Abstract

Background

Rectal resection surgery is often followed by a loop ileostomy creation. Despite improvements in surgical technique and development of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, the readmission-rate after rectal resection is still estimated to be around 30%. The purpose of this study was to identify risk factors for readmission after rectal resection surgery. This study also investigated whether elderly patients (≥ 65 years old) dispose of a distinct patient profile and associated risk factors for readmission.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of prospectively collected data from patients who consecutively underwent rectal resection for cancer within an ERAS protocol between 2011 and 2016. The primary study endpoint was 90-day readmission. Patients with and without readmission within 90 days were compared. Additional subgroup analysis was performed in patients ≥ 65 years old.

Results

A total of 344 patients were included, and 25% (n = 85) were readmitted. Main reasons for readmission were acute renal insufficiency (24%), small bowel obstruction (20%), anastomotic leakage (15%) and high output stoma (11%). In multivariate logistic regression, elevated initial creatinine level (cut-off values: 0.67–1.17 mg/dl) (OR 1.95, p = 0.041) and neoadjuvant radiotherapy (OR 2.63, p = 0.031) were significantly associated with readmission. For ileostomy related problems, elevated initial creatinine level (OR 2.76, p = 0.021) was identified to be significant.

Conclusion

Recovery after rectal resection within an ERAS protocol is hampered by the presence of a loop ileostomy. ERAS protocols should include stoma education and high output stoma prevention.

Keywords: Rectal resection, Readmission, Ileostomy, Risk factors, ERAS

Background

A defunctioning ileostomy is often created to optimize postoperative outcome after restorative rectal resection and to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage [1, 2]. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols were developed and implemented to improve postoperative recovery [3]. ERAS guidelines consist of pre-, peri- and postoperative evidence-based treatment measures aiming to reduce the number of complications and shorten the length of hospital stay [3–6]. Those measures consist among other things of early postoperative refeeding and mobilization, thromboembolic prophylaxis, oral carbohydrates preoperatively, opium-free anesthesia and avoidance of usage of nasogastric tubes. Despite all these efforts, 30- to 60-day readmission rates after restorative rectal resection are still estimated to be around 30% [7, 8]. Overall long-term morbidity rate after rectal resection has been reported to be 20–30% (mean follow-up time: 36–85 months) [9, 10]. Although a combination of efforts has led to improved recovery and shorter length of hospital stay, it is hypothesized that patients with a defunctioning ileostomy have a higher risk of acute renal insufficiency and of readmission. The aim of this study was to identify risk factors for readmission in patients after rectal resection and loop ileostomy creation.

Methods

A retrospective database survey of prospectively collected data from patients who underwent rectal resection surgery within an ERAS-protocol over a 5-year period was conducted. In short, ERAS-protocol was implemented in 2009 and the following aspects were systematically used: preadmission counseling, no premedication, no nasogastric tube, multimodal perioperative analgesia, prevention of sodium and fluid overload, minimally-invasive approach with short incisions, prevention of hypothermia, thrombo-prophylaxis, routine postoperative mobilization, prevention of nausea and vomiting, early removal of catheters [11]. For rectal resections, all patients underwent mechanical bowel preparation as per hospital protocol. There was no systematic use of carbohydrate drinks (immune-nutritional therapy). Inclusion criteria were adult patients who underwent restorative proctectomy between 2011 and 2016. Exclusion criteria were patients who underwent rectal amputation with permanent colostomy, and urgent operations. Primary study endpoint was 90-day readmission. Two attending surgeons (ADH, AW) operated on these patients following the same principles. In general, ileostomies were performed in patients after neoadjuvant therapy, as per center protocol. Ileostomy-related problems were defined as all complications occurring because of the presence of an ileostomy. Complications such as parastomal skin problems, stoma necrosis (complete or partial), leakage caused by a low lying stoma, stenosis, soma bleeding, granuloma formation, prolapse, and parastomal hernia were recorded in the database. Loss of stoma output secondary to other causes was classified as ileostomy-related problem. High output stoma was defined as a stoma output exceeding 2000 ml/24 h. Acute renal insufficiency was defined as a decrease in renal function in the postoperative period, measured by an increase in serum creatinine or a decrease in urine output, or both. Anastomotic leakage was defined as a breach in a surgical join between two hollow viscera, with or without active leak of luminal contents. Readmission was defined as unanticipated need for hospitalization after rectal resection (index operation). Creatinine level was measured during hospital stay of the index operation. Initial creatinine level was the first value during hospital admission. Reference values were 0.51–0.95 mg/dl. Abnormal creatinine was defined as creatinine > 0.95 mg/dl. Additional subgroup analysis was performed in patients ≥ 65 years old. This study was ethically approved by The Research Ethics Committee UZ/KU Leuven (MP007786).

Statistical analysis

Mann–Whitney U and Fishers exact tests were used to compare continuous/ordinal and categorical variables, respectively, between patients with and without readmission within 90 days. The discriminative ability (C-index) was reported for each of the considered predictors of readmission (0.5 = random prediction, 1 = perfect discrimination). A multivariable logistic regression model was obtained applying a backward selection strategy with p = 0.157 as critical p-value to stay in the model. The use of this critical value corresponds to using the Aikake Information Criterion for model selection. With this criterion we require that the increase in model χ2 has to be larger than two times the degrees of freedom. As an alternative, a stepwise selection procedure was used, yielding the same result. The prediction model obtained after applying a model building approach is overoptimistic, in the sense that it overestimates the future performance in new subjects. An optimism-corrected estimate of the performance was obtained using a bootstrap resampling procedure [12]. A similar approach was used to evaluate relations with the presence of an ileostomy problem within 90 days post discharge. Of note: time until readmission was not predicted, but readmission within 90 days. All analyses have been performed using SAS software, version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 344 patients who underwent rectal resection within an ERAS-protocol were included, 163 of which were older than 65 years old. Patient characteristics and operative details are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Mean age was 64 ± 11 years, whereas mean age in the elderly population was 73 ± 6 years. Older patients and the overall population showed a remarkably similar patient profile. Overall, only one third of the patients were female (32.9%). The majority of patients could be categorized in American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) category II (67.7%) and were treated with neoadjuvant therapy (68%). Sixty-seven percent (n = 231) of the patients received a loop ileostomy. Mean postoperative length of stay was 12 ± 9 days (median 9 (IQR 7–14) days). Overall readmission rate was 25% (85 out of 344 patients). Comparable rates of readmission were found in patients < 65 and ≥ 65 years old: 25% (45 out of 181) and 25% (40 out of 163), respectively. In univariate analysis, there was a significant difference in rate of treatment with neoadjuvant radiotherapy in the patient population older than 65 years old between the readmitted and non-readmitted group (30% vs. 9.8% respectively, p = 0.005). No difference was found in readmission rates between patients who did and did not receive a loop ileostomy. There were no patients lost to follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and operative details

| Characteristic | Overall | No readmission | Readmission | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 344 | n = 259 | n = 85 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.8 ± 11.4 | 63.9 ± 11 | 63.3 ± 12.7 | 0.876 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 231 (67.2%) | 175 (67.6%) | 56 (65.9%) | 0.791 |

| Female | 113 (32.9%) | 84 (32.4%) | 29 (34.1%) | |

| Weight (mean ± SD) | 77.8 ± 16.4 | 77.7 ± 16.3 | 78.1 ± 16.7 | 0.499 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 26.5 ± 4.9 | 26.4 ± 4.9 | 26.6 ± 4.6 | 0.517 |

| ASA class | ||||

| I | 31 (9%) | 27 (10.4%) | 4 (4.7%) | 0.179 |

| II | 233 (67.7%) | 168 (64.9%) | 65 (76.4%) | |

| III | 79 (23%) | 63 (24.3%) | 16 (18.8%) | |

| IV | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Smoking behavior | ||||

| Never | 186 (54.2%) | 141 (54.7%) | 45 (52.9%) | 0.818 |

| Stopped smoking | 116 (33.8%) | 85 (33%) | 31 (36.5%) | |

| Actual smoker | 41 (12%) | 32 (12.4%) | 9 (10.6%) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 2.1 | 4.9 ± 2 | 0.785 |

| Initial creatinine | ||||

| Abnormal | 66 (19.2%) | 45 (17.4%) | 21 (24.7%) | 0.154 |

| Normal | 278 (80.8%) | 214 (82.6%) | 64 (75.3%) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||||

| No | 110 (32%) | 87 (33.6%) | 23 (27.1%) | 0.061 |

| Chemotherapy | 10 (2.9%) | 7 (2.7%) | 3 (3.5%) | |

| Radiotherapy | 32 (9.3%) | 18 (7%) | 14 (16.5%) | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 192 (55.8%) | 147 (56.8%) | 45 (52.9%) | |

| Mode of surgery | ||||

| Open | 66 (19.2%) | 50 (19.3%) | 16 (18.8%) | 0.615 |

| Open converted | 28 (8.1%) | 19 (7.3%) | 9 (10.6%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 250 (72.7%) | 190 (73.4%) | 60 (70.6%) | |

| Additional surgery | ||||

| No | 318 (92.4%) | 241 (93.1%) | 77 (90.6%) | 0.480 |

| Yes | 26 (7.6%) | 18 (7%) | 8 (9.4%) | |

| Ileostoma | ||||

| No | 113 (32.9%) | 83 (32.1%) | 30 (35.3%) | 0.697 |

| Already present | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Newly placed | 230 (66.9%) | 175 (67.6%) | 55 (64.7%) | |

| Duration surgery (h) (mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 1 | 0.844 |

| Blood loss (dl) (mean ± SD) | 2.7 ± 3.4 | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 3.4 | 0.503 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | 12.1 ± 9.3 | 12 ± 9.9 | 12.3 ± 7.1 | 0.104 |

| Creatinine at discharge (mean ± SD) | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.808 |

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and operative details in patients > 65 years old

| Characteristic | Age > 65 years | No readmission | Readmission | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 163 | n = 123 | n = 40 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 73.1 ± 6.1 | 72.8 ± 6.2 | 74.1 ± 5.7 | 0.186 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 119 (73%) | 90 (73.2%) | 29 (72.5%) | 1.000 |

| Female | 44 (27%) | 33 (26.8%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Weight (mean ± SD) | 78.2 ± 15 | 78 ± 14.8 | 79 ± 15.8 | 0.399 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 27.2 ± 4.7 | 27.1 ± 4.7 | 27.8 ± 4.6 | 0.188 |

| ASA class | ||||

| I | 6 (3.7%) | 6 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.497 |

| II | 103 (63.2%) | 76 (61.8%) | 27 (67.5%) | |

| III | 54 (33.1%) | 41 (33.3%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| IV | ||||

| Smoking behavior | ||||

| Never | 83 (50.9%) | 64 (52%) | 19 (47.5%) | 0.772 |

| Stopped smoking | 69 (42.3%) | 50 (40.7%) | 19 (47.5%) | |

| Actual smoker | 11 (6.8%) | 9 (7.3%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 6 ± 1.5 | 0.173 |

| Initial creatinine | ||||

| Abnormal | 39 (23.9%) | 26 (21.1%) | 13 (32.5%) | 0.199 |

| Normal | 124 (76.1%) | 97 (78.9%) | 27 (67.5%) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | ||||

| No | 60 (36.8%) | 49 (39.8%) | 11 (27.5%) | 0.005 |

| Chemotherapy | 3 (1.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Radiotherapy | 24 (14.7%) | 12 (9.8%) | 12 (30%) | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 76 (46.6%) | 61 (49.6%) | 15 (37.5%) | |

| Mode of surgery | ||||

| Open | 31 (19%) | 25 (20.3%) | 6 (15%) | 0.676 |

| Open converted | 13 (8%) | 9 (7.3%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 119 (73%) | 89 (72.4%) | 30 (75%) | |

| Additional surgery | ||||

| No | 153 (93.9%) | 115 (93.5%) | 38 (95%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 10 (6.1%) | 8 (6.5%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Ileostoma | ||||

| No | 39 (23.9%) | 30 (24.4%) | 9 (22.5%) | 1.000 |

| Already present | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.81%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Newly placed | 123 (75.5%) | 92 (74.8%) | 31 (77.5%) | |

| Duration surgery (h) (mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 0.820 |

| Blood loss (dl) (mean ± SD) | 2.6 ± 3 | 2.6 ± 3.2 | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 0.966 |

| Length of stay (mean ± SD) | 12.5 ± 8.3 | 12 ± 8.1 | 14.2 ± 8.9 | 0.142 |

| Creatinine at discharge (mean ± SD) | 1 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.3 | 0.589 |

Prediction of readmission

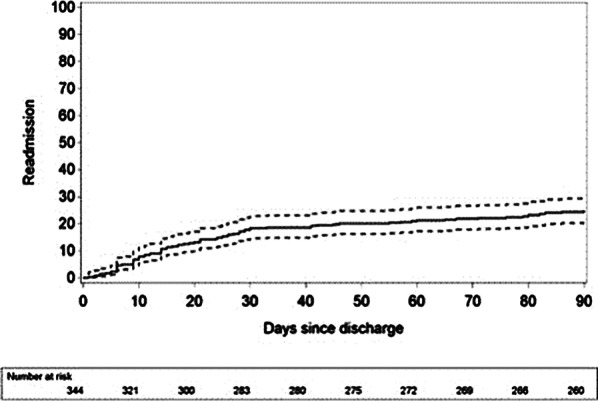

Figure 1 shows that 18.3% (14.9–22.4%, 95% CI) of patients were readmitted within 30 days after discharge, 21.2% (17.7–25.4%, 95% CI) within 60 days after discharge and 24.7% (21.0–28.9%, 95% CI) within 90 days after discharge. Furthermore, mean duration of readmission was 9 ± 9 days.

Fig. 1.

Readmission rate

Main reasons for readmission, together encompassing 70% of the cases were: acute renal insufficiency (24%), small bowel obstruction (20%), anastomotic leakage (15%) and high output stoma (11%) (Tables 3 and 4). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine which factors were associated with readmission. Abnormal initial creatinine and neoadjuvant radiotherapy were identified as significantly associated with readmission in the overall population (resp. OR = 1.95, p = 0.041 and OR = 2.63, p = 0.031) (Table 5).

Table 3.

Reasons for readmission

| Variable | Overall | No readmission | Readmission | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 344 | n = 259 | n = 85 | ||

| Any complication | ||||

| No | 225 (65.4%) | 173 (66.8%) | 52 (61.2%) | 0.360 |

| Yes | 119 (34.6%) | 86 (33.2%) | 33 (38.8%) | |

| Number of complications | ||||

| 0 | 225 (65.4%) | 173 (66.8%) | 52 (61.2%) | 0.221 |

| 1 | 81 (23.6%) | 54 (20.9%) | 27 (31.8%) | |

| 2 | 26 (7.6%) | 22 (8.5%) | 4 (4.7%) | |

| 3 | 5 (1.5%) | 5 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 6 (1.7%) | 4 (1.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| 5 | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Anastomotic leakage | ||||

| No | 320 (93%) | 241 (93%) | 79 (92.9%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 24 (7%) | 18 (7%) | 6 (7.1%) | |

| Postoperative bleeding | ||||

| No | 340 (98.8%) | 255 (98.5%) | 85 (100%) | 0.576 |

| Yes | 4 (1.2%) | 4 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Postoperative ileus | ||||

| No | 302 (87.8%) | 226 (87.3%) | 76 (89.4%) | 0.704 |

| Yes | 42 (12.2%) | 33 (12.7%) | 9 (10.6%) | |

| SSI type 1 wound infection | ||||

| No | 338 (98.3%) | 256 (98.8%) | 82 (96.5%) | 0.163 |

| Yes | 6 (1.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | 3 (3.5%) | |

| Urinary retention | ||||

| No | 321 (93.3%) | 240 (92.7%) | 81 (95.3%) | 0.466 |

| Yes | 23 (6.7%) | 19 (7.3%) | 4 (4.7%) | |

| UTI, urological infection | ||||

| No | 330 (95.9%) | 249 (96.1%) | 81 (95.3%) | 0.754 |

| Yes | 14 (4.1%) | 10 (3.9%) | 4 (4.7%) | |

| Cardiac complication | ||||

| No | 338 (98.3%) | 256 (98.8%) | 82 (96.5%) | 0.163 |

| Yes | 6 (1.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | 3 (3.5%) | |

| Lung complication | ||||

| No | 334 (97.1%) | 251 (96.9%) | 83 (97.7%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 10 (2.9%) | 8 (3.1%) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Renal complication | ||||

| No | 333 (96.8%) | 250 (96.5%) | 83 (97.7%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 11 (3.2%) | 9 (3.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Catheter acquired infection | ||||

| No | 328 (95.4%) | 246 (95%) | 82 (96.5%) | 0.769 |

| Yes | 16 (4.7%) | 13 (5%) | 3 (3.5%) | |

| High output stoma | ||||

| No | 325 (94.5%) | 247 (95.4%) | 78 (91.8%) | 0.271 |

| Yes | 19 (5.5%) | 12 (4.6%) | 7 (8.2%) | |

| Small bowel obstruction | ||||

| No | 341 (99.1%) | 256 (98.8%) | 85 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 3 (0.9%) | 3 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ileostomy problem | ||||

| No | 314 (91.3%) | 238 (91.9%) | 76 (89.4%) | 0.508 |

| Yes | 30 (8.7%) | 21 (8.1%) | 9 (10.6%) | |

Table 4.

Reasons for readmission in patients > 65 years old

| Variable | Age > 65 years | No readmission | Readmission | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 163 | n = 123 | n = 40 | ||

| Any complication | ||||

| No | 101 (62.0%) | 79 (64.2%) | 22 (55%) | 0.350 |

| Yes | 62 (38%) | 44 (35.8%) | 18 (45%) | |

| Number of complications | ||||

| 0 | 101 (62%) | 79 (64.2%) | 22 (55%) | 0.329 |

| 1 | 41 (25.2%) | 27 (22%) | 14 (35%) | |

| 2 | 14 (8.6%) | 12 (9.8%) | 2 (5%) | |

| 3 | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 4 | 5 (3.1%) | 3 (2.4%) | 2 (5%) | |

| 5 | ||||

| Anastomotic leakage | ||||

| No | 157 (96.3%) | 118 (95.9%) | 39 (97.5%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 6 (3.7%) | 5 (4.1%) | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Postoperative bleeding | ||||

| No | 161 (98.8%) | 121 (98.4%) | 40 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Postoperative ileus | ||||

| No | 141 (86.5%) | 105 (85.4%) | 36 (90%) | 0.598 |

| Yes | 22 (13.5%) | 18 (14.6%) | 4 (10%) | |

| SSI type 1 wound infection | ||||

| No | 159 (97.6%) | 121 (98.4%) | 38 (95%) | 0.253 |

| Yes | 4 (2.5%) | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Urinary retention | ||||

| No | 147 (90.2%) | 110 (89.4%) | 37 (92.5%) | 0.763 |

| Yes | 16 (9.8%) | 13 (10.6%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| UTI, urological infection | ||||

| No | 157 (96.3%) | 119 (96.8%) | 38 (95%) | 0.636 |

| Yes | 6 (3.7%) | 4 (3.3%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Cardiac complication | ||||

| No | 158 (96.9%) | 121 (98.4%) | 37 (92.5%) | 0.095 |

| Yes | 5 (3.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Lung complication | ||||

| No | 156 (95.7%) | 118 (95.9%) | 38 (95%) | 0.681 |

| Yes | 7 (4.3%) | 5 (4.1%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Renal complication | ||||

| No | 155 (95.1%) | 117 (95.1%) | 38 (95%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 8 (4.9%) | 6 (4.9%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Catheter acquired infection | ||||

| No | 155 (95.1%) | 117 (95.1%) | 38 (95%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 8 (4.9%) | 6 (4.9%) | 2 (5%) | |

| High output stoma | ||||

| No | 152 (93.3%) | 117 (95.1%) | 35 (87.5%) | 0.140 |

| Yes | 11 (6.8%) | 6 (4.9%) | 5 (12.5%) | |

| Small bowel obstruction | ||||

| No | 163 (100%) | 123 (100%) | 40 (100%) | |

| Yes | ||||

| Ileostomy problem | ||||

| No | 144 (88.3%) | 111 (90.2%) | 33 (82.5%) | 0.254 |

| Yes | 19 (11.7%) | 12 (9.8%) | 7 (17.5%) | |

Table 5.

Multivariate prediction of 90-day readmission: stepwise multivariate logistic regression model

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| ASA | ||

| ASA 2 | 0.049 | |

| ASA 3–4 | 3.8 (1.1–13.1) | 0.036 |

| 2.3 (0.6–8.6) | 0.228 | |

| Initial creatinine | ||

| Abnormal | 2 (1.0–3.7) | 0.041 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 0.134 | |

| Chemotherapy | 1.8 (0.4–7.5) | 0.443 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.831 |

| Radiotherapy | 2.6 (1.1–6.3) | 0.031 |

Prediction of ileostomy problems

Patients who suffered from an ileostomy-related problem were older than patients who did not: mean age 68 ± 11 years versus 63 ± 11 years, respectively (p = 0.025). Abnormal initial creatinine value (OR = 2.76, p = 0.021) was determined as risk factor for development of ileostomy problems (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate prediction of 90-day ileostomy problem: stepwise multivariate logistic regression model

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial creatinine | ||

| Abnormal | 2.8 (1.7–6.5) | 0.021 |

| Mode of surgery | 0.1475 | |

| Laparoscopic | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.052 |

| Open converted | 0.6 (0.1–2.5) | 0.454 |

| Ileostomy problem | ||

| Yes | 2.6 (0.9–7.6) | 0.088 |

Discussion

This study shows that the readmission rate after rectal resection was 25%, and most readmissions occurred within 30 days after discharge. These findings are in line with the literature (Table 7) [6–8, 13–22]. Abnormal initial creatinine and neoadjuvant therapy were identified as significantly associated with readmission. Moreover, most patients were readmitted because of acute renal insufficiency secondary to ileostomy-related problems. In a similar study, unplanned hospital readmission following ileostomy was 29%. Also, renal impairment at discharge was the most important risk factor to predict readmission [23]. In another recent study, Fielding et al. found that postoperative renal impairment more frequently occurred in patients with a diverting ileostomy. Moreover, ileostomy formation was independently associated with kidney injury, and continued to have an impact, even after stoma closure [24]. Another study from the NSQIP dataset by Kim et al. showed that patients with postoperative renal impairment were much more likely to be readmitted after ileostomy creation [25]. O’Connell et al. identified surgical site infection (SSI) and stoma formation as significant risk factors for readmission in a study with a comparative sample size [26]. This can be attributed to the fact that firstly, SSI rate was much lower in our population (1.7% versus almost 10%) and secondly, the conclusion concerning stoma formation in the study by O’Connell et al. was based on seven cases (4/31 in the readmission group, 3/215 in the no-readmission group) [26]. We also observed an increased readmission risk after stoma formation (7/85 in the readmission group, 12/259 in the no-readmission group), although this was not statistically significant. It has already been shown that patients who received a stoma after colorectal resection are more likely to be readmitted to the hospital [7, 27, 28]. Many factors associated with readmission like age and past medical history are not prone to modification. In those high-risk cases, reduction of readmission should be attempted through adequate patient selection and preoperative optimization. The implementation of ERAS guidelines may play a major role in that matter. However, our study shows that despite the implementation of ERAS measures, the risk of readmission remains high in the patient population treated with a loop ileostomy. Therefore, efforts should be made to further reduce this risk. Shaffer et al. observed a 58% reduction of readmission rates and a more than 80% reduction in readmission-related costs after implementation of a specific patient follow-up program [29]. A similar program set up by Nagle et al. also resulted in a significant decrease of readmissions (15.5% to 0%) [30]. Shah et al. and Hardiman et al. obtained similar results using an enhanced recovery protocol and a patient self-care checklist, respectively [14, 17]. Iqbal et al. even found that a lack of a social worker involvement in planning for discharge is associated with the highest risk of readmission of all factors analyzed in their series (OR 5.15) [20]. These data suggest that patient guidance and monitoring could be of utmost importance in the attempt to reduce readmission rates and associated costs in ileostomy patients. The fact that in the present study, readmission rate was equal in both age categories is in line with what was reported by Kandagatla et al. [31]. It could be explained that nowadays overall health status, rather than age, influences the postoperative course the most. We also observed that readmission rate did not depend on surgical approach, meaning that presence of an ileostomy was a more important factor. The strengths of our study include a homogenous patient population, consisting of all rectal resection patients and our strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our study is unique as it only involves patients who underwent rectal resection and follow-up time is much longer than usual (90-day readmission).

Table 7.

Overview of the literature

| Sample size | Readmission rate (%) | Reason readmission | Risk factors | Protective factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. 2017 [13] | 1267 | 12.9 |

Infections (3.4%) Small bowel obstruction/ileus (3.3%) Dehydration (38.3%) |

Cardiovascular factors (OR 2.0) Renal comorbidity (OR 2.9) Preoperative chemo/radiotherapy (OR 4.0) Laparoscopic approach (OR 1.7) Longer operative time (OR 1.2) Due to dehydration: Chemo/radiotherapy (OR 4.7) Laparoscopic approach (OR 2.6) |

Cancer diagnosis (OR 0.2) |

| Fish et al. 2017 [7] | 407 | 28 |

Dehydration (42%) Intraperitoneal infections (33%) Extraperitoneal infections (29%) |

Clavien-Dindo complication grade 3 to 4 (OR 6.7) Charlson comorbidity index (OR 1.4 per point) Loop stoma (OR 2.2) |

Longer length of stay (OR 0.5) Age 65 years or older (OR 0.4) |

| Shah et al. 2017 [14] | 707 | 12 | Ileostomy | Enhanced recovery protocol | |

| Wood et al. 2017 | 2876 | 8.2 |

Ileus and nausea/vomiting (26.1%) Intra-abdominal ascess (23.9%) SSI (11.5%) |

Rectal surgery (OR 1.89) Stoma formation (OR 1.34) Reoperation during first admission (OR 4.60) |

|

| Justiniano et al. 2018 [8] | 262 | 30 | Dehydration (37%) | ||

| Hayden et al. 2012 | 154 | 20.1 |

Use of anti-diarrheals Neoadjuvant therapy |

||

| Messaris et al. 2012 [16] | 603 | 16.9 | Dehydration (43.1%) |

Laparoscopic approach Lack of epidural aneshtesia Preoperative use of sterois Postoperative use of diuretics |

|

| Hardiman et al. 2016 [17] | 430 | 26 | |||

| Charak et al. 2018 [18] | 99 | 36 |

Dehydration (39%) Infection (33%) Obstruction (3%) |

||

| Grahn et al. 2018 | 100 | 19.6–20.4 |

Dehydration (5.9–8.2%) Acute renal failure events (3.9–10.2%) |

Weekend discharges to home (OR 4.5) | |

| Iqbal et al. 2018 [20] | 86 | 26 |

Preoperative steroid use History of diabetes History of depression Lack of hospital social worker or postoperative ostomy education Presence of complications after the index procedure |

||

| Paquette et al. 2013 [21] | 201 | 17 |

Age greater than 50 IPAA |

||

| Chen et al. 2018 [22] | 8064 | 20.1 |

ASA class III Female sex IPAA Age > 65 Shortened length of stay ASA class I to II with IBD Hypertension |

The retrospective nature of our study is a potential limitation, as well as the fact that it is a single center study which yielded a limited number of patients. For patients treated within an ERAS protocol, length of hospital stay was rather long. This might be due to the fact that patient’s preference regarding discharge plays a role. Unfortunately, data regarding fit for discharge and actual discharge were not available, and could be considered a drawback. Furthermore, patients who were readmitted in outside hospitals were not taken into account and manual analysis of patient files and the use of a coding system was subject to human error. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of information on frailty in older patients and the fact that perioperative fluid balance was not exactly known. Prevention and patient education are key features to avoid readmission secondary to dehydration and ileostomy-related problems. Currently, a patient-centered protocol and follow-up to detect complications at an early stage via teleconsulting by a specialist nurse are under investigation at our department [32].

Conclusion

Readmission after rectal resection in the ERAS-era occurs in 25% of the cases. Most readmissions occur within 30 days after index hospitalization and acute renal insufficiency is frequently associated with readmission. Future patient-education initiatives should be used in conjunction with ERAS guidelines to reduce postoperative readmission.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Isabelle Terrasson and Mrs. Lynn Debrun for their help maintaining the database and following-up the patients.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- ERAS

Enhanced recovery after surgery

- SSI

Surgical site infection

- OR

Odds ratio

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in study design. JVB and AW analyzed and interpreted the patient data. Feedback on interpretation was given by GB and ADH. JVB was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors agreed to be personally accountable for the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was ethically approved by The Research Ethics Committee UZ/KU Leuven (MP007786).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mathiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:207–214. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisarska M, Gajewska N, Malczak P, Wysocki M, Witowski J, Torbicz G, Major P, Mizera M, Dembinski M, Migaczewski M, Budzynski A, Pedziwiatr M. Defunctioning ileostomy reduces leakage rate in rectal cancer surgery—systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9:20816–20825. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsmo HM, Pfeffer F, Rasdal A, Sintonen H, Körner H, Erichsen C. Pre- and postoperative stoma education and guidance within an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme reduces length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery. Int J Surg. 2016;36:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennedsen ALB, Eriksen JR, Gögenur I. Prolonged hospital stay and readmission rate in an enhanced recovery after surgery cohort undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:1097–1108. doi: 10.1111/codi.14446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292–298. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood T, Aarts MA, Okrainee A, Pearsall E, Victor JC, McKenzie M, Rotstein O, McLeod RS. Emergency room visits and readmissions following implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (iERAS) program. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;22:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish DR, Mancuso CA, Garcia-Aguilar JE, Lee SW, Nash GM, Sonoda T, Charlson ME, Temple LK. Readmission after ileostomy creation—retrospective review of a common and significant event. Ann Surg. 2017;265:379–387. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Justiniano CF, Temple LK, Swanger AA, Xu Z, Speranza JR, Cellini C, Salloum RM, Fleming FJ. Readmissions with dehydration after ileostomy creation: rethinking risk factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1297–1305. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, Smith M, Rubino F, Mutter D, Marescaux J. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contul RB, Grivon M, Fabozzi M, Millo P, Nardi MJ, Aimonetto S, Parini U, Allieta R. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for extraperitoneal rectal cancer: long-term results of a 18-year single-center experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:796–807. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fierens J, Wolthuis AM, Penninckx F, D'Hoore A. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol: prospective study of outcome in colorectal surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:355–358. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2012.11680851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steyerberg E. Clinical prediction models—a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. Berlin: Springer Science + Business Media LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Stocchi L, Cherla D, Liu G, Agostinelli A, Delaney CP, Steele SR, Gorgun E. Factors associated with hospital readmission following diverting ileostomy creation. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1667-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah PM, Johnston L, Sarosiek B, Harrigan A, Friel CM, Thiele RH, Hedrick TL. Reducing readmissions while shortening length of stay: the positive impact of an enhanced recovery protocol in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:219–227. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayden DM, Pinzon MCM, Francescatti AB, Edquist SC, Malczewski MR, Jolley JM, Brand MI, Saclarides TJ. Hospital readmission for fluid and electrolyte abnormalities following ileostomy construction: preventable of unpredictable? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:298–303. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messaris E, Sehgal R, Deiling S, Koltun WA, Stewart D, McKenna K, Poritz LS. dehydration is the most common indicator for readmission after diverting ileostomy creation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:175–180. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823d0ec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE, Arbor A. Patient autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery. 2016;160:1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charak G, Kuritzkes BA, Al-Mazrou A, Suradkar K, Valizadeh N, Lee-Kong SA, Feingold DL, Pappou EP. Use of an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker is a major risk factor for dehydration requiring readmission in the setting of a new ileostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:311–316. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2961-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grahn SW, Lowry AC, Osborne MC, Melton GB, Gaertner WB, Vogler SA, Madoff RD, Kwaan MR. System-wide improvement for transitions after ileostomy surgery: can intensive monitoring of protocol compliance decrease readmissions? A randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:363–370. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iqbal A, Sakharuk I, Goldstein L, Tan SA, Qiu P, Li Z, Hughes SJ. Readmission after elective ileostomy in colorectal surgery is predictable. JSLS. 2018;22:1–8. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2018.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paquette IM, Solan P, Rafferty JF, Ferguson MA, Davis BR. Readmission for dehydration or renal failure after ileostomy creation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:974–979. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828d02ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SY, Stem M, Cerullo M, Canner JK, Gearhart SL, Bashar S, Fang S, Efron J. Predicting the risk of readmission from dehydration after ileostomy formation: the dehydration readmission after ileostomy prediction score. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1410–1417. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Bhat S, O'Grady G, Bissett I. Re-admissions after ileostomy formation: a retrospective analysis from a New Zealand tertiary centre. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:1621–1626. doi: 10.1111/ans.16076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fielding A, Woods R, Moosvi SR, Wharton RQ, Speakman CTM, Kapur S, Shaikh I, Hernon JM, Lines SW, Stearns AT. Renal impairment after ileostomy formation: a frequent event with long-term consequences. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22:269–278. doi: 10.1111/codi.14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim NE, Hall JF. Risk factors for readmission after ileostomy creation: an NSQIP database study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;23:1010. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04549-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Connell EP, Healy V, Fitzpatrick F, Higgins CA, Burke JP, McNamara DA. Predictors of readmission following proctectomy for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62:6. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bliss LA, Maguire LH, Chau Z, Yang CJ, Nagle DA, Chan AT, Tseng JF. Readmission after resections of the colon and rectum: predictors of a costly and common outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:1164–1173. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulaylat AN, Dillon PW, Hollenbeak CS, Stewart DB. Determinants of 30-d readmission after colectomy. J Surg Res. 2015;193:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaffer VO, Owi T, Kumarusamy MA, Sullivan PS, Srinivasan JK, Maithel SK, Staley CA, Sweeney JF, Esper G. Decreasing readmission in ileostomy patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagle D, Pare T, Keenan E, Marcet K, Tizio S, Poylin V. Ileostomy pathway virtually eliminates readmissions for dehydration in new ostomates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:12. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827080c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kandagatla P, Nikolian VC, Matusko N, Mason S, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM. Patient-reported outcomes and readmission after ileostomy creation in older adults. Am Surg. 2018;84:1814–1818. doi: 10.1177/000313481808401141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonella F, Valenti A, Massucco P, Russolillo N, Mineccia M, Fontana AP, Cucco D, Ferrero A. A novel patient-centered protocol to reduce hospital readmissions for dehydration after ileostomy. Updates Surg. 2019;71:515–521. doi: 10.1007/s13304-019-00643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.