Abstract

Chordomas are rare and slow-growing locally destructive bone tumors that can develop in the craniospinal axis. It is commonly found in the sacrococcygeal region whereas only 25–35% are found in the clival region. Headache with neurological deficits are the most common clinical presentations. Complete surgical resection either via open or endoscopic endonasal approaches are the main mode of treatment. Here, we report a series of 5 cases of clival chordomas which was managed via endoscopic endonasal approaches in our center. A retrospective analysis of patients who had undergone endoscopic endonasal resection of clival chordoma in Sarawak General Hospital from 2014 to 2018. A total of 5 cases were operated on endoscopically via a combine effort of both the otorhinolaryngology team and the neurosurgical team during the study period from year 2013 to 2018. From our patient, 2 were female and 3 were male patients. The main clinical presentation was headache, squinting of eye and nasopharyngeal fullness. All our patient had endoscopic endonasal debulking of clival tumor done, with average of hospital stay from 9 – 23 days. Pos-operatively, patients were discharged back well. Endoscopic endonasal resection of clival chordomas gives good surgical resection results with low morbidity rates and therefore can be considered as a surgical option in centers where the surgical specialties are available.

Keywords: Endoscopic endonasal, Clival, Chordoma

Introduction

Chordomas are rare and slow growing locally destructive bone tumor with an incidence rate of 0.08 in 100,000 of population [1, 2]. It is more commonly found at the scaro-cocygeal region (50–60%), followed by the spheno-occipital region (25–35%) and the vertebral column (10%) [3]. Chordomas have a higher incidence in male compared to female [1].

Clival chordomas arises from fetal/ embryonal notochord remnants, that usually forms the nucleus pulposus of intervertebral discs, whereas, in the cephalic end of notochord will differentiate into the precursor for formation of sella and the posterior body of sphenoid, and basiocciput bone [4–6]. This malignant change usually occur between ages 50–60 years old, with low incident rate before 40 years old [7]. Its occurrence in children will present in aggressive pattern. The main aim of treatment is surgical resection. Patients with complete tumor resection has better prognosis.

Material and Methods

Surgical Technique

Endoscopic endonasal tumor resection and debulking of clival chordoma requires a team of trained otorhinolaryngologist and neurosurgeon. This procedure is performed under image guided surgery (IGS) guidance. A lumbar drain is placed after intubation. The nasal cavity is then packed with moffat’s solution (2 ml of cocaine 10%, 1 ml of adrenaline 1:1000, 4 ml of sodium bicarbonate 8.4% and 13 ml of normal saline). The Hadad–Bassagaisteguy nasoseptal flap is first raised and tucked into nasopharynx. A wide sphenoidectomy is then performed to visualize the orbital apex, optic-carotid recess, optic nerve, vidian nerve, internal carotid artery and superior clival recess. Tumor is then resected via a combination of sharp and blunt dissection. This is then followed by a multilayer reconstruction of the skull base defect using fat, fascia lata, fibrin glue and the nasoseptal flap which was harvested earlier. The nasal cavity is then packed using a size 14 Fr Foley’s catheter to support the flap and 2 merocele.

Cases

We report 5 cases of clival chordomas presented to us from year 2015–2018. All these 5 cases, endoscopic endonasal approach in resection of tumor was performed with near complete resection showed in the result.

Case 1

11 years old, presented with headache for 1-year, right eye squint and double vision for one-week associate with dizziness. Neither there is any body weakness or seizure, nor sign of hyper- or hypo-pituitary symptoms.

On examination, patient is alert full Glasgow coma scale (GCS) with normal vital signs. Neurological examination shows vertical diplopia on right lateral gaze. Otherwise, full muscle power with normal tone and reflexes. No unstable gait and no abnormal cellebellar sign.

Patient has contrast-enhanced computed topography (CECT), reported lesion appeared arising from dorsum sella. Features of an expansile lytic bone lesion from dorsum sella with chondroid matrix and heterogeneous enhancement. It is asymmetrical, encroaching right carvenous sinus, bulge posteriorly along clivus with clival erosion and sphenoid root erosion. MRI also reported Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also shows lesion arising from posterior clinoid process and dorsum sella with local infiltration.

Patient underwent endoscopic endonasal approach tumor excision and lumbar drain insertion with the intraoperative findings noted tumor involving dorsum sellae, posterior clinoid and upper portion of clivus, where the involving bone was soft and highly vascular, part of the dura anteriorly was invaded by tumor.

Case 2

13 years old boy with underlying thalassemia major with history of bone marrow transplant at the age of 2 years old presented with diplopia for 8 months associate with headache and multiple episode of epistaxis. Examination shows right VIth cranial nerve palsy and MRI showed pathological soft tissue growth related to posterior aspect of clivus and the anterior aspect of brainstem. Endoscopic endonasal approach of tumor excision done with minimal CSF leak upon tumor dissection which is stopped upon reconstruction. Post-operatively patient is well and stable and was discharged without any signs and symptoms of raised intracranial pressure.

Case 3

15 years old, Chinese lady who presented with headache for 2 days which is intermittent and generalized headache, aggravated by movement, associated with fever. Besides this, patient has history of rhinorrhea, nasal blockage and facial pain. On examination, patient is alert and orientated with full GCS. Neuromuscular examination shows full muscle power of both upper and lower limb with normal reflexes and normal sensation. Nasoendoscopy examination shows fullness over the nasopharynx. Patient has CT and MRI scan done which incidentally noted to have hyper-intense mass lesion arising from clivus extending internally encasing odontoid and anterior arch of C1.

Patient had posterior C1–2 fixation and fusion, left transarticular screw insertion done. After the fixation being done, endoscopic transnasal transphenoidal excision of clival tumor and c1/c2 resection performed.

Post-operatively, patient is well. She has a repeated contrasted CT scan done 1 year after the operation and was revealed there is no signs of local recurrence. Patient under regular observation and had restoration of normal life.

Case 4

20 years old lady was a known case of recurrent clival chordoma since age of 5 with the presentation of squint for 5 years old and headache with increase cranial pressure confirmed by CT scan since age of 10. She had history of right craniotomy and tumor debulking of tumor done in September 2005. Subsequently, another two-open approach of resection of tumor were performed which resulted defect in cranial nerve I, II, III, IV and VI. 13 years later, patient had a similar complain with MRI scan confirm huge ventral midline mass at the base of skull, measuring 7.2 × 7.8 × 6.0 cm. Similarly, revision of surgery was carried out with endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal method.

Case 5

57 years old, Iban, Gentleman with underlying hypertension, presented with diplopia at left lateral gaze for one month with blurring of vision and reduced sensation over the right side of face.

On examination, full GCS with normal vital signs. Neurological examination shows left eye convergence with left cranial nerve VIth nerve palsy. Other cranial nerve examination showed normal findings, normal muscle power, tone and reflexes.

Patient proceed with imaging investigation with contrast CT scan done which shows non enhancing extra-axial posterior fossa lesion with left cavernous sinus extension. This is further investigated with MRI where it reported lobulated lesion likely arising from clivus/ base of sella turcica with extension posteriorly into prepontine cistern and compressing onto the pons, measuring 4.2 × 2.4 × 2.8 cm, heterogeneously hypointense on T1W1, heterogeneously hyperintense on T2W1with ring and arc hypointensities.

Patient has endoscopic endonasal trans clival tumor excision and lumbar drain insertion done and intraoperative findings noted tumor seen when approaching the sphenoid sinus, pink-greyish and well-circumscribed tumor extending into clival region.

Postoperative repeated CT scan done noted residual clival tumor. Therefore, patient went through second stage endoscopic endonasal trans clival tumor resection 4 days after first operation.

After both the endoscopic operation, patient is well in ward and able to discharge from hospital without any complication.

Discussion

Clival chordoma is a midline tumor that behave locally aggressive in nature at the spheno–occipital synchondrosis [8]. It was first proposed by Muller that this tumor is origin from remnants of notochord and later supported by Ribbert in 1894 after reviewing 5 cases [9]. Clival chordomas was taken into concern as a malignant tumor after first mortality reported in 1903 [9].

Patient who suffer from clival chordomas were usually presented with intractable headache with neurological deficit, mainly of the cranial nerve neuropathy [10]. Among the cranial nerve, abducent nerve is more commonly affected where patient complain of diplopia. Other rare symptoms and sign that have been described were intracranial hemorrhage, epistaxis and more rare presentation with hearing loss, vertigo and facial paralysis depends on the extension of the tumor [10, 11].

Radiological investigation plays important role managing clival chordomas. In a contrast CT scan, a chordoma appears moderated to marked enhanced extensile, destructive lytic lesion at clivus. It is hypointense T1 weighed image and hyperintense T2 weighted, with heterogeneous enhancement in MRI scan. MRI which is better in scanning soft tissue helps to identify the margin of tumor from optic chiasma, cavernous sinus and internal carotid artery, which were the important sugical landmark for clivus.

Besides chordomas, the differential diagnosis of non-neoplastic clival tumor are fibrous dysplasia, neurenteric cyst and ecchordosis physaliphora. The common neoplastic tumor that arise from clivus are meningioma and chordosarcoma [12].

The narrow window of the clivus gives a challenging operative field for a neurosurgeon. Adding to this, there are no clear protocol in managing clival chordomas [8]. Since it is a rare occurrence, clival chordoma is mostly reported in case series with limited literature providing little evidence in treating clival chordomas [8]. However, it is known that the prognosis of 5 years survival where clival chordomas underwent treatment were between 50 and 85%, with the best prognosis achieved when complete resection was performed [11].

In the early twentieth century, open approach with transoral and transpalatal approaches are most preferred method to access the clivus [9, 13], with certainly giving morbidity in cranial nerve injury as the surgeons were dissecting around these structures to reach the midline. This is because the lateral boundaries were bounded by the cranial nerves and vascular system [14, 15]. The recurrence rates were also recorded high in open approaches of clival chordomas surgery [16]. One of our patients had an open craniotomy debulking of tumor done initially which complicated with cranial nerve I, II, III, IV and VI injury and yet, the tumor was not completely resected with recurrence (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and Tables 1, 2).

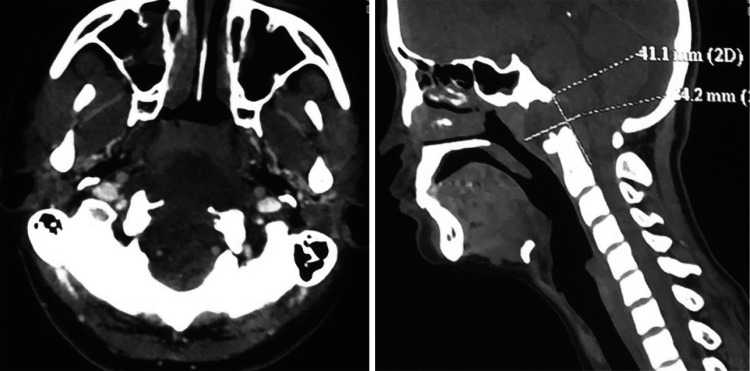

Fig. 1.

CT scan describe appearance of chordoma as enhanced extensile, destructive lytic lesion at clivus

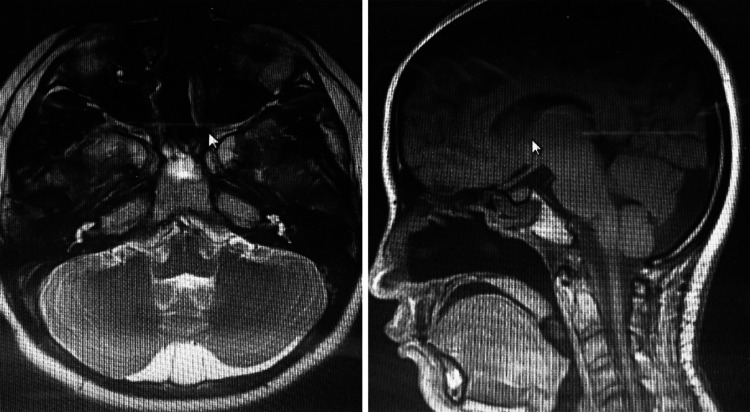

Fig. 2.

Clival chordoma appears hypointense in T1 (a) and hyperintense in T2 (b) in MRI scan

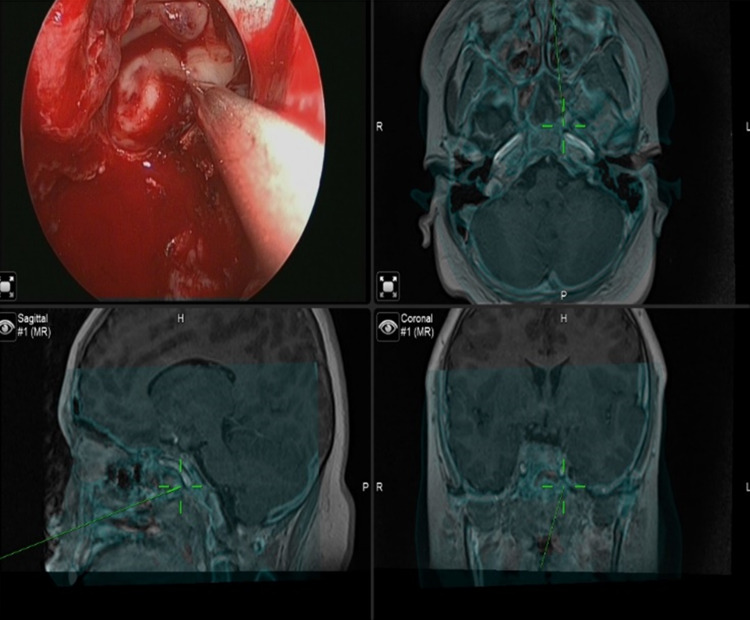

Fig. 3.

MRI scan shows a complete resection of a clival chordoma

Fig. 4.

endoscopic endonasal approach using IGS

Table 1.

summary of the 4 cases with the presentation

| Case | Age, year | Gender | Pre-operative symptoms and signs | Tumor size | Tumor extension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | M | Headache, right eye squint with diplopia | 3.5 × 6.0 cm | Clivus, right cavernous sinus |

| 2 | 13 | M | Headache, diplopia with right abducent nerve palsy | 3.0 × 3.2 × 3.7 cm | Clivus, sella and anterior aspect of pons |

| 3 | 15 | F | Headache, nasal blockage, nasopharyngeal fullness | 4.1 × 3.4 cm | Clivus, C-2 level |

| 4 | 20 | F | Recurrent clival chordoma since age of 5, | 7.2 × 7.8 × 6.0 cm | Clivus, soft palate, nasal cavity, orbital ape × |

| 5 | 57 | M | Eye squint, headache. Diplopia, blurring of vision, reduced sensation of right face, left eye convergence | 4.2 × 2.4 × 2.8 cm | Clivus, Carvenous sinus |

Table 2.

Summary of cases with the intra- and post-operative event

| Case | Intraoperative event | Postoperative event | Lumbar drain | Total hospital stays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | Inserted | 9 days |

| 2 | – | Syndrome of inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone | Inserted | 23 days |

| 3 | – | – | Inserted | 11 days |

| 4 | – | – | Not inserted | 18 days |

| 5 | Residual tumour near the internal carotid artery | Patient require revision of surgery | Inserted | 22 days |

The development of technology in endoscopy has favor the surgeon accessing to the central part of the skull base. The direct approach to the clivus from the anterior direction giving the benefit of avoiding the neurovascular structure at the lateral boundaries, having the least invasive and morbidity to the patient. Endoscopic endonasal approach is gaining more popularity due to its ability to provide a wider angle and closer operative view [17]. The innovation and modification of endoscopic endonasal method could even allow 2 nostrils to be access by 3 to 4 hands with their instrument [12]. Complete or near complete of clival chordomas could be achieve with the advancement of the method.

Neuronavigation is mandatory to assist the surgeon in confirming the vital structures landmark along the dissection [11]. Under fusion of MRI and CT scan, a clear understanding of the operative field can be gained by the combination of bony structure and the surrounding soft tissue which is best reviewed by CT and MRI scan respectively [16]. Although endoscopic endonasal method has been described as a better technique, safer surgery could be synergistically performed with neuronaviagation. A virtual reality imagine was carried out by Shou-Sen Wang at el. showing an average shortest distance between the bilateral boundaries is at 18.0 ± 1.8 mm. with the help of neuronaviagtion, drilling of the superior and middle clivus is allowed to extend 9 mm laterally to avoid any injury to internal carotid artery [15]. Other complication of this method had also been reported such as, persistent CSF leakage, hypopituitarism, temporary diabetes insipidus and meningitis [11].

The gross total resection rate via endoscopic transnasal method had been recorded by Alessandro Paluzzi et al. in 83% of the new chordomas and in 44% of the recurrent cases [18]. To complete the treatment after gross total or near total resection of chordomas done with endoscopic transnasal surgery, patient is arranged for radio chemotherapy to minimise the possibility of recurrence.

The benefit of endoscopic endonasal method in clival chordomas surgery is not just limited intraoperatively. As the procedure could approach the midline of skull base via nasal cavity, there is no external scar and patient will not suffer from any external wound breakdown. If patients does not have any endocrine complication or CSF leak postoperatively, the hospital stay could be minimised. Therefore, the risk of hospital acquired infection could be reduced or avoided. Our patients have an average of 9–22 of hospital stays and none of them acquired any nosocomial infection.

In our experience in managing 5 patients with clival chordoma, endoscopic endosnasal method of resection was performed to all 5 of them. However, with 5 of them, 1 patient went through revision of resection via endoscopic method during the same admission with one week apart. Our patient was covered with prophylactic antibiotics before the operation to prevent meningitis. A proper reconstruction of the skull base with the assist of the lumbar drain prevent the CSF leak.

Yearly neuro-radiological imaging was done for patient after the completion of the treatment as the recurrence rate of clival chordoma was recorded high [19]. Among the 5 of our patient, 1 had been under our follow up for more than 3 years with a yearly repeated MRI scan shows no residual tumor and patient has a full restoration of daily activity.

Conclusion

Before the development of endoscopic endonasal method, resection of clival chordoma is purely done by neurosurgical team via open approach. It has recorded with high incidence of recurrent rate and was having high morbidity. With the achievement of endoscopic endonasal surgery, the quality of life for a patient with clival chordoma can be maintained. The limitation of this case series is the limited sample size due to the rarity of this disease. However, further innovation for this method shall be created to improve and maximal the resection of clival chordoma in future.

Author Contributions

DR. CHIEN YING VINCENT NGU main author (data collection, writing this paper) DR. ING PING TANG co-author (neurosurgeon, designed of surgery, Writing manuscript). DR. BOON HAN KEVIN NG co-author (data review, writing this paper). DR. ALBERT SII HIENG WONG co-author (neurosurgeon, designed of surgery). DR. DONALD NGIAN SAN LIEW co-author (neurosurgeon, designed of surgery.

Funding

There is no funding declared in this case series.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Khawaja AM, Venkatraman A, Mirza M. Clival chordoma: case report and review of recent developments in surgical and adjuvant treatments. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:670–675. doi: 10.12659/PJR.902008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youssef C, Aoun SG, Moreno JR, Bagley CA. Recent advances in understanding and managing chordomas. Res. 2016;5:2902. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9499.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontes R, O'Toole JE. Chordoma of the thoracic spine in an 89-year-old. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl 4):S428–S32. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun X, Hornicek F, Schwab JH. Chordoma: an update on the pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2015;8(4):344–352. doi: 10.1007/s12178-015-9311-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catala M. Embryology of the sphenoid bone. J Neuroradiol. 2003;30:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KH. Intradural clival chordoma: a case report. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2014;2(2):76–80. doi: 10.14791/btrt.2014.2.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walcott BPNB, Mohyeldin A, Coumans JV, Kahle KT, Ferreira MJ. Chordoma: current concepts, management, and future directions. LANCET Oncol. 2012;13(2):69–76. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yousaf J, Afshari FT, Ahmed SK, Chavda SV, Sanghera P, Paluzzi A. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for clival chordomas—a single institution experience and short term outcomes. Br J Neurosurg. 2019 doi: 10.1080/02688697.2019.1567683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahyouni R, Goshtasbi K, Mahmoodi A, Chen JW. A historical recount of chordoma. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28(4):422–428. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.spine17668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell RG, Prevedello DM, Ditzel Filho L, Otto BA, Carrau RL. Contemporary management of clival chordomas. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23(2):153–161. doi: 10.1097/moo.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshammari J, Monnier P, Daniel RT, Sandu K. Clival chordoma with an atypical presentation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6(1):410. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jho HD. The expanding role of endoscopy in skull-base surgery. Indic Instrum Clin Neurosurg. 2001;48:287–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krespi YP, Har-El G. Surgery of the clivus and anterior cervical spine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114(1):73–78. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860130077019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rai R, Iwanaga J, Shokouhi G, Loukas M, Mortazavi M, Oskouian R, et al. A comprehensive review of the clivus: anatomy, embryology, variants, pathology, and surgical approaches. Child's Nervous Syst. 2018;34:1451–1458. doi: 10.1007/s00381-018-3875-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S-S, Li J-F, Zhang S-M, Jing J-J, Xue L. A virtual reality model of the clivus and surgical simulation via transoral or transnasal route. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(10):3270–3279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garzaro M, Zenga F, Raimondo L, Pacca P, Pennacchietti V, Riva G, et al. Three-dimensional endoscopy in transnasal transsphenoidal approach to clival chordomas. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1814–E1819. doi: 10.1002/hed.24324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garzaro M, Pecorari G, Riva G, Pennacchietti V, Pacca P, Raimondo L, et al. Nasal functions in three-dimensional endoscopic skull base surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2019;128:208–214. doi: 10.1177/0003489418816723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paluzzi A, Gardner P, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Snyderman C. The expanding role of endoscopic skull base surgery. Br J Neurosurg. 2012;26(5):649–661. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.673649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samii A, Gerganov V, Herold C, Hayashi N, Naka T, Javad Mirzayan M, et al. Chordomas of the skull base: surgical management and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107:319–324. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/08/0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]