Abstract

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) ultimately develop drug resistance and metastasis. Therefore, there is a need to identify the underlying mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-TKIs. In the present study, colony formation and MTT assays were performed to investigate cell viability following treatment with icotinib. Gene Expression Omnibus datasets were used to identify genes associated with resistance. Wound healing and Transwell assays were used to detect cell migration and invasion with icotinib treatment and integrin α5-knockdown. The expression levels of integrin α5 and downstream genes were detected using western blotting. Stable icotinib-resistant (IcoR) cell lines (827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR) were established that showed enhanced malignant properties compared with parental cells (HCC827 and PC9). Furthermore, the resistant cell lines were resistant to icotinib in terms of proliferation, migration and invasion. The enrichment of function and signaling pathways analysis showed that integrin α5-upregulation was associated with the development of icotinib resistance. The knockdown of integrin α5 attenuated the migration and invasion capability of the resistant cells. Moreover, a combination of icotinib and integrin α5 siRNA significantly inhibited migration and partly restored icotinib sensitivity in IcoR cells. The expression levels of phosphorylated (p)-focal adhesion kinase (FAK), p-STAT3 and p-AKT decreased after knockdown of integrin α5, suggesting that FAK/STAT3/AKT signaling had a notable effect on the resistant cells. The present study revealed that the integrin α5/FAK/STAT3/AKT signaling pathway promoted icotinib resistance and malignancy in IcoR NSCLC cells. This signaling pathway may provide promising targets against acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI in patients with NSCLC.

Keywords: icotinib resistance, integrin α5, migration, invasion, metastasis

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in the world. Out of patients over 50-years-old, ~1/5 are suffering from lung cancer in 2016 (1). It is also one of the most aggressive malignancies, in which the mortality is predicted to increase by 2.53-fold by 2060 worldwide (2). Smoking is the predominant risk factor for lung cancer development (3). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of lung cancer cases in the USA (4). The 5-year survival rate of early-stage NSCLC without metastasis is ~50%, whereas the rate in advanced NSCLC with multiple metastases is only 1–2% in Asia (5). Therefore, metastasis is a notable factor in the poor prognosis of NSCLC.

The treatment of advanced, metastatic NSCLC remains a challenge in the clinic. Due to the guidance of driver genes, targeted therapies, such as EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), can extend the overall survival time (OS) of patients based on the mutation status of oncogenes (6–9). However, EGFR-TKI acquired resistance has emerged as a barrier to effective clinical treatments (10).

To overcome EGFR-TKI resistance, several drug resistance mechanisms have been studied, including secondary mutations (T790M and C797S), aberrant downstream signaling pathways (K-RAS mutations and loss of PTEN), activation of alternative signaling pathways (hepatocyte growth factor receptor and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor) and the impairment of the EGFR-TKIs-mediated apoptosis pathway (BCL2-like 11/BIM deletion polymorphism) (11–20).

Tumor cells that are resistant to drugs also tend to be more aggressive and have increased migration and invasion capability compared with non-resistant parental cells. Also, a majority of secondary tumors are more resistant to chemotherapy drugs compared with primary tumors (21). Studies have shown that platinum-resistant cells are more susceptible to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which increases metastatic potential (22–24). Tamoxifen promotes estrogen receptor α36 expression and breast cancer metastasis by upregulating aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1 member A1 (25). It has been reported that distant metastases reduce the efficacy of TKIs in patients with mutant EGFR who receive first-line treatment of EGFR-TKIs. Patient outcomes may be worse if pathway genes are co-mutated in the PI3K catalytic subunit α isoform or the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which contributes to drug resistance and distant metastasis (26). Patients with multiple systemic metastases often have multiple resistance-related mechanisms such as HER2 amplification, EGFR-L858R mutation and EGFR-T790M mutation (27). Studies suggest that patients with EGFR-TKI resistance are more susceptible to metastasis (28–30). However, the mechanisms of EGFR-TKI resistance that are responsible for the promotion of metastasis remain to be fully determined. Considering the challenges of extending the OS of patients and delaying the relapse of drug resistance, identifying the underlying molecular mechanisms associated with metastasis after EGFR-TKI resistance are needed for the development of novel EGFR-TKIs-based therapies and EGFR-targeting agents.

Icotinib is an oral and safe first-generation TKI that can significantly improve progression-free survival in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutations (31). The present study established icotinib-resistant (IcoR)-NSCLC cells and found that their malignant abilities were significantly increased compared with their respective parental cells. Furthermore, integrin α5 was screened and shown to be a key molecule in promoting migration and invasion rather than by contributing to icotinib resistance of proliferation.

The present study showed that clinical treatments could aim to block the integrin α5-FAK/STAT3/AKT signaling pathway as a synergistic treatment to EGFR-TKIs. Inhibiting the expression of integrin α5 may help to improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients with EGFR-TKI resistance.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Icotinib was gifted from Zhejiang Beta Pharma, Co. Ltd. and was prepared in 5% dimethyl sulfoxide to obtain a stock solution of 10 mM at −20°C. Stattic (cat. no. ab120952) was obtained from Abcam, used in western blot as an inhibitor of STAT3. Anti-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. #9272S), anti-phosphorylated (p)-AKT (1:500; cat. no. #9271L, Ser473), anti-p-ERK (1:1,000; cat. no. #4370S, Thr202/Tyr204), anti-SRC (1:1,000; cat. no. #2110S), anti-p-SRC (1:500; cat. no. #6943S), anti-FAK (1:1,000; cat. no. #3285S), anti-p-FAK (1:250; cat. no. #3284, Y925), anti-STAT3 (1:1,000; cat. no. #132L), anti-p-STAT3 (1:1,000; cat. no. #9131L, Tyr705) anti-EGFR (1:1,000; cat. no. #2646S), anti-p-EGFR (1:500; cat. no. #2234S, Tyr1068) and anti-integrin α5 (1:500; cat. no. #4705) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Anti-integrin β4 (1:1,000; cat. no. MAB4060) was purchased from Novus Biologicals, Ltd. Anti-ERK (1:2,000; cat. no. sc292838), anti-actin (1:1,000; cat. no. sc1616), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit (cat. no. sc-sc-2004, targeting anti-AKT, p-AKT, p-ERK, p-SRC, FAK, p-FAK, STAT3, p-STAT3, EGFR, p-EGFR, integrin α5 and ERK) and goat anti-mouse antibodies (cat. no. sc-sc-2005, targeting anti-SRC, integrin β4 and actin) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Cell culture and establishment of IcoR cells

Human lung adenocarcinoma cells, PC9 and HCC827, were obtained from The Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. containing 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Industries), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) at 37°C in an humidified atmosphere with 95% air and 5%CO2. Resistant cells were established by exposing to 0.05 µM icotinib at the beginning and the icotinib concentration was gradually increased in the totally same incubator condition as previously mentioned. Finally, the PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR cells were maintained at 10 and 5 µM icotinib, respectively.

MTT assay

The effect of icotinib on the cell viability was evaluated using an MTT assay. PC9 and HCC827 cells (3,000 or 5,000 cells/well) in 96-well plate were treated with different concentration of icotinib for 24 or 48 h. A total of 20 µl of the MTT reagent (5 mg/l) was added per well and incubated for another 4 h. The supernatant was removed and 200 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an iMark Absorbance Microplate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Colony formation assay

A colony formation assay was used to estimate the ability of cell proliferation. PC9, PC9/IcoR, HCC827 and 827/IcoR cells at a density of 400 or 600/well in six-well plate were treated with different concentrations of icotinib (0, 0.1, 1 and 10 µM) for 72 h at 37°C. Then, the supernatant of the medium was discarded and the cells were cultured under the aforementioned routine conditions for another 7 days. Subsequently, the colonies were fixed with 95% ethanol for 5 min at room temperature, stained with Wright-Giemsa (Wright staining for 1 min and Giemsa staining for 25 min at room temperature). Only colonies containing >50 cells were counted were counted under an optical microscope (BX41; Olympus Corporation) with white light by eye.

Small interfering (si)-RNA transfections

To knockdown the expression of integrin α5, siRNAs targeting integrin α5 (si-integrin α5) and a scrambled negative control (NC) were transfected into PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR cells were transfected with 0.1 mM siRNAs using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) reagent according to manufacturer's instruction at 37°C. After 48 h, subsequent experiment was performed. The coding strand of ITGA5 si1 was 5′-GUUUCACAGUGGAACUUCA-3′, and ITGA5 si2 was 5′-GCAGUGCUAUUCCCAGUAA-3′. The coding strand of NC was 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′.

Wound healing assay

Cells (HCC827, PC9, 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR) in six-well plate were scratched with 200-µl pipet tips. After being washed with PBS two or three times, 0 and 5 µmol/ml icotinib (for HCC827 and 827/IcoR) or 10 µmol/ml icotinib (for PC9 and PC9/IcoR) was added with RPMI-1640 medium containing 2% FBS onto the plate. The scratches were observed using the CK40 inverted light microscope (Olympus Corporation) and images were captured at 0 and 24 h and the wound width was measured using ImageJ version 1.52a (National Institutes of Health). The healing rate was evaluated relative to the starting wound width (0 h time point).

Transwell assay

The migration assay was performed using 8-µm Transwell chambers (Corning, Inc.). PC9 or PC9/IcoR cells with a density of 3×104 cells/200 µl and HCC827or 827/IcoR cells with a density of 8×104 cells/200 µl were placed into the upper chamber, and 500 µl of RPMI-1640 medium containing 2.5% FBS was added to the lower chamber with 37°C. After 24 h, the remaining cells on the upper membrane were removed with a cotton swab and cells that migrated to the bottom of the membranes were stained with Wright-Giemsa staining (Wright staining for 1 min and Giemsa staining for 25 min at room temperature). Next, four randomly selected fields were counted using the BX41 microscope with white lights and the average mean number of cells was presented. Images were also captured. The invasion assay used the same steps as the migration assay except for inserting 3% Matrigel into the upper chamber before seeding 3×104 cells into the culture system. The Matrigel was diluted to a 1:30 ratio at 4°C and solidified at 37°C for 4 h, then the cells were seeded into the upper chamber at 37°C for 24 h.

Western blotting

HCC827, 827/IcoR, PC9 and PC9/IcoR cells with or without icotinib or Stattic or siRNA treatments were lysed in lysis buffer, prepared with 1% Triton X-100,50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 2 µg/ml aprotinin. After quantification by Bradford assay, the protein samples were mixed with 3×loading buffer. Equal amounts of protein (20–40 µg/lane) were separated using 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore). The membranes were blocked using 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After exposure to appropriate secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature, the proteins were detected with chemiluminescence reagent (SuperSignal™ Western Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and analyzed using the Electrophoresis Gel Imaging Analysis system (version 6.12, DNR Bio-Imaging Systems, Ltd.).

Bioinformatics analysis and whole transcriptome resequencing

Total RNA of PC9 and PC9/IcoR cells were extracted for gene expression microarray analysis using Illumina HumanHT12 v3 BeadChip (Shanghai Oui Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.). The DEseq2 method was used to analyze the different gene expression levels between the two groups with P<0.05 and a fold-change >2.0 as the significance cut-off. Microarray data set GSE62504 were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/) (32). GSE62504 contains the expression profiling data of NSCLC sensitive EGFR-mutant cells HCC827 and EGFR-TKIs resistant HCC827-BR cells, which were established based on individual clones by maintenance of HCC827 cells in the presence of escalating concentrations of BIBW2992 of up to 2 µM. GEO2R was used to screen differentially expressed genes using a 2-fold-change cut-off. After downloading all the differentially expressed genes, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (33). The pathways of ‘focal adhesion’ and ‘extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction’ enriched from expression profiling of PC9 and PC9/IcoR, and the pathway of ‘focal adhesion’ from microarray data of HCC827 and HCC827/BR were selected to screen potential target genes.

Statistical analysis

The experimental results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments and analyzed using SPSS v16.0 software. The graphs were constructed using GraphPad v6.0 Software. Unpaired Student's t-test was used to analyze the differences between two independent groups. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the differences among multiple groups, followed by Dunnett's and Sidak's multiple comparisons tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

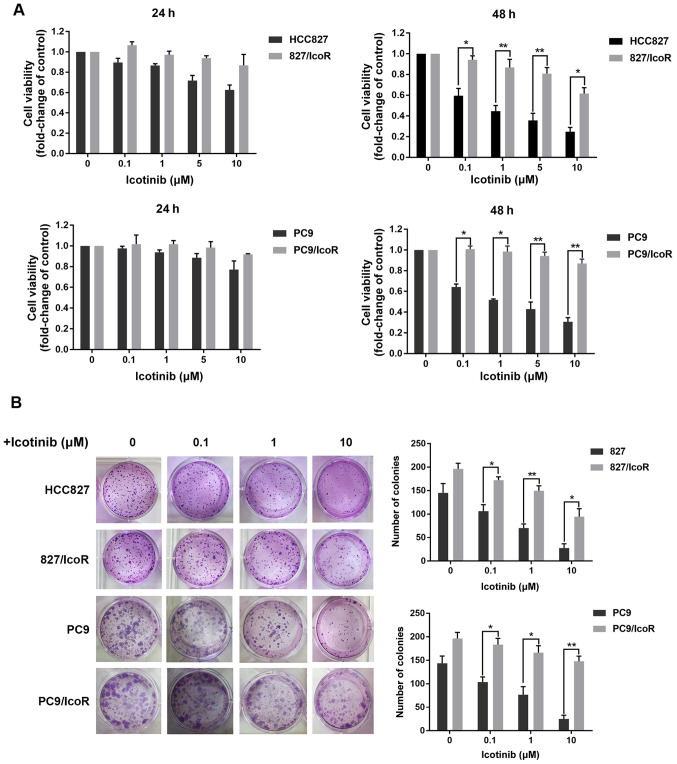

PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR cells show significant resistance to icotinib

The PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR resistant cell lines were established by gradually exposing PC9 and HCC827 parental cells to icotinib up to 10 and 5 µM, respectively. As shown in the MTT assays of 48 h, the resistant cell lines showed increased resistance to icotinib compared with parental cells, which showed dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation. Colony formation also showed that icotinib failed to inhibit the formation of colonies derived from PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR compared with parental cells (Fig. 1B). However, when treated with icotinib for 24 h, there were no remarkable differences in the inhibition of cell viability between parental and resistant cells (Fig. 1A). Similar results were also obtained when cells were exposed to gefitinib for 48 h (Fig. S1A). Together, these results confirmed that the resistant cell lines are stable in the presence of icotinib for long period (48 h), while there was no difference between sensitive and resistant cell lines on the cell viability inhibited by icotinib in a short period (24 h).

Figure 1.

827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells are resistant to icotinib. (A) Cell viabilities were measured using MTT in parent cells (HCC827 and PC9) and resistant cells (827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR) treated with icotinib for 24 and 48 h. (B) Colony formation was performed to test the effects of icotinib on parent cells (HCC827 and PC9) and resistant cells (827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. IcoR, icotinib-resistant.

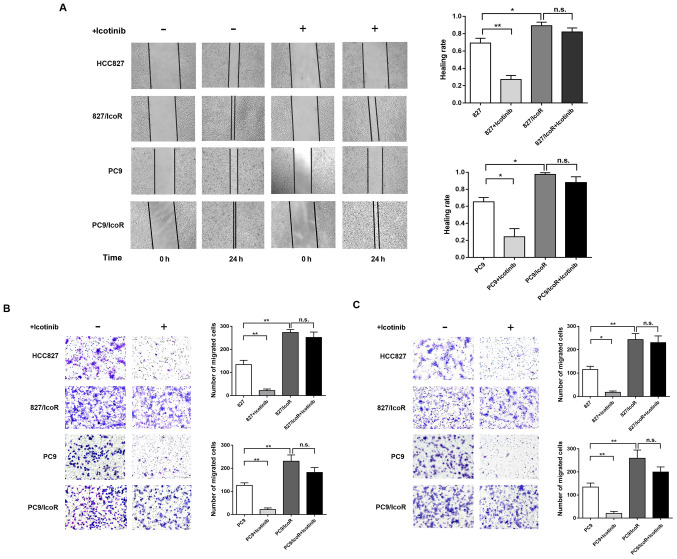

PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR cell migration and invasion ability is increased compared with parental cells

To further investigate the differences between the resistant cells and parental cells, Transwell and wound healing azssays were performed to determine the migration and invasive capability of the cell lines. As shown in Fig. 2A, the healing rate of 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells was faster compared with the parental cells, in which icotinib treatment decreased the healing rate. In addition, results from the Transwell assay showed that the number of 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells that passed through the transwell membranes and the Matrigel-coated membrane was higher compared with that of the parental cells. Similarly, icotinib treatment reduced the migration and invasion abilities of HCC827 and PC9 but had little impact on the 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells (Fig. 2B and C). Collectively, these results showed that the migration and invasion abilities of icotinib-resistant cells were significantly enhanced compared with their parental cells. Furthermore, icotinib could only inhibit the migration and invasion capacities of parental cells but showed no effect on resistant cells.

Figure 2.

Enhanced migration and invasion of 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells. (A) Wound healing assay was performed to test the migration of parent cells (HCC827 and PC9) and resistant cells (827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR) with or without icotinib treatment. (B and C) Transwell migration and invasion assays of HCC827, 827/IcoR, PC9 and PC9/IcoR with or without icotinib treatment (magnification, ×200). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. IcoR, icotinib-resistant. n.s., not significant; IcoR, icotinib-resistant.

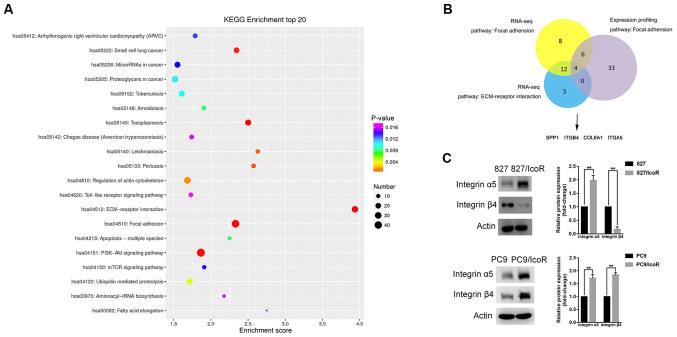

Integrin α5 is overexpressed in icotinib-resistant cells

To determine the causes of enhanced migration and invasion in icotinib-resistant cells, a gene microarray was used to identify differentially expressed genes that were upregulated in PC9/IcoR cells compared with parental cells. The top 20 pathways were identified using KEGG enrichment analysis, among which the ‘focal adhesion’ pathway and the ‘ECM-receptor interaction pathway’ had higher scores, indicating that these significantly enriched pathways were mostly associated with metastasis (Fig. 3A). The gene microarray data of HCC827 and HCC827/BR cell lines were downloaded in the GSE62504 microarray dataset and the ‘focal adhesion’ pathway was identified using GEO2R and KEGG analysis. To narrow the range and to obtain more precise results, the intersection of the three pathways was identified, as shown in Fig. 3B. Finally, four genes were identified, including integrin α5 and integrin β4, as members of the integrin family of proteins.

Figure 3.

Integrin α5 is highly expressed in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells. (A) Top 20 signaling pathways that were upregulated in PC9/IcoR compared with PC9 were screened using KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. (B) A total of four genes, including integrin α5 and integrin β4, were obtained as the intersection of the three pathways using Venn diagram. (C) Protein expression of integrin α5 and integrin β4 of HCC827, 827/IcoR, PC9 and PC9/IcoR cells by western blotting. **P<0.01. IcoR, icotinib-resistant; tRNA, transfer RNA; ECM, extracellular matrix; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; ITGB4, integrin β4; COL6A1, collagen alpha-1(VI) chain; ITGA5, integrin α5.

To verify these results, western blotting analysis was performed to identify the protein expression levels of integrin α5 and integrin β4 in the cell lines (Fig. 3C). The data showed that the protein expression levels of integrin α5 were higher in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells compared with those in parental cells. The level of integrin β4 expression was enhanced in PC9/IcoR cells but not in 827/IcoR cells compared with their respective parental cell lines. Moreover, knockdown of integrin α5 did not change the expression level of integrin β4, implying no association between them (Fig. S1C). These data suggested that it was integrin α5 instead of integrin β4 that played a key role in icotinib resistance.

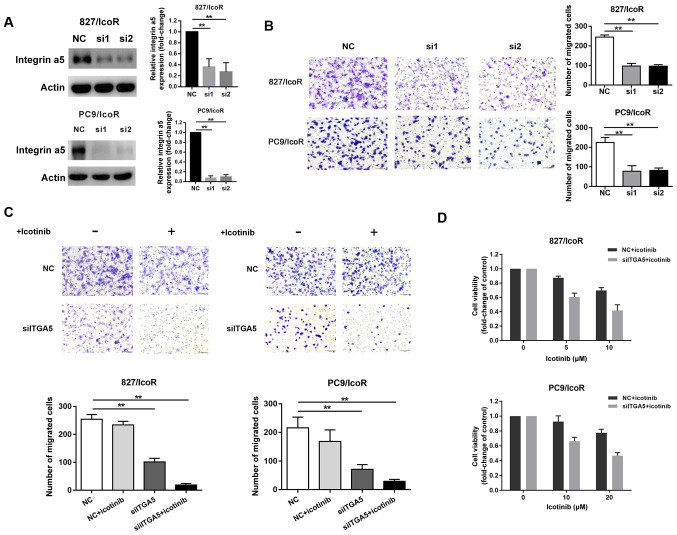

Integrin α5 promotes migration, invasion and icotinib resistance in resistant cells

Compared with treatment with NC siRNA, treatment with si-ITGA5 (si1 and si2) suppressed the expression of integrin α5 protein in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells (Fig. 4A). Transwell assays showed that the number of cells that had passed through the Transwell membranes were significantly decreased after transfection with si1 and si2 (Fig. 4B). However, the migration resistant cells decreased when treated with si-ITGA5 and icotinib together (both P<0.001; Fig. 4C). Moreover, the cell viability of 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells were partly decreased when treated with integrin α5 siRNA and icotinib together (Fig. 4D). Therefore, the sensitivity to icotinib of resistant cells was partly restored after transfected with siITGA5.

Figure 4.

Integrin α5 promotes migration, invasion and icotinib resistance in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells. (A) Western blotting was used to detect integrin α5 expression in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR transfected with the siNC or the siITGA5. (B) Transwell migration assays of 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR with transient integrin α5-knockdown. (C) Transwell migration assay of resistant cells with or without treatment of icotinib after transfection with the siNC or the siITGA5 for 24 h (magnification, ×200). (D) Effect of icotinib treatment on cell viability after transfection with the siNC or the siITGA5 for 24 h in 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR, assessed using MTT assays. **P<0.01. IcoR, icotinib-resistant; si-, small interfering; ITGA5, integrin α5; NC, negative control.

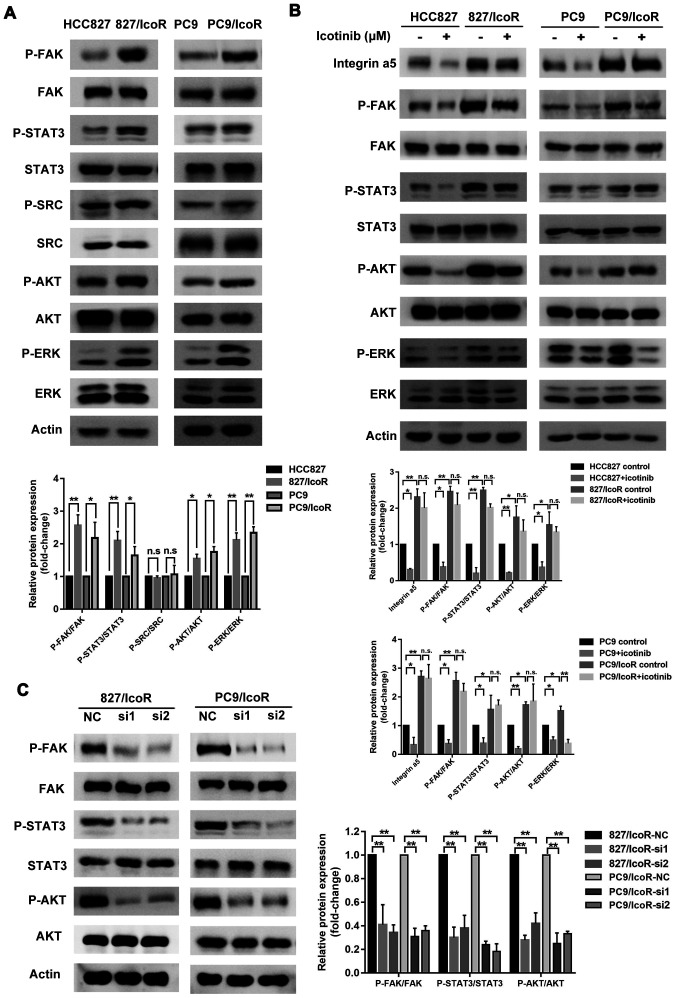

Integrin α5 increases icotinib resistance-associated malignancy through the FAK-STAT3/AKT signaling pathway

To further clarify the underlying mechanisms of integrin α5 in icotinib resistance, western blotting was performed to identify its related signaling effects. The data showed that the expression levels of integrin α5 related signaling, such as p-FAK, p-STAT3, p-AKT and p-ERK, were higher in the resistant cell lines compared with the parental cell lines except p-SRC (Fig. 5A). The expression levels of p-FAK, p-STAT3 and p-AKT were decreased in icotinib-treated sensitive cells and did not change in icotinib-treated resistant cells except p-ERK (Fig. 5B), which were consistent with the results indicating that the migration and invasion capacity of resistant cells were not affected by icotinib.

Figure 5.

Integrin α5/FAK-STAT3/AKT signaling pathway enhances icotinib resistance-associated malignancy. (A) Expression of proteins in the conventional pathway downstream of integrin in icotinib-resistant cells compared with parent cells. (B) Upregulated genes of resistant cells treated with or without icotinib in parent and resistant cells were analyzed using western blotting. (C) Western blotting of p-FAK, p-STAT3 and p-AKT in integrin α5-knockdown 827/IcoR and PC9/IcoR cells. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. FAK, focal adhesion kinase; p-, phosphorylated; IcoR; icotinib-resistant; n.s., not significant.

The persistent activation of p-EGFR in PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR may explain the resistance to gefitinib in icotinib-resistant cells (Fig. S1A and B). Furthermore, after knocking down integrin α5 using siRNAs in the resistant cells, the protein expression levels of p-FAK, p-STAT3 and p-AKT were notably decreased (Fig. 5C). When treated with STAT3 inhibitor, Stattic, the phosphorylation level of AKT was significantly decreased, whereas no change of FAK phosphorylation was observed (Fig. S1D). These results suggested that the integrin α5/FAK-STAT3/AKT signaling pathway played a notable role in icotinib-resistant cells.

Discussion

The present study found that the malignant properties of icotinib-resistant NSCLC cells were enhanced compared with non-resistant cells. Further investigations showed that the upregulation of integrin α5 significantly contributed to increased invasion and migration ability and slightly increased icotinib resistance through the FAK/STAT3/AKT signaling pathway.

To the best of our knowledge, the majority of current research relating to the mechanism of resistance to EGFR-TKIs has focused on increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis with few studies considering impacts on metastasis (34–36). However, clinical criteria for acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs are not limited to recurrence of the primary tumor and metastasis into sites nearby, but also include systemic multisite infiltration and distant metastasis (37,38).

Few studies have focused on specific changes in the malignant capacity of TKI-resistant cells and how changes in TKI resistance-related genes affect malignancy. In order to find out the mechanism for the change in malignancy, resistant cell lines were established by gradually exposing PC9 and HCC827 parental cells to icotinib, an effective TKI developed in China (31), and the resistant cell lines PC9/IcoR and 827/IcoR were also found to be resistant to gefitinib. These results were also similar to those presented in Chen et al (39). Furthermore, the present study found that capacity of migration and invasion was significantly increased in icotinib-resistant cells, which provided evidence to explain the frequently observed metastatic phenomenon in patients diagnosed with EGFR-TKI-resistance. Furthermore, the expression profiles of parental and drug-resistant cells were screened using a combination of online analyses to demonstrate that integrin α5 played a notable role in this process. These results suggested that strategies targeting integrin may be effective in the treatment of patients with TKI-resistant tumors.

Integrin family members are cell-surface transmembrane protein receptors that consist of 18 different α subunits and eight β subunits. Amongst these proteins, β1, β3, αv and α5 are the main factors that affect metastasis and survival in tumors (40). The integrin family can provide a bridge for the mechanical adhesion of cells to the ECM and increase the ability of tumor cells to metastasize and invade (41,42). In addition, integrins transmit signals to metastatic tumor cells in order to facilitate the migration of these cells, which indicates that integrins are involved in the signaling pathways that induce tumor metastasis (43).

Previous studies have shown that integrin can promote malignant behavior in multiple tumor types including metastatic melanoma and breast, prostate, pancreatic and lung cancer (44–47). In lung cancer, targeting TGF-β1 and integrin β3 can significantly reduce lymph node metastasis (48). The deletion of integrin β3 can also increase the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to traditional chemotherapy drugs (49). Several reports have shown that high expression levels of integrin β1 and β3 can increase the resistance of lung cancer cells to EGFR-TKIs (50–52). However, these studies only found that integrins are highly expressed in TKIs-resistant NSCLC cells. After knockdown of specific integrins such as integrin β1 and β3, cell proliferation and apoptosis are impacted but the changes are not correlated with alterations in metastatic capacity. Thus, the effect of integrin on the migration and invasion of TKI-resistant cells remains unclear.

Integrin α5 was selected as a key molecule that could potentially affect the malignancy of drug-resistant cells in the present study. The entire transcriptome of the drug-resistant cell lines was sequenced and the data were compared with public databases. Further investigation showed that knocking down integrin α5 significantly reduced the migration capacity of TKI-resistant cells, but the effect on proliferation ability was not obvious. These results indicated that integrin α5 can promote cell migration and also provided a basic mechanism for this in TKI-resistant tumor cells. In addition, tumors with high expression levels of different integrin subunits were characterized by different organ-specific metastases in which integrin α5 targets the lung (41). Hoshino et al (41) showed that tumor cells releasing integrin α5 exosomes are more prone to lung metastasis, whilst cells producing β1 or β3 exosomes can metastasize to various organs including bone, lung, liver and brain. Based on these characteristics of integrin α5, the proportion of patients with EGFR-TKI resistance alongside integrin α5-overexpression and the metastatic burden of these patients merits further research.

In metastatic tumor cells, the regulation of cellular activities is important after stable and firm adhesion to the ECM (40). Ligand binding to integrins induces survival signals to tumor cells to enhance cell viability (42). However, tumor cells that unstably adhere to the ECM undergo withdrawal of survival signals and initiate apoptosis (43,53). Thus, specific types of integrins are needed to help cells avoid apoptosis, which is a key mechanism for successful metastasis. A previous study reported that integrin signaling is associated with several receptor tyrosine kinases that can enhance cancer cell survival and proliferation, principally EGFR (54). Common integrin downstream signals are also associated with cell survival, including the PI3K/AKT pathway, which also leads to EGFR-TKI resistance. Integrins are non-receptor kinase receptors, so the aforementioned signal transduction pathways require kinase partners, such as FAK (55,56). Integrin β1 has been shown to promote erlotinib resistance in lung cancer by activating the SRC/AKT pathway (50). In the present study, although the common integrin downstream signals FAK, SRC, AKT and ERK were continuously activated in drug-resistant cells, there was no difference in the activation of SRC between sensitive and drug-resistant cells. Moreover, icotinib treatment significantly decreased phosphorylation level of ERK in PC9/IcoR, suggesting that the ERK pathway was not involved in integrin α5-mediated malignancy and resistance. After knockdown of integrin α5, the FAK and AKT signaling pathways in drug-resistant cells were inhibited. In addition, our previous research found that TKIs induce the activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway and reduce the sensitivity of tumor cells to icotinib (57). The results of the present study showed that knockdown of integrin α5 inhibited the activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway. Therefore, we hypothesized that integrin α5 affects the migration and invasion of TKIs-resistant cells through the FAK-STAT3/AKT signaling pathway.

EMT is also regarded as one of the mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs with low E-cadherin (a cell-adhesion protein) and high vimentin/fibronectin expression levels. This is also upregulated by integrins in various tumors including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast tumors and thyroid carcinoma (58–60). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence indicating the effect of integrins on the metastatic capacity of TKIs-resistance by regulating the EMT phenotype.

Evidence suggests that integrin αvβ5 may be a potential therapeutic target in patients with lung adenocarcinoma with brain metastases (61). Integrin α5β1 can also be used as a biomarker to predict the prognosis of early-stage NSCLC (62). As the integrins play notable roles in tumor metastasis, integrin inhibitors may have potential value as therapeutics. Currently, integrin inhibitors are divided into three categories: Monoclonal antibodies, small molecule inhibitors and small peptides. However, to the best of our knowledge, the majority are in early-phase clinical trials (63). For example, Cilengitide is an arginine-glycine-aspartate pentapeptide used as an αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin inhibitor that has achieved good therapeutic effects in phase II and III clinical trials of recurrent glioblastoma (64). Volociximab, an integrin α5β1 inhibitor, is a chimeric human IgG4 antibody inhibitor that has already been used in several phase II clinical trials including metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and NSCLC (65). The present study identified integrin α5 as a key molecule in mediating the malignant properties of EGFR-TKIs resistant cells. Therefore, in future clinical applications, the combination of EGFR-TKIs and integrin α5 inhibitors may help reduce drug resistance and the risk of metastasis in patients with EGFR-TKI-resistant NSCLC. However, there are limitations to the study, since no animal model or human samples were included in the investigation of relationship between integrin α5 and metastasis in vivo. These could be considered in future study, but this approach still could provide a basis for clinical applications and may help to improve prognosis and quality of life for patients with lung cancer.

The present study demonstrated a promising therapeutic approach using the interruption of the integrin α5-FAK/STAT3/AKT signaling pathway as a synergistic combination therapy with EGFR-TKI to overcome malignancy of cells after development of EGFR-TKI resistance. Upregulated genes in drug-resistant cells have a notable in promoting migration and may have significant effects on proliferation or apoptosis. A combination therapy to prevent metastasis in patients with TKI resistance may be an effective treatment strategy, and may also provide evidence to explore the underlying mechanisms of TKI-resistance in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YF1309403), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81972197 and 81472193), The Key Research and Development Program of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2018225060), The Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2019-ZD-777), The Technological Special Project of Liaoning Province of China (grant no. 2019020176-JH1/103), The Science and Technology Plan Project of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2013225585) and Science and Technology Plan Project of Shenyang City (grant no. 19-112-4-099).

Funding

The study was funded by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YF1309403), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81972197 and 81472193), The Key Research and Development Program of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2018225060), The Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2019-ZD-777), The Technological Special Project of Liaoning Province of China (grant no. 2019020176-JH1/103), The Science and Technology Plan Project of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2013225585) and Science and Technology Plan Project of Shenyang City (grant no. 19-112-4-099).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). The accession number is PRJNA690636.

Authors' contributions

YY, CZ, KH performed the experiments. YY, JW, XH and YW drafted the manuscript. YW, YC and XC performed the online data analysis. XC, CZ and KH revised the manuscript. XH, JZ and YL conceptualized and designed the study. JW, YL, XH and YC established the icotinib-resistant cell lines. YY and JZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Current cancer epidemiology. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;9:217–222. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191008.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung cancer 2020: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2020;41:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbst RS, Heymach JV, Lippman SM. Lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1367–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire S. World Cancer Report 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:418–419. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keedy VL, Temin S, Somerfield MR, Beasley MB, Johnson DH, McShane LM, Milton DT, Strawn JR, Wakelee HA, Giaccone G. American society of clinical oncology provisional clinical opinion: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) Mutation testing for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer considering first-line EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2121–2127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han SW, Kim TY, Hwang PG, Jeong S, Kim J, Choi IS, Oh DY, Kim JH, Kim DW, Chung DH, et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2493–2501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somaiah N, Fidler MJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Wahlquist A, Shirai K, Buckingham L, Hensing T, Bonomi P, Simon GR. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are exceptionally rare in thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1)-negative adenocarcinomas of the lung. Oncoscience. 2014;1:522–528. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch FR, Suda K, Wiens J, Bunn PA., Jr New and emerging targeted treatments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohashi K, Maruvka YE, Michor F, Pao W. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant disease. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1070–1080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwano M, Sonoda K, Murakami Y, Watari K, Ono M. Overcoming drug resistance to receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Learning from lung cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;161:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelman JA, Janne PA. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2895–2899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Song Y, Liu D. EAI045: The fourth-generation EGFR inhibitor overcoming T790M and C797S resistance. Cancer Lett. 2017;385:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgillo F, Della Corte CM, Fasano M, Ciardiello F. Mechanisms of resistance to EGFR-targeted drugs: Lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000060. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan CS, Cho BC, Soo RA. Next-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2016;93:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, Miller VA, Pan Q, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF, Heelan RT, Kris MG, Varmus HE. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto K, Okamoto I, Hatashita E, Kuwata K, Yamaguchi H, Kita A, Yamanaka K, Ono M, Nakagawa K. Overcoming erlotinib resistance in EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer cells by targeting survivin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204–213. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krawczyk P, Mlak R, Powrozek T, Nicos M, Kowalski DM, Wojas-Krawczyk K, Milanowski J. Mechanisms of resistance to reversible inhibitors of EGFR tyrosine kinase in non-small cell lung cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2012;16:401–406. doi: 10.5114/wo.2012.31768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo CD, Park KH, Park CK, Lee SH, Kim SJ, Yoon HK, Lee YS, Lee EJ, Lee KY, Kim TJ. Expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) predicts poor responses to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer patients harboring activating EGFR mutations. Lung Cancer. 2015;87:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang Y, McDonnell S, Clynes M. Examining the relationship between cancer invasion/metastasis and drug resistance. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2002;2:257–277. doi: 10.2174/1568009023333872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brozovic A. The relationship between platinum drug resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:605–619. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niwa N, Tanaka N, Hongo H, Miyazaki Y, Takamatsu K, Mizuno R, Kikuchi E, Mikami S, Kosaka T, Oya M. TNFAIP2 expression induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and confers platinum resistance in urothelial cancer cells. Lab Invest. 2019;99:1702–1713. doi: 10.1038/s41374-019-0285-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Chen Y, Li F, Bao L, Liu W. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab attenuate cisplatin resistant ovarian cancer cells progression synergistically via suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Front Immunol. 2019;10:867. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Jiang J, Ying G, Xie XQ, Zhang X, Xu W, Zhang X, Song E, Bu H, Ping YF, et al. Tamoxifen enhances stemness and promotes metastasis of ERalpha36(+) breast cancer by upregulating ALDH1A1 in cancer cells. Cell Res. 2018;28:336–358. doi: 10.1038/cr.2018.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng LL, Gao G, Deng HB, Wang F, Wang ZH, Yang Y. Co-occurring genetic alterations predict distant metastasis and poor efficacy of first-line EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2019;145:2613–2624. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim SM, Syn NL, Cho BC, Soo RA. Acquired resistance to EGFR targeted therapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;65:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yufen X, Binbin S, Wenyu C, Jialiang L, Xinmei Y. The role of EGFR-TKI for leptomeningeal metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Springerplus. 2016;5:1244. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2873-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JJ, Chen HJ, Yan HH, Zhang XC, Zhou Q, Su J, Wang Z, Xu CR, Huang YS, Wang BC, et al. Clinical modes of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure and subsequent management in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu X, Chen L, Liu L, Niu X. EMT-Mediated acquired EGFR-TKI resistance in NSCLC: Mechanisms and strategies. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1044. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi YK, Wang L, Han BH, Li W, Yu P, Liu YP, Ding CM, Song X, Ma ZY, Ren XL, et al. First-line icotinib versus cisplatin/pemetrexed plus pemetrexed maintenance therapy for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (CONVINCE): A phase 3, open-label, randomized study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2443–2450. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH, Sherman PM, Holko M, et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets-update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurppa KJ, Liu Y, To C, Zhang T, Fan M, Vajdi A, Knelson EH, Xie Y, Lim K, Cejas P, et al. Treatment-induced tumor dormancy through YAP-Mediated transcriptional reprogramming of the apoptotic pathway. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:104–122.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong X, Tanino R, Sun R, Tsubata Y, Okimoto T, Takechi M, Isobe T. Protein tyrosine kinase 2: A novel therapeutic target to overcome acquired EGFR-TKI resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Respir Res. 2019;20:270. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu YN, Tsai MF, Wu SG, Chang TH, Tsai TH, Gow CH, Chang YL, Shih JY. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors is mediated by the reactivation of STC2/JUN/AXL signaling in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:1609–1624. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe H, Okada M, Kaji Y, Satouchi M, Sato Y, Yamabe Y, Onaya H, Endo M, Sone M, Arai Y. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours-revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2009;36:2495–2501. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ, Engelman JA, Kris MG, Janne PA, Lynch T, Johnson BE, Miller VA. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:357–360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Wu J, Yan HF, Cheng Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, Deng M, Che X, Hou K, Qu X, et al. Lymecycline reverses acquired EGFR-TKI resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer by targeting GRB2. Pharmacol Res. 2020;159:105007. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamidi H, Ivaska J. Every step of the way: Integrins in cancer progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:533–548. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0038-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kechagia JZ, Ivaska J, Roca-Cusachs P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:457–473. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YN, Koo KH, Sung JY, Yun UJ, Kim H. Anoikis resistance: An essential prerequisite for tumor metastasis. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:306879. doi: 10.1155/2012/306879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemlich Y, Baruch EN, Besser MJ, Shoshan E, Bar-Eli M, Anafi L, Barshack I, Schachter J, Ortenberg R, Markel G. ADAR1-mediated regulation of melanoma invasion. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2154. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04600-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, Yoshioka T, Muller WJ, Inghirami G, Giancotti FG. Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fromont G, Cussenot O. The integrin signalling adaptor p130CAS is also a key player in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:227. doi: 10.1038/nrc2967-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu M, Zhang Y, Yang J, Cui X, Zhou Z, Zhan H, Ding K, Tian X, Yang Z, Fung KA, et al. ZIP4 increases expression of transcription factor ZEB1 to promote integrin α3β1 signaling and inhibit expression of the gemcitabine transporter ENT1 in pancreatic cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:679–692.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salvo E, Garasa S, Dotor J, Morales X, Pelaez R, Altevogt P, Rouzaut A. Combined targeting of TGF-β1 and integrin β3 impairs lymph node metastasis in a mouse model of non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:112. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong SK, Lee H, Kwon OS, Song NY, Lee HJ, Kang S, Kim JH, Kim M, Kim W, Cha HJ. Large-scale pharmacogenomics based drug discovery for ITGB3 dependent chemoresistance in mesenchymal lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:175. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0924-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanda R, Kawahara A, Watari K, Murakami Y, Sonoda K, Maeda M, Fujita H, Kage M, Uramoto H, Costa C, et al. Erlotinib resistance in lung cancer cells mediated by integrin β1/Src/Akt-driven bypass signaling. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6243–6253. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seguin L, Kato S, Franovic A, Camargo MF, Lesperance J, Elliott KC, Yebra M, Mielgo A, Lowy AM, Husain H, et al. An integrin β3-KRAS-RalB complex drives tumour stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:457–468. doi: 10.1038/ncb2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ju L, Zhou C, Li W, Yan L. Integrin beta1 over-expression associates with resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1565–1574. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vachon PH. Integrin signaling, cell survival, and anoikis: Distinctions, differences, and differentiation. J Signal Transduct. 2011;2011:738137. doi: 10.1155/2011/738137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Somanath PR, Malinin NL, Byzova TV. Cooperation between integrin alphavbeta3 and VEGFR2 in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo DY, Wazir R, Tian Y, Yue X, Wei TQ, Wang KJ. Integrin αv mediates contractility whereas integrin α4 regulates proliferation of human bladder smooth muscle cells via FAK pathway under physiological stretch. J Urol. 2013;190:1421–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: In command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J, Wang Y, Zheng L, Hou K, Zhang T, Qu X, Liu Y, Kang J, Hu X, Che X. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced IL-6/STAT3 activation decreases sensitivity of EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer to icotinib. Cell Biol Int. 2018;42:1292–1299. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang PF, Li KS, Shen YH, Gao PT, Dong ZR, Cai JB, Zhang C, Huang XY, Tian MX, Hu ZQ, et al. Galectin-1 induces hepatocellular carcinoma EMT and sorafenib resistance by activating FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2201. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akrida I, Nikou S, Gyftopoulos K, Argentou M, Kounelis S, Zolota V, Bravou V, Papadaki H. Expression of EMT inducers integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and ZEB1 in phyllodes breast tumors is associated with aggressive phenotype. Histol Histopathol. 2018;33:937–949. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan Y, Bhandari A, Xia E, Kong L, Zhang X, Wang O. Downregulating integrin subunit alpha 7 (ITGA7) promotes proliferation, invasion, and migration of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells through regulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2020;52:116–124. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmz144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schittenhelm J, Klein A, Tatagiba MS, Meyermann R, Fend F, Goodman SL, Sipos B. Comparing the expression of integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, fibronectin and fibrinogen in human brain metastases and their corresponding primary tumors. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:2719–2732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dingemans AM, van den Boogaart V, Vosse BA, van Suylen RJ, Griffioen AW, Thijssen VL. Integrin expression profiling identifies integrin alpha5 and beta1 as prognostic factors in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:152. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Neyns B, Goldbrunner R, Schlegel U, Clement PM, Grabenbauer GG, Ochsenbein AF, Simon M, Dietrich PY, et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2712–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mas-Moruno C, Rechenmacher F, Kessler H. Cilengitide: The first anti-angiogenic small molecule drug candidate design, synthesis and clinical evaluation. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:753–768. doi: 10.2174/187152010794728639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuwada SK. Drug evaluation: Volociximab, an angiogenesis-inhibiting chimeric monoclonal antibody. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/). The accession number is PRJNA690636.