Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic led to cancelation of all elective surgeries for a time period in the vast majority of the United States. We compiled a questionnaire to determine the physical and mental toll of this delay on elective total joint arthroplasty patients.

Methods

All patients whose primary or revision total hip or knee arthroplasty was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic at a large academic-private practice were identified. An 11-question survey was administered to these patients via email. All data were deidentified and stored in a REDCAP database.

Results

Of 367 total patients identified, 113 responded to the survey. Seventy-seven percent of patients had their surgery postponed at least 5 weeks, and 20% were delayed longer than 12 weeks. Forty-one percent of patients reported an average visual analog scale pain score greater than 7.5. Forty percent of respondents experienced increased anxiety during the delay. Thirty-four percent of patients felt their surgery was not elective. Sixteen percent experienced a fall during the delay, and 1 patient sustained a hip fracture. Level of pain reported was significantly associated with negative emotions, negative effects of delay, and whether patients felt their surgery was indeed elective. Seventy-six percent reported trust in their surgeon’s judgment regarding appropriate timing of surgery. Communication was listed as the number one way in which patients felt their surgeon could have improved during this time.

Conclusion

Surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased pain and anxiety for many total joint arthroplasty patients. While most patients maintained trust in their surgeon during the delay, methods to improve communication may benefit the patient experience in future delays.

Level of Evidence

Level II.

Keywords: COVID-19, Patient reported outcomes, Elective arthroplasty, Delay, Pain

Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 global pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in conjunction with the White House Task Force, recommended cancelation of all elective surgeries to protect vulnerable patients from contracting the virus and to preserve necessary medical personal protective equipment in preparation for a massive influx of patients with COVID-19 into hospitals [1]. It is estimated that, after excluding essential procedures, 30,000 primary and 3000 revision elective total hip and knee arthroplasty procedures (THA and TKA, respectively) were canceled per week during this time period [2,3]. For patients with arthritis of the hip and knee, this translated into an extended time waiting in pain and reduced function for an unknown period of time.

Advanced arthritis of the hip and knee results in significant pain and disability. Total joint arthroplasty consistently provides significant pain relief and allows patients to return to their daily functions with improvements in their preoperative disabilities [[4], [5], [6]]. Determining the optimal timing of surgery is a multifactorial process, but there is evidence that increased preoperative pain level negatively affects recovery, [7] and delays in time to surgery in patients undergoing elective total joint arthroplasty may lead to worse dysfunction and ultimately worse postoperative outcomes [8,9]. Therefore, pain is a major factor in the complex calculation that takes place when patients and surgeons decide to schedule joint replacement.

In the wake of the COVID-19 response, our large academic-private practice canceled or postponed more than 300 electively scheduled surgeries. Recognizing that patients schedule joint replacement surgery based on pain and disability level at a time that is most convenient, we sought to understand the physical and emotional toll that patients experienced as a result of further delay imposed by the pandemic response.

A concise but thorough survey was administered to patients whose THA and TKA surgeries were canceled or postponed in response to the viral crisis to more fully understand how they were affected by the delay. Furthermore, we sought to explore the relationship between pain level and the experience of negative emotion. We hypothesized that patients would experience progression of pain and negative emotions, which would affect their perception of elective surgery. Finally, we hypothesized that surgeon communication would provide a protective effect on pain level and negative emotion.

Material and methods

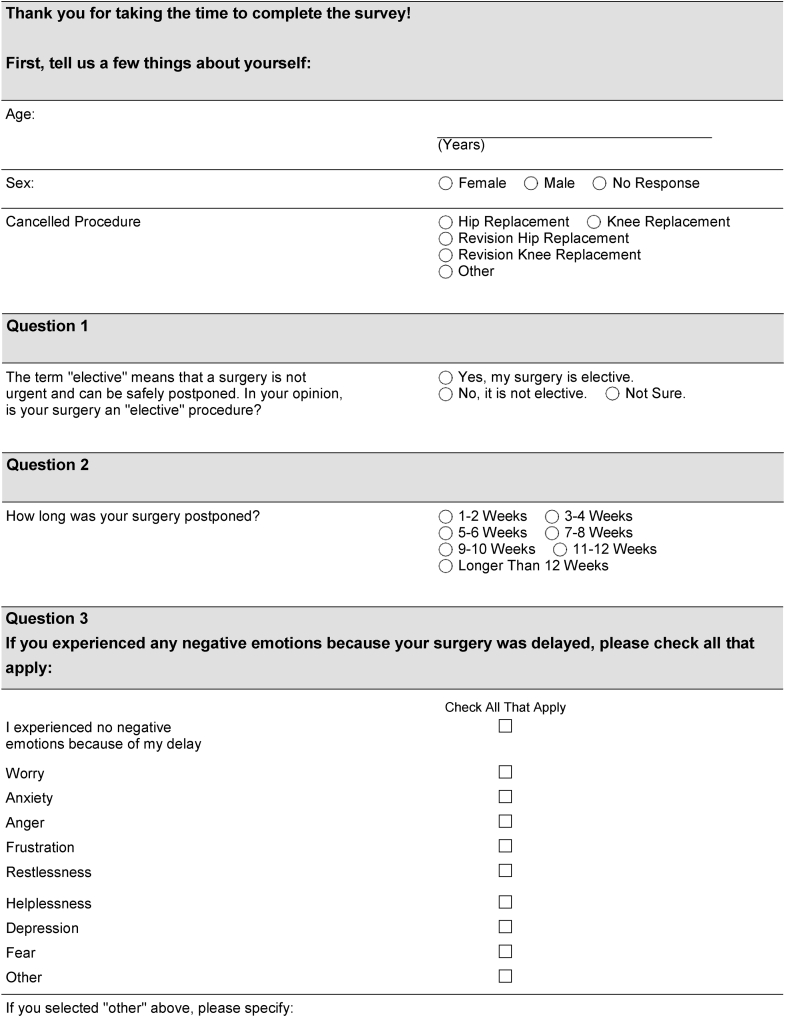

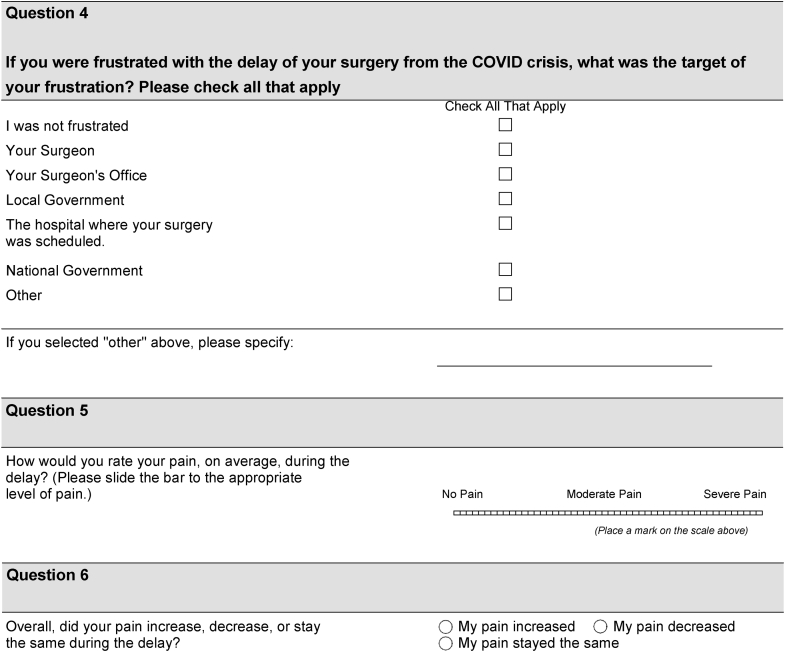

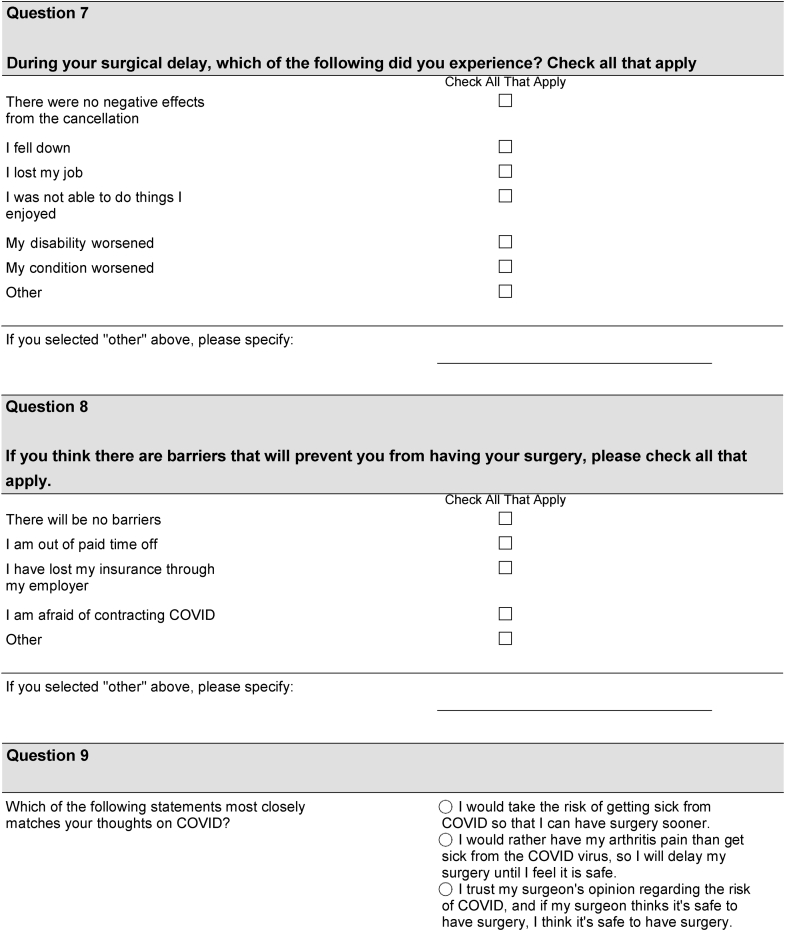

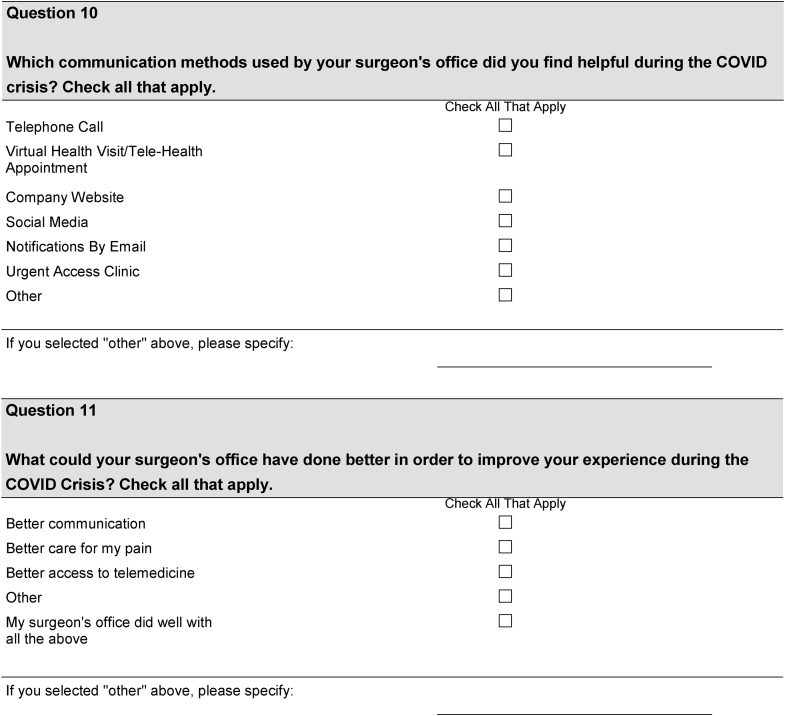

On March 18th, 2020, elective surgeries were stopped in our community due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Surgeries that were deemed to be urgent or emergent, based on surgeon evaluation, were not canceled. At our hip and knee center within a private academic orthopedic practice, 368 patients were scheduled for elective hip or knee arthroplasty surgery that was ultimately canceled during an 8-week timeframe because of these changes. An 11-question survey that was designed at our institution that has not yet been externally validated was digitally administered to patients who experienced a delay in their surgery during this time (Fig. 1). Questions were formulated to determine the following: length of surgical delay, emotions experienced during waiting period, pain progression, trust in one’s surgeon to determine safe timing of surgery, and feelings about communication between surgical team and patient during this time. Patient demographics including gender and age were also collected. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted locally at the OrthoCarolina Research Institute [10,11]. After review and approval by the Atrium Health Institutional Review Board, the survey was disseminated to patients whose surgery was delayed via email using the REDCap platform 3 separate times in May of 2020: May 19, May 22, and May 25. Those patients who consented to voluntarily participate completed the survey, and their responses were directly stored in the REDCap database.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 patient questionnaire.

Patients

Of the 368 patients whose surgery was canceled or postponed, one patient younger than 18 years, a nonresponder, was excluded. Of the 367 patients, 113 (31%) responded to and completed the survey. Of the respondents, 63 were scheduled for hip arthroplasty surgery (59 primary THA, 4 revision THA), and 50 were scheduled for knee surgery (44 primary TKA, 6 revision TKA).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Frequency and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Measures of central tendency and variance were calculated using statistical parameters appropriate for the distribution of the data. Statistical associations between patient self-reported delay time and categorical variables were determined with Chi-square tests. Wilcoxon tests were used to determine associations with numeric pain score. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests. Data were analyzed using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC).

Results

Overall, most study patients reported a delay of 8 weeks or less. Seventeen (15%) patients reported a delay of 0-4 weeks, 52 (46%) patients reported a 4- to 8-week delay, 21 (19%) patients reported a 9- to 12-week delay, and 23 (20%) patients reported a delay of longer than 12 weeks. The median numeric pain score for the study group was 72 (interquartile range: 61, 84).

Most patients believed that their surgery was elective (64 of 113, 57%). Most patients had increased stress (Table 1) during the delay due to negative emotions (75 of 113, 66%), a negative effect (85 of 113, 75%), or increased pain (66 of 113, 58%). The survey responders were positive toward their surgeon and the clinic. Only 1 (4%) responded that they were frustrated with the surgeon or clinic. A total of 76% (86 of 113) trusted their surgeon to schedule their surgery when it was safe to do so. However, 14% (16 of 113) would rather delay surgery than risk exposure to COVID-19, and 10% (11 of 113) would rather risk exposure to the virus than delay surgery. Table 1 summarizes survey responses.

Table 1.

Survey responses during surgical delay.

| Negative emotion | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Frustration | 59 (52) |

| Anxiety | 45 (40) |

| Worry | 44 (39) |

| Restlessness | 30 (27) |

| Helplessness | 30 (27) |

| Depression | 20 (18) |

| Fear | 14 (12) |

| Anger | 13 (11.5) |

| Negative effect | |

| Condition worsened | 66 (57) |

| Unable to engage in leisure | 64 (57) |

| Disability worsened | 36 (32) |

| Fell | 18 (16) |

| Lost job | 2 (2) |

| Target of frustration | |

| None | 39 (34.5) |

| Local government | 22 (19.5) |

| National government | 16 (14) |

| Hospital | 15 (12.8) |

| Surgeon office | 4 (3.5) |

| Surgeon | 1 (0.9) |

| Thoughts on COVID | |

| Trust surgeon | 86 (76) |

| Delay surgery | 16 (14) |

| Risk surgery | 11 (10) |

| Helpful communication methods | |

| Phone call | 92 (81) |

| 47 (42) | |

| Virtual visit | 23 (20) |

| Other | 11 (10) |

| Company website | 10 (9) |

| Social media | 2 (2) |

| Urgent access clinic | 1 (.9) |

| Areas for improvement | |

| None | 57 (50) |

| Communication | 39 (34.5) |

| Pain care | 19 (17) |

| Other | 7 (6) |

| Telemedicine access | 2 (2) |

Statistically significant associations were found between patients’ reported pain level (Table 2) and experience of a negative emotion as well as a negative effect during the delay (P < .0001). Patients who reported a higher pain level were more likely to feel that their surgery was not elective (P = .0002). Patients with higher pain levels were more likely to report that they would risk becoming ill from COVID-19 than those with lower pain scores (P = .0009). We found no statistical difference in patient’s undergoing primary vs revision arthroplasty in their negative emotions, thoughts on whether surgery was elective or not, or overall pain rating. We did find that those undergoing THA vs TKA experienced significantly higher numeric pain scores, had a higher chance of reporting that the surgery was not elective, had a higher likelihood of reporting negative effect, and had more pain increase (Table 2, Table 3). In addition, no statically significant differences were found between patients based on timing of when they answered their questions and when they ultimately underwent surgery. No statistically significant associations were found between duration of reported surgical delay (Table 4) and negative emotion, negative experience, pain perception, or opinion regarding elective surgery.

Table 2.

Association between patients emotions and perceived pain.

| Questionairre response | Numeric pain score median (Q1, Q3) | P-value (Wilcoxon) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 72 (61, 84) | |

| Negative emotion | ||

| Yes | 77 (66, 88) | <.0001a |

| No | 61 (50, 71) | |

| Negative effect | ||

| Yes | 75 (67, 87) | <.0001a |

| No | 53 (50, 66) | |

| Elective | ||

| Yes | 66.5 (51.5, 78) | .0002a |

| No | 76 (67, 88) | |

| Pain increase | ||

| Yes | 76.5 (70, 87) | <.0001a |

| No | 61 (50, 71) | |

| Had surgery | ||

| Yes | 74 (63, 86) | .0816 |

| No | 69.5 (59, 77) | |

| COVID-related barriers | ||

| Trust surgeon | 73 (61, 83) | .0009a |

| Will not risk COVID | 61.5 (50, 65.5) | |

| Will risk COVID | 84 (77, 88) | |

| Patient perceived delay | ||

| 0-4 wks | 71 (61, 83) | .5108 |

| 4-8 wks | 73 (65.5, 85.5) | |

| 9-12 wks | 73 (52, 80) | |

| >12 wks | 65 (58, 79) | |

| Canceled surgery type | ||

| Hip | 74 (67, 87) | .0065 |

| Knee | 65 (51, 49) | |

| Canceled surgery type | ||

| Primary | 72 (61, 84) | .5007 |

| Revision | 70 (50, 80) | |

| Timing of survey | ||

| After surgery | 78 (67, 91) | .0838 |

| During delay/before surgery | 73 (61, 83) | |

| During delay/did not have surgery | 69.5 (59, 77) |

Significant at the 0.01 level.

Table 3.

Patients emotion experienced on basis of whether they were scheduled to undergo total hip or total knee arthroplasty.

| Questionairre response | Hip | Knee | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 66 (58%) | 47 (42%) | |

| Negative emotion | |||

| Yes | 48 (73%) | 29 (57%) | .0728 |

| No | 18 (27%) | 22 (43%) | |

| Negative effect | |||

| Yes | 56 (85%) | 31 (61%) | .0031 |

| No | 10 (15%) | 20 (39%) | |

| Elective | |||

| Yes | 31(47%) | 36 (71%) | .0104 |

| No | 35 (53%) | 15 (29%) | |

| Pain increase | |||

| Yes | 46 (70%) | 22 (43%) | .0039 |

| No | 20 (30%) | 29 (57%) | |

| Surgery delayed | |||

| 0-4 wks | 10 (15%) | 8 (16%) | .1664 |

| 4-8 wks | 32 (48%) | 21 (41%) | |

| 9-12 wks | 15 (23%) | 7 (14%) | |

| >12 wks | 9 (14%) | 15 (29%) |

Table 4.

Association between time of delay and patients responses to questionairre.

| Questionairre response | Overall | Patient reported delay, N (%) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-4 wks | 4-8 wks | 9-12 wks | >12 wks | |||

| Negative emotion | ||||||

| Yes | 75 (66%) | 9 (53%) | 36 (69%) | 17 (81%) | 13 (56.5%) | .2066 |

| No | 38 (34%) | 9 (47%) | 16 (31%) | 4 (19%) | 11 (43%) | |

| Negative effect | ||||||

| Yes | 85 (75%) | 11 (65%) | 39 (75%) | 18 (86%) | 17 (74%) | .5180 |

| No | 28 (25%) | 6 (35%) | 13 (25%) | 3 (14%) | 6 (26%) | |

| Elective surgery | ||||||

| Yes | 64 (57%) | 8 (47%) | 30 (58%) | 10 (48%) | 16 (70%) | .4042 |

| No | 49 (43%) | 9 (53%) | 22 (42%) | 11 (52%) | 7 (30%) | |

| Pain increase | ||||||

| Yes | 66 (58%) | 9 (53%) | 31 (60%) | 12 (57%) | 14 (61%) | .9578 |

| No | 47 (42%) | 8 (47%) | 21 (40%) | 9 (43%) | 9 (39%) | |

| Delay total | 18 (15.4%) | 53 (45.3%) | 22 (18.8%) | 24 (20.5%) | ||

Discussion

On March 18, 2020, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, in concert with the White House Task Force, called for a delay in adult elective and nonessential surgeries to contain the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and preserve the resources needed to respond to the eventual demands of COVID-19 [12]. As a result, elective surgeries were canceled or postponed in nearly every state, disrupting the lives of patients scheduled to undergo TJA. The present study sought to understand the emotional and physical distress that patients experienced after the delay of their total joint replacement. Although TJA is categorized as elective, patients experience significant pain and disability due to arthritic joints and often delay surgery as long as possible. With this in mind, further delay may be a significant source of progression of pain and disability, affecting patients’ perception regarding the elective nature of their scheduled surgery. Indeed, we found that during the delay, one-third of patients did not feel their surgery should be categorized as elective.

We found anxiety to be prevalent in our cohort. Patients with arthritis have high levels of anxiety at baseline, [[13], [14], [15], [16]] which can be associated with worse outcomes after arthroplasty [[17], [18], [19], [20]]. Over 40% of patients experienced anxiety due to delay in surgery. A recent study by Brown et al. evaluated emotions experienced by a cohort of patients who had delay in arthroplasty due to the pandemic [21]. They found that 60% of their cohort had anxiety about not knowing when their surgery would be rescheduled. These findings suggest that any delay in surgery has a major impact on patient emotional health, with anxiety being the most profound emotion experienced. This ultimately leads to a negative effect on patient outcomes after surgery [[17], [18], [19], [20]].

Wait times for elective TJA can be significant and have major impacts on patients’ postoperative outcome. Ostendorf et al. evaluated the effect of wait times on patients' postoperative function [7]. The authors reported that patients with an average waiting period of 6 months experienced considerably more functional decline and lower quality-adjusted life years than patients who experienced no delay in surgery. Similarly, Ackerman et al. found a major decline in patients who had a delay to TJA [22]. The present study found that over 50% of patients stated they enjoyed daily activities less and had a progression of their pain. These findings support the notion that major wait times or delays to TJA have a substantial impact on patient's’ quality of life and should be avoided when possible. It also supports the continued need for the design of health-care pathways that ensure the speedy and efficient referral of patients with debilitating joint pain caused by arthritis to arthroplasty surgeons to be evaluated and ultimately treated.

One of the most profound findings of the present study is the significant association between pain level reported and negative emotions, effects, and perception of elective surgery. Furthermore, patients who reported a higher level of pain were significantly more likely to report an increase in pain over the waiting period. Patients with higher pain levels were also more likely to report willingness to risk COVID contraction and, ultimately, were more likely to have undergone surgery at the time of this analysis.

Importantly, our results elucidated the strength of the patient-surgeon relationship. Nearly 99% of patients did not feel any frustration with their surgeon personally. In addition, 76% of patients trusted their surgeon to make the right choice regarding delay and timing of surgery. Although this is a good majority, it does bring into question why 24% of patients did not trust their surgeons. It is unclear why this amount did not trust their surgeons to make the right decision. It could be theorized that due to the general lack of consensus on COVID-19 and how to combat the virus led to a distrust in some people toward health-care professionals in general. It also could be due to the general distrust some patients have in health care as a whole due to changes in delivery and presumed lack of transparency. Axelrod and Goold [23] reviewed the critical aspects of the surgeon-patient relationship. The article highlighted the importance of transparency, communication, and advocacy of the surgeon to build trust in the surgeon-patient relationship. Surgeons need to constantly be conducting patient-centric communication and enhance their ethical education to ensure patients feel comfortable in the relationship given the high vulnerability experienced when undergoing a surgical procedure. In addition, over 80% of patients appreciated receiving a phone call from their surgeon, and the number one thing patients felt that could be improved upon during this time period was patient and surgeon communication. These findings highlight the importance of open dialog between patients and surgeons. Several studies have found a major impact on communication between patient and surgeon and its effect on postoperative outcomes [24,25]. This communication is especially important in times of high uncertainty, as in the case of the current pandemic. Something as simple as a phone call from the surgeon or surgeon’s team can make major differences in patient outcomes and anxiety experienced during the perioperative period [26,27]. Although often difficult due to busy schedules and other demands, surgeon communication with patients during times of uncertainty is an effective method to build trust.

The reported results should be interpreted in light of several study limitations. First, there was a response rate of 32%. However, this rate is consistent with many web-based surveys in the medical literature, which consistently achieve less than 50% response rate [28,29]. Regardless of cause, this response rate could introduce a response bias that creates difficulty in accurately assessing these results. However, there is little concern that this would affect the overall validity of our data or our ultimate conclusions because the goal of the present study was to be a descriptive study to report on patient emotions experienced during delay and not to prove that certain cohorts of patients experienced stronger negative emotions than others.

The American College of Surgeons defines elective surgery as any procedure that, if delayed longer than 4 weeks, would not cause harm to the patient and ultimately worsen their outcome [30]. More than one-third of patients in our study felt that TJA should not be categorized as elective, and indeed, greater than 75% of patients reported a negative effect of the delay. Given that patients in the current cohort experienced anxiety and progression of pain during the delay, it is not surprising that patients would feel their surgery is not elective. As previously outlined, significant delays in surgery have major impacts on quality of life and outcomes [14,22]. Nearly 10% of patients in our cohort stated they would have risked contracting the COVID-19 virus to have their arthritis pain treated. While this may be extreme when considering the massive loss of life and negative effects our country has experienced secondary to the pandemic, it highlights the extreme pain and anxiety these patients often experience in the final months before the surgery. In addition, in light of the average age of the patients in the current cohort and the propensity for COVID-19 to infect older patients (and ultimately cause higher morbidity and mortality in this group), 10% is strikingly high. These findings are eye opening. One would not consider a TJA urgent or emergent in the same sense one would consider a coronary artery bypass graft for coronary artery disease or a femoral nail in a traumatized patient. However, the present findings reveal that delay in hip and knee arthroplasty is viewed by patients as more urgent than other elective surgeries that do not have as profound an impact on quality of life and well-being.

Conclusions

Patients who experience pain in the setting of hip and knee arthritis often wait for joint replacement as a last resort, feel a sense of urgency once it is scheduled, and no longer think of it as elective. As such, delay of scheduled TJA is associated with severe pain and anxiety. Therefore, communication and the strength of the doctor-patient relationship are of key importance during times of crisis or other events that result in delay of surgery.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: S. Odum is a paid consultant for American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and is a board member in or made committee appointments for LSRS Research Committee, NASS Value Committee, and AJRR Data Committee. K. A. Fehring received IP royalties, research support, and other financial or material support from and a paid consultant and presenter or speaker for DePuy, A Johnson & Johnson Company, and is a board or committee member in the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons and the Knee Society. B. D. Springer received royalties from Stryker and Osteoremedies; is a paid consultant for Stryker and ConvaTec; and is a board member in or made committee appointments for AJRR, ICJR, and AAHKS. J. E. Otero received research support from and is a paid consultant for DePuy, A Johnson & Johnson Company, and is a board member in the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Guy D.K., Bosco J.A. AAOS; 2020. AAOS guidelines for elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.aaos.org/about/covid-19-information-for-our-members/aaos-guidelines-for-elective-surgery/ Available at: [accessed 23.02.21] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedard N.A., Elkins J.M., Brown T.S. Effect of COVID-19 on hip and knee arthroplasty surgical volume in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7):S45. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvizi J., Gehrke T., Krueger C.A. Resuming elective orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidelines developed by the international consensus group (ICM) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(14):1205. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachmeier C.J.M., March L.M., Cross M.J. A comparison of outcomes in osteoarthritis patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2001;9(2):137. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris W.H., Sledge C.B. Total hip and total knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(12):801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009203231206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones C.A., Voaklander D.C., Johnston D.W.C., Suarez-Almazor M.E. Health related quality of life outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasties in a community based population. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(7):1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostendorf M., Buskens E., Van Stel H. Waiting for total hip arthroplasty: avoidable loss in quality time and preventable deterioration. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(3):302. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahon J.L., Bourne R.B., Rorabeck C.H., Feeny D.H., Stitt L., Webster-Bogaert S. Health-related quality of life and mobility of patients awaiting elective total hip arthroplasty: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2002;167(10):1115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garbuz D.S., Xu M., Duncan C.P., Masri B.A., Sobolev B. Delays worsen quality of life outcome of primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:79. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000203477.19421.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CMS releases recommendations on adult elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures during COVID-19 response | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental Available at: [accessed 20.08.20]

- 13.Patten S.B., Williams J.V.A., Wang J.L. Mental disorders in a population sample with musculoskeletal disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirvonen J., Blom M., Tuominen U. Health-related quality of life in patients waiting for major joint replacement. A comparison between patients and population controls. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caracciolo B., Giaquinto S. Self-perceived distress and self-perceived functional recovery after recent total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(2):177. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickens C., McGowan L., Clark-Carter D., Creed F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(1):52. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood T.J., Thornley P., Petruccelli D., Kabali C., Winemaker M., de Beer J. Preoperative predictors of pain catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(12):2750. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto P.R., McIntyre T., Ferrero R., Almeida A., Araújo-Soares V. Risk factors for moderate and severe persistent pain in patients undergoing total knee and hip arthroplasty: a prospective predictive study. PLoS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirschmann M.T., Testa E., Amsler F., Friederich N.F. The unhappy total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patient: higher WOMAC and lower KSS in depressed patients prior and after TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(10):2405. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2409-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lingard E.A., Riddle D.L. Impact of psychological distress on pain and function following knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1161. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown T.S., Bedard N.A., Rojas E.O. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled hip and knee arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7S) doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackerman I.N., Bennell K.L., Osborne R.H. Decline in Health-Related Quality of Life reported by more than half of those waiting for joint replacement surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axelrod D.A., Goold S.D. Maintaining trust in the surgeon-patient relationship: challenges for the new millennium. Arch Surg. 2000;135(1):55. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day M.A., Anthony C.A., Bedard N.A. Increasing perioperative communication with automated mobile phone messaging in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(1):19. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodhi N., Mont M.A. Does patient experience after a total knee arthroplasty predict readmission? J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(11):2573. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kee J.R., Edwards P.K., Barnes C.L., Foster S.E., Mears S.C. After-hours calls in a joint replacement practice. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(7):1303. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hällfors E., Saku S.A., Mäkinen T.J., Madanat R. A consultation phone service for patients with total joint arthroplasty may reduce unnecessary emergency department visits. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):650. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters M., Crocker H., Jenkinson C., Doll H., Fitzpatrick R. The routine collection of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for long-term conditions in primary care: a cohort survey. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howard J.S., Toonstra J.L., Meade A.R., Whale Conley C.E., Mattacola C.G. Feasibility of conducting a web-based survey of patient-reported outcomes and rehabilitation progress. Digit Heal. 2016;2 doi: 10.1177/2055207616644844. 205520761664484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.COVID-19: executive orders by state on dental, medical, and surgical procedures. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/legislative-regulatory/executive-orders Available at: [accessed 04.08.20]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.