Abstract

Graft function and patient survival are traditionally the most used parameters to assess the objective benefits of kidney transplantation. Monitoring graft function, along with therapeutic drug concentrations and transplant complications, comprises the essence of outpatient management in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). However, the patient’s perspective is not always included in this process. Patients’ perspectives on their health after kidney transplantation, albeit subjective, are increasingly acknowledged as valuable healthcare outcomes and should be considered in order to provide patient-centred healthcare. Such outcomes are known as patient-reported outcomes (PROs; e.g. health-related quality of life and symptom burden) and are captured using PRO measures (PROMs). So far, PROMs have not been routinely used in clinical care for KTRs. In this review we will introduce PROMs and their potential application and value in the field of kidney transplantation, describe commonly used PROMs in KTRs and discuss structural PROMs implementation into kidney transplantation care.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, kidney transplantation, medication side effects, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), symptom burden

INTRODUCTION

In the past 60 years, kidney transplantation has been established as the preferred renal replacement therapy for most patients with end-stage kidney disease [1]. Many studies have shown its survival benefits compared with dialysis [1–3]. However, in an era where patient-centred healthcare is continuously gaining importance, patients’ perspectives about their health should be taken into account in addition to clinical outcomes to understand the merit of treatments and to guide treatment decisions. Such perspectives, captured in patient-reported outcomes (PROs), can be structurally measured by employing validated PRO measures (PROMs) [4]. Studies have shown that PROMs can improve healthcare in patients with chronic conditions such as cancer [5, 6]. In a recent nationwide Dutch study conducted by our research group, PROMs were implemented into standard dialysis care to routinely measure health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and symptom burden [7]. In kidney transplantation, PROs have been advocated as core outcomes in research by the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology initiative [8]. However, PROMs have not yet been widely used in clinical care for kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). To raise awareness of the clinical use of PROMs in kidney transplantation care, we will describe potential applications and benefits of PROMs in clinical practice, introduce commonly used PROMs in kidney transplant research and describe an initiative to implement PROMs in incident Dutch KTRs.

GENERAL CONCEPT: PROMs

PROMs are validated questionnaires to measure patients’ appraisal of their health and functioning that can either be generic or disease-specific. Generic PROMs are not specific to any particular disease or condition. Therefore generic PROMs are suitable for use among patients with multimorbid conditions and can be used in different populations to facilitate the comparison of outcomes between patient groups. A disadvantage is that generic PROMs do not necessarily cover the prevalent health issues specific to a condition of interest and might include less-specific questions. Consequently they may be less sensitive to detect important changes in outcomes when administrated in specific patient groups. Disease-specific PROMs focus on a specific disease or treatment and are more suitable to detect disease-specific changes in a particular patient group and can provide valuable information for targeted interventions. Generic and disease-specific PROMs are often combined to map all outcomes of interest [4, 9–11]. For example, in the aforementioned nationwide study in the Dutch dialysis population, a generic PROM [the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12)] is used to measure HRQOL and a disease-specific PROM [the Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI)] is used to assess symptom burden [7]. To date, a variety of PROMs have been developed to measure different PROs, including HRQOL, symptom burden, illness perceptions, functional status and health behaviours [4].

POTENTIAL BENEFITS OF PROMS FOR KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION CARE

To facilitate patient management and improve outcomes

Due to the immunosuppressive treatment and its side effects, KTRs experience a high symptom burden and compromised levels of HRQOL [12, 13]. When ignored, they can eventually influence graft and patient survival [14, 15]. The literature suggests that underdiagnosis and undertreatment of symptoms is a common problem in patients treated with dialysis and in KTRs [16–19]. For example, a single-centre audit of depression screening in a UK outpatient clinic revealed underdetection of depressive symptoms among KTRs (screening rate 13.8%, prevalence of depressive symptoms 22.4%) [18]. In a survey among nephrologists, 96% of the respondents only addressed sexual dysfunction—another common symptom among KTRs—during consultations in less than half of their transplant patients, with the biggest barrier being that patients did not express such concerns spontaneously [19]. The implementation of PROMs can complement the existing laboratory and radiological measurements, thereby enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s health [20]. Table 1 lists some of the current evidence on the benefits of PROMs regarding the management of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Results from randomized trials have echoed the clinical benefits of PROMs for patient management, showing a positive association between symptom screening using PROMs and improved patient survival and HRQOL compared with standard care in cancer patients [26, 27]. Routinely measured PROs also have prognostic value, which allows early adjustment in the treatment strategy to achieve better health outcomes in patients. In a recent post hoc analysis of trial data, KTRs with ‘always good’ and ‘poor-to-improved’ HRQOL trajectories within the first 3 years after transplantation had a similar risk of graft failure, while the risk in the subgroups with ‘always fair’ and ‘always poor’ HRQOL was 4- and 19-fold higher, respectively, compared with their counterparts with ‘always good’ HRQOL [15]. Such information can be used to identify high-risk patients and consequently modify treatment strategies or provide additional support. Furthermore, PROMs have been recommended to monitor adherence to immunosuppressants, a vital modifiable risk factor for graft failure in KTRs, combined with laboratory tests [28]. After identification of non-adherent patients by means of validated PROMs, active interventions (e.g. establishing a reminder system) can be used to improve medication adherence [29]. Finally, it is important to note that, contrary to the concern about inadequate time in the consultation room, discussing PROs with patients does not necessarily prolong the clinic visit [30].

Table 1.

Benefits and necessity of PROMs identified in nephrology care

| References | Study design | Study population | Identified benefits or necessity of PROMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evans et al. [20]a | A multicentre, longitudinal, mixed-methods study | Patient on haemodialysis and health professionals |

Facilitate standardized symptom screening Improve awareness of symptoms in patients and health professionals Empower patients to raise questions with health professionals |

| Aiyegbusi et al. [21]a |

A single-centre qualitative study |

Patients with Stage 4 or 5 not on dialysis and health professionals |

Facilitate patient and health professional communication Allow timely identification of otherwise neglected health problems Facilitate self-management in patients and potentially reduce clinical visits Allow health professionals to address health problems prioritized by patients |

| Schick-Makaroff et al. [22]a | A multicentre qualitative study | Patients on dialysis and health professionals |

Allow intervention for identified health problems Direct interdisciplinary follow-up or further assessment |

| Morton et al. [23]a | A cross-sectional survey study | Heath professionals from renal units | Inform clinical care |

| Schick-Makaroff and Molzahn [24]a | A multicentre, longitudinal, mixed-methods study | Patients on dialysis and health professionals |

Allow health professionals to address health problems prioritized by patients Direct interdisciplinary follow-up Improve awareness of health problems in patients Bring positive changes of medical care to patients |

| Verberne et al. [25] | International consensus workshop | Kidney disease experts and patient representatives | PROMs identified as one of the standard set of value-based outcome measures |

| Tong et al. [8] | International consensus workshop | Kidney disease experts and patient representatives | PROs (e.g. life participation) recommended as an essential component of the core outcome set |

Most important qualitative and quantitative studies that have investigated the impact of PROMs in patients with kidney disease and/or relevant health professionals.

To improve patient participation

Active patient participation in their care delivery is important for KTRs, as they have chronic conditions with a high treatment burden (e.g. taking multiple medications to prevent rejection and for comorbidities and complications caused by chronic immunosuppression). A recent qualitative study investigating determinants for patient participation showed that, among other factors, patients’ knowledge and understanding of their health are essential for patient participation. Another important determinant is the availability of tools and routines (e.g. PROMs and protocols) that healthcare professionals can use to encourage patients to be more actively involved in their own healthcare [31]. Notably, PROMs implementation provides the opportunity to improve patient participation for both patients and professionals. Completion of PROMs can prompt patients’ understanding of their medical conditions (i.e. illness insight) and facilitate patient–provider communication, thus forming a basis for better self-management and engagement in the process of shared (clinical) decision-making [20, 32, 33]. See Table 1 for the supportive evidence of PROMs used in nephrology care.

To evaluate the value of transplantation

Patient survival and graft function are widely used to evaluate kidney transplant care. However, despite a well-functioning graft, KTRs can experience unsatisfied and impaired levels of HRQOL [8, 34]. Therefore it is essential to assess outcomes reported by patients. Furthermore, due to the growing number of elderly patients accepted for kidney transplantation and the increased use of extended-criteria donor kidneys in recent decades [35, 36], the survival benefit of transplantation may not be present in all subgroups of KTRs. A recent national Dutch registry study pointed out that the 5-year survival of elderly KTRs with an elderly deceased donor, especially after cardiac death, was comparable to that of dialysis patients on the waiting list [37]. Notably, elderly recipients reported a better HRQOL after transplantation in another study [38]. Such findings stress the need for healthcare professionals to look beyond clinical outcomes to evaluate the benefits of kidney transplantation. In the emerging value-based healthcare theory, which emphasizes patient-relevant outcomes relative to the medical cost, PROMs are instrumental in assessing the overall value of care by incorporating the patient’s voice [39]. According to the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) CKD working group, a PROM to measure HRQOL is part of the recommended standard set of outcomes for healthcare along with patient survival, disease burden (i.e. hospitalization and cardiovascular events) and treatment modality-specific outcomes (i.e. graft function, graft survival, acute rejection and malignancies) in KTRs [25].

To guide decision- and policy-making

PROs are important outcomes that should be taken into account to guide shared decision-making. For instance, doctors and patients can choose the most suitable renal replacement therapy not only based on patient survival, but also HRQOL. Furthermore, stakeholders within the transplant community have argued that the current organ allocation policy that values longevity is outdated, and a comprehensive evaluation involving post-transplant HRQOL, functional status and cost is more relevant [40]. Prediction models comprising both clinical outcomes and PROs can be developed to facilitate the above process. Despite the fact that PROs have been adopted as an outcome in kidney transplant research, large longitudinal studies in incident patients with a long-term follow-up are still lacking to support the use of aggregated PROMs information in clinical practice.

PROMS FOR KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION

In the field of CKD and kidney transplantation, different international working groups have emphasized the importance of PROMs in clinical practice [25, 41]. As the most frequently measured PRO, many PROMs have been developed or validated to measure HRQOL, including those for KTRs. In this review we will narratively introduce generic and disease-specific PROMs for HRQOL and PROMs for symptom burden—a main determinant of HRQOL.

PROMs for HRQOL in kidney transplantation

A working group with geographical diversity was assembled in 2016 by ICHOM to select a set of PROMs for patients with CKD on conservative treatment, on dialysis and after kidney transplantation. The invited healthcare professionals and patient representatives concluded that the following six HROQL domains were required to sufficiently capture HRQOL: general HRQOL, physical function, daily activity, pain, fatigue and depression. In total, three generic PROMs were recommended by the working group to measure HRQOL: the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), the RAND 36-item Health Survey (RAND-36) and a combination of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)–Global Health and the 29-item PROMIS (PROMIS-29) [25]. In a European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) experts consensus meeting involving 45 European renal registries, the SF-12 was selected as the preferred generic PROM to routinely measure HRQOL in practice due to its efficiency [41]. The SF-12 was developed as a shorter version of the SF-36. In a reliability and validity study, the SF-12 reproduced similar physical and mental HROQL summary scores as the SF-36 but less-comparable scores for the separate HRQOL domains [42]. Finally, the validated EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) was recommended by the same ERA-EDTA consensus meeting to assess health status and to study the cost value, as it provides the utility data required for such analysis [41].

The ICHOM working group also identified two kidney disease–specific PROMs to measure HRQOL, the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF) and its shorter version, the 36-item Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-36) survey. Even though both PROMs cover the required HRQOL domains, they were not recommended by ICHOM to measure HRQOL because they also contain kidney disease–specific domains (e.g. symptoms, the burden of kidney disease and effects of kidney disease) [25, 43, 44]. However, the KDQOL-36 was recommended by the ERA-EDTA experts consensus meeting to routinely measure disease-specific HRQOL [37]. Finally, there are also validated kidney transplant–specific HRQOL PROMs, including the Kidney Transplant Questionnaire (KTQ) [45] and the End-Stage Renal Disease Symptom Checklist–Transplantation Module (ESRD-SCL-TM) [46]. Table 2 provides detailed information of the aforementioned generic, disease-specific and kidney transplantation–specific PROMs for HRQOL.

Table 2.

Generic, kidney disease–specific and kidney transplantation–specific HRQOL PROMs

| HRQOL PROMs | Target population | Number of items | Time to complete (min) | Licensing | Domain coverage | HRQOL scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMs recommended by the ICHOM CKD Working Group | ||||||

| PROMIS Global Health [47]a | Non-specific | 10 | 5 | None | Overall physical health, mental health, social health, pain, fatigue and overall perceived HRQOL | Summary score for mental and physical HRQOL |

| PROMIS-29 [48]a | Non-specific | 29 | 10 | None | Depression, anxiety, physical function, pain interference, fatigue, sleep disturbance and ability to participate in social roles and activities | Domain scores |

| SF-36 [42] | Non-specific | 36 | 10 | License fee | Vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning and mental health | Domain scores and summary score for mental and physical HRQOL |

| RAND-36 [49] | Non-specific | 36 | 10 | None | Identical to SF-36 | Identical to SF-36 |

| PROMs recommended by the ERA-EDTA consensus meeting | ||||||

| SF-12 [42] | Non-specific | 12 | 5 | License fee | Identical to SF-36 | Summary score for mental and physical HRQOL |

| EQ-5D [50] | Non-specific | 6 | 5 | License fee | Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression and a VAS for global health | Utility score and EQ-VAS score. HRQOL score |

| KDQOL-36 [44] | Kidney disease | 36 | 15 | None | SF-12 and disease-specific domains: symptoms, burden of kidney disease and effects of kidney disease | Domain scores and summary score for mental and physical HRQOL |

| Commonly used kidney transplantation-specific PROMs | ||||||

| KTQ [45] | Kidney transplantation | 25 | 15 | None | Physical symptoms, fatigue, uncertainty/fear, appearance and emotions | Domain scores |

| ESRD-SCL [46] | Kidney transplantation | 43 | 10 | None | Physical capacity, cognitive capacity, cardiac and renal dysfunction, side effects of corticosteroids, increased growth of gum and hair and transplantation-associated psychological distress | Domain scores and a global HRQOL score |

The two questionnaires should be used in combination to cover all six domains (general HRQOL, physical function, daily activity, pain, fatigue and depression) prioritized by the working group.

The first four items for each questionnaire were adapted from a published article [35].

VAS, visual analogue scale.

PROMs for symptom burden in kidney transplantation

KTRs have a high symptom burden [13]. The ERA-EDTA experts consensus meeting emphasized the importance of monitoring patients’ symptom experiences, although no agreement was reached about a preferred PROM to measure symptom burden [41]. The ICHOM working group did not recommend a PROM for symptom burden either, but did encourage healthcare professionals to measure symptom experiences [25]. There are several suitable and validated PROMs to measure symptom burden in KTRs that will be discussed below.

The Modified Transplant Symptom Occurrence and Symptom Distress Scale–59 Items Revised (MTSOSD-59R) aims explicitly to measure the side effects of immunosuppressive therapy and is suitable for mapping symptom burden in KTRs. This 59-item checklist is an updated revision of the MTSOSD-45, complemented with side effects of the newer generation of immunosuppressants such as tacrolimus, mycophenolate-based formulations, everolimus and belatacept. The MTSOSD-59R measures both symptom occurrence and symptom distress [51].

The Gastrointestinal Rating Scale (GSRS) is a PROM that covers gastrointestinal symptoms due to the immunosuppressive regime. Five symptom clusters measured by this 15-item PROM are reflux, abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhoea and constipation [52]. Compared with the two previously mentioned PROMs, the GSRS has a narrower symptom spectrum, as it only focuses on symptoms related to the digestive system.

The revised version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) is a PROM primarily designed to measure symptom burden in patients receiving palliative care. It has been validated in both dialysis patients and KTRs, which enables its potential use in longitudinal follow-up across different renal replacement therapies. This PROM measures the severity of the following nine symptoms: pain, tiredness, nausea, shortness of breath, lack of appetite, drowsiness, depression, anxiety and general well-being. It generates three summary scores: the global, physical and emotional symptom scores [53].

Notably, some of the previously mentioned PROMs to measure HRQOL also include items measuring symptom experience. The ESRD-SCL-TM contains specific items assessing the side effects of corticosteroids (five items), increased gum growth and body hair (five items) and transplantation-related psychological discomfort (eight items) [46]. However, it only covers the side effects of commonly used immunosuppressants from two decades ago. The KTQ and the KDQOL-36 measure 6 and 12 symptoms, respectively [43–45]. Finally, there are also commonly used PROMs that measure only one specific symptom in KTRs. For example, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [54] is used to measure sleep disorders and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [55] are used to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms. Table 3 shows detailed information of the aforementioned PROMs for measuring symptom burden.

Table 3.

Validated symptom PROMs for KTRs

| HRQOL PROMs | Target population | Number of items | Time to complete (min) | Licensing | Symptom scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMs to measure symptom/symptom burden | |||||

| MTSOSD-59R [51] | Under immunosuppressive treatment | 59 | 10–15a | Noneb | Symptom occurrence and symptom distress |

| MTSOSD-45 [51] | Under immunosuppressive treatment | 45 | 10a | None | Symptom occurrence and symptom distress |

| GSRS [52] | Under immunosuppressive treatment | 15 | 5a | None | Scores for each symptom cluster (reflux, abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhoea and constipation) |

| ESAS-r [53] | Kidney disease | 9 | 5a | None | Global, physical and emotional symptom scores |

| HRQOL PROMs with domains to measure symptoms | |||||

| KDQOL-SF [44] | Kidney disease | 82 (12c) | 15 | None | Symptom score |

| KDQOL-36 [44] | Kidney disease | 36 (6c) | 25 | None | Symptom score |

| ESRD-SCL [46] | Kidney transplantation | 43 (18c) | 10 | None | Domain scores (side effect is corticosteroids, increased growth of gum and hair, transplantation-associated psychological distress) |

| Examples of PROMs for one specific symptom | |||||

| PSQI [54] | Non-specific | 19 | 5–10 | License fee | Global PSQI score and domain scores (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction) |

| HADS [55] | Non-specific | 14 | 2–5 | License fee | Global HADS score |

| BDI [55] | Non-specific | 21 | 2–5 | License fee | Global BDI score |

Time indication to complete the PROM was extrapolated based on our experience with the DSI, a 30-item PROM to measure both symptom occurrence and symptom distress.

Permission and conditions to use the Basel Assessment of Adherence to Immunosuppressive Medication Scalecan be obtained from sabina.degeest@unibas.ch.

Number of items to measure symptoms.

IMPLEMENTATION OF PROMS IN ROUTINE CARE

Despite the not yet available evidence of the effect of PROMs implementation on actual health outcomes (e.g. HRQOL or survival) in patients receiving dialysis treatment or KTRs, a number of studies have reported positive findings with regard to other outcomes (see Table 1). In recent years there have been increasing attempts to implement PROMs in nephrology care, mostly in patients with CKD or patients treated with dialysis [7, 20, 56, 57]. Implementation of PROMs in clinical care is far more complicated than handing out a questionnaire to patients. Multiple factors can hinder the implementation and diminish the value of PROMs. For healthcare professionals, insufficient knowledge of PROMs, limited time in the consultation room, failure to integrate PROMs in the standard workflow, the absence of standard protocols to improve PROs and a lack of administrative support (e.g. a lack of staff and electronic system) can discourage the use of PROMs [58, 59]. For patients, the major barriers include the inability to complete PROMs due to poor health status or difficulties using an electronic device, perceived low value of PROMs and the amount of time required to fill out PROMs [59]. Therefore, efforts during the design phase and the preparation phase are essential for the successful implementation of PROMs in clinical practice. In these phases, it is important to take at least the following steps: select suitable PROMs, decide on how to administrate the PROMs, develop an electronic system to facilitate its use during consultations and train professionals how to interpret and use the PROM results [60].

When it comes to longitudinally monitoring PROs, the response rate also poses a challenge. Considerable variation and a downward trend in response rate for PROMs are often encountered in registry-based studies [61]. In the Dutch dialysis PROMs study, the response rate also varied greatly among the dialysis centres (ranging from 6 to 70%) and the response rate declined over time (28% at baseline compared with 21% at 3 and 6 months). The variation between medical centres was most likely related to differences in infrastructure and logistical approaches (i.e. providing tablets) and engagement of health professionals. The relatively low baseline response rate is in line with a previous PROMs study in dialysis patients in Scotland [62] and could be seen as an indication to improve stakeholder engagement (e.g. increase awareness of PROMs in health professionals and patients) [7]. With regard to the decline in response rate over time, potential explanations include patients forget to complete the PROMs, patients have a poor health status, patients get insufficient support when completing the PROMs, patients have (unrealistically) high expectations of PROMs implementation that may negatively influence its perceived value and health professionals do not discuss and/or (adequately) respond to the PROM results (e.g. due to a lack of efficient treatment or multidisciplinary care) [20, 63, 64].

Previous studies suggest general measures to improve the response rate, including sending reminders to patients, providing PROMs in different formats (digital and paper versions) and languages and facilitating PROM completion during the hospital visit [61, 65]. In the Dutch dialysis PROMs study, 41% of the responders received support to complete the PROMs (i.e. reading the questions, translating questions and filling in patients’ answers on their behalf) and providing tablets for patients to complete the PROMs during dialysis was associated with a higher response rate [7]. Finally, building realistic expectations of PROM use in patients and health professionals and providing an adequate resource to respond to PROM results should also be addressed. However, from a value-based perspective, one could ask oneself the question of whether maximal effort should be made to improve the response rate, as the costs will rise along with the increased effort [65].

Implementation of PROMs in Dutch healthcare for KTRs

Currently PROMs (i.e. the SF-12 as generic a PROM to measure HRQOL and the DSI as a disease-specific PROM to measure symptom burden) are implemented in all Dutch dialysis centres to routinely measure PROs over time and to improve the health outcomes of dialysis patients [7]. Following this initiative by our research group, we aimed to take similar steps in KTRs by means PROs: Input of Valuable Endpoints (POSITIVE) study. To enable successful PROMs implementation in Dutch KTRs, several of the aforementioned factors were taken into account and will be discussed below.

First, the PROMs were carefully selected for KTRs with regard to the content and the time it takes to fill in the PROMs. To enable comparison with the dialysis population and to ensure longitudinal follow-up of patients across different CKD stages and across treatment modalities, we harmonized the KTR PROMs with those administrated in the dialysis population. Thus the SF-12 and the DSI were selected for the POSITIVE study to measure generic HRQOL and CKD symptom burden. A recent mixed-method study has shown positive results in using the DSI to measure symptom burden in prevalent KTRs [66]. In addition to these two PROMs, the MTSOSD-59R was included in the POSITIVE study as a treatment-specific PROM for chronic immunosuppression to capture the full range of symptoms experienced by KTRs (i.e. CKD symptoms and medication side effects). Taken together, the Dutch kidney transplantation PROMs can be filled out in ∼15 min (5 min for the SF-12 [25], 5 min for the DSI [66] and 5 min for the complementary items from the MTSOSD-59R). Based on our experience, the time to read a PROM report is ∼1 min (for both patients and health professionals) and the time to discuss PROM results depends on the number of health issues that need to be addressed.

Second, to facilitate the use of PROMs by patients, digitized and paper versions of the PROMs are available and will be provided according to the patient’s preference. PROMs are also available in different languages (i.e. Dutch, but also English). All participating patients are asked to fill out the questionnaire at transplantation (during the hospitalization for transplantation); at 6 weeks, 6 months and 1 year after kidney transplantation; and annually thereafter. A reminder is sent to patients if the PROMs are not filled 1 week before the scheduled time point.

Third, to encourage the clinical use of PROMs by healthcare professionals, an electronic module has been developed so that the PROM report is easily accessible for nephrologists in their local hospital system. For medical centres, such measures to facilitate PROMS implementation are endorsed by studies in cancer patients [67, 68]. Continuous attention is also being paid (e.g. by means of presentations) to increasing professionals’ awareness and knowledge of PROMs and PROM results (e.g. the e-module, how to interpret the results, etc.).

Fourth, to facilitate the discussion about PROs in the consultation room, a PROM report is generated directly after PROM completion and is accessible for patients and their doctors. The report contains information about the patient’s HRQOL and symptom burden scores. Similar to the PROM report used in the Dutch dialysis population (https://www.nefrovisie.nl/proms-faq/), HRQOL scores are presented with reference values (e.g. the Dutch general population) in bar charts and the response to each HRQOL and symptom item is categorized into three levels based on the severity and coloured accordingly: red indicates the highest burden caused by that specific item, orange indicates a moderate burden and green indicates the lowest burden. The graphical presentation and classification of PROs are believed to promote interpretability and clinical actionability for providers [69, 70]. The report is filled out prior to consultation and discussed at the upcoming clinical visit. In case of an alarming report (e.g. extremely low HRQOL or extremely high symptom burden), an extra telephone or video consultation can be arranged before the scheduled visit.

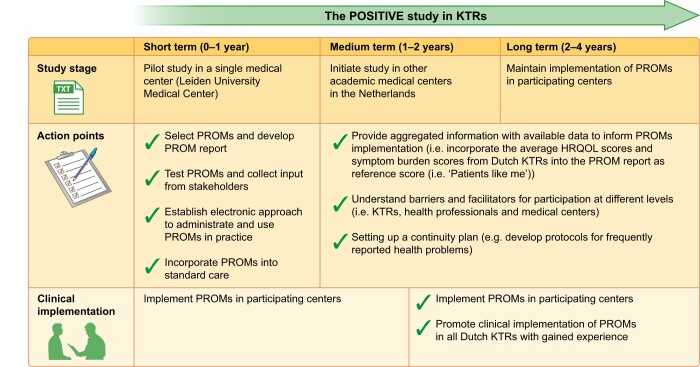

This ongoing POSITIVE study showcases the first steps to incorporate PROMs in kidney transplantation care and also the next steps in the implementation of PROMs into Dutch nephrology care. Future studies are needed to investigate the determinants for successful PROMs implementation in KTRs. Figure 1 briefly illustrates the road map for this study.

FIGURE 1.

Road map of the POSITIVE study.

CONCLUSION

PROMs are potentially powerful tools to assess PROs and improve the value of healthcare at an individual and population level. A number of PROMs to measure HRQOL and symptom burden are available for KTRs, although not yet commonly used in clinical practice. To the best of our knowledge, there is no agreement on a preferred HRQOL or symptom PROM for routine assessment in KTRs. The decision to use a specific PROM should depend on the purpose and the population. To implement PROMs in clinical practice, sufficient preparation at an early stage and sufficient effort to maintain the response rate are necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Chiesi Pharmaceuticals BV and Astellas Pharma for providing financial support for the POSITIVE study. They had no role in the writing of and decision to submit this article. We thank all patients participating in the POSITIVE study. We are also grateful for the support of the staff and students of participating centres, in particular, Denise Veltkamp and Inger Kunnekes.

FUNDING

Y.W. is supported by a scholarship from the Chinese Scholarship Council (201706270194).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.W. was responsible for writing the article. Y.M., F.D. and A.V.R. were responsible for supervision or mentorship. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, accepts personal accountability for their contributions and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy and integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This article has not been published previously in whole or in part.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

There are no new data associated with this review.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G. et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 2011; 11: 2093–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoo KD, Kim CT, Kim MH. et al. Superior outcomes of kidney transplantation compared with dialysis: an optimal matched analysis of a national population-based cohort study between 2005 and 2008 in Korea. Medicine 2016; 95: e4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaballo MA, Canney M, O’Kelly P. et al. A comparative analysis of survival of patients on dialysis and after kidney transplantation. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 389–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weldring T, Smith SMS.. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights 2013; 6: 61–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Egdom LSE, Oemrawsingh A, Verweij LM. et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in clinical breast cancer care: a systematic review. Value Health 2019; 22: 1197–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marcel GM, Olde Rikkert PJW, Schoon Y. et al. Using patient reported outcomes measures to promote integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2018; 18: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Willik EM, Hemmelder MH, Bart HAJ. et al. Routinely measuring symptom burden and health-related quality of life in dialysis patients: first results from the Dutch registry of patient-reported outcome measures. Clin Kidney J 2020; 10.1093/ckj/sfz192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tong A, Gill J, Budde K. et al. Toward establishing core outcome domains for trials in kidney transplantation: report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology–Kidney Transplantation consensus workshops. Transplantation 2017; 101: 1887–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kyte DG, Calvert M, van der Wees PJ. et al. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy 2015; 101: 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy M, Hollinghurst S, Salisbury C.. Identification, description and appraisal of generic PROMs for primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2018; 19: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Snyder CF, Jensen RE, Segal JB. et al. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs): putting the patient perspective in patient-centered outcomes research. Med Care 2013; 51(8 Suppl 3): S73–S79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mourad G, Serre JE, Alméras C. et al. Infectious and neoplasic complications after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Ther 2016; 12: 468–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Afshar M, Rebollo-Mesa I, Murphy E. et al. Symptom burden and associated factors in renal transplant patients in the U.K. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 44: 229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Griva K, Davenport A, Newman SP.. Health-related quality of life and long-term survival and graft failure in kidney transplantation: a 12-year follow-up study. Transplantation 2013; 95: 740–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Purnajo I, Beaumont JL, Polinsky M. et al. Trajectories of health-related quality of life among renal transplant patients associated with graft failure and symptom distress: analysis of the BENEFIT and BENEFIT-EXT trials. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 1650–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK. et al. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2: 960–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Claxton RN, Blackhall L, Weisbord SD. et al. Undertreatment of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39: 211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spencer BW, Chilcot J, Farrington K.. Still sad after successful renal transplantation: are we failing to recognise depression? An audit of depression screening in renal graft recipients. Nephron Clin Pract 2011; 117: c106– c1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Ek GF, Krouwel EM, Nicolai MP. et al. Discussing sexual dysfunction with chronic kidney disease patients: practice patterns in the office of the nephrologist. J Sex Med 2015; 12: 2350–2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans JM, Glazer A, Lum R. et al. Implementing a patient-reported outcome measure for hemodialysis patients in routine clinical care: perspectives of patients and providers on ESAS-r:renal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1299–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aiyegbusi OL, Kyte D, Cockwell P. et al. Patient and clinician perspectives on electronic patient-reported outcome measures in the management of advanced CKD: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 74: 167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schick-Makaroff K, Tate K, Molzahn A.. Use of electronic patient reported outcomes in clinical nephrology practice: a qualitative pilot study. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2019; 6: 205435811987945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morton RL, Lioufas N, Dansie K. et al. Use of patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures in renal units in Australia and New Zealand: a cross-sectional survey study. Nephrology 2020; 25: 14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schick-Makaroff K, Molzahn AE.. Evaluation of real-time use of electronic patient-reported outcome data by nurses with patients in home dialysis clinics. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verberne WR, Das-Gupta Z, Allegretti AS. et al. Development of an international standard set of value-based outcome measures for patients with chronic kidney disease: a report of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Mmeasurement (ICHOM) CKD working group. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 73: 372–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG. et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 557–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC. et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017; 318: 197–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neuberger JM, Bechstein WO, Kuypers DRJ. et al. Practical recommendations for long-term management of modifiable risks in kidney and liver transplant recipients: a guidance report and clinical checklist by the Consensus on Managing Modifiable Risk in Transplantation (COMMIT) group. Transplantation 2017; 101(4 Suppl 2): S1–S56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen TMU, Caze AL, Cottrell N.. Validated adherence scales used in a measurement-guided medication management approach to target and tailor a medication adherence intervention: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e013375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berry DL, Blumenstein BA, Halpenny B. et al. Enhancing patient-provider communication with the electronic self-report assessment for cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1029–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schildmeijer K, Nilsen P, Ericsson C. et al. Determinants of patient participation for safer care: a qualitative study of physicians’ experiences and perceptions. Health Sci Rep 2018; 1: e87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greenhalgh J, Gooding K, Gibbons E. et al. How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2018; 2: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popoola J, Greene H, Kyegombe M. et al. Patient involvement in selection of immunosuppressive regimen following transplantation. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014; 8: 1705–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Habwe VQ. Posttransplantation quality of life: more than graft function. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(4 Suppl 2): S98– S–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, et al. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2007; 83: 1069–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Metzger RA, Delmonico FL, Feng S. et al. Expanded criteria donors for kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 2003; 3: 114–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peters-Sengers H, Berger SP, Heemskerk MBA. et al. Stretching the limits of renal transplantation in elderly recipients of grafts from elderly deceased donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 621–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lønning K, Heldal K, Bernklev T. et al. Improved health-related quality of life in older kidney recipients 1 year after transplantation. Transplant Direct 2018; 4: e351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2477–2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Achille M, Agarwal G, Albert M et al. Current opinions in organ allocation. Am J Transplant 2018; 18: 2625–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Breckenridge K, Bekker HL, Gibbons E. et al. How to routinely collect data on patient-reported outcome and experience measures in renal registries in Europe: an expert consensus meeting. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1605–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD.. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34: 220–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL. et al. Development of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res 1994; 3: 329–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.RAND. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Instrument (KDQOL). https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/kdqol.html (date last accessed 13 April, 2020)

- 45. Chisholm-Burns MA, Erickson SR, Spivey CA et al. Concurrent validity of kidney transplant questionnaire in US renal transplant recipients. Patient Prefer Adherence 2011; 5: 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Franke GH, Reimer J, Kohnle M. et al. Quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients after successful kidney transplantation: development of the ESRD symptom checklist – transplantation module. Nephron 1999; 83: 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA. et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 873–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Craig BM, Reeve BB, Brown PM. et al. US valuation of health outcomes measured using the PROMIS-29. Value Health 2014; 17: 846–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hays RD, Morales LS.. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 2001; 33: 350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oppe M, Devlin NJ, Szende A.. EQ-5D Value Sets: Inventory, Comparative Review and User Guide. Berlin: Springer, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dobbels F, Moons P, Abraham I. et al. Measuring symptom experience of side-effects of immunosuppressive drugs: the Modified Transplant Symptom Occurrence and Distress Scale. Transplant Int 2008; 21: 764–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kleinman L, Kilburg A, Machnicki G. et al. Using GI-specific patient outcome measures in renal transplant patients: validation of the GSRS and GIQLI. Qual Life Res 2006; 15: 1223–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dano S, Pokarowski M, Liao B. et al. Evaluating symptom burden in kidney transplant recipients: validation of the revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System for kidney transplant recipients – a single-center, cross-sectional study. Transpl Int 2020; 33: 423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH. et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989; 28: 193–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Loosman WL, Siegert CEH, Korzec A. et al. Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory for use in end-stage renal disease patients. Br J Clin Psychol 2010; 49: 507–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van der Veer SN, Aresi G, Gair R.. Incorporating patient-reported symptom assessments into routine care for people with chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 2017; 10: 783–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pagels AA, Stendahl M, Evans M.. Patient-reported outcome measures as a new application in the Swedish Renal Registry: health-related quality of life through RAND-36. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 442–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nguyen H, Butow P, Dhillon HM. et al. Using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in routine head and neck cancer care: what do health professionals perceive as barriers and facilitators? J Med Image Radiat Oncol 2020; 64: 704–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nguyen H, Butow P, Dhillon HM. et al. A review of the barriers to using Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in routine cancer care. J Med Radiat Sci 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Foster A, Croot L, Brazier J. et al. The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: a systematic review of reviews. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2018; 2: 46–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang K, Eftang CN, Jakobsen RB. et al. Review of response rates over time in registry-based studies using patient-reported outcome measures. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e030808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nimmo A, Bell S, Brunton C. et al. Collection and determinants of patient reported outcome measures in haemodialysis patients in Scotland. QJM 2018; 111: 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Triplet JJ, Momoh E, Kurowicki J. et al. E-mail reminders improve completion rates of patient-reported outcome measures. JSES Open Access 2017; 1: 25–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hutchings A, Neuburger J, Grosse Frie K. et al. Factors associated with non-response in routine use of patient reported outcome measures after elective surgery in England. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10: 34–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pronk Y, Pilot P, Brinkman JM. et al. Response rate and costs for automated patient-reported outcomes collection alone compared to combined automated and manual collection. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2019; 3: 31–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. van der Willik EM, Meuleman Y, Prantl K. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures: selection of a valid questionnaire for routine symptom assessment in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease – a four-phase mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol 2019; 20: 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wu AW, White SM, Blackford AL et al.. Improving an electronic system for measuring PROs in routine oncology practice. J Cancer Surviv 2016; 10: 573–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Blackford AL, Wu AW, Snyder C.. Interpreting and acting on PRO results in clinical practice: lessons learned from the patient viewpoint system and beyond. Med Care 2019; 57(5 Suppl 1): S46–S51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Snyder C, Smith K, Holzner B et al.. Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Qual Life Res 2019; 28: 345–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brundage MD, Wu AW, Rivera YM. et al. Promoting effective use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: themes from a “Methods Tool kit” paper series. J Clin Epidemiol 2020; 122: 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no new data associated with this review.