Abstract

Membrane contact sites (MCSs) formed between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the plasma membrane (PM) provide a platform for nonvesicular lipid exchange. The ER-anchored tricalbins (Tcb1, Tcb2, and Tcb3) are critical tethering factors at ER–PM MCSs in yeast. Tricalbins possess a synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial-lipid-binding protein (SMP) domain and multiple Ca2+-binding C2 domains. Although tricalbins have been suggested to be involved in lipid exchange at the ER–PM MCSs, it remains unclear whether they directly mediate lipid transport. Here, using in vitro lipid transfer assays, we discovered that tricalbins are capable of transferring phospholipids between membranes. Unexpectedly, while its lipid transfer activity was markedly elevated by Ca2+, Tcb3 constitutively transferred lipids even in the absence of Ca2+. The stimulatory activity of Ca2+ on Tcb3 required intact Ca2+-binding sites on both the C2C and C2D domains of Tcb3, while Ca2+-independent lipid transport was mediated by the SMP domain that transferred lipids via direct interactions with phosphatidylserine and other negatively charged lipid molecules. These findings establish tricalbins as lipid transfer proteins, and reveal Ca2+-dependent and -independent lipid transfer activities mediated by these tricalbins, providing new insights into their mechanism in maintaining PM integrity at ER–PM MCSs.

Keywords: tricalbin, membrane contact sites, SMP, lipid transfer, endoplasmic reticulum, plasma membrane

Abbreviations: cER, cortical endoplasmic reticulum; E-Syt, extended-synaptotagmin; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FRET, Förster resonance energy transfer; LTP, lipid transfer protein; MCS, membrane contact site; NBD, 7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PI, phosphoinositide; PM, plasma membrane; PS, phosphatidylserine; SMP, synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial lipid-binding protein

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) forms a dynamic membrane network and distributes throughout the cell (1). It engages in extensive communications with the plasma membrane (PM) and other membrane organelles by membrane contact sites (MCSs). The ER–PM MCSs are essential for calcium homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and signal transduction, which are mediated by diverse functional proteins (2, 3, 4, 5). Lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) sense and transport lipids between the membranes and play central roles at ER–PM MCSs (6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Most of the LTPs span and tether two opposed membranes when they perform lipid exchange, highlighting the essential roles of LTPs in maintaining the architectures of MCSs. Nevertheless, the cooperation of many factors at MCSs increases difficulties in discriminating an LTP’s lipid transfer function from membrane tethering.

In yeast, nearly half of the PM is associated with the cortical ER (cER) (11, 12, 13). Several proteins, such as Ist2, Scs2/Scs22, and Tcb1/2/3, are involved in controlling the ER–PM MCSs (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). The tethering mechanisms of Ist2 and Scs2/Scs22 have been well studied, whereas how tricalbins (Tcb1/2/3) function at ER–PM contact sites remains largely unknown. Of interest, the ER–PM MCSs in yeast mutants lacking tricalbins remain intact, suggesting that these proteins may play additional roles than membrane tethering (15, 19). For instance, tricalbins participate in maintaining local PM integrity (11, 20).

Tricalbins are homologs of mammalian extended-synaptotagmins (E-Syts), which belong to the synaptotagmin-like mitochondrial lipid-binding protein (SMP) domain protein family (7, 21, 22, 23). All tricalbins are anchored to the ER membrane through their N-terminal hydrophobic domain, followed by an SMP domain and multiple C2 domains. SMP domain–containing proteins are members of the superfamily of tubular lipid-binding (TULIP) domain-containing proteins, which have the potentials for membrane binding (24, 25, 26, 27, 28). The crystal structure of E-Syt2 indicates SMP domains form dimers of 9-nm-long cylinders that harbor glycerolipids (29). E-Syt1 was demonstrated as a Ca2+-dependent LTP at ER–PM MCSs, transferring glycerophospholipids and DAG (30, 31). Correspondingly, the localization and lipid transfer activity of E-Syt1 is highly dependent on the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (30, 31, 32, 33). Unlike E-Syt1, tricalbins constitutively localize at ER–PM MCSs in yeast, albeit multiple C2 domains contain Ca2+-binding residues (11, 15, 19, 34). Of interest, both the SMP domain and C2 domains can mediate the localization of tricalbins to ER–PM MCSs (11, 19, 34). Recent studies showed that tricalbins induce curved cER membranes, which shorten the ER–PM distances and may facilitate the lipid extraction or transport (11, 34). However, it remains unclear whether tricalbins can directly transfer lipids between the ER and the PM.

In this work, we examined the functions and molecular mechanisms of Tcb3 in reconstituted systems. We discovered that Tcb3 transfers lipids between membranes even in the absence of Ca2+, while Ca2+ potently increases the lipid transfer. Mechanically, all the processes of lipid transfer were mediated by the SMP domain. For the Ca2+-stimulated lipid transfer, the intact Ca2+-binding sites on C2C and C2D domains are required. In the Ca2+-independent lipid transport, Tcb3 transfers lipids through interactions between the SMP domain and negatively charged lipids without any C2 domain requirement. These data suggest tricalbins are LTPs capable of transferring lipids at ER–PM MCSs. Our findings provide the first evidence that the SMP domain itself is capable of transferring lipids, although the transferring efficiency is subject to Ca2+-C2 domain interactions.

Results

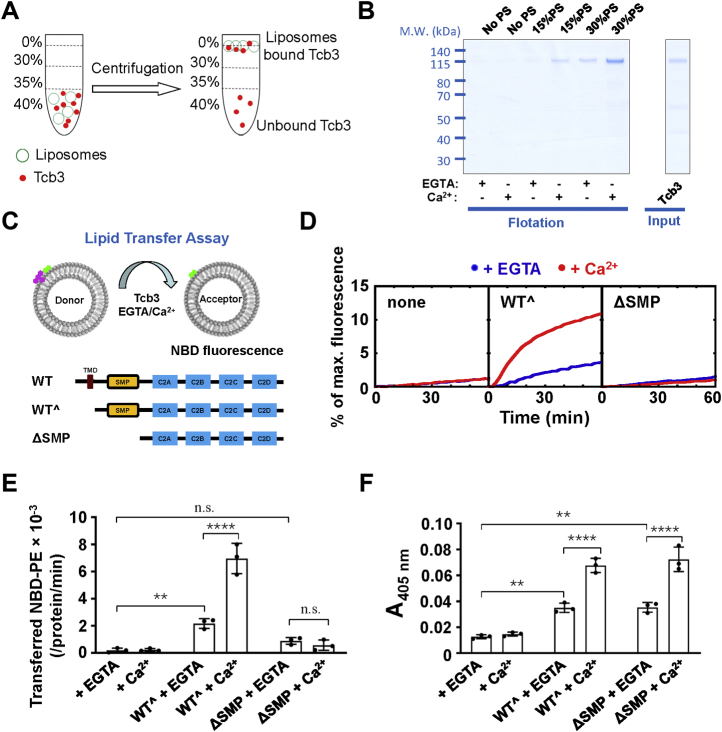

Tcb3 interacts with membranes dependent on the negatively charged PS

To study how tricalbins perform functions at ER–PM MCSs, we expressed and purified the cytosolic domain of Tcb3 (referred to as Tcb3 hereinafter) that contains intact SMP and all four C2 domains. We first examined how Tcb3 interacts with the membranes. In a liposome coflotation assay, we found that Tcb3 does not bind to neutral liposomes prepared by phosphatidylcholine (PC) (Fig. 1, A and B). Since the cytoplasmic face of the PM is rich in negatively charged lipids, mainly the phosphatidylserine (PS) (35, 36, 37), we then included PS in the liposomes. We observed that Tcb3 interacted with the liposomes in a PS concentration-dependent manner even in the absence of Ca2+. The inclusion of Ca2+ markedly enhanced the Tcb3–membrane associations (Fig. 1B). These data demonstrated that Tcb3 interacts with PS on the membranes even without Ca2+, in contrast to E-Syt1, which binds to membranes only in the presence of Ca2+ (30).

Figure 1.

Tcb3 directly transfers lipids in both Ca2+-dependent and -independent manners.A, diagram of the liposome coflotation assay used to study Tcb3–liposome interactions. B, Left, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gel showing the binding of Tcb3 to protein-free liposomes in the presence of 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. The liposomes were prepared with phosphatidylcholine and the indicated percentage of phosphatidylserine. Right, Coomassie blue–stained gel showing the recombinant Tcb3 protein. The amount of Tcb3 protein was loaded as 10% of the total input. C, Top, diagram of the FRET-based lipid transfer assay. Prior to the lipid transfer reaction, NBD emission from the donor liposomes was quenched by neighboring rhodamine molecules through FRET. The transfer of fluorescence-labeled lipids results in the dequenching of the NBD fluorescence. Bottom, schematic diagrams of WT and mutant Tcb3 proteins. WTˆ was used to represent the cytosolic domain of Tcb3 hereinafter. The SMP domain corresponds to amino acids 217 to 422 of Tcb3. D, lipid transfer of the protein-free liposomes in the absence or presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutant). The lipid transfer reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. The data are presented as the percentage of maximum fluorescence change. E, initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine in the reactions shown in D. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., p > 0.05. ∗∗p = 0.0058. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (2, 12) = 125.1, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 12) = 37.18, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (2, 12) = 44.99, p < 0.0001. F, effects of WTˆ or mutant Tcb3 on membrane tethering in a liposome tethering assay. Turbidity was evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm, reflecting the clusters of liposomes induced by Tcb3. The tethering reactions proceeded for 30 min at room temperature in the absence or presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutants). The reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., p > 0.05. ∗∗p = 0.0016 and 0.0014, respectively. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (2, 12) = 120.2, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 12) = 101.6, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (2, 12) = 21.60, p = 0.0001.

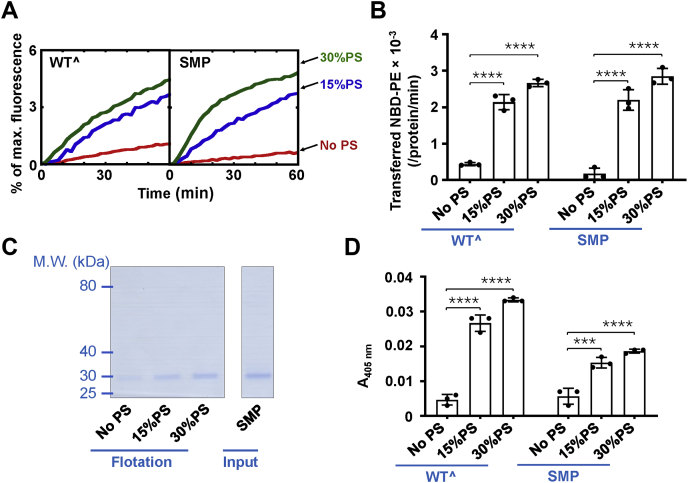

Tcb3 directly mediates lipid transfer between lipid membranes

Next, we examined if Tcb3 can transfer lipids in vitro. In a Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based lipid transfer assay (Fig. 1C), Tcb3 drove a robust lipid transfer in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1, D and E). No obvious FRET was observed when the acceptor liposomes were omitted, confirming the fluorescence dequenching is not caused by simple protein–lipid interactions or lipid extractions (Fig. S1). The dose-dependent transfer efficiency further supports the lipid transfer is mediated explicitly by Tcb3 (Fig. S2). Unexpectedly, we observed a significant level of lipid transport mediated by Tcb3 in the absence of Ca2+. Both Ca2+-dependent and -independent lipid transport were abolished when the SMP domain was removed, suggesting that the observed lipid transport was specifically mediated by the SMP domain (Fig. 1, D and E).

All three tricalbins constitutively localize at ER–PM MCSs, which is different from the Ca2+-dependent localization of E-Syt1 (15, 19, 33). We next performed a liposome tethering assay to study Tcb3’s tethering functions by measuring the liposome clustering-induced turbidity. We observed that Tcb3 could mediate liposome tethering, and Ca2+ further improved its tethering activity (Fig. 1F). These data are consistent with previous reports that Tcb3 constitutively tethers the two opposed membranes at ER–PM junctions where the intermembrane connections are modulated by elevated Ca2+ (34). Deleting the SMP domain had little effect on Tcb3’s tethering activity but completely abolished the lipid transfer, indicating the membrane tethering itself is inefficient to drive the lipid transfer.

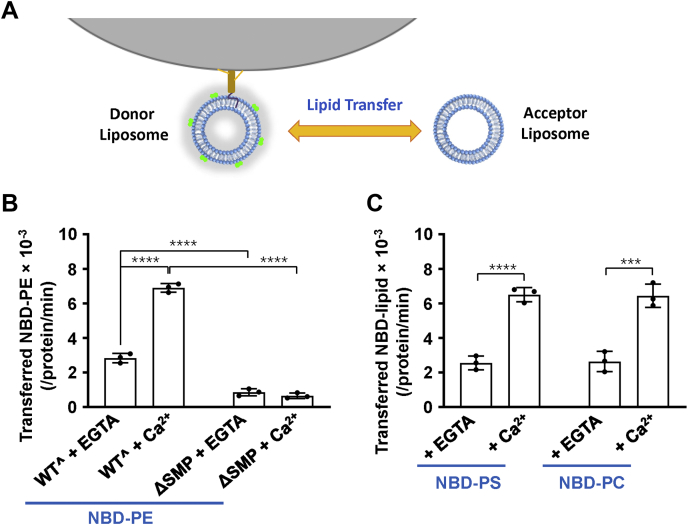

To confirm the lipid transfer activities of Tcb3, we employed another fluorescent lipid transfer assay that we previously developed by separating donor and acceptor liposomes (Fig. 2A) (30). From this assay, we observed that Tcb3 transfers NBD-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) without Ca2+ and Ca2+ dramatically increases its transfer efficiency (Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with that from FRET-based lipid transfer assay, supporting that Tcb3 is an LTP coupled with Ca2+. In addition, we observed Tcb3 transferred NBD-PC and NBD-PS as well (Fig. 2C), indicating it nonspecifically transfers glycerophospholipids. We estimated each Tcb3 could totally transfer about three lipid molecules per minute in the presence of Ca2+, at a level comparable with E-Syt1 (30).

Figure 2.

Tcb3 nonselectively transfers phospholipids between membrane bilayers in the presence or absence of Ca2+.A, diagram of the fluorescent lipid transfer assay. The fluorescence-labeled donor liposomes were anchored to agarose beads through the biotin–avidin conjugation. The lipid transfer reactions were carried out by incubation of bead-bound donor liposomes and acceptor liposomes at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutant). The reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. After incubation, acceptor liposomes were separated by protease K digestions and NBD fluorescence was measured. B, the lipid transfer activity of NBD-PE. Data are presented as the molecules of NBD-phosphatidylethanolamine transferred from the donor liposomes to the acceptor liposomes per minute per protein. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (1, 8) = 1010, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 8) = 222.7, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (1, 8) = 272.1, p < 0.0001. C, the lipid transfer activity of NBD-phosphatidylcholine and NBD-phosphatidylserine. Data are presented as the molecules of NBD-labeled lipids transferred from the donor liposomes to the acceptor liposomes per minute per protein. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗p = 0.0001. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (1, 8) = 0.0005806, p = 0.9814 for lipid factor and F (1, 8) = 159.1, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. The interaction between the two factors is F (1, 8) = 0.05239, p = 0.8247.

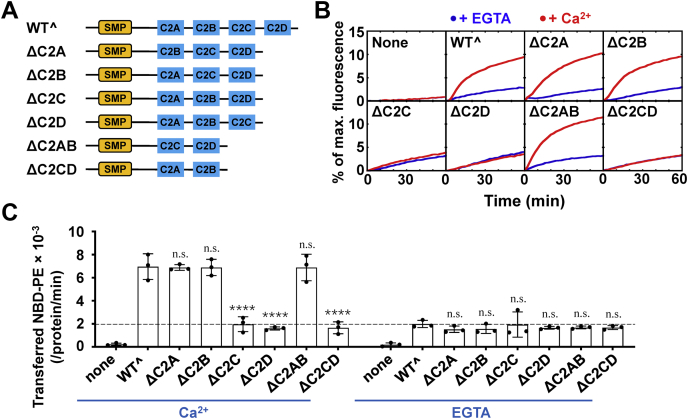

The promotion of Tcb3-mediated lipid transfer by Ca2+ requires intact Ca2+-binding sites on C2C and C2D domains

Tricalbins and their mammalian homologs E-Syts are all C2 domain-containing proteins. The C2 domains are connected in series and interact with membranes to mediate the ER–PM tethering. Our lipid transfer assays showed that the lipid transfer mediated by Tcb3 is highly enhanced by Ca2+, suggesting that the interactions of C2 domains with Ca2+ are essential to its lipid transfer activity. We then examined the functional importance of the C2 domains by individual domain deletions. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tcb3 we used in this study has four C2 domains, of which only the C2B domain does not contain the Ca2+-binding sites (Fig. 3A). As expected, the C2B domain deletion had little effect on the Ca2+-stimulated lipid transfer (Fig. 3, B and C). We and other groups showed that the C2A domain, which directly connects the C2 domains to the SMP domain, is essential in Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer mediated by E-Syt1 (30, 31). Unexpectedly, the lipid transport was not affected when we deleted the C2A domain in Tcb3 (Fig. 3, B and C). Removal of both C2A and C2B domains had little effect on the Ca2+-dependent lipid transport, confirming that these two C2 domains are dispensable for the Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer activity (Fig. 3, B and C). The distinct role of the C2A domain in Tcb3 and E-Syt1 suggests these two proteins share divergent mechanisms in lipid transfer. In contrast, when we deleted either the C2C domain or the C2D domain, the Ca2+-stimulated lipid transport was completely abolished (Fig. 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

The C2C and C2D domains are indispensable for Ca2+-stimulated lipid transfer mediated by Tcb3.A, schematic diagrams of WTˆ and mutant Tcb3 proteins. B, lipid transfer of the protein-free liposomes in the absence or presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutants). The lipid transfer reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. C, initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine in the reactions shown in B. The dashed line indicates the level of Ca2+-independent lipid transfer. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., p > 0.05. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (7, 32) = 48.02, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 32) = 238.8, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (7, 32) = 34.34, p < 0.0001.

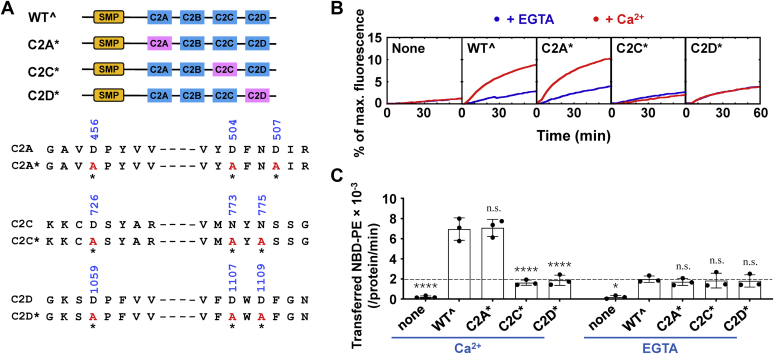

To further define which C2 domains confer the Ca2+ sensitivity, we tested Tcb3 mutants bearing substitutions in the conserved Ca2+-binding residues of the C2A, C2C, or C2D domain (Fig. 4A). We found that the mutations of the Ca2+-binding sites in either the C2C or C2D domain abolished the Ca2+-stimulated lipid transport. In contrast, the mutations in the C2A domain had little effect on the lipid transfer activity, consistent with our findings that the C2A domain is dispensable for the lipid transfer activity of Tcb3. Thus, Ca2+ binding to the C2C and C2D domains rather than the C2A domain is required for Tcb3’s Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer activation (Fig. 4, B and C). All the C2 domain mutations had little effect on the basal lipid transport without Ca2+, indicating the C2 domain mutations only influence Ca2+-stimulated lipid transfer without reflection of Ca2+-independent transfer in our assays.

Figure 4.

The Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer activity of Tcb3 requires the intact Ca2+-binding sites on both C2C and C2D domains.A, Top, schematic diagrams of WTˆ and mutant Tcb3 proteins. WTˆ C2 domains are shown in blue, and mutant C2 domains are shown in pink. Bottom, sequences showing the aspartic acid or asparagine residues in the C2A, C2C, and C2D domains of Tcb3 that coordinate Ca2+ binding. Mutated residues are indicated with residue numbers shown on the top and asterisks shown at the bottom. B, lipid transfer of the protein-free liposomes in the absence or presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutants). The lipid transfer reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. C, initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine in the reactions shown in B. The dashed line indicates the level of Ca2+-independent lipid transfer. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., p > 0.05. ∗p = 0.0355. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (4, 20) = 59.14, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 20) = 90.03, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (4, 20) = 35.18, p < 0.0001.

The C2 domains are dispensable for Tcb3-mediated lipid transfer in the absence of Ca2+

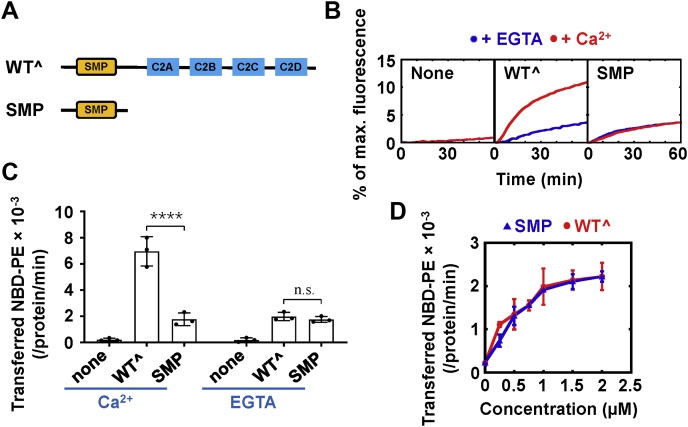

Although both Tcb3 and E-Syt1 can mediate Ca2+-dependent lipid transport, the lipid transfer was observed only in Tcb3-mediated reactions in the absence of Ca2+. Whether the C2 domains are critical in Ca2+-independent lipid transfer is mysterious. We removed all the four C2 domains to examine the roles of C2 domains (Fig. 5A). Unexpectedly, we found that the SMP domain drove a level of lipid transfer comparable with that of the wild-type Tcb3 and the transfer activity does not respond to Ca2+ (Fig. 5, B and C). Further studies showed that the SMP domain dose dependently resembles Tcb3’s lipid transfer activity (Fig. 5D). These data suggested that Tcb3 could mediate a constitutive lipid transfer through the SMP domain without any C2 domain requirement.

Figure 5.

Tcb3 mediates Ca2+-independent lipid transfer through its SMP domain without the requirement of the C2 domains.A, schematic diagrams of WTˆ and mutant Tcb3 proteins. B, lipid transfer of the protein-free liposomes in the absence or presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutant). The lipid transfer reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. C, initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled PE in the reactions shown in B. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s., p > 0.05. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (2, 12) = 99.85, p < 0.0001 for protein factor and F (1, 12) = 44.91, p < 0.0001 for Ca2+ factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (2, 12) = 43.93, p < 0.0001. D, dose dependence of Tcb3 (WTˆ or mutant) activity in the lipid transfer reaction. Tcb3 or the SMP domain fragment was added to the lipid transfer reaction at the indicated concentrations in the presence of 0.1 mM EGTA. Initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled PE are shown. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates).

The SMP domain interacts with the negatively charged lipids to mediate lipid transfer

Next, we sought to delineate the mechanism by which the SMP domain mediates lipid transfer in the absence of Ca2+. Previous studies in yeasts showed that the Tcb3 mutant lacking all C2 domains still localized to the cER, indicating that the SMP domain could interact with the membranes (11, 15). Another biochemical study showed that the SMP domains have a low affinity with artificial protein-free membranes, supporting that the Tcb3’s SMP domain may interact with the lipid membranes (19). The PM is rich in negatively charged lipids. Especially, the inner leaflet of yeast PM contains more than 20% of the PS (35, 36). We reasoned that the SMP domain might transfer lipids through its interaction with the negatively charged lipids on the PM. In supporting this, when we changed the lipid composition by reducing the percentage of PS, Tcb3 and SMP domain-mediated lipid transfer rates were strongly decreased. In contrast, the lipid transfer rates were correspondingly accelerated by increasing PS contents in the reactions (Fig. 6, A and B, and Fig. S3).

Figure 6.

The SMP domain of Tcb3 interacts with PS to transfer lipids between membranes.A, effect of PS on the lipid transfer activity mediated by Tcb3 or the SMP domain. Lipid transfer of the protein-free liposomes in the presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or the SMP domain). PS was reconstituted into the liposomes at the indicated concentrations. The lipid transfer reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA. B, initial lipid transfer rates of NBD-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine in the reactions shown in A. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (2, 12) = 290.2, p < 0.0001 for lipid factor and F (1, 12) = 0.005379, p = 0.9427 for protein factor. The interaction between the two factors is F (2, 12) = 2.350, p = 0.1376. C, Left, Coomassie blue–stained SDS-PAGE gel showing the binding of the SMP domain to protein-free liposomes in the presence of 0.1 mM EGTA. The liposomes were prepared with phosphatidylcholine and the indicated percentage of PS. Right, Coomassie blue–stained gel showing the recombinant Tcb3 SMP domain protein. The amount of protein was loaded as 30% of the total input. D, effect of PS on the membrane tethering activity of Tcb3. The turbidity of the protein-free liposomes with the indicated percentage of PS in the presence of 1 μM Tcb3 (WTˆ or the SMP domain) was shown. The reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent replicates). p Values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ∗∗∗p = 0.0001. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. F (2, 12) = 266.1, p < 0.0001 for lipid factor and F (1, 12) = 117.2, p < 0.0001 for protein factor. A significant interaction between the two factors is F (2, 12) = 38.31, p < 0.0001. PS, phosphatidylserine.

In the liposome coflotation assay, we observed that the SMP domain was bound to the PS-containing liposomes (Fig. 6C). The Tcb3–membrane association is PS dose dependent, consistent with our finding that the SMP domain drives lipid transfer through interactions with the negatively charged PS (Fig. 6, A and B). We next carried out the liposome tethering assay to examine whether the SMP domain alone could tether the membranes. We found that the SMP domain can tether liposomes and the tethering activity increases along with the rise of PS content (Fig. 6D). It is noted that the tethering activity of widetype Tcb3 is higher than that of its SMP domain, indicating the C2 domains may play additional tethering function even in the absence of Ca2+.

In addition to PS, there are other charged lipids on the PM. We replaced PS with phosphoinositide (PI) or PI(4,5)P2, another two important negatively charged lipids at ER–PM MCSs. Both PI and PI(4,5)P2 enhanced the protein–membrane associations (Fig. S4). Of interest, they could resemble the roles of PS in Tcb3-mediated lipid transfer and membrane tethering (Figs. S5 and S6). Together, these data suggest that Tcb3 uses its SMP domain to bind negatively charged lipids on the PM, thus transferring lipids between membranes.

Discussion

MCSs, built by numerous protein–membrane complexes, are essential for interorganelle communications (38). The ER–PM MCSs are dynamically controlled by a variety of tethering regulators that connect the close opposed membranes. These regulators act synergistically to maintain the local architecture and enable communications between organelles (6, 9, 39). Although some critical tethering factors were identified, our knowledge about their functions and mechanisms remains primitive. Although E-Syt1 has been extensively studied in mammals, we still know little about its yeast homologs. The tricalbins and E-Syt1 are distinct in many fundamental aspects. Specifically, the cytosolic Ca2+ determines the ER surface distribution of E-Syt1, while Tcb3 constitutively localizes at MCSs regardless of Ca2+. Whether Tcb3 can directly mediate lipid transport beyond its tethering function remains elusive.

It is challenging to delineate an individual regulator involved in the complex ER–PM interfaces. We sought to address the functions and mechanisms of tricalbins in a defined system using purified components without the complications of other factors naturally present in the cell (30). By this defined system, we demonstrated that Tcb3 could transfer lipids through its SMP domain between the membranes. The SMP domain interacts with the negatively charged lipids, thereby tethering the membranes and transferring lipids. We showed that Ca2+ potently improves the Tcb3-mediated membrane tethering and lipid transfer activities. Unexpectedly, the C2A domain–Ca2+ interaction is dispensable for Tcb3’s lipid transfer activity. Instead, both the intact C2C and C2D domains of Tcb3 are required for Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer. Other groups and we previously showed that the C2A domain is indispensable for E-Syt1-mediated lipid transport (30, 31). The C2A domain was suggested as a switch that inactivates E-Syt1’s SMP domain. Ca2+ binding releases the autoinhibition and enables lipid transport (32). Our findings suggested that this autoinhibitory function of the C2A domain is not conserved in tricalbins. The C2A domain of tricalbins may be involved in other processes, such as interacting with the ER membrane to induce membrane curvature (34, 38).

In the absence of Ca2+, our lipid transfer assays showed that Tcb3 transfers lipids solely through the SMP domain without any C2 domain requirement. We also found that the SMP domain interacts with the membranes and mediates the membrane tethering. However, this membrane tethering was strengthened by the C2 domains, suggesting that the PM targeting of Tcb3 requires the C2 domains even without Ca2+. This conclusion is consistent with previous findings in yeast that the ER–PM MCS localization of Tcb3 requires both the SMP and the C2 domains, albeit each of them could partially localize to these specific regions (11, 19, 34). Our study suggests that the C2 domains may loosely bind to the PM in the low concentration of Ca2+, contributing to the PM targeting but not lipid transport. At high Ca2+ conditions, the C2C and C2D domains are tightly bound to the PM, consistent with the cryo-ET study where C2 domain density increases on the PM (11, 19).

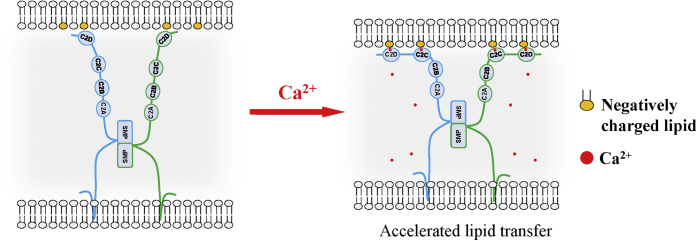

The physiological studies in yeast indicated that Tcb3 is required for maintaining the PM integrity under heat stress, which needs substantial lipid influx (11, 19). Our study demonstrated that Tcb3 can directly transport lipids, suggesting that it may contribute to the new lipid supplement through lipid transport. SYT1, a plant homolog of tricalbin, is also involved in maintaining the PM integrity under different stresses, suggesting that PM repair is a conserved function for this protein family. A recent study showed that Tcb3 partially localized to MCSs between the ER and the Golgi apparatus and might be engaged in the ceremide transport (40). Here we directly show that Tcb3 is an LTP at ER–PM MCSs using our defined system. Under the low-Ca2+ stage, Tcb3 loosely binds to the PM via the SMP domain and C2 domains, slowly transferring lipids. In response to the cytosolic Ca2+ increase, the C2C and C2D domains interact with the PM membrane, strengthening the ER and the PM connections and accelerating the ER–PM lipid exchange (Fig. 7). Upon heat-induced membrane stress, the cytosolic Ca2+ increases through the damaged PM, possibly enhancing the Tcb3–PM interactions and accelerating lipid transport to meet the PM repair requirements (11, 41). It remains unknown whether Tcb3 functions at MCSs in the stage of low Ca2+. In this work, we observed Tcb3 could transfer lipids in the absence of Ca2+, suggesting that it has the potential to mediate a slow level of lipid transport under low Ca2+. However, the physiological significance needs to be further studied. By the in vitro lipid transfer assays, we estimated that each Tcb3 could transfer at least three lipid molecules per minute, comparable with E-Syt1, which transfers 6 to 7 lipid molecules per minute (30). However, there are many other regulators cooperatively maintaining the architecture of MCSs, for example, the Ist2 and Scs2/Scs22. These factors may facilitate the membrane tethering and the Tcb3–protein interactions. The lipid transfer rate of Tcb3 in vivo could be largely improved, higher than the one we estimated.

Figure 7.

Model illustrating the activation of Tcb3 at ER–PM membrane contact sites. When cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is low, Tcb3 loosely binds to the PM. The SMP domain dynamically interacts with the membranes, slowly transferring lipids. Once the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration increases, the C2C and C2D domains bind to the PM tightly, strengthening the ER and the PM connections and enhancing the ER–PM lipid exchange. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PM, plasma membrane.

Taken together, these findings identify Tcb3 as a Ca2+-regulated LTP. Beyond the membrane tethering, the lipid transfer activation is another conserved function for the E-Syt family. Our study establishes the molecular mechanism by which Tcb3 transfers lipids between the membranes, revealing that Tcb3 and E-Syt1 have conserved and divergent mechanisms regulating lipid transport in yeast or mammalian cells.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

Recombinant untagged Tcb3 (aa. 194–1225) were expressed in E. coli and purified by nickel affinity chromatography, using a previously established procedure (42, 43, 44, 45). The S. cerevisiae TCB3 gene was cloned into a pET28a-based SUMO vector. Purified His6-SUMO-Tcb3 fusion proteins were digested by SUMP proteases to remove the extra tags. The protein was subsequently dialyzed overnight against a storage buffer (25 mM Hepes [pH7.4], 150 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). Tcb3 mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and were expressed following the same procedure as the wildtype (WT) protein.

Liposome preparation

All lipids used in this work were acquired from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. For acceptor liposomes, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC, CAT#850457C) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS, CAT#840034C) were mixed in a molar ratio of 85:15. For donor liposomes, POPC, POPS, N-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole-4-yl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (NBD-DPPE, CAT# 810144C), and N-(Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (rhodamine-DPPE, CAT#810158C) were mixed at a molar ratio of 82:15:1.5:1.5. The liposomes were generated by detergent dilution and isolated on a Nycodenz density gradient flotation (46, 47). The detergent was removed by overnight dialysis of the samples in Novagen dialysis tubes against the reconstitution buffer (25 mM Hepes [pH 7.4], 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT). Other liposomes used in this study were generated by the same procedure, except with different lipid compositions.

FRET-based lipid transfer assay

A standard FRET-based lipid transfer reaction (60 μl) contained unlabeled acceptor liposomes (1.5 mM total lipids) and donor liposomes (167 μM total lipids) labeled with NBD and rhodamine in the presence or absence of 1 μM Tcb3 and was conducted in a 96-well Nunc plate at 37 °C (30). Increase in NBD-fluorescence at 538 nm (excitation 460 nm) was measured every 2 min in a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. At the end of the reaction, 10 μl of 10% CHAPSO was added to the liposomes. The data are presented as the percentage of maximum fluorescence change, which can be converted to the molecules of transferred NBD-PE according to the total amounts of NBD-PE. The molecules of transferred NBD-PE within the first 20 min of lipid transfer reaction were used to calculate the initial rate of a lipid transfer reaction. The formula used in calculation is: VNBD-PE = (NNBD-PE ∗ PNBD-PE/NTcb3)/treaction. NNBD-PE represents the total number of NBD-PE in each reaction. PNBD-PE represents the percentage of NBD-PE transferred in each reaction; NTcb3 represents the total number of Tcb3 proteins in each reaction. treaction represents the time of each lipid transfer reaction. Full accounting of statistical significance was included for each figure based on at least three independent experiments.

Fluorescent lipid transfer assay

The fluorescent lipid transfer assay was performed as described (30). The lipid composition of donor liposomes was POPC, POPS, 1-(12-biotinyl(aminododecanoyl))-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DSPE-Biotin, CAT#880129P) and NBD-DPPE at a molar ratio of 81:15:2:2. The biotin-labeled donor liposomes were incubated with avidin-conjugated agarose beads at room temperature for 1 h. After washing five times with the reconstitution buffer, the bead-bound donor liposomes (167 μM total lipids) were incubated with acceptor liposomes (1.5 mM total lipids) at 37 °C in the presence or absence of 1 μM Tcb3. The reactions included 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. After 1 h of incubation, protease K was added to stop the reactions. The avidin beads were recovered by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 2 min. NBD fluorescence in the supernatant was measured in a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. The percentage of transferred NBD-PE was calculated by the NBD fluorescence in the supernatant to the original fluorescence of donor liposomes. The lipid transfer rates are presented as the molecules of transferred NBD-PE per protein per minute and calculated by the same formula as the FRET-based lipid transfer assay. The transfer of NBD-labeled PS or PC was conducted in the same way as for NBD-PE, except that NBD-PS (CAT# 810195C) or NBD-PC (CAT# 810133C) was included in the donor liposomes. The total lipid transfer rate of Tcb3 protein was estimated using the formula: Vtotal = [(NPC ∗ PPC + NPS ∗ PPS + NPE ∗ PPE)/NTcb3]/treaction. N represents the total amount of a lipid species (the sum of labeled and unlabeled) in each reaction. P represents the percentage of a lipid species transferred indicated by the NBD-labeled lipids. Full accounting of statistical significance was included for each figure based on at least three independent experiments.

Liposome tethering assay

The turbidity, which reflects liposome clustering, was employed to evaluate the liposome tethering (31, 32). In the tethering assay, the lipid composition of donor liposomes was POPC and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid)succinyl](nickel salt) (DGS-NTA (Ni), CAT#790404P) at a molar ratio of 90:10. The reactions were performed similar to those in FRET-based lipid transfer assays, except the absorbance at 405 nm was measured at 30 min using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. Full accounting of statistical significance was included for each figure based on at least three independent experiments.

Liposome coflotation assay

The binding of soluble factors with membranes was examined using a liposome coflotation assay, as described (44, 48). Tcb3 was incubated with liposomes at 4 °C with gentle agitation in the presence of 0.1 mM EGTA or CaCl2. An equal volume (150 μl) of 80% Nycodenz (w/v) in the reconstitution buffer was added after 1 h, and the mixture was transferred to 5-mm by 41-mm centrifuge tubes. The samples were overlaid with 200 μl each of 35% and 30% Nycodenz, and then with 20 μl reconstitution buffer on the top. The gradients were centrifuged for 4 h at 48,000 rpm in a Beckman SW55 rotor. Liposome samples were collected from the 0/30% Nycodenz interface (2 × 20 μl) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software for Windows. Statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA, and p value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Data availability

All data presented are contained within the main article and supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jingshi Shen for insightful discussions and Xiaojun Wang for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants (Nos. 91854117 and 31871425), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20200036), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province, and Jiangsu Distinguished Professor Funding.

Author contributions

Y. L. and H. Y. conceived the project. T. Q., C. L., and R. H. performed the experiments. T. Q., C. L., C. W., and H. Y. analyzed the data. T. Q., C. W., Y. L., and H. Y. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Edited by Roger Colbran

Contributor Information

Yinghui Liu, Email: yinghuiliu@njnu.edu.cn.

Haijia Yu, Email: yuhaijia@njnu.edu.cn.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Bonifacino J.S., Glick B.S. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 2004;116:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahiri S., Toulmay A., Prinz W.A. Membrane contact sites, gateways for lipid homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;33:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine T., Loewen C. Inter-organelle membrane contact sites: Through a glass, darkly. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wieckowski M.R., Giorgi C., Lebiedzinska M., Duszynski J., Pinton P. Isolation of mitochondria-associated membranes and mitochondria from animal tissues and cells. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1582–1590. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toulmay A., Prinz W.A. Lipid transfer and signaling at organelle contact sites: The tip of the iceberg. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011;23:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefan C.J. Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contacts: Principals of phosphoinositide and calcium signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020;63:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeyasimman D., Saheki Y. SMP domain proteins in membrane lipid dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2020;1865:158447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockcroft S., Raghu P. Phospholipid transport protein function at organelle contact sites. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018;53:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saheki Y., De Camilli P. Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017;86:659–684. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kentala H., Weber-Boyvat M., Olkkonen V.M. OSBP-related protein family: Mediators of lipid transport and signaling at membrane contact sites. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016;321:299–340. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collado J., Kalemanov M., Campelo F., Bourgoint C., Thomas F., Loewith R., Martinez-Sanchez A., Baumeister W., Stefan C.J., Fernandez-Busnadiego R. Tricalbin-mediated contact sites control ER curvature to maintain plasma membrane integrity. Dev. Cell. 2019;51:476–487.e47711. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quon E., Sere Y.Y., Chauhan N., Johansen J., Sullivan D.P., Dittman J.S., Rice W.J., Chan R.B., Di Paolo G., Beh C.T., Menon A.K. Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane contact sites integrate sterol and phospholipid regulation. PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pichler W.J. Drug allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;1:285–286. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000011027.38878.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang D., Vjestica A., Oliferenko S. Plasma membrane tethering of the cortical ER necessitates its finely reticulated architecture. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:2048–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manford A.G., Stefan C.J., Yuan H.L., Macgurn J.A., Emr S.D. ER-to-plasma membrane tethering proteins regulate cell signaling and ER morphology. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ercan E., Momburg F., Engel U., Temmerman K., Nickel W., Seedorf M. A conserved, lipid-mediated sorting mechanism of yeast Ist2 and mammalian STIM proteins to the peripheral ER. Traffic. 2009;10:1802–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maass K., Fischer M.A., Seiler M., Temmerman K., Nickel W., Seedorf M. A signal comprising a basic cluster and an amphipathic alpha-helix interacts with lipids and is required for the transport of Ist2 to the yeast cortical ER. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:625–635. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer M.A., Temmerman K., Ercan E., Nickel W., Seedorf M. Binding of plasma membrane lipids recruits the yeast integral membrane protein Ist2 to the cortical ER. Traffic. 2009;10:1084–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toulmay A., Prinz W.A. A conserved membrane-binding domain targets proteins to organelle contact sites. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:49–58. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omnus D.J., Manford A.G., Bader J.M., Emr S.D., Stefan C.J. Phosphoinositide kinase signaling controls ER-PM cross-talk. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2016;27:1170–1180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min S.W., Chang W.P., Südhof T.C. E-Syts, a family of membranous Ca2+-sensor proteins with multiple C2 domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:3823–3828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611725104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creutz C.E., Snyder S.L., Schulz T.A. Characterization of the yeast tricalbins: Membrane-bound multi-C2-domain proteins that form complexes involved in membrane trafficking. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:1208–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee I., Hong W. Diverse membrane-associated proteins contain a novel SMP domain. FASEB J. 2006;20:202–206. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4581hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alva V., Lupas A.N. The TULIP superfamily of eukaryotic lipid-binding proteins as a mediator of lipid sensing and transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1861:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopec K.O., Alva V., Lupas A.N. Homology of SMP domains to the TULIP superfamily of lipid-binding proteins provides a structural basis for lipid exchange between ER and mitochondria. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1927–1931. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.AhYoung A.P., Jiang J., Zhang J., Khoi Dang X., Loo J.A., Zhou Z.H., Egea P.F. Conserved SMP domains of the ERMES complex bind phospholipids and mediate tether assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E3179–E3188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422363112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawano S., Tamura Y., Kojima R., Bala S., Asai E., Michel A.H., Kornmann B., Riezman I., Riezman H., Sakae Y., Okamoto Y., Endo T. Structure-function insights into direct lipid transfer between membranes by Mmm1-Mdm12 of ERMES. J. Cell Biol. 2018;217:959–974. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201704119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun E.W., Guillén-Samander A., Bian X., Wu Y., Cai Y., Messa M., De Camilli P. Lipid transporter TMEM24/C2CD2L is a Ca2+-regulated component of ER–plasma membrane contacts in mammalian neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:5775–5784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820156116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schauder C.M., Wu X., Saheki Y., Narayanaswamy P., Torta F., Wenk M.R., De Camilli P., Reinisch K.M. Structure of a lipid-bound extended synaptotagmin indicates a role in lipid transfer. Nature. 2014;510:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu H., Liu Y., Gulbranson D.R., Paine A., Rathore S.S., Shen J. Extended synaptotagmins are Ca2+-dependent lipid transfer proteins at membrane contact sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:4362–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517259113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saheki Y., Bian X., Schauder C.M., Sawaki Y., Surma M.A., Klose C., Pincet F., Reinisch K.M., De Camilli P. Control of plasma membrane lipid homeostasis by the extended synaptotagmins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:504–515. doi: 10.1038/ncb3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bian X., Saheki Y., De Camilli P. Ca(2+) releases E-Syt1 autoinhibition to couple ER-plasma membrane tethering with lipid transport. EMBO J. 2018;37:219–234. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giordano F., Saheki Y., Idevall-Hagren O., Colombo S.F., Pirruccello M., Milosevic I., Gracheva E.O., Bagriantsev S.N., Borgese N., De Camilli P. PI(4,5)P(2)-dependent and Ca(2+)-regulated ER-PM interactions mediated by the extended synaptotagmins. Cell. 2013;153:1494–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann P.C., Bharat T.A.M., Wozny M.R., Boulanger J., Miller E.A., Kukulski W. Tricalbins contribute to cellular lipid flux and form curved ER-PM contacts that are bridged by rod-shaped structures. Dev. Cell. 2019;51:488–502.e488. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: Where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haupt A., Minc N. Gradients of phosphatidylserine contribute to plasma membrane charge localization and cell polarity in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:210–220. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-06-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klug L., Daum G. Yeast lipid metabolism at a glance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014;14:369–388. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong L.H., Gatta A.T., Levine T.P. Lipid transfer proteins: The lipid commute via shuttles, bridges and tubes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:85–101. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallo A., Vannier C., Galli T. Endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane associations: Structures and functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;32:279–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda A., Schlarmann P., Kurokawa K., Nakano A., Riezman H., Funato K. Tricalbins are required for non-vesicular ceramide transport at ER-Golgi contacts and modulate lipid droplet biogenesis. iScience. 2020;23:101603. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cunningham K.W. Acidic calcium stores of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu H., Rathore S.S., Shen C., Liu Y., Ouyang Y., Stowell M.H., Shen J. Reconstituting intracellular vesicle fusion reactions: The essential role of macromolecular crowding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12873–12883. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen C., Rathore S.S., Yu H., Gulbranson D.R., Hua R., Zhang C., Schoppa N.E., Shen J. The trans-SNARE-regulating function of Munc18-1 is essential to synaptic exocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8852. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu H., Rathore S.S., Lopez J.A., Davis E.M., James D.E., Martin J.L., Shen J. Comparative studies of Munc18c and Munc18-1 reveal conserved and divergent mechanisms of Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:E3271–E3280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311232110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen J., Tareste D.C., Paumet F., Rothman J.E., Melia T.J. Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell. 2007;128:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y., Wan C., Rathore S.S., Stowell M.H.B., Yu H., Shen J. SNARE zippering is suppressed by a conformational constraint that is removed by v-SNARE splitting. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108611. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rathore S.S., Liu Y., Yu H., Wan C., Lee M., Yin Q., Stowell M.H.B., Shen J. Intracellular vesicle fusion requires a membrane-destabilizing peptide located at the Juxtamembrane region of the v-SNARE. Cell Rep. 2019;29:4583–4592.e4583. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu H., Shen C., Liu Y., Menasche B.L., Ouyang Y., Stowell M.H.B., Shen J. SNARE zippering requires activation by SNARE-like peptides in Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:E8421–e8429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802645115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data presented are contained within the main article and supporting information.