Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: caregivers, critical illness, intensive care unit follow-up clinics, peer support, postintensive care syndrome

Abstract

Objectives:

To understand the unmet needs of caregivers of ICU survivors, how they accessed support post ICU, and the key components of beneficial ICU recovery support systems as identified from a caregiver perspective.

Design:

International, qualitative study.

Subjects:

We conducted 20 semistructured interviews with a diverse group of caregivers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, 11 of whom had interacted with an ICU recovery program.

Setting:

Seven hospitals in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Content analysis was used to explore prevalent themes related to unmet needs, as well as perceived strategies to improve ICU outcomes. Post-ICU care was perceived to be generally inadequate. Desired caregiver support fell into two main categories: practical support and emotional support. Successful care delivery initiatives included structured programs, such as post discharge telephone calls, home health programs, post-ICU clinics, and peer support groups, and standing information resources, such as written educational materials and online resources.

Conclusions:

This qualitative, multicenter, international study of caregivers of critical illness survivors identified consistently unmet needs, means by which caregivers accessed support post ICU, and several care mechanisms identified by caregivers as supporting optimal ICU recovery.

Survivors of critical illness face a prolonged and resource intensive recovery. Much of the care required to recover from critical illness is provided by informal caregivers, who may experience stress, depression, grief, role change, socioeconomic impacts, and even increased mortality as a result (1–4). Despite their import, there are limited qualitative data about the unique challenges and potential solutions confronting the caregivers of ICU survivors. Where guidelines exist, the focus has been on intra-ICU interventions (5–7). Recent studies show that intentional support for caregivers is lacking, especially in the post-ICU period (2–4, 8).

Developing specific interventions to optimize post-ICU recovery requires better understanding of these challenges and the ways in which caregivers access support. To inform care redesign, we sought to elucidate caregiver needs in the critical illness recovery period, as well as components of post-ICU programs that caregivers found beneficial.

METHODS

Setting and Ethical Approval

The study design and protocol were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board (U.S. coordinating site), the Western Health Low Risk Human Research Ethics Panel (Australia), and the South West (Cornwall and Plymouth) Research Ethics Committee (United Kingdom). We used phenomenological qualitative inquiry, namely semistructured interviews, to investigate caregiver experiences.

Participants, Sampling, and Recruitment

THRIVE was established by SCCM in 2015 to improve patient and family outcomes after critical illness (9, 10). Peer support and post-ICU clinic collaborative sites were recruited internationally through 2019. Caregivers were recruited by clinicians facilitating THRIVE program activities or via patients participating in THRIVE programs. No contacted caregivers declined to participate. Additional participants, including those who did not interact with THRIVE programs, were recruited via social media and online. We recruited caregivers not taking part in a THRIVE program to fully understand the complexity of ICU recovery from a caregiver perspective. This allowed better understanding of the context and benefits of ICU recovery services for those who received them. We also sought to understand different time points in the recovery trajectory and recruited caregivers at various timepoints in recovery. Stratified purposive sampling was employed to promote sociodemographic and geographic diversity.

Caregivers older than 18 years who provided informal caregiving for someone who survived critical illness and had adequate English language to participate were included. No exclusions were applied to caregivers.

Data Collection

A semistructured interview schedule with prompting questions guided the data collection (Supplementary File 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A610). The research group (C.M.S., L.M.B., J.M., K.J.H.) generated interview questions and prompts via iterative discussion, following a review of the literature. These were then externally reviewed by an expert qualitative researcher independent of the research team, as well as caregiver representatives. In the event that an interviewer was known to a participant because of their role in clinical care, another interviewer unknown to the caregiver conducted the interview. Interviews were conducted via telephone. Data were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis and Rigor

The study design used thematic content analysis as described by Miles and Huberman (11). Five key steps were included in the data analysis process (Supplementary File 2, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A611). First, the analysis team (C.M.S., L.M.B., J.M., K.J.H.) undertook preliminary sweeps of the data to familiarize themselves with the content and develop initial coding. No preset or a priori codes were used. Second, the team built two coding frameworks, one around unmet needs experienced by caregivers, and the second around ideal components of post-ICU support. Third, the initial coding was grouped under key themes and iteratively checked across interview transcripts. Fourth, three researchers (C.M.S., J.M., K.J.H.) defined and classified the key themes. Finally, the primary analysis team reviewed the conceptual models created and extracted quotations to support the thematic analysis. Researchers (C.M.S., J.M., K.J.H.) met monthly to discuss study conduct and analysis. The team regularly discussed data saturation; consensus was met that data saturation regarding caregiver experience had been achieved despite geographic variability by across international sites. An audit trail was uploaded onto a shared, secured site for all researchers involved in the analysis. This study was reported using the Consolidated Reporting of Qualitative Research checklist (12).

RESULTS

Demographics

Twenty caregivers were interviewed: 16 (80%) from the United States, two (10%) from Australia, and two (10%) from the United Kingdom, representing seven hospital sites. Approximately half (55%) participated in some type of ICU recovery program; nine (45%) did not participate in any program. Interviews took place between July 2018 and February 2019. Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A description of the programs delivered at these sites is in Supplementary File 3 (http://links.lww.com/CCX/A612).

TABLE 1.

Caregiver Characteristics

| Characteristics | n = 20 |

|---|---|

| Age, yr, median (interquartile range) | 52 (46–67) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 3 (15) |

| Female | 17 (85) |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | |

| Spouse/significant other | 10 (50) |

| Parent | 5 (25) |

| Sibling | 3 (15) |

| Child | 2 (10) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| United States | 16 (80) |

| United Kingdom | 2 (10) |

| Australian | 2 (10) |

| Participated in an ICU recovery program, n (%) | |

| Yes | 11 (55) |

| No | 9 (45) |

| Type of recovery program useda, n | |

| Peer support group | 7 |

| ICU follow-up clinic | 6 |

| None | 9 |

aTwo participants used both peer support and ICU follow-up clinic services.

Major Themes

Two major themes evolved from the data: 1) unmet needs in the caregiving role and 2) effective strategies to improve ICU aftercare.

Unmet Needs in the Caregiving Role.

Unmet needs of caregivers were divided into practical and emotional needs. The practical challenges of physical recovery were universally acknowledged. Lack of support during a high stress, high need time was a major unmet need. This meant that caregivers needed to extend their own physical and emotional resources to provide support to the patient:

1: …it progressed from physical challenges, so anything that he couldn’t do physically became my responsibility… then to more emotional challenge. So it kind of went through these phases of physical, emotional, spiritual challenges where it progressed from day one it being more of like a ‘how far can you walk’ kind of challenge, to him being closed off emotionally...

The paucity of information about post-ICU recovery both in the ICU and at hospital discharge was a challenge identified by almost all participants. Caregivers learned information as they moved through the recovery continuum but indicated a desire for more information earlier:

2: I’m getting a better picture of the fact that being in the ICU… causes that delirium… I wish I had had some awareness of all those things as she was in there or what to expect coming home, so I could be more nurturing and provide more support.

Written information was one of the most commonly identified needs. Caregivers described having trouble synthesizing and remembering information conveyed verbally. This was compounded by profound emotional stress, complex new information, and multiple team members attempting to provide information:

3: Because so much information is coming in, like you’re trying to deal with your own feelings and you’re trying to deal with the person that’s sick, and then you’re trying to deal with your family and your children, and then someone comes and tells you that. “Yeah, mate, just give it to me, put it in my bag, [I] might lose it.”

Participants expressed bewilderment that there were no structured care pathways in place to support patients and caregivers after an ICU stay. This gap in care, exacerbated by a paucity of information and communication about the recovery trajectory, was perceived as a shortcoming of the medical system even where participants were otherwise satisfied with their care:

1: There was no support given or offered to us from the hospital… like no information as far as how this whole being sedated for this period, you know, what it does… It’s an amazing hospital and I was just surprised by the lack of support we got in that manner.

Fragmentation of care in the postdischarge period added to the burden for caregivers, who were forced into performing advocacy and care coordination, often with little education, knowledge, or skill. Transitions of care, including from ICU to ward, from ward to rehabilitation facility, and from the inpatient setting to home, were especially fraught, with caregivers struggling with the change in their own role from family member to primary caregiver.

4: Well, where do we go from here? Who are we seeing next? When’s the next appointment? Is anyone going to ring us? Is anyone going to follow us up?

Additionally, they had to recognize that clinicians outside of their ICU team were unfamiliar with post-ICU syndrome:

4: Yes, his general practitioner knew about the situation, but they sort of don’t know about the actual situation of what [the patient] was actually in. I don’t think anybody knows really what he was in – only the ICU people and the rehab people.

Identifying clinicians who were equipped to handle post-ICU complications was also invoked as a barrier to optimal care:

5: Who do you talk to about it? Who’s going to treat you? Like [the patient’s] primary care doctor blew him off. She had not a clue. And he was just wanting help so badly.

Families in rural areas found the lack of access to knowledgeable specialist care particularly challenging, describing isolation in their experience at home, and having to leave their usual support networks in order to access required healthcare:

5: It was hard for him to have anybody understand what he was going through… I mean around here you’re not going to find any medical help that’s going to be decent… it was hard finding any professionals around here that know how to deal with these things.

As a result, desire for access back to the care team that was knowledgeable about post-ICU issues in general, and the patient’s specific case, was a recurrent theme:

3: You’ve been there for so long and the hospital becomes your second home… and then when you go home and that’s cut off there, it’s like, “Oh.” Then when you get this offer [to attend peer support] … there’s like a reconnection… and it makes the transition a lot easier.

Although practical challenges were present throughout all interviews, the emotional challenges of being a caregiver for an ICU survivor were perceived as even less supported by available infrastructure. Participants were required to change their familial role in order to provide care. Often this changed the family unit dynamic, creating tension:

6: When you’re a caregiver, your role changes from spouse to caregiver… you’re doing things you normally didn’t do, or weren’t required to do. And when the patient starts getting better, there’s a little bit of conflict there... [we] were never a conflicted family, and we have conflict now.

In some cases (e.g., online support groups), no part of the intervention appeared to be specifically tailored to caregivers and was thus found not to be beneficial:

8: There was one I tried to join but they had a lot of questions. It felt almost intrusive from the level of questioning there was… almost like I had to prove myself that I had had this experience…. I don’t feel like it’s really part of what my role should be to be adding anything to the conversation. So, no, I’ve not participated in a meaningful way.

Access to a knowledgeable clinical team and information was universally desired, but many caregivers acknowledged that the post-hospital period imposes heavy demand on both patient and caregiver, requiring flexibility and individualization. The inpatient stay was described as a potentially underused time for intervention:

1: I mean, I think [an ICU recovery program] should be introduced in the hospital, especially involved in the discharge teaching, and even some sort of maybe follow up by a social worker or whatever, maybe checking in to remind you that these classes or groups or whatever are available to you. I think when you’re discharged and you get home, you’re so focused on trying to get back to normal like that immediately upon discharge, you’re not thinking about it. So it’s a month or two down the road when everything kind of settles a little bit.

Strategies Perceived Effective in Improving Post-ICU Support.

Despite these challenges, caregivers identified several useful support mechanisms. Among caregivers who had participated in a post-ICU program, these included access to the care team after discharge, post-ICU clinic visits, peer support, and online resources. When asked to describe ways of improving post-ICU care for patients and caregivers, caregivers who had not been exposed to post-ICU services described known models of support, including post-ICU clinics, peer support, and ICU diaries:

7: If somehow there was a, I don’t know if you say a daily diary, or some time where there was some personal intervention when people were touching his body or something like that, they could put, ‘Okay, on July 24th we had to put a catheter or we had to insert an additional tube down your throat or we had to do this or that,’ so that at some point he doesn’t think that he was sexually abused or drowning, there is an explanation for it.

A summary, alongside representative quotes of strategies with the potential to ameliorate unmet needs, is shown in Table 2 (practical unmet needs) and Table 3 (emotional unmet needs). Where available, ICU aftercare services were viewed favorably. Caregivers expressed surprise and dismay that these services, which they found invaluable, were not widely available:

TABLE 2.

Themes and Representative Quotes of Strategies to Promote Practical Support for Caregivers

| Caregiver Need Identified | Proposed Delivery for Support Mechanism | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Physical space | Inpatient space for caregivers | 9: “They were very good to us, we did have a place where we could shower and we could lay down and sleep. And they kept us in blankets and pillows and were very good to us.” |

| Peer support for caregivers | In-ICU and post-ICU support groups for caregivers | 10: “So I think that would have definitely helped… something in the hospital, in the ICU floor or in a chapel…The families that are going through this, having a place to go and even if they don’t know each other, get a little support: ‘This is tough, this is really tough.’ ‘Yeah, it is. How are you getting through?’” 11: “It’s like we gotta survive the chaos before we can really start sharing the story… I would definitely say offer telephone or internet-based sort of counselling or support because actually leaving the house when you’re dealing with somebody with a critical illness sometimes can be impossible, or you’re just exhausted and can’t get to another location.” |

| Educational materials/information | Structured education programs | 12: “So definitely, for me, links and information… an app on my phone would be great.” |

| Expectation management about recovery | Anticipatory guidance | 2: “I don’t know, would a family meeting have been more appropriate, with her care team saying, ‘Okay, this is what you might experience going home, and here’s a number to call if you do have these reactions’? It’s just kinda weird that you go through all this stuff, and then you just get sent home.” |

| Support immediately after discharge | Informal/formal “check in” | 1: “A phone call is a good starting point, because at least it kind of keeps that line of communication open.” |

| Identifying ICU-related needs or consequences in the outpatient setting | Individualized post-ICU clinic services for caregivers and access to clinic team or discharge coordinator | 8: “Maybe when [the patient] is visiting her doctors, maybe having me visit with someone at the clinic. Just check in, see how she’s doing, see how I’m doing… So it’s a two for one.” 3: “Like when you come home it’s so scary and you’re so alone, and you need that link and she [discharge coordinator] was that link.” |

| Adaptation | Role change coaching | 13: “Spouses have her role, my role. [She] ends up doing a lot of the meal prep stuff, so when she was incapacitated in the way that she was, it was really difficult for me to figure out okay, how am I gonna eat?” |

| Self-care | Tools for self-care during the patient’s recovery journey | 1: “Being able to implement that self care: you know, if you’re not taking care of yourself there’s no way you can take care of someone else.” |

| Socioeconomic support | Financial and employment counselling/referrals | 2: “Without any kind of follow up support, it’s just maddening. And the financial drain, oh my God. I don’t even… the financial piece of it I’m sure is huge for so many people.” 4: “Financial circumstances, that’s another challenge. You know, he’s out of work, he was a breadwinner and now he’s not… who do we rely on, what do we do?” |

TABLE 3.

Themes and Representative Quotes of Strategies to Promote Emotional Support for Caregivers

| Caregiver Emotional Need Identified | Proposed Delivery for Support Mechanism | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Support reporting role | ICU diary | 14: “I did, on her request, I tried to diary the hospital stay on a calendar. This was post discharge, but my memory was still pretty fresh… as much detail as I could, so I just wrote that down [on a calendar] and gave it to her. She asked for it. She asked to see pictures.” |

| Validation and catharsis | Peer support—connect with others via shared experience of caregiver role | 10: “…somebody for the family to walk alongside, too, that’s been there…at least you know you’re not alone.” 8: “Finding people who I felt like I could talk to was another challenge. We …. kept saying things like ‘we feel like we’re contagious.’ Like if people listen too deeply or too intently to our story, they themselves might become situated in the same place that we were.” |

| Spirituality | Offer spiritual support across the recovery arc | 11: “Prayer. Having some sort of spiritual purpose in what you’re going through and trying to find a similar learning.” |

| Independence from patient | Separate support pathways | 6: “Being able to break away.” |

| Physical space | 12: “I’m still kind of on the payroll, so to speak, trying to get his life back in order… It’s like a second job… You need permission to also take care of yourself.” |

2: She met with her critical care doctor about two, three weeks ago. It was awesome that he did this. He spent about two, three hours with her and went through her chart with her, took her to the ICU, had her meet the nurses that took care of her, showed her her room, helped her understand why she might have had some of these hallucinations…. Yeah, I was amazed that her critical care doctor took this time with her. And you know what? Why should I be amazed by that? That should be part of the process. That should be a mandatory visit.

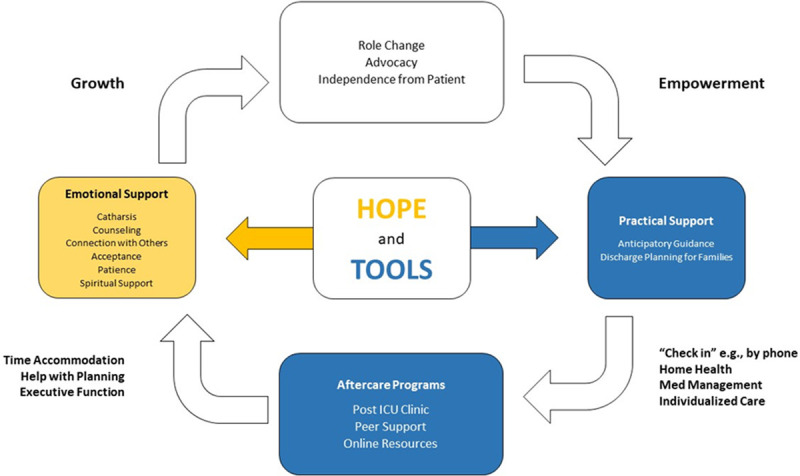

CONCEPTUAL MODEL INTEGRATING PRACTICAL AND EMOTIONAL SUPPORTS FOR CAREGIVERS

The overarching theme of identified needs and beneficial supports was summarized by one respondent as “hope and tools,” underlining the perception that both emotional and practical supports are needed for optimal recovery. We propose a conceptual model of care where these often overlapping requirements are integrated and may be delivered over the arc of the recovery period (Fig. 1). Providing education, anticipatory guidance, written materials, and access to a knowledgeable care team while the patient is still admitted, checking in by phone and connecting patients and caregivers to needed resources after discharge, and repeatedly assessing changing needs over time may allow caregivers to grow into their roles and empower them to get needed care both for the patient and for themselves.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model: integrating approaches to support unmet needs of caregivers of patients recovering from critical illness.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study of caregivers assisting patients in recovery from critical illness revealed unmet needs, as well as proposed mechanisms to improve the emotional and practical aspects of recovery. Although not widely available, ICU recovery programs were perceived to improve care by educating caregivers about expected recovery trajectories, providing access to knowledgeable clinical teams, and encouraging caregivers to develop individualized skills with which to address their own challenges, role changes, and frustrations.

Prior studies on caregivers of ICU survivors have focused on quantifying the psychosocial burden of caregiving (13), but there is little research to inform improvements in care delivery. Where research has focused on caregivers, the perception of insufficient support in the post-ICU period has been previously described. Choi et al (14) identified insufficient time to transition from a visitor role to caregiver role, poor expectation management, and persistent emotional needs as contributors to caregiver burden. To our knowledge, the effects of suboptimal caregiver support on patient outcomes have not been explored. However, caregivers have been identified as key to understanding ICU survivorship in both the clinical and research settings (15).

In addition to medical readiness for discharge, emotional support, psychologic readiness, and adequate information have been identified as conditions required for a successful discharge from inpatient care (16). Failure to meet these needs for patients and families may result in hospital readmission, among other poor outcomes (17). A recent study of ICU survivors suggests a significant number of readmissions are due to psychologic and emotional factors in this population, not just medical factors (18), raising the possibility that bolstering emotional supports for patients and caregivers could impact healthcare utilization.

Caregivers suggest these needed supports could be supplied in a variety of infrastructural forms—phone calls, home health, post-ICU clinic, peer support, online forums—and individualized to maximize impact at necessary time points. There is debate about who should staff these post-ICU care systems desired by patients and caregivers (19–22). Here, caregivers repeatedly invoked the involvement of ICU staff as key to a successful recovery. Recent evidence suggests that engagement by ICU staff may facilitate tangible improvements in the critical care environment (10). Caregivers also identified several inadequate supports already in place, delineating targets for immediate quality improvement.

The strengths of this study include the application of predefined and extensively used methodology. The research was interdisciplinary and international, drawing from experience in the fields of medicine, nursing, and physiotherapy in three countries. This study team sought to capture a wide array of ICU recovery experiences, including from those who did and did not receive ICU follow-up services, improving generalizability.

Recruitment through existing ICU follow-up (THRIVE) programs is a potential limitation, perhaps highlighting the experiences of those who had more help, a source of bias. Additional targeted sampling via social media allowed us to recruit caregivers who had not participated in ICU aftercare services. This may have introduced a different selection bias, as caregivers recruited in this way may have been more engaged than their peers. Alternatively, this method may have enriched our sample by including families who had particularly difficult recovery paths, prompting them to seek additional support online. A majority of participants were women, potentially reflecting that the burden of informal caregiving falls heavily on this population. Notably, 80% of caregivers were in the United States, a limitation given the particularly fragmented healthcare system there. Finally, there may be benefits of the caregiving role; these were not apparent on analysis and may be a result of the sampling strategies employed.

In conclusion, this qualitative study of caregivers of critical illness survivors identified consistently unmet needs that may impact the health of patients and caregivers, as well as a number of care mechanisms identified by caregivers as supporting optimal ICU recovery. Additional studies evaluating the impact of targeted interventions for caregivers on critical illness recovery should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals who collectively contributed to the review of the original grant application: Dr. Daniela Lamas, Ms. Kate Cranwell, Dr. Craig French, and Dr. Carol Hodgson. We would also like to acknowledge the wider THRIVE steering group within the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This does not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. government or Department of Veterans Affairs.

Drs. Haines and McPeake are co-senior authors.

Drs. Sevin, McPeake, Mikkelsen, Iwashyna, and Haines contributed to conception and design. Drs. Sevin, Boehm, McPeake, and Haines contributed to analysis and interpretation. Drs. Sevin, McPeake, and Haines contributed to data extraction and primary analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and revising the article for important intellectual content.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

Supported, in part, by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). The scientific questions, analytic framework, data collection, and analysis were undertaken independently of the funder. SCCM Council reviewed the manuscript prior to finalization.

Drs. Sevin, Boehm, Quasim, Haines, and McPeake received funding from Society of Critical Care Medicineto undertake this work. Dr. Boehm is funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K12 HL137943) as is Dr. Iwashyna (K12 HL138039). Dr. McPeake is funded by a THIS Institute Post-Doctoral Fellowship (PD-2019-02-16). The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haines KJ, Denehy L, Skinner EH, et al. Psychosocial outcomes in informal caregivers of the critically ill: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43:1112–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Major ME, van Nes F, Ramaekers S, et al. Survivors of critical illness and their relatives. A qualitative study on hospital discharge experience. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019; 16:1405–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czerwonka AI, Herridge MS, Chan L, et al. Changing support needs of survivors of complex critical illness and their family caregivers across the care continuum: A qualitative pilot study of towards RECOVER. J Crit Care. 2015; 30:242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ågård AS, Egerod I, Tønnesen E, et al. From spouse to caregiver and back: A grounded theory study of post-intensive care unit spousal caregiving. J Adv Nurs. 2015; 71:1892–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45:103–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, et al. Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: A qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2013; 35:315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings LA, Palimaru A, Corona MG, et al. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Qual Life Res. 2017; 26:685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPeake J, Iwashyna TJ, Boehm LM, et al. Benefits of peer support for intensive care unit survivors: sharing experiences, care debriefing, and altruism. Am J Crit Care. 2021; 30:145–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert E, et al. Enablers and barriers to implementing ICU follow-up clinics and peer support groups following critical illness: The thrive collaboratives. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:1194–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haines KJ, Sevin CM, Hibbert E, et al. Key mechanisms by which post-ICU activities can improve in-ICU care: Results of the international THRIVE collaboratives. Intensive Care Med. 2019; 45:939–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles MB, Michael Huberman A: Qualitative data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007; 19:349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF, et al. Reported burden on informal caregivers of ICU survivors: A literature review. Crit Care. 2016; 20:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi J, Lingler JH, Donahoe MP, et al. Home discharge following critical illness: A qualitative analysis of family caregiver experience. Heart Lung. 2018; 47:401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilcox ME, Ely EW. Challenges in conducting long-term outcomes studies in critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2019; 25:473–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvin EC, Wills T, Coffey A. Readiness for hospital discharge: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2017; 73:2547–2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloom SL, Stollings JL, Kirkpatrick O, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an ICU recovery pilot program for survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:1337–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirshberg EL, Wilson EL, Stanfield V, et al. Impact of critical illness on resource utilization: a comparison of use in the year before and after ICU admission. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:1497–1504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sevin CM, Jackson JC. Post-ICU clinics should be staffed by ICU clinicians. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stollings JL, Bloom SL, Wang L, et al. Critical care pharmacists and medication management in an ICU recovery center. Ann Pharmacother. 2018; 52:713–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eaton TL, McPeake J, Rogan J, et al. Caring for survivors of critical illness: Current practices and the role of the nurse in intensive care unit aftercare. Am J Crit Care. 2019; 28:481–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McPeake J, Boehm LM, Hibbert E, et al. Key Components of ICU Recovery Programs: What Did Patients Report Provided Benefit? Crit Care Explor. 2020; 2:e0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.