Abstract

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic, autoimmune disease of hair loss, which can significantly affect the emotional and psychological well-being of patients. A systematic literature review was conducted to better understand the burden of AA from the patient perspective.

Methods

Embase, MEDLINE and Cochrane databases were searched for published studies (2008–2018) reporting on assessments of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients with AA. Qualitative, and quantitative data were collected.

Results

The review included 37 studies encompassing a range of clinical outcome assessment (COA) tools. None of the COA tools were specific for AA, and only one study used the Hairdex scale, which was designed to evaluate HRQoL in patients with disorders of the hair and scalp. All studies reported substantial impact on HRQoL due to AA, both overall and in domains related to personality (i.e. temperament and character), emotions and social functioning. Acute stress was also noted, and several studies identified lack of emotional awareness (alexithymia) in 23–50% of the patients with AA.

Conclusions

Although it is well-established that patients with AA experience anxiety and depression, they also experience a decrease in HRQoL in many other areas, including personality, emotions, behaviors and social functioning, and these changes may be accompanied by acute stress and alexithymia. There is a need to achieve consensus on a core set of measures for AA and to develop and validate AA-specific measurement tools for use in future studies, to attain a clearer understanding of the impact of AA on patients.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO registration number; CRD42019118646.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00512-0.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Health-related quality of life, Psychosocial burden

Plain Language Summary

Alopecia areata (AA) is a disease in which a person’s immune system attacks their hair follicles, from which hairs grow, causing hair loss. Studies have shown that people with AA may have a lower quality of life, and studies have reported higher rates of depression and anxiety in people with AA than in people without AA. Study design: We reviewed published studies to better understand how AA affected people socially, emotionally and in their day-to-day functioning. We also looked at how healthcare providers measured these social, emotional and day-to-day effects on people with AA. Our review included 37 published studies that used several evaluation tools to measure the impacts of AA. These included a variety of questionnaires that were answered by people with AA. Results: The studies reported that AA negatively affected the personality, emotions, behaviors and/or social functioning of many people with AA. However, none of the evaluation tools that were used in those studies were specific for AA, and most of the evaluation tools did not include questions about the hair or scalp. Conclusions: We recommend that a group of people familiar with AA (practitioners, researchers and patients) work together to develop an evaluation tool that is designed specifically for people with AA. This evaluation tool can then be used in future studies to better understand how AA affects people socially, emotionally and in their day-to-day functioning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00512-0.

Key Summary Points

| Alopecia areata (AA) can have a significant effect on the domains of personality (i.e. temperament and character), emotions, behavior and social functioning. |

| Multiple clinical outcome assessment tools have been used to measure health-related quality of life in patients with AA, and many have a limited ability to measure concepts that are meaningful to patients with AA. |

| To better understand the effect of AA on patients, it is necessary to develop and validate AA-specific measurement tools for use in future studies. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and plain language summary, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.14125628.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease with a global lifetime incidence of approximately 2% [1]. Clinical severity ranges from small patches of hair loss to complete scalp hair loss (alopecia totalis [AT]) or complete loss of scalp and body hair (alopecia universalis [AU]) [2].

Although AA is not associated with increased mortality, evidence from clinical outcome assessment (COA) tools demonstrates that AA can have a substantial impact on the psychological well-being of patients [1]. The incidence of major depression in patients with AA has been reported as 8.8% compared with 1.3–1.5% in the general population, and generalized anxiety disorder has been reported in 18.2% compared with 2.5%, respectively [1]. Although psychiatric diagnoses preceded AA in approximately half the patients, in other patients AA appears to contribute to the development of depression and anxiety [1, 3].

The objective of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to gain insight into the burden of AA from the patient perspective, by reviewing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes, including well-established and less well-established outcomes, such as social, emotional and functional impacts.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The protocol for the SLR was registered with the National Institute for Health Research-funded International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number CRD42019118646) [4]. This SLR was conducted using a standardized approach, following Cochrane dual-reviewer methodology. The protocol followed the PRISMA-P guidelines, which defined all processes and methodologies [5].

Eligibility Criteria

Observational studies, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs were included in the review if they reported the results of COAs of disease burden from the patient perspective. Studies could include children, adolescents and/or adults with any severity of AA. Reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, notes, comments, editorials, letters and opinions were excluded, as were studies of other forms of alopecia.

Our preregistered protocol also included studies evaluating the economic impact of AA, as well as anxiety and depression in AA. However, due to the scarcity of literature on the economic aspects of AA and the recent publication of a meta-analysis of anxiety and depression in AA [3], this report focuses on the social, emotional and functional impacts of AA on patients and does not include economic impacts of depression and anxiety.

This report is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Sources

The SLR was conducted in accordance with guidance from health technology assessment agencies, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Embase® and MEDLINE® were searched via Ovid®, and the Cochrane Central Trials Register and Database of Systematic Reviews were searched for articles published in English between 1 January 2008, and 3 December 2018. PubMed was searched for articles published between 1 January 2016 and 22 November 2018, and conference abstracts from relevant dermatology congresses were searched for the period between 1 January 2017 and 3 December 2018.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The detailed search strategies are provided in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Tables S1–S5. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers, and the full text of all selected articles was then assessed by two reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Study Outcomes

Study design, patient population and study outcomes data were extracted from all selected publications. Specific elements of interest included sample size, patient demographics, severity of hair loss, COA tool and COA score. The primary outcome measure was the impact of AA on HRQoL. When available, data were stratified by severity of AA (as defined by each publication).

Assessment of Bias

All included articles were assessed for quality and allocated a risk of bias. Observational studies and non-RCTs were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and RCTs were evaluated using the NICE Single Technology Appraisal. Publications were classified as low, medium or high risk of bias based on a percentage score: ≥ 75% was considered low risk of bias (i.e. high quality); ≥ 50 to 74%, medium risk; and ≤ 49%, high risk (i.e. low quality). Conference abstracts were not assessed for bias and were included only if they supported fully published studies.

Results

Search Results

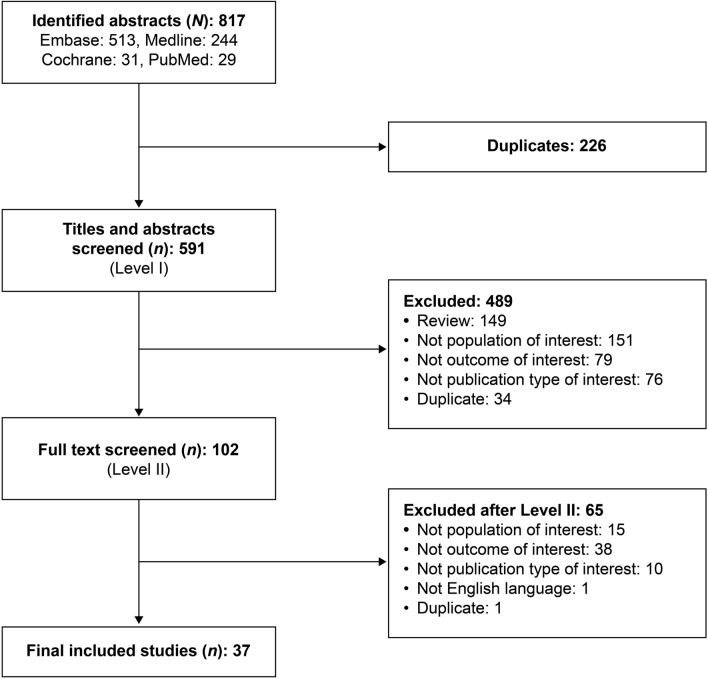

The database searches identified 817 publications, of which 226 were duplicates (Fig. 1). After screening, 37 publications [6–42] met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. See ESM Table S6 for additional details of the publications.

Fig. 1.

Results of the database search

All 37 published studies were observational, and all publications were full-length articles; no congress abstracts qualified for inclusion. In the risk of bias assessment, 23 (62%) publications were rated as having a low risk and 14 (38%) were rated as having a medium risk of bias (ESM Table S6).

COA Tools

Across the 37 studies, 12 COA tools were used (ESM Fig. S1). The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [6, 7, 9, 18, 20, 28, 41, 42] was most frequently used, followed by the 16-, 17- or 29-item Skindex tools (Skindex 16-, 17- or 29) [17, 20, 26, 29, 31, 32, 39] and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) 20/26 [14, 21, 27, 33, 38, 39].

Dermatology Life Quality Index

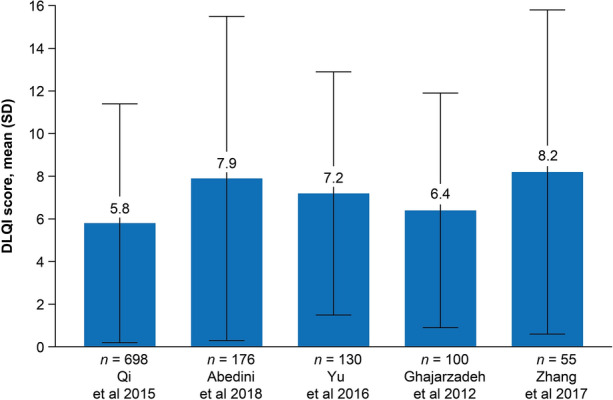

The DLQI consists of ten questions on symptoms and impact on HRQoL related to the skin [43]. The total score (range 0–30) is the sum of each question score, with 0–5 indicating no or small effect; 6–10, a moderate effect; 11–20, a very large effect; and 20–30, an extremely large effect [6, 43]. In the eight studies that reported DLQI results, patients were aged ≥ 16 years [6, 7, 9, 18, 20, 28, 41, 42]. Five studies provided total mean DLQI scores, which were generally moderate, ranging from 5.8 to 8.2 [6, 18, 28, 41, 42] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total mean (SD) DLQI scores among patients with AA. Score range, 0–30; higher score suggests greater impairment in health-related quality of life. DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, SD standard deviation

Several studies reported that in patients with AA, DLQI scores increased with greater disease severity [6, 7, 9, 20, 28]. Qi et al. reported significantly higher mean DLQI scores (± standard deviation [SD]) in patients with AT/AU compared with those with patchy AA (8.7 ± 6.2 vs. 5.2 ± 5.3, respectively; p < 0.001) [28]. Abedini et al. noted mean DLQI scores (± SD) of low to moderate impact (5.4 ± 6.8) for patients with mild AA (< 25% scalp hair loss) and of large impact (10.7 ± 7.5) for patients with severe AA (AT, AU, ophiasis; p < 0.001) [6]. Al-Mutairi et al. reported that adult patients with severe AA (AT, AU, and those with > 10 patches on the body and > 40% of the scalp affected) had a mean DLQI score of 13.5 compared with 1.2 in age- and sex-matched controls [9]. Two studies reported that AA lasting ≥ 12 months and occurring at a younger age (< 30 years or < 40 years) were significantly associated with higher DLQI scores [28, 42]; however, one study found similar DLQI scores regardless of disease duration [18]. One study reported that recurrence of AA and scalp symptoms were both significantly associated with higher DLQI scores [28].

Short Form-36 Tool

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) tool is a 36-item survey that assesses four scales (or subscales) of physical health, namely physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health (role-physical), bodily pain and general health, and four scales of mental health, namely vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional effects (role-emotional) and mental health [44]. The original scoring method had a score of 0–100 based on summation, with higher scores suggesting better HRQoL [44]. More recently, normative scoring has been developed, with standardized mean scores and SD; normative scores for the general US population are provided as a footnote on Table 1 [44, 45].

Table 1.

Short Form-36 outcomes in patients with alopecia areata

| AA study population | N | Subscale scores (mean ± SD) | Total score (mean ± SD) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental components | Physical components | ||||

| Adults, age ≥ 18 years; 62% were women | 37 | Vitality: 61.8 ± 22.5 | Bodily pain: 74.3 ± 21.9 | N/A | de Hollanda et al. 2014 [13] |

| Mental health: 63.9 ± 22.2a | General health: 77.9 ± 16.4 | ||||

| Role-emotional: 70.3 ± 39.1a | Physical functioning: 87.5 ± 13.7 | ||||

| Social functioning: 70.6 ± 26.6a | Role-physical: 88.5 ± 28.6 | ||||

| Adults, age 18–60 years; 52% were women | 50 | Vitality: 62.4 ± 21.2a | Bodily pain: 95.4 ± 12.5 | 69.0 ± 13.1; adults with AA had lower HRQoL vs. healthy individuals | Masmoudi et al. 2013 [22] |

| Mental health: 63.6 ± 16.6a | General health: 58.2 ± 17.1a | ||||

| Role-emotional: 33.3 ± 36.3a | Physical functioning: 93.1 ± 12.5 | ||||

| Social functioning: 54.6 ± 33.8a | Role-physical: 95.5 ± 10.9 | ||||

| Adults age 18–70 years: n = 6 with AT and n = 5 with AU; 76% were women | 21 | Vitality: 48.5 ± 7.6 | Bodily pain: 49.6 ± 11.5 | N/A | Willemsen et al. 2011 [39] |

| Mental health: 41.2 ± 8.0 | General health: 44.5 ± 10.1 | ||||

| Role-emotional: 39.4 ± 10.7 | Physical functioning: 51.1 ± 6.6 | ||||

| Social functioning: 45.7 ± 9.8 | Role-physical: 47.8 ± 6.6 | ||||

| Age > 16 years (mean: 37 ± 14 years): 32% with severe AA and 23% with moderate AA; 73% were women | 60 | Vitality: 59.3 ± 12.4 | Bodily pain: 82.3 ± 26.3 | N/A | Jankovic et al. 2016 [20] |

| Mental health: 50.1 ± 6.8 | General health: 61.1 ± 20.5 | ||||

| Role-emotional: 65.6 ± 42.9 | Physical functioning: 89.3 ± 15.8 | ||||

| Social functioning: 70.8 ± 27.0 | Role-physical: 73.1 ± 37.0 | ||||

| Mean age: 23 years: 11% had > 50% scalp involvement; 69% were male | 100 | N/A | N/A | 68.0 ± 15.1 | Ghajarzadeh et al. 2012 [18] |

Higher scores indicate less impairment in HRQoL

Normative scores for the general US population: 84.2 for physical functioning, 81.0 for role limitations due to physical health, 75.2 for bodily pain, 72.0 for general health perceptions, 60.9 for vitality, 83.3 for social functioning, 81.3 for role limitations due to emotional problems and 74.7 for mental health [45]

AA Alopecia areata, HRQoL health-related quality of life, N/A not available, SD standard deviation

aSignificantly lower than controls

The SF-36 tool was used to assess HRQoL related to AA in five studies (Table 1) [13, 18, 20, 22, 39]. Across the studies, subscale scores for the mental components showed greater HRQoL impairment than the physical components [13, 20, 22, 39]. Since these studies were not conducted in the USA, a direct comparison with the normative US scores is of limited value. Masmoudi et al. determined that poorer mental health and social function were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with more severe disease (≥ 50% hair loss) [22]. However, two other studies identified no significant association between overall [18] or individual [20] SF-36 subscale scores and disease severity. Jankovic et al. found no significant association between individual subscale scores and disease duration [20].

Skindex-16/-17/-29 Tools

Seven studies reported results using the 16-, 17- or 29-item Skindex tools; six studies included adults [17, 26, 29, 31, 32, 39] and one included adults and children aged > 16 years [20]. The Skindex is a dermatology-specific survey that measures HRQoL factors related to skin disease [46–48]. The Skindex-16 and -29 tools measure three scales (or subscales): symptoms, emotions and functioning [20, 47]. The Skindex-29 tool has 29 questions referring to the past 4 weeks that ask “how often were you bothered by…?” [20, 48]. The five response options range from “never” to “always.” The Skindex-16 tool has 16 questions referring to the last 7 days, with seven possible responses ranging from “never bothered” to “always bothered” [47]. Each response is converted to a linear scale from 0 (no effect) to 100 (maximum effect) [47, 49]. The scale score is the average of the responses to the items within it [49]. The total score and scale scores are also converted to a linear 0–100 scale [29]. In the studies, mean subscale scores for Skindex-16 and -29 ranged from 9.3 to 25.4 for symptoms [17, 20, 29, 32], from 36.2 to 82.1 for emotions [17, 20, 29, 32] and from 16.7 to 52.2 for functioning [17, 20, 29, 32]. Two studies reported total mean scores of 39.8 and 58.6, and one reported a total median score of 26.4 [17, 29, 32].

Nijsten et al. used mixture analyses to classify Skindex-29 mean scores as indicative of having very little, mild, moderate, severe or extremely severe (symptoms subscale only) impairment [26]. Of the 46 patients in this study, the proportion with severe impairment was 17% for the total score (37–100 cutoff), 22% for emotions (50–100 cutoff), 22% for functioning (33–100 cutoff) and 7% for symptoms (26–49 cutoff) [26]. Jankovic et al. identified a correlation between overall Skindex-29 score and the percentage of scalp hair loss [20]. Patients with severe (≥ 76% hair loss) AA had a significantly worse mean symptom score (17.7) than patients with moderate (26–75% hair loss) AA (score 6.6; p = 0.04), and a significantly worse mean social function score (32.2) than patients with mild (≤ 25% hair loss) AA (score 16.7; p = 0.025) [20].

The Skindex-17 tool has 17 questions answered on a 3-point scale (never [0], rarely/sometimes [1], often/always [2]), with five of these questions relating to symptoms and 12 relating to psychosocial effect [50]. The symptom scale ranges from 0 to 10, with 0–4 indicating few symptoms and 5–10 indicating many symptoms. The psychosocial scale ranges from 0 to 24: 0–4 denotes little impairment, 5–9 indicates moderate impairment and 10–24 signifies a high degree of impairment [46]. Willemsen et al. reported the Skindex-17 mean symptom and psychosocial scores to be 2.3 and 8.9, respectively, for 21 adult patients [39]. Sampogna et al. used the Skindex-17 to calculate an adjusted psychosocial score, taking into account the Physician Global Assessment, gender and age [31]. The study transformed the Skindex scores to a linear 0–100 scale, then categorized the adjusted mean psychosocial score according to symptom score. Symptom scores of 0 (absent), 1–49 (mild) and 50–100 (severe) correlated with psychosocial scores of 14.2, 31.2 and 87.5, respectively, suggesting that the relationship between symptoms and psychosocial effect becomes stronger with more severe symptoms.

Other Concepts Associated with HRQoL

Personality and Emotional Distress

Using COA tools, eight studies assessed personality (i.e. temperament and character) and emotional distress (Table 1) [10, 16, 21, 24, 35, 36, 39, 41]. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI), used in three studies [10, 16, 35], is a self-report tool designed to provide a comprehensive picture of an individual’s personality [51, 52]. It assesses four dimensions of temperament and three dimensions of character (see Table 2 footnote) [51].

Table 2.

Personality and emotions outcomes in patients with alopecia areata

| AA study population | N | COA tool | Score (mean ± SD)a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults, age 18–65 years: 96% with < 25% hair loss; no AT/AU; 66% were men | 73 | TCI | Novelty seekingb 18.6 ± 3.4; Harm avoidance 17.7 ± 4.8 | Annagur et al. 2013 [10] |

| Reward dependenceb 13.6 ± 3.0; Persistence 4.9 ± 1.5 | ||||

| Self-directedness 27.5 ± 5.6; Cooperativeness 27.4 ± 5.0 | ||||

| Self-transcendenceb 17.3 ± 4.4 | ||||

| SCL-90-R GSI | 0.8 ± 0.5c | |||

| Adults, age 18–60 years: first onset AA; 67% were men | 42 | TCI | Novelty seeking 18.9 ± 5.0; Harm avoidance 16.8 ± 6.7 | Erfan et al. 2014 [16] |

| Reward dependence 13.8 ± 3.1; Persistence 4.8 ± 2.0 | ||||

| Self-directedness 28.0 ± 7.2; Cooperativeness 29.0 ± 6.3 | ||||

| Self-transcendence 18.7 ± 5.8 | ||||

| (Scores did not differ significantly from controls) | ||||

| Age > 12 years: 38% with ≤ 50% hair loss; 62% with > 50% hair loss; 67% were women | 24 | TCI-125 Persian version | Novelty seeking 7.6 ± 3.0; Harm avoidanced 12.0 ± 3.6 | Talaei et al. 2017 [35] |

| Reward dependenced 9.8 ± 1.9; Persistence 2.3 ± 2.0 | ||||

| Self-directedness 13.0 ± 6.6; Cooperativeness 18.9 ± 3.9 | ||||

| Self-transcendence 7.5 ± 2.5 | ||||

| SCL-90-R GSI | 0.7 ± 0.6e | |||

| Adults, age > 18 years: 12% with AT/AU; 50% were women | 168 | SCL-90-R GSI | 1.4 ± 0.4c | Tan et al. 2015 [36] |

| Adults, age 18–70 years: 33% with patchy AA, 14% ophiasis, 29% AT, 24% AU; 76% were women | 21 | SCL-90 Total | 145 ± 40 | Willemsen et al. 2011 [39] |

| Age, gender, severity not reported | 30 | MBSRQ | Appearance orientation 3.7 ± 0.6 | Kuty-Pachecka and Stefanksa 2014 [21] |

| Body area satisfaction 3.1 ± 0.8 (Controls: 3.4 ± 0.7 and 3.4 ± 0.6). Suggests patients with AA pay more attention to appearance and are less satisfied with appearance than controls | ||||

| Adults, age 19–68 years: 21% with AT/AU; 69% were women | 42 | EQ-i | Total scoreb 96.1 ± 16.6 (Controls 100.7 ± 4.7). Suggests patients wiith AA have difficulty managing emotions and stress | Monselise et al. 2013 [24] |

| Adults, age > 18 years: 59% women; severity not reported | 130 | BIPQ | Overall score 40.2 ± 9.1 | Yu et al. 2016 [41] |

| Highest scores: Concern: 8.4 ± 2.2; Consequences: 5.7 ± 2.9; Emotional response 5.7 ± 2.9 | ||||

| Lowest scores: Identity 3.1 ± 2.4; Treatment control 3.4 ± 2.6 |

AT alopecia totalis, AU alopecia universalis, BIPQ Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire, COA clinical outcome assessment, EQ-i Emotional Quotient Inventory, GSI Global Severity Index, MBSRQ Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire, SCL-90 Symptom Checklist 90, TCI Temperament and Character Inventory

aScoring for each tool: TCI: 240 true/false questions. TCI assesses four dimensions of temperament: harm avoidance, novelty seeking (i.e. engaging in frequent exploratory behavior), reward dependence (i.e. having a strong response to conditioned reward signals) and persistence; and three dimensions of character: self-directedness, cooperativeness and self-transcendence (i.e. thinking of oneself as an integral part of the universe) [51]; TCI-125 Persian version: 125 true/false questions [59]; SCL-90-R GSI: SCL-90-R has 90 questions and has nine subscales: somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism [35]. The GSI is calculated from it; a score > 1 suggests severe symptoms of distress [53]; SCL-90 Total: 90 questions on intensity of symptoms, answered on a 5-point scale, 0 (none) to 4 (extremely) [10]; MBSRQ: 69 items; 5-point response from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree) [60]; EQ-i: 133 items; 5-point response from 1 (very seldom or not true of me) to 5 (very often true of me or true of me). Scores are standardized based on a mean ± SD of 100 ± 15; BIPQ: measures illness perception, specifically consequences, timeline, personal control, treatment control, identity, concern, coherence, emotional response. Each is measured on an 11-point Likert scale. Higher score indicates a more negative perception of the illness

bScores were significantly lower than controls

cScore was significantly higher than controls

dLarge effect size vs. controls (Cohen’s d)

eScore did not differ significantly from controls

Annagur et al. found that scores for novelty seeking, reward dependence and self-transcendence were significantly lower than those of the controls [10] (Table 2). In contrast, Talaei et al. found that patients with AA (aged > 12 years) scored higher in the categories of reward dependence and harm avoidance than the controls (large Cohen’s d effect size) [35].

The revised Hopkins Symptom Distress Checklist-90 (SCL-90-R) is a 90-item self-report scale of intensity of psychological symptoms over the past 7 days, with scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) [35]. Scores for each of nine subscales are used to calculate the Global Severity Index (GSI); GSI > 1 suggests severe symptoms of distress (Table 2) [53]. GSI scores of 0.7–1.4 for the SCL-90 were reported in three studies [10, 35, 36]. Talaei et al. found that patients with at least one relapse of AA scored higher for psychiatric symptoms than patients without a relapse [35]. Tan et al. reported that patients with AA for ≥ 12 months had significantly higher GSI scores (p < 0.01) and higher scores in all subscales (p < 0.05) except obsessive–compulsive than patients with a shorter disease duration [36].

Social Functioning

Twelve studies of pediatric (aged ≥ 13 years) and adult patients reported outcomes for social functioning using a concept-specific COA tool (Social Phobia Inventory [SPIN] [25]) or subscales from general HRQoL COA tools [10, 13, 17, 19, 20, 22, 29, 32, 35, 36, 39] (Table 3). One study used Hairdex, a tool designed to measure HRQoL in patients with disorders of the hair and scalp [19]. Two studies evaluated social functioning through interviews or questionnaires [11, 37]. All studies reported substantial effects of AA on social functioning.

Table 3.

Social function outcomes in patients with alopecia areata

| AA study population | N | COA tool | Score (mean ± SD)a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults, children age ≥ 13 years with alopecia; most had AA (83%); 59% with AA had AT/AU; 97% were female | 338 | SPIN | 47.5% of patients with score ≥ 19 (clinically significant symptoms of social anxiety) | Montgomery et al. 2017 [25] |

| Adults, children age > 16 years: 32% with severe AA; 73% were female | 60 | SF-36 | Social functioning 70.8 ± 27.0 | Jankovic et al. 2016 [20] |

| Skindex-29 | Social functioning 22.0 ± 22.6 | |||

| Adults, age 18–60 years: 80% with < 50% hair loss; 52% were women | 50 | SF-36 | Social functioning 54.6 ± 33.8 (Controls: 82.2 ± 18.6; p < 0.001) | Masmoudi et al. 2013 [22] |

| Adults, age ≥ 18 years: 62% with < 50% hair loss; 62% were women | 37 | SF-36b | Social functioning 70.6 ± 26.6 (Controls: 86.5 ± 20.5; p < 0.001) | de Hollanda et al. 2014 [13] |

| Adults, age ≥ 18 years | 17 | Skindex-16 | Social functioning 33.1 ± 31.4 | Essa et al. 2018 [17] |

| Age and severity not reported; 100% were women | 23 | Skindex-16 | Functionb 52.2 ± 6.3 | Reid et al. 2012 [29] |

| Adults, age > 18 years: Severity and gender not reported | 11 | Skindex-29 | Function 16.7 ± 16.0 | Sanclemente et al. 2017 [32] |

| Adults, age 18–70 years: 33% with patchy AA, 14% ophiasis, 29% AT, 24% AU; 76% were women | 21 | Skindex-17 | Psychosocial subscale: 8.9 ± 6.7 (moderate impairment) | Willemsen et al. 2011 [39] |

| Adults, age 18–65 years: 96% with < 25% hair loss; none with AT/AU; 34% were women | 73 | SCL-90 | Phobic anxiety 0.4 ± 0.5 (Controls: 0.4 ± 0.6) | Annagur et al. 2013 [10] |

| Age > 12 years: 38% with < 50% hair loss; 62% with > 50% hair loss; 67% were women | 24 | SCL-90 | Phobic anxiety 2.8 ± 4.0 (Controls: 1.5 ± 2.7; Cohen’s d 0.37) | Talaei et al. 2017 [35] |

| Adults, age > 18 years: 12% with AT/AU; 50% were women | 168 | SCL-90 | Phobic anxiety 1.3 ± 0.4 (Controls: 1.1 ± 0.1; p < 0.05) | Tan et al. 2015 [36] |

| Adults, age > 18 years: 45% were women | 56 | Hairdex scale | Total 57.0 ± 27.0 | Gonul et al. 2018 [19] |

| Symptoms 6.7 ± 5.0 | ||||

| Functioning 4.0 ± 3.4 | ||||

| Emotions 24.4 ± 17.0 | ||||

| Confidence 17.4 ± 7.3 | ||||

| Stigmatization 4.7 ± 6.0 |

QoL Quality of life, SCL-90 Symptom Checklist 90,SF-36 Short Form 36, Skindex -16, 17, 29 16-, 17-, or 29-item Skindex, SPIN Social Phobia Inventory

aTotal possible scores: SPIN: 17 items; score ≥ 19 indicates symptoms of social anxiety; SF-36: Social functioning score range standardized to 0–100 (higher score = better QoL); Skindex-29 and Skindex-16: 0–100 (lower score = better QoL); Skindex-17: 0 (little impairment) to 24 (high impairment); SCL-90: 90 items, answered on 5-point scale, from 0 “none” to 4 “extremely”; Hairdex: 48 items, all hair-specific; assesses five categories: symptoms, functioning, emotions, confidence, and stigmatization. Patients score questions from 0 to 4 according to frequency of occurrence. Higher scores on all but confidence indicate a lower level of HRQoL

bMean ± standard error of the mean

Using the SF-36, Masmoudi et al. identified a significant association (p < 0.05) between AA severity and social functioning: patients with hair loss of 51–75% had significantly lower scores than patients with < 25% hair loss [22]. Jankovic et al. found a significant correlation between the severity of AA and social functioning scores on the Skindex-29 [20].

Stress

Eleven studies reported stress as a baseline characteristic or evaluated stress using qualitative interviewing techniques [6–8, 12, 15, 23, 30, 34, 36, 37, 40]. Abedini et al. reported that in 176 patients aged ≥ 16 years, acute stress was present in the previous 6 months in 60% with severe AA and 57% with mild AA [6]. Tan et al. reported that stress was present for 76% of 168 adult patients, and Abideen et al. reported stress in 47% of 60 adult patients [7, 36]. Cetin et al. administered the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) and identified psychological distress unrelated to disease severity in 46% of 24 children and adults with AA [12]. Matzer et al. conducted a survey to evaluate psychosocial stress in 45 adults with AA (18 with AT/AU and 27 with less severe forms of AA, with duration of AA ranging from 1.5 months to 40 years) [23]. Patients rated their stress due to AA as 4.5 ± 2.7 (mean ± SD) on a 10-point scale. While severity of AA did not influence the patient score significantly, scores were lower for patients with hair regrowth (3.5 ± 2.3) than for those without hair regrowth (5.5 ± 2.8; p = 0.01).

Monselise et al. used a scale from the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) tool to measure stress tolerance in adults with AA [24]. Standardized scores are computer-generated from raw scores using a correction factor and are based on a mean ± SD of 100 ± 15 [24]. Mean scores for stress tolerance were significantly lower for patients with AA (91.4 ± 21.8) than for controls (99.5 ± 9.1; p < 0.01), suggesting that patients with AA have more difficulty managing stress than controls [24].

Several studies found a statistically significant association between stressful life events, childhood trauma and certain environmental factors in childhood (e.g. loss of family member, emotional neglect) among adults [30, 34, 40] and adults and children [15] with AA. Alfani et al. reported that 25% of 73 patients with AA noted stressful events at the time of onset or before an exacerbation of AA [8]. A qualitative study suggested that coping strategies evolved over time, changing from concealment of hair loss to acceptance and a more optimistic approach to living with AA [37].

Alexithymia

Alexithymia is characterized by the inability to identify or describe emotions and is believed to be closely related to depression and aggression [54]. TAS-20 and TAS-26 are 20- and 26-item self-report scales that assess the presence of alexithymia [33, 55]. Six studies of adults investigated the association between alexithymia and AA [14, 21, 27, 33, 38, 39], and mean scores were provided in five studies (Table 4). The prevalence of alexithymia was reported to be 23–50% [14, 21, 27, 33, 38].

Table 4.

Measurement of alexithymia in patients with alopecia areata

| AA study population | N | COA tool | Score (mean ± SD)a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults age 18–60 years; 92% with patchy AA, 8% with AT; 52% were women | 50 | TAS-20 | 56.1 ± 14.4; 42% scored positive for alexithymia | Sellami et al. 2014 [33] |

| Adults age > 18 years: Severity not reported; 67% were men | 30 | TAS-20 | 59.1 ± 11.5; 50% scored positive for alexithymia | Dehghani et al. 2017 [14] |

| Adults age ≥ 18 years: Severity not reported; 84% were women | 90 | TAS-20 | 51.2 ± 11.9; 23% had high score (> 61) and 23% borderline score (51–61) | Willemsen et al. 2009 [38] |

| Adults age 18–70 years; 33% with patchy AA, 14% ophiasis, 29% AT, 24% AU; 76% were women | 21 | TAS-20 | 50.1 ± 11.3 | Willemsen et al. 2011 [39] |

| Age, gender, severity not reported | 30 | TAS-26 | 71.2 ± 12.8b; > 30% were considered to have alexithymia | Kuty-Pachecka and Stefanska 2014 [21] |

| Controls: 60.1 ± 13.6; 8% were considered to have alexithymia |

TAS Toronto Alexithymia Scale

aTotal possible scores: TAS-20: 20 items scored on Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); range 20–100; scores > 61 considered alexithymic; scores < 51 considered non-alexithymic; and scores 51–61 considered borderline alexithymic. [38]; TAS-26: 26 items scored on scored on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); range 26–130; scores ≥ 74 considered alexithymic and scores ≤ 62 considered non-alexithymic. [55]

bScore was significantly higher than controls

Discussion

In a recent SLR and meta-analysis, Okhovat et al. reported that AA is positively associated with anxiety (pooled odds ratio [OR] 2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5–4.1) and depression (pooled OR 2.7; 95% CI 1.5–4.8) [3]. Results from the current SLR support those findings, but also suggest that in many patients, AA also has a substantial impact on HRQoL in the domains of personality, emotions, behavior and social functioning, and may be accompanied by acute stress and alexithymia. The relationship between AA severity and the extent of impairment in HRQoL varied across studies. Overall, our findings are consistent with previous SLRs that found that patients with AA experienced a decrease in HRQoL similar to patients with other chronic skin diseases [56] and greater than that in age- and sex-matched controls [57].

There is no published consensus on the appropriate method to measure the psychosocial impact of AA on patients, resulting in the heterogeneity of COA tools and results reporting identified in this review. Despite the range of studies evaluated, these findings may not capture the entire impact of AA on patients. Some COA tools are limited in their assessment of AA-related HRQoL as they predominantly focus on the skin, do not contain questions regarding hair or scalp (e.g. DLQI and Skindex ask about itchy, sore, burning or painful skin) and were not developed with direct input from patients with AA specifically [43, 47]. Consequently, these tools may lack specificity, reliability and validity for measuring concepts that are meaningful to patients with AA. At present, no specific COA tool appears to capture the complete spectrum of AA-related signs, psychosocial and emotional impacts and the development of novel, disease-specific instruments to measure concepts of priority to AA patients should be prioritized.

This SLR identified several additional limitations in the published literature. The results from various COA tools are reported heterogeneously, limiting our ability to compare studies or draw conclusions based on combined results of multiple studies. For instance, several of the COA tools have both total and subdomain scores, and the Skindex and TAS have more than one version, each with a different number of questions and different scoring methods. Furthermore, most of the research included adults only and may not translate to younger patients. Severity of AA was not assessed consistently and, in many studies, the reported severity of AA ranged from mild to severe and included AT/AU. Therefore, mean scores may be of limited value; it may be more informative to assess scores according to disease severity and duration. Although not completely understood, the relationship between AA and psychological disorders may be bidirectional as stress and anxiety are hypothesized to potentiate AA in some patients [58]. Finally, this report focused on the results for patients with AA and provided few comparisons to healthy controls for reference. We did not include results for patients with other dermatologic conditions, as the complexity increases when attempting to compare such diverse results. However, such comparisons may be valuable in the future to better understand the disease-specific burden of AA.

Conclusion

Although it is well-established that patients with AA experience anxiety and depression, they also experience a decrease in HRQoL in many other areas, including personality, emotions, behaviors and social functioning, and these changes may be accompanied by acute stress and alexithymia. To improve our understanding of the impact of AA on patients, it is necessary to achieve consensus on a core set of measures for AA, to standardize reporting practices, and to develop and validate AA-specific measurement tools that can be used in future studies.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The systematic literature review to support this article was sponsored by Pfizer. Pfizer also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Jennica Lewis, PharmD, CMPP, and Charlene Rivera, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer. Sara Lucas of Envision Pharma Group contributed to the development of the systematic literature review, which was funded by Pfizer.

Disclosures

Arash Mostaghimi reports personal fees from Pfizer, hims and 3Derm and equity in Lucid and hims, and is an associate editor at JAMA Dermatology. Lynne Napatalung, Vanja Sikirica, Randall Winnette, Jason Xenakis and Samuel H. Zwillich are employees of, and own stock in Pfizer. Boris Gorsh was an employee of Pfizer at the time the manuscript was written.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397–403. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S53985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okhovat J-P, Marks DH, Manatis-Lornell A, Hagigeorges D, Locascio JJ, Senna MM. Association between alopecia areata, anxiety, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mostaghimi A, Xenakis J, Winnette R, et al. A systematic literature review to identify, describe and interpret evidence on the global burden of moderate to severe alopecia areata. PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019118646. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019118646. Accessed May 15, 2020.

- 5.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abedini R, Hallaji Z, Lajevardi V, Nasimi M, Karimi Khaledi M, Tohidinik HR. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abideen F, Valappil AT, Mathew P, Sreenivasan A, Sridharan R. Quality of life in patients with alopecia areata attending dermatology department in a tertiary care centre—a cross-sectional study. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2018;28:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:304–306. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Mutairi N, Eldin ON. Clinical profile and impact on quality of life: seven years experience with patients of alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:489–493. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annagur BB, Bilgic O, Simsek KK, Guler O. Temperament-character profiles in patients with alopecia areata. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni. 2013;23:326–334. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aschenbeck KA, McFarland SL, Hordinsky MK, Lindgren BR, Farah RS. Importance of group therapeutic support for family members of children with alopecia areata: a cross-sectional survey study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:427–432. doi: 10.1111/pde.13176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cetin ED, Savk E, Uslu M, Eskin M, Karul A. Investigation of the inflammatory mechanisms in alopecia areata. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:53–60. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318185a66e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Hollanda TR, Sodre CT, Brasil MA, Ramos ESM. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a case-control study. Int J Trichol. 2014;6:8–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.136748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehghani F, Kafaie P, Taghizadeh MR. Alexithymia in different dermatologic patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz-Atienza F, Gurpegui M. Environmental stress but not subjective distress in children or adolescents with alopecia areata. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erfan G, Albayrak Y, Yanik ME, et al. Distinct temperament and character profiles in first onset vitiligo but not in alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2014;41:709–715. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essa N, Awad S, Nashaat M. Validation of an Egyptian Arabic version of Skindex-16 and quality of life measurement in Egyptian patients with skin disease. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9677-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghajarzadeh M, Ghiasi M, Kheirkhah S. Depression and quality of life in Iranian patients with alopecia areata. Iran J Dermatol. 2012;14:140–143. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonul M, Cemil BC, Ayvaz HH, Cankurtaran E, Ergin C, Gurel MS. Comparison of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:651–658. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20186131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jankovic S, Peric J, Maksimovic N, et al. Quality of life in patients with alopecia areata: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:840–846. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuty-Pachecka M, Stefanska K. Alexithymia and body-self relations among patients with alopecia areata. Fizjoterapia. 2014;22:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masmoudi J, Sellami R, Ouali U, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a sample of Tunisian patients. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:983804. doi: 10.1155/2013/983804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matzer F, Egger JW, Kopera D. Psychosocial stress and coping in alopecia areata: a questionnaire survey and qualitative study among 45 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:318–327. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monselise A, Bar-On R, Chan L, Leibushor N, McElwee K, Shapiro J. Examining the relationship between alopecia areata, androgenetic alopecia, and emotional intelligence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:46–51. doi: 10.2310/7750.2012.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery K, White C, Thompson A. A mixed methods survey of social anxiety, anxiety, depression and wig use in alopecia. BMJ Open. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nijsten T, Sampogna F, Abeni D. Categorization of Skindex-29 scores using mixture analysis. Dermatology. 2009;218:151–154. doi: 10.1159/000182253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poot F, Antoine E, Gravellier M, et al. A case-control study on family dysfunction in patients with alopecia areata, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:415–421. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi S, Xu F, Sheng Y, Yang Q. Assessing quality of life in alopecia areata patients in China. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20:97–102. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.894641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid EE, Haley AC, Borovicka JH, et al. Clinical severity does not reliably predict quality of life in women with alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, or androgenic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:e97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sahiner IV, Taskintuna N, Sevik AE, et al. The impact role of childhood traumas and life events in patients with alopecia aerate and psoriasis. Afr J Psychiatry (South Africa). 2014;17:1000162. doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.1000162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Giannantoni P, Paradisi A, Abeni D. Relationship between psychosocial burden of skin conditions and symptoms: measuring the attributable fraction. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:60–63. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J, et al. The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas. 2017;108:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sellami R, Masmoudi J, Ouali U, et al. The relationship between alopecia areata and alexithymia, anxiety and depression: a case-control study. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:421. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taheri R, Behnam B, Tousi JA, Azizzade M, Sheikhvatan MR. Triggering role of stressful life events in patients with alopecia areata. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:246–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talaei A, Nahidi Y, Kardan G, et al. Temperament–character profile and psychopathologies in patients with alopecia areata. J Gen Psychol. 2017;144:206–217. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2017.1304889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan H, Lan XM, Yu NL, Yang XC. Reliability and validity assessment of the revised Symptom Checklist 90 for alopecia areata patients in China. J Dermatol. 2015;42:975–980. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welsh N, Guy A. The lived experience of alopecia areata: a qualitative study. Body Image. 2009;6:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willemsen R, Haentjens P, Roseeuw D, Vanderlinden J. Alexithymia in patients with alopecia areata: educational background much more important than traumatic events. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1141–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willemsen R, Haentjens P, Roseeuw D, Vanderlinden J. Hypnosis and alopecia areata: long-term beneficial effects on psychological well-being. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:35–39. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willemsen R, Vanderlinden J, Roseeuw D, Haentjens P. Increased history of childhood and lifetime traumatic events among adults with alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu NL, Tan H, Song ZQ, Yang XC. Illness perception in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata in China. J Psychosom Res. 2016;86:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang M, Zhang N. Quality of life assessment in patients with alopecia areata and androgenetic alopecia in the People's Republic of China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:151–155. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S121218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ware JE. SF-36 Health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 healthy survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nijsten TEC, Sampogna F, Chren MG, Abeni DD. Testing and reducing skindex-29 using Rasch analysis: Skindex-17. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1244–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chren M, Lasek R, Sahay A, Sand L. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chren M-M, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1433–1440. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890470111018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707–713. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sampogna F, Spagnoli A, Di Pietro C, et al. Field performance of the Skindex-17 quality of life questionnaire: a comparison with the Skindex-29 in a large sample of dermatological outpatients. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:104–109. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farmer RF, Goldberg LR. A psychometric evaluation of the revised Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-R) and the TCI-140. Psychol Assess. 2008;20:281–291. doi: 10.1037/a0012934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. JAMA Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sereda Y, Dembitskyi S. Validity assessment of the symptom checklist SCL-90-R and shortened versions for the general population in Ukraine. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:300. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hemming L, Haddock G, Shaw J, Pratt D. Alexithymia and its associations with depression, suicidality, and aggression: an overview of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:203. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Ryan DP, Parker JD, Doody KF, Keefe P. Criterion validity of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:500–509. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rencz F, Gulácsi L, Péntek M, Wikonkál N, Baji P, Brodszky V. Alopecia areata and health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:561–571. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kutlu O, Aktas H, Imren IG, Metin A. Short-term stress-related increasing cases of alopecia areata during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatol Treat. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1782820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fayyazi Bordbar MR, Faridhosseini F, Kaviani H, Kazemian M, Samari AA, Kashani Lotfabadi M. Temperament and character personality dimensions in patients with bipolar I disorder. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2014;25:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown TA, Cash TF, Mikulka PJ. Attitudinal body-image assessment: factor analysis of the body-self relations questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:135–144. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.