Key Points

Question

Are there racial/ethnic disparities in access to the diabetic eye examination in patients with pediatric diabetes?

Findings

In this cohort study of 149 participants, minority youths were less likely to report a previous diabetic eye examination (non-White individuals, 46% vs White individuals, 85%), yet more likely to have diabetic retinopathy (15% vs 3%).

Meaning

This study suggests that implementation of point-of-care diabetic retinopathy screening in the diabetes care setting can improve access to and mitigate racial/ethnic disparities for the diabetic eye examination.

This cohort study examines disparities in diabetic retinopathy eye examination completion rates by race/ethnicity and evaluates barriers in those who had not had undergone examination.

Abstract

Importance

Diabetic retinopathy is a major complication of diabetes for which regular screening improves visual health outcomes, yet adherence to screening is suboptimal.

Objective

To assess disparities in diabetic eye examination completion rates and evaluate barriers in those not previously screened.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cohort study at a single academic center (Johns Hopkins Hospital pediatric diabetes center in Baltimore, Maryland) from December 2018 to November 2019, youths with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who met criteria for diabetic retinopathy screening and were enrolled in a prospective observational trial implementing point-of-care diabetic retinopathy screening were asked about prior diabetic retinopathy screening.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between those who did and did not have a previous diabetic eye examination and stratified according to race/ethnicity, using t tests and χ2 tests. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the association between race/ethnicity, screening, and other social determinants of health. A questionnaire assessing barriers to screening adherence was administered.

Results

Of 149 participants (76 male patients [51.0%]; mean [SD] age, 14.5 [2.3] years), 51 (34.2%) had not had a prior diabetic eye examination. These individuals were more likely than those who had prior diabetic eye examinations to be non-White youths (38 [75%] vs 31 [32%]; P < .001) and have type 2 diabetes (38 [75%] vs 10 [10%]; P < .001), Medicaid or public insurance (43 [84%] vs 31 [32%]; P < .001), lower household income (annual income ≤$25 000, 21 [41%] vs 9 [9%]; P < .001), and parents with education levels of high school or less (29 [67%] vs 22 [35%]; P < .001). The main barriers reported included not recalling being recommended to obtain a diabetic eye examination (19 [56%]), difficulty finding time for an additional appointment (10 [29%]), and transportation issues (7 [20%]). Minority youths were less likely to have a previous diabetic eye examination (non-White, 34 [46%] vs White, 64 [85%]; P < .001) and more likely to have diabetic retinopathy (11 [15%] v 2 [3%]; P = .008). Minority youths were less likely to get diabetic eye examinations even after adjusting for insurance, household income, and parental education level (odds ratio, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.10-0.79]; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, non-White youths were less likely to undergo diabetic eye examinations yet more likely to have diabetic retinopathy compared with White youths. Addressing barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening may improve access to diabetic eye examination and facilitate early detection.

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of blindness in young adults in the US.1 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Academy of Ophthalmology recommend regular DR screening examinations for youths with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes (T2D).2 However, adherence to screening remains low, especially among racial/ethnic minority and less affluent youths, with studies reporting that up to 50% of youths have never had a diabetic eye examination.3,4 Barriers to diabetic eye examinations in adults have been explored and include lack of access, knowledge, time, and financial resources,5,6,7 but data from pediatric populations are limited.

In 2018, our team implemented point-of-care DR screening using a nonmydriatic fundus camera with autonomous artificial intelligence technology.4 We assessed for disparities in prior diabetic eye examination completion and evaluated barriers faced by those who were not previously screened. We hypothesized that implementation of point-of-care diabetic eye examinations would improve screening rates.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Johns Hopkins Hospital pediatric diabetes center in Baltimore, Maryland,4 from December 2018 to November 2019 and enrolled participants aged 5 to 21 years with type 1 diabetes, T2D, or cystic fibrosis–related diabetes. At the time this study was initiated, screening for the diabetic eye examination was based on 2018 ADA guidelines.8 This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital institutional review board. Written parental informed consent was obtained for all participants 17 years and younger, and written informed consent was obtained directly from participants aged 18 to 21 years. No participant compensation was provided. Participants were asked if they had completed a diabetic eye examination in the past, which was cross-referenced with their medical record. Participants’ clinical data were extracted from their medical records. Race/ethnicity, household income, and parental education were self-reported by parents or participants aged 18 to 21 years. Race/ethnicity categories included Black, Hispanic, White, and other (which in this study included individuals reporting mixed race/ethnicity and Asian backgrounds).

Caregivers of participants without a prior diabetic eye examination were contacted with a brief questionnaire via telephone to assess barriers to the diabetic eye examination. The questionnaire was based on prior surveys assessing barriers to health care utilization5,6,9,10 and adapted to include 5 questions pertaining to transportation, costs, time, childcare, and information (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics between subgroups were analyzed using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical data. The association between screening completion and race/ethnicity was assessed using multivariate logistic regression, controlling for household income, parental education, and insurance type as possible confounders. Data were collected from December 2018 to November 2019. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp). Statistical significance was assessed at the P < .05 level.

Results

Of the 149 participants who met screening criteria for the diabetic eye examination (76 male patients [51.0%]; mean [SD] age, 14.5 [2.3] years), 51 (34.2%) were identified as having no prior diabetic eye examination. Compared with those who did have eye examinations, they were more likely to be non-White youths (which included Black, Hispanic, and individuals of other races/ethnicities [4 individuals of mixed background and 1 Asian individual]) (38 [75%] vs 31 [32%]; P < .001) and have T2D (38 [75%] vs 10 [10%]; P < .001), Medicaid or public insurance (43 [84%] vs 31 [32%]; P < .001), lower household income (annual income ≤$25 000, 21 [41%] vs 9 [9%]; P < .001), and parents with education levels of high school or less (29 [67%] vs 22 [35%]; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Those Who Completed Diabetic Eye Examinationsa.

| Variable | Participants with previous eye examination, No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), %b | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| No. of patients | 51 (34) | 98 (66) | NA | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 14.2 (2.3) | 14.7 (2.3) | −0.49 (−1.28 to 0.28) | .21 |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 12.5 (3.9) | 7.7 (3.8) | 4.76 (3.45 to 6.07) | <.001 |

| Duration of diabetes, mean (SD), y | 2.1 (2.5) | 7.3 (3.8) | −5.3 (−6.51 to −4.15) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20 (39) | 56 (57) | −17.9 (−34.5 to −1.3) | .04 |

| Female | 31 (61) | 42 (43) | 17.9 (1.3 to 34.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 11 (22) | 64 (65) | −43.7 (−58.4 to −29.0) | <.001 |

| Black | 32 (63) | 29 (30) | 33.1 (17.0 to 49.2) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (12) | 2 (2) | 9.8 (NA) | |

| Otherc | 2 (4) | 3 (3) | 0.8 (NA) | |

| Type of diabetesd | ||||

| Type 1 | 12 (24) | 88 (90) | −66.3 (−79.4 to −53.2) | <.001 |

| Type 2 | 38 (75) | 10 (10) | 64.3 (50.9 to 77.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (NA) | |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD), % | 8.5 (2.5) | 9.4 (2.2) | −0.87 (−1.67 to −0.07) | .03 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %e | ||||

| <7.5 | 21 (44) | 15 (16) | 25.9 (10.6 to 41.2) | <.001 |

| ≥7.5 | 27 (56) | 82 (85) | −30.8 (−46.3 to −15.3) | |

| Insulin form | ||||

| Injection | 26 (51) | 35 (36) | 15.3 (−1.4 to 32.0) | <.001 |

| Pump | 8 (16) | 60 (61) | −45.5 (NA) | |

| Not taking insulin | 17 (33) | 3 (3) | 30.2 (NA) | |

| Continuous glucose monitorf | 5 (42) | 57 (65) | −23.1 (NA) | .12 |

| Metforming | 30 (79) | 9 (90) | −11.1 (NA) | .43 |

| Insurance type (n = 148) | ||||

| Medicaid or public | 43 (84) | 31 (32) | 52.7 (NA) | <.001 |

| Private or commercial | 7 (14) | 67 (68) | −54.7 (NA) | |

| Parental education (n = 137) | ||||

| ≤High school | 29 (67) | 33 (35) | 23.2 (6.7 to 39.7) | <.001 |

| >High school | 14 (33) | 61 (65) | −34.7 (−50.3 to −19.1) | |

| Income/y, $ | ||||

| ≤25 000 | 21 (41) | 9 (9) | 32 (NA) | <.001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 7 (14) | 18 (18) | −4.7 (NA) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 5 (10) | 10 (10) | −0.4 (NA) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 3 (6) | 8 (8) | −2.3 (NA) | |

| >100 000 | 1 (2) | 37 (38) | −35.8 (NA) | |

| Did not know or chose not to answer | 14 (28) | 16 (16) | 11.2 (−3.1 to 25.5) | |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factor: To convert hemoglobin A1c to a proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01.

We used t tests to compare continuous variables between groups and χ2 tests for categorical variables; P values were 2-sided and not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The 95% CIs were omitted for all comparisons not large enough to meet normality assumptions.

The Other racial/ethnic category included Asian individuals (n = 1) and those of mixed race/ethnicity (n = 4).

One patient with diabetes of uncertain type was not included.

HemoglobinA1c values were unknown for 4 participants.

Percentage of those with type 1 diabetes.

Percentage of those with type 2 diabetes.

When we examined participants by racial grouping (White vs non-White, which included Black, Hispanic, Asian youths and youths of mixed race/ethnicity), we found minority youths were less likely to have a previous diabetic eye examination (34 [46%] vs 64 [85%]; P < .001) and more likely to have DR (11 [15%] v 2 [3%]; P = .008) (Table 2). Non-White youths had a shorter duration of diabetes (mean [SD] time, 4.2 [4.1] years vs 6.9 [4.0] years; P < .001), and this was driven by the large proportion of youths with T2D (40 [54%] vs 8 [11%]; P < .001), since 83% of participants with T2D were non-White. Non-White youths were less likely to use insulin pumps (17 [23%] vs 51 [68%]; P < .001) and continuous glucose monitors (15 [46%] vs 47 [70%]; P = .02) and more likely to have Medicaid insurance (57 [77%] vs 17 [23%]; P < .001), parents whose education level was less than high school (44 [60%] vs 18 [24%]; P < .001), and lower household income (eg, ≤$25 000: 24 [32%] vs 6 [8%]; P < .001).

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of Participants Who Met Screening Criteria for the Diabetic Eye Examination, by Race/Ethnicity.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), %a | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Non-Whitec | |||

| No. | 75 | 74 | NA | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 14.4 (2.4) | 14.7 (2.1) | −0.30 (−1.05 to 0.44) | .42 |

| Duration of diabetes | 6.9 (4.0) | 4.2 (4.1) | −3.02 (−4.38 to −1.66) | <.001 |

| Type of diabetesd | ||||

| Type 1 | 67 (89) | 33 (45) | 44.7 (NA) | <.001 |

| Type 2 | 8 (11) | 40 (54) | −43.4 (NA) | |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD), % | 8.8 (1.8) | 9.3 (2.7) | −0.52 (−1.28 to 0.24) | .18 |

| Previous screening | 64 (85) | 34 (46) | 39.4 (25.5 to 53.3) | <.001 |

| Prevalence of retinopathy | 2 (3) | 11 (15) | −12.2 (NA) | .008 |

| Insulin form | ||||

| Injection | 20 (27) | 41 (55) | −28.7 (−43.8 to −13.6) | <.001 |

| Pump | 51 (68) | 17 (23) | 45.0 (30.7 to 59.3) | |

| Not taking insulin | 4 (5) | 16 (22) | −16.3 (NA) | |

| Continuous glucose monitore | 47 (70) | 15 (46) | 24.6 (4.4 to 44.8) | .02 |

| Metforminf | 5 (65) | 34 (85) | −22.5 (NA) | .14 |

| Insurance type (n = 148) | ||||

| Medicaid or public | 17 (23) | 57 (77) | −54.3 (−67.8 to −40.8) | <.001 |

| Private or commercial | 58 (77) | 16 (22) | 55.7 (42.4 to 69.0) | |

| Parental education (n = 137) | ||||

| ≤High school | 18 (24) | 44 (60) | −35.5 (−50.3 to −20.7) | <.001 |

| >High school | 54 (72) | 21 (28) | 43.6 (29.1 to 58.1) | |

| Income/y, $ | ||||

| ≤25 000 | 6 (8) | 24 (32) | −24.4 (NA) | <.001 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 5 (7) | 20 (27) | −20.3 (NA) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 9 (12) | 6 (8) | 3.9 (NA) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 10 (13) | 1 (1) | 11.9 (NA) | |

| >100 000 | 33 (44) | 5 (7) | 37.2 (NA) | |

| Did not know or chose not to answer | 12 (16) | 18 (24) | −8.3 (−21.1 to 4.5) | |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factor: To convert hemoglobin A1c to a proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01.

The 95% CIs were omitted for all comparisons not large enough to meet normality assumptions.

P values were 2-sided and not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Non-White individuals included Black, Hispanic, and Asian individuals and those of mixed race/ethnicity.

One patient with diabetes of uncertain type not included.

Percentages of those with type 1 diabetes.

Percentages of those with type 2 diabetes.

Multivariate regression analysis evaluating social determinants of health on DR screening showed that after adjusting for insurance, income, and education, non-White youths were less likely to have DR screening (odds ratio, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.10-0.79]; P = .02). When adjusting for diabetes duration in this model, youths with Medicaid or public insurance were still less likely to get screened (odds ratio, 0.12 [95% CI, 0.02-0.67]; P = .02).

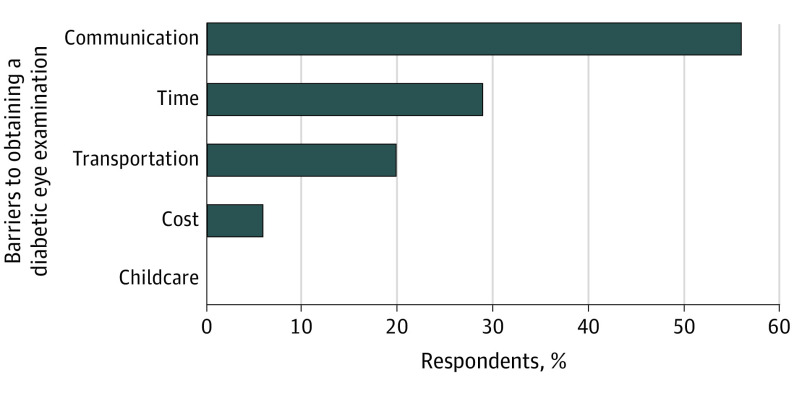

Following the point-of-care DR examinations, we contacted the participants without prior eye examinations with a brief survey to determine barriers, and 34 of 51 responded. As shown in the Figure, the respondents (parents of patients 17 years and younger and patients aged 18 years or older) reported transportation issues (7 [20%]), cost or insurance coverage issues (2 [6%]), difficulty finding time for another clinical visit (10 [29%]), and not recalling the recommendation to obtain a diabetic eye examination (19 [56%]). Open-ended responses revealed common themes: confusion between routine eye care and the diabetic eye examination, language barriers to scheduling the eye visit, and patients with recently diagnosed T2D who had not yet scheduled the diabetic eye examination.

Figure. Reported Barriers to Diabetic Retinopathy Screening.

Of 34 respondents, 19 (56% [95% CI, 37%-73%]) reported communication issues, 10 (29% [95% CI, 15%-48%]) reported time constraints, 7 (20% [95% CI, 87%-38%]) reported transportation issues, and 2 (6% [95% CI, 1%-20%]) reported cost issues as barriers to undergoing a diabetic eye examination.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that minority youths were less likely to get diabetic eye examinations and were more likely to have DR. Similar to other studies,11,12 we found disparities in technology use (continuous glucose monitors and pumps) and diabetes-associated outcomes.

Over the last decade, there has been a rise in the prevalence of T2D in youths,13 which disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minority youths and youths of lower socioeconomic status, who are at higher risk of developing DR.14,15 Similar to findings from a large US managed care network, we also show that minority youths and those with public insurance were less likely to adhere to screening guidelines.3 We further showed that youths with T2D were less likely to have had a diabetic eye examination. In this study, more than 50% of the non-White cohort was made up of youths with T2D, and this accounts for the shorter recorded duration of diabetes in this group; DR screening is recommended at the time of the diagnosis with T2D. Social determinants of health in this population are interconnected, and after controlling for these variables and duration, public insurance remained associated with DR screening nonadherence.

One of the main barriers reported by participants without prior DR screening was not receiving a recommendation to obtain a diabetic eye examination. Most practices, including our own, follow the ADA and American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines for DR screening and recommend them routinely. However, similar to prior studies in adults, miscommunication was a factor, in that participants did not recall the eye examination being recommended,5 as well as confusion between routine eye care and the diabetic eye examination.5 This reiterates the need to clearly recommend a diabetic eye examination and discuss differences from routine eye care.

Children with diabetes are seen quarterly per ADA and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes guidelines,2 and thus caregivers reported that it was difficult to find time for an additional appointment. Point-of-care DR screening can mitigate this barrier, as it did in our center, where screening adherence in the cohort of study participants improved from 49% to 95%.4 Transportation issues were cited as a barrier by 20% of those surveyed at our center but has not been reported as a major barrier in studies of adults.10 While the setting for this study was urban, where there is access to public transportation, transportation may be a larger barrier in rural populations. Furthermore, clinicians treating pediatric diabetes should place an additional focus on making sure patients with public insurance and lower household income levels can access DR screening.

Limitations

While this study population is diverse, it is limited by the single-site recruitment and modest sample size and thus may not be generalizable to other cohorts. Additionally, the barriers’ assessment was performed after screening was complete and not all patients responded to the survey, creating the potential for recall bias and selection bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, minority youths and those with public insurance were less likely to undergo recommended screenings, and understanding barriers to screening may help guide strategies to improve equitable access to care. Point-of-care DR examinations integrated in the diabetes clinic may help improve adherence to ADA-recommended screening guidelines, particularly in high-risk populations.

eAppendix. Barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening questionnaire

References

- 1.Lueder GT, Silverstein J; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology and Section on Endocrinology . Screening for retinopathy in the pediatric patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):270-273. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association . 13, Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S163-S182. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang SY, Andrews CA, Gardner TW, Wood M, Singer K, Stein JD. Ophthalmic screening patterns among youths with diabetes enrolled in a large us managed care network. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(5):432-438. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf RMLT, Liu TYA, Thomas C, et al. The SEE study: safety, efficacy and equity of implementing autonomous artificial intelligence for diagnosing diabetic retinopathy in youth. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(3):781-787. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham-Rowe E, Lorencatto F, Lawrenson JG, et al. Barriers to and enablers of diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: a systematic review of published and grey literature. Diabet Med. 2018;35(10):1308-1319. doi: 10.1111/dme.13686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashim RM, Newton P, Ojo O. Diabetic retinopathy screening: a systematic review on patients’ non-attendance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(1):E157. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15010157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartnett ME, Key IJ, Loyacano NM, Horswell RL, Desalvo KB. Perceived barriers to diabetic eye care: qualitative study of patients and physicians. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(3):387-391. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association . 13, Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S148-S164. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pichert JW, Briscoe VJ. A questionnaire for assessing barriers to healthcare utilization: part I. Diabetes Educ. 1997;23(2):181-184, 187-188, 190-191. doi: 10.1177/014572179702300209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Y, Serpas L, Genter P, Anderson B, Campa D, Ipp E. Divergent perceptions of barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening among patients and care providers, Los Angeles, California, 2014-2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E140. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahkoska AR, Shay CM, Crandell J, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with glycemic control and hemoglobin A1c levels in youth with type 1 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e181851. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. ; T1D Exchange Clinic Network . Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):424-434. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, et al. ; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study . Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1419-1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabelea D, Stafford JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al. ; SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Research Group . Association of type 1 diabetes vs type 2 diabetes diagnosed during childhood and adolescence with complications during teenage years and young adulthood. JAMA. 2017;317(8):825-835. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group TS; TODAY Study Group . Retinopathy in youth with type 2 diabetes participating in the TODAY clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1772-1774. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Barriers to diabetic retinopathy screening questionnaire