Abstract

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) is the fourth most prevalent neoplasm in men and is associated with high tumour recurrence rates, leading to major treatment challenges. Lysine-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A) is frequently mutated in several cancer types; however, its effects on tumour progression and clinical outcome in BC remain unclear. Here, we explored the potential role of KDM6A in regulating the antitumor immune response.

Methods

We mined The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) databases for somatic mutation and clinical data in patients with BC.

Results

We found frequent mutations in 12 genes in both cohorts, including TP53, KDM6A, CSMD3, MUC16, STAG2, PIK3CA, ARID1A, RB1, EP300, ERBB2, ERBB3, and FGFR3. The frequency o KDM6A mutations in the TCGA and ICGC datasets was 25.97 and 24.27%, respectively. In addition, KDM6A mutation was associated with a lower number of tumour-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) and indicated a state of immune tolerance. KDM6A mutation was associated with lower KDM6A mRNA level compared with that in samples carrying the wild-type gene. Further, survival analysis showed that the prognosis of patients with low KDM6A expression was worse than that with high KDM6A expression. Using the CIBERSORT algorithm, Tumor Immune Estimation Resource site, and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, we found that KDM6A mutation downregulated nine signalling pathways that participate in the immune system and attenuated the tumour immune response.

Conclusion

Overall, we conclude that KDM6A mutation is frequent in BC and promotes tumour immune escape, which may serve as a novel biomarker to predict the immune response.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-08372-9.

Keywords: KDM6A, Bladder cancer, Mutation, Immune

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is considered to be the fourth most prevalent neoplasm in men [1]. BC is associated with high rates of tumour recurrence and progression, which represent major challenges in treatment. Lysine-specific demethylase 6A (KDM6A) is a member of the histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase gene family, which is reported to exert pro-tumorigenic effects in some cancer types [2, 3] but is also considered a tumour suppressor in other contexts [4]. Analyses of tumour-associated genes showed frequent loss of KDM6A expression in several cancers, including BC, B-cell lymphoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and renal papillary cell carcinoma [5–9]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism by which KDM6A might suppress tumour progression in BC remains unclear. To provide insight into this mechanism, we conducted data mining of two separate public cohorts of BC patients to explore the frequency of KDM6A mutations and its potential influence on the immune response. This study can help to elucidate the effect of KDM6A on the tumour microenvironment and develop a potential immunotherapy strategy for BC patients.

Methods

Datasets

The somatic gene mutations and clinical data of 412 samples from BC patients in the United States and 101 samples from BC patients in China were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) online platforms, respectively. Tumor immune estimation resource downloaded from TIMER2.0 (http://timer.cistrome.org/).

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software 14.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (San Diego, CA, USA); P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to generate survival curves, which were evaluated using the log-rank test. Cox regression analyses were performed for assessing the associations of survival with clinical characteristics and KDM6A expression levels. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyse the correlation between KDM6A mutation status and overall mutation counts.

CIBERSORT was conducted to evaluate the proportions of 22 tumor-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) subsets in 412 samples from BC patients in the United States, and estimated the relative abundance of TIICs with different KDM6Astatus.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using GSEA 4.0. Student’s t-test was used to compare the expression level of KDM6A mRNA according to the KDM6A mutation status. The χ2 test was used to evaluate the association between KDM6A mutation status and clinical parameters. In GSEA, P < 0.05 and q < 0.25 were considered statistically significant.

Results

KDM6A mutation is frequent in BC

We downloaded the data, including follow-up profiles and gene expression levels, of 411 and 103 BC tissues from the TCGA and ICGC databases, respectively. Among these samples, 107/411 (25.97%) and 25/103 (24.27%) harboured a KDM6A mutation (Sup. 1A–C).

Missense and truncating mutations were the main mutation types spanning the entire gene (Sup.2A-B), with the former mutation type being most frequent (Sup. 3A); single nucleotide polymorphism was more common than deletion or insertion (Sup. 3B), and C > T was the most common single nucleotide variant in BC (Sup. 3C). The number of variant bases in each sample was counted and the mutation types are shown in a box plot in different colours in Sup. 3D and 3E.

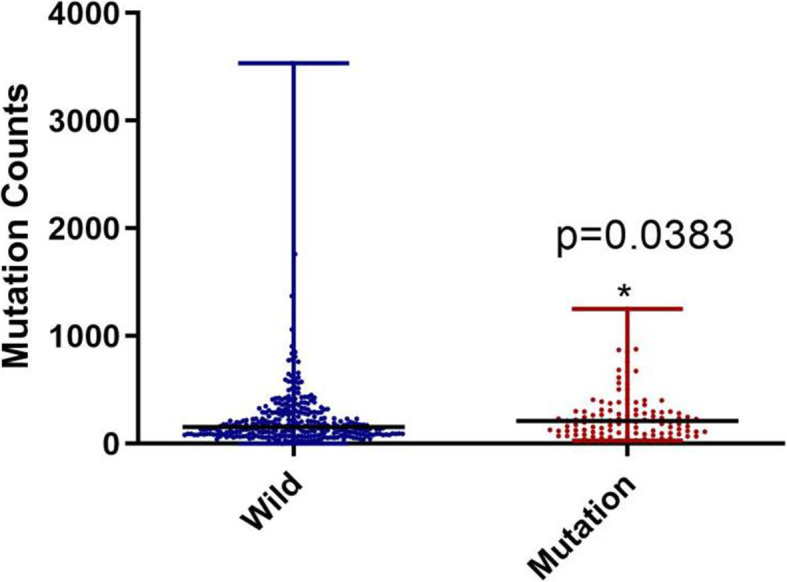

KDM6A mutation is associated with higher mutation counts

BC samples with KDM6A mutations had higher overall mutation counts than wild-type samples in the TCGA cohort (median mutation counts: 210 vs 156.5; p = 0.0383, Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

KDM6A mutation was associated with mutation counts. KDM6A mutation was associated with a higher mutation counts

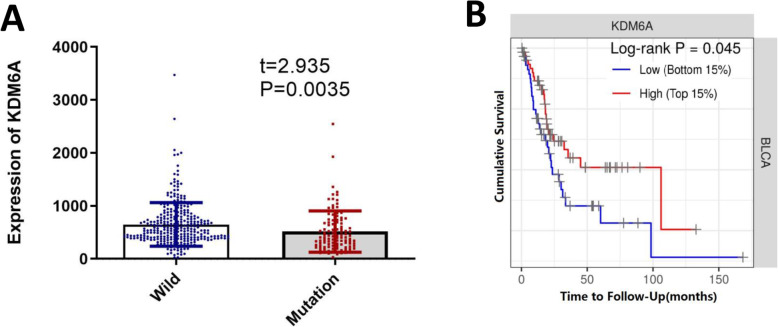

KDM6A mutation is associated with reduced KDM6A mRNA levels and poor prognosis in BC

Patients with KDM6A mutations had lower KDM6A mRNA levels than those with wild-type KDM6A (Fig. 2A). As shown in Sup.4, patients with KDM6A mutations had a higher M stage (TNM staging) than those with wild-type KDM6A. However, no correlation was observed between KDM6A mutation and age, histologic grade, or the tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) stage. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that BC patients with a high KDM6A mRNA (top 15%, n = 61) levels had significantly longer overall survival than those with low KDM6A levels (bottom 15%, n = 61) (Fig. 2B). However, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that a low KDM6A level or presence of KDM6A mutation was not an independent prognostic factor.

Fig. 2.

KDM6A mutation and bladder cancer prognosis. AThe difference of mRNA expression between KDM6A mutation and wild. B Kaplan–Meier survival curves for bladder cancer patients stratified by KDM6A mRNA levels (Low n = 61, High n = 61)

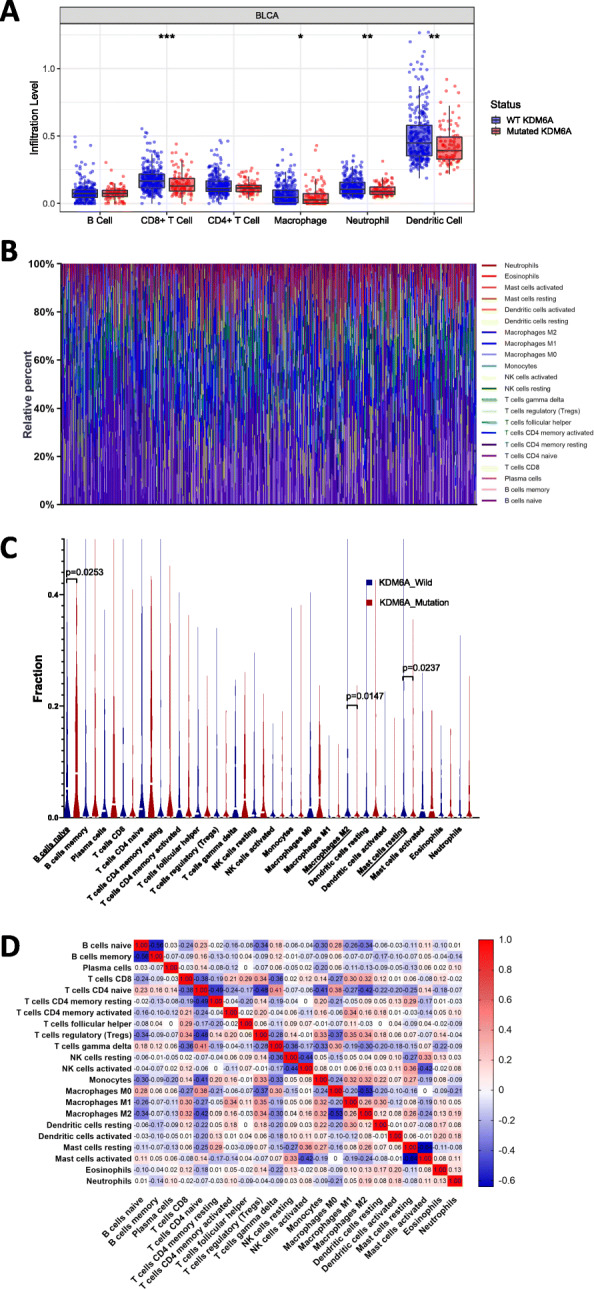

KDM6A mutation is significantly correlated with tumour-infiltrating immune cells (TIICs) in the tumour microenvironment

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) analysis showed that KDM6A mutation was associated with a lower number of TIICs. The infiltration levels of macrophages (p = 1.44e-2), CD8+ T cells (p = 5.79e-4), neutrophils (p = 4.40e-3), and resting dendritic cells (p = 3.70e-3) in the KDM6A mutation group were lower than those in the KDM6A wild-type group (Fig. 3A). The association between KDM6A mutation and different types of immune cells was significant, including dendritic cells (p = 9.70e-3, cor = − 0.1272), CD8 T cells (p = 6.0e-4, cor = − 0.1689), macrophages (p = 1.03e-2, cor = − 0.1262), and neutrophils (p = 5.1e-3, cor = − 0.1375).

Fig. 3.

KDM6A mutation was correlated with tumor-infiltrating immune cells. A The diffrence of 8 immune cells between KDM6A mutation group and KDM6A wild-type group. Blue color represented KDM6A wild-type group, and red color represents KDM6A mutation group. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 B Stacked bar chart showed distribution of 22 immune cells in each sample. C Violin plot displayed the differentially infiltrated immune cells between KDM6A mutation group and KDM6A wild-type group. Blue color represented KDM6A wild-type group, and red color represented KDM6A mutation group. D Correlation matrix of immune cell proportions. The red color represented positive correlation and the blue color represented negative correlation

To further assess the correlation of KDM6A mutation with TIICs in the BC microenvironment, the CIBERSORT algorithm was used. The composition of 22 TIICs in each sample varied significantly (Fig. 3B). Moreover, naive B cells were more enriched in the KDM6A mutation group, whereas M2 macrophages and resting mast cells were more enriched in the KDM6A wild-type group (Fig. 3C). Correlation analysis showed that memory-activated CD4+ T cells were positively correlated with CD8+ T cells, and also had a positive association with the number of M1 macrophages. In turn, resting macrophages were positively correlated with levels of activated natural killer (NK) cells. However, activated NK cells were negatively correlated with activated mast cells (Fig. 3D).

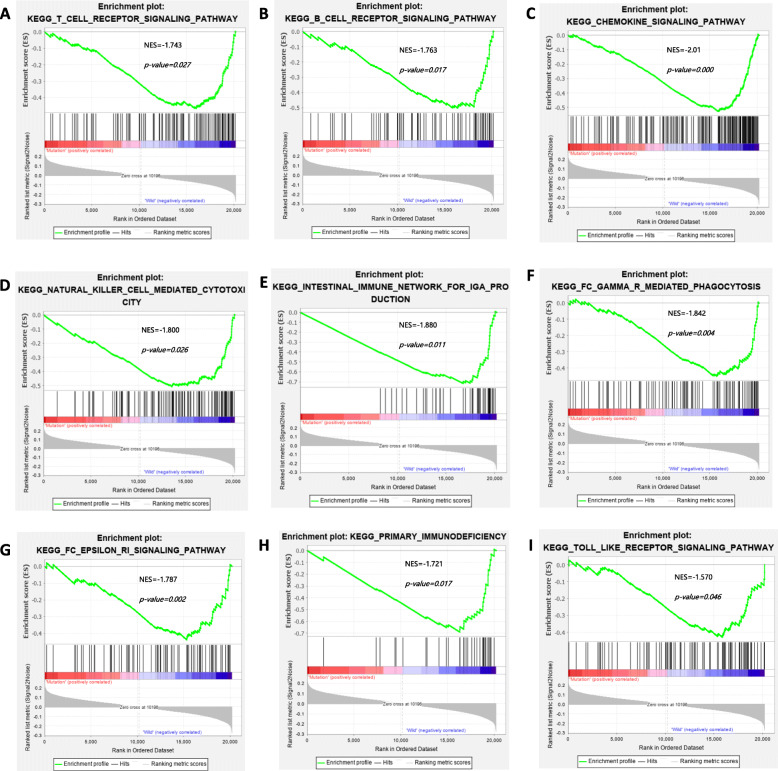

Enrichment pathway analysis of KDM6A mutation

We further explored the relationship between KDM6A mutation and the immune response. GSEA revealed that the intestinal immune network for IgA production, the chemokine signalling pathway, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, the B cell receptor signalling pathway, the T cell receptor signalling pathway, the Fc epsilon Ri signalling pathway, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, primary immunodeficiency, and the Toll-like receptor signal pathway was significantly downregulated in the KDM6A mutation group (Fig. 4A–I). These results implied that KDM6A mutation downregulates signalling pathways involved in the immune system in BC.

Fig. 4.

Significantly enriched pathways associated with KDM6A mutation. Gene set enrichment analysis has been performed with TCGA. Gene enrichment plots showed that a series of gene sets including A T Cell Receptor Signaling Pathway, B B Cell Receptor Signaling Pathway, C Chemokine Signaling Pathway, D Natural Killer Cell Mediated Cytotoxicity, E Intestinal Immune Network for Ig A production, F Fc Gamma R Mediated Phagocytosis, G Fc Epsilon Ri Signaling Pathway, H Primary Immunodeficiency and I Toll Like Receptor Signaling Pathway were enriched in KDM6A mutation group. NES, normalized enrichment score. The p-value is marked in each plot

Discussion

Dysfunction in demethylation occurs frequently in cancer cells, which can destroy the chromatin configuration and disrupt normal transcriptional processes. KDM6A is a specific H3K27me3 demethylase, and inactivating mutations in KDM6A have been frequently detected in BC [1]. KDM6A was suggested to act as a tumour suppressor in several cancers [10]. Other studies reported abnormal levels of trimethylated H3K27 (H3K27me3) in some cancers, which correlated with a poor prognosis [11–13], suggesting that demethylases are involved in both oncogenesis and tumour progression. Several recent studies identified inactivating mutations of KDM6A in different cancer tissues, along with decreased expression levels of KDM6A in cancer compared with those in normal tissues, further supporting that KDM6A is a tumour suppressor [14–17]. KDM6A mutation is common especially in women with BC [18, 19]. Mutations in or a decreased expression level of KDM6A was also associated with a poor prognosis of female BC patients [20].

Our present analysis of the somatic mutation landscape data of BC samples from the TCGA dataset (412 cases) and ICGC dataset (101 cases) confirmed that KDM6A was frequently mutated in both cohorts, in line with previous studies [6, 19]. Moreover, KDM6A mutation was correlated with higher overall gene mutation counts, but was not associated with clinical prognosis.

Importantly, we identified that KDM6A mutation in BC was negatively associated with signalling pathways involved in the immune response. We observed reduced infiltration of immune cells in KDM6A-mutated tissues, including neutrophils, macrophages, and CD8+ T cells, which is consistent with previous reports showing that these immune cells play key roles in the tumour microenvironment and suppress the immune response. A reduced number of CD8+ T cells in the tumour indicated a worse prognosis for patients in a previous study [21]. GSEA of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways between gene sets of BC samples with mutated and wild-type KDM6A demonstrated that the signalling pathways of cell-adhesion molecules, ECM receptor interaction, and focal adhesion were also suppressed by KDM6A mutation. These findings support the need for further in-depth study of the possible role of KDM6A in regulation of cell adhesion and morphology in BC [22]. KDM6A deficiency has been suggested to activate pathways of chemokines and cytokines, increase M2 macrophage polarization, increase cancer stem cell abundance, and act synergistically with p53 haploinsufficiency [23]. Given the key function of KDM6A in regulating CD4+ T cells [24], concluded that KDM6A likely regulates multiple immune response genes in autoimmune disease susceptibility.

There are several limitations in this study. Fist, specimens of superficial bladder cancer are a few. Therefore, more studies could conduct on invasive bladder cancer and superficial bladder cancer, separately. Second, the molecular mechanism by which KDM6A might suppress tumour progression need further research. Third, although our results suggested that BC patients with a high KDM6A mRNA (top 15%, n= 61) levels had significantly longer overall survival than those with low KDM6A levels (bottom 15%, n = 61), but there is insufficient high-quality data and more studies are needed. Finally, although our results showed naive B cells were more enriched in the KDM6A mutation group, it is still unclear whether naive B cells are involved in immune escape and the mechanism, further study is needed.

Conclusions

This study identified that KDM6A was frequently mutated in BC, and KDM6A mutation was correlated with a higher overall gene mutation status. Furthermore, KDM6A mutation was shown to negatively regulate the signalling pathways of the immune system and to suppress antitumor immunity. These findings suggest KDM6A as a latent gene whose mutation could be considered as a predictive biomarker for the immune response, thereby facilitating the development of new strategies for immunotherapy and treatment monitoring in BC patients.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- KDM6A

Lysine-specific demethylase 6A

- BC

Bladder cancer

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- ICGC

International Cancer Genome Consortium

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- TNM

Tumour-node-metastasis

- TIICs

Tumour-infiltrating immune cells

- TIMER

Tumor immune estimation resource.

- TP53

Tumor protein p53

- CSMD3

CUB And Sushi Multiple Domains 3

- MUC16

Mucin 16

- STAG2

Stromal antigen2

- PIK3CA

Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha

- ARID1A

AT-rich interactive domain containing protein 1A

- RB1

Retinoblastoma1

- EP300

E1A binding protein p300

- ERBB2

Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- ERBB3

Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- FGFR3

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

Authors’ contributions

Chen X., Lin X. and Zhang Z. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordinated and drafted the manuscript. Chen X. and Lin X. performed the statistical analyses. Pang G., Deng J., Xie Q. and Zhang Z. gave critical advice and participated in manuscript revising. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the Corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC; https://dcc.icgc.org/) and TIMER (http://timer.cistrome.org/).

Declarations

Competing of interests

None declared.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data is publicly available therefore no Ethics approval is required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Qiu JG, Shi DY, Liu X, Zheng XX, Wang L, Li Q. Chromatin-regulatory genes served as potential therapeutic targets for patients with urothelial bladder carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):6976–6982. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz WA, Lang A, Koch J, Greife A. The histone demethylase UTX/KDM6A in cancer: Progress and puzzles. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(3):614–620. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Shilatifard A. UTX mutations in human Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Meulen J, Speleman F, Van Vlierberghe P. The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX in normal development and disease. Epigenetics. 2014;9(5):658–668. doi: 10.4161/epi.28298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502(7471):333–339. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S, Yim S, Park H. The cancer driver genes IDH1/2, JARID1C/ KDM5C, and UTX/ KDM6A: crosstalk between histone demethylation and hypoxic reprogramming in cancer metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51(6):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Liu M, Chen CD, Jiang H. UTX is an escape from X-inactivation tumor-suppressor in B cell lymphoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2720. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05084-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linehan WM, Spellman PT, Ricketts CJ, Creighton CJ, Fei SS, Davis C, Wheeler DA, Murray BA, Schmidt L, Vocke CD, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of papillary renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):135–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Lee W, Jiang Z, Chen Z, Jhunjhunwala S, Haverty PM, Gnad F, Guan Y, Gilbert HN, Stinson J, Klijn C, Guillory J, Bhatt D, Vartanian S, Walter K, Chan J, Holcomb T, Dijkgraaf P, Johnson S, Koeman J, Minna JD, Gazdar AF, Stern HM, Hoeflich KP, Wu TD, Settleman J, de Sauvage FJ, Gentleman RC, Neve RM, Stokoe D, Modrusan Z, Seshagiri S, Shames DS, Zhang Z. Genome and transcriptome sequencing of lung cancers reveal diverse mutational and splicing events. Genome Res. 2012;22(12):2315–2327. doi: 10.1101/gr.140988.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Sharma A, Dhar SS, Lee SH, Gu B, Chan CH, Lin HK, Lee MG. UTX and MLL4 coordinately regulate transcriptional programs for cell proliferation and invasiveness in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74(6):1705–1717. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y, Xia W, Zhang Z, Liu J, Wang H, Adsay NV, Albarracin C, Yu D, Abbruzzese JL, Mills GB, Bast RC, Jr, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC. Loss of trimethylation at lysine 27 of histone H3 is a predictor of poor outcome in breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47(9):701–706. doi: 10.1002/mc.20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellakuru LG, Iwata T, Gurel B, Schultz D, Hicks J, Bethel C, Yegnasubramanian S, De Marzo AM. Global levels of H3K27me3 track with differentiation in vivo and are deregulated by MYC in prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(2):560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun S, Yang Q, Cai E, Huang B, Ying F, Wen Y, Cai J, Yang P. EZH2/H3K27Me3 and phosphorylated EZH2 predict chemotherapy response and prognosis in ovarian cancer. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9052. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy DM, Walsh LA, Chan TA. Driver mutations of cancer epigenomes. Protein Cell. 2014;5(4):265–296. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, Chen L, Bignell G, Butler A, Davies H, Edkins S, Hardy C, Latimer C, Teague J, Andrews J, Barthorpe S, Beare D, Buck G, Campbell PJ, Forbes S, Jia M, Jones D, Knott H, Kok CY, Lau KW, Leroy C, Lin ML, McBride DJ, Maddison M, Maguire S, McLay K, Menzies A, Mironenko T, Mulderrig L, Mudie L, O’Meara S, Pleasance E, Rajasingham A, Shepherd R, Smith R, Stebbings L, Stephens P, Tang G, Tarpey PS, Turrell K, Dykema KJ, Khoo SK, Petillo D, Wondergem B, Anema J, Kahnoski RJ, Teh BT, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463(7279):360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gui Y, Guo G, Huang Y, Hu X, Tang A, Gao S, Wu R, Chen C, Li X, Zhou L, He M, Li Z, Sun X, Jia W, Chen J, Yang S, Zhou F, Zhao X, Wan S, Ye R, Liang C, Liu Z, Huang P, Liu C, Jiang H, Wang Y, Zheng H, Sun L, Liu X, Jiang Z, Feng D, Chen J, Wu S, Zou J, Zhang Z, Yang R, Zhao J, Xu C, Yin W, Guan Z, Ye J, Zhang H, Li J, Kristiansen K, Nickerson ML, Theodorescu D, Li Y, Zhang X, Li S, Wang J, Yang H, Wang J, Cai Z. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):875–878. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira F, Barbáchano A, Silva J, Bonilla F, Campbell MJ, Muñoz A, Larriba MJ. KDM6B/JMJD3 histone demethylase is induced by vitamin D and modulates its effects in colon cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(23):4655–4665. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassar AH, Umeton R, Kim J, Lundgren K, Harshman L, Van Allen EM, Preston M, Dong F, Bellmunt J, Mouw KW, et al. Mutational analysis of 472 Urothelial carcinoma across grades and anatomic sites. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(8):2458–2470. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurst CD, Alder O, Platt FM, Droop A, Stead LF, Burns JE, Burghel GJ, Jain S, Klimczak LJ, Lindsay H, et al. Genomic Subtypes of Non-invasive Bladder Cancer with Distinct Metabolic Profile and Female Gender Bias in KDM6A Mutation Frequency. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(5):701–715.e707. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaneko S, Li X. X chromosome protects against bladder cancer in females via a KDM6A-dependent epigenetic mechanism. Sci Adv. 2018;4(6):eaar5598. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen CS, Prokhnevska N, Master VA, Sanda MG, Carlisle JW, Bilen MA, Cardenas M, Wilkinson S, Lake R, Sowalsky AG, Valanparambil RM, Hudson WH, McGuire D, Melnick K, Khan AI, Kim K, Chang YM, Kim A, Filson CP, Alemozaffar M, Osunkoya AO, Mullane P, Ellis C, Akondy R, Im SJ, Kamphorst AO, Reyes A, Liu Y, Kissick H. An intra-tumoral niche maintains and differentiates stem-like CD8 T cells. Nature. 2019;576(7787):465–470. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1836-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang A, Yilmaz M, Hader C, Murday S, Kunz X, Wagner N, et al. Contingencies of UTX/KDM6A Action in Urothelial Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4):481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kobatake K, Ikeda KI, Nakata Y, Yamasaki N, Ueda T, Kanai A, Sentani K, Sera Y, Hayashi T, Koizumi M, Miyakawa Y, Inaba T, Sotomaru Y, Kaminuma O, Ichinohe T, Honda ZI, Yasui W, Horie S, Black PC, Matsubara A, Honda H. Kdm6a deficiency activates inflammatory pathways, promotes M2 macrophage polarization, and causes bladder Cancer in cooperation with p53 dysfunction. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(8):2065–2079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itoh Y, Golden LC, Itoh N, Matsukawa MA, Ren E, Tse V, Arnold AP, Voskuhl RR. The X-linked histone demethylase Kdm6a in CD4+ T lymphocytes modulates autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(9):3852–3863. doi: 10.1172/JCI126250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the Corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov), International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC; https://dcc.icgc.org/) and TIMER (http://timer.cistrome.org/).