Abstract

Social pharmacology is a branch of clinical pharmacology, which depicts relationships between society and drugs and in particular factors, reasons, social consequences of drug use as well as representations of drugs in the society. Recent development and marketing of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines raises a number of questions of social pharmacology: are vaccines drugs like any other? What is their perception at the individual, population and societal levels? How do individuals perceive the risks and benefits of these vaccines? What is the perception at the societal level? What is the individual and societal acceptability of these vaccines during a pandemic? All these questions are discussed in the light of recent data. A number of proposals, both at the individual and at the collective or population level, are formulated to help solve these problems of social pharmacology.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccines, Tozinameran, Comirnaty®, Moderna vaccine, AstraZeneca vaccine, Vaxzevria®, Social pharmacology

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Introduction

Several vaccines are being developed as part of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first vaccines to be marketed were the Pfizer tozinameran Comirnaty® [1] and Moderna [2] messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, followed by the adenovirus vaccines from AstraZeneca Vaxzevria® [3] and Janssen (Johnson and Johnson) [4]. Today, Russian vaccine, another adenovirus vaccine, is not marketed in Europe or United States [5]. Other reviews in this special issue have discussed the data from clinical trials [6] as well as pharmacovigilance [7] and pharmacoepidemiological [8] studies. However, besides basic or clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, development of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines has raised a lot of questions in the field of what is now known as social (or societal) pharmacology: acceptability by society and individuals, perception of benefits, interpretation of risks, representation of the various vaccines according to their composition, variations according to one's position in society (patient, doctor, health professional, politician…), presentations in the media…

After a brief review of purposes and objectives of social pharmacology, this review will discuss some of the major issues in social pharmacology as applied to COVID-19 vaccines, without seeking to be exhaustive.

What is social pharmacology?

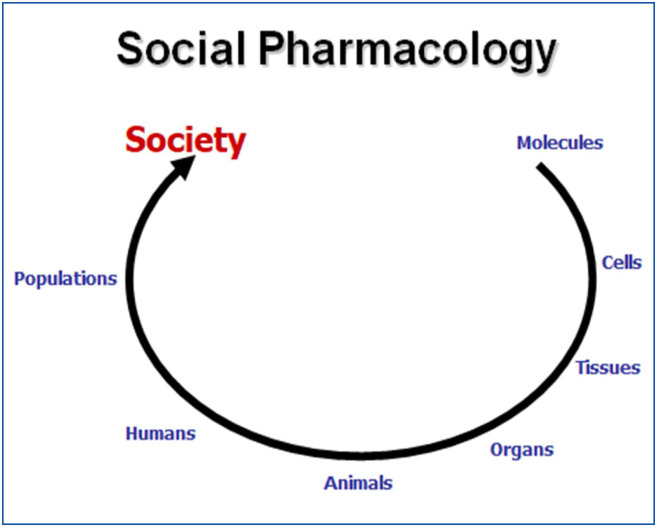

A short reflection on pharmacology, as a scientific and medical discipline, clearly shows its evolution from a pure biological and fundamental science (molecular pharmacology, cellular pharmacology, experimental pharmacology) to a clinical (clinical pharmacology) and an epidemiological discipline (pharmacovigilance, pharmacoepidemiology) and now to a social science: social pharmacology (Fig. 1 ).

Figure 1.

Different topics in pharmacology. social pharmacology is the ultimate evolution of pharmacological sciences.

Social pharmacology is the study of interactions between drugs and society. Like pharmacology with its two branches, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, social pharmacology has two aspects: the first is “social pharmacokinetics”, i.e. investigation of drug “metabolism” by society, and the second “social pharmacodynamics”, which studies changes in human behaviour in society as a result of drug use (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 2.

Pharmacology and social pharmacology with their two subdivisions: pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics.

Social pharmacology studies can be summarized into five main themes [9], [10]:

-

•

factors influencing drug use (others than clinical or rational factors);

-

•

motives for prescribing, dispensing, using or self-medicating drugs (others than clinical or rational factors);

-

•

factors involved in regulatory authorisations (others than clinical or rational factors);

-

•

social implications of drug exposure;

-

•

interactions between drugs, environment and society.

Finally, as said by Gilles Bardelay, the founder of “La Revue Prescrire”, social pharmacology can be defined as a view on “Drugs, differently”.

All actors of the private (before marketing authorisation) or public (after marketing authorisation) drug life do participate to social pharmacology: academic and industrial researchers, pharmaceutical industry, health agencies, control and authorisation systems, health professionals, university members, lawyers, patients of course and finally the media, journalists and consumer press [9], [10].

All these data on social pharmacology are highly relevant to COVID-19 vaccines. This review aimed to discuss all aspect of social pharmacology in the field of COVID-19 vaccines.

Vaccines are drugs with their own benefits and risks!

First of all, vaccines correspond to the definition of drugs “by function”, i.e. products with preventive properties and/or modifying body's organic functions. Thus, vaccines have been studied and developed in the same way as all other drugs, including phase I, II, III clinical pharmacology trials.

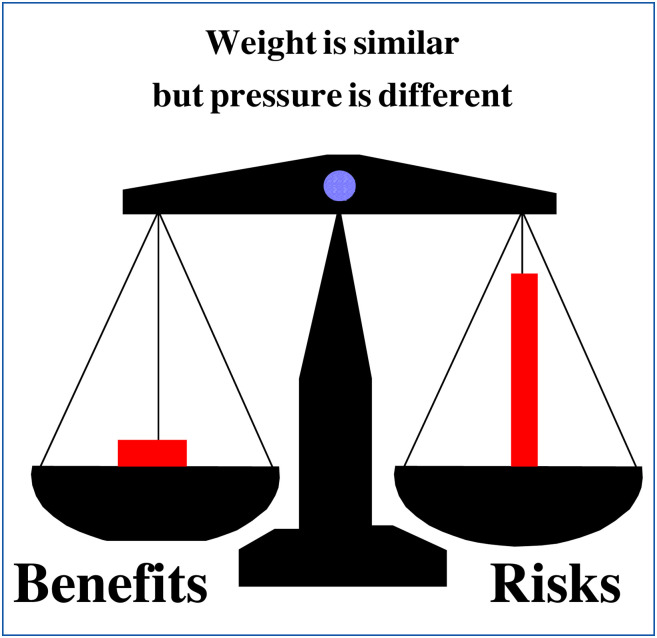

In this respect, the very rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines (within a few months) for a new and previously totally unknown disease should be congratulated. This scientific and technological achievement should be underlined and classified in the “benefits” column for patients and society. However, daily observations and analyses of social pharmacology show that this benefit part is still badly perceived, minimised or even forgotten by patients and society. This is because the societal pressure of risk(s) is greater than the weight of benefit(s) alone. Fig. 3 illustrates this imbalance in relation to drugs in general. This Fig. 3 must be considered with even more acuity and reality for vaccines compared to other drugs.

Figure 3.

Representation of benefits/risks balance of drugs in social pharmacology.

However, vaccines are special products within drugs. On the one hand, they are administered to healthy subjects (often infants or children) to prevent a hypothetical disease. This disease is generally unknown or forgotten by the general public (tetanus, diphtheria, poliomyelitis…) which leads to a partial, biased and often false vision of the problem by non-health professionals (and sometimes even by some health professionals themselves). On the other hand, benefits of vaccination are not only individual (for vaccinated populations) but also population-based (for unvaccinated subjects). People often poorly understand societal importance of this herd immunity. However, many dispute this notion of collective benefit and herd immunity, pointing out that reasoning in terms of benefits-risks balance only makes sense collectively, since the patient who will suffer from adverse drug reactions will not be “saved” by the vaccine. Accordingly, vaccine hesitancy rose in France since 2000, with a marketed increase after the pandemic H1N1 flu vaccination campaign in 2009-2017 [11].

Unfortunately, subjects do not consider vaccines as drugs in their own right. Several examples can be cited. First, people consider that, in case of illness, they may or may not take the drug. In the case of vaccines with their more or less generalized vaccination campaigns, they often feel that they have no choice. Second, as vaccines are given to people who are not ill, they cannot imagine that vaccines can cause adverse drug reactions, like any other drug. This consideration explains the acceptance or even the refusal of the slightest adverse drug reaction and risks of vaccines by a disease-free population (healthy population), which cannot accept “becoming ill” after administering a vaccine. The third point is that vaccines are administered not for curative but for preventive purposes, here for COVID-19, a disease that would not necessarily be serious for all subjects. Finally, accepting adverse drug reactions for a purely preventive substance remains very difficult for the vast majority of people, even if the vaccine is presented to them as an effective drug. The problem of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants and their social perception will deliberately not be discussed in this text.

For COVID-19 vaccines, risk of venous thrombosis, described in particular with the AstraZeneca vaccine, should be discussed taking into account the frequent occurrence of thrombotic episodes in COVID-19 disease. This aspect remains largely unknown to the public, who cannot imagine variations in the acceptability of a vaccine according to the characteristics of the disease to be prevented. Can we remind you that we are talking about preventing a disease that is currently difficult to cure or even largely incurable and that is responsible for the death of the equivalent of a jumbo jet every day (300-400 deaths per day) in France and almost 3 million deaths worldwide between January 2020 and March 2021? Proportionate risk(s) of drugs to risk(s) of the treated disease is a major goal for vaccines’ acceptability.

Clearly, much remains to be done to improve the individual and societal acceptability of vaccines [12].

Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines

Pharmacovigilance data concerning adverse drug reactions of COVID-19 vaccines are discussed elsewhere in this issue [7]. Evidence of serious venous thrombosis in atypical locations (cerebral, splanchnic, etc.) has given rise to a great deal of mistrust and defiance on the part of the public with regard to the Vaxzevria® AstraZeneca vaccine. Thus, people are currently very worried and suspicious about Astra Zeneca vaccination. They want to be vaccinated, but they refuse the AstraZeneca vaccine and prefer messenger RNA vaccines. This change in behaviour is interesting and surprising since at the beginning of 2021, people clearly expressed their distrusts, reserves and concerns about the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines because of their new mechanisms of action. Indeed, prior to the French COVID vaccination campaign, a quarter of French people considered not getting vaccinated against COVID-19, considering that these new mRNA vaccines were not safe [13]. After having been worried about vaccines with a new and therefore at least partly poorly clinically validated mechanism of action, people have completely changed their minds, rejecting all or part of the AstraZeneca vaccine in favour of mRNA vaccines. A fine example of social pharmacology!

This race between distrust and trust has led political and medical leaders to step out of their proper roles: governments have entered the field of drugs and decision-making about risks or benefits of vaccines, while physicians have entered the field of regulatory policy to control distribution and use of these vaccines. This is an example of what has been discussed above: social pharmacodynamics, or how drug modify behaviour of groups in society. It is also noteworthy to consider that vaccine hesitancy is politically polarized in France, with the highest hesitancy among people lose to far right and far left parties [13], while in the Anglo-Saxon world, hesitancy is mostly associated with conservative ideology or republican partisan identity.

The pharmacovigilance monitoring carried out by the French regional pharmacovigilance centres and the French Drug Agency (ANSM) as well as in all other countries of the world by national pharmacovigilance networks with their national drug agencies results in regular (weekly) publications about vaccines safety on the drug agency's websites. This strategy is of course welcome and mandatory. Nevertheless, in terms of social pharmacology, one may wonder about interpretation and understanding of these data by people. There is obviously no question of questioning this laudable and desirable transparency, but one might ask whether it could not occasionally give rise to false interpretations of vaccine safety: for example, people (and sometimes unfortunately even doctors and health professionals) do not always know differences between events and adverse drug reactions or between occurrence and causality (or association). To some extent, could this high level of transparency not be detrimental to the acceptability of these vaccines?

In fact, people and unfortunately also the vast majority of health professionals do not know how to distinguish between harms (adverse drug reactions) and risks. Risk is a probability and harms a source of damage, in this case adverse effects. Obviously, health professionals have great difficulty in quantifying the individual risk for a specific patient. This often leads them to refuse the drug (here the vaccine) altogether, stop prescribing it at all and turn to another alternative. This is the distinction between individual danger and collective risk, which is impossible to solve by the treating physician in front of his individual patient.

Availability of COVID-19 vaccines

The issue of vaccine availability is discussed daily and widely in the media. The problem of relative shortage of vaccines, at least at beginning of the vaccination campaign (first quarter of 2021), regardless of production difficulties, has been widely discussed. The question of licence buy-back by states was also largely questioned. It is recalled here without being discussed further in this article.

Newspapers only consider “rich” countries in order to find out the arrival times and the distribution of the different vaccines. They forget the problem of the globalisation of drugs. In fact, we observe that the concerns of the media and governments relate solely to their countries, recalling the adage that was previously developed for HIV drugs “patients are in the South and drugs in the North”. Two thirds of COVID-19 deaths occur outside Europe…

We could continue this discussion underlying reluctance of “developed countries” to accept vaccines manufactured by countries with a pharmaceutical industry not currently recognised on a global scale: Russia, China, etc. Similarly, we can observe that Western countries (US, Europe) are trying to keep the drugs for their own populations, while large Asian countries (Russia, China) are rushing to export their vaccines to continents such as Africa that do not have access to Western vaccines: a good example of the economic and political war over drugs. In fact, if we want to push the reasoning further, we can ask ourselves whether there is not some form of nationalism in the field of discovery, development and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

Conclusion

All these data, comments and reflections clearly indicate that drugs in general and vaccines in particular are no longer today just a scientific and medical object but also a social (societal) and political topic [14]. With the pragmatic aim of restoring confidence in vaccination, increasing vaccination safety and coverage, we can recall recommendations of the 2018 Giens round table on vaccines [12]:

-

•

develop information systems and data production;

-

•

simplify the vaccination process and increase opportunities for vaccination;

-

•

develop training for health professionals

-

•

learn about vaccines in school

-

•

use motivational interviewing in educational intervention

-

•

undertake local initiatives;

-

•

improve supply and communicate the value of vaccines.

Council of Europe has also made a number of proposals in the field [15].

These actions and trainings to be developed are the only means to allow our fellow citizens to understand the medical and societal stakes of the current vaccination campaign against COVID-19 as well as those which will undoubtedly occur in the future. In this sense, social pharmacology is an important part of rational drug evaluation (i.e. clinical pharmacology). The skills of social pharmacology should be taken into account and integrated into drug policies in all countries. The health of our citizens is at stake.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding source

The work was performed during the university research time of the authors. There were no funding sources. The authors certify that they have not received any funding from any institution, including personal relationships, interests, grants, employment, affiliations, patents, inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony for the last 48 months.

References

- 1.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadoff J., Le Gars M., Shukarev G., Heerwegh D., Truyers C., de Groot A.M., et al. Interim results of a phase 1-2a trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(19):1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logunov D.Y., Dolzhikova I.V., Shcheblyakov D.V., Tukhvatulin A.I., Zubkova O.V., Dzharullaeva A.S., et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):671–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deplanque D., Launay O. Efficacy of Covid-19 vaccines: from clinical trials to real life. Therapie. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacroix C., Salvo F., Gras-Champel V., Gautier S., Valnet-Rabier M.B., Grandvuillemin A., et al. French organization for the pharmacovigilance of COVID-19 vaccines: a major challenge. Therapie. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pariente A., Bezin J. Evaluation of Covid-19 vaccines: pharmacoepidemiological aspects. Therapie. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2021.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montastruc J.L. Social pharmacology: a new topic in clinical pharmacology. Therapie. 2002;57:420–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mbongue T.B., Sommet A., Pathak A., Montastruc J.L. “Medicamentation” of society, non-diseases and non-medications: a point of view from social pharmacology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(4):309–313. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0925-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward J.K., Peretti-Watel P., Bocquier A., Seror V., Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy and coercion: all eyes on France. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1257–1259. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutilleul A., Morel J., Schilte C., Launay O., participants of Giens XXXIV Round Table “hot topic No. 1” How to improve vaccine acceptability (evaluation, pharmacovigilance, communication, public health, mandatory vaccination, fears and beliefs) Therapie. 2019;74(1):131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward J.K., Caroline Alleaume C., Peretti-Watel P., the COCONEL Group The French public's attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Social Sci Med. 2020;265:113414. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordet R. Is the drug a scientific, social or political object? Therapie. 2020;75:389–391. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Council of Europe . 2021. Covid-19 vaccines: ethical, legal and practical considerations. Resolution 2361. https://pace.coe.int/en/files/29004/html [Accessed 21 May 2021] [Google Scholar]