Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects one in three adults and remains the leading cause of death in America. Advancing age is a major risk factor for CVD. Recent plateaus in CVD-related mortality rates in high-income countries after decades of decline highlight a critical need to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies to mitigate and manage the risk of CVD development and progression. Vascular dysfunction, characterized by endothelial dysfunction and large elastic artery stiffening, is independently associated with an increased CVD risk and incidence and is therefore an attractive target for CVD prevention and management. Vascular mitochondria have emerged as an important player in maintaining vascular homeostasis. As such, age- and disease-related impairments in mitochondrial function contribute to vascular dysfunction and consequent increases in CVD risk. This review outlines the role of mitochondria in vascular function and discusses the ramifications of mitochondrial dysfunction on vascular health in the setting of age and disease. The adverse vascular consequences of increased mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species, impaired mitochondrial quality control, and defective mitochondrial calcium cycling are emphasized, in particular. Current evidence for both lifestyle and pharmaceutical mitochondrial-targeted strategies to improve vascular function is also presented.

Keywords: endothelium, mitochondria, vascular, vascular stiffness

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) affects one in three adults and is the leading cause of death in the United States (1). The risk for CVD increases with age, with a CVD incidence ∼80% in those between 60–79 yr of age and up to ∼90% in those above the age of 80 yr (1). The CVD risk associated with aging is further augmented by the continuous rise in noncommunicable comorbidities such as obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and sleep apnea (1). Such comorbidities often share an accelerated pathophysiology of aging that contribute to a heightened CVD burden. As the population over 60 yr continues to grow (2), combined with projected increases in noncommunicable disease (3, 4), a continued increase in CVD is expected over the next two decades (1).

Despite a significant decline in CVD-related mortality between 1990 and 2015, CVD mortality rates have recently reached a nadir, particularly in high-income countries such as the United States of America (5). The lack of recent progress in reducing CVD mortality has raised concern about the sustained efficacy and inadequate advancements in therapeutic strategies to prevent, manage, and treat CVD. Therefore, there is a critical need to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies to mitigate the risk of CVD.

Aberrant vascular function is a well-established contributor to CVD. Impaired vascular function includes stiffening of the large elastic arteries and endothelial dysfunction characterized by a proatherosclerotic reduction in nitric oxide (NO) production and bioavailability, both of which hamper tissue blood flow to meet metabolic demand, increase end organ damage, and augment cardiac afterload (6). Both arterial stiffness and vascular endothelial dysfunction have been shown to predict future CVD events independent of other risk factors (7, 8). Targeting arterial stiffening and endothelial dysfunction is therefore an attractive strategy to prevent and manage CVD. In this respect, successful interventions to improve and maintain vascular function rely on identifying the contributing pathophysiological targets (6). Over the last two decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in the important role that the mitochondria play in maintaining vascular homeostasis (9). Damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria are consistently reported as a cause and consequence of aging, sedentarism, and chronic disease (10) and are therefore an attractive therapeutic mechanism of aging- and disease-related vascular dysfunction and subsequent CVD risk (11, 12).

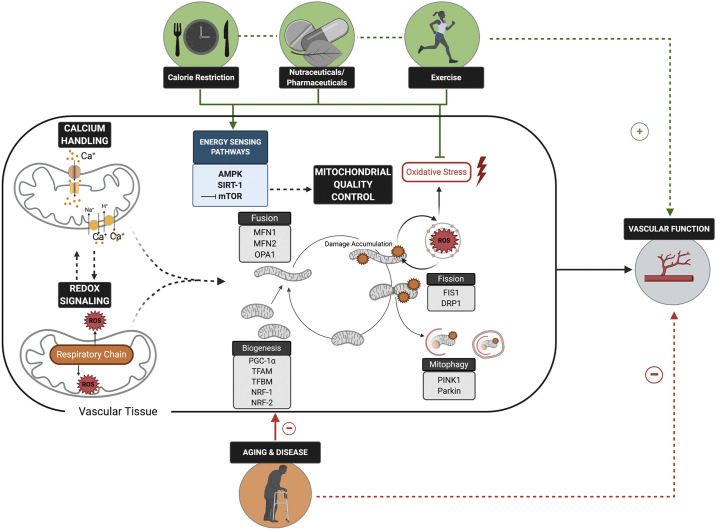

The purpose of this review is to discuss the evidence supporting the role of the mitochondria in vascular function and the mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction-associated vascular dysfunction (Fig. 1). Mitochondrial-targeted lifestyle and nutraceutical and pharmaceutical strategies aimed at improving vascular function are also discussed (Figs. 1 and 2), highlighting the current gaps in knowledge and potential prospective interventions.

Figure 1.

Optimal mitochondrial redox balance, calcium handling, and quality control are physiologically integrated mitochondrial functions that all play key roles in maintaining vascular function. Age- and disease-related impairments in these aspects of mitochondrial health and functions have adverse implications for vascular function and, consequently, cardiovascular disease risk. Lifestyle and pharmaceutical strategies that reduce mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress and improve mitochondrial quality control via modulation of energy sensing pathways hold promise for improving vascular function. PGC-1α, proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; TFBM, mitochondrial transcription factor B; DRP1, dynamin-related protein 1; FIS1, fission-1; MFN1 and MFN2, transmembrane GTPAses mitofusion-1 and 2; OPA1, optic atrophy protein 1; PINK1, phosphate and tensin homolog-induced kinase protein 1; NRF1- and NRF-2, nuclear respiratory factor 1 and 2; SIRT1, Sirtuin-1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin. Figure was made with biorender.com and published with permission.

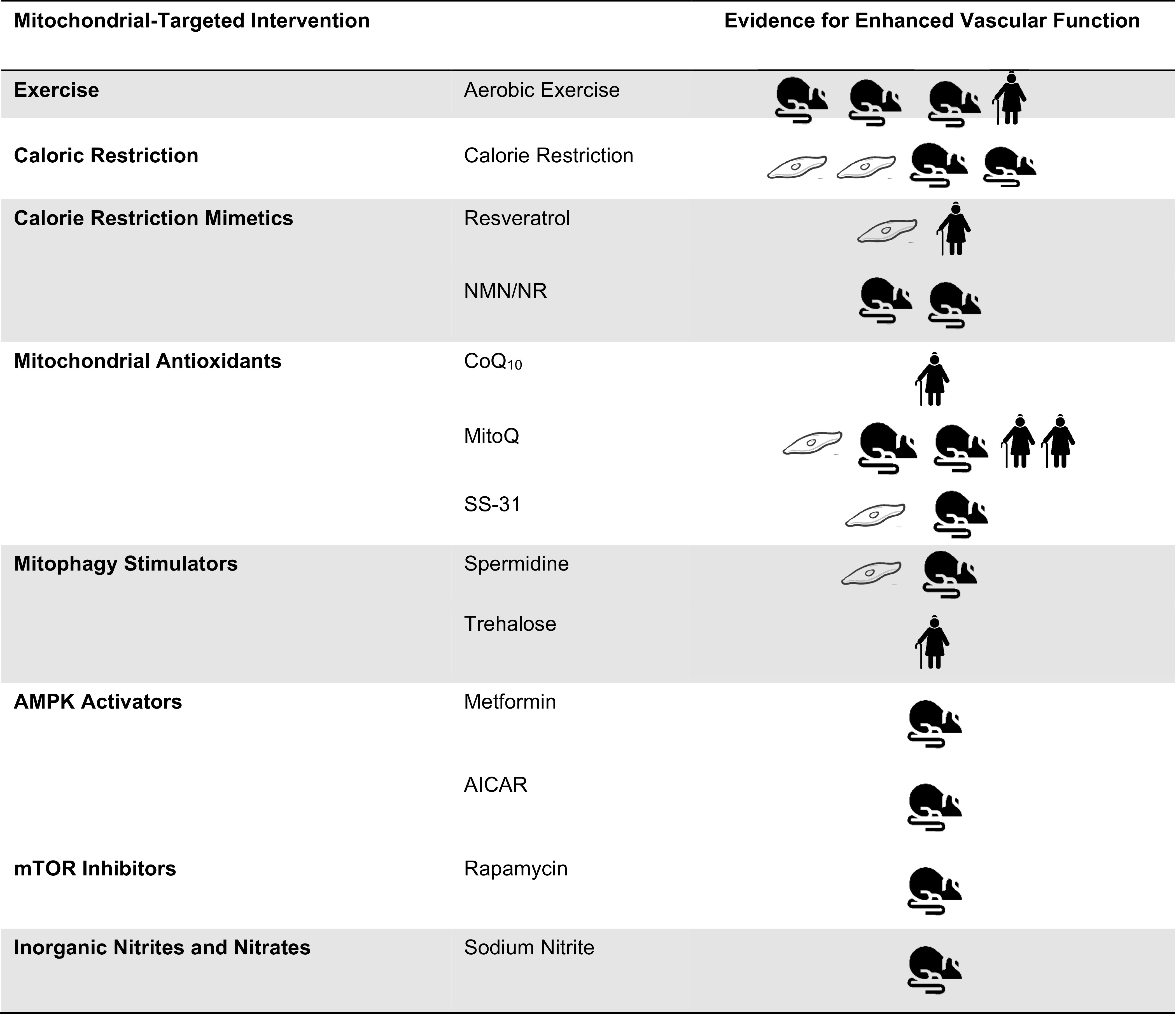

Figure 2.

Efficacy evidence pertaining to improved vascular function mediated by mitochondrial function in aging and disease models and populations. AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate- activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NR, nicotinamide riboside.

VASCULAR MITOCHONDRIA

Traditionally mitochondria are viewed as the primary ATP-producing organelle in cells to meet energy demands. In cells that rely heavily on oxidative phosphorylation for their energy needs, such as skeletal muscle fibers and cardiomyocytes, mitochondria account for 15% and 35% of the cell volume respectively (13, 14). In comparison, vascular endothelial cells rely predominantly on anaerobic glycolysis for ATP turnover and mitochondria make up 2–5% of the cytoplasmic volume of endothelial cells in most vascular beds (15, 16). As a result, the role of mitochondria in these cells has previously been overlooked. However, it is now recognized that endothelial mitochondria play a critical role in cell signaling, predominately by virtue of their reactive oxygen species (ROS) generating capability and their role in calcium homeostasis (17). The location of the mitochondria within the endothelial cell differs depending on the specific signaling required at their respective tissue bed. For example, in pulmonary artery endothelial cells where oxygen (O2) sensing is pertinent, perinuclear clustering of the mitochondria allows for hypoxia-induced transcriptional regulation (18). Alternatively, in coronary arterioles, endothelial mitochondria are anchored to the cytoskeleton to initiate dilatory signaling in response to the mechanical stimulus of shear stress (19).

In vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), mitochondria content is also reduced in comparison with skeletal muscle and cardiomyocyte content, although not to the same extent as in vascular endothelial cells (20). Energy production in these cells is required for the control of myogenic tone, cellular transport, and secretory functions that are involved in maintaining the structural integrity of the vascular wall (21, 22). In comparison with skeletal muscle fibers and cardiomyocytes, VSMCs have significantly increased mitochondrial proton leak during aerobic respiration (20). As increased proton leak is typically associated with increased ROS production (20), this is potentially indicative of additional ROS-mediated cell signaling roles of the mitochondria in VSMCs. Mitochondria within VSMCs are immobile and located close to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (23), which is likely to allow for mitochondrial-reticulum coupling that is required for calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis (22).

Cellular mitochondrial content is tightly regulated, and the distribution and cytosolic density are integral determinants of cell signaling in vascular cell types (11, 12). As such, the quality, content and morphology of mitochondria are closely controlled and coordinated through mitochondrial quality control processes, including mitochondrial biogenesis, the dynamics of fission and fusion, and mitophagy (the mitochondrial-specific form of autophagy). An imbalance in these processes due to aging- and/or disease-related damage initiates mitochondria-mediated cell senescence and apoptosis (11).

The following sections will detail the role of the mitochondria in ROS production and cell signaling. We will discuss age- and disease-related impairments in these physiological processes that lead to vascular dysfunction and culminate in increased CVD risk. In addition, the vascular consequences of the disruption in mitochondrial quality control processes and mitochondria-mediated calcium homeostasis will be discussed.

MITOCHONDRIAL-DERIVED REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES AND VASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Mitochondria are a major source of vascular oxidative stress (24–27). A number of studies have demonstrated a critical role for mitochondrial ROS in vascular dysfunction by demonstrating that mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants improve vascular function in preclinical (25, 28) and human trials (27, 29–32). In this review we primarily focus on the role of mitochondrial ROS on the peripheral vasculature, specifically endothelial dysfunction and increased arterial stiffness. However, mitochondrial dysfunction also contributes to the pathogenesis of CVD by influencing cardiac function and autonomic regulation as reviewed elsewhere (33, 34).

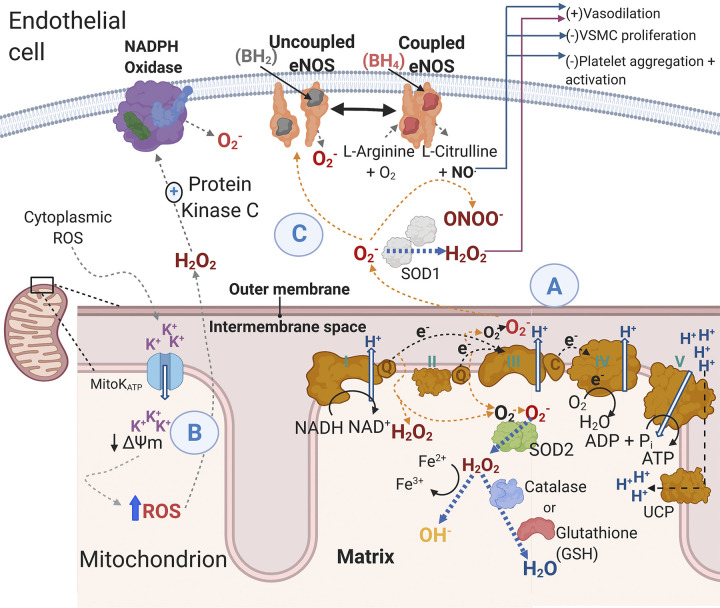

Mitochondrial ROS production is one of the primary cell signaling roles of mitochondria in endothelial cells. Endothelial cells produce an array of ROS, including superoxide (), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), peroxynitrite (ONOO–), hydroxyl radicals (OH•), and other oxidative and nitrosative radicals (35, 36) (Fig. 3). However, oxidative stress that results from increased oxidant production, reduced antioxidant capacity, or both, leads to endothelial dysfunction by reducing NO bioavailability (11, 17). Other major sources of ROS and oxidative stress in the vasculature include NADPH oxidase (NOX) and xanthine oxidase (37, 38). Moreover, there may be cross talk between mitochondrial ROS and other sources of ROS such as NOX (39) (Fig. 3). While mitochondrial ROS play an important physiological role in maintaining vascular homeostasis, excess ROS reduces NO bioavailability through mechanisms including NO scavenging that occurs when reacts with NO to form ONOO− (40, 41), which broadly contributes to cellular nitrosative and oxidative stress (42) and uncouples endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (43) (Fig. 3). Moreover, separation of eNOS monomers in the uncoupled state given that prior studies have demonstrated that higher vascular aging and uncoupled eNOS is associated with a higher ratio of eNOS monomer-to-eNOS dimers (44). In addition, can oxidize the essential eNOS cofactor BH4 to BH2, which subsequently leads to eNOS uncoupling whereby eNOS produces more and less NO (45) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species ROS generation and consequences in the endothelial cell. A: during normal operation of the electron transport chain electrons are passed from complex I and complex II to ubiquinol, which transfers electrons to complex III. From complex III, electrons are transferred via cytochrome c to complex IV. Hydrogen ions are pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane creating a proton motive force that complex IV uses to generate ATP. Uncoupling protons facilitate proton leak and dissipation of the proton motive force. However, when electrons are being passed along the electron transport chain, there is electron leak whereby unpaired electrons react with diatomic oxygen to form . The primary oxidant produced by complex I in endothelial cells is H2O2 while complex III can generate both H2O2 and . The generated from metabolism can be converted to H2O2 in the mitochondria by SOD2, and H2O2 can be further reduced to water by the enzymes’ catalase and the reduced form of glutathione. The H2O2 can also form hydroxyl radicals. Superoxide released into the cytoplasm can be converted into H2O2 by SOD1. B: activation or inhibition of MitoK+ATP influences mitochondrial membrane potential. There are several studies documenting that depolarization and hyperpolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential are associated with an increase in mitochondrial-derived ROS. Importantly, cytoplasmic ROS may elicit mitochondrial depolarization at least in part through opening MitoK+ATP channels, which results in mitochondrial ROS release by respiratory complexes and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (not shown here) (24). C: mitochondrial ROS can promote additional ROS generation in the cytoplasm through multiple mechanisms including direct scavenging of NO by superoxide () to form peroxynitrate (ONOO−) or by excess mitochondrial ROS “uncoupling” eNOS, which results in eNOS producing in contrast to NO. Additionally, mitochondrial ROS stimulate protein kinase C, which activates the ROS-generating enzyme complex NADPH oxidase to produce . The reduction in NO bioavailability has several important actions in maintaining vascular homeostasis (e.g., vasodilation and proliferation). Black arrows indicate “normal” physiology, whereas orange arrows indicate a shift toward mitochondrial ROS production, and blue arrows indicate antioxidant activity. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MitoK+ATP, mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels; ONOO−, peroxynitrate; NO, nitric oxide; , superoxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; UCP, uncoupling protein. Figure was made with biorender.com and published with permission.

Mitochondrial ROS also promote excess inflammation, which also contributes to endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffening (46–48). Increased arterial stiffness occurs through primary stiffening of the arterial wall (i.e., stimulating collagen deposition and elastin degradation) and via increasing VSMC tone secondary to a loss of NO (49, 50) and ultimately contributes to the pathophysiology of CVD (25, 51). While there is limited data delineating the contribution of impaired VSMC function to arterial stiffness, there is some preclinical evidence demonstrating that intrinsic increases in VSMC stiffness contribute to age-related increases in arterial stiffness (52). The role of mitochondrial dysfunction and excess ROS production in the VSMC as a mediator of this relationship is unknown. The mechanisms through which excess oxidative stress and inflammation adversely affect arterial stiffness include altering gene expression (53), structural remodeling, and contributing to invasion of the vascular wall by proinflammatory mediators (54). Mitochondrial ROS also induce mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variants that are more prone to the development of age-related and resistant hypertension (55–57). Such alterations in mtDNA negatively impact mitochondrial DNA copy number and expression of respiratory subunits, with consequential losses in vascular compliance and the development of hypertension (55, 56, 58). These alterations in mtDNA may also impact the expression of important mitochondrial-derived peptides (such as humanin) that have a protective effect on vascular endothelial function (59, 60). In the following sections (and as summarized in Fig. 3), we will discuss specific sources of mitochondrial ROS, cross talk with other sources of ROS and important cellular antioxidant defenses against excess ROS.

Sources of Mitochondrial ROS

Electron leak.

Mitochondria-derived ROS generally result from unpaired electrons from the electron transport chain, partially reducing molecular O2 to form a radical (61, 62). The primary sites of ROS production in the mitochondria are complexes I and III (63, 64). Experiments in isolated mitochondria demonstrate complex I-derived ROS are exclusively released into the mitochondrial matrix and that no detectable levels escape from intact mitochondria (64). It has been posited that complex I-derived ROS are confined to the matrix because the site of electron leak is from the iron-sulfur clusters of the hydrophilic arm of complex I (i.e., matrix protruding) (64). In contrast, complex III releases ROS on both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Specific to the vasculature, in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) mitochondrial ROS generated from complex I are released to the mitochondrial matrix, with the majority being converted to H2O2 (63); however, in cardiomyocytes complex I has been demonstrated to produce primarily (65). In contrast, in BAECs complex III primarily generates , which effluxes out of the outer mitochondrial membrane. In subsequent experiments in succinate-fueled mitochondria (thus bypassing complex I), addition of the complex I inhibitor rotenone decreased H2O2 production but had no effect on O2– production. The complex III inhibitor antimycin inhibited succinate driven but did not decrease H2O2 production, suggesting reverse electron transfer. Reverse electron transport is produced when electrons from ubiquinol are transferred back to respiratory complex I, thus reducing NAD+ to NADH, and is highly contingent on substrate conditions (66). Prior studies in mitochondria isolated from cardiomyocytes demonstrate that succinate induces reverse electron flow to complex I, that this process generates , and that this phenomenon can be attenuated with complex I blockade via rotenone (67); however, additional data are needed in endothelial cells. Taken together, endothelial cell-specific findings indicate that mitochondrial ROS result largely from reverse transport to complex I and through the Q-cycle of complex III. These findings are also broadly in agreement that the Q cycle is a source of ROS in the mitochondria (68, 69). Mitochondrial generated from complex III into the intermembrane space can traverse through voltage-dependent anion channels into the cytosol; however, most of the is rapidly converted into H2O2 via cytosolic superoxide dismutase (SOD) aka SOD1 (68, 70) (Fig. 3).

p66Shc.

The p66Shc adaptor protein is a Src homology 2 (SH2) protein and is a key regulator of mitochondrial function, endothelial ROS signaling, and aging (reviewed a length in Refs. 71, 72). p66Shc increases ROS production from NADPH oxidase and the mitochondria. Specifically, p66Shc phosphorylation leads to recognition by the prolyl isomerase PIN1 and p66Shc is subsequently dephosphorylated before its translocation to the mitochondria (71). p66Shc utilizes reducing equivalents of the mitochondrial electron transfer chain through the oxidation of cytochrome c to produce H2O2 (73). There is abundant preclinical evidence of a role in p66Shc in multiple contexts of vascular dysfunction. For example, in a cage-controlled environment p66Shc−/− mice have an increased life span (74) and aged p66Shc−/− mice are protected against aging-induced increases in ROS and reduced NO bioavailability (75). In a subsequent rat study, p66Shc overexpression inhibited eNOS-dependent NO production and p66Shc knockdown with siRNA resulted in increased phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 in ex vivo aortic rings (76). These findings were later extended to the cerebral circulation whereby basilar arteries from p66Shc−/− mice were protected against age-related oxidative stress (77). Additionally, in an angiotensin II-induced hypertension model, downregulation of p66shc expression mitigates endothelial dysfunction and attenuates the reduction of NO bioavailability and increase in blood pressure (78). Genetic deletion of p66Shc also preserves renal microvascular function and attenuates increases in salt-sensitive blood pressure (79). These findings demonstrate a critical role for p66Shc in regulating vascular function via oxidative stress and NO bioavailability, although there is a need for future studies to determine whether there is a direct role of p66Shc in human vascular oxidative stress.

Mitochondrial cross talk: ROS-induced ROS.

The mitochondria are both a source of ROS but also a target of excess ROS. The concept of mitochondria and ROS-induced ROS production has been reviewed at length previously (80). Excessive ROS, particularly ONOO− can elicit oxidative damage to the mitochondrial respiratory complexes (e.g., iron-sulfur centers and thiol residue side chains) (24, 80). These oxidative reactions by extra- or intramitochondrial ROS can serve to amplify mitochondrial ROS production during respiration. Moreover, excess ONOO− can also lead to inactivation of the endogenous antioxidant mitochondrial SOD (i.e., SOD2) through nitration, particularly in the context of vascular aging (81).

Multiple studies have demonstrated substantial cross talk between NOX and mitochondria in the vasculature (24, 25, 39, 80) (Fig. 3). Initial studies in this area demonstrated that angiotensin II elicits excessive mitochondrial ROS leading to endothelial dysfunction via cross talk with NOX2 using intact BAECs and isolated mitochondria (24). Angiotensin II increased H2O2 release, which was blocked by the nonspecific NOX inhibitor apocynin, and knockdown of p22phox subunit of NOX with small interfering RNA also inhibited angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial ROS production, indicating a specific role of NOX in stimulating mitochondrial ROS. Moreover, inhibition of protein kinase C, which acts an upstream activator of NOX by phosphorylating critical subunits, also inhibited mitochondrial ROS production (24). Interestingly, angiotensin II or the phorbol ester PMA (protein kinase C activator) did not influence ROS production in isolated mitochondria, thus demonstrating a critical role of cytosolic and/or membrane components of the protein kinase C/NOX pathway in stimulating mitochondrial ROS. Subsequent investigations have determined the specific molecular mechanisms responsible for the stimulation of mitochondrial using cultured human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and an angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive mouse model (25). Interestingly, NOX2 knockdown with siRNA (but not other NOX isoforms) inhibited both angiotensin II-induced mitochondrial and cytoplasmic in HAECs. Moreover, in gp91phox subunit knockout mice, angiotensin II-induced mitochondrial and cytoplasmic were reduced and hypertension was attenuated (25). The mitochondrial-specific antioxidant mito-TEMPO also attenuated angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, and efficacy was further improved by the addition of malate (to inhibit mitochondrial reverse electron transfer), further suggesting a critical role of NOX2 in both mitochondrial production and reverse electron transfer to increase H2O2 release (25).

MitoK+ATP channels, mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial permeability transition pore, and cytoplasmic ROS.

When considering the specific mechanisms by which mitochondria in the vasculature release ROS downstream of NOX and uncouple eNOS, it is important to mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channel (MitoK+ATP) activation and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). MitoK+ATP activity is normally regulated by falling ATP and rising ADP levels, thus linking cellular metabolism with membrane excitability (82). While mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ) may influence ROS production, the issue is complex, whereby both hyperpolarization and depolarization have been associated with ROS production, likely depending on pharmacological agents and substrates being used, and the respiratory and redox environment of the mitochondria (24, 25, 31, 80, 83). For example, diazoxide and BMS-191095, selective openers of MitoK+ATP, decrease the mitochondrial membrane potential in the cerebrovasculature (83). Interestingly only diazoxide, but not BMS-191095, increases ROS production by mitochondria (83). Conversely, diazoxide elicits increased mitochondrial ROS production in HAECs (25), similar to cardiac and liver mitochondria (84).

Nonetheless, in isolated mitochondria from BAECs, angiotensin II leads to a collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent ROS production (24). The MitoK+ATP channel inhibitors (5-hydroxydecanoate and 5-HD and glibenclamide) prevented angiotensin II-induced depolarization and mitochondrial ROS production (24). Regarding the mPTP, blockade of the mPTP by cyclosporine-A decreases H2O2 release from mitochondria isolated from angiotensin II-treated BAECs (24). This is important because H2O2 is a well-established protein kinase C activator (85). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that cytoplasmic ROS elicit mitochondrial depolarization, at least in part through opening MitoK+ATP channels, which results in mitochondrial ROS release by respiratory complexes and the mPTP. The release of mitochondrial ROS further activates NADPH oxidase via protein kinase C, resulting in increased cytoplasmic production and reduced NO bioavailability (Fig. 3).

Further support for the potential role of mitochondrial Δψ and ROS production on vascular dysfunction comes from data demonstrating that compared with control participants, arterioles and circulating mononuclear cells from human participants with obesity and type 2 diabetes are characterized by mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization, reduced mitochondrial mass, and greater ROS production (31, 86, 87). Importantly, the physiological differences in mitochondrial membrane polarity were observed under basal conditions and were modest compared with stimulated polarity changes caused by FCCP (87). However, the administration of mitochondrial uncoupling agents (reducing membrane polarity) and the mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant Mito-TEMPO reduced mitochondrial ROS and restored NO bioavailability and endothelium-dependent dilation (31). These findings suggest that mitochondrial alterations including membrane hyperpolarization reduced NO bioavailability and vascular function (31, 86). In this investigation, mitochondrial ROS production in monocytes was also negatively correlated with brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (31), a well-established marker of endothelial function in humans. In summary, taken together these findings underscore the nuance of the MitoK+ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential, whereby by both depolarization and hyperpolarization have been potentially implicated in regulating ROS production. Regarding Δψ specifically, changes in ΔΨ produced by various treatments may be merely coincidental or of minor physiological importance. Thus additional data are needed to determine if MitoK+ATP and mitochondrial membrane potential could be pursued for therapeutic purposes.

Uncoupling proteins.

Uncoupling protein (UCPs) are mitochondrial inner membrane proteins that regulate proton flux across the inner membrane (88, 89). Specifically, UCPs dissipate the proton gradient generated by the electron transport chain whereby protons from the mitochondrial matrix are pumped to the mitochondrial intermembrane space, thus uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. For this reason, UCPs (e.g., UCP1) were initially largely thought of for their role in increasing thermogenesis in metabolically active tissues (88, 89); however, there is preclinical evidence that in the vasculature, UCPs play a role in regulating Δψ and ROS production (90–92).

Among the five mammalian UCP isoforms (UCP 1–5), the expression of UCP2 and UCP3 is detected at the mRNA and protein level in the vasculature (91, 93). However, UCP2 is the primary UCP isoform involved in the regulation of endothelial cell homeostasis, including ROS production, mitochondrial Δψ, intracellular Ca2+ handling, apoptosis, and metabolism by altering proton leak (93–96). In the vasculature, UCP2 promotes downregulation of mitochondrial ROS formation through negative feedback (95). For example, exposing multiple endothelial cell types [e.g., human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and HAECs] to hyperglycemia, a well-documented stimulus for ROS production, leads to increased UCP2 expression (97, 98). Moreover, in endothelial cells exposed to hyperglycemia UCP1 and UCP2 overexpression attenuates mitochondrial ROS formation (99, 100) and overexpression of UCP2 attenuates mitochondrial ROS production in the context of an in vitro lipemia/metabolic syndrome model (101). Overexpression of UCP2 in mice also attenuates salt-induced oxidative stress and reductions in NO bioavailability (102). Taken together, these preclinical findings suggest that UCP2 plays a critical role in regulating ROS production among other facets of mitochondrial homeostasis. Additional data are needed to determine if vascular UCP2 levels are altered with aging or disease and whether these changes may be modulated by lifestyle healthy factors such as exercise and diet in humans.

Impaired endogenous mitochondrial antioxidant defense.

The vasculature contains several antioxidant defense mechanisms to combat excess mitochondria-derived ROS and maintain redox homeostasis. The SOD isozymes catalyze the conversion of into H2O2. The most relevant endogenous mitochondrial antioxidant mechanism in the context of vascular function and increased NO bioavailability is SOD2. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that in conditions of reduced NO bioavailability H2O2 serves as an alternative vasodilator (95, 103, 104) and can serve to increase eNOS expression (105, 106). Thus the SOD enzymes preserve vasodilation by both increasing NO bioavailability or producing H2O2. In SOD2 knockout rodents, there is an acceleration of age-related circulating , arterial stiffening, and pathological arterial remodeling (107). Sirtuin-3 (SIRT-3) is a mitochondrial localized deacetylase that plays a central role in the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system via activation of SOD2 activity (108). Indeed, SIRT-3 knockout in preclinical models and SIRT-3 polymorphisms in human subjects are associated with pulmonary artery hypertension (109). Other antioxidants that play a role in modulating mitochondrial ROS and maintaining vascular health include glutathione peroxidases, peroxiredoxins, catalase, and thioredoxins. Specific strategies that can be used to target or mimic these pathways are discussed further later on in this review.

ABERRANT MITOCHONDRIAL QUALITY CONTROL ASSOCIATED WITH VASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Mitochondrial biogenesis, fission, fusion, and mitophagy processes, collectively referred to as mitochondrial quality control, are required for optimal mitochondrial health and function. Age- and disease-related irregularities in mitochondria quality control in the vasculature leading to endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and atherosclerosis have gained attention over the last two decades (9, 11, 110). The overarching theme of the current evidence is that compromised vascular tissue is accompanied by a decrease in mitochondrial biogenesis regulators peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) (21). In addition, there appears to be a disturbed dynamic balance in key regulators of fission [dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) and fission-1 (FIS1)] and fusion [transmembrane GTPAses mitofusion-1 (MFN1) and 2 (MFN-2) and the optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1)]. Current evidence consists of contrasting reports of both increases and decreases in these markers of fission and fusion associated with vascular dysfunction (111–113). Early in the aging process an increased expression of the mitophagy markers phosphate and tensin homolog-induced kinase protein 1 (PINK1) and E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin are reported (110). However, as aging progresses there is a substantial reduction in mitophagy that is associated with increases in arterial stiffness (114). Preclinical work has demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction leads to an accumulation of Parkin, particularly in the VSM, indicative of increased mitophagy to remove damaged mitochondria in the aging aorta (110). Importantly, these mitochondrial impairments in the aorta directly promote atherosclerosis independently of hyperlipidemia and primed the aging vasculature to enhanced atherosclerosis in the setting of hyperlipidemia (110). These impairments in vascular mitochondrial function are driven by increased levels of inflammation (110). In support, recent evidence has linked activation of the inflammation mediator NF-κB to increased mitochondrial fission that potentiates leukocyte adhesion (115). Moreover, in preclinical studies of isolated VSMCs and intact cerebral resistance vessels, abnormally increased mitochondrial dynamics (particularly increased fusion) support VSMC proliferation and migration, processes that are central to the development of vascular hyperplasia and neointima formation (22). BCL2-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) is an additional receptor that is integral to priming mitophagy. In vitro VSMC studies have shown that suppression of BNIP3-mediated mitophagy is implicated in vascular calcification (116).

Apart from its critical role in biogenesis, PGC-1α plays a central role in ROS signaling and antioxidant defense. Specifically, PGC-1α increases SOD2, catalase, and thiroredoxin 2 expression (98, 117) and PGC-1α overexpression directly improves NO bioavailability (98, 117). In patients with coronary artery disease, it is well established that there is a reduction in NO bioavailability and a heightened reliance on H2O2-mediated vasodilation (103, 118, 119). However, a recent investigation demonstrated that PGC-1α overexpression in ex vivo arterioles from patients with coronary artery disease suppresses mitochondrial H2O2 production and resensitizes the arterioles to nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, demonstrating a restoration of NO bioavailability (120). In contrast, downregulation of PGC-1α in arterioles from control participants is characterized by greater H2O2-mediated dilation (i.e., a phenotype similar to coronary artery disease). Thus PGC-1α-targeted therapeutic strategies may improve aging and disease-related vascular dysfunction via improvements in mitochondrial biogenesis as well as an increase in endogenous antioxidant defenses. Although these mitochondrial processes in the vasculature are more difficult to assess in human subjects or translational models (and therefore not as well established), the polymorphisms of PGC-1α have been linked with vascular diseases such as hypertension (121) and coronary artery disease (122) in epidemiological studies.

“Energy-sensing” pathways play a key role in regulating mitochondrial quality control. In this respect, a key player in the regulation of energy metabolism, AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), is a well-established upstream activator of biogenesis, fission, and mitophagy (123). Sirtuins, a class of NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases, also play a role in regulating these mitochondrial processes. Sirtuin-1 (SIRT-1) plays a functional role in regulating PGC-1α, particularly in response to increased shear stress (124) and is therefore a key component of biogenesis (125). AMPK has also been shown to enhance SIRT-1 activity (126). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an energy-sensing signaling hub that is central in controlling anabolic processes. While mTOR activation plays a role in activating mitochondrial biogenesis and inhibiting autophagy, chronic hyperactivation of this pathway that accompanies age and disease is linked with deleterious mitochondrial quality control and impaired vascular function (127–129). Suppression of the mTOR pathway has therefore been linked with an increased life span in model organisms (130). In this respect, mTOR inhibition elicits mitochondrial hyperfusion resulting in an elongated mitochondrial phenotype that enhances cell survival through reducing excessive fission and mitophagy (131). Interestingly, mTOR is repressed through activation of the AMPK pathway (129). Energy stressing strategies such as aerobic exercise and caloric restriction are potent activators of AMPK and SIRT pathways, and inhibitors of mTOR hold promise as therapeutic strategies to improve mitochondrial and vascular dysfunction and are discussed in further detail later in this review.

MITOCHONDRIAL Ca2+ IMBALANCE AND VASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

Intracellular Ca2+ is essential for maintaining endothelial cell and VSMC integrity and function (132). In endothelial cells, agonist-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ lead to eNOS activation and subsequent NO production (132). In the VSMCs, intracellular Ca2+ signaling plays a key role in modulating VSMC vasomotive activity (132). By interacting with the endoplasmic reticulum, the mitochondria play a central role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels via mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and cycling (133, 134) (Fig. 1). In addition to contributing to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, mitochondrial Ca2+ levels play integral roles in mitochondrial metabolism (135), cell signaling (136, 137), biogenesis, and morphology (136), all of which are pertinent to optimal vascular function.

Several preclinical studies have linked mitochondrial Ca2+ handling with vascular cell function and viability. Cultured HUVECs exposed to hyperglycemic conditions significantly increase mitochondrial Ca2+ content following histamine stimulation compared with normoglycemic cells (138). Simulated ischemia-reperfusion conditions activate mitochondrial Ca2+ oscillations in human aortic endothelial cells (139), an observation that has also been documented in cells exposed to disproportionate increases in ROS (140). In addition, abnormally increased levels of H2O2 have been shown to inhibit the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, therefore increasing mitochondrial Ca2+ content via reduced Ca2+ release (141). The resultant Ca2+ overload observed under all these conditions leads to aberrant mitochondrial morphology and Ca2+ signaling that predisposes the endothelial cells to replicative senescence and apoptosis (136). As reviewed previously (11, 142), increases in mitochondrial Ca2+ can also increase ROS production through stimulation of the respiratory complexes and mPTP, as well promotion of apoptosis via release of cytochrome C. Hexokinase, an enzyme that catalyzes the phosphorylation of glucose during glycolysis, has also been shown to play a role in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis in the endothelium by inhibiting the voltage-dependent anion channel Ca2+ transporter (143). Preclinical studies of hyperglycemia in coronary endothelial cells have demonstrated that increases hexokinase expression result in decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations and subsequent reductions in ROS (143). Hexokinases may therefore hold potential as a mitochondrial therapeutic target. Translational studies investigating the role of abnormal mitochondrial Ca2+ handling on vascular endothelial function are lacking and warrant investigation in future studies.

MITOCHONDRIAL SEX DIFFERENCES AND VASCULAR FUNCTION

A large body of research has established distinct sex differences in mitochondrial function across and array of different organs and tissue types. In general, female mitochondria have higher antioxidant expression, less oxidant damage, more efficient calcium handling, increased expression of mitochondrial quality control such as PCG-1α MFN-2, and better activation of the SIRT-1 and AMPK pathways (144). Sex-differences specific to the vascular mitochondria are less established. However, preclinical studies in cerebral arteries show upregulation in PGC-1α, increased resistance to oxidant damage, and a superior bioenergetic function profile in females compared with males (145, 146). In vitro studies of cultured cerebrovascular endothelial cells suggest that these sex differences in mitochondrial function, particularly those pertaining to reduced mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress production and oxidant protection in females, are largely mediated by estrogen and the endothelial estrogen receptor-α (147). Translational studies of these findings to human subjects remain scant and warrant investigation in future studies. Additionally, aberrant vascular mitochondrial function is postulated to contribute to postmenopausal declines in vascular function; however, human subject studies in this area are lacking (148, 149). One study including postmenopausal women has shown a role for mitochondria-derived oxidative stress in age-related vascular dysfunction (27). However, this study did not specifically investigate sex differences. Finally, the role of predominantly male sex hormones such as testosterone, on vascular mitochondrial function are largely unknown.

MITOCHONDRIAL-TARGETED THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVED VASCULAR HEALTH AND FUNCTION

Caloric Restriction

Therapeutic caloric restriction (CR) entails reducing daily habitual caloric intake without compromising essential nutrient intake. This lifestyle intervention is a robust strategy for slowing aging processes, increasing resilience to stressors and preventing the development of chronic disease (150). There is abundant preclinical evidence demonstrating the efficacy of CR in improving both vascular endothelial function and arterial stiffness, predominantly though reducing oxidative stress and inflammation (151–159). Although the mechanisms of CR-related improvements in vascular function are multifaceted, improvements in mitochondrial function may play an important role. Certainly, CR is a potent activator of the AMPK and SIRT-1 pathways with feedforward increases in PCG-1 and nuclear respiratory factor 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2) expression that enhance mitochondrial biogenesis (21, 152, 155, 160). CR-related reductions in DRP-1 and FIS-1, indicative of decreased fission, also point toward altered mitochondrial quality control (161, 162). In addition, CR increases SIRT-3 expression that activates SOD2 via deacetylation, thus contributing to reductions in oxidative stress (108). Whether these CR-associated improvements in mitochondrial function are evident in vascular mitochondria, and the impact on vascular function, warrants further investigation.

Despite the wealth of preclinical evidence demonstrating the health and vascular benefits associated with CR, lifelong CR in humans is not pragmatic. In addition to poor intervention compliance, adverse alterations in lean mass and reductions in immune function make this an unpractical and unsafe intervention, particularly for older and disease populations that are already susceptible to frailty (163, 164). As such, time-restricted feeding (or other intermittent fasting paradigms) has emerged as alternative dietary strategy that holds promise for inducing some of the same beneficial physiological responses as CR (165, 166). Indeed, this approach has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in healthy older adults (165). However, the vascular benefits of these interventions have not yet been established. Future studies documenting the safety and practicality of time restricted feeding in populations with chronic disorders are necessary, in addition to clinical trials that investigate the chronic efficacy of this approach on mitochondrial and vascular health.

Exercise Training

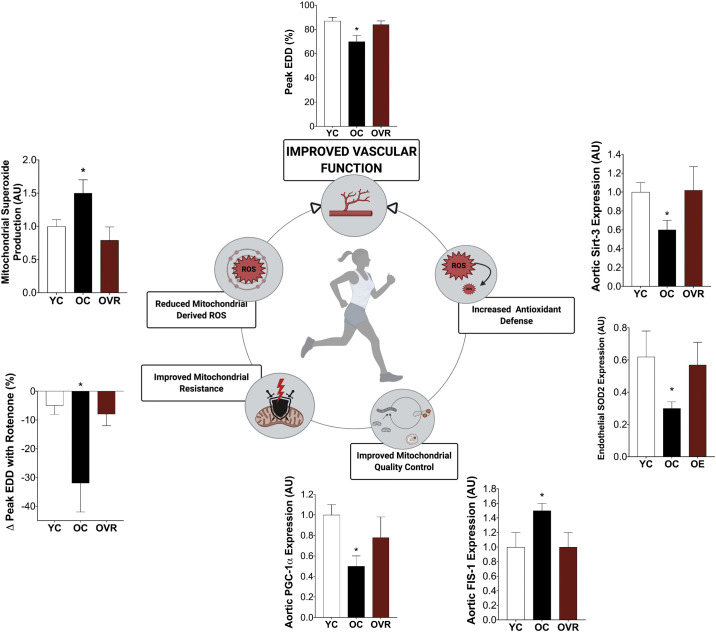

Although aerobic exercise is recognized as a powerful stimulus for enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and function in skeletal muscle (167), the effects of exercise on vascular mitochondria function is less established. Preclinical and translational studies have consistently shown that aerobic exercise improves and restores age- and disease-related vascular endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness (168, 169). Specifically, the beneficial effects of aerobic exercise on endothelial function are mediated, at least in part, by improvements in vascular mitochondria function (Fig. 4) (170, 171). Moreover, improvements in endothelial function following exercise training are accompanied by increased aortic protein expression of PGC-1α and declines in FIS1, indicative of increased mitochondrial biogenesis and reduced fission, respectively (172), and this has been replicated in other trials (173). Furthermore, in both young and old animals, voluntary wheel running enhanced the vascular resistance to an acute application of mitochondrial stressors (174). Consistent with these observations, exercise has been shown to improve age-related impairments in aortic stiffening by upregulating aortic PGC-1α expression, reducing in mitochondrial-derived ROS, reducing mitochondrial swelling, and restoring mtDNA content and respiration (175). These findings suggest a role for the mitochondria in exercise-related improvements in vascular compliance.

Figure 4.

Translational evidence in aging supports a role for exercise training in improving vascular function that is largely mediated by improvements in vascular mitochondrial function. Improvements in mitochondrial quality control, mitochondrial resistance (to mitochondrial stressor, rotenone), and mitochondrial redox balance accompany exercise-related improvements in vascular function. This holds promise for exercise as a mitochondrial-targeted therapeutic strategy to improve vascular function in chronic diseases that have a pathophysiology consistent with accelerated vascular aging. Adapted from our own previously published data (26, 172). EDD, endothelial-dependent dilation; FIS-1, fission- 1; OC, old control; OE, old habitual exercises (human subjects); OVR, old voluntary wheel running (preclinical); PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1-α; SIRT-3, sirtuin-3; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2; YC, young control; AU, arbitrary units. *P < 0.05 vs. YC and OVR/OE. Data are means (SE). Figure was made with biorender.com and published with permission.

Potential underlying mechanisms for exercise-related improvements in vascular mitochondrial function include activation of energy sensing pathways and reductions in oxidative stress. Similar to CR, exercise activates the AMPK pathway with subsequent improvements in mitochondria quality control through biogenesis, fission-fusion, and mitophagy (123, 174, 175). Additionally, increases in vascular SIRT-1 expression associated with exercise training have been linked with beneficial improvements in vascular function (124, 171, 176). The effects of exercise training on vascular mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in human subjects have not been extensively studied and warrant further investigation.

Exercise-related improvements in vascular mitochondrial function also appear to be largely mediated by reductions in oxidative stress through the upregulation of endogenous mitochondrial antioxidants such as catalase, SOD2 and SIRT-3 (Fig. 4) (171, 172, 177). Interestingly, a preclinical study comparing the effects of exercise on aortic mitochondria in normocholesterolemic and hypercholesteremic mice demonstrated exercise-related improvements in SOD2 expression in normocholesterolemic but not hypercholesteremic mice (177). In addition, markers of mitochondrial health (adenine nucleotide translocator activity) and mtDNA damage (mtDNA lesions) were improved in normocholesterolemic but worsened in hypercholesteremic animals following exercise (177). A suggested explanation for such findings is that preexistent CVD risk factors that increase basal levels of oxidative stress may lead to attenuated exercise training adaptations (169, 177). In support, attenuated exercise-related improvements in endothelial function and arterial stiffness have certainly been reported in human subjects with chronic kidney disease (178), metabolic syndrome (169), and postmenopausal women (148). Therefore, in populations that have attenuated training adaptations, future studies are warranted to investigate whether combining mitochondrial-targeted nutraceutical or pharmaceutical strategies with exercise training may enhance vascular adaptations.

Mitochondria-Acting Antioxidants

The significant role in vascular dysfunction of excess mitochondrial ROS and associated oxidative damage make direct targeting of these processes an appealing therapeutic approach. While traditional antioxidants such as exogenous vitamins C and E have been unsuccessful in large-scale clinical trials for CVD endpoints (179), novel antioxidant compounds targeting specific sources of ROS (e.g., mitochondria) may hold promise (180). Indeed, 2 yr of supplementation with coenzyme Q10, which is thought to act primarily on mitochondria and have antioxidant properties, reduces major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with heart failure (181). Chronic supplementation with coenzyme Q10 improves endothelial function in a variety of populations (182), including ischemic heart disease (183), type 2 diabetes (184, 185), and otherwise healthy individuals with endothelial dysfunction (186). More recently, supplementation with the reduced form of coenzyme Q10, ubiquinol, was found to improve endothelial function, assessed by microvascular perfusion, in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome; the beneficial effects of ubiquinol were attributed, in part, to improved mitochondrial health and reduced oxidative stress (187). Although not a consistent finding (188), some evidence suggests that coenzyme Q10 may also reduce arterial stiffness (189).

Other approaches for more precisely targeting mitochondrial ROS-related processes include mitochondrial-specific antioxidants, such as MitoQ. MitoQ consists of a derivative of ubiquinol as the antioxidant moiety conjugated to the lipophilic cation, triphenylphosphonium (TPP) (190). The properties of TPP (a lipophilic cation) enable MitoQ to accumulate in the mitochondria where it acts as a chain breaking antioxidant blocking lipid peroxidation and may also decrease production by reverse electron transport at complex I of the electron transport chain (190–192). Preclinical data demonstrate that chronic supplementation with MitoQ completely reversed age-related declines in NO-mediated endothelial function by suppressing mitochondrial ROS with no effects in young animals (28). MitoQ has also been shown to prevent development of endothelial dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats (193, 194) and doxorubicin-treated mice (195) a model of chemotherapy-associated accelerated vascular aging. In regard to arterial stiffness, MitoQ attenuated age-associated increases in aortic stiffness (26). The de-stiffening effects of MitoQ with aging were attributed to an attenuation of age-associated declines in elastin content (26), consistent with the concept that mtROS may accelerate elastin degradation demonstrated in MnSOD-deficient mice (107).

The preclinical findings with mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants have begun to be translated to humans. MitoQ was shown to improve endothelium-dependent dilation of isolated skeletal muscle feed arteries from older adults, with no effect on arteries from young healthy subjects (196). These data are in agreement with beneficial effects of acute administration of another mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant, mitoTEMPO, which has been shown to improve endothelium-dependent dilation in arterioles isolated from adipose tissue biopsies in patients with type 2 diabetes (31) and cutaneous microvascular function in patients with chronic kidney disease (30). Moreover, acute administration of MitoQ improved endothelial function in patients with peripheral artery disease (32). Recently, chronic supplementation with MitoQ in older adults was found to improve endothelial function by reducing mitochondrial ROS (27) and may improve endothelial function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (197). MitoQ also reduced arterial stiffness in older adults exhibiting typical age-associated increases in aortic stiffness (27). Clinical trials are underway to assess the efficacy of MitoQ for improving vascular function in chronic kidney disease (NCT02364648), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (NCT03960073), peripheral artery disease (NCT03506633), and mild cognitive impairment (NCT03514875).

Accumulating evidence supports the efficacy of Szeto-Schiller tetra-peptides such as SS-31 for combating age- and disease-related changes in physiological function, including vascular function (198, 199). Although multiple mitochondrial processes are likely affected, antioxidant properties and the ability of these compounds to stabilize the mitochondrial membrane lipid cardiolipin have been advanced as the primary mechanisms responsible for the beneficial effects of these peptides. Indeed, SS-31 restored NO-mediated cerebrovascular function in old mice and normalized mitochondrial ROS production and mitochondrial respiration in cerebrovascular endothelial cells isolated from old rats to levels in cells from young animals (199). Moreover, SS-31 prevents the traumatic brain injury-induced increase in mitochondrial ROS in cerebral arteries from spontaneously hypertensive stroke prone rats (200). Although some data from a small, randomized control trial in humans suggested beneficial effects of a single infusion of SS-31 on cardiac function (201), these effects were not supported in a larger trial with chronic administration (202). It is currently unknown if these peptides are efficacious for improving endothelial function or reducing arterial stiffness. Overall, more research with larger and longer trials is needed to establish, confirm and/or extend the effects of mitochondria-targeted antioxidants and related compounds on vascular function.

Caloric-Restriction Mimetics

As discussed previously, regular CR is a powerful lifestyle strategy for improving vascular function likely, at least in part, by enhancing mitochondrial health. However, despite the recognized benefits of CR, issues with adherence preclude its widespread implementation (166). As a result, there is considerable interest in more practical and adherable alternatives that may recapitulate some of the benefits of CR (166). These alternatives include pharmaceutical and/or nutraceutical modulators of “energy-sensing” pathways thought to mediate the benefits of CR such as activation of sirtuin- and AMPK-regulated signaling and suppression of progrowth mediators including mTOR and insulin-like growth factor-1 (203). These cellular signaling cascades, in turn, regulate the expression of stress response programs, many of which involve the central mitochondrial quality control processes of biogenesis and mitophagy. Activation of these quality control processes is thought to degrade and recycle damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria (via mitophagy) and replace them with healthier mitochondria (via mitochondria biogenesis).

Sirtuin activation.

Activation of sirtuins is also a focus of these strategies (166). The specific small-molecule activator of SIRT-1 SRT1720 improved endothelial function in old mice by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation and augmenting cyclooxygenase vasodilatory signaling (204). The nutraceutical resveratrol, a polyphenol purported to activate sirtuins and have antioxidant effects, has been shown to improve vascular function in preclinical models (205, 206) and human subjects (207–211), and the latter has been associated with favorable changes in markers of mitochondrial health and function (212).

Another promising nutraceutical-based approach for sirtuin activation is increasing levels of NAD+, which is a critical cofactor for sirtuin activity (213). The most well-studied approach to boosting NAD+ involves supplementation with the key endogenous NAD+ salvage pathway intermediates nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR) (213). NMN reversed age-related reductions in NO-mediated endothelial function and reduced oxidative stress (214, 215). Moreover, NMN supplementation improved cerebrovascular function in old mice by decreasing mitochondrial ROS (214) and was associated with alterations in gene expression consistent with enhanced mitochondrial rejuvenation/biogenesis (216). NMN administration also improved NO production and normalized multiple aspects of mitochondrial function including ROS production, bioenergetics and membrane potential in primary cerebrovascular endothelial cells from old rats (214). Mechanistically, the beneficial effects of NMN on vascular function may also be linked to activation of the mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT-3, which, in turn, reverses hyperacetylation of numerous mitochondrial proteins (e.g., SOD2) and improves mitochondrial function (217, 218). Although NMN is not yet readily available for chronic supplementation in humans, current clinical trials are underway to extend the benefits of NAD+-boosting strategies to humans via NR supplementation. Indeed, a pilot study found that NR effectively raises NAD+ and may reduce aortic stiffness and blood pressure in healthy older adults (219).

Autophagy/mitophagy stimulation.

Many of the effects of CR-mediated activation of the energy-sensing pathways discussed above are attributed to the activation of autophagy and mitophagy. Select nutraceuticals are thought to stimulate these processes directly and have positive effects on vascular function. For example, spermidine is a polyamine found in foods such as soy and some aged cheeses that extends life span in model organisms and delays cardiac aging in rodents (220–222). The primary mechanism of action of spermidine is activation of autophagy and mitophagy (220–222). Spermidine improved endothelial function in old mice by increasing NO bioavailability and decreasing oxidative stress (223). Spermidine also reversed age- and high-fat diet-induced declines in mitochondrial function and atherosclerosis via mitophagy activation (110). In biopsied endothelial cells from diabetic humans, spermidine restored NO production (224). In addition, spermidine reversed age-associated increases in aortic stiffness in old mice by reducing abundance of advanced glycation end products (223). Early pilot trials in humans suggest that spermidine is safe for chronic administration (225, 226), but the clinical translation of the vascular effects remain to be established. Trehalose is another autophagy/mitophagy-activating nutraceutical found in mushrooms and honey (114, 227, 228). Trehalose improved endothelial function in old mice, diabetic, obese mice, and spontaneously hypertensive adult rats (227, 229, 230) and reduced aortic stiffness with aging in mice (114). In these preclinical studies, the beneficial effects of trehalose on vascular function appear to be enhanced mitophagy, reduced p66shc activation, reduced oxidative stress, and an increased resistance to mitochondrial stressors (114). Trehalose also improved NO-mediated endothelial function in older adults (231), but more research is needed to confirm these effects in humans and elucidate the role of autophagy.

AMPK activation and inhibition of mTOR.

Pharmacological modulation of AMPK reverses age-related reductions in endothelial function, without altering NO bioavailability, and decreases arterial stiffening in mice (232). Although the mechanisms responsible for these effects are multifactorial, current evidence suggests a role for mitochondria, consistent with the modulation of AMPK signaling in other tissues (233, 234). For example, the antidiabetic drug Metformin, which improves vascular function in certain clinical populations (235), enhanced endothelial function by moderating dynamin-related protein 1-associated mitochondrial fission and decreasing mtROS in an AMPK-dependent manner in a mouse model of diabetes (236). In agreement with these findings, improved endothelial function with the AMPK activator AICAR in young mice was attributed to enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis in endothelial cells, which was dependent on intact eNOS and (paradoxically) mTOR signaling (237). Moreover, inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin improves NO-dependent endothelial function and reversed aortic stiffening in old mice (238). However, although mitochondrial mechanisms have been established in other tissues (239–241), evidence for direct mitochondrial effects of rapamycin in the vasculature is currently limited.

Inorganic Nitrites and Nitrates

Due to the centrality of age- and disease-related reductions in NO bioavailability in vascular dysfunction, strategies that enhance NO signaling have potential as effective treatments. Of the variety of pharmaceutical and nutraceutical approaches proposed or under investigation, supplementation of inorganic nitrites and nitrates are among the most promising for improving cardiovascular health (242). Indeed, in addition to the antihypertensive effects of these compounds, there is a considerable body of evidence supporting the ability of inorganic nitrites and nitrates to enhance endothelial function and reduce arterial stiffness (243–248). A possible mechanism of action of these compounds is modulation of mitochondrial function (249), which is consistent with the role of NO as an activator of mitochondrial biogenesis (250–252). Although this mechanism of action remains to be convincingly documented in the vasculature, initial evidence suggests that sodium nitrite supplementation in old mice improves endothelial function by ameliorating basal mitochondrial ROS, which is associated with enhanced resistance to the mitochondrial stressor, rotenone (253). Given the growing popularity of inorganic nitrate supplementation, it will be important for future studies to elucidate how this approach affects mitochondrial function in humans.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

It is well established that the mitochondria are key players in vascular homeostasis by virtue of their ROS generating capabilities and their role in calcium handling, both of which are integral for efficient cell signaling. As such, age- and disease-related mitochondrial impairments are linked with vascular endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness, both of which are independently associated with CVD incidence. Importantly, while this review largely focuses on the role of mitochondrial dysfunction as a contributor to endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness, there remains a gap in knowledge in the field with regards to the contribution of VSMC mitochondrial dysfunction to vascular function. Future investigations in this are warranted.

Mitochondrial-derived ROS are essential for optimal cell signaling and are tightly regulated by electron leak at complexes I and III, mitochondrial membrane potential, uncoupling proteins, and endogenous antioxidant defenses. Age- and disease-related impairments in these mitochondria ROS mediators lead\ to excessive ROS production that culminates in oxidative stress. In addition, cross talk from abnormally increased NADPH-mediated ROS that is characteristic of age and disease processes initiates further increases in mitochondrial-derived ROS. Mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress has been implicated in vascular endothelial dysfunction via reduction in NO production and bioavailability and increased arterial stiffness via collagen deposition and elastin degradation. Mitochondrial quality control, regulated by biogenesis, fission, fusion, and mitophagy, also plays a key role is vascular homeostasis. Preclinical studies have demonstrated age and disease reductions in mitochondrial biogenesis and abnormal fission, fusion, and mitophagy within the vasculature that impair the endogenous mitochondrial antioxidant defenses, increase arterial stiffness, and prime atherosclerosis. The mitochondria play an important role in Ca2+ homeostasis that is essential for optimal vascular function. Mitochondrial Ca2+ cycling is not only important for cell signaling but also contributes to ROS signaling and mitochondrial quality control, all of which are critical to vascular function. In this respect, it is important to note that while presented individually in this review, these mitochondrial functions that are pertinent to vascular homeostasis are highly integrated systems (Fig. 1).

A summary of the available evidence for lifestyle, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical mitochondrial-targeted interventions to improve vascular function is provided in Fig. 2. Lifestyle interventions such as exercise and calorie restriction are effective strategies to improve vascular function that may be partly mediated through improvements in vascular mitochondrial function. In addition, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants, and pharmacological therapies that target energy-sensing pathways hold promise for improving vascular function. Both lifestyle and mitochondrial-targeted pharmaceutical strategies appear to improve vascular mitochondrial function through reductions in oxidative stress and enhancing mitochondrial quality control. While mitochondrial-targeted interventions have shown efficacy at improving vascular function in preclinical studies, there is a need to establish these therapies in translational and clinical trials.

In conclusion, there is abundant evidence that abnormal vascular mitochondrial function is implicated in vascular dysfunction in aging and disease populations with a heightened cardiovascular burden. Thus it is important biomedical research community to continue to further investigate mitochondrial dysregulation as an attractive therapeutic target for vascular dysfunction. Strategies aimed at improving vascular mitochondria function hold promise for improving vascular function and therefore decreasing CVD risk in the growing aging population in addition to chronic disease populations that exhibit an “accelerated aging” pathophysiology.

GRANTS

This study was supported by American Heart Association Grant 19CDA34740002 (to D.L.K.); National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant K01-HL-147998 (to A.T.R.); NIH Grants AG-049451, HL-107120, AG-053009, AG-000279, and DK-115524 (to M.J.R. and D.R.S.); and NIH Grant HL-113514 and American Heart Association Grant 17GRNT336704262 (to D.G.E.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.L.K., A.T.R., M.J.R., D.R.S., and D.G.E. conceived and designed research; D.L.K. and A.T.R. prepared figures; D.L.K., A.T.R., M.J.R., and D.G.E. drafted manuscript; D.L.K., A.T.R., M.J.R., D.R.S., and D.G.E. edited and revised manuscript; D.L.K., A.T.R., M.J.R., D.R.S., and D.G.E. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 139: e56–e528, 2019. [Erratum in Circulation 141: e33, 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Piña IL, Trogdon JG, Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 6: 606–619, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Giles CM, Flax C, Long MW, Gortmaker SL. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med 381: 2440–2450, 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1909301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle JP, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KM, Hoerger TJ, Geiss LS, Chen H, Thompson TJ. Projection of diabetes burden through 2050: impact of changing demography and disease prevalence in the U.S. Diabetes Care 24: 1936–1940, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G , et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 70: 1–25, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seals DR, Alexander LM. Vascular aging. J Appl Physiol (1985) 125: 1841–1842, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00448.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Pencina MJ, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, Benjamin EJ. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 121: 505–511, 2010. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeboah J, Crouse JR, Hsu FC, Burke GL, Herrington DM. Brachial flow-mediated dilation predicts incident cardiovascular events in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 115: 2390–2397, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossman MJ, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Clayton ZS, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Targeting mitochondrial fitness as a strategy for healthy vascular aging. Clin Sci (Lond) 134: 1491–1519, 2020. doi: 10.1042/CS20190559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz-Vegas A, Sanchez-Aguilera P, Krycer JR, Morales PE, Monsalves-Alvarez M, Cifuentes M, Rothermel BA, Lavandero S. Is mitochondrial dysfunction a common root of noncommunicable chronic diseases? Endocr Rev 41: 491–517, 2020. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluge MA, Fetterman JL, Vita JA. Mitochondria and endothelial function. Circ Res 112: 1171–1188, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang X, Luo YX, Chen HZ, Liu DP. Mitochondria, endothelial cell function, and vascular diseases. Front Physiol 5: 175, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hom J, Sheu SS. Morphological dynamics of mitochondria–a special emphasis on cardiac muscle cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 811–820, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen S, Nielsen J, Hansen CN, Nielsen LB, Wibrand F, Stride N, Schroder HD, Boushel R, Helge JW, Dela F, Hey-Mogensen M. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. J Physiol 590: 3349–3360, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldendorf WH, Cornford ME, Brown WJ. The large apparent work capability of the blood-brain barrier: a study of the mitochondrial content of capillary endothelial cells in brain and other tissues of the rat. Ann Neurol 1: 409–417, 1977. doi: 10.1002/ana.410010502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culic O, Gruwel ML, Schrader J. Energy turnover of vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C205–C213, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintero M, Colombo SL, Godfrey A, Moncada S. Mitochondria as signaling organelles in the vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 5379–5384, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601026103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Mehdi AB, Pastukh VM, Swiger BM, Reed DJ, Patel MR, Bardwell GC, Pastukh VV, Alexeyev MF, Gillespie MN. Perinuclear mitochondrial clustering creates an oxidant-rich nuclear domain required for hypoxia-induced transcription. Sci Signal 5: ra47, 2012. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Li H, Bubolz AH, Zhang DX, Gutterman DD. Endothelial cytoskeletal elements are critical for flow-mediated dilation in human coronary arterioles. Med Biol Eng Comput 46: 469–478, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0331-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SY, Gifford JR, Andtbacka RH, Trinity JD, Hyngstrom JR, Garten RS, Diakos NA, Ives SJ, Dela F, Larsen S, Drakos S, Richardson RS. Cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle mitochondrial respiration: are all mitochondria created equal? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H346–H352, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00227.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ungvari Z, Labinskyy N, Gupte S, Chander PN, Edwards JG, Csiszar A. Dysregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2121–H2128, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00012.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiong M, Cartes-Saavedra B, Norambuena-Soto I, Mondaca-Ruff D, Morales PE, García-Miguel M, Mellado R. Mitochondrial metabolism and the control of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Front Cell Dev Biol 2: 72, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2014.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai J, Kuo KH, Leo JM, van Breemen C, Lee CH. Rearrangement of the close contact between the mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum in airway smooth muscle. Cell Calcium 37: 333–340, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doughan AK, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Molecular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction: linking mitochondrial oxidative damage and vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res 102: 488–496, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dikalov SI, Nazarewicz RR, Bikineyeva A, Hilenski L, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Dikalova AE. Nox2-induced production of mitochondrial superoxide in angiotensin II-mediated endothelial oxidative stress and hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 281–294, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gioscia-Ryan RA, Battson ML, Cuevas LM, Eng JS, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapy with MitoQ ameliorates aortic stiffening in old mice. J Appl Physiol 124: 1194–1202, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00670.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossman MJ, Santos-Parker JR, Steward CA, Bispham NZ, Cuevas LM, Rosenberg HL, Woodward KA, Chonchol M, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Chronic supplementation with a mitochondrial antioxidant (MitoQ) improves vascular function in healthy older adults. Hypertension 71: 1056–1063, 2018. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gioscia-Ryan RA, LaRocca TJ, Sindler AL, Zigler MC, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (MitoQ) ameliorates age-related arterial endothelial dysfunction in mice. J Physiol 592: 2549–2561, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SH, Kwon OS, Park SY, Weavil JC, Hydren JR, Reese VR, Andtbacka RH, Hyngstrom JR, Richardson RS. Vasodilatory and vascular mitochondrial respiratory function with advancing age: evidence of a free radically-mediated link in the human vasculature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 318: R701–R711, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00268.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkman DL, Muth BJ, Ramick MG, Townsend RR, Edwards DG. Role of mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in microvascular dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 314: F423–F429, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00321.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kizhakekuttu TJ, Wang J, Dharmashankar K, Ying R, Gutterman DD, Vita JA, Widlansky ME. Adverse alterations in mitochondrial function contribute to type 2 diabetes mellitus-related endothelial dysfunction in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 2531–2539, 2012. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.256024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SY, Pekas EJ, Headid RJ 3rd, Son WM, Wooden TK, Song J, Layec G, Yadav SK, Mishra PK, Pipinos II. Acute mitochondrial antioxidant intake improves endothelial function, antioxidant enzyme activity, and exercise tolerance in patients with peripheral artery disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 319: H456–H467, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00235.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Candenas S. Mitochondrial uncoupling, ROS generation and cardioprotection. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1859: 940–950, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan SH, Chan JY. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species contribute to neurogenic hypertension. Physiology (Bethesda) 32: 308–321, 2017. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00006.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed JK, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and vascular function: less is more. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 673–675, 2013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.13.301039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang DX, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2023–H2031, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01283.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Touyz RM, Briones AM. Reactive oxygen species and vascular biology: implications in human hypertension. Hypertens Res 34: 5–14, 2011. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulz E, Gori T, Munzel T. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertens Res 34: 665–673, 2011. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dikalov SI, Nazarewicz RR. Angiotensin II-induced production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: potential mechanisms and relevance for cardiovascular disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal 19: 1085–1094, 2013. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li JM, Shah AM. Intracellular localization and preassembly of the NADPH oxidase complex in cultured endothelial cells . J Biol Chem 277: 19952–19960, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m110073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li JM, Shah AM. Mechanism of endothelial cell NADPH oxidase activation by angiotensin II. Role of the p47phox subunit. J Biol Chem 278: 12094–12100, 2003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C1424–C1437, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]