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) was also done. Slides were observed under light microscopy.

Analyses of microbiome 16S rDNA

Fresh samples of intestinal content were collected 12 h before the fasting of rats and stored at −80 °C. Microbial DNA isolated from these samples, with a total mass ranging from 1.2 ng to 20.0 ng, was stored at −20 °C. Microbial 16S rRNA genes were amplified using a forward primer (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and a reverse primer (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification was done and the products were purified, quantified, and homogenized to form a sequencing library. The established library was firstly inspected by the library, and the qualified library was sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2500.

Metabolomics analysis

Aliquots of each standard solution were mixed to generate a stock standard mixture of 4 μg/mL in 50% acetonitrile. This 4 μg/mL standard mixture (100 μL) was mixed with 50 μL of sodium carbonate (100 mM) and 50 μL of 2% benzoyl chloride (BZ) or 2% benzoyl chloride-(phenyl-13C6) (13C6BZ). The reaction mixture was vortex-mixed and diluted to 2400 ng/mL for BZ derivatives and 50 ng/mL with 50% acetonitrile for 13C6BZ derivatives as the internal standard (IS) stock solution. BZ derivatives were serially diluted to 240, 120, 60, 30, 12, 3, 1.2, and 0.02 ng/mL. To prepare the standard curve, the standard BZ derivative solutions stated above were mixed isometrically with 50 ng/mL of IS stock solution to generate calibration levels covering a range of 0.01–1200 ng/mL for all analytes.

Samples of brain tissue

Samples of brain tissue (20 ± 1 mg) were homogenized in a 4-volume (vol/wt) precooled aqueous solution of ascorbic acid (20 mM) with TissueLyser™ JX-24 (Jingxin, Shanghai, China) beads at 30 Hz for 3 min. The homogenates were supplemented with 15-volume prechilled acetonitrile (−40 °C) and vortex-mixed for 1 min before centrifugation at 4 °C and 14,000 × g for 15 min. Derivatization was started by addition of 40 μL of 2% BZ to a mixture of 40 μL of supernatant solution and 20 μL of sodium carbonate (100 mM). Derivatized samples were mixed with IS stock solution to analyze high concentrations of neurotransmitters by ultra-high pressure-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) with an injection volume of 1 μL. The derivatized sample was diluted 10-fold, and the dilution was mixed isometricallywith ISs to analyze low concentrations of neurotransmitters by UPLC-MS/MS with an injection volume of 5 μL.

Samples of intestinal content

Frozen samples of intestinal content (20 ± 1 mg) were homogenized in 5-volume (vol/wt) of a precooled aqueous solution of ascorbic acid (20 mM). After sonication for 3 min, the homogenates were supplemented with 15-volume prechilled acetonitrile (−40 °C) and vortex-mixed for 1 min before centrifugation at 4 °C and 14,000 × g for 15 min. Derivatization was started by addition of 40 μL of 2% BZ to a mixture of 40 μL of supernatant and 20 μL of sodium carbonate (100 mM). Derivatized samples were mixed with IS stock solution to analyze low concentrations of neurotransmitters by UPLC-MS/MS with an injection volume of 1 μL. The derivatized sample was diluted 10-fold, and the dilution was mixed isometrically with ISs to analyze high concentrations of neurotransmitters with UPLC-MS/MS with an injection volume of 10 μL.

UPLC-MS/MS

UPLC-MS/MS was done on a Acquity UPLC system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a Triple Quad™ 5500 tandem mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). Each sample or standard mixture was injected onto a UPLC BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 2 mM ammonium acetate with 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B). Chromatographic separation was conducted by a gradient elution program: 0 min, 1% B; 0.5 min, 1% B; 1 min, 45% B; 4 min, 65% B; 4.2 min, 100% B; 5.2 min, 100% B; 5.3 min, 1% B; 7 min, 1% B. The column temperature was 40 °C.

The analytes eluted from the column were ionized in an electrospray ionization source in positive mode. The conditions were: source temperature, 600 °C; curtain gas, 30 psi; ion source gas 1, 50 psi; ion source gas 2, 50 psi; collision gas, 8 psi; ion spray voltage, 5500 V; entrance potential, 10 V; collision cell exit potential, 14 V. Scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (sMRM) was used to acquire data in optimized MRM transition (precursor > product), declustering potential, and collision energy (Table 1). The total scan time per cycle was 0.25 s. The samples and standard-curve samples were analyzed simultaneously. AB Sciex Analyst v1.5.2 (https://sciex.com/products/software/analyst-software) was used to control instruments and acquire data using the default parameters and assist manual inspection to ensure the qualitative and quantitative accuracies of each compound. The peak areas of target compounds were integrated and outputted for quantitative calculation.

Table 1.

Different expression of circRNAs in the brain of high sugar & fat diet induced dysbacteriosis mice (control vs model group, |Foldchange| >1.50, p < 0.05).

| circRNA_ID | Gene | mmu_circbase_id | Foldchange | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr12_38147502_38190134_+ | Dgkb | NA | −404.091 | 3.28E–06 |

| chr10_90914692_90948672_+ | Anks1b | mmu_circ_0002557 | −401.022 | 4.29E–06 |

| chr17_44638512_44639826_− | Runx2 | mmu_circ_0006773 | −356.377 | 5.55E–05 |

| chr14_14745967_14757431_+ | Slc4a7 | NA | −244.951 | 0.00029 |

| chr13_83625264_83635469_+ | Mef2c | NA | −243.943 | 0.000387 |

| chr14_21833800_21838043_+ | Vdac2 | NA | −227.906 | 0.000523 |

| chr8_70251613_70252101_+ | Sugp2 | mmu_circ_0014931 | −221.4 | 0.000599 |

| chr1_155187777_155197435_+ | Stx6 | mmu_circ_0008281 | −220.455 | 0.001103 |

| chr4_106420433_106423562_+ | Usp24 | NA | −213.924 | 0.000763 |

| chr6_110914326_110915171_+ | Grm7 | mmu_circ_0012931 | −201.04 | 0.001351 |

| chr1_156869440_156888030_− | Ralgps2 | mmu_circ_0008300 | −185.795 | 0.001516 |

| chr17_84710290_84716715_− | Lrpprc | NA | −181.382 | 0.002065 |

| chr10_5172887_5175916_− | Syne1 | NA | −180.507 | 0.001669 |

| chr5_23565113_23629477_– | Srpk2 | NA | −179.396 | 0.001811 |

| chr8_85875633_85957654_+ | Phkb | mmu_circ_0015077 | −174.144 | 0.001996 |

| chr4_88196758_88197016_+ | Focad | mmu_circ_0011840 | −172.585 | 0.004101 |

| chr19_5797448_5798075_− | Malat1 | NA | −171.865 | 0.002093 |

| chr7_63615288_63685551_+ | Otud7a | NA | −168.418 | 0.00227 |

| chr4_86249762_86252840_+ | Adamtsl1 | mmu_circ_0011813 | −168.018 | 0.002479 |

| chr9_10419035_10658287_− | Cntn5 | NA | −167.399 | 0.002821 |

| chr11_36273230_36300430_− | Tenm2 | mmu_circ_0003007 | −166.71 | 0.003624 |

| chr9_60649479_60680171_− | Lrrc49 | NA | −164.043 | 0.003149 |

| chr14_32250016_32262831_+ | Parg | mmu_circ_0000520 | −160.076 | 0.002826 |

| chr7_126169128_126174248_− | Xpo6 | mmu_circ_0013871 | −159.96 | 0.003022 |

| chr13_97929410_97936861_− | Arhgef28 | mmu_circ_0004930 | −157.107 | 0.003519 |

| chr5_106618070_106666845_− | Zfp644 | mmu_circ_0001380 | −152.411 | 0.003532 |

| chr5_137325322_137325674_− | Slc12a9 | NA | −149.073 | 0.005074 |

| chr8_94047271_94055344_+ | Ogfod1 | NA | −145.577 | 0.006017 |

| chr9_21934117_21935628_+ | Ccdc159 | NA | −145.057 | 0.005719 |

| chr6_101169133_101172447_− | Pdzrn3 | mmu_circ_0012894 | −144.036 | 0.004294 |

| chr13_8842729_8861265_− | Wdr37 | NA | −141.159 | 0.004877 |

| chr10_58467114_58470762_+ | Ranbp2 | NA | −140.656 | 0.004984 |

| chr12_3865984_3873428_+ | Dnmt3a | mmu_circ_0003954 | −139.642 | 0.004835 |

| chr6_127729409_127732820_− | Prmt8 | NA | −137.936 | 0.004863 |

| chr8_106981125_106981339_+ | Sntb2 | mmu_circ_0001722 | −136.429 | 0.00534 |

| chr12_111097454_111100038_+ | Rcor1 | mmu_circ_0003755 | −135.001 | 0.005934 |

| chr8_99400725_99401177_− | Cdh8 | NA | −133.903 | 0.005448 |

| chr18_86461041_86473843_+ | Neto1 | NA | −133.846 | 0.005985 |

| chr13_76822972_76925525_+ | Mctp1 | NA | −133.839 | 0.006304 |

| chr9_16021315_16031420_− | Fat3 | mmu_circ_0015421 | −131.089 | 0.006281 |

| chr7_97031337_97040036_+ | Nars2 | NA | −130.142 | 0.005893 |

| chr15_79542486_79543856_− | Ddx17 | NA | −129.349 | 0.005771 |

| chr10_119986331_120010286_+ | Grip1 | NA | −128.055 | 0.005706 |

| chr5_141962664_141975714_+ | Sdk1 | mmu_circ_0012262 | −127.064 | 0.007112 |

| chr11_4803677_4816165_− | Nf2 | NA | −124.657 | 0.006556 |

| chr12_77277360_77365359_+ | Fut8 | mmu_circ_0004207 | −123.76 | 0.007571 |

| chr13_30817997_30826094_− | Exoc2 | NA | −122.612 | 0.007436 |

| chr3_55477804_55489896_+ | Dclk1 | mmu_circ_0010690 | −122.425 | 0.006334 |

| chr9_114705053_114709314_+ | Dync1li1 | mmu_circ_0015352 | −119.173 | 0.007756 |

| chr5_140430051_140433134_+ | Eif3b | NA | −117.743 | 0.007017 |

| chr9_86634645_86679952_− | Me1 | NA | −115.342 | 0.007181 |

| chr16_13790620_13796077_+ | Rrn3 | NA | −115.165 | 0.007354 |

| chr4_109037974_109039914_+ | Nrd1 | NA | −113.931 | 0.007381 |

| chr14_77365025_77441899_+ | Enox1 | NA | −110.46 | 0.008948 |

| chr10_45648590_45649987_+ | Hace1 | NA | −108.435 | 0.008376 |

| chr1_5095614_5135937_+ | Atp6v1h | mmu_circ_0008758 | −107.867 | 0.008232 |

| chr7_97705588_97716539_+ | Clns1a | mmu_circ_0013679 | −104.857 | 0.008756 |

| chr6_36894775_36916461_− | Dgki | NA | −104.678 | 0.00873 |

| chr9_22643744_22659145_+ | Bbs9 | mmu_circ_0015468 | −104.402 | 0.008172 |

| chr4_128296394_128338697_+ | Csmd2 | mmu_circ_0011199 | −103.867 | 0.008444 |

| chr8_123968000_123969922_− | Abcb10 | NA | −103.404 | 0.009222 |

| chr2_69944299_69948510_+ | Ubr3 | NA | −103.071 | 0.009949 |

| chr17_11635309_11673052_+ | Park2 | NA | −102.934 | 0.009596 |

| chr4_36718866_36724085_− | Lingo2 | mmu_circ_0011588 | −102.814 | 0.009541 |

| chr15_38498668_38514609_− | Azin1 | NA | −102.811 | 0.008268 |

| chr4_32826929_32828808_− | Ankrd6 | NA | −101.776 | 0.008501 |

| chrX_140384002_140391454_+ | Frmpd3 | NA | −101.259 | 0.008774 |

| chr1_135394135_135400203_− | Ipo9 | mmu_circ_0008200 | −101.042 | 0.008981 |

| chr4_132656692_132673032_+ | Eya3 | mmu_circ_0001277 | −100.539 | 0.008743 |

| chr18_43562530_43567210_− | Jakmip2 | NA | −100.345 | 0.012209 |

| chr19_27800116_27806908_− | Rfx3 | NA | −98.2611 | 0.01054 |

| chr3_86816357_86831834_− | Dclk2 | NA | −95.8757 | 0.009228 |

| chr12_87075077_87076505_+ | Tmem63c | NA | −95.0844 | 0.010211 |

| chr15_12457797_12458299_− | Pdzd2 | mmu_circ_0005537 | −94.292 | 0.009719 |

| chr9_77164764_77181396_− | Mlip | mmu_circ_0015896 | −94.1348 | 0.010842 |

| chr5_124632878_124639283_+ | Atp6v0a2 | NA | −92.7345 | 0.010875 |

| chr2_158473122_158477763_+ | Ralgapb | mmu_circ_0009519 | −91.3784 | 0.010868 |

| chr11_4799860_4820493_− | Nf2 | mmu_circ_0003054 | −90.1746 | 0.009803 |

| chr18_12871077_12906949_− | Osbpl1a | NA | −89.874 | 0.011312 |

| chr16_56151273_56155375_+ | Senp7 | NA | −89.8398 | 0.010437 |

| chr9_50789496_50792407_+ | Alg9 | NA | −88.074 | 0.011172 |

| chr2_158047918_158058827_+ | Rprd1b | NA | −86.9627 | 0.01007 |

| chr16_38505411_38518532_− | Timmdc1 | NA | −86.7884 | 0.010072 |

| chr6_37048119_37058028_− | Dgki | mmu_circ_0013333 | −86.0778 | 0.010146 |

| chr9_59394877_59412531_− | Arih1 | NA | −85.9027 | 0.00997 |

| chr1_184925815_184945000_− | Mark1 | NA | −85.741 | 0.010481 |

| chr4_58861524_58875573_− | AI314180 | mmu_circ_0011714 | −84.1099 | 0.011083 |

| chr9_24473773_24485101_− | Dpy19l1 | NA | −83.2237 | 0.010312 |

| chr1_143667624_143677855_− | Cdc73 | mmu_circ_0008242 | −82.7125 | 0.010813 |

| chr8_68460923_68461851_− | Csgalnact1 | mmu_circ_0014912 | −82.7124 | 0.010799 |

| chr6_148411037_148425984_− | Tmtc1 | mmu_circ_0013190 | −81.6378 | 0.010321 |

| chr4_155626773_155628823_+ | Cdk11b | mmu_circ_0011499 | −80.5751 | 0.011413 |

| chr17_87678207_87680078_+ | Msh2 | NA | −80.3893 | 0.010289 |

| chr2_6721416_6747946_− | Celf2 | NA | −80.0149 | 0.012001 |

| chr9_96287600_96310688_+ | Tfdp2 | mmu_circ_0016010 | −78.0619 | 0.012609 |

| chr14_13995006_14053023_+ | Atxn7 | mmu_circ_0005063 | −76.833 | 0.011972 |

| chrX_167363544_167374186_− | Prps2 | NA | −75.4238 | 0.013103 |

| chr4_150431522_150431985_+ | Rere | mmu_circ_0011440 | −65.5894 | 0.012612 |

| chr14_29333708_29396583_− | Cacna2d3 | NA | −65.0899 | 0.013294 |

| chr6_51562017_51589065_+ | Snx10 | NA | −64.6467 | 0.014026 |

| chr14_62733627_62743998_− | Ints6 | NA | −64.3073 | 0.01361 |

| chr7_56982624_56985163_− | Gabrg3 | mmu_circ_0014270 | −62.3892 | 0.014665 |

| chr13_91968946_91972285_− | Rasgrf2 | mmu_circ_0004873 | −61.1195 | 0.015346 |

| chr14_79369077_79370097_− | Naa16 | mmu_circ_0005462 | −58.7143 | 0.014048 |

| chr5_35935551_35936132_+ | Afap1 | mmu_circ_0012596 | −58.398 | 0.005375 |

| chr15_25737449_25742449_+ | Myo10 | mmu_circ_0005560 | −58.3059 | 0.014391 |

| chr6_126013159_126015695_+ | Ano2 | NA | −56.5138 | 0.01669 |

| chr7_91449753_91872500_+ | Dlg2 | NA | −55.3916 | 0.016159 |

| chr5_21194399_21207641_+ | Gsap | NA | −54.8773 | 0.01561 |

| chr8_25592451_25594166_− | Letm2 | NA | −54.5229 | 0.01658 |

| chr2_44570418_44591990_− | Gtdc1 | NA | −51.9963 | 0.007337 |

| chr5_128761339_128780376_− | Rimbp2 | mmu_circ_0012149 | −51.8159 | 0.016427 |

| chr13_8672404_8701731_+ | Adarb2 | mmu_circ_0004840 | −51.1778 | 0.007795 |

| chr17_44717191_44724901_− | Runx2 | mmu_circ_0000795 | −50.8107 | 0.012892 |

| chr18_34268297_34300061_+ | Apc | mmu_circ_0007251 | −45.3232 | 0.013193 |

| chr3_118759655_118811267_+ | Dpyd | NA | −44.9853 | 0.018425 |

| chr11_117290397_117291036_+ | 9-Sep | mmu_circ_0002788 | −44.5989 | 0.01282 |

| chr14_33388799_33402923_− | Mapk8 | NA | −43.5971 | 0.018773 |

| chr9_121364000_121392051_+ | Trak1 | NA | −36.6467 | 0.007726 |

| chr2_80520371_80525678_− | Nckap1 | mmu_circ_0001039 | −33.3722 | 0.010502 |

| chr7_75140075_75149088_− | Sv2b | NA | −29.0699 | 0.002013 |

| chr16_60424720_60425384_− | Epha6 | mmu_circ_0000694 | −29.0005 | 0.01947 |

| chr4_59207760_59213977_+ | Ugcg | NA | −28.8672 | 0.006424 |

| chr17_74770242_74799411_+ | Ttc27 | NA | −23.7796 | 0.018256 |

| chr12_66506105_66506822_− | Mdga2 | mmu_circ_0004128 | −20.9794 | 0.012785 |

| chr7_133862102_133870087_+ | Fank1 | mmu_circ_0013965 | −18.4343 | 0.011266 |

| chr1_164340728_164347879_+ | Nme7 | mmu_circ_0008373 | −18.2923 | 0.005958 |

| chr2_115669581_115687169_+ | BC052040 | mmu_circ_0001057 | −14.198 | 0.016445 |

| chr5_122429485_122433537_+ | Anapc7 | mmu_circ_0012079 | 14.58085 | 0.012689 |

| chr3_125914637_125915461_− | Ugt8a | mmu_circ_0010433 | 14.9599 | 0.014812 |

| chr4_84390888_84414348_− | Bnc2 | mmu_circ_0001224 | 19.49736 | 0.007617 |

| chr5_139181416_139184719_+ | Heatr2 | mmu_circ_0012236 | 56.47568 | 0.006519 |

| chr8_40348939_40359448_+ | Micu3 | NA | 61.38255 | 0.014883 |

| chr8_125886933_125888193_− | Pcnxl2 | NA | 62.23414 | 0.014888 |

| chr17_6198671_6201834_+ | Tulp4 | NA | 64.37413 | 0.003266 |

| chr16_55918537_55923040_− | Cep97 | NA | 71.82017 | 0.013319 |

| chr7_139845584_139852657_+ | Gpr123 | NA | 74.60841 | 0.014702 |

| chr13_59473687_59482604_− | Agtpbp1 | mmu_circ_0004710 | 78.31382 | 0.012486 |

| chr15_64191483_64349913_− | Asap1 | NA | 78.71352 | 0.01227 |

| chr1_89627760_89671271_+ | Agap1 | NA | 79.23549 | 0.014461 |

| chr2_163040626_163042799_+ | Ift52 | NA | 80.06381 | 0.012829 |

| chr4_132910691_132913826_− | Fam76a | NA | 82.11838 | 0.013523 |

| chr16_96152970_96154195_+ | Wrb | NA | 91.7975 | 0.011942 |

| chr17_50782260_50800195_− | Tbc1d5 | NA | 92.09871 | 0.012202 |

| chr8_31849309_31968185_− | Nrg1 | NA | 92.93369 | 0.012086 |

| chr13_119782771_119790287_− | Zfp131 | NA | 94.26963 | 0.011376 |

| chr5_89038450_89058044_+ | Slc4a4 | NA | 94.35752 | 0.012803 |

| chr7_97636376_97653207_+ | Rsf1 | NA | 95.61444 | 0.010142 |

| chr7_37649685_37658660_− | Zfp536 | NA | 99.19821 | 0.011147 |

| chr6_97189528_97199321_− | Uba3 | mmu_circ_0013630 | 100.1458 | 0.009487 |

| chr19_46449828_46453315_+ | Sufu | NA | 101.4795 | 0.009533 |

| chr5_76265790_76274043_− | Clock | mmu_circ_0012787 | 102.1796 | 0.011921 |

| chr5_34419997_34444913_+ | Fam193a | mmu_circ_0001340 | 103.6374 | 0.009949 |

| chr4_59596862_59601567_+ | Hsdl2 | NA | 105.3806 | 0.010751 |

| chr6_119369859_119370408_− | Adipor2 | mmu_circ_0013007 | 107.8557 | 0.009198 |

| chr10_30762739_30771840_− | Ncoa7 | mmu_circ_0002155 | 108.1671 | 0.008979 |

| chr8_79070370_79076538_+ | Zfp827 | mmu_circ_0015001 | 111.6757 | 0.008381 |

| chr14_99179314_99196451_+ | Pibf1 | NA | 112.7662 | 0.010379 |

| chr2_10393264_10461472_+ | Sfmbt2 | NA | 114.4586 | 0.008053 |

| chr4_102487210_102515611_+ | Pde4b | NA | 114.7701 | 0.007858 |

| chr16_62769606_62776383_− | Nsun3 | NA | 114.8451 | 0.009533 |

| chr7_126886207_126889060_– | Tmem219 | NA | 115.4738 | 0.008434 |

| chr1_139039999_139110485_+ | Dennd1b | mmu_circ_0000082 | 116.1391 | 0.007941 |

| chr1_156620838_156625583_+ | Abl2 | NA | 116.4107 | 0.007942 |

| chr4_74357341_74377800_+ | Kdm4c | NA | 116.9301 | 0.007803 |

| chr4_150468694_150470391_+ | Rere | NA | 120.5443 | 0.00708 |

| chr3_152317613_152320743_– | Fam73a | NA | 122.1839 | 0.007135 |

| chr11_102860001_102865660_− | Eftud2 | mmu_circ_0002659 | 122.9623 | 0.008327 |

| chr12_55757925_55762737_– | Ralgapa1 | mmu_circ_0004092 | 124.9689 | 0.006679 |

| chr3_131599812_131607463_+ | Papss1 | NA | 125.3036 | 0.00663 |

| chr13_94210576_94233180_− | Scamp1 | NA | 139.1756 | 0.005192 |

| chr10_49522142_49535499_− | Grik2 | NA | 148.6745 | 0.004614 |

| chr11_23281305_23282726_+ | Xpo1 | mmu_circ_0002894 | 153.5301 | 0.004153 |

| chr5_44592732_44799437_− | Ldb2 | NA | 163.2662 | 0.003521 |

| chr18_82955523_82957449_+ | Zfp516 | mmu_circ_0000909 | 178.6214 | 0.00208 |

| chr8_88156461_88158265_+ | Heatr3 | mmu_circ_0015094 | 451.1435 | 2.85E-06 |

Isolation and sequencing of RNA

Total RNA was isolated using QIAzol™ (Qiagen, Germany) and miRNeasy™ kits (Qiagen, Germany), including additional DNase I digestion. Then, ribosomal RNA was removed using the Ribo-Zero™ Magnetic Gold kit (Qiagen, Germany), and enzymatic degradation of linear RNA was done using Rnase R enzyme. Fragmentation buffer was added to fragments. The first chain of complementary (c)DNA was synthesized with six-base random hexamers. Then, the buffer, dNTPs, RNase H, and DNA polymerase I were added to synthesize the second chain of cDNA. Purification using the QiaQuick™ PCR kit and elution using EB buffer after terminal repair, processing of base A, and addition of sequencing joints were carried out. For next-generation sequencing, 0.5 μg of ribosomal RNA-depleted RNA was fragmented and primed. Sequencing libraries were constructed using TruSeq™ RNA Sample Preparation kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq™ 2500 flow cells.

Computational analysis of circRNAs

First, reads were mapped to the latest University of California Santa Cruz transcript set using Bowtie2 v2.1.0 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml). Gene expression was estimated using RSEM v1.2.15. For analyses of lincRNA expression, we used the transcripts set from Lncipedia (www.lncipedia.org/). Trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) was used to normalize gene expression. Differentially expressed genes were identified using the edgeR program. Genes showing altered expression with p < 0.05 and >1.5-fold changes were considered to have differential expression. Pathway analysis and network analysis were undertaken using Ingenuity (IPA). IPA computes a score for each network according to the fit of a set of supplied focus genes. These scores indicate the likelihood of focus genes belonging to a network versus those obtained by chance. Score >2 indicates a ≤99% confidence that a focus gene network was not generated by chance alone. The canonical pathways generated by IPA are the most significant for the uploaded dataset. Fischer’s exact test with a false discovery rate (FDR) option was used to calculate the significance of the canonical pathway.

For analyses of circRNA expression, reads were to mapped a genome using STAR. DCC was employed to identify and estimate expression of a particular circRNA. TMM was used to normalize gene expression. Differentially expressed genes were identified using edgeR. miRanda was employed to predict the miRNA target of the circRNA. R (R Institute for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used to generate figures.

circRNA verification by real-time reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

We wished to validate the reliability of high-throughput RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and to explore expression of circRNAs during aging. Hence, expression of circRNAs was measured by RT-qPCR. With reference to the method described by Memczak, two sets of primers for each circRNA were designed using Primer Express v5.0 (Table 2): an outward-facing set to amplify only the circRNA, and an opposite-directed set to amplify the linear form.

Table 2.

PCR primers.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′->3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| mmu_circ_0012931 |

circ_0012931-F1: TCCACTTGTTAAGATACCTC circ_0012931-R1: GCAAGAGTAGATACATAATTCC |

168 |

| β-actin |

β-actin-F1: GCTTCTAGGCGGACTGTTAC β-actin-R1: CCATGCCAATGTTGTCTCTT |

100 |

| rno_circ_NF1-419 |

rno_circ_NF1-419-F1: AGTCGAATTTCTACAAGCTTC rno_circ_ NF1-419-R2: AGCTTCTCCAAATATCCTCAT |

179 |

Total RNA was extracted (TRIzol® Reagent, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), digested using RNase R, and purified. cDNA was synthesized using the Geneseed® II First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Outward-facing primers were designed to amplify the fragment across the junction from cDNA, then the fragment was sequenced by Sangon Biological Engineering (Shanghai China). RT-qPCR was undertaken using Geneseed® qPCR SYBR® Green Master Mix (Agilent Technologies). PCR-specific amplification was conducted with an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Expression of circRNAs was defined based on the threshold cycle (Ct), and relative expression was calculated via the 2−ΔΔCt method. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase served as an IS control with all reactions done in triplicate.

Western blotting

Briefly, global brain tissue was dissected from treated mice (purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience; SCXK (Jing) 2014-0004) and proteins extracted with a radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (T-PER™ Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent; catalog number, 78510; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blockade with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) with 0.2% Tween-20 (T104863; Aladdin, Beijing, China), the PVDF membranes were probed with antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (G2211-1-A; Servicebio, Beijing, China) or goat anti-rabbit (G2210-2-A; Servicebio) IgG secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analyses

Data are the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Significant differences between treatments were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at p < 0.05 using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Prism 5 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

The HSHF diet disrupts the GM

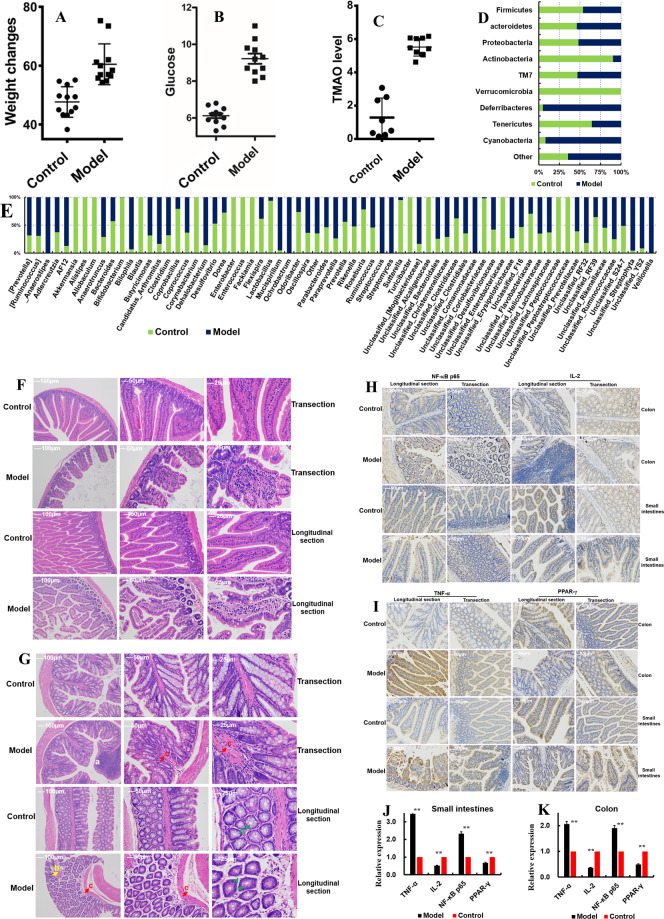

The bodyweights of mice fed a HSHF diet were higher than those fed a standard diet (control, p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A); levels of blood glucose (Fig. 1B) and TMAO (Fig. 1C) were also higher (p < 0.05). These data suggested that the HSHF diet utilized caused increases in bodyweight, blood glucose level, and TMAO level. Sequencing of the 16 S rRNA gene showed that the HSHF diet significantly decreased the operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of bacteria of the phyla Acidobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Tenericutes, and Firmicutes, while increasing the OTUs of bacteria of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Deferribacteres, Cyanobacteria and Actinobacteria (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1A). The OTUs of bacteria from the genera Bifidobacterium (213.12-fold change compared with that in the control group), Coriobacteriaceae (51.02), Sutterella (18.84), Lactobacillus (14.46), Coprobacillus (3.86), Roseburia (3.56), Odoribaccter (2.76), Dorea (2.65), and Flavobacteriaceae (2.39) were decreased significantly (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E), whereas those of AF12 ( − 6.64-fold changes), Bliophila (−13.37), Butyricimonas (−2.14), Paraprevotella (−2.76), Bacteroidales (−2.85), Streptophyta (−20.66), Mucispirillum (−18.50), Candidatus Arthromitus (−5.01), [Mogibacteriaceae] (−4.92), Dehalobacterium (−5.87), RF32 (−4.46), Anaerotruncus (−2.43), Erysipelotrichaceae (−2.73), and Ruminococcaceae (−2.98) were increased significantly (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1B) following administration of the HSHF diet. The whole GM was different between the two groups of mice: control mice and those fed a HSHF diet. Principal component analysis (Fig. S1C), Venn diagram (Fig. S1D), and linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis (Fig. S1E and S1F) could be used to distinguish between these two groups. Hence, the HSHF diet could induce dysbacteriosis in mice. These results are almost identical to data from studies showing that intestinal dysbacteriosis interacts with fat21.

Fig. 1. Dysbacteriosis affects the homeostatic balance of the intestine in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat for 4 months.

A Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on the bodyweight of mice. B Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on the blood glucose level of mice. C Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on TMAO levels in serum. D Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on the gut microbiota at the phylum level. E Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on the gut microbiota at the genus level, see Fig. S2. F, G Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on intestine (F) and colon (G) histopathology using H&E staining, see the pathologic observations in other organs (livers, renal, spinal marrow, spleen, adipose and heart) in Fig. S2. H–K Influences of a diet high in sugar and fat on intestine and colon histopathology using immunohistochemical analyses. Data are the mean ± SD of more than 8 independent experiments (the histopathology data were the mean ± SD of more than 3 independent experiments). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

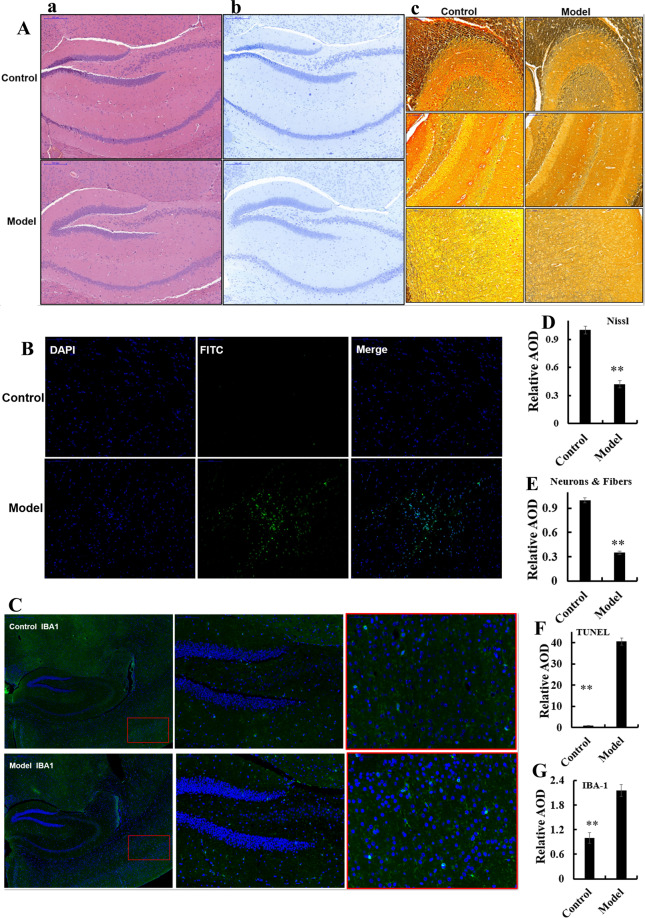

Fig. 2. Dysbacteriosis affects brain histopathology in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat for 4 months.

A Samples were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), see also Fig. S3A-a. B, D Samples underwent Nissl staining, see also Fig. S31A-b. C, E Samples were stained using silver, see also Fig. S3A-c. D, F Samples underwent TUNEL staining, see also Fig. S3A-d. C, G Samples were stained using immunofluorescent microglial of IBA-1, see also Fig. S3B-b. Data are the mean ± SD of 5 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

The HSHF diet changes the steady state of the intestine

Intestinal dysbacteriosis were considered first affects the intestinal physiology22. The pathology of the small intestine and colon of mice fed the HSHF diet was different from that of mice fed the standard diet. Changes induced by the HSHF diet included: cell shrinkage; reduction of cell turnover; cytoplasmic vacuolar changes; blurred and indistinct cell boundaries; severe shedding of intestinal villi; scattering of damaged tissue blocks (Fig. 1F, G).

Immunohistochemical analyses showed that expression of some proinflammatory markers was affected. Expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB p65) was activated (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1H–K), whereas expression of interleukin (IL)−2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ was inhibited (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1H–K). RNA-seq of small-intestinal tissues revealed that expression of 42 RNAs was upregulated and that of 68 RNAs was downregulated (|log2FC| > 1.0, FDR < 0.05 vs. control) (Table S1, Fig. S2A). For example, expression of Hspa1a, Hspa1b, P2ry4, Enpp7, Ano3, Hsph1, Nos1ap, Slc5a12, Slc5a4a, Gm5286, Paqr9, G0s2, Trim50, Lep, Apoa2, Retnlb, Gsdmc, TCONS_00019039, Fam205a4, Gm20708, Exosc6, Pde2a and Gm10184 mRNAs was changed, and these were all related to intestinal injury/leakage, inflammation, and immunity. Pathway analysis using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database showed that the important enrichment pathways were the: “PPAR signaling pathway” (mRNA of APOA2, Acaa1b, Cyp4a10, Fabp1, Hmgcs2, Me1); “biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids”; “fructose and mannose metabolism”; “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis”; “fatty acid elongation”; “carbon metabolism”; “renin secretion”; “renin–angiotensin system”; “AMPK signaling pathway” (mRNA of G6pc, Fbp1, Srebf1, Lep). Together these results demonstrated that dysbacteriosis influenced intestinal injury/leakage, the inflammatory response, and energy metabolism. Furthermore, histopathology of the liver (Fig. S2B), kidney (Fig. S2E), spinal marrow (Fig. S2E), spleen (Fig. S2D), adipose (Fig. S2C) and heart (Fig. S2F) tissues showed that the HSHF diet not only induced dysbacteriosis, but also activated inflammation and damage to multiple organs.

The HSHF diet influences the brain cholinergic system and inflammation

The HSHF diet was administered to mice to disturb the GM. Brain sections from mice were analyzed using various stains. H&E (Fig. 2Aa, Fig. S3A–A), Nissl (Fig. 2Ab, D and Fig. S3A–B), silver (Fig. 2Ac, E and Fig. S3A–C) and TUNEL (Fig. 2B–F and Fig. S3A–D) staining showed obvious changes in pathology in mice with HSHF diet-induced dysbacteriosis: reduction in the size and turnover of neurons; cytoplasmic vacuolar changes; nerve-fiber reduction. In particular, the apoptotic percentage in the hypothalamus was increased in mice suffering from dysbacteriosis, which suggested that the appetite of HSHF-diet mice increased and bodyweight soared, as seen previously23. Immunofluorescent staining of microglia and astrocytes using antibodies to IBA-1 (Fig. 2C, G, Fig. S3B–B) and GFAP (Fig. 3A, Fig. S3B–A) showed that the number of astrocytes was reduced significantly and microglial cells were activated in mice suffering from dysbacteriosis. Expression of the cholinergic neuron of AChE (Acetylcholinesterase) (Fig. 3B, p < 0.05), Amphiphysin (AMP) (Fig. 3B, p < 0.05), Acetylcholine receptor of CHRNB1 and CHRNA1 measurement showed that the cholinergic system was affected. Expression of TNF-α (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3C) and NF-κB p65 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3C) was activated, whereas expression of PPAR-γ and IL-2 showed no obvious differences (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrated that atrophy, inflammation, or the immune response were imbalanced in the brains of mice with HSHF diet-induced dysbacteriosis.

Fig. 3. Dysbacteriosis affects brain functions and circRNA sequencing in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat for 4 months.

A Samples were stained using an immunofluorescent antibody of GFAP, see also Fig. S3B-a. B, C Dysbacteriosis implicated the cholinergic system, inflammation and immune system in the brain. D Heatmap showing different expression of circRNAs in brain samples from mice fed a diet high in sugar, see Table 1. Data are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

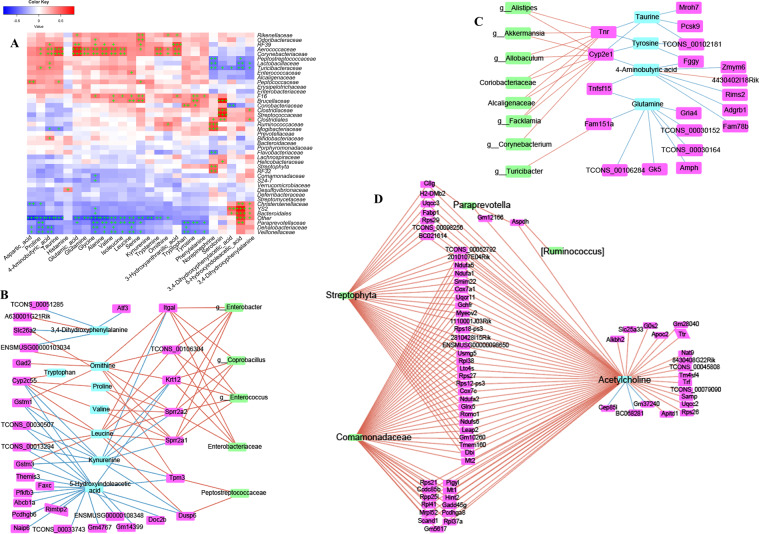

The HSHF diet accelerates circRNAs degradation in mice brains

A total of 7362 circRNAs were identified in the brains of mice fed a HSHF diet (Fig. 3). Among them, 287 differentially expressed circRNAs were in the control group vs. model group (fold change >1.50, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3D, and Table 1, circBase): expression of 88 circRNAs was upregulated, and expression of 199 circRNAs was downregulated. This finding indicated that the circRNAs had different expression profiles in slender and obese mice. Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs showed that dysbacteriosis could influence the brain in terms of metabolism, synaptic transmission and plasticity, and endogenous hormone levels. These actions would affect the activities and functions of the brain, but also affect heart function (e.g., circadian rhythm, dilated cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy). These data demonstrated that dysbacteriosis could affect brain circRNA-seq directly or indirectly.

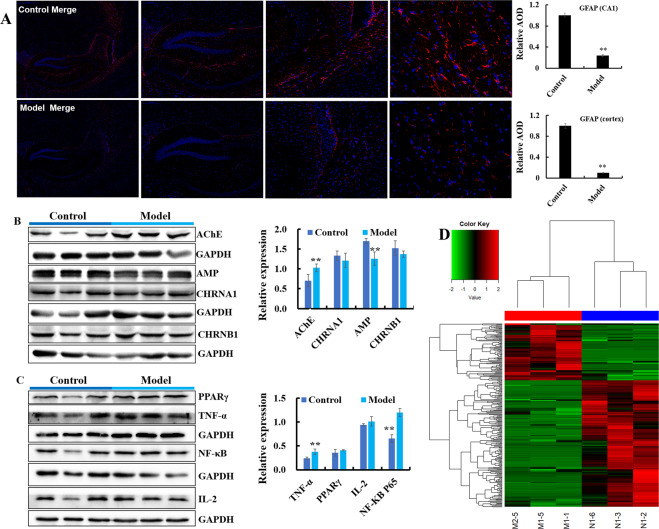

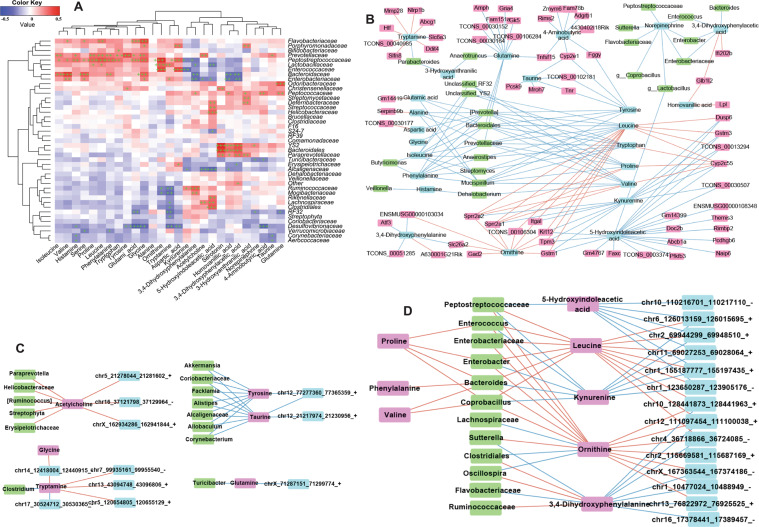

Networks interaction of the GM, neurotransmitters, intestinal mRNAs, and brain circRNAs

Network interaction of the GM and intestinal neurotransmitters

To identify the influences of the GM on neurotransmitters in the intestine, combined data analyses of the GM and neurotransmitters in fimo were done (R2 > 0.85). Some members of Aerococcaceae, Corynebacteriaceae, Brucellaceae, F16, Paraprevotellaceae, Veillonellaceae, and Dehalobacteriaceae were the key bacteria related to the production and/or secretion of neurotransmitters (Fig. 4A). They influenced proline, glycine, leucine, and serine (Fig. 4A). Phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine were influenced by bacterial in Veillonellaceae, Dehalobacteriaceae, Paraprevotellaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Brucellaceae, and F16, but how these bacteria produce them, and then participate or intervene in host metabolic pathways, merits further study.

Fig. 4. Dysbacteriosis affects neurotransmitter metabolism by targeting the gut–brain axis in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat for 4 months.

A Combined data analyses between the gut microbiota (genera) and neurotransmitters in intestine tissues. B–D Combined data analyses between the gut microbiota (genera), transcriptome (mRNA) and neurotransmitters in intestine tissues. Data are the mean ±SD of more than 8 independent experiments.

The norepinephrine level was influenced by bacteria from Streptophyta, RF23, Flavobacteriaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Turicibacteraceae, Clostridiales, Mogibacteriaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae (Fig. 4A). The 5-hydroxy tryptamine (5-HT) level was influenced by bacteria from Streptococcaceae, Helicobacteraceae, Clostridiales, Turicibacteraceae, Clostridiaceae, and Brucellaceae (Fig. 4A). The level of 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the primary metabolite of 5-HT, was influenced by bacteria from YS2, Lactobacillaceae, Turicibacteraceae, Christensenellaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Paraprevotellaceae, and Bacteroidales (Fig. 4A).

Upon combination with data for intestinal mRNAs, we found that intestinal neurotransmitters also influenced intestinal genes, and then bacteria. As shown in Fig. 4B, leucine was positive to the mRNA of glutathione S-transferase Mu 3 (Gstm3), integrin subunit alpha L (Itgal), Krt12, small proline rich protein 2 A 2 (Sprr2a2), small proline rich protein 2 A 1 (Sprr2a1), tropomyosin 3 (Tpm3), dual specificity phosphatase 6 (Dusp6), and then to bacteria from Coprobacillus, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Enterobacteriaceae, and Peptostreptococcaceae. The gene of cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily E member 1 (Cyp2e1) influenced taurine, tyrosine, and 4-Aminobutyric acid (Fig. 4C), and then became involved with the bacteria of Akkermansia, Allobaculum, Coriobacteriaceae, Alcaligenaceae, Corynebacterium Alistipes, and Facklamia (Fig. 4C). Tenascin R was involved with several types of bacteria (Fig. 4C).

Network interaction of the GM and brain neurotransmitters

The bacteria of Flavobacteriaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Desulfovibrionaceae Enterococcaceae, Prevotellaceae, Lactobacillaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae could interact with most brain neurotransmitters: isoleucine, valine, histamine, serine, proline, leucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, tyrosine, glutamic acid, 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine, kynurenine, 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid, tryptamine, glycine, and ornithine (Fig. 5A). The brain neurotransmitters homovanillic acid and 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid were influenced by bacteria from Bacteroidales, YS2, Paraprevotellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae and Bacteroidaceae (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Dysbacteriosis affects neurotransmitter metabolism by targeting the gut–brain axis in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat for 4 months.

A Combined data analyses between the gut microbiota (genera) and neurotransmitters in brain tissues. B Combined data analyses between the gut microbiota (genera), transcriptome in the intestine, and neurotransmitters in brain tissues. C, D Combined data analyses between the gut microbiota (genera), neurotransmitters, and circRNAs in brain tissues. Data are the mean ± SD of more than eight independent experiments.

The “cholinergic hypothesis” has an important role in AD therapy24. The degenerative dysfunction of cholinergic neurons is a partial cause of memory deficit in dementia patients. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in the brain was implicated with several intestinal genes (Fig. 4D, Table S1 and enrichment analysis using the KEGG database), and might be intervened and/or promoted by bacteria from Paraprevotella, [Ruminococcus], Streptophyta and Comamonadaceae (Fig. 4D). These data indicated that the GM has complex interactions with the host cholinergic system. We discovered that the norepinephrine level in the brain could: (i) influence bacteria of Peptostreptococcaceae, Sutterella, Flavobacteriaceae and Coprobacillus; interact with bacteria of Enterococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterobacter, and then interact with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; interact with bacteria from Lactobacillus, and then influence 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (Fig. 5B).

Glutamine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, leucine, tryptophan, proline and valine did not interact with a single type of bacteria (Fig. 5B). Hence, the interactions between GM, neurotransmitters, and host gene are complicated. More other complex interactions between the GM, mRNA-seq of intestinal tissue, and neurotransmitters of brain tissues are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The neurotransmitters ACh, 4-aminobutyric acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), glutamine, serotonin, leucine, and kynurenine may also have important roles in the brain–GM axis, or the GM may be indispensable for the synthesis and secretion of neurotransmitters: the exact mechanism needs much more work.

Network interaction of the GM, brain neurotransmitters, and circRNAs

Next, the interactions of the GM, neurotransmitters, and circRNAs in brain tissues were analyzed. The ACh level in brain tissues was important for the interactions between the brain circRNA of chr5_21278044/21281602_+, chrX_162934286/162941844_+ and chr16_37121798/ 37129964_−, and bacteria from Paraprevotella, Helicobacteraceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, [Ruminococcus] and Streptophyta (Fig. 5C). The neurotransmitters 5-HIAA, leucine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, kynurenine, ornithine, tryptamine, ACh, and tyrosine were the main metabolites influencing the GM and circRNAs (Fig. 5D), or they could influence multiple microorganisms and circRNAs (Fig. 5). Much more experimental evidence is needed to explain these associations.

5-HIAA is the main metabolite of 5-HT. A recent study showed that 5-HT directly stimulates and inhibits the growth of commensal bacteria in vitro, and exhibits concentration-dependent and species-specific effects25. Some bacteria may have important roles in the conversion of 5-HT to 5-HIAA. Bacteria from the family Peptostreptococcaceae could affect the mRNA of Tpm3 and Dusp6 (Figs. 4 and 5). Research has revealed a genetic proof-of-function for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) in T cells during viral infection and identified a pathway of T-cell migration that sustains antiviral immunity26. Levels of ACh and ChAT were influenced primarily by bacteria from Helicobacteraceae, Paraprevotella, [Ruminococcus], Erysipelotrichaceae, Comamonadaceae, and Streptophyta (Figs. 4 and 5). The role of the GM in TMAO byproducts from choline has been demonstrated27, and TMAO has been shown to be harmful in several diseases28. Therefore, the GM acts as a bridge to contribute to host nutrition/health by regulating the metabolism. The above-mentioned data, together with data from other studies, suggest that gut dysbacteriosis could impact circRNA sequences in the brain.

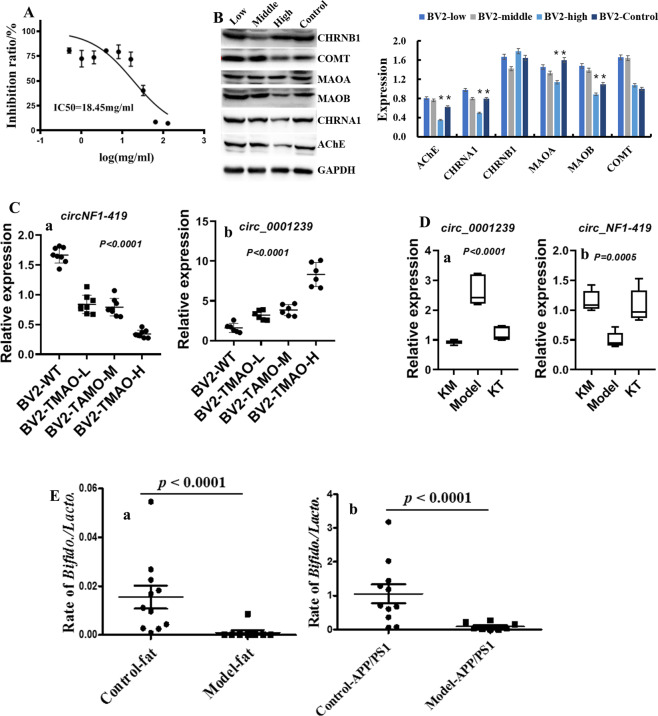

TMAO byproducts influence circRNA levels in BV2 cells

In this additional experiment, expression of some circRNAs in a murine microglial cell line (BV2) was monitored after incubation with TMAO (18.45 mg/mL) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). Expression of MAOA (Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] A), MAOB, COMT (Catechol O-methyltransferase), AChE, AMP, CHRNA1 and CHRNB1 was influenced by this concentration of TMAO (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6B), but a low concentration of TMAO did not cause obvious damage to BV2 cells. Percentage inhibition in BV2 cells did not differ at a TMAO concentration <16 mg/mL (Fig. 6A). Expression of some circRNAs, including circNF1-419 and circ_0001239, was influenced by a low concentration of TMAO (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6C), indicating that some circRNAs might be sensitive responsive signaling molecules to TMAO. These data suggested that microbial metabolites might influence the formation and degradation of host circRNAs.

Fig. 6. Effects of TMAO on BV2 cells.

A Effects of TMAO on proliferation of BV2 cells, measured using the MTT assay. B Expression of MAOA, MAOB, COMT, AChE, AMP, CHRNA1, and CHRNB1 in TMAO- damaged BV2 cells. C Expression of circNF1-419 and circ_0001239 in TMAO- damaged BV2 cells. D Expression of circNF1-419 and circ_0001239 in Kombucha tea-treated mice. E Ratio of abundance of Bifidobacterium species and Lactobacillus species was imbalanced in mice fed a HSHF diet and in AD-like mice. Data are the mean ± SD of more than five independent experiments (and three independent experiments when using western blotting). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

Levels of MAOA, MAOB, and COMT were affected after TMAO administration to BV2 cells (Fig. 6). Levels of some monoamine neurotransmitter were changed in mice fed the HSHF diet (Figs. 4 and 5). Taken together, these data suggested that behavior and stress would be influenced and, in these processes, the GM had an accelerant role. Therefore, the GM decides the transformation efficiency from choline to TMAO. The latter influences the levels of MAOA, MAOB, and COMT, which participate in the regulation of metabolism of neuroactive and vasoactive amines in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues.

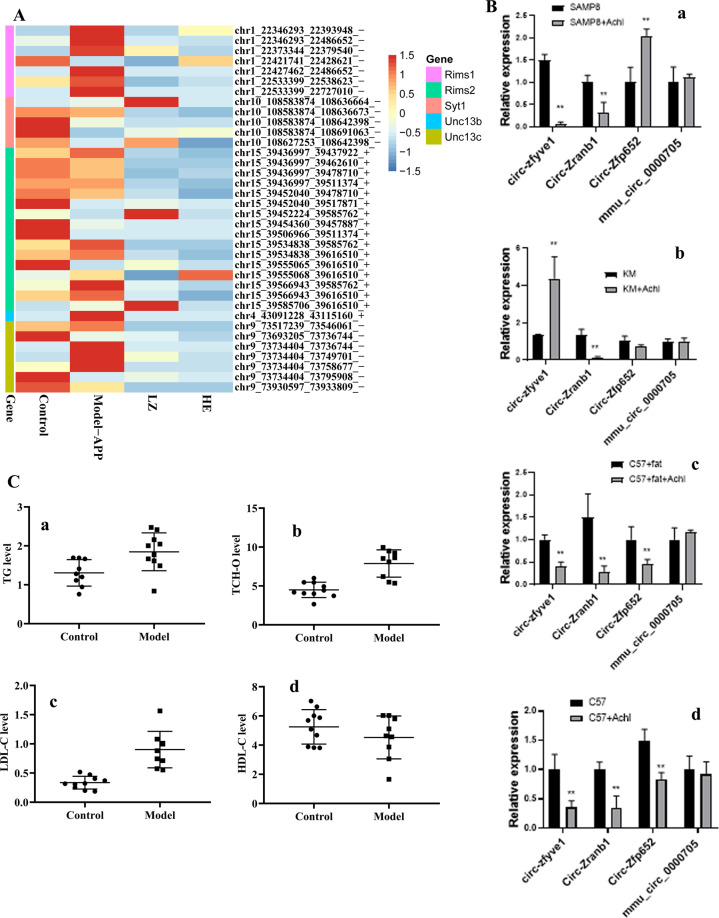

circRNAs spliced from Rims1/Syt1/Unc13b could be enriched in the ACh release cycle (Fig. 7A). Levels of some of these circRNAs were measured in the brain tissues from different mice after choline treatment. Choline and/or its metabolite could change circRNA expression (Fig. 7B), which suggested that the GM also influences the absorption and conversion of choline. Pecoraro and colleagues suggested that a high-affinity PAC1 (Proteasome assembly chaperone 1) receptor presynaptically modulates hippocampal glutamatergic transmission acting through AChE in hippocampal CA129, indicating that choline plays an important part in neurotransmitter homeostasis.

Fig. 7. Effects of choline on circRNA expression and lipid metabolism.

A Relative expression of circRNAs spliced from Rims1/Syt1/Unc13b enriched in the acetylcholine release cycle. B Expression of circRNAs in choline-treated mice using RT-qPCR. C Levels of total cholesterol (T-CHO), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in mice fed a diet high in sugar and fat. Data are the mean ± SD of more than 6 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

The GM plays an important part in the conversion rate of choline to TMAO

The GM plays an important part in lipid homeostasis in blood, and in the causes and development of nervous-system diseases. In this study, the levels of total cholesterol (T-CHO, Fig. 7Ca), triglyceride (TG, Fig. 7Cb) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL, Fig. 7Cc) were also increased (p < 0.05), and the levels of serum TMAO (Fig. 3C), when compared to the HSHF-diet group (p < 0.05), and the high-density lipoprotein (HDL, Fig. 7Cd) were decreased (p < 0.05).

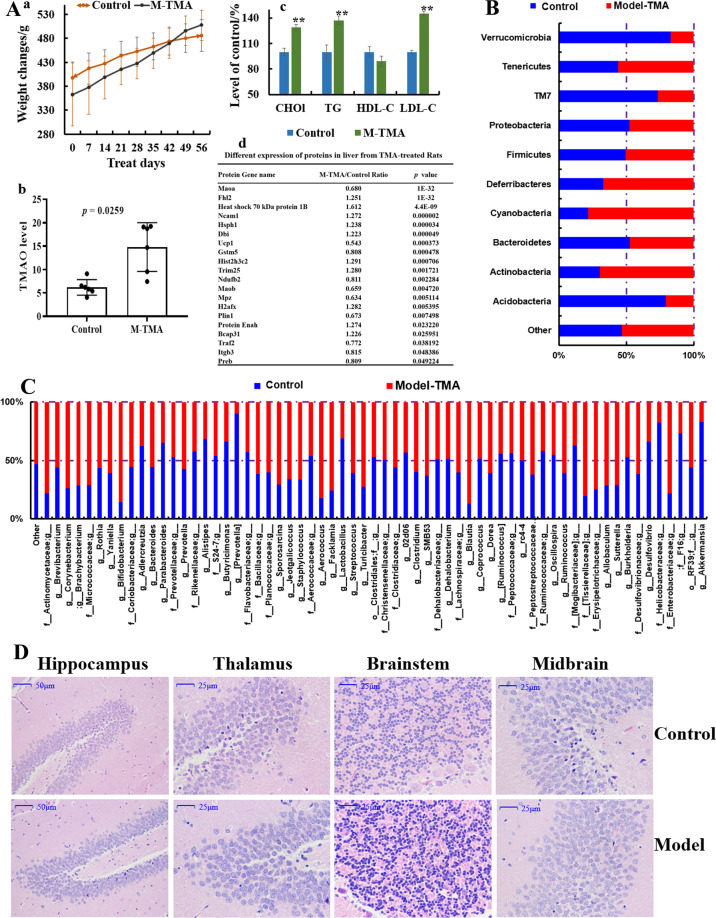

Rats treated with TMA could put on weight continuously (Fig. 8Aa), had increased levels of TMAO in serum (Fig. 8Ab) and increased levels of total T-CHO (Fig. 8Ac), TG (Fig. 8Ac) and LDL (Fig. 8Ac) (p < 0.05) when compared with those in the model group (p < 0.05), whereas the HDL content was reduced (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8Ac). Data for sequencing of the 16 S rRNA gene showed that TMA decreased the OTUs of bacteria from Verrucomicrobia, TM7 and Acidobacteria (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8B), while increasing the OTUs for bacteria from Tenericutes, Deferribacteres, Actinobacteria, and cyanobacteria (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8B). At the genus level, the OTUs of bacteria from Bifidobacterium, Aerococcus, Facklamia, Blautia and Enterobacteriace were increased by TMA administration (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8C), whereas those of bacteria from Prevotella, Lactobacillus, Helicobacteraceae and Akkermansia were decreased significantly (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8C), which indicated that excessive TMA in the diet can induce dysbacteriosis. Histopathologic changes in the hippocampus, thalamus, brainstem, and midbrain of the TMA-induced group compared with those in the control group (Fig. 8D) included cell shrinkage, cytoplasmic vacuolar changes, blurred and indistinct cell boundaries, and scattered damaged tissue blocks. Also, the differential expression of proteins in the liver from TMA-treated rats revealed that TMA induced damage in the host. For example, the level of mitochondrial brown fat uncoupling protein 1 was decreased after treatment with excess TMA, together with a decrease in Ndufb2 expression (Fig. 8Ad), which indicated that energy metabolism was imbalanced due to dysfunction of NADH dehydrogenase activity and oxidoreductase. Meanwhile, Ncam1 expression was upregulated (Fig. 8Ad), suggesting that neurite outgrowth, synaptic plasticity, as well as learning and memory might have been influenced. Increased expression of heat shock 70 kDa protein 1B and B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 (Fig. 8Ad) indicated that the host stress response was activated and immune-system function might have been compromised. In agreement with results from other studies, TMA resulted in negative consequences for the host29,30 and, in the present study, TMA led to negative consequences for the nervous system.

Fig. 8. Effects of trimethylamine (TMA) on rats.

A Effects on bodyweight changes (a), levels of T-CHO, LDL, HDL, and TG (b), levels of TMAO (c), and protein expression in liver tissues after intragastric administration of TMA at 0.2 mL/100 g/d of 2.5% for 6 weeks. B Effects on the gut microbiota at the phylum level, and (C) at genus level. D Pathologic changes in hippocampus, thalamus, brainstem, and midbrain after TMA administration. Data are the mean or mean ± SD of more than 8 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

C. albicans and K. pneumoniae influence the cholinergic system in mice

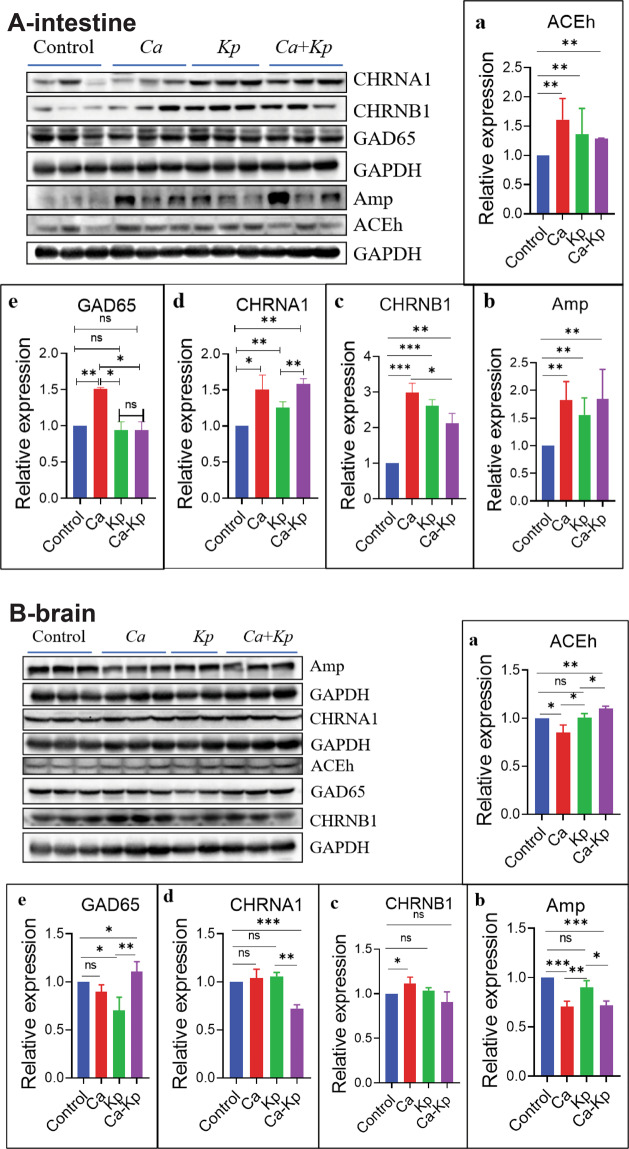

We wished to ascertain the potential routes of communication/interaction between the host and its resident bacteria with regard to neurotransmitter metabolism and brain function. C. albicans and K. pneumoniae were administered (i.g.) to normal C57 mice as monotherapy or in combination. Expression of AChE, AMP, CHRNA1, CHRNB1, and GAD65 was changed in the intestine (p < 0.05) (Fig. 9A) and brain (Fig. 9B), especially in the C. albicans-treated group in the intestine. These data indicated that changes in two core microorganisms influenced GM-mediated compounds and neurotransmitters.

Fig. 9. C.albicans and Klebsiella pneumoniae influence the cholinergic system in mice.

A Expression of AChE, AMP, CHRNA1, CHRNB1, and GAD65 were changed in the intestine (A, p < 0.05) and brain (B). Data are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. the model group by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm–Sidak test.

Discussion

Increasing numbers of studies have indicated that the GM is closely related to disorders of the nervous system, including autism31, depression32, schizophrenia33, anorexia nervosa34, multiple sclerosis35, epilepsy36, PD37, and AD18. In recent years, evidence has shown that circRNAs may be important for brain function: CDR1 is found at a high level in mammalian neurons38, and the circRNA transcripts from neuron genes can accumulate during aging in Drosophila39. Hentze and colleagues showed that circRNAs are dynamic during the activities of daily life40. Also, circRNAs are expected to be biomarkers or drug targets for neurodegenerative diseases, and studies have shown that the CDR1 level is reduced in AD38. Here, we demonstrated that gut dysbacteriosis can implicate the brain circRNA-sequencing directly or indirectly.

Previously, using in an overexpressed circNF1-419 adeno-associated virus system, we showed that circRNAs in the brain influenced the cholinergic system of the brain, and changed the GM composition, intestinal homeostasis/physiology, and even the GM trajectory in newborn mice41. Another system, circZCCHC11 (mmu_circ_0001239), showed a “sponge” miRNA function and mediated a series of chain reactions in the brain, which then influenced gut function and GM engraftment from their parent41. Those data demonstrated a link between circRNAs and the GM, enlarged the microbiome–transcriptome linkage library, and provided additional information on the gut–brain axis. Those data and the observations mentioned above indicated that the GM influences the conversion rate of choline to TMAO, and that the TMAO level influences the cholinergic system. In an additional experiment, expression of some circRNAs in the BV2 cell line was measured after incubation with TMAO, which indicated that some circRNAs might be sensitive responsive signaling molecules to TMAO. We concluded that microbial metabolites influenced the formation and degradation of host circRNAs.

Studies have demonstrated that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of biogenic and xenobiotic amines, and has important functions in the metabolism of neuroactive and vasoactive amines in the CNS and peripheral tissues. For example, MAOA preferentially oxidizes biogenic amines such as 5-HT, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. MAOB preferentially degrades benzylamine and phenylethylamine. COMT catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine to catechol substrates such as the neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, and degrades catecholamine transmitters42. All of the above-mentioned monoamine neurotransmitters have indispensable roles in the regulation of CNS functions.

We found that the levels of MAOA, MAOB, and COMT in BV2 cells were affected after TMAO administration, and that the levels of some monoamine neurotransmitters were changed in mice fed the HSHF diet. These data suggested that behavior and stress would be influenced and that, in these processes, the GM had an accelerant role. Therefore, we concluded that the GM decided the transformation efficiency from choline to TMAO. The latter then influenced the levels of MAOA, MAOB, and COMT, which participate in the regulation of metabolism of neuroactive and vasoactive amines in the CNS and peripheral tissues. How circRNAs are involved in this process merits further investigation.

A major goal of any microbiome study is to move beyond correlation, and parse out potential routes of communication/interaction between the host and its resident bacteria. To identify their communication/interaction, the species level was identified using metagenomics sequencing. Twelve species of Archaea were detected, including Methanobrevibacter sp. AbM4 (781.63-fold changes compared with control, Fig. S4A), Methanosarcina sp. MTP4 (1.21-fold, Fig. S4A), and especially Methanosalsum zhilinae, Methanomethylovorans hollandica, Candidatus Methanomethylophilus alvus, and Thermococcus cleftensis, which were new residents (Fig. S4A). Most are methanogens (anaerobic prokaryotes from the domain Archaea that utilize hydrogen to reduce carbon dioxide, acetate, and various methyl compounds to methane43). Methanogens described in the human microbiota include Euryarchaeota (including M. smithii, M. oralis, M. arbophilus, M. massiliensis, M. luminyensis, M. stadtmanae, Ca. M. alvus, and Ca. M. intestinalis44). Methanogens are emerging pathogens associated with abscesses in the brain and muscles44. They have been implicated in dysbiosis of the oral microbiota, periodontitis, and peri-implantitis43. They have also been associated with dysbiosis of the digestive-tract microbiota linked to metabolic disorders (anorexia, malnutrition, and obesity) and with lesions of the digestive tract (colon cancer)43. One clinical investigation showed that a negative association between methane concentrations in breath and anthropometric biomarkers of obesity45, and that methane significantly decreased the neurological deficit induced by cerebral ischemia and reperfusion via the antioxidant pathway of PI3K/Akt/HO-146. Special diets have been used to change anaerobic prokaryotes to involve the digestive and nervous systems47. ACh is a neurotransmitter in mammalian central and peripheral cholinergic nervous systems. However, it is also widely expressed in non-neuronal animal tissues as well as in plants, fungi, and bacteria, where it is likely involved in the transport of water, electrolytes and nutrients48. With the changes in levels of methanogens, based on histopathology, we found that the colon and brain was damaged; neurotransmitter levels were also changed.

Mycobiota are crucial for human health49. Surprisingly, a small number of species can trigger huge changes in the human body50. Dysbiosis of and invasion by mycobiota can cause disease in different parts of the body51,52. Meanwhile, the body also produces corresponding immune changes upon mycobiota infection53. Several recent studies have made a connection between intestinal mycobiota and the human immune system52,53. In HSHF-diet mice, 10 species of Eukaryota were detected. For example, the relative abundance of Kluyveromyces lactis, Leishmania major, Saccharomycetales species and Theileria orientalis was different (p < 0.05) (Fig. S4B). C. albicans is a very common yeast found in the gastrointestinal tract and oral cavity, and can occasionally cause oral-cavity ulcers. C. albicans can pass readily through the blood–brain barrier, where it can cause asymptomatic infection in the cortex, form fungal- induced glial granulomas, and cause short-term memory disorders54. Candida dubliniensis is an opportunistic fungal pathogen. Bacher and colleagues revealed that human immunity based on T-helper 17 cells against fungi is reliant on cross-reactivity against C. albicans53. Witchley and coworkers showed that programs of C. albicans morphogenesis control the balance between gut commensalism and invasive infection55. Neuronal ACh and non-neuronal ACh have been demonstrated to modulate the inflammatory response: ACh protects against C. albicans infection by inhibiting biofilm formation and promoting hemocyte function in a model of Galleria mellonella infection56. Hence, C. albicans and C. dubliniensis seem to have important roles in host immunity. In comparison with normal groups, the relative abundance of C. dubliniensis was increased (Fig. S4B), and levels of proinflammatory mediators were upregulated, upon consumption of the HSHF diet (Fig. 3). Also, in C. albicans- and K. pneumoniae-treated C57 mice, expression of AChE, AMP, CHRNA1, CHRNB1, and GAD65 were changed in the intestine (Fig. 9A) and brain (Fig. 9A), especially in the C. albicans-treated group in the intestine. These data indicated that changes in a few microorganisms could influence microbiota-mediated compounds (including neurotransmitters).

Cooperation within the GM is complex and important for human health, such as mood and bodyweight control. In most cases, the intestinal flora cooperate and influence each other. Cooperative phenotypes are thought to be at the core of microbial-community functions, including through quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance57,58. We found that with an increase in some Saccharomyces species who converted sugars to carbon dioxide and ethanol, the abundance of some methanogens was increased. The reason may have been because the metabolism of alcohol imbalances the proportion of NADH to NAD, galactose tolerance, TG synthesis, and lipid peroxidation (Figs. 3 and 7). Xu and colleagues revealed that chronic exposure to alcohol-induced GM dysbiosis, and was correlated with neuropsychic behaviors59. Furthermore, a metabolite from Saccharomyces, acetic acid, is the growth substrate of methanogens. The cooperation of these two microorganisms promotes food digestion/absorption, energy storage, and the accumulation of some harmful products60. Studies have demonstrated that the PI3K-I/Akt–mTOR signaling network can regulate anabolic processes such as the synthesis of lipids, fatty acids, and nucleotides, and requires an abundant supply of reducing power in the form of NADPH, and the growth factor-stimulated PI3K–Akt–mTORC1 signaling network61,62, and the NADPH oxidase nox can be derived by gut microbiome63.

Twenty-two species of viruses were detected (Fig. S4C). The numbers of most of them were increased in the HSHF-diet group: Aureococcus anophagefferens virus, Glypta fumiferanae ichnovirus, Chrysochromulina ericina virus, mouse mammary tumor virus, Moloney murine sarcoma virus, murine leukemia-related retroviruses, murine leukemia virus, Mus musculus mobilized endogenous polytropic provirus, RD114 retrovirus, Shamonda orthobunyavirus, Tomato spotted wilt orthotospovirus, Cyprinid herpesvirus 1, Cyprinid herpesvirus 3, Abalone herpesvirus Victoria/AUS/2009, Cadicivirus A and Lactobacillus prophage Lj771. Analyses of circRNA sequences showed that the number of circRNAs with downregulated expression was much greater than the number of circRNAs with upregulated expression in HSHF diet-group mice. An identical trend was reported by Liu and colleagues. They found that circRNAs could be degraded by RNase L if induced by polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid or infected by a virus64. Furthermore, expression of retinoic acid-inducible gene I supported the notion that too much of a HSHF diet affects immunity and increases the risk of virus invasion (p < 0.05) (Fig. S4D). Studies have revealed that Herpesvirus species are associated with AD65. Therefore, gut dysbacteriosis appears to be a critical factor in inducing changes in the circRNA-expression profile in the brain. Our results also suggest that the stability of circRNAs in terms of structure and quantity is needed for health (i.e., circRNAs may have non-negligible roles in physiological function/regulation in the organism). Also, studies have revealed that the bacteria, diet, and host genes are related to the invasion, infection degree, and drug resistance of viruses66,67.

A total of 622 species of bacteria were detected. The relative abundance of species was changed obviously in the model group (Fig. S5). Changes were observed in the abundance of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Streptococcus and Clostridium species (Figure S5A–D). With an increase of Lactobacillus prophage Lj771 abundance (Fig. S4C), the abundance of most of the species of Lactobacillus was reduced significantly, including that of L. acidipiscis, L. agilis, L. allii, L. amylophilus, L. amylovorus, L. brevis, L. coryniformis, L. fermentum, L. gasseri, L. ginsenosidimutans, L. helveticus, L. jensenii, L. johnsonii, L. kefiranofaciens, L. paraplantarum, L. pentosus, L. plantarum, L. reuteri, L. rhamnosus, L. Ruminis and L. salivarius, which were found only in the control group (Fig. S4A–D). Simultaneously, the abundance of Bifidobacterium species, including that of B. adolescentis, B. asteroids, B. bifidum, B. breve, and B. pseudocatenulatum, was also inhibited. In contrast, the abundance of most Bacteroides species was increased, including B. caccae, B. caecimuris, B. cellulosilyticus, B. dorei, B. fragilis, B. helcogenes, B. ovatus, B. salanitronis, B. Thetaiotaomicron and B. vulgatus. Phages may have been the reason why the ratio of Bifidobacterium species and Lactobacillus species was imbalanced in mice fed the HSHF diet (Fig. 6E). The abundance of Bifidobacteriaceae species and Lactobacillaceae species is crucial for homeostatic balance in the intestine. The relative abundance of Lactobacillaceae species was increased and that of Bifidobacteriaceae species was decreased in APP/PS1 mice (Fig. 6E). These data provide evidence that probiotics are beneficial for health under certain physiological conditions.

The abundance of members of the family Lachnospiraceae (Fig. S5), including Butyrivibrio hungatei, Anaerostipes hadrus, Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus, Blautia sp. YL58, Herbinix luporum, Blautia hansenii, Roseburia hominis, Lachnoclostridium phocaeense, [Clostridium] bolteae, phytofermentans, Lachnoclostridium Lachnoclostridium sp. YL32 and Pediococcus pentosaceus, was reduced in the intestinal contents of mice fed the HSHF diet (Fig. S5A–D). These Lachnospiraceae members encode a composite inositol catabolism-butyrate biosynthesis pathway, the presence of which is associated with a lower risk of host metabolic disease68. Members of the Lachnospiraceae family are among the main producers of short-chain fatty acids. Different taxa of Lachnospiraceae are also associated with different intra- and extraintestinal diseases69. Supplement the butyrate-producing Lachnospiraceae is beneficial for the intestinal barrier70, probiotic for treating stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity71, the butyrate-producing species R. inulinivorans includes strains able to grow on inulin and FOS in pure culture72. Furuya and colleagues revealed that Blautia hansenii can hydrolyze glucosylceramide to ceramide in plants73. Previously, we showed that circNF1-419 could regulate the synthesis and metabolism of ceramides, and the changed ceramides were enriched in three signaling pathways (neurotrophin, sphingolipid, and adipocytokine)41. We could conclude that the couples of Blautia and ceramide, butyrate biosynthesis bacteria, and butyrate might be one of interactions between circRNA and microbiome-gut-brain axis, but we still need much more evidence.

Peptostreptococcaceae, a family within the order Clostridiales (Fig. S5), includes the genera Peptostreptococcus, Acetoanaerobium, Proteocatella, Sporacetigenium, Filifactor, and Tepidibacter. The genera Acetoanaerobium, Sporacetigenium and Proteocatella are monospecific. Representatives of the family have different cell morphology, which varies from cocci to rods and filaments. Species of Filifactor, Proteocatella, Sporacetigenium, and Tepidibacter form endospores. All members of the family are anaerobes with have a fermentative type of metabolism. The genus Tepidibacter contains moderately thermophilic species. Members of Peptostreptococcaceae are found in different habitats, including the human body, manure, soil, and sediments. Species of Peptostreptococcus and Filifactor are components of the human oral microbiome74. Metagenomics sequencing showed that the relative abundance of Peptoclostridium acidaminophilum and Clostridioides difficile was increased in HSHF diet-fed mice. P. acidaminophilum can ferment amino acids75. C. difficile is a spore-forming, anaerobic, intestinal pathogen that causes severe diarrhea that can lead to death76. P. acidaminophilum and C. difficile had a negative correlation with expression of Tpm3 and Dusp6, and a positive correlation with expression of 5-HT and 5-HIAA, but the mechanism of action needs further analysis. Bacteria can produce a range of major neurotransmitters, and substantial evidence has accumulated around the microbiota-mediated influence of those compounds13. However, the microbiota can also influence levels of neurotransmitters, including histamine, gasotransmitters, neuropeptides, steroids, and endocannabinoids.

Conclusions

We demonstrated again that consumption of a HSHF diet-induced dysbacteriosis, damaged the intestinal tract, and changed the neurotransmitter metabolism in the intestine and brain. Our new findings were that consumption of a HSHF diet caused changes in brain function and circRNA profiles. Additional experiments found that the GM byproduct of TMAO could degrade some circRNAs, and the basal level of the GM decided the conversion rate of choline to TMAO. A change in the abundance of C. albicans and/or K. pneumoniae could influence the cholinergic system. These findings demonstrate a new link between metabolism, brain circRNAs, and the GM, enlarge the microbiome–transcriptome linkage library and provide more information on the gut–brain axis.

Study limitations

There are several strengths with this study, but there are also limitations. For example, the study lacks a rescue test with large number of single bacteria, so we have not fully identified the one-on-one communication/interaction mechanism between neurotransmitter, circRNA and single bacteria, and therefore could not find the signaliccgeted strains in germ-free mice with multi-omics studies to reveal the interaction of neurotransmitter and circRNAs on the microbiome-gut-brain axis, or knock-out mice are needed in the future for positive validations.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-IBA-1 | Proteintech | 10904-1-AP |

| Anti-GFAP | Proteintech | 20746-1-AP |

| Anti-AchE | Proteintech | 17975-1-AP |

| Anti-AMP | Proteintech | 13379-1-1P |

| Anti-CHRNA1 | Proteintech | 10613-1AP |

| Anti-CHRNB1 | Proteintech | 11553-1-AP |

| Anti-PPAR-γ | Proteintech | 11643-1-AP |

| Anti-TNF-α | Abcam | GR168358-1 |

| Anti-NF-κB p65 | Abcam | 16502 |

| Anti-IL-2 | Proteintech | 60306-1-Ig |

| Anti-MAOA | Proteintech | 10539-1-AP |

| Anti-MAOB | Proteintech | 12602-1-AP |

| Anti-COMT | Proteintech | 14754-1-AP |

| Anti-RIG-I | Affinity | DF6107 |

| β-Actin (13E5) | CST | 4970S |

| GAPDH | Abcam | GR3207992-4 |

| Chemicals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hematoxylin | Servicebio | G1004 |

| Eosin | Servicebio | G1001 |

| Color separation solution | Servicebio | G1039 |

| Diaminobenzidine (DAB) | Servicebio | G1212 |

| Goat anti-rabbit lgG(H + L) HRP | Affinity | S0001 |

| Citrate buffer pH 6.0 | Servicebio | G1202 |

| Anhydrous ethanol | Guangzhou Guanghua Sci-Tech co., Ltd | 1.17113.023 |

| Penicillin streptomycin solution | CORNING | 30002304 |

| Phosphate-buffer saline | CORNING | 19117004 |

| Fetal bovine serum | Gibco | 1932595 |

| Trimethylamine N-Oxide anhydrous | TOKYO CHEMICAL INDUSTRY CO., LTD | 3EVJG-TN |

| 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (1×) | Gibco | 2042337 |

| DMEM basic (1×) | Gibco | 8119090 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

|---|---|---|

| LDL-C Kit | Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute | 20180512 |

| HDL-C Kit | Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute | 20180508 |

| TG Kit | Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute | 20180609 |

| T-CHO Kit | Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute | 20190523 |

| ACH Kit | Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute | 20190505 |