Abstract

The reprogramming of somatic cells with defined factors, which converts cells from one lineage into cells of another, has greatly reshaped our traditional views on cell identity and cell fate determination. Direct reprogramming (also known as transdifferentiation) refers to cell fate conversion without transitioning through an intermediary pluripotent state. Given that the number of cell types that can be generated by direct reprogramming is rapidly increasing, it has become a promising strategy to produce functional cells for therapeutic purposes. This Review discusses the evolution of direct reprogramming from a transcription factor-based method to a small-molecule-driven approach, the recent progress in enhancing reprogrammed cell maturation, and the challenges associated with in vivo direct reprogramming for translational applications. It also describes our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying direct reprogramming, including the role of transcription factors, epigenetic modifications, non-coding RNAs, and the function of metabolic reprogramming, and highlights novel insights gained from single-cell omics studies.

In 1957, Conrad Hal Waddington presented his view of development using the metaphor of a ball rolling down from the top of a slope through a one-way path towards the bottom of the hill, illustrating how, as a cell differentiates, its fate is tightly controlled and becomes progressively restricted1. However, in 1987, the finding that the overexpression of MYOD — a transcription factor normally expressed in skeletal muscle cells — converts mouse embryonic fibroblasts to myoblasts2 revealed that cell identity can be modified and thus prompted the reassessment of the concept of cell differentiation. In the past three decades a large body of work has shown that it is possible to manipulate cell fate by the forced expression of transcription factors and non-coding RNAs or through the delivery of small molecules. The process of inducing a desired cell fate, by converting somatic cells from one lineage to another without transitioning through an intermediate pluripotent or multipotent state3, has been described as ‘direct reprogramming’, also known as ‘transdifferentiation’.

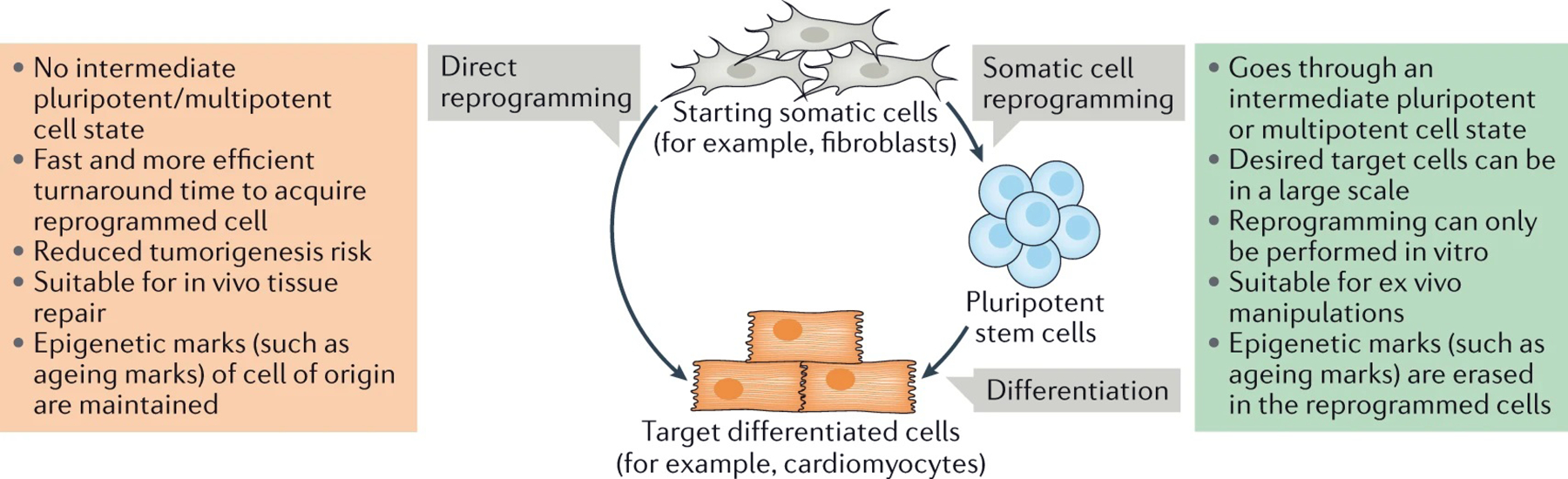

In addition to increasing our understanding of cell fate specification and plasticity, direct reprogramming holds promises for regenerative medicine. Compared to induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming (not the focus of this review, reviewed in REFs4–7), direct reprogramming is a faster and more efficient process and has unique advantages for tissue repair (FIG. 1). Whereas the use of iPSCs6 requires the isolation of somatic cells and their reprogramming to a pluripotent state followed by their differentiation into a different lineage, in principle, direct reprogramming enables the conversion of cells in situ (in the desired tissue) without transitioning through an intermediate pluripotent state and without the need for ex vivo cell expansion and transplantation8. Although direct reprogramming has been achieved for several cell types in vitro and in vivo9–11, a number of challenges remain to be overcome before the approach can be used in the clinic: the efficiency of conversion remains low, in vitro reprogrammed cells are immature12,13, there are no safe delivery methods, there is a potential for the starting cell population to become depleted and it is not yet possible to precisely direct differentiation towards a desired cell subtype. Despite these many challenges, there has been substantial progress in advancing this technology towards applications in regenerative medicine. Importantly, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying direct reprogramming has substantially increased — a knowledge that is essential to better manipulate cell identity.

Fig. 1 |. Principles of indirect and direct reprogramming.

Direct reprogramming (also known as transdifferentiation) refers to a change in cell fate that, unlike in indirect reprogramming, does not involve a pluripotent intermediate state (usually the production of induced pluripotent stem cells). Due to the self-renewal capacity of the intermediate pluripotent stem cells, indirect reprogramming can produce target cells in a large scale and is suitable for ex vivo cell production. On the other hand, by not requiring this intermediate step, direct reprogramming is a faster and more efficient process and, in principle, as it can occur both ex vivo and in situ (in the target tissue), it is more suitable for in vivo tissue repair. Moreover, direct reprogramming could retain epigenetic hallmarks of the cell of origin, for example, ageing hallmarks, in the reprogrammed cell compared with indirect reprogramming177, making the cells obtained through direct reprogramming more suitable for modelling ageing-related disease.

In this Review, we first describe the discovery of direct reprogramming, how the technology has evolved over the years, and its potential and challenges in regenerative medicine. We then discuss the molecular mechanisms of direct reprogramming, with particular emphasis on the role of epigenetic modifiers, non-coding RNAs and metabolic repatterning due to the recent substantial progress in these fields. We devote the last section of the Review to the discussion of what can be learnt from the development and application of single-cell omics technologies. As direct reprogramming is a heterogeneous and asynchronous process, these technologies provide important mechanistic insights into how cells change fates.

The advent of direct reprogramming

Following the discovery of iPSCs, it soon became possible, exploiting knowledge from developmental biology, to generate multiple somatic cell types in vitro and in vivo, including neurons, pancreatic β-cells, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes and others. However, there were many technical difficulties and conceptual concerns in the early days, largely due to the lack of knowledge on the mechanisms underlying direct reprogramming. Numerous studies have focused on elucidating the molecular mechanisms of direct reprogramming and refining the reprogramming ‘cocktails of factors’, which have led to significant improvement in reprogramming efficiency, target cell maturation and the development of methods for reprogramming factor delivery.

The discovery of cell plasticity.

After the first report of the conversion of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) into myoblasts by forced expression of MyoD2, other transcription factors or combinations of them were found to be capable of converting one cell type to another. In 1995, the forced expression of Gata1 was shown to convert avian myeloblasts into either eosinophils or thromboblast-like cells as well as macrophages into myeloblasts, eosinophils or erythroblast-like cells14. Later, in 2004 and 2006, forced expression of C/EBP with or without PU.1 could convert fully committed mouse pre-T cells or B cells to macrophages15,16. By screening more than 1,000 transcription factors, it was found that the combination of Neurog3, Pdx1 and Mafa was sufficient to reprogramme adult pancreatic exocrine cells to functional insulin-secreting cells in mouse17. However, these cell fate conversions all occur between cells derived from the same embryonic germ layer.

The landmark discovery of iPSCs in 2006 (REF.3) and the possibility of reverting somatic cells to a pluripotent state inspired many works that converted somatic cells into another cell type from the same or a different germ layer. In 2010, after testing a pool of 14 transcription factors that are crucial for heart development, cardiomyocyte-like cells (or induced cardiomyocytes; iCMs) were successfully induced in vitro from mouse cardiac fibroblasts via the overexpression of Gata4, Mef2c and Tbx5 (a transcription factor combination referred to as GMT), and these iCMs were transplanted in vivo in a live heart18. Subsequently, in 2012, the in situ conversion of endogenous cardiac fibroblasts into iCMs using GMT or GHMT (GMT with added Hand2) led to an improvement in heart function in a murine model of myocardial infarction11,19. Around the same time, the transcription factor combinations to convert mouse fibroblasts into induced neurons (iNs)20 and into induced hepatocytes21,22 were reported.

microRNAs have also been used for direct reprogramming. For example, the forced expression of miR-9/9* and miR-124 converted human fibroblast into neurons23, and the combined overexpression of miR-1, miR-133, miR-208 and miR-499 has been used to reprogramme cardiac non-myocytes into functional iCMs in vitro24 and in vivo25.

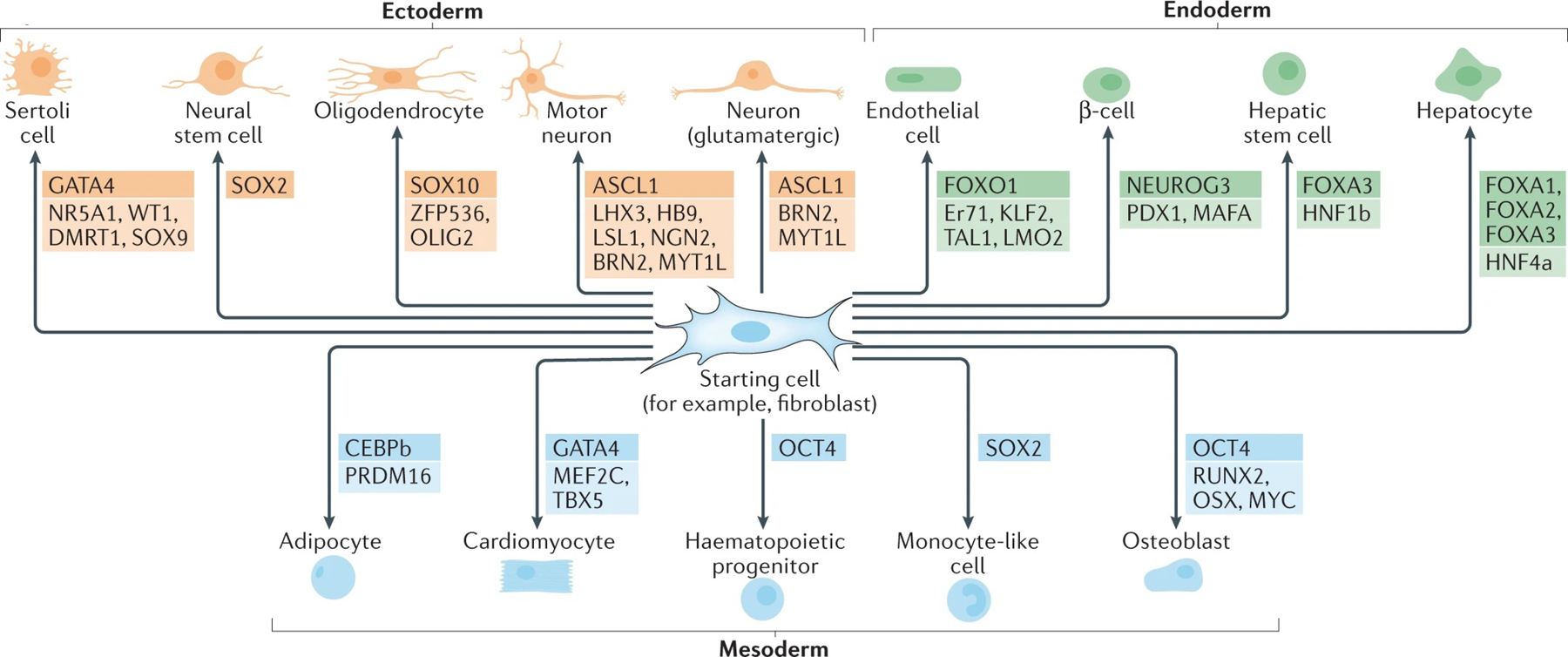

There are now multiple examples of the direct conversion of cells derived from one germ layer (ectoderm, mesoderm or endoderm) into a cell type of a different germ layer26 (FIG. 2; Supplementary Table 1). With the development of new strategies to identify novel reprogramming factors (BOX 1), it is conceivable that it will be possible to generate more cell types.

Fig. 2 |. Direct reprogramming across germ layers.

Direct reprogramming can induce cell fate conversions between cell lineages that are derived from the same embryonic germ layer but can also cross the germ layer barrier. That is, cells derived from one germ layer can be converted to cell types originating from another germ layer. Fibroblasts originating from the mesoderm have been used as starting cells in most direct reprogramming experiments owing to their availability and high plasticity. Other cell types, such as macroglial cells from the ectoderm and α-cells from the endoderm, have also been used for successful direct reprogramming. The combinations of reprogramming factors used for each cell type conversion are shown; pioneer factors that are crucial for successful direct reprogramming are highlighted. Small molecules and microRNAs are also used for direct reprogramming (not shown).

Box 1 |. Identification of reprogramming factors.

As the mammalian genome encodes nearly 2,000 transcription factors (TFs)178, the traditional exhaustive screening of pooled TFs to identify candidate reprogramming factors is a tedious and slow process17. Researchers have relied on knowledge from developmental biology to reduce the size of the screening pool3,18,20–22. To further expedite the discovery process, two new strategies have been recently adopted: algorithm-based prediction of TFs and exhaustive genome-wide CRISPR activation screening of TFs and other DNA-binding regulators64.

Mogrify is a computational framework designed to predict sets of TFs capable of converting a starting cell type into another cell type of interest12,179,180. Based on the transcriptomic information of roughly 300 different cell and tissue types deposited in the FANTOM5 database181 and in the known interactome database STRING182, Mogrify is able to assess the ability of each TF to determine the fates of the starting and target cell type, thereby allowing the identification of TFs situated at the top of the gene regulatory networks orchestrating the identities of the two cell types. By using Mogrify, researchers successfully identified the reprogramming factors to convert human fibroblasts to keratinocytes or to convert keratinocytes to microvascular endothelial cells179. It is worth noting that TFs required for cell fate conversion are not necessarily those encoded by the most differentially expressed genes. In fact, among the 74 genes that promoted neuronal differentiation, 41 exhibited no differential expression between neurons and embryonic stem cells, underscoring the potential pitfalls of reprogramming factor prediction methods based on expression profile analyses64.

Another strategy known as CRISPR-activation183 — whereby gene expression is activated by fusing a catalytically dead Cas9 endonuclease to a transcription activator — enables the performance of high-throughput gain-of-function screens of a large number of TFs in an unbiased manner. With this strategy, it was shown that the activation of endogenous Brn2 and Ngn1 led to the direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into neurons, with a reprogramming efficiency of 83% compared with the 20% efficiency achieved by forced expression of Brn2, Myt1l and Ascl1 (REFs20,64). Although the pooling strategy of a CRISPR-activation screen could lead to potential false-positive and false-negative hits due to the combinatorial effect of multiple single guide RNAs within the same cell, it has the potential to become a platform for unbiased systematic identification of new factors for direct reprogramming.

Progress towards regenerative medicine.

The goal of regenerative medicine is to restore the structure and functionality of damaged organs or tissues. There are ongoing clinical trials for cell therapies to replenish major functional cell types that are lost in human disease, for example, neurons in Parkinson disease and retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration27–29. Autologous cell therapies using iPSC-derived cells have yielded promising results (reviewed in REF.30). Given that direct reprogramming can generate reprogrammed cells in situ in diseased organs in animal models8,31, its use could potentially overcome the technical difficulties associated with iPSC technology such as ex vivo reprogramming and large scale expansion. In vivo direct reprogramming was first attempted by delivering Ngn3, Pdx1 and Mafa into mouse pancreatic exocrine cells to generate pancreatic β-cells17. The induced β-cells were functional and increased insulin levels and glucose tolerance in a mouse model of diabetes17. Later, scar-forming cardiac fibroblasts were successfully converted to iCMs in a mouse model of myocardial infarction, resulting in scar size reduction and improvement of heart function post heart injury11,19,24,32. Similarly, endogenous glial cells were converted into functional neurons with various combinations of reprogramming factors33–38, hepatocytes were obtained from hepatic myofibroblasts attenuating liver fibrosis39 and rod photoreceptors were generated in retinas, improving vision40. Thus, several cell types have been obtained by in vivo direct reprogramming, and there has been substantial progress in promoting the maturation of reprogrammed cells into the desired cell types and in identifying optimal starting and target cell types.

In vivo reprogramming occurs within a unique cellular and extracellular environment that provides tissue-specific biochemical and mechanical signals, and these conditions have led to the production of cells that are more mature, as assessed by function and transcriptome, than those obtained in vitro41,42. For example, iCMs generated from mouse cardiac fibroblasts in vitro closely resemble neonatal cardiomyocytes, whereas iCMs obtained in vivo had a transcription profile and structural and physiological features similar to those of adult cardiomyocytes and became electrically coupled with endogenous cardiomyocytes11,41. The functionality of β-cells obtained from acinar cells in mice was comparable to that of endogenous β-cells as they aggregated to form islet-like structures that secreted insulin after glucose stimulation43. Moreover, in a mouse model of extreme β-cell ablation, endogenous α-cells spontaneously converted to β-cells, suggesting that exposure of α-cells to a β-cell-depleted pancreatic environment induces fate conversion44. The native microenvironment of live organs is believed to be a major contributing factor to the observed enhancement in cell fate conversion and maturation. For example, chemokine signals, such as growth factors found in the microenvironment, could enhance direct reprogramming. Indeed, the addition of FGF2 (a growth factor whose level increases at the injured sites in response to inflammation upon brain damage45) to a virus solution promoted the conversion of non-neuronal cells to Dcx+ neurons in the adult mouse neocortex34. The biophysical properties of the extracellular matrix and the mechanical force sensed by the cells also play an important part in cell-fate conversion and maturation. For example, the generation of functional neurons was more efficient when using a 3D brain-like scaffold composed of decellularized brain extracellular matrix than using 2D methods46. Similarly, during miRNA-induced cardiac reprogramming, tissue-engineered 3D scaffolds enhanced the expression of cardiac proteins in iCMs obtained from neonatal cardiac and tail-tip fibroblasts when compared to 2D culture systems47.

To achieve in vivo reprogramming, it is important to identify suitable cell sources. Ideally, starting cells should be present in sufficient numbers and amenable to reprogramming. Two types of macroglial cells, astrocytes and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (also known as NG2 glia), have been intensively explored as cells to be converted to iNs. Astrocytes are widely distributed in the central nervous system and harbour neurogenic potential after stroke that can be promoted for neuronal replacement therapies48. The reprogramming of astrocytes into diverse types of neuronal cells has been achieved in multiple tissues of the central nervous system. Notably, astrocytes derived from different regions of the brain showed heterogeneity in gene expression and proliferation and therefore distinct susceptibility to reprogramming even when using the same reprogramming factors, highlighting that the native cellular context should be considered when identifying starting cells49. NG2 glia have self-renewal capacity and are highly proliferative50,51, which could reduce the risk of depleting the endogenous population that is important for the maintenance of tissue haemostasis. In addition to these two macroglial cell types, neurons themselves were reprogrammed into other types of neurons through direct reprogramming52,53. Cardiac fibroblasts have been the major source for in vivo iCM conversion as they are activated and have been shown to contribute to fibrosis and scar formation following heart injury11,19,25,45. The in vivo reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts led to the replenishment of cardiomyocyte pools and reduced scar formation11. In the pancreas, exocrine acinar cells and endocrine α-cells are considered ideal cell sources for in vivo reprogramming. Because acinar cells are the most abundant cell type in the pancreas, targeting these cells could minimize the risk of depleting the starting cell population17,43. However, pancreatic α-cells are located adjacent to β-cells and their transcriptome is more similar to that of β-cells54–56, making α-cells more amenable to being converted to β-cells in vivo.

A crucial aspect for reprogramming to be successful and achieve the functional repair of tissues or organs is obtaining the desired functional cell types. The overexpression of Ascl1 alone in dorsal midbrain astrocytes of mice induced the formation of a mixed population of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons57. Introducing additional transcription factors resulted in the more targeted and controlled production of specific neuronal cell types. For example, the overexpression of Dlx5 and Lhx6 together with Ascl1, but not Ascl1 alone, converted resident fibroblasts into GABAergic interneurons (iGABA-INs) in mouse brains58. These iGABA-INs exhibited electrical activity resembling that of cortical interneurons. More importantly, the iGABA-INs became functionally integrated into the endogenous neuronal networks and were capable of producing and releasing GABA58. The ectopic expression of Ngn3 alone in pancreatic acinar cells converted these cells into δ-cells, whereas the forced expression of Ngn3 together with Mafa reprogrammed mouse acinar cells to α-cells59. The addition of a third factor, Pdx1, resulted in the production of β-cells17. Furthermore, the native microenvironment also impacts on the generation of targeted cell subtypes. For example, the overexpression of GHMT in mouse cardiac fibroblasts maintained in culture resulted in the induction of diverse cardiac subtypes, including those resembling ventricular, atrial and conducting cardiomyocytes60, but the in vivo delivery of the same GHMT cardiac reprogramming factors around the infarcted area in the mouse ventricle generated mostly ventricular cardiomyocyte-like cells11.

The hurdles of in vivo direct reprogramming in regenerative medicine.

Studies from animal models and with cultured human cells have led to considerable progress in identifying suitable cell sources and controlling cell differentiation towards specific lineages. However, for clinical translation to become possible, it is essential to achieve robust reprogramming in diseased organs in a safe manner. Early studies relied on the use of viral vectors for the in vivo delivery of reprogramming factors. These viral vectors could integrate into the genome of host cells, with possible tumorigenic risks or other unexpected off-target effects resulting from the disruption of targeted genomic loci. Several integration-free delivery strategies have been developed, including sendai virus61, modified mRNA62, single guide RNA63,64 and nanoparticle-based gene carriers65 (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, direct reprogramming using small molecules has been explored. Small molecules have been shown to successfully reprogramme mouse66,67 and human68 cardiac cells as well as fibroblasts to iNs69–72 by inducing changes in transcriptional programmes. Compared with viral-based gene delivery methods, small molecules have the advantage of being non-immunogenic and cost-effective and of having related protocols that are easy to standardize73. Nevertheless, improvements are needed to extend the duration of small-molecule action and to precisely control the site where they function in vivo to allow maximal reprogramming efficacy and minimal side effects. Recent advances in hydrogel technology, which enable close matching of the physical properties of most tissues, may facilitate the delivery of small molecules in vivo74. Moreover, hydrogels could enable controlled drug release, extending the exposure of cells to small molecules.

Although in vivo direct reprogramming can outperform in vitro reprogramming in terms of the maturity and quality of the reprogrammed cells, further optimization is required for clinical translation. Advances in single-cell technology have increased our understanding of fate specification and differentiation trajectories75–77. Importantly, they have identified alternative reprogramming routes (that contribute to the heterogeneity of cells obtained by direct reprogramming) as well as the genes and mechanisms that control such routes and which must be inhibited to obtain the desired cell type and reduce heterogeneity. However, single-cell transcriptional profiling can only be performed on cells reprogrammed in vitro, which could behave very differently from cells reprogrammed in vivo. Valuable insights might be obtained from cells that are reprogrammed in 3D culture systems that mimic the tissue microenvironment such as organoids78 and a 3D-printed artificial heart79. An alternative strategy to optimize direct reprogramming is to identify barriers blocking efficient cell fate conversion. Using an unbiased loss-of-function screen, Bmi1 was recently identified as an epigenetic barrier for cardiac reprogramming80. The recent finding that knocking down Ptbp1 alone (which encodes an RNA-binding protein) enabled the conversion of mouse astrocytes to mature functional neurons in vivo with ~80% reprogramming efficiency provides further evidence that removing a key barrier can improve reprogramming outcomes81.

Other obstacles to clinical translation have been uncovered. For example, it was reported that, during reprogramming to iPSCs, cells from different age group donors displayed significant differences in reprogramming efficiency and yielded iPSCs with different degrees of genome instability82,83. Based on these findings in iPSCs, it will be necessary to study the amenability of patients from different genetic and age backgrounds to in vivo reprogramming and to establish standards to evaluate in vivo reprogramming efficacy and safety. Moreover, there is a need for comprehensive regulatory guidelines to standardize and coordinate the efforts from the academic and industry sectors. In summary, we believe that cross-disciplinary collaborations, combined with technical advances in single-cell omics, 3D imaging, tissue reconstruction and bioengineering, will enable us to overcome some of the challenges discussed above and open new avenues for therapeutic opportunities.

Molecular mechanisms of direct reprogramming

To optimize direct reprogramming, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms that regulate this process. In addition to transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms, new insights have been gained on the role of non-coding RNAs and metabolic factors.

Transcription factors are key players in lineage conversion.

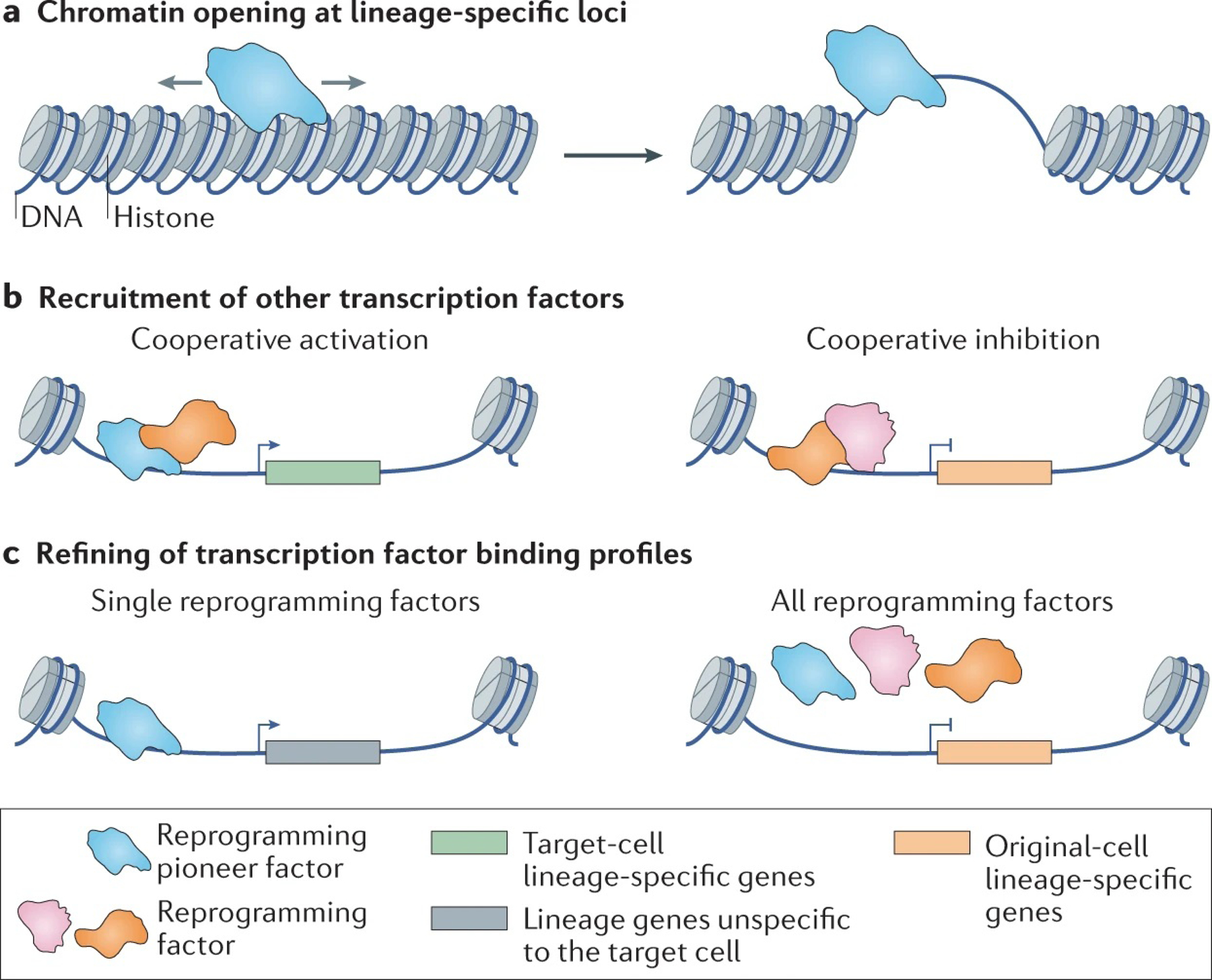

Lineage-specific transcription factors are the molecular foundation of direct reprogramming. During development, specific lineage gene expression is regulated, in part, by silencing some genetic loci (heterochromatic or in closed chromatin conformation) and activating others. Pioneer factors are a type of transcription factor that can bind and open closed chromatin to enable the binding of other canonical transcription factors84,85 (FIG. 3a, TABLE 1) and are therefore included in the majority of reprogramming factor combinations (FIG. 2). For example, Gata4 in cardiac reprogramming86 and Ascl1 in neuronal reprogramming20 are pioneer factors. Based on their binding patterns, pioneer factors can be categorized as ‘on-target’ and ‘off-target’. For example, Ascl1 is an on-target pioneer factor in neuronal reprogramming because it binds to lineage-specific target sites in starting cells, regardless of whether these sites are in an open or closed chromatin region87. Oct4, a well-known pioneer factor in iPSC reprogramming, is an example of an off-target pioneer factor as it binds to closed chromatin regions in a less-specific manner88. Pioneer factors also showed different potency to drive the reprogramming process. Ascl1 alone can efficiently convert fibroblasts to neurons89 whereas co-binding of Mef2 and Tbx5 with Gata4 is required to activate a cardiomyocyte gene programme in fibroblasts90. Thus, understanding the binding patterns and mechanisms and modifying transcription factors to increase their on-target binding could lead to simpler and more efficient reprogramming factor combinations.

Fig. 3 |. Functions of reprogramming factors during direct reprogramming.

a | At the initial stages of fate conversion, unlike other transcription factors, pioneer factors can access closed chromatin and bind to regions that are in an open conformation in the target cell type to allow cell type-specific gene expression. b | Reprogramming factors recruit other factors and work cooperatively to activate or inhibit target gene expression. c | Reprogramming factors could refine the binding profile of other reprogramming factors during direct reprogramming. The expression of a single reprogramming factor may induce the expression of lineage genes non-specific to the target cell type. The co-expression of other reprogramming factors limited such non-specific binding, thus refining the induced gene programme in the end-product cells.

Table 1 |.

Examples of functions of reprogramming factors during direct reprogramming

| Function | Reprogramming factor in action | Reprogramming cofactor | Starting cell type | Target cell type | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Act as a Pioneer factor | Ascl1 | – | Mouse embryonic fibroblast | Neurons | 87 |

| Gata4 | – | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 176 | |

| Myod1 | – | Fibroblast | Myoblasts | 2 | |

| FOXA1, FOXA2, FOXA3 | – | Fibroblast | Hepatocytes | 21 | |

| Cooperative activation | Ascl1, Brn2 | – | Mouse embryonic fibroblast | Neurons | 87 |

| Akt1, Gata4 | – | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 90 | |

| Tbx5, Gata4 | – | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 13 | |

| Gata4 | ZNF281 | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 176 | |

| Cooperative inhibition | Tbx5, Gata4 | – | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 13 |

| Refine the binding of other transcription factors | Ascl1, Brn2 | – | Mouse embryonic fibroblast | Neurons | 87 |

| Gata4, Tbx5, Mef2c | – | Mouse cardiac fibroblast | Cardiomyocytes | 13 |

Transcription factors can cooperate to activate gene expression and convert one cell type into another (FIG. 3b, TABLE 1). Ascl1 recruits Brn2 to many of its neuronal targets to induce cell-fate conversion and obtain iNs87. In cardiac reprogramming induced by the forced expression of AGHMT (Akt1, Gata4, Hand2, Mef2c and Tbx5)91, 50% of the DNA binding sites where cooccupied by at least two transcription factors90. These co-occupied transcription factor binding sites showed a stronger relationship to the heart-related transcription programme than sites with single factor occupancy. Such synergistic interaction among reprogramming factors was also observed in GMT-induced cardiac reprogramming18, where the regions bound by Tbx5 and Gata4 showed an almost fourfold increase in chromatin accessibility compared to those bound by Tbx5 or Gata4 alone13. Furthermore, the transcription factors have been reported to refine the binding profiles of other factors (FIG. 3c, TABLE 1). For example, the binding pattern of the cardiac reprogramming factors in GMT, when expressed individually, differed from that detected with all three factors being expressed together13.

Despite functioning cooperatively, reprogramming factors do not seem to be equally important for the successful conversion and maturation of target cell types. Compared with Tbx5 and Gata4, Mef2c plays a key role in the initial up-regulation of cardiac gene expression and late maturation of iCMs by activating cardiac-specific enhancers13,90 despite lacking pioneering ability to bind heterochromatin regions; therefore, high levels of Mef2c and low levels of Gata4 and Tbx5 are required for efficient cardiac reprogramming both in vitro and in vivo75,92–94. Among three neuronal reprogramming factors (Ascl1, Brn2 and Myt1l), the sustained expression of Ascl1 is more important for the efficient production of iNs77. Moreover, despite all FOXA proteins functioning as pioneer factors in direct hepatocyte reprogramming, FOXA3 has the unique potential to bind RNA polymerase II and co-traverse target genes95. These differences between reprogramming factors highlight the importance of an optimal dosage ratio for successful reprogramming and specification of cell lineage.

DNA accessibility during reprogramming.

The forced expression of reprogramming factors induces drastic changes in chromatin accessibility, an aspect that influences the efficiency and outcome of reprogramming. Recently, studies using ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing) revealed that chromatin remodelling occurs as early as 12 hours upon introduction of reprogramming factors and that most changes in chromatin accessibility are at distal regions from the transcription start sites13,96. Three major types of changes were observed: stable decrease, stable increase or transient reconfiguration of chromatin accessibility. Generally, the open chromatin regions that define the original cell type showed the strongest loss of chromatin accessibility after the induction of reprogramming factors, indicative of transcriptional repression96. During the conversion of mouse neonatal cardiac fibroblasts to iCMs, most regions that became stably accessible showed maximal accessibility at 3 days post-induction and were associated with genes related to cardiac and striated muscle development13. However, regions that only showed a transient increase in accessibility during the initial phase of reprogramming were annotated with cardiac function (characteristic of mature cells), indicating that additional factors are required to stabilize such interactions and enable iCM maturation13.

Changes in chromatin accessibility during reprogramming are believed to result from the cooperative interaction of reprogramming factors. For example, almost all regions that gained accessibility during cardiac reprogramming showed significant enrichment of GMT binding13. However, there are regions with decreased chromatin accessibility also bound by GMT13. Such variations on the effects of transcription factor binding have also been observed for the regions bound individually by Mef2c and Tbx5, suggesting a context-dependent effect on chromatin conformation13. However, Ascl1 binding seems to only increase chromatin accessibility during neuronal reprogramming96, which has been attributed to the intrinsic strong affinity of Ascl1 to the nucleosome84. Thus, chromatin conformation changes are dependent on the properties of the transcription factors involved and on the chromatin context.

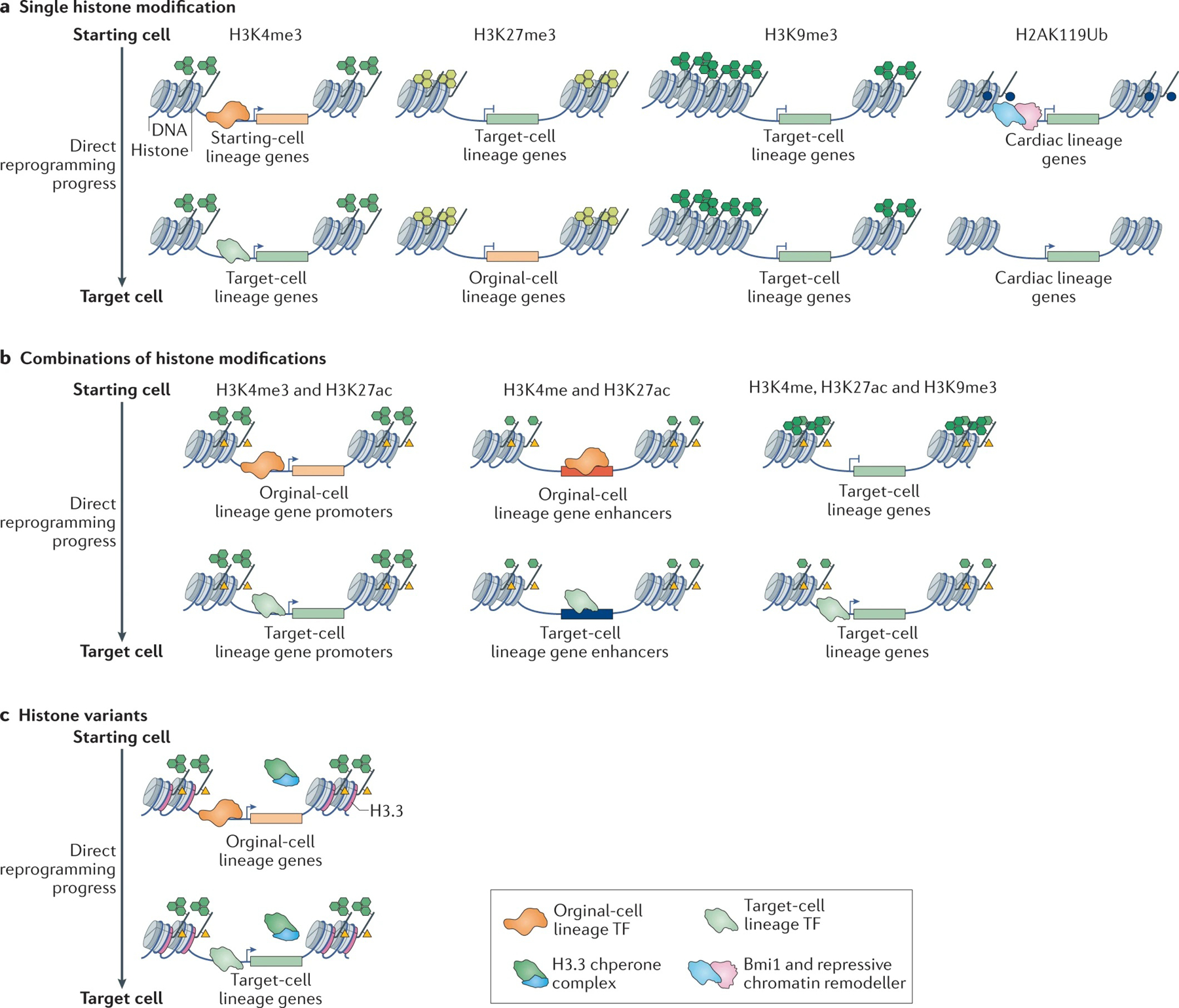

Histone modifications that affect fate conversion.

Histone post-translational modifications, such as methylation, phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitylation, are catalysed by different histone modifiers and can regulate gene expression by acting as signals that recruit specific effectors97. The epigenetic regulation by histone modification during direct reprogramming has been characterized in great detail (FIG. 4).

Fig. 4 |. Histone modifications that regulate gene expression during direct reprogramming.

a | The types and functions of single histone modifications during direct reprogramming. H3K4me3, a histone modification that is associated with active transcription, serves as a hallmark for successful activation of the transcriptional programme that is characteristic of the desired cell type. H3K27me3, a repressive histone modification, can be used as a marker of successful silencing of the starting cell transcriptional programme. H3K9me3 is a histone modification that is associated with heterochromatin, which is refractory to transcription activation and constitutes a major barrier for successful reprogramming. H2AK119Ub is a repressive mark that has been identified at cardiac-specific loci in fibroblasts and the removal of this epigenetic mark enhances cardiac reprogramming. b | The types and functions of different combinations of histone modification during direct reprogramming. The co-enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K27ac marks the promoters of expressed genes and genes that become activated during reprogramming. The simultaneous presence of H3K4me and H3K27ac marks the enhancers of active genes. The coexistence of H3K4me, H3K27ac and H3K9me3 (trivalent chromatin) promotes the binding of Ascl1 to neuron-specific genes during the conversion of fibroblasts to induced neurons and is an indicator of the efficiency of Ascl1-driven induced neuron reprogramming. c | Histone variants play a part in reprogramming. The histone H3 variant H3.3 has a dual role during direct reprogramming: it is important for the maintenance of the gene expression programme of the starting cell type at early stages of reprogramming and is required for the establishment of the gene expression programme of the desired cell lineage in the late stages of reprogramming. TF, transcription factor.

The trimethylation of histone 3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) is strongly enriched at promoters of transcriptionally active genes. H3K4me3 marks lineage-specific genes and serves as a hallmark of activation of the transcriptional programme of the target cell (FIG. 4a). During mouse cardiac reprogramming, H3K4me3 marks were rapidly deposited at the promoters of cardiac loci and removed at a slower pace from promoters of fibroblast-specific genes98. During direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors cells (NPCs), a strong enrichment in H3K4me3 was observed on day 8 at the promoter of Sox1, and the levels of H3K4me3 became similar to those seen in adult NPC by day 12 (REF.99). The establishment of H3K4me3 on chromatin seems to be required for complete cell fate conversion and functions as an indicator of successful reprogramming. Knockdown of Kmt2b (a histone methyltransferase that catalyses H3K4me3) during neuronal reprogramming from MEF greatly reduced the efficiency of iN generation and led to cells adopting an alternative myocyte fate100. H3K4me3 was found in a large chromatin domain, spanning up to 60 kb, mainly containing cell identity genes101. The promoters of 10 out of 13 known induced neural stem cell reprogramming factor were found to be marked in this broad H3K4me3 domain101. Thus, identifying the broad H3K4me3 domain and its associated genes might lead to the identification of new reprogramming factors.

H3K27me3 is a histone modification that is tightly associated with transcription repression. Accordingly, cardiac genes were shown to progressively lose H3K27me3 at their promoters, and fibroblast-specific genes gradually gained H3K27me3 at late stages of cardiac reprogramming98 (FIG. 4a). The inhibition of H3K27me3 methyltransferases by small-molecule inhibitors or siRNA facilitated the induction of a cardiogenic programme in miRNA-mediated reprogramming of mouse cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes102,103. H3K9me3 is another repressive histone modification. Compared with the regions marked with H3K27me3, which remain accessible to the binding of transcription factors and RNA polymerase104, transcription factors do not bind to H3K9me3-marked heterochromatin (FIG. 4a). Consistently, during human hepatocyte reprogramming, hepatic genes that are marked by H3K9me3 in fibroblasts are refractory to transcriptional activation105,106. By contrast, hepatic genes marked by H3K27me3 showed a modest increase in transcription activation106. Knockdown of the H3K9me3 reader RBMX or of the writer SUV39H1 promoted the expression of hepatic genes at early reprogramming stages106. Similarly, disrupting H3K9me3 deposition at the early stages of reprogramming by treating cells with the histone methyltransferase inhibitor UNC0638 increased the efficiency of mouse cardiac reprogramming107. However, erasing H3K9me3 prior to mouse neuronal reprogramming resulted in fewer iN cells, suggesting that H3K9me3 should only be erased temporarily to enable reprogramming87.

Histone acetylation is positively correlated with gene expression. H3K27ac distinguishes active enhancers from inactive and poised enhancers. During reprogramming to iN and iCM, H3K27ac marks enhancers and shows a strong positive correlation with reprogramming factor binding at the early stages of fate conversion87,90 (FIG. 4a). H3K27ac also marks super-enhancers, which are clusters of enhancers that control cell type-specific genes and are important for the establishment of cell identity108. Activated super-enhancers that carry the H3K27ac modification are bound by lineage-specific transcription factors. During the conversion of mouse embryonic stem cells to trophoblast stem-like cells, half of the super-enhancers specific to trophoblasts were found to be bound by reprogramming factors109. However, the role of super-enhancers during direct reprogramming remains largely unexplored.

The ubiquitylation of histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119Ub) and of histone H2B at lysine 120 (H2BK120ub) has been linked to both the activation and silencing of gene transcription depending on the genomic context110. During mouse cardiac reprogramming, cardiomyocyte-specific loci that are bound by Bmi1 in fibroblasts were marked by the H2AK119Ub modification and the same region contained binding sites for Ring1B and Ezh2, two repressive chromatin remodellers80 (FIG. 4a). The depletion of Bmi1 led to the complete removal of H2AK119Ub at these loci and significantly enhanced the efficiency of reprogramming to iCM, suggesting that H2K119Ub impedes cardiac reprogramming.

Multiple histone modifications can mark the same histone to cooperatively regulate transcription (FIG. 4b). For example, active enhancers are marked by H3K4me1 and H3K27ac and active promoters are marked by H3K4me3 and H3K27ac. In some cases, the same chromatin region can have both repressive and active histone modifications, as best exemplified by the antagonistic histone modifications H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (REF.111). These bivalent marks are important during embryonic development; they mark lineage-specific genes in stem or progenitor cells, maintaining the genes in a silent but poised transcriptional state that can rapidly become activated upon receiving the right environmental cues112. In pancreatic α-cells, the bivalent signature was found on genes that control the β-cell programme, suggesting that the poised state of the β-cell transcriptional programme in α-cells could be one of the features underlying the easy conversion of α-cells to β-cells56. During direct reprogramming to iNs, trivalent chromatin domains, marked by H3K27ac, H3K4me1 and H3K9me3, were more accessible to Ascl1 binding, enabling its binding to target loci87. The enrichment of the trivalent chromatin state on neuronal fate-specific genes in different starting cell types has been associated with higher neuronal reprogramming efficiency, suggesting the importance of the trivalent state for Ascl1 to induce the neuron-specific transcriptional programme. Thus far, there is only one report of the trivalent chromatin state being important for direct reprogramming; it will be interesting to investigate whether trivalent domains have a regulatory function during other reprogramming processes.

Histone variants in direct reprogramming.

Non-canonical histone variants differ from their canonical isoforms in one or few amino acid residues and are incorporated in the genome independently of DNA replication113,114. Histone variants play an important part in the production of iPSCs115–117 but their role in direct reprogramming is largely unexplored. Only H3.3 has been found to have a dual role in direct reprogramming: maintaining the starting fibroblast lineage gene expression programme during early stages of reprogramming and establishing the haematopoietic cell lineage gene expression programme at late stages of reprogramming117,118 (FIG. 4c).

DNA methylation is crucial for gene silencing during reprogramming.

A global reconfiguration of DNA methylation was observed during cardiac, neuronal and pancreatic reprogramming. During conversion to iCMs, the promoters of two genes that define the cardiac lineage, Myh6 and Nppa, became demethylated soon after GMT induction98. During reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to iNs, the pattern of genomic methylation was modified to resemble that of mature cortical neurons following the forced expression of neuron-inducing factors119. Specifically, Ascl1 expression induced the de novo methylation of fibroblast-specific gene promoters by increasing the expression of the DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a119. The ablation of Dnmt3a during neuronal reprogramming significantly reduced the reprogramming efficiency119. A rapid global change in DNA methylation, particularly at pancreatic gene loci, was also observed during the first 10 days of direct reprogramming of acinar cells to pancreatic β-cells43. Thus, the reconfiguration of the global DNA methylation landscape is crucial for cell fate conversions that are controlled by the cooperative interactions of reprogramming factors.

Non-coding RNAs as new players in the regulation of direct reprogramming.

MicroRNAs are ∼23-nucleotide RNAs that regulate gene expression at the post-translational level, and a single microRNA typically targets multiple pathways simultaneously120. Owing to their small size, microRNAs can be delivered to cells more efficiently than the DNA or mRNA encoding transcription factors. Therefore, microRNAs have been used to further refine direct reprogramming (Supplementary Table 2). For cardiac reprogramming, the addition of miR-133a to the ‘traditional transcription factor combination’ improved the reprogramming efficiency of both mouse and human fibroblasts by silencing multiple downstream effectors121. These factors included SNAI1 (a master regulator of epithelial–mesenchymal transition), NCOA7 (a transcription co-activator), XPO4 (a bidirectional nuclear transport receptor) and RQCD1 (a component of CCR4-NOT mRNA deadenylases complex)76. A similar finding has been made for neuronal reprogramming with miR-9/9* and miR-124 (REFs122–124). During the conversion of adult human fibroblasts to neurons, the ectopic expression of miR-9/9* and miR-124 induced a reconfiguration of chromatin accessibility and DNA methylation123 and also disrupted the expression of RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST), a transcription repressor of neuronal genes in non-neuronal cells125–127.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are longer than 200 nucleotides and have been shown to regulate gene expression through the modulation of epigenetics and 3D chromosome structure128. Interestingly, different isoforms of lnc-NR2F1, the only lncRNA thus far found to be involved in reprogramming, have opposite effects on the reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to iNs, suggesting that a delicate balance between isoforms controls neuronal fate129. Given the prominent role of lncRNAs in development and iPSC reprogramming, lncRNAs are expected to exert various functions as either barriers or facilitators to direct reprogramming130–136.

Metabolic switch for functional reprogramming.

Cell fate conversions involve major metabolic changes because of the differences in metabolism between starting and target cells. Metabolic remodelling is important for direct reprogramming as well as for reprogramming to pluripotency137–140.

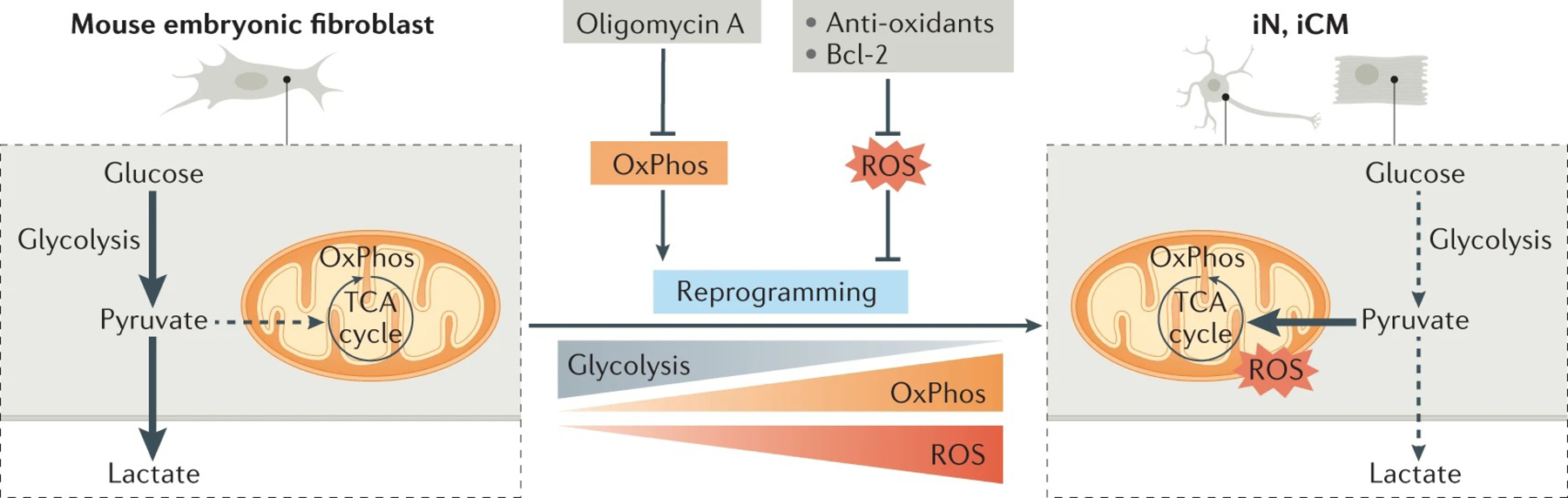

Direct reprogramming from fibroblasts to neurons involves a switch from glycolytic metabolism to oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos)141 (FIG. 5). A gradual increase in the expression of genes involved in OxPhos was also observed during the conversion of fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes75. Consistent with fatty acid oxidation being the major energy source for adult cardiomyocytes142, the genes related to fatty acid oxidation were activated in fibroblast-derived iCMs143. More importantly, the inhibition of OxPhos by oligomycin A treatment completely abolished the reprogramming from mouse fibroblast into iNs induced by Ascl1 and Neurog2 (REF.140).

Fig. 5 |. Metabolic switch during direct reprogramming.

The switch from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) is important for direct reprogramming both in vitro and in vivo. Treating mouse embryonic fibroblasts with oligomycin A, an inhibitor of OxPhos, completely abolished the reprogramming of these fibroblasts to induced neurons (iNs) following overexpression of Ascl1 and Neurog2. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a by-product of the glycolysis-to-OxPhos switch, and aberrantly high levels of ROS could impede cell fate conversion. The overexpression of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, or treatment with anti-oxidant compounds, such as vitamin E or α-tocotrienol, drastically increased the efficiency of reprogramming to iNs both in vitro and in vivo. Exposing the cardiac fibroblast to an anti-oxidant (selenium) led a 5–15-fold increase in reprogramming efficiency when mouse cardiac fibroblasts were induced to convert to induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) in vitro via the forced expression of microRNAs. TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

OxPhos in mitochondria generates reactive oxygen species (ROS)144. Low levels of ROS are believed to be crucial for metabolic adaptation145 and promote direct reprogramming, but high levels of ROS induce the apoptotic pathway and cell death146. Aberrantly high levels of ROS could inhibit efficient direct fate conversion (FIG. 5). Indeed, cell death caused by lipid peroxidation prevented Ascl1-induced fate conversion from fibroblasts into iNs140. The overexpression of Bcl-2 (an anti-apoptotic protein) or treatment of anti-oxidant compounds reduces ROS and therefore increases Ascl1-mediated neuronal reprogramming efficiency to ~90%140. Similarly, treatment with selenium, an anti-oxidant, enhanced the efficiency of cardiac reprogramming using mouse cardiac fibroblasts by 5–15-fold147, suggesting that excessive ROS generation is a major barrier to direct reprogramming.

New mechanistic insights from single-cell omics

Direct reprogramming is a heterogeneous and unsynchronized process. Using traditional population-based techniques for genomic analyses, such as bulk RNA-seq and ChIP-seq, de novo epigenetic and transcriptome changes in the heterogeneous reprogramming cell populations cannot be precisely captured. Thus, analysing heterogeneous cell populations at the single-cell level will greatly facilitate the study of direct reprogramming. Since the development of the very first mRNA profiling method to study mouse blastomeres148, we have witnessed rapid advancement of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies149. Droplet-based platforms for microfluidics (for example, Drop-seq150 and GemCode151) are able to manipulate and screen thousands to millions of cells at a low cost. Profiling at such a high throughput provides valuable insights to the molecular trajectory of direct reprogramming in greater detail. A typical scRNA-seq analysis involves three steps: clustering, trajectory analysis and identification of the differentially expressed genes. Here, we review how these analyses have shed light on the mechanisms of direct reprogramming.

Unsupervised clustering uncovers heterogeneity in the starting cell population.

scRNA-seq has provided the unprecedented opportunity to delineate the transcriptomes of biological samples at single-cell resolution. One essential step in the analysis of scRNA-seq data is the unsupervised clustering of individual cells based on the similarity of their transcriptomes, with the aim to define and characterize putative distinct cell types from a heterogeneous group of cells152. One important question is whether the heterogeneity observed during direct reprogramming (that is, the production of a variety of cell types) is in part due to the heterogeneity of the starting cell population. To address this question, scRNA-seq was performed on murine neonatal cardiac fibroblasts that have been commonly used as the starting cells for cardiac reprogramming. Unsupervised clustering identified multiple subpopulations in the starting fibroblast populations: endothelial-like, epicardial cell-like and macrophage-like cells13,75. During cardiac reprogramming, the molecular features of these subpopulations are gradually suppressed75 regardless of their initial gene programmes, suggesting that heterogeneous reprogramming is not solely due to heterogeneity in the starting population.

Another major factor contributing to the heterogeneity of reprogramming is the difference in cell cycle genes among starting subpopulations13,75–77. It seems that, for neuronal reprogramming, the heterogeneity of starting MEF was mainly attributable to the difference in the expression of cell cycle-related genes77. In cardiac reprogramming, the switch from proliferating cardiac fibroblasts to mostly cell cycle-inactive pre-iCMs and iCMs suggests a potential involvement of cell cycle alteration in the regulation of cardiac reprogramming75 that might be different from its role in de novo cardiomyocyte proliferation in the context of cardiac injury and repair153–156. By inhibiting the proliferation or cell cycle synchronization of cardiac fibroblasts, the efficiency of cardiac reprogramming could be significantly increased, highlighting a negative impact of active cell cycles on direct reprogramming75.

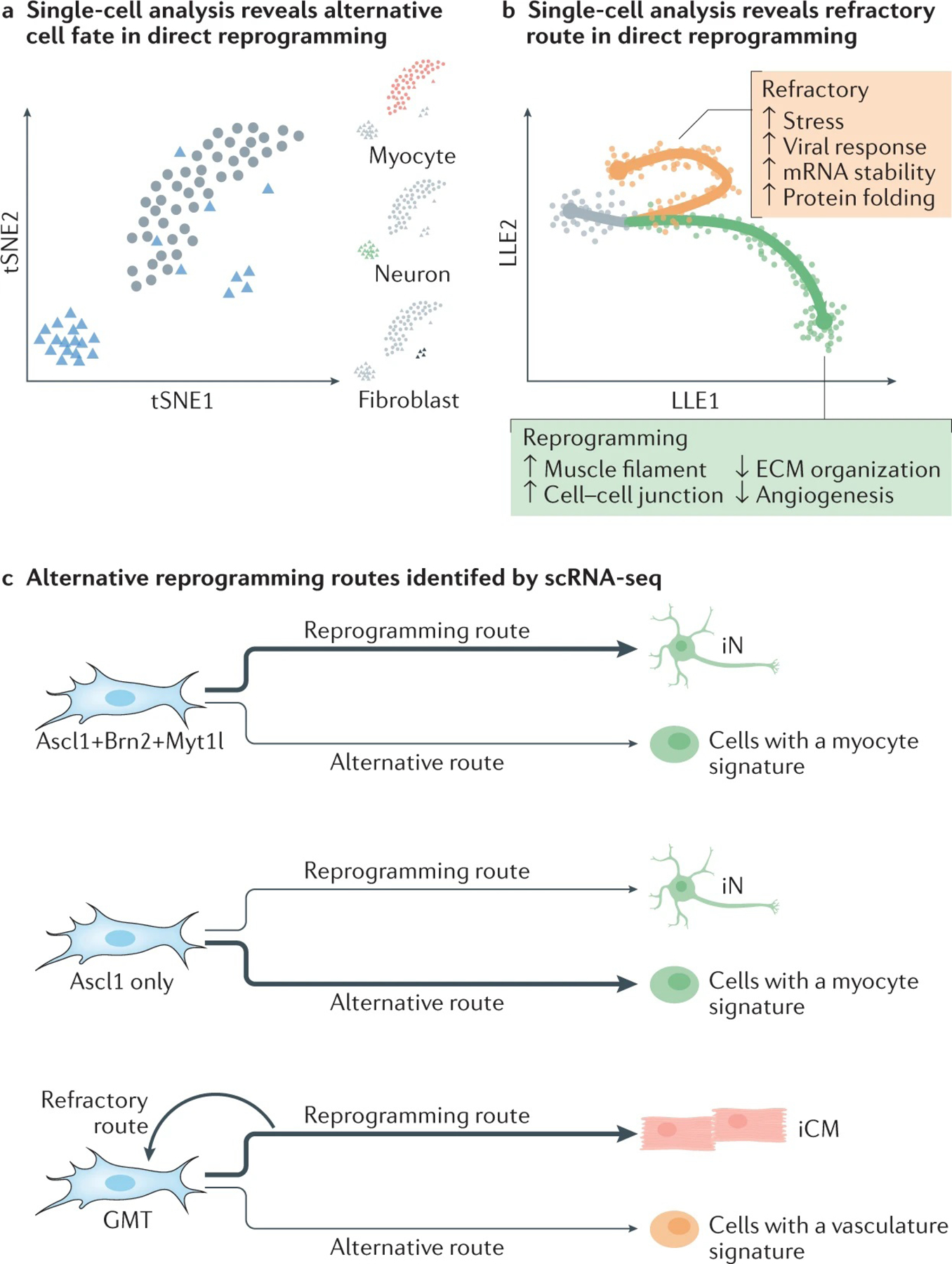

Unsupervised clustering has also been used to examine the molecular features of the reprogramming cells. Clustering of single neuronal reprogramming cells from MEFs at day 22 post-induction of reprogramming factors (Brn2, Ascl1 and Myt1l, also called BAM) identified three transcriptionally distinct clusters: fibroblast, neuron and myogenic clusters, suggesting an alternative route in neuronal reprogramming to myogenic cell fate77 (FIG. 6a). Further study comparing the mechanisms between Ascl1-mediated and BAM-mediated conversion to iNs demonstrated that the reprogramming factors Brn2 and Myt1l suppressed the alternative myogenic programme. Similarly, in GMT-mediated reprogramming of mouse cardiac fibroblasts into iCMs, unsupervised clustering revealed cell clusters with transcriptional signatures of vasculature and blood vessel development, suggesting that cells can acquire a fate different from iCMs during reprogramming13. While scientists are harnessing scRNA-seq to identify rare populations in direct reprogramming, it is important to note that it is not always clear what constitutes a cell type at the transcriptional level; thus, great caution needs to be taken when interpreting the clustering results, especially those that led to the discovery of novel cell types or intermediate cell states or those lacking sufficient signature markers or functional annotations.

Fig. 6 |. Single-cell omics in direct reprogramming.

Computational approaches that produce information on reprogramming trajectories based on single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data facilitate the identification of alternative routes in both direct neuronal and cardiac reprogramming. Two examples of the type of information that can be obtained are shown. a | Clustering analysis based on scRNA-seq at the late stages of Ascl1-mediated (circle) or BAM-mediated (triangle) neuronal reprogramming showed three distinct cell clusters with specific lineage gene expression of neuron (red), fibroblast (blue) and myocyte (green) fate, suggesting the existence of an alternative cell fate at the late stage of neuronal reprogramming. The plot is modified based on the data from REF.77. b | Trajectory analysis revealed two separate paths in human cardiac reprogramming. When cells engage in a ‘reprogramming path’, they gradually acquire a cardiomyocyte cell fate; however, cells can also follow a ‘refractory route’ and revert towards a fibroblast cell fate. Differential gene expression analysis identified genes involved in different pathways or cellular processes that are activated or suppressed while cells follow either route. The plot is modified based on the data in REF.76. c | The alternative reprogramming outcomes of direct reprogramming revealed by scRNA-seq analysis. In neuronal reprogramming mediated by Ascl1 only, most of the cells gained a transcription programme similar to myocytes. The addition of Brn2 and Myt1l suppressed the aberrant myogenic programme. In cardiac reprogramming mediated by Gata4, Mef2c and Tbx5 (GMT), most of the cells successfully gained a cardiac programme as expected. A small population of cells gained transcription signatures of vasculature and blood vessel development. scRNA-seq analysis of human cardiac reprogramming also revealed the existence of a refractory route where the cells reverted to a fibroblast fate. ECM, extracellular matrix; iCM, induced cardiomyocyte; iN, induced neuron; LLE, locally linear embedding; tSNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding. Part a adapted from REF.76, Springer Nature Limited; part b adapted with permission from REF.77, Elsevier.

Trajectory analysis to delineate the route of direct reprogramming.

Another important application of scRNA-seq is the reconstruction of cellular dynamics processes whereby the individual cells are ordered along a temporal trajectory (or pseudotime) according to their similarities in gene expression profiles157,158. In direct reprogramming, trajectory analysis revealed that successful reprogramming is determined at the early phase of conversion, in contrast to iPSC reprogramming, which is believed to be a stochastic process at the initial stage and a deterministic process at the late stage159. By projecting the vectors of RNA velocity160 onto the trajectory field of cardiac reprogramming, an early decision point before or on day 3 of reprogramming was revealed76. Trajectory analysis could also help to reveal novel cell states during direct reprogramming. Based on the pseudotemporal orders of the cells undergoing fate switch from fibroblasts to iNs, reconstruction of the reprogramming path led to the identification of a unique intermediate cell state. The cells in this state had a transcriptomic profile similar to that of the NPC with an apparent lack of canonical NPC marker expression77. In mouse cardiac reprogramming, trajectory analysis revealed three distinct outcomes: one with successful activation of cardiac genes, another one with progressive activation of a vasculature-related programme13 and the third one being unsuccessfully reprogrammed with active proliferation13,75. In human cardiac reprogramming, two separate paths were identified by trajectory analysis: the reprogramming route that leads to the iCM fate and the refractory route that pulls the cells back to the initial fibroblast fate76 (FIG. 6b). Further differential gene expression analysis revealed the successful acquirement of a cardiomyocyte-related transcription programme in fibroblasts on the reprogramming route and an upregulation of stress and viral response genes on the refractory route76.

Integration of single-cell multi-omics datasets is the next opportunity and challenge.

In the past decade there has been a rapid development of single-cell technologies149. scRNA-seq can be used to profile hundreds of thousands of single cells from one sequencing library, substantially reducing the cost of single-cell profiling and making large-scale profiling of a biological process of interest increasingly affordable and more achievable. With such valuable published datasets161, the integrative analysis of cells across multiple studies (or batches) enables researchers to detect rare populations that could not be robustly identified by analysing individual datasets and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a biological process162. However, the existence of batch effects caused by the systematic technical (non-biological) biases among different batches during an experiment presents a major challenge for integrative analyses across multiple scRNA-seq datasets, which may lead to misinterpretation163 (Supplementary Box). Although many computational tools have been developed for batch-effect correction, current methods are suffering from the trade-off between under-correction (not all batch effects are properly corrected) and over-correction (true underlying biology is erased during the correction). One has to bear in mind these caveats and choose the appropriate algorithms for batch-effect corrections when applying scRNA-seq to study a direct reprogramming process.

In addition to scRNA-seq, other types of single-cell technologies are being developed such as single-cell ChIP-seq, single-cell ATAC-seq and single-cell Hi-C data164–171 (BOX 2). The integration of datasets generated using these approaches from multiple experimental protocols or cellular features enables researchers to more comprehensively characterize cell features simultaneously than through a single task162,172. For example, a joint analysis of single-cell transcriptomics and epigenetic data revealed that changes in gene expression occur before changes in DNA methylation during the reprogramming of human fibroblasts into iPSCs173,174. However, given the difficulty to discover relationships across different single-cell datasets that are not measured in parallel using the same workflow, it remains a significant challenge to build a single statistical framework capable of optionally integrating multi-omics single-cell assays under all scenarios175. In the next few years, there will be an explosion of multiplex single-cell omics datasets for various direct reprogramming processes. Although extremely exciting, such tremendous growth of omics datasets inevitably demands a parallel development of analytical methods and close collaboration among computer scientists and cell biologists.

Box 2 |. Multi-omics single-cell assays.

There has been great progress in single-cell technologies in the last decade beyond single-cell RNA technologies. Single-cell assays can profile different cell features: DNA methylation (bisulfite sequencing), open chromatin status (ATAC-seq) and chromatin interactions (Hi-C). Single-cell DNA methylation profiling analyses the genome-wide methylation status of CpG islands in single cells by bisulfite-based or bisulfite-free methods184. Single-cell ATAC-seq generates single-cell chromatin accessibility profiles with the hyperactive transposase Tn5, which inserts sequencing adapters into accessible chromatin185. Single-cell ATAC-seq thus identifies active DNA regulatory elements on a genome-wide scale186. Single-cell Hi-C technology quantifies the spatial proximity of distal regulatory elements in a 3D space (for example, the interactions between promoters and enhancers), which can provide new insights into chromosome structure and transcriptional regulation mechanisms169,187,188. Importantly, it is now possible to simultaneously profile gene expression, DNA methylation and chromatin architecture in the same cell187,189–191. We anticipate that these new multi-omics single-cell assays will provided a better understanding of the gene regulatory landscape during cellular reprogramming.

Conclusions and perspectives

Direct reprogramming has created a new paradigm in cell biology and provides a unique and efficient way to generate a cell type of interest for both basic research and translational applications. Given the unique advantages of in situ conversion in a live organ, direct reprogramming holds great promise as a treatment for many types of human diseases. For other somatic cell types that have not been generated by direct reprogramming, leveraging the new technologies such as CRISPR–Cas9 screen and computational modelling, one can predict reprogramming factors for the desired lineage that could be followed by experimental validation. Moreover, the discovery of small molecules, non-coding RNAs and synthesized proteins that can be delivered in vivo in a safe and controllable way is opening new potential avenues for clinical application. The rapid advances in single-cell omics technology enables us to investigate the mechanisms of direct reprogramming with unprecedented precision and resolution. Together, these advances, combined with interdisciplinary collaborations, are opening numerous opportunities for a better understanding of cell fate conversion and for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Myoblasts.

The embryonic precursors of myocytes (muscle cells).

Eosinophils.

A type of white blood cell containing granules that could be intensively stained with eosin.

Embryonic germ layer.

A layer of cells that form at the early stages of embryonic development. The three embryonic germ layers are the endoderm, ectoderm and mesoderm. Cells in each germ layer interact with each other and differentiate to form tissues and embryonic organs.

Autologous cell therapies.

A novel therapeutic intervention that utilizes patients’ own cells to obtain therapeutic cells through ex vivo differentiation or reprogramming.

Microenvironment.

The surrounding environment of a cell that contains chemical and physical signals that directly or indirectly regulate cellular behaviour.

Macroglial cells.

The non-neuronal cells that provide support and protection for neurons.

Sendai virus.

A single strand, negative-sense RNA virus that has a large capacity for gene expression and a wide host range.

Single guide RNA.

RNA molecule that contains a short sequence complementary to the target DNA sequence and is used to direct Cas9 endonuclease to target loci.

Hydrogel.

A network of polymer chains that are hydrophilic and has been extensively studied as a scaffold for in vivo drug delivery.

Poised enhancers.

A subclass of enhancers enriched for both the active and the repressive histone marks. In pluripotent cells, these poised enhancers are located near key early developmental genes and are primed to activate target gene expression upon the right environmental cues.

DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a.

Dnmt3a is an enzyme that catalyses the addition of methyl groups to unmethylated DNA at specific CpG sites.

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition.

The process where polarized epithelial cells are transformed into mobile and extracellular matrix-secreting mesenchymal cells.

Oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos).

A process in which ATP is produced because of electron transfer in mitochondria. OxPhos is the main energy source for cells like neurons, cardiomyocytes or muscle-skeletal cells.

Reactive oxygen species (ROs).

A natural by-product of the electron transport chain during the oxidation of glucose. ROs can act as signalling molecules; high levels of ROs can lead to oxidative stress in a cell.

Glycolysis.

A metabolic pathway that converts glucose to pyruvate and produces two ATPs. In proliferating cells, glycolysis is a major resource for energy and macromolecules for biosynthesis.

Microfluidics.

The precise control and manipulation of fluids at a small scale.

RNA velocity.

The time derivative of the gene expression state. It can be used to predict the future state of individual cells on a timescale of hours.

CpG islands.

short interspersed DNA sequences that are 1,000 base pairs on average and show an unusually elevated level of CpG dinucleotides. Most of the CpG islands are found at gene promoters.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely apologize to those whose work may not have been cited owing to space constraints. J.L. is supported by NIH/NHLBI R01HL139880, R01HL139976; L.Q. is supported by AHA 18TPA34180058, NIH/NHLBI R01HL128331, R01HL144551.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-021-00335-z.

References

- 1.Waddington CH The Strategy of the Genes. A Discussion of Some Aspects of Theoretical Biology. With an Appendix by H. Kacser (George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1957). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis RL, Weintraub H & Lassar AB Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 51, 987–1000 (1987).Davis et al. demonstrated, for the first time, that the overexpression of one transcription factor could rewrite cell fate in vitro.

- 3.Takahashi K & Yamanaka S Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamanaka S Induced pluripotent stem cells: past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell 10, 678–684 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buganim Y, Faddah DA & Jaenisch R Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat. Rev. Genet 14, 427–439 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K & Yamanaka S A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 17, 183–193 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith ZD, Sindhu C & Meissner A Molecular features of cellular reprogramming and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 17, 139–154 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava D & DeWitt N In vivo cellular reprogramming: the next generation. Cell 166, 1386–1396 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorstad NL et al. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature 548, 103–107 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H & Chen G In vivo reprogramming for CNS repair: regenerating neurons endogenous glial cells. Neuron 91, 728–738 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian L et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature 485, 593–598 (2012).Qian et al. demonstrated the feasibility of using in vivo direct reprogramming for heart repair.

- 12.Cahan P et al. CellNet: network biology applied to stem cell engineering. Cell 158, 903–915 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone NR et al. Context-specific transcription factor functions regulate epigenomic and transcriptional dynamics during cardiac reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 25, 87–102.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulessa H, Frampton J & Graf T GATA-1 reprograms avian myelomonocytic cell lines into eosinophils, thromboblasts, and erythroblasts. Genes Dev 9, 1250–1262 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R & Graf T Stepwise reprogramming of B cells into macrophages. Cell 117, 663–676 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Xie H, de Andres-Aguayo L & Graf T Reprogramming of committed T cell progenitors to macrophages and dendritic cells by C/EBPα and PU.1 transcription factors. Immunity 25, 731–744 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J & Melton DA In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to β-cells. Nature 455, 627–632 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ieda M et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell 142, 375–386 (2010).Idea et al. identified reprogramming factors that could reprogramme mouse cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocyte-like cells in vitro.

- 19.Song K et al. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature 485, 599–604 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vierbuchen T et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature 463, 1035–1041 (2010).Vierbuchen et al. identified a combination of three factors to directly convert mouse fibroblasts into functional neurons in vitro.

- 21.Sekiya S & Suzuki A Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature 475, 390–393 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang P et al. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature 475, 386–389 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoo AS et al. MicroRNA-mediated conversion of human fibroblasts to neurons. Nature 476, 228–231 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayawardena TM et al. MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res 110, 1465–1473 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayawardena TM et al. MicroRNA induced cardiac reprogramming in vivo. Circ. Res 116, 418–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu J, Du Y & Deng H Direct lineage reprogramming: strategies, mechanisms, and applications. Cell Stem Cell 16, 119–134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi J Strategies for bringing stem cell-derived dopamine neurons to the clinic: the Kyoto trial. in Progress in Brain Research 230, 213–226 (Elsevier B.V., 2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker RA, Parmar M, Studer L & Takahashi J Human trials of stem cell-derived dopamine neurons for Parkinson’s disease: dawn of a new era. Cell Stem Cell 21, 569–573 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarbin M, Sugino I & Townes-Anderson E Concise review: update on retinal pigment epithelium transplantation for age-related macular degeneration. Stem Cell Transl. Med 8, 466–477 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blau HM & Daley GQ Stem cells in the treatment of disease. N. Engl. J. Med 380, 1748–1760 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H & Chen G In vivo reprogramming for CNS repair: regenerating neurons from endogenous glial cells. Neuron 91, 728–738 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayawardena TM et al. MicroRNA induced cardiac reprogramming in vivo evidence for mature cardiac myocytes and improved cardiac function. Circ. Res 116, 418–424 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niu W et al. In vivo reprogramming of astrocytes to neuroblasts in the adult brain. Nat. Cell Biol 15, 1164–1175 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grande A et al. Environmental impact on direct neuronal reprogramming in vivo in the adult brain. Nat. Commun 4, 2373 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo Z et al. In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell Stem Cell 14, 188–202 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torper O et al. Generation of induced neurons via direct conversion in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 7038–7043 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heinrich C et al. Sox2-mediated conversion of NG2 glia into induced neurons in the injured adult cerebral cortex. Stem Cell Rep 3, 1000–1014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su Z, Niu W, Liu ML, Zou Y & Zhang CL In vivo conversion of astrocytes to neurons in the injured adult spinal cord. Nat. Commun 5, 3338 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song G et al. Direct reprogramming of hepatic myofibroblasts into hepatocytes in vivo attenuates liver fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 18, 797–808 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao K et al. Restoration of vision after de novo genesis of rod photoreceptors in mammalian retinas. Nature 560, 484–488 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu JD & Srivastava D Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes for cardiac regenerative medicine. Circ. J 79, 245–254 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gascón S, Masserdotti G, Russo GL & Götz M Direct neuronal reprogramming: achievements, hurdles, and new roads to success. Cell Stem Cell 21, 18–34 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W et al. Long-term persistence and development of induced pancreatic beta cells generated by lineage conversion of acinar cells. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 1223–1230 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorel F et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic α-cells to B-cells after extreme B-cell loss. Nature 464, 1149–1154 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Humeres C & Frangogiannis NG Fibroblasts in the infarcted, remodeling, and failing heart. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci 4, 449–467 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin Y et al. Three-dimensional brain-like microenvironments facilitate the direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into therapeutic neurons. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2, 522–539 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Y et al. Tissue-engineered 3-dimensional (3D) microenvironment enhances the direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes by microRNAs. Sci. Rep 6, 38815 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magnusson JP et al. A latent neurogenic program in astrocytes regulated by Notch signaling in the mouse. Science 346, 237–241 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu X et al. Region-restrict astrocytes exhibit heterogeneous susceptibility to neuronal reprogramming. Stem Cell Rep 12, 290–304 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buffo A et al. Origin and progeny of reactive gliosis: a source of multipotent cells in the injured brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3581–3586 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang SH, Fukaya M, Yang JK, Rothstein JD & Bergles DE NG2+ CNS glial progenitors remain committed to the oligodendrocyte lineage in postnatal life and following neurodegeneration. Neuron 68, 668–681 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De La Rossa A et al. In vivo reprogramming of circuit connectivity in postmitotic neocortical neurons. Nat. Neurosci 16, 193–200 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rouaux C & Arlotta P Direct lineage reprogramming of post-mitotic callosal neurons into corticofugal neurons in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol 15, 214–221 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao X et al. Endogenous reprogramming of alpha cells into beta cells, induced by viral gene therapy, reverses autoimmune diabetes. Cell Stem Cell 22, 78–90.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collombat P et al. The ectopic expression of Pax4 in the mouse pancreas converts progenitor cells into α and subsequently β cells. Cell 138, 449–462 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bramswig NC et al. Epigenomic plasticity enables human pancreatic α to β cell reprogramming. J. Clin. Invest 123, 1275–1284 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y et al. Ascl1 converts dorsal midbrain astrocytes into functional neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci 35, 9336–9355 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colasante G et al. Rapid conversion of fibroblasts into functional forebrain GABAergic interneurons by direct genetic reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 17, 719–734 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li W et al. In vivo reprogramming of pancreatic acinar cells to three islet endocrine subtypes. eLife 3, 1846 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nam YJ et al. Induction of diverse cardiac cell types by reprogramming fibroblasts with cardiac transcription factors. Development 141, 4267–4278 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyamoto K et al. Direct in vivo reprogramming with sendai virus vectors improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cell Stem Cell 22, 91–103.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee K et al. Peptide-enhanced mRNA transfection in cultured mouse cardiac fibroblasts and direct reprogramming towards cardiomyocyte-like cells. Int. J. Nanomed 10, 1841–1854 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chakraborty S et al. A CRISPR/Cas9-based system for reprogramming cell lineage specification. Stem Cell Rep 3, 940–947 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]