Summary

Mass transfer of protectant chemicals is a fundamental aspect of cryopreservation and freeze drying protocols. As such, mass transfer modeling is useful for design of preservation methods. Cell membrane transport modeling has been successfully used to guide design of preservation methods for isolated cells. For tissues, though, there are several mass transfer modeling challenges that arise from phenomena associated with cells being embedded in a tissue matrix. Both cells and the tissue matrix form a barrier to the free diffusion of water and protective chemicals. Notably, the extracellular space becomes important to model. The response of cells embedded in the tissue is dependent on the state of the extracellular space which varies both spatially and temporally. Transport in the extracellular space can also lead to changes in tissue size. In this chapter, we describe various mass transfer models that can be used to describe transport phenomena occurring during loading of tissues with protective molecules for cryopreservation applications. Assumptions and simplifications that limit the applicability of each of these models are discussed.

Keywords: mass transfer, diffusion, cryoprotectant, tissue, fixed charges

1. Introduction

Cryopreservation and freeze-drying can be used to store biological specimens, but freezing and drying can be very damaging. To prepare a specimen to survive these processes, it is first necessary to introduce protectants; these chemicals are referred to as either lyoprotectants for freeze-drying or cryoprotectants (CPAs) for cryopreservation. Transport phenomena play an important role in preservation technology. Cryopreservation and freeze-drying both subject biological samples to large temperature gradients leading to transfer of heat, whereas loading cells or tissues with protective agents results in mass transfer. In this chapter, we will focus on delivery of CPAs into cells and tissues for cryopreservation applications, but many of the same principles apply to delivery of lyoprotectants as well.

There are two main cryopreservation approaches, slow cooling and vitrification, and both of these approaches involve the use of CPAs to help guard against the damage associated with ice formation. For slow cooling approaches, formation of ice in the extracellular space concentrates extracellular solutes, providing a driving force for water to flow out of the cell. CPAs protect cells by reducing the extent of this cell dehydration and by mitigating damage caused by the increasingly freeze-concentrated extracellular solution. The goal of vitrification, on the other hand, is to completely avoid ice crystallization and instead achieve a glassy state throughout the sample by adding large amounts of CPA and cooling and warming rapidly. The question of ice formation and the amount that can be tolerated depends on the specimen. For tissues and organs, extracellular ice formation can disrupt the spatial organization of the cells and extracellular matrix and compromise mechanical integrity. As a result, vitrification is typically considered to be the preferred approach for cryopreservation of complex samples such as tissues and organs.

Mass transfer modeling has been used for decades to guide the design of cryopreservation methods for isolated cells. The backbone of these approaches is a mathematical model that describes the flow of water and CPA across the cell membrane, which allows prediction of changes in cell volume and intracellular CPA content. Membrane transport models have classically been used to design multi-step CPA equilibration methods that avoid excessive cell volume changes [1,2]. More recently membrane transport modeling has been used to design CPA equilibration methods that not only avoid excessive cell volume changes, but also minimize protocol duration or CPA toxicity [3–8]. In particular, our group has presented an approach for designing minimally toxic CPA equilibration methods for isolated cells [5–7]. This approach is based on the minimization of a toxicity cost function using predictions of cell membrane transport during CPA addition and removal. The resulting CPA addition methods involve exposure to CPA in hypotonic buffer solution, which causes cell swelling. In contrast, conventional CPA addition methods utilize isotonic buffer and focus on avoiding excessive cell shrinkage. This counterintuitive result highlights the potential for mathematical modeling and optimization to open up promising new avenues of investigation.

Application of such mathematical modeling approaches to three-dimensional tissues will require an appropriate mass transfer model for predicting the evolution of CPA concentration in the tissue with time, as well as potentially damaging changes in cell and tissue volume. The mass transfer process in tissues is more complex than that of isolated cells, and requires consideration of the coupled effects of cell membrane transport and mass transfer in the extracellular space, mechanical properties of the tissue and how they relate to tissue volume changes, and fixed electrical charges in the extracellular space. In the following, we briefly discuss some of these mass transfer phenomena and provide an overview of tissue mass transfer models that have been presented in the literature.

2. Tissue modeling considerations

2.1. Mass Transfer in the Extracellular Space

Preparation of a tissue sample for cryopreservation requires effective delivery of CPAs to all regions of the tissue. This involves transport of the CPA through the tissue from the surface to the center. Compared to isolated cells, the amount of time required to deliver CPA into tissue is often much longer, particularly for large tissues. The time scale for diffusion of CPA into a tissue sample can be estimated as:

| (1) |

where L is the diffusion length and Deff is the effective diffusivity of the CPA in the tissue. The effective diffusivity for various CPAs has been estimated in a variety of tissue types, resulting in values that range from approximately 10−6 cm2/s to 10−5 cm2/s at room temperature [9–17]. Diffusion length can vary depending on the dimensions of the tissue of interest. A pancreatic islet has a radius of about 50 μm, which results in a CPA diffusion time scale of between 3 s and 30 s. Larger tissues require much longer for CPA diffusion. For example, articular cartilage with a half-thickness of about 1 mm would have a diffusion time scale of between 20 min and 3 h.

For comparison, it is useful to consider the typical time scale of the osmotic response of a cell after exposure to a CPA solution. Exposure to CPA causes a shrink-swell response due to initial water efflux followed by influx of both water and CPA. The duration of this shrink-swell response varies depending on the cell type and CPA. For example, human RBCs undergo a shrink-swell response after exposure to glycerol with a time scale on the order of 10 s at room temperature [18]. Oocytes, on the other hand, are much larger and hence respond more slowly after exposure to CPA, exhibiting a shrink-swell response with a time scale of about 10 min [19]. A typical mammalian cell exhibits an intermediate time scale of about 1 min.

A comparison of time scales reveals that transport from the surface to the center of the tissue is often the rate limiting step for delivery of CPA into tissues. Therefore, it is essential to consider interstitial transport for effectively modeling CPA transport in tissues.

2.2. Tissue size changes due to CPA exposure

Mass transfer in tissues has been studied for decades and is typically modeled using Fick’s law of diffusion, assuming that the tissue is comprised of a rigid porous matrix and does not change size. This is reasonable in many cases relevant to physiology and medicine. However, the concentrated solutions used for cryopreservation can create substantial osmotic gradients that cause the size of the tissue to change. For example, exposure of pancreatic islets to 2 M dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) causes the islet to initially shrink to about 70% of its original volume, followed by swelling back to its original volume after about 10 min. This shrink-swell response is shown in Figure 1 [20] and can be attributed to initial loss of water from the tissue, followed by transport of DMSO and water back into the tissue. The size changes observed for pancreatic islets are analogous to those observed for isolated islet cells after exposure to DMSO, but the whole islet shrink-swell process takes slightly longer because of the time required for transport of the DMSO from the islet surface to the center.

Fig. 1.

Volume changes in whole canine pancreatic islets after exposure to 2 molal DMSO at 22°C [20] compared to the corresponding predictions for isolated islet cells [21].

Figure 2 shows that articular cartilage exhibits a similar shrink-swell response after exposure to DMSO [22]. While pancreatic islets have a high cell density, cartilage is primarily comprised of extracellular matrix; cells (mainly chondrocytes) occupy less than 10% of the cartilage volume. The shrink-swell response for articular cartilage is qualitatively similar to the osmotic response of isolated chondrocytes, as illustrated in Figure 2, but it is clear that the size changes in articular cartilage occur over a much longer time scale.

Fig. 2.

Size changes in 2 mm thick articular cartilage after exposure to 6.5 M DMSO at 22°C [22], compared to the corresponding predictions for isolated chondrocytes [23].

Similar size changes after exposure to CPA have also been observed for acellular tissues like decellularized heart valves, as described in a recent paper by Vasquez-Rivera and colleagues [24]. Ovarian tissue has also been observed to undergo a shrink-swell response after exposure to CPA, resulting in an initial mass decrease of over 30% (personal communication, Harriette Oldenhof and Wim Wolkers).

Size changes after exposure to CPA have been observed for various tissue types, ranging from acellular heart valves to tissues with high cell density like pancreatic islets, suggesting that this is a general phenomenon. The size changes in some cases are quite significant and would be expected to affect design of CPA equilibration methods. Thus, there is a need for tissue transport models that can account for size changes. Conventional diffusion modeling using Fick’s law is inadequate in this sense because it is limited to tissues with constant size.

2.3. Fixed charges

The solids found within the extracellular space typically contain polyanionic components that trap positively charged counterions in the fluid phase. These counterions are known as fixed charges, and they impact the flow of all components in the fluid phase. Because the fixed charges remain associated with the solid extracellular matrix, they cannot cross the tissue boundary and a Gibbs-Donnan effect is established. This means that an unequal ion distribution is set up across the tissue boundary where the total concentration of ions in the tissue is higher than that in the external solution at equilibrium. This phenomenon leads to a higher pressure in the tissue than in the surrounding solution. Fixed charges can affect tissue volume changes during exposure to solutions with different salt concentrations, which may have implications for design of tissue cryopreservation procedures. The main contributors to the fixed charge phenomenon are the glycosaminoglycans (GAG) which are anionic in nature. Table 1 highlights the differences in GAG content of several tissue types.

Table 1.

A comparison of the GAG content of several tissue types.

| Tissue Type | GAG Content [g / 100 g tissue] | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Rabbit vitreous body | 0.004 | [25] |

| Human liver | 0.006* | [26,27] |

| Rat Hepatoma | 0.03 | [28] |

| Rabbit skin | 0.086 | [25] |

| Rat Subcutaneous Tissue | 0.14 | [28] |

| Rabbit tendon | 0.21 | [25] |

| Rabbit and Human Sclera | 0.32 | [28] |

| Human Corneal Stroma | 0.46 | [28] |

| Rabbit aorta | 0.49 | [25] |

| Rabbit Corneal Stroma | 0.62 | [28] |

| Human Articular Cartilage | 2.02 | [28] |

| Rabbit articular cartilage | 2.8 | [25] |

| Pig Aorta | 3.91 | [28] |

| Rabbit nasal cartilage | 6.7 | [25] |

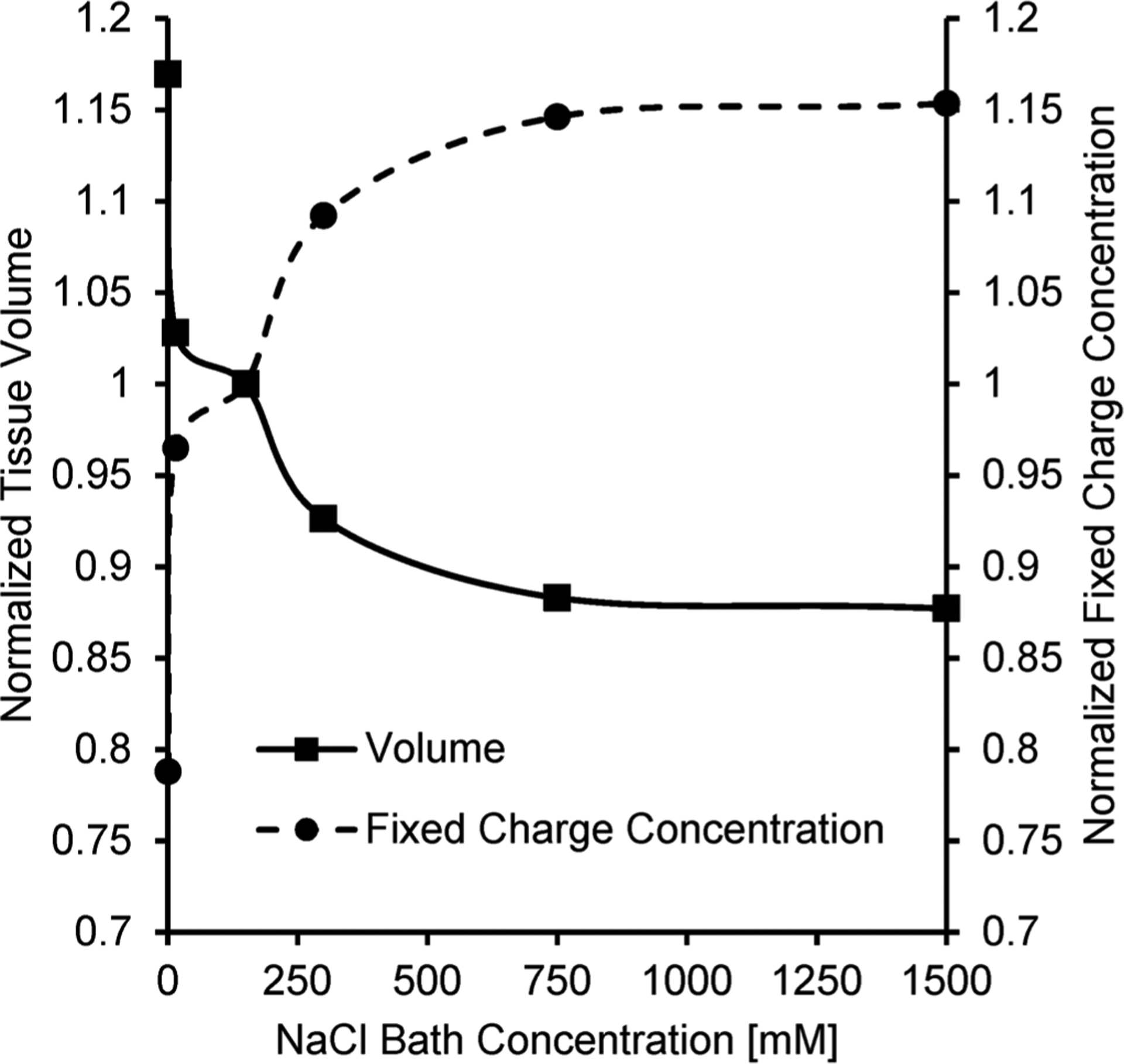

Figure 3 demonstrates how fixed charges influence the equilibrium tissue volume when bovine articular cartilage is exposed to different concentrations of sodium chloride. As the sodium chloride concentration of the bath increases, water leaves the tissue to maintain Donnan equilibrium, which results in a decrease in the volume of the tissue. This shrinkage is expected to result in an increase in the fixed charge concentration within the tissue.

Fig. 3.

Effect of bath sodium chloride concentration on the equilibrium volume of bovine articular cartilage. The volume was calculated using the strain reported by Lai and colleagues [29] using the isotonic NaCl concentration of 150 mM as the reference state. The normalized fixed charge concentration is also shown and was calculated according to Lai and colleagues [29] using an initial interstitial water volume fraction of 80%. A distinct increase in the fixed charge concentration can be seen as the bath becomes more hypertonic and causes the tissue to shrink.

2.4. Coupling between cell membrane transport and mass transfer in the extracellular space

It is common to assume an infinite bath when modeling mass transfer in cell suspensions because the cells occupy such a small fraction of the sample volume. This assumption is equivalent to neglecting the effects of cell membrane transport on the composition of the bath. Most tissues have much higher cell density, so exchange of water and CPA between the cells and the surrounding extracellular fluid has a non-negligible effect on the composition of the extracellular fluid.

This coupling between cell membrane transport and mass transfer in the extracellular fluid manifests itself in three key ways. First, mass transfer in the extracellular space leads to development of a spatial gradient in CPA concentration, which causes the cell response at the center of the tissue to differ from that at the tissue surface. This effect is illustrated in Figure 4 for pancreatic islets. Second, the presence of cells and transport of water and CPA across cell membranes affects the rate of transport through the extracellular space. Typically, cells would be expected to slow mass transfer because the cell membranes provide an additional barrier. The third effect is mediated by changes in cell size. As cells expand in a local tissue region, they concentrate fixed charges, which would in turn draw water to that region. In this way, cell size changes can lead to overall changes in tissue size. Overall, the cell response is inherently dependent on the tissue response and vice versa.

Fig. 4.

Normalized volume change of a rat islet of Langerhans, along with theoretical predictions for islet cells at the surface and center of the islet [30].

3. Tissue Mass Transfer Models

We restrict our discussion to mass transfer models in three-dimensional tissues that are exposed to CPA only at the tissue boundary. There are various considerations that can be used to classify previously reported mathematical modeling approaches. A key consideration is whether the model is capable of predicting changes in the size of the tissue during CPA equilibration. The most common approach for modeling mass transfer in tissues is to use Fick’s law of diffusion, which assumes that the size of the tissue remains constant, but other modeling approaches have been reported that account for tissue size changes. Another distinction we can make is whether the mass transfer driving forces are represented using a dilute (‘ideal’) or non-dilute (‘non-ideal’) approach. In general, as concentration increases there is a departure of one or more constituent activity coefficients from unity, or in other words a departure from solution ideality. Vitrification methods typically involve the use of high CPA concentrations that fall in the non-dilute regime. Another key consideration for modeling mass transfer in tissues is the modes of mass transfer that are considered in the model. There are three main modes of mass transfer: transport across the cell membrane from the intracellular solution to the interstitial space, transport through the interstitial space, and transport from cell to cell. The specific tissue one wants to model dictates the importance of one transport mode over the others. For instance, in a low cell density tissue such as cartilage, transport across the cell membrane and from cell to cell are of less importance than interstitial transport. In a high cell density tissue such as ovarian tissue, the importance of the cell transport terms would increase. In the discussion below, we present previously reported tissue mass transfer models in the context of these modeling considerations.

3.1. Models that assume a constant tissue size

3.1.1. Fick’s Law of Diffusion

Fick’s law of diffusion is commonly used to model mass transfer in tissues. Fick’s first law describes the diffusive flux of a component i (ji) in terms of its concentration gradient:

| (2) |

where Di represents the diffusion coefficient of component i in a designated media, and ci represents the concentration of component i. If we assume only diffusive flux, a mass balance in the absence of a chemical reaction results in Fick’s second law:

| (3) |

Fick’s law as defined in Equation 3 above is fairly straightforward to implement, and the analytical solutions for the common simplifications of homogenous, isotropic media in one-dimension are prevalent and can be found in references such as the classic discussion of diffusion by Crank [31]. However, this modeling approach is limited since it assumes that the size of the tissue remains constant, it neglects the effects of cell membrane transport on interstitial diffusion, and it is based on the assumption that the solution is ideal and dilute.

To make mass transfer predictions using Fick’s law, it is necessary to know the value of the diffusion coefficient Di. Diffusion in porous materials such as tissues is typically described using an effective diffusion coefficient, which takes into account the fact that only a fraction of the tissue volume is available for diffusion, and that the diffusing species typically must follow a tortuous path as it makes its way around solid obstacles in the porous network. The effective diffusion coefficient is typically expressed in terms of the free solution diffusion coefficient as follows:

| (4) |

where Deff is the effective diffusion coefficient, D is the diffusion coefficient in free solution, ε is the void fraction of the tissue, and λ is the tortuosity. Effective diffusion coefficients have been measured for various CPAs in various tissue types, resulting in a ratio Deff/D of about 0.3 [9].

There are several examples in the literature of the use of Fick’s law to design methods for CPA equilibration in tissues. For instance, a series of papers were recently published characterizing CPA diffusion in articular cartilage and describing the use of Fick’s law for design of methods for delivery of a mixture of CPAs into the cartilage [17,32,33]. Diffusion predictions were used to design a multi-step method to reach a desired minimal CPA concentration throughout the cartilage sample in a minimal amount of time [32]. Han and colleagues [11] used Fick’s law to design a method for delivery of CPA into whole ovaries that was predicted to result in a relatively high concentration in the center of the tissue based on the argument that this would reduce osmotic damage during CPA removal. Fick’s law was also used in a recent paper by Benson and colleagues [10] to mathematically optimize methods for CPA delivery into skin, fibroid tissue, and myometrium. Diffusion predictions were used in conjunction with a volume averaged toxicity cost function to design minimally toxic methods for CPA delivery into these tissues. While promising, these novel methods have yet to be experimentally validated.

3.1.2. Interstitial diffusion with coupled cell membrane transport

Several groups have presented mathematical models for CPA transport in tissue that enable prediction of the combined effects of Fickian diffusion and cell membrane transport. This modeling approach accounts for both interstitial diffusion and cell membrane transport, which is an improvement over Fick’s law, but it assumes that the total volume of the tissue is constant, and it is based on the assumption of an ideal and dilute solution.

He and Devireddy [12] and Devireddy [13] describe a Krogh cylinder approach for modeling CPA transport in tissue. Their model builds on previous work by Bhowmick et al [34], which describes adaptation of the classic Krogh cylinder geometry used for organ perfusion modeling to transport in unperfused tissues. The Krogh cylinder is typically comprised of a capillary with a surrounding cylinder of tissue. To adapt this representation to unperfused tissues, the tissue sample was subdivided into a series of rectangular tissue compartments, each comprising a central cylindrical ‘vascular’ space representing all of the extracellular space, and a surrounding volume representing the intracellular space. The governing equation for the extracellular space is Fick’s law of one dimension with a convective term:

| (5) |

where ν represents the local convective velocity. Exchange of water and CPA between the intracellular and extracellular space was modeled using the Kedem-Katchalsky cell membrane transport model.

Cui and colleagues [35] describe a similar modeling approach. The tissue sample was subdivided into control volumes, each of which was further subdivided into an intracellular and extracellular space. Diffusion in the extracellular space between adjacent control volumes was modeled using Fick’s law, but in this case a convective term was not included. The Kedem-Katchalsky model was used to predict exchange of water and CPA between the intracellular and extracellular space.

These modeling approaches account for coupling of interstitial diffusion and cell membrane transport, which is an improvement over Fick’s law, but, again, the total volume of the tissue is assumed constant, and the models are based on the assumption of an ideal and dilute solution.

3.1.3. Maxwell-Stefan diffusion

Xu and Cui [36] describe the use of the Maxwell-Stefan diffusive flux equations for modeling multi-component CPA transport in tissue. This modeling approach describes the movement of chemical species within a non-dilute mixture in terms of the relative velocities of the different components of the mixture. Xu and Cui write the Maxwell-Stefan equations for an n-component system in one-dimension as:

| (6) |

where subscript i or j refers to species i or j, superscript * refers to the average composition of the mixture, γ is the activity coefficient, x is the mole fraction, u is the species velocity, and k is the mass transfer coefficient. Xu and Cui chose UNIFAC and UNIQUAC as their activity coefficient models. The equations defined in Equation 6 can be solved simultaneously to determine the species velocities, which can then be used to determine the flux of each species:

| (7) |

This modeling approach is an improvement over Fick’s law in that it enables prediction of multi-component transport in non-dilute and non-ideal solutions. However, the model does not account for the effects of cell membrane transport, and the tissue size is assumed constant so the model is not capable of predicting tissue size changes during CPA equilibration.

3.2. Models that account for changes in tissue size

3.2.1. Islet model of Benson et al (2014)

Benson et al [37] presented a mathematical model of CPA transport in pancreatic islets that allows prediction of changes in islet size and accounts for interstitial diffusion, cell-to-interstitial transport and cell-to-cell transport. The whole islet of Langerhans was subdivided into concentric spherical shells of cells, and the extracellular space was represented as a series of cylinders that penetrate the spherical geometry normal to a given shell. The Kedem-Katchalsky formalism was used to describe cell-to-interstitial exchange and cell-to-cell exchange. For cell-to-cell exchange, adjacent cells were modeled as two cell membranes in series, effectively halving the membrane permeability. Fick’s law was used to describe transport in the extracellular space, with an extra term representing CPA transport from the cells to the extracellular space:

| (8) |

where fc represents the change in concentration with time of the extracellular space due to exchange with the intracellular space. A key assumption of their model which enables prediction of changes in islet volume is that cells always occupy 80% of the islet volume. This somewhat arbitrary assumption creates a direct link between changes in the volume of islet cells and the resulting change in the size of the whole islet. While this assumption is consistent with experimental data for islets, it does not have a physical basis and thus may not be generally extensible to the full range of conditions encountered during CPA equilibration for islets as well as other tissue types. The model is also limited because it is based on the assumption of an ideal and dilute solution.

3.2.2. Network thermodynamic model

Another example of a model that enables prediction of tissue volume changes based on coupled interstitial transport and cell membrane transport comes from de Frietas and colleagues [30]. In their work, a network thermodynamic model is presented to describe the behavior of a pancreatic islet during CPA equilibration. The pancreatic islet was subdivided into two cellular compartments - one representing cells near the islet surface and the other representing islet cells near the center - as well as interstitial compartments alongside and between the cellular compartments. Flow of water and CPA from the cellular compartments to the interstitial space was modeled based on chemical potential driving forces using the general theory of irreversible thermodynamics. The resulting equations are similar to the Kedem-Katchalsky equations, but the kinetic parameters are specific to the cellular compartments in the model, which are larger than individual islet cells. Flow of water and CPA between adjacent interstitial compartments was assumed to be proportional to their respective chemical potential differences. Interaction between the flow of water and CPA in the interstitial space was neglected. This model enables prediction of islet size changes in terms of the sum of the cell size changes and changes in the volume of the interstitial space. In contrast to the model of Benson et al [37], the model of de Freitas and colleagues enables prediction of changes in the volume of the interstitial space directly based on the calculated flows of water and CPA through the interstitial space. However, the mechanical effects of changes in islet size are not considered in the model, and dilute approximations for the chemical potentials were used.

3.2.3. Non-dilute biomechanical transport model

The model developed by Abazari et al [22] leverages the biomechanical triphasic theory of articular cartilage as proposed by Lai et al [38]. In the triphasic theory, cartilage is approximated as a continuum of water, salt, and the extracellular matrix (solids). Abazari et al added a fourth phase to the theory: CPA. Much like in the Maxwell Stefan diffusion formalism, the thermodynamic driving force for species movement is balanced by the frictional interactions with other components, as both of these representations stem from multicomponent momentum balance. Abazari et al presents the following momentum balance equations:

where the number of components n = 4 for water, salt, solid, and CPA, ρ is the apparent density (mass concentration) of component i, μ is the chemical potential of component i, f is the binary frictional coefficient between component i and j, and ν is the species velocity. These momentum balance equations allow the calculation of the velocity field from which the density field can be updated through time.

Abazari et al made use of non-dilute chemical potential expressions presented by Elliot et al [39] and Elmoazzen et al [40], which builds upon the previous work of Shaozhi and Pegg [41] who also adopted the triphasic theory but used ideal solution approximations for the chemical potentials. The chemical potential expressions for water and CPA include a pressure term that enables coupling of mass transfer predictions to changes in the size of the cartilage tissue and the tissue mechanical properties. Pressure is linked to mechanical strain in the model assuming the cartilage behaves as a linear elastic solid.

In addition, the chemical potential expression for the salt includes a contribution due to fixed charges in the solid phase. The fixed charges affect the equilibrium size of the tissue when exposed to solutions with different salt concentrations. Under hypotonic conditions, the fixed charges in the tissue draw water into the tissue and increase its equilibrium size, while the converse occurs under hypertonic conditions.

Overall, Abazari et al presents a model that accounts for the non-dilute nature of vitrification solutions, while including the tissue-specific phenomena of interstitial transport, mechanical properties, and fixed electrical charges. However, the model neglects the effects of cell membrane transport on interstitial transport. While this is a reasonable assumption for cartilage, which has a cell density of less than 10%, it will be necessary to include cell membrane transport in the model if it is to be extended to other tissue types with higher cell density.

4. Conclusions and future directions

Various approaches have been presented for mathematical modeling of CPA transport in tissues, each with advantages and disadvantages. The most common approach is to use Fick’s law of diffusion to predict the temporal and spatial evolution of CPA concentration within the tissue. Fick’s law is simple and diffusion coefficients are available for various CPAs. However, Fick’s law has several limitations, including the assumption that tissue volume is constant and that the solution is ideal and dilute. Fick’s law also does not account for the effects of cell membrane transport. To address these limitations a variety of more complicated tissue transport models have been presented in the cryobiology literature. These models address important features of CPA transport in tissues, including solution nonideality, coupling between interstitial transport and cell membrane transport, transport-induced tissue size changes, and fixed electrical charges. However, there is not one model that captures all of these features. Thus, there is a need for a general framework for modeling CPA transport in tissue that can be applied to any tissue type.

Novel approaches are currently being pursued that show promise for establishing a more general tissue transport modeling framework. For instance, agent-based modeling involves the construction of a tissue by assembly of a group of agents, each of which represents a cell, and applies rules for how the agents interact with each other and with their environment. A tissue can be built based on known anatomical features and can include multiple cell types with different membrane transport properties. This modeling approach is currently under investigation for rational design of cryopreservation methods [42]. Another current area of investigation is the augmentation of the biomechanical model presented by Abazari and colleagues [22] to account for cell membrane transport and cell size changes [43]. This would expand the utility of the model to include tissue types with a higher cell density than cartilage. These promising new approaches have the potential to open new opportunities for computer-aided design of cryopreservation loading procedures for tissues.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported from funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB027203).

References

- 1.Gao DY, Liu J, Liu C, Mcgann LE, Watson PF, Kleinhans FW, Mazur P, Critser ES, Critser JK (1995) Prevention of osmotic injury to human spermatozoa during addition and removal of glycerol. Hum Reprod 10:1109–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madden PW, Pegg DE (1992) Calculation of Corneal Endothelial-Cell Volume during the Addition and Removal of Cryoprotective Compounds. Cryo-Lett 13:43–50 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlsson JOM, Younis AI, Chan AWS, Gould KG, Eroglu A (2009) Permeability of the Rhesus Monkey Oocyte Membrane to Water and Common Cryoprotectants. Mol Reprod Dev 76:321–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson JD, Chicone CC, Critser JK (2012) Analytical optimal controls for the state constrained addition and removal of cryoprotective agents. Bull Math Biol 74:1516–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson JD, Kearsley AJ, Higgins AZ (2012) Mathematical optimization of procedures for cryoprotectant equilibration using a toxicity cost function. Cryobiology 64:144–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson AF, Benson JD, Higgins AZ (2014) Mathematically optimized cryoprotectant equilibration procedures for cryopreservation of human oocytes. Theor Biol Med Model 11:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson AF, Glasscock C, McClanahan DR, Benson JD, Higgins AZ (2015) Toxicity minimized cryoprotectant addition and removal procedures for adherent endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 10:e0142828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson JO, Szurek EA, Higgins AZ, Lee SR, Eroglu A (2013) Optimization of cryoprotectant loading into murine and human oocytes. Cryobiology 68:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee IN, Li Y, Song YC, Long RC, Sambanis A (2008) Cryoprotectant transport through articular cartilage for long-term storage: experimental and modeling studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16:1379–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benson JD, Higgins AZ, Desai K, Eroglu A (2018) A toxicity cost function approach to optimal CPA equilibration in tissues. Cryobiology 80:144–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han X, Ma L, Benson J, Brown A, Critser JK (2009) Measurement of the apparent diffusivity of ethylene glycol in mouse ovaries through rapid MRI and theoretical investigation of cryoprotectant perfusion procedures. Cryobiology 58:298–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He YM, Devireddy RV (2005) An inverse approach to determine solute and solvent permeability parameters in artificial tissues. Ann Biomed Eng 33:709–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devireddy RV (2005) Predicted permeability parameters of human ovarian tissue cells to various cryoprotectants and water. Mol Reprod Dev:333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubel A, Bidault N, Hammer B (2002) Transport characteristics of glycerol and propylene glycol in an engineered dermal replacement. ASME Conference Proceedings 2002 (36509):121–122 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muldrew K, Sykes B, Schachar N, McGann LE (1996) Permeation kinetics of dimethyl sulfoxide in articular cartilage. Cryo-Lett 17:331–340 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zieger MA, Woods EJ, Lakey JR, Liu J, Critser JK (1999) Osmotic tolerance limits of canine pancreatic islets. Cell Transplant 8:277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jomha NM, Law GK, Abazari A, Rekieh K, Elliott JAW, McGann LE (2009) Permeation of several cryoprotectant agents into porcine articular cartilage. Cryobiology 58:110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papanek TH (1978) The water permeability of the human erythrocyte in the temperature Range +25oC to −10oC, PhD Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen SF, Li M, Li Y, Chen ZJ, Critser JK (2008) Human oocyte vitrification: the permeability of metaphase II oocytes to water and ethylene glycol and the appliance toward vitrification. Fertil Steril 89:1812–1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods E (1999) Water and cryoprotectant permeability characteristics of isolated human and canine pancreatic islets. Cell Transplant 8:549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.: Liu J, Zieger MA, Lakey JR, Woods EJ, Critser JK (1997) The determination of membrane permeability coefficients of canine pancreatic islet cells and their application to islet cryopreservation. Cryobiology 35:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.: Abazari A, Elliott JA, Law GK, McGann LE, Jomha NM (2009) A biomechanical triphasic approach to the transport of nondilute solutions in articular cartilage. Biophys J 97:3054–3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.: Xu X, Cui Z, Urban JPG (2003) Measurement of the chondrocyte membrane permeability to Me2SO, glycerol and 1,2-propanediol. Med Eng Phys 25:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.: Vasquez-Rivera A, Sommer KK, Oldenhof H, Higgins AZ, Brockbank KGM, Hilfiker A, Wolkers WF (2018) Simultaneous monitoring of different vitrification solution components permeating into tissues. Analyst 143:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.: Comper WD, Laurent TC (1978) Physiological function of connective-tissue polysaccharides. Physiol Rev 58:255–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes RM, Cooper AR, Mitchell HH (1953) The composition of the adult human body as determined by chemical analysis. J Biol Chem 203:359–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kojima J, Nakamura N, Kanatani M, Omori K (1975) The glycosaminoglycans in human hepatic cancer. Cancer Res 35:542–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aukland K, Nicolaysen G (1981) Interstitial fluid volume - local regulatory mechanisms. Physiol Rev 61:556–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC (1991) A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular-cartilage. J Biomech Eng-T Asme 113:245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Freitas RC, Diller KR, Lachenbruch CA, Merchant FA (2006) Network thermodynamic model of coupled transport in a multicellular tissue the islet of Langerhans. Biotransport: Heat and Mass Transfer in Living Systems 858:191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crank J (1975) The mathematics of diffusion, second edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shardt N, Al-Abbasi KK, Yu H, Jomha NM, McGann LE, Elliott JAW (2016) Cryoprotectant kinetic analysis of a human articular cartilage vitrification protocol. Cryobiology 73:80–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jomha NM, Elliott JA, Law GK, Maghdoori B, Forbes JF, Abazari A, Adesida AB, Laouar L, Zhou X, McGann LE (2012) Vitrification of intact human articular cartilage. Biomaterials 33:6061–6068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhowmick S, Khamis CA, Bischof JC (1998) Response of a liver tissue slab to a hyperosmotic sucrose boundary condition: Microscale cellular and vascular level effects. Biotransport: Heat and Mass Transfer in Living Systems 858:147–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui ZF, Dykhuizen RC, Nerem RM, Sembanis A (2002) Modeling of cryopreservation of engineered tissues with one-dimensional geometry. Biotechnol Prog 18:354–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu X, Cui ZF (2003) Modeling of the co-transport of cryoprotective agents in a porous medium as a model tissue. Biotechnol Prog 19:972–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson JD, Benson CT, Critser JK (2014) Mathematical model formulation and validation of water and solute transport in whole hamster pancreatic islets. Math Biosci 254:64–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC (1991) A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng 113:245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott JAW, Prickett RC, Elmoazzen HY, Porter KR, McGann LE (2007) A multisolute osmotic virial equation for solutions of interest in biology. J Phys Chem B 111:1775–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elmoazzen HY, Elliott JA, McGann LE (2009) Osmotic transport across cell membranes in nondilute solutions: a new nondilute solute transport equation. Biophys J 96:2559–2571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaozhi Z, Pegg DE (2007) Analysis of the permeation of cryoprotectants in cartilage. Cryobiology 54:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benson J, Abrams J (2018) An agent based model of cell level toxicity accumulation and intercellular mechanics during cpa equilibration in ovarian follicles. Cryobiology 85:153–154 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warner RM, Higgins AZ (2018) Biomechanical model of cryoprotectant transport in tissues with high cell density. Cryobiology 85:154–154 [Google Scholar]