Abstract

Background

Since the first reports of COVID-19 infection, the foremost requirement has been to identify a treatment regimen that not only fights the causative agent but also controls the associated complications of the infection. Due to the time-consuming process of drug discovery, physicians have used readily available drugs and therapies for treatment of infections to minimize the death toll.

Objective

The aim of this study is to provide a snapshot analysis of the major drugs used in a cohort of 1562 Pakistani patients during the period from May to July 2020, when the first wave of COVID-19 peaked in Pakistan.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed to provide an overview of the major drugs used in a cohort of 1562 patients with COVID-19 admitted to the four major tertiary-care hospitals in the Rawalpindi-Islamabad region of Pakistan during the peak of the first wave of COVID-19 in the country (May-July 2020).

Results

Antibiotics were the most common choice out of all the therapies employed, and they were used as first line of treatment for COVID-19. Azithromycin was the most prescribed drug for treatment. No monthly trend was observed in the choice of antibiotics, and these drugs appeared to be a random but favored choice throughout the months of the study. It was also noted that even antibiotics used for multidrug resistant infections were prescribed irrespective of the severity or progression of the infection. The results of the analysis are alarming, as this approach may lead to antibiotic resistance and complications in immunocompromised patients with COVID-19. A total of 1562 patients (1064 male, 68.1%, and 498 female, 31.9%) with a mean age of 47.35 years (SD 17.03) were included in the study. The highest frequency of patient hospitalizations occurred in June (846/1562, 54.2%).

Conclusions

Guidelines for a targeted treatment regime are needed to control related complications and to limit the misuse of antibiotics in the management of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, antibiotics, Pakistan, multidrug resistant infections, antibiotic resistance, first wave

Introduction

In December 2019, a viral outbreak of pneumonia was reported in a city in China in December 2019 [1]; this outbreak would have a substantial impact worldwide. Shortly after the first reports of the disease, it rapidly spread globally and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in 2020 [2]. The official name for this pneumonia-like disease is COVID-19, and the virus that causes it is called SARS-COV-2 [3]. The pathological conditions of COVID-19 infection were classified into five categories, from asymptomatic to critical, according to clinical manifestations [4]. It has already been reported that approximately one-fifth of the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are admitted to intensive care units due to difficulty in breathing or acute hypoxemic respiratory failure [5-8].

More than a year has passed since the initial outbreak, and SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread globally, crippling the economy, damaging health, and causing mortality each day; the current count has reached a staggering 112.65 million confirmed infections and 2.49 million deaths [9,10]. With the rapid spread of COVID-19 across the world, prompt diagnostic tools, readily available repurposable drugs, and effective containment measures to control SARS-CoV-2 infection are of paramount importance. The pandemic has also exposed inadequate research and health infrastructures globally, especially in countries such as Pakistan, where basic health care necessities were scarce when the infection reached its peak in June 2020 [11,12].

The second wave of COVID-19 infections being reported by various countries, including Pakistan, is proving to be even more challenging to address because of the severity of COVID-19–related complications, which vary with gender and age [13-15], underlying diseases and disorders, and even delay in hospital admissions [16,17]. Human behavior is also a major factor causing the resurge in infections [18]. The relationship between adherence to precautions and cases of COVID-19 is clear: in areas where fewer people wear masks and more people gather indoors to eat, drink, celebrate, socialize, and observe religious practices, even if only with family, cases are on the rise [19-21].

With overburdened health care systems and an increasing number of infections among medical staff, the ultimate way to overcome this pandemic remains the discovery of an effective vaccine. Although pharmaceutical companies worldwide have introduced several vaccines to date [22,23], effectively vaccinating a sufficiently large number of people all over the world is a lengthy process [24,25]. Moreover, with reports of new strains from different regions, the effectiveness of some of these vaccines against multiple mutant strains shows mixed results [26]. As a result, repurposing existing drugs to target SARS-CoV-2 and treat COVID-19–associated symptoms still appears to be a logical scientific approach at the moment to contain this pandemic. Identifying and appropriating an effective combination of drugs from the available repertoire is a challenge in itself. The hit-and-trial method is dangerous but inevitable in the current situation. Small-scale studies were performed in which a few drugs were reported to be effective; however, these drugs were later proved to result in no significant difference in clinical outcomes [27-29].

Currently, as observed in various reports globally as well as in Pakistan, supportive treatment, mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation remain the primary treatment choices for medical practitioners. Therapeutic options that are being considered and used include antiviral, antiparasitic, and anti-inflammatory medications; interferon therapy; convalescent plasma therapy; hyperimmunoglobulin; oligonucleotide-based therapies; and, rarely, RNA interference and mesenchymal stem cell therapy [30-32].

In this study, we explored the use of antibiotic and antiviral drugs for the treatment of patients admitted during the peak of the first wave of COVID-19 in Pakistan (May-July 2020). Directions for treatment of the disease during the first wave phase were not very clear, and many necessities, including drugs, were out of stock in local markets due to lockdowns, high demand, limited stocks, and closure of borders.

Methods

Study Design

Clinical data from 1812 confirmed patients with COVID-19 admitted to four major tertiary care hospitals in Pakistan, that is, Pakistan Air Force Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences Hospital, Islamabad, Holy Family Hospital, Rawalpindi, and Benazir Bhutto Shaheed Hospital, Rawalpindi, were retrospectively collected during the period from February to August 2020.

Patient Selection, Timeline, and Data Collection

Confirmed COVID-19 cases were defined as patients with a positive polymerase chain reaction test for COVID-19 from nasal and oropharyngeal swab samples taken at the time of admission to the hospital. Patients with incomplete data were excluded. Descriptive data of 1562 patients admitted during the months of May to July 2020 were abstracted and analyzed accordingly. The data included information about the patients’ age, gender, dates of admission and discharge (or death), medical history, presenting signs and symptoms, initial categorization of COVID-19 (mild, moderate, severe, and critical), and types of therapeutic agents (including but not limited to use of antibiotics, antimalarials, antivirals, antiparasitics, anticoagulants, and corticosteroids) used for treatment and management of COVID-19 during their hospital stay.

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corporation) and Stata 16.1 (StataCorp LLC). Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages [33,34]. Chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests were used to compare percentages wherever appropriate. This retrospective cohort study was approved by the ethics review board of Rawalpindi Medical University. Data were collected with approval of the National Institute of Health (NIH), Pakistan.

Results

A total of 1562 patients were included in the study; 1064 (68.1%) were male and 498 (31.9%) were female, with a mean age of 47.35 years (SD 17.03). The basic demographic characteristics of the hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and their distribution across the hospitals are shown in Table 1. The frequencies of admission during the months of May, June, and July 2020 were 37.9% (592/1562), 54.2% (846/1562), and 7.9% (124/1562), respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (N=1562).

| Characteristic | Value | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47.35 (17.03) | ||

| Gender | |||

|

|

Male | 1064 (68.1) | |

|

|

Female | 498 (31.9) | |

| Admission frequency of patients across hospitals, n (%) | |||

|

|

Benazir Bhutto Shaheed Hospital, Rawalpindi | 813 (52.0) | |

|

|

Holy Family Hospital, Rawalpindi | 470 (30.1) | |

|

|

Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences Hospital, Islamabad | 135 (8.3) | |

|

|

Pakistan Air Force Hospital, Islamabad | 144 (9.2) | |

| Admission frequency of patients across the period of the study, n (%) | |||

|

|

May 2020 | 592 (37.9) | |

|

|

June 2020 | 846 (54.2) | |

|

|

July 2020 | 124 (7.9) | |

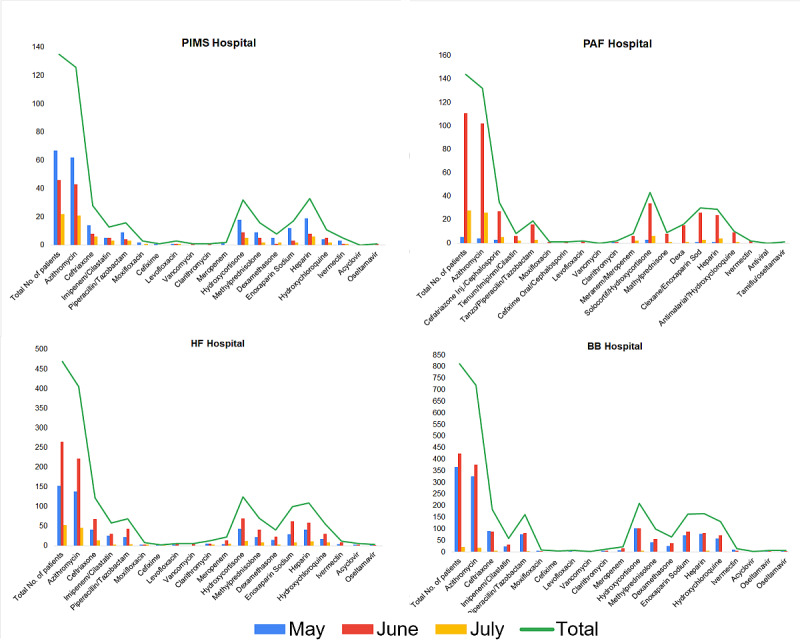

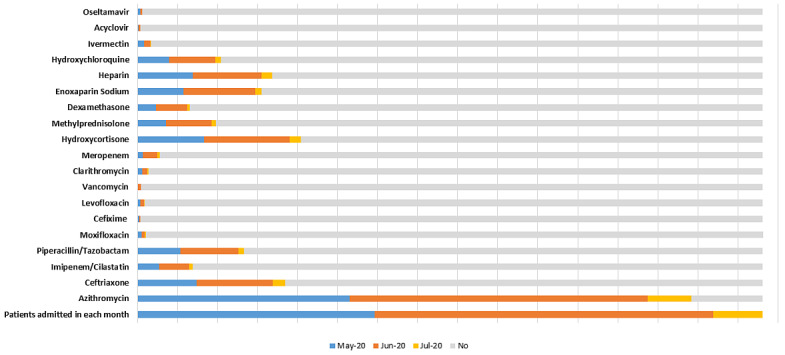

Of the 19 drugs reportedly used for treatment of COVID-19 and management of COVID-19–related symptoms, the most frequently used antibiotic was azithromycin (1384/1562, 88.6%), followed by ceftriaxone (369/1562, 23.6%). Anticoagulants such as heparin (337/1562, 21.6%) and enoxaparin sodium (310/1562, 19.8%) and steroids such as hydrocortisone (409/1562, 25.7%) were also among the 5 most frequently used drugs. The relative distribution of administered drugs across hospitals during the first wave of COVID-19 is given in Figure 1. The load of patients at each hospital was different; however, the trends of the regimens used were similar. The peak of the first wave of COVID-19 in Rawalpindi-Islamabad was observed during June 2020. The trends of drug use during the first wave of COVID-19 in Pakistan are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 1.

Hospital-wise relative distribution of different drugs administered to patients with COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic in Pakistan. BB: Benazir Bhutto; HF: Holy Family; PAF: Pakistan Air Force; PIMS: Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences.

Figure 2.

Relative distributions of different drugs administered to patients with COVID-19 in each month during the first wave of the pandemic (May-July 2020) in Pakistan.

Table 2.

Distributions of different drugs administered to patients with COVID-19 (N=1562) in each month during the first wave of the pandemic (May-July 2020) in Pakistan.

| Drug | Prescriptions, n (%) | |||

|

|

Patients admitted in May 2020 (n=592) | Patients admitted in June 2020 (n=846) | Patients admitted in July 2020 (n=124) | Patients not prescribeda |

| Azithromycin | 531 (89.7) | 743 (87.8) | 110 (88.7) | 178 (11.4) |

| Ceftriaxone | 148 (25) | 191 (22.6) | 30 (24.2) | 1193 (76.4) |

| Imipenem/cilastatin | 55 (9.3) | 74 (8.7) | 10 (8.1) | 1423 (91.1) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 107 (18.1) | 145 (17.1) | 14 (11.3) | 1296 (83) |

| Moxifloxacin | 11 (1.9) | 7 (0.8) | 3 (2.4) | 1542 (98.7) |

| Cefixime | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1554 (99.5) |

| Levofloxacin | 8 (1.4) | 9 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 1544 (98.8) |

| Vancomycin | 1 (0.2) | 8 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1553 (99.4) |

| Clarithromycin | 12 (2.0) | 13 (1.5) | 3 (2.4) | 1534 (98.2) |

| Meropenem | 14 (2.3) | 35 (4.1) | 7 (5.6) | 1506 (96.4) |

| Hydrocortisone | 166 (28) | 214 (25.3) | 29 (23.4) | 1153 (73.8) |

| Methylprednisolone | 72 (12.2) | 113 (13.4) | 12 (9.7) | 1365 (87.4) |

| Dexamethasone | 46 (7.8) | 78 (9.2) | 6 (4.8) | 1432 (91.7) |

| Enoxaparin sodium | 115 (19.4) | 180 (21.3) | 15 (12.1) | 1252 (80.2) |

| Heparin | 138 (23.3) | 172 (20.3) | 27 (21.8) | 1225 (78.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 79 (13.3) | 116 (13.7) | 13 (10.5) | 1354 (86.7) |

| Ivermectin | 17 (2.9) | 16 (1.9) | 1 (0.8) | 1528 (97.8) |

| Acyclovir | 3 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1554 (99.5) |

| Oseltamivir | 7 (1.2) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1550 (99.2) |

aPercentages calculated based on the total number of patients across 3 months (N=1562).

Although the load over hospital varied during the 3 months, the choices of drugs used to treat COVID-19 remained the same. The frequencies and percentages of the prescription of these drugs are given in Table 3. Different combinations were used, and these combinations included drugs from various categories, such as anticoagulants, corticosteroids, and antibiotics.

Table 3.

Drugs used during the first wave of COVID-19 to treat patients (N=1562) in all four hospitals under study.

| Drug | Value, n (%) | |

| Antibiotics | ||

|

|

Azithromycin | 1384 (88.6) |

|

|

Ceftriaxone | 369 (23.6) |

|

|

Cefixime | 8 (0.51) |

|

|

Meropenem | 56 (3.6) |

|

|

Imipenem/cilastatin | 139 (8.9) |

|

|

Piperacillin/tazobactam | 266 (17.0) |

|

|

Vancomycin | 9 (0.6) |

|

|

Clarithromycin | 28 (1.8) |

|

|

Moxifloxacin | 21 (1.3) |

|

|

Levofloxacin | 18 (1.1) |

| Corticosteroids | ||

|

|

Hydrocortisone | 409 (26.2) |

|

|

Methylprednisolone | 197 (12.6) |

|

|

Dexamethasone | 130 (8.3) |

| Anticoagulants | ||

|

|

Enoxaparin sodium | 310 (19.8) |

|

|

Heparin | 337 (21.6) |

| Antimalarial | ||

|

|

Hydroxychloroquine | 208 (13.3) |

| Antiparasitic | ||

|

|

Ivermectin | 34 (2.2) |

| Antiviral | ||

|

|

Acyclovir | 8 (0.5) |

|

|

Oseltamivir | 12 (0.8) |

Discussion

Principal Findings

Our results show that the highest proportion of admissions occurred in the month of June (846/1562, 54.2%), just after Eid-ul-Fitr (the Muslim festival, which was held on May 23 and 24 in 2020). It is worth noting that this was the time when the first wave of COVID-19 infections was at its peak in Pakistan; however, the trend of the treatment regimen remained the same during the period of the first wave [35-37]. However, after this period, a dramatic decrease in infections was observed due to effective precautions and regulations imposed by the government, including “smart lockdown” in potential hotspots, implementation of standard operating procedures, and closure of academic buildings [38].

Our study reports the use of up to 10 antibiotics of different classes. The effectiveness of the use of antibiotics for the treatment of COVID-19 is debatable, and evidence of their direct inhibitory effect on viral replication or pathogenesis remains to be proved. These antibiotics are generally used to treat upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, and other infections caused by opportunistic bacteria due to low immunity during viral infection. Azithromycin was widely used because it is a broad-spectrum antibiotic and can treat chest infections, including pneumonia, which is also a manifestation of COVID-19 infection; infections of the nose and throat, such as sinus infections (sinusitis); skin infections; Lyme disease; and some sexually transmitted infections [39].

In addition to antibiotics, some other frequently used drugs were anticoagulants (heparin and enoxaparin sodium) and corticosteroids (hydrocortisone and methylprednisolone). Use of anticoagulants and steroids is indicated for reduction of the inflammatory effects of SARS-CoV-2, which helps control disease progression to a limited extent; however, no succinct combination was observed in terms of treating COVID-19 [40].

Challenges and Shortcomings on the Therapeutic Front

Despite the fact that the antibiotics supported the combined therapies used against COVID-19, there is still no evidence that supports the use of these antibiotics to treat viral infection by health care professionals in Pakistan. Other drugs, such as anticoagulants and steroids, were also used as supportive therapy; however, there is a need to establish standard guidelines to treat patients with COVID-19–related complications. The experimental hit-and-trial approach of various combinations of drugs and the alarming frequency with which antibiotics were used will eventually lead to antibiotic resistance in the human population. One of the major challenges faced by health care professionals globally was the reliability on available therapies against the newly introduced virus. Mutations in RNA viruses are more frequent compared to those in DNA species; COVID-19, being an RNA virus, is a great threat to humanity. Modern research is necessary to study mutable infectious agents to develop multifaceted therapies to target the pathways of infection.

Conclusion

This study highlights the trend of drugs used to treat COVID-19 infections in early the months of the pandemic across Pakistan. The use of antibiotics by health care professionals to treat COVID-19 is questionable. It signifies the lack of specific guidelines that must be followed by all hospitals in terms of treatment regimens, and organizations such as the NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must not only provide guidelines to address the pandemic but also ensure that those guidelines are strictly being followed throughout the country. This study reveals the weaknesses in the health care infrastructure and the inadequacy of hospitals and staff in Pakistan. With the second wave emerging in various countries and a mutant strain of SARS-CoV-2 causing infections, it is important to ensure that the standard operating procedures are being strictly followed, a proper treatment guideline is provided, and drugs used for symptomatic treatment are monitored to avoid antibiotic resistance in the future.

Limitations of the Study

The study was limited to the Rawalpindi and Islamabad regions of Pakistan, which are large cities with relatively good health care facilities and checks and balances on health care practitioners. Data from other cities, especially small towns and rural regions, can be helpful in analyzing the misuse of medicines prescribed for treatment of COVID-19–related symptoms and complications. The study was performed on patients admitted in mid-2020 during the peak of the first wave, and a better analysis could be performed if data were taken from the months of the second wave as well. Collecting data during the first wave was difficult due to limited access to COVID-19 wards and a shortage of personal protection equipment. The number of subjects included in the study was under 2000; comprehensive information could be gathered from a large population size.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Global Health Development/Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network for their support. We would also like to acknowledge the support of NIH, Islamabad. We also wish to acknowledge our colleagues for their time and invaluable contributions to this ongoing study in the region.

Abbreviations

- NIH

National Institute of Health

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Zhu H, Wei L, Niu P. The novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020;5:6. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6. https://ghrp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41256-020-00135-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layne SP, Hyman JM, Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. New coronavirus outbreak: framing questions for pandemic prevention. Sci Transl Med. 2020 Mar 11;12(534) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai C, Shih T, Ko W, Tang H, Hsueh P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar;55(3):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32081636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomo S, Karli S, Dharmalingam K, Yadav D, Sharma P. The clinical laboratory: a key player in diagnosis and management of COVID-19. EJIFCC. 2020 Nov;31(4):326–346. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33376473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, Liu L, Shan H, Lei C, Hui DS, Du B, Li L, Zeng G, Yuen K, Chen R, Tang C, Wang T, Chen P, Xiang J, Li S, Wang J, Liang Z, Peng Y, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y, Peng P, Wang J, Liu J, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z, Qiu S, Luo J, Ye C, Zhu S, Zhong N. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 Mar 17;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32031570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Barnaby Douglas P, Becker Lance B, Chelico John D, Cohen Stuart L, Cookingham Jennifer, Coppa Kevin, Diefenbach Michael A, Dominello Andrew J, Duer-Hefele Joan, Falzon Louise, Gitlin Jordan, Hajizadeh Negin, Harvin Tiffany G, Hirschwerk David A, Kim Eun Ji, Kozel Zachary M, Marrast Lyndonna M, Mogavero Jazmin N, Osorio Gabrielle A, Qiu Michael, Zanos Theodoros P. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020 May 26;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32320003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr 07;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronavirus. Worldometer. [2021-02-24]. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- 10.Subbaraman N. Why daily death tolls have become unusually important in understanding the coronavirus pandemic. Nature. 2020 Apr 09; doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reporter T. Covid infection in Punjab reaches June peak level. Dawn News. 2020. Dec 08, [2021-05-17]. https://www.dawn.com/news/1594625.

- 12.Saeed U, Sherdil K, Ashraf U, Mohey-Ud-Din G, Younas I, Butt HJ, Ahmad SR. Identification of potential lockdown areas during COVID-19 transmission in Punjab, Pakistan. Public Health. 2021 Jan;190:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.10.026. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33338902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cacciapaglia G, Cot C, Sannino F. Second wave COVID-19 pandemics in Europe: a temporal playbook. Sci Rep. 2020 Sep 23;10(1):15514. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72611-5. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72611-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. 2020 May 25;11(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9. https://bsd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tadiri CP, Gisinger T, Kautzy-Willer Alexandra, Kublickiene K, Herrero MT, Raparelli V, Pilote L, Norris CM, GOING-FWD Consortium The influence of sex and gender domains on COVID-19 cases and mortality. CMAJ. 2020 Sep 08;192(36):E1041–E1045. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200971. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32900766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison SL, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Lane DA, Underhill P, Lip GYH. Comorbidities associated with mortality in 31,461 adults with COVID-19 in the United States: a federated electronic medical record analysis. PLoS Med. 2020 Sep 10;17(9):e1003321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003321. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alaa A, Qian Z, Rashbass J, Benger J, van der Schaar M. Retrospective cohort study of admission timing and mortality following COVID-19 infection in England. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 23;10(11):e042712. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042712. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=33234660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Crockett MJ, Crum AJ, Douglas KM, Druckman JN, Drury J, Dube O, Ellemers N, Finkel EJ, Fowler JH, Gelfand M, Han S, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Kitayama S, Mobbs D, Napper LE, Packer DJ, Pennycook G, Peters E, Petty RE, Rand DG, Reicher SD, Schnall S, Shariff A, Skitka LJ, Smith SS, Sunstein CR, Tabri N, Tucker JA, Linden SVD, Lange PV, Weeden KA, Wohl MJA, Zaki J, Zion SR, Willer R. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020 May;4(5):460–471. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed MS, Yunus FM. Trend of COVID-19 spreads and status of household handwashing practice and its determinants in Bangladesh - situation analysis using national representative data. Int J Environ Health Res. 2020 Sep 13;:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2020.1817343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung CC, Cheng KK, Lam TH, Migliori GB. Mask wearing to complement social distancing and save lives during COVID-19. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020 Jun 01;24(6):556–558. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein E, Ragazzoni L, Burkle F, Allen M, Hogan D, Della Corte F. Delayed primary and specialty care: the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic second wave. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020 Jun;14(3):e19–e21. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.148. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32438940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaway E. What Pfizer's landmark COVID vaccine results mean for the pandemic. Nature. 2020 Nov 09; doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaway E. Coronavirus vaccine trials have delivered their first results—but their promise is still unclear. Nature. 2020 May;581(7809):363–364. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson Yvonne. What is the world doing about COVID-19 vaccine acceptance? J Health Commun. 2020 Oct 02;25(10):757–760. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2020.1868628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khamsi R. If a coronavirus vaccine arrives, can the world make enough? Nature. 2020 Apr 9;580(7805):578–580. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callaway E. Why Oxford's positive COVID vaccine results are puzzling scientists. Nature. 2020 Dec 23;588(7836):16–18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03326-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magagnoli J, Narendran S, Pereira F, Cummings TH, Hardin JW, Sutton SS, Ambati J. Outcomes of hydroxychloroquine usage in United States veterans hospitalized with COVID-19. Med (N Y) 2020 Dec 18;1(1):114–127.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.medj.2020.06.001. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32838355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina J, Delaugerre C, Le Goff J, Mela-Lima B, Ponscarme D, Goldwirt L, de Castro N. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Med Mal Infect. 2020 Jun;50(4):384. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.006. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32240719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahévas Matthieu, Tran V, Roumier M, Chabrol A, Paule R, Guillaud C, Fois E, Lepeule R, Szwebel T, Lescure F, Schlemmer F, Matignon M, Khellaf M, Crickx E, Terrier B, Morbieu C, Legendre P, Dang J, Schoindre Y, Pawlotsky J, Michel M, Perrodeau E, Carlier N, Roche N, de Lastours V, Ourghanlian C, Kerneis S, Ménager Philippe, Mouthon L, Audureau E, Ravaud P, Godeau B, Gallien S, Costedoat-Chalumeau N. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. BMJ. 2020 May 14;369:m1844. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1844. http://www.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32409486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YJ, Farooq J, Cho J, Sadanandan N, Cozene B, Gonzales-Portillo B, Saft M, Borlongan MC, Borlongan MC, Shytle RD, Willing AE, Garbuzova-Davis S, Sanberg PR, Borlongan CV. Fighting the war against COVID-19 via cell-based regenerative medicine: lessons learned from 1918 Spanish Flu and other previous pandemics. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2021 Feb 13;17(1):9–32. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10026-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32789802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borlongan MC, Borlongan MC, Sanberg PR. The disillusioned comfort with COVID-19 and the potential of convalescent plasma and cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720940719. doi: 10.1177/0963689720940719. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0963689720940719?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siam MHB, Nishat NH, Ahmed A, Hossain MS. Stopping the COVID-19 pandemic: a review on the advances of diagnosis, treatment, and control measures. J Pathog. 2020;2020:9121429. doi: 10.1155/2020/9121429. doi: 10.1155/2020/9121429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barkhordari M, Padyab M, Hadaegh F, Azizi F, Bozorgmanesh M. Stata modules for calculating novel predictive performance indices for logistic models. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Jan;14(1):e26707. doi: 10.5812/ijem.26707. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27279830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnard P. Nice vital statistics SPSS/PC + and SPSS for Windows: A Beginner's Guide to Data Analysis, 2nd edition. Foster JJ et al 1993 Price: Supplier: Computer Manuals , Birmingham. £14.95 021-706-6000. Nurs Stand. 1994 Feb 02;8(19):53. doi: 10.7748/ns.8.19.53.s61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noreen K, Umar M, Sabir SA, Rehman R. Outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) in Pakistan: psychological impact and coping strategies of health care professionals. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36(7):1478–1483. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.7.2988. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33235560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah PT, Xing L. Puzzling increase and decrease in COVID-19 cases in Pakistan. New Microbes New Infect. 2020 Nov;38:100791. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100791. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2052-2975(20)30143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussain I, Majeed A, Saeed H, Hashmi FK, Imran I, Akbar M, Chaudhry MO, Rasool MF. A national study to assess pharmacists' preparedness against COVID-19 during its rapid rise period in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241467. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waris A, Atta UK, Ali M, Asmat A, Baset A. COVID-19 outbreak: current scenario of Pakistan. New Microbes New Infect. 2020 May;35:100681. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100681. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2052-2975(20)30033-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bleyzac N, Goutelle S, Bourguignon L, Tod M. Azithromycin for COVID-19: more than just an antimicrobial? Clin Drug Investig. 2020 Aug;40(8):683–686. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00933-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32533455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gavriatopoulou M, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Korompoki E, Fotiou D, Migkou M, Tzanninis I, Psaltopoulou T, Kastritis E, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA. Emerging treatment strategies for COVID-19 infection. Clin Exp Med. 2021 May;21(2):167–179. doi: 10.1007/s10238-020-00671-y. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33128197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]