Abstract

Plant-derived polyphenolic compounds possess diverse biological activities, including strong anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, and anti-tumorigenic activities. There is a growing interest in the development of polyphenolic compounds for preventing and treating chronic and degenerative diseases, such as cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Two neuropathological changes of AD are the appearance of neurofibrillary tangles containing tau and extracellular amyloid deposits containing amyloid-β protein (Aβ). Our laboratory and others have found that polyphenolic preparations rich in proanthocyanidins, such as grape seed extract, are capable of attenuating cognitive deterioration and reducing brain neuropathology in animal models of AD. Oligopin is a pine bark extract composed of low molecular weight proanthocyanidins oligomers (LMW-PAOs), including flavan-3-ol units such as catechin (C) and epicatechin (EC). Based on the ability of its various components to confer resilience to the onset of AD, we tested whether oligopin can specifically prevent or attenuate the progression of AD dementia preclinically. We also explored the underlying mechanism(s) through which oligopin may exert its biological activities. Oligopin inhibited oligomer formation of not only Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, but also tau in vitro. Our pharmacokinetics analysis of metabolite accumulation in vivo resulted in the identification of Me-EC-O-β-Glucuronide, Me-(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide, EC-O-β-glucuronide, and (±)-C-O-β-glucuronide in the plasma of mice. These metabolites are primarily methylated and glucuronidated C and EC conjugates. The studies conducted provide the necessary impetus to design future clinical trials with bioactive oligopin to prevent both prodromal and residual forms of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid β-peptide, polyphenols, tau

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most persistent and devastating geriatric neurodegenerative disorders, often leading to severe memory loss and functional impairment [1]. As of 2017, there were an estimated 50 million people with dementia worldwide. The prevalence of AD dramatically increases yearly, with there being nearly 10 million new cases each year. While there is currently no cure for AD, delaying its onset by even a few years would lead to a significant reduction in disease prevalence and, consequently, its burden on health care systems. As such, it is necessary to identify new treatment paradigms that not only manage AD symptoms, but that also address the underlying pathophysiological changes that contribute to the onset of the disease.

Long-recognized pathological hallmarks of AD are the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated neurofibrillary tangles, as well as the accumulation and deposition of neurotoxic amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides into extracellular Aβ plaques in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, the regions of the brain most commonly affected by these neuropathologies [2, 3]. Aβ species with varying amino and carboxy termini are generated from the ubiquitously expressed amyloid-β protein precursor through sequential proteolysis by β- and γ-secretases [4–6]. A third proteolytic enzyme, α-secretase, may reduce Aβ generation by cleaving the amyloid-β protein precursor within the Aβ peptide sequence. More recent evidence indicates that the accumulation of soluble extracellular oligomeric Aβ species in the brain, rather than the deposition of amyloid plaques per se, may be specifically related to spatial memory reference deficits in mouse models of AD [7, 8]. These deficits include the inhibition of hippocampal long-term potentiation, which is an electrophysiological feature of memory function [9], the disruption of synaptic plasticity in vivo [4], and early-onset behavioral impairment and synaptic dysfunction, which has recently been shown to accelerate the progression of AD symptoms as a result of the accumulation of soluble extracellular oligomeric Aβ peptides in the brain [10]. Most excitingly, recent experimental therapeutic evidence has indicated that neutralization of soluble extracellular Aβ oligomeric species from the brain may causally improve spatial memory function in a mouse model of AD [11]. This evidence strongly suggests that preventing the formation of Aβ peptides into soluble oligomeric species in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, rather than dissociating or preventing amyloid plaque formation and deposition, may be a more productive approach to preventing and treating AD memory dysfunction. For this reason, major efforts are presently focused on developing pharmacologic strategies that could delay the onset and/or slow the progression of Aβ-oligomerization into soluble extracellular high molecular weight species in the brain.

Plant-derived polyphenolic compounds have been shown to attenuate cognitive deterioration and reduce Aβ plaque load in animal models of AD. Previous preclinical work from our laboratory and others has demonstrated that polyphenols rich in proanthocyanidins, such as grape seed extract, may ameliorate the deleterious neuropathologies associated with AD. Indeed, clinical investigations have shown that a proanthocyanidins-rich diet improved cognitive functioning in the elderly [12, 13].

In particular, it has been shown that oligopin, a pine bark extract composed of low molecular weight proanthocyanidolic oligomers (LMW-PAOs), possesses neuroprotective properties. A primary component of LMW-PAOs includes monomeric flavan-3-ols (–)- epicatechin (EC) and (+)-catechin (C), which have been shown to mitigate the detrimental effects of oxidative stress in the brain. Thus, this study examined the effects of oligopin in both in vitro and in vivo model systems of AD with the goal of providing the scientific basis to design future clinical trials with bioactive LMW-PAOs from oligopin in AD or in subjects with mild cognitive impairment that are at high risk for developing AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins assay (PICUP)

Aβ and tau peptides were purchased from Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan) and Recombinant Peptide Technologies (LLC, GA), respectively. LMW Aβ1–42 (30–40 μM) or Aβ1–40 (40 μM) or tau peptides (50 μM) were mixed with 1 μl of 4–5 mM tris (2,2’-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) (Ru(bpy)) and 1 μl of 80–100 mM ammonium persulfate (APS) in the presence or absence of equal molar concentration of oligopin or 4-fold excess of oligopin, as previously described [14] A control protein, glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Sigma-Aldrich), was cross-linked under similar conditions. The mixture was irradiated for 1 s and quenched immediately with 10 μl of tricine sample buffer (Invitrogen) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol [14]. The reaction was then subjected to SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining (SilverXpress, Invitrogen). Aβ and tau aliquots of all samples were dispensed from same tube, it was confirmed by protein measurement that Aβ and tau of all samples was ~25 μM before applying into gel, and so, there was no difference in the amount of applied protein between lanes. The ImageJ software package was used to measure the integrated density of the bands in digital images of the gels. Crosslinking was evaluated by computing for each lane the ratios of dimer, trimer, etc. to the monomer in the same sample; this ratio is not affected by variations in gel loading.

Bioavailability, metabolism, and brain penetration of oligopin monomeric flavan-3-ol phase II metabolites

Eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats purchased from the Harlan Laboratory were placed on a polyphenol free AIN-93M diet (Dyets). Doses of oligopin (gift from Dérivés Résiniques et Terpéniques (DRT) (200 mg/kg/day) were administered to rats over a 10-day period through gavage with a plasma pharmacokinetic assessment (0–8 h) conducted on day one (single acute dose) and on day ten (acute on chronic dose). On day 11, the animals were administered a final dose of oligopin and sacrificed an hour later by an overdose of carbon dioxide. The vascular systems were perfused with cold physiological saline. The brains were harvested and placed in 0.2% ascorbic acid in saline, and stored at –80°C until analysis was performed.

The animal studies were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Basel Declaration and approved by the institutional review board at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and by the Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) prior to commencing the study.

Extraction and analysis of proanthocyanidin monomer phase II metabolites from brain tissues

C and EC metabolites were extracted from brain tissues by solid phase extraction as previously described [15, 16]. Briefly, finely diced brain tissues (~500 mg) were extracted with ice cold methanol and dried under vacuum, resolubilized in 1.5 M formic acid prior to loading onto 1 mL Oasis HLB SPE cartridges (Waters Corporation) preactivated by methanol and water. Following loading, SPE cartridges were washed with 1.5 M formic acid and 1 mL (95:5) water-methanol. Plasma was diluted in saline and loaded directly on SPE cartridges. C/EC phase II conjugated metabolites were then eluted with methanol acidified with 0.1% formic acid. The catechin fractions were vacuum dried, sonicated, and resolubilized in mobile phase prior to LC-MS analysis. Analysis of C, EC, and the metabolites from the brain were performed using an Agilent 6400 Series QQQ in multiple reaction monitoring mode using identical ionization conditions employed on the TOF with 30 eV collision energy used for MS/MS experiments. Catechin and epicatechin metabolite quantification were estimated using calibration curves from parent standard compounds.

RESULTS

Oligopin interferes with low molecular weight (LMW) Aβ oligomerization in vitro

In this study, using the photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) technique, we explored the impact of oligopin, a pine bark extract composed of LMW-PAOs, on initial peptide-to-peptide interactions that are necessary for spontaneous oligomerization of Aβ peptides [17]. In the un-cross linked (UnXL) samples, only Aβ1–40 monomers and Aβ1–42 monomers and trimers were revealed on the SDS-PAGE gel.

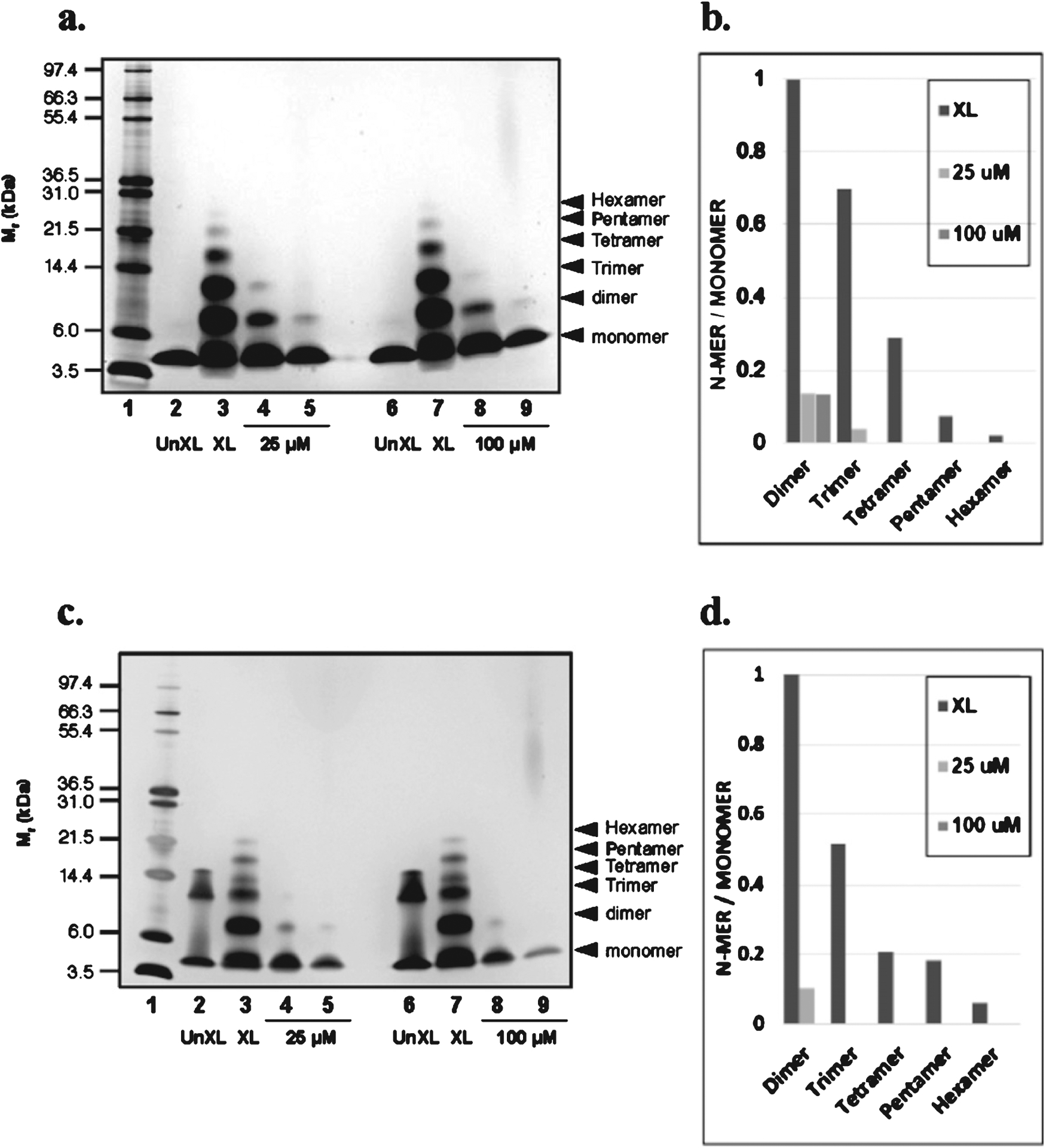

Using cross-linked (XL) samples to stabilize Aβ peptide-to-peptide interactions, we confirmed that Aβ peptides spontaneously aggregate into multimeric conformers: Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 formed a mixture of monomers and oligomers of orders 2–6 (Fig. 1a,c, lanes 3,7).

Fig. 1.

Oligopin attenuates oligomerization of Aβ peptides in vitro. SDS-PAGE of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in the presence or absence of oligopin following PICUP. (a) 25 μM Aβ1–40 and (c) Aβ1–42 were cross-linked in the presence or absence of 25 (1:1) or 100 (1:4) μM oligopin and the bands in subsequent SDS gels were visualized using silver staining. Lane 1: molecular weight; Lanes 2 and 6: UnXL, un-cross-linked Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42; Lanes 3 and 7: XL, cross-linked Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42; Lanes 5 and 9: Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 aggregated in the presence of 25 or 100 μM oligopin; the molecular weight of oligopin is based on the composition of dimer, trimer and tetramer of oligopin. A compound related to oligopin was used as a control to asses attenuation of Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 purposes relative to oligopin (lanes 4 and 8). For each lane that contains crosslinked samples (XL) in a and c, the ratios of the integrated densities of each oligomer to the monomer are shown in panels b and d, respectively. The gels are representative of three independent experiments.

We found that incubation of Aβ1–40 (Fig. 1a) with oligopin at equimolar concentrations (25 μM), completely abolished the formation of aggregated Aβ1–40 hexamer, pentamer, and tetramer species, and reduced the generation of Aβ1–40 dimer (Fig. 1a, lane 5). At 1:4 ratio, oligopin (100 μM) strongly reduced Aβ1–40 dimerization and completely abolished the formation of high order oligomerized Aβ1–40 (Fig. 1a, lane 9). Quantification of Aβ1–40 changes is shown in Fig. 1b.

Similarly, incubation of Aβ1–42 with oligopin at equimolar concentrations (25 μM) completely blocked the formation of aggregated Aβ1–42 hexamer, pentamer, tetramer, and trimer species and strongly reduced the generation of Aβ1–42 dimers (Fig. 1c, lane 5). Aβ1–42 oligomerization (>dimers) was completely blocked at 1:4 ratio of 100 μM oligopin (Fig. 1c, lane 9). As previously described the presence of Aβ1–42 trimer band in UnXL (Fig. 1c, lane 2) is an SDS-induced artifact. Quantification of Aβ1–42 changes are shown in Fig. 1d.

An established compound related to oligopin was used as an internal control for SDS-page PICUP oligomerization studies confirmed the expected PICUP response (shown in Fig. 1a, c, and Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 8).

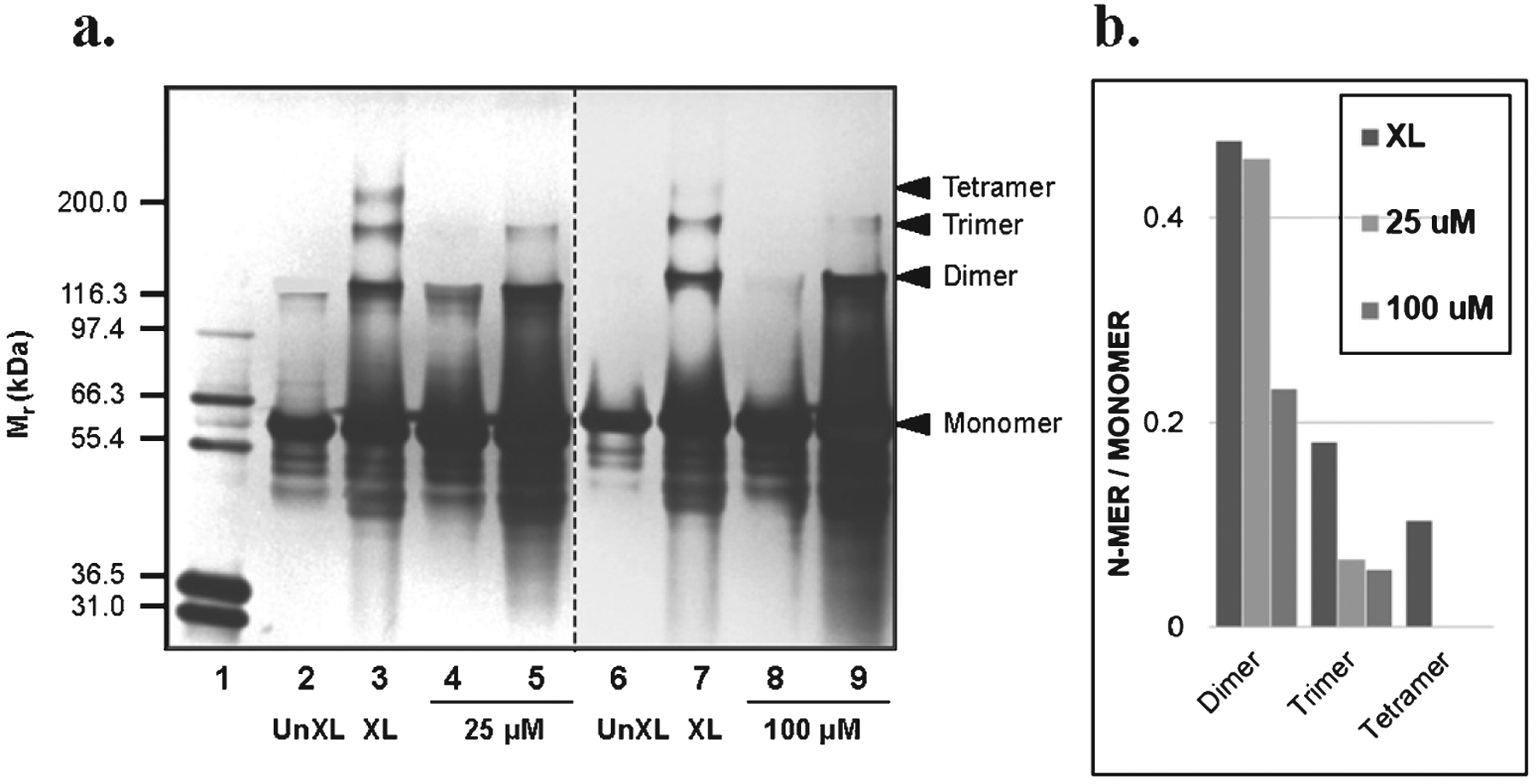

Fig. 2.

Oligopin prevents oligomerization of full-length tau protein in vitro. (a) SDS-PAGE of tau protein in the presence or absence of 25 (1:1) or 100 (1:4) μM oligopin following PICUP. This panel is composed of two independent results. Lanes 1: molecular weight; Lanes 2 and 6: UnXL, un-cross-linked tau protein; Lanes 3 and 7: XL, cross-linked tau protein; Lanes 5 and 9: tau protein aggregated in the presence of 25 or 100 μ M oligopin. A compound related to oligopin was used as a control to assess attenuation of tau oligomerization (lanes 4 and 8). For each lane in a, the ratios of the integrated densities of each oligomer to the monomer in the lane are shown. The gel is representative of three independent experiments.

Oligopin interferes with tau protein misfolding in vitro

Abnormal aggregation of microtubule associated protein tau is the other pathological features of AD neuropathology. Recent evidence strongly suggests abnormal tau as a novel potential therapeutic target for treatment of AD.

We used the similar SDS-page PICUP technique to evaluate the effect of oligopin on abnormal tau aggregation. We found that in un-crossed linked (UnXL) samples, the majority of the full-length tau protein exists as monomers and there is a minor band of dimer (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 6). Following cross-linking (XL), tau protein forms dimer, trimer, and tetramer (Fig. 2, lanes 3,7). In the presence of equal molar (25 μM) of oligopin, there is a complete inhibition tetramer formation and a significant reduction of trimer formation (Fig. 2a, lane 5).

Tau oligomerization was further reduced for the trimerization by oligopin at 1:4 ratio (100 μM) (Fig. 2a, lane 9). This data suggests that oligopin can interfere with initial tau peptides interaction and prevent the formation of tau aggregates in vitro. Quantification of tau oligomerization is shown in Fig. 2b. As shown in Fig. 1a and c, the internal control compound able to attenuate Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 aggregation (lanes 4, 8) also significantly mitigated tau oligomerization as assessed by SDS-page PICUP studies (Fig. 2, lanes 4,8).

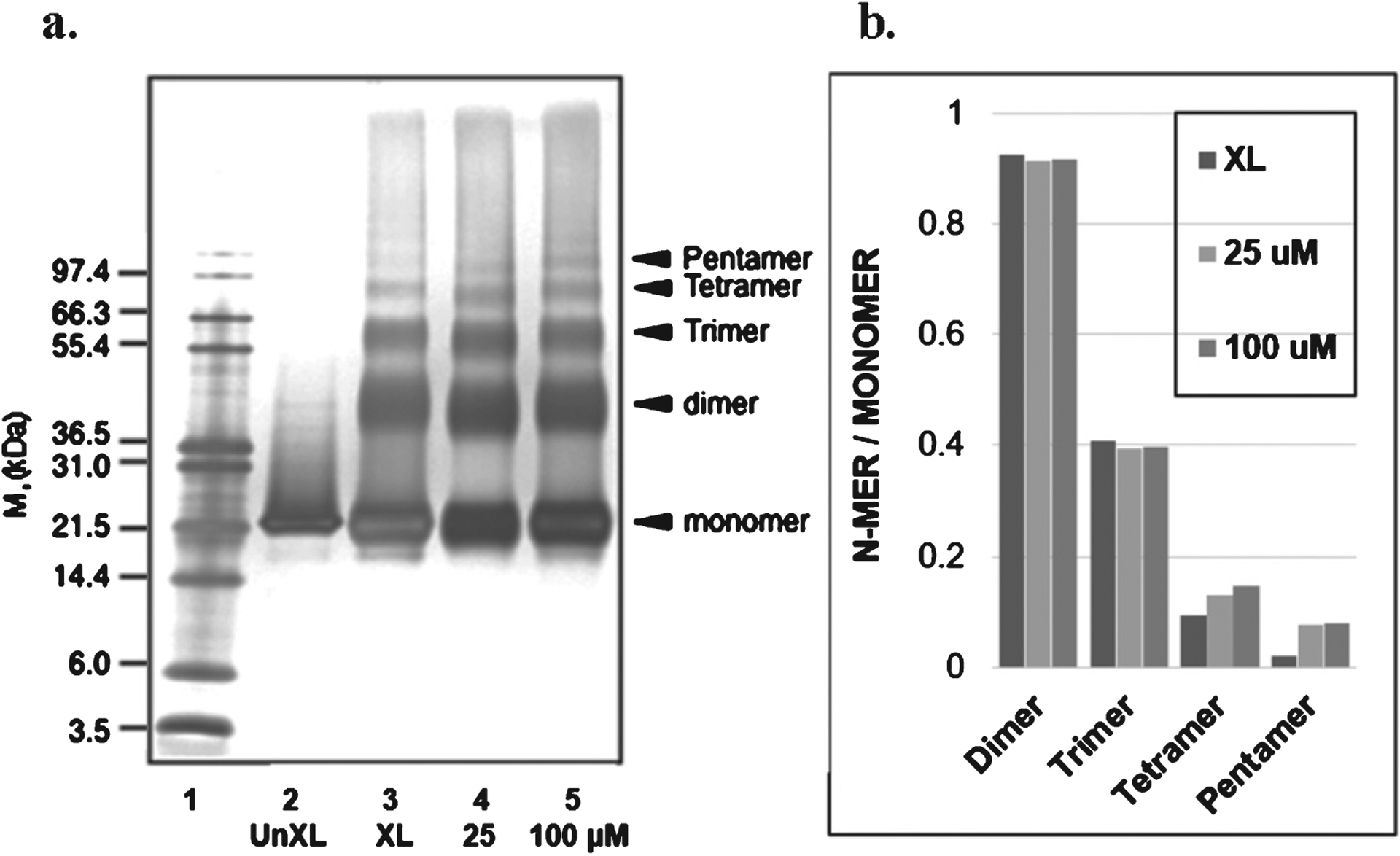

Treatment with 25 or 100 μM oligopin did not affect the cross-linking reaction of GST (Fig. 3a, b). It was previously reported that contrary to western blot staining and developing, photo-oxidation of Ru2+ on PICUP reaction [18], are fixed in this assay based on silver staining: longer staining and developing results into smeared black in silver staining.

Fig. 3.

Oligopin does not influence oligomerization of GST in vitro. (a) SDS-PAGE of GST in the presence or absence of 25 (1:1) or 100 (1:4) μM oligopin, following PICUP. Lane 1: molecular weight; Lane 2: UnXL, un-cross-linked GST; Lane 3: XL, cross-linked GST; Lanes 4 and 5: GST protein aggregated in the presence of 25 or 100 μM oligopin, respectively. For each lane that contains crosslinked samples, the ratios of the integrated densities of each oligomer to the monomer are shown in panel b. The gels are representative of three independent experiments.

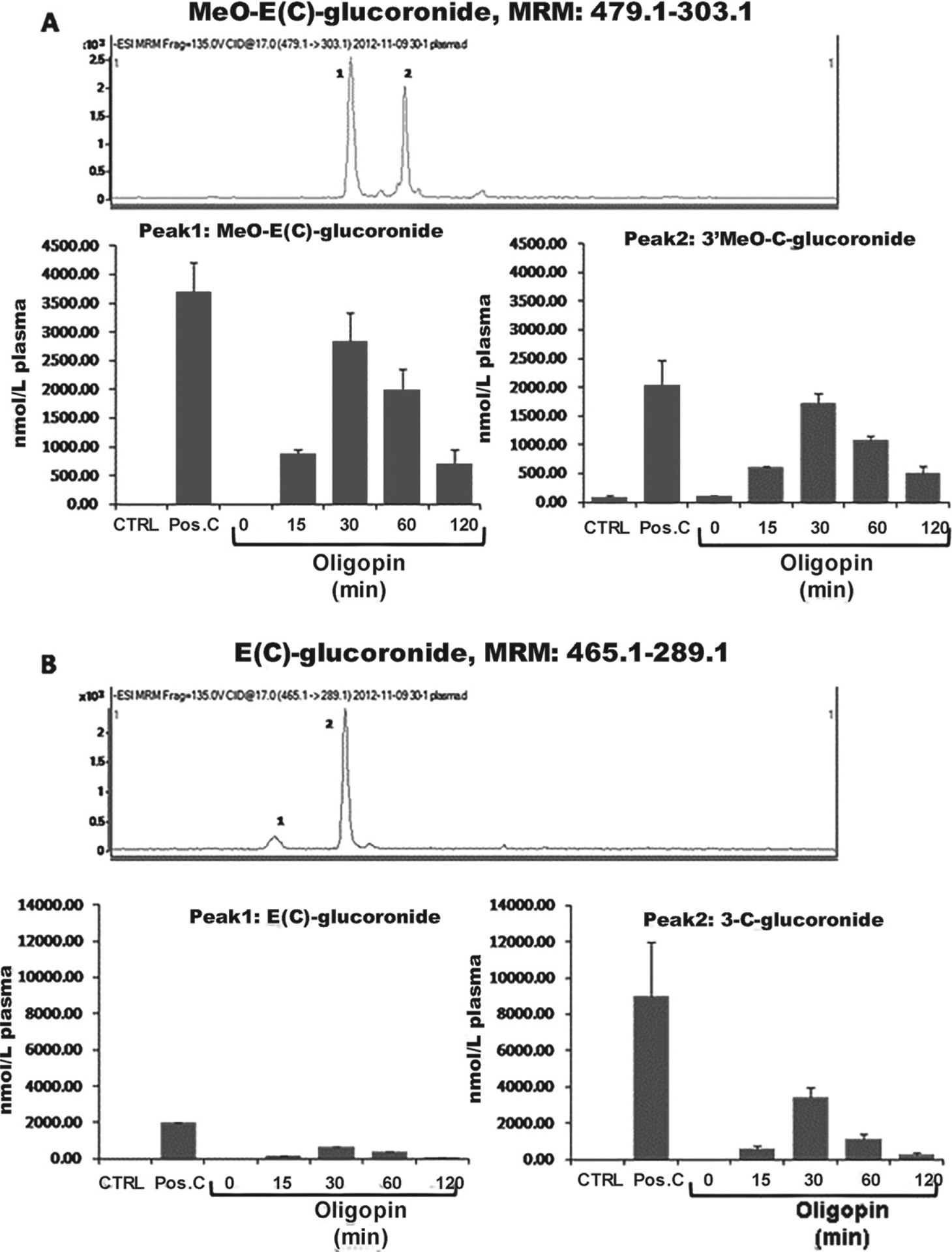

Plasma pharmacokinetic response for EC and C metabolites from oligopin

To gather insight on the in vivo bioavailability and metabolism of oligopin, we measured plasma pharmacokinetics (0–2 h) to explore the impact of longer-term treatment on the bioavailability and metabolism of oligopin following long term treatments. Rats were treated with a daily dose of 200 mg/kg/day delivered through their drinking water for ten days. On the tenth day, plasma pharmacokinetic responses were determined following an oral dose of oligopin. Metabolites of proanthocyanidin monomers, specifically C and EC were detected in mouse plasma following oligopin treatment (Fig. 4). The predominant plasma metabolites of EC and C were tentatively identified by LC-MS-TOF as Me-EC-O-β-Glucuronide (MeO-EC-Gluc), Me-(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (ME-O-Gluc) (Fig. 4A), EC-O-β-glucuronide, and (±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Plasma pharmacokinetics C and EC metabolites following 10 days repeated dosing of oligopin. A, B) Plasma pharmacokinetic profile of methylated and glucuronidated C and EC metabolites following acute on repeated dosing of mice by treatment with 200 mg/kg/day oligopin following acute on repeated dosing. LC-MS/MS separation of major C and EC metabolites detected in extracts of mice plasma collected after 10-day treatment. Multiple reaction monitoring trace is shown for C/EC-O-β-glucuronide (465.1 ± 289.1 m/z) and MeO-C/EC-O-β-glucuronide (479.1 ± 303.1 m/z). Data represent mean ± SD, n = 5 mice per group.

Characterization of these metabolites is consistent with previous reports and the positive control used in the study (Pos. C, Fig. 4A and 4B) that identifies the primary circulating forms of C and EC as methylated and glucuronidated C and EC conjugates that are derived by xenobiotic metabolism in the intestinal tissues and liver of both murine models and humans [19–23].

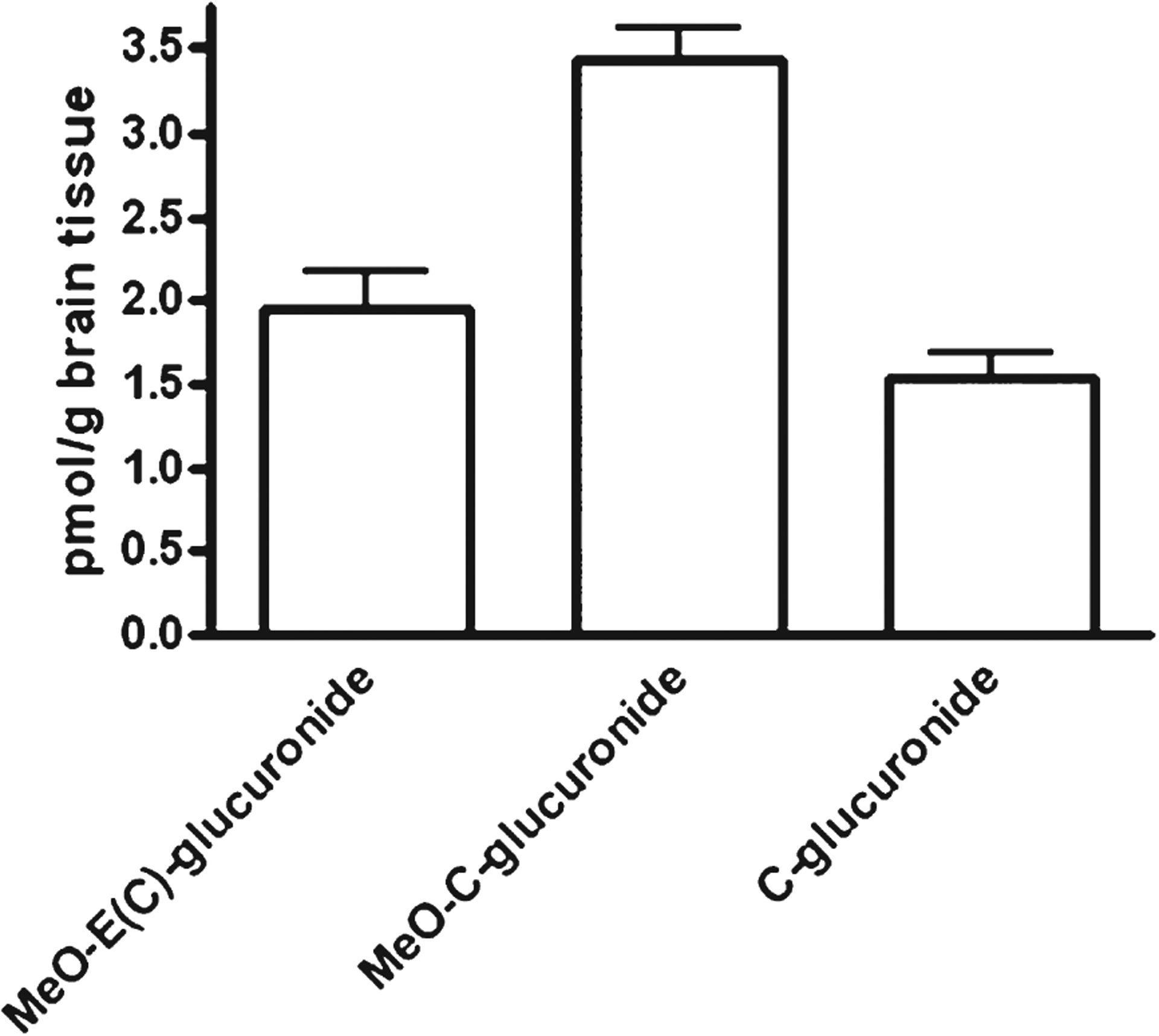

Assessment of metabolite accumulation in mouse brain tissue following 10 days of repeated dosing

A central issue in the development of polyphenol for the central nervous system is whether the compound crosses the blood-brain barrier and whether sufficient concentrations of the drug reach the brain tissues. We next tested for accumulations of C, EC, and their metabolites in brain tissues following chronic treatment with oligopin. We found C and EC phase II metabolites in the brain (O-β-glucuronides and O-Me-β-glucuronides) following repeated treatments with oligopin (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Brain levels of C and EC metabolites following 10 days repeated dosing of oligopin. Brain content of C and EC metabolites following acute or repeated dosing of rats by treatment with 200 mg/kg/day oligopin. The error bars represent standard errors of the means.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrated that oligopin successfully ameliorated AD neuropathologies, suggesting that its application as a novel AD treatment may be effective. Overall, the results of this study suggest a novel mechanism through which EC and C may exert their beneficial effects, and also provide the scientific basis to design future clinical trials with bioactive LMW-PAOs from oligopin to treat mild cognitive impairment and AD.

As previously discussed, our in vitro studies demonstrated that oligopin administration successfully resulted in reductions to the oligomerization of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, and also in the prevention of tau misfolding. We previously showed that PICUP-stabilized oligomers have significant biochemical properties [24, 25]. We observed that neurotoxic activity increased disproportionately (order dependence >1) with oligomer order, that is, namely tetramers ≥ trimers > dimers > monomers [24]. Additionally, we demonstrated that England and Tottori mutant oligomers of Aβ producing oligomer size distributions skewed to higher order, showed higher cytotoxicity than wild type oligomers [25]. These results suggest a novel mechanism through which oligopin and its bioactive constituents EC and C may exert their beneficial effects, as this is the first time that they were shown to be capable of attenuating and preventing misfolding of both Aβ and tau. Future in vivo studies will clarify the association of this mechanism with the attenuation of cognitive deterioration that are associated with AD-type neuropathologies.

In all crosslinking experiments, for Aβ, tau, and GST, the bands in the crosslinked lanes are stronger than in the uncrosslinked lane. A probable explanation is that the crosslinker, which binds to all proteins, is stained very well by silver, which makes all bands to appear stronger.

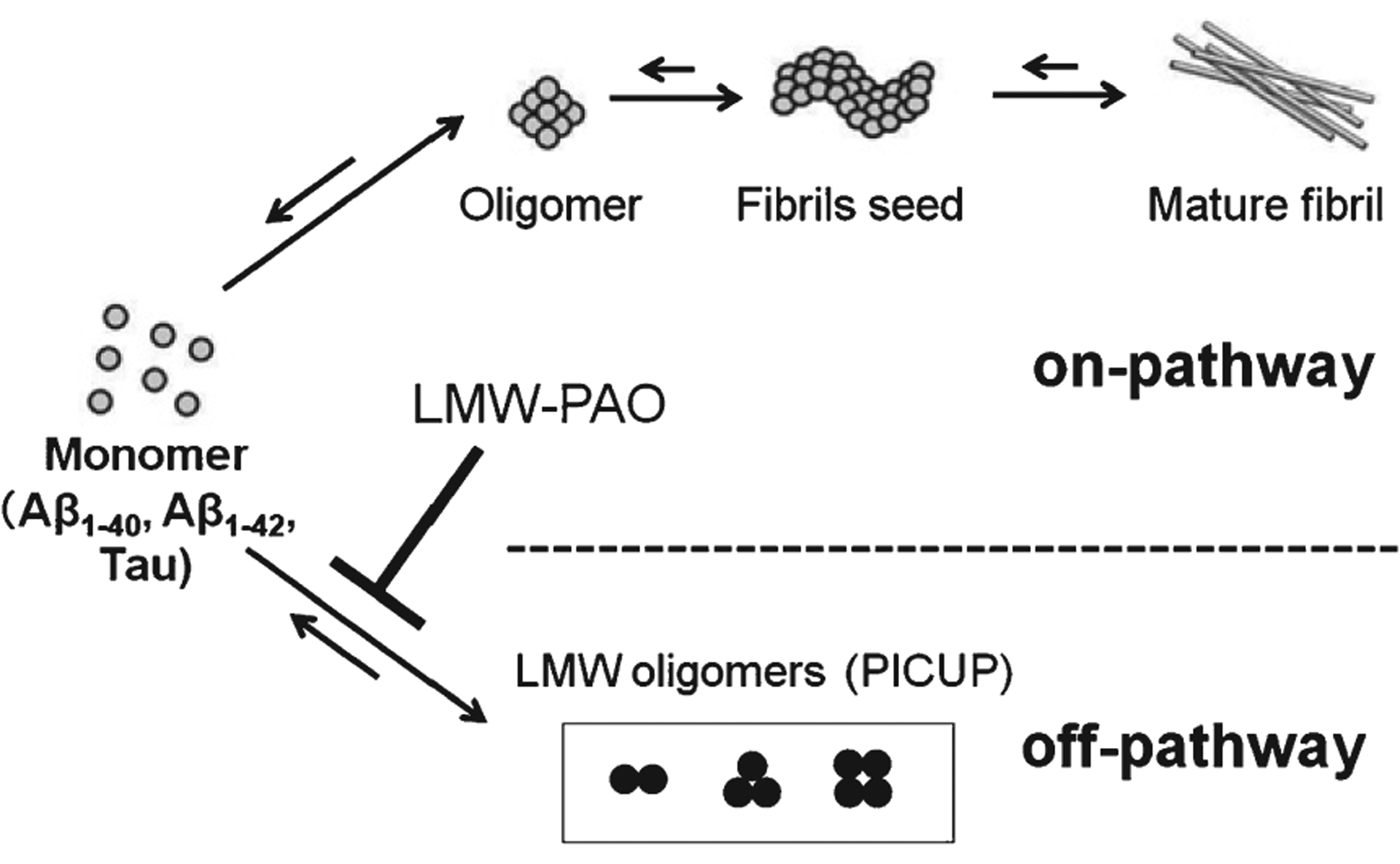

Reduction by LMW-PAO of the amounts of oligomers (Figs. 1 and 2) is not accompanied, as expected, by an increased amount of monomer. A probable explanation is the following: We previously reported that the low n-order oligomers, such as PICUP-derived oligomers of Aβ, begin to exhibit β-sheet content at the dimer stage, whereas they did not exhibit thioflavin fluorescence [24]. Although it was once thought that intermediate aggregates of Aβ are positioned on the on-pathway from monomer to the final aggregates, mature fibrils, some aggregates such as Aβ-derived diffusible ligands, amylospheroids, and PICUP-derived oligomers are on the off-pathway and are more toxic [26–29]. In addition, we recently reported that the superior inhibitory potency of antiplatelet drug cilostazol against Aβ oligomerization, compared to fibrillization, is explained by the fact that the LMW oligomers generated by PICUP are positioned on the off-pathway [30]. Thus, an explanation for the fact that inhibition of LMW-PAO on Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and tau oligomerizations did not accompany distinct monomer increase is that low n-order oligomers generated by PICUP are on the off-pathway (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Inhibitory effects of LMW-PAOs on Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and tau oligomerizations. The monomer of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and tau may aggregate to form intermediate aggregates such as oligomers and finally fibrils. LMW-PAOs mainly prevents off-pathway oligomers of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and tau.

To expedite translatability of these results from in vivo to clinical settings and to assess the metabolism of oligopin in an animal model of AD, a pharmacokinetics analysis was performed. This experiment resulted in the identification of Me-EC-O-β-Glucuronide (MeO-EC-Gluc), Me-(±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (ME-O-Gluc) (Fig. 4A), EC-O-β-glucuronide and (±)-C-O-β-glucuronide (Fig. 4B) in the plasma of mice. These metabolites are primarily methylated and glucuronidated C and EC conjugates. Additionally, in line with previously reported data, we have shown the metabolites derived from oligopin are brain bioavailable compounds. Further studies using transgenic AD models such as 3xTg-AD mice that express human amyloid precursor protein, presenilin-1, and tau transgenes and develop AD-like brain and behavioral pathology are essential in order to confirm the preventing effects of oligopin for Aβ and tau accumulation [31].

Based on previous studies demonstrating that these metabolites improve synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus [16], these results suggest that oligopin may be developed as a potential novel therapeutic agent for the treatment of AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Grant Number P50 AT008661-01 from the NCCIH and the ODS. Dr. Pasinetti holds a Senior VA Career Scientist Award. We acknowledge that the contents of this study do not represent the views of the NCCIH, the ODS, the NIH, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. We thank Dr. Mario Feruzzi for his assistance in the execution of the bioavailability studies.

Footnotes

This article received a correction notice (Erratum) with the reference: 10.3233/JAD-209007, available at https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad209007.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0543r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Cummings JL (2004) Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 351, 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Selkoe DJ (2001) Alzheimer’s disease: Genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 81, 741–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hardy J, Allsop D (1991) Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 12, 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Busciglio J, Gabuzda DH, Matsudaira P, Yankner BA (1993) Generation of β-amyloid in the secretory pathway in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 2092–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Haass C, Schlossmacher MG, Hung AY, Vigopelfrey C, Mellon A, Ostaszewski BL, Lieberburg I, Koo EH, Schenk D, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ (1992) Amyloid β-peptide is produced by cultured-cells during normal metabolism. Nature 359, 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shoji M, Golde TE, Ghiso J, Cheung TT, Estus S, Shaffer LM, Cai XD, Mckay DM, Tintner R, Frangione B, Younkin SG (1992) Production of the Alzheimer amyloid-β protein by normal proteolytic processing. Science 258, 126–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH (2005) Natural oligomers of the amyloid-β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci 8, 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH (2006) A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440, 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jacobsen JS, Wu CC, Redwine JM, Comery TA, Arias R, Bowlby M, Martone R, Morrison JH, Pangalos MN, Reinhart PH, Bloom FE (2006) Early-onset behavioral and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 5161–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Shankar GM, Betts V, Spooner ET, Jiang LY, Anwyl R, Selkoe DJ, Rowan MJ (2005) Amyloid β protein immunotherapy neutralizes Aβ oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo. Nat Med 11, 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhao S, Zhang L, Yang C, Li Z, Rong S (2019) Procyanidins and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 56, 5556–5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee J, Torosyan N, Silverman D (2016) Examining the impact of grape consumption on brain metabolism and cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A double-blinded placebo study. Exp Gerontol 87, 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bitan G, Lomakin A, Teplow DB (2001) Amyloid β-protein oligomerization. Prenucleation interactions revealed by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins. J Biol Chem 276, 35176–35184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ferruzzi MG, Lobo JK, Janle EM, Cooper B, Simon JE, Wu QL, Welch C, Ho L, Weaver C, Pasinetti GM (2009) Bioavailability of gallic acid and catechins from grape seed polyphenol extract is improved by repeated dosing in rats: Implications for treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 18, 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang J, Ferruzzi MG, Ho L, Blount J, Janle EM, Gong B, Pan Y, Gowda GA, Raftery D, Arrieta-Cruz I, Sharma V, Cooper B, Lobo J, Simon JE, Zhang C, Cheng A, Qian X, Ono K, Teplow DB, Pavlides C, Dixon RA, Pasinetti GM (2012) Brain-targeted proanthocyanidin metabolites for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. J Neurosci 32, 5144–5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vollers SS, Teplow DB, Bitan G (2005) Determination of peptide oligomerization state using rapid photochemical crosslinking. Methods Mol Biol 299, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bitan G (2006) Structural study of metastable amyloidogenic protein oligomers by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins. Methods Enzymol 413, 217–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Feng WY (2006) Metabolism of green tea catechins: An overview. Curr Drug Metab 7, 755–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Roura E, Andres-Lacueva C, Jauregui O, Badia E, Estruch R, Izquierdo-Pulido M, Lamuela-Raventos RM (2005) Rapid liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay to quantify plasma (−)-epicatechin metabolites after ingestion of a standard portion of cocoa beverage in humans. J Agric Food Chem 53, 6190–6194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tsang C, Auger C, Mullen W, Bornet A, Rouanet JM, Crozier A, Teissedre PL (2005) The absorption, metabolism and excretion of flavan-3-ols and procyanidins following the ingestion of a grape seed extract by rats. Br J Nutr 94, 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stalmach A, Mullen W, Steiling H, Williamson G, Lean ME, Crozier A (2009) Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of green tea flavan-3-ols in humans with an ileostomy. Mol Nutr Food Res 54, 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Blount JW, Redan BW, Ferruzzi MG, Reuhs BL, Cooper BR, Harwood JS, Shulaev V, Pasinetti G, Dixon RA (2015) Synthesis and quantitative analysis of plasma-targeted metabolites of catechin and epicatechin. J Agr Food Chem 63, 2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB (2009) Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid β-protein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 14745–14750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB (2010) Effects of the English (H6R) and Tottori (D7N) familial Alzheimer disease mutations on amyloid β-protein assembly and toxicity. J Biol Chem 285, 23186–23197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hoshi M, Sato M, Matsumoto S, Noguchi A, Yasutake K, Yoshida N, Sato K (2003) Spherical aggregates of β-amyloid (amylospheroid) show high neurotoxicity and activate tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 6370–6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Roychaudhuri R, Yang M, Hoshi MM, Teplow DB (2009) Amyloid β-protein assembly and Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 284, 4749–4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ono K (2018) Alzheimer’s disease as oligomeropathy. Neurochem Int 119, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shozawa H, Oguchi T, Tsuji M, Yano S, Kiuchi Y, Ono K (2018). Supratherapeutic concentrations of cilostazol inhibits β-amyloid oligomerization in vitro. Neurosci Lett 677, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stover KR, Campbell MA, Van Winssen CM, Brown RE (2015) Early detection of cognitive deficits in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res 289, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]