Abstract

Background

The occurrence of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) affects the mental health situation of almost everyone, including University students who spent most of their time at home due to the closure of the Universities. Therefore, this study aimed at assessing depression, anxiety, stress and identifying their associated factors among university students in Ethiopia during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We invited students to complete an online survey using Google forms comprising consent, socio-demographic characteristics, and the standard validated depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21) questionnaire. After completion of the survey from June 30 to July 30, 2020, we exported the data into SPSS 22. Both descriptive and analytical statistics were computed. Associated factors were identified using binary logistic regression and variables with a p-value <0.05 were declared as statistically significant factors with the outcome variables.

Results

A total of 423 students completed the online survey. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in this study was 46.3%, 52%, and 28.6%, respectively. In the multivariable model, female sex, poor self-efficacy to prevent COVID-19, those who do not read any material about COVID-19 prevention, lack of access to reading materials about their profession, and lack of access to uninterrupted internet access were significantly associated with depression. Female sex, lower ages, students with non-health-related departments, those who do not think that COVID-19 is preventable, and those who do not read any materials about COVID-19 prevention were significantly associated with anxiety. Whereas, being female, students attending 1st and 2nd years, those who do not think that COVID-19 is preventable, presence of confirmed COVID-19 patient at the town they are living in, and lack of access to reading materials about their profession were significantly associated with stress.

Conclusions

Depression, anxiety, and stress level among University students calls for addressing these problems by controlling the modifiable factors identified and promoting psychological wellbeing of students.

Background

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a viral pandemic that emerged for the first time in Wuhan, China, and spreads all over the world between December 2019 and early 2020 [1]. The virus has resulted in more than 54 million cases and 1.3 million deaths worldwide [2].

Because of the sudden nature of the outbreak and the infectious power of the virus, it will inevitably cause serious threats to people’s physical health and lives. It has also triggered a wide variety of psychological problems, such as panic disorder, anxiety, depression, and stress [1, 3, 4]. Depression, anxiety, and stress affect the outcome of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and obesity [5]. Depression, anxiety and stress can affect every population including students all of which can affect job performance, quality of sleep, routine activities, and productivity of the victims [6].

The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress is high among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic [7]. This number is expected to be higher among University students during the COVID-19 pandemic as they are exposed to excessive working hours, living in a competitive academic environment, and financial problems [8]. According to a study in Canada, the prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress is 39.5%, 23.8% and 80.3%, respectively [9]. The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among European College students was 39.0%, 47.0%, and 35.8%, respectively [10]. In Saudi Arabia, 58.1% of the University’s academic community had anxiety and 50.2% of them had depression [11]. In Pakistan, 57.6% of Medical students had depression, 74% anxiety and 57.7% [12]. Similarly, another study in Pakistan revealed that 48%, 68.54% and 53.2% of students had depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively [13]. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among Malaysian undergraduate students was 30.7%, 55.5%, and 16.6%, respectively [14]. In Ethiopia, according to a study in Addis Ababa medical students, 51.30% of them had depression and 30.10% had anxiety symptoms [15].

Previous studies revealed that internet access [16–18], self-efficacy [19–21], self-rated health [9], age, marital status, and sex of the students were significantly associated with depression [22]. Similarly, age [15, 22–32], year of study, and social support [15], marital status, and sex of the students were significantly associated with anxiety [15, 22]. Academic performance [9], age, marital status [22], and sex [1, 23, 29, 33–42] were determinants of stress. Though COVID-19 may take a significant human toll as well as causes public fear, economic loss, and other adverse outcomes as mentioned earlier, it is common for health professionals and managers to focus predominantly on disease prevention and treatment, leaving/neglecting the psychological and psychiatric implications secondary to the phenomenon. This leads to a gap in coping strategies and increases the burden of associated diseases [43].

Therefore, understanding and investigating the public psychological states during this tumultuous time is of practical significance. Hence, this study aimed to determine the magnitudes of depression, anxiety, stress and their associated factors among University Students in Ethiopia. This study will provide a concrete basis for tailoring and implementing relevant mental health intervention policies to cope with the challenge of the outbreak efficiently and effectively.

Methods

Study area, design and period

This online cross-sectional survey was conducted among university students in Ethiopia. The actual data collection period was from June 30 to July 30, 2020.

Population and eligibility criteria

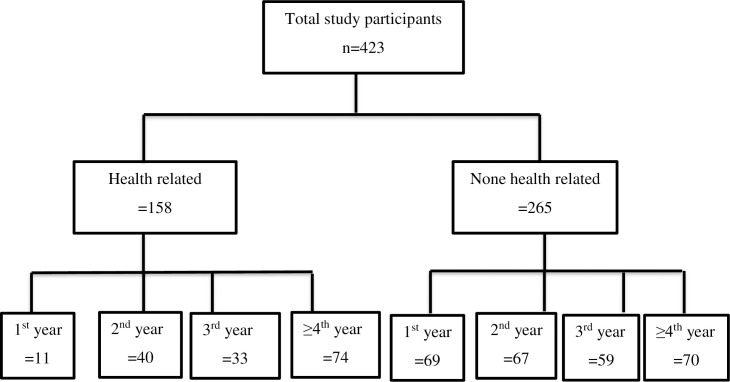

We included all University students who were using social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and who were voluntary to fill out the survey form. We preferred to use social media users because it enables us to collect the data without direct contact with the study participants, which is crucial to reduce the rate of spread of the COVID 19 pandemic. The flow chart of study participants is included below (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Flowchart of study participants.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula by considering the following assumptions; proportion (p) = 0.5 (since there was no previous study), 95% confidence level, the margin of error of 5%, and 10% non-response rate. The minimum sample size was 384 and after adding a non-response rate, we found a final sample size of 423.

Data collection questionnaire and procedure

We used Lovibond’s short version of the DASS-21 (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21) which is a psychological screening instrument capable of differentiating symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress [44]. Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains 7 items, divided into subscales with similar content. The cut-off values are explained elsewhere [44]. A single item was used to assess the levels of self-efficacy related to COVID-19: “How confident are you that you can prevent getting COVID-19 in case of an outbreak”[45].

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were collected using Google Forms and SPSS version 22 was used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed in terms of frequency and percent whereas continuous variables were described by the mean and standard deviation. Binary logistic regression was employed to identify associated factors of depression, anxiety and, stress. First, we performed bivariable binary logistic regression to identify candidate variables for the final analysis using p-value <0.2 as a cut-off point. Then, multivariable logistic regression was carried out to decide statistically significant variables of depression, anxiety, and stress at p-value<0.05.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Gondar Ethical Review Board. Consent was obtained from each study participant to assure their willingness to participate online and no identifiers were listed in the questionnaire to make it confidential. This study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Four hundred and twenty-three students participated in the study with a response rate of 100%. Two hundred and seventy-two (64.3%) were males and the mean age of study participants was 22.96 years (range: 18–34). One hundred and fifty-eight (37.4%) participants attended health-related departments and 34.0% of students were 4th year and above followed by the second year (25.3) and third-year (21.7%). Two hundred and twenty-nine (54.1%) participants reported that they had good-self efficacy. Two hundred and twenty-one (52.2%) participants thought that COVID-19 was preventable and 241 (57.0%) participants reported having a clear information source about COVID-19. Two hundred and eighty-five (67.4%) participants reported the presence of confirmed COVID-19 patient in the town they were living. Two hundred and ninety-one (68.8%) participants had reading materials about their profession and the majority of the participants (84.2%) had internet access (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants of depression, anxiety, stress among Ethiopian University students during an early stage of COVID-19, 2020 (N = 423).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 151 | 35.7 |

| Male | 272 | 64.3 | |

| Age in years | 18–21 | 111 | 26.2 |

| 22–23 | 141 | 33.3 | |

| 24–25 | 96 | 22.7 | |

| 26 and above | 75 | 17.7 | |

| Department | Health related | 158 | 37.4 |

| Other than health | 265 | 62.6 | |

| Year of study | 1st | 80 | 19.0 |

| 2nd | 107 | 25.3 | |

| 3rd | 92 | 21.7 | |

| 4th and above | 144 | 34.0 | |

| How do you rate yourself to protect yourself from COVID 19? | Not prepared | 194 | 45.9 |

| Prepared | 229 | 54.1 | |

| Do you think COVID-19 is preventable? | Yes | 221 | 52.2 |

| No | 202 | 47.8 | |

| Is there a clear information source that you can easily access about COVID 19? | Yes | 241 | 57.0 |

| No | 182 | 43.0 | |

| Do you feel that you are well protected from COVID-19 in your living area? | Yes | 174 | 41.1 |

| No | 249 | 58.9 | |

| Have you ever read any materials regarding the prevention of COVID-19? | Yes | 250 | 59.1 |

| No | 173 | 40.9 | |

| Is there any confirmed COVID-19 patient in the town you are living in? | Yes | 285 | 67.4 |

| No | 138 | 32.6 | |

| Have you got any reading materials about your profession? | Yes | 291 | 68.8 |

| No | 132 | 31.2 | |

| Can you access uninterrupted internet service? | Yes | 356 | 84.2 |

| No | 67 | 15.8 |

Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress

One hundred and ninety–six (46.3% (95% CI: 41.6%, 50.8%), 220 (52% (95% CI: 47.1%, 56.7%)) and 121 (28.6% (24.6%, 32.9%)) participants had depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among Ethiopian University students in Ethiopia during an early stage of COVID-19 pandemic 2020 (N = 423).

| Depression | Normal | 227 | 53.7 |

| Mild | 53 | 12.5 | |

| Moderate | 72 | 17.0 | |

| Sever | 22 | 5.2 | |

| Extremely sever | 49 | 11.6 | |

| Total with depression | 196 | 46.3% (95% CI: 41.6%, 50.8%) | |

| Anxiety | Normal | 203 | 48.0 |

| Mild | 35 | 8.3 | |

| Moderate | 74 | 17.5 | |

| Sever | 28 | 6.6 | |

| Extremely sever | 83 | 19.6 | |

| Total with anxiety | 220 | 52% (95% CI: 47.1%, 56.7%) | |

| Stress | Normal | 302 | 71.4 |

| Mild | 38 | 9.0 | |

| Moderate | 29 | 6.9 | |

| Sever | 33 | 7.8 | |

| Extremely sever | 21 | 5.0 | |

| Total with stress | 121 | 28.6% (95% CI: 24.6%, 32.9%) |

Factors associated with depression

Sex, age, department, self-efficacy, perception of whether COVID-19 is preventable, presence of easily accessible information source about COVID-19 prevention, self-rated preparation prevent from COVID-19, ever accessed any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19, presence any confirmed COVID-19 patient at the town of living, access to any reading materials about the profession, and access to uninterrupted internet were candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression (p-value<0.2). In the final model; female sex (AOR = 2.20; 95% CI: 1.25–3.86), not prepared to protect themselves from COVID-19 (AOR = 2.87; 95% CI: 1.59–5.20), not ever read any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19 (AOR = 2.25; 95% CI: 1.21–4.1)), had not any reading materials about profession (AOR = 2.38; 95% CI: 1.23–4.59), and lack of access to internet (AOR = 3.32; 95% CI: 1.34–8.21) were significantly associated with depression (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with depression among Ethiopian University students during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 (N = 423).

| Variables | Categories | Depression | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | Female | 96(63.6) | 55(36.4) | 3.00(1.98,4.54) | 2.20(1.25,3.86)* |

| Male | 100(36.8) | 172(63.2) | 1 | ||

| Age in years | 18–21 | 81(73.0) | 30(27.0) | 9.95(4.97,19.91) | 2.32(0.96,5.63) |

| 22–23 | 67(47.5) | 74(52.5) | 3.34(1.75,6.35) | 2.23(1.00,5.00) | |

| 24–25 | 32(33.3) | 64(66.7) | 1.84(0.91,3.70) | 1.92(0.82,4.50) | |

| 26 + | 16(21.3) | 59(78.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Department | Health related | 41(25.9) | 117(74.1) | 1 | |

| Other than health | 155(58.3) | 110(41.5) | 4.02(2.61,6.19) | 1.56(0.86,4.50) | |

| How do you rate to protect yourselves from COVID 19? | Not prepared | 144(74.2) | 50(25.8) | 9.80(6.27,15.32) | 2.87(1.59,5.20)** |

| prepared | 52(22.5) | 177(77.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Do you think COVID-19 is preventable? | Yes | 56(25.3) | 165(74.7) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 140(69.3) | 62(30.7) | 6.65(4.34,10.18) | 1.19(0.60,2.35) | |

| Is there a clear information source that you can easily access about COVID 19? | Yes | 59(24.5) | 182(75.5) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 137(75.3) | 45(24.7) | 9.39(6.01,14.68) | 1.72(0.82,3.59) | |

| Do you feel that you are well protected from COVID-19 in your living area? | Yes | 35(20.1) | 139(79.9) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 161(64.7) | 88(35.3) | 7.26(4.62,11.43) | 1.20(0.63,2.29) | |

| Have you ever read any materials regarding the prevention of COVID-19? | Yes | 68(27.2) | 182(72.8) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 128(74.0) | 45(26.0) | 7.6(4.90,11.81) | 2.25(1.22,4.13)* | |

| Is there any confirmed COVID-19 patient at town you are living? | Yes | 118(41.4) | 167(58.6) | 1.84(1.22,2.77) | 0.95(0.53,1.69) |

| No | 78(56.5) | 60(43.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Have you got any reading materials about your profession? | Yes | 93(32.0) | 198(68.0) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 103(78.0) | 29(22.0) | 7.56(4.67,12.22) | 2.38(1.23,4.59)* | |

| Can you access uninterrupted internet service? | Yes | 140(39.3) | 216(60.7) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 11(16.4) | 56(83.6) | 7.85(3.97,15.51) | 3.32(1.34,8.21)* | |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p-value = 0.236

* p-value <0.05

**p<0.01.

Factors associated with anxiety

Sex, age, department, self-rated protection from COVID-19, whether they thought COVID-19 is preventable, whether they feel that they are well protected from COVID-19 at their living area, whether they have ever read any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19, presence of any confirmed COVID-19 patient at the town they are living and access to reading materials about their profession were candidate variables for multivariable logistic regression (p-value<0.2). In the final model; female sex (AOR = 3.08; 95% CI: 1.6, 5.62), age 18–21 years (AOR = 4.78; 95% CI: 1.89, 12.09) and 22–23 years (AOR = 2.56; 95% CI: 1.99,10.42), being in none-health related departments (AOR = 2.67; 95% CI: 1.45,4.92), assuming that COVID-19 was not preventable (AOR = 3.50; 95% CI: 1.94,6.32), and did not read any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19 (AOR = 4.71; 95% CI: 2.56,8.67) were significantly associated with anxiety (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with anxiety among Ethiopian University students during early phase of COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 (N = 423).

| Variables | Categories | Anxiety | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | Female | 106(70.2) | 45(29.8) | 3.26(2.13,4.98) | 3.08(1.69,5.62)*** |

| Male | 114(41.9) | 158(58.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Age in years | 18–21 | 87(76.4) | 24(21.6) | 15.79(7.56,32.97) | 4.78(1.89,12.09)** |

| 22–23 | 80(56.7) | 61(43.3) | 5.71(2.92,11.16) | 2.56(1.99,10.42)** | |

| 24–25 | 39(40.6) | 57(59.4) | 2.98(1.46,6.06) | 3.67(1.54,8.77)* | |

| 26 + | 14(18.7) | 61(81.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Department | Health related | 45(28.5) | 113(71.5) | 1 | |

| Other than health | 175(66.0) | 90(34.0) | 4.88(3.18,7.49) | 2.67(1.45,4.92)* | |

| How do you rate to protect yourselves from COVID 19? | Not prepared | 144(74.2) | 50(25.8) | 5.79(3.78,8.85) | 1.12(0.62,2.20) |

| prepared | 76(33.2) | 153(66.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| Do you think COVID-19 is preventable? | Yes | 57(25.8) | 164(74.2) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 163(80.7) | 39(19.3) | 12.5(7.58,19.07) | 3.50(1.94,6.32)* | |

| Do you feel that you are well protected from COVID-19 in your living area? | Yes | 48(27.6) | 126(72.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 172(69.1) | 77(30.9) | 5.86(3.82,8.99) | 1.03(0.55,1.93) | |

| Have you ever read any materials regarding the prevention of COVID-19? | Yes | 74(29.6) | 176(70.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 146(84.4) | 27(15.6) | 12(4.90,11.81) | 4.71(2.56,8.67)*** | |

| Is there any confirmed COVID-19 patient in the town you are living in? | Yes | 141(49.5) | 144(50.5) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 79(57.2) | 59(42.8) | 1.36(0.90,2.05) | 1.12(0.64,2.09) | |

| Have you got any reading materials about your profession? | Yes | 121(41.6) | 170(58.4) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 170(58.4) | 33(25.0) | 4.21(2.66,6.66) | 1.57(0.80,3.07) | |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p-value = 0.773

* p-value <0.05

**p-value <0.01 and

*** p-value <0.001.

Factors associated with stress

Sex, department, years of study, self-rated protection from COVID-19, whether they thought COVID-19 is preventable, whether they feel that they are well protected from COVID-19 at their living area, whether they have ever read any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19, presence of any confirmed COVID-19 patient at the town they are living, access to reading materials about their profession, and access to uninterrupted internet service were candidate variables of stress for multivariable logistic regression(p-value<0.2). In the final model; female sex (AOR = 2.26; 95% CI:1.27, 4.03), 1st to 2nd years of study (AOR = 3.62; 95% CI: 2.03, 6.47), those who do not think that COVID-19 is preventable (AOR = 3.34; 95% CI: 2.13, 8.85), those who never read any materials regarding prevention of COVID-19 (AOR = 2.15; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.99), presence of confirmed COVID-19 patient at the town they are living (AOR = 1.81; 95% CI: 1.01,3.28), and not having any reading materials about their profession (AOR = 2.17; 95% CI: 1.15, 4.07) were significantly associated with stress (Table 5).

Table 5. Factors associated with stress among Ethiopian University students during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 (N = 423).

| Variables | Categories | Stress | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | Female | 67(44.4) | 84(55.6) | 3.22(2.07,4.99) | 2.26(1.27,4.03)* |

| Male | 54(19.9) | 218(80.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Department | Health related | 20(12.7) | 138(87.3) | 1 | |

| Other than health | 101(38.1) | 164(61.9) | 4.24(2.50,7.20) | 1.52(0.71,3.22) | |

| Year of study | 1–2 | 93(49.7) | 94(50.3) | 7.35(4.51,11.96) | 3.62(2.03,6.47)*** |

| ≥3 | 28(11.9) | 208(88.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| How do you rate your to protect yourselves from COVID 19? | Not prepared | 91(46.9) | 103(53.1) | 5.86(3.64,9.43) | 1.03(0.51,2.08) |

| Prepared | 30(13.1) | 199(86.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Do you think COVID-19 is preventable? | Yes | 18(8.1) | 203(91.9) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 103(51.0) | 99(49.0) | 11.70(6.12,20.45) | 3.34(2.13,8.85)* | |

| Do you feel that you are well protected from COVID-19 in your living area? | Yes | 18(10.3) | 156(89.7) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 103(41.4) | 146(58.6) | 6.26(3.62,10.43) | 1.01(0.47,2.16) | |

| Have you ever read any materials regarding the prevention of COVID-19? | Yes | 30(12.0) | 220(88.0) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 91(52.6) | 82(47.4) | 8.5(5.90,13.51) | 2.15(1.12,3.99)* | |

| Is there any confirmed COVID-19 patient in the town you are living in? | Yes | 66(23.2) | 219(76.8) | 2.14(1.22,3.77) | 1.81(1.01,3.28)* |

| No | 55(39.9) | 83(60.1) | 1 | 1 | |

| Have you got any reading materials about your profession? | Yes | 49(16.8) | 242(83.2) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 72(54.5) | 60(45.5) | 5.96(3.67,9.22) | 2.17(1.15,4.07)* | |

| Can you access uninterrupted internet service? | Yes | 85(23.9) | 271(76.1) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 36(53.7) | 31(46.3) | 3.75(2.97,6.51) | 1.28(0.60,2.77) | |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test p-value = 0.374

* p-value <0.05

**p-value <0.01 and

*** p-value <0.001.

Discussion

This study aimed at assessing depression, anxiety and stress as well as their associated factors among Ethiopian University students during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. About 46.3% with 95% CI (41.6%, 50.8%) of students reported depression while 52% with 95% CI (47.1%, 56.7%) reported anxiety and about 28.6% with 95% CI (24.6%, 32.9%) reported stress in the current study. Being female and lack of access to reading materials regarding COVID-19 were common risk factors for depression, anxiety and stress. Besides, students who reported to be not well prepared to protect themselves from the pandemic (those with lower self-efficacy), those who have no reading materials at hand about their profession, and those who had no sufficient uninterrupted internet access were more depressed. Students with lower age, those who were from non-health-related fields, and those who do not think that COVID-19 is preventable, and those who had no reading materials at hand were more anxious whereas study subjects who had no sufficient uninterrupted internet access, those at 1st and 2nd year and those living in areas where there is confirmed case of COVID-19 were more stressed in the current study.

The prevalence of depression in the current study was lower than reports from Bangladesh [46], Jordan [47] and Pakistan [12]. However, it was higher than studies conducted among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic from Guangzhou, China [48], Spain [18], Iran [49] and European College students [10]. The current prevalence was also higher than studies in Ethiopia among University students before the pandemic [50].

The current prevalence of anxiety was higher than reports from China [48], Jordan [47] and Iran [49]. However, it was lower than studies from Poland [51] and Pakistan [12].

The prevalence of stress in this study was lower than a report from Poland [51] and Pakistan [12].

The variation in the prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress might be attributed to the differences in the socioeconomic conditions, times of the study, the different impact of COVID-19 and the tool used to assess these mental health outcomes. For example in the study from Bangladesh [46] the tool used to assess depression and anxiety were the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), respectively. The study from China [48] used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) for assessing depression and anxiety, respectively. The tool used to assess stress in Poland [51] was the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). Whereas in Iran [49] authors used Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI-II) and Beck’s Anxiety Inventory (BAI) for assessing depression and anxiety, respectively. However, we have used DASS-21 for the assessment of depression, anxiety and stress in the current study.

Female students were more depressed, anxious and stressed in the current study. This finding is consistent with several earlier studies [1, 23, 29, 33–42]. Some evidence [52, 53] suggested that the female reproductive cycle may have a role in the pronounced prevalence of mental illnesses among females. The intensive fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone during the menstrual cycle is related to changes in the hormone’s neuroprotective effects, which might escalate the chronicity correlated with mental health problems [52]. This might also be related to the lower risk of developing mental illnesses in males due to differential access to appropriate health care services [54]. Metacognitive beliefs in uncontrollability, advantages and avoidance of worry may also contribute to the higher prevalence of mental illness among females as compared to males [55]. So far, several environmental, genetic and physiological factors were suggested that may play a significant role in the gender differences of mental illness problems [56–58]. However, a study in China revealed the absence of variation in mental health problems based on gender [59].

Students with a lack of access to reading material regarding COVID-19 had higher odds of depression, anxiety and stress. This is clear as more informed study subjects will have reduced levels of mental illnesses as they have sufficient choice to protect themselves from the pandemic [60]. Students with clear information about the cause, route of transmission and prevention mechanisms of the pandemic are less likely to be depressed, anxious and stressed. Those without clear information are liable to misinformation and there is a growing body of literature that reveals the link between misinformation and mental illness [46, 61–64]. Timely and accurate information is fundamental for mitigating and preventing the pandemic [65, 66].

Likewise, study subjects who had no sufficient uninterrupted internet access were more stressed. Those study subjects from the non-health area of study were more anxious in this survey. This is in line with previous studies [16–18]. Students in the health and health-related field are expected to have more appropriate and accurate information and may help them to get prepared easily to protect themselves from the pandemic which in turn will help to reduce anxiety due to the adverse condition.

Students with lower self-efficacy were more depressed in the current study. Self–efficacy shows to what extent the students are well prepared to cope up with the pandemic. In line with our result, earlier studies also showed that study participants with lower self-efficacy were prone to poor mental health conditions [19–21]. Better self-efficacy has a significant role in promoting desirable performance in the face of adversity conditions [67].

Students with younger ages were more likely to be anxious in this study. This is supported by numerous previous studies [23–32]. The possible explanation might be due to developmental challenges during adolescence that may provoke more anxiety among younger aged adults [68, 69].

Study subjects at 1st and 2nd year and those living in areas where there is a confirmed case of COVID-19 were also more stressed in the current study. This finding is in line with a study done among Spanish students [18]. However, this finding was against a previous result reported among under-graduate students in New Jersey [70].

Finally, this study was the first study in Ethiopia to assess depression, anxiety, and stress among university students at the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a strength, we used a robust and validated tool whereas the result of this survey should be utilized bearing in mind several limitations. The limitations include; lack of generalizability due to a small sample size and absence of random sampling as this study was based on voluntary participation. Besides, social desirability bias and the inherent weakness of the cross-sectional design may result in over or under-report of the symptoms. Since this was a cross-sectional survey whether the heightened level of mental illnesses is due to COVID-19 or other factors is poorly understood.

Conclusions

A significant proportion of students were affected by common mental illnesses (i.e. depression, anxiety and stress). The level of depression, anxiety, and stress among students are higher as compared to several reports before the pandemic. Numerous factors such as age, gender, self-efficacy, year and field of study, availability of information source and reading materials were identified as factors contributing to either of the common mental health problems. The mental health situation may be improved by the provision of adequate and accurate information and raising the self-efficacy of students.

Supporting information

(SAV)

(SAV)

(SAV)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the study participants.

List of abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- COR

Crude Odds Ratio

- COVID-19

Coronavirus Disease

- DASS

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Data Availability

The data underlying the results presented in the study are available and will be shared during publication.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(2). 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard 2020. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=Cj0KCQiAhs79BRD0ARIsAC6XpaVKVf1AmzsG1TR-1m6f5PGCBlKztax-rroLTtyE3Zr9KJ-uIe8iOkwaAhRTEALw_wcB.

- 3.Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2020:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Jama. 2004;291(21):2581–90. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilmour H, Patten SB. Depression and work impairment. Health Rep. 2007;18(1):9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakhan R, Agrawal A, Sharma M. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2020;11(4):519–25. 10.1055/s-0040-1716442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saleh D, Camart N, Romo L. Predictors of Stress in College Students. Frontiers in psychology. 2017;8:19. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Othman N, Ahmad F, El Morr C, Ritvo P. Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety and stress: a survey with university students. International journal of mental health systems. 2019;13(1):17. 10.1186/s13033-019-0275-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habihirwe P, Porovecchio S, Bramboiu I, Ciobanu E, Croituru C, Cazacu I, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among college students in three European countries. European Journal of Public Health. 2018;28(suppl_4). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfawaz HA, Wani K, Aljumah AA, Aldisi D, Ansari MG, Yakout SM, et al. Psychological well-being during COVID-19 lockdown: Insights from a Saudi State University’s Academic Community. Journal of King Saud University-Science. 2021;33(1):101262. 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.101262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar B, Shah MAA, Kumari R, Kumar A, Kumar J, Tahir A. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Final-year Medical Students. Cureus. 2019;11(3):e4257. 10.7759/cureus.4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syed A, Ali SS, Khan M. Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among the undergraduate physiotherapy students. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2018;34(2):468–71. 10.12669/pjms.342.12298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teh CK, Ngo CW, binti Zulkifli RA, Vellasamy R, Suresh K. Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students: A cross sectional study. Open Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;5(04):260. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kebede MA, Anbessie B, Ayano G. Prevalence and predictors of depression and anxiety among medical students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:30. 10.1186/s13033-019-0287-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang J, Yuan Y, Wang D. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = Journal of Southern Medical University. 2020;40(2):171. 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.02.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ojewale LY. Psychological state and family functioning of University of Ibadan students during the COVID-19 lockdown. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odriozola-González P, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Irurtia MJ, de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Research. 2020:113108. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yıldırım M, Güler A. COVID-19 severity, self-efficacy, knowledge, preventive behaviors, and mental health in Turkey. Death Studies. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Khalek AM, Lester D. The association between religiosity, generalized self-efficacy, mental health, and happiness in Arab college students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;109:12–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deying H, Yue K, Wengang L, Qiuying H, Xin ZHANG LXZ, Su Wei W, et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah SMA, Mohammad D, Qureshi MFH. Prevalence, Psychological Responses and Associated Correlates of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in a Global Population, During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2020:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C, Pacitti F, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2020;11:790. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda M, Stickley A, Sueki H, Matsubayashi T. Mental Health Status of the General Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional National Survey in Japan. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neto MLR, Almeida HG, Esmeraldo JDa, Nobre CB, Pinheiro WR, de Oliveira CRT, et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: the mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Research. 2020:112972. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020:102076. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2020;136:110186. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rettie H, Daniels J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020. 10.1037/amp0000710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kebede MA, Anbessie B, Ayano G. Prevalence and predictors of depression and anxiety among medical students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. International journal of mental health systems. 2019;13(1):30. 10.1186/s13033-019-0287-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radeef AS, Faisal GG, Ali SM, Ismail MKHM. Source of stressors and emotional disturbances among undergraduate science students in Malaysia. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2014;3(2):401–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holingue C, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Riehm KE, Veldhuis CB, Thrul J, Johnson RM, et al. Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: Findings from American trend panel survey. Preventive medicine. 2020;139:106231. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burstein M, He J-P, Kattan G, Albano AM, Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Social phobia and subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement: prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(9):870–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao W, Ping S, Liu X. Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: a longitudinal study from China. Journal of affective disorders. 2020;263:292–300. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological Impact and Coping Strategies of Frontline Medical Staff in Hunan Between January and March 2020 During the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2020;26:e924171–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sareen J, Erickson J, Medved MI, Asmundson GJ, Enns MW, Stein M, et al. Risk factors for post‐injury mental health problems. Depression and anxiety. 2013;30(4):321–7. 10.1002/da.22077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X, Meng Z, Huang G, Fan J, Zhou W, Ling W, et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety disorders in mainland China from 2000 to 2015. Scientific reports. 2016;6(1):1–15. 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R. Adult psychiatric morbidity in England: results of a household survey: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeshaw Y, Mossie A. Depression, anxiety, stress, and their associated factors among Jimma University staff, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia, 2016: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2017;13:2803. 10.2147/NDT.S150444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, Wang L, Qiu XH, Yang XX, Qiao ZX, Yang YJ, et al. Depression among Chinese university students: prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. PloS one. 2013;8(3):e58379. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habihirwe P, Porovecchio S, Bramboiu I, Ciobanu E, Croituru C, Cazacu I, et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among college students in three European countries. European Journal of Public Health. 2018;28(suppl_4):cky214. 026. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging infectious diseases: threats to human health and global stability. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003467. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour research and therapy. 1995;33(3):335–43. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Zwart O, Veldhuijzen IK, Elam G, Aro AR, Abraham T, Bishop GD, et al. Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2009;16(1):30–40. 10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Islam MA, Barna SD, Raihan H, Khan MNA, Hossain MT. Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A web-based cross-sectional survey. PloS one. 2020;15(8):e0238162. 10.1371/journal.pone.0238162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malak MZ, Khalifeh AH. Anxiety and depression among school students in Jordan: Prevalence, risk factors, and predictors. Perspectives in psychiatric care. 2018;54(2):242–50. 10.1111/ppc.12229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z-H, Yang H-L, Yang Y-Q, Liu D, Li Z-H, Zhang X-R, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: A large cross-sectional study. Journal of affective disorders. 2020;275:188–93. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakhostin-Ansari A, Sherafati A, Aghajani F, Khonji M, Aghajani R, Shahmansouri N. Depression and anxiety among Iranian Medical Students during COVID-19 pandemic. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;15(3):228–35. 10.18502/ijps.v15i3.3815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dagnew B, Dagne H, Andualem Z. Depression and Its Determinant Factors Among University of Gondar Medical and Health Science Students, Northwest Ethiopia: Institution-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020;16:839. 10.2147/NDT.S248409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogowska AM, Kuśnierz C, Bokszczanin A. Examining anxiety, life satisfaction, general health, stress and coping styles during COVID-19 pandemic in Polish sample of university students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2020;13:797. 10.2147/PRBM.S266511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pigott TA. Anxiety disorders in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003. 10.1016/s0193-953x(03)00040-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Veen JF, Jonker BW, Van Vliet IM, Zitman FG. The effects of female reproductive hormones in generalized social anxiety disorder. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2009;39(3):283–95. 10.2190/PM.39.3.e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of psychiatric research. 2011;45(8):1027–35. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bahrami F, Yousefi N. Females are more anxious than males: a metacognitive perspective. Iranian journal of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. 2011;5(2):83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tambs K, Kendler KS, Reichborn‐Kjennerud T, Aggen SH, Harris JR, Neale MC, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to the relationship between education and anxiety disorders–a twin study. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica. 2012;125(3):203–12. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01799.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amstadter AB, Maes HH, Sheerin CM, Myers JM, Kendler KS. The relationship between genetic and environmental influences on resilience and on common internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2016;51(5):669–78. 10.1007/s00127-015-1163-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Domschke K, Maron E. Genetic factors in anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders. 29: Karger Publishers; 2013. p. 24–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry research. 2020:112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leaders DFT. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. The Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vickers NJ. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Current biology. 2017;27(14):R713–R5. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karthik L, Kumar G, Keswani T, Bhattacharyya A, Chandar SS, Rao KB. Protease inhibitors from marine actinobacteria as a potential source for antimalarial compound. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e90972. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen IH, Chen CY, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59(10). 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hua J, Shaw R. Corona virus (Covid-19)“infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of china. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(7):2309. 10.3390/ijerph17072309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mian A, Khan S. Coronavirus: the spread of misinformation. BMC medicine. 2020;18(1):1–2. 10.1186/s12916-019-1443-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amini MT, Noroozi R. Relationship between self-management strategy and self-efficacy among staff of Ardabil disaster and emergency medical management centers. Health in Emergencies and Disasters. 2018;3(2):85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lecrubier Y, Wittchen H-U, Faravelli C, Bobes J, Patel A, Knapp M. A European perspective on social anxiety disorder. European Psychiatry. 2000;15(1):5–16. 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00216-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leigh E, Clark DM. Understanding social anxiety disorder in adolescents and improving treatment outcomes: applying the cognitive model of Clark and Wells (1995). Clinical child and family psychology review. 2018;21(3):388–414. 10.1007/s10567-018-0258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kecojevic A, Basch CH, Sullivan M, Davi NK. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on mental health of undergraduate students in New Jersey, cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020;15(9):e0239696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]