Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE) is characterized by new-onset hypertension in association with elevated natural killer (NK) cells and inflammatory cytokines, which are likely culprits for decreased fetal weight during PE pregnancies. As progesterone increases during normal pregnancy, it stimulates progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF). PIBF has been shown to decrease inflammation and cytolytic NK cells, both of which are increased during PE. We hypothesized that PIBF reduces inflammation as a mechanism to improve hypertension in the preclinical reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of PE. PIBF (2.0 µg/mL) was administered intraperitoneally on gestational day 15 to either RUPP or normal pregnant (NP) rats. On day 18, carotid catheters were inserted. Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and samples were collected on day 19. MAP in NP rats (n = 11) was 100 ± 2 mmHg and 105 ± 3 mmHg in NP + PIBF rats (n = 8) and 122 ± 1 mmHg in RUPP rats (n = 10), which improved to 110 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP + PIBF rats (n = 11), P < 0.05. Pup weight was 2.4 ± 0.1 g in NP, 2.5 ± 0.1 g in NP + PIBF, 1.9 ± 0.1 g in RUPP, and improved to 2.1 ± 0.1 g in RUPP + PIBF rats. Circulating and placental cytolytic NK cells, IL-17, and IL-6 were significantly reduced while IL-4 and T helper (TH) 2 cells were significantly increased in RUPP rats after PIBF administration. Importantly, vasoactive pathways preproendothelin-1, nitric oxide, and soluble fms-Like tyrosine Kinase-1 (sFlt-1) were normalized in RUPP + PIBF rats compared with RUPP rats, P < 0.05. Our findings suggest that PIBF normalized IL-4/TH2 cells, which was associated with improved inflammation, fetal growth restriction, and blood pressure in the RUPP rat model of PE.

Keywords: hypertension, PIBF, preeclampsia, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) is characterized by new-onset hypertension during pregnancy concurrent with single- or multiorgan system dysfunction (1). Currently the only treatment option for PE is delivery. Preterm gestations complicated by PE often necessitate preterm delivery for maternal or fetal indications, causing PE to remain a leading cause of fetal morbidity and mortality. The importance of continued drug discovery for the treatment and prevention of PE cannot be understated.

Maintenance of proper immune regulation is essential for normal healthy pregnancy. PE is associated with an imbalance among CD4+ T lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and inflammatory cytokines, which are likely culprits for decreased fetal weight during PE pregnancies (2–5). Evidence for a shift toward proinflammatory CD4+ T helper (TH) 1 cells and away from CD4+ Treg and CD4+ TH2 exist in PE (6–9). Similarly, there are greater numbers of cytolytic NK when compared with uterine NK cells during PE (10, 11).

Interestingly, 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC) is commonly used for cessation of recurrent preterm labor in pregnancies not complicated by PE (12–15). Most recent published data from PROLONG study have showed that 17-OHPC did not reduce recurrent preterm labor and does not promote any increase of fetal death (16). Importantly, we have previously shown that 17-OHPC improves clinical signs of PE in the preclinical reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) rat model of PE (4, 17, 18). However, the exact mechanism whereby progesterone improves the pathophysiology of PE has never been fully determined.

In humans, progesterone is crucial for establishing and maintaining pregnancy. We have previously shown that PE is associated with lower circulating progesterone levels in our preeclamptic population in Mississippi (19). The immuno-modulating effect of progesterone is determined by either availability of the hormone or progesterone sensitivity of the lymphocytes (20). Activated lymphocytes during normal pregnancy express progesterone receptors, which enable progesterone to induce a protein called progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF), which suppresses lymphocytes proliferation, Nk cells activation, and inflammation (21–23). During normal pregnancy the concentration of PIBF continuously increases from the 6th to the 37th gestational wk. After the 41st wk, PIBF concentrations dramatically decrease (24, 25). Although PIBF is characteristic of normal human pregnancy, its concentration is reduced in pregnancy complications such as preterm birth and in those women at risk of miscarriage (24, 25). However, the role of PIBF during PE is not fully understood.

Importantly, previous studies revealed that PIBF upregulates TH2 cytokine, which could shift TH1 to TH2 cytokine bias via stimulating IL-4 signaling and mechanisms. Indeed, PIBF-positive lymphocytes decrease in preterm labor and miscarriage (26). Moreover, several studies suggest that PIBF decreases NK cell cytolytic activation in vitro and that PIBF inhibits cytolytic proteins from decidua lymphocytes and reduces the deleterious effect of high NK activity on murine pregnancy (27). Although PIBF has been shown to act by stimulating IL-4/TH2, both of which are reduced during PE and increased during normal pregnancy, a role for PIBF to stimulate IL-4/TH2 as a mechanism to improve the pathophysiology associated with PE has not been fully examined.

This current study was designed to test the hypothesis that PIBF supplementation stimulates IL-4/TH2 as a mechanism to decrease other inflammatory cytokines and NK activation. We have previously shown the T cells and cytokines stimulate the endothelin-1 (ET-1), nitric oxide (NO), and soluble fms-Like tyrosine Kinase-1 (sFlt-1) during pregnancy; therefore, we measured these vasoactive pathways in this study to determine if the change in T cells and cytokines in response to PIBF would also change these vasoactive pathways. Changes in such pathways would improve maternal blood pressure and possibly fetal growth restriction in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure during pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN) were used in this study. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room (23°C) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to standard rat chow and water. All experimental procedures executed in this study were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use and care of animals. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Surgical procedures were carried out under appropriate anesthesia, and analgesics were given postoperatively as needed, under the supervision of the veterinary staff. In general inhalant anesthetics are safer than injectable anesthetics. Then, pregnant rats at gestational day 14, 15, and 18 were either exposed to 2.0% isoflurane in a humidified 100% oxygen carrier gas. The protocols have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reduction in Uterine Perfusion Pressure

Rat dams weighting ∼250–300 g were randomly assigned to either reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) or normal pregnant (NP) groups. Via a vertical midline incision, under isoflurane anesthesia, RUPP surgery was performed at day 14 of gestation on a subset of normal pregnant rats. At constrictive silver clip (0.203 mm) was placed on the aorta superior to the iliac bifurcation, and ovarian collateral circulation to the uterus was reduced with restrictive clips (0.100 mm) to the bilateral uterine arcades at the ovarian end. Carprofen (5 mg/kg) was administered via subcutaneous injection, once daily for 2–3 days following RUPP surgical procedure. Analgesics used to provide comfort for the surgical rats include 0.25% sensor care administered topically.

Administration of PIBF

A subset of RUPP and NP rats were injected with human recombinant PIBF diluted in sterile normal saline at day 15 of gestation. Human PIBF recombinant protein (MBS1308729; host: E Coli and purity: >90%, My BioSource, San Diego, CA) was diluted in normal saline and administered intraperitoneally as 0.5 cm3 solution of 2 μg/mL PIBF into either RUPP or NP rats.

Measurement of Mean Arterial Pressure

On day 18 of gestation, using isoflurane anesthesia, carotid arterial catheters were inserted for blood pressure measurements. The catheters inserted were V3 tubing (Scientific Commodities, Inc., Lake Havasu City, AZ), which is tunneled to the back of the neck and exteriorized. On day 19 of gestation, arterial blood pressure was analyzed after placing the rats in individual restraining cages. Arterial pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer (Cobe III tranducer CDX Sema) and recorded continuously for 45 min after a 30-min stabilization period as previously described (18). Subsequently, blood and tissues were collected.

Determination of Circulating and Placental NK Cell Populations Using Flow Cytometry

Circulating and placental populations of NK cells isolated on day 19 of gestation from all groups were quantified by flow cytometry. At the time of harvest, blood and placentas were collected. One placenta from each rat was homogenized, filtered, and resuspended in Rosswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI). Whole blood was collected in an EDTA tube and diluted with RPMI. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells and placental lymphocytes were isolated by centrifugation on a cushion of Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep, Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For flow cytometry analysis, single-cell suspension (1 × 106 cells) were stained after blocking with 10% goat and mouse serum. Antibodies used for flow cytometry were as follows: Anti-ANK61 (Abcam ab36392), Anti-ANK44, (Abcam ab36388) (28). As a negative control for each individual rat, cells were treated exactly as described above except they were incubated with isotype controls antibodies conjugated to FITC alone (anti-mouse IgG FITC (Abcam, ab97239). Lymphocytes were gated in the forward and side scatter plot. Cells that stained as ANK61+ were designated as total NK cells. Cells that stain as ANK44+ were designated as cytolytic NK cells. After doublet exclusion, the percent of positive-stained cells above the negative control (isotypes tubes) was collected for individual rats, and results were expressed as percentage of cells in the gated lymphocytes population (3). Flow cytometry was performed on the Miltenyi MACSQuant Analyzer 10 (Miltenyi) and analyzed using FlowLogic software (Innovai, Sydney, Australia).

Determination of Circulating and Placental CD4+ T Cells and TH2 Cells Using Flow Cytometry

The circulating and placental populations of CD4+ T cells and TH2 cells were quantified by flow cytometry from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and placenta as described previously (4, 29). Antibodies used for flow cytometry were as follows: anti-rat CD4 (BD No. 554647, BD PharMingen), FITC isotype control for mouse anti-rat CD4 (fluorescein isothiocyanate, BD No. 554843), anti-rat IL-4 (BD No. 555082), PE isotype control for anti-rat IL-4 (BD No. 554680), and anti-GATA3 from BD PharMingen (Cat. No. 560068) and Alexa Flour isotype control for anti-GATA 3 (BD No. 557783). As a negative control for each individual rat, cells were treated exactly as described above except they were incubated with anti-FITC, anti-PE, and anti-Alexa secondary antibodies alone. After doublet exclusion, the percent of positive-stained cells above the negative control (isotypes tubes) was collected for individual rats, and results were expressed as percentage of cells in the gated lymphocytes population using Miltenyi MACSQuant Analyzer 10 (Miltenyi) and FlowLogic software (Innovai, Sydney, Australia).

Determination of Circulating Cytokines

Plasma was analyzed for IL‐4, IL‐6, IL-10, and IL-17 using the Bio-Plex Pro rat TH1/TH2 panel (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA) supplemented with the IL-17 singleplex to quantify the cytokines according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of Renal Cortex Preproendothelin-1

Kidneys were weighed and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80˚C. Total renal cortex RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Protect Mini kit supplied by Qiagen as outlined in the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Real-time PCR was utilized, as previously described, to determine tissue renal cortex preproendothelin-1 (PPET-1) levels (30, 31). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 μg of RNA with Bio-Rad Iscript cDNA reverse transcriptase, and real-time PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad Sybre Green Supermix and iCycler. The following primer sequences, provided by Life technologies, were used for PPET as previously described: forward 1, ctaggtctaagcgatccttg, and reverse 1, tctttgtctgcttggc (32–34). Levels of mRNA were calculated using the mathematical formula for 2−ΔΔCt (2avg. Ct gene of interest − avg Ct β-actin) recommended by Applied Biosystems (Applied Biosystems User Bulletin, No. 2, 1997).

Determination of Circulating sFlt-1 Levels

Plasma collected from all pregnant rats was measured for sFlt-1 levels using commercial ELISA kits from R&D Systems (Quantikine) according the manufacturer's instructions. The minimal detectable levels for sFlt-1 was 15.2 pg/mL, with inter- and intraassay variability of 8.4% and 7.2%.

Determination of Circulating NO Levels

Plasma was used to measure circulating total nitrate-nitrite levels evaluated by Nitrate/Nitrite Colorimetric Assay Kit from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) following instructions outlined by the manufacturer. The interassay coefficient of variation is 3.4%, while intraassay coefficient of variation is 2.7%.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between groups were assessed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test as post hoc analysis. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Significant changes in TH2 cells were only seen with Student’s t test.

RESULTS

Administration of PIBF Blunted Hypertension and Improved Pup Weight in RUPP Rats

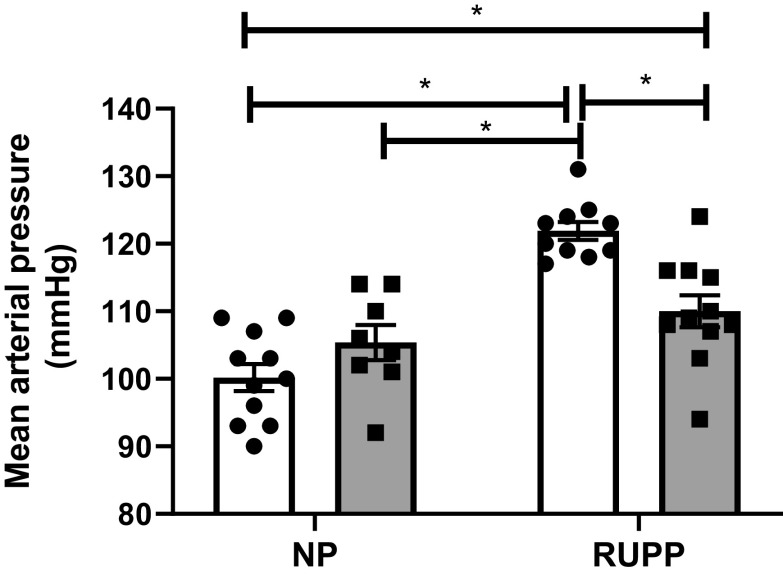

We have previously published that either MAP or pup weight was not different between NP or Sham-operated pregnant rats; therefore, Shams were not included in this study (4). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was not different between NP and NP + PIBF groups. MAP was significantly elevated in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure, RUPP rats, and was significantly decreased with PIBF supplementation. MAP in NP rats (n = 11) was 100 ± 2 mmHg, 105 ± 3 mmHg in NP + PIBF (n = 8), 122 ± 1 mmHg in RUPP rats (n = 10), which improved to 110 ± 2 mmHg in RUPP + PIBF (n = 11), P < 0.05, Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PIBF supplementation reduces mean arterial blood pressure in RUPP rats. On gestational day 14 (GD14), RUPP surgery was performed and on GD15 PIBF was given intraperitoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19, conscious mean arterial pressure was measured. NP: n = 11 rats, NP+PIBF: n = 8, RUPP: n = 10, RUPP+PIBF: n = 11. All data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. *P < 0.05. PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure.

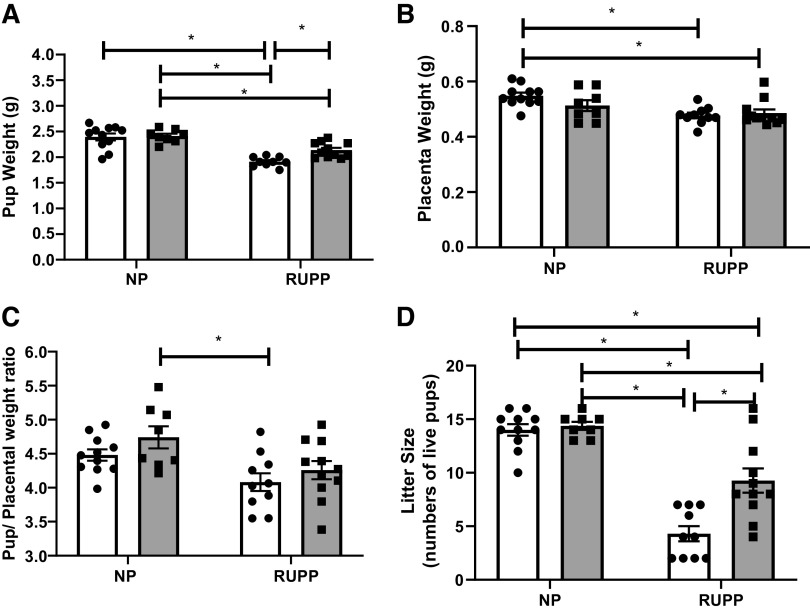

As in our previous studies with RUPP, pup weight in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure, RUPP rats, was significantly decreased compared with NP rats. PIBF significantly improved pup weight in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure. Pup weight was 2.4 ± 0.1 g in NP, 2.4 ± 0.1 g in NP + PIBF, which decreased to 1.9 ± 0.1 g in RUPP rats (P < 0.05), and improved to 2.1 ± 0.1 g in RUPP + PIBF, P < 0.05, Fig. 2A. Also, placenta weight was significantly reduced in RUPP rats compared with NP rats, P < 0.05. Placenta weight was 0.55 ± 0.01 g in NP, 0.51 ± 0.02 in NP + PIBF, 0.47 ± 0.001 g in RUPP, and 0.48 ± 0.01 g in RUPP ± PIBF, Fig. 2B. Pup-to-placental weight ratio was higher in NP + PIBF rats compared with RUPP rats (4.7 ± 0.1 vs. 4.1 ± 0.1, Fig. 2C). Importantly litter size was elevated in NP compared with RUPP, P < 0.05. In addition to this, litter size was significantly improved after PIBF supplementation in RUPP + PIBF rats compared with RUPP rats, P < 0.05. Litter size, number of live pups, was 14 ± 0.5 in NP and 14 ± 0.4 in NP + PIBF, which significantly decreased to 4.4 ± 0.7 in RUPP rats, P < 0.05. Importantly, PIBF supplementation increased litter size to 9.3 ± 1.1 compared with RUPP rats, P < 0.05, Fig. 2D. Pup reabsorption, calculated as % of total pups at GD19, was 0.7 ± 0.7% in NP and 1.6 ± 1 in NP + PIBF, which significantly increased to 47 ± 8% in RUPP and 43 ± 8 in RUPP + PIBF, P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

PIBF supplementation increases pup weight and litter size in RUPP rats. On GD15, PIBF was given intraperitoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19 pup weight (A), placenta weight (B), pup-to-placental weight ratio (C), and litter size (D) were measured. NP: n = 11 rats, NP + PIBF: n = 8, RUPP: n = 10, RUPP + PIBF: n = 11. All data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. *P < 0.05. GD, gestational day; PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure.

Administration of PIBF Decreased Total and Cytolytic NK Cells in RUPP Rats

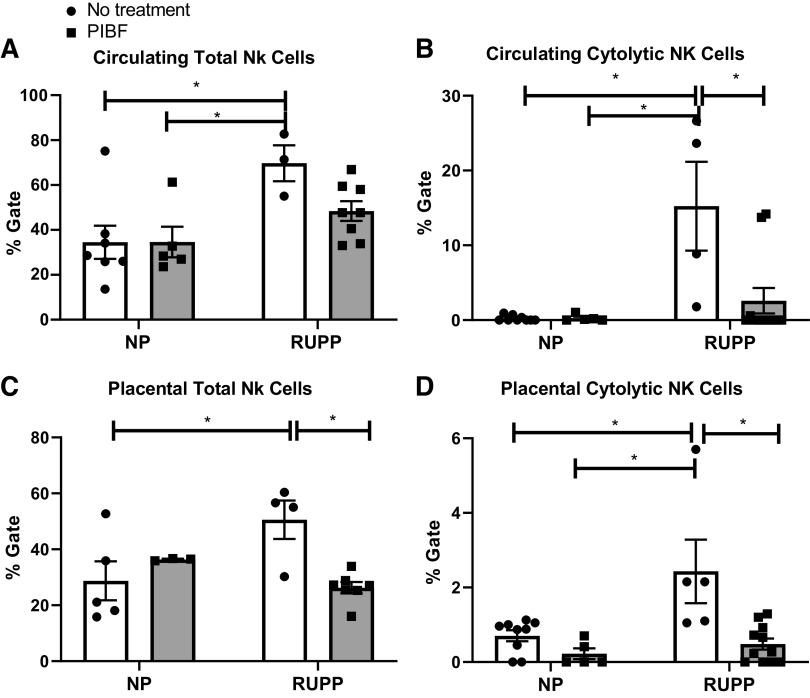

Importantly, we have published no differences in circulating or placental NK cells in Sham-operated rats compared with control pregnant rats. Circulating or placental NK cells are significantly increased in RUPP rats compared with normal pregnant control rats (4). Circulating and placental NK cells were not different between NP and NP + PIBF groups. Circulating total Nk cells were 35 ± 7% gate in NP (n = 7), 35 ± 7% in NP + PIBF (n = 5), and 70 ± 8% in RUPP (n = 3) rats, which significantly decreased to 48 ± 4% gate in RUPP + PIBF (n = 8), P < 0.05, Fig. 3A. Circulating cytolytic NK cells were 0.2 ± 0.1 in both NP and NP + PIBF and 15 ± 6 in RUPP, which decreased to 3 ± 2 in RUPP + PIBF, P < 0.05, Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

PIBF supplementation reduces circulating and placental cytolytic NK cells in RUPP rats. On GD15, PIBF was given intraperitoneally peritoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19, blood and placentas were collected, processed, and analyzed via flow cytometry to obtain levels of circulating total NKs (A) and circulating cytolytic NKs (B): NP: n = 7–9 rats, NP + PIBF: n = 5, RUPP: n = 3–4, RUPP + PIBF: n = 8–10, along with (C) placental total NKs, and (D) placental cytolytic NKs: NP: n = 5–9, NP + PIBF: n = 3–5, RUPP: n = 4–5, RUPP + PIBF: n = 7–10 All data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. *P < 0.05. GD, gestational day; NK, natural killer; PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure.

Total placental NK cells were 29 ± 7% gate in NP (n = 5), 37 ± 0.2 in NP + PIBF (n = 3), 51 ± 7 in RUPP rats (n = 4), and reduced to 26 ± 2 in RUPP + PIBF (n = 7) P < 0.05, Fig. 3C. Placental cytolytic NK cells were 0.7 ± 0.1% gate in NP, 0.2 ± 0.1 in NP + PIBF, and 2.4 ± 1 in RUPP rats, which decreased to 0.4 + 0.1 in RUPP + PIBF, P < 0.05, Fig. 3D.

Administration of PIBF Decreased Inflammation, CD4+ T Cells and Increased TH2 Cells in RUPP Rats

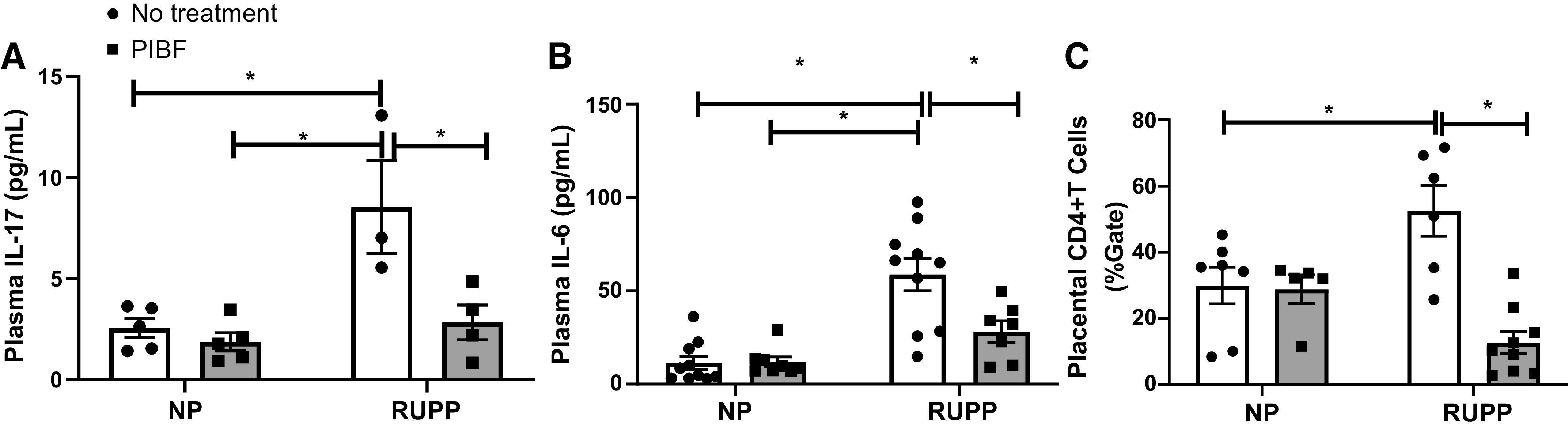

Circulating IL-17 and IL-6 were not significantly different between NP and NP + PIBF groups. IL-17 and IL-6 were 2.5 ± 0.5 pg/mL and 11 ± 4 pg/mL in NP rats (n = 5 and n = 9), which significantly increased to 9 ± 2.3 pg/mL and 59 ± 9 pg/mL in RUPP (n = 3 and n = 9 rats) and decreased to 3 ± 1 pg/mL and 28 ± 6 pg/mL in RUPP + PIBF rats (n = 4 and n = 7 rats), P < 0.05, Fig. 4A and 4B.

Figure 4.

PIBF supplementation decreases inflammation in RUPP rats. On GD15, PIBF was given intraperitoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19, blood and placenta were processed. Plasma was utilized to measure IL-17 (A) and IL-6 (B) via Bioplex. NP: n = 5–10 rats, NP + PIBF: n = 5–10, RUPP: n = 3–8, RUPP+PIBF: n = 4–7. Placenta was used to measure placental CD+4 T cells (C) by flow cytometry (NP: n = 7, NP + PIBF: n = 6, RUPP: n = 5, RUPP + PIBF: n = 9) All data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. *P < 0.05. GD, gestational day; PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure.

We have previously published no difference in Sham and NP placental CD4+ T cells; however, CD4+ T cells are significantly elevated in RUPP rats compared with NP rats (4). Placental CD4+ T cells were increased in RUPP rats compared with NP rats and were reduced after PIBF administration to RUPP rats. There is no difference in CD4+ T cells between NP and NP + PIBF groups. CD4+ T cells were 30 ± 5% gate in NP rats (n = 7), 29 ± 4% in NP + PIBF rats (n = 5), which were elevated to 53 ± 8% in RUPP rats (n = 6, P < 0.05) and were significantly decreased to 13 ± 3% gate in RUPP + PIBF rats (n = 9, P < 0.05), Fig. 4C.

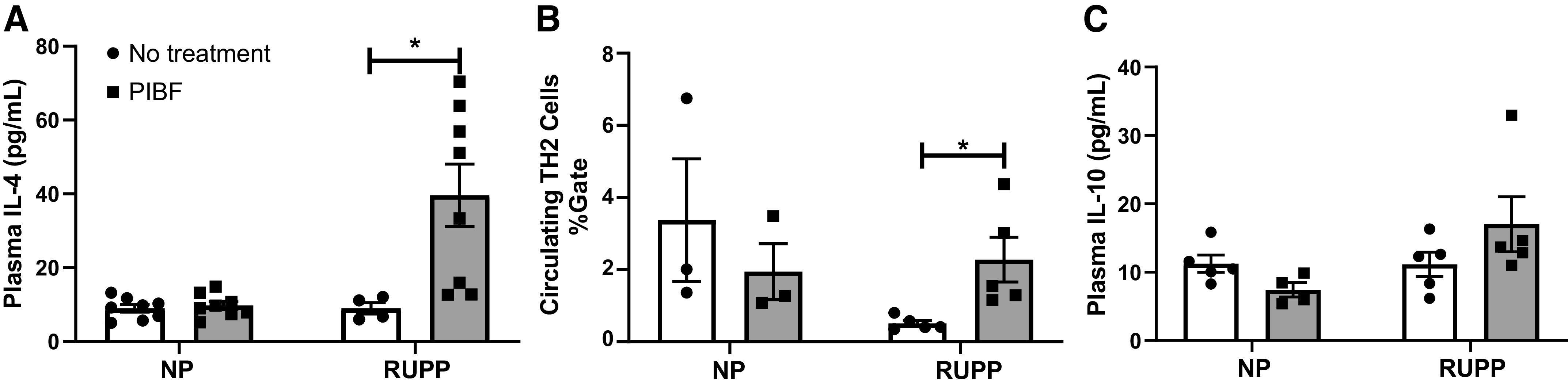

Circulating IL-4 and TH2 cells were not significantly different between NP and NP + PIBF groups; IL-4 was 10 ± 1 pg/mL in NP and in NP + PIBF rats and 9 ± 2 pg/mL in RUPP (n = 4), which significantly elevated to 40 ± 8 pg/mL in RUPP + PIBF (n = 8), P < 0.05, Fig. 5A. TH2 cells were 3 ± 2% gate in NP rats (n = 3) and 2 ± 1% gate in NP + PIBF rats (n = 5). Importantly, PIBF supplementation increased TH2 cells from 0.5 ± 0.1 in RUPP rats to 2 ± 0.6% gate in RUPP+ PIBF (n = 5, P < 0.05, Fig. 5B). In addition to this, circulating IL-10 were no significantly different between all groups, Fig. 5C.

Figure 5.

PIBF supplementation increases circulating TH2 cells and IL-4 levels in RUPP rats. On GD15, PIBF was given intraperitoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19, blood and placenta were processed. Plasma was utilized to measure IL-4 (A) and IL-10 (B) via Bioplex and whole blood was utilized to measure circulating TH2 cells (C) by flow cytometry. NP: n = 3–8 rats, NP + PIBF: n = 3–8, RUPP: n = 4–5, RUPP + PIBF: n = 3–8. All data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. *P < 0.05. GD, gestational day; PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure; TH, T helper.

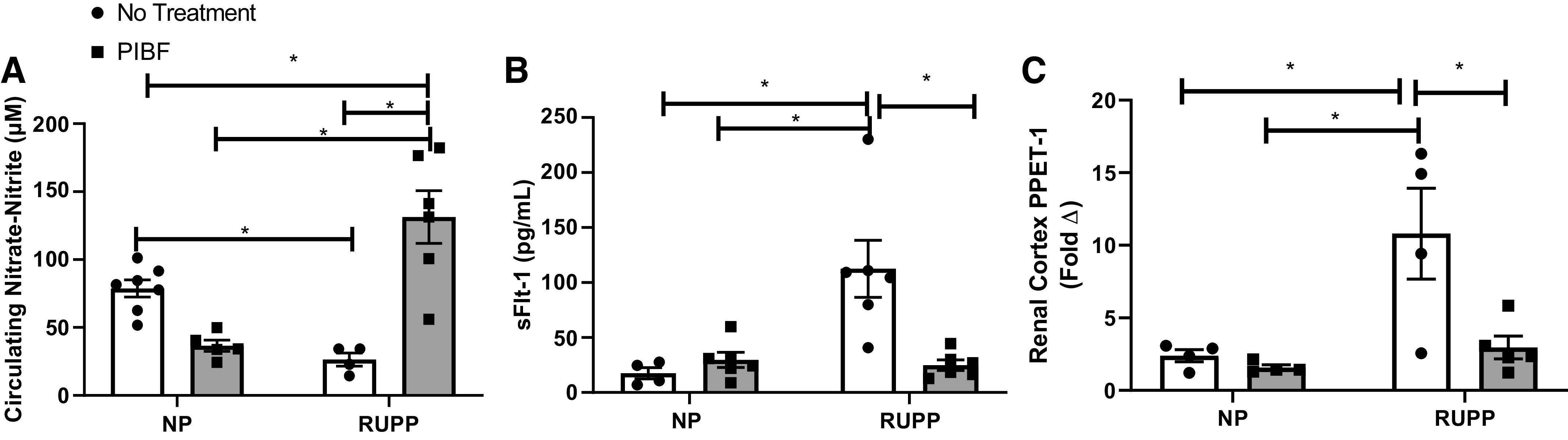

Administration of PIBF Increased NO Levels in RUPP Rats

As in previous studies, circulating NO levels were lowered in RUPP compared with NP rats (18). Plasma nitrate-nitrite levels were 79 ± 6 μM in NP rats (n = 7), 37 ± 4 in NP + PIBF rats (n = 5), and 27 ± 5 in RUPP rats (n = 4), which increased to 131 ± 19 in RUPP + PIBF rats (n = 6), P < 0.05, Fig. 6A.

Figure 6.

PIBF supplementation normalizes circulating vasoactive factors in RUPP rats. On GD15, PIBF was given intraperitoneally into a subset of normal pregnant (NP) and RUPP rats. On GD19, blood and kidney were processed. Plasma was utilized to measure nitrate-nitrite levels (A) by Cayman Colorimetric assay and sFlt-1 levels (B) by ELISA. Kidney cortex was utilized to measure PPET-1 (C) by RT-PCR. NP: n = 4–7 rats, NP + PIBF: n = 4–6, RUPP: n = 4–6; RUPP + PIBF: n = 5–6. Statistical analyses were performed using two‐way ANOVA with multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni as post hoc test. Data are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05. GD, gestational day; PIBF, progesterone-induced blocking factor; PPET-1, preproendothelin-1; RUPP, reduced uterine perfusion pressure.

Administration of PIBF Reduced Renal Cortex PPET-1 Expression and Circulating sFlt-1 in RUPP Rats

Renal cortex PPET-1 was significantly increased by sixfold in RUPP rats (n = 3) versus NP animals (n = 4, P < 0.05). There is no difference between NP and NP + PIBF rats. Administration of PIBF significantly decreased PPET-1 expression in RUPP animals to levels measured in NP rats (RUPP + PIBF = 1.0 ± 0.7, n = 5, P < 0.05 vs. RUPP), Fig. 6B.

As in our previous studies, circulating sFlt-1 levels in response to placental ischemia in RUPP rats were significantly elevated compared with NP rats. Plasma sFlt-1 was 17 ± 5 pg/mL in NP rats (n = 4) and 24 ± 4 pg/mL in NP + PIBF rats (n = 5), which significantly increased to 113 ± 26 pg/mL in RUPP rats (n = 6) and was normalized to 25 ± 5 pg/mL in RUPP + PIBF rats (n = 6), P < 0.05, Fig. 6C.

DISCUSSION

Preeclampsia (PE) affects 5%–7% of all pregnancies in the United States and is associated with reduced placental perfusion and fetal weight, increased inflammation, antiangiogenic factor sFlt-1, vascular endothelial dysfunction, and hypertension (2, 35–37). To date, the best treatment is delivery of the fetal placental unit. Our previous data showed that PE is a state of progesterone deficiency (19), and it is associated with an imbalance among CD4+ T lymphocytes, NK cells, and inflammatory cytokines (3, 5, 38). Our most recently published data indicate that 17-OHPC reduces sFlt-1, uterine artery resistance index (UARI), ET-1, and inflammation while improving NO, pup weight, and blood pressure in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure during pregnancy (18). Importantly, we have recently shown that sham operations mimicking the RUPP without placing the silver surgery clips on the ovarian vessels or the abdominal aorta does not cause hypertension, NK cell, or T cell activation or reduction in pup weight in the pregnant rat (4). In that study, we also found that 17-OHPC lowered T cells and significantly improved placental and circulating TH2 cells in RUPP rats. Moreover 17-OHPC lowered placental cytolytic NK cells and their products, granzyme and perforin (4). However, the mechanism for this was not identified.

Progesterone receptors are expressed on activated lymphocytes. During normal pregnancy progesterone binding to its receptor induces progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF). Therefore, during normal pregnancy the concentration of PIBF continuously increases as progesterone increases. PIBF has been shown to stimulate IL-4/TH2, both of which are reduced during preeclampsia. In agreement with these findings, decreased levels of PIBF have been related to pregnancy complications such as miscarriage and abortion (24, 25).

PIBF is a 757-amino acid residue protein with a 90-kDa predicted molecular mass, which shows no amino acid sequence homology with any other known protein (21). The PIBF receptor is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein, which temporarily associates with the α chain of the IL-4 receptor (39). Therefore, PIBF binding to its receptor stimulates IL-4 signaling, which affects synthesis of other cytokines as well as T cell and NK cell activity (40).

Importantly, interleukin-4 (IL-4) is present at the fetal-maternal interface and is considered an important regulator of fetal-maternal tolerance by preventing the release of proinflammatory cytokines (41). Previous studies have shown that women who have suffered multiple spontaneous abortions and/or PE have low levels of IL-4 (42, 43). Interestingly, our published data showed that IL-4 supplementation decreases ET-1 and improves NO and blood pressure in RUPP rats (29). In this study, the resulting increase in IL-4 is the likely mechanism were by ET-1 and sFlt-1 decreased and NO improved, leading to improved blood pressure, thus underscoring the importance of progesterone, PIBF, and IL-4 to maintain normal blood pressures during pregnancy.

We found that PIBF is one mechanism whereby progesterone supplementation could improve inflammatory pathways activated in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure, and thus improve pregnancy outcomes. Our findings in this current study demonstrate that PIBF supplementation decreased NK cell activation possibly through drastically improving IL-4 and thus stimulated TH2 cells in RUPP rats. Moreover, PIBF significantly lowered CD4+ T cells and proinflammatory cytokines, which we have shown to modulate vasoactive pathways ET-1, nitric oxide, and sFlt-1, all of which contribute to improved hypertension in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure. Therefore, PIBF can decrease vasoactive pathways and hypertension by decreasing the cytokines that activate them, such as IL-17, IL-6, and TNF-α.

The exact mechanism of either progesterone or PIBF in pregnancy disorders is still not fully understood. The effect of PIBF on NK activity has been associated with altered cytokine production both in vitro and in vivo. Neutralization of endogenous PIBF in lymphocytes during pregnancy by a PIBF-specific antibody increased NK cell activity and thus pregnancy loss induced by anti-PIBF administration, which could be inhibited with administration of anti-NK antibodies (44, 45). Moreover, our data suggest that PIBF contributes to the success of pregnancy and which may be attributed to NK cell inhibitory actions.

Importantly, PIBF normalized many signs of PE such as sFlt-1, which is known to play a role in hypertension and reducing fetal weight in PE (46, 47). We have shown sFlt-1 to be secreted by PE or RUPP CD4+ T cells. Thus, the decrease in these cells is the likely mechanism for decrease sFlt-1(5, 37). PIBF also significantly improved pup weight and litter size in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure during pregnancy. Previous studies in mice have shown that a reduction in the number of viable fetuses after neutralization of endogenous PIBF, and it was associated with an increase of NK cells activity (45). Improving fetal weight and viability is one of the most important challenges in treating PE. Many substances may be able to improve the maternal symptoms, but we must also find ways to benefit offspring from PE pregnancies. Collectively our studies indicate that progesterone activating pathways either by 17 OHPC or PIBF have proven to be important therapeutics that could have benefit to both moms and babies.

Perspectives and Significance

Currently there is no cure for preeclampsia and the discovery of mechanisms that are relevant to the pathophysiology of this pregnancy disorder may offer new therapeutic targets. Our findings suggest that PIBF administration into RUPP rats decreases inflammation, cytolytic NK cells, angiogenic, and vasoconstrictor factors that are elevated in preeclampsia resulting in decreased blood pressure and improved pup weight. Moreover, PIBF, an important product of progesterone, could be a potential therapeutic option to enhance the current management of PE.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1HD067541-09, P20GM121334, and R00HL130456, and American Heart Association Grants 19CDA34670055 and 18CDA34110264.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.M.A. conceived and designed research; L.M.A, J.N.C., A.C.W., K.C., M.W.C., T.I., and D.C.C. performed experiments; J.N.C., D.C.C., and L.M.A. analyzed data; J.N.C., A.C.W., and L.M.A. interpreted results of experiments; J.N.C. prepared figures; J.N.C. drafted manuscript; B.L. and L.M.A. edited and revised manuscript; J.N.C., A.C.W., K.C., M.W.C., T.I., D.C.C., B.L., and L.M.A. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phipps E, Prasanna D, Brima W, Jim B. Preeclampsia: updates in pathogenesis, definitions, and guidelines. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1102–1113, 2016. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12081115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornelius DC, Cottrell J, Amaral LM, LaMarca B. Inflammatory mediators: a causal link to hypertension during preeclampsia. Br J Pharmacol 176: 1914–1921, 2019. doi: 10.1111/bph.14466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elfarra J, Amaral LM, McCalmon M, Scott JD, Cunningham MW Jr, Gnam A, Ibrahim T, LaMarca B, Cornelius DC. Natural killer cells mediate pathophysiology in response to reduced uterine perfusion pressure. Clin Sci 131: 2753–2762, 2017. doi: 10.1042/CS20171118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elfarra JT, Cottrell JN, Cornelius DC, Cunningham MW Jr, Faulkner JL, Ibrahim T, Lamarca B, Amaral LM. 17-Hydroxyprogesterone caproate improves T cells and NK cells in response to placental ischemia; new mechanisms of action for an old drug. Pregnancy Hypertens 19: 226–232, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace K, Richards S, Dhillon P, Weimer A, Edholm ES, Bengten E, Wilson M, Martin JN Jr, LaMarca B. CD4+ T-helper cells stimulated in response to placental ischemia mediate hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension 57: 949–955, 2011. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raghupathy R. Th1-type immunity is incompatible with successful pregnancy. Immunol Today 18: 478–482, 1997. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito S, Nakashima A, Shima T, Ito M. Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 63: 601–610, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito S, Sakai M, Sasaki Y, Tanebe K, Tsuda H, Michimata T. Quantitative analysis of peripheral blood Th0, Th1, Th2 and the Th1:Th2 cell ratio during normal human pregnancy and preeclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol 117: 550–555, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veenstra van Nieuwenhoven AL, Heineman MJ, Faas MM. The immunology of successful pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update 9: 347–357, 2003. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukui A, Funamizu A, Yokota M, Yamada K, Nakamua R, Fukuhara R, Kimura H, Mizunuma H. Uterine and circulating natural killer cells and their roles in women with recurrent pregnancy loss, implantation failure and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 90: 105–110, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukui A, Yokota M, Funamizu A, Nakamua R, Fukuhara R, Yamada K, Kimura H, Fukuyama A, Kamoi M, Tanaka K, Mizunuma H. Changes of NK cells in preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol 67: 278–286, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd JM, Jones L, Flenady V, Cincotta R, Crowther CA. Prenatal administration of progesterone for preventing preterm birth in women considered to be at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD004947, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meis PJ. The role of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate in the prevention of preterm birth. Womens Health (Lond) 2: 819–824, 2006. doi: 10.2217/17455057.2.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlob P, Stahl B, Klinger G. 17alpha Hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth. Reprod Toxicol 33: 15–19, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sfakianaki AK, Er N. Mechanisms of progesterone action in inhibiting prematurity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 19: 763–772, 2006. doi: 10.1080/14767050600949829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, Chauhan SP, Hughes BL, Louis JM, Manuck TA, Miller HS, Das AF, Saade GR, Nielsen P, Baker J, Yuzko OM, Reznichenko GI, Reznichenko NY, Pekarev O, Tatarova N, Gudeman J, Birch R, Jozwiakowski MJ, Duncan M, Williams L, Krop J. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol 37: 127–136, 2020. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaral LM, Cornelius DC, Harmon A, Moseley J, Martin JN Jr, LaMarca B. 17-hydroxyprogesterone caproate significantly improves clinical characteristics of preeclampsia in the reduced uterine perfusion pressure rat model. Hypertension 65: 225–231, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amaral LM, Faulkner JL, Elfarra J, Cornelius DC, Cunningham MW, Ibrahim T, Vaka VR, McKenzie J, LaMarca B. Continued investigation into 17-OHPC: results from the preclinical RUPP rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension 70: 1250–1255, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiprono LV, Wallace K, Moseley J, Martin J Jr, Lamarca B. Progesterone blunts vascular endothelial cell secretion of endothelin-1 in response to placental ischemia. Am Jo Obstet Gynecol 209: 44.e1–44.e6, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szekeres-Bartho J, Halasz M, Palkovics T. Progesterone in pregnancy; receptor-ligand interaction and signaling pathways. J Reprod Immunol 83: 60–64, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.06.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polgar B, Kispal G, Lachmann M, Paar C, Nagy E, Csere P, Miko E, Szereday L, Varga P, Szekeres-Bartho J, Paar G. Molecular cloning and immunologic characterization of a novel cDNA coding for progesterone-induced blocking factor. J Immunol 171: 5956–5963, 2003. [Erratum in J Immunol 172: 2703, 2004]. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szekeres-Bartho J, Autran B, Debre P, Andreu G, Denver L, Chaouat G. Immunoregulatory effects of a suppressor factor from healthy pregnant women's lymphocytes after progesterone induction. Cell Immunol 122: 281–294, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szekeres-Bartho J, Kilaŕ F, Falkay G, Csernus V, Török A, Pacsa AS. The mechanism of the inhibitory effect of progesterone on lymphocyte cytotoxicity: I. Progesterone-treated lymphocytes release a substance inhibiting cytotoxicity and prostaglandin synthesis. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol 9: 15–18, 1985. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1985.tb00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudic I, Szekeres-Bartho J, Stray-Pedersen B, Fatusic Z, Polgar B, Ecim-Zlojutro V. Lower urinary and serum progesterone-induced blocking factor in women with preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol 117: 66–69, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polgar B, Nagy E, Miko E, Varga P, Szekeres BJ. Urinary progesterone-induced blocking factor concentration is related to pregnancy outcome. Biol Reprod 71: 1699–1705, 2004. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghupathy R, Al Mutawa E, Makhseed M, Azizieh F, Szekeres-Bartho J. Modulation of cytokine production by dydrogesterone in lymphocytes from women with recurrent miscarriage. BJOG 112: 1096–1101, 2005. [Erratum in BJOG 112: 1585, 2005]. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogdan A, Polgar B, Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone induced blocking factor isoforms in normal and failed murine pregnancies. Am J Reprod Immunol 71: 131–136, 2014. doi: 10.1111/aji.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giezeman-Smits KM, Jonges LE, Chambers WH, Brisette-Storkus CS, Van Vlierberghe RL, Van Eendenburg JD, Eggermont AM, Fleuren GJ, Kuppen PJ. Novel monoclonal antibodies against membrane structures that are preferentially expressed on IL-2-activated rat NK cells. J Leukoc Biol 63: 209–215, 1998. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cottrell JN, Amaral LM, Harmon A, Cornelius DC, Cunningham MW Jr, Vaka VR, Ibrahim T, Herse F, Wallukat G, Dechend R, LaMarca BD. Interleukin-4 supplementation improves the pathophysiology of hypertension in response to placental ischemia in RUPP rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 316: R165–R171, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00167.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaMarca BB, Bennett WA, Alexander BT, Cockrell K, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Hypertension 46: 1022–1025, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaMarca BD, Gilbert J, Granger JP. Recent progress toward the understanding of the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Hypertension 51: 982–988, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaMarca B, Wallace K, Herse F, Wallukat G, Martin JN Jr, Weimer A, Dechend R. Hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: role of B lymphocytes. Hypertension 57: 865–871, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension 46: 82–86, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000169152.59854.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaMarca BD, Alexander BT, Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy: a central role for endothelin? Gend Med 5: S133–S138, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American College of Obstetricians, Gynecologists, and Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 122: 1122–1131, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H541–H550, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmon AC, Cornelius DC, Amaral LM, Faulkner JL, Cunningham MW Jr, Wallace K, LaMarca B. The role of inflammation in the pathology of preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 130: 409–419, 2016. doi: 10.1042/CS20150702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaMarca BD, Ryan MJ, Gilbert JS, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Inflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep 9: 480–485, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s11906-007-0088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozma N, Halasz M, Polgar B, Poehlmann TG, Markert UR, Palkovics T, Keszei M, Par G, Kiss K, Szeberenyi J, Grama L, Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor activates STAT6 via binding to a novel IL-4 receptor. J Immunol 176: 819–826, 2006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szekeres-Bartho J, Polgar B. PIBF: the double edged sword. Pregnancy and tumor. Am J Reprod Immunol 64: 77–86, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Bounds KR, Mitchell BM. Regulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 during pregnancy. Front Immunol 5: 253, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hambartsoumian E. Endometrial leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) as a possible cause of unexplained infertility and multiple failures of implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol 39: 137–143, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piccinni MP, Romagnani S. Regulation of fetal allograft survival by a hormone-controlled Th1- and Th2-type cytokines. Immunol Res 15: 141–150, 1996. doi: 10.1007/BF02918503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szekeres-Bartho J, Faust Z, Varga P, Szereday L, Kelemen K. The immunological pregnancy protective effect of progesterone is manifested via controlling cytokine production. Am J Reprod Immunol 35: 348–351, 1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szekeres-Bartho J, Par G, Dombay G, Smart YC, Volgyi Z. The antiabortive effect of progesterone-induced blocking factor in mice is manifested by modulating NK activity. Cell Immunol 177: 194–199, 1997. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baltajian K, Hecht JL, Wenger JB, Salahuddin S, Verlohren S, Perschel FH, Zsengeller ZK, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA, Rana S. Placental lesions of vascular insufficiency are associated with anti-angiogenic state in women with preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy 33: 427–439, 2014. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2014.926914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 111: 649–658, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]