Abstract

Objectives

Guidelines for treatment of mRCC recommend nivolumab monotherapy (NIVO) for treated patients, and nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy (NIVO+IPI) for untreated IMDC intermediate and poor-risk mRCC patients. Although molecular-targeted therapies (TTs) such as VEGFR-TKIs and mTORi are recommended as subsequent therapy after NIVO or NIVO+IPI, their efficacy and safety remain unclear.

Methods

Outcome of Japanese patients with mRCC who received TT after NIVO (CheckMate 025) or NIVO+IPI (CheckMate 214) were retrospectively analyzed. Primary endpoints were investigator-assessed ORR of the first TT after either NIVO or NIVO+IPI. Secondary endpoints included TFS, PFS, OS and safety of TTs.

Results

Twenty six patients in CheckMate 025 and 19 patients in CheckMate 214 from 20 centers in Japan were analyzed. As the first subsequent TT after NIVO or NIVO+IPI, axitinib was the most frequently treated regimen for both CheckMate 025 (54%) and CheckMate 214 (47%) patients. The ORRs of TT after NIVO and NIVO+IPI were 27 and 32% (all risks), and median PFSs were 8.9 and 16.3 months, respectively. During the treatment of first TT after either NIVO or NIVO+IPI, 98% of patients experienced treatment-related adverse events, including grade 3–4 events in 51% of patients, and no treatment-related deaths occurred.

Conclusions

TTs have favorable antitumor activity in patients with mRCC after ICI, possibly via changing the mechanism of action. Safety signals of TTs after ICI were similar to previous reports. These results indicate that sequential TTs after ICI may contribute for long survival benefit.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, molecular targeted therapy, nivolumab, ipilimumab

Outcome of targeted molecular therapies after discontinuation of nivolumab or nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with mRCC was retrospectively analyzed. Efficacy was favorable, and safety was similar to previous reports.

Introduction

Molecular-targeted therapies (TTs) have been the standard therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) after cytokine era (1). Four vascular endothelial growth factors tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors (VEGFR-TKIs), sorafenib, sunitinib, axitinib and pazopanib, and two mammalian targets of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORis), temsirolimus and everolimus, are approved as TTs for mRCC in Japan. Because all of the TTs have antiangiogenic effects, via inhibition of HIF-1α generation driven by hypoxia, mechanism of action (MOA) for their antitumor activity lacks diversity. Benefit of sequential therapy of TTs was limited, especially among first-line VEGFR-TKI-resistant mRCC patients (2–6).

Immuno-checkpoint molecule inhibitors including anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibody and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibody, novel MOA for treatment of mRCC, emerged as promising treatment from the results of phase 1 studies (7–9). Immuno-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) regimens, such as nivolumab monotherapy (NIVO) and nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy (NIVO+IPI), significantly improved overall survival of patients with mRCC in the randomized phase III studies, CheckMate 025 (10–12) and CheckMate 214 (13–15).

Results of these phase III studies prompted a drastic paradigm shift in mRCC treatment, namely the identification of new target molecules independent of anti-angiogenesis, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, for mRCC treatment. Although ICI regimens became standard therapies for mRCC among recent guidelines (16–18), antiangiogenetic TTs such as VEGFR-TKIs and mTORis, still play important role in mRCC treatment. Since 35% of CheckMate 025 patients and 20% of IMDC intermediate/poor risk CheckMate 214 patients were evaluated as PD for their BOR, and majority of patients discontinued ICI because of disease progression, efficacy and safety data of sequential therapy after ICI regimens are essential for determining the treatment strategies of mRCC.

TTs are recommended as subsequent therapy after discontinuation of NIVO and NIVO+IPI (16, 17). Reported efficacy and safety data of TTs after ICIs are generally favorable without new safety signals (19–29), but most of the reports were analyzed among several ICI regimens except for few reports (22, 28,29), the impact of TTs after NIVO and NIVO+IPI remains unclear. Aim of this study is to clarify the benefit of TTs after discontinuation of NIVO or NIVO+IPI independently, by evaluating the efficacy and safety of first TT, after discontinuation of NIVO or NIVO+IPI, in patients with mRCC.

Patients and methods

“AFTER I-O Study” is a multicenter, retrospective, observational study conducted in Japan. Patients participated in CheckMate 025 or CheckMate 214, treated with TT as subsequent therapy before 31 March 2019, after discontinuation of NIVO or NIVO+IPI were analyzed. Primary endpoints were overall response rates (ORRs) of the first TT after discontinuation of NIVO or NIVO+IPI. Secondary endpoints included treatment-free survival (TFS), efficacy of TT after ICI discontinuation, such as progression-free survival (PFS), time to treatment failure (TTF), overall survival (OS) and safety. TFS was defined as time from last dose of NIVO or NIVO+IPI to first dose of TT after ICI discontinuation, and PFS was defined as time from first TT dose after ICI discontinuation to PD or death.

AFTER I-O study was approved by the independent ethics committees of each institution, and conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. This study is registered with the University hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN), number UMIN000036063. This retrospective study used medical records for analysis; therefore, informed consent from patients was not required.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise specified, continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively, and categorical variables were analyzed using chi-squared test. OS, PFS, TTF and TFS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each treatment arm were determined using hierarchical Bayesian survival analysis and Cox’s proportional-hazards model. Stepwise multivariate analysis was used to assess the significance of each BOR variable. SAS (SAS Institute Japan Ltd., version 9.4) was used for all analyses.

Results

Patients

The present study retrospectively analyzed 45 patients from 20 Japanese centers: 28 of 37 (76%) Japanese patients were treated with TT after NIVO in CheckMate 025 (11–12), and 19 of 38 (50%) Japanese patients (all risks) treated were treated with TT after NIVO+IPI in CheckMate 214 (15), before 31 March 2019. Since two patients from CheckMate 025 refused to participate in this study, data from 26 patients of CheckMate 025 and 19 patients of CheckMate214, a total 45 patients, were analyzed in the present study. Patient characteristics at the first dose of TT treatment after ICI discontinuation are summarized in Table 1 (Patient characteristics for patients with intermediate/poor risks in CheckMate 214 are summarized in Supplementary Table S1). Patients received TTs as third- to fifth-line therapy in CheckMate 025, and second-line therapy in CheckMate 214 after ICI discontinuation. Although patients in CheckMate 025 had received prior therapy before NIVO, compared with patients in CheckMate 214, higher proportion of patients had ECOG PS 0 at the first dose of TT after ICI discontinuation. Overall, 23% of patients in CheckMate 025 and 32% of patients in CheckMate 214 patients discontinued ICI due to adverse events, and most patients discontinued ICI because of disease progression. Major metastatic sites were lung and lymph node. Median follow-up periods from treatment of first TT after ICI discontinuation to date of analysis or death were 22.1 and 20.3 months, for patients of CheckMate 025 and CheckMate 214, respectively. At the date of analysis, 11 patients of CheckMate 025 (42%) and 13 patients of CheckMate 214 (68%) were alive. As shown in Table 2, axitinib was the most commonly treated TT after both NIVO (54%) and NIVO+IPI (47%) discontinuation (TT regimens after ICI discontinuation among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks are in Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at first TT treatment after ICI discontinuation

| CheckMate 025 | CheckMate 214 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All risks | |||||

| N = 26 | N = 19 | ||||

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 17 | (65) | 17 | (90) |

| Female | 9 | (35) | 2 | (11) | |

| Age, years | Median (range) | 69.0 | (40–83) | 70.0 | (45–82) |

| Regimens before ICI, n (%) | 1 | 14 | (54) | ||

| 2 | 8 | (31) | |||

| 3 | 4 | (15) | |||

| TTF of ICI, months | Median (range) | 9.4 | (0.5–59.4) | 6.2 | (0.0–27.6) |

| Reason for ICI discontinuation, n (%) | Progression | 20 | (77) | 13 | (68) |

| Adverse events | 6 | (23) | 6 | (32) | |

| Surgery after ICI discontinuation, n (%) | Yes | 1 | (4) | 3 | (16) |

| No | 25 | (96) | 16 | (84) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | 0 | 20 | (77) | 10 | (53) |

| 1 | 4 | (15) | 5 | (26) | |

| ≥2 | 1 | (4) | 3 | (16) | |

| Unknown | 1 | (4) | 1 | (5) | |

| MSKCC risk classification at first subsequent TT after ICI, n (%) | Favorable | 6 | (23) | ||

| Intermediate | 14 | (54) | |||

| Poor | 4 | (15) | |||

| Unknown | 2 | (8) | |||

| IMDC risk classification at first subsequent TT after ICI, n (%) | Favorable | 1 | (5) | ||

| Intermediate | 14 | (74) | |||

| Poor | 3 | (16) | |||

| Unknown | 1 | (5) | |||

| Primary tumor | Yes | 5 | (19) | 3 | (16) |

| Metastatic site | Lung | 19 | (73) | 12 | (63) |

| Bone | 6 | (23) | 7 | (37) | |

| Brain | 2 | (8) | 1 | (5) | |

| Liver | 7 | (27) | 3 | (16) | |

| Lymph node | 9 | (35) | 8 | (42) | |

TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TTF, time to treatment failure; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; IMDC, International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium

Table 2.

First TT after ICI discontinuation

| CheckMate 025 | CheckMate 214 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All risks | |||||

| N = 26 | N = 19 | ||||

| TT, n (%) | Sunitinib | 8 | (31) | 6 | (32) |

| Axitinib | 14 | (54) | 9 | (47) | |

| Pazopanib | 1 | (4) | 3 | (16) | |

| Everolimus | 3 | (12) | 1 | (5) | |

TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Efficacy

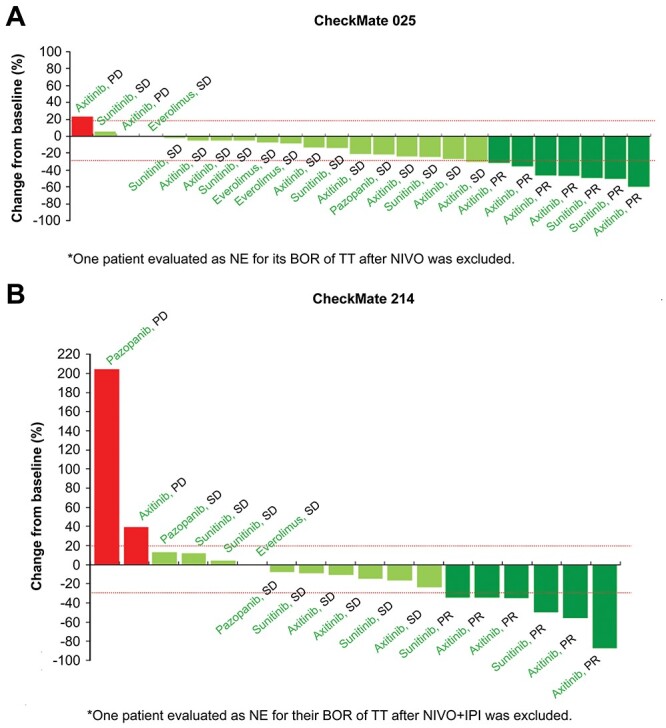

Primary endpoints, ORRs of the first TT were 27% after NIVO, and 32% after NIVO+IPI (all risks). Disease control rates (DCRs) were 89 and 84% (all risks), for TT after NIVO and NIVO+IPI, respectively (Table 3, ORR, BOR and DCR of TT among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks are in Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, 84% (21/25) of patients who received TT after NIVO and 67% (12/18) of patients who received TT after NVO + IPI experienced tumor shrinkage (Fig. 1). Median PFS of TT after NIVO was 8.9 (95% CI: 6.9–21.0) months (Fig. 2A), and after NIVO+IPI was 16.3 [95% CI: 11.0-not reached (NR), all risks] months (Fig. 2B, PFS among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks is in Supplementary Fig. S1). Median OS of TT after NIVO was 29.5 (95% CI: 14.5-NR) months (Fig. 3A). Median OS of TT after NIVO+IPI was NR (95% CI: 18.1-NR), and estimated survival rates at 12, 24 and 36 months were 90, 68 and 54%, respectively (Fig. 3B, OS among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks is in Supplementary Fig. S2). At the time of analysis, two patients (8%) were still on first TT after NIVO, whereas most patients (73%) were treated with subsequent therapy after NIVO-TT failure (Fig. 4A) and three patients (16%, all risks) were still on first TT after NIVO+IPI, whereas most patients (75%, all risks) were treated with subsequent therapy after NIVO+IPI-TT failure (Fig. 4B, TTF of ICI, TFS, TTF of TT therapy after ICI discontinuation among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks are in Supplementary Fig. S3). Major regimens for second subsequent therapy after ICI discontinuation were VEGFR-TKIs (Table 4, second treatment after ICI discontinuation among patients in CheckMate 214 with intermediate/poor risks is in Supplementary Table S4). Median TFS was 0.95 month between NIVO and TT, and 2.46 months (all risks) between NIVO+IPI and TT (Fig. 4A and Fig. 4AB).

Table 3.

Response rates of TT after ICI discontinuation

| CheckMate 025 | CheckMate 214 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All risks | |||||||

| N = 26 | N = 19 | N = 45 | |||||

| ORR, n (%) | 7 | (27) | 6 | (32) | 13 | (29) | |

| DCR, n (%) | 23 | (88) | 16 | (84) | 39 | (87) | |

| BOR, n (%) | CR | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| PR | 7 | (27) | 6 | (32) | 13 | (29) | |

| SD | 16 | (62) | 10 | (53) | 26 | (58) | |

| PD | 2 | (8) | 2 | (11) | 4 | (9) | |

| NE | 1 | (4) | 1 | (5) | 2 | (4) | |

TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; ORR, overall response rate; DCR, disease control rate; BOR, best overall response; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NE, not evaluable

Figure 1.

Best tumor burden shrinkage of TT after ICI discontinuation. 1A. CheckMate 025; 1B. CheckMate 214 (all risks) TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease; PR, partial response; NE, not evaluable; BOR, best overall response; NIVO, nivolumab; IPI, ipilimumab.

Figure 2.

PFS of TT after ICI discontinuation. 2A. CheckMate 025; 2B. CheckMate 214 PFS, progression-free survival; TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; NE, not evaluable; NIVO, nivolumab; IPI, ipilimumab.

Figure 3.

OS of TT after ICI discontinuation. 3A. CheckMate 025; 3B. CheckMate 214 OS, overall survival; TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached.

Figure 4.

TTF of ICI, TFS, and TTF of TT therapy after ICI discontinuation. 4A: CheckMate 025; 4B. CheckMate 214 TTF, time to treatment failure; TFS, treatment-free survival; TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NIVO, nivolumab; IPI, ipilimumab; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Second treatment after ICI discontinuation

| CheckMate 025 | CheckMate 214 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All risks | |||||

| N = 19 | N = 12 | ||||

| Second treatment after ICI discontinuation, n (%) | Sunitinib | 1 | (5.3) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Axitinib | 3 | (15.8) | 5 | (41.7) | |

| Pazopanib | 6 | (31.6) | 5 | (41.7) | |

| Everolimus | 3 | (15.8) | 1 | (8.3) | |

| Temsirolimus | 4 | (21.1) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Nivolumab | 2 | (10.5) | 1 | (8.3) | |

ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Safety

Almost all patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) while receiving TT after ICI, and 51% of patients experienced grade 3–4 events (Table 5). Major all-grade TRAEs were hypertension (n = 17, 38%), fatigue (n = 16, 36%), hoarseness (n = 15, 33%), and anorexia (n = 14, 31%). Major grade 3–4 TRAEs included hypertension, decreased neutrophil counts, elevated AST and elevated ALT (four patients each, 9%). Grade 4 TRAEs were decreased platelet count, vomiting and pneumonitis (one patient each, 2%). Among the grade 3–4 TRAEs, most were grade 3 and no treatment-related deaths.

Table 5.

Treatment-related adverse events of TT after ICI discontinuation occurring in >15% of patients

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |||

| Event | 44 | (98) | 23 | (51) |

| Hypertension | 17 | (38) | 4 | (9) |

| Fatigue | 16 | (36) | 1 | (2) |

| Hoarseness | 15 | (33) | 0 | (0) |

| Anorexia | 14 | (31) | 3 | (7) |

| Platelet count reduction | 13 | (29) | 4 | (9) |

| Proteinuria | 13 | (29) | 2 | (4) |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 | (29) | 1 | (2) |

| Palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 12 | (27) | 1 | (2) |

| Diarrhea | 12 | (27) | 0 | (0) |

| Anemia | 11 | (24) | 1 | (2) |

| Creatinine elevation | 8 | (18) | 0 | (0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase elevation | 7 | (16) | 4 | (9) |

| White blood cell count reduction | 7 | (16) | 2 | (4) |

| Lymphocyte count reduction | 7 | (16) | 2 | (4) |

TT, molecular targeted therapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Discussion

In the present study, we firstly demonstrate efficacy and safety of TT after NIVO+IPI in Japanese cohorts.

Auvray et al. reported the efficacy of VEGFR-TKIs after NIVO+IPI failure in 33 patients. ORR and DCR were 36 and 76%, respectively; median PFS was 8 months, and 12-months OS rate was 54%. 42% of patients developed grade 3–4 adverse events (22). Our results of 19 patients of CheckMate 214 ORR of TT after NIVO+IPI was 32% (all risks), and median PFS was 16.3 months (all risks). Although the number of the patients is small, the present data revealed comparable ORR and longer PFS, indicating similar efficacy for Japanese patients to those reported above. In dose titration study, similar PFS, 14.6 months, was achieved with axitinib in first-line setting (30), so that it is not of surprise for longer, 16.3 months median PFS, because these 19 patients were VEGFR-TKI-naïve.

Another promising data obtained in the present study is favorable results in TT after discontinuation of NIVO in CheckMate 025. TT was applied as third to fifth line of the treatments including at least one prior TT. In the similar setting, Numakura et al. reported PR for 3 patients, and SD for 6 patients out of 13 patients who failed NIVO (28). And Ishihara et al. reported efficacy of third-line axitinib after first-line VEGFR-TKI and second-line NIVO. ORR and DCR were 29 and 94%, respectively; median PFS was 12.8 months, and 1-year OS rate was 72% (29). No safety data are available for TT after NIVO discontinuation. It is difficult to compare these series of patients, but the result of the present study was comparable with the former study in terms of response. Median PFS of TT after discontinuation of NIVO, 8.9 months, was similar to that of second-line axitinib, 6.7 months, in AXIS trial (31), and longer than third-line dovitinib, 3.7 month, in GOLD trial (32), third-line everolimus, 4.0 month, in RECORD-1 trial (33). These data indicated that the prior treatment with ICI may not deteriorate the sensitivity to sequential TTs in patients with mRCC, resulting in moderate-to-favorable ORRs and excellent DCRs. As for safety of TTs after NIVO or NIVO+IPI, ratio of patients with all grade and grade 3–4 TRAEs was comparable to the recent reports (34–37), without any new safety signal.

Costantini et al. (38), Harada et al. (39) and Kato et al. (40) have described the benefit of subsequent chemotherapy after ICI discontinuation for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, MOA to explain the benefit of chemotherapy after ICI discontinuation is not clear. Osa et al. detected NIVO binding to T cells in blood at >20 weeks after treatment discontinuation in patients with NSCLC (41) so that residual NIVO binding to T cells after treatment discontinuation might improve the efficacy of the sequential chemotherapy. Presumably, such MOA might anticipate anti-angiogenetic TTs in patients with mRCC.

Another possibility is that cessation period of exposure to VEGFR-TKI might restore their sensitivity. Indeed, numerically lower efficacy for consecutive VEGFR-TKIs after first-line ICI + VEGFR-TKI (ORR: 10%; median PFS: 5.6 months) (20) or VEGFR-TKI (ORR: 16.6−32%; median PFS: 7.14–9.3 months) (42–44) were reported. Previous reports suggested that sensitivity of EGFR-TKI might improve after EGFR-TKI-free interval for EGFR-TKI-resistant NSCLC patients (45). Treatment of NIVO may restore sensitivity of sequential TT by delivering VEGFR-TKI-free interval for RCC patients.

Both CheckMate 025 (10) and CheckMate 214 (13), pivotal phase III studies of NIVO and NIVO+IPI, reported a significant OS benefit with moderate improvement in PFS. The favorable efficacy of sequential TTs might possibly have contributed to the long survival benefit in these phase III trials. Besides, quality of life in survival is also important, and to minimize deterioration of ordinary life including adverse events is crucial. It is more favorable to achieve stable of disease without any treatment following induction therapy. There appeared stable of disease or even shrinkage of metastases after discontinuation of ICI. Such TFS after ICI was reported by McDermott et al. (46), median TFS for ITT patients who discontinued NIVO+IPI in CheckMate 214 was 3.0 months. Median TFS after NIVO+IPI in this study, in which patients were the subgroup of CheckMate 214, was similar (2.46 months, Fig. 4B) to overall population (46), though between the two analysis, patient population slightly differs. In addition to obtain better QOL, treatment-free period may also contribute to restoration of sensitivity to VEGFR-TKI as mentioned above.

The AFTER I-O study had some limitations, which must be addressed. First, this was a retrospective study with a small sample size. In addition, the patients analyzed in this study were those who met the inclusion criteria of phase III trials; therefore, the results may not directly reflect the treatment in real-world settings. Lastly, the patients in CheckMate 025 or CheckMate 214 who continued to receive ICI or discontinued ICI without subsequent TT could not be analyzed in this study; this may have resulted in selection bias.

In conclusion, TTs as subsequent therapy after NIVO or NIVO+IPI discontinuation exhibits favorable antitumor activity for mRCC, possibly due to changes in the MOA between treatment lines. Safety signals of first subsequent TT after ICI regimens were similar to the previous reports, and no treatment-related deaths occurred. These results indicate that sequential TTs after ICI may contribute for long survival benefit in patients with mRCC, the nature of retrospective study, and the sample size was small. Prospective study is warranted to fully elucidate the favorable results, since the present study is retrospective study with small sample size.

Prior presentation

Presented at Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, 13–15 February, 2020, at San Francisco, CA, USA.

Author contributions

Tomita, Kabu and Tajima have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Tomita, Kabu, and Tajima. Provision of study materials or patients: Tomita, Kimura, Fukasawa, Numakura, Sugiyama, Yamana, Naito and Oya. Collection and assembly of data: Tomita, Kabu and Tajima.

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Tomita, Kabu and Tajima.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and families who made this study possible. We also acknowledge the investigators of AFTER I-O study, Takahiro Kojima, Keiichi Kondo, Ryuichi Mizuno, Keisuke Monji, Masayoshi Nagata, Toru Nakagawa, Masahiro Nozawa, Takahiro Osawa, Takayuki Sugiyama, Takatoshi Somoto, Masayuki Takahashi, Atsushi Takamoto, Daichi Tamura, Kazunari Tanabe and Toshiaki Tanaka.

Contributor Information

Yoshihiko Tomita, Department of Urology, Molecular Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan.

Go Kimura, Department of Urology, Nippon Medical School Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

Satoshi Fukasawa, Prostate Center and Division of Urology, Chiba, Japan.

Kazuyuki Numakura, Department of Urology, Akita University School of Medicine, Akita, Japan.

Yutaka Sugiyama, Department of Urology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kumamoto, Japan.

Kazutoshi Yamana, Department of Urology, Molecular Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan.

Sei Naito, Department of Urology, Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine, Yamagata, Japan.

Koki Kabu, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Yohei Tajima, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka-shi, Japan.

Mototsugu Oya, Department of Urology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Funding

This work was supported by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Because we received industrial funding, no grant number was required. We have not received any funding/grant. Authors received no financial support or compensation for publication of this manuscript.

Go Kimura has received honoraria from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Pfizer.

Koki Kabu is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Yohei Tajima is an employee of Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Mototsugu Oya has received honoraria from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Pfizer.

Conflict of interest

Yoshihiko Tomita has received consultancy/advisory fees from Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Taiho; and honoraria from Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis and Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Satoshi Fukasawa, Kazuyuki Numakura, Yutaka Sugiyama, Kazutoshi Yamana, Sei Naito do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:354–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heng DY, Mackenzie MJ, Vaishampayan UN, et al. Primary anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma: clinical characteristics, risk factors, and subsequent therapy. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1549–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seidel C, Busch J, Weikert S, et al. Progression free survival of first line vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy is an important prognostic parameter in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:1023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim SH, Hwang IG, Ji JH, et al. Intrinsic resistance to sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishihara H, Kondo T, Yoshida K, et al. Time to progression after first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor predicts survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving second-line molecular-targeted therapy. Urol Oncol 2017;35:542.e1–542.e1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harada K, Nozawa M, Uemura M, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with unresectable or metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Japan. Int J Urol 2019;26:202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McDermott DF, Drake CG, Sznol M, et al. Survival, durable response, and long-term safety in patients with previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2013–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammers HJ, Plimack ER, Infante JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the CheckMate 016 study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3851–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomita Y, Fukasawa S, Shinohara N, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: Japanese subgroup analysis from the CheckMate 025 study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2017;47:639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomita Y, Fukasawa S, Shinohara N, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: Japanese subgroup 3-year follow-up analysis from the phase III CheckMate 025 study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2019;49:506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1277–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1370–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tomita Y, Kondo T, Kimura G, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in previously untreated advanced renal-cell carcinoma: analysis of Japanese patients in CheckMate 214 with extended follow-up. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2020;50:12–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albiges L, Powles T, Staehler M, et al. Updated European Association of Urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: immune checkpoint inhibition is the new backbone in first-line treatment of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2019;76:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:706–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network [Internet]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Kidney Cancer (Version 1.2021). 2019[cited 15 May 2020]: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

- 19. Albiges L, Fay AP, Xie W, et al. Efficacy of targeted therapies after PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2580–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nadal R, Amin A, Geynisman DM, et al. Safety and clinical activity of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors after programmed cell death 1 inhibitor treatment in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barata PC, De Liano AG, Mendiratta P, et al. The efficacy of VEGFR TKI therapy after progression on immune combination therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2018;119:160–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Auvray M, Auclin E, Barthelemy P, et al. Second-line targeted therapies after nivolumab-ipilimumab failure in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2019;108:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah AY, Kotecha RR, Lemke EA, et al. Outcomes of patients with metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma treated with second-line VEGFR-TKI after first-line immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer 2019;114:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ornstein MC, Pal SK, Wood LS, et al. Individualised axitinib regimen for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma after treatment with checkpoint inhibitors: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dudani S, Graham J, Wells JC, et al. First-line immuno-oncology combination therapies in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: results from the international metastatic renal-cell carcinoma database consortium. Eur Urol 2019;76:861–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graham J, Shah AY, Wells JC, et al. Outcomes of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy after immuno-oncology checkpoint inhibitors. Eur Urol Oncol 2019;S2588-931130160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Powles T, Motzer RJ, Escudier B, et al. Outcomes based on prior therapy in the phase 3 METEOR trial of cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2018;119:663–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Numakura K, Horikawa Y, Kamada S, et al. Efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective multicenter analysis. Mol Clin Oncol 2019;11:320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, et al. Efficacy of axitinib after nivolumab failure in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. In Vivo 2020;34:1541–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rini BI, Melichar B, Ueda T, et al. Axitinib with or without dose titration for first-line metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2011;378:1931–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Motzer RJ, Porta C, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Dovitinib versus sorafenib for third-line targeted treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:286–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 2010;116:4256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma of poor or intermediate risk: the alliance A031203 CABOSUN trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1116–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1103–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uemura M, Tomita Y, Miyake H, et al. Avelumab plus axitinib vs sunitinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma: Japanese subgroup analysis from JAVELIN renal 101. Cancer Sci 2020;111:907–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Costantini A, Corny J, Fallet V, et al. Efficacy of next treatment received after nivolumab progression in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. ERJ Open Res 2018;4:00120-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Harada D, Takata K, Mori S, et al. Previous immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment to increase the efficacy of docetaxel and ramucirumab combination chemotherapy. Anticancer Res 2019;39:4987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kato R, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Propensity score-weighted analysis of chemotherapy after PD-1 inhibitors versus chemotherapy alone in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (WJOG10217L). J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Osa A, Uenami T, Koyama S, et al. Clinical implications of monitoring nivolumab immunokinetics in non-small cell lung cancer patients. JCI Insight 2018;3:e59125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Facchini G, Rossetti S, Berretta M, et al. Second line therapy with axitinib after only prior sunitinib in metastatic renal cell cancer: Italian multicenter real world SAX study final results. J Transl Med 2019;17:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matias M, Le Teuff G, Albiges L, et al. Real world prospective experience of axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma in a large comprehensive cancer Centre. Eur J Cancer 2017;79:185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Miyake H, Harada KI, Ozono S, et al. Assessment of efficacy, safety, and quality of life of 124 patients treated with axitinib as second-line therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: experience in real-world clinical practice in Japan. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2017;15:122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Becker A, Crombag L, Heideman DAK, et al. Retreatment with erlotinib: regain of TKI sensitivity following a drug holiday for patients with NSCLC who initially responded to EGFR-TKI treatment. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McDermott DF, Rini BI, Motzer RJ, et al. Treatment-free survival after discontinuation of first-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab or sunitinib in intention-to-treat and IMDC favorable-risk patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma from CheckMate 214. Genitourinary Cancers Symposium 2019; abstract No. 564. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.