Abstract

Genetic testing in a multisite clinical trial network for inherited eye conditions is described in this retrospective review of data collected through eyeGENE®, the National Ophthalmic Disease Genotyping and Phenotyping Network. Participants in eyeGENE were enrolled through a network of clinical providers throughout the United States and Canada. Blood samples and clinical data were collected to establish a phenotype:genotype database, biorepository, and patient registry. Data and samples are available for research use, and participants are provided results of clinical genetic testing. eyeGENE utilized a unique, distributed clinical trial design to enroll 6,403 participants from 5,385 families diagnosed with over 30 different inherited eye conditions. The most common diagnoses given for participants were retinitis pigmentosa (RP), Stargardt disease, and choroideremia. Pathogenic variants were most frequently reported in ABCA4 (37%), USH2A (7%), RPGR (6%), CHM (5%), and PRPH2 (3%). Among the 5,552 participants with genetic testing, at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant was observed in 3,448 participants (62.1%), and variants of uncertain significance in 1,712 participants (30.8%). Ten genes represent 68% of all pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in eyeGENE. Cross-referencing current gene therapy clinical trials, over a thousand participants may be eligible, based on pathogenic variants in genes targeted by those therapies. This article is the first summary of genetic testing from thousands of participants tested through eyeGENE, including reports from 5,552 individuals. eyeGENE provides a launching point for inherited eye research, connects researchers with potential future study participants, and provides a valuable resource to the vision community.

Keywords: gene therapy, genetic testing, inherited retinal disease, rare eye disease

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The eyeGENE Network is a precision medical genetics initiative created by the National Eye Institute (NEI), of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), to facilitate research into the causes and mechanisms of inherited eye diseases. This was accomplished through a network of collaborators to create broad access to clinical molecular genetic diagnostic testing before diagnostic testing for these diseases was widely available. DNA samples collected were curated for a research biorepository from participants with inherited eye conditions and their family members. The goal of this project is to allow investigations into the causes, interventions, and management of genetic eye disorders. The Network is a model partnership between the US federal government, health care providers, CLIA-approved molecular diagnostic laboratories, private industry, and extramural scientists who support a broad research constituency. Importantly, phenotypic, and genotypic data is made publicly available through research application, while patient health information is protected.

Thirty years ago, clinicians could do little more than concede to individuals with an inherited eye disease that there were no treatments available to them. Over time, new information and technologies have improved ophthalmic genetic clinical and molecular diagnosis and management. During the ensuing three decades, vision scientists have identified nearly 600 genes related to eye disorders. This wealth of genetic information has provided significant inroads for understanding the molecular basis of human ophthalmic diseases, and has paved the way for clinical trials targeting these pathogenic mechanisms.

The eyeGENE Network was created in 2006 to address vision community needs to establish disease–gene relationships by wide-spread molecular genetic testing, which would poise the community for gene-based therapies being rapidly developed (Blain, Goetz, Ayyagari, & Tumminia, 2013). At its inception, slightly over 100 retinal disease genes had been described in the literature (RetNet—Retinal Information Network, n.d.). Clinical molecular diagnostics was expanding to include ophthalmic genetics and other subspecialties. However, insurance policies did not routinely include coverage, and genetic testing was cost-prohibitive for most individuals. As a result, genetic testing was inaccessible to many patients, yet critical to confirming disease etiology and family recurrence. eyeGENE sought to address this issue by providing access in a standardized fashion for many rare eye disease indications (Goetz, Reeves, Tumminia, & Brooks, 2012). Over the next 10 years, eyeGENE gained broad adoption from 233 clinical sites throughout North America and accrued over 6,400 participants from 5,385 families. eyeGENE has now successfully genotyped nearly all participants and continues to facilitate research investigations for genetic causes of rare eye conditions for unsolved cases.

The eyeGENE Network, which includes 412 clinical users and 13 commercial and academic Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) diagnostic laboratory partners, has generated a rich resource of phenotypic and genotypic information. The carefully curated biospecimen repository (Parrish et al., 2016) follows best practices of the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories (ISBER) (“2012 Best Practices for Repositories Collection, Storage, Retrieval, and Distribution of Biological Materials for Research International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories,”; Anonymous, 2012) and permits controlled research access. Secondary research studies have the potential to gain important new insights for treatment and biological understanding of rare, inherited eye diseases. Academic and industry partners can identify specific diseases, phenotypes, genes, variants, or samples of interest for genetic discovery and patient recruitment for natural history studies and clinical trials. By providing clinical genetic results to participants, eyeGENE promoted access to gene-based clinical trials that are only possible with genetic confirmation of diagnosis.

This article outlines the eyeGENE Network diagnostic testing pathway and highlights important findings from the genotyping of thousands of patients with a variety of heritable eye conditions including RP, Stargardt disease, cone-rod dystrophy, Usher syndrome, and others. Over the infancy and maturation of clinical molecular diagnostic testing since 2006, we observed changes in diagnostic technologies, testing strategies, and variant classification, leading to the current postgenomic era.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Consent and ethics approval

All participants and their family members gave written informed consent for participation in eyeGENE. Consent described storage and secondary use of data and samples. Participants also provided consent for genetic testing. The study received approval through the NIH IRB (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00378742) and conforms to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Common Rule. The written consent provides opportunity for participants to indicate their willingness to be contacted for participation in other studies. Over 95% of participants selected the option to be contacted for additional research.

2.2 |. Genetic testing decision process

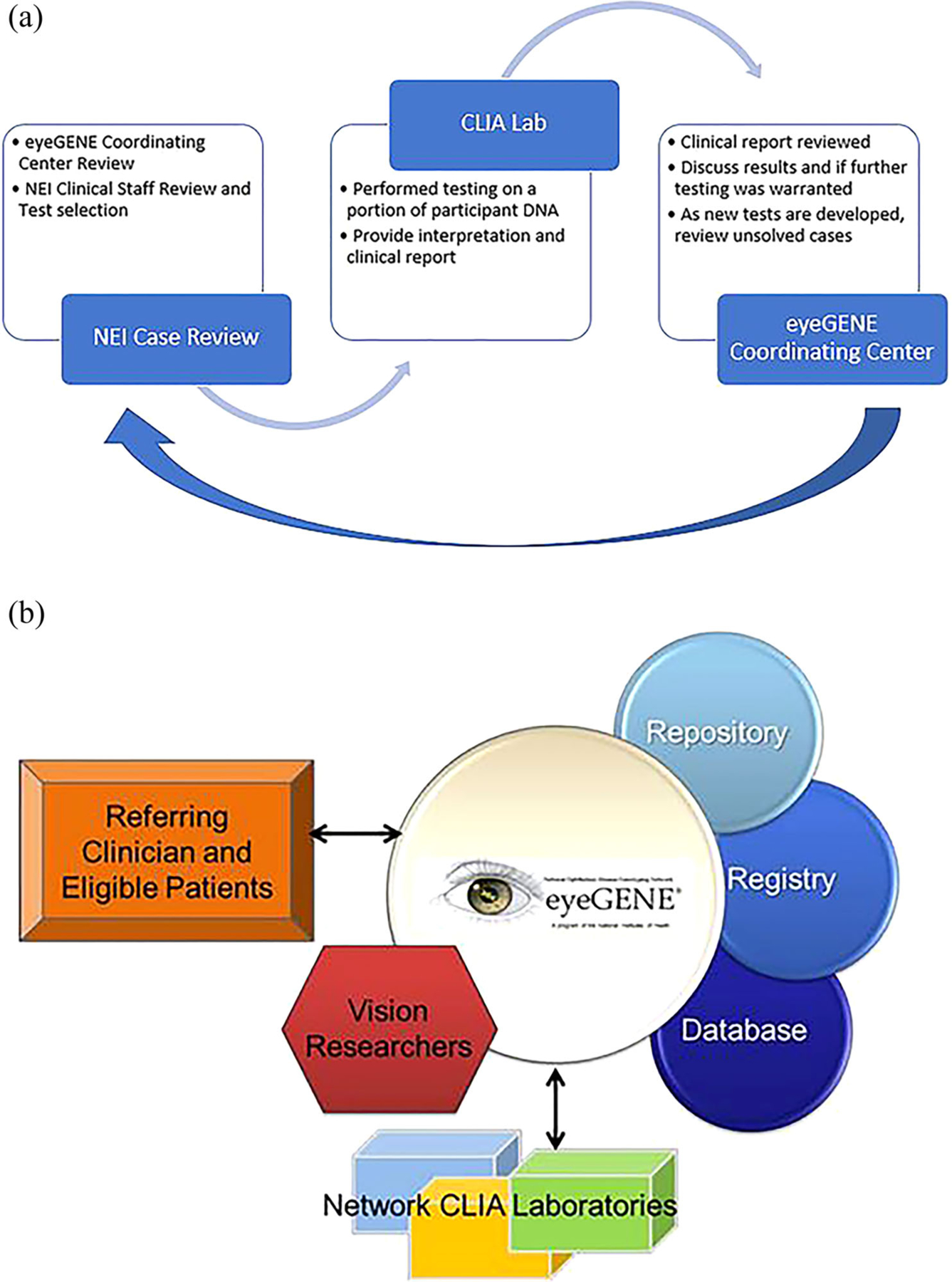

The eyeGENE review process is depicted in Figure 1. Upon receipt of clinical data for a participant, the case was reviewed by the eyeGENE Coordinating Center (CC). The CC would check that the case report form was complete and confirm that the inheritance pattern selected matched the family history that was reported. Once the primary review was complete, a member of the NEI ocular genetics clinical staff would review and indicate the appropriate genetic testing to be ordered.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Flowchart describing the case review of eyeGENE participants for genetic screening requisition. The eyeGENE Coordinating Center (CC) reviews the clinical details and family history. Further review is performed by NEI Clinicians. The appropriate genetic test is requested through a Network CLIA laboratory and clinical report returned to the CC. The report is reviewed, and a decision is made to determine if additional testing is warranted. As new tests were developed, older test reports were re-reviewed. (b) Framework of the eyeGENE Network. Referring clinicians submit clinical details and a blood sample for eligible, consenting participants. Clinical data, and genetic data submitted by testing in CLIA laboratories form the eyeGENE Database. Many participants opted to be part of the Registry to be contacted for additional clinical trials. DNA extracted from the blood samples create the eyeGENE Repository. Researchers may request access to samples, data, and to have the Coordinating Center contact Registry participants on their behalf

Testing was limited to the options offered by clinical molecular diagnostics laboratories under contract to the program at that time, typically single gene or gene panel testing prior to 2017. Tests were considered based on the likelihood of identification of a genetic cause of the eye condition and with cost effectiveness in mind. Patients with an RP diagnosis and without known X-linked or dominant inheritance were tested starting in 2017 when Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) panels containing most known RP genes were available at reasonable cost. Fixed annual eyeGENE operating budget-imposed limitations on the number of tests that could be run annually, and so testing was performed to maximize resource usage.

A de-identified portion of the participant’s DNA sample is sent to a Network clinical lab for analysis. When testing is completed, the lab issues a genetic test report and provides genetic data for the eyeGENE research database. The eyeGENE CC then reviews the report and determines if the case warrants additional testing to identify the genetic basis of the disease. Since testing has become more economical, covering larger numbers of genes with increased clinical validity, unsolved cases are continually re-reviewed for additional testing on a routine basis.

3 |. RESULTS

The eyeGENE utilized a unique, distributed clinical trial design comprised of three essential elements. First, community-based health care providers consented patients for sharing their de-identified clinical data and genetic information as part of eyeGENE. Participants were also asked if they would like to be part of a patient registry to be contacted by the eyeGENE CC for future research. Second, the participant provided a blood sample from which DNA was extracted and used to create a biorepository, which is used for diagnostic molecular evaluation (through Network laboratories) as well as research use by vision researchers. Third, researchers applied for access to de-identified DNA samples and clinical information to investigate genotype/phenotype relationships and causal variants of eye disease. Figure 1b depicts how these elements intersect in a coordinated fashion.

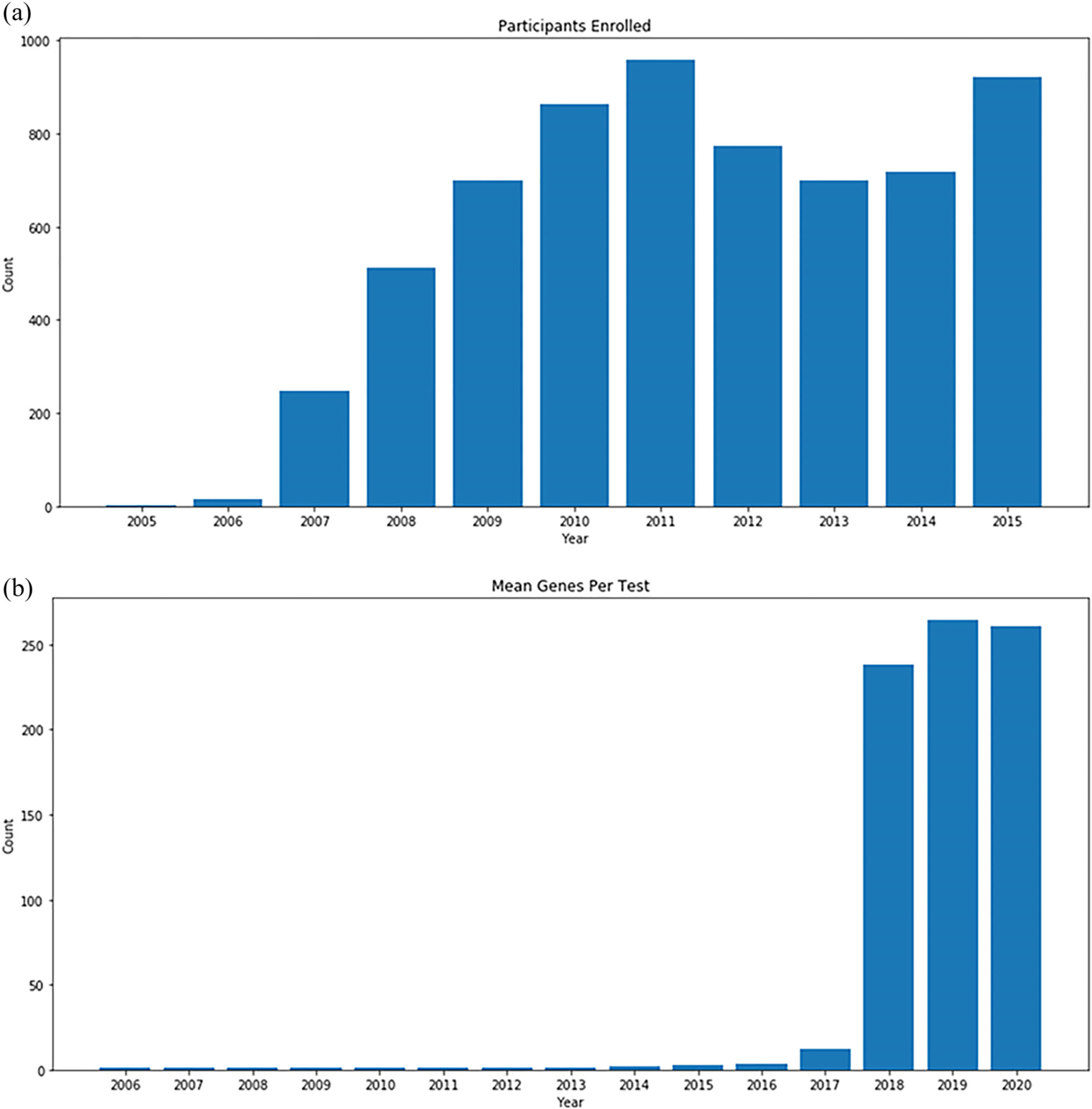

From 2006 to 2015, eyeGENE received 57 participant enrollments per month on average, with a peak of 115 participants in December 2015, the last month that the program accepted new enrollments (Figure 2a). Data from eyeGENE is currently available for approved-access secondary research use through the NEI Data Commons (https://neidatacommons.nei.nih.gov/) in the Biomedical Research Informatics Computing System (BRICS) (Navale et al., 2020). Additional information for access and use is outlined on the eyeGENE website (eyeGENE.nih.gov). At the time of this publication, 27 investigators have used the resource in support of their research.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Total count of eyeGENE participants enrolled every year from the start of the program (2006) to the end of recruitment (2015). (b) Average number of genes per test request from 2006 to current

3.1 |. Cohort description

The eyeGENE database currently includes data from 6,403 participants from 5,378 families. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the cohort. Overall, there are 3,221 females and 3,182 males. The average age upon enrollment was 44 years. RP was the most recurrent clinical diagnosis (2,070). This diagnosis category included all inheritance patterns (autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and sporadic/unknown). The next most common diagnoses were Stargardt disease (1,295), cone-rod dystrophy (460), pattern dystrophy and adult onset foveomacular dystrophy (263), and choroideremia (234). Additionally, 474 unaffected family members were enrolled.

TABLE 1.

Number of eyeGENE participants enrolled by diagnosis category including male, female and mean age

| Enrolled | Female | Male | Mean age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 6,403 | 3,218 | 3,185 | 44 |

| Achromatopsia | 36 | 17 | 19 | 21 |

| Albinism | 59 | 21 | 38 | 21 |

| Aniridia | 47 | 22 | 25 | 27 |

| Axenfeld–Rieger | 11 | 7 | 4 | 19 |

| BEST disease | 216 | 114 | 102 | 48 |

| Bietti crystalline corneal–retinal dystrophy | 29 | 20 | 9 | 54 |

| Choroideremia | 234 | 40 | 194 | 47 |

| Chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (CPEO) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 34 |

| Cone-rod dystrophy | 460 | 197 | 263 | 47 |

| Congenital cranial dysinnervation syndrome | 7 | 4 | 3 | 20 |

| Congenital stationary night blindness/Oguchi disease | 78 | 16 | 62 | 21 |

| Corneal dystrophy | 47 | 27 | 20 | 46 |

| Doyne honeycomb dystrophy | 91 | 71 | 20 | 52 |

| Enhanced S-cone syndrome | 3 | 2 | 1 | 36 |

| FEVR | 136 | 77 | 59 | 21 |

| Familial/congenital nystagmus (X-linked cases only) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Fundus albipunctatus/Bothnia retinal dystrophy | 5 | 1 | 4 | 25 |

| Glaucoma | 12 | 4 | 8 | 32 |

| Hermansky Pudlak syndrome | 3 | 1 | 2 | 33 |

| Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy | 4 | 1 | 3 | 22 |

| Juvenile X-linked retinoschisis | 176 | 9 | 167 | 31 |

| Kearns–Sayre syndrome/progressive external ophthalmoplegia | 7 | 5 | 2 | 37 |

| Leber hereditary optic neuropathy | 48 | 16 | 32 | 38 |

| Lowe syndrome | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Microphthalmia/anophthalmia | 24 | 9 | 15 | 9 |

| Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes | 11 | 4 | 7 | 46 |

| Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulations | 4 | 1 | 3 | 44 |

| Neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa | 3 | 2 | 1 | 54 |

| Occult macular dystrophy | 32 | 20 | 12 | 52 |

| Optic atrophy | 125 | 56 | 69 | 39 |

| Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration | 13 | 11 | 2 | 35 |

| Pattern dystrophy and adult onset foveomacular dystrophy | 263 | 159 | 104 | 60 |

| Retinitis pigmentosa and other retinal degenerations | 2070 | 1,025 | 1,045 | 47 |

| Retinoblastoma | 122 | 59 | 63 | 16 |

| Sorsby dystrophy | 33 | 19 | 14 | 58 |

| Stargardt disease | 1,295 | 750 | 545 | 45 |

| Stickler syndrome | 22 | 12 | 10 | 23 |

| Unaffected family members | 474 | 299 | 175 | 48 |

| Usher syndrome | 199 | 119 | 80 | 43 |

Race and ethnicity were collected for individuals based on the categories devised by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (About Race—Census Bureau, n.d.). Table 2 describes the race and ethnicity of the eyeGENE cohort. Most participants (4,483; 70%) are non-Hispanic or Latino, White. Hispanic and Latino participants represent approximately 10% (612) of the cohort. Four hundred and eighty-six (8%) participants are Black or African American, 350 (5%) are Asian, and 34 (0.5%) are American Indian or Alaska Native. One hundred and eleven (2%) people identified as more than one race. The remaining 10% of the cohort are unknown or did not report race and ethnicity. These cohort characteristics roughly represent the demographics reported in the 2019 U.S. census (Quick Facts—United States, n.d.).

TABLE 2.

Race and ethnicity of eyeGENE participants and proportion of total participants

| Hispanic or Latino | % of Total | Not Hispanic or Latino | % OF total | Unknown | % of total | Total | % of total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 612 | 9.56% | 5,521 | 86.23% | 270 | 4.22% | 6,403 | 100.00% |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 2 | 0.03% | 31 | 0.48% | 1 | 0.02% | 34 | 0.53% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; Asian | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.03% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.03% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; Asian; White | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.03% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.03% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; Black or African-American | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.12% | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.12% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; Black or African-American; White | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.12% | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 0.12% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; unknown | 1 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; unknown; White | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% |

| American Indian or Alaska native; White | 4 | 0.06% | 29 | 0.45% | 1 | 0.02% | 34 | 0.53% |

| Asian | 1 | 0.02% | 347 | 5.42% | 2 | 0.03% | 350 | 5.47% |

| Asian; Black or African-American | 1 | 0.02% | 3 | 0.05% | 0 | 0.00% | 4 | 0.06% |

| Asian; Black or African-American; White | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% |

| Asian; native Hawaiian or other Pacific | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% |

| islander | ||||||||

| Asian; native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander; unknown | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.02% |

| Asian; unknown | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% |

| Asian; White | 0 | 0.00% | 13 | 0.20% | 0 | 0.00% | 13 | 0.20% |

| Black or African-American | 2 | 0.03% | 475 | 7.42% | 9 | 0.14% | 486 | 7.59% |

| Black or African-American; unknown | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% | 0 | 0.00% | 3 | 0.05% |

| Black or African-American; White | 1 | 0.02% | 27 | 0.42% | 0 | 0.00% | 28 | 0.44% |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander | 1 | 0.02% | 16 | 0.25% | 1 | 0.02% | 18 | 0.28% |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander; White | 3 | 0.05% | 4 | 0.06% | 1 | 0.02% | 8 | 0.12% |

| Unknown | 378 | 5.90% | 49 | 0.77% | 217 | 3.39% | 644 | 10.06% |

| Unknown; White | 4 | 0.06% | 12 | 0.19% | 2 | 0.03% | 18 | 0.28% |

| White | 214 | 3.34% | 4,483 | 70.01% | 36 | 0.56% | 4,733 | 73.92% |

3.2 |. Genetic testing results

Summary genetic testing data is available on the eyeGENE website (eyeGENE.nih.gov/data), including the number of participants for each of the 38 diagnostic categories, variants detected per gene, and variant classification by gene. As of the time of this writing, 3,448 eyeGENE participants have been reported to have at least one pathogenic or likely pathogenic genetic variant. The 10 most frequently reported genes were ABCA4 (1799, 37%), USH2A (316, 7%), RPGR (283, 6%), CHM (219, 5%), PRPH2 (161, 3%), RS1 (142, 3%), RHO (130, 3%), BEST1 (114, 2%), EYS (67, 1%), and PRPF31 (62, 1%). These 10 genes represent 68% of all pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in eyeGENE. Two thousand one hundred and four participants have genetic results where no pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant was found. Variants of uncertain significance were identified in 1,712 individuals.

3.3 |. Genetic testing strategies over time

Next, we evaluated the development of genetic testing strategies over time. Since eyeGENE began genetic testing for eye conditions in 2006, clinical genetic testing strategies have shifted, largely based on technology developments. Between 2006 and 2016, testing was typically Sanger sequencing of the most clinically relevant gene or genes (1–3 per test on average), including site-directed testing of specific recurrent variants in the literature. Beginning in 2017, the average number of genes screened per participant increased due to the addition of several multigene Sanger and NGS panel tests, followed by large NGS panel tests covering more than 200 genes associated with syndromic and nonsyndromic retinal dystrophy. More recently, panels analyzing a subset of eye disease-related genes from exome sequencing have emerged. These NGS-based panels became routinely available as single tests appropriate for multiple clinical diagnostic categories of heritable retinopathies, in particular sporadic RP, by querying many more genes per test. Figure 2b shows the average number of genes per test since 2006, reflecting the sharp increase in genes per test utilized in clinical molecular diagnostics.

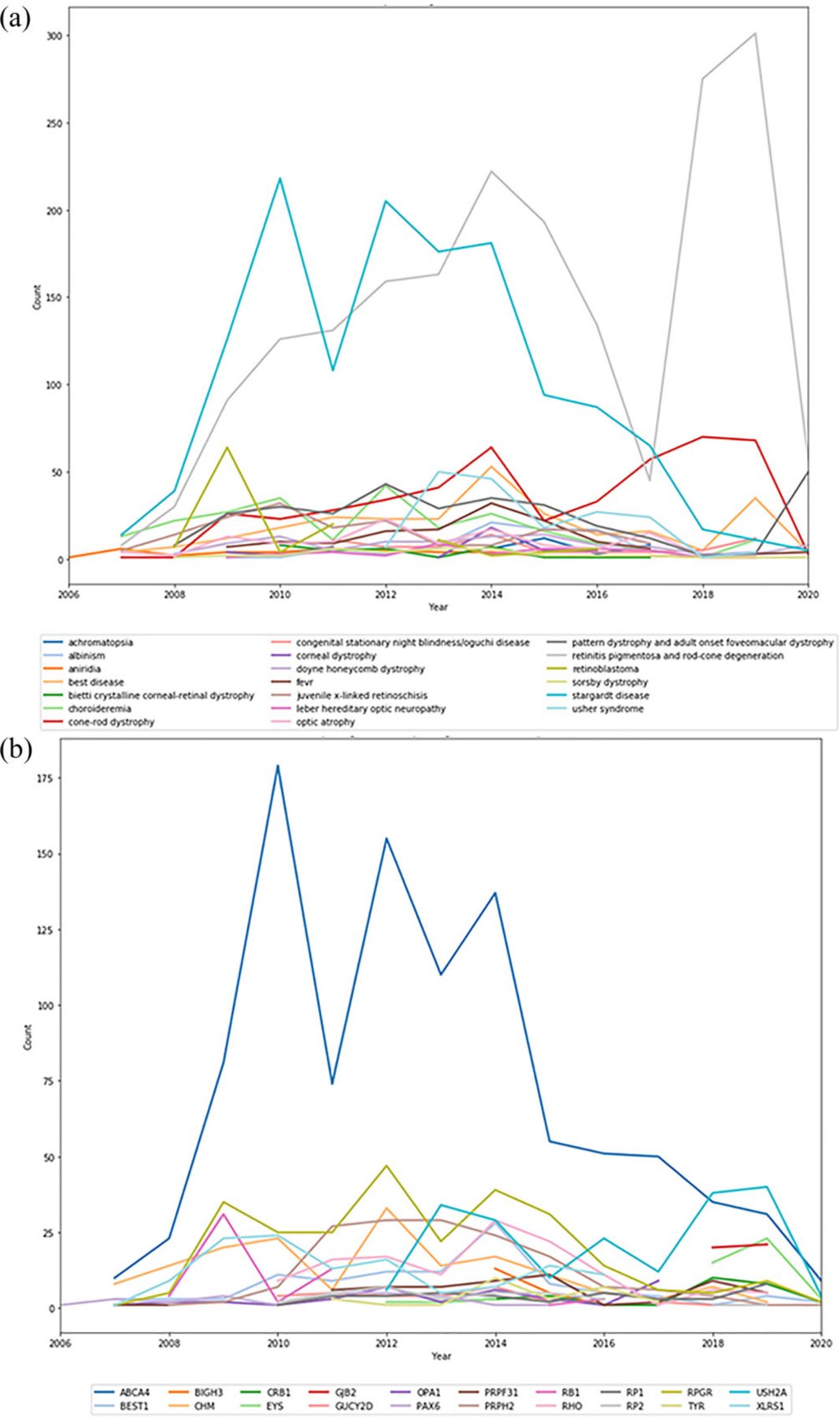

Changes in technology, coupled with the identification of many more genes associated with genetically heterogeneous conditions, allowed for participants with isolated or recessive cases of RP to be tested in a cost-effective manner. Prior to 2017, most eyeGENE RP participants had been on hold for testing due to the expense of RP panels. Figure 3a shows the clinical diagnosis for tests ordered through eyeGENE over time for the 20 most frequent diagnosis categories. Participants diagnosed with Stargardt disease, which made up the second highest accrual category, were the most frequently tested in the beginning of the program, given the limited number of genes associated with this clinical diagnosis (ABCA4, PRPH2, PROM1, ELOVL4, and others). Later, as the number of genes per test increased, this was finally surpassed by RP, the highest accrued clinical diagnosis. The sharp increase in RP testing starting in 2017 was due to the availability of multi-gene panels and largely reflected testing isolated familial cases. Prior to 2017, testing of patients with RP enrolled in eyeGENE was limited to dominant or X-linked cases with clear family history, sequencing for RPGR including ORF15 or RP2 for X-linked cases, and a small number of genes and recurrent pathogenic variants for sporadic cases.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Diagnosis of samples sent for testing from eyeGENE to Network CLIA laboratories from 2006 to June 2020. Limited to the top 20 diagnosis counts. (b) Most often reported genes with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants from 2006 to June 2020. Limited to the top 20 genes

Increased adoption of NGS technologies permitted development of broader clinical molecular diagnostic panels and shifted diagnostic strategies from disorders with limited locus heterogeneity such as Stargardt Disease to broader locus heterogeneity such as RP. We then assessed how this shift impacted the positive diagnostic rates by gene over time, defined as pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants classified by the clinical laboratory completing the test. As expected, ABCA4 dominated the genes tested prior to 2017 and made up the greatest proportion of pathogenic variants reported. Beginning in 2018, pathogenic variants in USH2A in patients with nonsyndromic RP accounted for a greater proportion of overall reports than ABCA4, reflecting increased availability and utility of NGS panels for this clinical diagnosis (Figure 3b).

3.4 |. Changes in variant interpretation over time

Variant data provided by clinical diagnostic laboratories to eyeGENE is standardized to Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) nomenclature and imported to BRICS for research queries. Clinical variant interpretations are provided by the laboratory at the time of report. Variant interpretation has changed rapidly during the duration of the eyeGENE program. Over the last 15 years, several variant interpretations have changed based on increased research knowledge and analysis tools. In 2015, the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association for Molecular Pathology published a consensus document for clinical variant interpretation, which included different evidence types from prior publications and public databases, including allele frequency in the general population (ExAC, gnomAD), functional predictions and experimental evidence, and the strength of gene:variant: phenotype associations (Richards et al., 2015). Based on a combination of available evidence, these are classified into five categories: benign, likely benign, uncertain significance, likely pathogenic, and pathogenic.

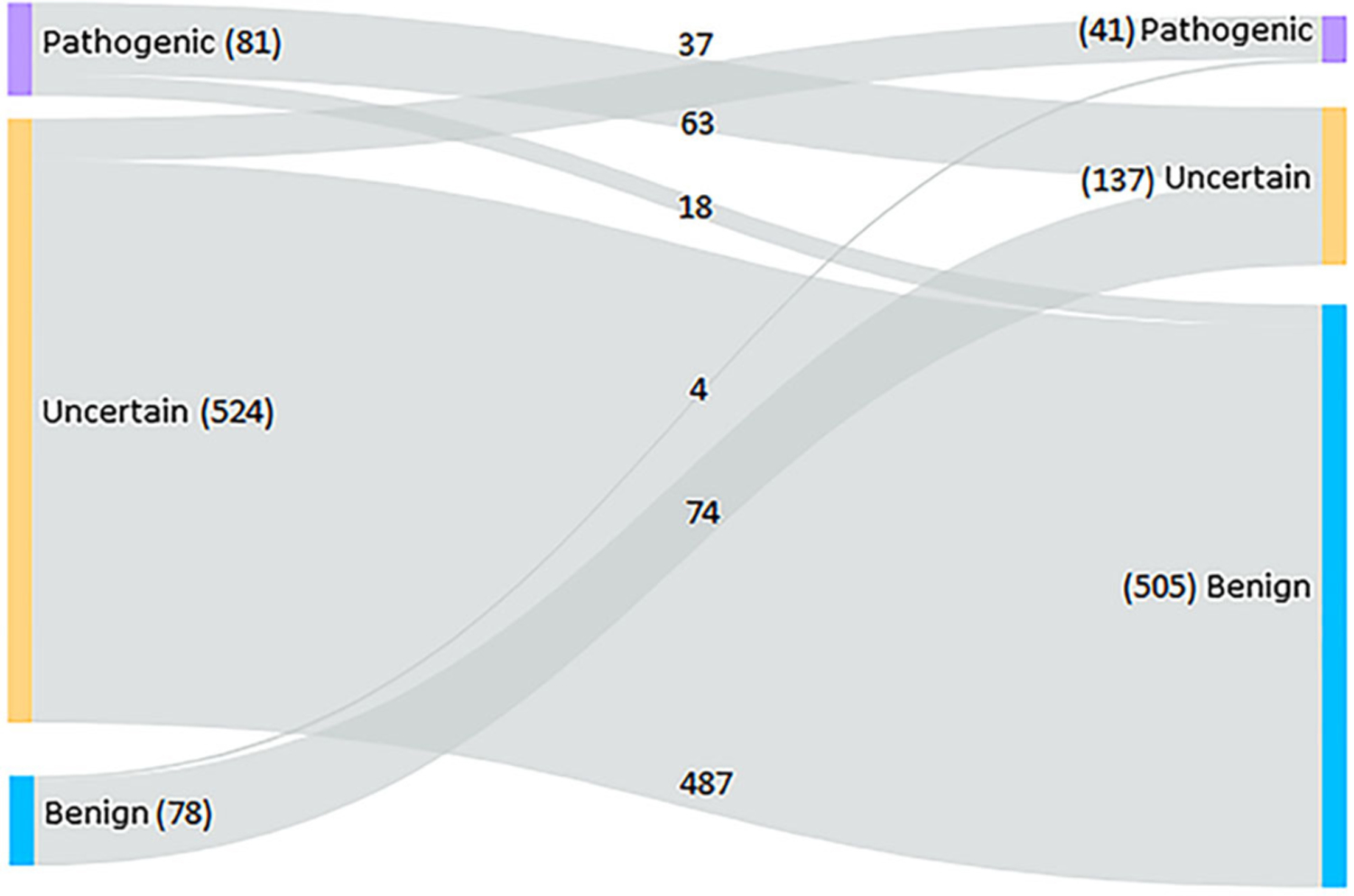

As evidence for variant–disease associations becomes available over time, we predicted that clinical interpretations of recurrent variants observed in patients enrolled in eyeGENE would change over time as well. To evaluate clinical classification changes for individual variants over time, recurrent variants among patients in the eyeGENE database were queried for those changing interpretations at least once (Table S2), and grouped by direction of change among benign, uncertain, and pathogenic categories. Variants were included in the analysis regardless of their initial or final pathogenic status. Two hundred and thirty-five variants were reported with changed interpretations (Figure 4). Intriguingly, the number of pathogenic variants was cut nearly in half (81 initial vs. 41 final classification), while the number of uncertain variants decreased, and the number of benign variants increased dramatically. These changes in variant classification trends across the span of the eyeGENE program suggest that iterations in variant classification schema reduce the burden of uncertain variants, properly classify variants as benign, and refine the pool of pathogenic variants contributing to disease burden.

FIGURE 4.

Sankey chart depicting variants with interpretations that have been reported inconsistently in the eyeGENE Database over time. The left side shows the first observed interpretation and the right side is the most recently observed interpretation

3.5 |. Gene therapies

The eyeGENE program has been a beneficial diagnostic and research resource for many patients and families. With the development of several gene-specific therapies for inherited eye conditions, we evaluated the genetic testing results to determine how many patients have pathogenic or likely pathogenic alleles in the genes targeted by these therapies. A search of clinicaltrials.gov was performed across all participant diagnoses and associated genes in eyeGENE. Studies were identified by searching clinicaltrials.gov. The search terms used were “Inherited Eye Disease” in the “condition or disease” field and “Gene Therapy” in the “other terms” field. The resulting studies were categorized by targeted gene and the number of participants with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in that gene was calculated. Results include all studies including active and completed. The total number of patients with pathogenic or likely pathogenic alleles in a gene targeted for clinical therapeutic trials is 1,654, though this does not account for other clinical or molecular inclusion or exclusion criteria. Results are shown in Table S1. In summary, there are potentially over a thousand participants in eyeGENE who could be eligible for clinical trials, considering their molecular results alone.

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Genetic testing advances

The eyeGENE program has been present since nearly the beginning of clinical molecular diagnostic testing for ophthalmic genetic disorders. Genetic testing has evolved dramatically over time since eyeGENE began accepting participants. When eyeGENE began in 2006, the Ret-Net database included less than 150 retinal disease genes. Currently, there are over 250 identified genes associated with retinal degenerations. Until 2017, most eyeGENE test requisitions outlined a single gene or a small gene panel request, and now all are run on NGS panels assessing hundreds of disease-associated genes. This also reflects and improvement in providing molecular diagnoses for diseases with massive locus heterogeneity such as RP. This increased efficiency has also improved molecular diagnostic yield, with 3,448 participants (62.1%) determined to have pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant, and variants of uncertain significance in 1,712 participants (30.8%). As such, the eyeGENE dataset offers a unique perspective spanning multiple phases of directed and massive parallel sequencing techniques, rapid disease gene discovery, variant classification and reporting, and the emergence of gene therapy.

Genetic testing and related technology rapidly evolved since the mapping of the first human genes associated with clinical retinal degeneration (Figure S1). From the mapping of the human genome to the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in the first clinical treatment trial, technology continues to shape diagnostics and treatment strategies. Following cytogenetics, development of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ushered in the field of molecular genetics emerged (Durmaz et al., 2015). Subsequently, Sanger sequencing and mapping of the human genome allowed gene-targeting and mutation-specific test development. NGS greatly increased the throughput of genes sequenced and reduced the per-base cost (Durmaz et al., 2015; Totomoch-Serra, Marquez, & Cervantes-Barragán, 2017).

Whole exome sequencing (WES) and NGS panels have traditionally focused on protein-coding regions of the genome, but there are limitations on detection of other variation outside of these regions, as well as large deletions and duplications (Ellingford et al., 2016). Comparatively, whole genome sequencing (WGS) can detect variants throughout the genome that would otherwise be missed by NGS and WES methods. A recent study by Ellingford et al. detected 14 additional disease-causing variants in 46 individuals with inherited retinal dystrophies which were not previously found with NGS techniques. As of July 2020, over 100 labs from across the world are now offering over 550 clinical WES/WGS tests (GTR: Genetic Testing Registry, n. d.). While WGS seems to be the most comprehensive test available to date, there still remains difficulty in result analysis, understanding the diagnostic utility, and relative cost of the test alongside limited insurance coverage for WGS testing (Gilissen et al., 2014; Lupski et al., 2010).

For rare diseases, there have been many challenges implementing NGS as a diagnostic standard including lack of rare disease knowledge, turnaround time for results, and cost of the testing (Liu, Zhu, Roberts, & Tong, 2019). Additionally, symptoms of rare disease can be masked by common disorders, so recognizing and understanding the etiology of rare diseases is important (Liu et al., 2019). When compared with traditional chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), the diagnostic detection rate in rare diseases, generally, is only 0.10 as opposed to 0.36 and 0.41 for WES and WGS, respectively (Liu et al., 2019). It is estimated that the clinical utility of testing could be increased by 50–80% by employing CMA in combination with WES/WGS (Clark et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019).

In ophthalmology, genomics has been considered a specialized field, but the expanded availability of testing and knowledge of newly associated genes has allowed this area to grow dramatically (Black, MacEwen, & Lotery, 2020). Treatment trials, such as those for the RPE65 gene, have given hope to individuals that therapy may be available soon. In fact, eyeGENE was the first national network created specifically to encourage research in ophthalmic genetics (Brooks et al., 2008). While eyeGENE began testing single genes, as testing expanded from single gene to multigene panels, eyeGENE is now able to offer its participants testing for hundreds of genes. This additional information allows more individuals to confirm or refine their clinical diagnosis, while permitting research access to thousands of participants’ data. Large cohorts are important in achieving statistical power in research associations, and so networks like eyeGENE are an important part of the ophthalmic research and rare disease communities (Peter & Seddon, 2010).

4.2 |. Study limitations

There are several limitations to the eyeGENE data. First, the data in eyeGENE was collected by many users over several years. The clinical diagnosis and demographics information might be impacted by bias or false assumptions. For example, the high rate of unknown race and ethnicity might be due to the clinical staff entering data later than the patient visit and not having the information indicated in the patient chart. Additionally, some diagnoses in eyeGENE have heterogeneous clinical presentations, and although the referring clinician was permitted to add multiple diagnoses per patient, this analysis only considers the primary diagnosis. Finally, several clinical testing laboratories were used for testing with multiple testing methods. Some laboratories continue to update variant interpretation changes, but others do not.

5 |. CONCLUSION

This article is the first to report summary details of genetic testing from thousands of participants tested through eyeGENE. Our data includes reports from 5,552 individuals with inherited eye conditions and are available through controlled access through the NEI Data Commons. Demographics, family history, participant-level clinical data, images and corresponding files are available for many of the individuals enrolled. This data repository, coupled with a DNA repository and patient registry, provides a launching point for inherited eye research, connects researchers with potential future study participants, and provides a valuable resource to the vision community.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Eye Institute. We appreciate the efforts of the eyeGENE Working Group, past and present, who have contributed to the project and the participation of the patients, researchers, and clinical staff who have made eyeGENE a valuable resource.

Funding information

National Eye Institute; Intramural Research Program of the NIH

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data is publicly available or available upon request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- About Race—Census Bureau. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html

- Best Practices for Repositories Collection, Storage, Retrieval, and Distribution of Biological Materials for Research International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories. (2012). Biopreservation and Biobanking, 10(2), 79–161. 10.1089/bio.2012.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black GC, MacEwen C, & Lotery AJ (2020). The integration of genomics into clinical ophthalmic services in the UK. Eye, 34(6), 993–996. 10.1038/s41433-019-0704-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain D, Goetz KE, Ayyagari R, & Tumminia SJ (2013). eyeGENE®: A vision community resource facilitating patient care and paving the path for research through molecular diagnostic testing. Clinical Genetics, 84(2), 190–197. 10.1111/cge.12193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BP, Macdonald IM, Tumminia SJ, Smaoui N, Blain D, Nezhuvingal AA, … National Ophthalmic Disease Genotyping Network (eyeGENE). (2008). Genomics in the era of molecular ophthalmology: Reflections on the National Ophthalmic Disease Genotyping Network (eyeGENE). Archives of Ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill.: 1960), 126(3), 424–425. 10.1001/archopht.126.3.424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W, Liu T, Tikhonova IR, Zumbo P, … Lifton RP (2009). Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(45), 19096–19101. 10.1073/pnas.0910672106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, Stark Z, Farnaes L, Tan TY, White SM, Dimmock D, & Kingsmore SF (2018). Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genomic Medicine, 3 (1), 16. 10.1038/s41525-018-0053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, McGee TL, Hahn LB, Cowley GS, Olsson JE, Reichel E, … Berson EL (1990). Mutations within the rhodopsin gene in patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. New England Journal of Medicine, 323(19), 1302–1307. 10.1056/NEJM199011083231903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz AA, Karaca E, Demkow U, Toruner G, Schoumans J, & Cogulu O (2015). Evolution of genetic techniques: Past, present, and beyond. BioMed Research International, 2015, 461524. 10.1155/2015/461524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingford JM, Barton S, Bhaskar S, Williams SG, Sergouniotis PI, O’Sullivan J, … Black GCM (2016). Whole genome sequencing increases molecular diagnostic yield compared with current diagnostic testing for inherited retinal disease. Ophthalmology, 123(5), 1143–1150. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Thung DT, van de Vorst M, van Bon BWM, Willemsen MH, … Veltman JA (2014). Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature, 511(7509), 344–347. 10.1038/nature13394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz KE, Reeves MJ, Tumminia SJ, & Brooks BP (2012). eyeGENE(R): A novel approach to combine clinical testing and researching genetic ocular disease. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 23(5), 355–363. 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835715c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh G, & Choi M (2012). Application of whole exome sequencing to identify disease-causing variants in inherited human diseases. Genomics & Informatics, 10(4), 214–219. 10.5808/GI.2012.10.4.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTR: Genetic Testing Registry. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/

- Liu Z, Zhu L, Roberts R, & Tong W (2019). Toward clinical implementation of next-generation sequencing-based genetic testing in rare diseases: Where are we? Trends in Genetics, 35(11), 852–867. 10.1016/j.tig.2019.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR, Reid JG, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Rio Deiros D, Chen DCY, Nazareth L, … Gibbs RA (2010). Whole-genome sequencing in a patient with Charcot–Marie–tooth neuropathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(13), 1181–1191. 10.1056/NEJMoa0908094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GA, Brody LC, Looney J, Steel G, Suchanek M, Dowling C, … Valle D (1988). An initiator codon mutation in ornithine-delta-aminotransferase causing gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 81(2), 630–633. 10.1172/JCI113365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navale V, Ji M, Vovk O, Misquitta L, Gebremichael T, Garcia A, Fann Y, McAuliffe M (2020). Development of an informatics system for accelerating biomedical research. F1000Research, 8, 1430. 10.12688/f1000research.19161.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti A, Wong DJ, Kawase K, Gibson LH, Yang-Feng TL, Richards JE, & Thompson DA (1995). Molecular characterization of the human gene encoding an abundant 61 kDa protein specific to the retinal pigment epithelium. Human Molecular Genetics, 4(4), 641–649. 10.1093/hmg/4.4.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.omim.org/

- Parrish RS, Garafalo AV, Ndifor V, Goetz KE, Reeves MJ, Yim A, … Tumminia SJ (2016). Sample confirmation testing: A short tandem repeat-based quality assurance and quality control procedure for the eyeGENE biorepository. Biopreservation and Biobanking, 14(2), 149–155. 10.1089/bio.2015.0098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter I, & Seddon JM (2010). Genetic epidemiology: Successes and challenges of genome-wide association studies using the example of age-related macular degeneration. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 150(4), 450–452.e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick Facts—United States (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120218

- RetNet—Retinal Information Network (n.d.). Retrieved from https://sph.uth.edu/retnet

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, … ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 17(5), 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timeline: History of Genomics (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.yourgenome.org/facts/timeline-history-of-genomics

- Totomoch-Serra A, Marquez MF, & Cervantes-Barragán DE (2017). Sanger sequencing as a first-line approach for molecular diagnosis of Andersen-Tawil syndrome. F1000Research, 6, 1016. 10.12688/f1000research.11610.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.