Abstract

BACKGROUND:

As patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and other preclinical models of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) for testing personalized therapeutics are lacking, we have developed a perfused 3D bioreactor model to culture tumor surrogates from patient-derived NETs. This work evaluates the duration of surrogate culture and surrogate response to a novel antibody-drug conjugate (ADC).

METHODS:

27 Patient-derived NETs were cultured. Histologic sections of a pancreatic NET (pNET) xenograft (BON-1) tumor were assessed for SSTR2 expression before tumor implantation into two bioreactors. One surrogate was treated with ADC comprised an anti-mitotic Monomethyl auristatin-E (MMAE), linked to a somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2) antibody. Viability and therapeutic response were assessed by pre-imaging incubation with IR-783 and the RealTime-Glo™ AnnexinV Apoptosis and Necrosis Assay (Promega) over six days. A primary human pNET was likewise evaluated.

RESULTS:

Mean surrogate growth duration was 34.8 days. Treated BON-1 surrogates exhibited less proliferation (1.2 vs. 1.9-fold) and higher apoptosis (1.5 vs. 1.1-fold) than controls, while treated patient-derived NET bioreactors exhibited higher degrees of apoptosis (13 vs. 9-fold) and necrosis (2.5 vs. 1.6-fold).

CONCLUSION:

Patient-derived NET surrogates can be reliably cultured within the bioreactor. This model can be used to evaluate the efficacy of antibody-guided chemotherapy ex vivo and may be useful for predicting clinical responses.

INTRODUCTION:

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that originate in a diverse array of anatomical locations and have widely variable clinical presentations. With their incidence and prevalence steadily on the rise, they are the second most prevalent gastrointestinal malignancy, second only to colorectal cancer (1). While a small number of systemic therapies do exist relative to other malignancies, including everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor), sunitinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor), and traditional chemotherapeutics, these interventions have widely variable response rates and can themselves have debilitating side effects (2–6).

Over recent years, efforts to improve the efficacy and tolerability of systemic therapies for NETs have led to the development of NET-targeted therapeutic agents. As many well-differentiated NETs have been shown to overexpress somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), particularly SSTR2 and SSTR5, a number of advances in NET treatment and detection have targeted the SSTRs. Somatostatin (SST) analogues such as octreotide have become the first-line therapy for well-differentiated GEP-NETs, while peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) such as 177Lutetium DOTATATE therapy, and SSTR scintigraphy (68Gallium-DOTATOC and 68Gallium-DOTATATE) have proven to have valuable theranostic applications(7). The success of these tumor-targeted modalities indicates a promising area for the development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), which allow pharmacologic agents to be delivered specifically to neoplasms expressing the target epitopes. Hence, ADCs permit lower minimum effective doses of otherwise unacceptably cytotoxic compounds to be administered, improving their therapeutic indices while minimizing side effects (8).

A further challenge to improving NET therapy exists in the relative dearth of preclinical models for predicting patients’ individual clinical responses to these systemic therapies. As cultivating primary cultures has proven nearly impossible for NETs, few human-derived NET cell lines exist; and establishing patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models for NETs has proven difficult (9, 10). This study proposes the use of a previously characterized 3D flow-perfusion bioreactor system as an ex vivo model for evaluating the response of human NETs to potential therapeutics, allowing patients’ therapy to be personalized(11). To illustrate the utility of this system, an ADC comprised of a proprietary antibody to SSTR2 covalently linked to Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), a highly cytotoxic tubulin polymerization inhibitor derived from the mollusk Dolabella auricularia, was evaluated for the treatment of human NETs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Surrogate preparation and culture –

Primary human NETs were obtained after approval by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board for Human Use (IRB) and in accordance with all IRB and institutional protocols. Following resection, sterile tumor specimens were stored in 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and placed on ice for transport to the UAB Surgical Pathology Department. After confirmation by a surgical pathologist that specimen margins were free of tumor and that sufficient tissue was first available for all clinical purposes, tumor specimens were transported on ice to the lab for processing. Human pancreatic NET (pNET) xenografts (BON-1) were obtained by injecting BON-1 cells subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice and allowing them to grow for 5 weeks before excision. Xenografts and primary human pancreatic NE tissues were passed through a tissue dissociation sieve (Sigma Aldrich, 280 μm pore size) and the cellular components admixed with Bovine Type 1 collagen (Advanced Biomatrix), growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning), 10x Dubelco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning), and 1N NaOH. This mixture was then injected into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) bioreactor perforated by two Teflon coated wires located within an upstream wire-guide to facilitate the formation of perfusion channels. Following polymerization of the tumor surrogate volume, the wires were removed, generating two patent channels through the surrogate matrix. The bioreactors were then connected to a micro-peristaltic pump and a media reservoir via peroxide-cured silicone tubing (Cole Parmer) and continuously perfused with 15 mL of growth medium comprised of Phenol Red-Free DMEM/F12 (Corning), 10% FBS (Atlas Biologicals), Penicillin/Streptomycin (MP Biologics), and 3% dextran (Sigma Aldrich) during incubation (37 ° C, 5% CO2), with medium changed every 3 days unless otherwise stated. Surrogate endpoints were defined by physical/mechanical compromise or the absence of detectable cellular activity as determined by fluorophore uptake & retention.

PET/CT mice imaging –

Immunocompromised male Nu/Nu mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were subcutaneously injected with BON-1 cells and xenografts developed to a palpable size in three weeks. Mice were injected with 100μL of 150–160 μCi of 68Gallium-DOTATATE via I.V. injection and images were collected 1h and 2h after injection. CT images were collected for 100s after the PET images. The images were reconstructed using commercially available algorithms.

Proliferation, apoptosis, and necrosis assays –

Cell viability and proliferation were evaluated using IR-783 as previously described(11). Apoptosis and Necrosis were evaluated using the Realtime-Glo Annexin V Apoptosis and Necrosis Assay (Promega). A 20 μM solution of IR-783 was prepared by dilution in phenol red-free DMEM/F12, and the Realtime-Glo Annexin V Apoptosis and Necrosis reagents added to this mixture to 1x concentration per the manufacturer’s protocol (12). This mixture was injected into the perfusion channels and incubated statically for 15 minutes (37 ° C, 5% CO2). After incubation, surrogates were perfused for 60 minutes before imaging in an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS Lumina, Perkin Elmer). Optimized excitation lamp and filter cube settings were used to detect IR-783 (Ex: 780/Em: 845), as well as the Realtime-Glo Annexin V Necrosis reagent (Ex: 480/Em: 520). Surrogates were incubated as described(11) before each imaging session over the duration of bioreactor growth. Regions of interest were drawn around surrogates to measure radiant efficiency (fluorescence) and photon emission (bioluminescence).

Histologic analysis –

Specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and processed for immunohistochemical staining by the UAB Research Pathology Core. Slides were rehydrated using xylene and ethanol. Antigen retrieval was accomplished by immersing slides in citrate buffer and placing them in a pressure cooker for ten minutes. Slides purposed for assessing the retention of NETs in the bioreactors were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. SSTR2 was detected using an anti-SSTR2 antibody (Santa Cruz SSTR2 Antibody (A-8): sc-365502) at a 1:200 dilution overnight at 4°C and an anti-rabbit biotin labeled secondary antibody (Pierce goat anti-rabbit IgG, #31820). Slides were then stained with DAB chromogen (Dako Liquid DAB+ substrate K3468) and counter stained with hematoxylin.

Statistical analyses –

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics v. 25. Descriptive statistics were summarized using percentages and frequencies for categorical data and means ± standard deviations for continuous data. Data were normally distributed unless otherwise noted. Sample means for growth duration were compared via either two-way independent-samples t-test or one-way ANOVA where appropriate. Equality of variance was evaluated using Levene’s test. Pearson’s correlations were used to evaluate the relationship of growth to age and preoperative chromogranin A levels.

RESULTS

Growth of Human NET Surrogates –

27 Human tumor specimens were cultivated as tumor surrogates, including 20 GEP-NETs, 2 medullary thyroid carcinomas (MTC), 1 pulmonary carcinoid tumor, 1 thyroid follicular Hürthle cell carcinoma, and 2 paragangliomas (Table I). Of these specimens, 31% were derived from metastatic tissue. As determined by IR-783 fluorescence upon IVIS imaging, the mean duration of growth of all specimens was 34.81 ± 17.8 days (Fig. 1). The mean duration of GEP-NET growth was 35 ± 19.4 days (n=21), while the mean durations of paraganglioma (n=2) and MTC (n=2) growth were 18.5 and 48, respectively. The durations of growth of the pulmonary NET (n=1) and Hürthle cell carcinoma were 31 days and 55 days, respectively. Of the 10 patients that underwent preoperative SSTR scintigraphy, all were read as positive in the location from which the specimen was resected. There was no significant difference in the duration of growth of surrogates by tumor grade (p=0.41), sex (p= 0.64), ethnicity (p= 0.86), Ki-67 index (p= 0.85), or the metastatic nature of the specimen (p= 0.92); nor did growth correlate with patients’ age. Notably, the distribution of preoperative serum chromogranin A values was positively skewed, hence a valid correlation to growth duration could not be performed.

Table I.

Characteristics of patients and tumor specimens

| Age (N=27)* | Percent (frequency) | Mean Growth Duration (days) |

|---|---|---|

| 53.2 ± 15.5 | ||

| Sex (N=27) | ||

| F | 37.0 (10) | 34.3 |

| M | 35.1 | |

| Ethnicity (N=27) | ||

| African-American | 25.9 (7) | 36.8 |

| Asian | 7.4 (2) | 48 |

| Hispanic | 3.7 (1) | 30 |

| White | 63.0 (17) | 32.7 |

| Diagnostic Pathology (N = 27) | ||

| GEP-NET | 77.8 (21) | 34.3 |

| Paraganglioma | 7.4 (2) | 18.5 |

| Pulmonary NET | 3.7 (1) | 31 |

| Medullary Thyroid Cancer | 7.4 (2) | 48 |

| Hürthle Cell Carcinoma | 3.7 (3) | 55 |

| Site of Sample Acquisition (N=27) | ||

| GI Metastasis | 14.8 (4) | 34.3 |

| GI/Pancreatic | 59.3 (16) | 35.3 |

| Lung | 3.7 (1) | 31 |

| Retroperitoneum | 11.1 (3) | 24 |

| Thyroid | 11.1 (3) | 50.3 |

| Tumor Grade (N=20) | ||

| 1 | 33.3 (9) | 31.1 |

| 2 | 37 (10) | 37.1 |

| 3 | 3.7 (1) | 50 |

| SSTR-based Imaging (N=27) | ||

| + | 37 (10) | 34.1 |

| None | 63 (17) | 35.2 |

| Ki-67 index (N=18) | ||

| < 3% | 38.9 (7) | 35.3 |

| 3–20% | 38.9 (7) | 32.9 |

| > 20% | 22.2 (4) | 44.5 |

| Serum Chromogranin A (N=15)* | ||

| 112.4 ± 101.5 ng/mL (Normal ≤15) |

Continuous values are summarized as mean ± SD

Figure 1).

Distribution curve depicting the duration of human tumor surrogate growth within the bioreactor system.

Treatment of a Human Cell Line Xenograft Surrogate –

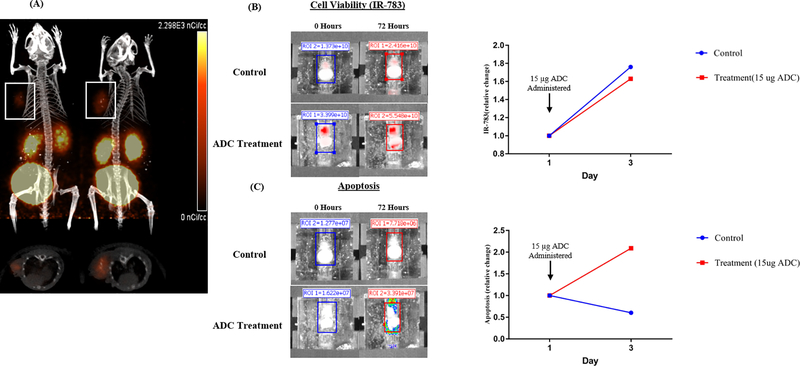

A mouse xenograft comprised of BON-1 cells (a human pNET cell line derived from a lymph node metastasis) was processed and cultivated as two separate tumor surrogates (Fig. 2). To confirm expression of SSTR2 in subcutaneous BON-1 xenografts, scintigraphy with 68Gallium-DOTATATE and PET/CT was performed (Fig. 2A). Surrogates originating from these xenografts were treated with 15 ug of ADC or DMSO as control. Compared to control at 72 hours post-treatment, the surrogate treated with ADC exhibited no effect on proliferation as determined by IR-783 (1.6-fold, 1.7-fold increase) but a much higher relative degree of apoptosis (2.1-fold, 0.6-fold), respectively.

Figure 2).

Pancreatic NET (BON-1) cells were injected subcutaneously into Nu/Nu mice and grown for 5 weeks. (A) PET/CT images of mice were acquired 1 and 2 hours after injection with [68Ga]-DOTATATE to confirm the expression of SSTR2 in subcutaneous BON-1 mouse xenografts (white boxes). These xenografts were then excised, processed, and implanted into two separate bioreactors. The tumor surrogates were imaged at baseline and after 72 hours of culture following incubation with (B) 20 uM IR-783 and (C) the Promega Realtime-Glo Annexin V Apoptosis reagent. The treatment bioreactor was exposed to 15 μg of ADC after imaging on day 0.

Treatment of Primary Human GEP-NET Surrogates –

A primary human pNET was resected, and a 350 mg portion of the specimen (Fig. 3A) was processed as described in the methods and implanted into two separate bioreactors. Expression of SSTR2 was confirmed via immunohistological staining of the original specimen (Fig. 3B). After 12 days of growth, each surrogate was propagated into two separate bioreactors for a total of four tumor surrogates. Baseline measurements of proliferation (Fig. 3C), apoptosis (Fig. 3D), and necrosis (Fig. 3E) were obtained. Two surrogates were then treated with 15 ug of ADC, and two with DMSO as control. On day 3, growth media was changed and surrogates re-treated following imaging. Measurements were acquired at 24-hour intervals over the course of five days and compared to measurements acquired at baseline to determine the relative degrees of change in each parameter by surrogate. Compared to controls, surrogates treated with ADC exhibited higher degrees of apoptosis (13.3-fold vs. 9.3-fold) and necrosis (2.5-fold vs. 1.6-fold). Interestingly, treated surrogates exhibited similar degrees of proliferation to controls (3-fold vs. 2.7-fold) However, due to the small sample size did not reach statistical significance, as determined by an independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test (p = 0.207).

Figure 3).

A resected primary human pNET (A) was processed and implanted into bioreactors. Sections of this specimen stained positively for SSTR2 on histopathological examination (B). After 12 days of growth, surrogates were propagated to yield four separate tumor surrogates. Two surrogates were used as controls, while two surrogates were treated with 15 μg of ADC (one bioreactor from each group is pictured). Images of the surrogates were acquired at baseline, and at 24-hour intervals for five days in an IVIS after daily incubation with 20 μM IR-783 (B), and the Promega Realtime-Glo Annexin V Apoptosis (C) and Necrosis (D) reagent.

Assessment of NET retention in the bioreactor system

A primary human pNET was resected, and a 350 mg portion of the specimen (Fig. 4) was processed as described in the methods and implanted into three separate bioreactors. A portion of the original tumor and one surrogate were immediately fixed and embedded in paraffin. The two remaining tumor surrogates were cultured for 3 and 9 days respectively before being fixed and embedded in paraffin. All paraffin specimens were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before imaging of representative sections. These sections illustrated the maintenance of pNET cells within the bioreactor system, as well as similar morphologic qualities to the original tumor.

Figure 4).

Assessment of NET retention. Histologic sections of surrogates derived from a primary human pNET show characteristic epithelial clustering morphology of pNETs and increasing pNET cell density from 0 to 9 days.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we have depicted the ability to cultivate a widely variable array of primary human NET cells including GEP-NETs in an ex vivo model for as many as 83 days. Further, we illustrated that an expected cytotoxic response to an SSTR2-targeted anti-mitotic agent predicated upon SSTR2 expression in both human cell line xenograft tissue and primary human NET tissue can be produced using tumor surrogates within this model. This introduces the possibility that tumor surrogates in flow-perfusion bioreactor models can be employed to evaluate NETs for a clinical response to targeted therapeutics ex vivo using primary human NET tissue.

The promising utility of targeted therapeutics for NETs has been illustrated by the early successes in their use (13, 14). Specifically, targeting tumor-specific epitopes with ADCs has proven to be a powerful therapeutic strategy (15, 16). ADCs integrate the advantages of monoclonal antibodies capable of specifically binding tumor associated surface receptors, with the high cytotoxic potential of small molecule chemotherapeutics. In this study, we used the previously described tubulin polymerization inhibitor MMAE (17, 18) as a potent cytotoxic payload conjugated with anti-SSTR2 antibody to kill pNET cells.

While tumor surrogates grown in this model allow for greater success in cultivating primary human NETs than traditional cell culture or establishing PDX models, they possess a number of distinct advantages and disadvantages. As NETs are characteristically slow-growing, an important utility of the bioreactor system is the ability to detect cytotoxic changes within it. Tumor subtypes with the slowest proliferation rates in vivo may also proliferate slowly in the bioreactor- but the capability of culturing tumor surrogates to ~30 days permits ample time to conduct therapeutic trials similar to those performed herein. Their relatively low throughput does not allow for studies with high statistical power to be conducted on specimens derived from a single patient, due to the amount of tissue required. This is as opposed to higher throughput models such as organoids which, if viable for NETs, would allow for more high-powered screening on a broader scale of therapeutics(19, 20). However, an advantage of the bioreactor model lies in the comparatively high rate of success with which primary human NETs can be cultured, as well as the heterogeneity of the cell populations that comprise the surrogates. Whereas current organoid models for NETs lack important components of the tumor stroma, the absence of a cell-sorting process during implantation allows NET cells, endothelia, fibroblasts, immune cells, and other stroma that contribute to the tumor microenvironment to be implanted into the surrogate and arranged into a perfused 3D architecture(21, 22). Previous work with this model and unpublished observations support the retention of this diverse cell population, potentially conferring a phenotype more similar to that expressed by the tumors in vivo than other culture methods, theoretically allowing them to respond to candidate therapeutics in a more physiologically relevant manner (11).

A key limitation of this study is the low throughput of tumor surrogates upon which the ADC was tested, and performance of only the human pNET experiment in duplicate. A further limitation lies in the unclear accuracy of IR-783 uptake as a measurement of tumor viability and proliferation in the context of drug therapy. While it is normally internalized into cells by members of the organic anion transporter (OAT) superfamily of proteins, unpublished observations suggest that increased membrane permeabilization due to cellular necrosis during cytotoxic drug therapy may confound the results of these measurements, thereby limiting their utility to studies performed in the absence of therapeutic agents. For example, while administration of the ADC resulted in increased apoptosis and necrosis at day 6 in the human tumor depicted in Figure 2, the proliferation measure of the treated bioreactors increased during the trial. We hypothesize that the high rate of necrosis in the treated bioreactors and resultant increase in membrane permeability allowed the infrared dye used to assess proliferation (IR-783) to enter the cells through means other than the organic anion transporter. Upon necrotic death, the cells would no longer be capable of excreting the dye through OAT and other efflux pumps for lack of ATP. In contrast, there was not a high baseline rate of apoptosis in the bioreactors containing BON-1 xenograft cells. This highlights a key issue in studying NETs; the currently available cell lines harbor a number of mutations absent in primary tumors that have facilitated their adaptation to growing in vitro. A number of these mutations have been identified by Vandamme et al. and Hofving et al. (23, 24) in GEP-NET cell lines. For example, the BON-1 cell line isolated by Evers et al. has been in culture for over 20 years and possesses a homozygous loss of CDKN2A and CDKN2B, which are not characteristic mutations in NETs(25). TP53, encoding a tumor suppressor and key regulator of DNA repair and apoptosis, is usually unaffected in GEP-NETs; however, it was found to be bi-allelically inactivated in BON-1 as well as QGP-1, another pNET cell line. The genome of BON-1 contains a homozygous stop-loss mutation, while the genome of QGP-1 has undergone a frameshift deletion of the gene. Alternatively, these cell lines lack mutations in DAXX or MEN1, which are common in NETs. These uncharacteristic genomic changes may contribute to lower levels of baseline apoptosis in culture when observing cell line xenografts as compared to primary human tumors. They may also contribute to the difficulty in culturing these primary tumors ex vivo. Hence, while this model allows human tumors to be cultured ex vivo for a longer duration than is observed with traditional culture methods, naturally occurring degrees of apoptosis and necrosis will likely be present within the system in the absence of investigator manipulation.

While these tumor surrogates cannot replace clinical trials for determining pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, or side effects, this model is ideal for the evaluation of targeted therapeutics or FDA-approved pharmacologic agents’ efficacies. Further, they represent a tool that can be used to inform and appropriately alter clinical decision making during a patient’s treatment course to make it optimally effective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Kayla Goliwas for her invaluable assistance during the study.

GRANT SUPPORT

Research reported in this publication was supported by the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences TL1 Pre-Doctoral Training Grant under award number TL1TR001418 and North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) Basic/Translational Science Investigator (BTSI) award.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Brendon Herring, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Jason Whitt, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Tolulope Aweda, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Jianfa Ou, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Rachael Guenter, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Suzanne Lapi, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Joel Berry, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Herbert Chen, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Xiaoguang Liu, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

J. Bart Rose, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

Renata Jaskula-Sztul, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, Birmingham, AL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA oncology. 2017;3(10):1335–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee L, Ito T, Jensen RT. Everolimus in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: efficacy, side-effects, resistance, and factors affecting its place in the treatment sequence. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2018;19(8):909–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiedmann MW, Mössner J. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib in patients with unresectable pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical Medicine Insights Oncology. 2012;6:381–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, Peeters M, Hörsch D, Winkler RE, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. The Lancet. 2011;378(9808):2005–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavel M, O”Toole D, Costa F, Capdevila J, Gross D, Kianmanesh R, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Distant Metastatic Disease of Intestinal, Pancreatic, Bronchial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of Unknown Primary Site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):172–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster DS, Jensen R, Norton JA. Management of Liver Neuroendocrine Tumors in 2018. JAMA Oncology. 2018;4(11):1605–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Öberg KE, Reubi JC, Kwekkeboom DJ, Krenning EP. Role of Somatostatins in Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Development and Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(3):742–53.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaïa N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2017;16:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Z, Zhang L, Serra S, Law C, Wei A, Stockley TL, et al. Establishment and Characterization of a Human Neuroendocrine Tumor Xenograft. Endocrine Pathology. 2016;27(2):97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Shimon I, Rubinfeld H. The Role of Cell Lines in the Study of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96(3):173–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goliwas KF, Richter JR, Pruitt HC, Araysi LM, Anderson NR, Samant RS, et al. Methods to Evaluate Cell Growth, Viability, and Response to Treatment in a Tissue Engineered Breast Cancer Model. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):14167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupcho K, Shultz J, Hurst R, Hartnett J, Zhou W, Machleidt T, et al. A real-time, bioluminescent annexin V assay for the assessment of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, et al. Phase 3 Trial of (177)Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;376(2):125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saunders LR, Bankovich AJ, Anderson WC, Aujay MA, Bheddah S, Black K, et al. A DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor-initiating cells in vivo. Science translational medicine. 2015;7(302):302ra136–302ra136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Wang M, Yao X, Luo W, Qu Y, Yu D, et al. Development of a Novel EGFR-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate for Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. Targeted Oncology. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Amico L, Menzel U, Prummer M, Müller P, Buchi M, Kashyap A, et al. A novel anti-HER2 anthracycline-based antibody-drug conjugate induces adaptive anti-tumor immunity and potentiates PD-1 blockade in breast cancer. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer. 2019;7(1):16-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao Y, Wang Y, Zhou S, Lai Q, Lu Y, Liu Y, et al. Preparation and anti-cancer evaluation of promiximab-MMAE, an anti-CD56 antibody drug conjugate, in small cell lung cancer cell line xenograft models AU - Yu, Lin. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2018;26(10):905–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham D, Parajuli KR, Zhang C, Wang G, Mei J, Zhang Q, et al. Monomethyl Auristatin E Phosphate Inhibits Human Prostate Cancer Growth. The Prostate. 2016;76(15):1420–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crespo M, Vilar E, Tsai S-Y, Chang K, Amin S, Srinivasan T, et al. Colonic organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for modeling colorectal cancer and drug testing. Nature medicine. 2017;23(7):878–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broutier L, Mastrogiovanni G, Verstegen MM, Francies HE, Gavarró LM, Bradshaw CR, et al. Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening. Nature medicine. 2017;23(12):1424–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki K, Fujii M, Sato T. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: genes, therapies and models. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2018;11(2):dmm029595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO reports. 2014;15(12):1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandamme T, Beyens M, Peeters M, Van Camp G, de Beeck KO. Next generation exome sequencing of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell lines BON-1 and QGP-1 reveals different lineages. Cancer Genetics. 2015;208(10):523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofving T, Arvidsson Y, Almobarak B, Inge L, Pfragner R, Persson M, et al. The neuroendocrine phenotype, genomic profile and therapeutic sensitivity of GEPNET cell lines. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2018;25(3):367–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vijayvergia N, Boland PM, Handorf E, Gustafson KS, Gong Y, Cooper HS, et al. Molecular profiling of neuroendocrine malignancies to identify prognostic and therapeutic markers: a Fox Chase Cancer Center Pilot Study. British Journal Of Cancer. 2016;115:564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]